Integrating Resilience Thinking into Urban Planning: An Evaluation of Urban Policy and Practice in Chengdu, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Evolution of Resilience Thinking

2.2. The Key Attributes of Urban Resilience

2.3. Evaluating Urban Resilience in Planning

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overview of Selected Planning Documents

3.2. Introduction to the Planner Survey

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Resilience Attributes in Chengdu’s Planning Documents

4.1.1. Resilience-Related Strategies in the SEDP

4.1.2. Resilience-Related Strategies in the URP

4.1.3. Resilience-Related Strategies in the LUP

4.2. Evaluation of Resilience Thinking in Planners

4.2.1. Resilience Attributes in Planners

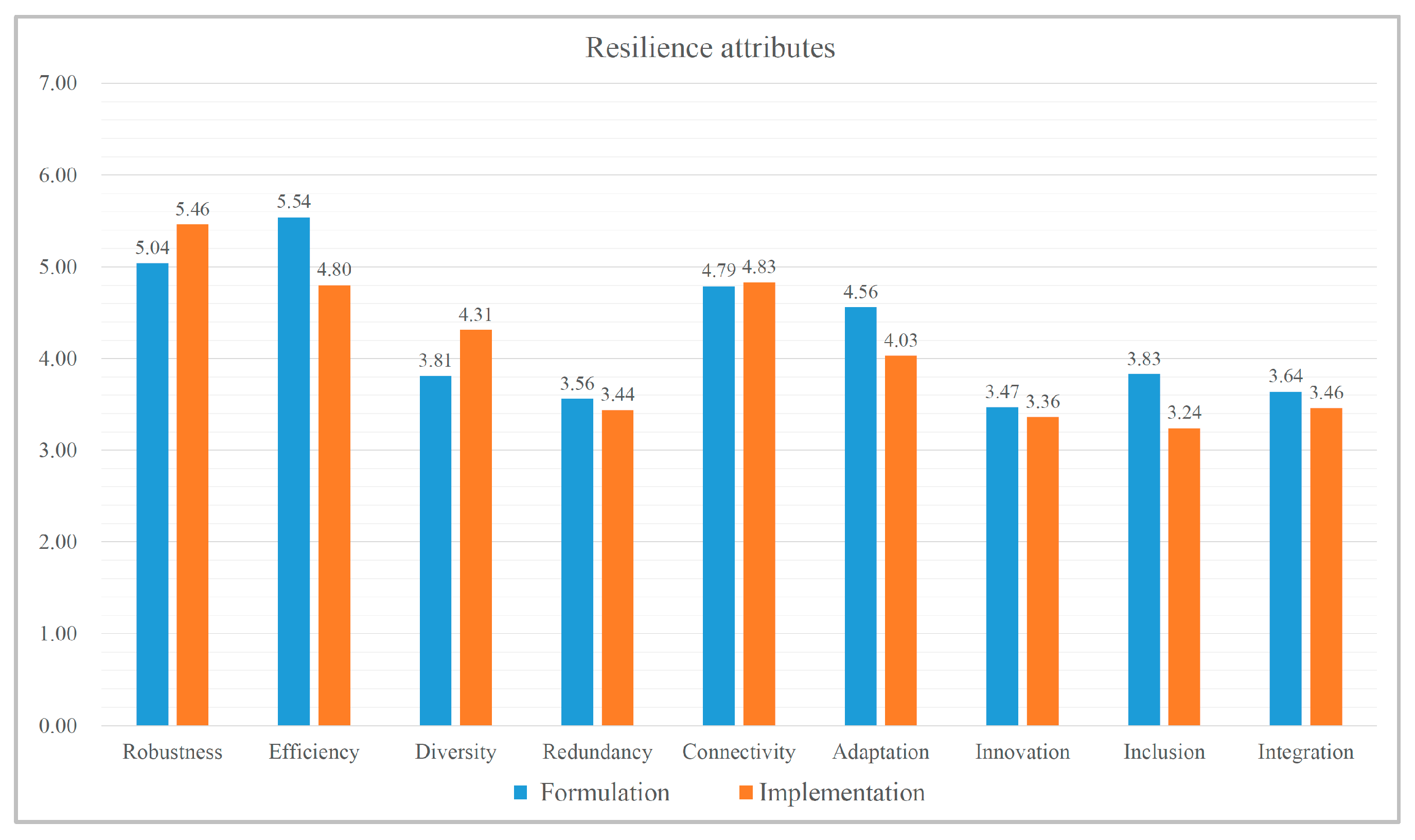

- (1)

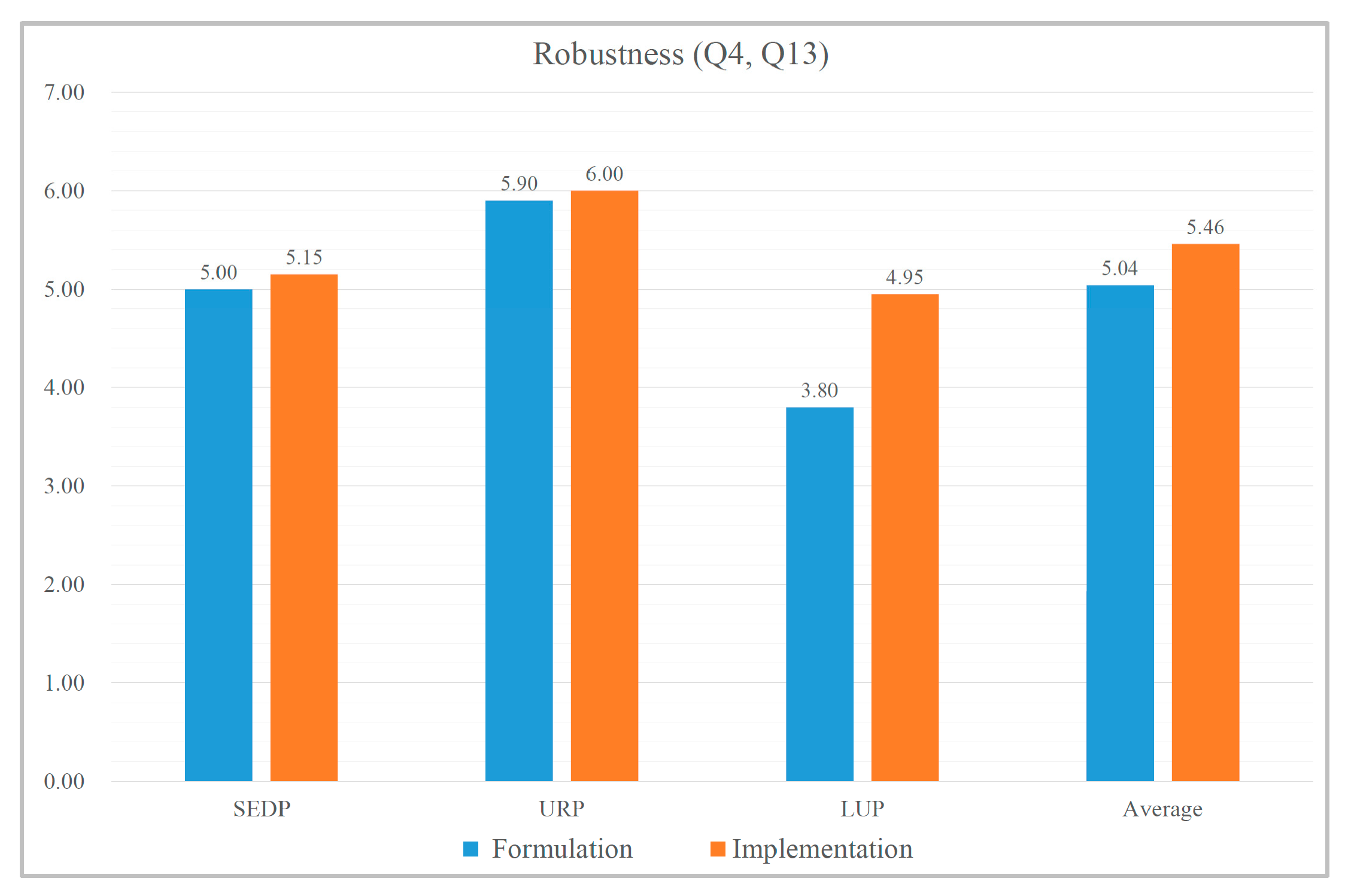

- Robustness

- (2)

