1. Introduction

Digital transformation, the strategic integration of digital technologies into business processes, models, and interactions, is more than a technology upgrade. It requires holistic change across people, processes, and technology domains [

1]. Scholars define digital transformation as a process that aims to improve an entity by triggering significant changes to its properties through combinations of information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies [

2]. This highlights that successful transformation is socio-technical in nature. New technologies must be accompanied by shifts in culture, skills, and processes to realise performance gains. In practice, human and organisational factors often determine whether digital technologies deliver their promised benefits [

3].

In parallel, organisations continue to rely on Lean management principles to drive operational excellence. Lean management focuses on eliminating waste and continuously improving processes [

4]. Beyond waste reduction, Lean is typically characterised by defining value from the customer perspective, simplifying and synchronising process flows, using pull-based systems, standardising and visualising work, and applying structured problem solving, all underpinned by a strong emphasis on respect for people and learning [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Within Lean, soft practices refer to people-focused elements such as employee involvement, customer collaboration, supplier partnerships, leadership, and training, rather than technical tools alone [

3]. Lean is fundamentally a socio-technical system that combines process techniques with a culture of continuous improvement and stakeholder engagement [

5]. Following existing Lean 4.0 research that conceptualises the construct as the integration of Lean practices and Industry 4.0 technologies [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], we adopt a more specific socio-technical view in this study by treating Lean soft practices (LSPs) as the Lean dimension and Industry 4.0 technologies (I4Ts) as the digital dimension. Prior research shows that organisations that succeed with Lean distinguish themselves through extensive adoption of these soft practices [

3], which create an inclusive culture where frontline knowledge and partner input drive innovation and quality.

As Industry 4.0 diffuses, an important question arises: how do advanced digital technologies intersect with Lean’s human-centred practices? Some scholars initially posited a tension between high automation and human-driven improvement [

11]. Increasingly, however, research suggests a complementary relationship, often termed Lean 4.0, where I4Ts and Lean principles reinforce each other [

12]. For example, real time data from IoT sensors can empower employees to identify waste or quality issues faster, while a strong continuous improvement culture helps firms adapt new technologies [

13]. Integrating I4Ts into a Lean framework has been found to improve flexibility and accelerate the maturation of Lean practices [

14,

15]. Rather than replacing Lean, advanced technologies can strengthen Lean philosophy by providing richer information and automation that support human decision making [

16]. Empirical evidence also shows that Lean and digital transformation initiatives deliver greater performance together than separately. For instance, Lean practices and factory digitalisation each contribute to operational gains, but their combined use produces a stronger synergistic effect [

17]. Other studies report that Lean practices may mediate or moderate the impact of I4Ts on performance [

14,

18], suggesting that organisational people capabilities critically shape the value gained from technology.

Despite these insights, a clear research gap remains in understanding how LSPs and I4Ts interact as a socio-technical system during digital transformation. Much of the existing Lean 4.0 work is either conceptual [

7,

9] or quantitative [

10,

13,

17], often centred on operational performance metrics in manufacturing contexts [

19,

20,

21]. While these studies establish that Lean and I4Ts can be complementary, they do not explain the mechanisms through which LSPs enable I4T adoption, or how their interaction reshapes work systems in practice. The roles of employee engagement, customer input, and supplier collaboration—and how these social dynamics interface with new digital systems—remain under-explored, particularly through in-depth qualitative inquiry focused on socio-technical interactions [

16,

22]. Rich, empirically grounded accounts of how organisations integrate the human and technological sides of transformation are still limited [

14,

20]. Key questions persist. What cultural or skills barriers emerge during Lean 4.0 integration? How do organisations ensure their workforce is prepared to leverage new technologies? How do social and technical subsystems co-evolve during digital transformation? Addressing these questions is academically and practically important. Academically, examining Lean and I4T integration through a socio-technical lens can build a more holistic theory of digital transformation success by incorporating the human side alongside technological capabilities [

2,

23,

24]. Practically, as firms invest heavily in I4T projects, guidance is needed on aligning technology initiatives with organisational culture and capabilities so that costly systems do not result in digital waste [

14].

