Social Economy Organizations as Catalysts of the Green Transition: Evidence from Circular Economy, Decarbonization, and Short Food Supply Chains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. Social Economy

2.2. Circular Economy as a New Avenue for Greener Social Economy

2.3. Decarbonization as a New Avenue for Greener Social Economy

2.4. Short Food Supply Chains as a New Avenue for Greener Social Economy

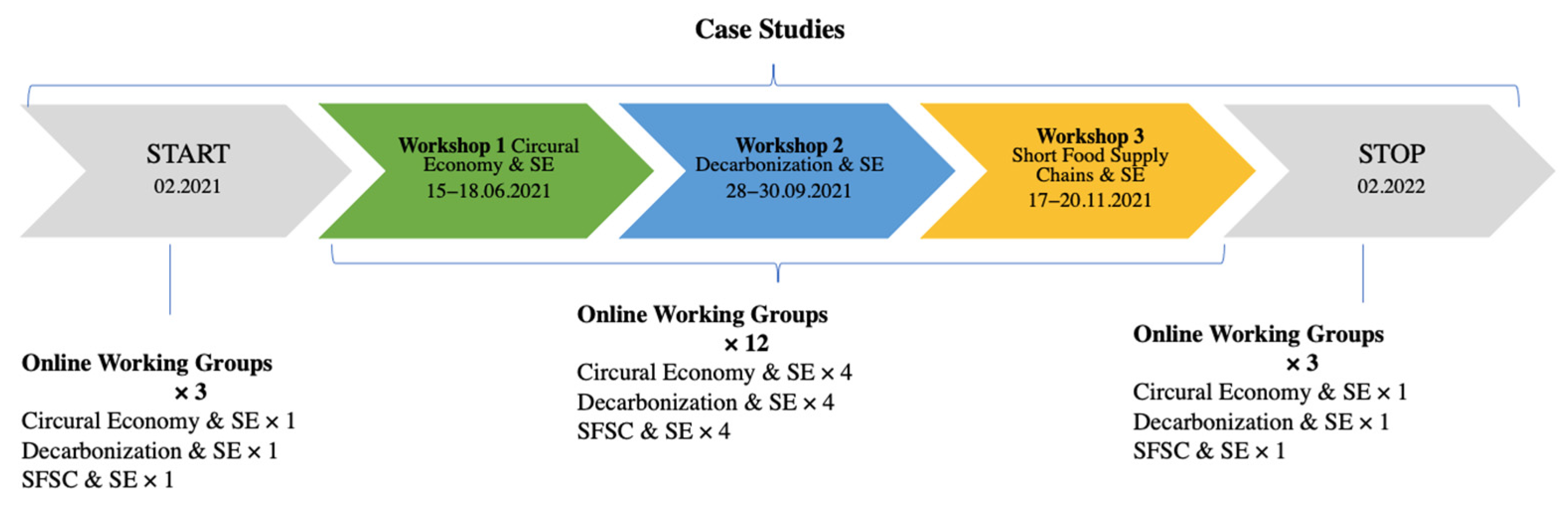

3. Methods

In what ways do social economy organizations contribute to the integration of circular economy principles, decarbonization efforts, and the development of short food supply chains (SFSCs), and what are the key social and environmental outcomes of these initiatives?

