Low-Quality Coffee Beans Used as a Novel Biomass Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals: Extraction and Application in Sustainable Packaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Biomass Processing

2.2. Alkaline Treatment of Plant Biomass

2.3. Quantification of Lignocellulosic Biomolecules in Fresh and Clarified Coffee Fibers

2.4. Cellulose Nanocrystal Extraction

2.5. Atomic Force Microscopy

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.7. Zeta Potential

2.8. X-Ray Diffractometry

2.9. Thermogravimetry

2.10. Bioplastics Production

2.11. Characterization of the Bioplastics

2.11.1. Moisture Content

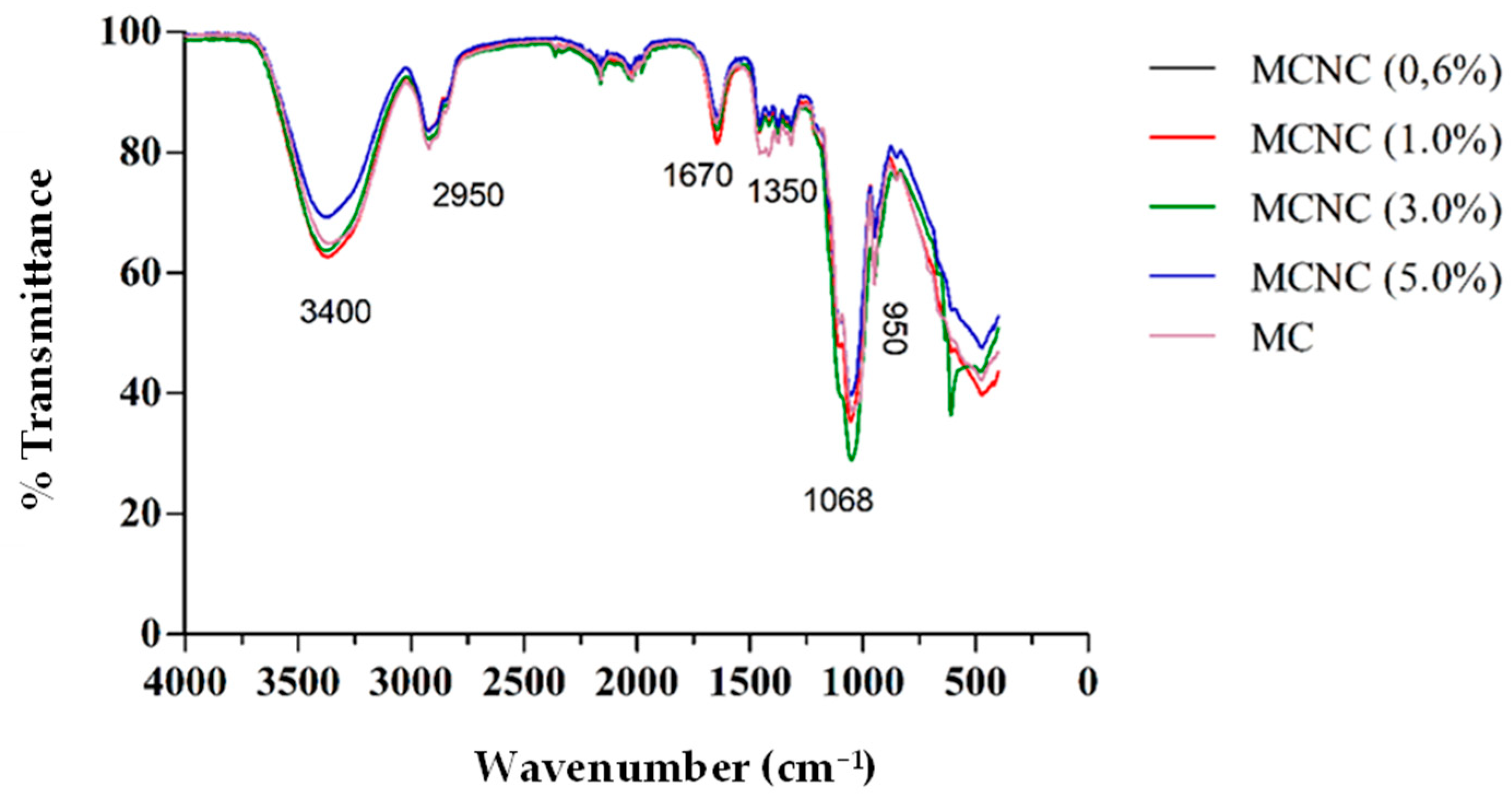

2.11.2. FTIR

2.11.3. Color Analysis

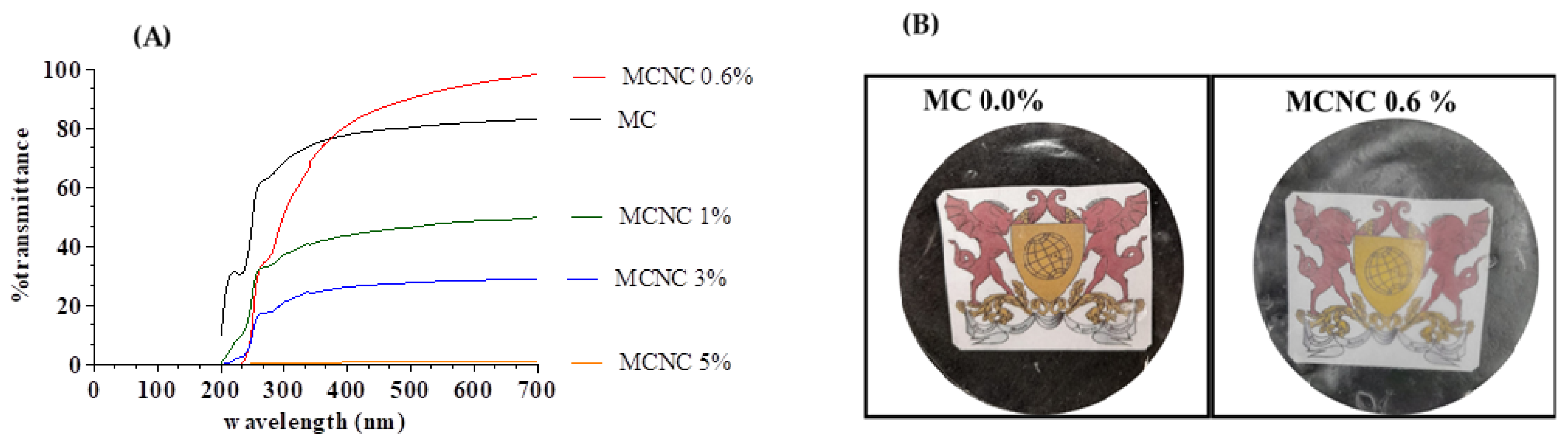

2.11.4. UV-Vis Analysis

2.11.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.11.6. Thermogravimetry

2.11.7. Tensile Test

2.11.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantification of Biomolecules

