Low-Carbon Green Hydrogen Strategies for Sustainable Development in Senegal: A Wind Energy Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

| References | Techno-Economic Analysis | LCOE | Carbon Footprint | Carbon Credit | Electrolyzer Technologies Comparisons | Sensitivity Analysis | H2 | LCOH | Payback Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Touilli et al. (2020) [55] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| Mostafa Rezaei et al. (2020) [51] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Almutairi et al. (2021) [52] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Delpierre et al. (2021) [56] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Ali Javaid et al. (2022) [57] | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Nasser et al. (2022) [58] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Ibrahim et al. (2023) [22] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Ashish Sedai1 et al. (2023) [59] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Henry et al. (2023) [60] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Koholé et al. (2023) [39] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Cheng & Hughes (2023) [61] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Rezaei et al. (2024) [62] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Chunyan Song et al. (2024) [63] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Javanshir et al. (2024) [64] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Maaloum et al. (2024) [65] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Albalawi et al. (2025) [29] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Bagheri et al. (2025) [66] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Perdana et al. (2025) [67] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| Boutaghane et al. (2025) [27] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Albalawi et al. (2025) [29] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Jiang et al. (2025) [30] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Munther et al. (2025) [31] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Zhang et al. (2025) [32] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| This study | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

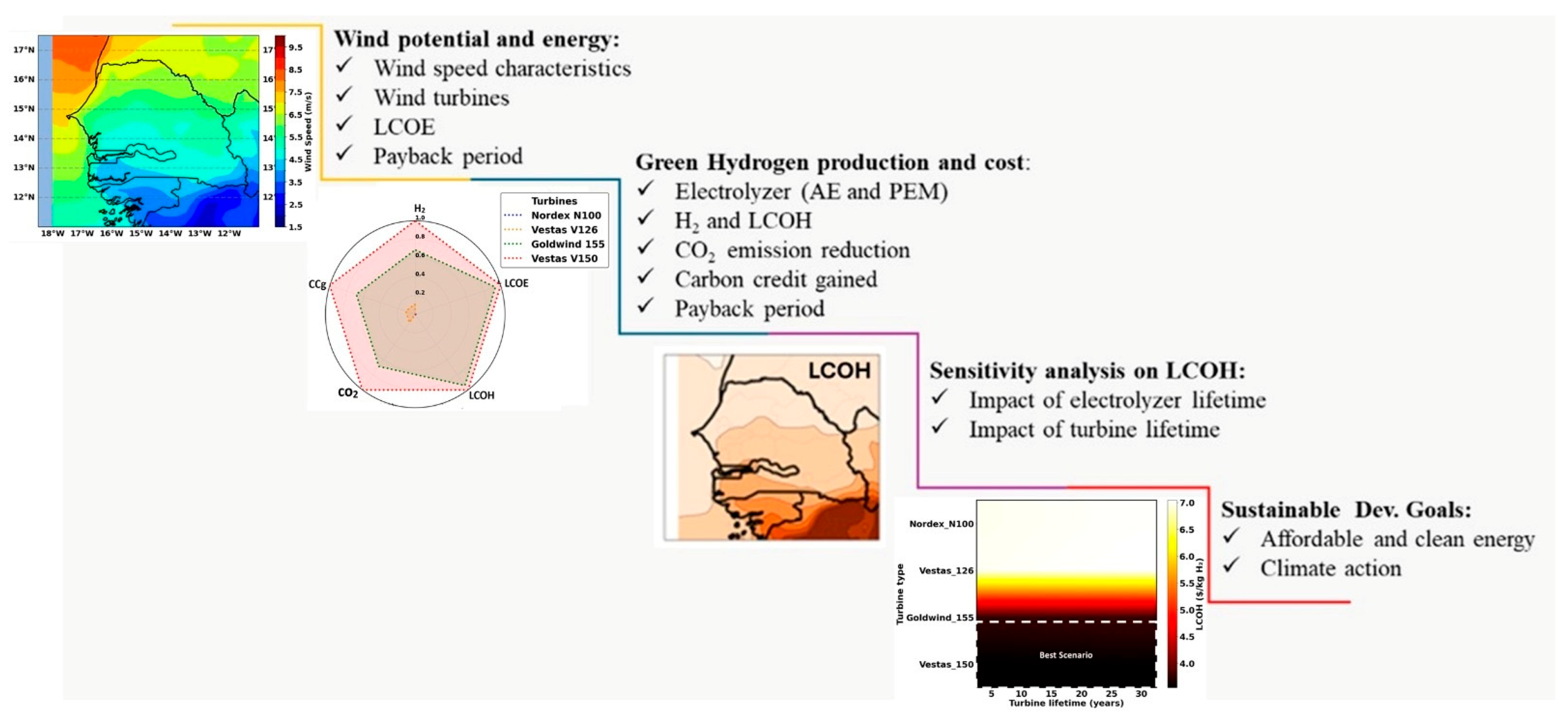

3. Data, Materials Descriptions and Mathematical Background

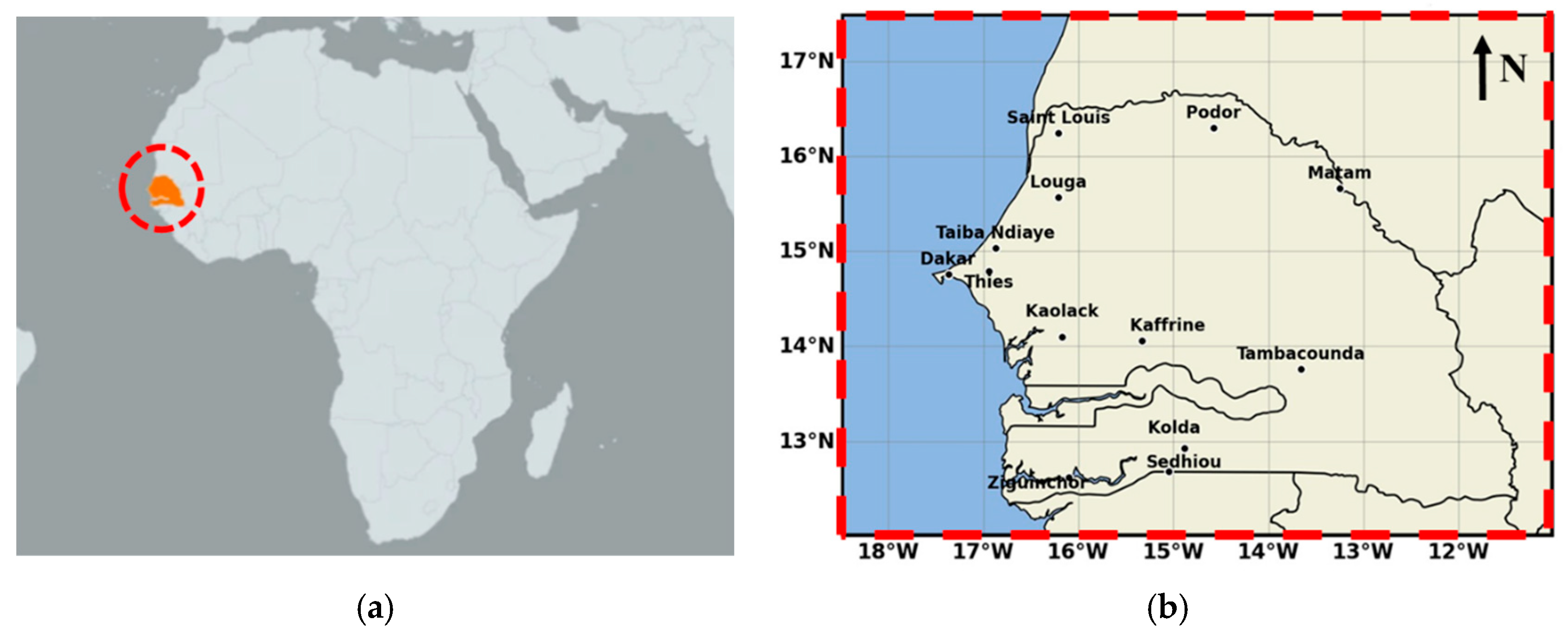

3.1. Site Description

