Abstract

Cocoa is a natural resource that plays a very important role globally, being one of the most produced and traded commodities. As a labour-intensive product and considering that its cultivation involves about 50 million people globally, it seems significant to explore its social sustainability. In light of this, this research aimed to map social risks within the cocoa supply chain from a life cycle perspective. Therefore, the Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) was used, following the PSILCA database, considering the two most influential countries in its production, i.e., Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. The results showed that there could be a very high risk that more than half of the cocoa globally is produced through child labour and with wages too low to guarantee workers a decent living, returning incomes of $30–38/month. Forced labour is much less frequent than child labour, while cocoa from Ghana may induce a high risk of improper work, considering the 30.2 h per week worked by farmers. This is mainly due to the low association power of 10–16%, which reveals a high risk that workers may not organise themselves into trade unions. Finally, at 23–25%, there is also a very high risk of discrimination due to the high presence of migrant labour. Therefore, the S-LCA results showed that the cocoa industry is still characterised by socially unsustainable sourcing.

1. Introduction

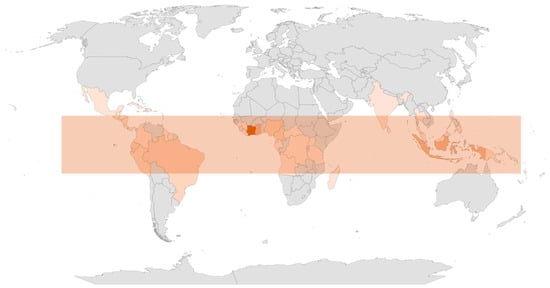

Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) is a species native to the tropical forests of the equatorial zone, the seeds of which, when dried, are used to make chocolate. From a nutritional point of view, it belongs to the category of “psychoactive” foods [1], among which are also tea and coffee, i.e., foods that possess tonic properties and act on the central nervous system since they contain caffeine, theine, ephedrine, and theobromine [2]. From a commercial point of view, on the other hand, it is an important cash crop for developing countries and an important branch of the food industry for industrialised countries [3]. Indeed, it is a resource that plays a very important role globally because it is a basic ingredient for the confectionery industry [4], as well as one of the most produced and traded commodities. Cacao grows exclusively in areas characterised by specific soil and climatic conditions that make its cultivation possible in just a few countries in the equatorial belt, in a remote area known as the cocoa belt (Figure 1). Although it is produced in various nations, nearly 2/3 of the world’s cocoa comes from West Africa, particularly from Côte d’Ivoire (38% of production, or about 2.23 million tons of cocoa) and Ghana (19% of production, or 1.1 million tons of cocoa) [5], which are found to be the first and second largest producers of cocoa globally, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, cocoa production contributes significantly to their GDP (in the range of 7.5–9%) [6] and to their exports (about 90% of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire’s exports are attributable to cocoa) [7].

Figure 1.

Cocoa Belt, major producing countries [5].

Table 1.

Major cocoa-producing countries globally (2022) [5] (tons).

This is also because the cocoa they grow and harvest is sold to the largest multinational chocolate manufacturers globally.

In addition to its influence on GDP, the agricultural sector’s heavy reliance on cocoa exports ensures the livelihood of many families by generating employment, promoting local micro-economies, and enhancing the countries’ reputation abroad [8].

In contrast, at the import level, the main importers of cocoa beans (whole, broken, raw, or roasted) were the Netherlands (713,532 kg), the United States (478,787 kg), Malaysia (471,676 kg), Germany (277,368), and Indonesia (252,121) [9] (Table 2). As can be seen from Table 2, cocoa beans are mainly consumed by European Countries, which consume nearly 50% of the world’s chocolate.

Table 2.

Major cocoa bean importing countries (2021) [9].

Thus, it seems clear that there is great inequality in the distribution of the value of this commodity, given that, on average, 70% of the total value generated within the supply chain goes to the actors who carry out the last two stages of the chain, namely marketing and processing.

In contrast, less than 20% goes to cocoa-producing countries [10], with producers to whom less than 5% of the price consumers pay returns (suffice it to say that during August 2023, front-month cocoa futures contract prices reached $10,080 per ton in New York, while in 2022–2023, the maximum price paid to producers was $2440 per ton) [11]. In addition, cocoa is a labour-intensive product: it is mostly harvested by hand using machetes and hooks through the labour of about 5 million families in plantations, 70% of which are smaller than three hectares [12], resulting in a highly fractionalised value chain. However, these productions account for about 80% of the cocoa that is then sold in markets [13] and are the main source of income for about 50 million people globally. In contrast, there is a great deal of control by a few multinational corporations that decide how and where value is created and distributed. Five companies influence more than half of the chocolate market, three of which account for more than half of the total cocoa supply [8]. This effectively shows how the cocoa value chain is characterised by highly asymmetrical power relations. But the cocoa supply chain also faces important environmental impacts, mainly related to three factors: (1) deforestation, (2) disease control, and (3) long supply chains, which cause important impacts related to long transportation journeys. In any case, the environmental implications of cocoa production have been extensively studied and quantified, especially from a Life Cycle Thinking (LCT) perspective [14], as shown by a recent literature study [15]. LCT refers to thinking about the consequences of a product or process’s environmental, economic, and social effects throughout its entire life cycle [16]. Currently, literature studies on the environmental assessment of the cocoa supply chain using LCA are well known, showing the existence of a fair body of literature. In contrast, Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) studies remain under-explored. Indeed, entering the keywords “Social Life Cycle Assessment AND Cocoa” on Scopus turned up only one article [17], which is focused on the social impacts of the chocolate industry. Therefore, in light of this research gap, and in light of the well-known related social issues, the objective of this article was to assess social impacts in the Cocoa supply chain using the Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) [18].

The S-LCA was chosen for different reasons. In particular, its international relevance and broad scientific consensus make it the most considered approach in the literature, as Ritcher et al. (2023) [19] stated. This could be useful, especially from a perspective of better comparison between future studies. But S-LCA was also chosen because it is connected to different global initiatives, such as the 10-Year Framework of Programs on Sustainable Consumption and Production and Agenda 2030) [18]. Finally, its holistic multi-stakeholder perspective can provide information related to different stakeholders and thus on multiple research areas. Therefore, while there are different methodologies for assessing social impacts, its soundness and scientific acceptability were crucial to its choice.

From a methodological point of view, there are two types of approaches for S-LCA, namely the Reference Scale Assessment (better known as Type I assessment) and the Impact Pathway Assessment (also known as Type II). The difference between the two approaches is that the former, to assess inventory data, considers reference scales defined by Performance Reference Points (PRPs) with which to compare its results (e.g., percentage of children working, number of hours per week, percentage of migrant workers, etc.) [20]. PRPs are defined as “internationally established thresholds or targets according to conventions and best practices” [20]. Therefore, based on the available data, the Type I assessment attempts to show whether the data that have been collected can correspond to a negative or positive performance, and thus to a given level of risk (from very low to very high). Instead, type II evaluation estimates the implications of impact pathways toward a given endpoint by assessing long-term impacts.

