1. Introduction

Environmental damage is one of the main national issues in developing countries besides slow economic development. Unresolved poverty, social inequality, regional disparities, and ecological damage occur due to the excessive exploitation of natural resources, and the dependence on food, energy, finance, and technology [

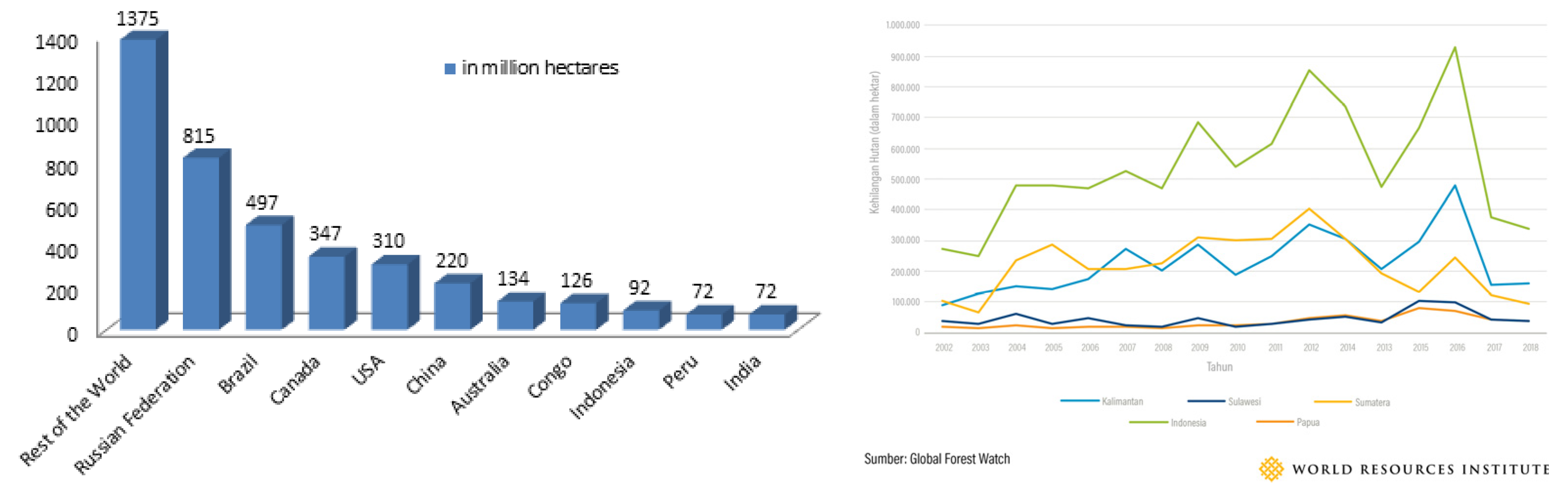

1]. Moreover, deforestation and forest degradation are the major leading causes of global warming, being responsible for around 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions, which makes the loss of forests a major issue for climate change. As

Figure 1 shows, in some countries–for example, Indonesia and Brazil, deforestation and forest degradation are the primary sources of national greenhouse gas emissions [

2].

The irresponsible mining practice in Indonesia has resulted in deforestation and forest degradation, which has damaged forests and ecosystems. Most of the mining practices in Indonesia relate to surface mining, whereby, the company often converts forest into a mining site [

3]. Compared with the low compliance of reclamation obligation, this is often the cause of deforestation and degradation. Mining permits in Indonesia have reached 11 million hectares, of which, 4.5 million hectares are forest areas. Indonesia experienced the greatest damage to tropical forests due to the mining industry, contributing to 58.2 percent of the total deforestation [

4].

