Abstract

This paper explores the substantial effect that the critical understanding and techno-political consideration of data are having in some smart city strategies. Particularly, the paper presents some results of a comparative study of four cases of smart city transitions: Glasgow, Bristol, Barcelona, and Bilbao. Likewise, considering how relevant the city-regional path-dependency is in each territorial context, the paper will elucidate the notion of smart devolution as a key governance component that is enabling some cities to formulate their own smart city-regional governance policies and implement them by considering the role of the smart citizens as decision makers rather than mere data providers. The paper concludes by identifying an implicit smart city-regional governance strategy for each case based on the techno-politics of data and smart devolution.

1. Introduction: The Techno-Politics of Data

The politics of urban digital data are discussed infrequently in smart city events worldwide [1]. Consequently, the smart city technologies and initiatives are generally portrayed and positioned as technical, pragmatic, common-sensical, and non-ideological—that is, as rational interventions designed to improve social, economic, and governance systems. They are inherently politically and ideologically loaded in vision and application, reshaping in particular ways how cities are managed and regulated [2] (p. 17).

Given the context of hyper-connected societies [3], how can the politics of data be unpacked to be used actively to design and deliver effective public policy to tackle global urban sustainability issues? How can we design and implement open data platforms that will not only guarantee citizen engagement, privacy, and security, but also strike a new, broader balance between democracy, politics, and real-time public deliberation? How can we alter the data politics by considering citizens as decision-makers rather than data providers? [4].

Habermas argued that “smartness cannot be more technocratic than democratic” [5]. However, these days, the development of smart urban governance is being based increasingly on the conception that smart cities are merely systems of systems, systems of data, or systems of algorithms. The term ‘techno-politics’ thus illustrates that it is never possible to make clear distinctions between technology and politics [6]. Politics uses technical standards because they can be more effective than laws, at the same time that technical expertise is acquiring a political power that was not intended [7].

Hence, despite the abundant critical literature espousing a techno-deterministic view of smart cities [8,9,10,11,12,13], this article suggests that what is required for comparative purposes is a critical review of the smart city itself [14]. Meanwhile, what is needed for a more comprehensive democratic interpretation of the usage of data and a socially progressive policy agenda of smartness in cities and regions is a constructive approach [15,16,17]. By exploring the side effects of the hyper-connected societies [18], critical techno-politics views, such as those advocated by Morozov [3] and Harari [19], have gained momentum in criticising and altering the course of some on-going smart city initiatives. For Morozov [3], despite the plethora of technological solutions to social problems, the following key questions remained unanswered: “Who gets to implement data?” and “What kinds of politics of data do technological solutions smuggle through the back door?” Others, like Rossi [20] (p. 12), promulgate the urban governance perspective when arguing that the contemporary smart city cannot be reduced to the economic value generated by partnerships involving powerful public and private actors, such as multinational corporations and the state.

Another reason that the current interest in citizens’ participation and interaction is at the centre of the debate about smart cities is because too many times technological solutions have been proposed without considering needs and usability by citizens or the socio-technical misalignment within the city [21,22]. This paper elaborates on the idea that favourable conditions exist for a potential politics of progressive smart city policy agendas based on urban transformations driven by social innovation and experimentation [23,24,25]. Cities represent powerful places for detecting emerging processes and observing spontaneous urban transformations [26,27]. The technology-oriented pathways of smart cities offer still unexplored opportunities for experimenting [28,29].

Having said that, we should face the reality when Gartner predicts 1.6 billion connected devices will be hooked up to the larger smart city infrastructure by the end of 2016. As Harari [19] argues, “we are already becoming tiny chips inside a giant system that nobody really understands”. According to him, in the era of data, authority will shift from humans to computer algorithms.

From academia, urban studies have a long tradition of critically examining the interface between space and digital technologies, and information studies have targeted the city as one of its principal domains of study. However, narratives and practices around notions of ‘smartness’ have been largely absent [30]. This article aims to rethink the dominant technocratic and technology-centric smart city discourse—not by imagining cities beyond or before technologies, but by accepting that city-regions are already fundamentally shaped by networked and mobile ICTs and by acknowledging that city-regions will inevitably revolve around generating large amounts of data, which will lead to new governance strategies [31]. In reality, city-regions are much more complex, as the recent report by the European Commission [32] shows. They are shaped by a large variety of different actors and organisations with often conflicting positions. All this makes truly ‘smart’ city-regional governance exceedingly difficult, but at the same time a fascinating and rewarding scale for investigating the various meanings and usages of ‘smartness’ [33].

In order to provide qualitative, evidence-based comparatives of smart city-regional governance, this paper will examine research results obtained during fieldwork research conducted between September 2015 and June 2016 in four European city-regions [32,33,34], two in Spain—Bilbao and Barcelona—and two in the UK—Glasgow and Bristol. (In Section 2, further details about the research process, case-studies, and methodology will be provided).

This paper will first emphasise the transition of their smart city initiatives, especially regarding the techno-politics of data. Second, it will stress the increasingly substantial importance of a multi-level governance devolution scheme [35,36,37,38] by guaranteeing “smart” allocation of territorial autonomy and social sovereignty in owning, managing, and being responsible for financial and material resources for their smart city projects.

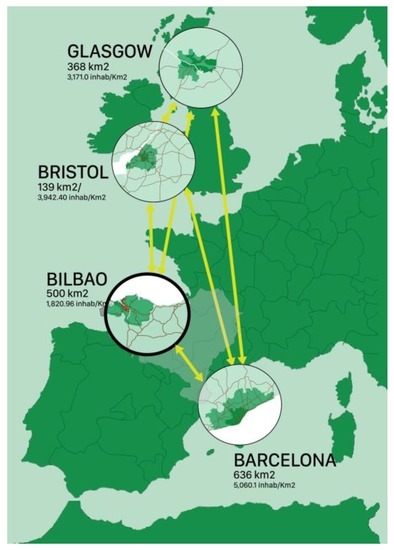

Hence, this paper examines smart transitions going on in comparatively in Glasgow, Bristol, Barcelona, and Bilbao by pointing out differences in their city-regional governance (See Figure 1). The analysed cases combine in a novel manner the three domains that, according to Kitchin [2], smart cities encompass: regulation and efficiency, economic development, and social innovation and civic engagement.

Figure 1.

Smart city-regional comparative study: Glasgow, Bristol, Barcelona, and Bilbao.

