Investigating Risky Behaviors and Safety Countermeasures for E-Bike Riders in China: A Traffic Conflict Analysis Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Report Questionnaire Survey

2.2. Crash Data Analysis

2.3. Naturalistic Cycling Study

2.4. Field Observation Study

3. Data Collection and Processing

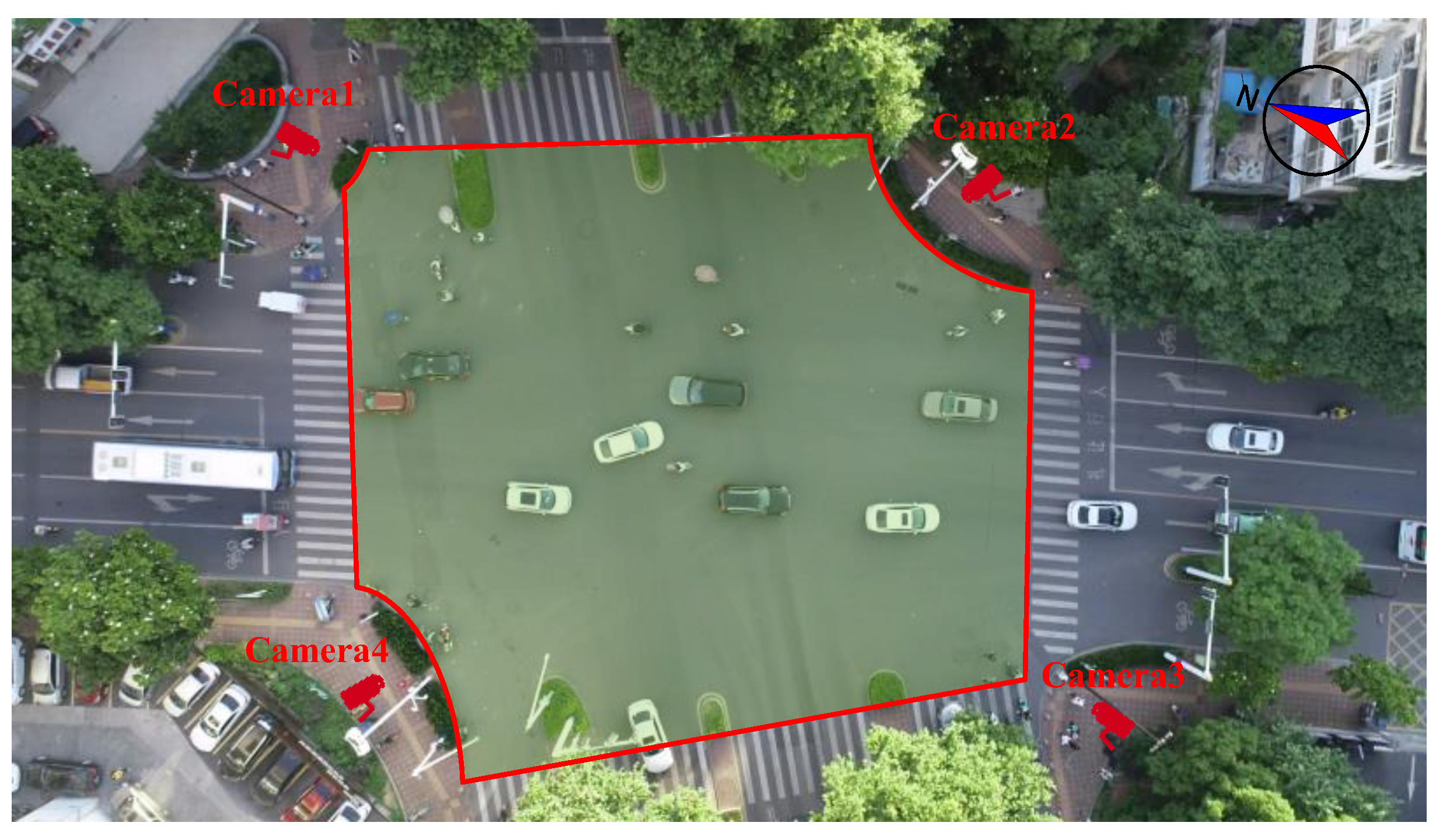

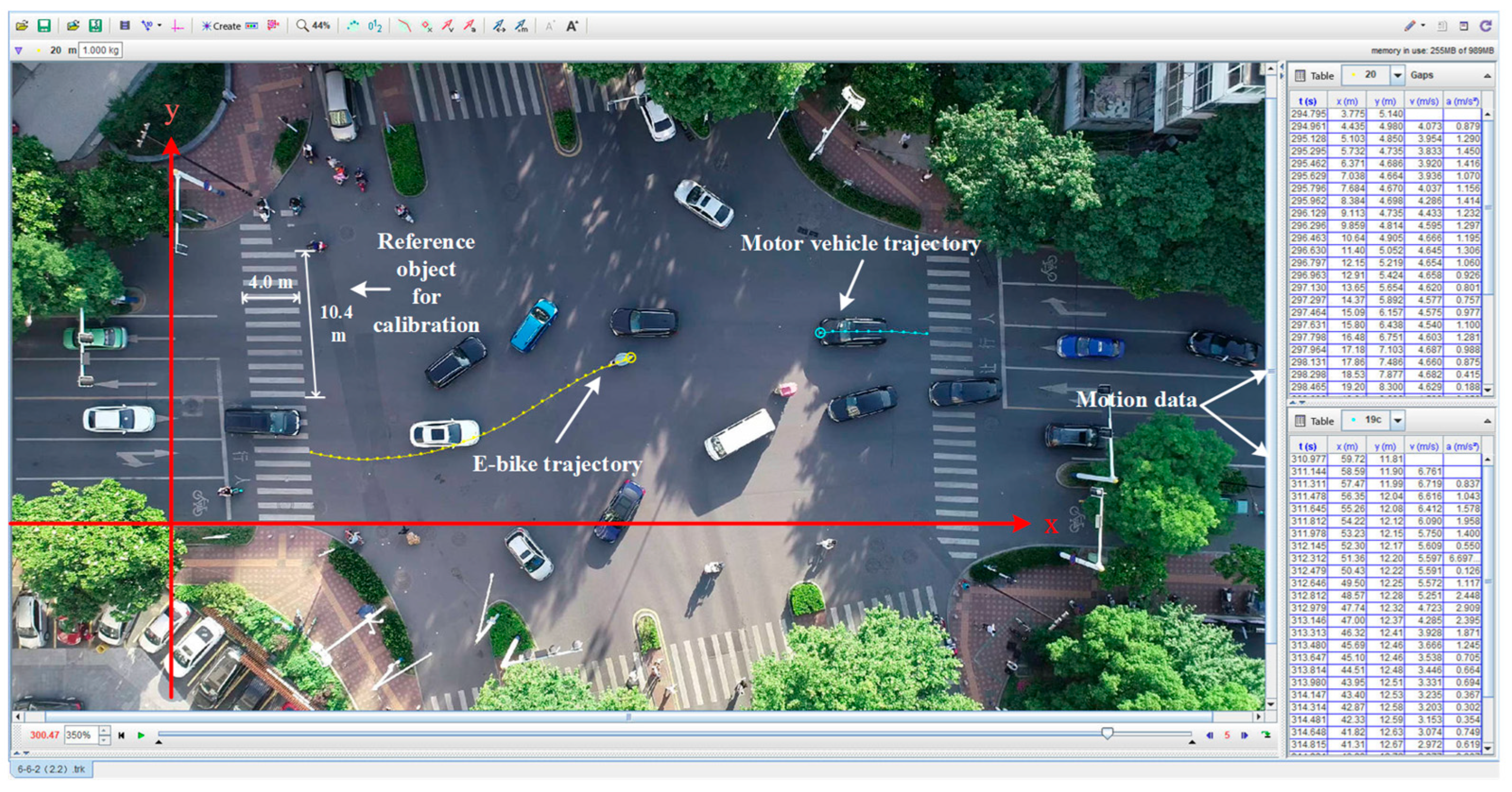

3.1. Site Selection

3.2. Data Collection

4. Methodology

4.1. Selection of Conflict Risk Indicators

4.2. Random Parameters Binary Logit Model with Heterogeneity in Means and Variances

5. Results

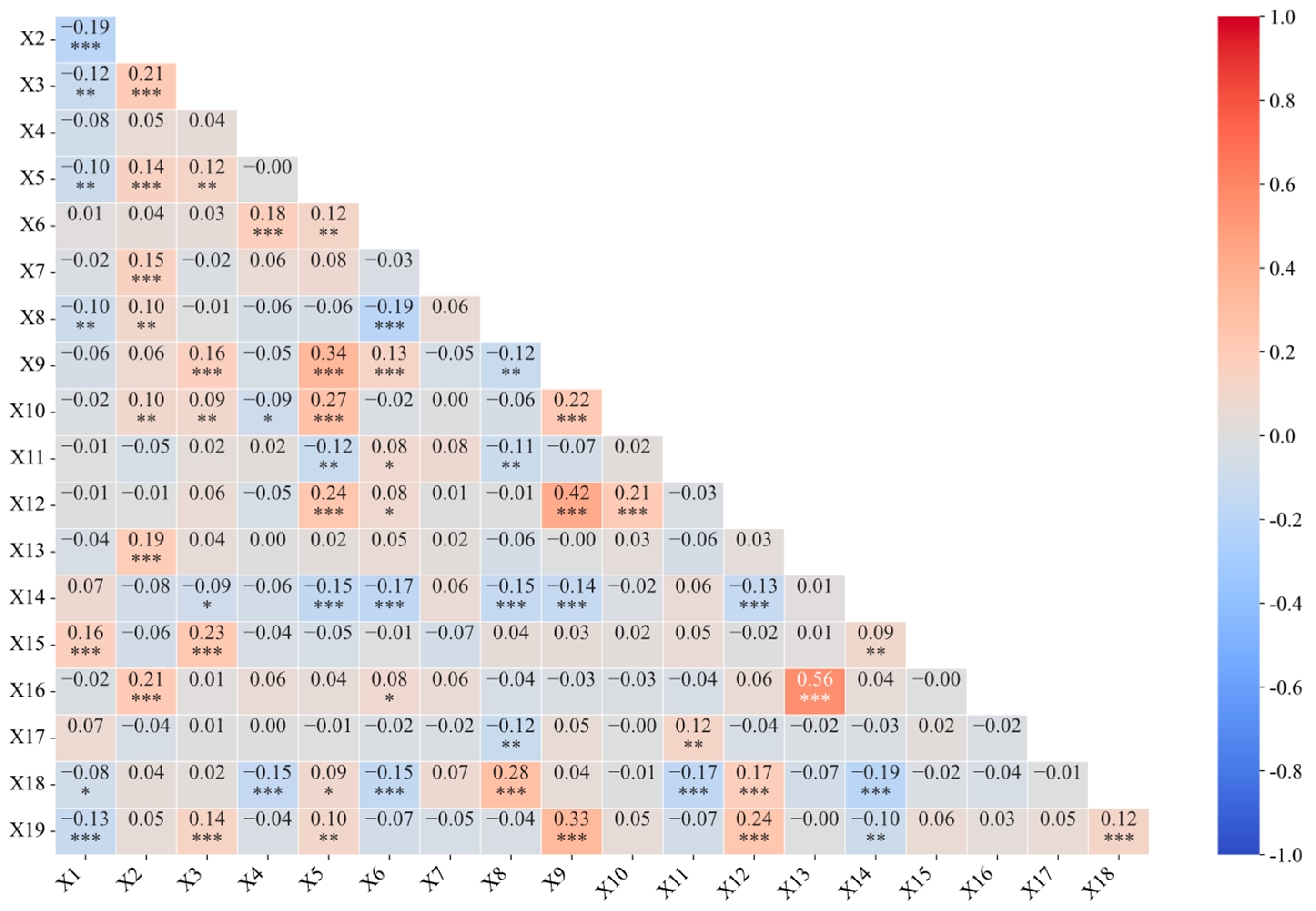

5.1. Descriptive Statistics of Conflict Data

5.2. Estimation Results of RPBL-HMV Model

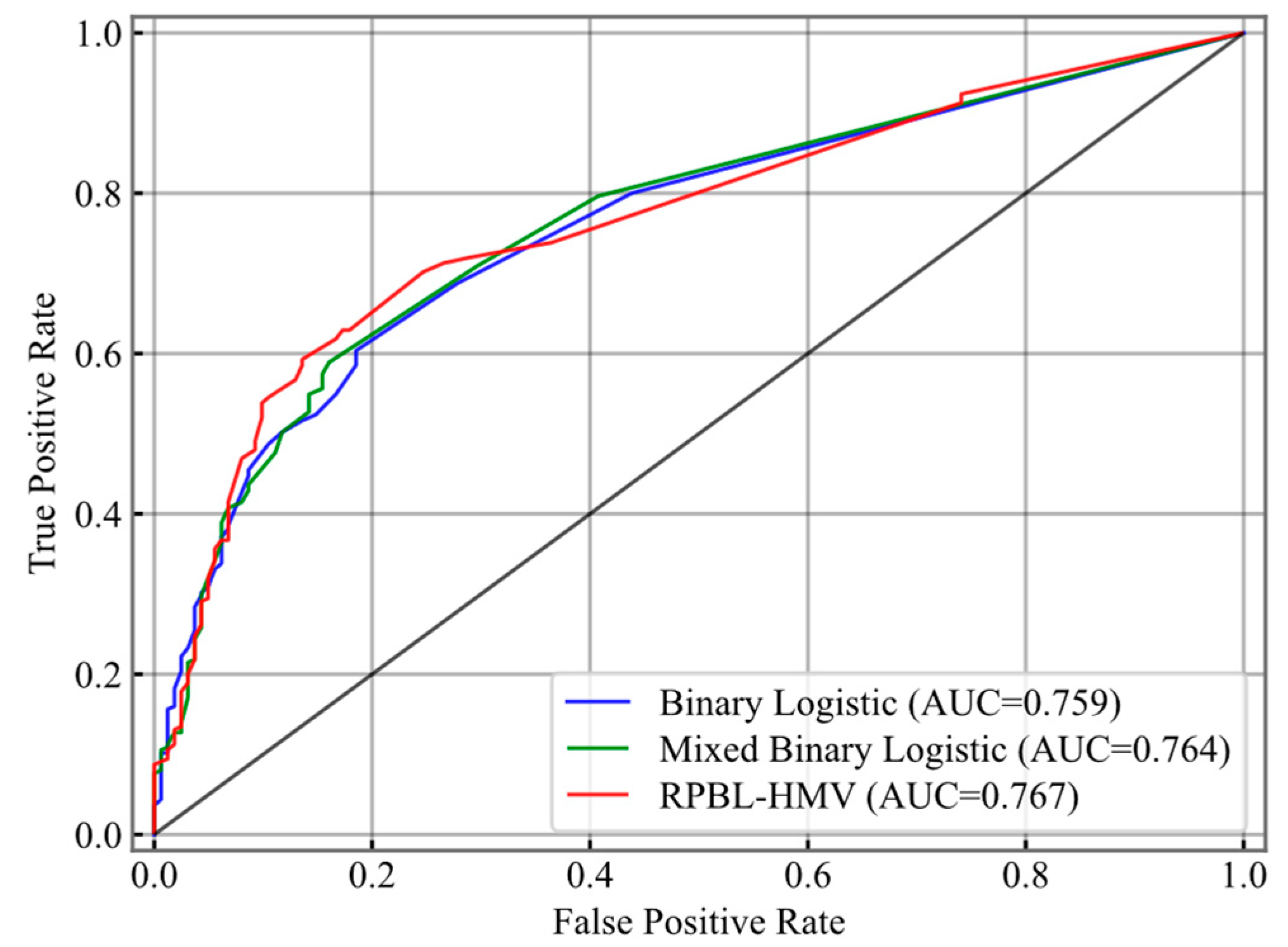

5.3. Comparison of Models

6. Discussions

6.1. Factors with Random Parameters

6.2. Factors with Fixed Parameters

7. Conclusions and Limitations

- The RPBL-HMV model demonstrates significantly better goodness-of-fit than both the binary logistic model and the mixed binary logit model.

- Six factors with fixed parameters are positively associated with the likelihood of high-risk conflicts, including male, courier, running red light, failure to slow down before turning, entering intersections without slowing down, and failing to maintain a safe lateral distance.

- “Failing to maintain a safe lateral distance” is a rarely reported but important factor. When an e-bike travels alongside a motor vehicle, it can easily fall into the driver’s blind spot. Under such conditions, even minor directional deviations by either party can substantially increase conflict risk.

