1. Introduction

Challenges of the changing socio-economic environment require new ways of thinking and acting, even at the regional level. Regions must meet the needs of modern society and the global market and find their own opportunities for developing their smartness (seeking a goal, knowledge grounding, networking, participation, learning, innovativeness, creativity, intelligence, etc. [

1,

2,

3]). Small countries (characterized by small population, geographical area and the level of created Gross Domestic Product), such as Lithuania, are usually taken as one unit in various analyses and research. However, every region “has specific assets, unique capabilities, and industrial policies that make it different from other regions” ([

4], p. 1509). Regions of a small country must find their own field of competitive advantage to participate in a global market; therefore, they look for accesses to additional resources, try non-traditional ways of solving socio-economic problems, identify its strengths and use them to find a potential of innovativeness to become smart regions. Existing differences among regions inside a small country require adjusted and modified methods and instruments to assess its innovativeness (the resolution of RIS absorptive capacity and the change of it during a particular period) to identify tendencies and possibilities of development in the future.

Innovative activities (as the substantial element of a smart region’s performance) are based on two main capacities: absorptive capacity (the ability to attract good ideas or information from elsewhere) and development capacity (the ability to exploit absorbed knowledge to create and develop new products or services) [

5]. Absorptive capacity is considered the primary presumption for innovativeness of a regional innovation system (RIS), where all participants (individuals or institutions, innovators or followers) act like a network and possess appropriate abilities to operate, maintain and develop themselves as well as the entire system. On the basis of the Systems Theory, an enabled regional innovation system becomes a frame for developing its capacity to absorb knowledge and to seek innovativeness and competitiveness, while increasing its smartness. Our analysis and results can be the starting point and encourage other researchers for the development of future quantitative and qualitative studies on the resolution and development of absorptive capacity, identifying specifics (social, economical, institutional, political, legal, infrastructural, etc.) of RISs in small countries.

Consequently, the purpose of this paper is to present the methodological approach for assessing the RIS's absorptive capacity and to substantiate it by giving evidences from a smart region of a small country. The aims are as follows: (1) to describe the concept of a smart region in the context of the innovation system; (2) to present the concept of absorptive capacity in the context of the regional innovation system; (3) to present a methodological approach for assessing absorptive capacity in a smart region in a small country; and (4) to explain the expression and development of absorptive capacity in a smart region (Kaunas County) of a small country (Lithuania).

The mixed-method approach (combining qualitative and quantitative research strategies) was used to substantiate the presented methodological access. The following methods have been applied: literature analysis, statistical analysis, multiple criteria Simple Additive Weighting (SAW) method, semi-structured interview with experts, and content analysis. The research on assessing the absorptive capacity of Lithuanian regional innovation system included the sub-national unit–Kaunas County (smart region) (in accordance with the EU NUTS classification, i.e., small country’s regions—counties, assigned to NUTS III regions [

6]).

After an introduction on the main concepts of absorptive capacity development in a smart region (

Section 2) and the presentation of methodological approach (

Section 3), we will present and explain the results of the research in a particular smart region (

Section 4). Then we will conclude with some reflections and suggestions for further research (

Section 5).

2. Assessing the Absorptive Capacity in a Regional Innovation System: The Approach of Smartness

2.1. The Concept of a Smart Region in the Context of Innovation Systems

Smartness of the city, region or the state is becoming an important topic of the research in different fields. The term smart has been transferred from technological to social sciences. However, in social sciences the substance of smart is quite different and more complex compared to that in the technological sciences. There is still no common understanding as to what really “smartness” means when applied to the social context. Moreover, the dominating part of publications about smart regions stems not from research but from practice. A good example of the situation is the Global or European Forums on Smart Regions or Cities where good practices from around the globe are presented with very little theoretical interpretation, if at all. Such situation clearly calls for theoretical research in the field.

The concept of the smart region has been discussed in the scientific literature from quite different perspectives: a Triple-Helix model which emphasizes smart regions as a process of cultural reconstruction underpinned by policy, academic leadership, and corporate strategy in their guidance; human capital as the most important component [

7]; modern information technology being as a core of any smart city [

8], the area where culture is the medium for operating interlinked economics, society and environment [

2]; and others. For example, smartness of a region or a city is similar to the knowledge region [

9]. Others consider smart regions as places generating spatial intelligence and innovation, based on sensors, embedded devices, large data sets, and real time information and response [

10]. It is also some kind of an urban innovation ecosystem, a living laboratory, acting as an agent of change. Quite a different view of the smart region is given by some other authors. The smart region can be understood as a place that provides inspiration, shares culture, knowledge, and life, a region that motivates its inhabitants to create and flourish in their own lives [

11]. It is an admired region, a vessel to intelligence, but ultimately an incubator of empowered spaces. Finally, smartness of the region relates to its capacity to leverage its human, structural, and relational capital, and its ability to integrate diverse actors in the region’s innovation practice [

12].

