Assessment of Minimum Support Price for Economically Relevant Non-Timber Forest Products of Buxa Tiger Reserve in Foothills of Eastern Himalaya, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Sampling Design

2.3. The Questionnaire

2.4. Field Data Collection

2.5. Minimum Support Price

- -

- Safeguarding cost: The notional cost of efforts as per government (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act rates, i.e., INR 18.56 per h) to monitor and guard the plant throughout the year with weekly or monthly frequency;

- -

- Abundance/scarcity resource cost is the opportunity cost of the naturally abundant or scarce resource, in which the weightage for an abundant resource is considered to be in the range of 10–20% and weightage for a scarcely available resource is considered to be in the range of 20–33% of the cost of regeneration plus safeguarding cost, which was decided through consultative process considering the potential stock of NTFPs in India [49].

2.6. Demographic Information

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Economic Profile

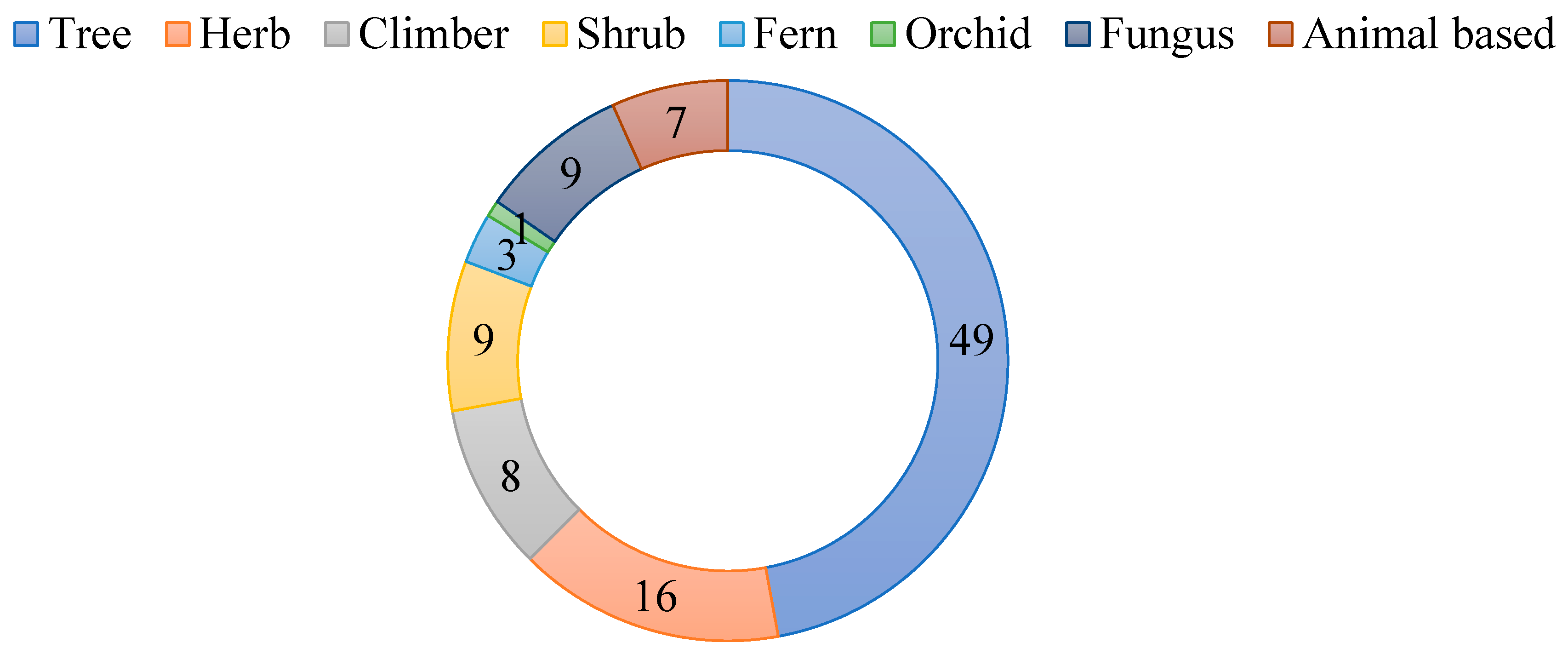

3.2. NTFP Diversity

3.3. Economic Valuation of NTFPs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lepcha, L.D.; Shukla, V.G.; Chakravarty, S. Livelihood dependency on NTFPs among Forest dependent communities. Indian For. 2020, 146, 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- Lepcha, L.D.; Shukla, G.; Pala, N.A.; Vineeta Pal, P.K.; Chakravarty, S. Contribution of NTFPs on livelihood of forest fringe communities in Jaldapara National Park, India. J. Sustain. For. 2018, 38, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Pullanikkatil, D. Considering the links between non-timber forest products and poverty alleviation. In Moving Out of Poverty through Using Forest Products: Personal Stories; Pullanikkatil, D., Shackleton, C.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2022. Forest Pathways for Green Recovery and Building Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Economics; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abhijit Dey, A.D.; De, J.N. Ethnoveterinary uses of medicinal plants by aboriginals of Purulia district, West Bengal, India. Int. J. Bot. 2010, 6, 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bauri, T.; Mukherjee, A. Documentation of traditional knowledge and indigenous use of Non-Timber Forest Products in Durgapur Forest Range of Burdwan District, West Bengal. Ecoscan 2013, 3, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sadashivappa, P.; Suryaprakash, S.; Vijaya Krishna, V. Participation behavior of indigenous people in non-timber forest products extraction and marketing in the dry deciduous forests of South India. In Proceedings of the Conference on International Agricultural Research for Development, Tropentag University of, Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 11–13 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yeshodharan, K.; Sujana, K.A. Wild edible plants traditionally used by the tribes in the Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala, India. Nat. Prod. Radiance 2007, 6, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, N.K.; Yousuf, M. Reassuring livelihood functions of the forests to their dependents: Adoption of collaborative forest management system over joint forest management regime in India. Ann. For. Res. 2013, 56, 377–388. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.A.; Quli, S.M.S.; Rai, R.; Sofi, P.A. Livelihood contributions of forest resources to the tribal communities of Jharkhand. Indian J. Fundam. Appl. Life Sci. 2013, 3, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.; Tripathi, Y.; Kumar, A. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for sustained livelihood challenges and strategies. Res. J. For. 2016, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Mukherjee, S.K. Wild edible plants of Koch Bihar district, West Bengal, India. Nat. Prod. Radiance 2009, 8, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, G.; Chakravarty, S. Ethnobotanical plant use of Chilapatta Reserved Forest in West Bengal. Indian For. 2012, 138, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, G.; Biswas, R.; Das, A.P. Survey for NTFP plants of the Gorumara National Park in the Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal (India). Pleione 2014, 8, 367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bauri, T.; Palit, D.; Mukherjee, A. Livelihood dependency of rural people utilizing non-timber forest product (NTFPs) in a moist deciduous forest zone, West Bengal, India. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 3, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Shackleton, S. The importance of non-timber forest products in rural livelihood security and as safety nets: A review of evidence from South Africa. South Afr. J. Sci. 2004, 100, 658. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Shackleton, S.E.; Buiten, E.; Bird, N. The importance of dry woodlands and forests in rural livelihoods and poverty alleviation in South Africa. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Shanley, P.; Ndoye, O. Invisible but viable: Local markets for non- timber forest products. Int. For. Rev. 2007, 9, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Campbell, B.; Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Shackleton, C.M. Links between the local trade in natural products, livelihoods and poverty alleviation in a semi-arid region of South Africa. World Dev. 2008, 3, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Paumgarten, F.; Kassa, H.; Husselman, M.; Zida, M. Opportunities for enhancing poor women’s socio-economic empowerment in the value chains of three Africa Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs). Int. For. Rev. 2011, 13, 136–151. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, S.; Shackleton, C.M.; Shanley, P. Non-Timber Forest Products in the Global Context; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal, S. Importance of non-timber forest products in native household economy. J. Geogr. Reg. Plan. 2011, 4, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Pandey, A.K. Positioning non-timber forest products on the development agenda. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Lv, H.J.; Vu Thi, H.T.; Zhang, B. Determinants of Non-Timber Forest Product Planting, Development, and Trading: Case Study in Central Vietnam. Forests 2020, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; McNair, M.; Buck, L.; Pimentel, M.; Kamil, J. The value of forests to world food security. J. Hum. Ecol. 1997, 25, 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbridge, S.; Kumar, S. Community, corruption, landscape: Tales from the tree trade. Political Geogr. 2002, 21, 765–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A.K.; Tewari, D.D. Importance of non-timber forest products in the economics valuation of dry deciduous forests of India. For. Policy Econ. 2005, 7, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, I.K.; Leakey, R.; Clement, C.R.; Weber, J.C.; Cornelius, J.P.; Roshetko, J.M.; Vinceti, B.; Kalinganire, A.; Tchoundjeu, Z.; Masters, E.; et al. The management of tree genetic resources and the livelihoods of rural communities in the tropics: Non-timber forest products, smallholder agroforestry practices and tree commodity crops. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 333, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel, T.R. Non-Timber Forest Products of the North-West District of Guyana; Tropenbos Guyana Program: Georgetown, Guyana, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tewari, D.D.; Campbell, J.Y. Increased development of non-Timber Forest products in India: Some issues and concerns. Unasylva 1996, 47, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Vidale, E.; Riccardo, D.R.; Lovric, M.; Pettenella, D. NWFP in the International Market: Current Situation and Trends. Star Tree- Multipurpose Trees and Non-Wood Forest Products: A Challenge and Opportunity. EU FP7 Project no. 311919, Deliverable 3.1. 2014. Available online: https://star-tree.eu/images/deliverables/WP3/D3%201-Int_trade_final.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Lahiri, D. Policy Gap, Issues, Challenges and Methodology in Price Fixation of Minor Forest Produce; The ICFAI University: Dehradun, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shiel, D.; Wunder, S. The value of Tropical Forests to Local Communities: Complications, Caveats and Caution. Conserv. Ecol. 2002, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Misra, S. Role of Role of Non-Timber Forest Products-Based Enterprises in Sustaining Incomes of Forest Dwellers; Indian Institute of Management: Ahmadabad, India, 2010; pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.; Misra, S. Sustainable development: A role for market information systems for non-timber forest products. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, Y.O.; Pretzsch, J.; Pettenella, D. Contribution of non-timber forest products livelihood strategies to rural development in drylands of Sudan. Agric. Syst. 2013, 117, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, C.P. Harvesting and Supply Chain Analysis of Ethnobotanical Species in the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve of India. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2013, 1, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, N.C. Livelihood Diversification and Non-Timber Forest Products in Orissa: Wider Lessons on the Scope for Policy Change? Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wagh, V.V.; Jain, K.A.; Kadel, C. Role of non-timber forest products in the livelihood of tribal community of Jhabua district (M.P). Biol. Forum-Int. J. 2010, 2, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, V.L.; Balkwill, K.; Witkowski, E.T.F. Unravelling the commercial market for medicinal plant and plant parts on the Witwaters and South Africa. Econ. Bot. 2000, 54, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, O.; Lykke, A.M.; Reenberg, A. Importance and seasonality of vegetable consumption and marketing in Burkina Faso. Econ. Bot. 2001, 55, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Dugaya, D. Non-timber forest products certification in India: Opportunities and challenges. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse, G.; Ottitsch, A. Factors influencing the role of non-wood forest products and services. For. Policy Econ. 2005, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawian, J.T.; Jeeva, S.; Lyndem, F.G.; Mishra, B.P.; Laloo, F.G. Wild edible plants of Meghalaya, Northeast India. Nat. Prod. Radiance 2007, 6, 410–426. [Google Scholar]