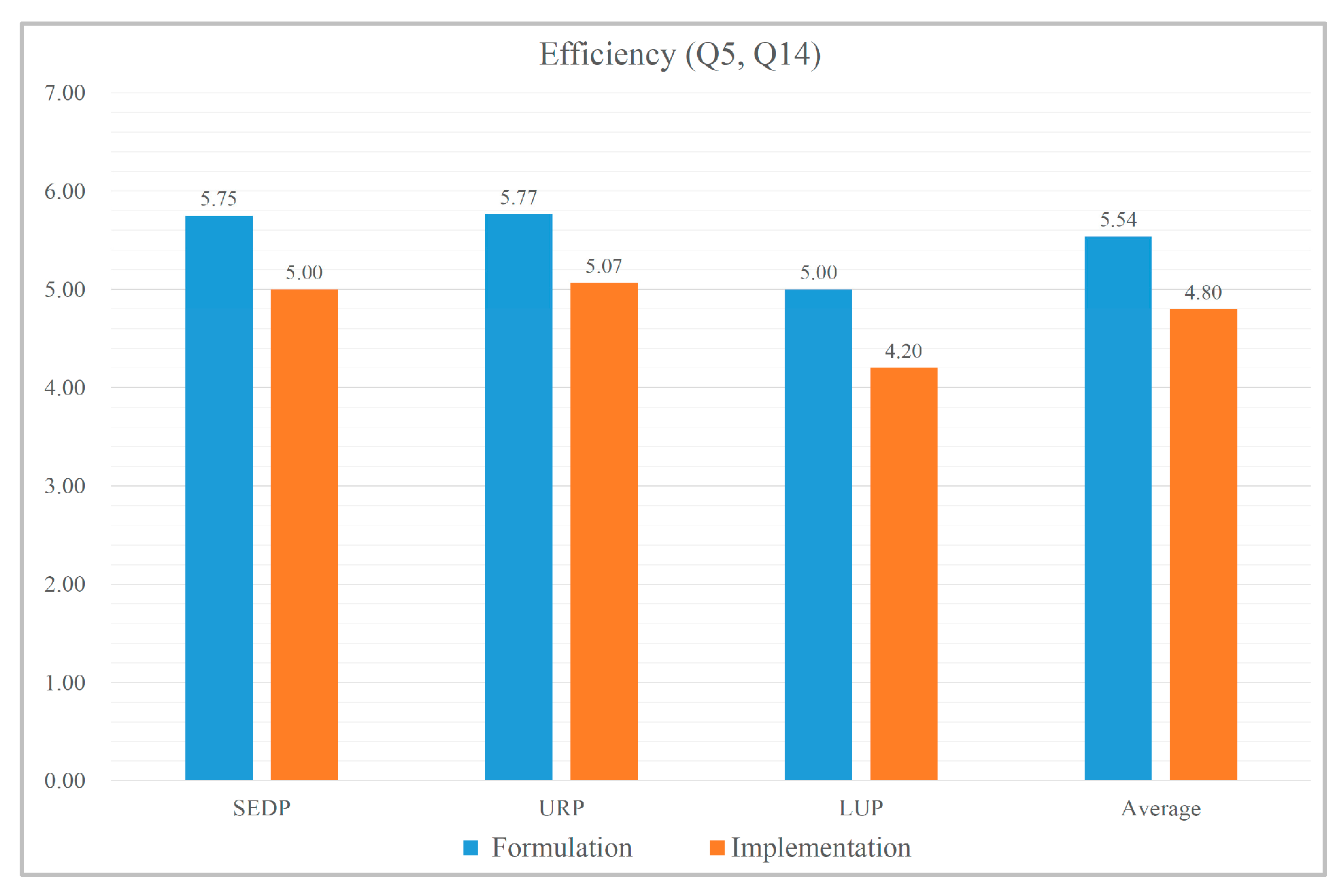

- Efficiency

- (3)

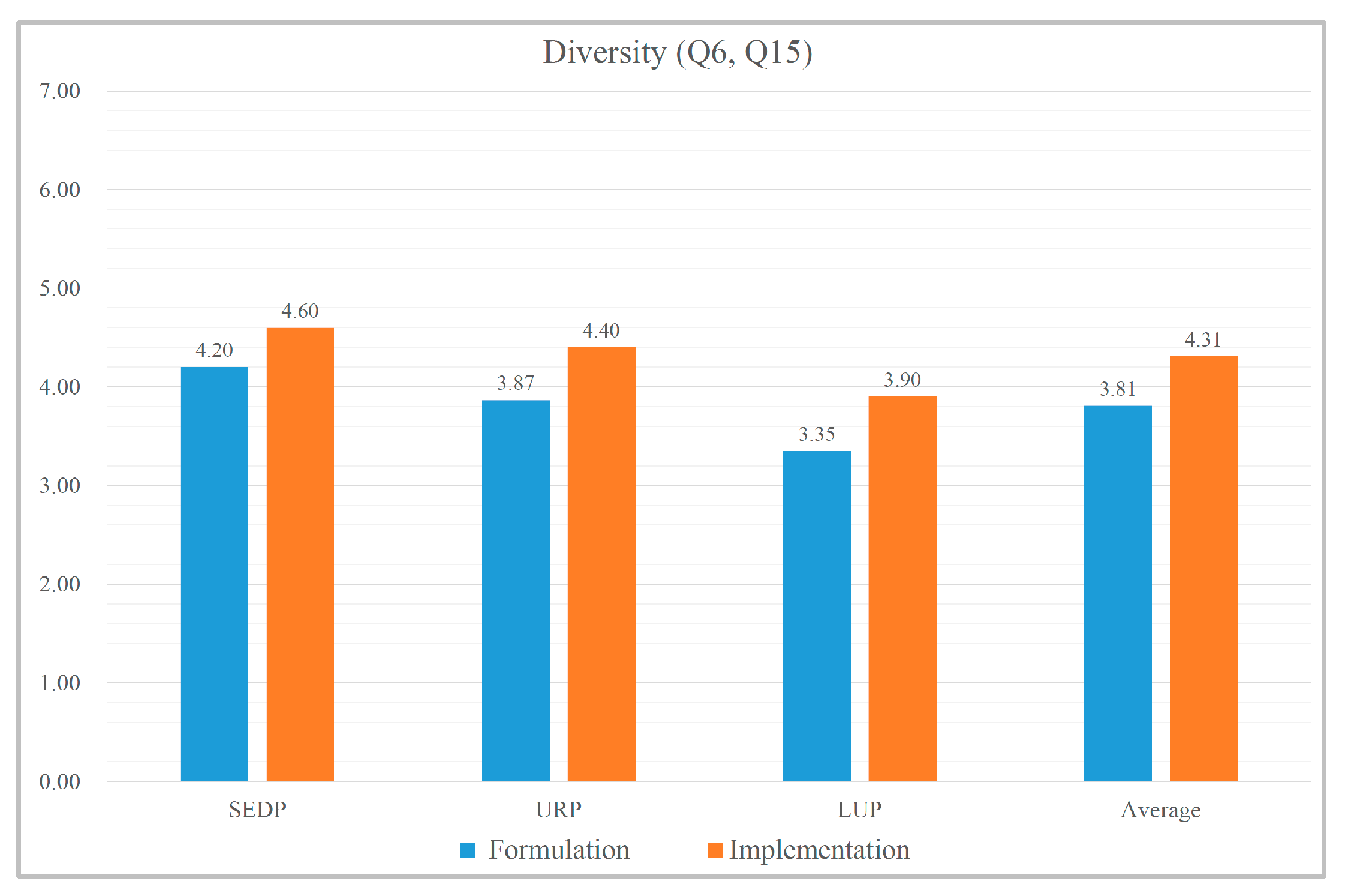

- Diversity

- (4)