3.2. Wind Data Collection

3.3. Selection of Turbines and Electrolyzers

3.4. Characteristics of Electrolyzer Technologies

3.5. Mathematical Background

4. Results and Discussions

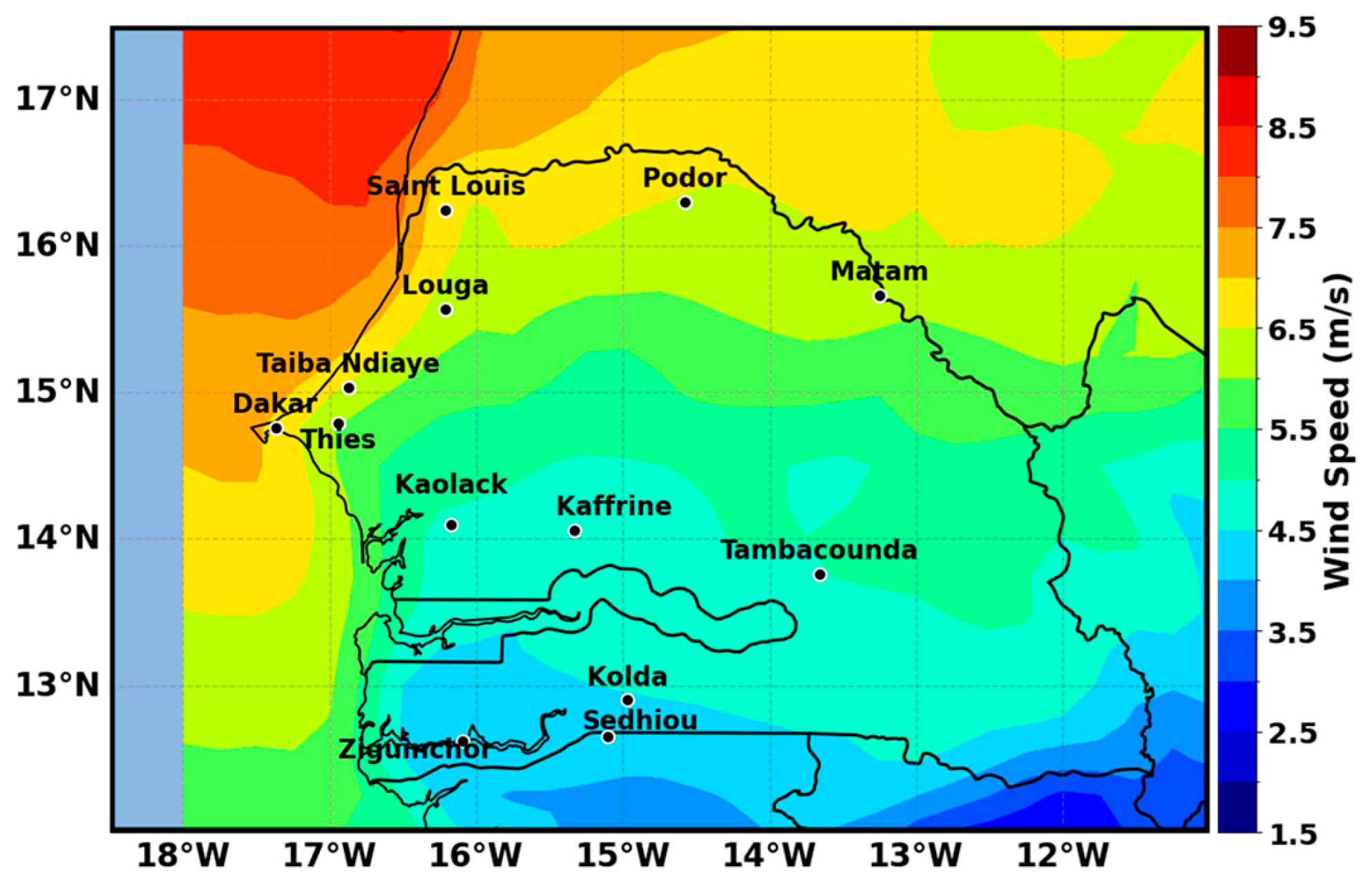

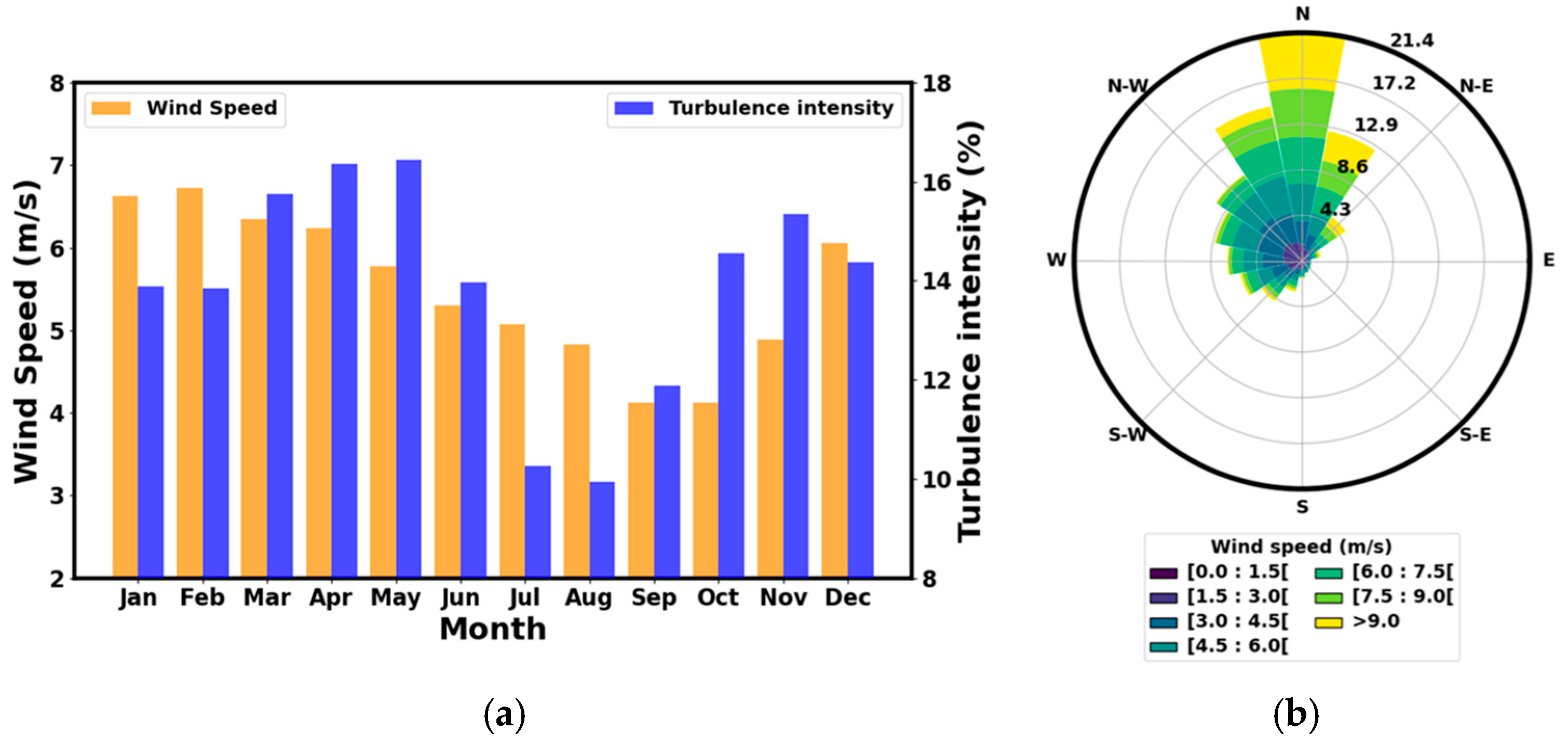

4.1. Spatiotemporal Characterization of Wind Potential

4.2. Technical Analysis and Estimation of Green Hydrogen Production

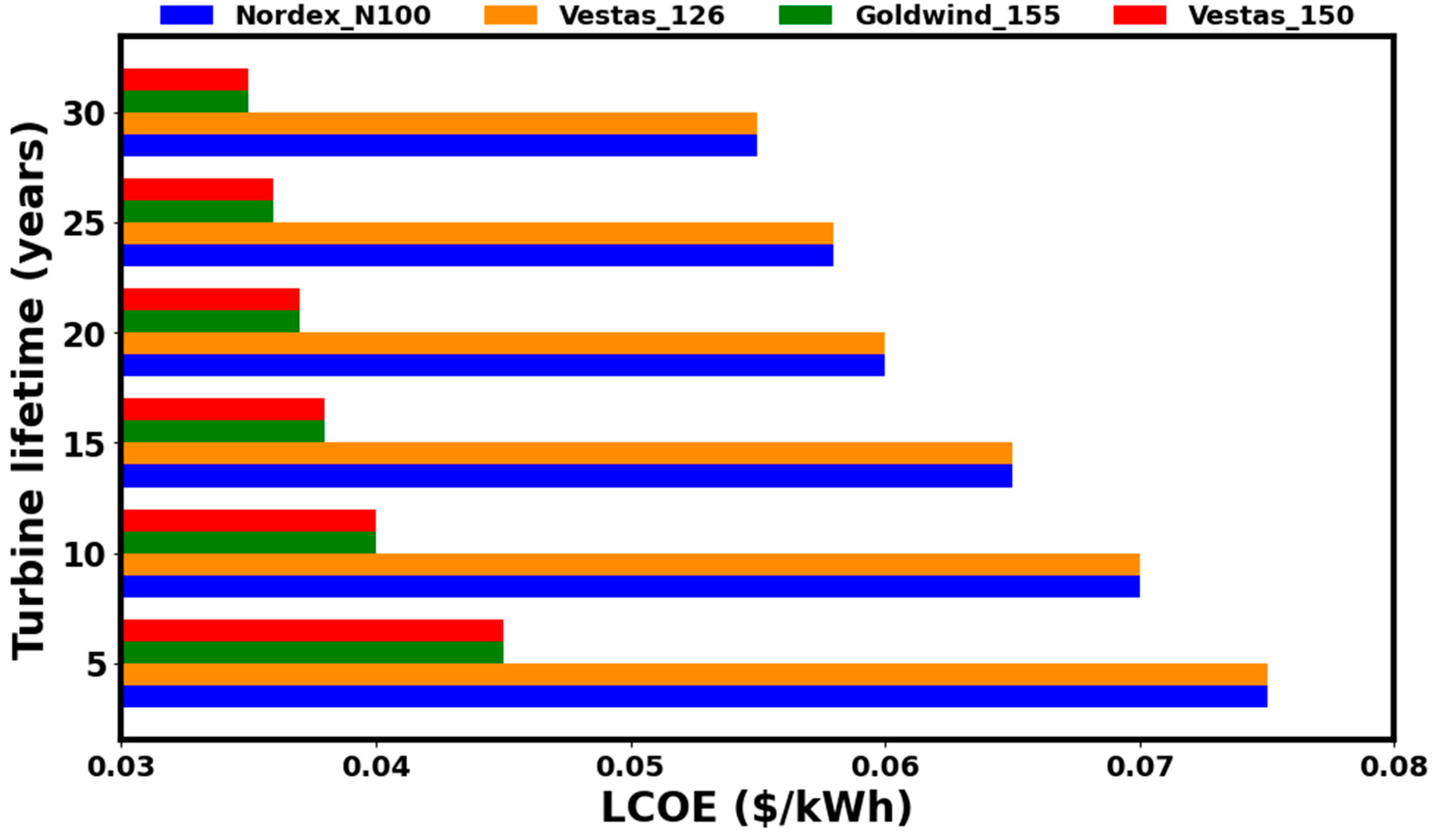

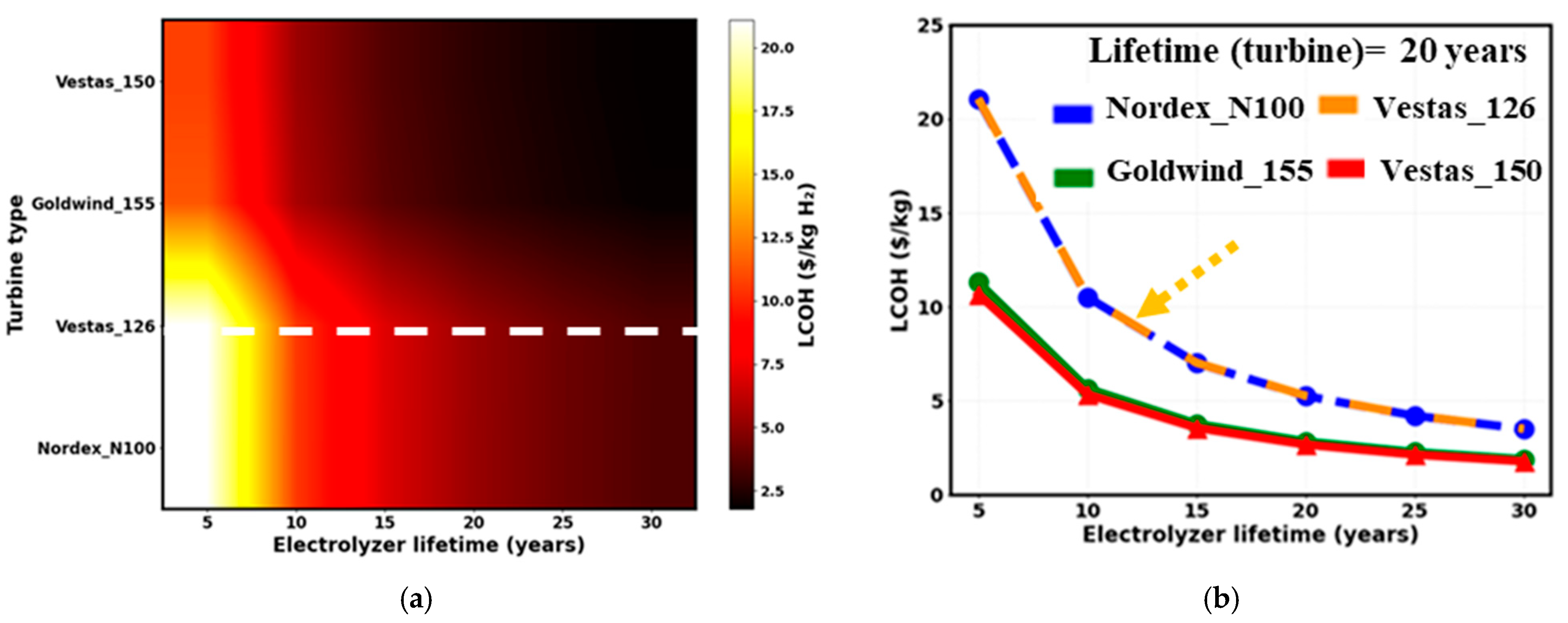

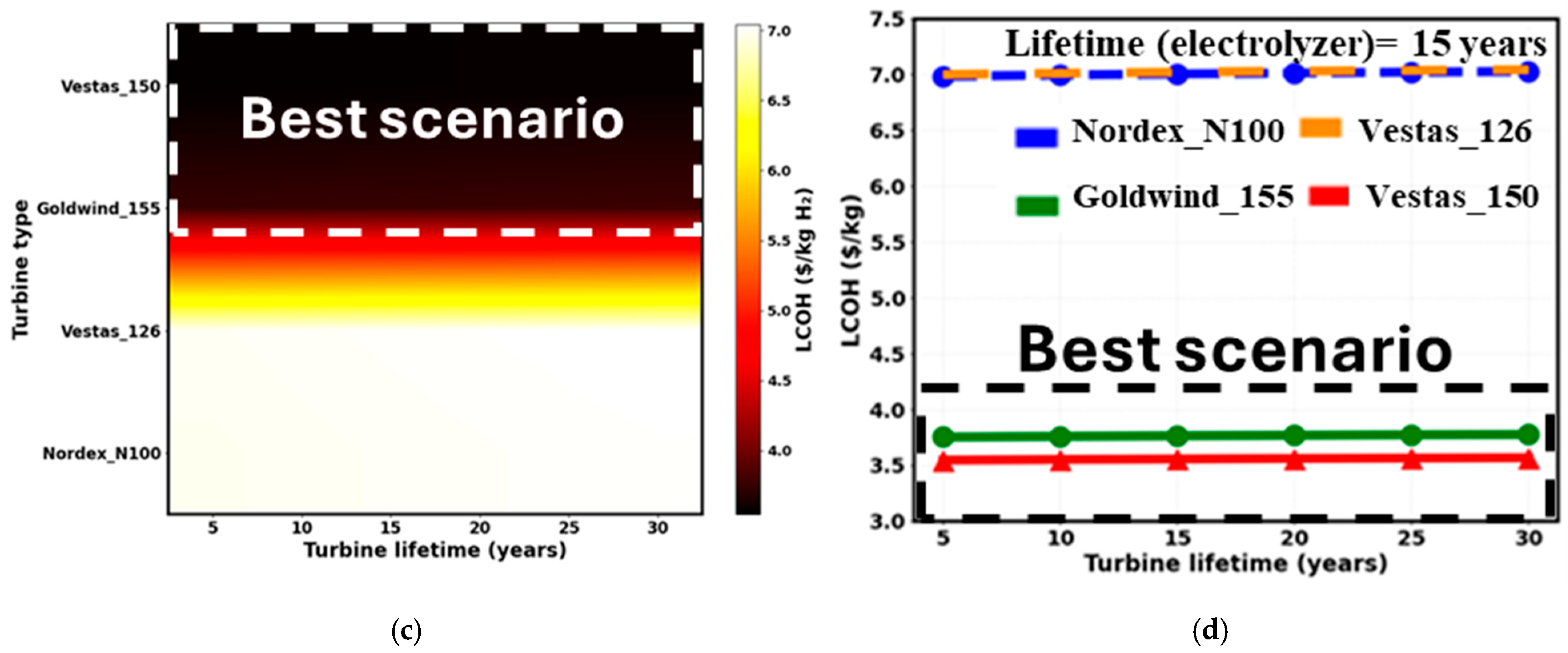

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis on LCOE and LCOH

5. Conclusions, Recommendations and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Nomenclature | |

| Wind shear coefficient | |

| AWE | Alkaline electrolyzer |

| US Dollar | |

| Efficiency of electrolyzer | |

| Conversion efficiency | |

| Scale parameter of Weibull distribution | |

| Scale parameter at | |

| Capital cost of the electrolyzers | |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| Cost of wind electricity | |

| Capacity factor | |

| Scale parameter at extrapolated height | |

| Comr | Operation, maintenance and repair cost |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide emission reduction |

| CCg | Carbon credit gained |

| Cu | Unit cost of wind energy |

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Power |

| CWP | Continental Wind Partners |

| Electrolyzer energy consumption | |

| Energy output | |

| ECMWF | European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| EPFM | Energy pattern factor method |

| h | Extrapolated height |

| Initial height | |

| H2 | Amount of hydrogen |

| I | Investment cost |

| i | Inflation rate |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| ITCZ | Intertropical Convergence Zone |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| JETP | Just Energy Transition Partnership |

| Shape parameter of Weibull distribution | |

| Shape parameter at | |

| Shape parameter at extrapolated height | |

| LCOE | Levelized cost of electricity |

| LCOH | Levelized cost of Hydrogen |

| Million | |

| n | Exponent |

| Average power output | |

| Rated electrical power | |

| PEM | Proton exchange electrolyzer |

| r | Interest rate |

| ETN | Electricity Network Transmission |

| t | Time |

| SOEC | Solid Oxide Electrolyzers |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| T | The operational life of the electrolyzer |

