Toward a Sustainable Paradigm: Redefining Corporate Purpose in the EU Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Relationship Between Business and Society

2.2. The Concept of Corporate Purpose

2.3. Models of Corporate Purpose

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Selected Variables

3.3. Research Methods

- represents the distance between countries i and j,

- , are the variable values for countries i and j,

- p is the number of analyzed variables.

- —outputs,

- —weights,

- —inputs,

- b—bias,

- f—activation function.

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Empirical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial neural networks |

| CS | Candriam Score |

| NC | Natural Capital |

| HC | Human Capital |

| SC | Social Capital |

| EC | Economic Capital |

| SDGi | SDG Index Score |

References

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Jordi, C.L. Rethinking the Firm’s Mission and Purpose. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2010, 7, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C.; Ronnegard, D. Shareholder Primacy, Corporate Social Responsibility, and the Role of Business Schools. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, C. Whose Company Is It Anyway? The Benefits of Unprotected Capitalism and Unruly Shareholders; Institute for Economic Affairs: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Reed, D.L. Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1983, 25, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.S.; Phillips, R.A.; Freeman, R.E. On the 2019 Business Roundtable Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 1223–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C. The Future of the Corporation and the Economics of Purpose. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartenberg, C.; Serafeim, G. Corporate Purpose in Public and Private Firms. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 5087–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.D.; Mota, R. A Theory of Organizational Purpose. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2023, 48, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.; Van den Steen, E. Why Do Firms Have Purpose? The Firm’s Role as a Carrier of Identity and Reputation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartenberg, C.M.; Prat, A.; Serafeim, G. Corporate Purpose and Financial Performance. Organ. Sci. 2019, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R. Innovation in the 21st Century: Architectural Change, Purpose, and the Challenges of Our Time. Manag. Sci. 2020, 67, 5479–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unilever. Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan. Available online: https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Patagonia. Patagonia’s Mission and Values. Available online: https://www.patagonia.com/company-info/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Smith, W.K.; Besharov, M.L. Bowing before Dual Gods: How Structured Flexibility Sustains Organizational Hybridity. Adm. Sci. Q. 2019, 64, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. The New Political Role of Business in a Globalized World: A Review of New Perspectives on CSR and Its Implications for the Firm, Governance, and Democracy. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 899–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, R. Supercapitalism: The Transformation of Business, Democracy, and Everyday Life; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karnani, A. Doing Well by Doing Good: The Grand Illusion. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, T.A.; Monin, B. Doing Well by Doing Good? Ambivalent Moral Framing in Organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2011, 31, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreck, P. Reviewing the Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: New Evidence and Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, P. Integrative Economic Ethics: Foundations of a Civilized Market Economy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, D. The Market for Virtue: The Potential and Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abend, G. The Moral Background: An Inquiry into the History of Business Ethics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sunny, F.A.; Jeronen, E.; Lan, J. Influential Theories of Economics in Shaping Sustainable Development Concepts. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.S.; Siegel, D. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Theory of the Firm Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, A. Why ‘Doing Well by Doing Good’ Went Wrong: Getting Beyond ‘Good Ethics Pays’ Claims in Managerial Thinking. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 512–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Crane, A. Corporate Citizenship: Towards an Extended Theoretical Conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. Toward a Political Conception of Corporate Responsibility: Business and Society Seen through a Habermasian Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1096–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endörfer, R.; Larue, L. What’s the Point of Efficiency? On Heath’s Market Failures Approach. Bus. Ethics Q. 2024, 34, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempels, T.; Blok, V.; Verweij, M. Understanding Political Responsibility in Corporate Citizenship: Towards a Shared Responsibility for the Common Good. J. Glob. Ethics 2017, 13, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.; Palazzo, G.; Basu, K. Reconsidering Instrumental Corporate Social Responsibility through the Mafia Metaphor. Bus. Ethics Q. 2009, 19, 57–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, C.A.; Ghoshal, S. Changing the Role of Top Management: Beyond Strategy to Purpose. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1994, 72, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Thakor, A.V.; Quinn, R.E. The Economics of Higher Purpose; ECGI–Finance Working Paper 395; Olin Business School, Washington University: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-W.; Fu, M.-W. Conceptualizing Sustainable Business Models Aligning with Corporate Responsibility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, D.; Franco, I.B.; Smith, T. A Review of Corporate Purpose: An Approach to Actioning the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2021, 13, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C. Ownership, Agency, and Trusteeship. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, N. Corporate Purpose: From a ‘Tower of Babel’ Phenomenon towards Construct Clarity. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 93, 567–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabetino, R.; Kohtamäki, M.; Foss, N.J.; Rahman, N.; Huikkola, T. Microfoundations for Business Model Innovation: Exploring the Interplay Between Individuals, Practices, and Organizational Design. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2025, 42, 704–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmié, M.; Rüegger, S.; Parida, V. Microfoundations in the Strategic Management of Technology and Innovation: Definitions, Systematic Literature Review, Integrative Framework, and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blader, S.; Gartenberg, C.; Prat, A. The Contingent Effect of Management Practices; Working Paper; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, R.; Rushing, H. It’s Not What You Sell, It’s What You Stand for: Why Every Extraordinary Business Is Driven by Purpose; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Haas, M.R.; McGahan, A.M.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.D.; Tracey, P. Purpose in the For-Profit Firm: A Review and Framework for Management Research. J. Manag. 2023, 49, 1841–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantar Consulting. Purpose 2020: The Journey Towards Purpose-Led Growth. Available online: https://www.kantar.com/Inspiration/Brands/The-Journey-Towards-Purpose-Led-Growth (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Hollensbe, E.; Wookey, C.; Hickey, L.; George, G.; Nichols, C.V. Organizations with Purpose. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, W.; Begnini, S.; Abreu, I. The Paradox of Trust: How Leadership, Commitment, and Inertia Shape Sustainability Behavior in the Workplace. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilje, E.P.; Taillard, J.P. Do Private Firms Invest Differently than Public Firms? Taking Cues from the Natural Gas Industry. J. Financ. 2016, 71, 1733–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, N.E.; Kawano, L.; Patel, E.; Rao, N.; Stevens, M.; Edgerton, J. The Long and the Short of It: Do Public and Private Firms Invest Differently? Working Paper 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doidge, C.; Kahle, K.M.; Karolyi, G.A.; Stulz, R.M. Eclipse of the Public Corporation or Eclipse of the Public Markets? J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2018, 30, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohll, A. What Employees Really Want at Work. Forbes, 10 July 2018. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/alankohll/2018/07/10/what-employees-really-want-at-work/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value: How to Reinvent Capitalism and Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R. Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Edmans, A. Grow the Pie: How Great Companies Deliver Both Purpose and Profit; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.L. Why Would Corporations Behave in Socially Responsible Ways? An Institutional Theory of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Martin, K.E.; Parmar, B.L. The Power of AND: Responsible Business Without Trade-Offs; Columbia Business School Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pache, A.C.; Santos, F. When Worlds Keep on Colliding: Exploring the Consequences of Organizational Responses to Conflicting Institutional Demands. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 640–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oino, I.; Yekini, S. Meeting Stakeholder Needs: Who Should Managers Pay Close Attention To? Evidence from Listed Chinese Manufacturing Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutua, K.; Powell-Turner, J.; Spiers, M.; Callaghan, J. An In-Depth Analysis of Barriers to Corporate Sustainability. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J. Cracking the Organizational Challenge of Pursuing Joint Social and Financial Goals: Social Enterprise as a Laboratory to Understand Hybrid Organizing. M@N@Gement 2018, 21, 1278–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Obloj, T.; Pache, A.-C.; Sengul, M. Beyond Shareholder Value Maximization: Accounting for Financial/Social Trade-Offs in Dual-Purpose Companies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2022, 47, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Raynard, M.; Kodeih, F.; Micelotta, E.; Lounsbury, M. Institutional Complexity and Organizational Responses. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 317–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S.; Bartlett, C.; Moran, P. A New Manifesto for Management. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1999, 40, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.; Winter, S.G. (Eds.) The Nature of the Firm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aljebrini, A.; Dogruyol, K.; Ahmaro, I.Y.Y. How Strategic Planning Enhances ESG: Evidence from Mission Statements. Sustainability 2025, 17, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.F.; Costa, C.G.d.; Ramos, F.R. Exploring Purpose-Driven Leadership: Theoretical Foundations, Mechanisms, and Impacts in Organizational Context. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, A.J.; Warglien, M.; George, G. A Simulation-Based Approach to Business Model Design and Organizational Change. Innov. Organ. Manag. 2021, 23, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, A.; Illanes, P.; Probst, N.; Schaninger, B.; Simpson, B. Purpose: Shifting from Why to How; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, K.J. Rationality of Self and Others in an Economic System. J. Bus. 1986, 4, S385–S399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, W. Authentic Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dacin, M.T.; Dacin, P.A.; Tracey, P. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J. Finding Purpose: Environmental Stewardship as a Personal Calling; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kraatz, M.S.; Block, E.S. Institutional Pluralism Revisited. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, 2nd ed.; Greenwood, R., Oliver, C., Lawrence, T.B., Meyer, R.E., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2017; pp. 532–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwath, R.; Drucker, P. Discovering Purpose: Developing Mission, Vision & Values; Strategic Thinking Institute: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zervoudi, E.K.; Moschos, N.; Christopoulos, A.G. From the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Criteria to the Greenwashing Phenomenon: A Comprehensive Literature Review About the Causes, Consequences and Solutions of the Phenomenon with Specific Case Studies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemčok, M.; Im, Z.J.; Grasso, M.; Bonomi Bezzo, F. Public Opinion and the Welfare State: Sources, Processes, and Consequences. J. Eur. Public. Policy 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, Z.; Kühner, S. Towards a Theorization of the Global Community Welfare Regime: Depicting Four Ideal Types of the Community’s Role in Welfare Provision. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2025, 35, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Su, C.; Peng, J.; Yang, Z. Trust in Inter-Organizational Relationships: A Meta-Analytic Integration. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1050–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S. Bad Management Theories Are Destroying Good Management Practices. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2005, 4, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, R.K.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.D.; Blakstad, S. Sustainable Digital Finance in Asia: Creating Environmental Impact Through Bank Transformation; Sustainable Digital Finance Alliance; UN Environment: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.dbs.com/iwov-resources/images/sustainability/reports/Sustainable%20Digital%20Finance%20in%20Asia_FINAL_22.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Schillebeeckx, S.J.D.; Kautonen, T.; Hakala, H. To Buy Green or Not to Buy Green: Do Structural Dependencies Block Ecological Responsiveness? J. Manag. 2021, 48, 472–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourov, K.; Van Hyfte, W. Sovereign Sustainability Report 2022: The Age of the Grey Swan; Candriam: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://www.candriam.com/siteassets/medias/publications/brochure/research-papers/sustainability-in-the-age-of-the-grey-swan/2022_11_sovereign_report_en_web.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Iablonovski, G. Financing Sustainable Development to 2030 and Mid-Century. Sustainable Development Report 2025; SDSN: Paris, France; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Capitalism and Freedom; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Rudeloff, C.; Michalski, P. How Corporate Brands Communicate Their Higher Purpose on Social Media: Evidence from Top Global Brands on Twitter. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2024, 27, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hörisch, J.; Freeman, E. Business Cases for Sustainability: A Stakeholder Theory Perspective. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and B Corps. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waal, J.W.H.; Thijssens, T.; Maas, K. The Innovative Contribution of Multinational Enterprises to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkovics, N.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Archie-Acheampong, J. The Business Responsibility Matrix: A Diagnostic Tool to Aid the Design of Better Interventions for Achieving the SDGs. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHares, A. Ethical Leadership and Its Impact on Corporate Sustainability and Financial Performance: The Role of Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, L.; Tallarita, R. The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance. Working Paper, April. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/03/02/the-illusory-promise-of-stakeholder-governance/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Issue | Traditional Model | Goal-Based Purpose Model | Duty-Based Purpose Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Focus | Profit maximization and economic efficiency. | Aligning corporate purpose with mission statements, vision, and strategic goals. | Ethical and moral responsibilities, including social, human, and environmental impacts. |