These aspects suggest the need to elaborate on the key component of the debate: what we mean when we talk about ‘smart citizens’. This article focusses on two critical factors of the ‘smartness’ in cities and regions to capture the way in which the ‘smart citizens’ discussion is taking place in the presented case studies. The first factor refers to the requirement for a techno-politics of data by providing transparent business and social models including a wide range of stakeholders in the decision-making process. The second factor suggests that a smarter use of technology and data are vital to the success of city-regional devolution processes, and vice versa.

2. Design: Comparative Study and Qualitative Fieldwork Research

On the one hand, the data discourse is transforming not only the way cities understand and, thus, implement their governance roles, but also how they should deal with techno-political issues [39,40]. On the other hand, the allocation of resources at the local level seems to be a pervasive trend for some city-regional governance issues, based on real institutional settings, which has been taking place unevenly in some European city-regions’ strategies [38]. In Europe, shifts in metropolitan policies are taking place regarding spatial development such as policentricity, competitiveness, or integrated development [34]. Previous research findings advocate that despite similarities between the main definitions of metropolitan city-regions, which refer to underlying concepts of city-regional cooperation and their relevance for spatial and economic development, metropolitan policies in the four cases have taken various forms and have focused on different governance instruments. As such, the comparison of two national cases, the UK and Spain, can thereby contribute to a better and more systemic understanding of the “smart city-region” beyond national perspectives and methodological nationalism.

Particularly, the UK has been facing this policy debate in an open and constructive manner by considering that city-regional economic and territorial scales should meet regionally diverse urban transformations, as the Brexit vote on 23 June 2016 clearly depicted [41]. Thus, the devolution debate has been entirely connected with smart strategies. With some remarkable differences, this has been the case in Glasgow and Bristol after both had been noted as leading cities in the smart policy field [42]. Likewise, in Spain, Bilbao, and Barcelona took diverse path dependency routes towards devolution, having different impacts on their smart policies and current evolution. The article, thus, will resonate with these differences and path dependencies.

In order to provide an evidence-based, empirical research comparison of case studies of smart city-regions, qualitative fieldwork research was conducted in four cases—Glasgow, Bristol, Barcelona, and Bilbao—from September 2015 until June 2016. This period of qualitative action research fieldwork was funded by the European Commission, Marie Curie Actions-MSCA-COFUND-2015-Regional Programmes under the Grant AYD-000-268. The host and beneficiary institutions and local partners of the fieldwork research were Bizkaia Talent [43] and Bilbao Metrópoli-30 [44]. Both are strategic institutions of the Biscay province in the Basque Country (Spain). Thus, the selection of the cases followed the funding institution’s, and the host and beneficiary institutions’, criteria. As such, the study aims to focus on the potential pervasive governance linkage between devolution and techno-politics of data in the way the two Spanish (Bilbao and Barcelona) and the two British (Glasgow and Bristol) cities implemented their current smart city strategies.

The research method employed was action-based research qualitative research by examining strategic and ethnographic factors in each location. This comparative study was based on triangulation techniques, such as interviews, policy paper analyses, and ethnographic research. As such, twenty interviews were carried out in each location. The aim of the fieldwork research was to cover the most diverse and heterogeneous range of stakeholders. Actually, this research design was based on the penta-helix framework [45] driven by multi-stakeholders’ interdependencies. Thus, instead of suggesting the triple-helix or quadruple-helix model, this article follows the penta-helix framework in order to capture the widest governance narrative to inform how each location has been carrying out its data and devolution policies and strategies. The broader picture that this research covered, the better and richer research outcomes could be achieved. The scientific principle leading this research and the penta-helix framework is based on the idea that stakeholders’ interdependencies and their socially- and culturally-rooted practices are as important as the data and technical knowledge itself. Indeed, the role of institutions seems to be strategically substantial in order to foster ecosystems of experimentation engaging not only the public sector, private sector, and academia, but also civic society and social entrepreneurs and/or activists. As the last type of stakeholder, social entrepreneurs and/or activities represented the initial spark in the ecosystem of urban experimentation by acting as brokers and assemblers [4]. Given the different configurations in each location, the interviews followed the same semi-structured form by interviewing policy-makers and civil servants (public sectors), practitioners (private sector), civic group representatives (civic society), academics (academia), and social entrepreneurs (change-makers). In this sense, despite the wide literature in the field of open innovation [46], as we are going to observe in the following sections, this comparative study emphasizes particular features in each location by comparing both ethnographic and strategic perspectives.

3. Results: Smart Citizens, from (Just) Data Providers to Decision-Makers in Glasgow, Bristol, Barcelona, and Bilbao

When Habermas [5] confronted technocratic and democratic smartness, he made it possible to generalise a category called ‘smart citizens’. However, could smartness be a possible answer based on Oström’s idea of the ‘commons’ [47,48] requiring a reconciliation between the conflicting interests of individualism and collectivity? Albeit, there is a shift that the mainstream literature has pervasively addressed. For a full understanding of the techno-political implications of the term ‘smart citizens’ and to put into practice the whole capacities of citizens as the main driver in urban transformations, this article underlines the requirement of a transition in the term itself. When citizens are considered users or data providers, it is assumed that personal data comprise a raw material that the citizens take for granted, as another element of the ‘market’. This fact should draw the attention of policy-makers insofar as there are underlying value issues and political decisions involved.

According to the interviews conducted, the policy papers analysed, and the ethnographic research carried out, the current status of the smart citizens understanding in each location is as follows:

In Barcelona, according to Capdevilla et al. and Bakici et al. [49,50], “Smart Citizen” projects served as illustrative examples of how grassroots initiatives could be gradually adopted by citizens and public institutions. In 2012, the concept of the “Smart Citizen” was launched. This was the result of many technological and cognitive experiments developed over the years at the Fab Lab Barcelona at IAAC, and was inspired by the work of entrepreneurs such as Arduino and Pachube. However, at that time, it was quite adventurous to imagine a Smart City model that was different than the landscape painted by large technology corporations, which were hegemonic by selling worldwide as an IT-based, urban playground where citizens were seen as mere consumers and data providers. Since then, the www.smartcitizen.me project [51] has deployed more than 1200 sensors around the world. This process has employed working with more than twenty universities and has been used as a case study in many academic papers and books [13]. Now, cities are using the term “smart citizen” as a standard for defining citizen participation in the smart city agenda. The founders advocate for making technology valuable for people’s lives not as a consumer good, but as a tool that empowers citizens and takes their roles in their cities to a new level, and we feel this has only just begun. In 2013, the “Smart Citizen Kit” project won the World Smart Cities Awards. According to Bakici et al. particularly, the overall transformation of Barcelona into a Smart City was progressing successfully, and it was already widely recognised as a leading case of Smart City initiatives all over Europe.

