Chelator-Assisted Phytoextraction and Bioenergy Potential of Brassica napus L. and Zea mays L. on Metal-Contaminated Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Materials

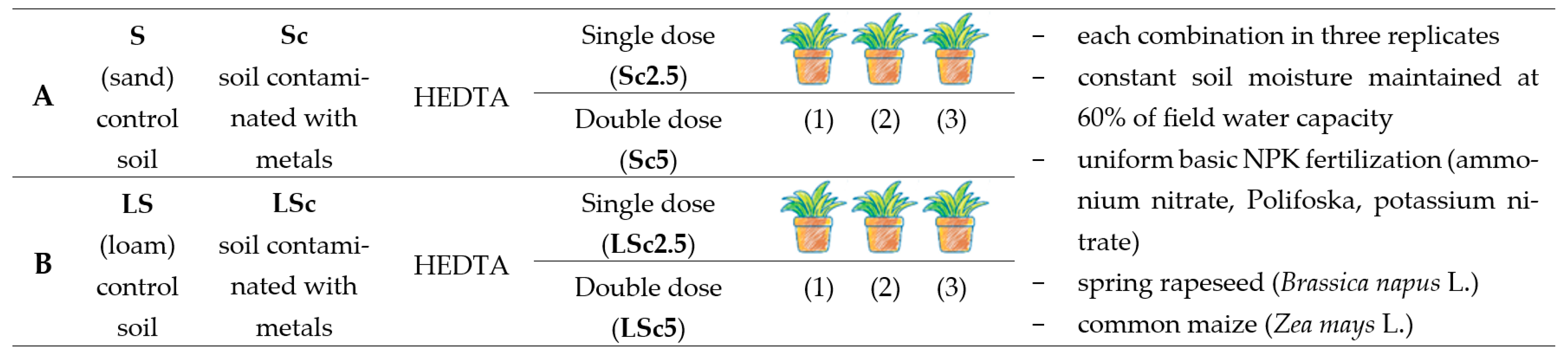

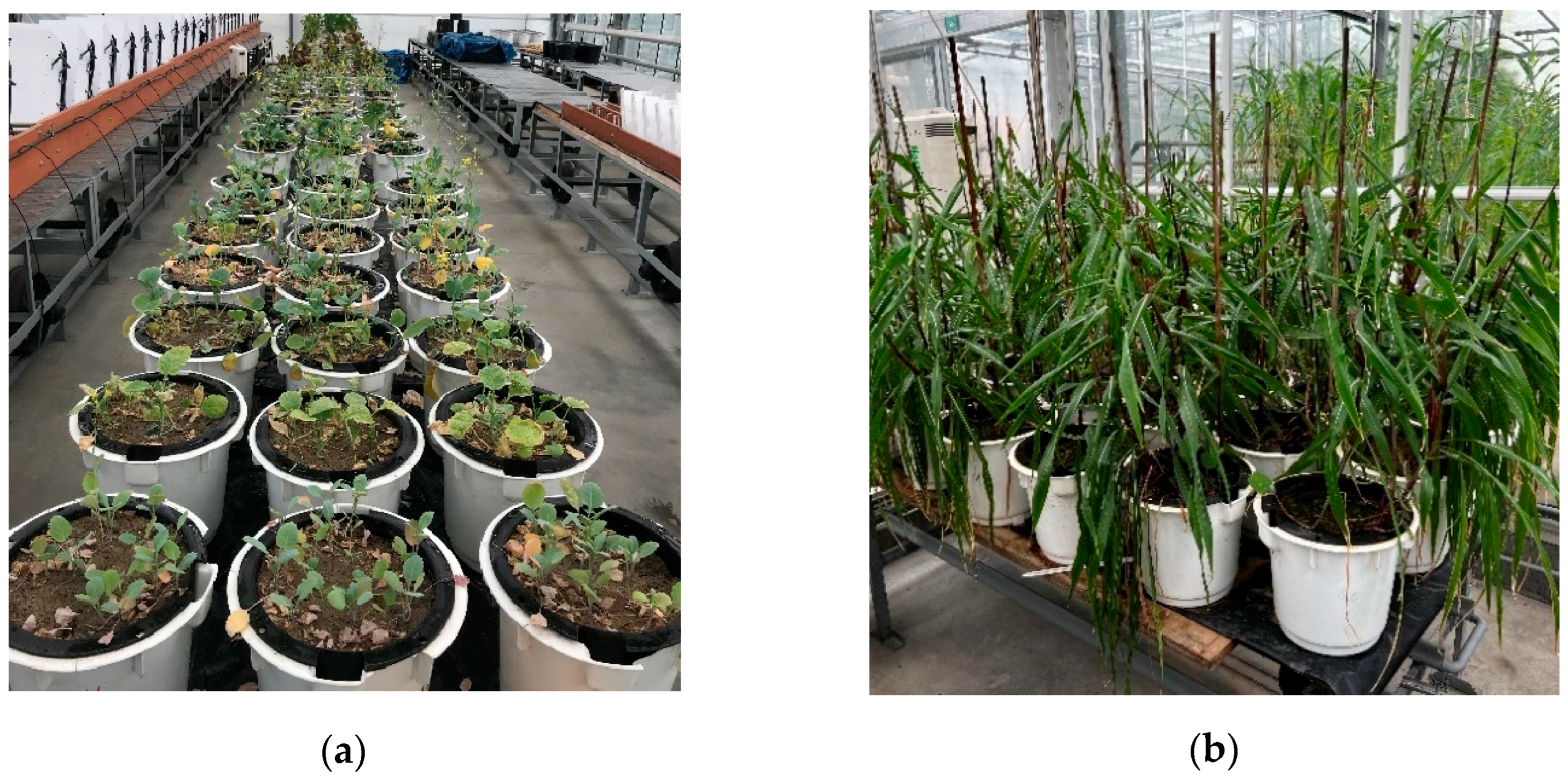

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Tested Plants

2.4. Laboratory Methods for Soil and Plant Material Analysis

2.5. Characteristics of Soils and the Chelating Agent HEDTA

- Residential land: Zn—500 mg·kg−1, Cd—2 mg·kg−1, Cu and Pb—200 mg·kg−1.

- Agricultural land: Zn—300 mg·kg−1, Cd—2 mg·kg−1, Cu and Pb—100 mg·kg−1 (light soils); Zn—1000 mg·kg−1, Cd—5 mg·kg−1, Cu—300 mg·kg−1, Pb—500 mg·kg−1 (heavy soils).