Mineral and coal mining often increases soil density, erosion, sedimentation, landslides, disruption of flora and fauna, and disruption of public health, which leads to microclimate change [

5]. Meanwhile, the post-mining impacts have resulted in land morphology, topography, and landscape changes (the formation of landscapes on the post-mining sites is usually irregular, causing steep holes, and mounds of land that used heavy dumps), after which, the land becomes unproductive and potentially vulnerable to avalanches [

6]. Undeniably, mining has a vital role in development by producing raw materials for industry, absorbing labor as a source of foreign exchange, and increasing local revenue. However, on the other hand, mining produces various adverse environmental impacts [

7]. Mining activities have a high risk of environmental damage and create environmental justice issues, which have become a global concern [

8]. Recent studies and analyses by Griscom et al. as shown in

Figure 2 [

9] estimate that stopping deforestation, restoring forests, and improving forestry practices are the most cost-effective ways to reduce 7 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, which is equivalent to the emissions of 1.5 billion cars [

10]. Therefore, reclamation must be completed on post-mining sites to restore the land’s function.

Reclamation forces mining companies to restore the caused environmental losses. Land reclamation aims to repair the damage to post-mining ecosystems by improving soil fertility and planting lands at the surface. Moreover, land reclamation seeks to make the land more productive. Thus, reclamation can produce more value for the environment and create a far better situation than post-mining conditions. A good reclamation policy is a great way to introduce a restorative approach to the environment and support the REDD+ framework (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation, plus the sustainable management of forests, and the conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks (REDD+), is an essential part of the global efforts to mitigate climate change). REDD+ is a mechanism developed by parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It creates a financial value for the carbon stored in forests by incentivizing developing countries to reduce emissions from forested lands and invest in low-carbon options for sustainable development; developing countries would receive results-based payments for results-based actions. REDD+ goes beyond simply deforestation and forest degradation and includes the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks.

