1. Introduction

Food security has become an increasingly critical challenge under the pressures of global environmental and socio-economic change. According to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024, global hunger has remained high for three consecutive years. In 2023, about 733 million people, roughly one in every eleven individuals, were undernourished, posing a serious obstacle to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG, Zero Hunger) [

1]. Historically, the vulnerability of the global food system has been repeatedly exposed by crises. In the 1970s, the oil crisis and natural disasters triggered a global food crisis as major exporters such as the United States reduced grain exports, causing severe supply fluctuations [

2]. In the 21st century, global food security remains vulnerable. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted supply chains, pushing nearly 12 percent of the world’s population into severe food insecurity, an increase of 148 million people from 2019 [

3]. In 2022, the Russia-Ukraine conflict further disrupted grain exports, prompting 23 countries to implement export restrictions, including 12 with wheat export bans [

4].

Inter-provincial food flow faces challenges in many countries, and spatial mismatches between food supply and demand exert significant pressure on food security [

5]. First, disruptions in inter-provincial food flows are a widespread phenomenon. Second, the spatial distribution of food production capacity and consumption demand varies considerably across provinces. As a result, structural mismatches have emerged between major producing and consuming regions, with some areas experiencing long-term surpluses while others remain persistently dependent on external supply. Such inefficiencies in inter-provincial flow mechanisms can easily cause localized or regional food crises [

6]. In addition, inadequate logistics infrastructure further constrains the efficiency of food flows. In many developing countries and regions, transportation and storage systems exhibit evident limitations. Long transport distances increase losses, while food waste along supply chains remains severe, undermining the stability and security of food supply [

7].

Despite China’s relatively limited natural resource endowment, the total food production has continued to rise in recent years, helping maintain the overall stability of national food security. However, as the center of gravity of food production continues to shift northward, China increasingly faces pronounced challenges related to regional vulnerability and sustainability [

6,

8]. On the one hand, major food production areas are concentrated in northern regions where the environmental carrying capacity is relatively weak, thereby intensifying pressures on water and soil resources and heightening ecological risks [

8]. On the other hand, the growing frequency of extreme weather events has substantially increased the vulnerability and uncertainty of agricultural production systems [

9]. Facing the complex and evolving environment, inter-provincial food flows face structural imbalances and multiple potential risks, posing new challenges to safeguarding national food security. Strengthening infrastructure development and improving the efficiency of inter-provincial food flow have therefore become urgent priorities. These measures are essential for reinforcing the country’s internal food redistribution mechanisms and enhancing the resilience of the food flow system.

A growing literature has focused on inter-provincial food flows in China. Dalin et al. [

10] provided an early analysis of the role of international and inter-provincial food trade in shaping China’s agricultural water use and food supply. Zhuo et al. [

11] investigated virtual water flows associated with inter-provincial maize and pork trade, while Zhai et al. [

12] further analyzed the flow patterns of inter-provincial grain-related virtual water and their associated environmental impacts. Zuo et al. [

13] estimated the carbon emissions associated with inter-provincial grain transportation in China between 1990 and 2015. In addition, Ji et al. [

14] examined the impact of inter-provincial trade on economic growth using a two-way fixed-effects model, and Wang et al. [

15] compared the comprehensive benefits of virtual water flows in grain trade from resource, economic, and environmental perspectives. More recently, Luo et al. [

16] developed a comprehensive dataset of inter-provincial physical food flows in mainland China covering the period 2000–2022, encompassing 15 key plant-based and animal-based food products. Despite these advances, research explicitly focusing on the resilience of inter-provincial staple food flows in China remains relatively limited.

Resilience assessment methods in existing research primarily include ecological network resilience, statistical indicator methods, and recovery-curve analysis. Ulanowicz et al. [

17] introduced an information theory approach that evaluates overall system resilience by quantifying two core attributes: efficiency and redundancy. Kummu et al. [

18] identified two key principles through which global trade enhances food system resilience: maintaining diversity and managing connectivity. Blessley and Mudambi [

19] employed a statistical indicator approach to systematically assess the stability of food supply chains during the trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic. From a food security perspective, Béné et al. [

20] developed a comprehensive indicator framework for food system resilience and examined strategies for data acquisition. Bruneau et al. [

21] proposed a conceptual framework for assessing community resilience, defining robustness and rapidity as outcome dimensions and redundancy as enabling capacities. They introduced recovery-curve analysis as a unified quantitative tool applicable to a wide range of socio-ecological systems. Building on the Pressure-State-Response framework, Wu et al. [

22] incorporated recovery-curve analysis to identify critical thresholds in land use change and developed a resilience assessment model that captures the nonlinear effects of multiple driving factors.

Ecological network resilience, as a key approach for assessing a system’s capacity to withstand external shocks, has made substantial progress in both theoretical foundation and empirical application. Rooted in Holling’s seminal concept of ecological resilience, this approach emphasizes a system’s ability to preserve its structure and function in the face of disturbances [

23]. Tendall et al. [

24] were the first to introduce the notion of food system resilience, defining it as the capacity of food systems and their multi-level components to ensure the sufficient, appropriate and accessible of food for all people. In China, ecological network resilience has also continued to deepen, with research gradually shifting from qualitative assessments to multi-indicator quantitative evaluation. Zeng et al. [

25] developed a coupled model that integrates a physical network with an information and decision risk network, enabling the assessment of system robustness and resilience dynamics under various failure scenarios. Drawing on the concept of ecological security patterns, Yang et al. [

26] constructed a multi-factor evaluation framework and developed an ecological network for the Loess Plateau using a gravity-model approach. Through network robustness simulations across multiple scenarios, they examined resilience evolution processes and identified the influence intensity and spatial reach of core nodes.

This paper develops a resilience assessment framework for China’s inter-provincial staple food flow network (CISFN) and identifies its resilience dynamics and key determinants. First, a cost-minimizing mathematical programming model is employed to derive the flow relationships of various staples among provinces and municipalities (hereafter collectively referred to as “provinces”). Second, the CISFN is constructed for the period 1998–2022, and its resilience evolution is examined using complex network analysis combined with ecological network resilience theory. Third, key drivers of resilience are identified through econometric approaches, and the relative contributions of major components to resilience changes are quantified. The proposed model provides a rigorous quantitative framework for analyzing and evaluating the resilience of different staples within China’s inter-provincial food flow system under external shocks. It also plays an important foundation for understanding the regional characteristics and spatial heterogeneity of food system resilience in China.