Consistent with the aim of this study and given the objective difficulties in applying type II assessment because of the problems associated with defining cause-and-effect pathways, type I assessment was applied. This choice is also consistent with further studies in the literature, including Tragnone et al. (2022) [21] and Zafar et al. (2024) [22], which have shown that type II is scarcely used.

In the cocoa supply chain, both worker communities and households face a large and growing number of challenges, such as those associated with livelihoods, working conditions, lack of access to inputs, and both labour and racial discrimination. Therefore, as cocoa farming involves about 50 million people globally, the majority of whom are in West Africa, it is timely to think deeply about the social impacts associated with cocoa farming, and thus, effective intervention strategies for preventing these impacts. Therefore, understanding the social implications of cocoa production considering different risk categories could provide insights to register some signs of positive change, thus informing broader discussions and interventions.

2. Literature Review

The literature related to Life Cycle Assessment applications in the cocoa sector currently has approximately 45 publications on Scopus. Scientific production has been rather erratic over time, although generally, it is growing. The first paper was published in 2009, thanks to the work of Ntiamoah and Afrane (2008) [23] who studied the life cycle stages of a Cacao crop in Ghana throughout the supply chain. Next, Ortiz-R et al. (2014) [24] evaluated a Cacao crop in Colombia, showing how improving agricultural practices and supply consumption can increase the productivity and competitiveness of Cacao. After that, Scherer and Pfister (2016) [25] showed how Cacao has a high environmental impact on Swiss eating habits. But Cacao crops in Indonesia, i.e., the third largest producer globally, have also been studied. In more detail, Utomo et al. (2016) [26] conducted an LCA taking 1 tonne of beans as a functional unit, showing how, if grown through agroforestry, Cacao could reduce environmental impacts compared to a monoculture crop. Then, there are also additional studies in which the focus of the environmental assessment is chocolate, including Recanati et al. (2018) [27], who find that cocoa sourcing and energy supply within the factory are the most impactful environmental hotspots. Of the same opinion is Konstantas et al. (2018) [28], who, evaluating the production of 1 kg of chocolate in the UK, describe impacts of 2.9–4.2 kg CO2 eq/kg chocolate, 37% of which is due to the raw material cultivation phase, as well as 10 k litres of water.

Also interesting are the findings of Pérez-Neira et al. (2020) [29], who show that the environmental impacts associated with transporting raw materials from West Africa to Europe could account for 9–51% of the total life cycle impacts of chocolate, in fact risking nullifying the environmental benefits of organic production. Bianchi et al. (2021) [30], Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha and Kiehbadroudinezhad (2022) [31], and Dianawati et al. (2023) [32] studied the environmental impacts of chocolate production of different types (white, dark, milk, chocolates, etc.). Finally, recently, Avadí (2023) [33] and Khang et al. (2024) [34] studied Cacao crops in Ecuador and Vietnam, respectively. The former showed that the agricultural stage in Ecuador has lower impacts than in other countries due to low input pressure. On the other hand, the second showed high environmental impacts associated with energy consumption during cocoa processing. Idawati et al. (2024) [35], in their study of Indonesian cocoa production, are of the same opinion. In any case, it is interesting to note that 55% of the literature related to the environmental impacts of cocoa and chocolate has been produced in the last four years, reflecting the recent scientific interest in the subject. Finally, from a geographical point of view, the two most prolific and influential countries seem to be Switzerland and Italy with 8 and 7 research articles, respectively. This is most likely due to the economic and cultural importance of chocolate for both countries, as well as the presence of multinational and popular chocolate companies in the area. What emerges from the literature, then, is that there is ample evidence of the environmental impacts associated with both cocoa and chocolate production. However, although social impacts are documented, little is yet known about their assessment from a Social Life Cycle Assessment perspective. In fact, to date, there is only one literature study concerning S-LCA applied to the chocolate supply chain. More specifically, Luna Ostos et al. (2024) [17] conducted an S-LCA in the Colombian chocolate industry. Thus, although the literature on environmental sustainability is useful for understanding the impacts of the cocoa supply chain, the social dimension is often neglected. Considering this research gap, this article could be a starting point to expand the literature on social impacts in the cocoa supply chain by considering some of the most influential producing countries, e.g., Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, providing a more comprehensive assessment of social impacts by considering the labour market, effects on local communities, and different types of stakeholders.

3. Materials and Methods

For the assessment of social impacts, the S-LCA was considered within this research article. This is a rather recent social impact assessment (it was born in 2009) [36] that, unlike E-LCA, does not yet have a reference standard (the ISO/AWI 14075 is expected to come out in 2025), but only generic UNEP guidelines (2020) [18], to which we adhered. For the assessment, the Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment (PSILCA) database [37] was followed. In particular, PSILCA provides threshold values called Performance Reference Points as well as international guidelines that return results that are comparable with other studies and, above all, reproducible.

Underlying S-LCA is the desire to adapt LCA standards to the social dimension [38], which is why, for this research article, the three typical steps of environmental Life Cycle Assessment were followed. Namely, (1) Goal and scope definition, (2) Life Cycle Inventory, and (3) Life Cycle Impact Assessment.

3.1. Goal and Scope Definition

The goal of this S-LCA was to assess the main risks in the cocoa supply chain; however, we only considered the cultivation phase. The two most globally influential countries were considered, namely Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. This is mainly for two reasons.

First, because together, they account for 50–70% of global cocoa production. Second, because of the absence of specific data on other countries (such as Indonesia and Ecuador), which made it was necessary to restrict the analysis to these two countries. However, the results of this study could provide an initial knowledge base that could open a stream of future research. Typically, in S-LCA studies, unlike in the E-LCA, the functional unit is not always expected, mainly due to the immateriality of social risks [39].

In fact, in E-LCA studies, there is a linear relationship between FU and impacts (for example, if 1 kg of output causes 1 kg of CO2, then 2 kg of output causes 2 kg CO2 eq and so on). In contrast, for S-LCA, there is no such linearity and intangible risks often do not depend on physical flows, which is why, within this research article, FU was not considered. Although the subject of the study is cocoa, considering 1 kg or 1000 kg does not affect the final results. Regarding the system boundaries, ideally, production from cradle to farm gate, while geographically, one could refer to Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire.

3.2. Social Life Cycle Inventory (S-LCI)

The data used within this article are quantitative and were extracted for one part from publicly available and accessible literature articles, reports, ministerial sources, and/or databases, and for another part from SimaPro 9.5 software. In more detail, in the case of child labour from Tham-Agyekum et al. (2023) [40] and the U.S. Department of Labor (2024) [41]. In the case of forced labour from de Buhr and Gordon (2018) [42] and the U.S. State Department (2024) [43,44], and the case of fair wages from Waarts and Kiewisch (2021) [45] and Wageindicator.org (2024) [46,47]. ILOSTAT (2023 and 2019) regarding working time [48] and workers’ rights [49], and Ghana Statistical Service (2023) [50] and Bros et al. (2019) [51] regarding migrant workers. Finally, data on GHG footprint were processed using SimaPro 9.5 software, using Ecoinvent v3.0 [52]. LCI indicators were defined by simple variables (e.g., wages, hours per week, percentage of the migrant labour force, labour force cases × 1000 population). An overview of the various inventory data and their respective sources can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1). In some cases, the inventory data were either absent or may not be fully representative of the problem underestimating its extent. However, the results of this study can be considered a good starting point for raising awareness of the likelihood and various social risks that cocoa production could face.

