Abstract

Tourism-driven growth in Zanzibar has intensified solid waste generation, creating critical environmental and resource management challenges for the hotel sector. This study provides the first comprehensive assessment of the volume, composition, and management of solid waste in Zanzibar’s hotels, establishing a quantitative basis for evidence-based sustainable practices beyond prior research on food waste. Ten hotels were examined through direct waste sampling, structured interviews, and field observations. Results show that hotels generate high levels of unsorted waste (2.45 kg/guest/day), with plastics posing major challenges under the prevailing linear disposal system. Findings reveal that waste patterns depend primarily on management, service, and collection practices, with no significant differences across hotel types or sizes. While the assessment covered the entire waste stream, a tailored circular economy framework is proposed for plastic waste, given its significant contribution to environmental pollution and ecological impact, providing a practical, structured guide for sustainable interventions across hotel operations. Achieving these outcomes requires collaboration, institutional support, and capacity building. By embedding waste audits, reduction strategies, and circular innovations into hotel operations, this framework charts a forward-looking pathway for coastal destinations to transform waste challenges into opportunities, promoting sustainable tourism, resource-use efficiency, and the transition toward a circular economy.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, tourism has become a dynamic global industry [1,2]. While it contributes significantly to job creation and local investment opportunities, it also poses socioeconomic, environmental, and resource-related challenges, with solid waste being among the most significant impacts [3,4]. The severity of tourism-related waste impacts varies depending on the strength of national policies, the type of tourism practiced, and local waste management capacity. Studies highlight that weak governance and inadequate infrastructure often exacerbate environmental pressures in tourism-dependent regions [1,4,5].

Globally, the growth of the tourism industry has triggered a sharp rise in hotel guest numbers, which correlates directly with increased solid waste generation [6,7]. Hotels, restaurants, and related facilities consume large amounts of goods, often packaged in single-use plastics such as miniature toiletries. When multiplied by the number of beds and stays, the waste burden becomes significant [8]. Research highlights this correlation; for example, in Menorca, a 1% increase in tourist arrivals was associated with a 0.282% increase in municipal solid waste [9]. In Malaysia, tourists were found to generate nearly twice as much solid waste per capita as residents [10].

Tourism in Zanzibar has grown significantly over the past three decades [11]. Data from the Zanzibar Commission for Tourism (ZCT) and the Office of the Chief Government Statistician show a steady rise in international arrivals until the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a sharp decline. ZCT (2021, unpublished data) reported that international tourist arrivals dropped from 538,264 in 2019 to 260,644 in 2020—a reduction of over 50%. The reduced arrivals likely translated to a substantial reduction in hotel-generated solid waste. However, the sector showed remarkable resilience; in 2021, arrivals rebounded to 394,185 and surpassed pre-pandemic levels in 2022 with 548,503 visitors [12]. The upward trend continued in 2023 with 638,498 arrivals (a 16.4% increase), reaching a record 736,755 in 2024, a further 15.4% year-on-year growth [13], marking a record in Zanzibar’s tourism history.

The composition of waste in hotels has shifted over time from organic matter toward plastics, a trend closely linked to expanding tourism activities [14,15] (ZEMA, unpublished report, 2022). Plastic waste has emerged as one of the most pressing environmental challenges globally, particularly in tourism-dependent regions where single-use plastics dominate daily operations. Plastics are favored for their affordability and versatility, but their persistence in the environment creates long-term hazards.

Since the 1950s, annual global plastic production has grown from 2 million to 450 million tons by the start of 2023 [16], two-thirds of which are single-use products that soon become waste [17]. Africa, including Zanzibar, is now a significant growth market for plastic products [18]. The rise in single-use plastics such as bottles, bags, and wrappers has intensified waste management issues. An estimated 400 million tons of plastic waste is generated globally each year—equivalent to roughly 2200 bottles per person [16]. Most plastics fragment into microplastics, contributing to marine pollution and ecosystem degradation [19]. Approximately 80% of marine litter is plastic, with between 4.8 and 12.7 million metric tons entering the oceans annually [20,21]. During tourist high seasons, plastic debris on beaches may rise by up to 30%, harming marine life and ecosystems [22].

A study that quantified plastic waste accumulation in coastal tourism sites in Zanzibar reported that tourists generate significantly more plastic waste than local residents, of which only about 9% is recycled [23]. The remainder accumulates in the environment, posing serious ecological and economic risks, particularly to marine ecosystems and key ecotourism attractions. Another 2024 study conducted across five beach transects in Zanzibar—Beit-el-Raas, Fumba, Mbweni, Mangapwani, and Jambiani, recorded a total of 1476 plastic items, accounting for 56.6% of the 2611 items collected. Single-use packaging was identified as the dominant component, underscoring the prevalence of plastic waste along the island’s coastal and marine environments [24].

In low and middle-income countries, including Zanzibar, hotels face significant waste management challenges. These include limited waste management infrastructure, negative managerial attitudes, low staff and guest awareness, lack of enforcement of waste regulations, and the absence of producer responsibility among hotel operators [25]. Many hoteliers perceive waste reduction and recycling as costly and time-consuming [4]. Staff time, special equipment, and energy requirements are often viewed as burdensome, discouraging hotels from embracing sustainability measures [26]. Additionally, frequent changes in local government leadership compromise institutional memory, reducing the long-term effectiveness and continuity of waste management programs [27]. Furthermore, unclear regulatory guidance and poor enforcement prevent both the hospitality sector and local communities from complying with proper waste disposal practices [7,25]. As a result, open dumping remains a common method of waste disposal in many areas, where inadequate infrastructure and limited collection services exacerbate plastic littering, posing risks to marine and terrestrial ecosystems [7]. Zanzibar, being a small island economy that depends deeply on its natural beauty and coastal ecosystems, must prioritize effective solid waste management as a central pillar of sustainability in both policy and practice.

While high-income countries have developed integrated solid waste management (SWM) systems that align environmental and economic goals [28], many low and middle-income countries continue to struggle with fragmented and under-resourced systems [28,29,30]. Inadequate political will, lack of comprehensive SWM policies, insufficient funding, low public awareness, and weak regulatory frameworks are persistent challenges [31,32]. In East Africa, including Zanzibar, service delivery remains poor due to limited financial, human, and technological resources. Local authorities often lack decision-making autonomy and rely heavily on central government transfers, leading to budgetary constraints and ineffective urban waste management [7,33]. Moreover, the implementation of mechanisms such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), which holds producers accountable for the post-consumer stage of their products is still in its infancy in most low-income contexts. Strengthening EPR frameworks could help reduce plastic waste from tourism-related goods, shift responsibility upstream, and support more sustainable material flows [22].

Zanzibar follows a linear system of waste management, whereby most formal documents and guidelines emphasize waste collection and disposal, with limited attention to recovery, recycling, or resource regeneration. A key challenge is the absence of systems thinking and strategic planning, resulting in fragmented and inefficient waste management practices characterized by poor coordination, duplication of efforts, and operational inefficiencies. The situation is further compounded by weak institutional and regulatory frameworks, as enforcement mechanisms are often undermined by the lack of clear operational guidelines, leaving Zanzibar’s waste management system struggling with both structural and operational issues.