| Wind speed | |

| Wind speed at | |

| Cut-in wind speed | |

| Cut-off wind speed | |

| Rated wind speed | |

References

- Askari, M.; Parsa, N. A Techno-Economic Analysis of the Interconnectedness between Energy Resources, Climate Change, and Sustainable Development. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.12235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (Ed.) Climate Change 2022—Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector; Int Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021; Volume 224. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Al-Ghussain, L.; Alrbai, M.; Al-Dahidi, S. Integrating Hybrid PV/Wind-Based Electric Vehicles Charging Stations with Green Hydrogen Production in Kentucky through Techno-Economic Assessment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Algburi, S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Al-Jiboory, A.K. A Review of Green Hydrogen Production by Renewable Resources. Energy Harvest. Syst. 2024, 11, 20220127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourougianni, F.; Arsalis, A.; Olympios, A.V.; Yiasoumas, G.; Konstantinou, C.; Papanastasiou, P.; Georghiou, G.E. A Comprehensive Review of Green Hydrogen Energy Systems. Renew. Energy 2024, 231, 120911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrouhi, B.E.; Djoupo, J.J.; Lamrani, B.; Benabdelaziz, K.; Kousksou, T. Global Hydrogen Development—A Technological and Geopolitical Overview. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 7016–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewables Readiness Assessment PARAGUAY; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021.

- Ganji, M.D.; Sharifi, N.; Ghorbanzadeh Ahangari, M.; Khosravi, A. Density Functional Theory Calculations of Hydrogen Molecule Adsorption on Monolayer Molybdenum and Tungsten Disulfide. Phys. Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2014, 57, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaño, R.L. Assessment of Environmental Impact and Energy Performance of Rice Husk Utilization in Various Biohydrogen Production Pathways. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 299, 122590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kim, J. Multi-Site and Multi-Period Optimization Model for Strategic Planning of a Renewable Hydrogen Energy Network from Biomass Waste and Energy Crops. Energy 2019, 185, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Ghorbani, B.; Ziabasharhagh, M. Pinch and Sensitivity Analyses of Hydrogen Liquefaction Process in a Hybridized System of Biomass Gasification Plant, and Cryogenic Air Separation Cycle. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrbai, M.; Al-Dahidi, S.; Al-Ghussain, L.; Shboul, B.; Hayajneh, H.; Alahmer, A. Assessment of the Polygeneration Approach in Wastewater Treatment Plants for Enhanced Energy Efficiency and Green Hydrogen/Ammonia Production. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 192, 803–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhal, T.; Agrouaz, Y.; Kousksou, T.; Allouhi, A.; El Rhafiki, T.; Jamil, A.; Bakkas, M. Technical Feasibility of a Sustainable Concentrated Solar Power in Morocco through an Energy Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, B.H.M. Modelling Energy Sector Integration Using Green Hydrogen to Define Public Policies and New Regulatory Support Schemes to Accelerate Energy Transition. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Hydrogen Strategy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Niang, S.A.A.; Cisse, A.; Dramé, M.S.; Diallo, I.; Diedhiou, A.; Ndiaye, S.O.; Talla, K.; Dioum, A.; Tchakondo, Y. A Tale of Sustainable Energy Transition Under New Fossil Fuel Discoveries: The Case of Senegal (West Africa). Sustainability 2024, 16, 10633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, S.A.A.; Gueye, A.; Sarr, A.; Diop, D.; Goni, S.; Nebon, B. Comparative Study of Available Solar Potential for Six Stations of Sahel. Smart Grid Renew. Energy 2023, 14, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, A.; Wane, D.; Dione, C.; Gaye, A.T. Assessing Solar Energy Production in Senegal under Future Climate Scenarios Using Regional Climate Models. Sol. Energy Adv. 2025, 5, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, S.A.A.; Gueye, A.; Drame, M.S.; Ba, A.; Sarr, A.; Nebon, B.; Ndiaye, S.O.; Niang, D.N.; Dioum, A.; Talla, K. Analysis of Wind Resources in Senegal Using 100-Meter Wind Data from ERA5 Reanalysis. Sci. Afr. 2024, 26, e02480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, S.A.A.; Drame, M.S.; Gueye, A.; Sarr, A.; Toure, M.D.; Diop, D.; Ndiaye, S.O.; Talla, K. Temporal Dynamics of Energy Production at the Taïba Ndiaye Wind Farm in Senegal. Discov. Energy 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idriss, A.I.; Ahmed, R.A.; Atteyeh, H.A.; Mohamed, O.A.; Ramadan, H.S.M. Techno-Economic Potential of Wind-Based Green Hydrogen Production in Djibouti: Literature Review and Case Studies. Energies 2023, 16, 6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, W.S.A.; Hassan, A.S.M.; Shukri, M.A. Assessing the Performance of Several Numerical Methods for Estimating Weibull Parameters for Wind Energy Applications: A Case Study of Al-Hodeidah in Yemen. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 2725–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnachew, A.G.; Yalew, S.G.; Tesfamichael, M.; Okereke, C.; Abraham, E. A Green Hydrogen Revolution in Africa Remains Elusive under Current Geopolitical Realities. Clim. Policy 2025, 25, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Renewable Energy Opportunities for Mauritania; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023.