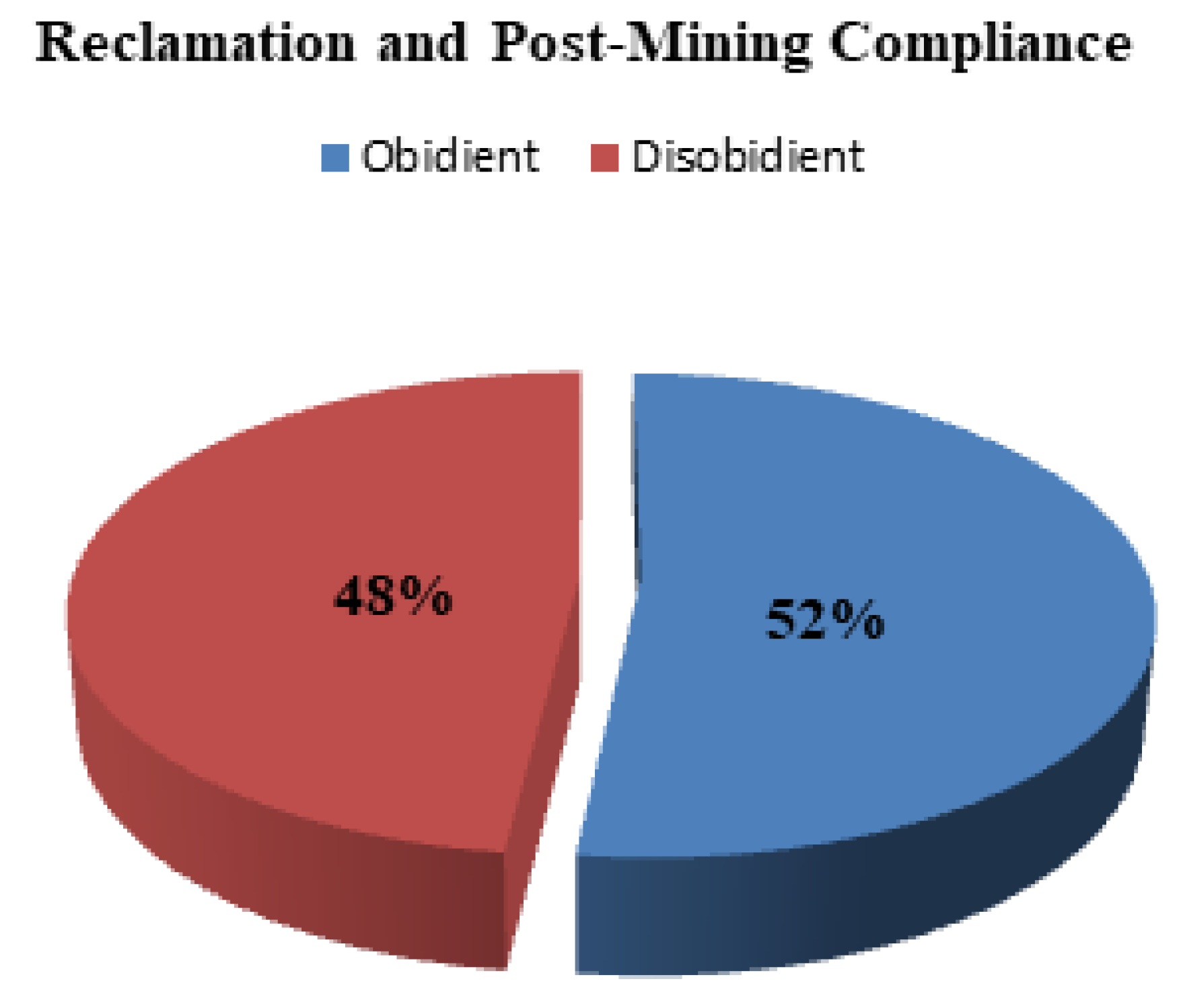

Before the Mining Law Reform, the major mining issue was the low levels of compliance by the License Holder (IUP) in conducting their reclamation and post-mining obligations [

11]. Moreover, as seen in

Figure 3, only 52 percent of the IUP holders fulfilled their obligation of the conditions in September 2017, meaning 48 percent of companies did not fulfill their reclamation and post-mining obligations [

12]. In general, the main problem was disobedience relating to their reclamation obligations.

Therefore, improving the compliance levels of the license holders through better regulations is required. Several Southeast Asian countries have introduced new mining laws to promote private-sector investment [

13]. For instance, Indonesia recently entered a new Environmental Framework after a Mining Law Reform via Act 3/2020 (The New Mining Act) and Act 11/2020 (The Job Creation Law). Reform is necessary to prevent further damage to the environment in mining areas. After mining activities are completed, the site must be reclaimed immediately to avoid other potential damages. Thus, this research focuses on analyzing the post-mining law reform in Indonesia and conceptualizing the idea of strengthening reclamation obligations in the Mining Act based on understanding high potential issues in reclamation obligations to prevent environmental and social damage.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Brief Historical Context on Mining Law in Indonesia

Before independence, Dutch colonials controlled the natural resources in Indonesia, including the minerals and mines. In 1989 through Staatblad 1989, and Number 214 promulgated Indische Mijn Wet (IMW) as Mijnordonantie, took effect from 1 May 1907, and regulates mining work safety (listed in Articles 365 to 612). Then, Mijnordonantie was revoked and updated to become Mijnordonantie 1930, which came into effect on 1 July 1930, thus, it no longer regulates the supervision of mining work safety, yet regulates itself in Mijn Politie Reglemen with Staablad 1930 Number 314.

After Indonesia’s independence, the founding father established mining management regulations by issuing Government Regulations in Lieu of Law (Perpu) 37/1960 on Mining, which ended the 1989 Indische Mijn Wet (IMW). Still in the same year, 1960, the Government also issued the Perpu 44/1960 on Oil and Natural Gas. In addition, Act 5/1960, which relates to the Fundamental of Agrarian Regulations (UUPA), also implicitly regulates mining. In this era, the mining sector implemented a concession system, which gave companies mining rights and control of the land.

To accelerate economic development, Perpu 37/1960 was revoked and replaced with a new fundamental mining law: Act 11/1967 on Fundamental Mining Provisions, which came into effect on 2 December 1967. After the promulgation of this law, the legality of mining exploitation consisted of various forms of licenses, namely, the Mining Authority (KP), Contract of Work (KK), Contract of Work for Coal Mining Business (PKP2B), Regional Mining Permit (SIPD) for industrial minerals or group C minerals, and the People’s Mining Permit.

Forty-two years later, on 12 January 2009, the Parliament passed Act 4/2009 on Mineral and Coal Mining. The emergence of this law was a landmark that shifted three essential elements concerning mining law: the rule of law, the control of the state, and the legal relationship between the state and miners. Since the promulgation of this law, the legality of mining concessions has only been in permit forms, such as IUP, IUPK, and IPR.