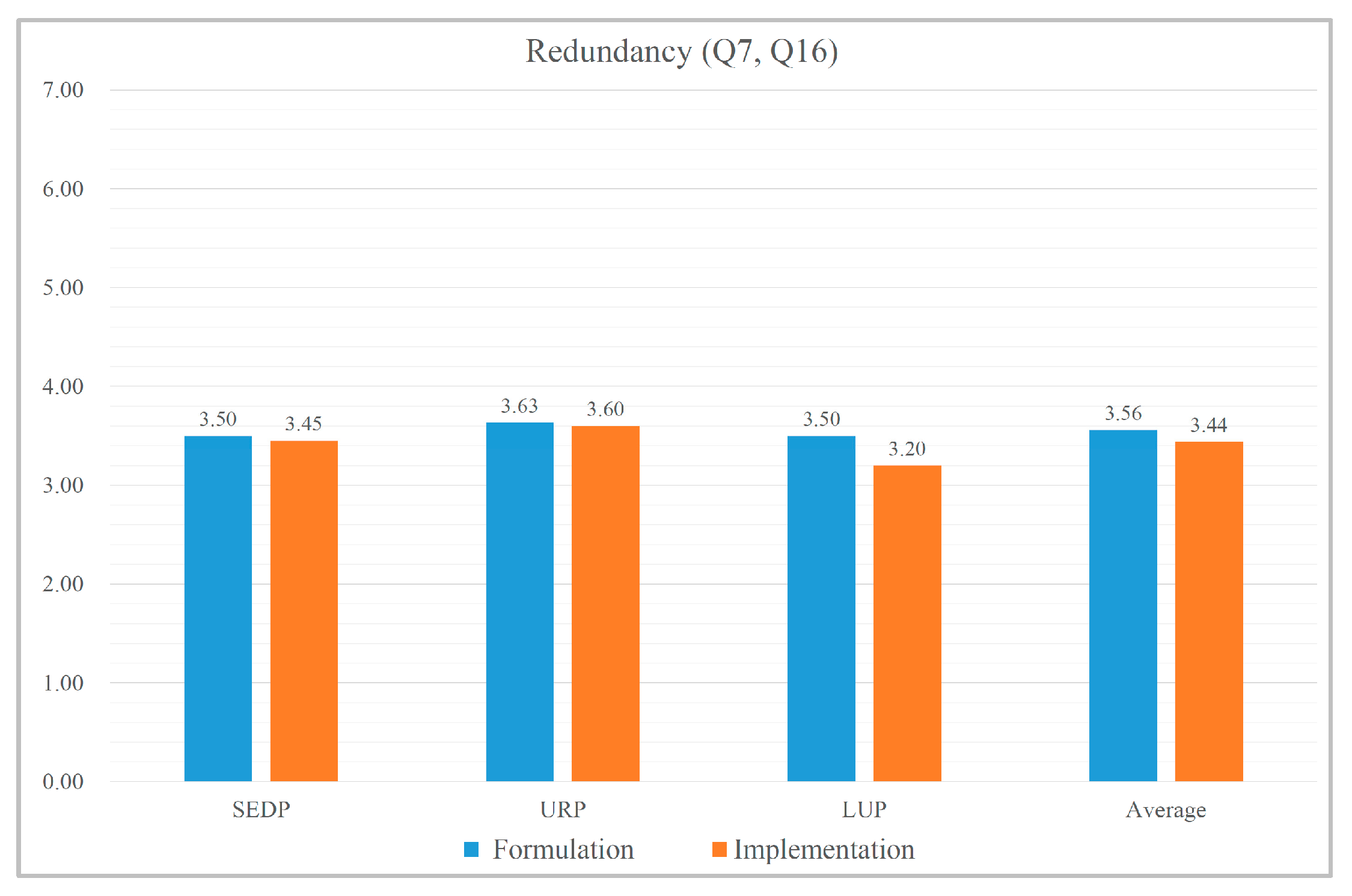

- Redundancy

- (5)

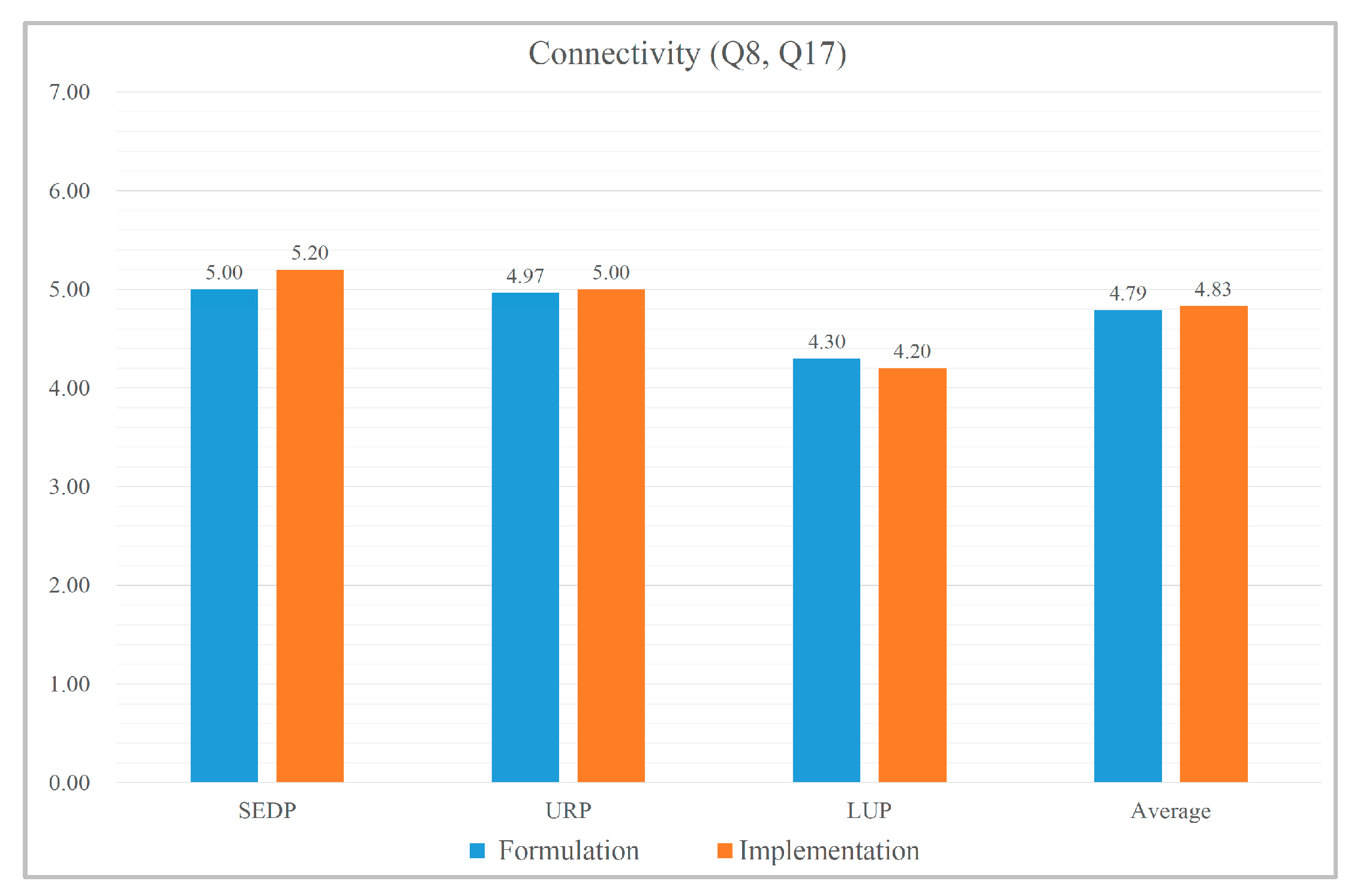

- Connectivity

- (6)