3.3. Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment (S-LCIA)

Two categories of stakeholders (Workers and Local Community) and eight categories of risk (Child Labor, Forced Labor, Fair Salary, Working Time, Workers Rights, Migrant Workers, Environmental Footprint, and GHG Footprint) were chosen, each of which in turn is defined by subcategories and indicators. The risk categories were chosen both because of data availability and because of their relevance to issues related to the Cocoa sector. The risk categories, subcategories, indicators, and PRPs were defined by PSILCA [37] and are shown in the Supplementary File (Tables S1 and S2). Then, the data were normalised according to five risk scales defined by PSILCA: very low, low, medium, high, and very high. These levels were represented graphically using a tachometer chart, where each risk level was associated with a colour (e.g., very low risk = dark green, low risk = light green, medium risk = orange, high risk = red, very high risk = dark red). As an example, for the trade union density indicator, the five PRPs are 80% < y (very low risk), 60% < y < 80% (low risk), 40% < y < 60% (medium risk), 20% < y < 40% (high risk), and 20% > y (very high risk). Therefore, if a value was to be 30%, then it would fall into the 20–40% PRPs, defining a high risk, and thus graphically, a red colour. After that, each risk scale was associated with a score from 0 to 5 (0 = no risk, 1 = very low risk, and so on up to very high risk) so that the results could be standardised and represented graphically by a scatter plot.

4. Results and Discussion

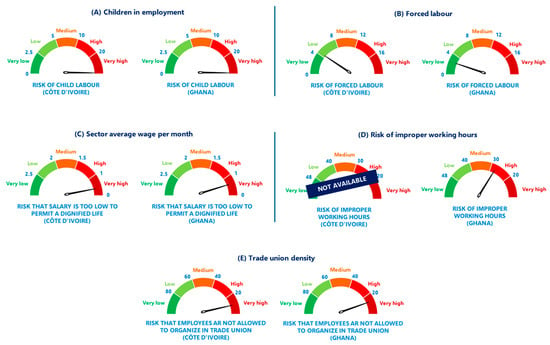

The results of the S-LCA are shown in Table 3 and normalised in Figure 2 and Figure 3. In this context, one aspect needs to be clarified. Social impacts are expressed in terms of risk since social effects cannot yet be attributed with certainty [53]. Therefore, if the social impact of producing a particular good or service cannot be known with certainty (at least for policy purposes), it may be sufficient to know the probability that a product or service is associated with an externality [54].

Table 3.

Social Life Cycle Assessment results.

Figure 2.

Normalised results of the S-LCA of cocoa cultivation (Stakeholders category: workers).

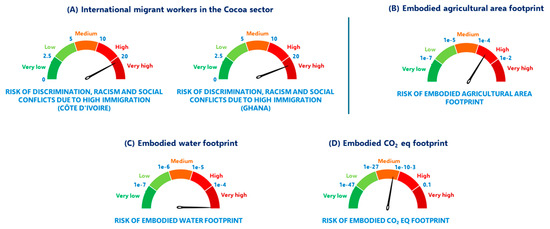

Figure 3.

Normalised results of the S-LCA of cocoa cultivation (Stakeholders category: Local community).

The use of the notion of risk has the advantage that risks so conceived can easily be used as explanatory factors in policy analysis.

Social risks may undermine growth prospects or jeopardize other key policy objectives, thus, perceived risks (rather than actual risk realisation) may cause actors to change their behaviour.

4.1. Workers

4.1.1. Child Labour

Regarding child labour, the results showed that in the 2018–2019 season, in both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, 73% and 26% of children between the ages of 5 and 17 years were engaged in cocoa production activities, respectively. Therefore, from an S-LCA perspective, it is highlighted that there could be a very high risk of child labour occurring within the cocoa supply chain (Figure 2A). The reason is that most children in West Africa live in extreme poverty and, therefore, start working as infants to support their families. Furthermore, in both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, most cocoa farmers earn an income below the poverty line, which is why they often use children to keep prices competitive [55]. On cocoa plantations, children are found working in extremely dangerous conditions [40]. They often use chainsaws and climb trees to retrieve beans, using machetes that are often larger than they are [56] that can injure them, even fatally.

The use of machetes is the norm for Ghanaian children, although this goes against the international labour laws of the United Nations, which concerns the elimination of the harshest forms of child labour [57]. Furthermore, both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, being in the equatorial zone, have to deal with the problem of the large population of insects and pests, which is why child workers are used for spraying copious doses of insecticides without protection, causing childhood illnesses [58]. Moreover, children on equatorial plantations are often also forced to cope with the bites of large snakes [59].

The risk of child labour in cocoa farming is certainly caused by the dramatic living conditions of the Ghanaian and Ivorian populations, as many families are often forced to face the grim reality of poverty and food insecurity, as well as a lack of access to adequate health services, which exacerbates their already fragile conditions. It is unacceptable that the cocoa industry still relies on child labour, just as it is unacceptable that small subsistence farms supply global agrifood giants. Despite the great economic value and commercial importance of cocoa, the massive presence of child labour makes it particularly unsustainable from a social point of view. Therefore, from this S-LCA emerges that there could be a very high risk that much of the chocolate bought and consumed globally may have been produced with child labour. Already in 2001, eight large multinational food industry corporations (ADM, Barry Callebaut, Cargill, Ferrero, The Hershey Company, Kraft Foods, Mars Incorporated, and Nestlé) signed the Harkin-Engel Protocol, a voluntary agreement aimed at eliminating child labour in rural communities in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire by 2005. This target was not achieved and has been modified over the years to reduce the harshest forms of child labour by −70% by 2020, again, in vain. Therefore, it is evident that behind the production of cocoa, the shadow of child labour still lurks, and little progress has been made over the years, with food industries knowingly profiting from child labour. This is also compounded by the lack of effectiveness of local laws. For example, in Ghana, in the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda, an attempt was made to regulate child labour, although this law is not consistent with the procedures prescribed by Convention No. 182 and Recommendation No. 190 of the International Labour Organization [59]. This shows that both the food industry and governments are currently making no progress in reducing child labour, and that the situation is not improving. In the literature, although there is widespread awareness of child labour conditions in West Africa, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the level of risk from an S-LCA perspective, and it is this gap that the study sought to fill.