Nevertheless, as we will observe later, after some changes in the City Council of Barcelona and the Regional Government of Catalonia [52], “Smart Citizens” initiatives have been evolving. On the one hand, the City Council of Barcelona has recently launched the new Barcelona Initiative for Technological Sovereignty smart strategy [53], which is absolutely a political manifesto in favour of “fighting for the digital rights and sovereignty of data”, contrasting with the previous governmental period in both ideology and scope. This is a notion that crosses with the factor of the techno-politics of data. On the other hand, projects such as “data-driven cities” [54] and “making sense” [55] have engaged much more with data literacy and citizen sensing.

Thus, as we can observe from recent research results, projects deploying the preliminary idea of “smart citizens” as decision-makers rather than data providers varies from the previous institutional period [56,57] by introducing new elements insofar as sociopolitical and ethical challenges are surfacing. As such, techno-politics of data is rather present in the policy debate in Barcelona, a debate that is not entirely linked (thus far) with devolution. Although paradoxically, devolution (macro)-political debate exists permanently among those interviewed and in the diagnosis of Barcelona as a global smart city beyond its borders.

Regarding Bilbao, the interviews with the public authorities, private companies, local social entrepreneurs, managers in academia, and some civic associations located in certain renewed areas in Bilbao, such as Zorrozaurre [58], have shown pervasive transitions towards smart citizens as decision-makers rather than data providers. The main conclusion could be the dichotomic narrative in the city by some local managers [59,60] on the one hand and by grassroots urban movements on the other hand. Despite the Guggenheim effect—highly studied by many authors [61,62,63,64,65,66]—representing the opening of the new Guggenheim Museum in 1997 and characterising this beginning with the redevelopment of the old port and waterfront into a post-industrial, “trendy”, urban landscape with distinct international references in architecture and design, the urban political divide is rather pervasive, according to some authors, as well [67,68,69]. In fact, the interviews clearly showed a divide in the understanding of who are “smart citizens”. There is an “industrial” business version of how the city should encourage just competitiveness as a main driving force of the smart strategy [70,71,72]. Even the narrative around data and its techno-politics simply reproduces a technical infrastructure of information without considering any experimental, deliberative processes [73]. However, some initiatives led by academia and social entrepreneurs are currently emerging [74] that could be seen as seeds for upcoming less technocratic approaches to smart cities by opening up the experimental policy scope towards “smart citizens” as decision-makers.

According to a recent performance assessment framework on Bristol’s smart city strategy [75], this strategy was formed in 2011 to lead the digital innovation agenda within the city with the initial focus areas of smart energy, smart mobility, and smart data. Two main landmark projects are detailed as the key performance of this city: Bristol is an “Open” [76,77] and “Replicate” EU-funded H2020 project. Actually, Bristol’s smart strategy [78,79,80,81,82], according to the assessment, has already implemented interactive, inclusive, and continuous engagement methods to practice transparency and has made the best of the feedback.

After conducting interviews in Bristol, the first institutional feature that has modified the governance strategy regarding the smart city has been the appointment of the new mayor, Mr. Marvin Rees. Despite landmark projects such as Connect Bristol (Future Cities Demonstrator), funded via a £3 million grant from the UK government’s Technology Strategy Board (TSB); Gigabit Bristol; Bristol Is Open; 3-E Houses; Bristol Data Dome; Knowle West Media Centre; and Replicate, some commentators have asked whether the smart city strategy and projects being rolled out in Bristol are sufficiently ambitious and systemic to compete with London. By contrast, others note that Bristol is expected to increase its population by over 20% by the end of the 2020s.

Considering the information provided in the policy reports and the interview results Bristol presents an increasing effort to experiment with smart citizens as decision-makers rather than data providers. As it was recently shown in the Venturefest event, the technology produced in Bristol [83] depicts a singular notion of citizens as those taking part in deliberation processes. As such, Bristol is ultimately amalgamating a large number of smart projects in a complex network of interactions with citizens in a prospect of the future that will be held on the challenge to foster decision-makers’ interplay, portraying the city as an open innovation platform [84].

Finally, Glasgow [85] has been portrayed as a city trying to reinvent itself through competition and awards, including Glasgow European Capital of Culture 1990, Glasgow City of Science, Glasgow City of Music, and, the smart-city-related Future City Glasgow, awarded by the Technology Strategy Board, now Innovate UK, since 2013. Despite long-standing social problems, the high level of commitment to transforming the city points to an inclusive, highly networked city with a commitment to partnership. The partnership infrastructure in Glasgow resonates with urban governance institutionalised settings. On top of the urban governance partnership, Glasgow flags its commitment clearly with the quality of citizens’ lives as central. As well, the city branding fuelled by the motto “People Make Glasgow” speaks for itself. However, after analysing what the Future City Glasgow demonstrator project proposed, we can assess that the ideas of transformation, of what is to be transformed, and by whom could appear vague. After conducting interviews on this issue, despite the good urban governance partnership, the direct benefits of making data public are not clear. Thus, there is an assumption that providing data/evidence will directly lead to action.

Hence, despite the rich and comprehensive smart strategy in Glasgow showing an outstanding interplay between institutions and organisations, some discussants pointed out the lack of specific deployment of strategic actions, which contrasts with the reports provided at the city-regional level by the Scottish Cities Alliance [86,87,88]. In the final report of the Scottish Cities Alliance, there is a remarkable claim of establishing a city-regional collaborative environment to develop, deploy, and scale smart city solutions in Scotland’s seven cities.

To sum up, citizens own data as the intrinsic part of their urban experience and their “right to the city” [89,90]. Why then do we not naturally consider “smart citizens” pure decision-makers rather than passive data providers? Despite the willingness to pursue more democratic than technocratic sustainable futures, there is a strong inertia resisting this alternative path. The current round of urban experimentation differs from previous incarnations, representing a specific kind of governance “fix” for a broadly neoliberal system struggling to move towards more sustainable forms of urban development [91] (p. 10). Perhaps it is worth noting Subirats’ [92] interesting reflection that, based on Oström’s influential thoughts on the “commons”, suggests breaking with the individualistic vision conceived by the capitalist tradition. Subirats [93] notes that this vision has progressively transferred the idea of rights to individual people; the new prevailing view is that only privatisation leads to growth.

