1. Introduction

Environmental challenges over the past century, including resource depletion, population growth, hunger, and rising conflicts, have prompted societies to reconsider global sustainability. International agreements have highlighted the importance of environmental protection and cooperation in addressing development issues. The Brundtland Report defined sustainable development and recommended that nations reassess policies to integrate environmental, economic, and social dimensions [

1]. Sustainable development thus aims to protect the planet while promoting equality and prosperity through the combined effect of these dimensions rather than any single factor alone [

2]. Education not only holds a place within the goals of sustainable development but also supports the philosophy of sustainable development. Sustainable development and education are interconnected concepts [

3,

4]. In the Brundtland report, education for sustainable development is defined as “the process of learning to make decisions that consider the long-term future of the economy, ecology, and social equity” [

5]. Researchers stated that education for sustainable development would encourage critical thinking, the ability to think in new ways and engage with different worldviews [

6,

7,

8]. Corney and Reid stated that the success of education for sustainable development depends on teachers’ knowledge and attitudes on the subject [

9]. Another key concept related to education here is “sustainable education”. Although the goal of education in many countries is still to secure employment, there is an increasing call for education to focus on global citizenship, social justice, and sustainability [

10]. Nikel and Lowe presented the seven dimensions of education by synthesizing many studies on the sustainable development goal of quality education [

11]. According to this, quality education should be effective, efficient, equitable, responsive, relevant, thoughtful, and sustainable.

Teachers are active facilitators with complex roles that combine the implementation and maintenance of sustainable education [

12]. To establish sustainable education, it is recommended to promote intrinsic motivation among teachers and students, make instructional improvements, encourage collective or team-based activities, and ensure teacher–student cohesion. Work engagement is a highly valuable concept in terms of teacher motivation. The literature emphasizes a positive relationship between teacher motivation and work engagement [

13]. The close relationship between teacher and student motivation, highlighted as crucial in the establishment of sustainable education and work engagement, suggests that teachers’ perceptions of the presence of sustainable education are also related to their level of work engagement. Furthermore, instructional improvements, considered crucial for advancing toward sustainable education, concern not only policymakers but also teachers. Teacher work engagement is also highly important for the implementation of instructional improvements. Studies in the literature highlight a positive relationship between instructional quality and work engagement [

14,

15,

16]. This further supports the idea that teachers’ views on the presence of sustainable education are related to their work engagement. It can be said that this study, which aims to examine the relationship between the teachers’ views on sustainable education and teacher work engagement, will be the first in literature and will address an important gap.

Educational environments play a significant role among the factors that directly affect teachers’ work satisfaction and performance. It is believed that an equitable, inclusive, democratic, and quality educational environment, that is, the presence of sustainable education, is closely related to teachers’ work engagement. Therefore, the aim of this study is to model and analyses the dynamic relationships between science teachers’ perceptions of sustainable education and their levels of work engagement, adopting a systems-oriented approach with machine learning. In this study, the education system is conceptualized as a complex adaptive socio-technical system composed of interrelated human and structural subsystems. Within this theoretical framework, teachers’ demographic characteristics (e.g., academic qualifications and workload) are considered structural system variables that influence both their perceptions of sustainable education and their levels of work engagement. The constructs of sustainable education and teacher engagement function as interdependent subsystems, interconnected by continuous feedback mechanisms.

The present study hypothesizes that positive perceptions of sustainable education can lead to heightened teacher engagement, characterized by enhanced motivation, a sense of professional purpose, and alignment with sustainability-oriented practices. Conversely, heightened engagement has been demonstrated to reinforce teachers’ commitment to the implementation of sustainable educational practices, thereby engendering a reciprocal feedback loop that contributes to system resilience and adaptability. The employment of machine learning algorithms is central to the objective of this study, namely, to model non-linear, multidimensional relationships, to identify hidden interaction patterns, and to reveal the manner in which individual and contextual factors co-evolve within the educational system to maintain or disrupt sustainability.

To clarify the systems-oriented nature of the present study, a conceptual systems framework is adopted to operationalize key system components and their interrelations. Within this framework, science teachers are treated as primary agents of the sustainable educational system, while demographic characteristics such as academic qualifications and weekly teaching hours are defined as structural system parameters. Teachers’ perceptions of sustainable education and their levels of work engagement are conceptualized as dynamic system states that are mutually influential rather than independent outcomes.

In this study, feedback mechanisms are operationalized through the reciprocal relationship between sustainable education perceptions and teacher engagement. Specifically, sustainability-oriented perceptions are assumed to enhance engagement by strengthening professional meaning, motivation, and alignment with institutional goals. In turn, elevated engagement is expected to reinforce the enactment and internalization of sustainable educational practices, forming a reinforcing feedback loop that contributes to system adaptability and resilience. Although the study does not employ a formal dynamic simulation or agent-based model, this reciprocal structure provides a system-level representation of feedback processes consistent with complex adaptive socio-technical systems.

Accordingly, machine learning algorithms are employed as system-sensitive analytical tools to explore non-linear relationships, interaction effects, and emergent patterns among structural variables and dynamic system states. By identifying latent dependencies that are not readily observable through linear modeling, the study adopts a systems-informed methodological approach that aligns with the analytical aims of systems research in education.