4.1.2. Forced Labour

The results of the indicator associated with this sub-category show that, with 3.3 cases per 1000 inhabitants (Ghana) and 4.2 cases per 1000 inhabitants (Côte d’Ivoire), there is a very low risk of forced labour for cocoa cultivation from an S-LCA perspective (Figure 2B). These data show that forced labour is much less usual and widespread than child labour, and are consistent with Walk Free Foundation estimates, which show that in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, forced labour affects less than 1% of children and less than 0.4% of adults [60]. But these findings are also consistent with Perkiss et al. (2021) [61], who show that forced labour in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire represents a very small subset of the child labour problem and is not widespread for adult workers; in fact, it affects less than child labour. Moreover, it also appears that forced labour is limited to the recent migrant labour force [62]. There is little evidence in the Scopus literature that shows quantitative data or explanations for forced labour in the cocoa sector, most likely because there is often a tendency to talk more about the more general problem of child labour. It is also interesting to note that there is a rather questionable interpretation of the definition of forced labour, which is defined by the International Labour Organisation as ‘any work or service extorted from a person under threat of punishment and for which the person has not offered himself voluntarily’. Therefore, forced labour implies a form of work against one’s will, and cases often involve a form of deception. However, in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, work for many farmers is most likely a real necessity due to the spiral of poverty in which they gravitate daily. For this reason, it could be that work is not perceived by farmers as forced but as a real necessity, fundamental for the sustenance of their families. Or, it could also be very likely that, given the hidden nature of much forced labour, the figures of 3.3 and 4.2 cases per 1000 inhabitants are vastly underestimated, and that there are much higher levels within the cocoa sector [62]. However, this estimate represents the first basis for the assessment of forced labour in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, and more generally in cocoa cultivation from an S-LCA perspective, and both government and supply chain actors should better understand the issue, e.g., through the emergence of a central data collection system associated with forced labour and/or child labour.

4.1.3. Trafficking in Person

One of the main accusations made against cocoa farmers is that they traffic children who are sold as slaves every year [63]. In the cocoa supply chain, the most common forms of human trafficking involve the placement of children with other families in return for monetary compensation for a while. This form of bonded labour is often part of an exchange of labour as repayment of debts, and is again most often driven by extreme poverty, as well as facilitated by an African tradition of migration [64]. Most victims of trafficking, especially in Côte d’Ivoire, are Nigerian, Vietnamese, and Thai nationals, as well as Burkinabe and Malians. The Ghanaian and Ivorian governments have addressed the problem of child trafficking through local or bilateral initiatives. More specifically, both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire fall into Tier Placement #2, thus showing a medium risk of trafficking in person in both cases. In more detail, the Ghanaian government does not meet basic standards to eliminate trafficking and smuggling of persons, but is nevertheless making efforts to attempt to do so. For instance, through increased prosecutions, convictions, and investigations, as well as improved monitoring and providing targeted training [44]. This may also explain the low levels of forced labour in the sector. Again, it is evident that human trafficking is a consequence of widespread poverty among rural cocoa-growing communities. Likewise, the Ivorian government does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking, but is making efforts to do so; for instance, through the identification of potential children and vulnerable persons. The government initiated a program to identify children using the streets as a source of livelihood, referring them to shelters or family homes.

However, the provision of social incentives, shelters, or services remained inadequate. In addition, the interagency anti-trafficking committee (CNLTP) did not receive adequate funding for the fourth consecutive year, while the police force did not receive adequate training in the investigation and detection of trafficking persons [43]. Therefore, it is clear that, although there have been interesting initiatives by both governments over the years, the situation is still far from being resolved.

4.1.4. Fair Salary

Wages and income are important factors influencing the quality and standard of living of workers, which is why they are quite relevant for SLCA. In this case, for this indicator, the results show values of 0.82 for Ghana and 0.43 for Côte d’Ivoire, both of which correspond to a very high risk that wages are too low to allow cocoa farmers a decent living (Figure 2C). This value was calculated based on the grids provided by PSILCA, dividing the sector average wage by the minimum wage for that country. Waarts and Kiewisch (2021) [45] estimate average wages in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire of $1.42/per capita and $1.23/per capita per day, respectively (i.e., $38.34/per capita per month and $40.84/per capita per month, respectively). Whereas minimum wages are GHS 18.15 ($1.18) per day (as of January 2024) in Ghana for a 27-day job and F CFA 39.960 ($66.34) per month in Côte d’Ivoire [46,47]. These figures show appallingly low incomes for cocoa farmers, with more than one million people possibly lacking access to basic needs. But the most surprising fact is that incomes of $1.42 and $1.23 per capita per day, in the face of immense profits by multinational corporations, are well below the benchmarks for measuring incomes and poverty in the world. The World Bank in 2022 adjusted the poverty line upwards from $1.90 to $2.15 due to inflation [65]. Thus, it emerges that the currently known incomes for Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are respectively $0.73 and $0.92 below the poverty line. This is why cocoa farmers should earn at least +51% and +74%, respectively, to at least meet their basic needs, just as they would have to triple their incomes to live a decent life, including affording healthy food, drinking water, health services, education, etc. All this shows and confirms that in the cocoa supply chain, there is indeed a highly asymmetric distribution of value, with farmers living in extreme poverty because they receive too low a price and income, while brands and retailers create value along the chain through marketing and branding, thus acquiring most of the value. Most of the value creation in the chain is related to non-tangible aspects that prevail over terroir and the social component that is rarely valued. In both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, the price of cocoa is set by the state at the beginning of the season [66]. In October 2020, to increase the price of cocoa, both governments imposed the Living Income Differential (LID), i.e., a $400/ton surcharge that the industry has to pay on top of the cocoa price [67]. However, the LID is very unlikely to reduce the poverty of cocoa farmers in the long run, especially due to the difficulty of controlling the increase in cocoa supply and the difficulty of alignment within the value chain. Furthermore, it seems that the pricing mechanism is not transparent, also due to both corrupt practices as well as the fact that there is no official policy document on LID providing more details, which could lead to different views on how to achieve inequity and poverty reduction in the long run [68]. Therefore, so long as there is an unequal power structure within the supply chain where small farmers have little power to set prices, even considering the volatility of global prices, poverty will most likely persist. Moreover, low producer prices, in addition to undermining earnings, may prevent farmers from investing in improving cocoa productivity and quality.

4.1.5. Working Time

In this case, only data from Ghana were available for the assessment [49], which showed that Ghanaian farmers work an average of 30.2 h per week. Therefore, this value corresponds to a high risk of improper working hours (Figure 2D). PRPs are based on ILO Convention No.1 of 1919, which establishes 40–48 h as normal working hours. Anything above or below these hours could result in an inability to realize one’s professional goals, whether due to time or economic limitations. However, the figure of 30.2 h per week may not be so easily interpreted, besides the fact that it is not known whether this value also includes children (who are not used to working too many hours per day, either by law or due to physical limitations, as shown by Thorsen and Maconachie, 2023) [56] or refers only to adult workers. This is then an annual average figure, which does not consider how the greatest demand for labour occurs during the harvest season (October-December), which is why the figure and thus the risk of improper working hours could be widely variable [56]. Or even, through a social deconstruction of the forms of work, the few hours worked could be because typically, cocoa cultivation is labour-intensive, as pointed out by Kissi and Herzig (2024) [69], which is why there are most likely many workers in the field, and thus the hours are distributed over a very large number of people.