4. Results

4.1. Short Food Supply Chain

4.1.1. Banyaerdő, Hungary

4.1.2. Kockacsoki, Hungary

4.1.3. Centro Social De Bairro, Portugal

4.1.4. Il Sole E La Terra, Italy

4.1.5. La Porta Del Parco, Italy

4.1.6. I Raìs, Italy

4.1.7. Meal Delivery, Poland

4.2. Circular Economy

4.2.1. Municipal Furniture Bank, Portugal

4.2.2. Silesian Exchange Group, Poland

4.2.3. La Miniera, Italy

4.2.4. Groupe Terre, Belgium

4.3. Decarbonization

4.3.1. Smart Building Automation System, Portugal

4.3.2. Green Office, Poland

4.3.3. Mastiff Cargo Bike, Hungary

4.3.4. Ressolar Comunità Energetiche Rinnovabili, Italy

4.3.5. Sustainable Thermo-Modernisation, Poland

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Research Limitations

5.2. Future Research Directions

5.3. Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borzaga, C.; Bodini, R. What to make of social innovation? Towards a framework for policy development. Soc. Policy Soc. 2014, 13, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utting, P. (Ed.) Social and Solidarity Economy: Beyond the Fringe; Zed Books; UN Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD): London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/801751 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Di Lorenzo, F.; Scarlata, M. Social enterprises, venture philanthropy and the alleviation of income inequality. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ray, S.; Nair, R.; Nath, S.; Bishu, R. Exploring the sustainability of social enterprises: A scoping review. J. Sustain. Res. 2024, 6, e240044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (8 March 2011). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Roadmap for Moving to a Competitive Low Carbon Economy in 2050 (COM(2011) 112 Final). Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0112 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. (11 December 2018). Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Recast). Official Journal of the European Union, L 328, 82–209. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32018L2001 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- European Commission. (11 December 2019). The European Green Deal (COM(2019) 640 final). Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Bauwens, T.; Gotchev, B.; Holstenkamp, L. What drives the development of community energy in Europe? The case of wind power cooperatives. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiteva, R.; Sovacool, B. Harnessing social innovation for energy justice: A business model perspective. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.; Battilana, J.; Mair, J. The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2014, 34, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, H. Community-led social venture creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Sengul, M.; Pache, A.-C.; Model, J. Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organisations: The case of work integration social enterprises. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1658–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Janssen, F.; Kickul, J. In pursuit of blended value in social entrepreneurial ventures: An empirical investigation. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2016, 23, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, C.; Sebastião, J.R. Social Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship: Uncovering Themes, Trends, and Discourse. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, J.; Axon, S.; Morrissey, J. Social enterprise as a potential niche innovation breakout for low-carbon transition. Energy Policy 2018, 117, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Social Enterprise in Central and Eastern Europe: Theory, Models and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuchian, N.; Biju, A.K.V.N.; Reddy, K. An investigation on social impact performance assessment of the social enterprises: Identification of an ideal social entrepreneurship model. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katjiteo, A. Women empowerment through social enterprise. In Empowering and Advancing Women Leaders and Entrepreneurs; Haoucha, M., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiita, R.M. Social enterprises as drivers of community development in South Africa: The case of Buffalo City Municipality. S. Afr. J. Soc. Work. Soc. Dev. 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversole, R.; Barraket, J.; Luke, B. Social enterprises in rural community development. Community Dev. J. 2014, 49, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Lim, U. Social enterprise as a catalyst for sustainable local and regional development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, E.; Koelen, M.A.; Verkooijen, K.T.; Hassink, J.; Vaandrager, L. The health impact of social community enterprises in vulnerable neighborhoods: Protocol for a mixed methods study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e37966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socheata, S.; Hati, G. Comparative analysis of social enterprise development: A case study of Cambodia and Indonesia. Insight Cambodia J. Basic Appl. Res. 2024, 6, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarracino, F.; Fumarco, L. Assessing the non-financial outcomes of social enterprises in Luxembourg. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyoob, A.; Sajeev, A. Role of social entrepreneurship in sustainable development: Perspectives from business experts. In The Synergy of Sustainable Entrepreneurship; Neu, R., Qian, X., Yu, P., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygieł, E.; Śliwa, R. Social economy entities as a place to develop green skills—Research findings. Soc. Entrep. Rev. 2023, 1, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, C. Advancing the Social Economy for Socio-Economic Development: International Perspectives (Public Policy Paper Series No. 01). Canadian Social Economy Research Partnerships, Canada. 2009. Available online: https://base.socioeco.org/docs/doc-7845_en.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Bennett, N.J.; Lemelin, R.H. Situating the eco-social economy: Conservation initiatives and environmental organizations as catalysts for social and economic development. Community Dev. J. 2014, 49, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichevaliev, S.; Ortakovski, T. Social Entrepreneurship—The Much-Needed Accelerator of the Modern “Green” Economy. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual International Conference on European Integration—AICEI 2020, Skopje, North Macedonia, 18–19 September 2020; University American College Skopje: Skopje, North Macedonia, 2020; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismondi, M.; Cannon, K. Beyond policy “lock-in”? The social economy and bottom-up sustainability. Can. Rev. Soc. Policy 2012, 67, 58–73. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48670237 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Herbst, J.M. Harnessing sustainable development from niche marketing and coopetition in social enterprises. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2019, 2, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, A.; Raith, D. Social economy and environmental protection. In The Routledge Handbook of Cooperative Economics and Management; Michie, J., Blasi, J.R., Borzaga, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2024; pp. 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Wright, M. Understanding the social role of entrepreneurship. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M.; Brolis, O. Testing social enterprise models across the world: Evidence from the “International Comparative Social Enterprise Models (ICSEM) Project”. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2021, 50, 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratan, D. Success factors of sustainable social enterprises through a circular economy perspective. Visegr. J. Bioeconomy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekan, M.; Jonas, A.E.G.; Deutz, P. Circularity as alterity? Untangling circuits of value in the social enterprise–led local development of the circular economy. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 97, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, F. When the business is circular and social: A dynamic grounded analysis in clothing recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizou, P.J.; Gkanas, I. Community energy cooperatives and social entrepreneurship in Greece: A new paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Horst, D. Social enterprise and renewable energy: Emerging initiatives and communities of practice. Soc. Enterp. J. 2008, 4, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Sahay, A.; Hisrich, R.D. The social-market convergence in a renewable energy social enterprise. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudcová, E.; Chovanec, T.; Moudrý, J. Social entrepreneurship in agriculture: A sustainable practice for social and economic cohesion in rural areas—The case of the Czech Republic. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 10, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Green Skills and Jobs in the Social Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jindal, P.; Gouri, H. Circular economy models: A blueprint for sustainable entrepreneurship. In The Synergy of Sustainable Entrepreneurship; Neu, R., Qian, X., Yu, P., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, R.; Gumley, W. What role for the social enterprises in the circular economy? In Unmaking Waste in Production and Consumption: Towards the Circular Economy; Crocker, R., Saint, C., Chen, G., Tong, Y., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2018; pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Opstal, W.; Borms, L.; Brusselaers, J.; Bocken, N.; Pals, E.; Dams, Y. Towards sustainable growth paths for work integration social enterprises in the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barna, C.; Zbuchea, A.; Stănescu, S.M. Social economy enterprises contributing to the circular economy and the green transition in Romania. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Y Coop. 2023, 107, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Ospina, D.A.; Pinto, M.R.; Ometto, A.R. Influence of Social Inclusion on Recycling Cycles of Circular Economy: Waste Picker Organizations in the Global South; University of Cordoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutberlet, J. Grassroots eco-social innovations driving inclusive circular economy. Detritus 2023, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschi, D.E.; Arvanitidis, P. Social and solidarity economy initiatives in circular economy: The case of second-hand clothing in Greece. Int. Conf. Bus. Econ. Hell. Open Univ. 2023, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusz, M.; Jonas, A.E.G.; Deutz, P. Knitting circular ties: Empowering networks for the social enterprise-led local development of an integrative circular economy. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 201–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.P.; Fialho, R.L.L.; Gomes, P.A.P. Social technology for local recycling of plastic: An example of circular economy. J. Bioeng. Technol. Health 2023, 6, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Van der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of circular economy business models by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, V.; Sahakian, M.; Van Griethuysen, P.; Vuille, F. Coming full circle: Why social and institutional dimensions matter for the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friant, M.C.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Salomone, R. A typology of circular economy discourses: Navigating the diverse visions of a contested paradigm. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildingsson, R.; Kronsell, A.; Khan, J. The green state and industrial decarbonization. Environ. Politics 2019, 28, 909–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, H.; Carbajo, R.; Machiba, T.; Zhukov, E.; Cabeza, L.F. Improving Public Attitude towards Renewable Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Simcock, N. Spatializing energy justice. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, M.; Farinella, D. Renewable Energy Communities as Examples of Civic and Citizen-Led Practices: A Comparative Analysis from Italy. Land 2025, 14, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Gonzalez, M.; Dominguez-Ramos, A.; Ibañez, R.; Wolfson, A. Driving Decarbonization Opportunities with Social Acceptance in the Renewable Sector: The “Kosher Electricity” as the Case Study. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 4356–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson-Declève, S.; Spence-Jackson, H. Social Innovation for Decarbonisation: The Atlas School Project. In Social Innovation. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Osburg, T., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Zhou, W. Social Innovation Toward a Low-Carbon Society. In East Asian Low-Carbon Community: Realizing a Sustainable Decarbonized Society from Technology and Social Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 243–262. [Google Scholar]