This study fills this gap by qualitatively examining, through a socio-technical systems lens, the convergence of I4Ts and LSPs during digital transformation. Accordingly, we pose the following research question:

RQ: How do Lean soft practices and I4Ts interact as a socio-technical system to drive digital transformation and organisational performance?

By conducting an inductive thematic analysis of online questionnaire responses from 15 managers and professionals across multiple industries, we identify emergent themes, success patterns, and challenges in the Lean 4.0 socio-technical journey. This research contributes in two ways. First, it provides an empirically grounded thematic synthesis that extends Lean 4.0 literature by foregrounding human and organisational factors in digital transformation. Second, it develops an empirically based conceptual framework, guided by socio-technical systems theory, illustrating the dynamic relationships between LSPs as the social system, I4T adoption as the technical system, shifts in work processes as the work system, and resulting performance outcomes. This framework maps how social and technical systems co-evolve during digital transformation, advancing theory and offering practical insights for achieving effective and sustainable Lean 4.0 implementation.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on Industry 4.0, LSPs, and their integration.

Section 3 describes the research design, sampling strategy, and data analysis procedures.

Section 4 presents the empirical results in terms of four socio-technical systems.

Section 5 discusses the theoretical and managerial contributions of the study.

Section 6 concludes with limitations and directions for future research.

4. Results

Our analysis revealed four interrelated systems that underpin the socio-technical dynamics of digital transformation: social systems, technical systems, work systems, and performance outcomes. The social system captures the human-centred Lean practices, including stakeholder involvement, continuous training, and empowerment, that create a receptive culture for change. The technical system consists of the I4Ts adopted and integrated into operations. As the social and technical systems interact, they reshape the work system, meaning the processes, workflows, and business activities through which value is delivered, including operational processes, customer experience, and business models. Together, these changes generate performance outcomes such as stronger operational efficiency, higher employee engagement, improved customer satisfaction, and better financial results. The following subsections detail each system and explain how they interact and reinforce one another to enable successful Lean 4.0 digital transformation, with participant quotes referenced as P1 to P15.

4.1. Social Systems

The first system, social systems, encompasses the human-centred practices and cultural conditions that establish the foundation for Lean 4.0 integration. Participants emphasised that continuous people development and broad stakeholder engagement create an environment that is ready for digital transformation. A major feature of the social system is employee training and skill development. Many organisations described ongoing training programs, ranging from quarterly bootcamps to weekly workshops, aimed at building both Lean capability and digital literacy. One participant outlined a structured approach: “

We offer training opportunities every quarter where we train employees on their technical skills, emerging new technology, and collaboration skills. Investing in employee growth empowers them to contribute effectively” (P14). This shows how regular and well-rounded training, covering technical and interpersonal skills, builds competence while also increasing confidence and involvement, aligning with Lean’s respect for people principle. Other participants highlighted a learning culture where upskilling is continuous and driven by need. In some cases, organisations funded external courses or granted study time whenever new competencies were required (P7), ensuring that workforce capability evolves alongside technological change. A small number of participants noted gaps. For example, one stated their organisation offers “

almost no training beyond initial hire” (P15), relying instead on ad hoc mentoring. These cases were treated as exceptions, and participants acknowledged that limited training weakens readiness for I4T adoption. Overall, the findings indicate that organisations that perform well in digital transformation cultivate a strong learning culture and address skills gaps early so employees remain motivated and prepared to adopt new technologies [

41].

Another core element of the social system is stakeholder involvement and collaboration. Participants consistently reported deliberate efforts to involve employees, customers, and suppliers in improvement initiatives and decision making. Many organisations established open communication channels and feedback loops, often supported by digital platforms, to capture frontline insight. One participant noted: “Decision making processes always involve employees as they are the ones who know our customers best” (P5). Frontline staff who engage with products and customers daily were viewed as a vital source of improvement ideas, reflecting Lean’s view that value is created where work happens. Several organisations formalised this through structured suggestion systems. For instance, P3 described two distinct feedback channels that feed into evaluation and implementation: “Our company has two separate channels for managing feedback and improvements: an internal one for employees, and an external one for end customers. The most promising ideas enter the normal evaluation cycle and if deemed valid they are then transferred to production. For colleagues, we have also established a company award; every year we reward the best ideas” (P3). This example illustrates how digital platforms and incentive programs can work together to encourage continuous improvement participation in a connected Lean environment.