Based on the above analysis, the main novelty and contribution of this paper can be summarized as follows. (1) Incorporation of international import in staple-specific flow estimation. Due to the lack of publicly available inter-provincial food flow data in China, this study employs a mathematical programming approach to estimate provincial flows. During this process, imports and exports of each staple are incorporated, ensuring more accurate and realistic flow estimations. (2) Network-based assessment of CISFN resilience. This study evaluates the resilience of the CISFN from the systemic perspective. By adopting a network-oriented resilience framework, it provides a comprehensive and systematic understanding of inter-provincial food flow, thereby filling a research gap in resilience assessment within China’s domestic food flow system. (3) Identification and quantification of resilience determinants across staples. The study empirically identifies the key driving factors of CISFN resilience and reveals heterogeneity across staples. Using econometric techniques, it further quantifies the relative contributions of these determinants, offering deeper insights into the resilience mechanisms of various staples.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the study area and data sources, and describes the current status of staple food production and consumption across Chinese provinces.

Section 3 presents the materials and research methods.

Section 4 reports the main results, including the evolution of network structure and resilience, as well as the identification of key driving factors.

Section 5 discusses the findings and provides policy recommendations. Finally, the conclusions of the study are summarized in

Section 6.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Construction of the CISFN

This section describes the construction method of the CISFN. Due to the limited availability of inter-provincial flow data for different staples, such information is often not directly accessible. Consequently, inter-provincial food flow patterns are commonly inferred through mathematical programming models based on provincial production and consumption data [

10]. The core idea is to balance supply and demand across provinces and, by incorporating factors such as transportation costs and spatial distance, to reasonably estimate inter-provincial food transfer volumes.

Considering that transportation cost is a primary factor influencing inter-provincial staple food flows [

12,

30], this study sets the minimization of total transportation costs between provinces as the objective function [

11,

15]. Based on provincial-level production and consumption data, the mathematical programming model for inter-provincial staple flow is formulated as follows:

Here, denotes a surplus province, represents the staple type, and indicates the number of surplus provinces for staple in year . refers to a deficit province, and represents the number of deficit provinces for staple in year . denotes the flow volume of staple from surplus province to deficit province in year , while represents the basic transportation cost per unit volume (yuan/ton). denotes the logistical friction coefficient induced by infrastructure conditions, capacity constraints, and transportation time, indicating that higher effective demand is required to meet a given level of need. indicates the total surplus of surplus province for staple in year , and denotes the total deficit of deficit province for the same year.

Furthermore, this study assumes that inter-provincial staple flows occur through provincial capital cities, and the minimum unit transportation cost between these capitals is adopted as the transport cost [

11,

12]. Consequently, the inter-provincial flow results represent an optimal, cost-minimizing outcome rather than an empirically observed logistics system. The choice to model flows between provincial capitals is because this abstraction reflects a theoretical network rather than the full complexity of real logistics [

10]. Provincial capitals serve as representative provincial hubs due to their administrative and logistical centrality, as well as the availability of consistent province-level data [

12]. This simplified optimal network enables us to focus on the structural characteristics and resilience patterns of the CISFN. The provinces and their corresponding capital cities involved in inter-provincial staple flows are listed in

Table A1. The minimum unit transportation costs between provinces are derived from Gao et al. [

31], providing the fundamental data support for constructing the CISFN in subsequent analyses.

Finally, by using China’s 31 provinces as nodes and the inter-provincial staple food flows as edges, the CISFNs can be constructed as follows:

where

refers to the CISFN of staple

in year

,

denotes the set of provinces participating in the flows of staple

in year

, and

represents the set of directed flows of staple

in the same year. In the CISFN, the total number of nodes participating in inter-provincial staple flows is denoted by

, and the total number of edges by

.

Accordingly, the adjacency matrix of staple in year is defined as , where the element equals 1 if there exists a directed flow from province to province in year , and 0 otherwise. Since the flows are weighted, a directed weighted matrix is further defined, where the element in Equation (1) represents the actual flow (in 104 tons) of staple from province to in year .

To examine the robustness of inter-provincial flow patterns under varying logistical conditions, we construct four transportation friction scenarios representing progressively increasing levels of network disruption (

Table 1). For each scenario, the optimization model is solved independently, yielding a set of friction-adjusted flow matrices that allow systematic comparison of flow reallocation and route deviations across assumptions. Unless otherwise noted, all main results presented in this paper are based on the baseline scenario, while the alternative scenarios are used to assess the stability and sensitivity of the inferred flow patterns.