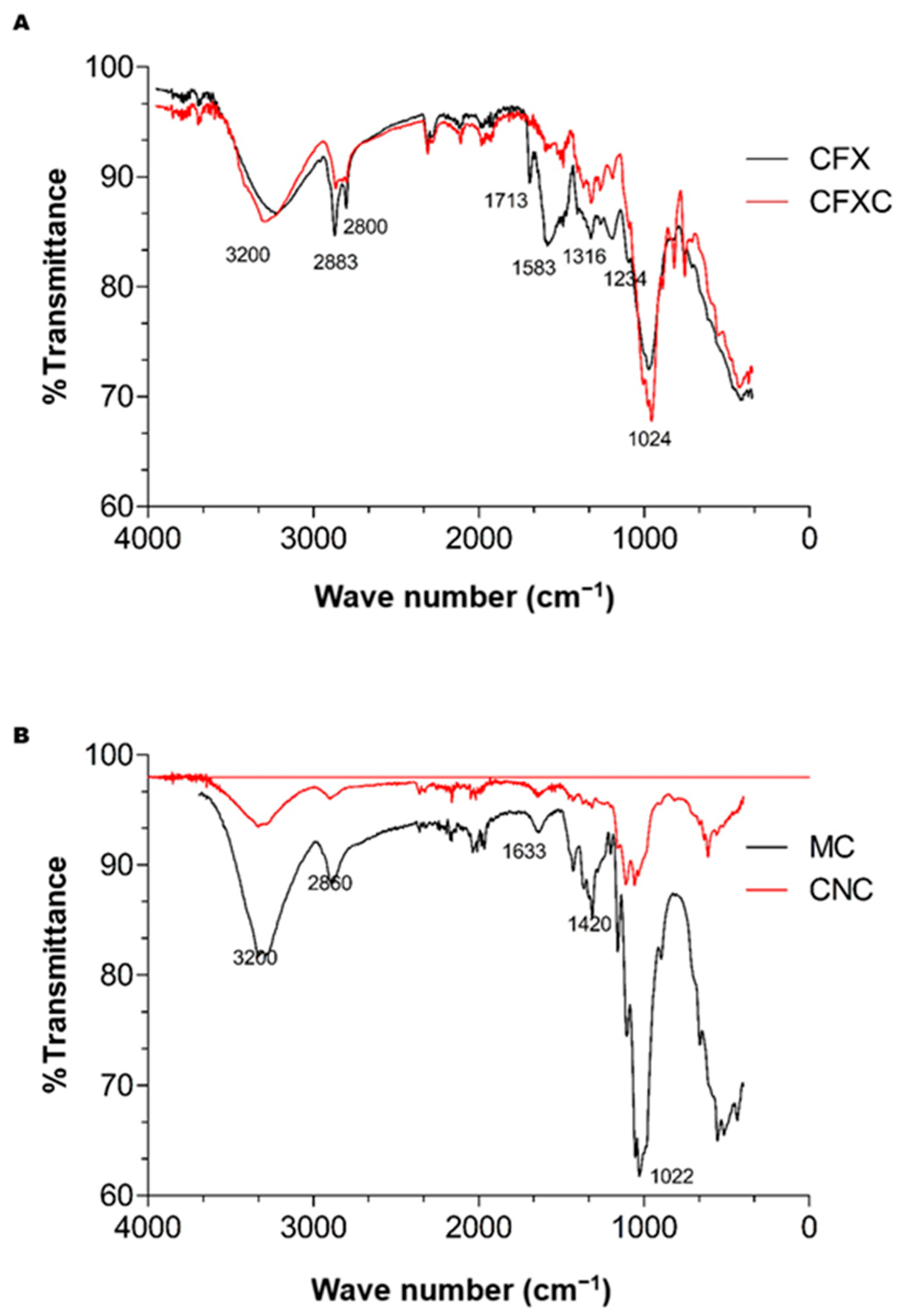

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry

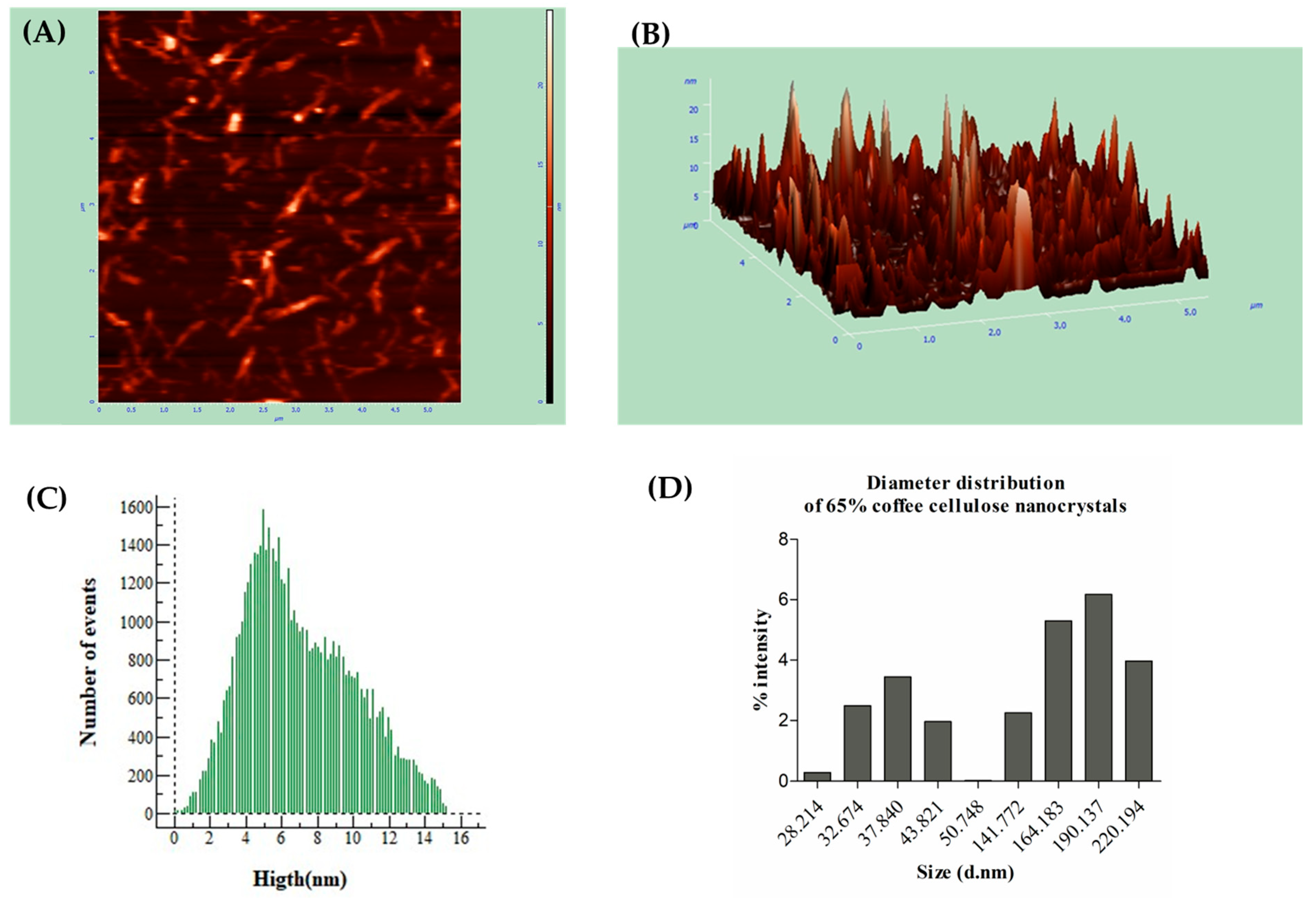

3.3. Nanoparticle Morphology Characterization

3.4. Zeta Potential

3.5. XRD

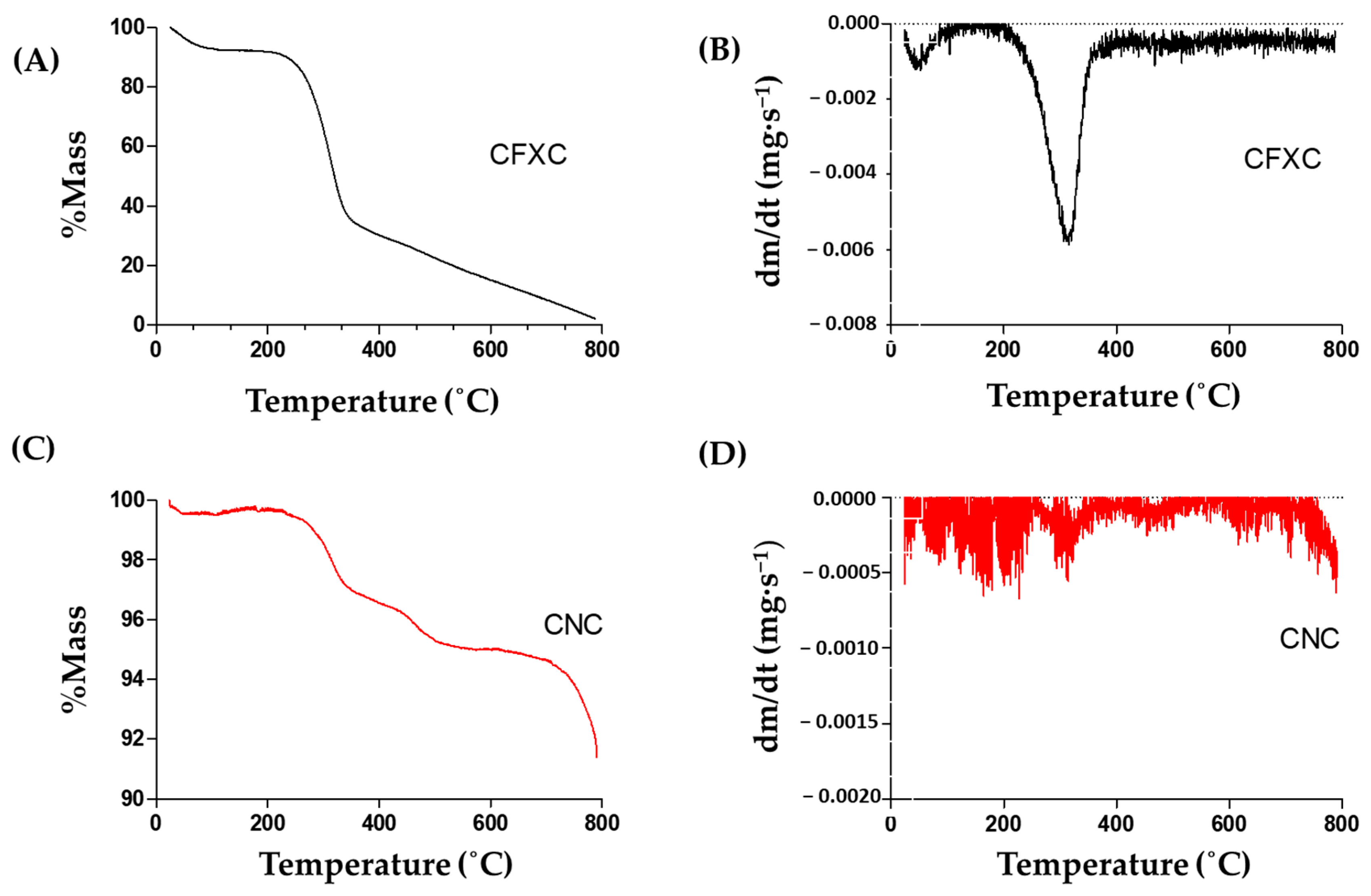

3.6. Thermogravimetry

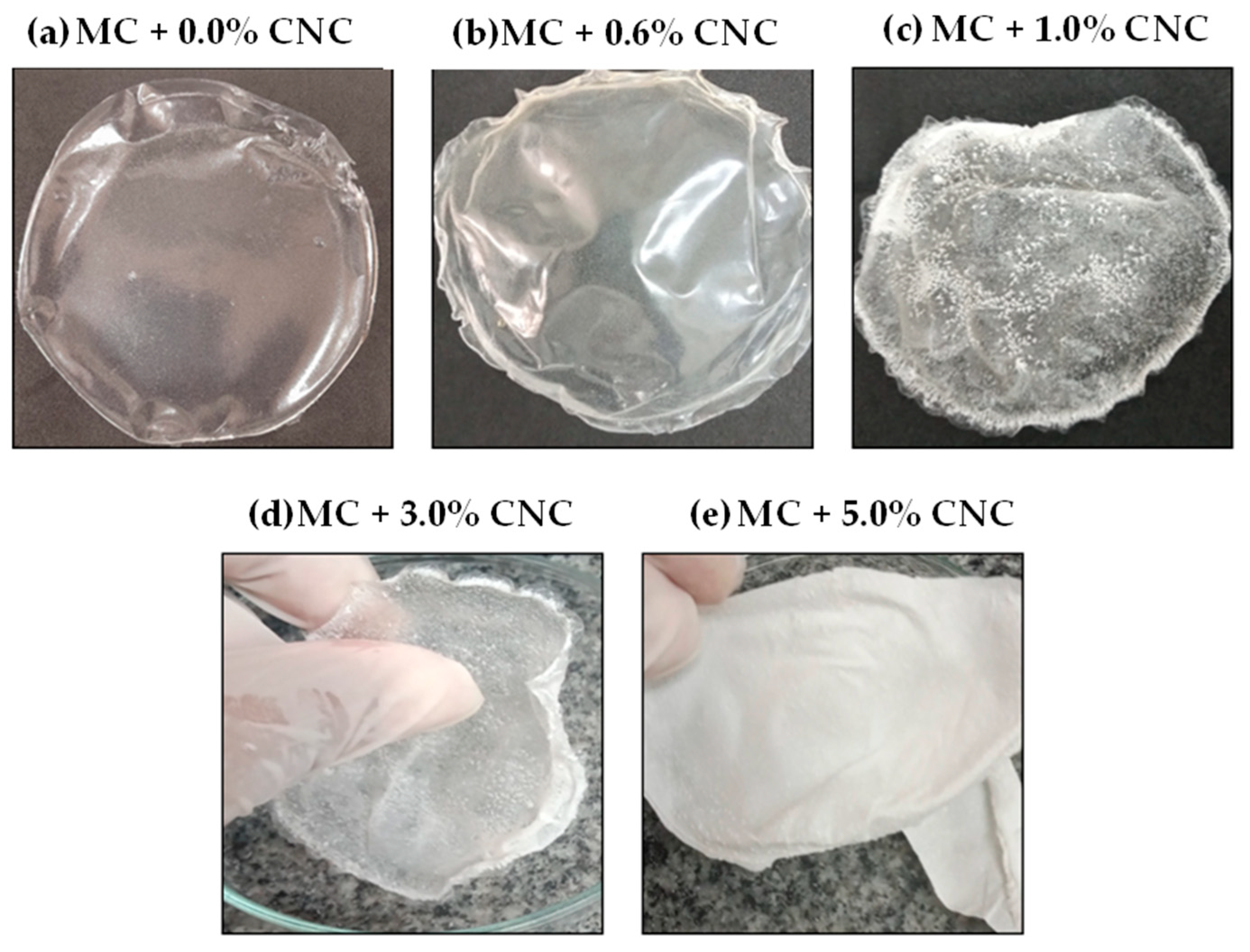

3.7. Characterization of Bioplastics

3.7.1. Color and UV Blocker Analyses

3.7.2. Thermogravimetric

3.7.3. Tensile Test

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Przygrodzka, K.; Charęza, M.; Banaszek, A.; Zielińska, B.; Ekiert, E.; Drozd, R. Bacterial Cellulose Production by Komagateibacter Xylinus with the Use of Enzyme-Degraded Oligo- and Polysaccharides as the Substrates. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etale, A.; Onyianta, A.J.; Turner, S.R.; Eichhorn, S.J. Cellulose: A Review of Water Interactions, Applications in Composites, and Water Treatment. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2016–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emenike, E.C.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Saliu, O.D.; Ramontja, J.; Adeniyi, A.G. Advances in the Extraction, Classification, Modification, Emerging and Advanced Applications of Crystalline Cellulose: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023, 6, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, J.R.A.; Souza, V.G.L.; Fernando, A.L. Valorization of Energy Crops as a Source for Nanocellulose Production—Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.L.; Souza, V.G.L.; Jesus, M.; Mata, F.; Oliveira, T.V.d.; Soares, N.d.F.F. Modification of Cellulose Nanocrystals Using Polydopamine for the Modulation of Biodegradable Packaging, Polymeric Films: A Mini Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusiya, G.; Jaiganesh, R. A Review on Fabrication Methods of Nanofibers and a Special Focus on Application of Cellulose Nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 4, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Zhao, H.; Mo, Q.; Pan, D.