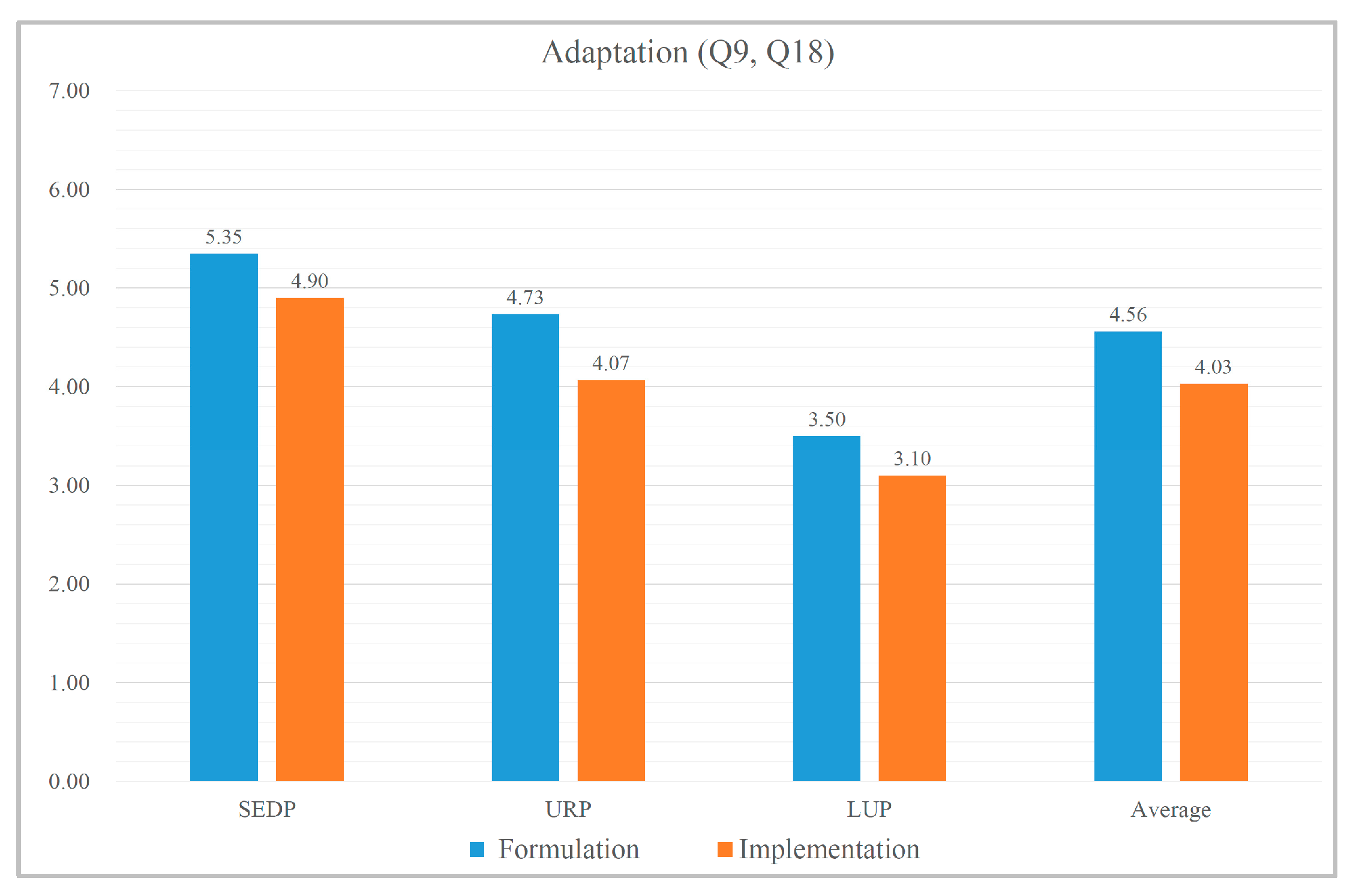

- Adaptation

- (7)

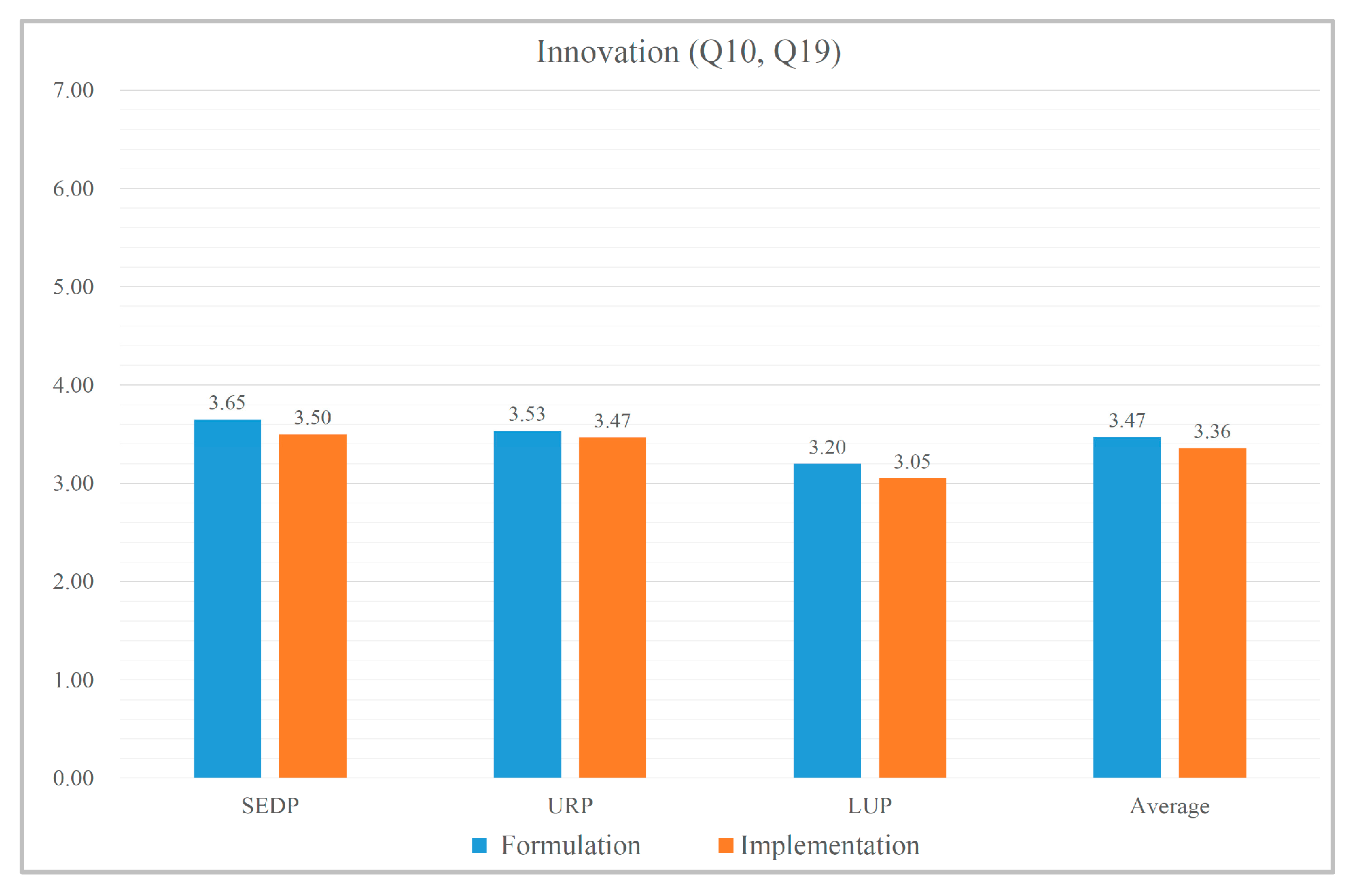

- Innovation

- (8)