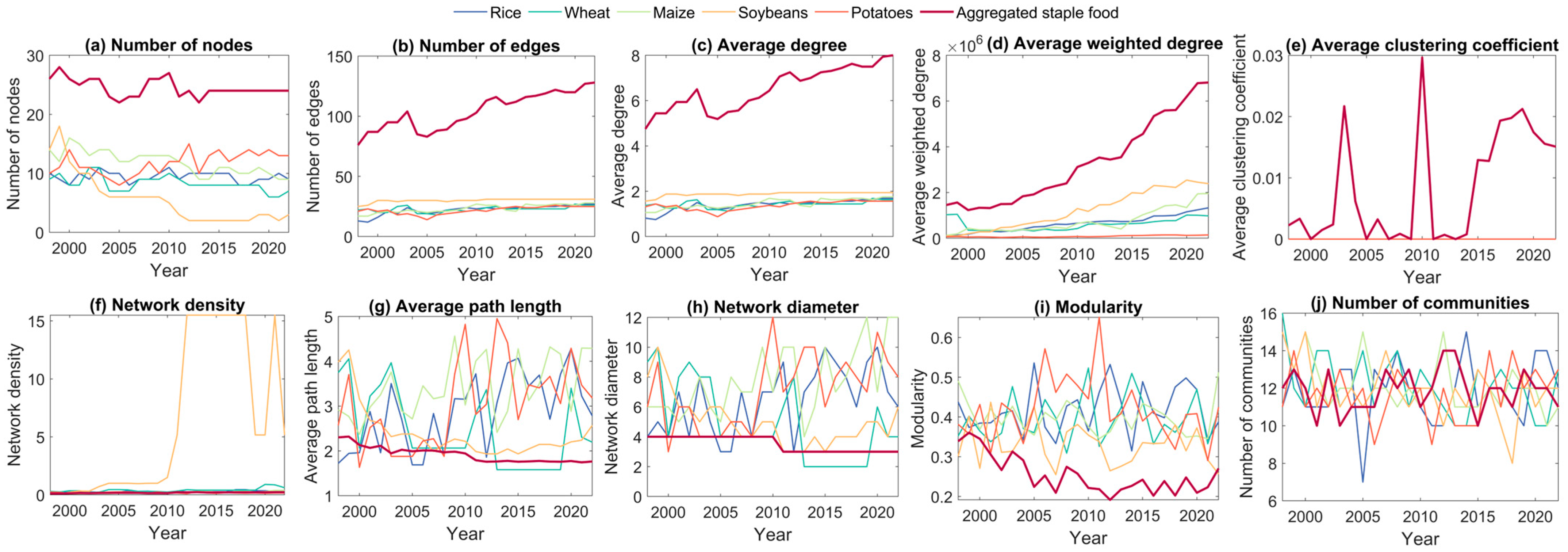

3.2. Topological Structure of CISFNs

This section focuses on identifying and quantifying the internal structural determinants of the CISFNs. Ten fundamental topological indicators are employed to systematically characterize the network structure across three dimensions: node, edge, and overall network levels [

32]. These indicators provide a comprehensive framework for examining the relationship between network topology and system resilience.

3.2.1. Degree and Weighted Degree

The in-degree

and out-degree

of province

in year

represent the number of provinces connected to it as inflow and outflow partners for staple

, respectively. The specific formulas are:

The total degree

of node

in year

is defined as the sum of its in-degree and out-degree, reflecting the diversity of its flow partners [

33]. The average degree

of CISFNs in year

represents the average number of flow partners across all provinces and is calculated as:

where

denotes the number of provinces participating in the inter-provincial flow of staple

in year

.

The inflow strength

of CISFNs represents the total inflow volume of province

in year

, while the outflow strength

denotes its total outflow. They are given by:

where

and

denote the quantity of staple

flowing from province

to

and from

to

in year

respectively. The total strength

of node

in year

is defined as the sum of its inflow and outflow strengths, representing the total volume of staple flow passing through node

[

34], as shown in

Figure 4.

Furthermore, the average weighted degree

represents the mean flow volume per province in CISFNs, calculated as:

3.2.2. Clustering Coefficient and Network Density

The clustering coefficient measures whether provinces participating in inter-provincial food flows tend to form groups or communities within the network, reflecting the local interconnectivity among their neighboring nodes [

35]. For a given province

in year

, the clustering coefficient

is defined as the degree of interconnection among its flow partners, represented by the actual number of links

between them [

32]. The mathematical expression is as follows:

where

denotes the actual number of links among all flow partners of province

, and

and

represent its in-degree and out-degree, respectively.

The average clustering coefficient

is defined as the mean of all provinces’ clustering coefficients, serving as an important indicator of the network’s overall cohesiveness [

36]. A higher average clustering coefficient generally indicates that provinces in the CISFN tend to form more tightly connected groups or communities, exhibiting stronger internal connectivity. It is calculated as:

The network density represents the degree of interconnectedness among provinces participating in the CISFN [

37]. It is defined as the ratio of the actual number of links to the maximum possible number of links. For the CISFN of staple

in year

, the network density is calculated as:

where

denotes the actual number of links in the CISFN of staple

in year

, reflecting the diversity of flow paths. The value of network density ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates the absence of any connections in the network, and 1 indicates a fully connected system.

3.2.3. Average Path Length and Network Diameter

In the CISFN, the path length measures the degree of separation between provinces and serves as an important indicator of the network’s overall structural characteristics [

35]. For a given year

, the path length between provinces

and

is defined as the minimum number of links required to connect them, i.e., their shortest distance.

The average path length of the CISFN represents the mean distance between any two provinces and is calculated as follows:

where

denotes the shortest path length between provinces

and

.

The network diameter describes the longest of all shortest paths between any two provinces in the CISFN [

38] and is defined as:

Both the average path length and network diameter characterize the overall connectivity of the network and help identify provinces that play critical intermediary roles within the CISFN. Generally, shorter average path lengths and diameters indicate a more efficient flow system, reflecting stronger adaptability and resilience in response to external shocks.

3.2.4. Community Structure and Modularity

Exploring the relationship between community structure and resilience in the CISFN is of great importance. When the network is exposed to external shocks, its community structure can significantly influence the propagation path, scope, and speed of the disturbance, thereby directly affecting the overall resilience [

39]. Networks characterized by node heterogeneity and incomplete connectivity often exhibit modular structures that naturally form communities [

40]. Therefore, both the quality and quantity of community partitions are closely related to the resilience level of the CISFN.

In the CISFN, a community is defined as a group of provinces that are closely interconnected through staple-flow relationships. To identify community structures, this study employs the fast modularity optimization algorithm proposed by Blondel et al. [

41]. Modularity serves as a key indicator for evaluating the quality of community divisions: the higher the modularity, the clearer and more distinct the community structure. Following Newman and Girvan [

42], the modularity of the CISFN is defined as:

where

denotes the community to which province

belongs in year

, and the indicator function

equals 1 if

and 0 otherwise. The value of

ranges from –1 to 1; generally, a modularity value between 0.3 and 0.7 indicates a reasonable community partition.