Indeed, the cultivation of cocoa requires many processes, carried out by many people [56]. Therefore, from this perspective, further investigations are needed to map and quantify the working conditions and hours of work of cocoa farmers in Ghana. In any case, working hours per employee are directly related to the sector average wage, since the too-low number of hours could lead to equally low earnings and thus prevent workers from achieving professional fulfilment and the ability to meet their basic needs. Therefore, it is easy to assume that there is a link between improper working hours, low incomes, and the vulnerability of cocoa farmers. This could create a dangerous spiral in which the lack of access to financial services due to the low income from the few hours worked makes it difficult for farmers to escape from poverty. Workers may find it difficult to access credit and thus lack the means to purchase resources.

4.1.6. Working Rights

The results of this indicator showed values of 16.8% and 10.6% for Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, respectively, showing a very low rate of unionisation for both countries [48]. This corresponds to a very high level of risk that workers in the cocoa supply chain may not organize in trade unions (Figure 2E). Indeed, this data confirms the findings of Kissi and Herzig (2024) [69], who showed that agricultural labour in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire is very fragmented and is organised according to different forms of irregular work. It is then also characterised by divisions of labour, a high labour force, land tenure, caporalato, and gender differences, as well as a low wage rate [70]. Moreover, in Ghana especially, farmer–landowner relations are organised based on verbal agreements [70]. Smallholder farmers, then, often rely on informal relationships rather than formal networks to access support. This is also compounded by the fact that most cocoa is produced by small farmers who work independently, which makes it difficult to organize them into unions, as well as the fact that farms are often dislocated and dispersed, further complicating efforts to unionize the workforce [71]. It may also be the case that the widespread use of child labour in the cocoa sector complicates unionisation efforts. Indeed, child workers are not in a position to join trade unions or support better working conditions. Therefore, this is at the root of the low associative power (understood as the ability to be able to improve their working conditions through collective efforts) of workers in the cocoa sector. It is most likely the low rate of unionisation in the cocoa sector that perpetuates the cycle of exploitation and poverty faced by farmers. Indeed, without trade unions supporting fair wages, cocoa farmers and workers receive very low wages, which prove insufficient to meet their basic needs. Likewise, the lack of union representation often means inadequate working conditions, in addition to the fact that farmers remain vulnerable to market volatility and price fluctuations, lacking the collective bargaining power to negotiate better terms or prices for their cocoa.

4.2. Local Community

4.2.1. Migrant Workers

As for this risk sub-category, the S-LCA results showed that in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, with 23.2% and 25%, respectively, there is a very high risk of discrimination, unfair labour conditions, and conflicts with local communities (Figure 3A). Indeed, this is because small cocoa farmers have little financial capacity to hire the required labour, which is why they use cheaper sources of labour such as migrant labour [72]. However, some literature studies, including Kessie et al. (2015) [73] and Manoj and Viswanath (2015) [74], highlight how migrants face issues related to low wages, precariousness, and lack of bargaining power, which contribute to the social unsustainability of cocoa production. For Côte d’Ivoire, migration flows come mainly from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Guinea [75], while for Ghana, migration flows come mainly from Nigeria, Togo, and Burkina Faso [76]. Therefore, while migration practices have contributed a great deal to the economies of the two countries, the working conditions of a large amount of migrant labour could lead to a very high risk that the chocolate purchased worldwide is produced from poor working conditions such as low pay, unsafe working environments, no freedom, and no rights. Moreover, from a social point of view, migrants might still suffer discrimination and exclusion within local communities, exacerbating their conditions.

The migrant labour force is essential for maintaining the productivity of cocoa plantations and plays a key role in sustaining the production levels necessary for Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire to maintain their leading positions in the global cocoa market. However, ensuring fair treatment and improving the living and working conditions of these workers remain critical challenges.

4.2.2. Environmental and GHG Footprints

In this case, the evaluation results were obtained using the SimaPro 9.5 software, choosing it as the functional unit for the production of $1 of product, which in this case is the weight of the equivalent of $1 of raw cocoa. The results showed that it produces 1.20 × 10−4 ha embodied agricultural area footprint, 33 mm3 embodied water footprint, and 1.16 × 10−3 t embodied CO2 eq. These ratings serve to investigate the direct intensity of how many non-monetary factors were used to produce that particular product. These values correspond to a high (agricultural area), very high (water), and medium (CO2) risk of embodied footprint, respectively (Figure 3B–D). The cultivation of cocoa is indeed highly labour intensive, requiring little or no mechanisation, which is why the CO2 emissions associated with the cultivation phase might not be very high, unlike the chocolate production phase, in which other ingredients are added [28]. Therefore, there is a medium risk in this case. On the other hand, it is well known that cocoa production is strongly linked to land use and deforestation. This is mainly related to the soil and climatic conditions of the plant. Indeed, cocoa requires a very shady environment for its growth (70% shade for young trees and 30–40% shade for more mature ones) and temperatures of around 18–30 °C for efficient physiological functioning [77]. On the other hand, at higher temperatures, the photosynthetic mechanism of the leaves may be impaired, thus affecting yield.

Therefore, the cacao tree does not like direct sunlight and temperature fluctuations, which is why it prefers to live in the shade of other trees, which can be used for timber or fruit production. However, in recent decades, traditional cocoa varieties such as Amazons and Amelonado have been gradually replaced by new hybrid varieties that, compared to the former, have greater sun resistance and higher short-term yields [78]. Intensive full-sun systems require more inputs, including fertilizers, which are often out of reach for small cocoa farmers. Thus, new varieties do not require any forest cover, which is why the areas devoted to cocoa production have increased considerably, inducing land use change and deforestation. This increase in cultivated area has often taken place through slash and burn of virgin forests, resulting in a loss of biodiversity and a general impoverishment of soils [79]. However, it is also interesting to note that cocoa is initially planted on fertile soils. However, after about 25–30 years, yields decrease, and the incidence of pests and diseases increases. Since small farmers do not have the means to restore and renew their plantations, they start a new cycle of deforestation [80]. In contrast, regarding the embodied water footprint, the very high risk is not so much due to the cultivation phase, which is mostly rain-fed, but more to the processing phase, e.g., to dilute pesticides and herbicides [81].

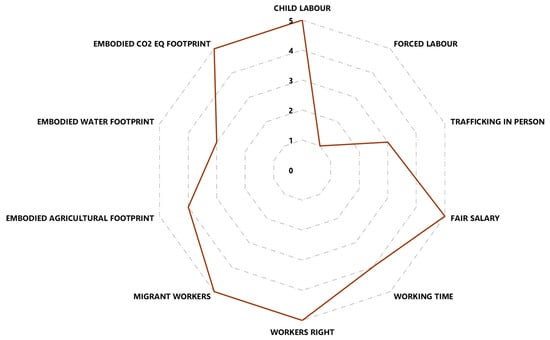

4.3. Main Findings

The key results of this social evaluation, as also shown in Figure 4, revealed that:

- i.