- Forest land: Zn—1000 mg·kg−1, Cd—10 mg·kg−1, Cu—300 mg·kg−1, Pb—500 mg·kg−1.

- Industrial land: Zn—2000 mg·kg−1, Cd—15 mg·kg−1, Cu and Pb—600 mg·kg−1.

2.6. Computational Methods and Statistical Analysis of Results

- −

- Class 0—no contamination (Igeo ≤ 0);

- −

- Class 1—slight to moderate contamination (0 < Igeo ≤ 1);

- −

- Class 2—moderate contamination (1 < Igeo ≤ 2);

- −

- Class 3—moderate to heavy contamination (2 < Igeo ≤ 3);

- −

- Class 4—heavy contamination (3 < Igeo ≤ 4);

- −

- Class 5—heavy to extreme contamination (4 < Igeo ≤ 5);

- −

- Class 6—extreme contamination (Igeo > 5).

- −

- Excluder plants bioconcentration factors (BCF_s < 1):

- −

- ≤0.01: no accumulation;

- −

- <0.01–0.1: low accumulation;

- −

- <0.1–1: moderate accumulation.

- −

- Accumulators (BCF_s = 1–10):

- −

- >1: high accumulation.

- −

- Hyperaccumulators (BCF_s > 10).

3. Results

3.1. Total Concentrations of Metals in Soil

3.2. Environmental Risk Indicators

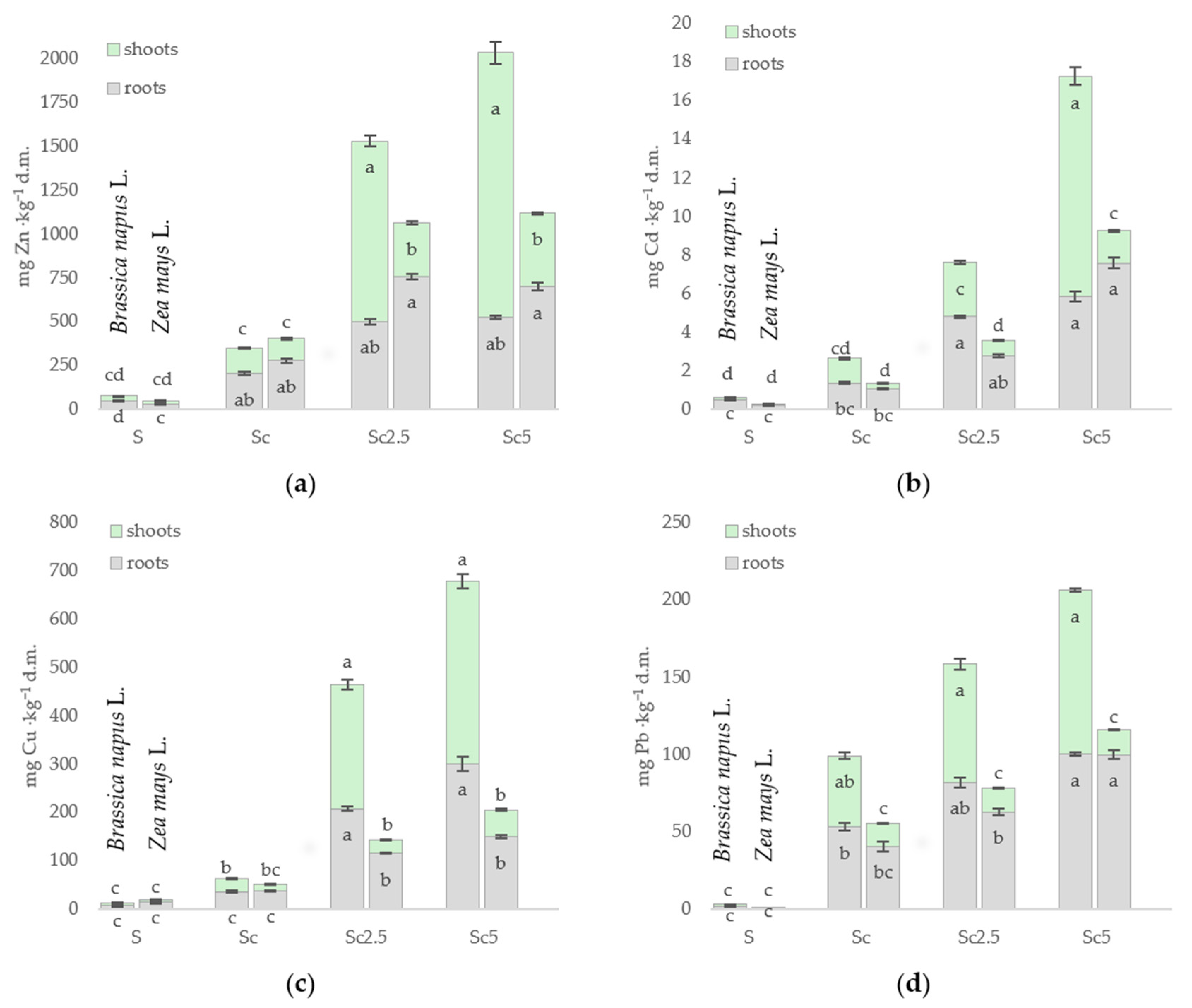

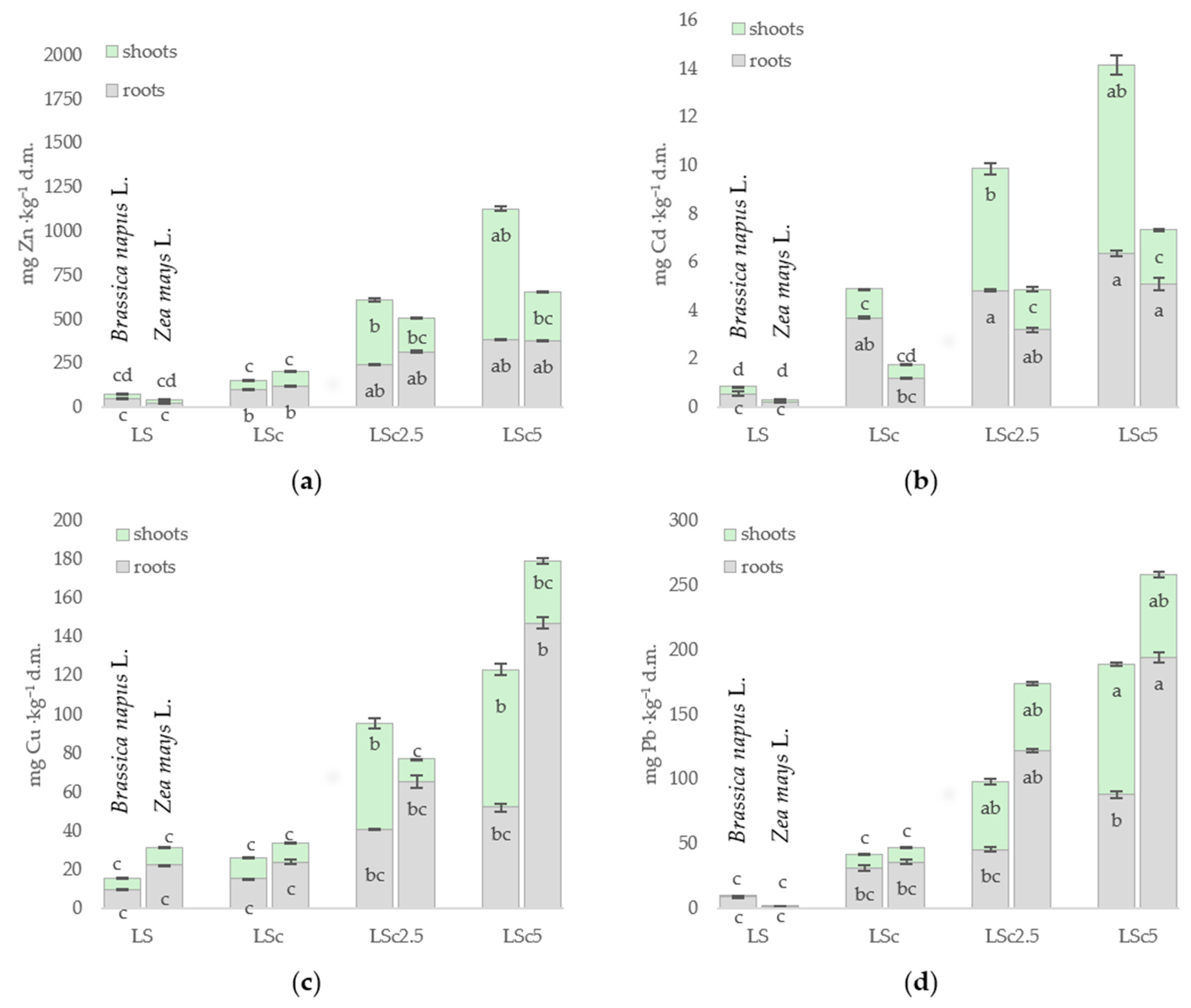

3.3. Metal Content in the Organs of Brassica napus L. and Zea mays L.

3.4. Bioconcentration and Translocation Factors

- −

- BCF_r = metal concentration in roots/metal concentration in soil.

- −

- BCF_s = metal concentration in shoots/metal concentration in soil.

- −

- TF = metal concentration in shoots/metal concentration in roots Equation (4).

3.5. Plant Yield

3.6. Management of Plant Biomass

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The application of HEDTA significantly increased metal mobility in the soil, leading to effective accumulation in plants and a reduction in Igeo, Cf, and RI indices. The effect was more pronounced with the double HEDTA dose.

- Rapeseed demonstrated a clearly higher phytoextraction potential than maize, particularly for Zn, Cd, and Cu, as confirmed by BCF_s > 1 and TF > 1 values. Maize acted as a phytostabilizing species, retaining metals in the roots.

- Rapeseed biomass exhibited a higher calorific value (up to 20.6 MJ·kg−1), making it a more efficient energy resource than maize, which—due to its lower ash content—may be preferred in fermentation processes.

- YI and MTI indices confirmed rapeseed’s high tolerance to metals, especially in loam soil with HEDTA addition. Maize showed a higher growth rate under control conditions, but its tolerance was lower than that of rapeseed.

- The utility of biomass varied depending on soil conditions and HEDTA application. Rapeseed and maize showed industrial applicability for Zn, Cd, and Pb, while Cu was suitable for feed use (maize, 2.5 mmol·kg−1 dose) or industrial use (5 mmol·kg−1 dose).

