Abstract

This paper demonstrates the potential of the mining industry to contribute to social development (community building, resilience and wellbeing) and to economic transitioning post-mining. A number of factors may facilitate the realisation of this potential, in particular community engagement activities that build community resilience and capacity to adapt to changing environments. This paper reviews a community foresight initiative, named Clermont Preferred Future (CPF), which is associated with a coal mine development in the town of Clermont in Queensland, Australia. The purpose of CPF, which was adopted in 2008 and is intended to continue to 2020, is to facilitate a transition to a prosperous and sustainable future by leveraging opportunities from coal mining while reducing dependence on the industry. CPF has been cited as a successful model of engagement and community development, and was highly commended in the Community Economic Development category at the 2011 Australian National Awards for Economic Development Excellence. This review draws on the experiences of stakeholders involved in CPF, and on foresight, community engagement, and community development literature. It identifies what has worked well, what has fallen short of the project’s rhetorical aspirations, and how processes and outcomes might be improved. It also trials artwork as an engagement tool. The findings are valuable for Clermont specifically, but also for the mining industry and mining communities more broadly, as well as for other industries in the context of community engagement and strategic planning.

1. Introduction

The relationship between mining operations and local communities is a complex and challenging one, replete with legacies of destruction, dislocation and dispossession as well as development. The town of Clermont in Queensland, Australia, has a long history with coal mining, and like many regional communities, has a strong interest in maximising the benefits of mining. Clermont Preferred Future (CPF) is a community foresight and planning initiative adopted in 2008. It was led by Belyando Shire Council (now Isaac Regional Council), and supported by Rio Tinto Coal Australia (RTCA) and the local community [1]. The initiative aimed to involve stakeholders in an effort to develop a prosperous future that leverages opportunities from mining while seeking to reduce dependence on the industry. The timing of the initiative was critical, since RTCA’s nearby Blair Athol mine was approaching closure and its new Clermont Mine was expecting to commence operations; this shift would significantly influence both the impact of mining locally and perceptions of those impacts.

The initial development of CPF culminated in a vision for 2020 and a Preferred Future Strategy. The vision describes Clermont as “a dynamic, vibrant and well-connected community of high liveability, demonstrated by a strong sense of self-determination and self-reliance, and which is underpinned by a diverse and robust economy” [2]. The accompanying strategy comprises six themes that encapsulate this shared vision, or ‘Preferred Future’:

- Business entrepreneurship, and economic development;

- Infrastructure investment, and transport;

- Leadership and governance;

- Liveability and lifestyle;

- Natural capital and cultural heritage;

- Community health and wellbeing.

Each theme contains a number of goals and strategies for achieving them [1]. The strategy is divided into three phases, known as Getting it spinning (2009–2012); Keeping it spinning (2012–2016); and Spinning on its own (2017–2020) [2]. This review coincided with the culmination of the initial phase, providing an opportunity to mark successes and identify potential improvements.

The initiative has been cited as a successful model of engagement and community development, and was highly commended in the Community Economic Development category at the 2011 Australian National Awards for Economic Development Excellence [3]. Our review starts with a description of Clermont. It then examines literature on futures and foresight, followed by literature on community engagement and development. Indeed, we propose that CPF could be described as an integration of these two domains into what might be called ‘engaged foresight’. Stakeholder perspectives on the nature and success of the CPF process is then presented, with discussion regarding the utility of such processes, limitations of CPF and opportunities for future similar processes.

2. Context

2.1. Clermont and Mining

Clermont is a rural town of approximately 3160 people, located about 290 km south-west of Mackay, Queensland (see Figure 1). It was established in 1862, and although it is now part of the Bowen Basin area of coal mining, agriculture predates coal mining in the region. Coal was first discovered at Blair Athol, 22 km north-west of Clermont, in 1964 [4] (see Figure 2). The central role of mining in Clermont’s historical and current circumstances is heavily emphasised on the Council website.

RTCA operated the Blair Athol mine for almost 30 years before its closure in November 2012. The mine was open-cut and employed around 170 employees and contractors, with approximately 30 roles retained after closure [5]. Meanwhile, another open-cut RTCA operation, Clermont mine, opened in 2010. While having an expected life of 17 years [6], this operation recently reduced its workforce; indeed, RTCA may seek to sell both the Blair Athol and Clermont mines [7].

Figure 1.

Location of Clermont, Queensland, Australia [8].

Figure 1.

Location of Clermont, Queensland, Australia [8].

Around the same time as CPF was launched, Isaac Regional Council produced its 2020 Vision [9] via a similar process, resulting in themes that closely resemble the CPF themes. This indicates a relationship between CPF and the Council. The present study includes an examination into whether, and if so how, stakeholders perceived this relationship. More broadly, we sought stakeholders’ reflections on the CPF process and related initiatives, formulating interview questions that explored key concepts in the literature, such as inclusivity, engagement, dialogue, capacity, and ownership. The next section examines these areas of literature, contextualised by a discussion of literature on foresight.

Figure 2.

Clermont’s museum celebrates the town’s long association with coal mining.

Figure 2.

Clermont’s museum celebrates the town’s long association with coal mining.

2.2. Futures and Foresight

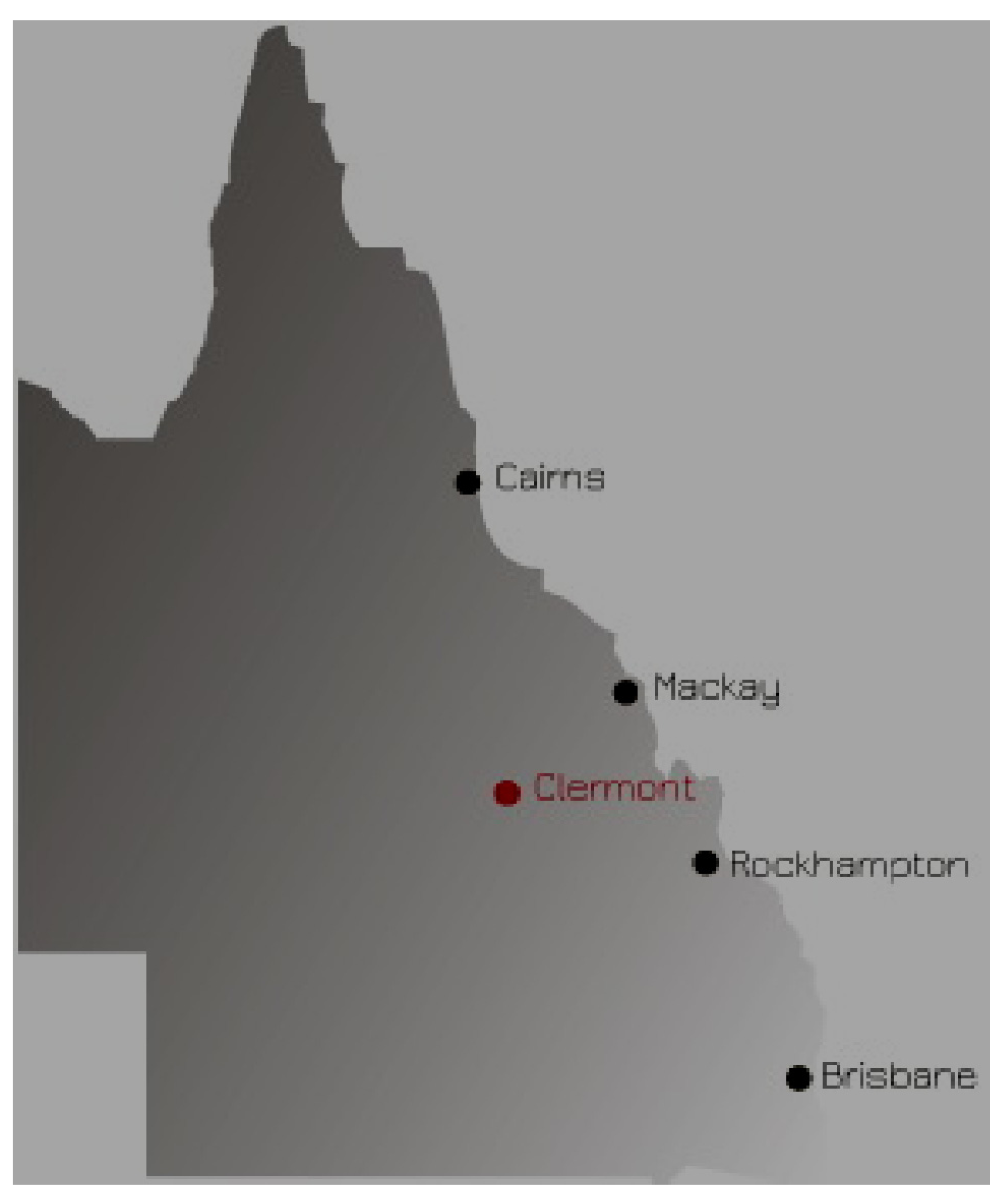

Although no particular model was explicitly applied in its design, CPF can be seen as an exercise in foresight, enabling us to examine it retrospectively through a relevant theoretical lens. Specifically, stakeholders participated in a planning process aimed at identifying a “common vision and purpose for the future of Clermont” [1]. Foresight is a sub-discipline of the broader futures area, and has been described as systematically embracing critical thinking concerning long-term developments, wide participation in decisions, and influencing public policy and strategic decisions to shape the future [10]. Three dimensions of foresight work can be identified: types of future orientation, depths of thinking, and alternative perspectives.