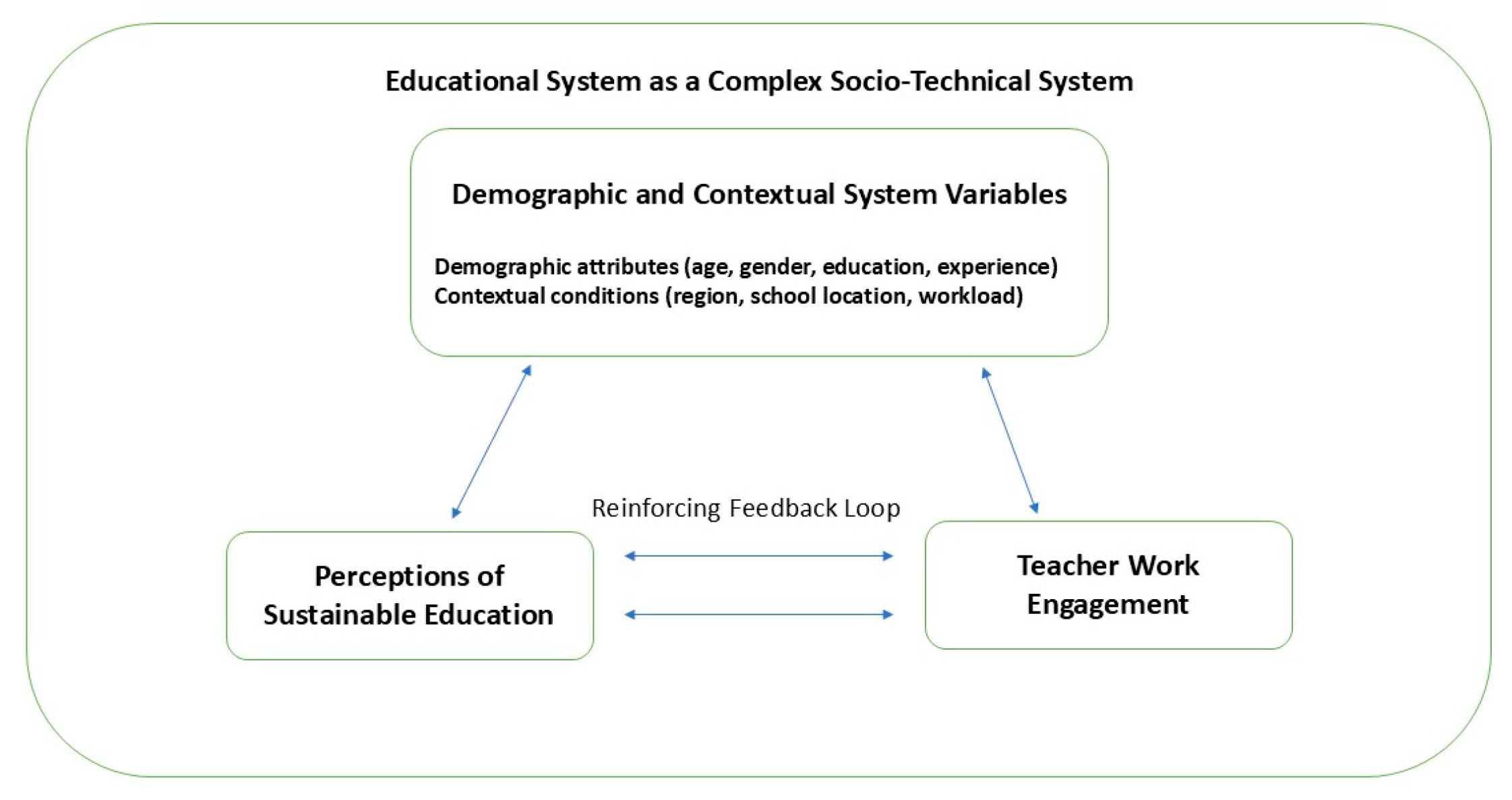

This systems-oriented conceptualization is visually summarized in

Figure 1. The figure illustrates the educational system as a complex socio-technical system, highlighting the roles of structural system variables, dynamic system states, and the reinforcing feedback loop between sustainable education perceptions and teacher work engagement that guides the analytical design of the study.

Figure 1 presents the conceptual systems framework underpinning the study. Teachers are positioned as primary agents within the educational system. Demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, educational level, teaching experience, weekly teaching hours, and school context) are conceptualized as structural system variables. Teachers’ perceptions of sustainable education and their levels of work engagement are modeled as dynamic system states that interact through a reinforcing feedback loop. The present study seeks to address the following sub-problems:

How do teachers’ demographic characteristics function as structural variables that influence their engagement and perceptions of sustainable education?

How do demographic factors and engagement levels interact to shape systemic perceptions of sustainable education?

How do perceptions of sustainable education and demographics collectively influence levels of work engagement as an adaptive system component?

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Sustainable Education

Sustainable education can be summarized as ensuring the continuity of inclusive, equitable, democratic, and high-quality education for both current and future generations [

12,

17]. Van den Branden states that sustainable education supports the learning and success of all students and utilizes their abilities, potentials, and motivations as renewable resources. Sustainable education requires an environment where all students, regardless of their socioeconomic, cultural, or gender differences, have equal rights and opportunities [

18]. In such an environment, individuals with diverse needs and abilities are given the chance to learn together where both teachers and students are involved in the decision-making processes, and different ideas are valued and respected [

19]. Moreover, contemporary and effective teaching methods are implemented to raise individuals equipped to meet the needs of the era. Teachers’ beliefs in the presence of sustainable education as the practitioners of education indicate whether they are supporters or obstacles to its realization [

20]. An environment in which quality education is provided in an inclusive, equitable, and democratic manner is closely associated with teachers’ work satisfaction and their engagement with their work.

1.1.2. Engagement with the Work

One of the concepts believed to be related to the presence of sustainable education is teacher engagement with their work. Engagement is conceptualized as a persistent and widespread emotional-cognitive state that is not focused on any specific object, event, individual, or behavior [

21]. Viewed through the lens of self-determination theory, work engagement is an indicator of intrinsic motivation and results in positive outcomes for both teachers and students [

22,

23]. Teachers with high levels of engagement have high intrinsic motivation, remain energetic and effective in the educational process, and are capable of handling complex situations [

23,

24,

25]. They are also better equipped to overcome work-related stress and burnout [

26]. Additionally, teacher engagement influences both student learning outcomes and teacher effectiveness [

27]. A high level of teacher engagement increases the likelihood of student success [

28,

29] and enhances teachers’ active participation in the workplace and contribution to the school life [

30,

31]. The literature includes studies that explore the relationship between teacher engagement and various other variables. These studies examine the relationship between teacher work engagement and teaching quality [

14,

15], work satisfaction and burnout [

32], professional development [

33], collective teacher efficacy [

34], collective teacher culture [

35] and student success [

36].

1.1.3. Machine Learning Approach in Education

The rapid advancement of technology has manifested itself in many fields, including science and statistical methods. In the traditional approach, the inadequacy or accumulation of data obtained through experiments, theories, or computations has shaped a new paradigm. According to Himanen et al., data-driven science is the process of collecting existing data within data infrastructures and discovering new materials through machine learning approaches [

37]. Big data and machine learning approaches have gained significant attention in fields such as medicine, engineering, agriculture, commerce, and others. Machine learning approaches offer various methods such as clustering, classification, and prediction based on large datasets. Recently, these alternative methods have also gained popularity among social scientists [

38,

39,

40]. The resources available in educational sciences (such as students, teachers, schools, and objectives) indicate that big data and machine learning approaches will become even more popular in the future. Factors affecting student success, teacher competencies, performance, motivation, the requirements for achieving goals, the ability to realistically predict objectives, resources allocated to education, education expenditures, educational planning, creating alerts for stakeholders, recommendation systems, and social network analysis are some of the topics that can be examined using machine learning approaches [

41,

42,

43,

44]. Recent studies on machine learning approaches in education have predominantly focused on student success [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52] and student behaviors [

53,

54]. However, machine learning in education is not limited to students. There are still few studies in the literature that address the use of machine learning approaches in analyzing data related to teachers and the education system. This study is expected to contribute to filling that gap.

1.1.4. Why This Research?

Education can be conceptualized as a complex socio-technical system, integrating human, institutional and technological components to achieve sustainable development. Within this system, teachers represent a critical human element whose engagement directly influences the adaptability, quality, and resilience of the overall structure. The efficacy of sustainable education is contingent not only on the provision of equitable access and the design of curriculum, but also on the capacity of teachers to maintain motivation, receive support, and demonstrate commitment to their professional roles. It is widely accepted that high levels of teacher engagement can be considered an indicator of the internal stability and sustainability of the education system. The present study aims to provide empirical evidence for this systemic relationship and to identify potential barriers that may hinder the realization of sustainability in education.

In contradistinction to conventional research, which relies on linear statistical models, this study employs advanced machine learning algorithms to analyses interdependent and non-linear relationships between variables. Machine learning provides a system-level analytical approach that allows for the identification of hidden patterns, feedback loops, and adaptive interactions within educational data. The present study employs a rigorous methodological approach, demonstrating the transferability of machine learning from behavioral and data sciences into educational system analysis. It is evident that the full potential of machine learning in this context has yet to be realized. It is evident that predictive algorithms, when implemented on moderately sized datasets, can yield valuable insights into complex social systems, such as education.