- The results confirm that assisted phytoextraction can be an effective method for remediating metal-contaminated soils while simultaneously providing biomass with high energy potential. Integrating these processes aligns with the goals of sustainable development and energy transition.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, J.K.; Kumar, N.; Singh, N.P.; Santal, A.R. Phytoremediation technologies and their mechanism for removal of heavy metal from contaminated soil: An approach for a sustainable environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1076876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusz, A.; Wiśniewska, M.; Rogalski, D. Assessment of the Accumulation Ability of Festuca rubra L. and Alyssum saxatile L. Tested on Soils Contaminated with Zn, Cd, Ni, Pb, Cr, and Cu. Resources 2021, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, N.; Hermans, C.; Schat, H. Molecular mechanisms of metal hyperaccumulation in plants. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawal, R.S.; Naseem, S.; Pandey, D.; Suman, S.K. Chapter 13—Microbe-assisted remediation of xenobiotics: A sustainable solution. In Microbiome-Based Decontamination of Environmental Pollutants; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 317–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Delavar, M.A. Modelling phytoremediation: Concepts, methods, challenges and perspectives. Soil Environ. Health 2024, 2, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaib, M.; Adnan, M. Phytoremediation: A comprehensive look at soil decontamination techniques. Int. J. Contemp. Issues Soc. Sci. 2024, 3, 998–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Santa-Cruz, J.; Robinson, B.; Krutyakov, Y.A.; Shapoval, O.A.; Peñaloza, P.; Yáñez, C.; Neaman, A. An assessment of the feasibility of phytoextraction for the stripping of bioavailable metals from contaminated soils. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eben, P.; Mohri, M.; Pauleit, S.; Duthweiler, S.; Helmreich, B. Phytoextraction potential of herbaceous plant species and the influence of environmental factors—A meta-analytical approach. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 199, 107169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. Re-yellowing of chromium-contaminated soil after reduction-based remediation: Effects and mechanisms of extreme natural conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaylock, M.J.; Salt, D.E.; Dushenkov, S.; Zakharova, O.; Gussman, C.; Kapulnik, Y.; Ensley, B.D.; Raskin, I. Enhanced accumulation of Pb in Indian mustard by soil-applied chelating agents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997, 31, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.L.; Shen, Z.G.; Li, X.D. Enhanced phytoextraction of Cu, Pb, Zn and Cd with EDTA and EDDS. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quartacci, M.F.; Irtelli, B.; Baker, A.J.M.; Navari-Izzo, F. The use of NTA and EDDS for enhanced phytoextraction of metals from a multiply contaminated soil by Brassica carinata. Chemosphere 2007, 68, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, H.I.; Ullah, I.; Toor, M.D.; Tanveer, N.A.; Din, M.M.U.; Basit, A.; Sultan, Y.; Muhammad, M.; Rehman, M.U. Heavy metals toxicity in plants: Understanding mechanisms and developing coping strategies for remediation. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, A.T.; Samani, Z.; Dwyer, B.; Jacquez, R. Heap leaching as a solvent-extraction technique for remediation of metals-contaminated soils. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 491, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A.P.; Singh, I. Washing of zinc(II) from contaminated soil column. J. Environ. Eng. 1995, 121, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.W. Chelant extraction of heavy metals from contaminated soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 1999, 66, 151–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducci, L.; Rizzo, P.; Pinardi, R.; Celico, F. An Interdisciplinary Assessment of the Impact of Emerging Contaminants on Groundwater from Wastewater Containing Disodium EDTA. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt, D.E.; Smith, R.D.; Raskin, I. Phytoremediation. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998, 49, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, Z.; Homaee, M.; Asadi, M.E.; Asadi Kapourchal, S. Cadmium removal from Cd-contaminated soils using some natural and synthetic chelates for enhancing phytoextraction. Chem. Ecol. 2017, 33, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werle, S.; Bisorca, D.; Katelbach-Woźniak, A.; Pogrzeba, M.; Krzyżak, J.; Ratman-Kłosińska, I.; Burnete, D. Phytoremediation as an effective method to remove heavy metals from contaminated area TG/FT-IR analysis results of the gasification of heavy metal contaminated energy crops. J. Energy Inst. 2017, 90, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachel-Jakubowska, M.; Kraszkiewicz, A.; Szpryngiel, M.; Niedziółka, I. Możliwości wykorzystania odpadów poprodukcyjnych z rzepaku ozimego na cele energetyczne. Inżynieria Rol. 2011, 6, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, W.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. Modification, application and reaction mechanisms of nano-sized iron sulfide particles for pollutant removal from soil and water: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 362, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzyńska, S.; Rudnicki, K.; Budka, A.; Niedzielski, P.; Mleczek, M. Dendroremediation of soil contaminated by mining sludge: A three-year study on the potential of Tilia cordata and Quercus robur in remediation of multi-element pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 944, 173941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Ent, A.; Baker, A.J.M.; Reeves, R.D.; Pollard, A.J.; Schat, H. Hyperaccumulators of metal and metalloid trace elements: Facts and fiction. Plant Soil 2013, 362, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Moreno, J.M.; Callejón-Ferre, A.J.; Pérez-Alonso, J.; Velázquez-Martí, B. A review of the mathematical models for predicting the heating value of biomass materials. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3065–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Shen, Z.; Lou, L.; Li, X. EDDS and EDTA-enhanced phytoextraction of metals from artificially contaminated soil and residual effects of chelant compounds. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 144, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghnaya, A.B.; Charles, G.; Hourmant, A.; Hamida, J.B.; Branchard, M. Physiological behaviour of four rapeseed cultivar (Brassica napus L.) submitted to metal stress. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2009, 332, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, U. Growth Stage of Mono- and Dicotyledonous Plants: BBCH Monograph; Julius Kühn-Institut: Quedlinburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosharafian, S.; Afzali, S.; Weaver, G.M.; van Iersel, M.; Velni, J.M. Optimal lighting control in greenhouse by incorporating sunlight prediction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 188, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusz, A.; Wiśniewska, M.; Kamiński, A.; Knosala, P.; Rogalski, D. Influence of Carbons on Metal Stabilization and the Reduction in Soil Phytotoxicity with the Assessment of Health Risks. Resources 2024, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-ISO 10390:2022-09; Soil Quality—Determination of pH. