Access and Benefit Sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity and Its Protocol: What Can Some Numbers Tell Us about the Effectiveness of the Regulatory Regime?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Context

1.2. The Genetic Resource and Its Utilization

- Selective breeding and artificial selection, which is the selection of organisms with useful properties by producing targeted mutations on their genomes or by crossing directly their genomes (cell fusion, molecular markers, etc.).

- Genetic engineering, which is the modification of genomes by removing genetic material or by adding sequences from other organisms, which belong or not to the same species.

- Synthetic biology, which is the artificial creation of biological systems (naturally occurring or not) by adding artificial DNA sequences to a minimal natural genetic ‘frame’ or by assembling segments of artificial DNA to build a functional system.

1.3. Material and Intellectual Property Rights over Genetic Resources

1.4. Global Regulation of Genetic Resources Utilization

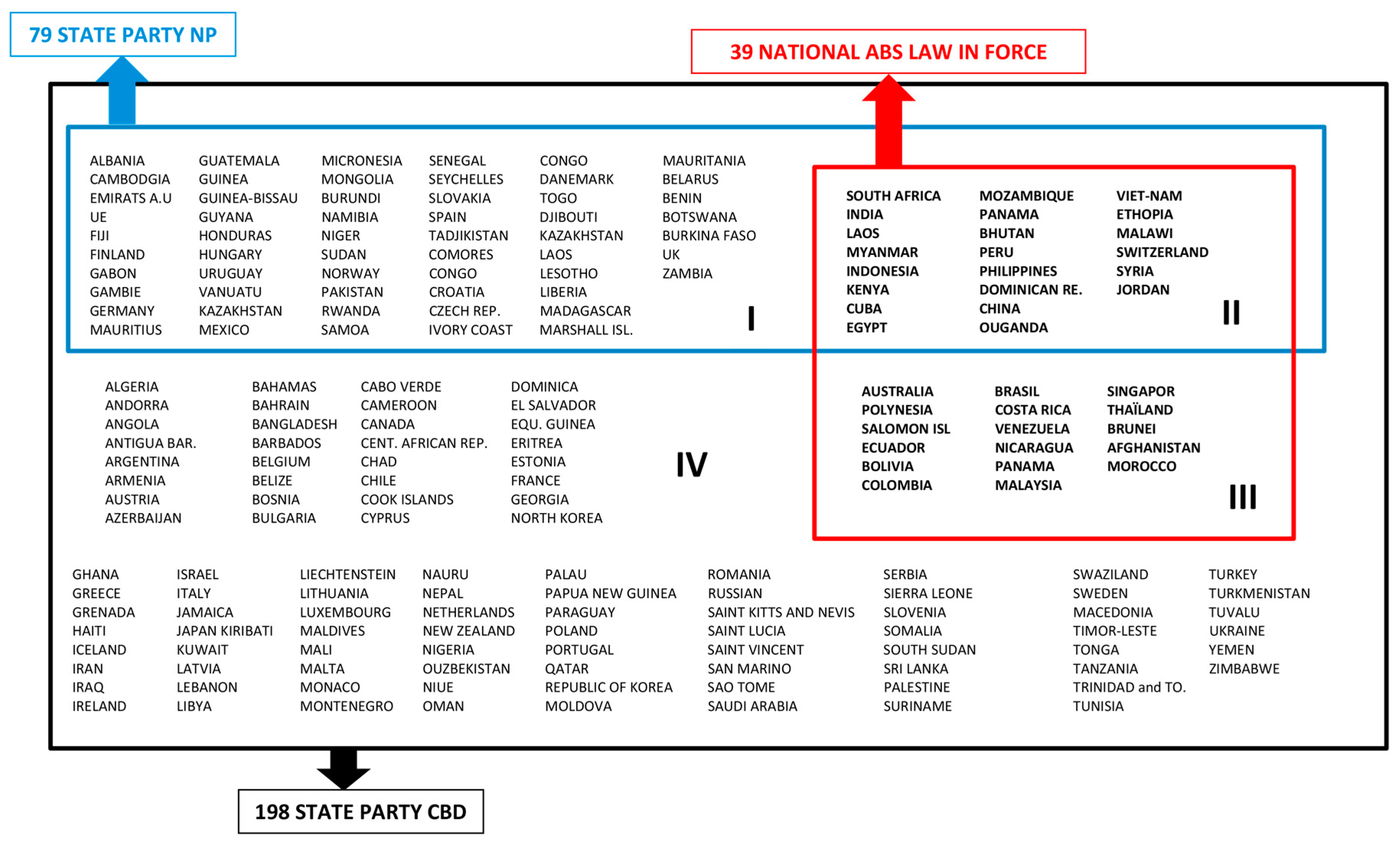

- (I)

- States Parties to the NP: 79 countries

- (II)

- States Parties to the NP with a ABS legislation in force: 22 countries

- (III)

- States Parties to the CBD: 119 countries

- (IV)

- States Parties to the CBD with a ABS legislation in force: 17 countries

2. Purposes of the Study

2.1. Estimation of the Number of Permits Issued and ABS Agreements Concluded

2.1.1. Data Collected from an Online Survey

- How many ABS agreements have been concluded in your country?

- How many access permits to GR have been issued in your country?

- If possible, could you indicate the proportion of agreements/permits that have been concluded/issued before and after your country became a State Party to the NP?

2.1.2. Data Collected from Secondary Sources

2.1.3 The Access and Benefits Sharing Clearing-House as Source of Data

2.2. Critical Review of the Current Existing Explanations of the Numbers of Permits and Agreements

- (1)

- Very few contracts have been concluded because the implementation of national ABS laws by States Parties is incomplete or dissuading potential users to request access to GR:

- ○

- Only a small minority of States Parties to the Convention or Protocol have been able to put in place the corresponding national legislations. This is notably due to a lack of technical expertise, lack of sufficient budget, lacking strong enough government structures and political support, local social conflict, and conflict over ownership of GR [35].

- ○

- Among the few states that have succeeded in adopting ABS legislation, several have developed fragmented and ambiguous legal frameworks with poorly defining competencies, multiplying PIC to be obtained from different stakeholders and on the basis of different laws. Some existing legislations require long, cumbersome, and complicated procedures to establish MATs or obtain access [6,12]. They also do not offer sufficiently distinct procedures between access requests for basic and commercial researches [4,12]. The adoption of such restrictive legislations is explained by the expectations among provider countries that they will get money from the ABS mechanism and their will to put an end to the free and abusive utilization of “their” GR [4]. The lack of willingness by user countries to put measures into place to monitor compliance with the provisions of supplier countries is also mentioned as one of the factors that have made provider countries particularly cautious and pushed them to adopt restrictive access conditions to their GR [11,12]. Indeed, once the GR has left the provider’s territory, the latter has no way to monitor that the downstream process of R&D complies with the provisions of the corresponding ABS agreement. The insurance that user countries would monitor downstream process in that regard was therefore crucial for provider States. That was, and still is, a source of major disappointment for them and they responded to it by adopting restrictive ABS provisions [4,11].

- (2)

- Very few contracts have been concluded because of a lack of demand for GR by potential users

- ○

- The high demand for GR that was anticipated during the 1990s has not been confirmed. The entry into force of the CBD is already 22 years old and progress in the field of biotechnology has profoundly modified the research processes as well as the research strategies of the pharmaceutical, agrochemical, food, and cosmetic firms. On one hand, it became possible to probe more deeply the GR research teams already have in their immediate environment or in the numerous ex situ collections they can freely access [8]. For example, in the agrochemical and seed sectors, the major actors of the industry use mergers and acquisitions to extend their collections of GR. The seed industry has been consolidating strongly over the last 30 years. The numerous small actors of the market (and most importantly the varieties, genes or technologies they possess through IPRs) are bought by a few multinationals through mergers and acquisitions [10,36,37,38]. As a result, in the early 2000s, emerged the so-called ”Big Six” group composed of Syngenta, Bayer, Monsanto, DuPont, Dow, and BASF. These consolidated groups are active in both the agrochemical, seed, and pharmaceutical sectors. For the seed market in particular, the five largest groups hold more than 45% of the market share in terms of sales volumes [36]. Consolidation has a direct effect on plant GR exchanges as well as, although to a lesser extent, on bioprospection for wild GR. Indeed, this industrial strategy of both vertical and horizontal integration aims among other things to obtain IPRs (mostly patent) via the purchase of the small companies that have those IPRs over biotechnology technics, traits (genes), organisms, etc. [9,10]. Consolidation thus proportionally increases the catalog of GR at the disposal of the “Big Six”, whether these GR are protected by a plant breeders right or a patent. Consequently, these ‘giant’ actors escape the ABS regime, as they are not (or to a minimal extend) requesting access to foreign GR.

