Is Homeownership Beneficial for Rural-to-Urban Migrants’ Access to Public Health Services? Exploring Housing Disparities Within Urban Health Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Homeownership and Migrants’ Access to Public Health Services

2.2. Migrants’ Urban Integration as a Mediation Mechanism

2.2.1. The Mediating Role of Migrants’ Perception of Acculturation

2.2.2. The Mediating Role of Migrants’ Community Participation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Variables

3.3. Analytical Procedure

4. Research Results

4.1. Baseline Analysis Using Binary Logit Regression Model

4.2. Robustness Assessment of Baseline Analysis Results

4.2.1. Check of Reverse Causality

4.2.2. Correction of Self-Selection Bias

- (1)

- Average treatment effect (ATE)Treatment group (homeowner): weight = 1/PSControl group (renter): weight = 1/(1 − PS)

- (2)

- Average treatment effect on the treated (ATT)Treatment group (homeowner): weight = 1Control group (renter): weight = PS/(1 − PS)

- (3)

- Average treatment effect on the untreated (ATU)Treatment group (homeowner): weight = (1 − PS)/PSControl group (renter): weight = 1

4.2.3. Test of Omitted Variable Bias

4.3. Mechanism Analysis Results

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Study Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.3. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Yan, S.; Ma, M.; Tarimo, C.S.; Chen, Y.; Lai, Y.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Ye, B. Factors influencing health service utilization among 19,869 China’s migrant population: An empirical study based on the Andersen behavioral model. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1456839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawde, N.C.; Sivakami, M.; Babu, B.V. Utilization of maternal health services among internal migrants in Mumbai, India. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2016, 48, 767–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, Y.S.; Babu, B.V. Migration and health: A systematic review on health and health care of internal migrants in India. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlenberger, J.; Buber-Ennser, I.; Rengs, B.; Leitner, S.; Landesmann, M. Barriers to health care access and service utilization of refugees in Austria: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health Policy 2019, 123, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, C.; Massag, J.; Amorim, M.; Fraga, S. Involvement in maternal care by migrants and ethnic minorities: A narrative review. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.; Breislin, E. Comparing health service usage of migrant groups in Australia: Evidence from the household income and labour dynamics survey of Australia. J. Migr. Health 2024, 10, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthoopparambil, S.J.; Phelan, M.; MacFarlane, A. Migrant health and language barriers: Uncovering macro level influences on the implementation of trained interpreters in healthcare settings. Health Policy 2021, 125, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, M.; Anderson, J.R. Acculturation patterns and education of refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic literature review. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 67, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östergren, O.; Rehnberg, J.; Lundberg, O.; Miething, A. Disruption and selection: The income gradient in mortality among natives and migrants in Sweden. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, C.; Collinson, M.A.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; Gross, M.; Harawa, S.; Lurie, M.N.; Mukondwa, K.; Pheiffer, C.F.; Tollman, S.; Wang, R.; et al. Internal migration and health in South Africa: Determinants of healthcare utilisation in a young adult cohort. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q. Strengthening public health systems in China. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e987–e988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.D.; Tuval-Mashiach, R. Ethiopian emerging adult immigrants in Israel: Coping with discrimination and racism. Youth Soc. 2012, 44, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. The Primary Data of the 7th National Population Census. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901080.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Andersen, R.M. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med. Care 2008, 46, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Z.; Shao, L.; Lang, Y. A study on the factors influencing the utilization of public health services by China’s migrant population based on the Shapley value method. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, F.; Zhou, Q. Equality of public health service and family doctor contract service utilisation among migrants in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 333, 116148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. Does a Different Household Registration Affect Migrants’ Access to Basic Public Health Services in China? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z. Housing crowding and sleep health in urban China: A mediation analysis of psychosocial pathways using nationally representative data. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 384, 118523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Ming, J. The Relationship Between Homeownership and the Utilization of Local Public Health Services Among Rural Migrants in China: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 589038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, M.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Dong, Q. The land of homesickness: The impact of homesteads on the social integration of rural migrants. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Housing cost burden, homeownership, and self-rated health among migrant workers in Chinese cities: The confounding effect of residence duration. Cities 2023, 133, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Social integration as a mediator of the association between housing tenure and health inequalities among China’s migrants: A housing discrimination perspective. SSM-Popul. Health 2024, 25, 101614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, L. Housing tenure and type choices of urban migrants in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 1832–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wu, F.; Li, Z. Beyond neighbouring: Migrants’ place attachment to their host cities in China. Popul. Space Place 2021, 27, e2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Q.; You, H.; Wu, Q. Awareness, Utilization and Health Outcomes of National Essential Public Health Service Among Migrants in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 936275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, J.; Feng, B.; Kim, H.; Marwah, G. Evaluating Chinese migrant workers’ housing conditions by diarrhea disease prevalence. J. Public Health Policy 2025, 46, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Guo, W. Self-rated Health and Objective Health Status Among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China: A Healthy Housing Perspective. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2023, 42, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.E. Human Migration and the Marginal Man. Am. J. Sociol. 1928, 33, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Hou, H.; Sun, Y.; Huang, X.; Wei, L. Acculturation of rural–urban migrants in China: Strategies and determinants. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2024, 101, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Guo, W. Housing characteristics and health in urban China: A comparative study of rural migrants and urban locals. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, E.; Yuan, Y.; Gan, Y. Homeownership and happiness in urban China. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Said, R.; Goh, H.C.; Cao, Y. The Residential Environment and Health and Well-Being of Chinese Migrant Populations: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wu, F.; Li, Z. Social integration of migrants across Chinese neighbourhoods. Geoforum 2020, 112, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z. Host identity and consumption behavior: Evidence from rural–urban migrants in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Ling, L. Health service behaviors of migrants: A conceptual framework. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1043135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metersky, K.; Guruge, S.; Wang, L.; Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M.; Catallo, C.; Yang, L.; Salma, J.; Zhuang, Z.C.; Chahine, M.; et al. Transnational Healthcare Practices Among Migrants: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 3647–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markkula, N.; Cabieses, B.; Lehti, V.; Uphoff, E.; Astorga, S.; Stutzin, F. Use of health services among international migrant children—A systematic review. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, E.; Yan, Y.; Ji, S.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Shi, J.; Xu, T.; Gao, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S. The influences of acculturation strategies on physician trust among internal migrants in Shanghai, China: A cross-sectional study in 2021. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1506520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Intergroup contact theory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silke, C.; Brady, B.; Dolan, P.; Boylan, C. Social values and civic behaviour among youth in Ireland: The influence of social contexts. Ir. J. Sociol. 2020, 28, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ding, L.; Tang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, C. Effect of social integration on the establishment of health records among elderly migrants in China: A nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e034255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xu, S.; Aziz, N.; He, J.; Wang, Y. Dialect culture and the utilization of public health service by rural migrants: Insights from China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 985343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.F.; Luo, W.; Wang, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Zhou, F.; Sun, J.W.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhang, J.C.; Zhou, W. A dataset on the dynamic monitoring of health and family planning of China’s internal migrants: A multi-wave large-scale, national cross-sectional survey from 2009 to 2018. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 2023, 38, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, E. Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: Theory and evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2019, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, K.A.; Lin, Q.; Maroulis, S.; Mueller, A.S.; Xu, R.; Rosenberg, J.M.; Hayter, C.S.; Mahmoud, R.A.; Kolak, M.; Dietz, T.; et al. Hypothetical case replacement can be used to quantify the robustness of trial results. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, R.; Karlson, K.B.; Holm, A. Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects in Logit and Probit Models. Sociol. Methods Res. 2013, 42, 164–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wu, G.; Wang, H.; Aziz, N. How does choice of residential community affect the social integration of rural migrants: Insights from China. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, M. The effect of housing tenure on health status of migrant populations in China: Are health service utilization and social integration mediating factors? Arch. Public Health 2023, 81, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Li, X. The Association of Residence Permits on Utilization of Health Care Services by Migrant Workers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabbla, A.; Duijster, D.; Aartman, I.H.A.; Agyemang, C. Predictors of oral healthcare utilization and satisfaction among Indian migrants and the host population in the Netherlands. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Che, Y.; Bai, Y.; Liu, J. Sociodemographic disparities in the establishment of health records among 0.5 million migrants from 2014 to 2017 in China: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Coding | Homeowner (N = 27,453) | Renter (N = 104,662) | t-Test Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Deviation | |||