- Cieslik, K. Moral Economy Meets Social Enterprise Community-Based Green Energy Project in Rural Burundi. World Dev. 2016, 83, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronka-Pośpiech, M. The Role of Social Entrepreneurship In Decarbonization: A New Avenue For Social Enterprises. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. 2023, 177, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, N.; Barry, J. Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions: Fossil fuel divestment and a “just transition”. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Sovacool, B.K.; Schwanen, T.; Sorrell, S. Sociotechnical transitions for deep decarbonization. Science 2017, 357, 1242–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Fressoli, M.; Thomas, H. Grassroots innovation movements: Challenges and contributions. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Wang, M.; Kumari, A.; Akkaranggoon, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Neutzling, D.; Tupa, J. Exploring short food supply chains from Triple Bottom Line lens: A comprehensive systematic review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Bangkok, Thailand, 5–7 March 2019; pp. 728–738. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Kumar, V.; Ruan, X.; Saad, M.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kumar, A. Sustainability concerns on consumers’ attitude towards short food supply chains: An empirical investigation. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twaróg, S.; Wronka-Pośpiech, M. Short food supply chains: Types of initiatives, inter-organizational proximity, and logistics–an intrinsic case study. Gospod. Mater. I Logistyka 2023, 3, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evola, R.S.; Peira, G.; Varese, E.; Bonadonna, A.; Vesce, E. Short Food Supply Chains in Europe: Scientific Research Directions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Schermer, M.; Rossi, A. Building food democracy: Exploring civic food networks and newly emerging forms of food citizenship. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2012, 19, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food supply chain approaches: Exploring their role in rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, M.D.; Charatsari, C.; Lioutas, E.D.; Vecchio, Y.; Masi, M. Staging value creation processes in short food supply chains of Italy. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobay, K.M.; Apetroaie, C. Sustainable rural development through local gastronomic points. Agric. Econ. Rural. Dev. 2024, 1, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Phillipson, J.; Gorton, M.; Tocco, B. Social capital and short food supply chains: Evidence from Fisheries Local Action Groups. Sociol. Rural. 2023, 64, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tsoulfas, G.Τ. Fostering urban short food supply chains: Evidence from the Netherlands. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 585, 11003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkema, M.; Hilletofth, P. Intermediate short food supply chains: A systematic review. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rover, O.J.; Martinelli, S.S. A trajectory of social innovations for the direct purchase of organic food by food services: A case study in Florianópolis, Brazil. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, R.; Arfini, F.; Baldi, L.; Donati, M. Economic Impact of Short Food Supply Chains: A Case Study in Parma (Italy). Sustainability 2023, 15, 11557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition (FSN); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Economic and Social Committee. The Role of Social Economy Enterprises in the Green Transition; European Economic and Social Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Social Economy Action Plan; European Commission: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Social Economy and the Green Transition; European Commission: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Fundamentals for an International Typology of Social Enterprise Models. Voluntas 2017, 28, 2469–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Social Economy and the Green Transition; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I.; Ventresca, M. Building inclusive markets in rural Bangladesh: How intermediaries work institutional voids. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 819–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A. The Legitimacy of Social Entrepreneurship: Reflexive Isomorphism in a Pre-Paradigmatic Field. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 611–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarassy, C.; Finger, D. Theoretical and Practical Approaches of Circular Economy for Business Models and Technological Solutions. Resources 2020, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, K.; Ruszkai, C.; Takács-György, K. Examination of Short Supply Chains Based on Circular Economy and Sustainability Aspects. Resources 2019, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcomes | Category | Outcome Description |