This licensing instrument is important because it places the government in a controlling position, different from contracts/agreements, which sets the government in an equal position with the mining companies. In addition, the licensing function is repressive. Permits can function as instruments to address environmental problems, whereby the state can obligate a business that obtains an environmental permit to carry out countermeasures for pollution or damage arising from its business activities.

On 12 May 2020, the House of Representatives passed the Bill of the new Mining Law. As of 10 June 2020, President Joko Widodo signed and passed Act No. 3/2020 as a revision of Act No. 4/2009 on Mineral and Coal Mining. Instead of fixing the issues faced by the old law, the new Mining Law removed the limit on the size of mining operations and allows for two automatic permit extensions of 20 years each. In addition, it effectively provides miners with bigger concessions and longer contracts, while with fewer environmental obligations due to the latest policy in Indonesia opting towards promoting EODB (Ease of Doing Business); hence, the 2020 Mining Act Revision and The Job Creation Law were enacted to loosen the requirements and obligations for business permits, including mining companies, despite the opposition from civil societies and environmental activists. Thus, aside from new regulation, the 2020 Mining Act Revision has not yet resolved the old legal issues related to permits, reclamation, protection of affected communities, and sanctions.

3.2. New Law, Old Challenges

The environmental ethics of used-oriented policy on natural resources in Indonesia is still morally debatable today [

16,

17]. The policy framework on sustainable resources should be within the understanding of harmony, balance, and sustainability of environmental functions [

18]. Disruption of ecological functions can result in discontinued development. A sustainable environment is a goal in natural resources management to guarantee land use without reducing future environmental quality. As part of the environment, natural resources are “

all objects, powers, circumstances, functions of nature and living things, which are the results of natural processes, both in biological and non-biological, renewable and non-renewable”. This concept distinguishes natural resources from biological, non-biological, renewable, and non-renewable resources. Thus, coal, as a mining product, is a non-renewable and non-biological resource. Furthermore, it is undeniable that coal provides many benefits to human life. Therefore, humans must continuously maintain coal availability through appropriate and integrated management.

The utility of natural resources is regulated by Article 33 (3) of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, “The earth, water, and natural resources contained therein are controlled by the state and used for the greatest prosperity of the people”. The mandate of Article 33 (3) contains the maximum principle as the ground principle reflected in the word “greatest”. The purpose of Article 33 (3) in the Constitution is to limit State control, reflected in terms “for the greatest prosperity of the people”, which implies covering the entire generation of Indonesians. The exploitation of natural resources, generally at an early stage, is interpreted from an economic perspective through, merely, an economic approach. Then, modern policy should use natural resources beyond economic approaches by using the non-economic approach as a principle, which is inherent in sustainable management [

19].

Jennifer McKay and Balbir Bhasin argue that ‘the mining industry in Indonesia is poised for a major reform effort necessary to sustain foreign direct investment and rescue the industry from serious decline’ [

20]. However, our primary concerns are the land’s morphological changes and topography, the remaining untreated excavation holes, and the environment’s carrying capacity, which is damaged, such as polluted water and infertile soil. Furthermore, abandoning reclamation on ex-mining sites is irresponsible, and affects Indonesia’s environment, economy, and, more often, the people’s social aspect. The unrestored ex-mining sites create many conflicts between locals and mining companies. Many of the local communities on the mining sites are affected by environmental damage, often making them confront the company responsible, which creates more social conflicts and legal battles.

As the evidence shows, excavation holes in ex-mining sites have resulted in massive casualties over the years. From 2014–2018, JATAM (Mining Advocacy Network) recorded 140 victims, who died from drowning in ex-mining excavation holes that were left untreated. The excavation holes result from non-reclamation mining activities and have taken casualties in 12 provinces in Indonesia, with 3033 holes from coal mining that are without any attempt of restoration [

21].