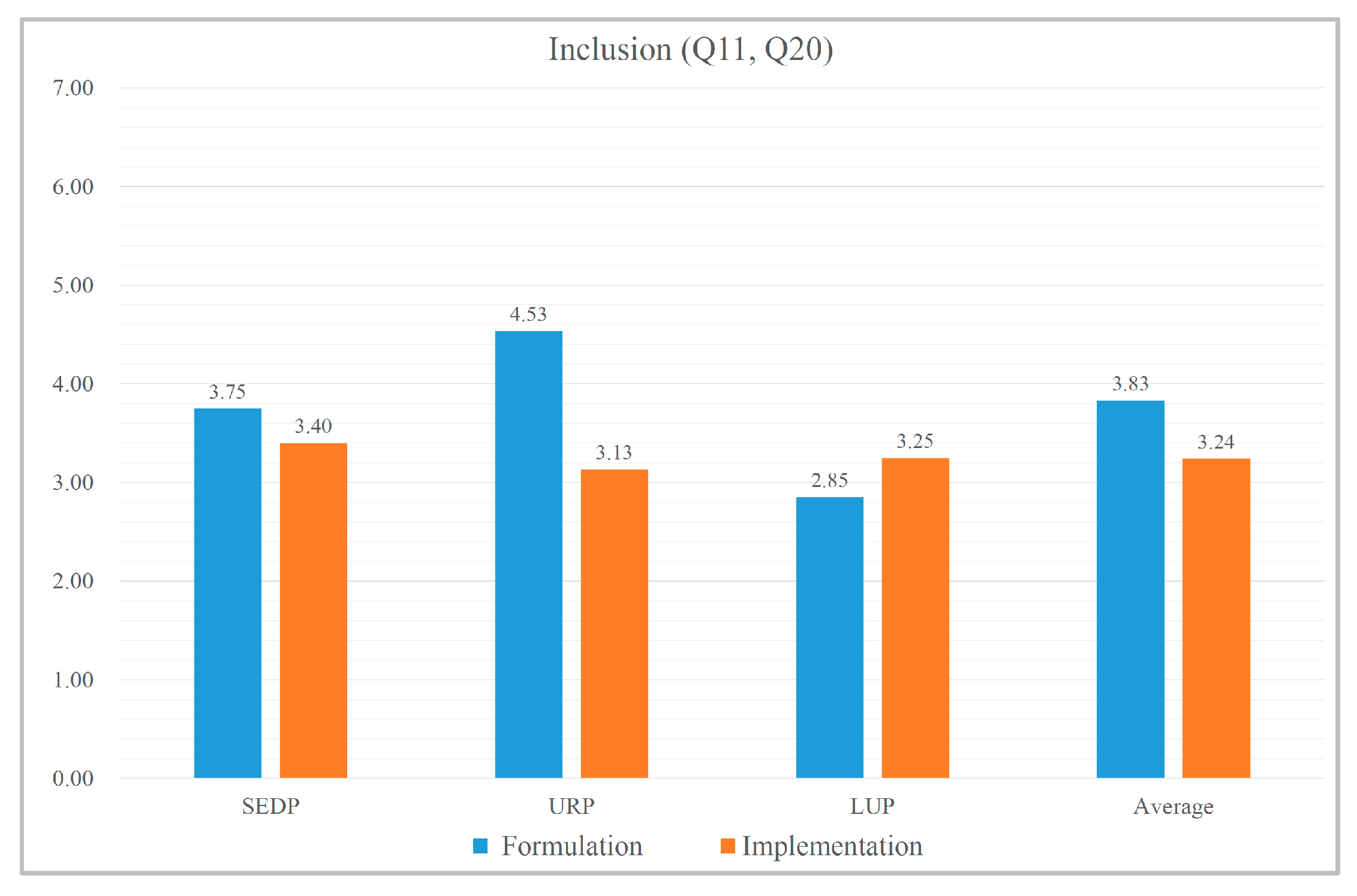

- Inclusion

- (9)