The overarching objective of this research endeavor is to conceptualize the dynamic interrelationships among teachers’ demographic characteristics, their perceptions of sustainable education, and their levels of work engagement. These elements are to be understood as interacting subsystems within the broader educational context. The findings are expected to identify system-level gaps, provide data-driven insights for decision-makers, and illustrate how the integration of machine learning and systems thinking can enhance sustainability and performance in educational systems globally.

2. Materials and Methods

The quantitative research method allows the researcher to generalize and claims about a population by examining a sample of a given population [

55]. Thus, this method was chosen, as this study aims to explore the relationship between science teachers’ views on the sustainability of education in Turkey and their work engagement. Furthermore, among the quantitative research methods, the Correlational Survey Model was considered suitable for this study as it helps to uncover the relationship or effect between two or more quantitative variables [

56]. This study aims to consider the relationship among three variables.

2.1. Research Hypotheses

Teachers’ demographic characteristics function as structural variables that influence their perceptions of sustainable education within the broader educational system.

Teachers’ demographic characteristics function as structural variables that influence their levels of work engagement as a human-centered subsystem of the education system.

Teachers’ demographic characteristics and their levels of work engagement interact to shape systemic perceptions of sustainable education, indicating an interdependent relationship between personal and contextual subsystems.

Teachers’ demographic characteristics and their perceptions of sustainable education interact to influence their engagement levels, reflecting a feedback mechanism that reinforces system sustainability and adaptability.

2.2. Population/Sample

Since the study was designed with a quantitative method, the population was determined first. Accordingly, the population of the study consists of science teachers working in public schools under the Ministry of National Education (MoNE) in Turkey. The sample of the study consists of 246 teachers working in public schools in Turkey. Science teachers were specifically chosen for the sample. Purposeful sampling was used due to the inclusion of sustainable development topics in science curriculum, Turkey’s low performance in science in international exams, and one of the researchers’ particular interests in the field. Additionally, maximum diversity was aimed at considering variables such as gender, age, type of settlement where they work, geographical region of employment, years of service, average number of course hours in the last two years, and education level. Demographic information of the teachers who volunteered to participate in the study is presented in

Table 1.

In order to address the concerns regarding the global applicability of the findings, it is essential to contextualize the chosen sample within the broader educational landscape. Beyond the demographic composition, the selection of this specific sample carries broader systemic implications. While the present study focuses on Turkish science teachers, the findings carry broader implications for global education systems. The Turkish education system, with its highly centralized management structure, offers a distinctive perspective on the internalization of top-down sustainability mandates by primary agents, namely teachers. In view of the fact that science curricula in Turkey are increasingly aligned with international frameworks such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, the structural dynamics identified in this study may offer valuable insights to other OECD countries facing similar systemic transitions.

2.3. Data Collection Tools to Be Used in the Study

In the study, a demographic information form prepared by the researchers and two different scales was used.

2.3.1. Demographic Information Form

This form was designed by researchers to collect information from teachers who agreed to participate in the study. It includes questions on gender, age, type of settlement where they live, geographic region of employment, years of service, average number of course hours in the past two years, and educational background.

2.3.2. Sustainable Education Scale

Developed by Çam-Tosun and Söğüt, this scale consists of 19 items [

12]. The results of the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) revealed a four-factor structure that explains 71.812% of the total variance. The four dimensions of the scale are “Equity in Education”, “Inclusivity in Education”, “Quality in Education”, and “Democratic Education”. The scale was designed in a five-point Likert format. For model-data fit, the results were χ

2 = 408.476 and df (degrees of freedom) = 146. Based on these values, χ

2/df = 2.79. The results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) showed GFI (Goodness of Fit Index) = 0.98, CFI (Comparative Fit Index) = 0.99, NFI (Normed Fit Index) = 0.98, NNFI (Non-Normed Fit Index) = 0.99, and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = 0.078, indicating CFI value suggests excellent model fit, while the RMSEA and SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) values suggest acceptable model fit. Strong relationships were observed between the factors and the items they comprise. Reliability analyses showed that Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.92 for the overall scale, and the Composite Reliability (CR) was 0.89. The scores on the scale range between 19 and 95. Higher scores on the scale indicate that participants have positive views on sustainable education in their country.

2.3.3. Engaged Teacher Scale (ETS)

The scale was originally developed in English by Klassen, Yerdelen, and Durksen and later adapted into Turkish by Yerdelen, Durksen, and Klassen [

30]. Designed in a seven-point Likert format, the scale allows participants to choose responses ranging between “never” to “always.” The scale consists of 16 items and has four-factor structure. These factors are emotional engagement, cognitive engagement, social engagement with students, and social engagement with colleagues. The results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) results (

χ2 (98) = 32.29,

p < 0.05; CFI = 0.98; GFI = 0.93; NFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.036; RMSEA = 0.059; 90% CI = 0.049, 0.069) indicate a good model fit. Cronbach’s alpha values for the subdimensions ranged between 0.79 and 0.87.

2.4. Data Analysis

The demographic information of the participants and their responses to the two scales were organized into a 246 × 42 matrix. This matrix consists of the responses of 246 participants to seven demographic information (gender, age, geographical region of employment, type of settlement where they work, years of service, education level, and average number of course hours in the last two years), 19 items of the Sustainable Education Scale, and 16 items of the Engaged Teacher Scale. The matrix was reduced to 246 × 9 size by taking the demographic information of the participants, the sum of the answers given to the Sustainable Education Scale and the sum of the answers given to the Engaged Teacher Scale. There is no missing data in the matrix. Descriptive data for the scales are presented in

Table 2.