Customer involvement was also widely emphasised. Participants described actively seeking customer feedback through digital tools, embedding it into product development, and in some cases co-designing solutions with clients. As one participant explained, engagement means “staying close to customers, employees, and suppliers, we openly engage about what we are doing and where we can improve” (P7). This transparency and inclusive dialogue helps ensure that transformation remains aligned with stakeholder needs and gains broad support. Supplier collaboration was mentioned less frequently but still formed part of the social system in several cases, particularly where organisations pursued joint improvement and data sharing with key partners (P2).

In summary, the social system provides the people-oriented base for Lean 4.0. Continuous training builds an adaptable workforce, while inclusive collaboration channels harness collective intelligence. These LSPs foster trust, engagement, and a shared commitment to change. Participants made clear that these social practices do not sit alongside technology adoption as separate efforts. Instead, they enable the technical system by making employees more receptive to I4Ts and more capable of using them effectively. As one participant observed, without a Lean improvement culture, even advanced technologies risk being underutilised (P7). Thus, the social system functions as the critical enabler for successful technology adoption within digital transformation.

4.2. Technical Systems

The second system, technical systems, comprises the digital technologies and infrastructure that organisations implement as part of their Lean 4.0 journey. Participants reported deploying a wide range of I4Ts, often in combination, with the explicit aim of supporting and strengthening Lean practices. Common technologies included Internet-of-Things sensors, cloud computing platforms, big data analytics, artificial intelligence and machine learning, automation and robotics, and emerging tools such as virtual and augmented reality. In many cases, organisations did not adopt one or two technologies in isolation. Instead, they built an integrated digital ecosystem. One participant summarised their technology stack as follows: “The main 4.0 technologies currently being used at our business are Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, automation and robotics, cloud computing, big data analytics, digital twins, cybersecurity solutions, and additive manufacturing” (P2). This breadth indicates that Lean oriented transformation relies on multiple digital capabilities spanning connectivity, analytics, automation, and security. Even organisations that described themselves as early in transformation had at least basic digital tools in place, such as cloud platforms or analytics, showing that technical adoption was evident across all participants.

Crucially, technical systems were not treated as ends in themselves but as enablers of Lean objectives. Participants consistently described technology integration as a way to eliminate waste, improve flow, strengthen quality control, and support data-driven decision making, all central Lean goals [

42]. Digital technologies were used to streamline tasks that previously relied on manual effort and fragmented information. One manager explained: “

By integrating 4.0 technologies such as AI and cloud computing in our workflow, the small and less meaningful tasks do not have to waste man hours and resources, allowing my team to focus on important tasks at hand” (P12). This illustrates how automation and data systems absorb routine non-value-adding work, freeing employees to focus on higher value activities such as problem solving, innovation, and customer service. Another participant observed that these technologies “

enable better communication, collaboration, and data-driven decision making” (P2). Cloud platforms, dashboards, and collaboration applications increased information visibility and speed of feedback. Teams could access up to date data from sensors and enterprise systems, enabling faster and more accurate decisions. This aligns with Lean’s emphasis on visual management and fast feedback loops, now intensified by digital connectivity. Several participants noted that IoT and analytics allow them to “

quickly and efficiently identify any issues and fix them promptly while prompting the proper group” (P1), supporting early problem detection and continuous improvement cycles.

Participants also viewed technical and social systems as tightly interdependent. Many explained that their Lean culture guided which technologies were selected and how they were applied. For example, one participant stated that technology was implemented only when it was “tracked and backed by metrics” to serve continuous improvement (P13). Conversely, technical systems reinforced the social system by changing how people collaborate and experience work. Improved communication tools connected employees and external stakeholders more closely (P2, P10), while automation reduced tedious work and often lifted engagement (P2, P12). Overall, technical systems act as the engines that extend Lean through automation, connectivity, and analytics, making processes more precise, responsive, and agile. However, participants were clear that technology alone cannot drive digital transformation. Where organisations introduced new technologies without aligning them with Lean principles or preparing people, adoption was slower and systems were underused. Hence, social and technical systems must operate in tandem. Lean culture and capability enable meaningful use of technology, while technology amplifies Lean’s reach. This interaction sets the stage for the third system, work systems, where transformation becomes visible in everyday operations.