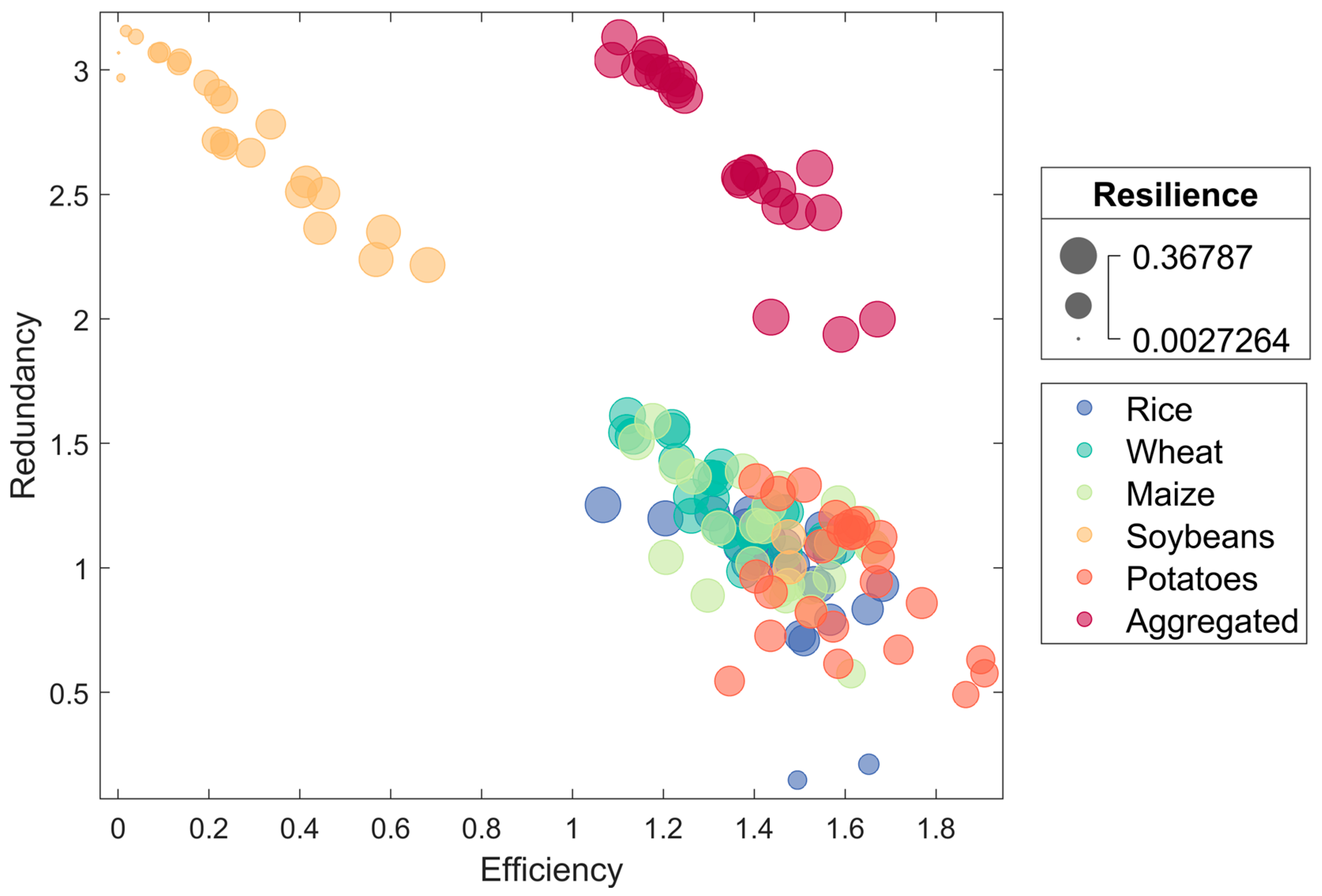

3.3. Resilience Quantification of the CISFN

This section introduces the quantitative framework used to evaluate the resilience of CISFN. Building on Holling’s seminal concept of ecological resilience, the approach emphasizes a system’s capacity to maintain its structure and function in the face of disturbances [

23]. The resilience index used in this study is based on complex network analysis and the ecological network resilience theory proposed by Ulanowicz et al. [

17]. This method is primarily used to reveal and compare system structure and functionality, and it has been widely applied in research on food systems [

38,

43].

In this study, resilience is defined as the system’s capacity to resist, adapt to, and recover from external shocks, with its optimal state characterized by a balanced relationship between efficiency and redundancy [

17,

44]. The resilience indicator is derived from complex network analysis and ecological network resilience theory, and its theoretical foundations lie in thermodynamics, information theory, and ecosystem ecology [

45,

46]. For a detailed explanation of the theoretical basis, please refer to

Appendix C.

The efficiency of the CISFN reflects its ability to facilitate the concentration of staple flows [

43]. Generally, more direct flow paths correspond to higher network efficiency. For instance, provinces may pursue preferential interactions in inter-provincial flows, which can enhance overall productivity but potentially reduce the diversity of flow partners and staple flow paths [

43]. This outcome aligns with the development of an integrated national market and modern logistics infrastructure. Within the CISFN, efficiency is primarily determined by the concentration of flow paths (CD) and their mutual interdependence (PMI). For staple

in year

, efficiency is defined as:

where

Here, denotes the flow volume of staple from province to in year ; is the total flow volume of staple ; and and represent the inflow and outflow of province and , respectively.

Specifically,

represents the proportion of flow from province

to

relative to the total volume, while

measures the degree of dependence between the two provinces

and

, a higher value implies a stronger bilateral connection [

47]. The total flow volume

is defined as:

The redundancy of the CISFN reflects the diversity of flow paths, playing a critical role in mitigating the effects of external disturbances. Redundancy also functions as a strategic buffer embedded within China’s multi-level reserve system [

47]. In inter-provincial staple food flows, the ability to choose among multiple supply and demand partners is fundamental to market flexibility and enhances the system’s capacity to adapt to changing conditions. Similarly to efficiency, redundancy is jointly determined by concentration (CD) and mutual independence (PMR). For staple

in year

, the redundancy can be expressed as:

where

The mutual independence forms a matrix that measures the degree of freedom between provinces and . A higher PMR value indicates a greater number of potential alternative flow paths between the two provinces.

The resilience of the CISFN ultimately arises from the balance between its efficiency and redundancy [

33,

43]. For staple

in year

, the network resilience is defined as:

where

represents the system’s order parameter:

This resilience metric captures the optimal trade-off between efficiency and redundancy, providing deeper insights into the stability and adaptability of the CISFN under external shocks such as global climate change and geopolitical tensions.

Figure 5 presents a numerical example illustrating the relationship among efficiency, redundancy, and resilience. As shown, resilience achieves its maximum value. We can find that the resilience achieves its maximum value (

) when the order parameter reaches its optimal value (

) [

33,

43]. Both excessive efficiency and excessive redundancy could weaken resilience, confirming that resilience emerges from an optimal balance between the two.