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- Ostrowska, A.; Gawliński, S.; Szczubiałka, Z. Metody Analizy i Oceny Właściwości Gleb i Roślin. Katalog; Instytut Ochrony Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- PN-ISO 14235: 2003P; Soil Quality–Determination of Organic Carbon Content by Oxidation with Dichromate (VI) in a Sulfuric Acid (VI) Environment. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- PN-EN ISO 9964-1:2001P; Water Quality—Determination of Sodium and Potassium by Flame Atomic Emission Spectrometry—Part 1: General Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Schwarz, A.; Wilcke, W.; Styk, J.; Zech, W. Heavy metal release from soils in Batch pH–stat experiments. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 1 September 2016 on the Method of Assessing the Pollution of the Earth’s Surface. J. Laws 2016, Item 1395, Modif. 2024, Item. 1657. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Merck Official Webiste. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Müller, G. Index of geo-accumulation in sediments of the Rhine River. GeoJournal 1969, 2, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The geochemical evolution of the continental crust. Rev. Geophys. 1995, 33, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Zong, Y.; Lu, S. Assessment of heavy metal pollution and human health risk in urban soils of steel industrial city (Anshan), Liaoning, Northeast China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 120, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.Q.; Komar, K.M.; Tu, C.; Zhang, W.; Cai, Y.; Kenelly, E.D. A Fern that hyper-accumulates arsenic. Nature 2001, 409, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sorogy, A.S.; Al-Kahtany, K.; Alharbi, T.; Al Hawas, R.; Rikan, N. Geographic Information System and Multivariate Analysis Approach for Mapping Soil Contamination and Environmental Risk Assessment in Arid Regions. Land 2025, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigisha Parikh, S.A.; Channiwala, G.K.; Ghosal, A. correlation for calculating HHV from proximate analysis of solid fuels. Fuel 2005, 84, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, B.; Liu, X.; Xiao, H.; Liu, S.; Shao, H. Systematic evaluation of plant metals/metalloids accumulation efficiency: A global synthesis of bioaccumulation and translocation factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1602951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, M. The ANOVA method as a popular research tool. Stud. Pr. WNEiZ 2019, 55, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatSoft. Elektroniczny Podręcznik Statystyki PL, Krakow. 2006. Available online: http://www.statsoft.pl/textbook/stathome.html (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Agbangba, C.E.; Aide, E.S.; Honfo, H.; Kakai, R.G. On the use of post-hoc tests in environmental and biological sciences: A critical review. Heliyon 2024, 10, 25131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Deng, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, F.; He, Y.; He, L.; Li, Y. Contamination and health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil and ditch sediments in long-term mine wastes area. Toxics 2022, 10, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapuerta, M.; Armas, O.; Hernández, J.J.; Tsolakis, A. Potential for Reducing Emissions in a Diesel Engine by Fuelling with Conventional Biodiesel and Fischer–Tropsch Diesel. Fuel 2010, 89, 3106–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenčík, J.; Hönig, V.; Obergruber, M.; Hájek, J.; Vráblík, A.; Černý, R.; Schlehöfer, D.; He-rink, T. Advanced Biofuels Based on Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis for Applications in Diesel Engines. Materials 2021, 14, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zentková, I.; Cvengrošová, E. The Utilization of Rapeseed for Biofuels Production in the EU. Visegr. J. Bio. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 2, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firrisa, M.T.; Van Duren, I.; Voinov, A. Energy efficiency for rapeseed bio-diesel production in different farming systems. Energy Effic. 2014, 7, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyllis2: Database for Biomass and Waste. Available online: https://phyllis.nl/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Karczewska, A.; Spiak, Z.; Kabała, C.; Gałka, B.; Szopka, K.; Jezierski, P.; Kocan, P. Ocena Możliwości Zastosowania Metody Wspomaganej Fitoekstrakcji Rekultywacji Gleb Zanieczyszczonych Emisjami Hutnictwa Miedzi; Wydawnictwo Zante: Wrocław, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kalousek, P.; Holátko, J.; Schreiber, P.; Pluháček, T.; Širůčková Lónová, K.; Radziemska, M.; Tarkowski, P.; Vyhnánek, T.; Hammerschmiedt, T.; Brtnický, M. The Effect of Chelating Agents on the Zn-Phytoextraction Potential of Hemp and Soil Microbial Activity. Chem. Bio-Log. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, K.; Kayser, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Furrer, G.; Schulin, R. Comparison of NTA and elemental sulfur as potential soil amendments in phytoremediation. Soil Sediment Contam. 2002, 11, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Song, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M.; Duan, T.; Cai, Y. Coupling soil washing with chelator and cathodic reduction treatment for a multi-metal contaminated soil: Effect of pH controlling. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 448, 142178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoosefat, O.; Shariatinia, Z.; Mair, F.S.; Paghaleh, A.S. An effective strategy to synthesize water-soluble iron heterocomplexes containing Dubb humic acid chelating agent as efficient micronutrients for iron-deficient soils of high pH levels. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 376, 121441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicinska, A.; Pomykała, R. Changes in Soil pH and Mobility of Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 72, e13203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacheva, A.; Ilieva, R.; Rabadjieva, D.; Vladov, I.; Nanev, V. Chemical Equilibrium Models for Calculation of Metal Chemical Species in Surface Waters as a Tool for Evaluation of Their Bioavailability. J. Solut. Chem. 2025, 54, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Ji, J.; Yuan, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, C. Accumulation and translocation of heavy metals in the canola (Brassica napus L.)—Soil system in Yangtze River Delta, China. Plant Soil 2011, 353, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, M.; Cozma, P.; Minut, M.; Hlihor, R.-M.; Bețianu, C.; Diaconu, M.; Gavrilescu, M. New Evidence of Model Crop Brassica napus L. in Soil Clean-Up: Comparison of Tolerance and Accumulation of Lead and Cadmium. Plants 2021, 10, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.Y.; Azhar, N.; Ashraf, M.; Hussain, M.; Arshad, M. Influence of lead on growth and nutrient accumulation in canola (Brassica napus L.) cultivars. J. Environ. Biol. 2011, 32, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zou, J.; Duan, X.; Jiang, W.; Liu, D. Cadmium accumulation and its effects on metal uptake in maize (Zea mays L.). Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Cai, X.; Wen, J.; Xu, J. Heavy metals accumulation and risk assessment in a soil-maize (Zea mays L.) system around a zinc-smelting area in southwest China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 4875–4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandy, S.; Schulin, R.; Nowack, B. The influence of EDDS on the uptake of heavy metals in hydroponically grown sunflowers. Chemosphere 2006, 62, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xi, M.; Jiang, G.; Liu, X.; Bai, Z.; Huang, Y. Effects of IDSA, EDDS and EDTA on heavy metals accumulation in hydroponically grown maize (Zea mays, L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 181, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, M.; Tlustoš, P.; Száková, J.; Chrastný, V. The use of poplar during a two-year induced phytoextraction of metals from contaminated agricultural soils. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 151, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kos, B.; Grčman, H.; Leštan, D. Phytoextraction of lead, zinc and cadmium from soil by selected plants. Plant Soil Environ. 2003, 49, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelou, M.W.H.; Ebel, M.; Schaeffer, A. Chelate assisted phytoextraction of heavy metals from soil. Effect, mechanism, toxicity, and fate of chelating agents. Chemosphere 2007, 68, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Kunhikrishnan, A.; Thangarajan, R.; Kumpiene, J.; Park, J.; Makino, T.; Kirkham, M.B.; Scheckel, K. Remediation of heavy met-al(loid)s contaminated soils—To mobilize or to immobilize? J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 266, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihucz, V.G.; Csog, Á.; Fodor, F.; Tatár, E.; Szoboszlai, N.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, L.; Záray, G. Impact of two iron (III) chelators on the iron, cadmium, lead and nickel accumulation in poplar grown under heavy metal stress in hydroponics. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, A.; Dhunna, G.; Chawla, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Thurkal, A.K. A tabulated review on distribution of heavy metals in various plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 2210–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, P.; Yusoff, M.M.; Maniam, G.P.; Govindan, N. Biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant derivatives and their new avenues in pharmacological applications—An updated report. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Thokozani, K.; Wang, Y.S.; Sun, M. Washing reagents for remediating heavy-metal-contaminated soil: A Review. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 901570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbaş, A. Biomass resource facilities and biomass conversion processing for fuels and chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2001, 42, 1357–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, A.; Schwitzguebel, J.-P.; Thewys, T.; Van der Lelie, D.; Vangronsveld, J. The use of plants for remediation of metal-contaminated soils. Sci. World J. 2004, 4, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, M.; Neczaj, E.; Fijałkowski, K.; Grobelak, A.; Grosser, A.; Worwag, M.; Rorat, A.; Brattebo, H.; Almås, Å.; Singh, B.R. Sewage Sludge Disposal Strategies for Sustainable Development. Environ. Res. 2017, 156, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, K.; Derkacz, D.; Krasowska, A.; Białowiec, A. Isolation and identification of carbon monoxide producing microorganisms from compost. Waste Manag. 2024, 182, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maj, I.; Niesporek, K.; Płaza, P.; Maier, J.; Łój, P. Biomass Ash: A Review of Chemical Compositions and Management Trends. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, S.; Singhal, A.; Rallapalli, S.; Mishra, A. Bio-chelate Assisted Leaching for Enhanced Heavy Metal Remediation in Municipal Solid Waste Compost. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 65280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhou, C.; Xu, S.; Huang, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, G.; Wu, L.; Dou, C. Study on the Solidification Performance and Mechanism of Heavy Metals by Sludge/Biomass Ash Ceramsites, Biochar and Biomass Ash. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, W.; Li, Z.; Shi, H.; Gao, J.; Jin, B. Stabilization Effect of Heavy Metals in Waste Incineration Fly Ash by Inorganic and Organic Chelating Agents. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broda, M.; Yelle, D.J.; Serwańska, K. Bioethanol Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass—Challenges and Solutions. Molecules 2022, 27, 8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beluhan, S.; Mihajlovski, K.; Šantek, B.; Ivancić Šantek, M. The Production of Bioethanol from Lignocellulosic Biomass: Pretreatment Methods, Fermentation, and Downstream Processing. Energies 2023, 16, 7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hammadi, M.; Anadol, G.; Martín-García, F.J.; Moreno-García, J.; Keskin Gündoğdu, T.; Güngörmüşler, M. Scaling Bioethanol for the Future: The Commercialization Potential of Extremophiles and Non-Conventional Microorganisms. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1565273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.A.; Majeed, H.H.; Abid, R.A.; Alsultan, G.A.; Mijan, N.A.; Lee, H.V.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H. Ethanol Production from Lignocellulosic Waste Materials: Kinetics and Optimization Studies. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, Y.A.; Kumari, S.; Jain, S.K.; Garg, M.C. A Review on Waste Biomass-to-Energy: Integrated Thermochemical and Biochemical Conversion for Resource Recovery. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.J.; Walker, L. Thermochemical Conversion of Biomass: Potential Future Prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Huang, X.; Li, M.; Lu, Z.; Ling, X. Advances in Soil Amendments for Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils: Mechanisms, Impact, and Future Prospects. Toxics 2024, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Sung, K. Leaching Potential of Multi-Metal-Contaminated Soil in Chelate-Aided Remediation. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zheng, G.; Yang, J.; Chen, T.; Meng, X.; Xia, T. Safe Utilization of Cadmium- and Lead-Contaminated Farmland by Cultivating a Winter Rapeseed/Maize Rotation Compared with Two Phytoextraction Approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 304, 114306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Yang, J.; Zheng, G.; Guo, J.; Ma, C. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Efficient and Safe Utilization of Two Varieties of Winter Rapeseed Grown on Cadmium- and Lead-Contaminated Farmland Under Atmospheric Deposition. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil | TOC | pH KCl | Hh | Ca | Mg | K | Na | CEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | cmol(+)·kg−1 | |||||||