- Institut de Recherches Énergétiques et Sociales (IRES). Atlas Cartographique De L’Afrique, 1st ed.; Institut de Recherches Énergétiques et Sociales (IRES): Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boutaghane, A.; Aksas, M.; Chabane, D.; Lebaal, N. Feasibility and Sensitivity Analysis of an Off-Grid PV/Wind Hybrid Energy System Integrated with Green Hydrogen Production: A Case Study of Algeria. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Jen, T.C.; Imoisili, P.E. South Africa Clean Energy Transition: The Future of Green Hydrogen Energy Technology. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 5501–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, A.A.; Hasan, S.; Elshurafa, A.M. The Economics of Off-Shore Wind-Based Hydrogen Production in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 170, 151225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Jung, T.; Dai, H.; Xiang, P.; Chen, S. Transition Pathways for Low-Carbon Steel Manufacture in East Asia: The Role of Renewable Energy and Technological Collaboration. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munther, H.; Hassan, Q.; Khadom, A.A.; Mahood, H.B. Evaluating the Techno-Economic Potential of Large-Scale Green Hydrogen Production via Solar, Wind, and Hybrid Energy Systems Utilizing PEM and Alkaline Electrolyzers. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 5, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Fan, J.; Zheng, L.; Yan, J.; Huo, Y.; Xu, J. Modeling Off-Grid Wind–Solar Hydrogen-Production System in North China. Clean Energy 2025, 9, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A. Green Hydrogen and the Energy Transition: Hopes, Challenges, and Realistic Opportunities. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algburi, S.; Al-Dulaimi, O.; Fakhruldeen, H.F.; Khalaf, D.H.; Hanoon, R.N.; Jabbar, F.I.; Hassan, Q.; Al-Jiboory, A.K.; Kiconco, S. The Green Hydrogen Role in the Global Energy Transformations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Transit. 2025, 8, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younus, H.A.; Al Hajri, R.; Ahmad, N.; Al-Jammal, N.; Verpoort, F.; Al Abri, M. Green Hydrogen Production and Deployment: Opportunities and Challenges. Discov. Electrochem. 2025, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.; Almutairi, M.S.; Harb, K.M.; Marey, O. A Thorough Investigation of Renewable Energy Development Strategies through Integrated Approach: A Case Study. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gado, M.G. Techno-Economic-Environmental Assessment of Green Hydrogen Production for Selected Countries in the Middle East. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 92, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, P.; Li, Z. Optimal Design and Techno-Economic Analysis of a Hybrid Renewable Energy System for off-Grid Power Supply and Hydrogen Production: A Case Study of West China. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 177, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koholé, Y.W.; Fohagui, F.C.V.; Djiela, R.H.T.; Tchuen, G. Wind Energy Potential Assessment for Co-Generation of Electricity and Hydrogen in the Far North Region of Cameroon. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 279, 116765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecave, M.; Candel, S.; Poinsot, T. Hydrogen Today and Tomorrow; French National Research Agency: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Benamara, M.; Bessalem, C.; Diemer, A.; Batisse, C. Les Transitions Énergétiques à l’horizon 2030 et 2050, Le Retour En Grâce Des Scénarios et de La Prospective. Rev. Francoph. Développement Durable 2022, 19, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Q.; Nassar, A.K.; Al-Jiboory, A.K.; Viktor, P.; Telba, A.A.; Awwad, E.M.; Amjad, A.; Fakhruldeen, H.F.; Algburi, S.; Mashkoor, S.C.; et al. Mapping Europe Renewable Energy Landscape: Insights into Solar, Wind, Hydro, and Green Hydrogen Production. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazenberg, W. Green Hydrogen Cost and Reduction Potential; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Uzoagba, C.E.J.; Ikpeka, P.M.; Nnabuife, S.G.; Onwualu, P.A.; Ngasoh, F.O.; Kuang, B. Development of the Hydrogen Market and Local Green Hydrogen Offtake in Africa. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoi-Yorke, F.; Agyekum, E.B.; Adegboye, O.R.; Sekyere, C.K.K. Exploring the Potential of Solar Photovoltaic and Wind-Based Green Hydrogen Projects in ECOWAS Region: Production, Cost, and Environmental Maps. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2025, 43, 2041–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabar, O.A.; Awaleh, M.O.; Waberi, M.M.; Ghiasirad, H.; Adan, A.B.I.; Ahmed, M.M.; Nasser, M.; Juangsa, F.B.; Guirreh, I.A.; Abdillahi, M.O.; et al. Techno-Economic and Environmental Assessment of Green Hydrogen and Ammonia Production from Solar and Wind Energy in the Republic of Djibouti: A Geospatial Modeling Approach. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 3671–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, A.A. Optimal Design for a Hybrid Microgrid-Hydrogen Storage Facility in Saudi Arabia. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2022, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, S.; Diop, M.F.; Faye, T. The Financing of The Energy Transition in Senegal Green Promises, Unequal Gains; Oxfam in Senegal: Dakar, Senegal, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mouhammadou Chamssoudine DIA. Accélérer La Transition Énergétique Au Sénégal: Cadre Régulateur et Gouvernance; Heinrich Böll Stiftung: Dakar, Sénégal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de l’Energie, du Pétrole et des Mines. Lettre de Politique de Développement du Secteur de L’énergie et des Mines 2025–2029; Ministère de l’Energie, du Pétrole et des Mines: Dakar, Sénégal, 2025.

- Rezaei, M.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Jafari, N.; Naghdi-Khozani, N.; Moftakharzadeh, A. Wind and Solar Energy Utilization for Seawater Desalination and Hydrogen Production in the Coastal Areas of Southern Iran. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2020, 18, 1951–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.S.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.J.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Jahangiri, M.; Techato, K. Technical, Economic, Carbon Footprint Assessment, and Prioritizing Stations for Hydrogen Production Using Wind Energy: A Case Study. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 36, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Duong, M. Transition Énergétique: Promesses et Défis Des JETP. Rev. L’énergie 2024, 670, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sarr, M. La Transition du Système Électrique Sénégalais: Regards des Acteurs du Secteur. In Proceedings of the Transition Energétique et Egalité des Genres: Catalyser le Changement en Afrique Par des Politiques de Développement Inclusives, Dakar, Sénégal, 30–31 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Touili, S.; Merrouni, A.A.; El Hassouani, Y.; Amrani, A.I.; Azouzoute, A. Techno-Economic Investigation of Electricity and Hydrogen Production from Wind Energy in Casablanca, Morocco. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpierre, M.; Quist, J.; Mertens, J.; Prieur-Vernat, A.; Cucurachi, S. Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Wind-Based Hydrogen Production in the Netherlands Using Ex-Ante LCA and Scenarios Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 299, 126866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, A.; Javaid, U.; Sajid, M.; Rashid, M.; Uddin, E.; Ayaz, Y.; Waqas, A. Forecasting Hydrogen Production from Wind Energy in a Suburban Environment Using Machine Learning. Energies 2022, 15, 8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.; Megahed, T.F.; Ookawara, S.; Hassan, H. Techno-Economic Assessment of Green Hydrogen Production Using Different Configurations of Wind Turbines and PV Panels. J. Energy Syst. 2022, 6, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedai, A.; Dhakal, R.; Gautam, S.; Kumar Sedhain, B.; Singh Thapa, B.; Moussa, H.; Pol, S. Wind Energy as a Source of Green Hydrogen Production in the USA. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, A.; McStay, D.; Rooney, D.; Robertson, P.; Foley, A. Techno-Economic Analysis to Identify the Optimal Conditions for Green Hydrogen Production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 291, 117230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Hughes, L. The Role for Offshore Wind Power in Renewable Hydrogen Production in Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Akimov, A.; Gray, E.M.A. Techno-Economics of Offshore Wind-Based Dynamic Hydrogen Production. Appl. Energy 2024, 374, 124030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhang, B.; Cai, W.; Zhang, D.; Yan, X.; Yang, T.; Xiao, J. Techno-Economic Analysis of Hydrogen Production Systems Based on Solar/Wind Hybrid Renewable Energy. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023; Volume 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanshir, N.; Pekkinen, S.; Santasalo-Aarnio, A.; Syri, S. Green Hydrogen and Wind Synergy: Assessing Economic Benefits and Optimal Operational Strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 83, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaloum, V.; Bououbeid, E.M.; Ali, M.M.; Yetilmezsoy, K.; Rehman, S.; Ménézo, C.; Mahmoud, A.K.; Makoui, S.; Samb, M.L.; Yahya, A.M. Techno-Economic Analysis of Combined Production of Wind Energy and Green Hydrogen on the Northern Coast of Mauritania. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, B.; Kumagai, H.; Hashimoto, M.; Sugiyama, M. Techno-Economic Assessment of Green Hydrogen Production in Australia Using Off-Grid Hybrid Resources of Solar and Wind. Energies 2025, 18, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, G.R.; Bagheri, B.; Kumagai, H.; Sugiyama, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of Integrated Offshore Wind–Solar Energy Systems for Green Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 180, 151587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakalembe, C.; Frimpong, D.B.; Kerner, H.; Sarr, M.A. A 40-Year Remote Sensing Analysis of Spatiotemporal Temperature and Rainfall Patterns in Senegal. Front. Clim. 2025, 7, 1462626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, D.; Kaly, F.; Dieng, A.L.; Wane, D.; Fall, C.M.N.; Mignot, J.; Gaye, A.T. Regionalization of the Onset and Offset of the Rainy Season in Senegal Using Kohonen Self-Organizing Maps. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, O.; Correia, E.; Fragoso, M. Variability and Trends of the Rainy Season in West Africa with a Special Focus on Guinea-Bissau. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cradden, L.C.; Restuccia, F.; Hawkins, S.L.; Harrison, G.P. Consideration of Wind Speed Variability in Creating a Regional Aggregate Wind Power Time Series. Resources 2014, 3, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sow, E.A.; Vall, M.M.; Abidine, M.M.; Babah, H.; Hamoud, A.; Faye, G.; Semega, B. Assessment of Green Hydrogen Production Potential from Solar and Wind Energy in Mauritania. Geogr. Tech. 2024, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soci, C.; Hersbach, H.; Simmons, A.; Poli, P.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Radu, R.; et al. The ERA5 Global Reanalysis from 1940 to 2022. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2024, 150, 4014–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garniwa, P.M.P.; Azzahra, R.O.; Lee, H.; Aditya, I.A.; Dimyati, R.D.; Sani, I.S.; Ramlah, R.; Garniwa, I.; Sri Sumantyo, J.T.; Dimyati, M. Comparison of Semi-Empirical Models in Estimating Global Horizontal Irradiance for South Korea and Indonesia. Resources 2025, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.; Castro, R. Green Hydrogen Energy Systems: A Review on Their Contribution to a Renewable Energy System. Energies 2024, 17, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2024; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2025; ISBN 9789292606695.