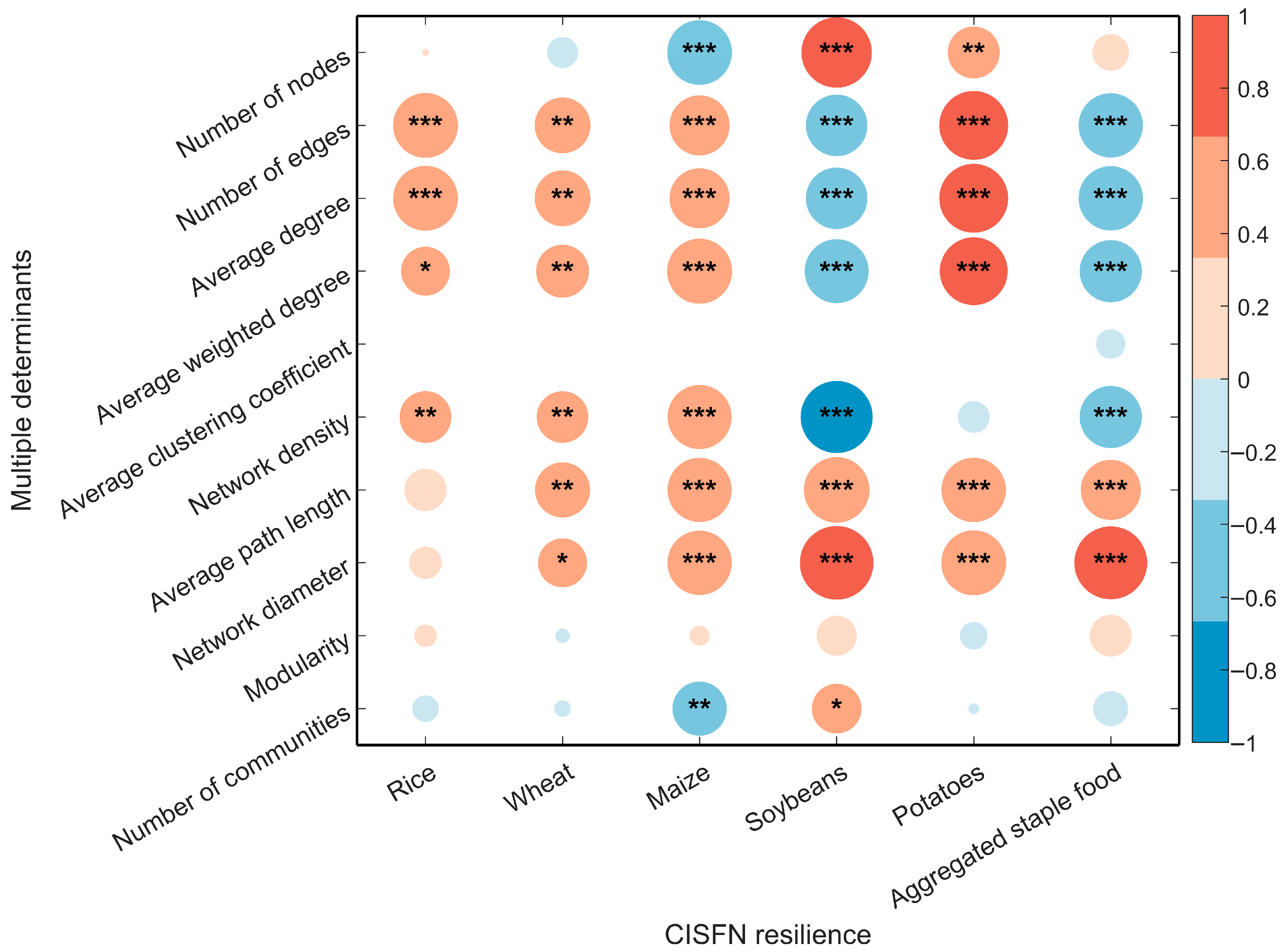

3.4. Determinant Identification of the CISFN

To explore the complex mechanisms shaping the resilience of CISFN, this section employs multiple statistical methods, including the Pearson correlation coefficient and multivariate regression analysis. These methods comprehensively evaluate how various structural and systemic drivers influence network resilience.

The Pearson correlation coefficient is used to assess the strength and direction of the linear association between resilience and its potential drivers [

38], while multivariate regression quantifies their independent effects after accounting for interactions among variables [

48]. However, due to the substantial multicollinearity among network topological indicators, this study first applies a multiple stepwise regression model to identify a parsimonious set of explanatory variables, followed by diagnostic testing using variance inflation factors (VIFs). Finally, a fixed-effects model is employed to evaluate the robustness of the stepwise regression results.

By integrating multiple potential determinants of CISFN resilience, the following multiple linear regression model is constructed:

where

and

denote the staple type and year, respectively. The dependent variable is the resilience of the CISFN, and the 10 explanatory variables include: number of nodes (

n), number of edges (

e), average degree (

), average weighted degree (

), average clustering coefficient (

), network density (Δ), average path length (

L), and network diameter (

D), modularity (

Q), and number of communities (

NOC). Here,

denotes the intercept and

the random error term.

To avoid scale effects, improve numerical stability, and ensure comparability of coefficients across variables, all independent variables were standardized using min-max normalization prior to the multiple regression analysis [

49]. This normalization step helps reduce the influence of heterogeneous units of measurement, enhances model convergence, and allows the fixed-effects estimation to better capture the underlying relationships among the variables.

Beyond network topology, identifying the fundamental components of network resilience is crucial for effective analysis and policy formulation in the context of inter-provincial food security. To this end, the Structural Decomposition Analysis (SDA) approach is adopted to quantify how efficiency and redundancy contribute to temporal changes in resilience from 1998 to 2022 [

50]. SDA also facilitates the evaluation of how inter-provincial food flow dynamics shape resilience patterns over time.

The contributions of efficiency and redundancy to changes in CISFN resilience are defined as:

where

and

denote the respective contributions of changes in efficiency and redundancy to the variation in resilience between years

t to

t′.

Similarly, the cumulative contributions of all inflow and outflow variations to changes in network resilience are expressed as:

A detailed derivation of Equations (21) and (22) is provided in

Appendix B.

5. Discussion

This section provides an in-depth discussion of the results. First, it examines the cumulative contributions of efficiency and redundancy to changes in resilience, focusing on these two core components. It then analyzes each province contributes to overall resilience change, from the perspectives of inflow, outflow, and total flow. Based on these findings, corresponding policy implications are proposed. Finally, the limitations of this study and potential directions for future research are discussed.

5.1. Contributions of Efficiency and Redundancy to Resilience Changes

Redundancy and efficiency form the two core components of the CISFN resilience. The analysis of resilience evolution focuses on the dynamic of overall resilience, with particular attention to the trade-off between these two fundamental attributes.