| Primary Objective | Increase shareholder value and financial returns. | Achieve specific organizational goals and reflect a unique corporate identity. | Contribute positively to society and address broader social, environmental, and ethical issues. |

| Approach to Profit | Profit is the main goal; other considerations are secondary. | Profit is a means to fulfill the broader purpose, including but not limited to financial goals. | Profit is one of many goals, with a focus on overall impact and responsibility beyond financial gain. |

| Stakeholder Consideration | Limited focus on stakeholders beyond shareholders; often perceived as a zero-sum game. | Stakeholders are considered in the context of achieving organizational goals and balancing various interests. | Emphasizes responsibility to all stakeholders, including communities and the environment. |

| Ethical and Social Dimensions | Minimal integration of ethical or social dimensions; focus on economic outcomes. | Incorporates ethical considerations, but primarily through the lens of achieving organizational objectives. | Central to the purpose are ethical behavior and societal contributions. |

| Impact Evaluation | Success is measured by financial performance and shareholder returns. | Success is evaluated based on the achievement of organizational goals and the alignment with stated purposes. | Success is measured by the positive impact on society and the environment, as well as financial performance. |

| Variable | Datasets | Measures | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS | Candriam Score | Aggregate score (0 to 100) | [84] |

| NC | Natural Capital | Score (not rebased from 0 to 100) | [84] |

| HC | Human Capital | Score (not rebased from 0 to 100) | [84] |

| SC | Social Capital | Score (not rebased from 0 to 100) | [84] |

| EC | Economic Capital | Score (not rebased from 0 to 100) | [84] |

| SDGi | SDG Index Score | Aggregate score (0 to 100) | [85] |

| Variable | N | Min. | Max. | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 27 | 44.26 | 100.00 | 70.2644 | 16.00629 | 0.098 | −1.254 |