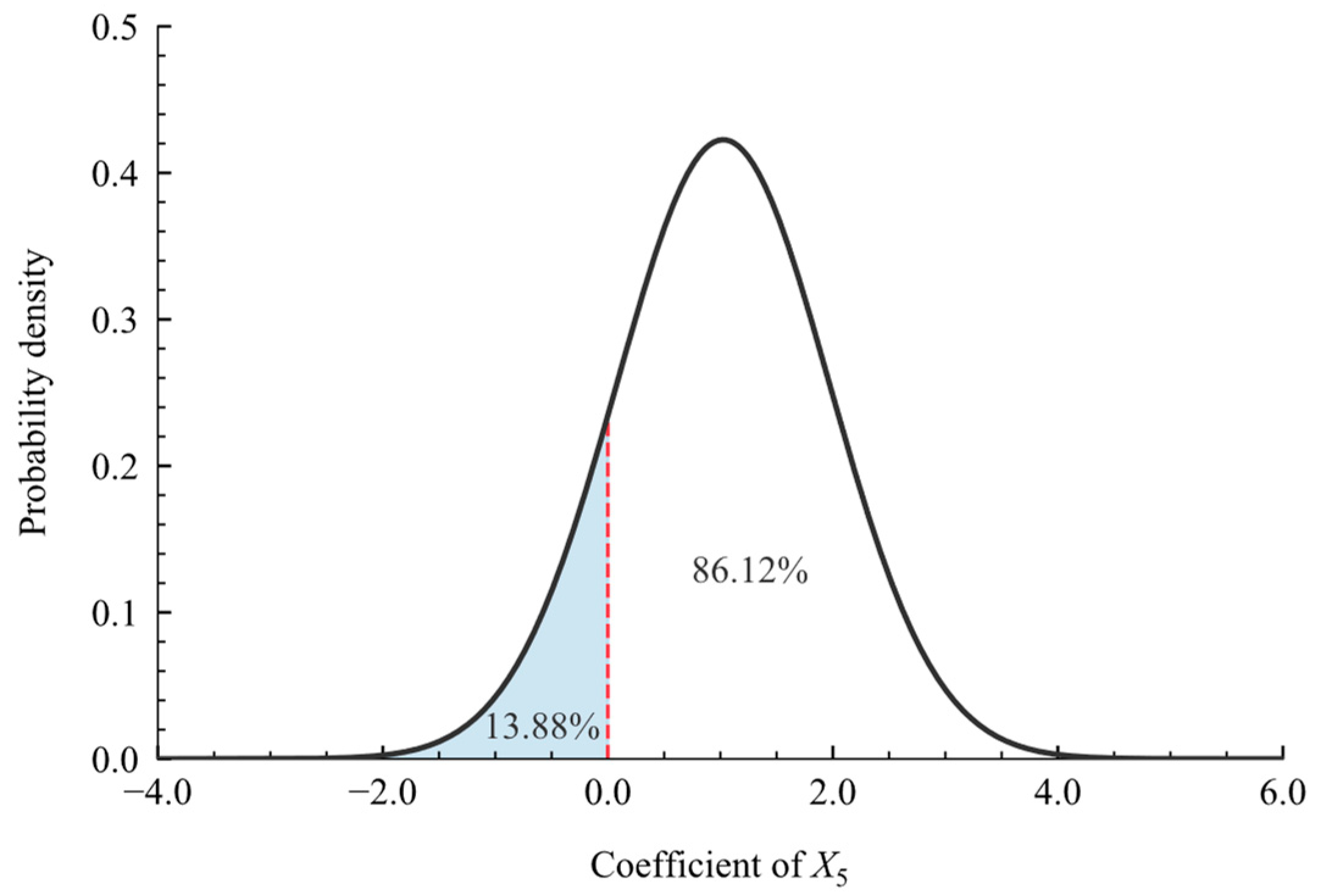

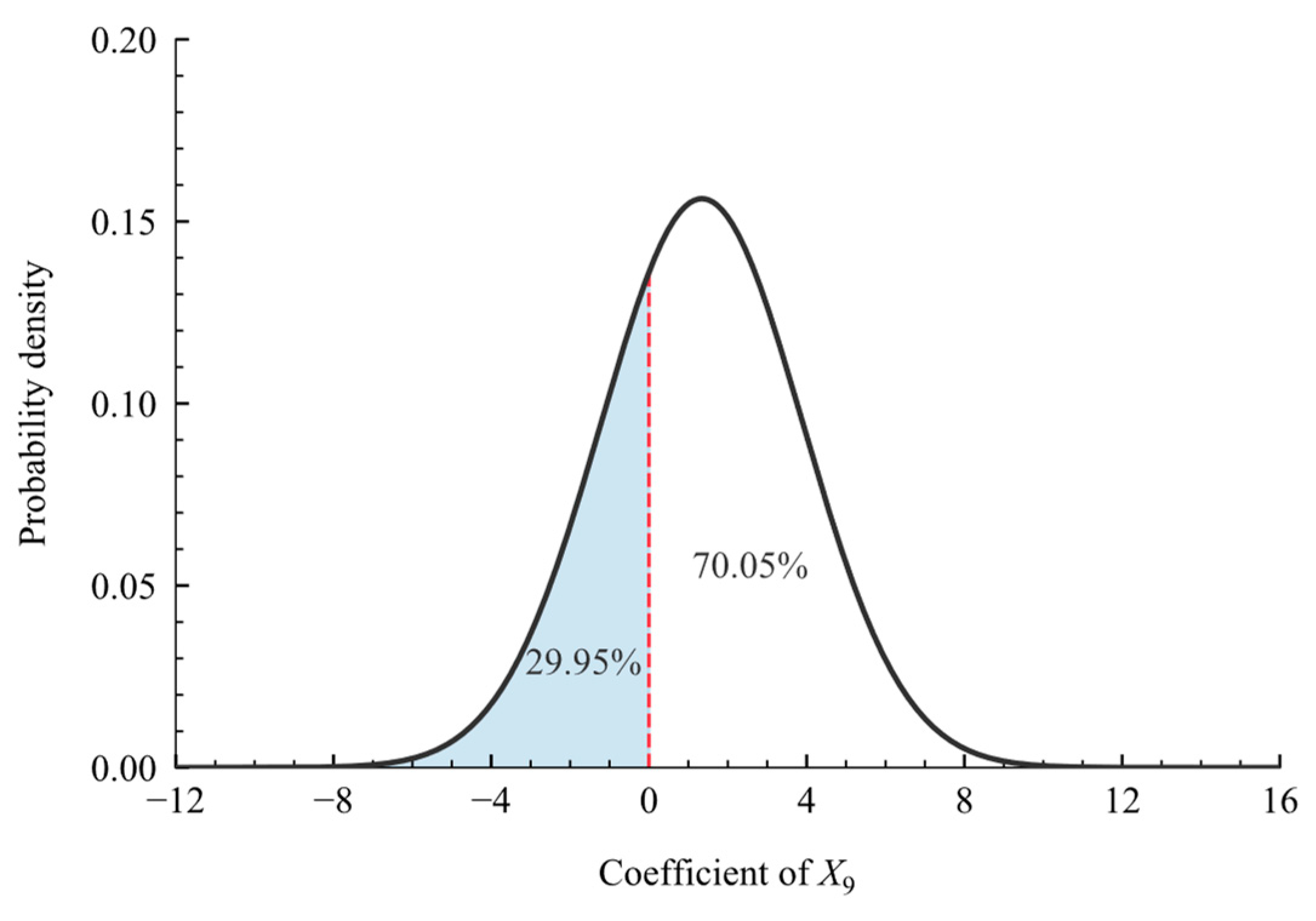

- The factors “occupying motor vehicle lanes” and “e-bike turning without yielding to straight-through motor vehicles” generate random parameters, and their marginal effects indicate a positive influence on the probability of high-risk conflicts.

- “Failure to slow down before turning” decreases the mean of the random parameter for the factor “occupying motor vehicle lane”. This can be attributed to the fact that when e-bikes share the same turning phases as motor vehicles under the condition of occupying motor vehicle lanes, riders who do not decelerate reduce the speed differential between themselves and motor vehicles. This, in turn, lowers the likelihood of high-risk conflicts compared with cases where riders slow down before turning.

- No variables were found to significantly explain variance heterogeneity. This suggests that the impacts of the two factors with random parameters on high-risk conflicts vary among different e-bike riders. However, the degree of dispersion in these impacts remains relatively stable across different scenarios.