- Chilalo, M.; Wiersum, K.F. The role of non-timber forest products for livelihood diversification in Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop. e-J. Res. Innov. Foresight 2011, 3, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jhonson, T.S.; Agarwal, R.K.; Agarwal, A. Non-timber forest products as a source of livelihood option for forest dwellers: Role of society, herbal industries and government agencies. Curr. Sci. 2013, 104, 440–443. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty, S.; Bhutia, K.D.; Suresh, C.P.; Shukla, G.; Pala, N.A. A review on diversity, conservation and nutrition of wild edible fruits. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2016, 8, 2346–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.V.; Gokhale, Y.; Jain, N.A.; Lele, Y.; Tyagi, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Methodology for determining minimum support price for minor forest produce in India. Indian For. 2018, 144, 604–610. [Google Scholar]

- Aditya, K.S.; Subash, S.P.; Praveen, K.V.; Nithyashree, M.L.; Bhuvana, N.; Sharma, A. Awareness about minimum support price and its impact on diversification decision of farmers in India. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2017, 4, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, J.L.; Cunningham, A.B.; Nasi, R. Diversity in forest management: Non-timber forest products and bush meat. Renew. Resour. J. 2004, 10, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.K. Growth and composition of ethnic groups in forest villages of Buxa Tiger Reserve, West Bengal. Indian For. 2005, 131, 504–518. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B.; Bhattacharya, D. Reserve Forest and livelihood opportunities: A study on Buxa tiger reserve. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2016, 3, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P.B.; Shah, R. Economic loss analysis of crops yields due to elephant raiding: A case study of Buxa Tiger Reserve (West), West Bengal, India. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 10, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, H.G.; Seth, S.K. A Revised Survey of the Forest Types of India; Manager of Publications: New Delhi, India, 1968; 404p. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar, S.; Varghese, J.; Prakash, V. Abundance of birds in different habitats in Buxa Tiger Reserve, West Bengal, India. Forktail 2006, 22, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.K. Flood disasters and forest villagers in Sub-Himalayan Bengal. Econ. Political Wkly. 2009, 44, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, V.; Sivakumar, S.; Varghese, J. Avifauna as Indicators of Habitat Quality in Buxa Tiger Reserve, Final Report; 2000–2001, Submitted to West Bengal Forest Department, Mumbai, India; Bombay Natural History Society: Mumbai, India, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.K. Losing Biodiversity, Impoverishing Forest Villagers: Analyzing Forest Policies in the Context of Flood Disaster in a National Park of Sub Himalayan Bengal, India; Occasional Paper, 35; Institute of Development Studies: Kolkata, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frechtling, J.; Sharp, L. User-Friendly Handbook for Mixed Method Evaluations. Directorate for Education and Human Resources, Division of Research, Evaluation and Communication, National Science Foundation 1997.

- Dey, T.; Pala, N.A.; Shukla, G.; Pal, P.K.; Das, G.; Chakravarty, S. Climate change perceptions and response strategies of forest fringe communities in Indian Eastern Himalaya. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 20, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.; Pala, N.A.; Shukla, G.; Pal, P.K.; Chakravarty, S. Perception on impact of climate change on forest ecosystem in protected area of West Bengal. J. For. Environ. Sci. 2017, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, M.C.; Nath, M.R. Financial valuation of non-timber forest products flow from tropical dry deciduous forests in Boudh district, Orissa. Int. J. Farm Sci. 2012, 2, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dolui, G.; Chatterjee, S.; Chatterjee, N.D. The importance of non-timber forest products in tribal livelihood: A case study of Santal Community in Purulia District, West Bengal. Indian J. Geogr. Environ. 2014, 13, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Tiwari, B.K.; Chaturvedi, S.S.; Diengdoh, E. Status, utilization and economic valuation of Non-Timber Forest Products of Arunachal Pradesh, India. J. For. Environ. Sci. 2015, 31, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, A.; Vidyasagaran, K.; Prema, A.; Kumar, V.S. Analyzing the opportunities among the tribes of the Western Ghats in Kerala. Stud. Tribes Tribals 2016, 14, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.N.; Forest Industries Development Group: Asia Pacific Region. Regional Non-Wood Forest Product Industries; FAO: Kualalampur, Malaysia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.K.; Paul, S.K. Sustaining the non-timber forest products (NTFPs) based rural livelihood of tribal’s in Jharkhand: Issues and challenges. Jharkhand J. Dev. Manag. Stud. 2016, 14, 6865–6883. [Google Scholar]