We consider the smart region, first of all, as a social system. A human being becomes the priority here: technical/digital systems are the products of a human being and, therefore, smartness is primarily applicable to (a) human being(s). Consequently, the main starting point in analyzing the term

smart is a human being and the quality

smart is, first of all, attributed to a human being. This is exactly the same if applied to innovation instead of smartness. The development of a talent is the process of activity but not assimilation, reception. In order to develop

smart individuals, they have to be provided with

smart environments. In order to develop

innovative individuals, they have to be provided with

innovative environments. The aspect of a particular environment is relevant for the development of absorptive capacity because of individual innovative activities in an RIS. The ecosystem approach fits best for understanding what kind of environment is to be empowering change, learning, all forms of innovation and dynamic entrepreneurial discovery processes. The conceptual model of the smart region as a social system is presented in

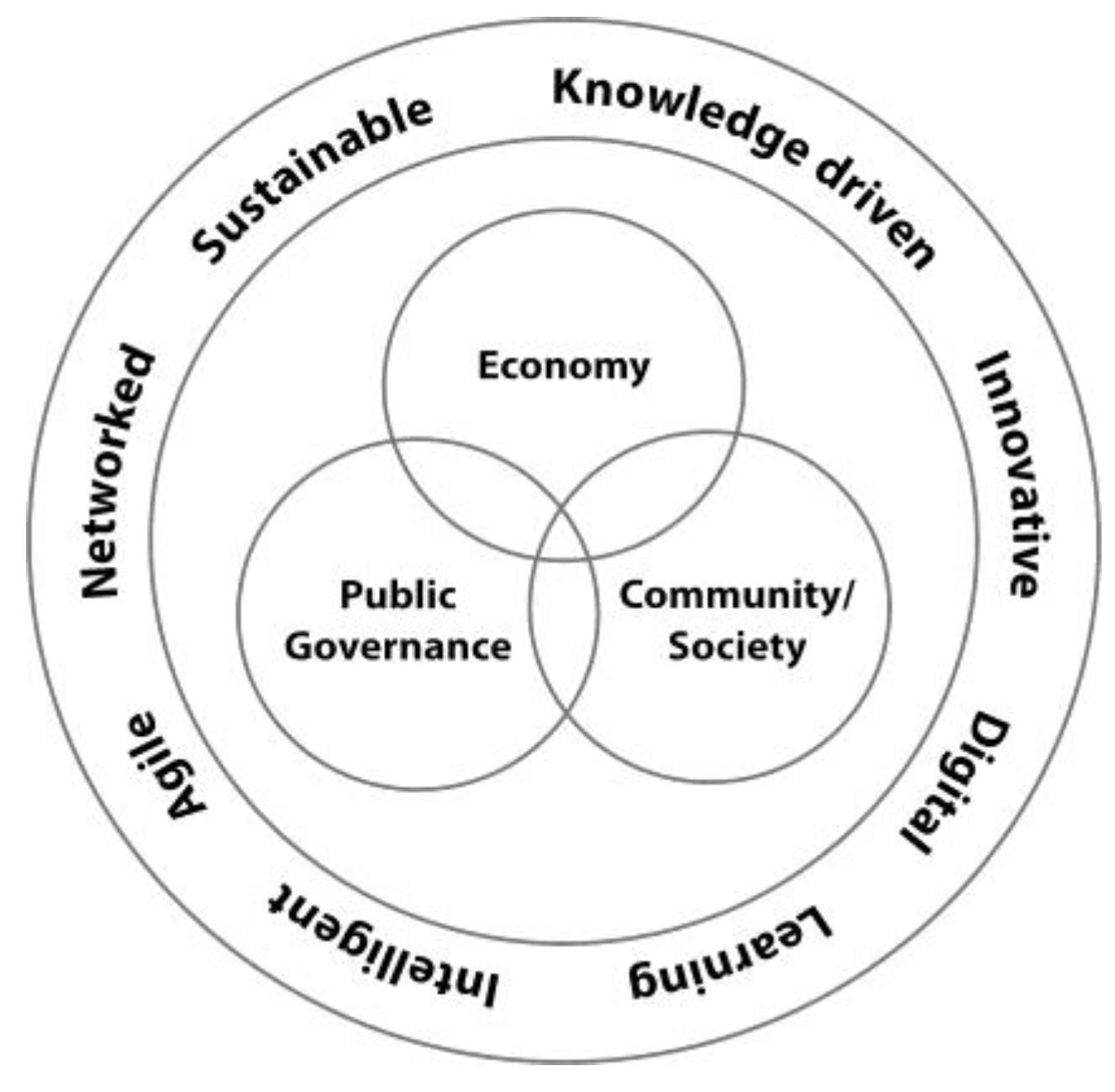

Figure 1.

The concept of the smart region may be understood as an integral construct composed of different theoretical concepts and approaches. Probably the most important are the theories and concepts of knowledge management, intelligence, the learning organization, sustainability, innovation systems, business systems, agility, networking, and digital social systems. All of them have their unique as well as overlapping qualities that could be considered as dimensions of smartness.

Basically, the smart region is an open social system that has to be interconnected with variety of knowledge, competence, resource and other types of networks. Being networked with the environment is one of important preconditions to being competitive and possessing specific resources for the development. Otherwise, environment can be the stimulus to become networked. Intelligence is the art of monitoring weak signals which tell us whether the region is on the right track or not. It is about being well informed about all aspects important for the development and problem solving, understanding the future challenges and their consequences. The Intelligent Community Forum [

14] characterizes intelligent communities by five indicators: broadband connectivity (vital to economic growth); knowledge workforce (creating economic value); digital inclusion (providing skills training and promoting the benefits of being included into the broadband economy); innovation (which produces job growth in modern economies and invests in e-government programs); marketing and advocacy (sharing the story with the world and building a new vision of the community from within). Each of these five features of intelligent community can be enabled only in a favorable environment (social, cultural, political, economic, legal, technological), providing needed space, tools, and measures.

Lifelong learning at an individual and collective/organizational level, learning partnerships, learning communities, innovation, continuing development, and the quality of sustainable life describe the learning region. Knowledge-driven development based on creation of all types of innovation, supported by individual and collective learning and enabling technologies is a solid platform for the development of the smart region. Economy, public governance and community/society could be characterized as the core sub-systems of the smart region.