4.3. Work Systems

The third system, work systems, refers to the operational and process changes that occur when Lean practices and I4Ts jointly reshape how work is performed. Three broad domains emerged: internal operational processes, customer facing processes that shape customer experience, and business model level change. These domains are where social and technical systems converge to produce tangible transformation. One participant captured the scope of work system change by noting that transformation spanned “HR, Marketing, Logistics, Production, Purchasing, and Sales, we are now largely a paperless company” (P3). This demonstrates enterprise-wide redesign of workflows through digital Lean thinking, including the removal of paper-based waste and manual handoffs.

Many organisations prioritised operational process improvement through Lean 4.0. A common pattern was the use of I4Ts to streamline supply chain and production activities. One manager explained: “Some key areas include inventory management where we have implemented IoT and automation to streamline the processes” (P14). This shows how real-time tracking and automated handling strengthen classic Lean targets such as inventory control and flow. Another participant described predictive analytics for maintenance (P3), reducing downtime by anticipating issues, consistent with Lean preventive maintenance goals but enabled by more accurate data. Several participants also reported experimenting with artificial intelligence in scheduling and production decision making (P12, P15). Collectively, these examples show that operational work systems were being redesigned so that Lean goals, waste reduction, flow, and quality, were delivered through digital capability rather than replaced by it.

Customer experience was another key work-system domain. Participants described digitalising marketing, sales, and service in ways aligned with Lean’s focus on customer value. One participant noted: “The marketing area is clearly expanding and digitally transforming, as all of our customers’ information is harnessed and used to the fullest for processes that were previously unexplored” (P5). Customer data analytics enabled more tailored value delivery, reflecting a fusion of digital insight and Lean value orientation. Another participant highlighted customer support transformation: “Right now, the big focus is on AI and customer support channels” (P10). Digital self service and chatbot systems reduced waiting for customers and improved responsiveness, which participants linked directly to Lean service improvement. Several others described similar benefits in sales and service through automation and analytics (P8, P9). Importantly, these changes were supported by LSPs such as customer involvement and feedback loops (P14), ensuring that digital solutions met real customer needs.

Business model transformations were less frequent but highly influential when present. These cases involved rethinking how value was created and delivered, enabled by digital capability. Participants reported shifts towards data-driven strategic planning (P4), redesigned governance to support agility across the enterprise (P11), and new digitally enabled product service models. One participant described scenario-based digital simulations to support investor decision making (P7), signalling a move from static planning to dynamic, data-informed strategy. While not all organisations pursued business-model change, those that did treated Lean 4.0 as a catalyst to question entrenched routines, integrate systems across functions, and eliminate siloed work.

Across all work system domains, a consistent pattern emerged. Social systems enabled technical adoption, and together these systems produced practical change in operations and customer experience. Many participants described this as a reinforcing cycle. A senior manager captured the shared view that Lean gives direction to technology, and technology strengthens Lean, lifting overall effectiveness (reflecting sentiments across P5, P7, P12). This synergy accelerated improvement by making processes more agile (P11) and by providing faster digital feedback for iterative refinement. Participants noted that Lean thinking helped them identify where I4Ts would add the most value, while the new data and automation opened additional Lean opportunities that were previously difficult to pursue. The result is an integrated work system where people, process, and technology evolve together. Participants also stressed that this alignment required deliberate change management and gradual process adjustment. Where alignment was achieved, organisations reported substantial benefits that flow into the final system of the framework, performance outcomes.

4.4. Outcomes

The fourth system, outcomes, captures the results and impacts observed when LSPs are integrated with I4Ts. When social, technical, and work systems were well aligned, participants reported multidimensional performance improvements. On the operational side, organisations experienced higher efficiency, productivity, and quality. One manager noted that “quality improved and shipping times shortened, leading to happier customers and repeat sales” (P5). This illustrates a chain effect: Lean 4.0 initiatives reduced defects and delays inside the organisation, which in turn lifted customer satisfaction and loyalty. Many participants similarly described faster throughput, less waste, and shorter cycle times. One reported that efficiency had risen above competitors and that employee turnover had fallen, indicating stronger engagement and retention (P3).