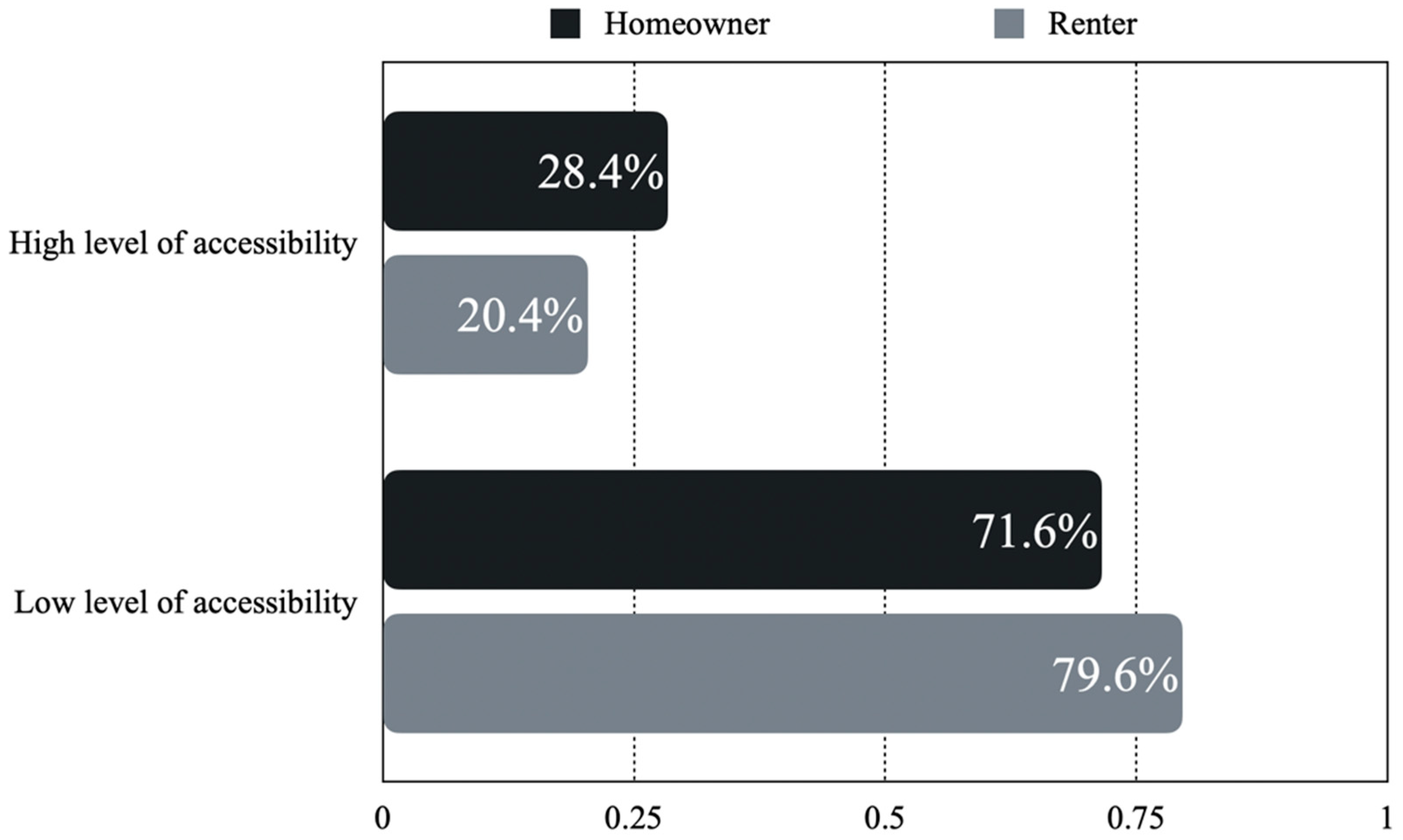

| Health services accessibility | high level = 1, low level = 0 | 0.284 | 0.451 | 0.204 | 0.403 | p < 0.01 |