A well-functioning system of entrepreneurship is an important precondition for becoming a smart region. Such system of entrepreneurship has much in common with the innovation system even if the structure differs. The smart system of entrepreneurship means empowering different types of the development capital: intellectual, social, economic, institutional, and physical.

Hence the smart region is a complex social system with effective dynamic entrepreneurial processes uniting key stakeholders (participants of the RIS) around a shared vision, is able to envisage the features critical for the region and its environment, to which they quickly and inventively react by adjusting to this environment with adequate decisions as well as using it to attain the developmental goals.

2.2. The Concept of Absorptive Capacity in a Regional Innovation System

The conception of the smart region is followed by some peculiarities related to knowledge management: intelligence, learning, networking, seeking for effectiveness and appropriate decision-making. All these activities are based on a particular “know-how” which needs specific knowledge. Absorptive capacity (the ability to attract and absorb external ideas and information) and development capacity (the ability to create new knowledge and exploit it for producing new products and services) are two essential capacities needed to implement this “know-how” at individual as well as organizational and regional levels. The interdependence among knowledge created through absorptive capacity activities knowledge management and the learning process has been already confirmed [

15,

16] as the main construct defining organizational (and regional) learning mechanisms. Therefore, in this process all actors (individuals and organizations/institutions) of a regional innovation system should be involved because of their different potential and possibilities to contribute purposefully.

Various authors provided slightly different definitions of the absorptive capacity. A traditional concept of absorptive capacity is perceived as a capacity to recognize (evaluate) external knowledge, to assimilate and apply it [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, this approach, based on the organization (innovative unit) as an analysis unit, did not disclose details of organizational processes, emphasize active role of the organization in the process of acquiring knowledge. Later, this concept was supplemented and revealed by the dimension of knowledge acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation processes [

18,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Absorptive capacity was considered as a capacity to learn and solve problems (especially at an individual level), in compliance with a position that the learning process is a joint process getting the best results if the object of that learning process is interlinked with previous knowledge [

17,

18,

28,

29]. However, this access directly correlates to the supplemented concept and is not considered as a separate conception. All these three concepts derived from each other and had no essential differences. Therefore, in this stage, the absorptive capacity (a construct depending on a chosen direction of activities) was determined as a capacity: to identify and evaluate external knowledge by learning and using existing experience and knowledge, to assimilate external knowledge; to give them particular forms appropriate to the context; to use them for solving problems of various levels by guarantying innovative processes and competitive advantage. Various authors [

17,

18,

30,

31,

32] suggest to keep the absorptive capacity both as a critical factor of organizational innovative processes, which generates organizational resources to create own innovations, and the source of potential competitive advantage in dynamic markets. Other authors [

18,

33] explain absorptive capacity as a capacity to identify, anchor, transform and exploit external knowledge for developing internal competencies. However, this concept did not reveal all possible elements of absorptive capacity’s usability.

The development of the conception of absorptive capacity was not finished. During the last ten years not only individual scientists but even organizations became involved in the scientific debates, presenting new approaches to this concept. One of such organizations, NESTA (formerly National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts, now—NESTA (charity)), is an innovation charity organization which helps people and organizations bring great ideas and innovate, publishes political guidelines and studies of various groups of scientists, analyses various aspects of promoting innovations. This organization published a study [

34] presenting an updated approach: a capacity to innovate must be initiated and started with the absorptive capacity (capacity to access, anchor and diffuse knowledge) and continued with the development capacity (capacity to create and exploit knowledge). Seeking to reveal necessary assumptions for innovative activities, it was decided to undertake detailed research based on this modern concept of absorptive capacity. It consists of three main components:

the capacity to access external knowledge and innovation;

the capacity to anchor knowledge from people, institutions and firms;

the capacity to diffuse new innovation and knowledge in the wider economy [

5,

34,

35].

Absorptive capacity can be analyzed not only vertically (through the three levels of individuals, organizations and regions) but also horizontally (with respect to the covered areas), as the absorptive capacity depends not only on investment (R&D costs) but also on the prior knowledge embodied in human resources (basis of their knowledge and skills), the organization (lies in the organizational structure, management practices) and its interaction with the environment (practice with external partners (other business companies, universities, public institutions, etc.). This complexity strongly affects processes of absorptive capacity’s development in a regional innovation system, consisting of different type organizations and various connections among them.

The systematic concept of absorptive capacity in a regional innovation system is still the subject of scientific debates. The regional dimension of absorptive capacity has been analyzed in various studies [

16,

30,

36,

37,

38,

39]. We substantiate the concept of the regional innovation system by the System Theory. The system is a group of interrelated units (components) interacting, communicating with each other for a common goal, when each element makes impact on the total systems’ functioning [

40]. Thus, a regional innovation system (RIS) is perceived as a network of cooperation among different institutions (public and private formal organizations) based on organizational and institutional arrangements, relationships and contacts, contributing to knowledge access, anchoring and diffusion processes. Results of a particular RIS depend on its actors and their interactions. Therefore, the analysis of the absorptive capacity in a regional innovation system is based on the theoretical approach of the well-known Triple Helix model [

41,

42,

43]. For a better identification of institutional (organizational) actors in an RIS of a small country, the Triple Helix model was adapted and main components were identified as follows:

Academy (includes various educational institutions: universities as well as colleges, vocational and continuing training institutions);

Business (covers various sectors, i.e., industry, trade, service and financial sectors);

Government (governmental authorities formulating and implementing innovation policy—ministries, municipalities, tax agencies, etc.);

Other institutions (includes connecting institutions, clusters, public laboratories, technology transfer organizations, patent offices, training, development organizations, innovation (academic and business) support institutions, state and university research institutes and institutions, science and technology parks, integrated science, study and business centers (valleys), educational information technology centers, agencies and innovation centers, business incubators, business centers, etc. [

44,

45,

46,

47].