- Behind cocoa production, the shadow of child labour still lurks. There could be a very high risk that more than half of the cocoa globally is produced by child labour, used mainly to keep prices competitive. The massive presence of child labour makes the chocolate industry still unsustainable from a social point of view. In this respect, local laws are still ineffective, which is why no progress has been made in reducing child labour within the supply chain.

- ii.

- There might be a very low risk that more than half of global cocoa is produced by forced labour, which is therefore much less common than child labour. In this respect, the Ghanaian and Ivorian governments do not fully meet the basic standards to eliminate forced labour, and it is evident that the situation is still far from being fully eradicated.

- iii.

- With incomes of $1.42/day (Ghana) and $1.23/day (Côte d’Ivoire), there may be a very high risk that the wages of cocoa farmers globally are too low to guarantee them a decent living. These figures show how they would have to earn +51% and +74% at least, respectively, to meet their basic needs, and how the structure of the cocoa market is therefore highly unbalanced in the division of revenues.

- iv.

- Cocoa from Ghana could induce a high risk of improper working hours, although it is not known whether this figure also includes hours worked by children. Working too few hours could deny workers access to credit as well as access to basic needs, perpetuating an endless spiral of poverty.

- v.

- Underlying the low wages and improper working hours is a low power of association, which is reflected in the unsustainability of cocoa production. Thus, 56% of global cocoa could be produced with a very high risk that workers cannot organize themselves into trade unions.

- vi.

- The migrant labour force in the cocoa sector, while necessary, may induce a high risk of discrimination, conflicts with local communities, and unfair working conditions.

- vii.

- No positive impacts were found in cocoa cultivation.

Figure 4.

Overview of the social sustainability of cocoa farming from an S-LCA perspective.

Verifying the results of this research with those of similar studies is difficult to date, given the absence of literature studies on S-LCA and cocoa production. Therefore, starting precisely from this research gap, consistent with the initial objective, this study aims to expand the literature on the social impacts of cocoa production from an S-LCA perspective. Although lacking quantitative data for comparison with other studies in the literature, the results of this study could be a good starting point for expanding the narrative on inequalities within this sector.

5. Conclusions

The results of this S-LCA confirm the bitter truth about the cocoa industry, namely that it is still characterised by socially unsustainable sourcing. This is due to multiple reasons, including widespread poverty, low wages, need for labour, poor government involvement, lack of alternative education opportunities, discrimination, political instability, and conflict. Therefore, stakeholders should holistically and collectively address these root causes to ensure social sustainability in the cocoa supply chain. For instance:

- (1)

- Northern governments should support West African governments in improving monitoring systems and actions towards child labour, such as investing in primary education.

- (2)

- West African governments should constantly update minimum wage prices for cocoa workers.

- (3)

- Producing and exporting countries, as well as the food industry giants, should establish regulations for due diligence on human and environmental rights for all companies selling products containing cocoa.

- (4)

- Companies could act more constructively, e.g., by using blockchain technology to track movements within the supply chain, which would allow human rights abuses to be identified.

- (5)

- Consumers should induce brands and supermarkets to provide clear answers regarding social sustainability in the cocoa supply chain.

- (6)

- Cocoa production should be based on traditional agroforestry systems, e.g., planting shade trees and using different varieties of timber, pulses, and fruit trees. In this way, the economy of rural households would be diversified, creating additional forms of income through the sale of products from these trees.

- (7)

- In the main cocoa-consuming regions, approved and future legislation should be designed to guarantee market access only to companies that concretely address sustainability issues related to human rights and the environment. In this context, the European deforestation-free legislation will require companies to prove that certain forestry-hazardous raw materials imported into the EU have not been produced at the expense of natural forests felled after December 2020.