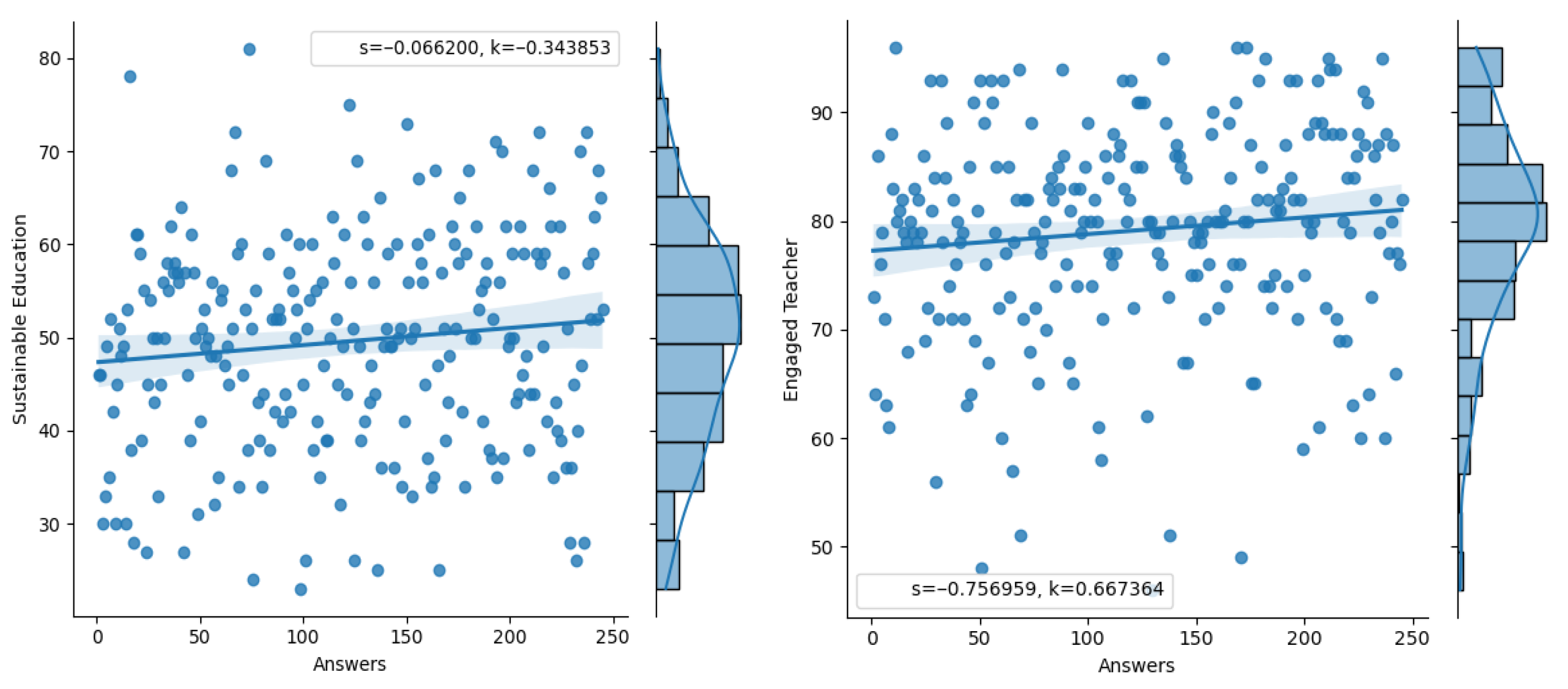

To identify potential outliers, the frequency of the minimum and maximum responses given to the scales was examined. As a result, participants 1 and 183 were identified as outliers in the Sustainable Education Scale, while participant 1 was identified as an outlier in the Engaged Teacher Scale. Consequently, these two participants were excluded from the study. After removing the outliers, the study was carried out on a 244 × 9 matrix. To determine whether the data followed a normal distribution, skewness and kurtosis values were calculated using the SciPy (ver. 1.6.1) library with Python (ver. 3.9.0) programming. Figures related to the normal distribution of the data, including histograms, normal distribution curves, and linear regression curves, were generated using the SeaBorn (ver. 0.13.2) library and are presented in

Figure 2.

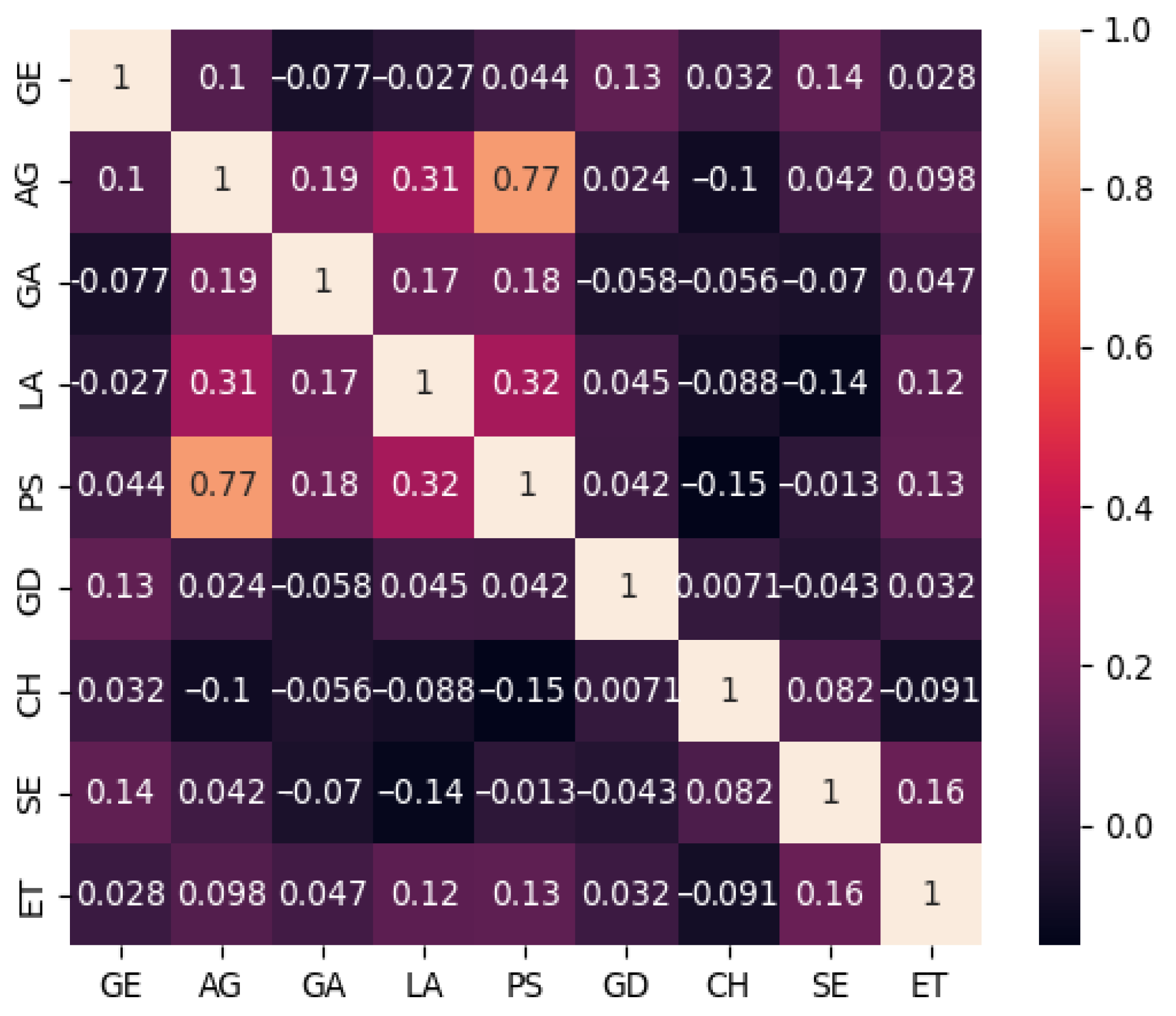

Since the skewness and kurtosis values of both scales are within ±1 range, the data is considered to follow a normal distribution, as seen in the figures. To numerically express the linear relationship between demographic data, views on sustainable education, and teachers’ views on work engagement, a correlation matrix was produced. To enhance visual interpretation of the correlation matrix, a heatmap was generated and integrated using the Seaborn library. The correlation matrix is presented in

Figure 3 below.

In addition to the correlation matrix, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) linear analysis was also performed for all hypotheses of the study, to see whether there was a linear relationship between the data. OLS Regression results are given in

Table 3.

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 and

Table 3, the linear regression lines and the values in the correlation matrix, R2 scores, F statistics, Log-Likelihood scores and Durbin–Watson scores clearly indicate that there is no significant linear relationship between the data. shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, the linear regression lines and the values in the correlation matrix clearly indicate that there is no significant linear relationship between the data. For this reason, non-linear regression models, commonly used in machine learning methods, were considered appropriate for the analysis in this study to explain the relationships between the data. Linear regression models aim to identify linear relationships between the data. However, this assumption is often ineffective in real-life applications. Therefore, instead of searching for a linear relationship between the data, non-linear models that provide a better fit to the data tend to provide more successful results in explaining the relationships. In particular, ensemble learning models are better fit when explaining the relationships between data because they do not use all the independent variables simultaneously [

57]. Thus, non-linear ensemble machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest, CART, Extra Tree, and Bagging Regression methods were selected for the study, and their performance in explaining the data was evaluated. In order to process the data, normalization was applied, scaling the values between 0 and 1 (Equation (1)). The Scikit library was used for the normalization process.