In a serious attempt to show a transition towards smart city strategies in the four cases presented, a deeper analysis of the techno-politics of data will be required to interpret the role of smart citizens as decision-makers rather than data providers. This notion is likely to be influenced by new conceptual explorations and empirical analyses carried out under the broad umbrella of the “urban commons”.

4. Comparing Smart-City Regional Governance Strategies-in-Transition in Four European Cases: Glasgow, Bristol, Barcelona, and Bilbao

European cities [14,32,34] in many countries have expanded beyond their municipal borders and commuting distances have increased, further extending the reach of these economies. To better reflect this new urban reality, more and more countries have established metropolitan governments and/or merged municipalities. According to the European Commission and UNHabitat joint report [32], the keys to good urban governance are high levels of trust, efficient service delivery, and good stakeholder and citizen involvement. This improves policy effectiveness, which, in turn, inspires more trust and involvement, thus creating a virtuous cycle.

However, establishing metropolitan governments themselves could be a first step towards a forward-looking politics of smartness in cities and regions. According to Herrschell and Dierwechter [33] (pp. 20–22), the ‘fluid’, ‘complex’, and ‘fuzzy’ socio-territorial configuration of city-regions [31] requires a governance approach using innovative transitions to address two aims. The first of these is to establish powers and policy-making tools, including collaborative networks across institutional and territorial divisions between metropolitan and regional stakeholders. The second is to experiment with new ideas about democratic legitimacy and political inclusion.

In the current smart city ‘universe’, technologies generally enact algorithmic and KPI-driven governance and forms of automated management. In this direction, Harari states [10] (p. 367), “(…) Dataism says that the universe consists of data flows, and the value of any phenomenon or entity is determined by its contribution to data processing”. These facilitate and produce instrumental, functionalist, technocratic, top-down forms of governance and government, including planning, which are underpinned by an ethos of civic paternalism (what’s the best for smart citizens without considering them). They often provide ‘sticking plaster’ or ‘work around’ solutions, rather than tackling root and structural causes. By contrast, a smart city-regional governance model that would foster, co-create, and co-produce citizen engagement should be open and transparent in its formulation and operation. Furthermore, it should be used in conjunction with a suite of aligned interventions, policies, and investments that seek to tackle issues in complementary ways and need to be set within a wider long-term plan/vision for the city by the city. However, city-regions could be presented as fractured landscapes with respect to the city-regional geography itself and also with respect to stakeholders. City-regional actors are supposed to play an important role due to the vagueness of the policy concept of metropolitan regions as Fricke advocates [34] (p. 13).

After the qualitative fieldwork based on action research in the aforementioned four cases of Glasgow, Bristol, Bilbao, and Barcelona, this paper concludes that any smart city-regional governance model must answer to this question: For whom and what purpose is the smart city in our location being developed? Thus, three intertwined options are at stake when smart cities primarily are or should be about:

- (1)

- creating new markets and profit,

- (2)

- facilitating state control and regulation, and

- (3)

- improving the quality of life in citizens.

This paper reflects the governance transitions and the broader difficulties in grasping the smart cities’ systemic urban transformation [94] at the metropolitan and the city-regional scale. It is noteworthy that the scales of multilevel governance pluralise with intensifying patterns of European connectivity and accelerating economic restructuring. This trend gives rise to the notion of city-regional governance in nation-states [31]. In this paper, ‘smartness’ should be taken as an outcome of regional urban transformations in governance. This reconciles seeming contradictions between established growth agendas and a rising concern with a broader range of qualitative parameters, such as societal and territorial cohesion. These are aspects that increasingly are being included in smart city policy agendas as an outcome of the on-going transition in the researched city-regions.

Regarding the comparison of the metropolitan scale of the four cases (see Table 1), these are noteworthy: the abundance of municipalities in Bilbao and Barcelona, the slightly higher population in Barcelona and Glasgow, and the prominent economic context in Bristol.

Table 1.

Metropolitan scale. Source: Eurostat.

Table 2 provides information about the city-regional scale in each of the cities. In Bilbao, it is evident that the absolute fiscal autonomy of the city-region as a consequence of the Economic Agreement with the nation-state (Concierto Económico) and the control of revenue-raising powers has allowed the province of Bizkaia to design a tax system that promotes investment and responds to economic changes [95]. The most paradigmatic landmark is the Guggenheim Museum, although the metro system and the water sanitation project should also be mentioned. Since the Basque autonomy is equipped with the power to decide on local and regional policies, Bilbao combines determined public sector leadership and existing entrepreneurial culture.

Table 2.

City-Regional scale.

In Barcelona, Catalonia’s elected parliament after regional elections in September 2015 announced the beginning of the secession process within Spain. It could be argued that this announcement took place after a long period of no communication with the Spanish Central Government. It is evident that this situation provokes uncertainty, both at the city-regional level in Catalonia and in Spain, where the Spanish government has not been formed yet, due to profound changes in the new electoral structure.

In Bristol, the West of England’s city-region is already the UK’s most economically productive area. In September 2015, the city-region proposed a devolution deal worth £2 billion pounds with a commitment to form a Combined Authority and a £1 billion pounds investment. This could triple the level of spending on major projects—such as transport, flood defence, and housing—over the next 10 years.

In Glasgow, finally, the smart city debate is not separated from the city devolution discussion either. The devolution debate is focused on the disagreement with the rest of the favourable vote for Brexit in the rest of the UK by demanding a direct interlocution between the Scottish government and Brussels in order to remain in the EU as a direct way to achieve the devolution of powers on welfare and tax policy.

The conclusion is that in the Spanish cities, infrastructure regimes are organised at an urban or city-regional scale, at least in Bilbao. Barcelona will seemingly allow itself to have financial resources by altering the territorial model and confronting the nation-state. In contrast, in the UK cities, after UK Innovate demonstrator projects in the two cities, Glasgow and Bristol will face, sooner or later, the city-regional devolution debate. This is after years of multilevel centralised government in the UK, regarding policy direction, funding, and infrastructure investment [96,97,98,99].