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.; Xu, H.; Hu, B.; Song, H. From Cellulose to Cellulose Nanofibrils—A Comprehensive Review of the Preparation and Modification of Cellulose Nanofibrils. Materials 2020, 13, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.W.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Fatima, A.; Islam, S.U.; Manan, S.; Ul-Islam, M.; Yang, G. Advanced Biotechnological Applications of Bacterial Nanocellulose-Based Biopolymer Nanohybrids: A Review. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2024, 7, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, S.A.; Azwadi, N.; Sidik, C.; Koten, H. Cellulose Nanocrystals: A Brief Review on Properties and General Applications. J. Adv. Res. Des. 2019, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Omran, A.A.B.; Mohammed, A.A.B.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Rahimian Koloor, S.S.; Petrů, M. Micro- and Nanocellulose in Polymer Composite Materials: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour-Haratbar, A.; Boraei, S.B.A.; Munir, M.T.; Zare, Y.; Rhee, K.Y. A Model for Tensile Strength of Cellulose Nanocrystals Polymer Nanocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 213, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yu, H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Wei, T.; Li, J.; Fan, Z. Nanocellulose: A Promising Nanomaterial for Advanced Electrochemical Energy Storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2837–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, R.; Spirk, S.; Nypelö, T. Cellulose Nanocrystal Liquid Crystal Phases: Progress and Challenges in Characterization Using Rheology Coupled to