2.2.1. Types of Future Orientation

Voros [11] identifies four types of future, which can be illustrated in a ‘futures cone’ (Figure 3). The futures cone is a visual representation of various alternative futures. It shows that ‘plausible’ futures constitute a narrower range of scenarios than ‘possible’, and that ‘probable’ futures are narrower still. ‘Preferable’ futures—which the term CPF appears to represent—may lie anywhere within the cone. ‘Wild cards’ are low-probability, high-impact scenarios. Gidley [12], writing in the context of futures work with young people, adds ‘prospective’ futures, referring to a ‘readiness to act’, which aims to empower participants towards transformational change. More recently, Voros [13] added ‘preposterous' futures, referring to ‘impossible’ scenarios that lie outside possible futures.

Hence a foresight process may be oriented towards one or more types of future. Secondary data suggests that CPF explicitly focuses on a preferred or desired future, consistent with the objectives of harnessing effort and building capacity towards a positive, shared vision. Nevertheless, given the restricted breadth of thought that a ‘positive-thinking’ approach can engender (e.g., [14]), it might be asked whether focusing on the relatively subjective domain of preferences, values, and emotions, at the expense of potentially more likely scenarios, risks creating overambitious expectations that must be reined in later.

2.2.2. Depths of Thinking

The second dimension of foresight and futures work involves distinguishing between different levels or depths of thinking [15]. Three depths are described in the literature; ‘pop futurism’ (shallow trend-reading); ‘problem-oriented futures work’, which most closely aligns with the CPF process (conceiving and responding to future challenges); ‘critical futures studies’ (questioning world views and assumptions); and the deepest level, ‘epistemological futures work’ (considering foundational questions of human freedoms and expression).

Figure 3.

The futures cone (Reproduced with permission from Voros [11]).

Figure 3.

The futures cone (Reproduced with permission from Voros [11]).

2.2.3. Alternative Perspectives

The third dimension of foresight work draws on the identification of levels or depths of thinking to derive alternative perspectives, or ways of applying foresight work [15]:

- Pramatic foresight—envisages the future as a competitive space in which to seek advantage;

- Progressive foresight—seeks to redefine or transform prevailing practices, with a focus on concepts such as cooperation and sustainability;

- Civilisational foresight—seeks not only to transform but also to reconceptualise the human and social condition.

In summary, foresight and futures work can be approached from alternative perspectives and multiple dimensions. It can either focus on specific futures or consider various possible, plausible, and probable futures. It can occur at various depths of thinking from simply predicting the future to questioning epistemological assumptions. Finally, it can be applied for pragmatic, competitive purposes, for more progressive purposes, or for purposes that fundamentally reconceptualise the human condition.

While many approaches to foresight are possible, therefore, on initial impressions derived from secondary data, CPF appears to sit within these approaches as a project that focuses on a specific, preferred future, that operates at the depth of problem-solving, and that is relatively progressive in its application. Locating CPF thus, with respect to foresight literature, helps us to examine outcomes. Meanwhile, literature on community engagement and development can help us to examine the social processes involved in trying to achieve these outcomes. Both community engagement and community development are broad concepts that span extensive bodies of literature. For the purposes of this paper, we focus conceptually on the intersection of these concepts.

2.3. Community Engagement and Development

As explained previously, CPF did not explicitly involve the application of predetermined theoretical models. However, its design and principles suggest that project leaders were influenced by ideas from the literature on community engagement and community development. Examining this literature thereby helps us to locate CPF theoretically, especially in relation to the communication processes involved in designing and implementing CPF.

Since the 1990s, mining companies globally have embraced the concepts of community engagement and, perhaps to a lesser extent, community development. Indeed, the resources sector may be seen as leading other industries in this domain, following on from earlier adoption of terms such as sustainable development and corporate social responsibility. Yet the meaning of these terms is not always clear, making them difficult to implement in practice.

Taking ‘community’ and ‘engagement’ separately, the former can mean broadly “a group of people with a shared identity” [16]. Geographically, it can apply to anything from a small neighbourhood to a whole nation (e.g., the Australian community). It can equally apply to a virtual community (e.g., online forums), or a community of interest (e.g., the farming community). Hence Sarkissian et al. [17] offer the definition of community as “any group that shares a location, interests or practices”.

The mining industry tends most frequently to use ‘community’ geographically to mean those residents most closely neighbouring operations. However, this apparently simple definition becomes more complex in the presence of a fly-in-fly-out or drive-in-drive-out population, or where Traditional Owners have been displaced but retain a link to the land [18]. Engagement, similarly, has been used to represent a variety of activities from involving citizens, consulting stakeholders and building relationships, and is often used interchangeably with consultation, involvement, and participation. Clearly, interpreting the meaning of community engagement is challenging, though vital for the purpose of evaluating efforts to achieve it.

Literature on community engagement can be separated into normative principles of engagement and descriptive models of engagement.

2.3.1. Normative Models of Engagement

Many engagement models propose lists of principles that should underlie ‘good practice’ or ‘best practice’ community engagement, and are thus essentially normative in nature. These are often practitioner-oriented ‘how-to’ guides or ‘toolkits’ rather than academic discussions. Perhaps the most obvious to mention here is the Australian Government’s [18] Community engagement and development handbook. This publication provides guidelines specifically for the mining industry, drawing heavily on the principles of the Minerals Council of Australia’s [19] Enduring value framework.

The Australian Government’s [20] Principles for engagement with communities and stakeholders handbook has also proven highly influential in the resources sector. This document, which also draws substantially on Enduring value, proposes five engagement principles: communication, transparency, collaboration, inclusiveness, and integrity. Similarly, the AA1000 Stakeholder engagement standard [21] is described as a principles-based framework, founded on the three accountability principles of inclusivity, materiality, and responsiveness. Another influential body, the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) [22], proposes seven “core values” for developing public participation processes. These values actually sound more like normative principles, starting with “those who are affected by a decision have a right to be involved in the decision-making process”.

Such resources are seemingly endless. The Victoria Government [23] even has an A–Z list of ‘tools’ for ‘effective engagement’. While this explosion of guidelines perhaps makes the practice of engagement ever more unwieldy, a review based on literature, interviews, and workshops, offers a relatively practical overview of typical aspects of community engagement [24]:

- Scan for current or prior engagement work;

- Set goals and plan;

- Define the stakeholders;

- Manage expectations;

- Use group discussion;

- Use varied presentation formats;

- Allow for mutual influence;

- Foster trust, respect and ownership;

- Maintain contact and feedback;

- Systematically evaluate engagement.

2.3.2. Descriptive Models of Levels

The other principal dimension of engagement literature comprises levels or scales of participation. These progressive scales (Table 1) portray various points to represent the extent of community participation in organisational decision-making. All make useful distinctions between participatory approaches, tokenistic gestures, and all points in between. Essentially, scales range from non-participation, where an organisation simply provides minimal information and excludes any external input, to extensive participation, where an organisation delegates significant decisional authority to the community, the idea being to enable the community to control its own destiny.

Table 1.

Theorised scales of community participation.

| Author | Extent of community participation non-participation  extensive participation extensive participation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnstein [25] | manipulation and therapy | informing, consultation and placating | partnership, delegated power, and citizen control | |||||

| Wilcox [26] | information | consultation | deciding together | acting together | supporting independent community initiatives | |||

| Stewart Carter [27] | excluding | informing, educating | consulting, planning | decision-making | initiating action | delegating power | controlling | |

| Roberts [28] | persuasion | consultation | self-determination | |||||

| Crawley & Sinclair [29] | hostility | ignoring/ neglect | instrumental pragmatism | paternal sponsorship | multi-level interaction | two-way learning | enduring engagement | |

| Green & Hunton-Clarke [30] | informative | consultative | decisional | |||||

| Aslin & Brown [31] | informing | consulting | involving/participating | engaging | ||||

| IAP2[32] | inform | consult | involve | collaborate | empower | |||

A significant characteristic among these scales is the typical location of perhaps the most ubiquitous of these terms in mining discourses—consultation—towards the centre (noted in bold). That is, consultation is more than just providing information, but less than active community participation. Furthermore, many reports and practice guides refer to consultation, engagement, involvement, and participation almost interchangeably, yet the above scales help us to consider the degree of participation in different practices. This is not to imply that greater participation is always preferable, however, and many authors (e.g., [33]) suggest that the degree of participation should suit the circumstances.