Furthermore, the 2020 Mining Act Revision does not address continuous conflicts between the mining company and local people, such as land rights between the company and indigenous tribes, social conflict, and human rights violations (Jaringan Advokasi Tambang (The Mining Advocacy Network) assessed that most of all the mining companies that enter a region are always followed by conflicts between local communities, companies, and the government). A researcher from JATAM, Ki Bagus Hadikusuma, recorded 71 conflicts in the mining sector during 2014–2019. The conflict occurred between the local people who refused the application for a mining business permit by the company and the government. The case occurred in a land area of 925,748 hectares. Most conflicts occurred in the province of East Kalimantan (14 cases), followed by East Java (8 cases), and Central Sulawesi (9 cases). The conflict was mainly related to gold and coal mines. Furthermore, in 2019 alone, JATAM recorded several cases of criminal law misconduct related to mining activities, with two cases of an alleged assault that resulted in death, and four intimidations by thugs, allegedly, ordered by the owner of the mining company. The most criminal activities and attacks occurred in East Kalimantan and Central Java, followed by Bangka Belitung, Maluku, East Java, North Sumatra, West Sumatra, and South Kalimantan [

22].

3.3. The Shifting Authority, Power, and Affairs in Coal Mining Practices

The 1945 Constitution is the source of the Government’s authority and power in environmental control. Article 33 (3) of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia only acknowledges the state’s power over energy if used for the greatest prosperity of the people. Jeremy Bentham’s view on justice and ethics influences Article 33 (3) of the Constitution, so the State, which has the ultimate control over energy, is burdened by the obligation to provide for the people owing to their duty as a welfare state. However, quite the contrary is true, based on the analysis of the Indonesian Mining Act by Gandataruna and Haymon, who studied five significant elements of the legislation, their research found that the Indonesian Mining Act was unlikely to result in a mining industry that provides the maximum benefit to the Indonesian people [

23]. The impact of mineral and coal extraction is often localized rather than national or global [

24]. Even after the power struggle from colonialism, the founding fathers agreed upon a constitutional obligation of the State to control and utilize the national resources for the maximum prosperity of the people.

From a political perspective, the goal of using natural resources for socioeconomic development was stagnant until 1967, when Soeharto came to power with the New Order regime and introduced policies that supported a significant mining industry expansion. However, the combined effect of the financial crisis and domestic political unrest from 1997 until 1998 interrupted this process. Therefore, in 2009, the enactment of the Mining Act brought hope for the people, although, in practice, mineral and coal mining activities created further disputes. For example, the conflict in North Maluku Province between the Sawai and Tobelo Dalam Tribe and PT. Weda Bay Nickel and PT. Tekindo Energy. In Central Sulawesi, a dispute arose between the Podi Villagers v PT. Arthaindo Jaya Abadi. Furthermore, in West Sumbawa, the tension between the Tongo Sejorong Villagers and PT Newmont Nusa Tenggara arose due to the local suffering from deforestation and water pollution. The decline in democracy [

25] makes it more urgent that the Government takes a big step toward reforming the Mining Act, to ensure that mining companies comply with reclamation obligations based on the success criteria of restoration.

The Environment Law should be the umbrella for other environment-related laws, either via biological or non-biological natural resources (NR). To understand the practice of coal mining in Indonesia, it is essential to cover the authority that manages the natural resources. Environmental management involves general investigation, exploration, feasibility studies, construction, mining, processing and refining, transportation and sales, and post-mining activities. For integrated policing, therefore, all of the entire stages of activities in mining should also contain a principle of sustainability.

Authority, powers, and governmental affairs are three critical aspects of the thought process of administrative policymaking. Authority can be interpreted as the right or obligation to conduct one or several management functions, such as creating regulation, planning, organizing, managing, and supervising a particular object by the government. Moreover, Cheema and Rondinelli argued that it is more precise to use the term “authority” to interpret the government’s rights to manage natural resources [

26]. In contrast, Hans Antlov uses “power” instead of “authority” [

27]. Authority is one of the core conceptions in Global Administrative Law to enforce good governance values [

28]. Authority, known as formal power, comes from the legislative (given by law) or executive administration (government affairs, according to Art 9 (2) of Act 23/2014, is divided into three parts: absolute affairs, concurrent affairs, and general affairs. Absolute affairs are governmental affairs that are fully the authority of the Central Government, which includes foreign policy, defense, security, justice, national monetary, fiscal, and religious. Subsequently, Art 9 (3) regulates that concurrent affairs are governmental affairs, which are divided between the Central Government and Regional (local) Government. The regional authority consists of mandatory and preferred government affairs. Furthermore, mandatory affairs consist of basic services and non-basic services).