- Hesty, N.W.; Aminuddin; Supriatna, N.K.; Cendrawati, D.G.; Nurliyanti, V.; Nurrohim, A.; Fithri, S.R.; Niode, N.; Al Irsyad, M.I. Unlocking Development of Green Hydrogen Production through Techno-Economic Assessment of Wind Energy by Considering Wind Resource Variability: A Case Study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 138, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouerghi, F.H.; Omri, M.; Menaem, A.A.; Taloba, A.I.; Abd El-Aziz, R.M. Feasibility Evaluation of Wind Energy as a Sustainable Energy Resource. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 106, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabar, O.A.; Awaleh, M.O.; Waberi, M.M.; Adan, A.B.I. Wind Resource Assessment and Techno-Economic Analysis of Wind Energy and Green Hydrogen Production in the Republic of Djibouti. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 8996–9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koung, V.D.P.I.E.; Menga, F.D.; Bonoma, B.; Nsouandele, J.L.; Mouangue, R.M. Technoeconomic Analysis of a Wind Power Generation System and Wind Resource Mapping Using GIS Tools: The Case of Twelve Locations in the Commune of Evodoula, Cameroon. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 8825472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD). En 2022, le Taux D’inflation Annuel Moyen est de 9,7%. Available online: https://www.ansd.sn/flash-stat/en-2022-le-taux-dinflation-annuel-moyen-est-de-97 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Banerjee, A.; Srivastava, R. Production of Green Hydrogen from Wind Energy in India. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. (IJRTE) 2025, 13, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banque Centrale des États de L’afrique de L’ouest. Taux D’intérêt Légal|BCEAO. Available online: https://www.bceao.int/fr/documents/taux-dinteret-legal (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Database SC. SimpleMaps Senegal Cities Database|Simplemaps.Com. Available online: https://simplemaps.com/data/sn-citiess (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Hassan, Q.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. Large-Scale Green Hydrogen Production Using Alkaline Water Electrolysis Based on Seasonal Solar Radiation. Energy Harvest. Syst. 2024, 11, 20230011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim Idriss, A.; Awalo Mohamed, A.; Abdi Atteye, H.; Ali Ahmed, R.; Abdoulkader Mohamed, O.; Cetin Akinci, T.; Ramadan, H.S. Sustainable Pathways for Hydrogen Production: Metrics, Trends, and Strategies for a Zero-Carbon Future. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 73, 104124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Turbines | Hub Height (m) | Per (MW) | Vc (m/s) | Vr (m/s) | Vf (m/s) | Turbine Lifetime (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordex_N100 | 100 | 2.5 | 3 | 12 | 20 | 20 |

| Vestas_126 | 117 | 3.45 | 4.5 | 11.5 | 22 | 20 |

| Goldwind_155 | 140 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 10.8 | 26 | 20 |

| Vestas_150 | 166 | 5.6 | 3 | 11 | 25 | 20 |

| Metrics for Performance Evaluation and References | Unit | Equations | No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical extrapolation of wind speed [39,46,77,78] | m/s | (1) | |

| Wind shear coefficient [22,78] | - | (2) | |

| Average power output [22,46] | kW | (3) | |

| Capacity factor [22,39] | % | (4) | |

| Energy output [22,79,80] | kWh | (5) | |

| Present Value Cost [22,65,79] | $ | (6) | |

| Levelized cost of electricity [65,77,79,80] | $/kWh | (7) | |

| Amount of hydrogen produced by wind turbine [22,39,77] | tons | (8) | |

| Levelized cost of hydrogen [39,77,79] | $/kg | with and | (9) |

| Carbon dioxide emission reduction from wind energy [22,65,79] | tons | (10) | |

| Carbon Credit gained or green credit [22,79] | $ | (11) | |

| Payback Period [22,65,79] | years | PBP = (ln ((C + i)/(EA × C)) + 1)/(ln(1 + i)) | (12) |

| Input Parameters and References | Unit | Electrolyzers | Values | No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflation rate [81] | % | - | 9.7 | (1) |

| Interest rate [83] | % | - | 5.03 | (2) |

| Operation and Maintenance (O&M) cost (turbine transport, civil works, grid connection and related setup costs) [22] | % | - | 25 | (3) |

| Scrap value [22] | % | - | 10 | (4) |

| Energy consumption of electrolyzer [22] | kWh/kg | Alkaline | 42 | (5) |

| kWh/kg | PEM | 60 | (6) | |

| Efficiency of the converter [22] | % | Alkaline | 95 | (7) |

| % | PEM | 65 | (8) | |

| Efficiency of the electrolyzer [22] | % | Alkaline | 95 | (9) |

| % | PEM | 65 | (10) | |

| Unit cost of the electrolyzer [22] | $/kW | Alkaline | 1522.10 | (11) |

| $/kW | PEM | 2342.07 | (12) | |

| Maintenance and Operation (O&M) cost of electrolyzer [22] | % | Alkaline | 4 | (13) |