Machine learning algorithms were applied using the Scikit library. To prevent the overfitting problem, the maximum depth and criterion parameters of the CART and Extra Tree models were set to 12 and squared error, respectively. The estimator parameter of the Bagging and Random Forest models was set to 50. Additionally, the Random Forest maximum depth parameter was similarly limited to 12. Apart from this, no grid or random parameter search was performed to determine the best parameters of the models, and the remaining parameters of the models were used with their default values in the Scikit library. To ensure robustness and to tackle overfitting, 5-fold cross validation was also applied to machine learning models. In each fold, ML models were trained with 80% of the dataset and the models were validated with the remaining 20% of the dataset, which was unseen. Performance of ML models were evaluated by averaging validation scores of each cross-validation folds using R2 and RMSE (Root Mean Square Error). R2 measures how well a statistical model predicts an outcome while RMSE represents the average Euclidean distance between each actual data point and the predictions made by the machine learning model in regression problems. Comparisons were made to assess the extent to which the selected machine learning models explained the dataset. Feature importance is examined to find non-linear relationships between data and to examine the variables that affect the success of ML models. Feature importance measures how much each feature contributes to the model’s prediction accuracy. This ensures that the variable that contributes most to finding the predicted value is found.

In summary, in line with the systems-oriented and exploratory aims of this study, machine learning techniques were employed to identify non-linear relationships, interaction effects, and latent patterns among structural system variables and dynamic system states. The use of machine learning was intended for pattern discovery rather than causal inference, particularly in contexts where linear assumptions may obscure emergent system-level dependencies. R2 values were interpreted as indicators of predictive fit consistent with the cross-sectional design of the study. Ensemble-based algorithms were selected due to their capacity to reduce variance and stabilize predictions in small/moderate-sized datasets. Therefore, neural network-based machine learning methods, which require large amounts of data, have not been used in this study. While conventional statistical methods remain appropriate for hypothesis testing under linear assumptions, the present study adopts a systems-sensitive analytical approach in which machine learning complements traditional models by revealing complex interaction structures that may inform future longitudinal and theory-driven research.

Prior to data collection, approval was obtained from the ethics committee. The ethical feasibility of the study was approved by the Sinop University Human Research Ethics Committee on the 18th of September 2024, with the decision numbered 2024/261. The data was collected electronically. After providing participants with information about the study, informed consent was obtained before they were asked to complete the scales. Teachers who volunteered to participate in the study completed the scales online between 2 October 2024 and 6 November 2024.

3. Results

To test the first hypothesis that teachers’ demographic information is related to their views on the presence of sustainable education in their countries, analyses were conducted using non-linear ensemble machine learning algorithms, specifically Random Forest, CART, Extra Tree, and Bagging Regression. The findings obtained from these analyses are presented in

Table 4.

R2 has a value between 0 and 1, with value closer to 1 indicating that the regression model fits the data well. When examining the R2 values of the non-linear regression machine learning models trained to analyze the relationship between demographic information and teachers’ views on sustainable education, it was observed that the CART and Extra Tree regression models provided a better fit to the data. Similarly, the RMSE value, which measures the error rate between the actual data and the predicted values of the regression model at the end of the training, also showed that these two models fit the data better than the other two models.