|---|---|---|

| Social | Individual Empowerment | Economic opportunities, skills development, and career growth empower individuals socially and economically [17,18] |

| Empowering marginalized groups, fostering self-esteem, leadership, and community engagement [18,19] | ||

| Community Development | Creating jobs, reducing inequality, and promoting social inclusion and participation [19,20] | |

| Fostering community recovery, cooperation, and social capital [21] | ||

| Mobilizing local resources for development and addressing local needs [20] | ||

| Societal Transformation | Addressing societal issues like income inequality, environmental degradation, and health disparities [22,23] | |

| Collaborating with stakeholders for sustainable local and regional development [21] | ||

| Increasing subjective well-being and reducing ill-being among disadvantaged groups [24] | ||

| Poverty Alleviation | Reducing poverty by creating job opportunities and providing skills training in underserved communities [21] | |

| Empowerment | Empowering marginalized groups, including women and girls, to enhance social status and economic independence [23] | |

| Community Strengthening | Fostering local engagement and collaboration to build stronger, more resilient communities [23,25] | |

| Environmental | Promotion of Green Skills | Developing green skills essential for a sustainable economy through learning-by-doing and innovation [26] |

| Supporting circular behavior through design thinking, creativity, and adaptability [26] | ||

| Conservation and Environmental Stewardship | Promoting environmental sustainability through conservation-based programs [27] | |

| Advocating for conservation as a means to achieve social and economic development goals [28] | ||

| Integration of Social and Ecological Missions | Combining social and ecological missions to address environmental issues and foster a green economy [29] | |

| Creating alliances of social actors for ecologically sound and socially just changes [30] | ||

| Challenges and Opportunities | Facing policy obstacles, lack of recognition, and challenges in policy support [31] | |

| Opportunities exist for niche marketing, coopetition strategies, and creating shared value across systems [27,32] | ||

| Sustainability Initiatives | Implementing environmentally sustainable practices to address climate change and resource depletion [25] | |

| Cultural Heritage Preservation | Safeguarding cultural heritage while promoting environmental stewardship, intertwining social and ecological goals [23] |