Currently, only 45–50% of waste is properly collected, with the rest ending up in public spaces or informal dumpsites, affecting both the environment and daily life (personal communication, ZEMA). A significant portion of unmanaged waste is plastic, particularly single-use plastics from tourism, food packaging, and household consumption. The absence of waste segregation at source exacerbates this issue, making plastic recovery and recycling nearly impossible. Contributing factors include inadequate municipal budgets, weak institutional capacity, and limited collaboration with the private sector [34]. Despite existing regulations banning certain plastic items, enforcement remains limited, and public awareness of plastic pollution is still low (personal communication, ZEMA). Public attitudes toward waste are often marked by indifference, undermining initiatives aimed at behavioral change and contributing significantly to plastic pollution [34]. Meanwhile, tourism remains a significant contributor to the problem, accounting for roughly 30% of Zanzibar’s GDP and 80% of its foreign direct investment [12,30].

According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (2023), up to 80% of the island’s waste is generated by hotels and restaurants [25]. The speed at which tourism is expanding has outpaced the development of waste management infrastructure, rendering the system unsustainable [35]. This mismatch between growth and governance has placed mounting pressure on the island’s environment and service delivery capacity. The Zanzibar hotel sector faces significant capacity gaps in implementing the 4Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle, recover), leading to poor adoption of best practices. These limitations, coupled with weak collaboration among key stakeholders, hinder the development of integrated, locally appropriate waste management solutions, stalling progress toward sustainable tourism, exacerbating environmental degradation, and undermining efforts to transition to a circular economy.

Tourist hotels in Zanzibar are predominantly located along the coast, which presents additional challenges for waste disposal. Poor waste handling practices in coastal areas have been linked to environmental degradation, reduced aesthetic value, and heightened health risks for both local residents and tourists [27,36]. Improperly discarded waste such as bottles and containers becomes a breeding ground for flies, mosquitoes, and other vermin, thereby increasing the risk of disease outbreaks [37,38].

Seasonal spikes in tourist arrivals further strain the waste management system. During peak seasons, waste volumes rise sharply, with studies showing that a single hotel guest may produce between 1 and 2 kg of solid waste per day [39,40]. Accumulated over time, this translates into thousands of tons of waste annually, most of which is disposed of in landfills without treatment, leaving a heavy environmental footprint [41,42]. Given Zanzibar’s reliance on coastal ecosystems for public health, livelihoods, and tourism viability, solid waste management must be addressed not as a narrow sectoral issue but as a central development priority. The seasonal nature of tourism places additional strain on already fragile systems, intensifying pressure on coastal zones and local communities. This necessitates integrated planning that links infrastructure, environmental protection, and meaningful community engagement.

The current scale of waste generation in Zanzibar has surpassed the island’s capacity for effective management [25,43]. Existing practices remain largely linear, emphasizing disposal rather than reduction, recovery, and reuse. Within this broader context, plastic waste particularly littering has emerged as a critical challenge. The rapid expansion of coastal tourism intensifies ecological stress on marine and coastal environments while also creating socioeconomic consequences, including threats to fisheries, the degradation of the destination’s aesthetic appeal, and risks to the long-term sustainability of local livelihoods. Recent studies highlight the urgent need for innovative and sustainable waste management strategies that harness emerging technologies, foster community participation, and embed circular economy principles [35]. However, while several international circular economy models have been proposed, few are adequately adapted to the specific realities of small island developing states or the hotel sector. This study addresses this gap by developing a circular economy framework tailored to plastic waste management in Zanzibar’s hotels.

A holistic strategy is essential, one that emphasizes improving waste collection systems, enabling better segregation and recycling practices, and building institutional and technical capacities across both municipal and private sectors. Against this backdrop, the Greener Zanzibar Campaign, aligned with the broader vision of transforming the island into a model for sustainable tourism, and the recent July 1st directive requiring all hotels to adopt sustainable waste management practices, offer a promising path forward. Together, they reflect a growing commitment to rethinking current waste practices and embracing circular economy principles that can lead to a cleaner, greener future for Zanzibar.

This study aims to elucidate current solid waste management practices in Zanzibar’s tourist hotels and to propose a sustainable, context-specific waste management framework for effective implementation, directly addressing the following research questions:

- How much solid waste is generated in tourist hotels in Zanzibar?

- What types and compositions of solid waste are generated in tourist hotels in Zanzibar?

- How is solid waste currently managed in hotel settings, and how are these practices perceived by stakeholders?

- What key challenges and opportunities shape waste management practices in hotels in Zanzibar?

The goal is to provide evidence-based guidance for hoteliers, municipal authorities, and community stakeholders to strengthen waste management systems and move toward a circular economy framework—where waste is minimized, resources are recovered, and materials are continuously reused—thereby promoting long-term environmental sustainability and economic resilience in the tourism sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

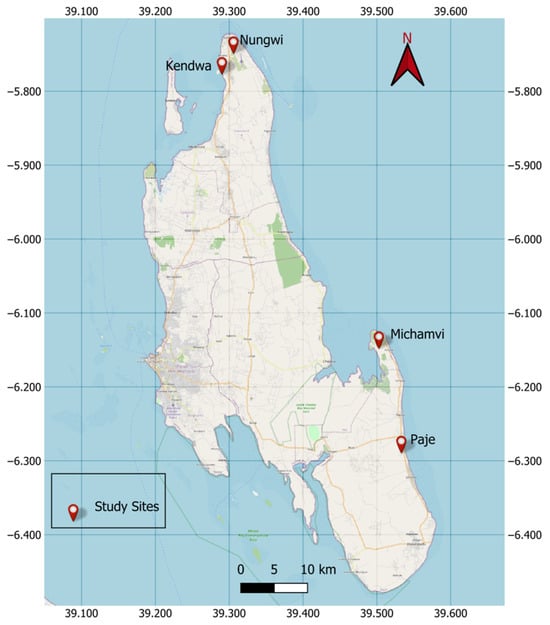

The study was conducted from October 2023 to March 2024 in the Northern and Southern coastal zones of Unguja Island, focusing on the major tourism hubs of Nungwi (−5.7262° S, 39.2929° E) and Kendwa (−5.7448° S, 39.2508° E) in the north, and Paje (−6.2659° S, 39.5227° E) and Michamvi (−6.1510° S, 39.4682° E) in the south (Figure 1). These areas were selected due to their high concentration of tourism establishments and the associated environmental pressures resulting from intensive development. The data collection period covered high (December–February), mid (October), and low (March) tourist seasons, enabling the assessment of seasonal fluctuations in hotel occupancy and the corresponding variation in waste generation. According to official records from the Zanzibar Commission for Tourism (unpublished report, ZCT, 2023) Zanzibar hosts 722 registered tourist accommodation facilities, of which 688 are located in Unguja and 34 in Pemba. Within Unguja, 535 facilities (77.8%) are concentrated in the North and South districts, including 355 rated hotels (1–5 star; 80% of all rated hotels) and 47 high-end hotels (4–5 star; 72.3% of all high-end hotels) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the hotels from which data was collected.

Table 1.

Distribution of Tourist Accommodation Facilities in Unguja’s Northern and Southern Districts.