The hypothesis of this paper suggests that, on the one hand, the techno-politics of data’s social awareness and, on the other hand, devolution policy in the four cases mentioned will mutually reinforce one another. We could observe this potential correlation in the four cases in rather different ways, through very difficult so far, to quantify or to assess in numeric terms how much this influences the formulation of smart city-regional policies.

Hence, in order to operationalise this hypothesis and provide some preliminary research results for further future exploration, a comparative analysis in Table 3 describes nine dimensions that blend and intertwine, whether or not and how the cases are considering the techno-politics of data and the influence of devolution in their policy implementations and potentialities. After policy papers of each case were analysed and interviews were carried out, the analysis of the four smart city-regional governance cases-in-transition will describe:

- (1)

- The Smart City-Regional Governance analyses

- (2)

- Multi-stakeholder interdependencies’ analyses

- (3)

- Current smart city-regional transitions

- (4)

- Current smart metropolitan transitions

- (5)

- Degrees of devolution, per se

- (6)

- Degrees of civic engagement

- (7)

- Smart policy formulations

- (8)

- Collective intelligence [100,101]

- (9)

- Techno-politics of data approaches

Table 3.

Analysing Bilbao, Barcelona, Bristol, and Glasgow Smart City-Regional Governance Cases in Transition: Towards Techno-Politics of Data through Smart Devolution?

As a systemic outcome, the paper will conclude by deducing one strategic implicit typology per case.

Bilbao depicts an outstanding city to be rebranded as a new, modern icon of the smart urban renaissance. Its strategy has been led by public and private partnerships without any explicit strategy, but with implicit corporate procedures. However, we should point out that civic groups, social entrepreneurs, and academics have been absent in this strategy so far. Therefore, Bilbao requires well-funded, interconnected, niche experiments in a limited range of urban contexts by mobilising a multi-stakeholder approach [45,100].

By focusing on the table, the smart city-regional governance context shows a strong metropolitan institutional model, although it is fragmented in a highly dense fabric of actors regarding the three-scale institutional structure (regional, provincial, and local). Metropolitan Bilbao’s historic renewal has been a model in noticing the consistent public-private-partnership employed during the last twenty years. Nevertheless, civic engagement has been largely absent, accompanied by a weak urban interdisciplinary collaboration between universities and civic society. Ultimately, the landmark niche project titled “Zorrozaurre”, seems to concentrate the highest expectations of the post-Guggenheim era on the city-region. Regarding multi-stakeholder interdependencies, Bilbao has, thus far, been dominated by a top-down model labelled as Industry 4.0. Thus, the Zorrozaurre pilot project could be presented as a linkage with the citizenship in a more experimental and wider, platform-based project, which has recently been funded by the EU under the acronymum AS FABRIK. Paradoxically, the high degree of devolution contrasts with the elite-driven, low degree of citizen engagement. However, around academic and social entrepreneurial urban spaces, new collective intelligence initiatives are flourishing with a strong awareness of the techno-politics of data and alternative urban models for economic development and social cohesiveness. As such, we could deduce that Bilbao is having a transitioning from a corporate urban governance model. Thus, I could call this case “Corporate-In-Transition”.

For a long time, Barcelona has been investing and promoting itself as the first Smart City in Spain, the fourth in Europe, and the tenth in the world [56,57]. Presently, due to the appointment of a new city mayor—Ada Colau, who represents a radical new citizen platform called “Barcelona in Common”—an initial smart city strategy has shifted towards an “open source” strategy. Nonetheless, after interviewing key stakeholders in the city, we can conclude that Barcelona is currently ”digesting” a transition driven by a new city strategy called the Barcelona Initiative for Technological Sovereignty (BITS) influenced by renowned scholars such as Harvey, Morozov, and Subirats, among others. This transition has moved from the hegemonic position of the private sector that aimed to produce universal solutions that could be applied globally with minimal adaptation in order to maximise profit, to local authorities’ interests now that co-produced and place-specific smart city solutions are required.

By focusing on the table’s results, I conclude that there is actually a transition occurring after the new mayor, Ms. Ada Colau, was appointed as the grassroots leader from the civilian platform Barcelona in Common. In fact, the new smart city branding is “Technological Sovereignty”, or an explicit governance model to encourage public debates on the implications, rights, and techno-politics of all that the digital revolution affects. Although a clear evolution is taking place in Barcelona from a top-down to a bottom-up approach, there are still inherent conflicts between the regional government (Generalitat) and the local authority led by mayor Mayor Ada Colau. In addition, both devolution claims are increasingly progressing, and the civic engagement initiatives are being popularized by diverse local actors. In this sense, both the smart city policy formulation and the collective intelligence initiatives reinforce each other in a new exploitation of projects and strategies embracing “data-driven cities” [54,102,103,104] by particularly considering smart citizens as those central to decision-making processes. Nonetheless, the engagement of the private sector (which is highly substantial regarding the international IT corporate sector located in the metropolitan area) needs to be seriously considered in the plans of the local authority in combination with the regional government. Thus, I could call this case “Anti-Corporate-Uncertain”.

In April 2013, Bristol received £3 million from UK Innovate. Bristol has followed “open innovation” principles led by its flagship operational organisation, Bristol is Open, driven by the triple-helix. Bristol has been described by some discussants as the “rebel” of the UK’s smart city agenda. The new mayor, Mr Marvin Rees, has altered the smart agenda towards more social cohesiveness and inequality policy principles. However, considering its diverse funding model, there may be a need for the city council to engage the smart city agenda with the city-regional´s ongoing process of devolution.

Judging from Table 3, Bristol presents a prominent context in which to experiment with new models of urban governance. Considering the high degree of citizen engagement, Bristol is undoubtedly a city leading in smart citizens’ roles as decision-makers. In contrast, the current devolution context may evolve due to Bristol having voted to move forward with the West of England devolution deal. In June 2016, three councils—Bristol, South Gloucestershire and Bath and Northeast Somerset—agreed to form a new authority headed by a “metro mayor”. Thus, the new West of England Mayoral Combined Authority will sit above the existing councils to decide how to spend an increased budget and what to do with its new powers. Thus, I could call this case “Open-Innovation-Alternative”.

By contrast, in January 2013, Glasgow won £24 million in funding from the UK Innovate. Why was Glasgow so successful? Glasgow was distinct in its ambition and the framing of its intervention around the city’s social and health priorities. The question here is whether or not its broad infrastructural and institutional support and its urban governance model have integrated into a broader, city-regional scale, as suggested by either the Scottish Cities Alliance or by Core Cities, two city-networks with entirely different city-regional political directions.