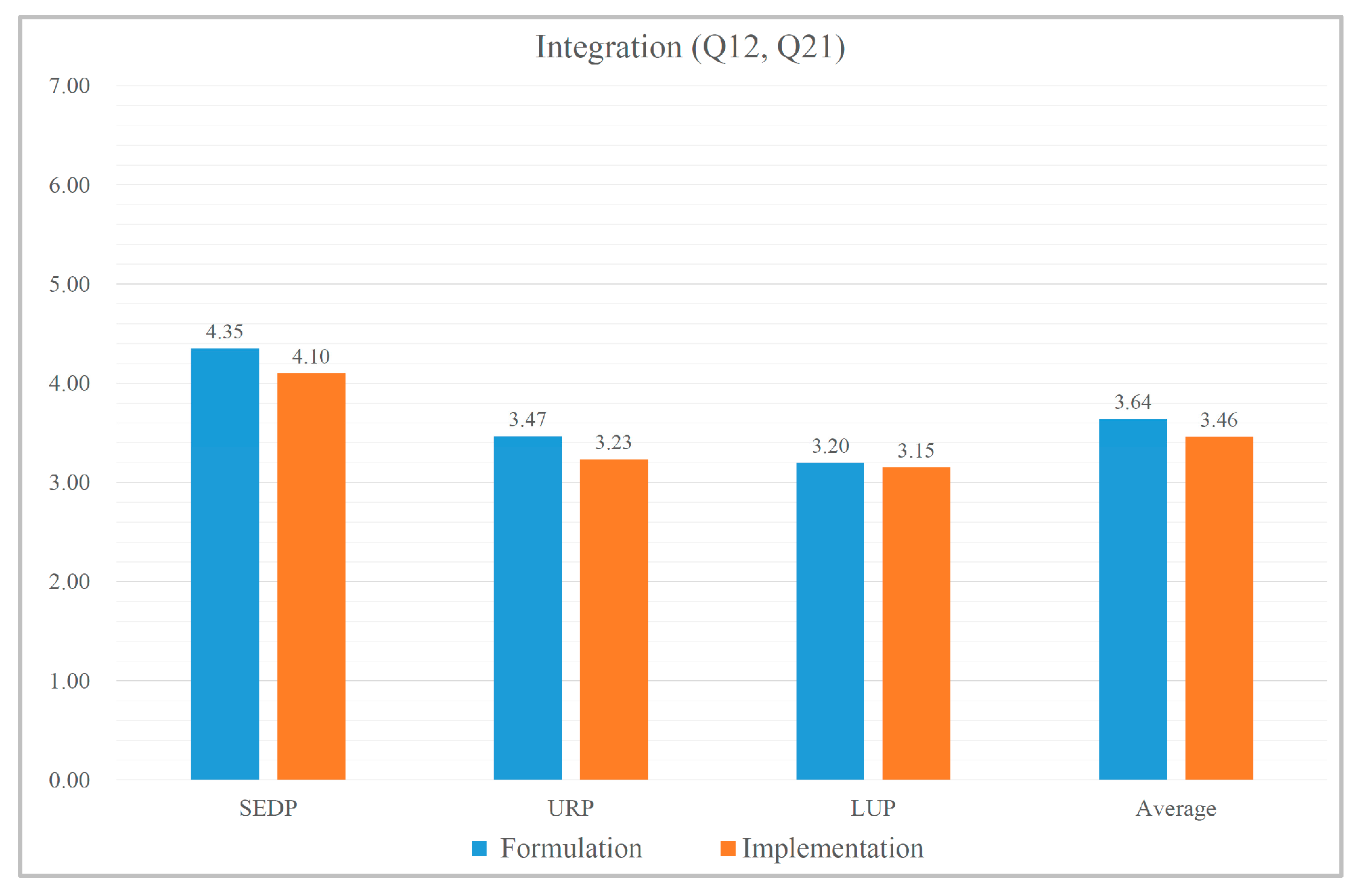

- Integration

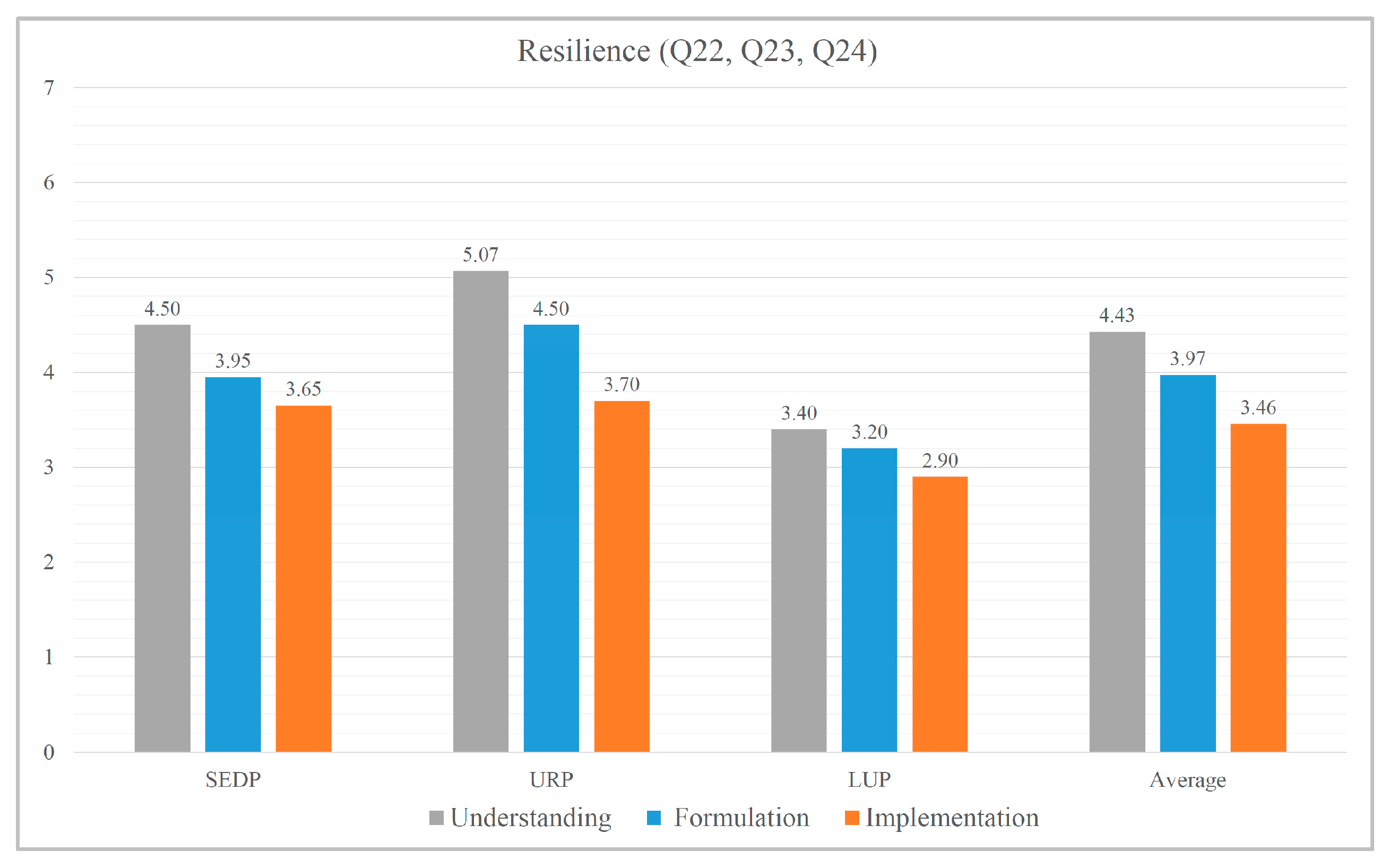

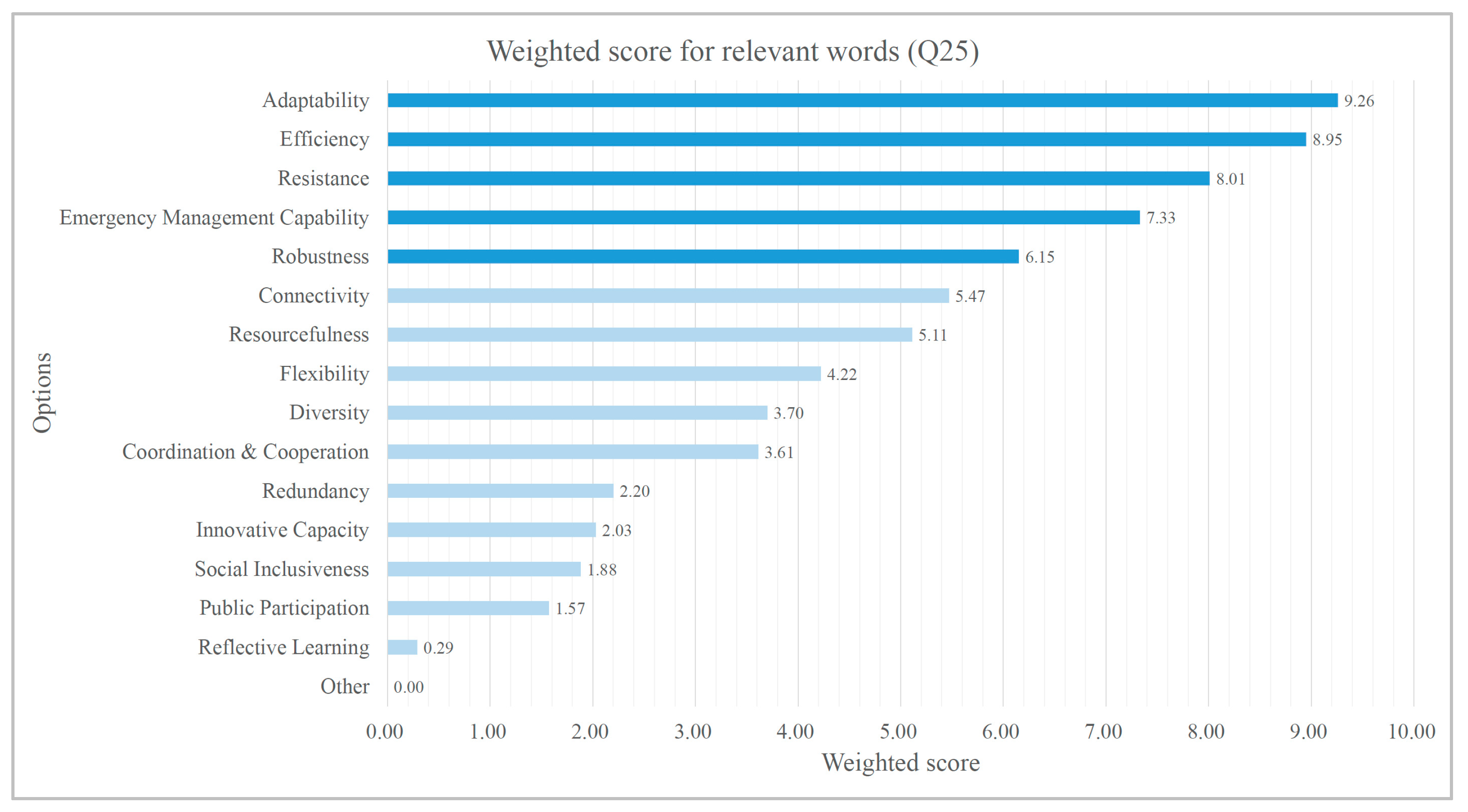

4.2.2. Resilience Awareness in Planners

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RTP | Resilience Thinking in Planning |

| SEDP | Socio-Economic Development Planning |

| URP | Urban and Rural Planning |

| LUP | Land Use Planning |

| TSP | Territorial Spatial Planning |

Appendix A. Major Resilience-Related Strategies Identified in Three Statutory Planning Documents

| Aspect | Items | Resilience-Related Strategies | Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban development | Implement innovation-driven development strategies to enhance urban innovation and creativity (p. 11). | Innovation-driven development | Innovation |

| Urban governance | Further, eliminate the differences in the status of urban and rural residents and reform the household registration system (p. 16). | Urban-rural linkage | Social connectivity, inclusion |

| Promote the downward shift in management focus and highlight the roles of districts (cities), counties, and communities in urban management (p. 17). | Administrative empowerment | Efficiency, adaptation | |

| Regional development | Improve regional coordination mechanisms and diversified development (p. 30) | Industry diversity and regional coordination | Diversity, integration |

| Urban spatial structure | Promote the transformation of urban spatial structure from a single center to a multi-level networked urban spatial structure (p. 55) | Polycentric urban structure | Diversity, redundancy |

| Ecology | Strengthen environmental protection and construct a Park City (p. 11). | Ecological planning and design | Diversity, adaptation |

| Rural construction | Construct rural information infrastructure, and promote network coverage of administrative villages (p. 19). | ICT Infrastructure | Efficiency, connectivity |

| Construct rural infrastructure, such as fire protection, meteorological disaster monitoring, and early warning systems, to improve disaster resistance (p. 20). | Disaster resistance and early warning | Robustness, efficiency | |

| Transport | Realize a reasonable connection among the road network system (p. 22); Speed up the construction of the urban rail transit network system (p. 73) | Physical network system | Connectivity efficiency |

| Infrastructure | Improve risk assessment and emergency response, and increase infrastructure construction, such as storage and disaster backup (p. 24) | ICT Infrastructure | Robustness, redundancy |

| Construct river embankments and urban drainage facilities to prevent and control floods, and improve the emergency response system for disasters (p. 26) | Disaster prevention and resistance | Robustness, adaptation | |

| Construct a multi-level infrastructure network system (such as public services, municipal utilities, water, energy, etc.) (p. 77) | Public facilities and services for response capacity | Robustness, connectivity | |

| Society | Increase the coverage of social insurance (p. 72); Build a more equitable and sustainable social insurance system covering all urban and rural residents (p. 106) | Social insurance system | Adaptation, inclusion |

| Protect the rights and interests of women, children, older people, and people with disabilities (p. 108) | Focus on vulnerable groups | Inclusion | |

| Improve social governance capabilities, and establish a social governance system featuring government responsibility, social coordination, and public participation (p. 15) | Social co-governance capacity | Inclusion, integration | |

| Public safety | Establish disaster prevention and mitigation systems covering disasters, accidents, and public health, and further improve various emergency plans (p. 78) | Disaster prevention and mitigation | Efficiency, adaptation |

| Establish risk assessment and emergency response systems, and improve the early warning and emergency response to natural disasters, accidents, public health, environmental risks, social security, and other emergency ability (p. 128) | risk assessment and emergency response capacity | Efficiency, adaptation |

| Aspect | Items | Resilience-Related Strategies | Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial structure | Relying on a radial/finger transport system to form a network and polycentric city system and spatial structure (p. 3) (p. 8) | network and polycentric structure | Diversity, redundancy |

| Transport system | Build a multi-level, networked transportation system (p. 12); Improve road density and traffic efficiency (p. 13) | Network transport system | Efficiency, connectivity |

| Environment | Build an ecological security spatial pattern, an ecological corridor and a biodiversity protection network (p. 6) (p. 8) | Urban and landscape ecological planning | Diversity, connectivity, adaptation |

| Public service facilities | Form a system of public service facilities covering urban and rural areas at five levels: central urban areas, new cities, key towns, general towns, and new rural communities (p. 15) | Infrastructure network system | Robustness connectivity |

| Public safety | Establish the comprehensive disaster prevention and mitigation system, and improve disaster adaptation capabilities (plan for earthquake, geology, flood, fire, dangerous item(p. 20). Improve urban resilience (p. 13). | disaster prevention and mitigation plan | Robustness adaptation |

| The construction land of towns and villages should avoid natural disaster-prone areas, and special protective measures must be taken if they cannot be avoided (p. 20) | Recognize disaster-prone areas | Robustness | |

| Post-disaster reconstruction | Strengthen the construction of refuge sites and passages, and improve the seismic standards of public facilities (p. 22) | Spatial planning and building standards | Robustness |

| Aspect | Items | Resilience-Related Strategies | Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecology Food security | Strengthen the protection of arable land and ecological land; Improve land use efficiency and prevent urban sprawl (p. 20) | Land control and management | Efficiency diversity |

Appendix B. Scripts of Questionnaire Survey for Planners

- Dear urban planners,

- Thank you very much for taking the time to participate in this online questionnaire survey. The questionnaire takes around 3 to 5 min to complete. Through this survey, we are eager to know your personal understanding and awareness of the term “resilience” in planning as a practitioner of urban planning. There are no right or wrong answers, so please complete the survey honestly, reflecting your genuine opinions. All of your answers and personal information will be kept confidential and used for research purposes only. Your assistance is much appreciated. Thank you again.