| NC | 27 | 30.75 | 98.00 | 60.8993 | 20.08270 | 0.182 | −1.262 |

| HC | 27 | 21.24 | 98.00 | 56.6726 | 20.18428 | 0.234 | −0.908 |

| SC | 27 | 25.23 | 99.00 | 58.2719 | 21.39849 | 0.251 | −1.079 |

| EC | 27 | 21.69 | 100.00 | 56.0819 | 21.80932 | 0.210 | −1.143 |

| SDGi | 27 | 72.50 | 86.80 | 80.1630 | 3.29453 | −0.093 | 0.456 |

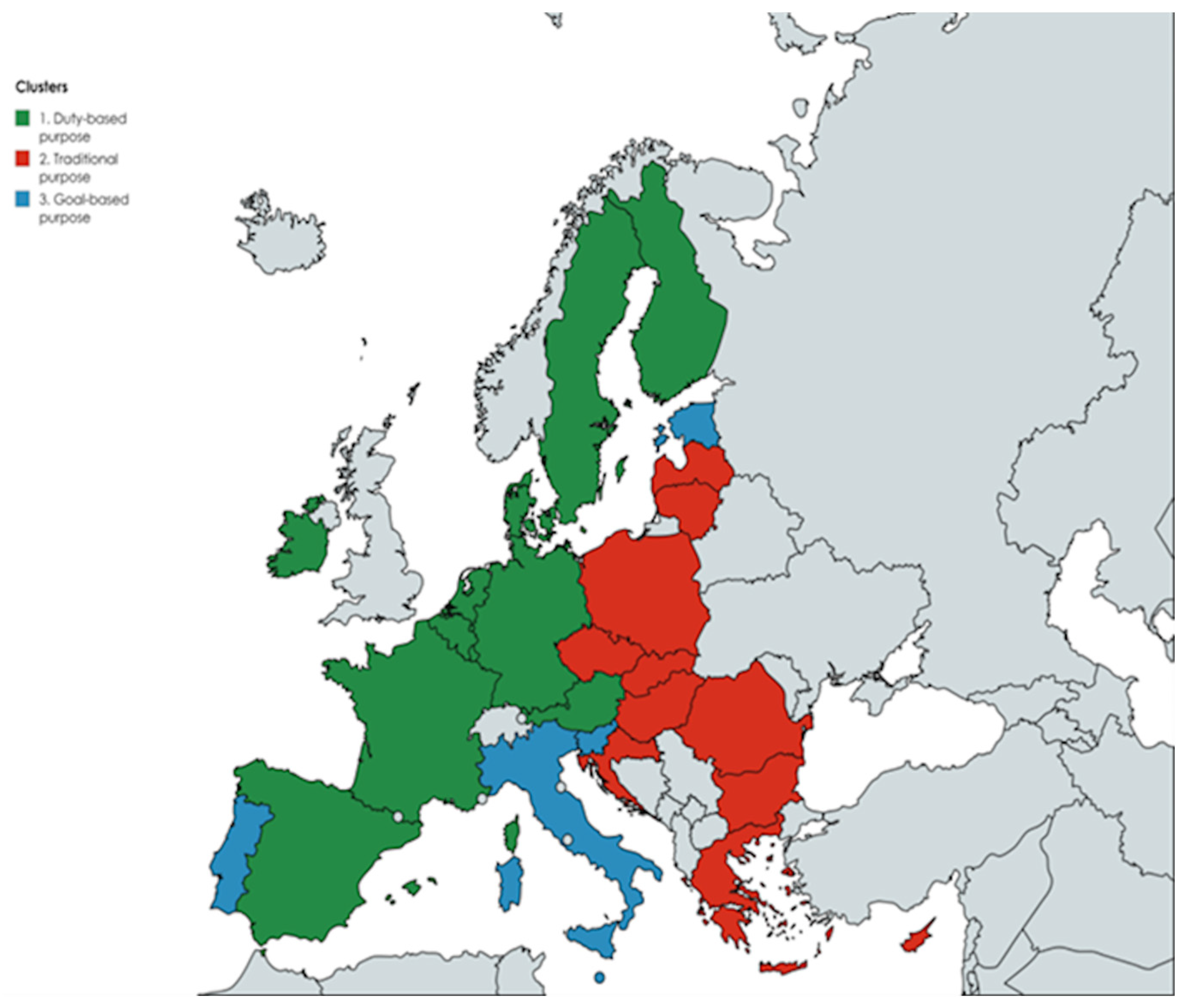

| Country | CS | NC | HC | SC | EC | SDGi | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 82.65 | 77.69 | 72.73 | 76.04 | 70.25 | 82.3 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Belgium | 80.98 | 73.69 | 68.02 | 72.07 | 70.45 | 79.5 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Denmark | 100.00 | 98.00 | 98.00 | 99.00 | 100.00 | 85.7 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Finland | 94.68 | 92.79 | 85.21 | 92.79 | 87.11 | 86.8 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| France | 84.00 | 81.48 | 72.24 | 70.56 | 75.60 | 82.0 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Germany | 85.06 | 79.11 | 81.66 | 74.85 | 80.81 | 83.4 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Ireland | 83.84 | 79.65 | 70.43 | 74.62 | 68.75 | 80.1 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Luxembourg | 92.14 | 85.69 | 85.69 | 92.14 | 76.48 | 77.6 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Netherlands | 82.16 | 73.12 | 78.05 | 80.52 | 74.77 | 79.4 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Spain | 81.04 | 74.56 | 59.16 | 64.83 | 77.80 | 80.4 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Sweden | 87.52 | 86.64 | 77.89 | 83.14 | 85.77 | 86.0 | 1 (duty-based purpose) |