However, it must be emphasized that such a system is acting in a particular environment affected by dependent and independent political and legal, social and cultural, economic, infrastructural, etc. factors, having direct and indirect effect on the final result of the RIS’s performance. Since the analysis of the multidimensional effect of the RIS environment on its results should be the object of a separate research, this article does not detail and emphasize this aspect.

Employing the adapted and applied Triple Helix model we could analyze the absorptive capacity taking into account the structure of an RIS as well as interactions among different actors. All the actors of an RIS are independent (on internal acting and decision-making) as well as interdependent (being influenced by the environment and affecting others); therefore, the structure and the environment of an RIS can become crucial for the analysis of absorptive capacity. Consequently, we made a decision to create the methodological approach to assess absorptive capacity of an RIS in a small country based on a case study (by choosing a particular small country and an RIS).

4. Results of Absorptive Capacity of Kaunas County (a Smart Region) in Lithuania (a Small Country)

All three components of absorptive capacity (knowledge access, anchoring and diffusion) must be strengthened for the development of a region’s innovativeness and smartness. Therefore, results of the empirical research are given according to the components. It must be emphasized that the influence of external factors (such as economic, social, cultural, political, infrastructural phenomena) are not analyzed; however, it is assumed that the environmental changes could have an indirect (positive as well as a negative) impact on the final results of this quantitative research.

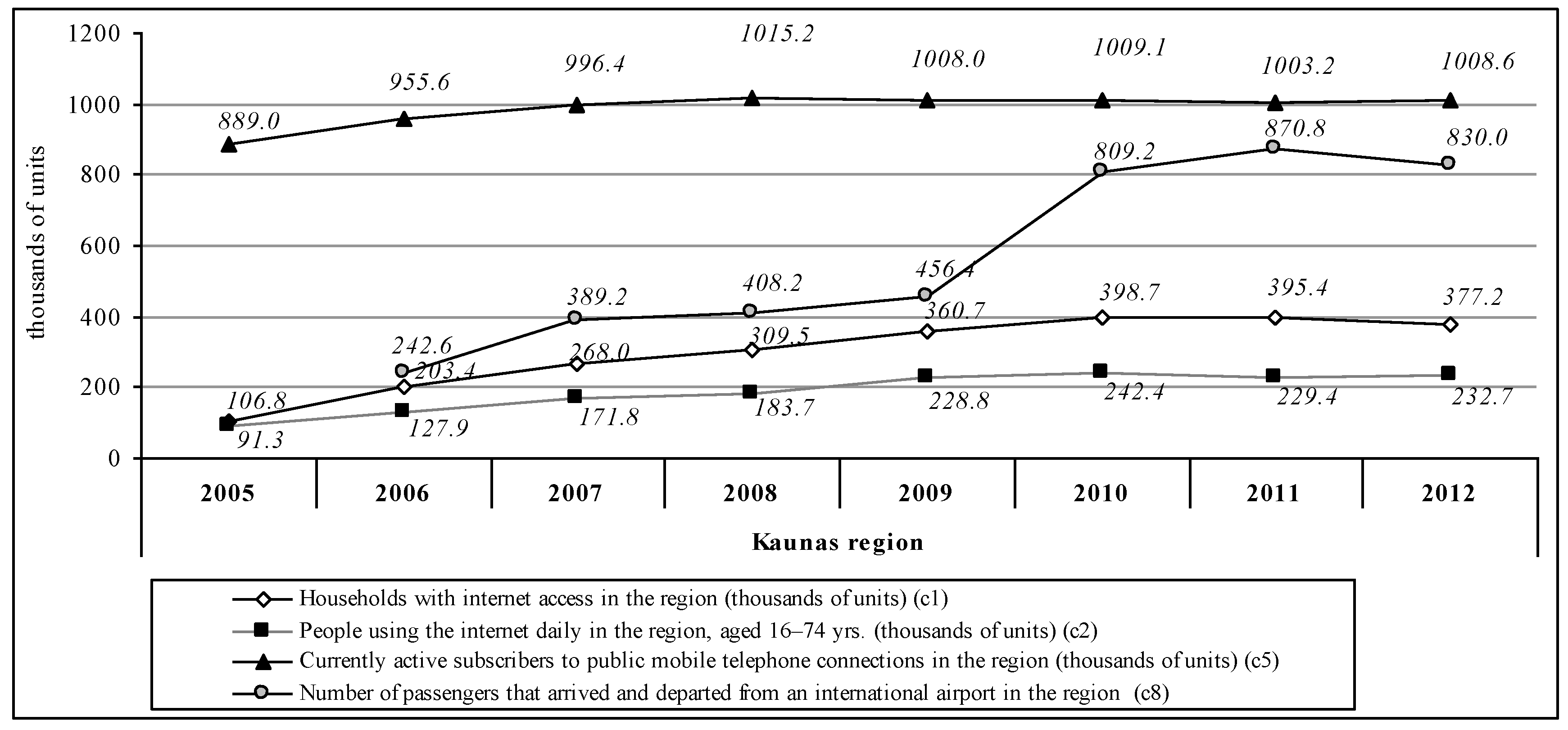

As it was mentioned, innovative individuals (organizations) have to be provided with innovative environments. It is very important due to knowledge access. Some indicators present the dynamics of the situation in Kaunas region (

Figure 2).