- ○

- On the other hand, high throughput screening and combinatorial chemistry make it possible to generate whole libraries of molecules to be tested on various biological targets without having to rely on the diversity of natural compounds and in a faster and cheaper way than the latter [9]. As a result, there is a decline of interest for the search for exotic GR—the so called “green gold”—since the 1990s [3,29].

- ○

- Moreover, if GR are used through biotechnology technics, only a minute amount of the resource is needed to conduct R&D program (sequencing, amplification, eventually artificial reproduction, etc.), which makes the monitoring of access difficult and the resupply unnecessary. Metagenomics represent an “extreme” aspect of this evolution as it makes it possible to extract genetic material from complex environmental samples, without having to deal with the organisms carrying it [9]. Finally, because of scientific advances, the interest for GRs has shifted to micro-organisms. This evolution has several decreasing effects on demand for access to GR: the origin of micro-organisms is far more difficult to identify, one can easily access microbes through vast and freely accessible collections or by collecting samples in his own backyard [9].

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Results

3.1.1. Accuracy of the Estimation

3.1.2. General Comments

3.1.3. Analysis of the First Explanatory Causal Mechanism in the Light of the Results

3.1.4. Analysis of the Second Explanatory Causal Mechanism in the Light of the Results

3.2. Research Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oberthür, S.; Rosendal, G.K. Global governance of genetic resources: Background and analytical framework. In Global Governance of Genetic Resources: Access and Benefit Sharing after the Nagoya Protocol; Oberthür, S., Rosendal, G.K., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mahrane, Y.; Fenzi, M.; Pessis, C.; Blanchard, E.; Korczak, A.; Bonneuil, C. De la nature à la biosphère: La construction de l’environnement comme problème politique mondial 1945–1972. Vingtième Siècle Revue D’histoire 2012, 113, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvert, V.; Tordjman, H. Vingt ans de politiques de conservation de la biodiversité: De la marchandisation des ressources génétiques à la finance “verte”. Econ. Appl. 2012, 65, 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kamau, E.C. Valorisation of genetic resources, benefit sharing and conservation of biological diversity: What role for the ABS regime? In Ex Rerum Natura Ius?—Sachzwang und Problemwahrnehmung im Umweltrecht; Dilling, O., Till, M., Eds.; Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co.: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2014; pp. 143–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kamau, E.C. Research and Development under the convention on biological diversity and the Nagoya protocol. In Research and Development on Genetic Resources: Public Domain Approaches in Implementing the Nagoya Protocol; Kamau, E.C., Winters, G., Stoll, P.T., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morgera, E.; Tsioumani, E.; Buck, M. Unraveling the Nagoya Protocol: A Commentary on the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online: http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/books/9789004217188 (accessed on 19 September 2016).