Optics, Scattering, and Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 7931–7945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomri, C.; Cretin, M.; Semsarilar, M. Recent Progress on Chemical Modification of Cellulose Nanocrystal (CNC) and Its Application in Nanocomposite Films and Membranes-A Comprehensive Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 294, 119790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdoch, W.; Cao, Z.; Florczak, P.; Markiewicz, R.; Jarek, M.; Olejnik, K.; Mazela, B. Influence of Nanocellulose Structure on Paper Reinforcement. Molecules 2022, 27, 4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Farid, A.; Haq, F.; Kiran, M.; Ullah, A.; Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Ghazanfar, S.; Sun, H.; Ullah, R.; et al. A Review on the Modification of Cellulose and Its Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrapa Safra Dos Cafés Do Brasil de Coffea Arábica Atinge 38.90 Milho~es de Sacas e Equivale a 40% Da Produção Mundial Dessa Espécie. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/en/busca-de-noticias/-/noticia/86470599/artigo---safra-dos-cafes-do-brasil-de-coffea-arabica-atinge-3890-milhoes-de-sacas-e-equivale-a-40-da-producao-mundial-dessa-especie#:~:text=tantodeC.,arabicacomodeC.,colhidonoplanetae (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Conab Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento Produção de Café Cresce 8.2% Em 2023 e Chega a 55.1 Milhões de Sacas. Available online: https://www.conab.gov.br/ultimas-noticias/5175-producao-de-cafe-esta-estimada-em-54-36-milhoes-de-sacas-3-maior-na-serie-historica (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Embrapa Produtividade Média Dos Cafés Do Brasil Equivale a 28.9 Sacas Por Hectare Em 2023. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-noticias/-/noticia/80992551/produtividade-media-dos-cafes-do-brasil-equivale-a-289-sacas-por-hectare-em-2023/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Dey, D.; Gyeltshen, T.; Aich, A.; Naskar, M.; Roy, A. Climate Adaptive Crop-Residue Management for Soil-Function Improvement; Recommendations from Field Interventions at Two Agro-Ecological Zones in South Asia. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.H.; Abid, M.; Faisal, M.; Yan, T.; Akhtar, S.; Adnan, K.M.M. Environmental and Health Impacts of Crop Residue Burning: Scope of Sustainable Crop Residue Management Practices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondim, F.F.; Rodrigues, J.G.P.; Aguiar, V.O.; de Fátima Vieira Marques, M.; Monteiro, S.N. Biocomposites of Cellulose Isolated from Coffee Processing By-Products and Incorporation in Poly(Butylene Adipate-Co-Terephthalate) (PBAT) Matrix: An Overview. Polymers 2024, 16, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanai, N.; Honda, T.; Yoshihara, N.; Oyama, T.; Naito, A.; Ueda, K.; Kawamura, I. Structural Characterization of Cellulose Nanofibers Isolated from Spent Coffee Grounds and Their Composite Films with Poly(Vinyl Alcohol): A New Non-Wood Source. Cellulose 2020, 27, 5017–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondam, A.F.; Diolinda da Silveira, D.; Pozzada dos Santos, J.; Hoffmann, J.F. Phenolic Compounds from Coffee By-Products: Extraction and Application in the Food and Pharmaceutical Industries. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.d.O.; Honfoga, J.N.B.; Medeiros, L.L.d.; Madruga, M.S.; Bezerra, T.K.A. Obtaining Bioactive Compounds from the Coffee Husk (Coffea arabica L.) Using Different Extraction Methods. Molecules 2020, 26, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.P.S.; Rosa, M.d.F.; Marconcini, J.M. Procedimentos Para Análise Lignocelulósica—Documento 236; Embrapa: Campina Grande, Brazil, 2010; ISBN 0103-0205. [Google Scholar]