Improved employee engagement and productivity was a recurring theme. As routine work was automated and employees were more involved in improvement activities, participants felt their work became more meaningful. “Employee productivity and engagement improved as they spend time on meaningful work” (P2), linking the removal of repetitive tasks through automation and the empowerment provided by Lean to a more motivated workforce. This often created a reinforcing loop: engaged employees contributed more ideas and effort, further lifting quality and service.

Customer focused outcomes were also prominent. Beyond “happier customers” due to better quality and speed (P5), participants cited stronger relationships, higher satisfaction, and in some cases measurable business growth. Artificial intelligence-enabled customer support led to faster responses and improved perceived service levels (P10), while using customer feedback in development produced offerings that better matched client needs (P14). Some organisations reported higher satisfaction scores or increased sales. One participant stated simply that “sales have increased significantly”, attributing this to the combined effect of Lean 4.0 practices (P5). Faster delivery, better quality, and more tailored services were seen as sources of competitive advantage.

Financial and strategic outcomes flowed from these operational and customer gains. Reduced waste and improved efficiency lowered operating costs, while enhanced customer value and new digitally enabled offerings supported revenue growth. One participant highlighted a combined effect on “performance in terms of revenue and cash flow” (P1), while others pointed to higher profitability through productivity improvements (P7) and cost savings from automation. Overall, participants perceived that embedding I4Ts within a Lean transformation produced a stronger return on investment than either digital or Lean initiatives pursued in isolation.

However, outcomes were not uniformly positive or immediate. Some participants noted that major impacts had not yet materialised, particularly where initiatives were recent or still scaling. One respondent commented that “the collective impact of these factors on my company’s performance is not applicable” at present (P4), underscoring that digital transformation can have a delayed payoff. More commonly, participants described integration challenges that slowed or constrained results. Skill gaps, employee resistance, legacy systems and data quality issues, financial constraints, and cybersecurity risks were all cited. For example, one manager noted that adoption was slowed by a “lack of technical skills” in parts of the workforce (P9), while another observed that IoT and cloud solutions “expose us to greater IT security problems, and we are perfectly aware of this” (P3). These issues sometimes led to project delays, additional training rounds, or extra investment in infrastructure and security.

Despite these difficulties, nearly all participants viewed the hurdles as manageable with appropriate strategies such as targeted training, structured change management, and incremental implementation. No participant reported negative net outcomes from Lean 4.0. At worst, benefits were delayed or only partially realised; at best, organisations achieved substantial performance improvements. This reinforces a central insight: successful outcomes depend on navigating socio-technical challenges, not avoiding them. Organisations that proactively addressed human and technical barriers were better able to unlock the full potential of Lean 4.0, whereas those that neglected them experienced slower or more limited gains.

In summary, the outcomes system illustrates why integrating LSPs with I4Ts is valuable. It supports better operational performance, more satisfied customers, more engaged employees, and stronger financial results. These outcomes represent the end point of the main causal pathway: robust social systems enable effective technical systems, which reshape work systems and produce superior performance. At the same time, this pathway operates as a socio-technical loop. Improved outcomes, such as a more agile and high-performing organisation, feed back into the social system by raising morale and reinforcing a culture of success, and they encourage further investment in technical and work-system improvements. In this way, Lean 4.0 transformation tends to be continuous and iterative, echoing the continuous improvement philosophy that underpins it.