- Richerzhagen, C. Effective governance of access and benefit-sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 2243–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, S.; Wynberg, R. Bioscience at a Crossroads: Implementing the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing in a Time of Scientific, Technological and Industry Change; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, S. Bioscience at a Crossroads: Access and Benefit Sharing in a Time of Scientific, Technological and Industry Change. The Pharmaceutical Industry; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wynberg, R. Bioscience at a Crossroads: Implementing the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing in a Time of Scientific, Technological and Industry Change. The Agricultural Sector; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kamau, E.C.; Fedder, B.; Winter, G. The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit Sharing: What is New and what are the Implications for Provider and User Countries and the Scientific Community? Law Environ. Dev. J. 2010, 6, 248–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kamau, E.C.; Winter, G. Unbound R&D and bound benefit sharing. In Research and Development on Genetic Resources: Public Domain Approaches in Implementing the Nagoya Protocol; Kamau, E.C., Winters, G., Stoll, P.T., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, F. Biodiversité, biotechnologies et savoirs traditionnels. Du patrimoine commun de l’humanité aux ABS (Access to genetic resources and benefit-sharing). Revue Tiers Monde 2006, 4, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, G.; Knoepfel, P.; Fricker, H.-P. L’utilisation des ressources génétiques en biotechnologie et son cadre réglementaire. Pour une approche intégrative. In Durabilitas; Sanu Durabilitas: Bienne, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasulu, N.S.; Raju, C.B. Biotechnology and patent law. In Patenting Living Beings, 1st ed.; Manupatra Information Solutions Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeney, M. Trends in Intellectual Property Rights Relating to Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; Background Study Paper No. 58; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, J.M. Gene Patents and the Product of Nature Doctrine. Available online: http://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3638&context=cklawreview (accessed on 27 August 2016).

- Kamau, E.C. The Multilateral of the international treaty on plant genetic resources for food and agriculture: Lessons and room for further development. In Common Pools of Genetic Resources. Equity and Innovation in International Biodiversity Law; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Noiville, C. Aspect juridique: Droits d’accès aux ressources biologiques et partage des avantages. In Substances Naturelles en Polynésie Française: Stratégies de Valorisation; Guezennec, J., Moretti, C., Simon, J.-C., Eds.; Institut de Recherche Pour le Développement (IRD): Paris, France, 2006; pp. 178–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneuil, C.; Fenzi, M. Des ressources génétiques à la biodiversité cultivée: La carrière d'un problème public mondial. Revue D’Anthropologie des Connaissances 2011, 5, 206–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C. Governance of Genetic Resources: A Guide to Navigating the Complex Global Landscape; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- CBD. Article 2. Use of Terms. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/convention/articles/default.shtml?a=cbd-02 (accessed on 19 February 2017).

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Global Biodiversity Outlook. 2001. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/gbo/ (accessed on 18 July 2016).

- Hendricks, B. Transformative possibilities: Reinventing the convention on biological diversity. In Protection of Global Biodiversity: Converging Strategies; Guruswamy, L., McNeely, J., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, A.-C. Les traités-cadre: Une technique juridique caractéristique du droit international de l’environnement. Annuaire Français de Droit International 1993, 39, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NP. Article 2 (c). Use of Terms. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/ (accessed on 19 February 2017).

- Access and Benefit-Sharing in Latin America and the Caribbean—A Science-Policy Dialogue for Academic Research. 2014. Available online: http://www.naturwissenschaften.ch/uuid/c22d3dc3-8390-5a83-9eae-1fbbecfd35c0?r=20161005181841_1475029064_a141fec8-b94a-577e-a47e-ac365d799eee (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- Barett, C.B.; Lybbert, T.J. Is bioprospecting a viable strategy for conserving tropical ecosystems? Ecol. Econ. 2000, 34, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firn, R.D. Bioprospecting: Why is it so unrewarding? Biodivers. Conserv. 2003, 12, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, C.; Aubertin, C. Stratégies des firmes pharmaceutiques: La bioprospection en question. In Les Marchés de la Biodiversité; Aubertin, C., Pinton, F., Boisvert, V., Eds.; Institut de Recherche Pour le Développement (IRD): Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- NP. Article 6.3 (c) Access to Genetic Resources. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/ (accessed on 19 February 2017).

- NP. Article 13.4 National Focal Points and Competent National Authorities. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/ (accessed on 19 February 2017).

- NP. Article 13.5 National Focal Points and Competent National Authorities. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/ (accessed on 19 February 2017).

- NP. Article 14.2 The Access and Benefit-Sharing Clearing-House and Information-Sharing. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/ (accessed on 19 February 2017).