Figure 14 illustrates the cumulative contributions of efficiency and redundancy to changes in the CISFN resilience from 1998 to 2022, with their sum equal to one. Overall, the results reveal distinct crop-specific resilience mechanisms that reflect not only network structure but also the political-economic context of China’s food system. Rice resilience is predominantly efficiency driven, wheat and potatoes exhibit higher sensitivity to external shocks, maize displays a relatively balanced contribution from efficiency and redundancy, soybeans show persistent structural vulnerability, and the aggregated staple food still exhibits room for improvement. This result is broadly in line with Wu et al.’s findings on resilience-driven heterogeneity in spatial resilience in the Ili River Valley, China [

22]. Specifically, rice resilience is consistent with China’s long-standing policy emphasis on rice self-sufficiency and stable domestic circulation, supported by strong state coordination in production and interregional distribution. Wheat reflects the combined effects of international market volatility, adjustments in domestic supply-side policies, and extreme climate events, all of which interact with policy-driven stabilization mechanisms such as reserve adjustments and cross-regional reallocations, which is consistent with Béné et al.’s results [

20]. Maize reflects the coordinated development of maize production regions and relatively diversified flow paths under national food security strategies. In contrast, soybeans resilience highlights the political-economic vulnerability associated with China’s heavy reliance on imports and the concentration of soybeans supply chains, which limits adaptive capacity under international market shocks and trade risks. Potatoes resilience fluctuates substantially, with efficiency often exceeding redundancy, suggesting that their resilience relies more heavily on redundant paths to mitigate external shocks, in line with findings on the network resilience of phosphorus cycling in China [

43]. For the aggregated staple food, resilience changes are relatively moderate, with the contributions of efficiency and redundancy remaining largely stable.

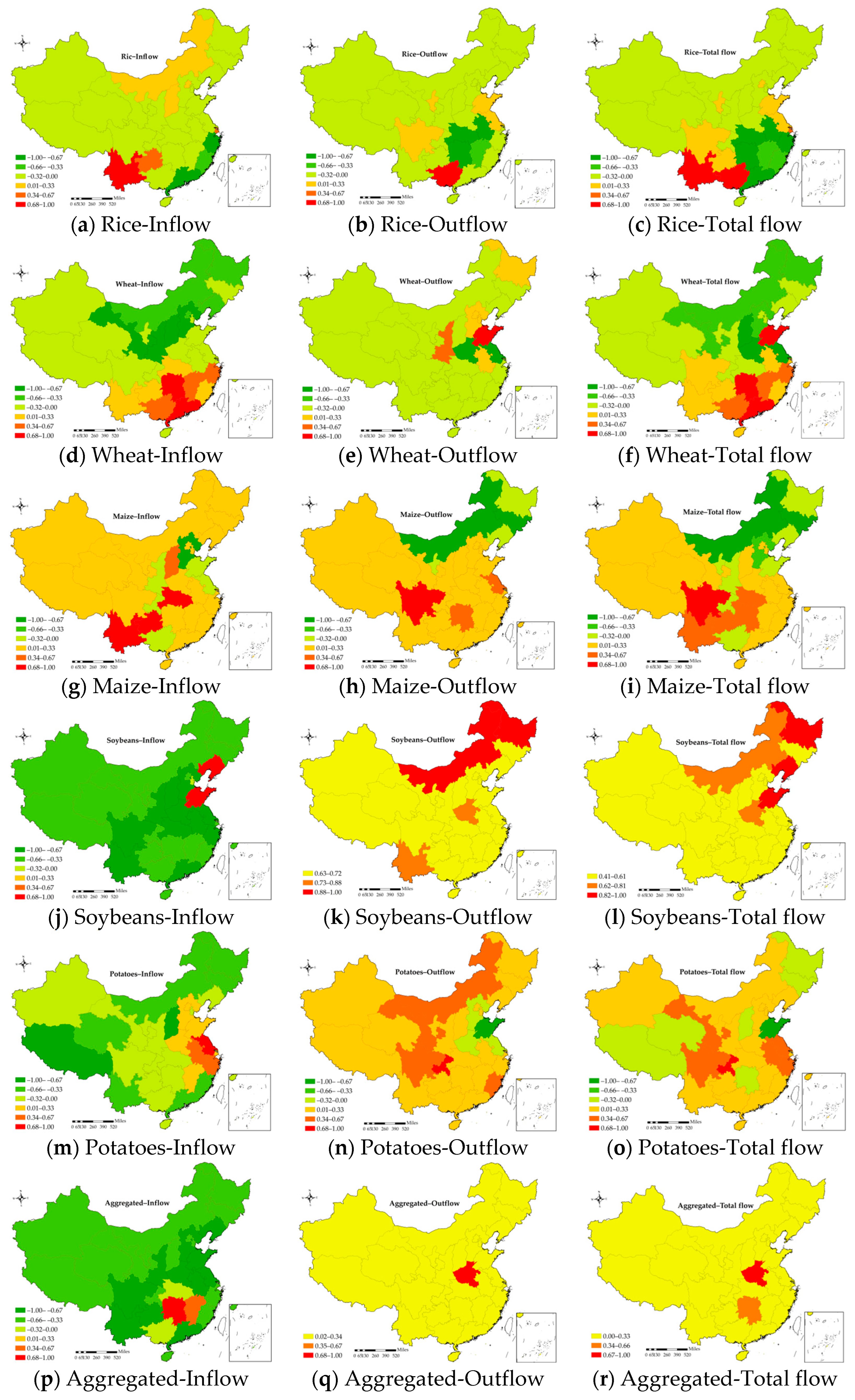

5.2. Contributions of Provinces to Resilience Changes

Figure 15 systematically analyzes provincial contributions to resilience changes in the CISFN from the perspectives of inflow, outflow, and total flow. The results reveal pronounced spatial heterogeneity that reflects not only logistical conditions but also the long-standing governance structure of China’s food system. Specifically: (1) Inflow contributions: Southeastern coastal provinces exhibit substantial positive inflow contributions. Beyond demographic and economic drivers, this pattern is closely linked to China’s food security governance, under which major consumption regions are prioritized for stable supply through coordinated inter-provincial transfers and reserve mechanisms. By contrast, several center provinces exhibit negative inflow contributions, likely due to unstable inflow paths or stronger dependence on external supply, both of which can undermine resilience. This finding corroborates evidence from the global phosphorus trade network, where reliance on external inflows has been shown to weaken systemic resilience [

33]. (2) Outflow contributions: Positive outflow contributions are concentrated in major production regions. These provinces have long been particular as grain-producing bases under national food security policies and are closely integrated into state-coordinated storage and redistribution systems [

56]. (3) Total flow contributions: By combining inflow and outflow effects, total flow contributions highlight provinces that function as key redistribution and balancing hubs. Provinces such as Henan, Shandong, and Heilongjiang emerge as central nodes for supply-demand balancing [

38], reflecting not only their geographic and production advantages but also their institutional roles in cross-regional grain allocation. Their substantial total flow contributions enhance the structural stability and regulatory capacity of the inter-provincial food flow system, underscoring the importance of governance-driven coordination in shaping network resilience.