2.2. Study Design

An exploratory descriptive research design was employed to assess solid waste generation and management practices in hotels, with each hotel serving as the unit of analysis. The design enabled both quantitative measurement of waste types and quantities and qualitative evaluation of existing management practices. This approach facilitated the identification of operational gaps and informed the development of evidence-based strategies aimed at enhancing waste reduction and promoting sustainable tourism operations.

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

To understand the current practices, challenges, motivations, and opportunities related to sustainable waste management in hotels, both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods were employed. This mixed-method approach provided a comprehensive understanding of waste management dynamics by integrating subjective perspectives from hotel management, staff, and local stakeholders with objective data on waste composition and volumes. Quantitative data were gathered through direct waste measurements to estimate the mass and types of waste generated. Qualitative insights were obtained from key informant interviews, direct observations of waste handling practices at selected hotels, participatory workshops capturing community perceptions, and document analysis identifying best-practice models for sustainable waste management (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data collection instruments used in the study.

2.4. Population and Sample

The study population comprised hotel managers and housekeeping staff directly involved in waste management functions, as well as other relevant stakeholders (refer to Section 2.6.4). Data on tourist accommodation units were obtained from the Zanzibar Commission for Tourism and served as the sampling frame. A list of 185 hotels located within the study area was compiled from the Commission’s registry of licensed hotels. From this list, ten (10) hotels that consented to participate were selected for both the quantitative waste audit and the qualitative assessment.

2.5. Analytical Framework

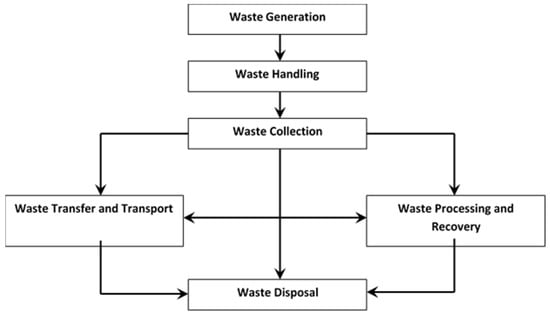

This study adopted a solid waste management (SWM) systems analysis framework that represents a simplified version of the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) model (Figure 2), specifically tailored for municipal solid waste management. The model was developed to facilitate analysis of the portion of the waste life cycle that includes generation, handling, collection, transfer, and transport. This framework was used to guide data collection, analysis, and the presentation of findings in this study.

Figure 2.

Solid waste management system model (Adapted from Alam & Ahmad [44]).

2.6. Data Collection Procedure

2.6.1. The Quantitative Data Collection Phase: Waste Quantification

Direct waste sampling was used to estimate the amount of waste generated at each hotel. The method involved direct examination of waste generation sources and characteristics such as weight and composition. Waste quantity was estimated using an electronic platform scale with a capacity of 150 kg, and the mass was recorded in kilograms to determine the daily generation rate, quantity, and composition of waste produced. For ease of measurement, plastic bins with a capacity of 150 L were used for sampling in each participating hotel. To avoid disrupting normal waste collection patterns, sampling followed existing collection schedules.

Waste estimation was conducted early in the morning before disposal, and the process was repeated for seven consecutive days for each sampled hotel. Solid waste samples collected on the first day were excluded to ensure that analyzed samples were not affected by accumulated waste from prior days. In hotels with irregular collection schedules, specific bins were designated to preserve waste for measurement prior to disposal.

To accurately measure each fraction of waste, data were collected from three main sources: restaurants and bars, kitchens, and housekeeping units. In hotels offering catering and bar services at the beach, an additional source was included to capture total waste generation. Source-based categorization enabled determination of waste composition by weighing each item within the solid waste stream. Details of each waste item were recorded, and the magnitude of solid waste generation was expressed in kilograms per source per day (kg/source/day).

The total weight of waste was also measured at each collection point within hotel premises to obtain overall estimates of waste generation per hotel per day, as well as per guest per day.

2.6.2. The Qualitative Data Collection Phase

In-depth interviews were conducted with hotel managers, staff, and key stakeholders, including district council personnel and representatives from the private sector involved in waste collection and management. Interview data were recorded either as audio files, with participants’ consent, or as field notes for those who declined recording. All audio recordings were transcribed, and both transcripts and field notes were coded using manual thematic analysis.

The interviews explored perceptions of waste management challenges, as well as the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders in waste handling and disposal. The qualitative data provided valuable insights into the social, economic, and cultural factors that shape and influence waste management practices in hotels.

2.6.3. Observation

An observation protocol was developed to assess waste management practices within the studied hotels. Non-participant observations were conducted using a predefined checklist to ensure consistency across different hotel settings. Observations focused on key waste handling points, including kitchens, disposal stations, and temporary storage areas. Each hotel was observed during three time slots—morning, midday, and evening, to capture variations in waste volumes and management practices throughout the day.

The protocol targeted key indicators such as waste sorting behavior, the availability and proper use of labeled bins, the frequency of waste removal, instances of bin overflow, and staff adherence to standard operating procedures. Observations were also extended to nearby villages to gain firsthand insights into the management of hotel-generated waste beyond the point of origin. As part of the process, researchers were guided on tours of each hotel by operations managers to better understand daily operational routines. These observations aimed to capture waste management behaviors, track waste handling processes, and validate self-reported practices through direct, contextual evidence.

2.6.4. Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted with various tourism stakeholders, including two officials from the District Councils responsible for SWM in the South and North districts, two officials from waste collection companies operating in the study area (ZANREC and Ham Garden), and ten hotel managerial staff, including general/operational managers, housekeeping staff, and/or personnel in charge of waste management from each hotel.

The purpose of the interviews was to explore current SWM practices, assess the engagement of relevant stakeholders, and identify the main barriers and opportunities for improvement, including the potential for circular or sustainable practices. Key informants were selected based on their official responsibilities and presumed insight into the study area and topic. Interviews were conducted in Kiswahili and English, depending on the interviewee’s language preference. Interviewees were contacted in advance to confirm their consent to participate. All collected information was compared with observational data to establish the validity of respondents’ reports.

2.7. Data Analysis

2.7.1. Analysis of the Quantitative Data

The quantitative data from waste measurements were analyzed using descriptive statistics to determine the quantity and composition of waste generated. The mean daily generation of waste for each studied hotel was calculated by averaging the daily totals collected over the seven-day period. Waste per guest per day was calculated by dividing the daily weight of waste for each hotel by the total number of guests. These statistics provided empirical evidence of the scope and types of waste generated in the selected hotels.

2.7.2. Analysis of the Qualitative Data

The qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis to gain contextual insights into stakeholders’ perceptions, challenges, and opportunities related to waste management practices in hotels. This approach ensured both depth and breadth of interpretation. The analysis process involved familiarization with the data, identification and refinement of themes, definition of their meanings, and production of a narrative account supported by illustrative quotes.