By analysing Table 3, Glasgow has been investing in a smart partnership structure. However, further strategic interventions will be required to consolidate technological investment towards higher degrees of communitarian participation. We could already say that there is a mismatch between the data discourse and the willingness of the Glaswegian participatory atmosphere. Thus, I could expect that in the coming months, a techno-political debate will begin among stakeholders regarding self-tracking systems and the “big data-ism” concerns. Thus, I could call this case “Urban-Governance-Transformative”.

5. Conclusions: Towards Techno-Politics of Data through Smart Devolution?

The availability of data is, and will be, part of the new conditions in cities [105]. Yet, unpacking the ownership of data and its governance structure and dynamics within their citizenries will be as important as the collection, storage, and usage of data in cities and regions. Why are smarter use of technology and data vital to the success of city devolution, and vice versa? On the one hand, city devolution could deal with data deficit. However, on the other hand, it will be worth using existing public sector datasets to effectively deliver devolved powers to local and regional authorities.

In this paper, four European city-regional cases show diverse path dependencies when it comes to their strategic approaches to smart city policy formulations regarding two intertwined aspects:

- The consideration and social awareness of the techno-politics of data in each case.

- The influence of current devolution schemes on smart policy formulation and implementation.

After presenting the comparative analysis and results of the qualitative research of the four cases, and given the interest of devolution as it is related to data, software applications for user engagement, bottom-up decision-making processes, and user-driven or citizen-centric open innovation platforms, this paper will conclude that in all of the analysed cases, pervasive devolution will make the difference insofar as:

- It could determine the financial and institutional infrastructures to implement smart city initiatives in diverse fields, not only energy, mobility, and ICT, but also welfare and social fields (i.e., education, healthcare, tourism, culture, and social policy).

- As a consequence, data debate will sooner or later combine with devolution debate insofar as collectively deciding will mean facing changes in city government, new political leadership profiles, innovative financial schemes, establishing a level of autonomy in relation to the central government, and a degree of devolution and powers to be devolved, which would modify the interplay of stakeholders and their interdependencies [102,106].

In summary, this paper compares four cases by drawing attention to the weakened capacities of urban governments to control their infrastructural destinies and the constraints on the public and private sectors’ abilities to innovate. Based on the results presented, this paper has, by comparing four smart city-regional governance strategies, concluded the following: at present, Bilbao is driven by a corporate-in-transition strategy, Barcelona by an anti-corporate-uncertain strategy, Bristol by an open-innovation-alternative strategy, and Glasgow by an urban-governance-transformative strategy.

The conclusion of this paper lies in the notion that smart strategies in city-regions are being modified as a result of a transition in the understanding and application of the (techno) politics of data and of the increasing significance for their benefitting from some devolution scheme [35,36,37,38]. As long as a city or a region facilitates the ownership and the self-responsibility of investment in the smart infrastructures and resources, the data-issue awareness will be shared among different stakeholders, even by encouraging them to collaborate, having different visions and aims.

From the broad perspective, devolution is a phenomenon that will be affecting cities and regions in their governance structures and forms. According to Khanna [35] (p. 64), “the growing power and connectivity of provinces and cities are driving devolution in the 21st century as significantly as decolonisation did in the 20th century.” In fact, cities no longer need their national capitals neither to filter paradiplomatic relations with the world nor prioritise their smart initiatives and projects. Every location can compete/cooperate as an investment destination, and central governments will no longer control and decide how money will be spent on behalf of their citizens.

To conclude, as we are recently observing and noticing in the UK, [107] a notion of ‘smart devolution’ is required to better implement a test of devolution, understood as sovereignty, legitimacy, authority, and also responsibility directly derived from the right to the city rather than legal independence, but retaining autonomy to pursue each city or region’s own interests.

As such, the future will show us an increasing number of cities rolling out their metropolitan strategies [106] in coordination with a broader region to achieve further democratic developments in which the will of citizens is likely be at the centre of the decision-making process. Thus, three questions, related to current transitions in some city-regions like those four presented, could be suggested at the end of this paper to open the floor for further discussion on the techno-politics of data and smart devolution in city-regions: (1) What prospects are there for alternative funding and business/social models for smart city-regions? (2) What are the practical/political interventions needed within a multi-stakeholder penta-helix scheme (business, government, communities, academia, and entrepreneurs)? (3) Is another smart city-region paradigm possible—one that is connected with some experimental advancements related to the urban ‘commons’ and smart devolution, a third way between the state and the market, and beyond the so-called public–private-partnership (PPP)?

Acknowledgments

The fieldwork research was supported by Bizkaia Talent and Bilbao Metrópoli-30 funded by the EU-Marie Curie Actions-MSCA-COFUND-2015-Regional Programmes under Grant AYD-000-268.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Forbes. Cities Cannot be Reduced to Just Big Data and IoT: Smart City Lessons from Yinchuan, China. Available online: http://www.forbes.com/sites/federicoguerrini/2016/09/19/engaging-citizens-or-just-managing-them-smart-city-lessons-from-china/#6a5a34392dda (accessed on 10 November 2016).

- Kitchin, R. Smart Cities and the Politics of Urban Data. In Smart Urbanism: Utopian Vision or False Dawn? Marvin, S., Luque-Ayala, A., McFarlane, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian. The Rise of Data and the Death of Politics. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jul/20/rise-of-data-death-of-politics-evgeny-morozov-algorithmic-regulation (accessed on 10 November 2016).

- Calzada. From the Smart City to the Experimental City: Smart Citizens as Decision Makers Rather Than Data Providers. In Co-Designing the Economies of Becoming in the Great Transition: Radical Approaches in Dialogue with Contemplative Social Sciences; Walsh, Z.D., Giorgino, V.M.B., Eds.; Process Century Press: Claremont, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Lure of Technocracy; Polity Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kurban, C.; Peña-López, I.; Haberer, M. What Is Technopolitics? A Conceptual Scheme for Understanding Politics in the Digital Age. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Internet, Law & Politics, Barcelona, Spain, 7–8 July 2016; pp. 499–519.