The comparative analysis across staple foods reveals pronounced regional patterns and spatial heterogeneity. Combined with

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, several key findings emerge: (1) Rice exhibits strong positive contributions in the southeastern coastal and southern regions. Inflows are concentrated in Guangdong and Zhejiang, while outflows mainly originate from Hunan and Jiangxi, forming the classic “north-to-south” flow pattern. (2) Wheat shows contributions concentrated in central provinces. Henan and Shandong function both as major outflow regions and as critical hubs of total flows, underscoring their central role in national wheat redistribution. (3) Maize displays a more dispersed spatial structure: inflows cluster in the southwest, whereas outflows are dominated by northern provinces such as Inner Mongolia and Jilin, reflecting a broadly connected and highly interlinked flow network. (4) Soybeans rely heavily on inflows. These are concentrated in coastal provinces such as Shandong and Jiangsu, while outflows stem primarily from the northeastern production base, forming a hybrid “import and domestic redistribution” pattern. (5) Potatoes exhibit strong regional dependence. Outflows mainly come from southwestern provinces, whereas inflows are concentrated in southeastern coastal areas such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang, indicating geographically constrained and highly concentrated flow paths. (6) For the aggregated staple food network, total flow contributions are generally positive. Provinces such as Henan, Shandong, and Heilongjiang stand out as essential national hubs, highlighting their indispensable roles in sustaining the resilience of the CISFN.

5.3. Model Validation and Sensitivity Analysis

This subsection presents the validation, sensitivity analysis, and uncertainty assessment of the proposed modeling framework. Model robustness is first examined by constructing alternative inter-provincial staple food flow scenarios and conducting quantitative comparisons with existing studies. We then perform a sensitivity analysis of the resilience model under shock perturbations, followed by a discussion of the main sources of uncertainty and their potential implications for the results.