| Cluster 1 mean | 86.73 | 82.04 | 77.19 | 80.05 | 78.89 | 82.11 | |

| Bulgaria | 48.04 | 30.75 | 28.34 | 27.38 | 29.30 | 74.6 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Croatia | 56.89 | 40.96 | 38.12 | 40.96 | 40.39 | 81.5 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Cyprus | 57.44 | 41.93 | 39.06 | 40.78 | 44.23 | 72.5 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Greece | 55.98 | 39.19 | 34.15 | 38.07 | 40.87 | 78.4 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Hungary | 54.55 | 46.91 | 38.19 | 34.91 | 37.09 | 79.4 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Latvia | 51.45 | 39.62 | 37.04 | 38.59 | 33.44 | 80.7 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Lithuania | 56.28 | 45.02 | 39.40 | 43.34 | 37.14 | 76.8 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Poland | 50.94 | 38.21 | 38.21 | 33.62 | 32.60 | 81.8 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Romania | 44.26 | 30.98 | 21.24 | 25.23 | 21.69 | 77.5 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Slovakia | 54.48 | 45.76 | 43.58 | 37.59 | 26.15 | 79.1 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Czechia | 60.90 | 48.72 | 49.94 | 48.11 | 35.32 | 81.9 | 2 (traditional purpose) |

| Cluster 2 mean | 53.75 | 40.73 | 37.02 | 37.14 | 34.38 | 78.22 | |

| Estonia | 75.69 | 56.01 | 58.28 | 65.09 | 47.68 | 81.7 | 3 (goal-based purpose) |

| Italy | 67.14 | 56.40 | 50.36 | 47.00 | 54.38 | 78.8 | 3 (goal-based purpose) |

| Malta | 70.18 | 61.06 | 56.14 | 56.14 | 60.35 | 75.5 | 3 (goal-based purpose) |

| Portugal | 72.74 | 65.47 | 57.46 | 61.10 | 58.19 | 80.0 | 3 (goal-based purpose) |

| Slovenia | 66.11 | 54.87 | 51.57 | 54.87 | 47.60 | 81.0 | 3 (goal-based purpose) |

| Cluster 3 mean | 70.37 | 58.76 | 54.76 | 56.84 | 53.64 | 79.40 | |

| UE mean | 70.26 | 60.90 | 56.67 | 58.27 | 56.08 | 80.16 |

| Predictor | Predicted | Importance | Normalized Importance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hidden Layer 1 | Output Layer | ||||

| H (1:1) | SDGi | ||||

| Input Layer | (Bias) | 0.082 | |||

| NC | 0.449 | 0.236 | 58.6% | ||

| HC | 0.485 | 0.292 | 72.4% | ||

| SC | 0.645 | 0.404 | 100.0% | ||

| EC | 0.146 | 0.068 | 16.9% | ||

| Hidden Layer 1 | (Bias) | −0.342 | |||

| H (1:1) | 0.905 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bocean, C.G.; Vărzaru, A.A. Toward a Sustainable Paradigm: Redefining Corporate Purpose in the EU Context. Systems 2026, 14, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010039

Bocean CG, Vărzaru AA. Toward a Sustainable Paradigm: Redefining Corporate Purpose in the EU Context. Systems. 2026; 14(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleBocean, Claudiu George, and Anca Antoaneta Vărzaru. 2026. "Toward a Sustainable Paradigm: Redefining Corporate Purpose in the EU Context" Systems 14, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010039

APA StyleBocean, C. G., & Vărzaru, A. A. (2026). Toward a Sustainable Paradigm: Redefining Corporate Purpose in the EU Context. Systems, 14(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010039