- Martim, J.D. XPowderX, (Version 2023.04.24) [Software]. 2023. Available online: https://www.xpowder.com (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Mclellan, M.R.; Lind, L.R.; Kime, R.W. Hue Angle Determinations and Statistical Analysis for Multiquadrant Hunter L,a,b Data. J. Food Qual. 1995, 18, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C. Film Transparency and Opacity Measurements. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15, 2840–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard, A. ASTM Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. Am. Soc. Test. Mater. West 2012, D882-12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.C.; Ong, V.Z.; Wu, T.Y. Potential Use of Alkaline Hydrogen Peroxide in Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment and Valorization—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.P.; Schmatz, A.A.; de Freita, L.A.; Mutton, M.J.R.; Brienzo, M. Solubilization of Hemicellulose and Fermentable Sugars from Bagasse, Stalks, and Leaves of Sweet Sorghum. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, T.; Nurkhamidah, S.; Altway, A.; Rohmah, A.A.Z.; Saepulah, F. Chemical Pre-Treatments Effect for Reducing Lignin on Cocoa Pulp Waste for Biogas Production. In Proceedings of the 4th International Seminar on Chemistry, Surabaya, Indonesia, 7–8 October 2020; Volume 020058, p. 020058. [Google Scholar]

- Benali, M.; Oulmekki, A.; Toyir, J. The Impact of the Alkali-Bleaching Treatment on the Isolation of Natural Cellulosic Fibers from Juncus Effesus L Plant. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Liang, L.; Meng, X.; Yang, F.; Pu, Y.; Ragauskas, A.J.; Yoo, C.G.; Yu, C. The Physiochemical Alteration of Flax Fibers Structuring Components after Different Scouring and Bleaching Treatments. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 160, 113112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melesse, G.T.; Hone, F.G.; Mekonnen, M.A. Extraction of Cellulose from Sugarcane Bagasse Optimization and Characterization. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1712207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, H.A.; Adeleke, A.A.; Nzerem, P.; Olosho, A.I.; Ogedengbe, T.S.; Jesuloluwa, S. Isolation, Characterization and Response Surface Method Optimization of Cellulose from Hybridized Agricultural Wastes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancera, A.; Fierro, V.; Pizzi, A.; Dumarçay, S.; Gérardin, P.; Velásquez, J.; Quintana, G.; Celzard, A. Physicochemical Characterisation of Sugar Cane Bagasse Lignin Oxidized by Hydrogen Peroxide. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khenblouche, A.; Bechki, D.; Gouamid, M.; Charradi, K.; Segni, L.; Hadjadj, M.; Boughali, S. Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose Microfibers from Retama Raetam Stems. Polímeros 2019, 29, e2019011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, H.; Lee, M.H.; Whiteside, W.S. Physicochemical Characteristics of Cellulose Nanocrystals Isolated from Seaweed Biomass. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 102, 105542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matebie, B.Y.; Tizazu, B.Z.; Kadhem, A.A.; Venkatesa Prabhu, S. Synthesis of Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs) from Brewer’s Spent Grain Using Acid Hydrolysis: Characterization and Optimization. J. Nanomater. 2021, 2021, 7133154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.; Jawaid, M.; Parveez, B.; Zuriyati, A.; Khan, A. Morphological, Chemical and Thermal Analysis of Cellulose Nanocrystals Extracted from Bamboo Fibre. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb Dutta, S.; Patel, D.K.; Ganguly, K.; Lim, K.-T. Isolation and Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Coffee Grounds for Tissue Engineering. Mater. Lett. 2021, 287, 129311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinjokun, A.I.; Petrik, L.F.; Ogunfowokan, A.O.; Ajao, J.; Ojumu, T.V. Isolation and Characterization of Nanocrystalline Cellulose from Cocoa Pod Husk (CPH) Biomass Wastes. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, P.; Ogunsona, E.; Mekonnen, T. Trends in Advanced Functional Material Applications of Nanocellulose. Processes 2018, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei-Ghazvini, A.; Acharya, B. Influence of Cellulose Nanocrystal Aspect Ratio on Shear Force Aligned Films: Physical and Mechanical Properties. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 3, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Luo, Y. Estimation of Aspect Ratio of Cellulose Nanocrystals by Viscosity Measurement: Influence of Aspect Ratio Distribution and Ionic Strength. Polymers 2019, 11, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassab, Z.; Kassem, I.; Hannache, H.; Bouhfid, R.; Qaiss, A.E.K.; El Achaby, M. Tomato Plant Residue as New Renewable Source for Cellulose Production: Extraction of Cellulose Nanocrystals with Different Surface Functionalities. Cellulose 2020, 27, 4287–4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, T.; Belete, A.; Hause, G.; Neubert, R.H.H.; Gebre-Mariam, T. Isolation and Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Different Lignocellulosic Residues: A Comparative Study. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 2964–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, C.F.; Schaak, R.E. Tutorial on Powder X-Ray Diffraction for Characterizing Nanoscale Materials. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 7359–7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, C.J.; Crews, K.D.; Abdalla, M.A.; Russell, A.E.; Curry, M.L. Influence of Strong Acid Hydrolysis Processing on the Thermal Stability and Crystallinity of Cellulose Isolated from Wheat Straw. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 2015, 658163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, F.; Aprilia, S.; Arahman, N.; Bilad, M.R.; Amin, A.; Huda, N.; Roslan, J. Isolation and Characterization of Nanocrystalline Cellulose Isolated from Pineapple Crown Leaf Fiber Agricultural Wastes Using Acid Hydrolysis. Polymers 2021, 13, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T.G.; Crowder, C.E.; Kabekkodu, S.N.; Needham, F.; Kaduk, J.A.; Blanton, T.N.; Petkov, V.; Bucher, E.; Shpanchenko, R. Reference Materials for the Study of Polymorphism and Crystallinity in Cellulosics. Powder Diffr. 2013, 28, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gražulis, S.; Chateigner, D.; Downs, R.T.; Yokochi, A.F.T.; Quirós, M.; Lutterotti, L.; Manakova, E.; Butkus, J.; Moeck, P.; Le Bail, A. Crystallography Open Database—An Open-Access Collection of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq Adil, S.; Bhat, V.S.; Batoo, K.M.; Imran, A.; Assal, M.E.; Madhusudhan, B.; Khan, M.; Al-Warthan, A. Isolation and Characterization of Nanocrystalline Cellulose from Flaxseed Hull: A Future Onco-Drug Delivery Agent. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2020, 24, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, A.B.; Johan Foster, E. Isolation of Thermally Stable Cellulose Nanocrystals from Spent Coffee Grounds via Phosphoric Acid Hydrolysis. J. Renew. Mater. 2020, 8, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Beceiro, J.; Díaz-Díaz, A.M.; Álvarez-García, A.; Tarrío-Saavedra, J.; Naya, S.; Artiaga, R. The Complexity of Lignin Thermal Degradation in the Isothermal Context. Processes 2021, 9, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaruddin, F.A.; Paridah, M.T. Effect of Lignin on the Thermal Properties of Nanocrystalline Prepared from Kenaf Core. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 368, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh Negi, Y.; Choudhary, V.; Kant Bhardwaj, N. Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystals Produced by Acid-Hydrolysis from Sugarcane Bagasse as Agro-Waste. J. Mater. Phys. Chem. 2020, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.H.F.; Ornaghi Júnior, H.L.; Coutinho, L.V.; Duchemin, B.; Cioffi, M.O.H. Obtaining Cellulose Nanocrystals from Pineapple Crown Fibers by Free-Chlorite Hydrolysis with Sulfuric Acid: Physical, Chemical and Structural Characterization. Cellulose 2020, 27, 5745–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Feng, L.; Ding, Z.; Bai, X. Preparation of Spherical Cellulose Nanocrystals from Microcrystalline Cellulose by Mixed Acid Hydrolysis with Different Pretreatment Routes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, I.; Hokkanen, A.; Österberg, M.; Vähä-Nissi, M.; Harlin, A.; Orelma, H. Hybrid Films from Cellulose Nanomaterials—Properties and Defined Optical Patterns. Cellulose 2022, 29, 8551–8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Haque, A.N.M.A.; Naebe, M. Lignin–Cellulose Nanocrystals from Hemp Hurd as Light-Coloured Ultraviolet (UV) Functional Filler for Enhanced Performance of Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanocomposite Films. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Y.; He, Y.; Lan, W.; Ren, J.; Yue, F.; Lu, F. Revealing the Structure-Activity Relationship between Lignin and Anti-UV Radiation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 174, 114212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Kwon, H.-J.; Jeon, S.; Park, J.-W.; Sunthornvarabhas, J.; Sriroth, K. Electrical and Optical Properties of Nanocellulose Films and Its Nanocomposites. In Handbook of Polymer Nanocomposites. Processing, Performance and Application; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 395–432. [Google Scholar]