A significant increase of passengers of Kaunas regional airport (2010–2012) is more concerned with the increase in international emigration (during the 3-year period, more than 29,000 residents of Kaunas region left). The increase of this indicator makes a negative impact on regional innovativeness, while growing other three indicators have a positive influence on knowledge access. A high, stable trend of the usage of the ICT (Internet and mobile connection) was observed in Kaunas region. It presents growing possibilities for regional participants in the RIS to access global knowledge.

During research interviews, experts gave some explanations on the positive change of knowledge access: For today the communication is not difficult. And it does not matter where you are (E3). The meaning of geographical location becomes not important any more. Moreover, interpersonal communication with foreigners or possibilities to participate in international projects (networking) is indicated as the most important instruments for increasing the global knowledge access: A lot of things depend on interpersonal human contacts (E1). Global knowledge? <…> It comes through communication, through projects (E6); How do we get knowledge? International projects <...> and international groups (E4); We have international projects where we really solve problems with partners (E2); The source—we work with science, <…> with scientists we implement common projects. The particular experience comes from them (E10); Scientific journals and participation in scientific conferences are the main sources of knowledge (E8). However, experts remind, that innovations are not self-produced phenomena: A modern individual thinks that everything will appear quickly, everything is on the Internet—I will just take it and the problem is solved… But it is not true. People themselves must understand that it can’t be done “in five minutes”; they do not get the knowledge even in a university to create the product quickly (E9). Besides, experts emphasize a significant problem of international emigration from the region: Demographics and our globality are main challenges (E6); Sometimes we do not have such equipment like stronger western countries do. And we have to leave… Not everybody leaves. <…> Those who stay, do not ascend quick (E3). It can become the primary reason for the creation of “a vicious circle” of problems: graduates from regional science and study institutions leave the region because of the lack of positions (in the business) supply; it is very difficult to establish new business because of the lack of specialists who would be able to initiate it; weak business has no capacity to invest in scientific research and R&D; ineligible science has less potential for R&D as well as for preparation of new high quality specialists who could be able to offer new ideas for business in the future.

It is highly connected with other indicators (number of various institutions possible to engage in innovative activities) of knowledge access in an RIS. It must be emphasized that the concentration of institutions in Kaunas region is quite dense (in comparison with other Lithuanian regions). The number of universities and colleges in Kaunas region remained stable during the entire period (Kaunas region has 5 universities and 6 colleges), though the number of other organizations (service enterprises as well as organizations engaged in educational activities and in financial and insurance activities) decreased by 6.24 percent in 2012. This change (according to experts’ insights) is mostly explained by the higher number of enterprises affected by economic difficulties due to a decrease in production demand, a more cautious attitude towards prospects for the Lithuanian economy on the part of businesses, and a decrease in society’s confidence in the manufacturing and service sectors.

So, the question is how high qualified specialists could contribute to the knowledge absorption process. First, the critical mass of specialists (graduates from educational institutions) ready for innovative activities must be created (

Figure 3):

It is needed <…> to have the team and human potential (E8); The critical mass is needed (E1). It should be mentioned that the number of university graduates is declining in contrast to the number of graduates of colleges and vocational schools in Kaunas region. This is a new national trend affected by the changing requirements of the labor market, national education policy objectives, and the demographical changes of the society. Still, there is a large percentage of workers holding a higher education diploma (Bachelor’s, Master’s, or Doctoral degree). Businesses and other organizations in Kaunas region should be prepared to employ such specialists and even provide them an opportunity to work on R&D activities (it is reflected by the indicator of employees involved in R&D); nevertheless, this percentage is quite low even if it was growing in 2010–2012:

People are the propulsion. Not those programs, not loud slogans, but people having the potential, being curious (E4); There must be the translator and the receiver, therefore, there should be more receivers (E8); The attitude in Kaunas <…> is more positive in some cases, than in some provincial universities (E1).Second, this issue is indisputably connected with the knowledge anchoring process and creation of the smart social system:

To be able to realize those ideas, the infrastructure is needed (E8) (the connection between the smart individuals and their environment was already mentioned in the

Section 1). Therefore, Kaunas RIS (especially business and science institutions) makes efforts on providing new job positions for high quality specialists. First, more positions of interesting job (corresponding to graduates’ qualifications) are tried to be provided:

The salary should be competitive for sure. <…> We try to create the interest. For those, who look for challenges, <…> non-standard job (E10); Our specialists are young. All conditions are created for going “up the career ladder” (E9). We try to organize open competitions. <…> It could raise the competition (E6). The job is interesting, it is communication with people. <…> It is constantly spinning in the young, changing, creative environment (E5).Moreover, participants of Kaunas RIS use even national (political and financial) instruments for recovery of already emigrated high qualified specialists: experts evaluate it as an advantage (

If you would look to the statistics how many have defended Doctoral Dissertations, the majority of them stay in a university. <…> It is important to recover. <…> There are few scientists who came back (E8)) as well as useful for the education of new generation of specialists (

Figure 4). Sometimes, businesses (especially SMEs) are not able to help an RIS as a whole (they are more interested in organizational preservation); therefore, state and municipal authorities provide support and funding for developing qualified human resources in regions.