The first operating principle of CPF is to “strive toward a collegiate, inclusive, collaborative and community-driven approach” [34], suggesting a relatively participative approach. This is consistent with an orientation towards regional development that is founded on principles of community development.

2.4. Community Engagement for Community Development

CPF could be seen simplistically as an exercise in economic development and/or regional development. However, those terms explicitly privilege economic growth, whereas the Clermont case apparently has wider characteristics that correspond more closely with community development, such as an emphasis on community participation and resilience. According to Jim Cavaye [16], a leading community development practitioner in Australia, community development is not just about growth, and indeed it can occur without growth, depending on what people value in the community. Equally, it is more an ongoing learning process than a planning process. Community development seeks to build physical, financial, human, social, and environmental capital. This is consistent with the Five Capitals model, a framework for sustainability that emphasises the integrated or interconnected nature of these capitals and the need to avoid trade-offs between them [35]. Thus a characteristic outcome of community development, Cavaye proposes, is communities that are better able to manage change.

While a complete review of community development is outside the scope of this paper, it is pertinent to identify themes in the literature that characterise both community engagement and community development. Themes, concepts, terms, or narratives that appear in both areas are ‘ownership’, ‘capacity-building’, and ‘dialogue’.

The idea that the community should ‘own’ any community development and engagement process appears widely prevalent. To illustrate, Miles et al. [1] identify “strong community ownership of outcomes” as a key component of a regional approach to community development. Similarly, two key planning documents that preceded CPF—the Whitsunday Hinterland and Mackay Regional Plan (2005) and the Central Queensland Regional Growth Management Framework (2002)—both identified community ownership as an objective [1]. Additionally, Isaac Regional Council’s [9] 2020 Vision identifies community ownership as something that “will help us to achieve future aspirations and shared visions”. In practice, however, achieving such ownership commonly appears to present a challenge, and is associated with problems such as poor follow-up resourcing, lack of true community engagement, and a top-down approach [1].

So what does ‘community ownership’ mean? Clearly this is not ownership in the tangible sense of property rights, since it refers rather to a relational or social process. Exemplifying this intangibility, Raeburn et al. [36] refer to community ownership alongside “growing capacity” and “visionary goals” as a “sense” of contributing to effective community capacity-building (see below). Cavaye [16] equates community ownership with community involvement, principles of community development whereby the community makes and implements decisions and the community’s initiative and leadership instigate change.

A related term is ‘community capacity-building’. Cavaye [16] suggests that this term is essentially synonymous with community development, although there may be differences in emphasis. Smith, Littlejohns and Thompson [37] define community capacity-building as “a process of working with a community to determine what its needs and strengths are, and to develop ways of using those strengths to meet those needs”. This definition fits an ‘appreciative inquiry’ approach, which is a form of action research that identifies and explores the strengths in a particular situation to respond to a challenge. Such an approach can be empowering and help a community to realise its full potential. Similarly, but more specifically in a health context, Labonte and Laverack [38] define capacity-building as enhancing a community’s abilities to identify and act on health concerns. According to Verity [39], community capacity-building is claimed to deliver multiple benefits, including empowerment of individuals and groups, development of skills, knowledge, and confidence, increased social connections, and responsive service delivery and policy. A critical factor contributing to its mainstream popularity appears to be its emphasis on empowerment and a ‘bottom-up’ approach, in contrast to emphasising deficits [36].

On this evidence, community capacity-building appears unproblematic. Raeburn et al. [36], however, suggest that its focus on abilities or competencies tends to downplay the role of social relationships. Makuwira [40], meanwhile, asks critical questions such as: who determines the process for community capacity-building, and who evaluates whether capacity has been built? Smyth [41], similarly, writing in the context of education and disadvantage, critiques community capacity-building as something that delegates responsibility to communities while blaming them for their own problems. Instead, he advocates ‘community organising’, a more overtly political approach in which power relations are made more explicit, participation is an end in itself, and those at the periphery of decision-making processes are brought into those processes (see also [40]).

Another prominent narrative common in both community engagement and community development discourse is ‘dialogue’. The concept of dialogue derives from communication perspectives that distinguish between monologic or conduit communication, where a sender transmits ideas and truths to a passive receiver, and dialogic communication, which acknowledges contestability and disparities of power in constructing meaning (see, for example, [42]). Monologic communication is suggested by practices such as ‘telling’, ‘educating’, and ‘informing’. Dialogic communication is suggested by practices such as ‘listening’, ‘hearing’, ‘negotiating’, ‘understanding’, ‘respecting’, and ‘sharing’ [43]. This distinction is evident in the scales of community participation described above, in which terms towards the left (e.g., exclude, inform) reflect relatively monologic communication while those towards the right (e.g., engage, empower) reflect relatively dialogic communication.

Perhaps the key attribute of dialogic community engagement is its emphasis on relations of power. It was proposed above that circumstances should determine the degree of participation, rather than assuming that greater participation is always preferable. Yet who defines the circumstances? Most guidelines and toolkits for community engagement locate the organisation at the centre of relationships, with stakeholders peripheral or subordinate. Perhaps unintentionally, this arrangement implicitly privileges the organisation’s dominant worldview and underlying assumptions. The potential of community engagement can be intrinsically constrained, therefore, by a power structure in which a company or government usually determines whether and how to allow people to participate [33].

The values and principles of dialogic community engagement can be seen as broadly consistent with the deeper levels of foresight work described earlier, and with the notion of ‘community organising’. These ideas operate not only at the everyday level of solving problems but also at discursive and epistemological levels that pay attention to ways of constructing and constraining our ways of knowing.

2.5. Operationalising Dialogic Community Engagement

Just as the deeper approaches to foresight work appear challenging to apply, the emphasis on power relations can make the idea and practice of dialogic community engagement appear confronting. Yet Sarkissian et al. [17] attempt to address the challenge through their book Kitchen table sustainability. Their model operates in the context of an overarching goal of sustainability, and comprises seven components: education, action, trust, inclusion, nourishment, and governance. Critically, while drawing heavily from community development discourse, it is written not with government or organisations as the point of departure, but from the perspective of communities themselves. Specifically, it is described as a values-based approach to help communities engage with the challenges of sustainability and to develop localised solutions [17].

The Sarkissian model is strongly influenced by the idea of coproduction [44], in which decision-makers and community members share power and responsibility in planning and negotiate how resources should be expended. These ideas resonate closely with dialogic community engagement. They are also reflected in the aim of CPF for the community to be deeply involved in developing a shared vision and plan. Such dialogic principles are exemplified in the stated purpose of the steering committee, which is to constitute a “collaborative, stakeholder-driven community forum”, and in its principles, which include to “strive toward a collegiate, inclusive, collaborative and community driven approach”, and to “seek equal and genuine partnerships and alliances” [1].

In summary, the available documentation suggests that CPF could be described as an attempt at ‘engaged foresight’ that was informed by ideas from community engagement and development discourses. That is, CPF apparently seeks to harness community involvement and effort in describing a mutually desired future for Clermont, and in delivering a plan and strategy for achieving it. The above discussion has identified how such a process could be practised. A foresight exercise can be oriented towards various alternative futures (probable, plausible, possible, preferable, and/or prospective), can operate at various depths (pop, problem-oriented, critical, or epistemological), and can consider alternative perspectives (pragmatic, progressive, and/or civilisational). CPF focused on a specific, preferred future, and appears most closely aligned with problem-oriented foresight and a progressive perspective. A key task of the present study, then, was to elicit stakeholders’ views on the degree to which CPF has operated in line with these dialogic aspirations and the extent to which this preferred future is being realised.

3. Methods

In mid-2012, mining company Rio Tinto Coal Australia (RTCA) asked the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) to review CPF. CSIRO researchers used a case study approach to document the experiences of stakeholders involved in the process itself and in subsequent related activities.

Our methodological approach comprised a combination of interpretive interviews and art engagement with 17 participants. The interviews followed a semi-structured format in which we asked questions around: awareness of and involvement in the CPF process; perceptions of inclusivity and community participation; tangible and intangible outcomes; and perceptions of progress of CPF. Follow-up questions and prompts were asked as necessary, and to take advantage of the specific expertise of each participant.