| % | PEM | 4 | (14) | |

| Electrolyzer lifetime [22,82] | years | Alkaline | 15 | (15) |

| Electrolyzer lifetime [22,82] | years | PEM | 15 | (16) |

| Wind turbine lifetime [22,82] | years | - | 20 | (17) |

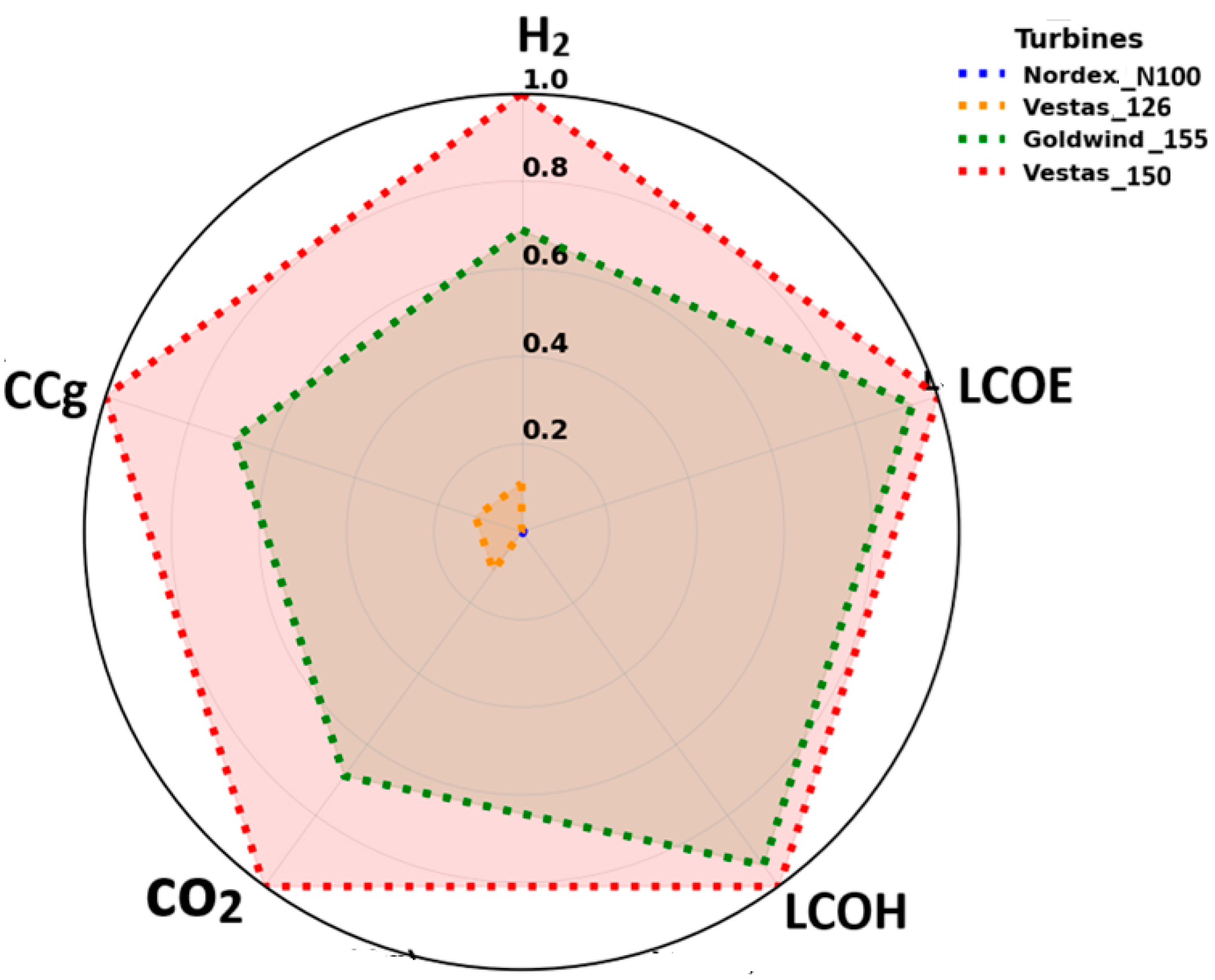

| Parameters | Nordex_N100 | Vestas_126 | Goldwind_155 | Vestas_150 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA (MWh/year) | 2415.34 | 3325.68 | 8091 | 10,656.31 |

| Cfac (%) | 11 | 11 | 20 | 22 |

| LCOE ($/kWh) | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| CO2 em. reduct. (tons) | 669.04 | 921.21 | 2241.2 | 2951.8 |

| CCg (M$) | 0.026 | 0.036 | 0.089 | 0.118 |

| H2 (tons) | 54.63 | 75.22 | 183.01 | 241.03 |

| LCOH ($/kg) | 7.01 | 7.03 | 3.77 | 3.56 |

| PBP (years) | 6.52 | 6.53 | 3.64 | 2.16 |

| Authors (Year) | Locations | Electrolyzer Technologies | LCOH ($/kg) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koholé et al. (2023) | North region of Cameroon (6 cities) | PEM (54 kWh/kg) | 4.38–15.64 | [39] |

| Qusay et al. (2024) | Iraq | Alkaline (not specified) | 6.82–8.32 | [85] |

| Gado et al. (2024) | Middle East region (10 cities) | PEM (not specified) | 5.34–6.18 | [37] |

| Ibrahim et al. (2024) | Horn of Africa (4 cities) | Alkaline (42 kWh/kg) | 1.17–7.72 | [86] |

| Jiang et al. (2025) | East Asia (2 cities) | Not specified | 2.3–14 | [30] |

| Munther et al. (2025) | Iraq (4 cities) | Alkaline (Not specified) | 8.15–36.1 | [31] |

| Albalawi et al. (2025) | Saudi Arabia | PEM (50 kWh/kg) | 6.93–8.52 | [29] |

| Present study | Senegal | Alkaline (42 kWh/kg) | 3.56–7.03 | Competitive position for green H2 production in West Africa. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sarr, A.; Dramé, M.S.; Niang, S.A.A.; Idriss, A.I.; Ramadan, H.S.M.; Younous, A.A.; Talla, K.; Bagarino, J.R.; Jasper, M.; Diallo, I. Low-Carbon Green Hydrogen Strategies for Sustainable Development in Senegal: A Wind Energy Perspective. Resources 2026, 15, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15010009

Sarr A, Dramé MS, Niang SAA, Idriss AI, Ramadan HSM, Younous AA, Talla K, Bagarino JR, Jasper M, Diallo I. Low-Carbon Green Hydrogen Strategies for Sustainable Development in Senegal: A Wind Energy Perspective. Resources. 2026; 15(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarr, Astou, Mamadou Simina Dramé, Serigne Abdoul Aziz Niang, Abdoulkader Ibrahim Idriss, Haitham Saad Mohamed Ramadan, Ali Ahmat Younous, Kharouna Talla, John Robert Bagarino, Marissa Jasper, and Ismaila Diallo. 2026. "Low-Carbon Green Hydrogen Strategies for Sustainable Development in Senegal: A Wind Energy Perspective" Resources 15, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15010009

APA StyleSarr, A., Dramé, M. S., Niang, S. A. A., Idriss, A. I., Ramadan, H. S. M., Younous, A. A., Talla, K., Bagarino, J. R., Jasper, M., & Diallo, I. (2026). Low-Carbon Green Hydrogen Strategies for Sustainable Development in Senegal: A Wind Energy Perspective. Resources, 15(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources15010009