There is a very noticeable trend of the decrease in state (national) and municipal (local) investments for training specialists in 2008–2012. It is connected with declining budgets’ income (due to economic crisis) and more. This corresponds to national-level policy that complies with the position of employers: to train less specialists with university education, to pay more attention on non-university higher education institutions (colleges and vocational schools) with a greater focus on cooperation with the business sector. Therefore, academic institutions started to look for another funding: national or even international programs and projects, research services for partners in the business and public sectors: We do understand that there is no ordering. <…> If there is not available here, then it is needed to look for elsewhere (E7); We try <…> to apply science in studies and practice. <…> Those needs arise in close collaboration (E8); We have agreements with sectors, <…> with municipality, <…> with separate enterprises (starting with governmental ones, <…> and finishing with small ones, but willing to cooperate) (E6). Another important point is that the share of regional R&D expenditures in the structure of the regional GDP is quite stable but lower than in 2005. Despite of the clear vision of this need, some experts emphasize, that [still businesses do not agree to finance particular scientific units. <…> Finally, the business is too weak to finance scientific research (E1); There is no system at our place. <…> However, even it is declared <…> (those indicators, strategies), it does not exist (E2). Despite of that, the FDI acquisition in Kaunas region has been fostered by efforts of the region’s center, the city of Kaunas; these funds were raised by joint venture and foreign capital companies operating in such fields as manufacturing, real estate, wholesale and retail trade, financial intermediation activities, etc. This occurred because of a stronger market and RIS participants’ intensive activities in looking for international partners and innovative solutions—smart behavior. However, all activities must come to some kind of results (outcomes) which could be spread in the RIS and outside.

Knowledge diffusion process is quite a complex process. Usually it is connected to such difficult activities as establishing innovative enterprises, patenting, creation of value added, etc. (

Figure 5).

A smart region (social system) has to create a high concentration of innovative companies in the region. The number of innovative companies per 1000 residents in Kaunas region is declining because it has been suffering from the loss of a great number of emigrated residents and the economic recession. Besides, [start-ups are created. <…> And the situation is getting better. <…> Nevertheless, scientists still are unable to evaluate their presented ideas critically, and not all “start-ups” will be successful (E1); If only seeking for the profit in any case, that it would be cheaper, faster and the quality is not important, then the innovations are in a poor situation (E4).

The other indicators, i.e., the number of patent applications, patents issued, and registered designs, do not exceed 30 in Kaunas region during the entire period analyzed, which means that the products developed by its RIS participants were not sufficiently original or the patent was refused on account of patenting procedures. Registering intellectual property is a time-consuming, demanding effort and an expensive process; therefore, not all inventions or ideas are patented or registered. Experts give more evidences on this slow process in Kaunas region: Patenting is a very expensive pleasure (E5); Nowadays, they often apply for a patent abroad because of a very simple reason: foreign institutions have more money for that and they are more well-known (E1); The biggest problem is the question of property: to whom this intellectual property belongs (E4); Not in Lithuania but in the European Union, especially in the USA, there are many very abstract patents, <…> and they are very needed to investigate, <…> where is our space (E10); When you talk with scientists, they look at a Lithuanian patent very distrustfully because nobody will protect it. They look more to the European one (E9). One of the experts gives a different attitude on patenting and protection of intellectual property: It is a huge question because Lithuania has no common politics, common strategy and regulation on those issues. <…> But if your invention was created using money of tax payers (and it does not matter if it’s Lithuanian or European), it should have the really open access. I would say just in the case of radical innovations <…> in my opinion, it could be some way of licensing (E2).

However, when analyzing the change of value added indicators in the region, some trends can be identified. A sharp decrease of regional value added at production costs was registered in 2008 (from 2.757,956 m Euros in 2007 to 1.737,898 m Euros in 2008; the decrease was 36.99 percent) (it could be linked to the global crisis and its impact on regional capacity). Later (2010–2012), this indicator constantly increased (13.9, 24.7 and 29.8 percent respectively). According to the data, a direct correlation between individually created and regional value added was observed (the same constant tendency can be noticed starting in 2009). Some experts link the positive change of the situation with the specifics of Lithuanian specialists: People are forced to understand that it is needed to invest to the renewal (E10). We are hardworking and wishful. <…> If there is a wish, those who work consistently reach their results no inferior on the global scale (E3). Majority of leaders whose new generation is coming <…> “chew” and introduce those innovations <…> both in organization of management and technologies (E10); The only one “natural resource” in Lithuania is the people (E9).