However, the research has some limitations that could affect the final results. Firstly, from a methodological point of view, no primary data were used, but secondary data such as reports, literature, or databases were used instead. Therefore, the absence of primary data may not fully capture the specific conditions of the studied cocoa supply chain. This may lead to a lack of specificity, where data may be generalised, thus reducing the accuracy of the results. Therefore, it is important that such limitations are recognised, considering the integration of mixed methods using both primary and secondary data to improve the robustness and reliability of future evaluations in the future. Furthermore, the scarcity of social data (both primary and secondary) leads to the exclusion and inadequate consideration of certain categories of stakeholders, effectively underestimating the extent of the problem. By selecting only a subset of these categories, the research may focus only on specific social issues, potentially neglecting other relevant impacts. Some relevant categories, such as the number of fatal and non-fatal occupational accidents, presence of sufficient safety measures, violations of mandatory health and safety standards, workers affected by natural disasters, and evidence of violations of laws and employment regulations were not considered; in fact, this resulted in an incomplete understanding of the challenges associated with social sustainability in the cocoa sector. Therefore, from this point of view, it would be desirable for future research to increase the amount of measurable social indices that can expand the effectiveness, as well as transparency and social awareness in the cocoa sector, so that future comparisons between different studies can also be made. Although this study provides an initial knowledge base, more complete and up-to-date data will be needed, on which future studies should focus. For now, a dark side characterised by unethical exploitation, environmental degradation, and social injustice continues to lurk behind the chocolate industry.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/resources13100141/s1, Table S1: Sources of the quantitative and qualitative indicators used; Table S2: Quantitative indicators: value, reference scale, and performance reference points.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.R. and G.V.; methodology, M.R.; software, G.V.; validation, G.V., L.G. and M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.R.; resources, G.V.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.R.; visualisation, G.V.; supervision, G.V., L.G. and M.S.; project administration, G.V.; funding acquisition, G.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study are public and cited within the manuscript according to the journal guidelines. In addition, any data and/or information is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially carried out within the Agritech National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e resilienza, PNRR–Missione 4 Componente 2, Investimento 1.4, CN000022, CUP: B83C220029200007).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Casperson, S.L.; Lanza, L.; Albajri, E.; Nasser, J.A. Increasing Chocolate’s Sugar Content Enhances Its Psychoactive Effects and Intake. Nutrients 2019, 11, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata-Alvarez, A.; Bedoya-Vergara, C.; Porras-Barrientos, L.D.; Rojas-Mora, J.M.; Rodríguez-Cabal, H.A.; Gil-Garzon, M.A.; Martinez-Alvarez, O.L.; Ocampo-Arango, C.M.; Ardila-Castañeda, M.P.; Monsalve-F, Z.I. Molecular, biochemical, and sensorial characterization of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) beans: A methodological pathway for the identification of new regional materials with outstanding profiles. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacometti, J.; Jolić, S.M.; Josić, D. Cocoa Processing and Impact on Composition. In Processing and Impact on Active Components in Food; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.P.P. Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.). In The Agronomy and Economy of Important Tree Crops of the Developing World; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 131–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocoa Producing Countries. World Population Review. 2024. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/cocoa-producing-countries (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Métangbo, D.; Akpa, L.; Ouattara, A.; Lhaur-Yaigaiba Kpan, G.O.; Koffi, A.; Yao Koffi, B.; Yapi Assa, F.; Soro, D.; Agbri, L.; Biémi, J. Climate and Agriculture in Côte D’ivoire: Perception and Quantification of the Impact of Climate Change on Cocoa Production by 2050. Int. J. Environ. Clim. 2023, 13, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANEME—Associação Nacional das Empresas Metalúrgicas e Eletromecânicas. Estudo de Levantamento e Caracterização das Empresas Industriais de São Tomé e Príncipe. Estudo São Tomé e Príncipe. 2018. Available online: https://www.aneme.pt/site/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Estudo_S%C3%A3o-Tom%C3%A9-e-Pr%C3%ADncipe-2018_VF-CORRIGIDA.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Prazeres, I.; Lucas, M.R.; Marta-Costa, A. Cocoa Markets, and Value Chains: Dynamics and Challenges For Sao Tome and Principe Organic Smallholders. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2021, 7, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Cocoa Beans, Whole or Broken, Raw or Roasted Imports by Country in 2021. 2024. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/ALL/year/2021/tradeflow/Ixports/partner/WLD/product/180100# (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- FAO; BASIC. Comparative Study on the Distribution of Value in European Chocolate Chains. In Paris. 2020. Available online: https://www.eurococoa.com/wp-content/uploads/Comparative-study-on-the-distribution-of-the-value-in-the-European-chocolate-chains-Full-report.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Investing.com. US Cocoa Futures—Dec 24 (CCZ4). 2024. Available online: https://www.investing.com/commodities/us-cocoa (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Prazeres, I.C.; Lucas, M.R. Repensar a cadeia de valor do cacau biológico de São Tomé e Príncipe. Rev. Ciênc. Agrár. 2020, 43, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voora, V.; Bermúdez, S.; Larrea, C. Global Market Report: Cocoa. Sustainable Commodities Marketplace Series. The International Institute for Sustainable Development. 2019. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/ssi-global-market-report-cocoa.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- D’Eusanio, M.; Serreli, M.; Petti, L. Social Life-Cycle Assessment of a Piece of Jewellery. Emphasis on the Local Community. Resources 2019, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dong, Y. Applications of Life Cycle Assessment in the Chocolate Industry: A State-of-the-Art Analysis Based on Systematic Review. Foods 2024, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjana, S.H.; Mahmud, M.A.P.; Huda, N. Introduction to Life Cycle Assessment. In Life Cycle Assessment for Sustainable Mining; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna Ostos, L.M.; Roche, L.; Coroama, V.; Finkbeiner, M. Social life cycle assessment in the chocolate industry: A Colombian case study with Luker Chocolate. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 929–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations; Benoît Norris, C., Traverso, M., Neugebauer, S., Ekener, E., Schaubroeck, T., Mankaa, R., Russo Garrido, S., Berger, M., Tragnone, B.M., Valdivia, S., et al., Eds.; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, F.; Gawenko, W.; Götze, U.; Hinz, M. Toward a methodology for social sustainability assessment: A review of existing frameworks and a proposal for a catalog of criteria. Schmalenbach J. Bus. Res. 2023, 75, 587–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo Garrido, S.; Parent, J.; Beaulieu, L.; Revéret, J.P. A literature review of type I SLCA—Making the logic underlying methodological choices explicit. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragnone, B.M.; D’Eusanio, M.; Petti, L. The count of what counts in the agri-food Social Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 354, 131624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, I.; Stojceska, V.; Tassou, S. Social sustainability assessments of industrial level solar energy: A systematic review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntiamoah, A.; Afrane, G. Environmental impacts of cocoa production and processing in Ghana: Life cycle assessment approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1735–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-R, O.O.; Gallardo, R.A.V.; Rangel, J.M. Applying life cycle management of Colombian cocoa production. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 34, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, L.; Pfister, S. Global Biodiversity Loss by Freshwater Consumption and Eutrophication from Swiss Food Consumption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 7019–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utomo, B.; Prawoto, A.A.; Bonnet, S.; Bangviwat, A.; Gheewala, S.H. Environmental performance of cocoa production from monoculture and agroforestry systems in Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134 Pt B, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recanati, F.; Marveggio, D.; Dotelli, G. From beans to bar: A life cycle assessment towards sustainable chocolate supply chain. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantas, A.; Jeswani, H.K.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. Environmental impacts of chocolate production and consumption in the UK. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Neira, D.; Copena, D.; Armengot, L.; Simón, X. Transportation can cancel out the ecological advantages of producing organic cacao: The carbon footprint of the globalized agrifood system of Ecuadorian chocolate. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.R.; Moreschi, L.; Gallo, M.; Vesce, E.; del Borghi, A. Environmental analysis along the supply chain of dark, milk and white chocolate: A life cycle comparison. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2021, 26, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Kiehbadroudinezhad, M. Environmental Impacts of Chocolate Production and Consumption. In Trends in Sustainable Chocolate Production; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianawati, D.; Indrasti, N.S.; Ismayana, A.; Yuliasi, I.; Djatna, T. Carbon Footprint Analysis of Cocoa Product Indonesia Using Life Cycle Assessment Methods. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avadí, A. Environmental assessment of the Ecuadorian cocoa value chain with statistics-based LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 1495–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, D.S.; Linh, N.H.K.; Hoai, B.T.M. Life Cycle Assessment of Cocoa Products in Vietnam. Proces.s Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2024, 8, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idawati, I.; Sasongko, N.A.; Santoso, A.D.; Sani, A.W.; Apriyanto, H.; Boceng, A. Life cycle assessment of cocoa farming sustainability by implementing compound fertilizer. GJESM 2024, 10, 837–856. [Google Scholar]