- Agustin, M.B.; Ahmmad, B.; Alonzo, S.M.M.; Patriana, F.M. Bioplastic Based on Starch and Cellulose Nanocrystals from Rice Straw. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2014, 33, 2205–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blilid, S.; Kędzierska, M.; Miłowska, K.; Wrońska, N.; El Achaby, M.; Katir, N.; Belamie, E.; Alonso, B.; Lisowska, K.; Lahcini, M.; et al. Phosphorylated Micro- and Nanocellulose-Filled Chitosan Nanocomposites as Fully Sustainable, Biologically Active Bioplastics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 18354–18365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherpinski, A.; Torres-giner, S.; Vartiainen, J.; Peresin, M.; Lahtinen, P.; Lagaron, J.M. Improving the Water Resistance of Nanocellulose-Based Films with Polyhydroxyalkanoates Processed by the Electrospinning Coating Technique. Cellulose 2018, 25, 1291–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, N.R.; Pinheiro, I.F.; Alves, G.F.; Mei, L.H.I.; Neto, J.C.M.; Morales, A.R. Role of Cellulose Nanocrystals in Epoxy-Based Nanocomposites: Mechanical Properties, Morphology and Thermal Behavior. Polímeros Ciência e Tecnol. 2021, 31, e2021034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Kim, H.; Jeong, S.; Park, C.; Hwang, H.S.; Koo, B. Changes in Mechanical Properties of Polyhydroxyalkanoate with Double Silanized Cellulose Nanocrystals Using Different Organosiloxanes. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Yin, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y. Effects of Cellulose Nanocrystals and Cellulose Nanofibers on the Structure and Properties of Polyhydroxybutyrate Nanocomposites. Polymers 2019, 11, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.S.F.; Bilatto, S.; Paschoalin, R.T.; Soares, A.C.; Moreira, F.K.V.; Oliveira, O.N.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Bras, J. Eco-Friendly Gelatin Films with Rosin-Grafted Cellulose Nanocrystals for Antimicrobial Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 2974–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, C.C.d.S.; Silva, R.B.S.; Carvalho, C.W.P.; Rossi, A.L.; Teixeira, J.A.; Freitas-Silva, O.; Cabral, L.M.C. Cellulose Nanocrystals from Grape Pomace and Their Use for the Development of Starch-Based Nanocomposite Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 159, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhou, J.; He, M.; Jiang, Q.; Li, A.; Li, S.; Liu, M.; Luo, S.; Zhang, D. Improvement of Polylactic Acid Film Properties through the Addition of Cellulose Nanocrystals Isolated from Waste Cotton Cloth. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, J.R.A.; Souza, V.G.L.; Gomes, L.A.; Coelhoso, I.M.; Godinho, M.H.; Fernando, A.L. Micro and Nanocellulose Extracted from Energy Crops as Reinforcement Agents in Chitosan Films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 186, 115247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Cellulose Nanocrystals Composites with Excellent Thermal Stability and High Tensile Strength for Preparing Flexible Resistance Strain Sensors. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 3, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coffee Biomass | Celullose (%) | Hemicellulose (%) | Lignin (%) | Humidity (%) | Ashes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFX | 22.70 ± 0.02 | 35.80 ± 0.01 | 36.3 ± 0.4 | 9.30 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.04 |

| CFXC | 36.70 ± 0.04 | 52.70 ± 0.02 | 17.0 ± 0.0 | 10.55 ± 0.06 | 1.80 ± 0.05 |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Vibration/Functional Group | Associated Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| 3200 | OH stretching (broad band) | Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin |

| 2883 and 2800 | CH2 stretching | Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin |

| 2860 | Symmetric/asymmetric stretching of methyl and methylene groups | Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin |

| 1713 | Carbonyl (C=O) stretching in esters | Hemicellulose, lignin |

| 1633 | OH stretching | Cellulose, hemicellulose, water, lignin |

| 1583 | Aromatic C=C bending | Lignin aromatic rings |

| 1420 | C6 carbon rocking motion in glucose | Cellulose (crystalline structure, CNC) |

| 1316 | CH bending | Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin |

| 1234 | C–O stretching | Modification/loss of phenolic-OH in lignin |

| 1024 | C–O–C glycosidic bond vibration | Cellulose and hemicellulose |

| 1022 | C–O–C stretching of hexagonal glucose rings | Cellulose (CNC, hexose rings) |

| 2θ | d-Spacing | 2θ | d-Spacing | 2θ | d-Spacing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.9 | 4.704 | 32.0 | 2.795 | 54.654 | 1.678 |

| 22.57 | 3.926 | 33.8 | 2.649 | 55.27 | 1.661 |

| 27.29 | 3.270 | 38.53 | 2.339 | 57.323 | 1.606 |

| 28.0 | 3.182 | 45.53 | 1.988 | 59.492 | 1.552 |

| 28.9 | 3.086 | 48.815 |

| Tests | MC | MCNC 0.6% |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 25 a * ± 4 | 22 a ± 7 |

| Young’s modulus (GPa) | 0.42 a ± 0.01 | 0.0015 b ± 0.0007 |

| % Elongation at break | 1.6 a ± 0.1 | 58 b ± 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paulino, G.d.S.; Pereira, J.S.; Marques, C.S.; Vitalino, K.V.R.; Souza, V.G.L.; Aguilar, A.P.; Almeida, L.F.; de Oliveira, T.V.; Ribon, A.d.O.B.; Ferreira, S.O.; et al. Low-Quality Coffee Beans Used as a Novel Biomass Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals: Extraction and Application in Sustainable Packaging. Resources 2025, 14, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14120191

Paulino GdS, Pereira JS, Marques CS, Vitalino KVR, Souza VGL, Aguilar AP, Almeida LF, de Oliveira TV, Ribon AdOB, Ferreira SO, et al. Low-Quality Coffee Beans Used as a Novel Biomass Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals: Extraction and Application in Sustainable Packaging. Resources. 2025; 14(12):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14120191

Chicago/Turabian StylePaulino, Graziela dos Santos, Júlia Santos Pereira, Clara Suprani Marques, Kyssila Vitória Reis Vitalino, Victor G. L. Souza, Ananda Pereira Aguilar, Lucas Filipe Almeida, Taíla Veloso de Oliveira, Andréa de Oliveira Barros Ribon, Sukarno Olavo Ferreira, and et al. 2025. "Low-Quality Coffee Beans Used as a Novel Biomass Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals: Extraction and Application in Sustainable Packaging" Resources 14, no. 12: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14120191

APA StylePaulino, G. d. S., Pereira, J. S., Marques, C. S., Vitalino, K. V. R., Souza, V. G. L., Aguilar, A. P., Almeida, L. F., de Oliveira, T. V., Ribon, A. d. O. B., Ferreira, S. O., Moura, E. T. C., Silva, D. d. J., & Mendes, T. A. d. O. (2025). Low-Quality Coffee Beans Used as a Novel Biomass Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals: Extraction and Application in Sustainable Packaging. Resources, 14(12), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14120191