| Gender | male = 1, female = 0 | 0.492 | 0.500 | 0.527 | 0.499 | p < 0.01 |

| Age | scaled in years | 37.685 | 10.825 | 35.893 | 10.676 | p < 0.01 |

| Ethnicity | ethnic Han = 1, ethnic minority = 0 | 0.929 | 0.257 | 0.892 | 0.310 | p < 0.01 |

| Education level | college or above = 1, high school or below = 0 | 0.181 | 0.385 | 0.093 | 0.290 | p < 0.01 |

| Marital status | married = 1, unmarried = 0 | 0.911 | 0.285 | 0.789 | 0.408 | p < 0.01 |

| Occupation | employer or self-employment = 1, employee or other status = 0 | 0.356 | 0.479 | 0.344 | 0.475 | p < 0.01 |

| Family income | monthly income scaled in Yuan | 8041.270 | 6696.525 | 6408.510 | 4549.026 | p < 0.01 |

| Health insurance | have = 1, not have = 0 | 0.930 | 0.255 | 0.924 | 0.265 | p < 0.01 |

| Self-reported health status | healthy = 1, unhealthy = 0 | 0.791 | 0.407 | 0.831 | 0.375 | p < 0.01 |

| Migration distance (reference group: inter-province) | inter-city within the province | 0.370 | 0.483 | 0.301 | 0.459 | p < 0.01 |

| inter-county within the city | 0.257 | 0.437 | 0.152 | 0.359 | p < 0.01 | |

| Migration time | scaled in years | 8.256 | 6.641 | 5.820 | 5.840 | p < 0.01 |

| Acculturation | range: 4 to 32 | 25.907 | 3.198 | 24.287 | 3.236 | p < 0.01 |

| Community participation | range: 0 to 100 | 15.692 | 17.041 | 12.226 | 15.357 | p < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core explanatory variable | |||

| Homeownership (renter = 0) | 0.436 *** (0.015) | 0.169 *** (0.018) | 0.052 *** (0.018) |

| Control variables | |||

| Gender (female = 0) | −0.146 *** (0.014) | −0.214 *** (0.015) | |

| Age | −0.003 *** (0.001) | −0.0005 (0.0008) | |

| Ethnicity (minority = 0) | −0.094 *** (0.025) | −0.113 *** (0.025) | |

| Education level (high school or below = 0) | 0.263 *** (0.023) | 0.059 ** (0.024) | |

| Marital status (unmarried = 0) | 0.333 *** (0.022) | 0.373 *** (0.023) | |

| Occupation (employee or other status = 0) | 0.003 (0.016) | 0.004 (0.016) | |

| Family income (logarithmic) | 0.019 (0.013) | −0.064 *** (0.014) | |

| Health insurance (not have = 0) | 0.461 *** (0.031) | 0.392 *** (0.031) | |

| Self-reported health status (unhealthy = 0) | 0.258 *** (0.019) | 0.203 *** (0.020) | |

| Migration distance (inter-province = 0) | |||

| Inter-city within the province | 0.110 *** (0.018) | 0.059 *** (0.018) | |

| Inter-county within the city | 0.165 *** (0.022) | 0.060 *** (0.023) | |

| Migration time | 0.023 *** (0.001) | 0.016 *** (0.001) | |

| Mediating mechanism variables | |||

| Acculturation | 0.080 *** (0.002) | ||

| Community participation | 0.022 *** (0.001) | ||

| Provincial dummy variables | uncontrolled | controlled | controlled |

| Log pseudolikelihood | −69,324.396 | −63,745.342 | −61,682.212 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.006 | 0.086 | 0.115 |