4.5. Synthesised Conceptual Framework

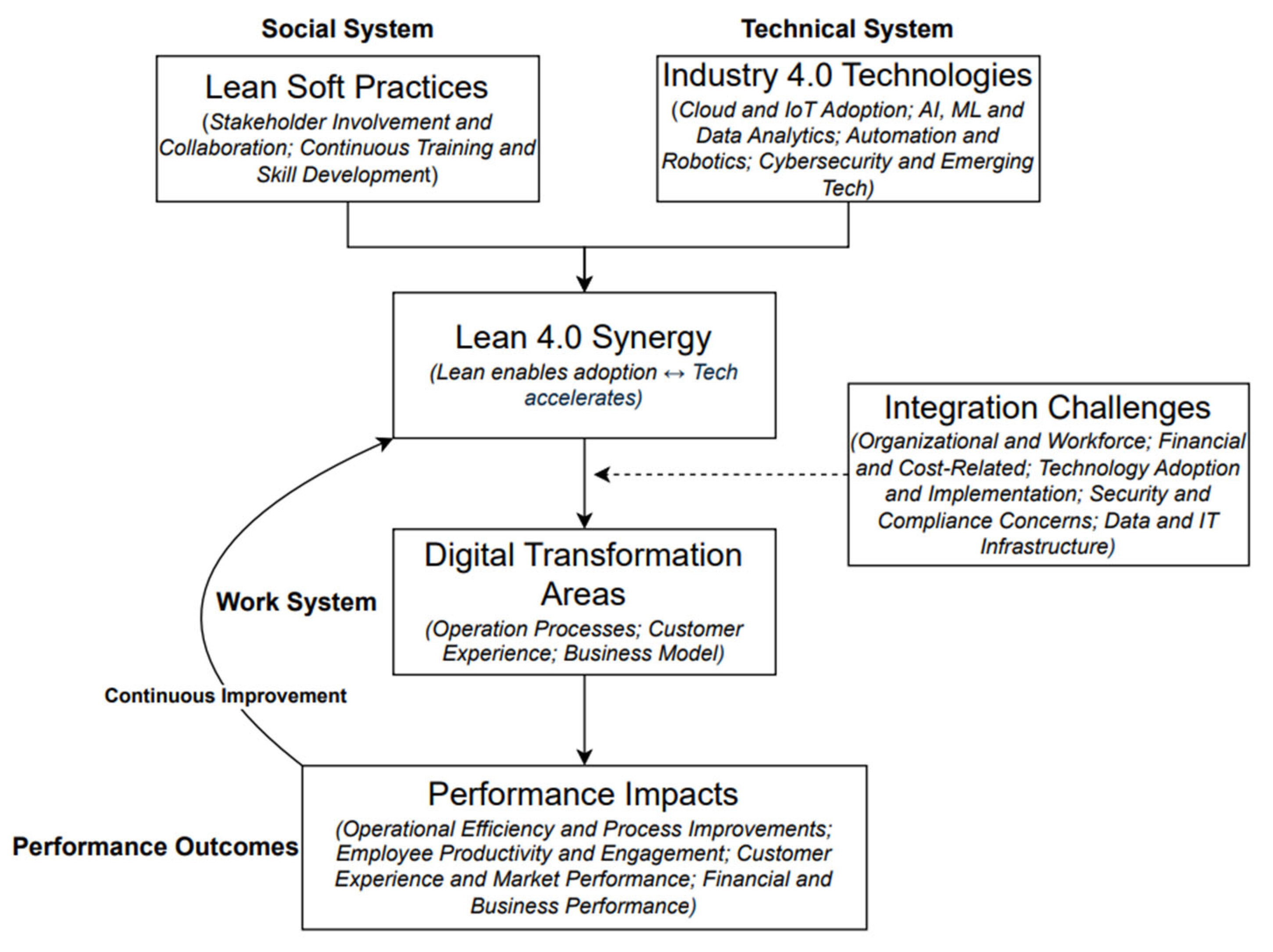

Building on the results, we synthesised a conceptual framework (see

Figure 1) that captures the relationships among the four core systems and explains how they collectively drive digital transformation success. The framework is grounded in our empirical findings and informed by socio-technical systems theory, which provides a foundational lens for understanding how human and technological factors interact within organisations. Socio-technical systems theory argues that organisations comprise two interdependent subsystems, social systems and technical systems, which interact within work systems to create value and produce performance outcomes [

43,

44]. Sustainable change requires joint optimisation of these subsystems, meaning neither can be designed or improved in isolation without compromising overall system performance [

45].