- Grasseger, H.; Krogerus, M. The Data That Turned the World Upside Down. Available online: http://motherboard.vice.com/read/big-data-cambridge-analytica-brexit-trump (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Campbell, T. Beyond Smart Cities: How Cities Network, Learn and Innovate; Earthscan: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, W. How Statistics Lost Their Power—And Why We Should Fear What Comes Next. In the Guardian, 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/jan/19/crisis-of-statistics-big-data-democracy (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- Harari, Y.N. Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow; Harvill-Secker: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, B. The Bleeding Edge: Why Technology Turns Toxic in an Unequal World; New Internationalist: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, S.; Luque-Ayala, A.; McFarlane, C. Smart Urbanism: Utopian Vision or False Dawn? Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Noveck, B.S. Smart Citizens, Smarter State: The Technologies of Expertise and the Future of Governing; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Mapping Smart Cities in the EU; European Union: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bollier, D.; Helfrich, S. The Wealth of the Commons. A World beyond Market and State; Levellers Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bollier, D.; Helfrich, S. Patterns of Commoning, the Commons Strategies Group. Available online: http://bollier.org/blog/spanish-translation-%E2%80%9Cthink-commoner%E2%80%9D-now-published (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- Borch, C.; Kornberger, M. Urban Commons: Rethinking the City; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada, I.; Cobo, C. Unplugging: Deconstructing the Smart City. J. Urban Technol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Times. Yuval Noah Harari on Big Data, Google and the End of Free Will. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/50bb4830–6a4c-11e6-ae5b-a7cc5dd5a28c (accessed on 10 November 2016).

- Rossi, U. The Variegated Economics and the Potential Politics of the Smart City. Territ. Politics Gov. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirall, E.; Lee, M.; Majchrzak, A. Open innovation requires integraded competition-community ecosystems: Lessons learned from civic open innovation. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttiroiko, A. City-as-a-Platform: Towards Citizen-Centre Platform Governance. In Proceedings of the RSA Winter Conference 2016 on New Pressures on Cities and Regions, London, UK, 24–25 November 2016.

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing the public participation process for planning projects. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R. Civic Crowdfunding: Participatory Communities, Entrepreneurs and the Political Economy of Place. Master’s Thesis, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. Three Provocations for Civic Crowdfunding. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Almirall, E.; Chesbrough, H. The City as a Lab: Open Innovation Meets the Collaborative Economy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 59, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Solés, M.; Íñiguez-Rueda, L.; Subirats, J. How to govern the complexity? Invitation to an hybrid and relational urban governance. Athenea Digit. 2011, 11, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, T.; Baeck, P. Rethinking Smart Cities from the Ground up; NESTA: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer, E.; Mahmoudi, D. Citizen Participation, Open Innovation, and Crowdsourcing: Challenges and Opportunities for Planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2012, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeth, T. An investigation of IBM’s Smarter Cities Challenge: What do participating cities want? Cities 2016, 63, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Benchmarking Future City-Regions beyond Nation-States. RSRS Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2015, 2, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union and UNHabitat. The State of European Cities 2016: Cities Leading the Way to a Better Future; European Union and UNHabitat: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Herrschel, T.; Dierwechter, Y. Smart City-Regional Governance: A ‘dual transition’. Regions 2016, 300, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke, C. Metropolitan Regions as a Changing Policy Concept in a Comparative Perspective. Raumforsch Raumordn. 2016, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, P. Connectography: Mapping the Global Network Revolution; Orion Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Institution of Civil Engineers. State of the Nation 2016: Devolution; Institution of Civil Engineers: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, J.; Casebourne, J. Making Devolution Deals Work; Institute for Government: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, C.; Copeland, E. Smart Devolution: Why Smarter Use of Technology and Data are Vital to the Success of City Devolution; Policy Exchange: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto, C.R.; Ekbia, H.R.; Mattioli, M. Big Data is Not a Monolith; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, G.; Nafus, D. Self-Tracking; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NewStatesman. I Want My Country Back by Laurie Penny. Available online: http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2016/06/i-want-my-country-back (accessed on 1 August 2016).

- McCelland, J. Why Bristol’s a City of the Future. In Racounteur. Available online: http://www.raconteur.net/technology/why-bristols-a-city-of-the-future (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- Talentia Network. Zorrozaurre: Smart and Sustainable System for the future Zorrozaurre Island. Available online: www.bizkaiatalent.org/en/talentiasareafinala/ (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Bilbao Metropoli 30. Bilbao Metropolitano 2035: Una Mirada Al Futuro. Reflexión Estratégica. 2015. Available online: www.bm30.es (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Calzada, I. (Un) Plugging Smart Cities with Urban Transformations: Towards Multistakeholder City-Regional Complex Urbanity? URBS Rev. Estudios Urbanos Cienc. Soc. J. 2016, 6, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- West, J.; Bogers, M. Open Innovation: Current status and research opportunities. Innov. Organ. Manag. 2016, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oström, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Oström, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, I.; Zarlenga, M.I. Smart City or Smart Citizens? The Barcelona case. J. Strategy Manag. 2015, 8, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakici, T.; Almirall, E.; Wareham, J. A Smart City Initiative: The Case of Barcelona. J. Knowl. Econ. 2013, 4, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Citizens. Available online: www.smartcitizen.me (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Generalitat de Catalunya. SmartCATALONIA: Catalonia’s Smart Strategy; Generalitat de Catalunya: Catalonia, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BITS. Barcelona Initiative for Technological Sovereignty. Available online: https://bits.city/ (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- PwC. Data-Driven Cities: From Conceptual to Applied Solutions; PwC: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Digital Social Innovation. Making Sense EU-Funded Project. Available online: https://digitalsocial.eu/case-study/14/making-sense (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Barcelona Smart City: Vision, approach and projects of the Barcelona City to Smart Cities—Executive Version; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelona Institute of Technology. Available online: http://www.slideshare.net/MariaGalindo4/bit-barcelona-institute-of-technology (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Urban Innovative Actions (UIA). Call 1: Selected Cities Taking-off; Urban Innovative Actions: Lille, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aldekoa, A. The Vision of Bilbao. Available online: http://www.slideshare.net/SPRICOMUNICA/aldekoa-the-vision-of-bilbao-jakiunde (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Aldekoa, A. El Caso de Bilbao. La Reinvención de una Ciudad Basada en su Tradición Industrial; Jakiunde, Academia de las Ciencias del País Vasco: País Vasco, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alayo, J. Re-Positioning the Post-Industrial City in the Global Economy: Case Study Summary. In Proceedings of the 2013 Remaking Cities Congress, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 15–18 October 2013.