- Sureau, S.; Lohest, F.; Van Mol, J.; Bauler, T.; Achten, W.M.J. Participation in S-LCA: A Methodological Proposal Applied to Belgian Alternative Food Chains (Part 1). Resources 2019, 8, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisfeldt, F.; Ciroth, A. PSILCA—A Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment Database. Documentation 2020. Available online: https://psilca.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PSILCA_documentation_v3.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Benoit Norris, C.; Norris, G.A.; Azuero, L.; Pflueger, J. Creating Social Handprints: Method and Case Study in the Electronic Computer Manufacturing Industry. Resources 2019, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzoumanidis, I.; D’Eusanio, M.; Raggi, A.; Petti, L. Functional Unit Definition Criteria in Life Cycle Assessment and Social Life Cycle Assessment: A Discussion. In Perspectives on Social LCA; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham-Agyekum, E.K.; Wongnaa, C.A.; Kwapong, N.A.; Boansi, D.; Ankuyi, F.; Prah, S.; Andivi Bakang, J.E.; Okorley, E.L.; Laten, E. Impact of children’s appropriate work participation in cocoa farms on household welfare: Evidence from Ghana. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Labour. Child Labor and Forced Labor Reports (Cote D’Ivoire). 2024. Available online: https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/cote-divoire (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- de Buhr, E.; Gordon, E. Bitter Sweets: Prevalence of Forced Labour and Child Labour in the Cocoa Sectors of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, Tulane University & Walk Free Foundation. 2018, pp. 28–30. Available online: https://cdn.walkfree.org/content/uploads/2020/10/06164346/Cocoa-Report_181016_V15-FNL_digital.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- US Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report: Côte D’Ivoire. 2024. Available online: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/cote-divoire/ (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- US Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report: Ghana. 2024. Available online: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/ghana/ (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Waarts, Y.; Kiewisch, M. Balancing the Living Income Challenge. Towards a Multi-Actor Approach to Achieving a Living Income for Cocoa Farmers. 2021. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/557364 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Wageindicator.org. Minimum Wage—Cote D’Ivoire, Agriculture Sector. 2024. Available online: https://wageindicator.org/salary/minimum-wage/ivory-coast (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Wageindicator.org. Minimum Wage—Ghana. 2024. Available online: https://wageindicator.org/salary/minimum-wage/ghana (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- International Labour Organization (ILOSTAT). Trade Union Density Rate (%). Annual 2019. Available online: https://rshiny.ilo.org/dataexplorer25/?lang=en&id=ILR_TUMT_NOC_RT_A (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- International Labour Organization (ILOSTAT). Mean Weekly Hours Worked per Employed Person by Sex, Age, and Economic Activity—Annual. 2023. Available online: https://rshiny.ilo.org/dataexplorer21/?lang=en&id=HOW_TEMP_SEX_AGE_ECO_NB_A (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Ghana Statistical Service. Population 15 Years and Older by Migration Status, Major Industry, Sex, and Type of Locality 2023. Available online: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/Thematic%20Report%20on%20Migration_09032022.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Bros, C.; Desdoigts, A.; Kouadio, H. Land Tenure Insecurity as an Investment Incentive: The Case of Migrant Cocoa Farmers and Settlers in Ivory Coast. J. Afr. Econ. 2019, 28, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The Ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): Overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.; Vasta, A.; Mancini, L.; Dewulf, J.; Rosenbaum, E. Social Life Cycle Assessment: State of the Art and Challenges for Supporting Product Policies; EUR 27624; JRC99101; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Traverso, M.; Bell, L.; Saling, P.; Fontes, J. Towards social life cycle assessment: A quantitative product social impact assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, M.; Foluke Quist-Wessel, P.M. Cocoa Production in West Africa, a Review and Analysis of Recent Developments. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2015, 74–75, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, D.; Maconachie, R. Children’s Work in West African Cocoa Production: Drivers, Contestations and Critical Reflections. In Children’s Work in African Agriculture; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Child Labour: Global Estimates 2020, Trends and the Road Forward. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@ipec/documents/publication/wcms_797515.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Villanueva, E.; Glorio-Paulet, P.; Giusti, M.M.; Sigurdson, G.T.; Yao, S.; Rodríguez-Saona, L.E. Screening for pesticide residues in cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) by portable infrared spectroscopy. Talanta 2023, 257, 124386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, P.; Adubofour, S.; Obodai, J.; Agyemang, F. The use of children in cocoa production in Sekyere South district in the Ashanti region, Ghana: Is this child labour or apprenticeship training? IJARIT 2018, 8, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walk Free Foundation. Bittersweets: Prevalence of Forced Labour and Child Labour in the Cocoa Sectors of Côte D’Ivoire and Ghana. 2018. Available online: https://www.cocoainitiative.org/sites/default/files/resources/Cocoa-Report_181004_V15-FNL_digital_0.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Perkiss, S.; Bernardi, C.; Dumay, J.; Haslam, J. A sticky chocolate problem: Impression management and counter accounts in the shaping of corporate image. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2021, 81, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veritè. Assessment of Forced Labor Risk in the Cocoa Sector of Côte D’Ivoire. 2019. Available online: https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Verite-Report-Forced-Labor-in-Cocoa-in-CDI.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Haughton, S.A. Global Report on Trafficking in Persons. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Global Security Studies; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrage, E.J.; Ewing, A.P. The Cocoa Industry and Child Labour. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2014, 18, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasell, J. From $1.90 to $2.15 a Day: The Updated International Poverty Line 2022. Published Online at OurWorldInData.org. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/from-1-90-to-2-15-a-day-the-updated-international-poverty-line (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Boysen, O.; Ferrari, E.; Nechifor, V.; Tillie, P. Earn a living? What the Côte d’Ivoire–Ghana cocoa living income differential might deliver on its promise. Food Policy 2023, 114, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.A.; Carodenuto, S. Stakeholder perspectives on cocoa’s living income differential and sustainability trade-offs in Ghana. World Dev. 2023, 165, 106201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, D. Towards Sustainable Cocoa Supply Chains: Regulatory Options for the EU. Fern, Tropenbos International, and the Fair Trade Advocacy Office. 2021. Available online: https://www.fern.org/fileadmin/uploads/fern/Documents/2019/Fern-sustainable-cocoa-supply-chains-report.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Kissi, E.A.; Herzig, C. Labor relations and working conditions of workers on smallholder cocoa farms in Ghana. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, S. Gender and Work in Global Value Chains: Capturing the Gains? Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boakye Dankwah, D.; Enu-Kwesi, F.; Koomson, F.; Ntiri, R.O.; Asmah, E.E. Interface between artisanal and small-scale mining and cocoa farming in the Wassa Amenfi East and West Districts of Ghana. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2024, 17, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amfo, B.; Aidoo, R.; Osei Mensah, J.; Maanikuu, P.M.I. Linkage between working conditions and wellbeing: Insight from migrant and native farmhands on Ghana’s cocoa farms. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessie, G.K. Effects of Migration on the Livelihood of Rural Households in the Kpando District of the Volta Region. Master’s Thesis, Department of Agricultural Extension, College of Basic and Applied Sciences, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Manoj, P.K.; Viswanath, V. Socio-economic conditions of migrant labourers: An empirical study in Kerala. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2015, 5, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dabiré, B.H.; Soumahoro, K.A. Migration and Inequality in the Burkina Faso–Côte d’Ivoire corridor. In The Palgrave Handbook of South-South Migration and Inequality; Crawley, H., Teye, J.K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations. National Labour Migration Policy, 2020–2024. 2024. Available online: https://cms.ug.edu.gh/sites/cms.ug.edu.gh/files/National%20Labour%20Migration%20Policy%20.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Kaba, J.S.; Otu-Nyanteh, A.; Abunyewa, A.A. The role of shade trees in influencing farmers’ adoption of cocoa agroforestry systems: Insight from Ghana’s semi-deciduous rain forest agroecological zone. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2020, 92, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, A.M.; Lewis, V.R.; Farrell, A.D.; Umaharan, P. Photochemical responses to light in sun and shade leaves of Theobroma cacao L. (West African Amelonado). Sci. Hortic. 2021, 276, 109747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sostizzo, T. Sustainable and Future-Oriented Cocoa Production in Ghana: Analysis of the Initiatives of two Swiss Chocolate Manufacturers. Afr. Technol. Devel. Forum J. 2017, 9, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, M.; van Soesbergen, A.; Arnell, A.P.; Scott, E. Patterns of (future) environmental risks from cocoa expansion and intensification in West Africa call for context-specific responses. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awafo, E.A.; Owusu, P.A. Energy and water mapping of the cocoa value chain in Ghana. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).