- Cabrera Medaglia, J.; Perron-Welch, F.; Phillips, F.-K. Overview of National and Regional Measures on Access and Benefit Sharing Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing the Nagoya Protocol, 3rd ed.; CISDL Biodiversity & Biosafety Law Research Programme; Centre for International Sustainable Development Law (CISDL): Montreal, QC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bonny, S. Taking stock of the genetically modified seed sector worldwide: Market, stakeholders, and prices. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglie, K.O.; Heisey, P.; King, J.L.; Pray, C.E.; Day-Rubenstein, K.; Schimmelpfennig, D.; Wang, S.L.; Karmarkar-Deshmukh, R. Research Investments and Market Structure in the Food Processing, Agriculture Input and Biofuel Industries Worldwide; Economic Research Report 130; Economic Research Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Mammana, I. Concentration of Market Power in the EU Seed Market. Available online: http://www.agricolturabiodinamica.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Rapporto-Green-EU-sul-monopolio-delle-sementi-n-Europa.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2016).

- ABS Initiative. National Study on ABS Implementation in South Africa, Workshop January 2014. Available online: http://www.abs-initiative.info/fileadmin/media/Knowledge_Center/Pulications/ABS_Dialogue_042014/National_study_on_ABS_implementation_in_South_Africa_20140716.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2016).

- ABS Initiative. National Study on ABS Implementation in Brazil, Workshop January 2014. Available online: http://www.abs-initiative.info/fileadmin/media/Knowledge_Center/Pulications/ABS_Dialogue_042014/National_study_on_ABS_implementation_in_Brazil_20140716.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2016).

| Access Permits Granted | ABS Agreements Concluded | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | Non-Commercial | Commercial | Non-Commercial | Commercial ABS Agreements/Year | |

| States Parties to the Nagoya Protocol with ABS Legislation in Force | |||||

| India (2006–2016) | 91 (53 since Party to the NP) | 14 (2 under NP) | 0 | 1.4 | |

| Guyana (2000–2014) | 344 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cuba (2008–2016) | 200 | 5 | 0 | 0.6 | |

| Peru (2009–2013) | 180 | 0 | 10 | 2.5 | |

| South Africa (2008–2015) | 17 | 33 | n.i | 4.7 | |

| Indonesia (2000–2015) | 5286 | n.i | n.i | n.i | |

| States Parties to the Nagoya Protocol | |||||

| 18 other state parties 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| States Parties to the CBD with ABS Legislation in Force | |||||

| Costa Rica (2004–2015) | 50 | 333 | 3 | 45 | 0.2 |

| Ecuador (2011–2016) | n.i | 1 | 39 | 0.2 | |

| Venezuela (1996–2016) | 39 | 22 (13 since the current ABS law entered into force in 2009) | 57 (27 since the current ABS law entered into force in 2009) | 1.1 | |

| Brazil (2004–2013) | n.i | 1057 (2010–2012) | 103 | n.i | 11.4 |

| Bolivia (2000–2005) | n.i | 2 (50–60 requests) | 8 | 0.4 | |

| Colombia (2003–2013) | n.i | 1 | 89 (199 requests) | 0.1 | |

| Mexico (1996–2011) | 4283 | n.i | n.i | n.i | |

| Australia (2006–2015) | 3 | 276 | 3 | n.i | |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pauchard, N. Access and Benefit Sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity and Its Protocol: What Can Some Numbers Tell Us about the Effectiveness of the Regulatory Regime? Resources 2017, 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources6010011

Pauchard N. Access and Benefit Sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity and Its Protocol: What Can Some Numbers Tell Us about the Effectiveness of the Regulatory Regime? Resources. 2017; 6(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources6010011

Chicago/Turabian StylePauchard, Nicolas. 2017. "Access and Benefit Sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity and Its Protocol: What Can Some Numbers Tell Us about the Effectiveness of the Regulatory Regime?" Resources 6, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources6010011

APA StylePauchard, N. (2017). Access and Benefit Sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity and Its Protocol: What Can Some Numbers Tell Us about the Effectiveness of the Regulatory Regime? Resources, 6(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources6010011