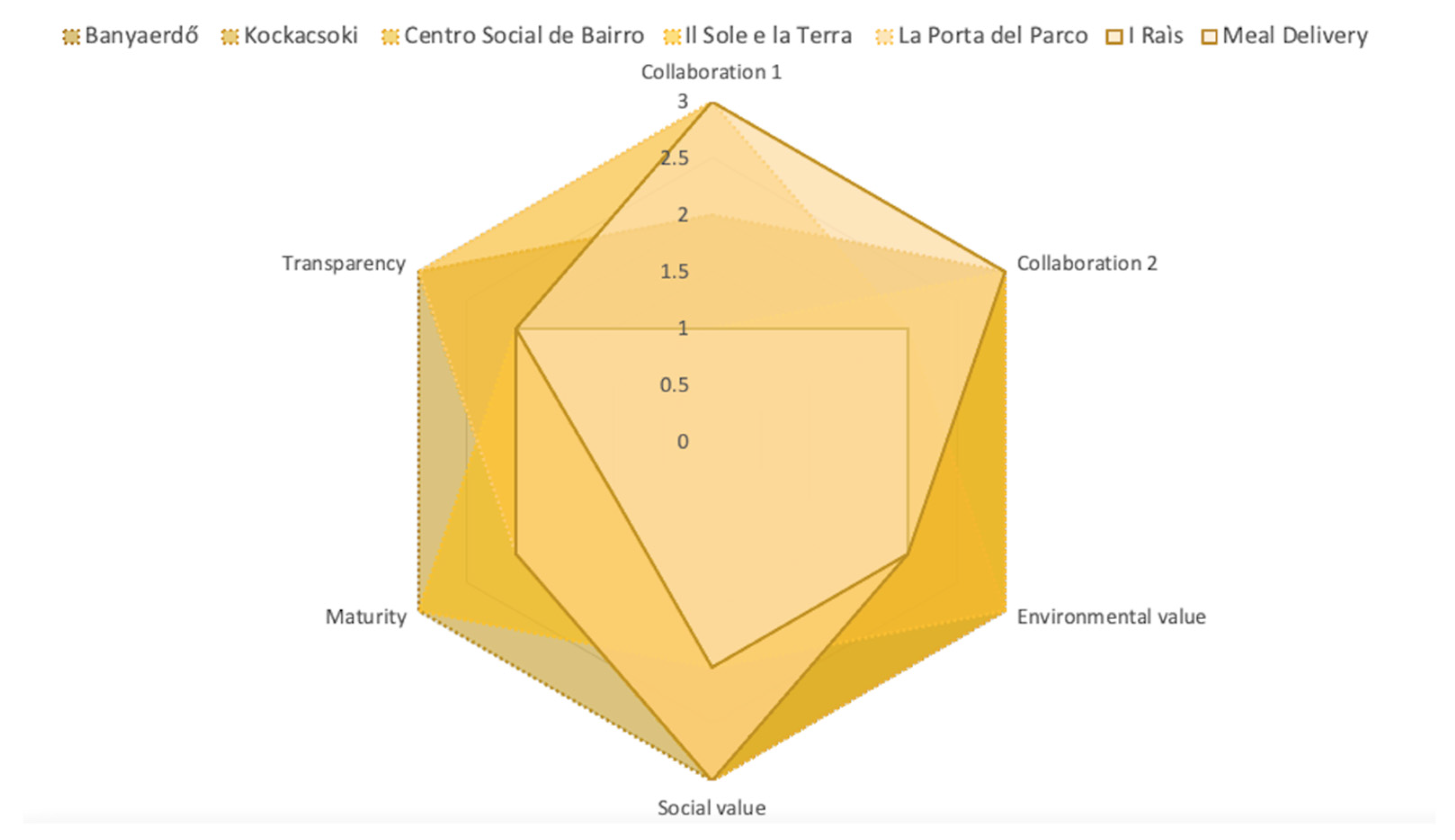

| Title 1 | Title 2 |

|---|---|

| Collaboration 1 | (1) The practice involves no collaboration between SEO and municipalities (2) There is occasional collaboration between SEO and municipalities (3) There is regular collaboration between SEO and municipalities |

| Collaboration 2 | (1) The practice does not network with other SEO (2) The practice is part of an informal network of SEOs and collaborates occasionally with them (3) The practice is part of a formal network of SEOs and cooperates constantly with them |

| Environmental value | (1) The practice involves no or little concern for CE, decarbonization or SFSCs (2) The practice aims to promote CE, decarbonization or SFSCs (3) Promotion of CE, decarbonization or SFSCs confirmed by quantitative or qualitative evidence |

| Social value | (1) The practice involves no or little concern for inclusion or employment (job creation, access to goods and services, participation or learning opportunities—for vulnerable groups) (2) The practice aims to promote inclusion or employment (job creation, access to goods and services, participation or learning opportunities—for vulnerable groups) (3) Positive effect on inclusion or employment confirmed by quantitative or qualitative evidence |

| Maturity | (1) The practice is less than 4 years old (2) The practice is between 4 and 9 years old (3) The practice is 10 years old or more |

| Transparency | (1) The responsible organizations communicate poorly about the practice; few information is available (2) Some information about the practice (activities, beneficiaries, outcomes, funding, finances, and governance) is made publicly available and information requests are answered (3) Information on activities, beneficiaries, outcomes, funding, finances, and governance is made publicly available on a regular basis |

| Country | Year | Type of Organisation | Type of Good Practice | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social | Environmental | ||||

| Banyaerdő | |||||

| Hungary | 2011 | Social Enterprise | Initiative of SEO | Individual Empowerment: providing fair wages, skills development, creating job opportunities for disadvantaged groups Community Development: building local partnerships, promoting social inclusion, cooperation with local stakeholders | Promotion of Green Skills: training in food production from forest resources, mushroom collecting, sustainable harvesting Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: using local natural resources responsibly, promoting sustainable tourism |

| Kockacsoki | |||||

| Hungary | 2015 | Social Enterprise | Initiative of SEO | Individual Empowerment: improving life conditions of young people with autism through employment and training Community Development: creating inclusive spaces (autism-friendly café), promoting social inclusion and participation Societal Transformation: raising awareness and reducing stigma related to autism | Sustainability Initiatives: promoting sustainable production and consumption (local handmade chocolate) Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: using sustainable ingredients and practices in chocolate production |

| Centro Social de Bairro | |||||

| Portugal | 2016 | Social Centre | Initiative of local/regional authorities involving SEO | Individual Empowerment: employment and training opportunities for young disabled people Community Development: promoting social and cultural inclusion, education, skill development Community Strengthening: fostering cooperation, local engagement, and SFSCs | Promotion of Green Skills: training in sustainable agriculture, local food production, circular economy practices Sustainability Initiatives: closed-loop system in food production, reuse of wood residues for energy, use of solar heaters Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: reducing waste, supporting local ecological solutions |