| S | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 8.24 | n.d. | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 0.65 ± 0.14 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 3.6 |

| LS | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 5.72 | 1.8 | 8.6 ± 1.0 | 0.82 ± 0.11 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 9.7 |

| Sc | 3.05 ± 0.11 | 8.77 | n.d. | 19.7 ± 3.0 | 4.54 ± 0.50 | 0.37 ± 0.09 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 25.4 |

| LSc | 3.49 ± 0.15 | 7.10 | 0.8 | 24.3 ± 2.4 | 5.12 ± 0.82 | 0.65 ± 0.13 | 0.84 ± 0.15 | 30.9 |

| Soil | Zn | Cd | Cu | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg·kg−1 | ||||

| S | 61.4 ± 1.5 | <det. | 19.1 ± 0.9 | 14.2 ± 0.7 |

| LS | 67.3 ± 1.7 | 0.61 ± 0.08 | 30.8 ± 1.5 | 20.8 ± 1.0 |

| Sc | 1152 ± 28 | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 189 ± 9 | 798 ± 39 |

| LSc | 893 ± 22 | 8.2 ± 0.7 | 220 ± 11 | 817 ± 41 |

| Plant/Soil | Zn | Igeo | Cd | Igeo | Cu | Igeo | Pb | Igeo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Brassica naspus L. | S | 56.2 | ±1.4d | −0.9 | 0.80 | ±0.07d | 2.5 | 18.3 | ±0.9d | −1.0 | 5.06 | ±0.25d | −2.6 |

| Sc | 1107 | ±27a | 3.4 | 8.62 | ±0.78a | 5.9 | 121 | ±6a | 1.7 | 752 | ±38a | 4.7 | ||

| Sc2.5 | 734 | ±18b | 2.8 | 5.35 | ±0.49b | 5.2 | 93.1 | ±4.7b | 1.3 | 754 | ±38a | 4.7 | ||

| Sc5 | 611 | ±15c | 2.5 | 4.63 | ±0.43c | 5.0 | 52.6 | ±2.6c | 0.5 | 599 | ±30b | 4.3 | ||

| B | LS | 59.1 | ±1.5d | −0.8 | 0.65 | ±0.06d | 2.1 | 28.7 | ±1.4c | −0.4 | 16.8 | ±0.8d | −0.8 | |

| LSc | 822 | ±21a | 2.9 | 7.08 | ±0.65a | 5.6 | 198 | ±10a | 2.4 | 802 | ±40a | 4.7 | ||

| LSc2.5 | 526 | ±13c | 2.3 | 7.56 | ±0.68a | 5.7 | 164 | ±8a | 2.1 | 747 | ±37b | 4.6 | ||