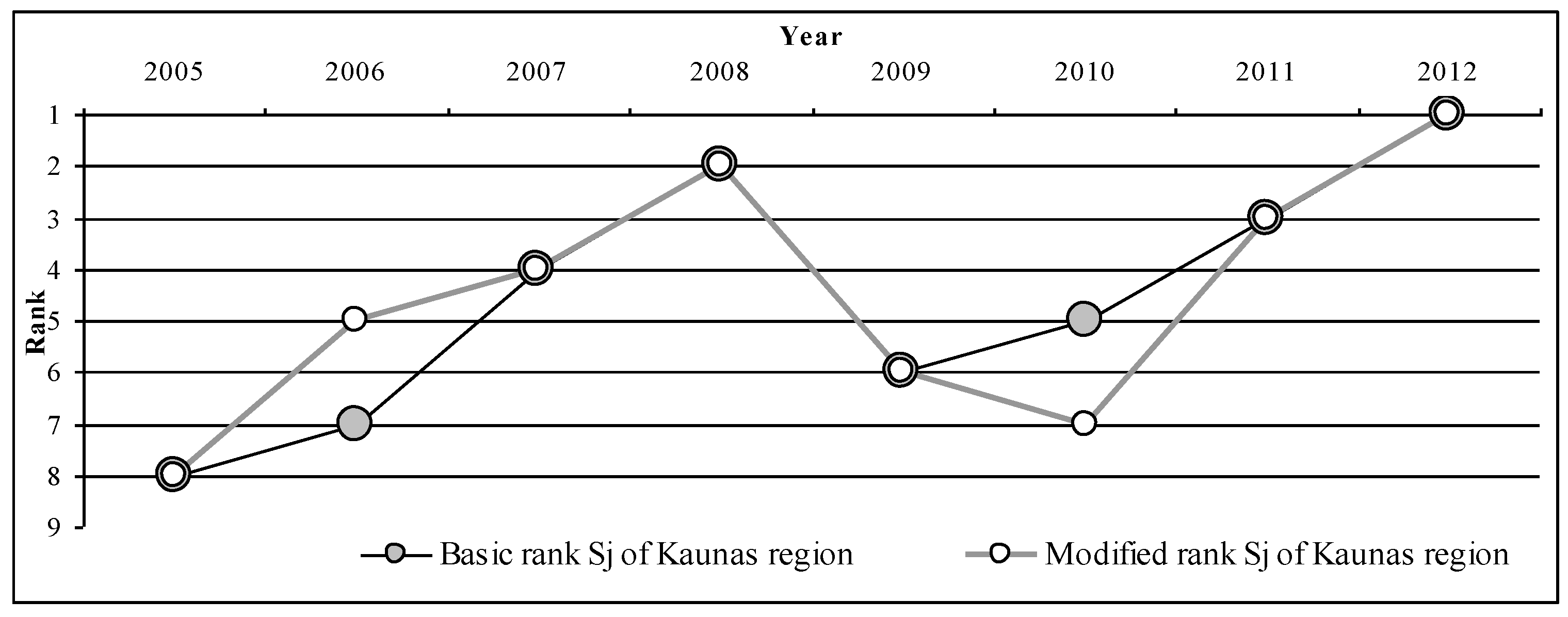

There are some indicators of regional absorptive capacity increasing, others—declining during the analyzed period in 2005–2012. Indicators were expressed in different measurement units (it could be measured by units, million Euros, percentage, etc.). However, the multiple criteria SAW method enabled the authors to assess the change of the common absorptive capacity situation during the period and to identify the worst and the best year for knowledge absorption in Kaunas region. A basic and modified list of indicators included, respectively, just indicators with available estimates for all the period and all indicators with estimates (available for particular year). The basic and modified indicator sums (obtained in normalized weighted matrices of data) (

Table 1) made it possible to assign a ranking for each year of the period analyzed (

Figure 6): the higher value for S

j, the better the situation (1 indicates the best situation and 8 the worst).

It was observed that the worst state knowledge absorption in Kaunas region occurred during 2005–2006 and 2008–2009 (irrespective of the type of calculation used). It might be connected with the influence of environment and its impact on regional innovative activities (lower development level in the region in 2005–2006 and the global economic crisis and its effects after 2008). The year 2008 was nearly the peak of knowledge absorption before the worldwide economic recession. The period of 2011–2012 was a period that showed the consistent recovery of knowledge absorption. That gives the evidence, that this region has the internal potential to survive challenges, crises and even to recover fast.

A smart region must have smart people understanding problems and having a vision on how they can be solved. The Kaunas regional innovation system acts as a smart region—it is ready for challenges and changes, because of its big potential for human resources (

Figure 3), quite dense network of institutions able to work on R&D (number of universities, enterprises, introducing innovations), the profile of graduates of regional universities (specializing in natural sciences, medical sciences, technological sciences, agricultural sciences, social sciences, etc.) forming the specialization of regional companies and attractiveness for investments.

There can be given some insights of experts from Kaunas region on the future possibilities to develop the regional smartness and strengthen the regional absorptive capacity. Kaunas region is quite strong on human potential: There are excellent specialists, both practitioners and scientists (E8); More specialists than elsewhere (E9); Many students graduating. <…> Labor force, the price <…> are more favorable (E10). The basis for a smart region, smart people, have already concentrated in Kaunas region. What more could be done? The answer is in the enabling of elements of a smart region (community (society), economy, and public governance) and their interaction. The strengthening of cross-sectorial trust and collaboration is needed despite of slightly different life styles (E5). There should be more networking among universities and collaboration with the business sector: More <…> connecting institutions (science with business) are needed (E3). There are some threats, if we will not develop or not unite. <…> A need for unitization is not a fashion but rather a real demand (E6). Some political decisions on economics and real actions are needed as well: Investments and new enterprises are needed. <…> There is the lack of favorable policy of banks, <…> no credit lines. <…> There are too little of such measures (E7). The smartness requires a clear vision of the country’s orientation and continuing national innovation policy: It is good that <…> various measures in Lithuania are exploited (including measures of the EU and the Ministry of Economics of the Republic of Lithuania, helping business, start-ups, and small enterprises). It is very good that all those measures exist (E10). It is needed to organize more visits and present those production enterprises. <…> There will be no too much of promotion of Lithuania, for sure (E9). A very important role of government is not to disturb by regulations (E5). The clearly defined long-term strategy and consistent implementation of it would be very helpful (E10). All those guidelines should be reflected in Kaunas regional strategic documents and plans for the development as well as strategic decisions on solving problems with the existing potential of the smart social system in the region.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

A smart region is a complex social system uniting participants of an RIS with effective dynamic entrepreneurial processes, attaining the developmental goals, critically envisaging features of the region and its environment, quickly and inventively reacting and making adequate decisions. A smart region begins firstly from individuals ready for innovative activities, decisions, performance, willing to learn and develop their competencies and having enough abilities of fast reaction to internal and external stimulus. Such individuals can be united by bigger structures (organizations) as active and passive actors (promoting the development of individuals as well as creating appropriate conditions for their development). Such organizations are linked to each other as units of a network where all participants are significant actors of a particular innovation system surrounded by other systems (regional, national, transnational). All participants of an RIS play a specific role in seeking common goals, maintaining the functioning of the system in a particular environment, but at the same time have the freedom in making decisions and creating preconditions for their own knowledge absorption.