| Wald chi-square test | 796.760 *** | 10,041.220 *** | 13,561.310 *** |

| First-Stage Regression DV: Homeownership | Second-Stage Regression DV: Health Services Accessibility | |

|---|---|---|

| Homeownership | — | 0.956 *** (0.029) |

| Provincial homeownership rate | 0.923 *** (0.008) | — |

| Other variables | Controlled | Controlled |

| Error correlation test | athrho value = —0.329; p < 0.01 | |

| Wald test of exogeneity | chi-square value = 666.070; p < 0.01 | |

| Matching Methods | Treatment Group | Control Group | ATT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest neighbor matching (1:1) | 0.284 | 0.241 | 0.043 *** (t value = 10.270) |

| Nearest neighbor matching (1:5) | 0.284 | 0.238 | 0.046 *** (t value = 13.280) |

| Local linear regression matching | 0.284 | 0.231 | 0.053 *** (t value = 12.200) |

| Weighting Approaches | Homeownership’s Effect Estimation | Robust Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATE | 0.241 *** | 0.028 | [0.185, 0.297] |

| ATT | 0.198 *** | 0.020 | [0.160, 0.237] |

| ATU | 0.250 *** | 0.034 | [0.182, 0.317] |

| Effect Value | Standard Error | Contribution Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.174 *** | 0.018 | 100% |

| Direct effect | 0.052 *** | 0.018 | 29.9% |

| Indirect Path (a): Acculturation | 0.074 *** | 0.003 | 42.5% |

| Indirect Path (b): Community participation | 0.048 *** | 0.003 | 27.6% |

| Sum of indirect effect | 0.122 *** | 0.004 | Path (a) + Path (b) = 70.1% |

| Grouping (a): Gender | Grouping (b): Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Birth Before 1990 | Birth After 1990 | |

| Homeownership | 0.151 *** (0.025) | 0.185 *** (0.025) | 0.160 *** (0.019) | 0.187 *** (0.043) |

| Other variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.086 | 0.084 | 0.085 | 0.087 |

| Sample size | 68,705 | 63,410 | 101,652 | 30,463 |

| Coefficient difference test | Chi-square value = 0.880 p > 0.1 | Chi-square value = 0.330 p > 0.1 | ||

| Grouping (c): Family Income | Grouping (d): Migration Time | |||

| Low Income | High Income | Less Than Five Years | Five Years or More | |

| Homeownership | 0.229 *** (0.026) | 0.133 *** (0.024) | 0.285 *** (0.028) | 0.101 *** (0.023) |

| Other variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.084 | 0.089 | 0.083 | 0.086 |

| Sample size | 65,864 | 66,251 | 66,564 | 65,551 |

| Coefficient difference test | Chi-square value = 7.070 p < 0.01 | Chi-square value = 25.450 p < 0.01 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, P.; Tan, Q.; Hou, Y. Is Homeownership Beneficial for Rural-to-Urban Migrants’ Access to Public Health Services? Exploring Housing Disparities Within Urban Health Systems. Systems 2026, 14, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010040

Xu P, Tan Q, Hou Y. Is Homeownership Beneficial for Rural-to-Urban Migrants’ Access to Public Health Services? Exploring Housing Disparities Within Urban Health Systems. Systems. 2026; 14(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Peng, Qunli Tan, and Yu Hou. 2026. "Is Homeownership Beneficial for Rural-to-Urban Migrants’ Access to Public Health Services? Exploring Housing Disparities Within Urban Health Systems" Systems 14, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010040

APA StyleXu, P., Tan, Q., & Hou, Y. (2026). Is Homeownership Beneficial for Rural-to-Urban Migrants’ Access to Public Health Services? Exploring Housing Disparities Within Urban Health Systems. Systems, 14(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010040