| Il Sole e la Terra | |||||

| Italy | 1979 | Non-profit consumer cooperative | Initiative of SEO | Individual Empowerment: creating work opportunities for vulnerable groups (disabled people, former prisoners, people in difficulty) Community Development: promoting social agriculture, local partnerships, training and inclusion Societal Transformation: promoting ethical consumption, fair trade and solidarity economy | Sustainability Initiatives: promoting organic farming, use of renewable energy, reducing food waste Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: selling bulk products, reusing packaging, compostable materials, circular practices in local food supply chains |

| La Porta del Parco | |||||

| Italy | 2013 | Municipality and two social cooperative | Initiative of local/regional authorities involving SEO | Individual Empowerment: providing jobs and training opportunities for vulnerable groups through social farming and catering Community Development: participatory urban regeneration, building social ties via community gardens, farmers’ market, cultural events Community Strengthening: inclusive use of public space, increasing social engagement of local residents | Sustainability Initiatives: conversion to organic farming, protection of agricultural land Promotion of Green Skills: teaching sustainable agriculture practices to community and vulnerable groups Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: supporting short food supply chains and local ecological solutions |

| I Raìs | |||||

| Italy | 2016 | Community cooperative | Initiative of SEO | Individual Empowerment: creating new job opportunities for young people, strengthening local identity and entrepreneurship Community Development: preventing depopulation of mountain areas, revitalizing local traditions and social life Community Strengthening: fostering cooperation among local farmers, offering services for residents and visitors, enhancing community well-being | Sustainability Initiatives: promoting short food supply chains through local food production and consumption Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: reuse of old mines for cheese aging, reducing environmental impact of transportation Promotion of Green Skills: sharing knowledge in sustainable tourism, local gastronomy, and ecological food systems |

| Meal Delivery | |||||

| Poland | 2021 | Municipality | Initiative of local/regional authorities involving SEO | Individual Empowerment: supporting seniors through daily meals and integration activities Community Development: social inclusion of elderly people, addressing social isolation, promoting active ageing Community Strengthening: fostering cooperation between local institutions and social economy actors | Sustainability Initiatives: meals prepared from locally sourced ingredients, reducing the environmental impact of long-distance transport Promotion of Green Skills: raising awareness on healthy eating and sustainable food practices Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: promoting SFSCs and supporting local producers |

| Country | Year | Type of Organisation | Type of Good Practice | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social | Environmental | ||||

| Municipal Furniture Bank | |||||

| Portugal | 2012 | Municipality and social enterprise | Initiative of local/regional authorities involving SEO | Individual Empowerment: providing free furniture to economically disadvantaged families, improving their living conditions Community Development: fostering solidarity, community engagement, and volunteering Community Strengthening: offering training and skill development in furniture restoration, involving vulnerable groups, seniors, and students | Sustainability Initiatives: promoting reuse of furniture, extending product life cycles Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: reducing waste and product consumption through circular economy practices Promotion of Green Skills: training in furniture restoration, upcycling, and conservation techniques. |

| Silesian Exchange Group | |||||

| Poland | 2017 | SEO | Initiative of SEO | Community Development: promoting social integration and cooperation through exchange events Community Strengthening: building local networks and fostering social engagement Education and Awareness: raising awareness of sustainable consumption, zero waste and circular economy practices | Sustainability Initiatives: promoting reuse of items and waste reduction through exchange events and online platform Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: reducing waste generation and landfill burden Promotion of Green Skills: encouraging responsible consumption habits and resource sharing |

| La Miniera | |||||

| Italy | 2016 | Municipality and social enterprise | Initiative of local/regional authorities involving SEO | Individual Empowerment: creating supported employment programs for vulnerable people Community Development: providing access to useful second-hand items for people with limited resources Community Strengthening: promoting the culture of reuse and social solidarity | Sustainability Initiatives: promoting reuse of items and extending product life cycles Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: reducing waste, saving raw materials, decreasing energy and cost of waste disposal Promotion of Green Skills: educating citizens about circular economy and environmental responsibility |

| Groupe Terre | |||||

| Belgium | 2017 | SEO | Initiative of SEO | Individual Empowerment: providing stable employment, involving workers in participatory decision-making, promoting fair working conditions Community Development: supporting local economic development, fostering social inclusion, engaging citizens in recycling culture Community Strengthening: building strong social networks through second-hand shops and social entrepreneurship | Sustainability Initiatives: collecting and recycling 17,000 tons of textiles annually, with 60% being reused Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: reducing textile waste, extending product life cycles, promoting responsible consumption Promotion of Green Skills: increasing awareness about textile reuse, recycling practices, and circular economy solutions |