- The findings of this study offer important insights into the behavioral mechanisms underlying risky riding among e-bike users. Safety improvement recommendations are proposed from the perspectives of engineering design, traffic management, and behavioral guidance, offering practical implications for regulating unsafe e-bike behaviors and enhancing intersection safety.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Xu, C.; Xia, J.; Qian, Z. Modeling faults among e-bike-related fatal crashes in China. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2017, 18, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Sayed, T. Comparison of traffic conflict indicators for crash estimation using peak over threshold approach. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2019, 2673, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingye Industry Report Library. 2024 Global E-Bike Market Insight Report (Electric Bicycle). Available online: https://www.10100.com/article/8910958 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- China Bicycle Association. China Bicycle Association Official Website. Available online: http://www.china-bicycle.com/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. Ministry of Commerce: National E-Bike Trade-In Exceeds 3 Million Units in 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202504/content_7018613.htm (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Wang, C.; Xu, C.; Xia, J.; Qian, Z. The effects of safety knowledge and psychological factors on self-reported risky driving behaviors including group violations for e-bike riders in China. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 56, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songguo Think Tank. Report on Defensive Driving of E-Bikes in China. Available online: https://finance.people.com.cn/n1/2022/1208/c1004-32583122.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Ju, X. Factors affecting electric bicycle rider injury in accident based on random forest model. J. Transp. Syst. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2021, 21, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Liu, T.; Li, H.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, J. Analysis of causes and patterns of rural road traffic accidents in Northeast China based on PCA-SC. Commun. Sci. Technol. 2022, 45, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitsky, B.; Radomislensky, I.; Goldman, S.; Kaim, A.; Acker, A.; Aviran, N.; Bahouth, H.; Bar, A.; Becker, A.; Braslavsky, A.; et al. Electric bikes and motorized scooters—Popularity and burden of injury. Ten years of national trauma registry experience. J. Transp. Health 2021, 22, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yang, D.; Zhou, J.; Feng, Z.; Yuan, Q. Risk riding behaviors of urban e-bikes: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ma, Q.; Yu, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Lu, G. Injuries and risk factors associated with bicycle and electric bike use in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saf. Sci. 2022, 152, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Dong, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Visualization and bibliometric analysis of e-bike studies: A systematic literature review (1976–2023). Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 122, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Yang, J.; Powis, B.; Zheng, X.; Ozanne-Smith, J.; Bilston, L.; Wu, M. Understanding on-road practices of electric bike riders: An observational study in a developed city of China. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 59, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Sun, Q.; Fei, G.; Li, X.; Stallones, L.; Xiang, H.; Zhang, X. Riding behavior and electric bike traffic crashes: A Chinese case-control study. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2020, 21, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, M.; Stallones, L.; Xiang, H. Road traffic injuries among riders of electric bike/electric moped in southern China. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2018, 19, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, J. Effects of personality traits and sociocognitive determinants on risky riding behaviors among Chinese e-bikers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2019, 20, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzoldt, T.; Schleinitz, K.; Heilmann, S.; Gehlert, T. Traffic conflicts and their contextual factors when riding conventional vs. Electric bicycles. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 46, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayar, R.; Paudel, M.; Yap, F.F.; Xu, H.; Wong, Y.D.; Zhu, F. Impact of attitude, behaviour and opinion of e-scooter and e-bike riders on collision risk in singapore. Travel Behav. Soc. 2025, 38, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, X. Analyzing aggressive cycling behaviors of e-bikers in guangzhou through structural equation models. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2024, 2678, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, W. Adolescent aggressive riding behavior: An application of the theory of planned behavior and the prototype willingness model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; De Angelis, M.; Fraboni, F.; Pietrantoni, L.; Johnson, D.; Shires, J. Journey attributes, e-bike use, and perception of driving behavior of motorists as predictors of bicycle crash involvement and severity. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2020, 2674, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, A.; Haque, M.M.; Bhaskar, A.; Washington, S.; Sayed, T. A systematic mapping review of surrogate safety assessment using traffic conflict techniques. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 153, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinar, D.; Valero-Mora, P.; Van Strijp-Houtenbos, M.; Haworth, N.; Schramm, A.; De Bruyne, G.; Cavallo, V.; Chliaoutakis, J.; Dias, J.; Ferraro, O.E.; et al. Under-reporting bicycle accidents to police in the cost tu1101 international survey: Cross-country comparisons and associated factors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 110, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleinitz, K.; Petzoldt, T.; Kröling, S.; Gehlert, T.; Mach, S. (e-)cyclists running the red light—The influence of bicycle type and infrastructure characteristics on red light violations. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 122, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Ji, Y.; Lv, H.; Ma, X. Analysis of factors influencing delivery e-bikes’ red-light running behavior: A correlated mixed binary logit approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 152, 105977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, F.; Deng, Y. Analysis of traffic conflicts on slow-moving shared paths in Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozza, M.; Bianchi Piccinini, G.F.; Werneke, J. Using naturalistic data to assess e-cyclist behavior. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 41, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, L. An observational study on the risk behaviors of electric bicycle riders performing meal delivery at urban intersections in China. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 79, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Leyva, P.; Dozza, M.; Baldanzini, N. Investigating cycling kinematics and braking maneuvers in the real world: E-bikes make cyclists move faster, brake harder, and experience new conflicts. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 54, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Leyva, P.; Dozza, M.; Baldanzini, N. E-bikers’ braking behavior: Results from a naturalistic cycling study. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2019, 20, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Ma, Y.; Sayed, T.; Guo, Y.; Chen, S.; Fu, Y. Exploring the impact of right-turn safety measures on e-bike-heavy vehicle conflicts at signalized intersections. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 206, 107722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Shen, K.; Li, X.; Ye, Y. Exploring factors affecting the yellow-light running behavior of electric bike riders at urban intersections in China. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 8573232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huan, M.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Peng, Y.; Gao, Z. A hazard-based duration model for analyzing crossing behavior of cyclists and electric bike riders at signalized intersections. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 74, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Liu, P.; Guo, Y.; Xu, C. Understanding factors affecting frequency of traffic conflicts between electric bicycles and motorized vehicles at signalized intersections. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2015, 2514, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Wang, C.; Cheng, W.; Liu, H.; Vitetta, A. Exploring factors associated with cyclist injury severity in vehicle-electric bicycle crashes based on a random parameter logit model. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 5563704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ji, C.; Li, B.; Jiang, P.; Qin, K.; Ni, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhong, R.; Fang, L.; Zhao, M. Riding practices of e-bike riders after the implementation of electric bike management regulations: An observational study in Hangzhou, China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Quddus, M.; Zhou, W.; Shen, M. Influence of familiarity with traffic regulations on delivery riders’ e-bike crashes and helmet use: Two mediator ordered logit models. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 159, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S.; Møller, M. E-bike safety: Individual-level factors and incident characteristics. J. Transp. Health 2016, 3, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyhri, A.; Johansson, O.; Bjørnskau, T. Gender differences in accident risk with e-bikes—Survey data from norway. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 132, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Wu, C. Traffic safety for electric bike riders in China. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2012, 2314, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xie, S.; Ye, X.; Yan, X.; Chen, J.; Li, W. Analyzing e-bikers’ risky riding behaviors, safety attitudes, risk perception, and riding confidence with the structural equation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, J.; Bian, Y.; Zhao, X.; Han, T. Shared e-bike riders’ psychology contribution to self-reported traffic accidents: A structural equation model approach with mediation analysis. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2023, 15, 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, X. Analysis of college students’ phone call behavior while riding e-bikes: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. J. Transp. Health 2023, 31, 101635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, S.W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Morris, A. Analyzing predictive factors influencing helmet-wearing behavior among e-bike riders. Transp. Policy 2025, 171, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Su, F.; Schwebel, D.C. Mobile phone use while cycling among e-bikers in China: Reasoned or social reactive? J. Saf. Res. 2023, 85, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Baig, F.; Lee, J.J. Exploring young individuals’ intentions to use helmets of shared e-bike in China. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 29, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, P. Psychological factors associated with helmet use while riding an electric two-wheeler among older Chinese adults. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2025, 2679, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Yan, X.; Chen, J. Analyzing takeaway e-bikers’ risky riding behaviors and formation mechanism at urban intersections with the structural equation model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Qi, Y.; Shi, J. Description and analysis of aberrant riding behaviors of pedal cyclists, e-bike riders and motorcyclists: Based on a self-report questionnaire. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 107, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Af Wahlberg, A.E. Social desirability effects in driver behavior inventories. J. Saf. Res. 2010, 41, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shao, Y.; Ye, F.; Zhu, T. Injury severity analysis of e-bike riders in China based on the in-vehicle recording video crash data: A random parameter ordered logit model. Int. J. Inj. Contr. Saf. Promot. 2024, 31, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.; Haque, M.M.; Yasmin, S.; Huang, H. Crash injury severity analysis of e-bike riders: A random parameters generalized ordered probit model with heterogeneity in means. Saf. Sci. 2022, 146, 105545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountas, G.; Anastasopoulos, P.C. A random thresholds random parameters hierarchical ordered probit analysis of highway accident injury-severities. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2017, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kou, S.; Song, Y. Identify risk pattern of e-bike riders in China based on machine learning framework. Entropy 2019, 21, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable, 2nd ed.; Publishing House of Electronics Industry: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.; Lv, D.; Zhu, J.; Fang, J. Related risk factors for injury severity of e-bike and bicycle crashes in hefei. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2014, 15, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Ye, X. Understand e-bicyclist safety in China: Crash severity modeling using a generalized ordered logit model. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Lin, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, X. Risk factors for road-traffic injuries associated with e-bike: Case-control and case-crossover study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Sulaj, D.; Hao, W.; Kuang, A. Risk factors affecting crash injury severity for different groups of e-bike riders: A classification tree-based logistic regression model. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 76, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Zhu, T.; Liu, H. Risk prediction and factor analysis of rider’s injury severity in passenger car and e-bike accidents based on interpretable machine learning. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. D J. Automob. Eng. 2024, 238, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J. Evaluation of factors affecting e-bike involved crash and e-bike license plate use in China using a bivariate probit model. J. Adv. Transp. 2017, 2017, 2142659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegman, F.; Zhang, F.; Dijkstra, A. How to make more cycling good for road safety? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 44, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarko, A.P. Surrogate measures of safety. In Safe Mobility: Challenges, Methodology and Solutions; Lord, D., Washington, S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 383–405. [Google Scholar]