- Part One: Background Information. Please provide some of your personal background information so we can better analyze your answers.

- 1. How long have you worked in the urban planning field?

- ________________________(Year)________________________(Month)

- 2. How do you categorize the planning project(s) that you have participated (multiple choices possible)?

- □ A. Socio-Economic Development Planning (SEDP)

- □ B. Urban and Rural Planning (URP)

- □ C. Land Use Planning (LUP)

- □ D. _____________* Others

- 3. Which part(s) of work in planning project(s) have you taken part in (multiple choices possible)?

- □ A. Preliminary Investigation

- □ B. Plan Sketching

- □ C. Plan Development

- □ D. Approbation Preparation

- □ E. Publicity and Promotion

- □ F. _________________ * Others

- Part Two: Planning Formulation and Implementation Related. Please choose the item that matches your personal judgement the most. This part consists of two sub-sections.

- 2.1. Evaluation of Planning Process.

- 4. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to improve the city’s ability to withstand and resist external forces, such as disaster prevention?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 5. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to improve the city’s ability to respond quickly to emergency events, such as natural disasters?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 6. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to increase the diversity of urban land uses, infrastructure, industry, economic and social development?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 7. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to increase the redundancy of functionally similar components in city, such as road, shelters and facilities?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 8. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to improve the connectivity within and outside the city, not only physically but also socially?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 9. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to improve the city’s ability to be flexible and adaptive in the face of change?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 10. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to improve the city’s creativity to quickly find different ways to achieve goals or meet their needs during a shock?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 11. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to the development of broad consultation and involvement of communities, particularly of the vulnerable groups?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 12. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to the integration and alignment between urban systems and departments to promote stronger decision-making?

- Not Considered at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Considered

- 2.2 Evaluation of Planning Effect.

- 13. Do you think that planning has promoted local area’s capability to resist and cope with disasters?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- 14. Do you think that planning has promoted the efficiency of the local area to respond quickly to emergency events?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- 15. Do you think that planning has promoted the diversity of urban land uses, infrastructure, industry, economic and social development?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- 16. Do you think that planning has promoted the redundancy of functionally similar components in city, such as road, shelters and facilities?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- 17. Do you think that planning has promoted the connectivity within and outside the city, not only physically but also socially?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- 18. Do you think that planning has promoted the city’s ability to be flexible and adaptive in the face of change?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- 19. Do you think that planning has promoted the city’s creativity to quickly find different ways to achieve goals or meet its needs during a shock?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- 20. Do you think that residents’ opinions have been embodied in the final plan, and planning has satisfied local communities’ current needs, particularly of the vulnerable groups?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- 21. Do you think that planning has reflected the integration and coordination between different urban systems and departments, different areas and different stakeholders?

- Not Promoted at All ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Substantially Promoted

- Part Three: Integrated Evaluation and Urban Resilience Related. Please share with us your understanding of urban resilience.

- 22. Have you ever heard the concept urban resilience prior to taking part in this online questionnaire survey?

- Never Heard Before ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Understood

- 23. During the planning process, how do you give consideration to improve the urban resilience?

- Never Heard Before ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Understood

- 24. Do you think that planning has reflected urban resilience thinking?

- Never Heard Before ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 ○ 6 ○ 7 Fully Understood

- 25. Please choose 5 most relevant words with urban resilience in your opinion, and order them with importance.

- [ ] Robustness

- [ ] Resistance

- [ ] Efficiency

- [ ] Connectivity

- [ ] Diversity

- [ ] Redundancy

- [ ] Adaptability

- [ ] Flexibility

- [ ] Coordination & Cooperation

- [ ] Resourcefulness

- [ ] Social Inclusiveness

- [ ] Reflective Learning

- [ ] Emergency Management Capability

- [ ] Public Participation

- [ ] Innovative Capacity

- [ ] Others

- 26. If you have chosen “others” in Question 25, please write down your own words below.

- _________________________________

Appendix C. The List of Respondent Planners

| No. | Current Position | Current Organization | Planning Type |

| 1 | Government official | Chengdu Municipal Development and Reform Commission (Development Planning Division) | SEDP |

| 2 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 3 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 4 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 5 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 6 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 7 | Researcher, planner | Chengdu Institute of Economic Development (Economic Information Center) | SEDP |

| 8 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 9 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 10 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 11 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 12 | Government official | Policy Research Office of Chengdu Municipal Committee | SEDP |

| 13 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 14 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 15 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 16 | Researcher, planner | Chengdu Reform and Development Research Center | SEDP |

| 17 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 18 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 19 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 20 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | SEDP |

| 21 | planner | Chengdu Institute of Planning and Design | URP |

| 22 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 23 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 24 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 25 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 26 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 27 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 28 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 29 | Researcher, planner | Chengdu Planning Research and Application Technology Center | URP |

| 30 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 31 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 32 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 33 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 34 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 35 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 36 | Planner | China Southwest Architecture (Planning and Municipal Institute) | URP |

| 37 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 38 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 39 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 40 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 41 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 42 | Academic and planner | Sichuan University Engineering Design & Research Institute | URP |

| 43 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 44 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 45 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 46 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 47 | Academic and planner | Southwest Jiaotong University Planning and Design Institute | URP |

| 48 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 49 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 50 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | URP |

| 51 | Planner | Sichuan Land Spatial Planning Institute | LUP |

| 52 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 53 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 54 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 55 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 56 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 57 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 58 | Academic and planner | Sichuan Agricultural University Land Survey and Planning Research Office | LUP |

| 59 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 60 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 61 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 62 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 63 | Researcher, planner | Sichuan Urban and Rural Construction Research Institute | LUP |

| 64 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 65 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 66 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 67 | Planner | Sichuan Provincial Land Reclamation Center | LUP |

| 68 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 69 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