To synthesize both qualitative and quantitative data into actionable insights and recommendations for improving waste management practices, findings from all data sources were triangulated and compared across the different methods of data collection. This provided a comprehensive overview of the waste management situation within the hotel sector. The results were also compared with findings from peer-reviewed literature and organized in alignment with the Solid Waste Management (SWM) systems framework (Figure 2). The integration of multiple data collection methods enabled the identification of key gaps, opportunities, and practical considerations for implementing a circular economy framework tailored to the hotel sector.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Hotels

The studied hotels varied in classification, ownership, and size, factors that may influence their waste management practices. Among the ten (10) hotels, 30% were rated as 3-star, 40% as 4-star, and 30% as 5-star establishments. Sixty percent (60%) were members of the Zanzibar Association for Tourism Investors (ZATI), and ownership was evenly divided between local (50%) and foreign (50%) investors. In terms of size, 40% had between 1 and 30 rooms, while 60% had 31 or more rooms, indicating a predominance of mid- to large-sized hotels (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hotel characteristics.

3.2. Generation Waste Generation in the Studied Hotels

The analysis of solid waste generation in the surveyed hotels (Table 4) reveals a clear distinction between absolute waste volume and waste intensity. Total daily waste varied widely, from 380.48 kg/day in the five-star H2 to 42.9 kg/day in the three-star H9—reflecting differences in hotel size and occupancy levels. However, Mean Per Capita (MPC) values were confined to a narrow. range of 1.65–3.34 kg/guest/day, indicating that intensity is not driven by category or capacity.

Table 4.

Waste generation in the studied hotels.

This pattern underscores that internal management and operational practices, rather than star-rating or physical scale, are the main determinants of per-guest waste output. For example, high-rated establishments such as the five-star H3 (1.96 kg/guest/day) and the four-star H4 (2.08 kg/guest/day) reported lower MPC values than some lower-rated hotels including the four-star H8 (2.80 kg/guest/day) and the three-star H7 (2.13 kg/guest/day). This separation between waste intensity and formal rating criteria highlights the important role of management commitment, service design, and efficiency in reducing waste generation per guest.

Despite the internal variation across facilities, the overall mean MPC of 2.45 kg/guest/day for Zanzibar’s coastal hotels falls within the moderate global range for tropical tourist destinations. It also closely aligns with comparable benchmark values, such as 2.28 kg/guest/day reported for Hoi An, Vietnam. This suggests a general convergence in per capita waste outputs across tourism-intensive coastal settings globally, even when the drivers of that waste volume are locally unique.

To further understand waste generation patterns, the composition of solid waste was analyzed across all hotel categories, providing insights into the dominant waste fractions and their potential management implications.

3.3. Quantity and Composition of Solid Waste Generation in the Selected Tourist Hotels of Zanzibar

The composition analysis of solid waste generated in the surveyed hotels revealed that food waste was the dominant component, followed by mixed waste and plastic (Table 5). The total daily waste generated across all hotels was 1762 kg day−1, per hotel. Food waste accounted for the largest fraction, representing 72% of the total weight. Mixed waste contributed 26.5%, while plastic waste accounted for 1.62%. The plastic waste measured consisted of water bottles only; the total plastic waste was likely higher than recorded due to the reusable nature of PET bottles, as some were often taken away before auditing.

Table 5.

The quantity and composition of solid waste generated in the selected tourist hotels of Zanzibar, measured in kilograms.

These measurements were based on weight; however, assessing waste in terms of CO2 emissions could provide additional insights into its environmental impact. Using emission factors from Di Paolo et al. (2022) [45], plastic waste emits approximately 5.5 times more CO2 per kilogram than food waste. Although food waste constitutes about 72% of the total weight and accounts for roughly 68% of total emissions, plastic waste, despite comprising only around 1.6% by weight, contributes nearly 9.4% of total emissions. This disproportionate carbon intensity underscores the urgent need to address plastic pollution alongside food waste reduction efforts.

A significant contributor to this plastic footprint is bottled water consumption by tourists. According to [46], tourists in Zanzibar use an estimated two 1.5 L plastic bottles per day. With 691 guests present during the study, this translates to approximately 1382 bottles daily, weighing about 34.55 kg and comprising 2% of the total waste, excluding other plastic items. However, due to tracking challenges, many bottles were removed from hotels before measurement, suggesting that the reported figures likely underestimate the actual scale of plastic waste.

In addition to beverage bottles, other plastic items, such as food wrappers, single-use packaging, toiletry containers, and disposable utensils, also contribute significantly to the overall plastic waste stream in hotels. While these items were not all quantified in this study, their presence was consistently observed during waste audits and site visits, indicating that the actual share and associated emissions of plastic waste are considerably higher than the reported figures suggest.

3.4. Waste Prevention and Reduction

Waste management practices among the studied hotels varied considerably, influenced by factors such as waste collection services, managers’ environmental awareness, and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Hotels collaborating with ZANREC demonstrated better practices due to the company’s strict requirements for waste separation and collection, unlike its counterpart, Ham Garden, which lacked structured guidelines.

Despite a gradual shift towards a circular economy, waste management in Zanzibar’s hotel sector remains inadequate. A major concern is that 70% of hotel staff do not perceive waste management as part of their responsibilities, reflecting gaps in environmental awareness and limited engagement in sustainable practices. As one housekeeping staff member stated, “We are aware that waste needs to be handled in a much better way than now, and we’d love to help, but our plates are full. So, we do it in the simplest way possible” (Housekeeping staff, female, 30).

This issue is linked to a lack of training, with 80% of employees reporting that they were only trained during job orientation. One steward emphasized the need for improvement: “There is a need for better training, resources, and a stronger commitment to sustainable waste management in Zanzibar’s growing hotel industry. Right now, it’s just talk with no real action” (Steward, male, 25).

3.5. Waste Sorting and Handling

All the studied hotels separated food waste from other waste fractions. Two hotels (20%) out of ten had contracts with recycling or up-cycling firms, which provided special bins for plastic and glass bottles. However, proper waste sorting was uncommon, as many hotel managers did not recognize its necessity within the existing waste collection system. Even when waste was sorted at the source, waste collectors frequently mixed the separated fractions during transport, rendering in-hotel segregation efforts largely ineffective.

As one manager explained, “We always try our best to sort the waste, but once the collectors pick it up, they mix it all together again. It’s frustrating because it makes our efforts feel pointless” (Facility manager, male, 47). Through direct field observations, the research team repeatedly witnessed this practice across several hotel sites and at different stages of waste collection, confirming that it is not an isolated or incidental event but a recurring pattern.

Such inconsistencies between in-hotel sorting and off-site handling not only undermine staff motivation to maintain segregation practices but also indicate weak coordination between hotels and waste collection service providers. These findings underscore the need for stronger operational oversight and harmonized waste management practices throughout the entire collection chain.

3.6. Collection, Transfer, and Transport

The District Council is responsible for waste collection at hotels and local communities but has outsourced these services to private companies due to resource constraints. Hotels must contract one of the pre-approved private waste companies. Hotel managers had mixed opinions on the quality of waste collection services, with some satisfied and others expressing concerns about how waste is handled beyond their premises. One of the managers commented, “We are happy with the service provided, but we do not have the authority to intervene in what is happening beyond our gates.” (GM, female, 60).

In contrast, another manager expressed frustration, “I don’t really understand what is happening. I have already written to the district to return our former collectors, as they understand our values and principles-this is confusing.” (Facility manager, 38).

Adding to the concerns, a general manager stated, “We pay regularly for the waste collection service, but surprisingly, some of the services provided are not at all at an acceptable level.” (GM, male, 40).