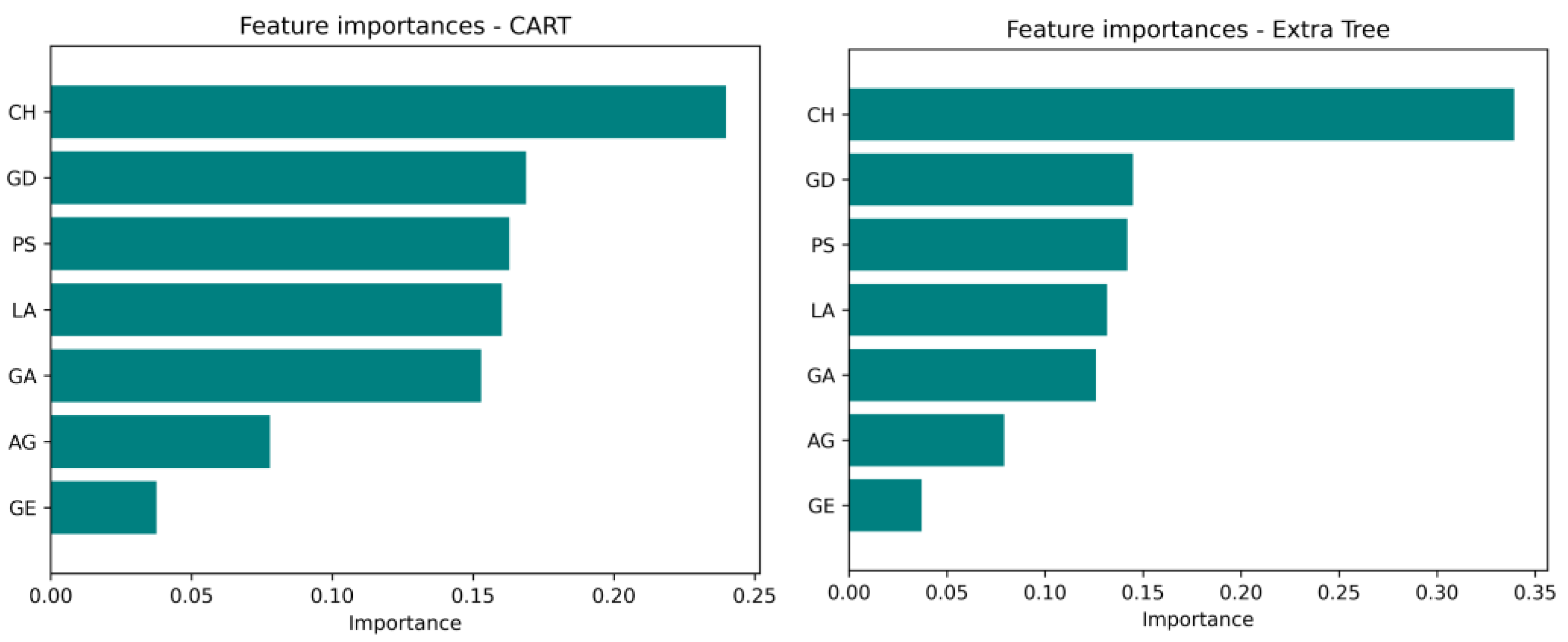

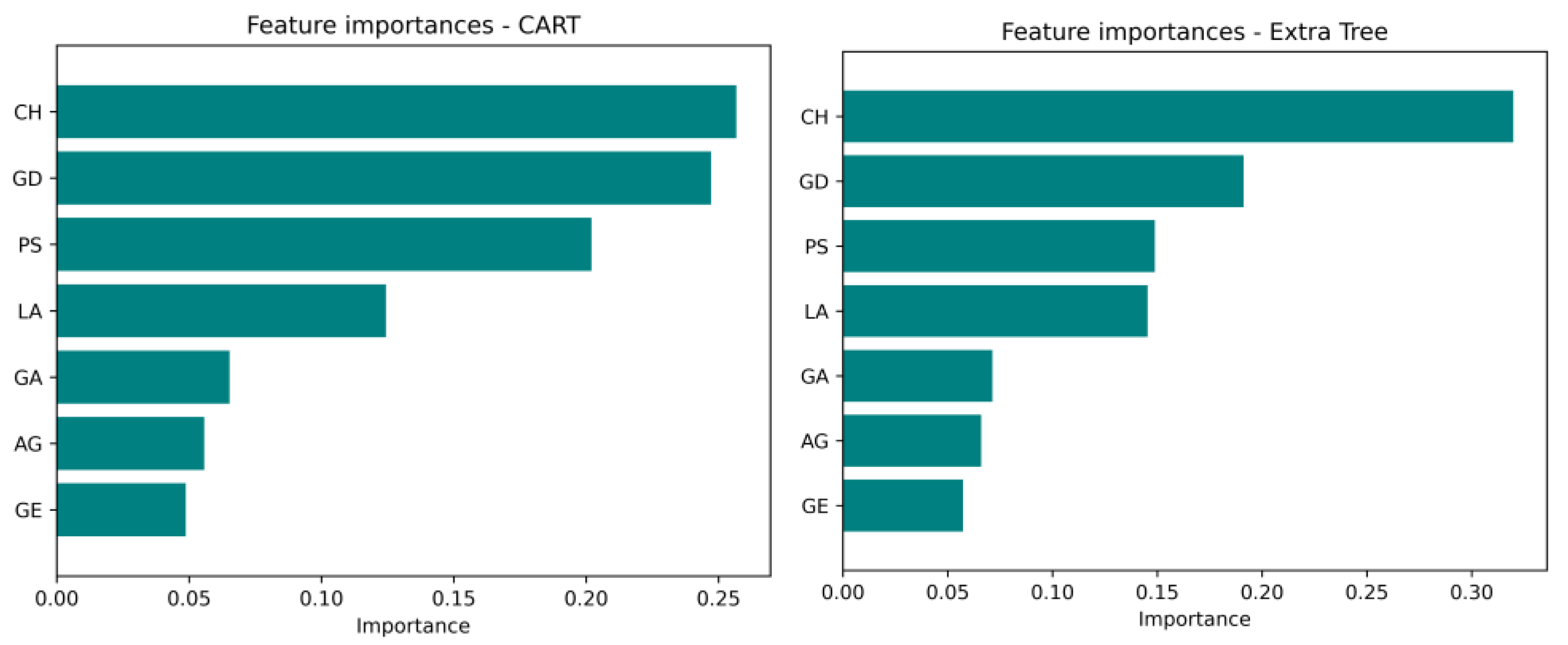

To examine which demographic variables contribute the most to models’ sustainable education prediction results, a feature importance analysis was conducted using the two most successful machine learning models. The results of the analysis are presented in

Figure 4 below.

Accordingly, both methods produced the same ranking of demographic variables in terms of importance. The most influential variable affecting teachers’ views on sustainable education was the weekly course hours. The following variables in order of importance are degree of graduation and years of service. The least influential variable was gender. In the Extra Tree regression, the importance level of the weekly course hours’ variable was found to be higher compared to the CART regression.

The findings obtained from the non-linear regression analysis conducted to test the second hypothesis, which examines the relationship between teachers’ demographic information and their views on work engagement, are presented in

Table 5.

As seen in

Table 5, the R

2 values indicate that the CART and Extra Tree regression models fit the data better. Similarly, the RMSE values, at 0.11, show that these models provide a better fit to the data compared to the other two models.

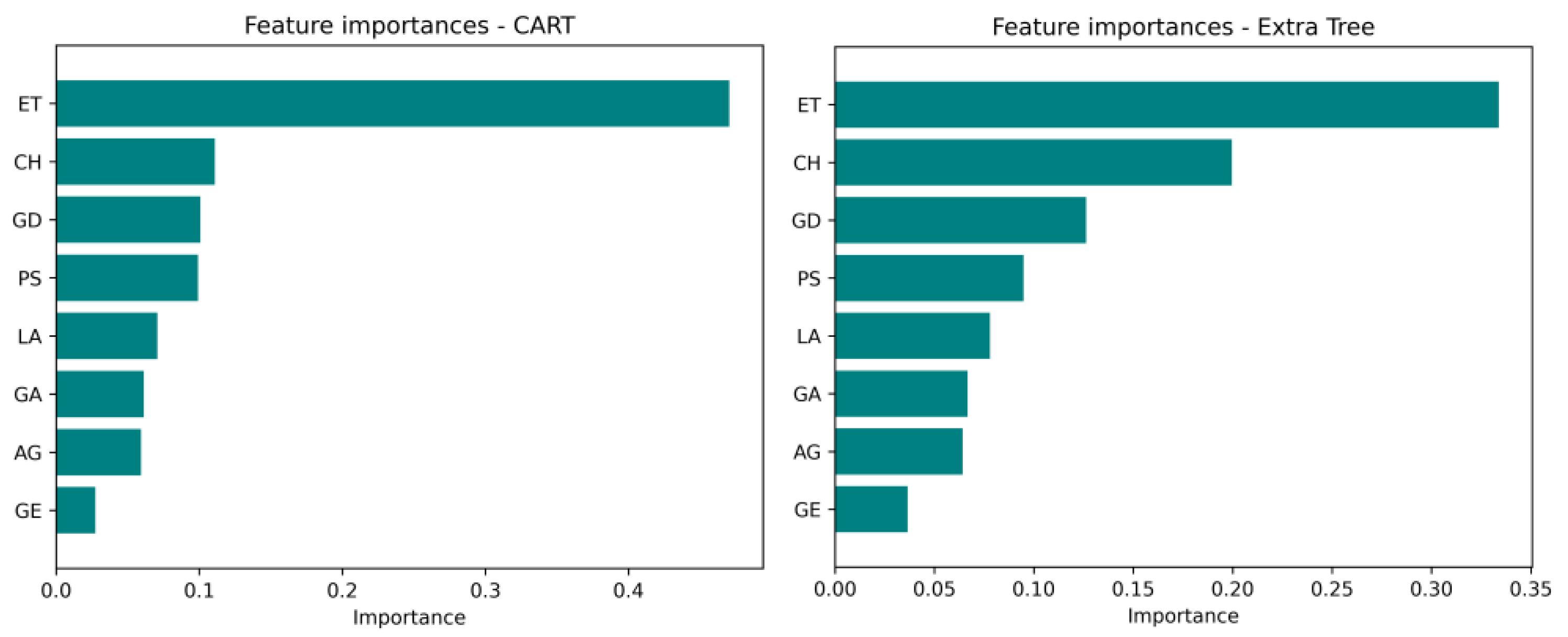

The feature importance analysis conducted to determine which demographic variables contribute the most to the models’ work engagement results is presented in

Figure 5.

Among the demographic variables, the weekly course hours were found to have the greatest contribution to models’ work science teachers’ engagement results. In the Extra Tree regression, the importance level was found to be higher. The second most influential variable on work engagement, according to both methods, was the degree of graduation. However, in the CART regression, the importance level was quite high and close to that of weekly course hours. In the Extra Tree regression, the importance level appeared to have reduced by half. The least influential variable was gender.