- Alayo, J.; Henry, G.; Plaza, B. Bilbao Case Study. In Remaking Post-Industrial Cities: Lessons from North American and Europe; Carter, D.K., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Cearra, A. Hacia la Smart City; El Mundo: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Cearra, A. Smart Cities un Urbanismo Más Sostenible, Amable e Inteligente; El Correo newspaper: Bilbao, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG. Magnet Cities: Decline, Fightback, Victory; KPMG: Watford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Plöger, J. Bilbao City Report; CASEreport 43; Centre for Analysis of Social Esclusion: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, S. Scalar Narratives in Bilbao: A Cultural Politics of Scales Approach to the Study of Urban Policy. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2006, 30, 836–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.; Martinez, E. Restructuring Cities: Miracles and Mirages in Urban Revitalization in Bilbao. In The Globalized City; Rodriguez, M.F., Swyngedouw, E.A., Eds.; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, A.; Martínez, E.; Guenaga, G. Uneven Redevelopment—New Urban Policies and Socio-Spatial Fragmentation in Metropolitan Bilbao. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2001, 8, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao Lan Ekintza. Diagnóstico de Competitividad Comarcal; Bilbao Lan Ekintza: Bizkaia, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao Urban Solutions. Solutions for the Future: Arteche, BBVA, CAF, Factor Co2, Gamesa, Gerdau, Iberdrola, Ibermática, Idom, Ikusi, Inbisa, Ingeteam, Lks, Mesa, Ormazabal, Orona, Saitec, Sener, Tecnalia and Vicinaymarine; Bilbao Urban Solutions: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao City Hall and Bilbao Ekintza. Bilbao Urban Solutions; Bilbao City Hall and Bilbao Ekintza: Bizkaia, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CIMUBISA. Ciudades Inteligentes: Los Datos Como Base Para la Toma de Decisiones; CIMUBISA: Bizkaia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WeLive. EU H2020 Funded Project, Addressing ICT-Enabled Open Government—INSO1 Topic, about a New Concept of Public Administration Based on Citizen Co-Created Mobile Urban Services. Available online: http://welive.eu/ (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Henley, R. Evaluating the Performance of Bristol’s Smart City Programme; Presentation; Bristol City Council: Bristol, UK, 2017.

- Bristol Is Open. FAQ; Bristol Is Open: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol Is Open. Creating The World’s First Open Programmable City; Bristol Is Open: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol Smart City Delegation. Information Pack; Bristol Smart City Delegation: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol City Council. Smart City Bristol—Final Report; Bristol City Council: Bristol, UK, 2011.

- Bristol City Council. Smart City Benchmark; Bristol City Council: Bristol, UK, 2011.

- Bristol City Council. Connect Bristol Feasibility Study; Bristol City Council: Bristol, UK, 2012.

- Bristol City Council. The Population of Bristol; Bristol City Council: Bristol, UK, 2014.

- VentureFest. 2017. Available online: http://venturefestbristolandbath.com/ (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Caprotti, F.; Cowley, R.; Flynn, A.; Joss, S.; Yu, L. Smart-Eco Cities in the UK: Trends and City Profiles 2016; University of Exeter (SMART-ECO Project): Exeter, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cowley, R.; Joss, S.; Dayot, Y. The Smart City and Its Publics: Insights from Across Six UK Cities; Working Document; Smart Eco Cities: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Cities Alliance. City Investment Plans: Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Inverness, Perth and Stirling; Scottish Cities Alliance: Glasgow, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Cities Alliance. Smart Cities Readiness: Smart Cities Maturity Model and Self-Assessment Tool. Guidance Note for competion of Self-Assessment Tool; Scottish Cities Alliance: Glasgow, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Cities Alliance. Smart Cities Scotland Blueprint; Scottish Cities Alliance: Glasgow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Conversation between Evgeny Morozov and David Harvey. Available online: http://davidharvey.org/2016/11/video-conversation-between-david-harvey-evgeny-morozov-on-post-neoliberalism-trump-infrastructure-sharing-economy-smart-city/ (accessed on 10 November 2016).

- Shaw, J.; Graham, M. An Informationl Right to the City? Code, Content, Control, and the Urbanization of Information. Antipod. Radic. J. Geogr. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Karvonen, A.; Raven, R. The Experimental City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. (In Print) [Google Scholar]

- Open Democracy. The Commons: Beyond the Market vs. State Dilemma. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/joan-subirats/commons-beyond-market-vs-state-dilemma (accessed on 10 November 2016).

- Subirats, J.; García Bernardos, A. Innovación Social y Políticas Urbanas en España: Experiencias Significativas en las Grandes Ciudades; Barcelona: Icaria, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne Clarke. Smart Cities in Europe: Enabling Innovation; White Paper; Osborne Clarke: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Uriarte, P.L. Nuestro Concierto: Claves Para Entenderlo; Pedro Luis Uriarte: Bilbao, Spain, 2016; Available online: http://www.elconciertoeconomico.com/descargate-la-obra/ (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Arup. Smart Cities: Transforming the 21st City Via the Creative Use of Technology; Arup: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arup. Future Cities: UK Capabilities for Urban Innovation; Arup: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arup. Delivering The Smart City: Governing Cities in the Digital Age; Arup: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- BIS. Smart Cities. Report, October 2013; Department for Business Innovation and Skills: London, UK, 2013.

- Karvonen, A.; van Heur, B. Urban Laboratories: Experiments in Reworking Cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NESTA. Governing with Collective Intelligence; NESTA: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ersoy, A. Smart cities as a mechanism towards a broader understanding of infrastructure interdependencies. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2017, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NESTA. Wise Council: Insights from the Cutting Edge of Data-Driven Local Government; NESTA: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Uraia Nicosia Guidelines. The Impact of Smart Technologies in the Municipal Budget: Increased Revenue and Reduced Expenses for Better Services; UNHabitat: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nasa. OpenCitySmart—The Open platform for Smart Cities. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWuMfMMPfPw (accessed on 31 January 2016).

- Katz, B.; Bradley, J. The Metropolitan Revolution: How Cities and Metros Are Fixing Our Broken Politics and Fragile Economy; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Travers, T. The Power to the Regions: Why More Devolution Makes Sense. In the Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/public-leaders-network/2017/feb/08/power-regions-more-devolution-cities-brexit?CMP=ema-1704&CMP= (accessed on 9 February 2017).

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).