- Anarkooli, A.J.; Persaud, B.; Milligan, C.; Penner, J.; Saleem, T. Incorporating speed in a traffic conflict severity index to estimate left turn opposed crashes at signalized intersections. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2021, 2675, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, C.; Laureshyn, A.; De Ceunynck, T. In search of surrogate safety indicators for vulnerable road users: A review of surrogate safety indicators. Transp. Rev. 2018, 38, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleinitz, K.; Petzoldt, T.; Franke-Bartholdt, L.; Krems, J.; Gehlert, T. The german naturalistic cycling study—Comparing cycling speed of riders of different e-bikes and conventional bicycles. Saf. Sci. 2017, 92, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.; Guo, F.; Han, S.; Mollenhauer, M.; Broaddus, A.; Sweeney, T.; Robinson, S.; Novotny, A.; Buehler, R. What factors contribute to e-scooter crashes: A first look using a naturalistic riding approach. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 85, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlakveld, W.; Mons, C.; Kamphuis, K.; Stelling, A.; Twisk, D. Traffic conflicts involving speed-pedelecs (fast electric bicycles): A naturalistic riding study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 158, 106201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yao, L.; Zhang, K. The red-light running behavior of electric bike riders and cyclists at urban intersections in China: An observational study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 49, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Sze, N.N. Red light running behavior of bicyclists in urban area: Effects of bicycle type and bicycle group size. Travel Behav. Soc. 2020, 21, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Kuai, C.; Lv, H.; Li, W.; Campisi, T. Investigating different types of red-light running behaviors among urban e-bike rider mixed groups. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 1977388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Li, H.; Sze, N.N.; Ren, G. The impacts of non-motorized traffic enforcement cameras on red light violations of cyclists at signalized intersections. J. Saf. Res. 2022, 83, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Zhao, J.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, F. Can i trust you? Estimation models for e-bikers stop-go decision before amber light at urban intersection. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 6678996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Oh, C.; Moon, J.; Kim, S. Development of a lane change risk index using vehicle trajectory data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 110, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Qin, X.; Grembek, O.; Chen, Z. Developing a safety heatmap of uncontrolled intersections using both conflict probability and severity. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 113, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, S.; Jonasson, J.M.; Genell, A.; Steineck, G. Bias in Odds Ratios by Logistic Regression Modelling and Sample Size. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureshyn, A.; Svensson, Å.; Hydén, C. Evaluation of traffic safety, based on micro-level behavioural data: Theoretical framework and first implementation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, K.; Sayed, T.; Saunier, N. Methodologies for aggregating indicators of traffic conflict. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2011, 2237, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureshyn, A.; De Ceunynck, T.; Karlsson, C.; Svensson, Å.; Daniels, S. In search of the severity dimension of traffic events: Extended delta-v as a traffic conflict indicator. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 98, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsos, A.; Farah, H.; Laureshyn, A.; Hagenzieker, M. Are collision and crossing course surrogate safety indicators transferable? A probability based approach using extreme value theory. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 143, 105517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, A.D.; Katthe, A.; Sohrabi, A.; Jahangiri, A.; Xie, K. Predicting critical bicycle-vehicle conflicts at signalized intersections. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 8816616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.L.; Shin, B.T.; Cooper, P.J. Analysis of traffic conflicts and collisions. Transp. Res. Rec. 1978, 667, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gettman, D.; Pu, L.; Sayed, T.; Shelby, S.G. Surrogate Safety Assessment Model and Validation: Final Report; FHWA-HRT-08-051; Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation: McLean, VA, USA, 2008. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/39210 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Kraay, J.H.; van der Horst, A.R.A.; Oppe, S. Manual Conflict Observation Technique DOCTOR (Dutch Objective Conflict Technique for Operation and Research); Foundation Road Safety for All: Voorburg, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Sayed, T. From univariate to bivariate extreme value models: Approaches to integrate traffic conflict indicators for crash estimation. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 103, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Qin, X.; Liu, P.; Sayed, M.A. Assessing surrogate safety measures using a safety pilot model deployment dataset. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2018, 2672, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, C.; Laureshyn, A.; Dagostino, C. Validation of surrogate measures of safety with a focus on bicyclist–motor vehicle interactions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 153, 106037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xie, K.; Keyvan-Ekbatani, M. Modeling driver’s evasive behavior during safety-critical lane changes: Two-dimensional time-to-collision and deep reinforcement learning. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2023, 186, 107063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laureshyn, A.; Goede, M.D.; Saunier, N.; Fyhri, A. Cross-comparison of three surrogate safety methods to diagnose cyclist safety problems at intersections in norway. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 105, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ceunynck, T. Defining and Applying Surrogate Safety Measures and Behavioural Indicators Through Site-Based Observations. Ph.D. Thesis, Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tageldin, A.; Sayed, T. Developing evasive action-based indicators for identifying pedestrian conflicts in less organized traffic environments. J. Adv. Transp. 2016, 50, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, S.; Karlaftis, M.; Mannering, F.; Anastasopoulos, P. Statistical and Econometric Methods for Transportation Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pervez, A.; Lee, J.; Huang, H. Exploring factors affecting the injury severity of freeway tunnel crashes: A random parameters approach with heterogeneity in means and variances. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 178, 106835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnood, A.; Mannering, F. Determinants of bicyclist injury severities in bicycle-vehicle crashes: A random parameters approach with heterogeneity in means and variances. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2017, 16, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Se, C.; Champahom, T.; Jomnonkwao, S.; Ratanavaraha, V. Motorcyclist injury severity analysis: A comparison of artificial neural networks and random parameter model with heterogeneity in means and variances. Int. J. Inj. Contr. Saf. Promot. 2022, 29, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Zhao, L.; Tang, W.; Wu, L.; Ren, J. Modeling and analysis of mandatory lane-changing behavior considering heterogeneity in means and variances. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2023, 622, 128825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Huo, X.; Leng, J.; Cheng, Y. Examination of driver injury severity in freeway single-vehicle crashes using a mixed logit model with heterogeneity-in-means. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019, 531, 121760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Gu, R.; Huang, H.; Lee, J.; Zhai, X.; Li, Y. Using vehicular trajectory data to explore risky factors and unobserved heterogeneity during lane-changing. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 151, 105871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Ahmed, A.; Saeed, T.U. Factors affecting motorcyclists’ injury severities: An empirical assessment using random parameters logit model with heterogeneity in means and variances. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 123, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Yang, H.; Huang, J.; Kou, S.; Li, Y.; Theofilatos, A. What factors impact injury severity of vehicle to electric bike crashes in China? Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 168781401770054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, J. Analysis of alternative treatments for left-turn bicycles at tandem intersections. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 126, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Intersection | Signal Type | Number of Lanes | Number of Signal Phases | Cycle Length (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wuhu Rd. & Tongcheng Rd. | Countdown | 6 & 3 | 3 | 151 |