- Baudron, F.; Durieux Chavarria, Y.J.; Remans, R.; Yang, K.; Sunderland, T. Indirect contributions of forests to dietary diversity in Southern Ethiopia. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S.; Liu, J. Community Forest dependency: Dose distance matter? Indian For. 2017, 143, 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A. Non-Timber Forest Products and Their Conservation in Buxa Tiger Reserve, West Bengal, India. Ph. D Thesis, University of North Bengal, Siliguri, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biswakarma, S.; Sarkar, B.C.; Shukla, G.; Pala, N.A.; Chakravarty, S. Traditional application of ethnomedicinal plants in Naxalbari area of West Bengal, India. Int. J. Usufruct Manag. 2015, 16, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, D.; Ghosh, R.; Das (Sarkar), M.; Datta, T.; Biswas, H. Medicinal plants used by tribals in Jalpaiguri district, West Bengal, India. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2015, 3, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sinhababu, A.; Banerjee, A. Ethno-botanical study of medicinal plants used by tribals of Bankura district, West Bengal, India. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2013, 1, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chettri, D.; Moktan, S.; Das, A.P. Ethnobotanical studies on the Tea Garden workers of Darjeeling Hills. Pleione 2014, 8, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, T.; Samanta, S. An ethnobotanical survey on medicinal plants of Ghatal block, West Midnapur District, West Bengal, India. Int. J. Curr. Res. Biosci. Plant Biol. 2014, 1, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, B.C.; Biswakarma, S.; Shukla, G.; Pala, N.A.; Chakravarty, S. Documentation and utilization pattern of ethnomedicinal plants in Darjeeling Himalayas, India. Int. J. Usufruct Manag. 2015, 16, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.J.; Biswakarma, S.; Pala, N.A.; Shukla, G.; Vineeta Kumar, M.; Chakravarty, S.; Bussmann, R.W. Indigenous uses of ethnomedicinal plants among forest-dependent communities of northern Bengal, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2018, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, N.A.; Sarkar, B.C.; Shukla, G.; Chettri, N.; Deb, S.; Bhat, J.A.; Chakravarty, S. Floristic composition and utilization of ethnomedicinal plant in homegardens of the eastern Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2019, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Sarkar, B.C.; Shukla, G.; Debnath, M.K.; Nath, A.J.; Bhat, J.A.; Chakravarty, S. Traditional homegardens and ethnomedicinal plants: Insights from the Indian Sub-Himalayan region. Trees For. People 2022, 8, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Sarkar, B.C.; Manohar, K.A.; Shukla, G.; Vineeta Nath, A.J.; Bhat, J.A.; Chakravarty, S. Fuelwood species diversity and consumption pattern in the homegardens from foothills of Indian Eastern Himalayas. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 96, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Avasthe, R.K.; Shukla, G.; Pradhan, Y. Ethnobotanical edible plant biodiversity of Lepcha Tribes. Indian For. 2012, 138, 798–803. [Google Scholar]

- Uprety, Y.; Poudel, R.C.; Gurung, J.; Chettri, N.; Chaudhary, R.P. Traditional use and management of NTFPs in Kanchenjunga Landscape: Implications for conservation and livelihoods. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2016, 12, 19–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turreira-García, N.; Theilade, I.; Meilby, H.; Sørensen, M. Wild edible plant knowledge, distribution and transmission: A case study of the Achí Mayans of Guatemala. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2015, 11, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Pieroni, A. Folk knowledge of wild food plants among the tribal communities of Thakht-e-Sulaiman Hills, North-West Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2016, 12, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ranjitkar, S.; Huai, H.; Wang, Y. Traditional knowledge and its transmission of wild edibles used by the Naxi in Baidi Village, northwest Yunnan province. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2016, 12, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiracko, N.; Owuor, B.O.; Gakuubi, M.M.; Wanzala, W. A survey of ethnobotany of the Aba Wanga people in Kakamega county, western province of Kenya. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2016, 15, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Alcorn, J.B. Huastec non-crop resource management. Hum. Ecol. 1981, 9, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcorn, J.B. Some factors influencing botanical resource perception among the Huastec: Suggestion for ethnobotanical inquiry. J. Ethnobiol. 1981, 1, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, B.M. Wild edible plants of Chandrapur district, Maharashtra, India. J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2012, 3, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Basumatary, N.; Teron, R.; Saikia, M. Ethnomedicinal practices of the Bodo-Kachari tribe of Karbi Anglong District of Assam. Int. J. Life Sci. Biotechnol. Pharma Res. 2014, 3, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Mallik, R.H. Sustainable management of non-timber forest products in Odisha: Some issues and options. Indian J. Agric. Econ. 2000, 55, 385–397. [Google Scholar]