The researchers asked the CPF Implementation Officer to identify potential participants on the basis of having at least some knowledge of CPF. This potentially biases the research process towards those with favourable dispositions towards CPF, but was the most practical approach since it facilitated access to informed stakeholders. To ameliorate bias, participants were repeatedly asked to consider and reflect on how other individuals and groups in the community might understand and experience CPF and associated initiatives.

The participants comprised four RTCA employees, four business owners, two farm owners, two school teachers, two council employees, one local councillor, one real estate employee, and one consultant. Four participants were also members of the CPF Implementation Committee. Thus, some were deeply involved in CPF, some had moderate involvement, while others had passing knowledge.

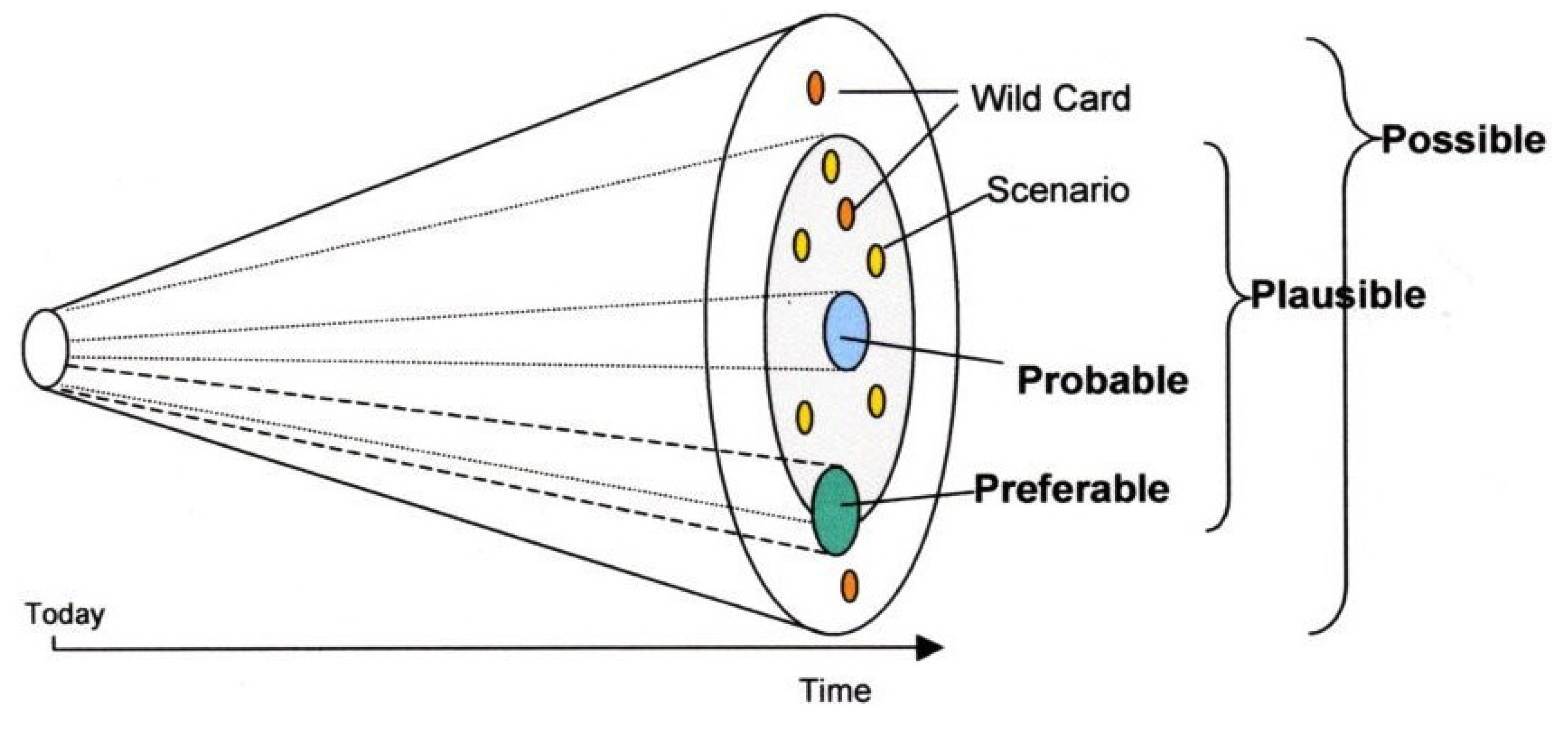

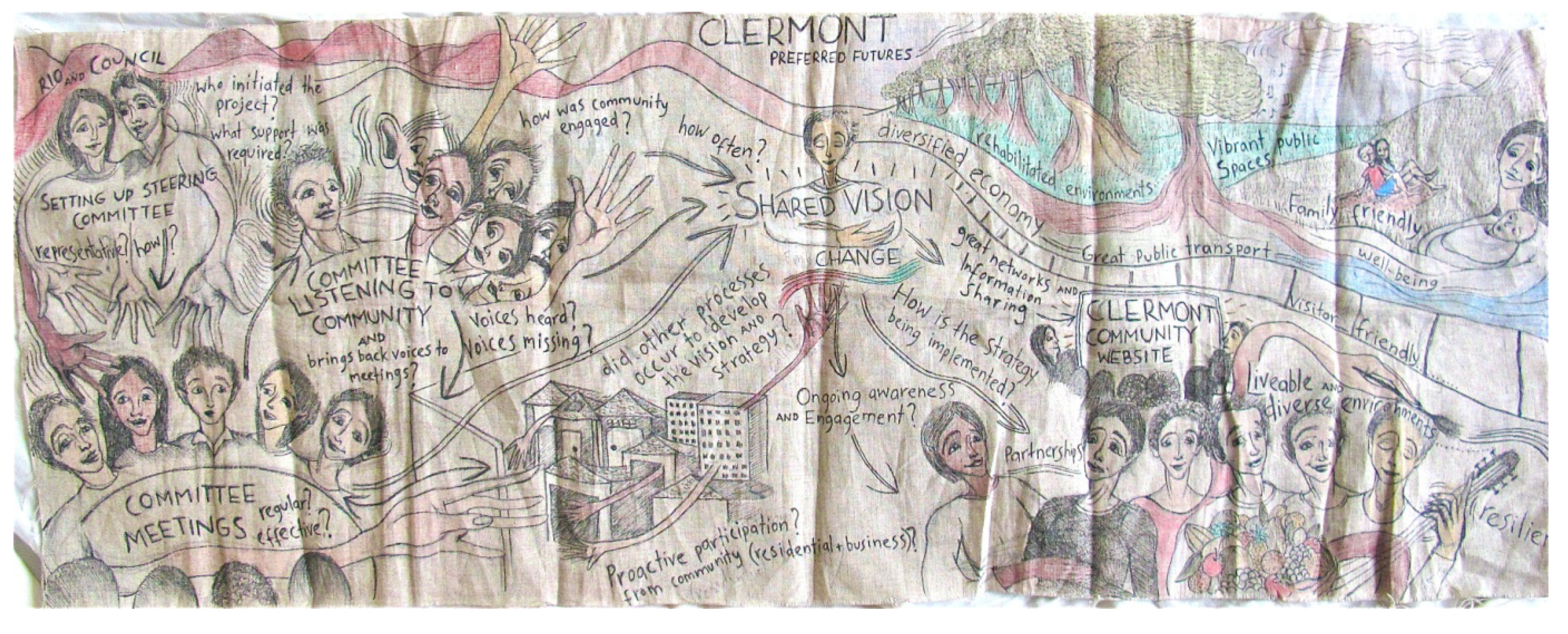

3.1. Using Art during the Interview Process

To support the interview process, an artistic representation of the CPF process and vision was created by one of the researchers. This was presented to participants during the interviews. It was intended as a creative prompt to refresh people’s memories of the process, to help them visualise the different actors and processes, and to stimulate response. It also enabled greater insights to be drawn from the individual data sets, and facilitated clarification and/or confirmation of meaning (i.e., responses to the art versus responses to traditional verbal questioning). The design of the artwork (Figure 4) was informed by reviewing available literature on CPF. This material included various reports, a conference paper, media articles, company documents, and CPF documents. Hence it was a researcher’s interpretation of the process from prior reading. It was drawn on cotton fabric, and measured approximately 50 cm long.

Visual art has been found to stimulate and improve dialogue, in terms of depth, length, direction, and level of engagement in conversation [45]. Wikström [45] proposes that “art provides scenes for a mental walk”. In this way, art can help people form, gather, and articulate their thoughts. Art is nourishing for the visualisation of thought [45], and can help with expression and articulation of feelings. This is particularly relevant for exploring concepts such as community development and engagement, which embody complex elements including trust, values, social cohesiveness, and community ownership. Whereas participants may experience difficulty in articulating these concepts verbally, they may relate to an aspect of artwork that represents trust, for example.