| Country | Year | Type of Organisation | Type of Good Practice | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social | Environmental | ||||

| Smart Building Automation System | |||||

| Portugal | 2019 | Municipality | Initiative of local/regional authorities involving SEO | Individual Empowerment: increasing students’ social and environmental awareness, developing professional skills through practical projects Community Development: reducing operational costs in educational institutions, promoting smart and sustainable growth Community Strengthening: fostering cooperation between school, local government, and students | Sustainability Initiatives: significant reduction in electricity consumption (from €4200 to €1486 annually), reduction of CO2 emissions Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: rational use of natural resources, smart energy management systems, reuse of appliances and small components Promotion of Green Skills: teaching students skills in energy efficiency, smart technologies, and environmental responsibility |

| Green Office | |||||

| Poland | 2020 | Social Integration Centre | Initiative of SEO | Individual Empowerment: building ecological awareness and responsibility among employees and participants Community Development: promoting social responsibility in the workplace Education and Awareness: shaping pro-ecological attitudes, changing stereotypes about employment barriers | Sustainability Initiatives: green office principles—rational use of energy, reducing paper consumption, waste segregation Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: electronic circulation of documents, sustainable purchasing policies, energy-saving practices Promotion of Green Skills: educating about everyday ecological behaviours in office settings |

| Mastiff Cargo Bike | |||||

| Hungary | 2020 | Social enterprise | Initiative of SEO | Community Development: improving sustainable urban mobility, supporting SMEs and local businesses in reducing transport costs Education and Awareness: promoting ecological transport solutions within local communities and businesses | Sustainability Initiatives: zero-emission cargo bike replacing motor vehicles for short and medium-distance transport Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: reduction of CO2 emissions (saving approx. 12 tons of CO2 per replaced van), reduction in air pollution and noise Promotion of Green Skills: encouraging the use and adaptation of environmentally friendly transport solutions |

| Ressolar Comunità Energetiche Rinnovabili | |||||

| Italy | 2021 | Energy cooperative | Initiative of SEO | Community Strengthening: fostering cooperation between citizens, entrepreneurs, and local institutions around renewable energy Community Development: enabling collective energy production and management for economic savings and energy independence Education and Awareness: raising awareness about energy transition and sustainability | Sustainability Initiatives: promoting renewable energy use and maximizing local energy self-consumption Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: reducing dependence on fossil fuels, decarbonisation of the economy, energy autonomy of local communities Promotion of Green Skills: supporting knowledge and management of renewable energy technologies and local energy communities |

| Sustainable Thermo-Modernisation | |||||

| Poland | 2021 | Municipality and Social Integration Centre | Initiative of local/regional authorities involving SEO | Individual Empowerment: providing employment and skills development for socially excluded individuals through renovation works Community Development: improving living conditions of residents, increasing comfort and safety in apartments Community Strengthening: promoting professional and social reintegration of marginalized groups | Sustainability Initiatives: improving energy efficiency of buildings by 65.49%, reducing energy consumption and heating costs Conservation and Environmental Stewardship: connecting buildings to the central heating system, eliminating 22 tiled stoves, reducing CO2 emissions by approx. 66% Promotion of Green Skills: involving individuals in ecological renovation techniques, improving knowledge of sustainable building management |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wronka-Pośpiech, M.; Twaróg, S. Social Economy Organizations as Catalysts of the Green Transition: Evidence from Circular Economy, Decarbonization, and Short Food Supply Chains. Resources 2025, 14, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14090138

Wronka-Pośpiech M, Twaróg S. Social Economy Organizations as Catalysts of the Green Transition: Evidence from Circular Economy, Decarbonization, and Short Food Supply Chains. Resources. 2025; 14(9):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14090138

Chicago/Turabian StyleWronka-Pośpiech, Martyna, and Sebastian Twaróg. 2025. "Social Economy Organizations as Catalysts of the Green Transition: Evidence from Circular Economy, Decarbonization, and Short Food Supply Chains" Resources 14, no. 9: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14090138

APA StyleWronka-Pośpiech, M., & Twaróg, S. (2025). Social Economy Organizations as Catalysts of the Green Transition: Evidence from Circular Economy, Decarbonization, and Short Food Supply Chains. Resources, 14(9), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources14090138