The findings obtained from the non-linear regression analysis conducted to test the third hypothesis, which examines the relationship between teachers’ demographic information, besides their views on work engagement, and their views regarding sustainable education in their countries, are presented in

Table 6.

When demographic variables and work engagement were considered together, the R

2 values indicated that their contribution to teachers’ views on sustainable education is high. In particular, the CART and Extra Tree regression models provided a good fit for the data (R

2 ≅ 0.87). The RMSE values also indicated a high level of fit. The results of the feature importance analysis conducted to assess the importance level of demographic variables and work engagement on the concept of sustainable education are presented in

Figure 6.

As seen in the figures, work engagement was found to be the most contributive variable at a high level. According to the CART regression, its importance level was much higher than that of the other variables. The next most influential variable was the weekly course hours. According to the Extra Tree regression model, weekly course hours had a higher contribution to the concept of sustainable education.

The findings obtained from the non-linear regression analysis conducted to test the final hypothesis, which examines relations between teachers’ demographic information besides their views on sustainable education in their countries and their views regarding work engagement, are presented in

Table 7.

When science teachers’ demographic information and their views on sustainable education were considered together, the R

2 value indicated that these factors can be very good indicators for work engagement. The high R

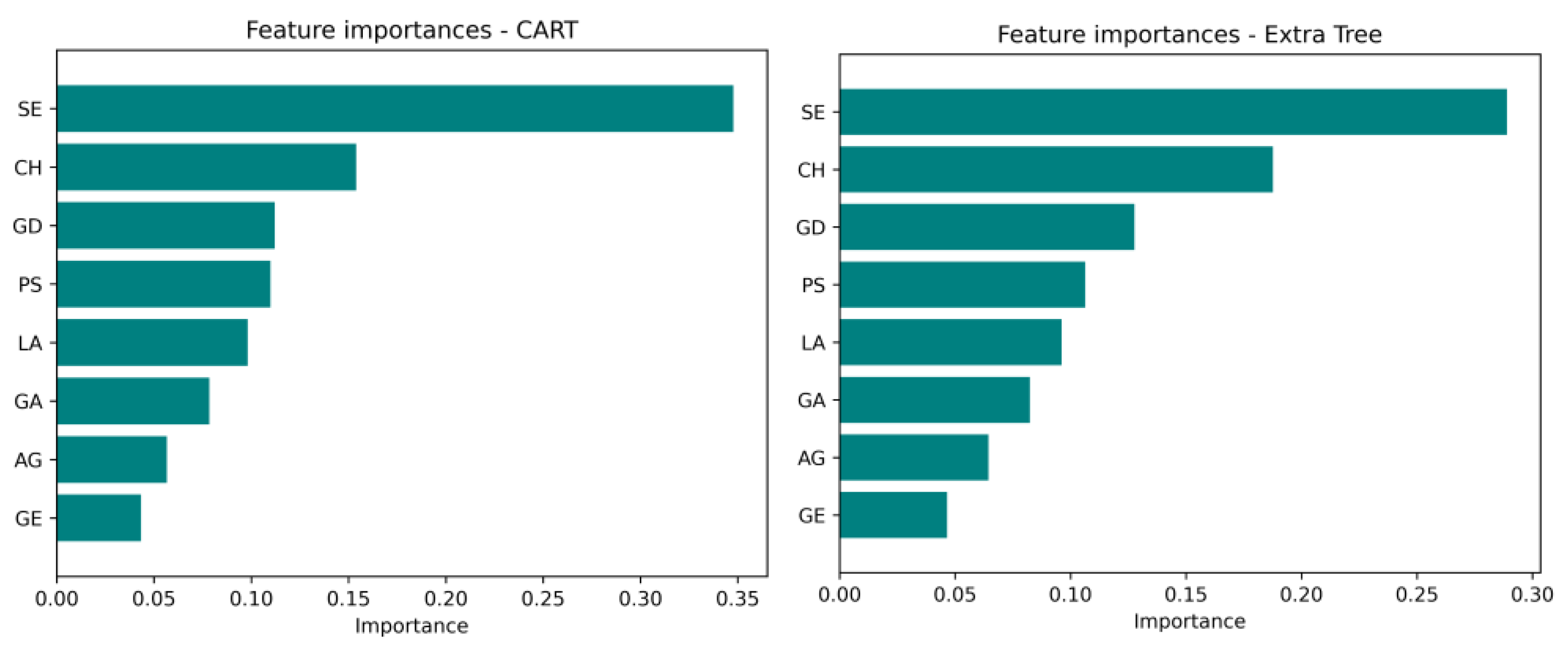

2 value indicates that CART and Extra Tree regression models were a good fit for the data. The RMSE value also indicated a good level of fit. The results of the feature importance analysis conducted to assess the contributions of demographic variables and the concept of sustainable education on work engagement are presented in

Figure 7.

In both regressions, the most influential variable contributing work engagement was found to be science teachers’ view on the presence of sustainable education in their countries. The importance levels of this variable were higher compared to the other variables. According to the research findings, all hypotheses were accepted. There is a mutual relationship between work engagement and views on sustainable education.

4. Discussion

This study employed machine learning techniques to examine the associations between demographic characteristics and science teachers’ views on the presence of sustainable education in their countries, as well as their work engagement. In addition, the study explored the relationship between teachers’ views on sustainable education and their work engagement. While the literature includes numerous studies investigating the role of educational programmes in fostering a sustainable environment, the present study conceptualizes sustainable education as a broader social phenomenon rather than as a direct outcome of specific educational interventions.

In this study, weekly course hours emerged as the most salient variable associated with science teachers’ views on sustainable education, followed by degree of graduation and years of service, whereas gender showed the weakest association. Research explicitly examining teachers’ views on sustainable education remains limited. A notable exception is the study by Çam-Tosun and Söğüt, who, in the process of developing the scale used in the present study, explored teachers’ views on sustainable education across different fields. In this study, sustainable education is conceptualized as the continuation of inclusive, equitable, democratic, and quality education for both present and future generations [

12]. From this perspective, the presence of sustainable education entails the adoption of new and increasingly complex professional roles by teachers [

58,

59]. These roles include providing high-quality instruction, fostering inclusivity and equity, and acting as role models in the creation of democratic learning environments. Developing such competencies may require substantial time and institutional support. Science teachers, in particular, aim to enhance educational quality not only through theoretical instruction but also through laboratory-based practical activities, which often demand additional preparation and instructional time. Prior research has also indicated that teachers working in inclusive classrooms require increased planning time and support from auxiliary staff [

60]. Within this context, the strong association observed between weekly course hours and teachers’ views on sustainable education may reflect the temporal and organizational demands inherent in implementing sustainable education practices, rather than a direct influence of course hours alone. Similarly, degree of graduation and years of service are commonly linked to teachers’ professional development trajectories. In the context of sustainable education, teachers are expected to address diverse learning needs, support students’ emotional and social development, and promote interaction and participation within the classroom [

61,

62,

63]. Advanced qualifications and accumulated professional experience may facilitate the development of these competencies. At the same time, these variables may also serve as proxies for broader system-level factors, such as access to professional learning opportunities or institutional support, which were not explicitly modeled in the present study.