The artwork was introduced to participants in the second half of the interviews. To gauge the extent to which it >represented participants’ experiences and perceptions, they were asked questions such as: “Does this accurately represent who has been involved in CPF?” “Does this accurately represent the processes that have occurred?” “Is anyone/any group that was involved, or should have been involved, missing here?” “Are there any processes missing, or any that should have occurred?” More generally, to evaluate the efficacy of art engagement, participants were asked: “Do you find the artwork useful in thinking about the CPF process?” and “Do you think art could be helpful in engaging the Clermont community with CPF?”

Figure 4.

The complete artwork used in interviews.

Figure 4.

The complete artwork used in interviews.

4. Stakeholder Experiences

The findings from the interviews can be grouped into three broad categories: perceptions of outcomes; perceptions of communication, consultation and participation; and perceptions of inclusivity and representativeness of the CPF process and associated initiatives.

4.1. Outcomes

In Section 2.2, we suggested that the foresight literature helps us to locate CPF in terms of intended outcomes. That is, based on secondary data evidence, CPF appears to have been designed to focus on a specific, preferred future, to operate at the depth of problem-solving, and to be relatively progressive in its application. To interrogate these classifications, we analysed how participants described tangible and intangible outcomes of CPF. In the interviews, participants were prompted where necessary by citing themes and objectives from the original CPF plan and the 2011 updated strategy. They were also asked to assess progress against their expectations.

Participants closely involved in CPF were able to cite a number of direct outcomes. Conversely, participants not closely involved struggled to identify outcomes.

CPF aims to deliver various tangible outcomes under the rubric of a ‘preferred future’. These include: new businesses; new infrastructure and transport services; new networks and alliances; new art, cultural, sporting, and recreational initiatives; new environmental and climate-change programmes, and new health, social, wellbeing, and youth services.

Most participants struggled to identify tangible outcomes. However, when prompted with some of the specific objectives listed above, some participants were able to identify the following:

- formation of the Clermont Community and Business Group (CCBG), aimed at facilitating economic diversification by increasing population, promoting ‘opening’ of new industrial land, seeking external investment, and increasing housing availability and affordability;

- development of an Urban Design Master Plan for Clermont, to be used in planning activities by Council and community organisations;

- launch of Agricultural Studies Department at Clermont State High School (see Figure 5);

- extension to Clermont kindergarten and day-care centre;

- a study to establish the feasibility of a biofuel industry at the Blair Athol site;

- new housing developments, partly to support Rio Tinto’s residential workforce targets;

- work on the Hood’s Lagoon area;

- repainting disused railway carriages depicting Clermont’s industries; and

- work with local businesses to make Capella Street (Clermont’s main street) more visually appealing.

Figure 5.

Example of a CPF outcome.

Figure 5.

Example of a CPF outcome.

However, only those closest to the process (i.e., Rio Tinto employees, Council employees, and CPF committee members) were able to name these outcomes as specific CPF initiatives. Even some of these interviewees were unsure about the derivation of some outcomes:

“Even for me, there becomes a blurring of what is what. There are footpaths popping up around town, and I’ve asked the question, and when we can’t think of another answer, we say ‘Oh, that’s probably [an initiative of] Preferred Futures’.” (P15).

Other participants were aware of some of the outcomes, but unsure who was responsible for them, typically assuming that they were Council initiatives. Conversely, they also identified some projects, such as road resurfacing, as possibly CPF initiatives, even though such projects were not directly associated with CPF. When prompted by the researchers naming certain initiatives, participants expressed some recognition but were typically unaware of specifics. Clearly, there was some confusion regarding what CPF had actually delivered. One participant suggested that this confusion may be exacerbated by the Implementation Officer being a Council employee and wearing clothes with Council logos.

Many participants saw this inability to link CPF outcomes to CPF itself as a significant issue, and one proposed that strengthening this link could deliver valuable community development outcomes:

“[The CPF Committee] organised the repainting of the trains but community probably doesn’t know this. It would probably be valuable if the community knew we did this because it could create more community cohesiveness.” (P3).

A lack of awareness of CPF outcomes, alongside an inability to attribute certain outcomes definitively to CPF, may be partly responsible for most participants, including those who were able to identify several tangible outcomes, viewing progress towards tangible outcomes as frustratingly slow. Even one Rio Tinto participant commented:

“I don’t fully understand what the roadblocks are—why some projects haven’t been delivered.” (P13).

Perhaps the dominant theme of CPF is an economic one—specifically, the objective not simply of maintaining economic growth, but of building resilience through economic diversity, thereby avoiding dependence on mining. Indeed, when asked what CPF meant to them, participants conceptualised it foremost as a vision for the town’s future beyond mining. While diversity and resilience are difficult to measure, being largely a matter of subjective assessment, some aspects are tangible. As one participant noted, since the 1990s, as businesses and services have sought to remain financially viable, Clermont has lost four car dealerships, three banks, a chemist, a passenger and freight railway, and a magistrates’ court. Clearly, achieving economic resilience is a challenging task in the face of historical and global trends.

Achieving economic diversity is perhaps less problematic though for Clermont, which has agricultural industries that predate coal mining, than for some neighbouring towns, which are more exclusively ‘mining towns’. To illustrate, one participant described Clermont as “a town with a mine, not a mining town” (P13). Nevertheless, the imminent closure of Blair Athol, and media coverage suggesting that the expansionary years for coal mining were ending, had reignited the perceived importance of economic diversity.

Most participants assessed that little progress had been made towards economic diversity, but acknowledged that it may be too early to expect significant outcomes. Some had seen a small increase in tourism, but noted that this was hampered by the closure of the Clermont museum over a year previously. Those who proposed otherwise saw this progress as catalysed by stimuli other than CPF. One argued that more diversity had been facilitated by technologic advances. Another proposed that more businesses had been attracted to Clermont because housing costs in surrounding towns were higher, and because of Clermont’s central location regionally. Another saw new industries arriving but only to support the mining operations.

On this evidence, it is difficult to be optimistic about the town’s economic resilience, or at least about perceptions of resilience. There were exceptions, however. One participant suggested that community reaction to the last economic downturn demonstrated resilience, because “we did not have a community in panic” (P1). This observation may be linked to other participants’ observations, which relate to the cyclical pattern of economic activity that characterises Clermont. Two participants proposed that slower economic times are welcome, providing an opportunity to ‘re-charge’ and “to take a breath—so long as it doesn’t last too long” (P2).

Reflecting the pre-existing diversity of the local economy, participants suggested that, if mining were to cease immediately, the town would suffer some—but not fatal—economic loss, and some saw CPF as helping to underpin this resilience:

“Clermont was a town before [Blair Athol] came along, and it was based on the farming. Obviously it wouldn’t be as large, but I think it would still exist, because it is a hub for a massive area... [CPF] has made people not lean on the mine as the answer to all their problems.” (P10).

Beyond economic resilience, participants made more favourable assessments of intangible outcomes. Most notably, many considered that CPF had helped to bring the community together—to make it more cohesive. The ‘involving’ process was viewed by some as the most valuable outcome. One participant proposed that CPF brings “huge opportunities to participate and have a voice” (P4). Another (P3) described their positive experience of involving youth in implementing the CPF strategy, whereby the CPF committee had invited schools to participate in community activities such as cleaning areas of Clermont.

These findings enable us to refine our classification of CPF within the foresight literature. Firstly, they confirm that the project focused explicitly on a ‘preferable’ future, rather than on broader alternatives such as plausible and possible futures. They also suggest that, even though the project is restricted to this narrow conceptualisation, community members have trouble identifying the details relating to this ‘preferable’ future. Secondly, the findings confirm that CPF operates at the depth of problem-solving; there is no evidence of effort to question world views and assumptions, as in critical futures studies. Thirdly, they suggest that CPF may not have been as progressive in its perspective as indicated by the secondary data. While the secondary data convey an impression of an orientation towards cooperation and sustainability, the bulk of participants’ statements revolved around whether Clermont could continue to compete economically, rather than around a need to redefine or transform prevailing practices. In terms of foresight studies, CPF might be reclassified as focusing on a ‘preferable’ future, as a ‘problem-solving’ exercise, and as being applied in a relatively pragmatic fashion. On this evidence, the capacity of CPF to realise its transformative objectives appears constrained by a relatively conservative conceptualisation of foresight work.

This leads us to question whether CPF was as participatory as intended. Many participants saw great opportunity to improve the level of community engagement and involvement with CPF, and envisaged how this might enhance outcomes: “if the community got more involved, there would be more community ownership over CPF” (P3).