| LSc5 | 414 | ±10c | 2.0 | 5.87 | ±0.53c | 5.3 | 121 | ±6b | 1.7 | 614 | ±31bc | 4.4 | ||

| A | Zea mays L. | S | 48.7 | ±1.2d | −1.1 | 0.78 | ±0.07d | 2.4 | 15.6 | ±0.8d | −1.3 | 3.25 | ±0.16c | −3.2 |

| Sc | 1023 | ±25a | 3.3 | 8.09 | ±0.74a | 5.8 | 101 | ±5a | 1.4 | 703 | ±35a | 4.6 | ||

| Sc2.5 | 497 | ±12c | 2.2 | 4.34 | ±0.40bc | 4.9 | 67.6 | ±3.4b | 0.9 | 739 | ±37a | 4.6 | ||

| Sc5 | 472 | ±12c | 2.1 | 3.71 | ±0.34c | 4.7 | 36.2 | ±1.8c | −0.1 | 556 | ±28b | 4.2 | ||

| B | LS | 55.8 | ±1.4d | −0.9 | 0.61 | ±0.05c | 2.1 | 24.1 | ±1.2b | −0.6 | 11.7 | ±0.6d | −1.4 | |

| LSc | 753 | ±19a | 2.8 | 6.47 | ±0.59a | 5.5 | 162 | ±8a | 2.1 | 760 | ±38a | 4.7 | ||

| LSc2.5 | 415 | ±10bc | 2.0 | 6.63 | ±0.61a | 5.5 | 130 | ±7a | 1.8 | 664 | ±33a | 4.5 | ||

| LSc5 | 295 | ±7c | 1.5 | 4.38 | ±0.39b | 4.9 | 74.5 | ±3.7b | 1.0 | 532 | ±27b | 4.2 | ||

| Plant/Soil | Zn | Cd | Cu | Pb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cf | RI | Cf | RI | Cf | RI | Cf | RI | ||||||

| A | Brassica naspus L. | S | 0.3 | 56 | 0.8 | 24 | 0.4 | 92 | 0.1 | 25 | |||

| Sc | 6.3 | 1107 | 8.6 | 259 | 2.4 | 605 | 10.7 | 3760 | |||||

| Sc2.5 | 4.2 | 734 | 5.4 | 161 | 1.9 | 466 | 10.8 | 3770 | |||||

| Sc5 | 3.5 | 611 | 4.6 | 139 | 1.1 | 263 | 8.6 | 2995 | |||||

| B | LS | 0.3 | 59 | 0.7 | 20 | 0.6 | 144 | 0.2 | 84 | ||||

| LSc | 4.7 | 822 | 7.1 | 212 | 4.0 | 990 | 11.5 | 4010 | |||||

| LSc2.5 | 3.0 | 526 | 7.6 | 227 | 3.3 | 820 | 10.7 | 3735 | |||||

| LSc5 | 2.4 | 414 | 5.9 | 176 | 2.4 | 605 | 8.8 | 3070 | |||||

| A | Zea mays L. | S | 0.3 | 49 | 0.8 | 24 | 0.3 | 78 | 0.0 | 16 | |||

| Sc | 5.8 | 1023 | 8.1 | 243 | 2.0 | 500 | 10.0 | 3515 | |||||

| Sc2.5 | 2.8 | 497 | 4.3 | 130 | 1.4 | 338 | 10.6 | 3695 | |||||

| Sc5 | 2.7 | 472 | 3.7 | 111 | 0.7 | 181 | 7.9 | 2780 | |||||

| B | LS | 0.3 | 56 | 0.6 | 18 | 0.5 | 121 | 0.2 | 59 | ||||

| LSc | 4.3 | 753 | 6.5 | 194 | 3.2 | 810 | 10.9 | 3800 | |||||

| LSc2.5 | 2.4 | 415 | 6.6 | 199 | 2.6 | 650 | 9.5 | 3320 | |||||

| LSc5 | 1.7 | 295 | 4.4 | 131 | 1.5 | 373 | 7.6 | 2660 | |||||

| Cf | Cf ≤ 1 low contamination | 1 < Cf ≤ 3 moderate contamination | 3 < Cf ≤ 6 significant contamination | Cf > 6 very significant contamination | |||||||||

| RI | RI < 150, low risk | 150 ≤ RI < 300 moderate risk | 300 ≤ RI < 600 significant risk | 600 ≤ RI high risk | |||||||||

| Plant/Soil | Zn | Cd | Cu | Pb | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCF_s | BCF_r | TF | BCF_s | BCF_r | TF | BCF_s | BCF_r | TF | BCF_s | BCF_r | TF | ||||||

| A | Brassica naspus L. | S | 0.52 | 0.88 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.79 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.34 | |||

| Sc | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.92 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.75 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.86 | |||||

| Sc2.5 | 1.40 | 0.68 | 2.05 | 0.52 | 0.90 | 0.58 | 2.75 | 2.24 | 1.23 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.93 | |||||

| Sc5 | 2.47 | 0.86 | 2.87 | 2.46 | 1.27 | 1.95 | 7.19 | 5.72 | 1.26 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.06 | |||||

| B | LS | 0.46 | 0.81 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.11 | ||||

| LSc | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.52 | 0.17 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.72 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.35 | |||||

| LSc2.5 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 1.53 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 1.05 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 1.34 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.15 | |||||

| LSc5 | 1.80 | 0.92 | 1.95 | 1.33 | 1.08 | 1.23 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 1.36 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 1.14 | |||||

| A | Zea mays L. | S | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.95 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.42 | |||

| Sc | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.36 | |||||

| Sc2.5 | 0.62 | 1.53 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.42 | 1.72 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.25 | |||||

| Sc5 | 0.89 | 1.48 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 2.05 | 0.22 | 1.53 | 4.15 | 0.37 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.16 | |||||

| B | LS | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.77 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.93 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.28 | ||||

| LSc | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.32 | |||||

| LSc2.5 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.42 | |||||

| LSc5 | 0.95 | 1.28 | 0.74 | 0.51 | 1.16 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 1.97 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.33 | |||||

| TF | ≤1—no translocation to shoots | >1—translocation to shoots | |||||||||||||||

| BCF | ≤0.01—no accumulation | <0.01–0.1—weak level of accumulation | <0.1–1—medium level of accumulation | >1—high level of accumulation | |||||||||||||