- Chettri, N.; Sharma, E.; Lama, S.D. Non-timber forest produces utilization, distribution and status in a trekking corridor of Sikkim, India. Lyonia A J. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 1, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Maity, D.; Pradhan, N.; Chauhan, A.S. Folk uses of some medicinal plants from North Sikkim. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2004, 3, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Hore, D.K. Collection and conservation of major medicinal plants of Darjeeling and Sikkim Himalayas. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2007, 6, 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, B.K.; Badola, H.K. Seed germination response of populations of Swertia chirayita following periodical storage. Seed Technol. 2008, 30, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bharati, K.A.; Sharma, B.L. Some ethnoveterinary plant records from Sikkim Himalayas. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2010, 9, 344–346. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.P. Managing the World Forest: Looking for Balance Between Conservation and Development; Kendall Hunt Publishing Company: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1992; 605p. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, U.; Murali, K.S.; Shaanker, R.U.; Ganeshaiah, K.N.; Bawa, K.S. Extraction of non-timber forest producers in the forests of Biligiri Rangan hills, India. Econ. Bot. 1996, 50, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Das, S.; Sinha, S. Value addition options for non-timber forest products at primary collector’s level. Int. For. Rev. 1999, 1, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Marles, R.J. Non-Timber Forest Products and Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge; North Central Research Station: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dattagupta, S.; Gupta, A.; Ghose, M. Non-Timber Forest Products of the Inner Line Reserve Forest, Cachar, Assam, India: Dependency and usage pattern of forest-dwellers. Assam Univ. J. Sci. Technol. Biol. Environ. Sci. 2010, 6, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal, S. The role of all marketing channels in NTFP business. J. Sustain. For. 2013, 31, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S. Cross Boarder Trading of Kendu Leaf in Odisha. Asian J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2014, 4, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.U.; Jana, S.K.; Roy, S.D. Marketing of non-timber forest products- a study in Paschim Medinipur district in West Bengal, India. Intercont. J. Mark. Res. Rev. 2016, 4, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, O. The potential of harvesting fruits in tropical rain forests: A new data from Amazonian Peru. Biol. Conserv. 1993, 2, 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Maikhuri, R.K.; Semwal, R.L.; Singh, A.; Nautiyal, M.C. Wild fruits as a contribution to sustainable rural development: A case study from the Garhwal Himalaya. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 1994, 1, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.M.; Hammett, A.L.; Kant, S. Non-timber forest products marketing systems and market players in southwest Virginia: Craft, medicinal and herbal, and specialty wood products. J. Sustain. For. 2000, 11, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, V.K.; Anitha, D. Mapping of non-timber forest products using remote sensing and GIS. Int. Soc. Trop. Ecol. 2010, 51, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

| Sr. No. | Name of the Village | Total Household | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pompu busty | 58 | 6 |

| 2 | Naya busty | 73 | 7 |

| 3 | Chettri line busty | 81 | 8 |

| 4 | Suntala bari busty | 165 | 16 |

| 5 | 28 miles busty | 135 | 13 |

| 6 | 29 miles busty | 118 | 12 |

| 7 | Jayantia busty | 143 | 14 |

| 8 | Bhutia busty | 91 | 9 |

| 9 | Sardar bazar | 83 | 8 |

| 10 | Ochulung busty | 68 | 7 |

| Profile Class | f (%) | Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||

| 20–30 | 19 | Range: 20–78; Mean: 44.94; SD: 14.87 |

| 30–40 | 20 | |

| 40–50 | 16 | |

| 50–60 | 37 | |

| 60–70 | 11 | |

| 70> | 3 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 53 | |

| Female | 47 | |

| Formal education (in years) | ||

| 0 | 36 | |

| 1–5 | 46 | |

| 6–12 | 16 | |

| >12 | 2 | |

| Monthly income (INR) | ||

| Low | 92 | Range: 2000–45,000; Mean: 9731; SD: 9553.5 |

| Moderate | 8 | |

| High | 0 | |

| Monthly NTFP income (INR) | ||

| Low < 10% | 28 | Range: 0–80; Mean: 25%; SD: 0.24 |

| Moderate 10–30% | 35 | |

| High > 30% | 37 | |

| Occupation | ||

| Farming | 33 | |

| Ensured daily wage worker | 26 | |

| Non-ensured daily wage worker | 23 | |

| Tourism | 18 | |

| Sn | VN/SN | IT | HR (INR) | MR (INR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal-based | ||||

| 1 | Jhingay Euphausia superba | Krill | 500/kg | 600/kg |

| 2 | Samuk Bellamya bengalensis | Snail | 50/kg | 85/kg |

| 3 | Magur macha Clarias batrachus | Fish | 400/kg | 600/kg |

| 4 | Punthi Puntius ticto | Fish | 100/kg | 200/kg |

| 5 | Putka Trigona sp. | Honey | 250/L | 350/L |

| Fungal-based | ||||

| 6 | Ful cheu (Golden fungus) Flammulina spp. | Fruiting body | 100/kg | 130/kg |