4.2. Engagement: Communicating a Preferred Future

Above we noted that CPF appears from secondary data to constitute a relatively participative approach, in terms of scales of participation in the literature. That is, it is presented publicly in terms suggesting extensive community participation in its design and implementation. Our findings indicate that participants’ experiences often failed to match this rhetorical impression of dialogic communication.

4.2.1. Communicating CPF Processes and Outcomes

There was general agreement that most community members knew little about CPF, that many may not even know of its existence, and that very few would be familiar with the vision. One long-standing committee member (P3) admitted that even he would struggle to state the vision. Another participant (P7), not a committee member, listed people he would like to see as committee members, not realising that those he identified were already committee members. These findings seem surprising given that CPF has been considered a leading example of regional development, but perhaps reflect its focus on planning rather than operations. Some suggested that there was greater awareness of CCBG, probably because of its more operational role and its prominent office presence in the town centre.

Many participants identified the need to link people’s expressed concerns with actual outcomes, in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of CPF, and to enhance community ownership.

“You would imagine, at the local level, if you’ve got a local initiative, that gives you the greater opportunity to have face-to-face conversations, input and involvement, and it’s quite specific to your community. You can see pretty much immediately the results of your ideas or your suggestions; you might be able to change something.” (P15).

Participants who were relatively aware of the CPF outcomes acknowledged that these outcomes could be communicated more effectively. Several participants identified that a lot more could be done to share and celebrate CPF achievements, and that there would be great value in achieving this:

“If there was more awareness across the community [in the vision and CPF processes], there would definitely be an increase in resilience and confidence amongst the community.” (P7).

Many participants agreed that the Clermont Rag, the local newspaper produced by Council, would be a useful forum for communicating CPF news, achievements, forthcoming projects and goals, and how to get involved. Many also agreed that visual materials might help to invigorate engagement and communication.

Signage describing a project as a CPF initiative was mentioned by participants as another key and underused communication tool. While there was some concern that funds for signs may be better spent on the actual initiatives, some participants indicated that clear visual aids would assist in connecting the CPF process to its achievements, and help engender ownership of the CPF itself:

“It’s hard to promote something without something visual, so I think if people can’t see the finished result, but if they can see a poster or a sign that tells them what it’s going to look like when it’s finished, they can visualise it, and they get excited about what’s coming.” (P13).

These issues concern knowledge and awareness of CPF—in other words, they elucidate the effectiveness of the ‘informing’ end of the participation spectrum, which generally reflects monologic or conduit communication. The literature suggests that engagement also comprises consultative and participative processes, which tend to reflect a more dialogic approach to communication, and hence which are sensitive to the role of power relations in constructing the meaning of contested concepts such as ‘community’ and ‘engagement’.

4.2.2. Consultation and Participation

Those participants not directly involved with CPF were unaware of how the committee consults the community. Furthermore, they insisted that they would be happy to be more involved if asked. Yet those closely involved countered that participation opportunities had been available for those who wanted them, and identified apathy as an alternative explanation for lack of community input:

“It was through word of mouth, through advertising—that type of thing. So people knew what was happening at the time.” (P12).

Many participants summarised the situation as one where participation opportunities had been available but not necessarily widely promoted. For instance, one described the consultation process for the Urban Design Master Plan as requiring community members to visit an office, as opposed to ‘reaching out’ to the community more proactively. One participant, when viewing the artwork, identified listening and sharing as key aspects that are missing from CPF. Several participants commented that the artwork represents what is ideal and what was intended from the outset, i.e., dialogic community engagement, but that this had not been the reality:

“Going to the community and bringing voices back has been a weakness—we could improve on this for sure.” (P7).

One exception was a CPF committee member who implied that there was no need for ongoing dialogue beyond the initial consultation process:

“We’ve already consulted the community, so we know what they want.” (P3).

Similarly, a participant (P1) closely involved in CPF explained why it was difficult to engage the whole community:

“Some people, you know, you’re just never going to make happy, so you just wink and nod.” (P1).

More typically, though, wider community engagement was seen as desirable, and participants wanted to see CPF engagement activities improved. One of the school teacher participants (P8) insisted that “people are interested to have a say for our community”, and that “community would provide input if they were aware of avenues to provide input”. Participants differed in conceptualising how this might be achieved in practice. Some saw community involvement as a challenging task:

“Sometimes you have to be quite energetic to ensure that you involve others.” (P15).

Others, conversely, saw the process as relatively simple, for example through short house-to-house surveys or simply by standing outside the newsagent at the weekend:

“Call us, invite us—come to where the people are... It’s a small town, so it shouldn’t be too hard to gauge, or get some sort of snapshot, of what people think about a certain thing.” (P8).

What was not clear, then, was whether the prevailing approach was perceived as adequate by community members themselves. As discussed above, though, greater participation in decision-making is not necessarily preferable in all situations, and the appropriate level of participation may depend on the context. In some cases, simply providing information is adequate for most people. The significant point is that, when informing is appropriate, it can be relatively effective or ineffective, just as engagement can be relatively monologic or dialogic.

At the ‘informing’ end of the participation scales, one participant argued that “the information is there if you want it, but most people wouldn’t know where to get it” (P10). More commonly, participants largely agreed that more effort was needed to inform community members not only of CPF outcomes, but also of CPF committee members, activities, discussions, and opportunities for community input. For example, proceedings of CPF committee meetings were rarely disseminated, which accounts for the common view expressed that most community members would know little of CPF, its committee members, or its operations.

Most participants thought it would be useful to provide a regular CPF update in the Clermont Rag. However, some participants, acknowledging that this paper is published by the Council, reflected that distinguishing CPF matters from Council matters would be critical in helping to engender community ownership of CPF. Several participants identified the significance more broadly of distancing Council from CPF:

“People are turned off by Council; they associate it with things not getting done. So if we made it clear that this is a community-owned project that should generate greater interest and engagement.” (P4).

While there is some concern, therefore, around relationships between key actors, many saw the appointment of an Implementation Officer, funded by Rio Tinto and the Council, as “absolutely a critical part” (P5) to the effectiveness of CPF. Yet it was also noted that, during a period when CPF had no Implementation Officer, CPF itself continued to function. A likely reason for this is the idea that CPF represents a model of relationships between the CPF Committee, CCBG, Council, Rio Tinto, and the community. Perhaps the most significant function that the Implementation Officer performs, therefore, is a communicative one—acting as a point of contact for community members, and as coordinator and facilitator of relationships.

Two participants (P1 & P5) acknowledged that a communications strategy did not exist, nor did any formal feedback loops among the various stakeholders. Communications in general, therefore, were identified as a key area needing improvement, and one which, if done well, may significantly enhance the value and success of CPF. Hitherto, it appears that engagement had not lived up to CPF’s aspirations of a “collegiate, inclusive, collaborative and community-driven approach” [34]. Further insights into communication and participation arise by examining the inclusivity of those communications and the representativeness of CPF structures.

4.3. Inclusivity and Representativeness

CPF documents speak of the critical role of community ownership if CPF is to be anything more than a plan [34], consistent with a ‘bottom-up’ approach to planning and extensive community engagement [1]. As Miles et al. [1] put it, “a significant success factor in the Preferred Futures Plan will be the ability of the community to proactively master their own destiny”. The objective of community ownership, therefore, appears to require a highly inclusive or participatory approach.

4.3.1. Inclusivity of CPF Processes

Several participants noted that engaging ‘ordinary’ community members in CPF is desirable in principle but presents an ongoing challenge in practice. The most common explanation for this was that most people are just not especially interested in participating in community planning processes.

Yet this picture of a disengaged community is not reflected by the Clermont Community Group page on Facebook, whose aim is “To give the people of Clermont an avenue to voice the issues that matter to them”. This group had 553 members on 14 November 2012 (the month after our research visit), and had grown to 1063 on 10 October 2013. While it is impossible to know how many of these reside within the community geographically, or how many members regularly participate, this membership level suggests that people are willing to engage in community issues, but not necessarily via formal processes. Some participants suggested that committees represent intimidating forums to which only a privileged elite is granted access. While such an exclusionary regime appears to be the very opposite of the intention of those committee members interviewed, the finding that such a perception exists suggests that processes for engaging the broader community could be significantly improved.