Interviews with waste contractors revealed dissatisfaction with how the District Council awarded contracts. Some companies faced unforeseen changes in contract terms without notice. There was also a lack of uniformity in service provision due to inadequate technical and entrepreneurial skills among some contracted waste providers. One contractor expressed frustration, saying, “We agreed on certain terms, but then the rules changed without warning. How can we provide reliable service when the goalposts keep moving?” (Male, 30, In-charge, waste collection company).

Despite some hotels making efforts to manage waste sustainably, only a few (20%) practiced waste sorting. However, these efforts were often undermined by waste collectors who mixed the sorted waste into a single truck, rendering the sorting ineffective. One manager voiced their concern stating, “District councils are not doing enough to make sure the waste companies follow sustainable practices in managing waste. If you happen to see how some of the approved companies handle and dispose of the waste, you won’t believe it.” (GM, male 45).

3.7. Waste Recovery

Most hotels (90%) reported limited engagement in waste handling and recovery. Hotels were required to use district-approved waste collection services, but it was unclear if these companies were selected based on their waste handling and recovery capabilities. Only two hotels have adopted proactive waste prevention and reduction measures, such as small-scale composting, green purchasing, and partnering with local recyclers to recover plastic and glass bottles.

Despite the potential for recycling in Zanzibar, hotels were hesitant due to concerns about market demand for recycled products and the lack of incentives for waste prevention. Some managers noted that waste collection fees were fixed based on occupancy, meaning waste reduction efforts had no financial impact. As noted by one informant “We understand that recycling is a business which can add to financial gain, we can buy a machine to shred the plastic, but I doubt if there is a market for the end product” (GM, male, 47) Another informant had this to say “Waste companies charge a fixed rate for waste collections based on the maximum occupancy level, so waste prevention in this context does not make much sense to us as regardless of the efforts we take to minimize waste it has no impact on the fees payable to the municipality” (General manager., male 55). According to ZANREC, recycling is a viable business in Zanzibar and there are end-market purchasers interested in purchasing recycled waste materials, such as plastic and glass (Personal communication, ZANREC, 2023).

3.8. Disposal

Due to the lack of formal waste processing and recovery, a substantial amount of unsegregated waste from hotels is disposed of at Kibele landfill, and other designated sites within the study area. However, observations and interviews have revealed that due to the long distance between hotels and official landfill sites, particularly in the southern region, small hotels and informal local waste collectors often resort to open dumping as a more convenient option. This practice has contributed to the proliferation of informal dumpsites near communities, leading to environmental degradation, public health risks, and negative perceptions among tourists.

3.9. Motivations and Barriers for Proper Waste Management Practices in the Studied Hotels

Findings from interviews, observations, and document analysis revealed a mix of motivating factors and barriers affecting waste management practices in the studied hotels. While hotel managers cited environmental responsibility and cost-saving incentives as drivers for adopting improved practices, several systemic and operational challenges hindered progress. As summarized in Table 6, the most prominent barriers included a lack of employee awareness, where 70% of the interviewed staff did not perceive waste management as part of their duties, and the absence of structured sorting and recycling systems across most hotels.

Table 6.

Key barriers to sustainable waste management among hotels.

Additionally, difficulties in sourcing eco-friendly alternatives due to limited supplier options, coupled with weak institutional support, characterized by slow regulatory enforcement and unclear responsibilities, further impeded sustainable efforts. Inefficient pricing models, which base waste fees on hotel size rather than volume or practices, were also found to discourage waste minimization initiatives. These challenges were reflected in the perspectives of hotel staff and managers. As one hotel manager noted: “Sometimes we want to switch to eco-friendly products, but the suppliers just aren’t there, or they’re too expensive. Even when we try, there’s no real support or follow-up from authorities. And the way we’re charged for waste based on the size of our hotel, not how we manage our waste, makes it feel like efforts to reduce waste don’t really count (GM, male 48)”.

Despite the existing barriers, observations at the Kibele dumpsite revealed ongoing informal recycling efforts, yet waste collectors face restricted access, limiting broader participation in waste recovery. Concerns around operational limits and health risks were common among those working directly in waste collection. For example, one recycler shared: “There are a lot of recyclables at Kibele, but we are denied access to collection (Recycler, Female, 24)” In response, a site official explained, “We wish we could accommodate everyone, but taking a larger group is risky and unhealthy.” (Male, 34), This restricted access highlights a potential for more recycling in the sector.

As mentioned, food waste was found to be the most dominant waste type in hotels, comprising approximately 72% of total waste generated. This presents a significant opportunity for composting initiatives, which could transform waste into valuable organic fertilizer. However, findings indicate that the absence of technical support, clear municipal policies, and structured integration into existing waste management systems prevents large-scale implementation of composting practices.

Despite challenges, hoteliers demonstrated a strong willingness to adopt improved waste management practices. However, interviews revealed that gaps in infrastructure, regulatory guidance and incentives continue to hinder progress.

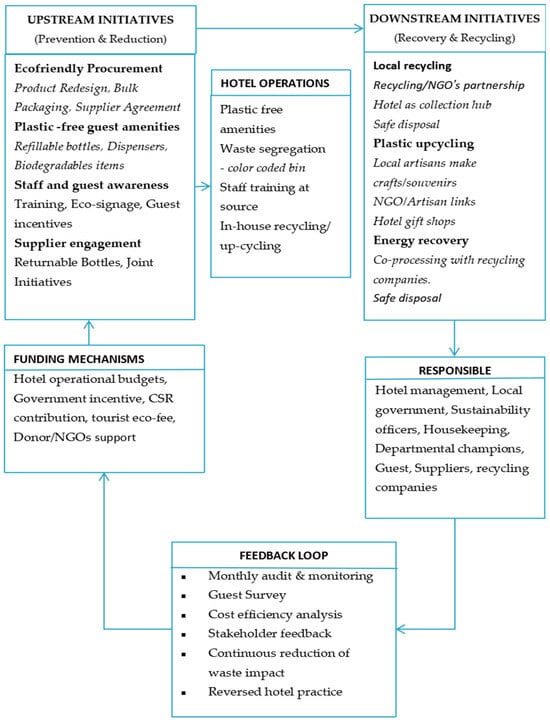

Building on the findings from hotel waste audits and stakeholder interviews, this study proposes a Circular Economy Framework for Plastic Waste Management in Zanzibar’s Coastal Hotels (Figure 3). The framework responds to the identified challenges of high single-use plastic consumption, weak segregation practices, and limited recycling infrastructure, while also aligning with opportunities for prevention, reuse, and value recovery. It organizes interventions across upstream initiatives, hotel operations, and downstream initiatives, supported by funding mechanisms, responsible personnel, and a feedback loop for continuous improvement.

Figure 3.

Circular economy framework for plastic waste management in Zanzibar hotels.

3.10. Framework Description

This framework presents a circular economy approach for managing plastic waste in coastal hotels. Instead of focusing only on disposal, it emphasizes a system where resources are reduced, reused, and recycled in continuous cycles. Hotels are placed at the center, not only as users of plastic products but also as active players in driving change.

- Upstream Actions (Prevention at the Source)

Hotels work with suppliers to choose eco-friendly and reusable products. Procurement is redesigned so that purchasing decisions reduce single-use plastics from the start.