| 70 | - (ibid) | - (ibid) | LUP |

References

- Rentschler, J.; Avner, P.; Marconcini, M.; Su, R.; Strano, E.; Vousdoukas, M.; Hallegatte, S. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 2023, 622, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.S.; Maneta, M.P.; Sain, S.R.; Madaus, L.E.; Hacker, J.P. The role of climate and population change in global flood exposure and vulnerability. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munene, M.B.; Swartling, Å.G.; Thomalla, F. Adaptive governance as a catalyst for transforming the relationship between development and disaster risk through the Sendai Framework? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Gonçalves, L.A.P.J. Urban resilience: A conceptual framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuti, D.; Bellucci, M.; Manetti, G. Company disclosures concerning the resilience of cities from the SDGs perspective. Cities 2020, 99, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A. Of resilient places: Planning for urban resilience. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Kates, J.; Malecha, M.; Masterson, J.; Shea, P.; Yu, S. Using a resilience scorecard to improve local planning for vulnerability to hazards and climate change: An application in two cities. Cities 2021, 119, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.; Falcão, M.J.; Komljenovic, D.; de Almeida, N.M. A systematic literature review on urban resilience enabled with asset and disaster risk management approaches and GIS-based decision support tools. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Newman, G.; Lee, J.; Combs, T.; Kolosna, C.; Salvesen, D. Evaluation of networks of plans and vulnerability to hazards and climate change: A resilience scorecard. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 81, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlimann, A.; Moosavi, S.; Browne, G.R. Urban planning policy must do more to integrate climate change adaptation and mitigation actions. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarveysi, F.; Alipour, A.; Moftakhari, H.; Jafarzadegan, K.; Moradkhani, H. Block-level vulnerability assessment reveals disproportionate impacts of natural hazards across the United States. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.Q.; Zhao, S. Urbanization process and induced environmental geological hazards in China. Nat. Hazards 2013, 67, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, E.; Zhang, H. Examining the coupling relationship between urbanization and natural disasters: Pearl River Delta. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 55, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Planning centrality, market instruments: Governing Chinese urban transformation. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1383–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Territory spatial planning and national governance system in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Shaw, K.; Haider, L.J.; Quinlan, A.E.; Peterson, G.D.; Wilkinson, C.; Fünfgeld, H.; McEvoy, D.; Porter, L.; Davoudi, S. Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelleri, L.; Waters, J.J.; Olazabal, M.; Minucci, G. Resilience trade-offs: Addressing multiple scales and temporal aspects of urban resilience. Environ. Urban. 2015, 27, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Takeuchi, K.; Folke, C. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, R.M.; Anwar, N.H.; Dixit, A.; Hutanuwatr, K.; Jayaraman, T.; McGregor, J.A.; Menon, M.R.; Moench, M.; Pelling, M.; Roberts, D. Re-imagining inclusive urban futures for transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 20, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Grove, J.M. Resilient cities: Meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. Systemic resilience. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, G.A. Sustainability and community resilience. Glob. Environ. Change B 1999, 1, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, J.; Doyon, A. Building urban resilience with nature-based solutions. Cities 2019, 95, 102483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, why? Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.; Davoudi, S. The politics of resilience for planning: A cautionary note. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S.; Gunderson, L.H. Resilience and adaptive cycles. In Panarchy; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin, E.F. Conditions for sustainability of human–environment systems: Information, motivation, and capacity. Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, C. Social-ecological resilience: Insights and issues for planning theory. Plan. Theory 2012, 11, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godschalk, D.R. Urban hazard mitigation: Creating resilient cities. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2003, 4, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.; Morera, B. City Resilience Framework; Ove Arup and Partners: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhauer, M. The role of spatial planning in strengthening urban resilience. In Resilience of Cities to Terrorist and Other Threats; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 273–298. [Google Scholar]

- Taşan-Kok, T.; Stead, D.; Lu, P. Conceptual overview of resilience. In Resilience Thinking in Urban Planning; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y. Urban Resilience in China’s Post-Disaster Reconstruction Planning. Ph.D. Thesis, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan, B.; Zhang, Q.; Farzaneh, H.; Utama, N.A.; Ishihara, K.N. Resilience, sustainability and risk management: A focus on energy. Challenges 2012, 3, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaans, M.; Waterhout, B. Building up resilience in cities worldwide– Rotterdam as participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme. Cities 2017, 61, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardekker, A.; Wilk, B.; Brown, V.; Uittenbroek, C.; Mees, H.; Driessen, P.; Wassen, M.; Molenaar, A.; Walda, J.; Runhaar, H. A diagnostic tool for policymaking on urban resilience. Cities 2020, 101, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lim, U. Urban resilience in climate change adaptation: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, P.; Bryant, M. Resilience as a framework for urbanism and recovery. J. Landsc. Archit. 2011, 6, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.H.; Anderies, J.M.; Abel, N. From metaphor to measurement: Resilience of what to what? Ecosystems 2001, 4, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Mitchell, T.; Polack, E.; Guenther, B. Urban governance for adaptation: Assessing climate change resilience in ten Asian cities. IDS Work. Pap. 2009, 315, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, P.; Oliveira, V.; Martins, A. Evaluating resilience in planning. In Resilience Thinking in Urban Planning; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrou, N.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Resilience plans in the US: An evaluation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 65, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shao, Y. The role of the state in China’s post-disaster reconstruction planning. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, R.Z.; Pelling, M. Institutionally configured risk: Assessing urban resilience and disaster risk reduction to heat wave risk in London. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Godschalk, D. Searching for the good plan: A meta-analysis of plan quality studies. J. Plan. Lit. 2009, 23, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Evaluation of Disaster Resilience of Communities. Master’s Thesis, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Que, W.; Liu, Y.G.; Cao, L.; Liu, S.B.; Zhang, J. Is resilience capacity index performing well? Evidence from 26 provinces. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y. Assessing urban resilience in China from the perspective of socioeconomic and ecological sustainability. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 102, 107163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Kidokoro, T.; Seta, F.; Shu, B. Spatial-Temporal Assessment of Urban Resilience to Disasters: A Case Study in Chengdu, China. Land 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L.J. The politics of resilient cities: Whose resilience and whose city? Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abujder Ochoa, W.A.; Neto, A.I.; Vitorio Junior, P.C.; Calabokis, O.P.; Ballesteros-Ballesteros, V. The theory of complexity and sustainable urban development: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; He, W. Resilience policies in China: An analysis of central-level policies. Policy Stud. 2025, 46, 918–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attributes | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Robustness | Ability to resist attacks or other external forces. The robust design anticipates potential system failures, ensuring that failures are predictable, secure, and not disproportionate to the cause. | [33,38,39,40] |

| Efficiency | The positive relationship between the functioning of a static urban system in relation to the operation of a dynamic system. | [33,41] |

| Diversity | The system has several functionally different components to protect it against various threats. The more diversity the system possesses, the better its ability to adapt to a wide range of diverse circumstances. | [33,42] |

| Redundancy | The existence of several functionally similar components ensures that the system does not fail when one of the components fails. | [33,38,39,40,41,42] |

| Connectivity | Connected system components for support and mutual interaction. | [33] |

| Adaptation | Ability to learn from experience and be flexible in the face of change. | [33,39,40,41,42] |

| Innovation | Ability to quickly find different ways to achieve goals or meet their needs during a shock, or when a system is under stress. | [39,40,41,42] |

| Inclusion | Development of broad consultation and community involvement, particularly among the most vulnerable groups, in the development of processes and plans. An inclusive approach contributed to a joint vision to build the city’s resilience. | [33,39] |

| Integration | Integration and alignment between urban systems promote stronger decision-making and ensure that all users/components mutually support each other for a common outcome. | [33,39] |

| Type of Plan | Content | Document |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-Economic Development Planning (SEDP) | A guiding plan of economic and social development (also called the five-year plan), including development, industry, transportation, education, urban space and function, infrastructure, society, environment, culture, reform, well-being, etc. | Chengdu City National Socio-economic Development Planning (2011–2015) Chengdu City National Socio-economic Development Planning (2016–2020) |

| Legal basis: Constitution of China (1982, 2018 update) | ||

| Urban and Rural Planning (URP) | Includes urban system planning, city planning, town planning, township planning, and village planning. City or town planning provides master planning and detailed planning. (Here, focus on city master planning) | Chengdu City Comprehensive Planning (2011–2020) Chengdu City Comprehensive Planning (2016–2035) |

| Legal basis: Urban and Rural Planning Law (2008, 2019 update) | ||

| Land Use Planning (LUP) | The land use is regulated, and the land is divided into agricultural land, construction land, and unused land. Strictly restrict the conversion of agricultural land to construction land, control the total amount of construction land, and implement special protection for cultivated land. | Chengdu City Land Use Master Planning (2006–2020, 2014 update) |

| Legal basis: Land Administration Law (1986, 2019 update) |

| Attributes | Illustration of Different Resilience Perspectives | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Engineering Resilience | Ecological Resilience | Socio-Ecological Resilience | |

| Robustness | ++ | + | + |

| Efficiency | ++ | + | + |

| Diversity | − | + | + |

| Redundancy | − | + | + |

| Connectivity | − | physical: + social: − | physical: + social: + |

| Adaptation | − | − | + |

| Innovation | − | − | + |

| Inclusion | − | − | ++ |

| Integration | − | − | ++ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, Y.; Kidokoro, T.; Seta, F.; Shu, B. Integrating Resilience Thinking into Urban Planning: An Evaluation of Urban Policy and Practice in Chengdu, China. Systems 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010010

Wei Y, Kidokoro T, Seta F, Shu B. Integrating Resilience Thinking into Urban Planning: An Evaluation of Urban Policy and Practice in Chengdu, China. Systems. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Yang, Tetsuo Kidokoro, Fumihiko Seta, and Bo Shu. 2026. "Integrating Resilience Thinking into Urban Planning: An Evaluation of Urban Policy and Practice in Chengdu, China" Systems 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010010

APA StyleWei, Y., Kidokoro, T., Seta, F., & Shu, B. (2026). Integrating Resilience Thinking into Urban Planning: An Evaluation of Urban Policy and Practice in Chengdu, China. Systems, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010010