For example, the process for appointing committee members to CPF was not clearly understood by all participants. The committee comprises seven individual members plus the CCBG Executive, which is represented by two further individuals. Prospective members are assessed against a ‘matrix’ of criteria developed by the Implementation Officer, Council, and Rio Tinto, and Council must pass a resolution to accept new members. Yet to be considered, someone must have reason to submit an expression of interest, and a space must be available. Those participants already on the committee, when asked how they were appointed, suggested that this had occurred through a relatively informal invitation process, in which they were approached by existing members, rather than through a democratic selection process:

“We never got anybody that we didn’t tap on the shoulder. Nobody will stand up... We get the people who we think should do a fair job... We’d love to have people from the street, but I know they don’t put up their hands... I would love to have two or three, four or five stand up against me—at least then you know the town wants something done... I didn’t even have to go for re-election; I was automatically, after the due date, reappointed.” (P12).

Those not on the committee, when asked how they might become committee members if they chose to, were unable to identify any mechanism for applying or nominating. A participant (P7) who was on the committee was unaware of what formal processes enable community members to apply to join the committee. This opaqueness was muddied further by the finding that some participants were unable to name current committee members, and were unsure how to ascertain their identity. They simply assumed that the committee probably comprised people from Rio Tinto and the Council. This suggests significant shortcomings not only in the processes used to appoint CPF committee members, but also in communications between the committee and the broader community.

4.3.2. Representativeness of CPF Committee and CCBG Membership

In the artistic representation of CPF, business and community were portrayed as contributing equally to the process. When asked to consider the extent to which this reflected reality, nearly all participants judged that business actually had greater influence and community much less influence:

“The business part should be twice as big and the community part much smaller.” (P13).

This finding raises the question of how representative CPF is of community diversity. Four participants were CPF committee members. These people appear to have a genuine commitment toward the community, and they conveyed considerable enthusiasm for CPF. Many are involved in several committees and community projects, with one commenting that his motivation was “mainly to make this town a better place” (P12).

Participants closely involved in CPF acknowledged the democratic shortcomings noted above, but have struggled to address them. They genuinely wanted greater community involvement, but found it difficult to engage broad community interest. They had confidence that the current committee members (meaning, in some cases, themselves) effectively represented the broader community through informal networking. It was for this reason, they conjectured, that committee members were virtually self-appointing, by virtue of their apparent status as ‘community leaders’. In this view, there is little point in soliciting expressions of interest for the committee when it is obvious who has the time, interest, and commitment.

The risk, though, is that a relatively closed, undemocratic approach inadvertently leads to perceptions of unrepresentativeness and exclusion. One committee member (P7), for example, noted that “education and youth voice[s] are now missing from the Committee”, although they had been present previously. Another (P12) proposed that “we need new ways and ideas on the committee”, having observed that the average age of fellow members is about 50: “not good because you’re set in your ways and stuck for ideas”. Another noted that the same faces appear on various committees, and wanted to see more competition for his committee position to give the process more credibility.

The current situation provides fertile ground for cynicism, as suggested by some participants not directly involved in CPF, who typically saw committee meetings and CPF itself as a ‘talkfest’ (P9). Nevertheless, participants identified real constraints on community members joining committee processes, perhaps most notably the culture of long working hours, epitomised by 12-hour shifts at the mines:

“Getting volunteers to do anything in this day and age is just impossible. My ideal situation would be to get rid of 12-hour shifts... That’s what stops people from volunteering—they’re too tired....” (P11).

CCBG, meanwhile, was described by some participants as the “delivery arm” or “working arm” of CPF, and most viewed the two as closely interwoven. Some argued that this arrangement makes it difficult for CCBG to act independently, while others viewed this proximity as beneficial. Hence the representativeness of both bodies is equally significant in determining the degree of community ownership of CPF. The relatively visible, tangible, and accessible nature of CCBG potentially enables it to form a closer relationship with the community than CPF. Indeed, one participant described CCBG as “a voice for the people of this community” (P13).

Participants noted that CCBG evolved from—and effectively replaced—the Clermont Progress Association, a body instituted to represent the community’s interests broadly. The adjacent location of the terms ‘community’ and ‘business’ in CCBG suggests equal focus on community and business interests. Yet most participants viewed CCBG as a predominantly business-focused group, since its members are mostly local businesses. Some noted a general impression that CCBG is open for businesses only to join, and that many probably think of CCBG effectively as a Chamber of Commerce:

“A group of businessmen who ... have a vested interest in the economic wellbeing of the community. And there probably is some cynicism there ... that they’re in it to line their own pockets.” (P14).

Hence, some suggested that, while committee members are genuinely committed to the community, they may have been motivated to join the committee by perceiving a personal benefit from doing so. This is particularly a concern for those members who are also business owners, who may see CPF as a mechanism for expanding their economic interests. As one put it:

“I’ve learned that if you can make the town a better place, you get more people in town, which generates more [business].” (P12).

It may be argued that this kind of ‘enlightened self-interest’ is justified if it produces outcomes that benefit the community, and even at this relatively early date CPF has brought beneficial outcomes. Clearly, however, challenges remain in shaping CPF into something that is genuinely true to its original aspirations of community engagement, development, resilience, and ownership.

4.4. The Role of Art

As already suggested, using art to engage participants prompted additional insights and responses that we reflect upon here. In particular, after considering the project artwork, participants often appealed to the efficacy of visual aids in community engagement. The need for “something visible” (P11) to augment the inadequacy of “words and reports”(P8) describing CPF and its successes was evident. Participants were also supportive of using visual media to describe the broader CPF vision and process, for example through a mural. Such a mural, some proposed, might communicate the CPF breadth and scope, key actors and stakeholders, and points of entry for community participation and influence.

Another participant (P13) explained that viewing the artwork during the interview helped her understanding of the CPF process, as it was “easier to grasp” and more engaging than a report. The artwork enabled her to see (at least ideally) who is involved, what roles they perform, and how information flows. She also saw value in using art to help bring meaning not only to CPF itself, but also to opaque concepts such as sustainable development:

“No-one understands what sustainable development is… Help them visualise it… Pictures and images would help community imagine the visions and plan, and to excite them”. (P13).

As well as helping to convey meaning, participants suggested that art could raise enthusiasm for the CPF process:

“It would be great to see a positive future… it would enthuse… people would go ‘yes, this is what we want’.” (P15).

In summary, this activity provided a richer data set for analysis, allowing for different types of data to be examined and incorporated. In particular, visual representation prompted participants to challenge the nature of events depicted, to compare the ‘official’ version of events with their experiences of them, to reflect on the relative influence of different actors, and to consider the potential of art to help broaden and deepen engagement in future.

5. Conclusions

This review sought insights from key stakeholders to consider how effective CPF has been as a community engagement initiative designed to harness collaboration towards a shared vision. Inevitably it has limitations. Most notably, we relied on the CPF Implementation Officer to identify prospective participants, potentially biasing the findings. A more comprehensive review would directly solicit the views of the general community. While the views expressed here may genuinely reflect community opinion broadly, it is impossible to be sure, and it is quite likely that certain demographic groups have been underrepresented. In particular, although the researchers tried to access local Aboriginal voices, none are present. If we are to pursue research with reflexivity, this is a significant omission given the knowledge that Aboriginal voices have been institutionally marginalised in western research approaches (e.g., [46]). This omission may have resulted in findings that implicitly assume western notions of development, land, and progress. Our conclusions must therefore be approached with an openness to alternative conceptualisations.

In drawing conclusions, perhaps the most significant question is whether a CPF-type process could be usefully applied elsewhere. Most participants were enthusiastic about this idea, viewing CPF as an approach that could be introduced in other towns and regions. One participant articulated the significance of context explicitly:

“You’d probably have to ask very specifically about each community... To make something like this work, you’ve got to have a sense of community; you’ve got to have a group of people that want to do the same things, and that love their community... you’ve got to have that drive and passion and energy.” (p16)

Clearly, there is a great opportunity to use learnings from CPF not only to guide the evolution of CPF itself, but also to develop similar foresight and visioning processes elsewhere, depending on context.

5.1. CPF Achievements

In the minds of participants, the CPF process has achieved tangible and intangible benefits for Clermont. These include practical, visible projects such as repainting town features and beautifying the main street, to the creation of new institutions that facilitate economic activity and diversity. The CPF process was also felt to have produced intangible benefits such as improved community cohesion and capacity for planning within the community. Participants outlined a number of factors that contributed to these successes, and which may be relevant to other communities considering similar processes. Chief among these in participants’ minds was the funding (by Rio Tinto in this case) of an Implementation Officer to oversee and drive CPF implementation. Although funded by the dominant mining interest locally, in some respects this arrangement places the community at the centre of the discussion about its future, as was the intention of the CPF process.

Other factors that appeared to be important to success included: CPF alignment with Council initiatives and interests (i.e., Isaac Regional Council’s 2020 Vision); a mining company prepared to support initiatives developed through an external decision-making process (i.e., the CPF committee); and a community mature in its identity and aspirations. It might also be suggested that such programs and processes are more likely to succeed in a period of growth for an industry such as mining, and in partnership with a company that has a relatively progressive understanding of community engagement and development.