- 2.

- Hotel Operations (Core of the Framework)

Hotels adopt practices like refillable amenities, reusable bottles, and packaging alternatives. Guests are encouraged to take part through awareness campaigns and incentives.

- 3.

- Downstream Actions (Managing Waste After Use)

Waste is sorted properly so plastics can be recycled or repurposed instead of ending up in landfills or the ocean. Hotels partner with local recyclers and communities to recover value from plastic waste.

- 4.

- System Flows (Continuous Cycles)

The arrows in the framework show that this is not a one-way process. Hotels learn, adapt, and improve based on monitoring and feedback. Information from hotels can also support better policies and regulations for sustainable tourism. This is about re-imagining hotels as places that do more than provide hospitality; they also protect the environment, involve guests, support communities, and help build a future where tourism and sustainability go hand in hand. This framework positions hotels as places that do more than provide hospitality; they also protect the environment, involve guests, support communities, and help build a future where tourism and sustainability go hand in hand.

4. Discussion

Tourism continues to be a major economic driver in Zanzibar, but its rapid growth has led to rising levels of solid waste, particularly plastic and other non-biodegradable materials. This increase has outpaced the island’s waste management capacity, resulting in excessive littering and a rise in informal dumpsites around communities, which pose environmental hazards and public nuisances. Open dumping remains the primary disposal method, harming ecosystems, local communities, and the overall visitor experience, clearly reflecting weak enforcement and inadequate infrastructure. These conditions expose deeper structural deficiencies, including the absence of mandatory waste separation, inadequate recycling systems, and a lack of integrated sustainability policies [20,23,24]. These challenges are not merely operational but symptomatic of broader governance and institutional gaps. If left unaddressed, they risk degrading the very natural and cultural assets upon which Zanzibar’s tourism economy depends. Therefore, tackling these systemic weaknesses is not only an environmental necessity but also a strategic imperative for safeguarding the long-term viability and global competitiveness of Zanzibar’s tourism sector.

4.1. Comparative Insights from Existing Studies

Our findings resonate strongly with recent studies in comparable island tourism contexts, further validating the structural and operational challenges identified in Zanzibar. Comparative studies provide valuable context. In Gili Trawangan, Indonesia, Ref. [47] identified weak stakeholder governance, fragmented collaboration between hotels and waste contractors, and the absence of sustainable policy frameworks, challenges that closely mirror the situation in Zanzibar. Similarly, Ref. [48] observed in Bali that rapid resort expansion, widespread use of non-biodegradable packaging, and limited governmental oversight resulted in illegal dumping and overburdened waste systems, drawing direct parallels to Zanzibar’s unmanaged single-use plastic problem.

Further comparable studies can be seen in Langkawi Island, Malaysia, where Ref. [49] reported poor hotel waste policies, limited sorting infrastructure, and low staff awareness. These findings reflect the management inaction and capacity gaps identified in this study. Likewise, recent data from Zanzibar show that food waste averages 1.8 kg per guest per day, attributed to weak waste management planning and poor coordination among hotel staff and service providers [25]. Taken together, these studies reinforce that the issues in Zanzibar are not isolated but are part of a broader pattern observed across island tourism destinations in several parts of the world: policy inertia, fragmented service arrangements, lack of managerial engagement, and insufficient staff training.

The key distinction lies in the underlying factors. While Hoi An’s waste volume correlates strongly with the hotel’s scale and amenities, such as capacity, room pricing, and dining options [39], evidence indicates that in African contexts like Zanzibar, waste intensity is more influenced by management commitment and operational practices than by formal star ratings alone [25]. Studies in Zanzibar show that hotels with dedicated waste management teams, staff training programs, and proactive operational strategies exhibit better waste reduction outcomes, regardless of their official star classification [50]. This suggests that effective management practices can outweigh structural factors like size or rating in determining hotel waste intensity.

Addressing these challenges requires integrated governance frameworks, enforceable environmental policies, improved collaboration between hotels, local communities, and waste management contractors, and capacity-building initiatives targeting hotel staff. Without such coordinated action, the environmental pressures tied to tourism in Zanzibar and similar destinations will likely continue to escalate.

4.2. Missed Opportunities: Limitations of Local Innovation

Despite institutional weaknesses, local innovations in waste management are beginning to emerge. Hotel- and community-led initiatives, including informal sorting, grassroots recycling, and partnerships with waste collectors, demonstrate potential [43]. Yet these remain isolated and largely unsupported [43], without government facilitation, such initiatives are unlikely to reach scale or permanence. This study suggests that what appears as community-level inertia may actually reflect a lack of structural support and enabling policies. This study suggests that what may appear as limited local engagement in addressing solid waste is, in fact, a reflection of limited structural support and the absence of enabling policies. In the context of Zanzibar, the informal nature of many tourism-linked businesses and the lack of financial incentives for waste reduction contribute to poor engagement in sustainable practices. Waste management is often viewed as a municipal responsibility, while hotels and private operators are rarely integrated into financing or co-management frameworks. As such, policy instruments such as targeted tax relief, business classification schemes that reward sustainable performance, and exemption models for enterprises investing in green technologies could encourage greater private sector involvement. Additionally, expanding access to seed grants, concessional loans, and capacity-building programs, particularly for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) could accelerate the adoption of waste-reducing technologies and scalable circular solutions. Without such systemic interventions, efforts to improve waste outcomes at the local level are likely to remain fragmented and under-resourced.

4.3. The Promise of Circular Economy and Incentive-Based Models

The findings of this study reveal that waste management in Zanzibar’s hotels is constrained by limited infrastructure, weak enforcement, and a heavy reliance on single-use plastics, yet the sector also presents clear opportunities for circular interventions. Hotels generate a relatively consistent and traceable waste stream, making them well-positioned to implement measures such as food waste composting, plastic recovery, and collaboration with local recyclers. The prominence of single-use plastics waste fraction underscores the urgency of targeted reduction strategies. Circular economy instruments, such as Extended Producer Responsibility, deposit-return schemes, and pay-for-bin models have demonstrated success in comparable island contexts and could be adapted to Zanzibar, where rapid tourism growth has intensified the waste challenge and left much of municipal waste unmanaged. The government’s recent move to mandate compliance for tourist establishments in 2025 presents a timely opportunity to integrate such measures into Zanzibar’s waste governance. Harnessing these tools would not only reduce environmental leakage and financial burdens on public systems but also foster private sector participation, green job creation, and resource efficiency positioning the tourism sector as a driver of circular and climate-resilient development.

4.4. Real-World Relevance: What’s at Stake

Inadequate waste management in Zanzibar has far-reaching environmental consequences. Plastic pollution not only threatens marine ecosystems, local food chains, and livelihoods dependent on fisheries and tourism, but also results in the inefficient use of valuable resources [23,24]. This underscores the practical urgency of the findings: systemic inaction poses not only ecological but also socioeconomic risks, including the loss of valuable materials and energy embedded in waste. Sustainable tourism in Zanzibar cannot thrive without implementing effective waste management strategies that promote recycling, resource recovery, and a circular economy. Systemic inaction which manifested itself through inadequate infrastructure, weak policy enforcement, and fragmented coordination has led to succession of environmental, economic, and public health risks in Zanzibar. Conversely, the success of the 1 July 2025 directive mandating all hotels to adopt sustainable waste management practices will depend not only on regulation, but also on the effective training of stakeholders and the scaling of circular economy initiatives. Only through this integrated approach can Zanzibar advance ecological resilience and achieve truly sustainable tourism growth.