| Plant/Soil | Shoot Fresh Mass Yield | Fresh Root Mass Yield | Shoot Dry Mass Yield | Dry Root Mass Yield | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g Per Pot | kg·ha−1 | g Per Pot | kg·ha−1 | g Per Pot | kg·ha−1 | g Per Pot | kg·ha−1 | |||

| A | Brassica naspus L. | S | 11.5 ± 0.4c | 3032 | 2.24 ± 0.1c | 597 | 10.6 ± 0.1c | 2786 | 2.08 ± 0.1c | 547 |

| Sc | 9.7 ± 0.4c | 2550 | 9.28 ± 0.3a | 2433 | 8.9 ± 0.3c | 2344 | 8.48 ± 0.2a | 2232 | ||

| Sc2.5 | 10.3 ± 0.2c | 2726 | 9.76 ± 0.5a | 2563 | 9.5 ± 0.4c | 2506 | 8.96 ± 0.4a | 2351 | ||

| Sc5 | 3.0 ± 0.1d | 779 | 2.08 ± 0.1c | 551 | 2.7 ± 0.1d | 716 | 1.92 ± 0.1c | 506 | ||

| B | LS | 4.7 ± 0.2d | 1216 | 3.64 ± 0.2b | 945 | 4.3 ± 0.2d | 1118 | 3.25 ± 0.1b | 867 | |

| LSc | 3.7 ± 0.1d | 969 | 3.50 ± 0.2b | 918 | 3.4 ± 0.1d | 891 | 3.20 ± 0.1b | 842 | ||

| LSc2.5 | 20.9 ± 0.3b | 5503 | 4.68 ± 0.2b | 1229 | 19.2 ± 0.6b | 5058 | 4.28 ± 0.1b | 1127 | ||

| LSc5 | 26.7 ± 0.7b | 7016 | 4.95 ± 0.2b | 1305 | 24.5 ± 0.6b | 6449 | 4.55 ± 0.1b | 1198 | ||

| A | Zea mays L. | S | 39.2 ± 1.9a | 10,316 | 1.37 ± 0.1c | 361 | 36.0 ± 0.9a | 9482 | 1.26 ± 0.1c | 331 |

| Sc | 23.5 ± 0.8b | 6181 | 1.04 ± 0.1c | 276 | 21.6 ± 0.5b | 5681 | 0.96 ± 0.1c | 253 | ||

| Sc2.5 | 22.5 ± 0.7b | 5909 | 1.55 ± 0.1c | 407 | 20.7 ± 0.9b | 5431 | 1.41 ± 0.1c | 373 | ||

| Sc5 | 19.8 ± 0.9b | 5206 | 1.59 ± 0.1c | 421 | 18.2 ± 0.8b | 4785 | 1.48 ± 0.1c | 386 | ||

| B | LS | 48.3 ± 0.9a | 12,703 | 1.68 ± 0.1c | 442 | 44.2 ± 0.5a | 11,676 | 1.54 ± 0.1c | 405 | |

| LSc | 37.6 ±1.4a | 9894 | 1.04 ± 0.1c | 273 | 34.4 ± 0.4a | 9094 | 0.95 ± 0.1c | 251 | ||

| LSc2.5 | 59.0 ±1.2a | 15,520 | 1.93 ± 0.1c | 512 | 54.3 ± 2.6a | 14,265 | 1.79 ± 0.1c | 469 | ||

| LSc5 | 62.9± 2.7a | 16,568 | 1.09 ± 0.1c | 284 | 58.0 ± 2.4a | 15,228 | 0.98 ± 0.1c | 260 | ||

| Plant | C % | H % | O % | N % | S % | Ash % | HHV MJ·kg−1 | HHV * MJ·kg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brassica napus L. | 48.9 | 6.1 | 34.0 | 2.7 | 0.53 | 7.3 | 20.6 | 21.0–25.2 |

| Zea mays L. | 45.7 | 5.7 | 41.5 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 6.0 | 18.2 | 15.3–18.8 |

| Plant/Soil | CGR | MTIZn | MTICd | MTICu | MTIPb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Brassica naspus L. | S | 0.7 | - | - | - | - |

| Sc | 0.7 | 671 | 915 | 257 | 1140 | ||

| Sc2.5 | 0.5 | 287 | 367 | 128 | 738 | ||

| Sc5 | 0.2 | 82 | 109 | 25 | 201 | ||

| B | LS | 0.2 | - | - | - | - | |

| LSc | 0.8 | 2133 | 3215 | 1798 | 5202 | ||

| LSc2.5 | 2.7 | 4583 | 11,526 | 5001 | 16,270 | ||

| LSc5 | 3.1 | 4180 | 10,371 | 4276 | 15,498 | ||

| A | Zea mays L. | S | 3.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Sc | 1.9 | 353 | 489 | 121 | 607 | ||

| Sc2.5 | 1.7 | 158 | 242 | 75 | 588 | ||

| Sc5 | 1.4 | 125 | 173 | 34 | 369 | ||

| B | LS | 6.4 | - | - | - | - | |

| LSc | 6.1 | 409 | 616 | 308 | 1033 | ||

| LSc2.5 | 3.6 | 135 | 376 | 148 | 539 | ||

| LSc5 | 4.4 | 116 | 301 | 103 | 523 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pusz, A.; Rogalski, D.; Kamiński, A.; Knosala, P.; Wiśniewska, M. Chelator-Assisted Phytoextraction and Bioenergy Potential of Brassica napus L. and Zea mays L. on Metal-Contaminated Soils. Resources 2026, 15, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15010010

Pusz A, Rogalski D, Kamiński A, Knosala P, Wiśniewska M. Chelator-Assisted Phytoextraction and Bioenergy Potential of Brassica napus L. and Zea mays L. on Metal-Contaminated Soils. Resources. 2026; 15(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15010010

Chicago/Turabian StylePusz, Agnieszka, Dominik Rogalski, Arkadiusz Kamiński, Peter Knosala, and Magdalena Wiśniewska. 2026. "Chelator-Assisted Phytoextraction and Bioenergy Potential of Brassica napus L. and Zea mays L. on Metal-Contaminated Soils" Resources 15, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15010010

APA StylePusz, A., Rogalski, D., Kamiński, A., Knosala, P., & Wiśniewska, M. (2026). Chelator-Assisted Phytoextraction and Bioenergy Potential of Brassica napus L. and Zea mays L. on Metal-Contaminated Soils. Resources, 15(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15010010