In the case of the authority to issue mining permits, before Act 23/2014 on regional governments, most mining permits were issued by the district government. This authority has conditioned the local heads to become “small kings” in their area. With this authority, the issuance of mining permits was considered from economic values rather than sustainable values, which created further damage [

29].

Since 2009, there have been several changes to the administration of mining permits in Indonesia. During 2009–2014, the issuance of mining permits fell under the Regent’s authority; during 2014–2020, the policy was revised so that the issuance of mining permits fell under the Governor’s authority.

After issuing the 2020 Mining Act Revision and the Job Creation Law, the authority shifted to a central authority, in this case, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources and the Ministry of Investment. The change in authority from the regional to the central government certainly caused complexity in the management of mining licenses.

The transfer of management and licensing authority to the central government has implications for the regional authorities, which is an absolute priority. Thus, the question remains whether delegating authority and licensing to the central government was the right decision. Until now, the implementation of the previous Mining Act, which divided power over the control of minerals and coal to the provinces, has been substandard in supervising the mineral and coal mining business activities. Therefore, existing mining businesses are increasingly causing environmental damage due to discrepancies in the issuing of Mining Business Permits (IUP).

Applying a centralized authority within the mining industry, as regulated by the Mining Act Revision, has removed the authority of regional governments to issue Mining Business Permits (IUP). The return to a centralized system is regulated in the provisions of Article 35 in the Mining Act Revision, which reads: “Mining business is carried out based on a Business Permit from the Central Government”. Revision of the Mining Act also provides the central government with the authority to decide production volumes, sales volumes, and prices for metal minerals, certain types of non-metallic minerals or coal, and issuing permits for mining businesses. Regarding licensing, the types of licenses in the new law are divided into three types, namely, “Mining Business Permits (IUP), Special Mining Business Permits (IUPK), and People’s Mining Permits (IPR)”.

3.4. Parameter of Reclamation Policy

The essence of the rule of law is law enforcement beyond other affairs. Therefore, legislation is a significant part of creating the law for the nation. Legislation is one of the policy instruments (

beleids instrument) essential to resolve and anticipate societal problems; even today, the legislation aims to direct people towards a better life [

30]. Law, as a tool of social control, also translates to preventing the government from acting arbitrarily. Similarly, in natural resources, the right to regulate, manage, and supervise natural resources is provided by the Constitution as the ground law in legal substance (In Hans Kelsen’s

Stufenbau des Rechts Theory, the ground law (

grundwet) is used to describe the highest form of written law. However, it is important to notice that a ground law (

grundwet) is different than the ground norm (

grundnorms), which is the basis regulating norms that reflect the way of the people. For example, in Indonesia, the ground norm is Pancasila, which contains the five belief values of the Indonesian people: the all-powerful God; humanitarian and human rights; national unity; the teaching of deliberation and peace; the social justice for all). With Article 33 (3) of the 1945 Constitution, the laws and regulations for implementing control over natural resources should reflect the spirit of the welfare state (welfare state is the main utility theory in implementing the state’s control over natural resources and energy. The modern rule of law is not only to protect the people but also to provide for social welfare. Therefore, the state through the government should actively play a role in creating jobs, financial security, food, and security for their society) [

31]. Controlling natural resources also raises the responsibility for sustainable management, balanced by the roles and functions of all stakeholders, including NGOs and universities/research institutions. In addition, communities have roles that complement each other to create a sustainable environment in implementing mining law [

32]. One aspect of the ideas of constitutional content is the legal policy of environmental management. Constitutional protection of individual environmental rights has two reasons. First, it becomes a strong basis for individuals to defend the environment from any damage that affects them. Second, it is the basis for demanding that the state realize these rights [

33].