| 7 | Dhabray cheu (Spongy fungus) Morchella esculenta | Fruiting body | 30/kg | 35/kg |

| 8 | Kalunge chew Termitomyces clypeatus | Mushroom | 150/kg | 210/kg |

| 9 | Kath cheu Ganoderma lucidum | Mushroom | 100/kg | 130/kg |

| Plant-based | ||||

| 10 | Neem Azadirachta indica | Fresh twigs | 10/bunch | 15/bunch |

| 11 | Narkeli Pterygota alata | Seed, flower | 20/kg | 30/kg |

| 12 | Chaap Magnolia pterocarpa | Dry flowers | 20/kg | 23/kg |

| 13 | Lotho/Kusum Baccaurea sapida | Fruit | 0.70/pc | 1/pc |

| 14 | Phata lali Aglaia hiernii | Seed | 10/kg | 13/kg |

| 15 | Chikrasi Chukrasia tabularis | Dry seed coat | 20/kg | 22/kg |

| 16 | Odal Sterculia villosa | 20/kg | 25/kg | |

| 17 | Ningro Allantodia maxima | Twigs | 10/bunch | 15/bunch |

| 18 | Laal latta lahara | Wp | 35/kg | 40/kg |

| 19 | Ningura lahara | Wp | 35/kg | 40/kg |

| 20 | Kucho Thysanolaena latifolia | Broomstick | 600/1000 sticks | 650/1000 sticks |

| 21 | Totola Oroxylum indicum | Pod | 20/pod | 30/pod |

| 22 | Jhut Luffa aegyptica | Fruit | 10/pc | 20/strip |

| 23 | Bel Aegle marmelos | Twig, fruit | 5/bunch 7/fruit | 8/bunch, 10/fruit |

| 24 | Jungali haldi Curcuma aromatica | Rhizome | 150/kg | 200/kg |

| 25 | Tamba Bambusa vulgaris | Young shoot | 90/kg | 120/kg |

| 26 | Ghar tarul Dioscorea deltoidea | Tuber | 80/kg | 110/kg |

| 27 | Ban tarul Dioscorea alata L. | Tuber | 80/kg | 100/kg |

| 28 | Documented species | Fuel wood | 500/pile | 600/pile |

| NTFP | Household Rate * (INR) | Suggested MSP (INR) |

|---|---|---|

| Ful cheu (Golden fungus) | 100/kg | 130/kg |

| Dhabray cheu (Spongy fungus) | 30/kg | 48/kg |

| Phata lali | 10/kg | 30/kg |

| Narkeli | 20/kg | 30/kg |

| Kucho (Broomsticks) | 0.6/stick | 1.4/stick |

| Odal | 20/kg | 25/kg |

| Chaap | 20/kg | 25/kg |

| Laal latta lahara | 35/kg | 47/kg |

| Ningura lahara | 35/kg | 47/kg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gurung, T.; Giri, A.; Nath, A.J.; Shukla, G.; Chakravarty, S. Assessment of Minimum Support Price for Economically Relevant Non-Timber Forest Products of Buxa Tiger Reserve in Foothills of Eastern Himalaya, India. Resources 2025, 14, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14060088

Gurung T, Giri A, Nath AJ, Shukla G, Chakravarty S. Assessment of Minimum Support Price for Economically Relevant Non-Timber Forest Products of Buxa Tiger Reserve in Foothills of Eastern Himalaya, India. Resources. 2025; 14(6):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14060088

Chicago/Turabian StyleGurung, Trishala, Avinash Giri, Arun Jyoti Nath, Gopal Shukla, and Sumit Chakravarty. 2025. "Assessment of Minimum Support Price for Economically Relevant Non-Timber Forest Products of Buxa Tiger Reserve in Foothills of Eastern Himalaya, India" Resources 14, no. 6: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14060088

APA StyleGurung, T., Giri, A., Nath, A. J., Shukla, G., & Chakravarty, S. (2025). Assessment of Minimum Support Price for Economically Relevant Non-Timber Forest Products of Buxa Tiger Reserve in Foothills of Eastern Himalaya, India. Resources, 14(6), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14060088