Analysis of absorptive capacity in a smart region of a small country requires a non-traditional access because of its specifics (institutional, social, cultural, economic, political, infrastructural, etc.). There are many research works presenting possible methodological ways to make a quantitative and/or qualitative analysis of a particular RIS’s absorptive capacity. However, institutional features reflected by the usage of the Triple Helix model require updated and/or adapted methodological approaches, explaining specifics of a particular small country, and helping to identify the expression of smartness in a particular region. This can be done not only by assessing the common situation of all components of absorptive capacity (quantitative approach). All facts and trends should have explanations (qualitative approach) coming from the perception of an RIS’s participants as the input (beginning) and output (result) source of expression of absorptive capacity. The expression of knowledge access, anchoring and diffusion is the main source enabling to evaluate the situation of an RIS and to provide guidelines for the regional development.

The quantitative analysis of absorptive capacity in Kaunas region as a smart region in a small country (Lithuania) showed few tendencies: (1) Access to knowledge has been strengthened by the growing inhabitants’ access to the ICT in the region (frequent usage of the ICT meets the requirement of a smart society), but still it faces some challenges: decreasing funding of the education system in the region (which creates preconditions for the development of smart society) has the negative influence on its development level; (2) Knowledge anchoring can be characterized by a dual expression—even the region prepares a big number of high qualified specialists (precondition for the development of smart economy), it has little opportunities to retain and maintain those specialists in the region: only minority of investments are recovered by the returning added value, created in regional organizations, especially oriented to R&D activities (statement about the economy still developing to smartness); (3) Knowledge diffusion is affected by a small number of innovative enterprises directly involved in R&D activities (few possibilities to enable smart society in an underdeveloped environment) and sluggish patenting processes (reflects problems of a smart culture and economy). Taking into account the common trend of social, economic, infrastructural, and institutional indicators, the situation in Kaunas region during an 8-year period (to 2012) became more positive (best situation in 2012), what confirms the progress of the RIS’s participants (their efforts and willingness to develop). At the same time, it can be assumed about a positive impact and contribution of the RIS’s environment.

To sum up, Kaunas region meets some challenges making influence on the level of absorptive capacity. Those challenges can be identified as continuously declining funding for education, a large scale emigration, too few employees involved in R&D activities, a low number of intellectual property and innovative companies creating more added value in the region. At the same time, according to the results of the qualitative research, it can be stated that this region concentrates a huge potential of the smart society (highly qualified people willing and understanding the meaning of personal and organizational development) and smart business (with leaders and employees involved in knowledge absorption processes) with the plan for their development, using advantages of networking and collaboration within a regional innovation system and outside. Even the analyzed region (Kaunas region) of a small country (Lithuania) is still seeking to develop the regional smartness (due to the history of the development, surrounding context, impact of national and even transnational policies, etc.), the results of the development of absorptive capacity in a RIS shows the positive movement toward this goal. Stories of success encourages for changes within the system. Higher level of absorptive capacity encourages the innovativeness and motivates participants of the RIS to act with less fair and more trust, to build stronger individual and organizational relations and connections leading to a smart social system.

Therefore, the seeking for common goals of smartness could be encouraged by the active participation of all three components: (smart) society with already existing highly qualified and ready to develop specialists needed for innovative activities, (smart) business with a changing mindset and understanding the meaning of human resources development, inter-organizational trust building, meaning of networking and partnership, significant for survival and progress; and (smart) government with the clear vision of economically and socially strong and developed regions ready to become equal competitors in a global market, with specific tasks for scientific and educational institutions leading to better results of knowledge absorption).

The presented methodological approach to the assessment of the RIS’s absorptive capacity was applied for a particular smart region (Kaunas region) in a small country (Lithuania). The biggest limitation of this research was the lack of statistical data. Moreover, after 2012 majority of data started to be collected presenting the country as a whole, but not its regions separately. This reason can restrict future researches. However, the quantitative and qualitative approaches and methods can be applicable for the analysis of other regions in small or larger countries. The quantitative instrument (the list of indicators) must be reviewed before application to regions in larger countries. Some of quantitative indicators can lose the significance or, otherwise, additional indicators can be included to the general assessment of absorptive capacity and the expression of its components. However, the usage of the multiple criteria SAW method justified expectations of researchers as well as requirements of reliability and trustworthiness; hence, it is recommended to apply for future research of regional absorptive capacity (in small as well large countries). Qualitative research instruments must be reviewed before each research in a particular region or country, but the semi-structured interview is considered to be an appropriate method for the assessment of the factors influencing the expression of knowledge access, anchoring and diffusion on individual, organizational and regional level. It is a very significant part of the research revealing internal (individual) and environmental factors making the influence on the knowledge absorption (identifying factors of culture, reflecting smart society, economic and environment peculiarities).