The Environmental Act regulates Control Activity carried out in the environmental conservation framework, including prevention, mitigation, and recovery. The recovery referred to in Article 54 of the Environmental Act as a form of control has the same meaning as the reclamation and post-mining activities referred to in the Mining Act. Article 1, Number 26 of the Mining Act, stipulates that reclamation is carried out throughout the mining stages to organize, restore, and improve the environment’s and ecosystem’s quality. While post-mining activities in Article 1, Number 27 are defined as planned, systematic, and continuing after the mining activities end to restore the natural environment and social functions, according to local conditions in all mining areas.

Mining companies should conduct reclamation on unused post-mining land inside and outside ex-mining areas. Land outside an ex-mining area includes (1) landfill; (2) stockpiling of raw materials; (3) transportation roads; (4) plant/processing/refining installation; (5) offices and housing; (6) ports/docks. Article 1, Point 26 of the Mining Act regulates the scope of reclamation activities, starting from exploration, land clearing, topsoil excavation and overburden, coal extraction, land management, revegetation, preparation of nurseries, and maintenance and evaluation of activities.

For the reclamation and post-mining activities to be performed successfully, several steps must be followed, from the approval of the reclamation plan and post-mining plan to the proposed changes. These stages are regulated by the Post-Mining Regulation, which requires permission from the Minister, Governor, or Regent/Mayor. At a later stage, holders of mining licenses should provide reclamation insurance funds and post-mining insurance funds.

Figure 4 shows how the government sets policies for each IUP and IUPK holder to place funds as reclamation and post-mining insurance.

The fund placement is needed as insurance for each IUP and IUPK holder to restore ex-mining land following the designation agreed upon by the stakeholders in the context of sustainable development. The release or disbursement of funds is under the post-mining plan. The fund is placed annually through time deposits at government banks. The amount of post-mining insurance is calculated based on several costs as seen in the

Table 1 below.

The deposit is valid until all reclamation activities are declared completed by the Governor. Disbursement of deposits and their interest is conducted after the reclamation activities are completed, based on the reclamation plan approved and accepted by the Governor.

3.5. Reforming the Reclamation Obligation

Reclamation, usually known as land reclamation, is an attempt to repair and restore damages resulting from mining activities and to restore ecological function. Article 100 (1) of the Mining Act regulates the obligation of IUP and IUPK holders to provide reclamation funds. Subsequently, in

Section 2, the Minister, Governor, or Regent/Mayor can determine a third party to perform reclamation and post-mining. Meanwhile, the Reclamation and Post-Mining Regulation regulates that the holder of a mining permit must perform reclamation and post-mining without giving space to third parties to take action for reclamation and post-mining. A third party is only permitted to be appointed to perform reclamation and post-mining if the restoration result conducted by the permit holder does not meet the criteria of successful reclamation, which is stipulated by Article 33 of Reclamation and Post-Mining Regulation and reads: “

If based on the evaluation of the reclamation implementation report shows the reclamation result does not meet the criteria of success, Minister, Governor, or the Regent/Mayor by their authority may determine a third party to perform part or all of the reclamation activities using a reclamation fund placement”. The disharmony regarding the role of third parties in reclamation can be seen in Article 100 of the Mining Act; by placing a reclamation and post-mining insurance fund, the permit holders can transfer their reclamation obligation to a third party appointed by the government. In comparison, the Reclamation and Post-Mining Regulation stipulates that reclamation and post-mining must be performed by the IUP and IUPK holders, which the government, then, evaluates before bringing in a third party.

Referring to Article 7 (1) of Law 12/2011 on lawmaking (Lawmaking Act), the meaning of legislation is: “written law that contains general binding norms and is established or stipulated by state institutions or an authorized official through the procedures stipulated in the Laws and Regulations”. In other words, the Mining Act must guide any mineral and coal mining legislation. Furthermore, based on Article 7 of the Lawmaking Act, the order of laws and regulations follows the hierarchy as seen in

Figure 5.

The legal force of the law follows the hierarchy (See

Figure 5). In other words, based on the legislation order, Act 4/2009 as Revised in Act 3/2020 (Mining Act) has a higher force than Government Regulation No. 78/2010 (Reclamation and Post-Mining Regulation). Therefore, Government Regulation No. 78/2010 should not be conflicted with the Mining Act as the superior law.