| 2 | Huancheng Rd. & Tongcheng Rd. | Countdown | 2 & 3 | 2 | 66 |

| 3 | Lujiang Rd. & Tongcheng Rd. | Countdown | 2 & 3 | 2 | 70 |

| 4 | Hongxing Rd. & Tongcheng Rd. | Countdown | 2 & 3 | 2 | 72 |

| Category | Variable | Coding Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic information | Gender | Male: 0; female: 1 |

| Courier a | No: 0; Yes: 1 | |

| E-bike type | Bicycle-style: 0; Scooter-style: 1 | |

| Illegal, non-compliant behavior | Riding in the wrong direction | No: 0; Yes: 1 |

| Occupying motor vehicle lanes | ||

| Running red light | ||

| Running yellow light | ||

| Speeding b | ||

| E-bike turning without yielding to straight-through motor vehicles | ||

| Failure to turn left from the right side of the intersection’s center | ||

| Stop beyond the stopping line | ||

| Failure to slow down before turning | ||

| Reckless riding c | ||

| Using a mobile phone while riding | ||

| Not wearing a helmet | ||

| Failure to display an e-bike license plate | ||

| Weaving through parked non-motorized vehicles ahead | ||

| Assembled, modified, or retrofitted e-bike | ||

| Negligent and error-prone behavior | Talking to the passenger or other riders while riding | No: 0; Yes: 1 |

| Entering intersections without slowing down | ||

| Failing to maintain a safe lateral distance d |

| Category | Variable | Coding Value | Count | Percentage | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic information | Gender (X1) | 0 | 132 | 30.21% | 0.30 | 0.460 |

| 1 | 305 | 69.79% | ||||

| Courier (X2) | 0 | 381 | 87.19% | 0.13 | 0.335 | |

| 1 | 56 | 12.81% | ||||

| E-bike type (X3) | 0 | 99 | 22.65% | 0.77 | 0.419 | |

| 1 | 338 | 77.35% | ||||

| Illegal, non-compliant behavior | Riding in the wrong direction (X4) | 0 | 350 | 80.09% | 0.20 | 0.100 |