5. Conclusions, and Future Directions

This study provides an in-depth analysis of waste management practices in ten tourist hotels along Zanzibar’s northern and southern coasts. The findings show that hotels produce large amounts of mixed waste, yet their main approach remains limited to collection and disposal. Few efforts are made to reduce, reuse, or recycle. With district councils lacking capacity, private waste companies are tasked with transporting hotel waste to landfill sites. However, this solution is insufficient for the scale of the problem. Alarmingly, 80% of hotels do not take advantage of opportunities to convert waste into valuable resources, despite organic waste making up about 72% of the total waste generated. This reflects a major missed opportunity for resource recovery and calls for a shift in perspective, where waste is seen not as a burden, but as a potential economic asset. To overcome these challenges, hotel managers and policymakers must adopt a new mindset that values sustainable waste practices.

Stronger institutional support, better collaboration, and targeted capacity building are essential. Organizations like the Zanzibar Hotels Association, along with regulatory agencies such as ZEMA and ZCT, should play a leading role. Circular economy strategies, such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes, public–private partnerships, and regular staff training, can help improve sustainability across the sector.

Recent policy initiatives, including the July, 1st directive and the Greener Zanzibar campaign, provide a timely opportunity to embed sustainability into tourism regulations. Strengthening waste governance will also require multi-sectoral collaboration, better data collection, and the introduction of financial incentives, such as Pay As You Throw (PAYT) schemes. By adopting data-driven and circular economy strategies, Zanzibar can significantly reduce the environmental impacts of tourism and fulfill its mission of promoting sustainable and responsible development in its tourism sector.

6. Implications for Policy and Practice

In light of these findings, it is evident that Zanzibar’s waste governance is fragmented, with poor stakeholder coordination, weak institutional alignment, and limited community engagement, all of which undermine efforts to manage the environmental strain caused by tourism. While national policies, such as the Zanzibar Environmental Policy (2013), and the 2019 Solid Waste Management Strategy (unpublished) advocate for public–private partnerships and community participation, implementation remains siloed and inconsistent. Addressing this requires dismantling operational silos through a formal collaborative platform that aligns policies, institutions (municipalities, district councils tourism, NGOs), and grassroots actors like youth innovators and informal waste collectors. By embedding hotels and tour operators into governance structures, co-developing circular waste systems (e.g., food composting, plastic recycling, etc.), and institutionalizing shared responsibility with proper funding and monitoring, Zanzibar can move toward an integrated, sustainable and circular waste management approach. Implementing a circular economy model within governance structures ensures that waste is not only managed but transformed into valuable resources, supporting both environmental resilience and community well-being.

7. Limitations & Delimitations

Although this study fills an important gap in the literature, several limitations warrant consideration. The waste audit was conducted in only ten hotels; however, it was complemented by qualitative data and repeated over seven consecutive days for each hotel to account for guest fluctuations and temporal variations, thereby enhancing the credibility and depth of the findings. While waste measurement covered the entire waste stream, the estimation of the plastic waste fraction focused primarily on beverage-containing polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles. This focus was chosen because PET is the most commonly used plastic in the food and beverage sector and represents a significant proportion of plastic litter. As such, the findings do not capture the full spectrum of plastic waste types but reflect a substantial and impactful waste stream. The qualitative component was based on purposely selected key informants, which means the results may not be generalisable to all hotels. Nonetheless, this enabled the study to generate rich, contextualized insights into real-world practices, challenges, and opportunities for improvement within the selected establishments in Zanzibar. These findings are also relevant to other coastal tourism destinations with similar settings, where the hospitality sector faces comparable pressures to balance economic growth with sustainable waste management.

Recommendation for Future Research:

Future work should pursue a comprehensive comparative and temporal (seasonal) study to develop robust waste management policies for Zanzibar’s tourism sector. This systematic analysis must integrate three critical dimensions: (1) a detailed quantification of environmental indicators, specifically the carbon footprint and marine pollution risk from tourism-related waste; (2) a social and behavioral perspective on the waste habits and perceptions of both guests and staff, identifying key leverage points for behavioral change and policy intervention; and (3) bench-marking against international standards to provide a clear blueprint for transitioning Zanzibar’s current ad hoc system to a formal, policy-reinforced, and environmentally sustainable waste management framework capable of mitigating seasonal pollution peaks.

Author Contributions

Conceived, A.A.; designed the study, A.A.; collected data in the field, A.A. and B.A.; analyzed the data, A.A.; wrote the original manuscript, A.A.; conceptualized the study, B.A.; reviewed, F.S., A.R. and S.H.; edited, F.S., A.R. and S.H.; supervised, F.S., A.R. and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was part of a PhD project funded by Danida, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, through the Building Stronger Universities Phase 3 project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained on 11 November 2019 from the Zanzibar Health Research Institute (ZAHRI) through its Zanzibar Health Research Ethics Committee (ZAHREC), under the project titled “Building Stronger Universities Project (BSU3)”. (Approval Number: ZAHREC/03/PR/NOV/2019/003; project Identification Code: SUZA-BSU3).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents were informed about the purpose of the study, their right to withdraw at any time, and the confidentiality of the information provided.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this work has been reported in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The researcher would like to express sincere gratitude to all the participants and stakeholders who contributed to this research study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| EPR | Extended Producer Responsibility |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| SWM | Solid Waste Management |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| ZANREC | Zanzibar Recycling Company |

| ZAHRI | Zanzibar Health Research Institute |

| ZEMA | Zanzibar Environmental Management Authority |

References

- UNEP. UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Global Travel & Tourism Catapults into 2023. 2023. Available online: https://wttc.org (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Abubakar, I.R.; Maniruzzaman, K.M.; Dano, U.L.; AlShihri, F.S.; AlShammari, M.S.; Ahmed, S.M.S.; Al-Gehlani, W.A.G. Environmental sustainability impacts of solid waste management practices in the Global South. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y. Municipal solid waste management challenges in developing regions: A comprehensive review and future perspectives for Asia and Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koliotasi, A.S.; Abeliotis, K.; Tsartas, P.G. Understanding the Impact of Waste Management on a Destination’s Image: A Stakeholders’ Perspective. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 4, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.M.; Cró, S. The Impact of Tourism on Solid Waste Generation and Management Cost in Madeira Island for the Period 1996–2018. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Farina, E.; Díaz-Hernández, J.J.; Padrón-Fumero, N. Analysis of hospitality waste generation: Impacts of services and mitigation strategies. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2023, 4, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Grün, B.; Dolnicar, S. Waste production patterns in hotels and restaurants: An intra-sectoral segmentation approach. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2023, 4, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu-Sbert, J.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Villalonga-Olives, E.; Cabeza-Irigoyen, E. The impact of tourism on municipal solid waste generation: The case of Menorca Island (Spain). Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 2589–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, M.A.; Wee, S. Municipal solid waste management in Malaysia: An insight towards sustainability. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanzibar Commission for Tourism. Zanzibar Tourism Statistical Release: Annual Report; Zanzibar Commission for Tourism: Zanzibar, Tanzania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Chief Government Statistician. Tourism Statistical Abstract 2022/2023; Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar: Zanzibar, Tanzania, 2023.