Participants also felt that the process had to some degree helped to build a more resilient community less dependent on mining. Evidence for this was patchy and sometimes contradictory (e.g., many new businesses were servicing the mining industry), but perhaps through institutional capacity building and some development of human capital, Clermont’s resilience has been enhanced. Clermont’s agricultural heritage and historical understanding of the ebb and flow of mining investment support the comments that Clermont exists independent of mining and Cavaye’s [16] proposition that development and growth are not necessarily the same thing. With the export market for coal experiencing pressure and RTCA reportedly seeking to sell both Blair Athol and Clermont mines, this proposition is being tested.

Related to this, CPF explicitly sought to define a ‘preferred’ future, as opposed to probable, plausible, and/or possible futures. The motivation for this approach is understandable, in that it focuses effort towards achieving a positive shared vision. Indeed, one participant commented that the vision “brings the community together, puts the community on the same page” (P10). Yet focusing on an aspirational vision may encourage a ‘positive thinking’ mentality that blinds people to more likely yet less desired scenarios [14]. It may downplay the institutional barriers and ideological assumptions that circumscribe the conversations that are possible and that constrain what is realistically achievable. Managing expectations of CPF stakeholders and the broader community, particularly in the context of a mining downturn, will be important to the ongoing credibility of CPF.

5.2. Challenges for CPF

The Sarkissian et al. [17] model of dialogic engagement is a challenging aspiration in any context, and the CPF process has undoubtedly experienced these challenges. In its conception, CPF aimed to be genuinely and deeply participative, dialogic, to share power between actors and institutions, and to enable the achievement of an ambitious vision for a prosperous future. Inevitably, the aspiration and the reality for the CPF process diverge in some important respects, presenting challenges for the future of CPF and for other similar processes.

Participants identified various areas where the CPF process has fallen short of its full potential. These included communication of the CPF goals and achievements, the nature of the engagement process itself, the representativeness and governance arrangements for the CPF committee, and the schedule of activities flowing from the CPF plan. Examined together, these limitations largely speak to the relationships between the CPF process and the Clermont context. The idealised process may be labelled ‘engaged foresight’, but how stakeholders are engaged is a limitation for CPF. The CPF committee, as a specific example, strongly reflects a business constituency. Participants indicated that it was difficult to engage with and recruit committee members from outside a fairly narrow cohort of volunteers involved in a range of civic and local industry bodies and activities. This restricts diversity of opinion and the representativeness of CPF actors.

The unintended exclusivity of the process also works against the stated goal of CPF to encourage community ‘ownership’ of the process and, by extension, its preferred future. As prefaced by Miles et al. [1], achieving community ownership is a difficult proposition, particularly where genuine community engagement is not achieved and the process takes a top-down approach. There are several consequences of this for CPF. These include the separation of CPF from its community context. Participants closely involved in CPF expressed frustration at the difficulty of bringing new members in, while those less involved indicated ignorance of how to gain entry or even of who was involved. In this way, the CPF committee can be seen to be acting on behalf of the Clermont community without great connection with it.

If the CPF committee is not broadly representative of the Clermont community, the goal of community ownership cannot be achieved. The lack of diversity of opinion and representativeness of CPF actors inherently colours the interests that are reflected in its decisions and initiatives. It may be argued that the current CPF structure inadvertently reinforces existing power dynamics and networks of influence. The shape of Clermont’s future, then, may be shaped by a small group whose values and world views differ from many in the broader community.

With reference to the earlier discussion of engagement principles and frameworks, CPF aspired to a participatory, dialogic process. Our findings suggest that this aspiration, although well intentioned, has fallen short of being realised thus far. Participants indicated that the community had been consulted rather than engaged, in a manner that suggests this is not an ongoing process, and that general community members are less active in shaping their future than first envisaged.

CPF represents a case study of an attempt to practise ‘engaged foresight’. The CPF process aims to describe a preferred future and realise a plan for its achievement. It stands as an innovative and progressive process that has delivered real outcomes for the Clermont community and other CPF stakeholders. There remain challenges in realising the CPF vision, however, including the engagement of a broader representation of Clermont’s residents, robust governance mechanisms in recruiting and maintaining the CPF committee, and managing expectations of the pace and scale of outcomes from the process. CPF represents genuine intent to challenge traditional ways of community planning with a view to reducing economic dependence on mining. The extent to which resilience and independence are achieved is a question that will be answered in coming years as the fortunes of Clermont mine and other local industries ebb and flow.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Rio Tinto Coal Australia (RTCA) and supported with in-kind assistance by members of the Isaac Regional Council (IRC). Neither RTCA nor IRC, or their employees, had any editorial control over the content of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Miles, B.; Reark, J.; Kinnear, S.; Howkins, T.; Springer, T. Responding to the challenges of regional development: Clermont’s Preferred Future and community development strategy. In Proceedings of the 12th SEGRA (Sustainable Economic Growth for Regional Australia) Conference, Albury, Australia, 18–20 August 2008.

- Faint, S.; Hamblin, N. The future is rosy, but it hasn’t always been this way. Clermont’s Preferred Future: A model of engagement and community development. In Proceedings of the Social Licence & Stakeholder Engagement Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 6–8 August 2012.

- Isaac Regional Council. FIFO/DIDO Enquiry: Isaac Regional Council submission. 2011. Available online: http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House_of_Representatives_Committees?url=/ra/fifodido/subs.htm (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Isaac Regional Council. Your free town to town guide to travelling the Isaac Region: A short drive from Mackay and Rockhampton n.d. Available online: http://www.isaac.qld.gov.au/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=c0549ef3-f492-4b05-8645-f9d375be8ea6&groupId=12238 (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Rio Tinto. Blair Athol media release. 2013. Available online: http://www.riotinto.com/media/5157_22272.asp (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Rio Tinto Coal Australia. Clermont mine. 2012. Available online: http://www.riotintocoalaustralia.com.au/321_clermont_mine_project.asp (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Stanley, D. Rio Tinto to sell Clermont and Blair Athol coal mines. CQ News. 5 April 2013. Available online: http://www.cqnews.com.au/news/rio-tinto-to-ditch-two-mines-in-attempt-to-save-it/1817962/ (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Clermont Community and Business Group. Available online: http://www.ourclermont.com.au (accessed on 15 October 2013).

- Isaac Regional Council. Isaac Region 2020 Vision Community Plan. 2009. Available online: http://www.isaac.qld.gov.au/community-plan (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Slaughter, R. The state of play in the futures field: A metascanning overview. Foresight 2009, 11, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voros, J. A primer on futures studies, foresight and the use of scenarios. Prospect. 2001, 6. Available online: http://thinkingfutures.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/A_Primer_on_Futures_Studies.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Gidley, J.M. Futures/foresight in education at primary and secondary levels: A literature review and research task analysis. In Futures in Education: Principles, practice and potential; Australian Foresight Institute Monograph Series; Australian Foresight Institute: Hawthorn, Australia, 2004; pp. 5–72. [Google Scholar]

- Voros, J. Macro-prospection: Thinking about the future using macro- and Big History. In Proceedings of Global Future 2045 International Congress; Moscow, Russia: 17–20 February 2012.

- Ehrenreich, B. Smile or Die: How Positive Thinking Fooled America and the World; Granta: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter, R. Futures for the Third Millennium: Enabling the Forward View; Prospect: St Leonards, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cavaye, J. Understanding community development. Available online: http://www.communitydevelopment.com.au/Documents/Understanding%20Community%20Development.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2013).

- Sarkissian, W.; Hofer, N.; Shore, Y.; Vajda, S.; Wilkinson, C. Kitchen Table Sustainability: Practical recipes for Community Engagement with Sustainability; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Industry Tourism and Resources (DITR), Community Engagement and Development; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- Minerals Council of Australia (MCA). Enduring Value: The Australian Minerals Industry Framework for Sustainable Development. Guidance for Implementation. Available online: http://www.minerals.org.au/focus/sustainable_development/enduring_value (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Ministerial Council on Mineral and Petroleum Resources (MCMPR), Principles for Engagement with Communities and Stakeholders; MCMPR: Canberra, Australia, 2005.

- AccountAbility AA1000 stakeholder engagement standard 2011. Available online: http://www.accountability.org/images/content/5/4/542/AA1000SES%202010%20PRINT.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2). IAP2 core Values of Public Participation. Available online: http://iap2.affiniscape.com/associations/4748/files/CoreValues.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Victoria State Government Department of Environment and Primary Resources. Effective Engagement. Available online: http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/effective-engagement (accessed on 10 October 2013).