In the study, weekly course hours and degree of graduation emerged as the variables most strongly associated with science teachers’ work engagement. Work engagement is commonly understood as a state of psychological fulfilment or self-actualization, and work intensity has been identified as one of the key factors related to work engagement [

64]. From the perspective of a sustainable and efficient education environment, sufficient time for rest and recovery constitutes an important contextual condition for teachers’ sustained engagement at work. The findings indicate that science teachers with higher weekly course hours tend to report lower levels of work engagement. This pattern may reflect the demands associated with increased workload and reduced opportunities for recovery, rather than a direct influence of course hours alone. Degree of graduation, reflecting engagement in postgraduate studies for professional and personal development beyond undergraduate education, also emerged as a salient variable associated with work engagement. Although the literature does not provide clear evidence predicting a systematic relationship between degree of graduation and work engagement, advanced qualifications may be linked to broader professional capacities, such as enhanced self-efficacy. Teachers with higher levels of self-efficacy are known to contribute more actively to school improvement processes, which may be reflected in their levels of work engagement.

From a systems dynamics perspective, both the perception of sustainable education and work engagement function as interconnected reinforcing feedback loops emerging from the continuous interaction between teachers and the educational environment. However, excessive weekly course hours impose a structural constraint that forces teachers into a ‘survival mode,’ effectively inhibiting these feedback mechanisms and disrupting the internalization of sustainability mandates along with professional engagement. While demographic factors such as age or region may modulate the rate of these systemic processes, workload serves as a critical systemic regulator capable of halting the loops entirely, which explains its dominant predictive power for both engagement and sustainability perceptions in the non-linear machine learning models

The findings of the study indicate a close relationship between science teachers’ work engagement and their views on the presence of sustainable education. Within a systems perspective, sustainable education environments are characterized by their capacity to cope with uncertainty and unexpected conditions, as well as by structures that foster continuous learning. These characteristics position sustainable education as a paradigm that integrates behavioral and cognitive dimensions [

65,

66]. In this sense, sustainable education environments emphasize the alignment of educational policies, objectives, content, and processes with the needs of both present and future generations [

67]. From this perspective, teachers may perceive their professional roles as extending beyond their current students to future generations, potentially enhancing the perceived meaningfulness of their work. Prior research suggests that meaningful work is closely linked to work satisfaction and engagement, which may help explain the observed relationship between teachers’ views on sustainable education and their work engagement. In addition, flexible thinking has been identified as a critical component of sustainability in education [

68,

69]. Core elements of sustainability (such as social learning and adaptability [

70], learning to learn, lifelong learning [

66], and creativity) are widely regarded as essential for coping with uncertainty [

67]. The literature further indicates that role ambiguity is associated with increased stress, discomfort, and fear among employees, alongside reduced work commitment and self-efficacy [

71,

72]. In this context, sustainable education environments (by emphasizing clarity of purpose, adaptability, and shared learning) may be meaningfully associated with teachers’ levels of work engagement, although no direct causal relationship can be inferred from the present findings.

Another potential explanation for the observed relationship between work engagement and views on a sustainable education environment can be found in Foster’s concepts of close relationships and belief-based social networks, which were proposed to support social sustainability in education [

73]. Both concepts emphasize inclusivity and multiculturalism, which constitute key ontological and epistemological foundations of sustainable education [

74]. Inclusive and multicultural education is commonly defined as the elimination of exclusionary practices in education based on race, religion, language, gender, social status, academic achievement, or disability. In order to foster inclusive and intercultural educational environments, researchers have argued that teachers need to take into account students’ individual and group identities to ensure equal educational opportunities, a process that has been associated with improved academic outcomes [

75,

76,

77]. Within this framework, teachers are expected to assume professional roles that integrate social values with pedagogical effectiveness and that are compatible with the principles of sustainable education [

78,

79]. In such contexts, teachers who perceive that all students have equitable access to educational opportunities and that learners from diverse backgrounds can achieve comparable levels of success may be more likely to report higher levels of work engagement. Furthermore, the creation of inclusive and intercultural educational environments also requires schools to adopt a broader sustainable perspective, including enhanced collaboration among teachers and improved communication with students [

74,

80]. Consistent with this view, the strong association observed between social participation (particularly teacher–student communication) and work engagement suggests that sustainable education environments are closely linked to teachers’ engagement at work, without implying a direct causal relationship.

Sustainable education further envisions an environment in which democratic values are cultivated among students, teachers, and educational administrators. This process extends beyond teachers’ participation in school-level decision-making and includes their role as models of democratic practice and facilitators of democratic classroom environments [

81]. Democratic educational settings may provide teachers with greater opportunities for professional growth, self-expression, and meaningful participation in their work. Existing research indicates that inclusive decision-making processes in policy development and supportive leadership practices are associated with higher levels of teacher work engagement [

82] and with increased energy and enthusiasm toward professional tasks [

83].

Ethical Considerations and Model Interpretability

The integration of machine learning within educational systems demands a stringent adherence to principles of transparency and ethical conduct. In this study, the issue of model interpretability is addressed through the use of impurity-based feature importance scores, which serve as an Explainable AI mechanism to reveal the underlying logic of the predictive models. However, it is crucial to emphasize that these algorithmic insights should be utilized for systemic improvement, such as identifying workload constraints, rather than for individual teacher evaluations. In order to circumvent the risks associated with ‘algorithmic governance’, it is imperative that the findings of this study be incorporated into comprehensive policy frameworks that accord precedence to teacher professional development and system resilience in comparison to the implementation of punitive monitoring.

5. Conclusions

In this study, non-linear ensemble learning algorithms were utilized to examine the relationship between science teachers’ work engagement and their views on sustainable education. The employment of machine learning methodologies has facilitated the discernment of intricate patterns that transcend the limitations of conventional analytical techniques. This novel approach has unveiled systemic dependencies that have hitherto been overlooked within the extant literature. This study provides a foundational step in supporting teacher motivation and sustainable education on a global scale, offering insights into how teacher-related data under different conditions can predict work engagement. The findings of this study offer valuable data-driven evidence for policymakers in the effective management of performance and educational resources.

The analysis revealed that science teachers’ views on sustainable education and their work engagement are primarily predicted by structural variables such as weekly course hours, degree of graduation, and years of service, while gender showed the least predictive weight. A high-level integration was observed when demographic variables were combined with either work engagement or sustainability perceptions, showing that these factors collectively contribute to the system’s overall state. The findings of this study indicate a strong correlation between teachers’ workloads and levels of education, on the one hand, and their engagement and sustainability outlooks, on the other. The study under discussion highlights a reinforcing feedback loop between the following factors: the removal of structural barriers that hinder teacher engagement is essential for the realization of sustainable education, which in turn sustains professional motivation.

Rather than proposing a new theoretical paradigm, this study contributes empirical and methodological insights into how system-level relationships and feedback dynamics can be examined using machine learning within educational systems. When interpreting the findings of this study, it is important to maintain a degree of epistemic modesty. While the machine learning models employed here provide high predictive accuracy, they represent a data-driven approximation of a highly complex and fluid socio-technical system. The identified patterns of teacher engagement and sustainability perceptions should be viewed as probabilistic systemic tendencies rather than deterministic causal pathways. Consequently, while the evidence provides a robust foundation for policy formulation, its application is contingent upon the specific cultural and temporal context of the data. It is recommended that future research endeavors involve the testing of these patterns across a range of educational settings. This would serve to provide further validation of the boundaries of these claims.

In order to achieve more reliable results with machine learning approaches in the field of educational research, further studies with larger datasets are required. The factors that contribute to teachers’ work engagement, the barriers they face, and the factors that influence their views on sustainable education should also be explored qualitatively.