- Zanzibar Commission for Tourism. Tourism Performance Highlights: January; Zanzibar Commission for Tourism: Zanzibar, Tanzania, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, G.M. Tourism in Zanzibar: Incentives for sustainable management of the coastal environment. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 11, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Down to Earth. In Hope of a Plastic Waste-Free Island; Down to Earth: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/waste/in-hope-of-a-plastic-waste-free-island-61973 (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Hannah, R.; Veronika, S.; Max, R. Plastic Pollution. 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- UN Environment Programme. Everything You Need to Know About Plastic Pollution. 2023. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/everything-you-need-know-about-plastic-pollution (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- McIlgorm, A.; Xie, J. The Costs of Environmental Degradation from Plastic Pollution in Selected Coastal Areas in the United Republic of Tanzania (Report No. AUS0003181); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Marcharla, E.; Vinayagam, S.; Gnanasekaran, L.; Soto-Moscoso, M.; Chen, W.H.; Thanigaivel, S.; Ganesan, S. Microplastics in marine ecosystems: A comprehensive review of biological and ecological implications and its mitigation approach using nanotechnology for the sustainable environment. Environ. Res. 2024, 256, 119181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rellán, A.G.; Ares, D.V.; Brea, C.V.; López, A.F.; Bugallo, P.M.B. Sources, sinks and transformations of plastics in our oceans: Review, management strategies and modelling. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Bank. Extended Producer Responsibility: For Advancing Circular Economies for Plastics in Bangladesh; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099121624201515863/pdf/P1759081d4a8d30e81899a1c0b8bfb342ad.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Maione, C. Quantifying plastics waste accumulations on coastal tourism sites in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakar, A.N.; Mohammed, M.S.; Ussi, A.M.; Mnemba, S.S.; Tairova, Z.M. Assessment of Marine Environmental Litter Present in Zanzibar (Unguja) Beaches. Int. J. Acad. Appl. Res. (IJAAR) 2024, 8, 42–47. Available online: https://www.ijeais.org/ijaar (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Ally, B.; Abdulkadir, A.; Remmen, A.; Hirsbak, S.; Mwevura, H.; Furu, P.; Salukele, F. Food Waste Management at Selected Tourist Hotels in Zanzibar: Current Practices and Challenges in Creating a Circular Economy in the Hospitality Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, I. Waste Management Practices of Small Hotels in Accra: An Application of the Waste Management Hierarchy Model. J. Glob. Bus. Insights 2020, 5, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitole, F.A.; Ojo, T.O.; Emenike, C.U.; Khumalo, N.Z.; Elhindi, K.M.; Kassem, H.S. The impact of poor waste management on public health initiatives in shanty towns in Tanzania. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awino, F.B.; Apitz, S.E. Solid waste management in the context of the waste hierarchy and circular economy frameworks: An international critical review. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024, 20, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyampundu, K.; Mwegoha, W.J.; Millanzi, W.C. Sustainable solid waste management Measures in Tanzania: An exploratory descriptive case study among vendors at Majengo market in Dodoma City. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Trends in Solid Waste Management. In What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. 2018. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/trends_in_solid_waste_management.html (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Ferronato, N.; Torretta, V. Waste Mismanagement in Developing Countries: A Review of Global Issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Bridging the Gap in Solid Waste Management: Governance Requirements for Results. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/publication/bridging-the-gap-in-solid-waste-management (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Kinemo, S. Local Government Capacity for Solid Waste Collection in Local Markets in Tanzania. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2019, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, F.C.; Gündoğdu, S.; Markley, L.A.; Olivelli, A.; Khan, F.R.; Gwinnett, C.; Gutberlet, J.; Reyna-Bensusan, N.; Llanquileo-Melgarejo, P.; Meidiana, C.; et al. Plastic Pollution, Waste Management Issues, and Circular Economy Opportunities in Rural Communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, E.; Barbir, J.; Mersico, L.; Stasiskiene, Z. Tourism intensity and plastic waste management: Insights from European capital cities. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrekidan, T.K.; Weldemariam, N.G.; Hidru, H.D.; Gebremedhin, G.G.; Weldemariam, A.K. Impact of improper municipal solid waste management on fostering One Health approach in Ethiopia-Challenges and opportunities: A systematic review. Sci. One Health 2024, 3, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystosik, A.; Njoroge, G.; Odhiambo, L.; Forsyth, J.E.; Mutuku, F.; LaBeaud, A.D. Solid wastes provide breeding sites, burrows, and food for biological disease vectors, and urban zoonotic reservoirs: A call to action for solutions-based research. Front. Public Health 2020, 7, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadhullah, W.; Imran, N.I.N.; Ismail, S.N.S.; Jaafar, M.H.; Abdullah, H. Household solid waste management practices and perceptions among residents in the East Coast of Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham Phu, S.T.; Fujiwara, T.; Hoang Minh, G.; Pham Van, D. Solid waste management practice in a tourism destination—The status and challenges: A case study in Hoi An City, Vietnam. Waste Manag. Res. 2019, 37, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Dangi, M.B.; Cohen, R.R.H.; Dangi, S.J.; Rijal, S.; Neupane, M.; Ashooh, S. Solid waste management in rural touristic areas in the Himalaya: A case of Ghandruk, Nepal. Habitat Int. 2024, 143, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, S.I.; Arafat, H.A. Solid waste management in the hospitality industry: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayshal, M.A. Current practices of plastic waste management, environmental impacts, and potential alternatives for reducing pollution and improving management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukali, I. Enhancing Circular Economy and Waste Management in Zanzibar by Leveraging Young Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Master’s Thesis, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, 2023. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1769359/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Obersteiner, G.; Gollnow, S.; Eriksson, M. Carbon footprint reduction potential of waste management strategies in tourism. Environ. Dev. 2021, 39, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, L.; Abbate, S.; Celani, E.; Di Battista, D.; Candeloro, G. Carbon footprint of single-use plastic items and their substitution. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konradsen, F. Sustainable Tourism—Promoting Environmental Public Health: Solid Waste Management on Zanzibar [Video]. 2010. Available online: https://oer.ku.dk/media/t/0_91sxcs5x (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Willmott, L. Solid Waste Management in Small Island Destinations: A Case Study of Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. Téoros Rev. Rech. 2012, 1, 71–76. Available online: https://teoros.revues.org/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Koski-Karell, N.S. Integrated sustainable waste management in tourism markets: The case of Bali. Indian J. Public Adm. 2019, 65, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasavan, S.; Mohamed, A.F.; Abdul Halim, S. Drivers of food waste generation: Case study of island-based hotels in Langkawi, Malaysia. Waste Manag. 2019, 91, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachage, B.; Yohana, L.; Mohamed, M.; Budeanu, A.; Furu, P. Influence of Resources and Training on Solid Waste Management Practices at Hotels in Zanzibar. East Afr. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2024, 4, 11–23. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/eajmbs/article/view/284525 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).