| 1 | 87 | 19.91% | ||||

| Occupying motor vehicle lane (X5) | 0 | 340 | 77.80% | 0.22 | 0.416 | |

| 1 | 97 | 22.20% | ||||

| Running red light (X6) | 0 | 315 | 72.08% | 0.28 | 0.449 | |

| 1 | 122 | 27.92% | ||||

| Running yellow light (X7) | 0 | 418 | 95.65% | 0.04 | 0.204 | |

| 1 | 19 | 4.35% | ||||

| Speeding (X8) | 0 | 197 | 45.10% | 0.55 | 0.498 | |

| 1 | 240 | 54.90% | ||||

| E-bike turning without yielding to straight-through motor vehicles (X9) | 0 | 349 | 79.86% | 0.20 | 0.401 | |

| 1 | 88 | 20.14% | ||||

| Failure to turn left from the right side of the intersection’s center (X10) | 0 | 349 | 79.86% | 0.20 | 0.401 | |

| 1 | 88 | 20.14% | ||||

| Stop beyond the stopping line (X11) | 0 | 359 | 82.15% | 0.18 | 0.383 | |

| 1 | 78 | 17.85% | ||||

| Failure to slow down before turning (X12) | 0 | 372 | 85.13% | 0.15 | 0.356 | |

| 1 | 65 | 14.87% | ||||

| Reckless riding (X13) | 0 | 422 | 96.57% | 0.03 | 0.182 | |

| 1 | 15 | 3.43% | ||||

| Using a mobile phone while riding (X14) | 0 | 417 | 97.25% | 0.04 | 0.188 | |

| 1 | 12 | 2.75% | ||||

| Not wearing a helmet (X15) | 0 | 125 | 28.60% | 0.71 | 0.452 | |

| 1 | 312 | 71.40% | ||||

| Failure to display an e-bike license plate | 0 | 437 | 100% | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0% | ||||

| Weaving through parked non-motorized vehicles ahead | 0 | 437 | 100% | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0% | ||||

| Assembled, modified, or retrofitted e-bike (X16) | 0 | 302 | 69.11% | 0.31 | 0.463 | |

| 1 | 135 | 30.89% | ||||

| Negligent and error-prone behaviors | Talking to the passenger or other riders while riding (X17) | 0 | 432 | 98.86% | 0.01 | 0.106 |

| 1 | 5 | 1.14% | ||||

| Entering intersections without slowing down (X18) | 0 | 338 | 77.35% | 0.23 | 0.419 | |

| 1 | 99 | 22.65% | ||||

| Failing to maintain a safe lateral distance (X19) | 0 | 349 | 79.86% | 0.20 | 0.401 | |

| 1 | 88 | 20.14% |

| Variable | Coefficient | T-Statistic | p-Value | Marginal Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.418 ** | −2.25 | 0.025 | −0.049 |

| Courier | 0.999 *** | 2.83 | <0.01 | 0.117 |

| Running red light | 0.457 ** | 2.19 | 0.029 | 0.053 |

| Failure to slow down before turning | 1.451 ** | 2.47 | 0.014 | 0.169 |

| Entering intersections without slowing down (X18) | 0.478 ** | 2.18 | 0.029 | 0.056 |

| Failing to maintain a safe lateral distance (X19) | 1.395 *** | 3.84 | <0.01 | 0.163 |

| Random parameters | ||||

| Occupying motor vehicle lane | 0.867 *** | 2.96 | <0.01 | 0.101 |

| Standard deviation | 0.803 ** | 2.35 | 0.019 | - |

| E-bike turning without yielding to straight-through motor vehicles | 1.343 ** | 2.53 | 0.011 | 0.157 |

| Standard deviation | 2.553 *** | 3.72 | <0.01 | - |

| Heterogeneity in the random parameter’s mean | ||||

| Occupying motor vehicle lane: Failure to slow down before turning | −2.629 *** | −3.13 | <0.01 | - |

| Goodness-of-fit measures | ||||

| Number of observations | 437 | |||

| Log-likelihood at constant | −288.128 | |||

| Log-likelihood at convergence | −229.395 | |||

| McFadden | 0.204 | |||

| AIC | 488.8 | |||

| BIC | 550.00 | |||

| Model | Binary Logistic | Mixed Binary Logit | RPBL-HMV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of observations | 437 | 437 | 437 |

| Number of parameters | 7 | 7 | 11 |

| Log-likelihood at constant | −288.128 | −288.128 | −288.128 |

| Log-likelihood at convergence | −241.349 | −237.214 | −229.395 |

| McFadden | 0.162 | 0.177 | 0.204 |

| AIC | 496.7 | 496.4 | 488.8 |

| BIC | 525.3 | 541.3 | 550.00 |

| Likelihood Ratio Test | Binary Logistic vs. RPBL-HMV | Mixed Binary Logit Vs. RPBL-HMV |

|---|---|---|

| Degrees of freedom | 4 | 4 |

| Level of significance | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Critical | 9.488 | 9.488 |

| Computed | 23.91 | 15.64 |

| Indicator | Binary Logistic | Mixed Binary Logit | RPBL-HMV |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1-score | 0.777 | 0.772 | 0.777 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Tao, Z.; Chen, Q.; He, J.; Ruan, X.; Ling, X. Investigating Risky Behaviors and Safety Countermeasures for E-Bike Riders in China: A Traffic Conflict Analysis Approach. Systems 2026, 14, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010037

Chen Y, Tao Z, Chen Q, He J, Ruan X, Ling X. Investigating Risky Behaviors and Safety Countermeasures for E-Bike Riders in China: A Traffic Conflict Analysis Approach. Systems. 2026; 14(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yikai, Zhengbin Tao, Qunsheng Chen, Jie He, Xiaobo Ruan, and Xiang Ling. 2026. "Investigating Risky Behaviors and Safety Countermeasures for E-Bike Riders in China: A Traffic Conflict Analysis Approach" Systems 14, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010037

APA StyleChen, Y., Tao, Z., Chen, Q., He, J., Ruan, X., & Ling, X. (2026). Investigating Risky Behaviors and Safety Countermeasures for E-Bike Riders in China: A Traffic Conflict Analysis Approach. Systems, 14(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010037