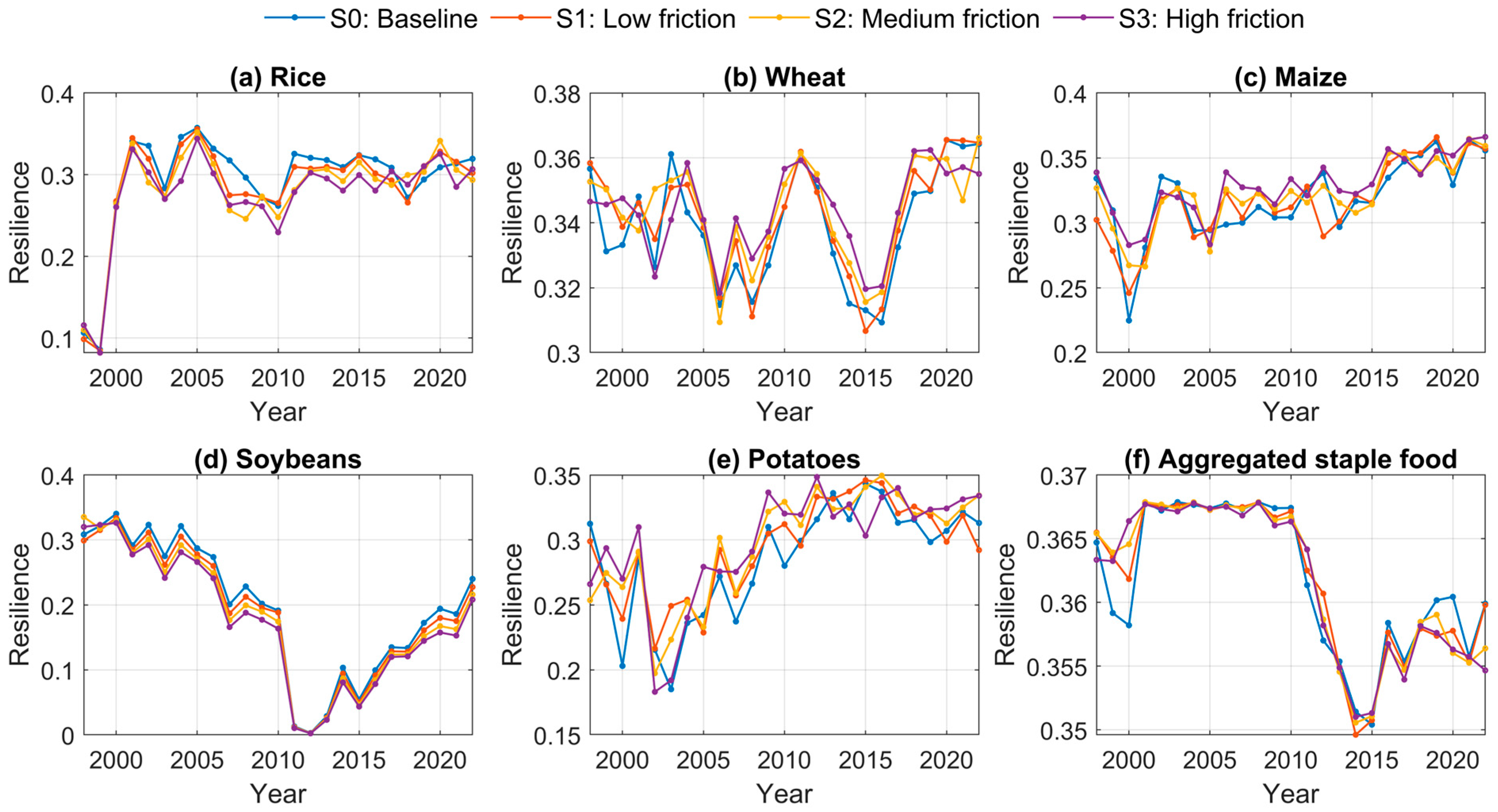

Figure 16 indicates that transportation frictions can indeed reduce network resilience, as reflected by the generally lower resilience levels observed under higher-friction scenarios for certain staples, such as soybeans. At the same time, the overall temporal patterns of resilience remain largely consistent across scenarios, suggesting that the impact of logistical frictions is mediated by the underlying structure of the food flow network. Crop-specific differences highlight that resilience responses to friction depend on supply-demand configurations and network connectivity, rather than on transportation conditions alone. In particular, structurally concentrated or import-dependent networks appear more sensitive to increased frictions, whereas diversified systems exhibit greater stability. These findings underscore that logistical frictions and network structure jointly shape resilience dynamics, with neither factor acting in isolation. This also provides additional support for the robustness of the resilience results, as they remain qualitatively similar under alternative friction assumptions, in line with Zeng et al.’s finding that such multi-layered structures substantially increase both system complexity and fragility [

25]. Uncertainty in the estimated food flows arises from data limitations, parameter assumptions regarding transportation costs and logistical frictions, and structural simplifications in the cost-minimization framework. While these factors may affect absolute flow magnitudes, the main conclusions rely on relative patterns and cross-scenario consistency, indicating that the resilience results are robust within reasonable margins of uncertainty.

Table 3 provides a further comparison of inter-regional food flows between this study and previous work. Ben et al. [

57] employed a cost-minimization optimization framework to simulate inter-provincial grain flows in China, using three-year averages (2010–2012) for major grain crops, including cereals, legumes, and tubers. Following a consistent approach, we calculated the average inter-provincial flows of rice, wheat, maize, soybeans, and potatoes over the same period for comparison. Ben et al. reported national-scale grain flow volumes as well as aggregated outflows from key regions, including Northeast China (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning) and the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River (Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai). Accordingly, our comparison focuses on these aggregated regional flows. The results show that the differences between the two studies are generally within 5%, indicating a high degree of consistency in overall flow magnitudes and providing quantitative support for the reasonableness of the inferred flow structures used in our resilience analysis.

Figure 17 presents the sensitivity analysis of the resilience of the inter-provincial aggregated staple food flow network under different disturbance scenarios. Four types of simulated shocks are examined: targeted node removal, random node removal, targeted edge removal, and random edge removal. For each scenario, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 90% of nodes or edges are removed, and the resulting resilience is tracked over the period 1998–2022.

Figure 17a,b show the effects of node removal. Targeted node removal leads to substantially greater reductions in resilience compared with random removal, particularly when 70% or 90% of the most important nodes are eliminated. Under these severe targeted-removal scenarios, the network becomes partially or fully fragmented, causing resilience to decline sharply or even collapse entirely. In contrast, random node removal produces relatively smoother variations in resilience, indicating that the system is less sensitive to unstructured disturbances.

Figure 17c,d display the effects of edge removal. Similarly to node removal, targeted deletion of high-weighted edges significantly decreases network resilience, especially under the 70% and 90% removal levels. Random removal of edges results in milder fluctuations, with resilience decreasing gradually rather than abruptly. Overall, these results demonstrate that the network is considerably more vulnerable to the loss of structurally important nodes and edges than to random disruptions. They also confirm that the resilience metric is sensitive to meaningful structural perturbations while remaining relatively stable under random noise, supporting the robustness and interpretability of the resilience model.

5.4. Policy Recommendations

Based on these findings, several policy recommendations are proposed to enhance CISFN resilience.

Strengthen coordination in inter-provincial staples flow. Although the aggregated staple food network exhibits stronger resilience than individual staple networks, several challenges remain, including relatively low efficiency and imbalanced flow structures. Consistent with resilience studies in food, water, and energy systems, strengthening redundancy through a multi-node and multi-path logistics system [

5,

58], such as dedicated food railway, multimodal transport hubs, and intelligent storage facilities, would enhance network flexibility and promote more efficient internal allocation of staple foods.

Optimize coordinated allocation across multiple staples. The CISFN resilience depends strongly on the diversity and balance of staple structures [

18,

38]. Wheat and maize tend to exhibit high efficiency with relatively low redundancy, whereas soybeans display higher redundancy but lower efficiency under certain conditions. These differences highlight the importance of integrated, multi-crop coordination strategies. Policy measures that jointly consider multiple staple crops and promote optimized flow mechanisms can leverage the complementary strengths of different staples and thereby enhance the overall resilience of interprovincial food flows.

Improve multi-level regulatory mechanisms. Food flows operate across interconnected global, national, and provincial levels, where disruptions can propagate through multiple channels. Similarly to findings in other critical resource systems [

33,

43], governance limited to a single administrative level is insufficient to manage systemic risks. Strengthening multi-level regulatory frameworks and cross-sector coordination among agricultural, transportation, and trade authorities can significantly improve adaptive capacity. Such governance mechanisms are essential for managing uncertainty and maintaining resilience under increasingly complex logistical and environmental conditions.

Beyond the Chinese context, the policy insights derived from this study are applicable to other countries and regions characterized by large spatial scales and heterogeneous production-consumption patterns. The proposed framework provides a transferable tool for evaluating how network structure shapes food system resilience, offering guidance for resilience-oriented agricultural and logistics planning in diverse institutional settings.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations to this study. First, the evolving dynamics of global climate change and international food trade highlight the need to incorporate more detailed international trade information. Second, due to data availability, this study relies on annual data at the provincial scale. A monthly, city-level representation of staple food flows would enable a more precise assessment of resilience characteristics. Third, the estimation of inter-provincial food flows is based on static transportation cost data, which may not fully capture real-world variability.

Accordingly, three directions for future research are proposed. The first is to integrate global food trade with China’s inter-provincial flows and develop a cross-scale food flow network capable of addressing the combined risks arising from both global market volatility and domestic structural imbalances. The second is to extend the historical dataset and conduct continuous analyses of resilience evolution, with particular attention to refining temporal and spatial scales to better capture emerging trends and key drivers of resilience dynamics. Finally, future research would benefit from incorporating dynamic, time-varying transportation cost data to more accurately reflect real-world conditions, or from applying gravity models that incorporate relevant social and economic factors as a complementary comparison.