The issue is that Government Regulation No. 78/2010 is arguably more effective in forcing reclamation by rigorously regulating the reclamation and post-mining obligatory for IUP and IUPK holders. Normative construction using natural resources, especially minerals and coal, shows diverse arrangements with different formulations. Management of natural resources, which generally includes planning, organizing, and actualizing, can be viewed as the stakeholders’ aspirations. Activities in management can be used to perform legal interpretation, legal reasoning, and rational arguments for the formulations of each law.

The results of legal interpretation, reasoning, and rational-legal arguments can be used to harmonize the law. However, harmonizing the law will not automatically result in legal unification, because harmonious legal conditions are not normatively followed by a balanced implementation. Implementation of legal actions, legal relations, and legal consequences will also be unified if the stakeholders of natural resource management have the same perception of the normative aspects of legal harmonization. The same perception of harmonious law is the basis for realizing legal unification.

The Legislative Draft of the Environmental Act states that the conflict between natural resources and the environment is a conflict that has the characteristics of confronting frontally between those who have access to resources and more substantial power, with those who are access-disabled or at least have access to resources and less power. Environmental conflicts are generally caused by exploitation, which ignores the interests and rights of the community, justice, and environmental principles. As mentioned before, one of the causes of natural resource and environmental conflicts is the disharmony between the laws and regulations, both vertically and horizontally. Article 5 of the Lawmaking Act states that one of the principles that became a milestone in the creation of legislation is “the principle of clarity”. In the elucidation of the Lawmaking Act, the principle of clarity in the formulation of the law means that each legislation must fulfill the technical requirements of the preparation of legislation, through a systematic choice of words or terms, which are straightforward and easy to understand, to prevent any misinterpretation in their implementation. The principle of clarity in the formulation can be applied to reform the reclamation obligatory in the Mining Act and ensure that reclamation and post-mining become a non-transferable obligation to the third party. The reformation of the Mining Act, specifically on reclamation and post-mining obligations, must be performed to prevent the occurrence of multiple interpretations of the obligations and liability in reclamation and post-mining.

The first key formulation that needs to change in the Mining Act is to reinforce the essence of “obligation” for IUP and IUPK holders to perform reclamation and post-mining under supervision, as in the Environmental Act. Furthermore, Article 100 (2) should be changed as follows: “

The Minister, Governor or Regent/Mayor by their authority can determine the third party to help the IUP/IUPK holder in the reclamation and post-mining using the placement fund as referred to in paragraph (1), only if the reclamation result does not meet the criteria of success”. With this formulation, in essence, the placement of the reclamation fund by the company does not eliminate the company’s obligation to carry out reclamation and post-mining activities with the procedures as seen in

Figure 6.

The second key formulation is to implement a mandatory condition of placing the reclamation guarantees fund as a requirement for approval of the mining plans and budgets (the RKAB) and Clean and Clear (CnC) Certification. Nearly half of the mining companies are not paying into mandatory reclamation and post-mining funds managed by the government due to a series of blind spots in the Indonesian regulatory framework. Among these loopholes is a compulsory deposit the company must make to the government for reclamation and post-mining guarantees fund to obtain mining permits. However, the deposit is not a prerequisite for approval of their mining plans and budgets (the RKAB). Furthermore, it is the RKAB rather than the mining permits, which allows the mining companies to begin operating. Only six percent have deposited reclamation and post-mining funds with the government, according to the State Auditing Agency (BPK), and only twenty-one percent have deposited the reclamation fund. Furthermore, the government mandates a “clean and clear” certification for mining companies to confirm that they meet all legal requirements. However, carrying out reclamation obligations is not a requirement for obtaining the CnC certification. Consequently, many mining permit holders had secured a CnC certification without depositing reclamation and post-mining funds. It has enabled mining companies to continue to operate without having to rehabilitate their concessions, with no disincentives for non-compliance.

Strengthening the reclamation obligation is a step toward stronger law enforcement. In the current state, the Mining Law allows the company to transfer the reclamation responsibility to the third party, as long as they place the fund. A reform of the law will force the companies or permit holders to be liable for reclamation. Therefore, if they do not comply with the regulations, there will be no question as to the liability burden and the sanction can be imposed properly.