In the framework, these theoretical ideas are reflected across four components. The foundation consists of two enabler systems, the social system and the technical system, which emerged inductively from our thematic analysis of participant responses. The social system captures LSPs such as continuous training, employee empowerment, and stakeholder collaboration. These practices build a culture of continuous improvement and adaptability, ensuring that people are capable of engaging with new technologies and willing to change established routines. In parallel, the technical system comprises I4Ts including IoT adoption, artificial intelligence and analytics, cloud platforms, and automation. These technologies provide the digital capability required for transformation. Our analysis showed that neither subsystem is sufficient on its own. Digital transformation becomes sustainable only when social and technical systems are integrated.

At the centre of the framework is this Lean 4.0 synergy. It represents a bidirectional relationship in which LSPs enable adoption and effective use of I4Ts, while I4Ts amplify and accelerate Lean practices. Participants described how a strong continuous improvement mindset guided technology deployment, ensuring that digital tools were adopted for clear value creation, and how real time data and analytics accelerated decision making and improvement cycles. This reciprocal dynamic reflects the mutual adjustment principle central to socio-technical systems theory.

As the social and technical systems interact, they transform the work system. Work systems represent the operational domains where integration becomes tangible through redesigned tasks, processes, and ways of working. Three areas of work system transformation emerged from the data: operational processes, customer experience, and business models. These are the domains in which LSPs and I4Ts converge to reshape how value is created and delivered.

The framework also incorporates integration challenges that moderate or slow the interaction between social and technical systems. Consistent with participant accounts, these challenges include workforce resistance, skill gaps, financial constraints, legacy infrastructure issues, and security and privacy concerns. Socio-technical systems theory highlights that redesign must anticipate human and organisational barriers alongside technological ones. Participants emphasised that proactive change management and targeted investment are necessary to overcome these obstacles and sustain transformation momentum.

When enablers are aligned and challenges are managed effectively, the system progresses towards performance outcomes. These outcomes include improved operational efficiency and quality, higher customer satisfaction, stronger employee engagement, and better financial performance. Importantly, outcomes are not treated as an endpoint. Instead, they create a continuous improvement feedback loop. Positive outcomes reinforce Lean culture, justify further technology adoption, and enable subsequent cycles of digital transformation, supporting higher maturity over time.

Overall, the framework presents Lean 4.0 integration as a socio-technical systems process. It demonstrates that LSPs and I4Ts must evolve together, generating reinforcing changes in work systems that deliver sustainable performance gains. The framework therefore contributes both a theory grounded explanation of digital transformation success and a practical roadmap for aligning human and technological capabilities.

4.6. Cross-Case Configuration of Social, Technical, Work, and Outcome Systems

To complement the thematic results and the developed model, we conducted a cross-case synthesis that summarises how the social, technical, work, and outcome systems co-occur across the fifteen organisations. This synthesis is grounded in the coding structure reported earlier, particularly the Continuous Training and Skill Development and Stakeholder Involvement and Collaboration themes for the social system, the Adoption of Industry 4.0 Technologies and Lean Industry 4.0 Synergy in Transformation themes for the technical system, and the Digital Transformation Focus Areas theme, which distinguishes three work system domains: operational processes, customer experience, and business models. Performance impacts and integration challenges were drawn from the Performance Impacts and Integration Challenges themes within the outcomes system.

For each case, LSPs’ maturity in the social system was assessed as high, medium, or low based on the depth and regularity of training and the breadth of stakeholder involvement. Cases were rated high when they combined frequent, structured training with explicit and multidirectional involvement of employees, customers, and suppliers. Medium ratings reflect organisations with some regular training and stakeholder voice, but with fewer or less formalised mechanisms. Low ratings were assigned where training was limited and stakeholder involvement was weak or one sided. I4T adoption in the technical system was coded as basic, moderate, or high by combining the number of technologies (such as internet of things, cloud, analytics, artificial intelligence, automation, robotics, cybersecurity, and digital twins) with the extent to which these tools were described as embedded in daily work and digital transformation.

For the work system, we did not create a single overall score but instead evaluated digital transformation intensity separately in each of the three domains that emerged in

Section 4.3: internal operational processes, customer experience, and business model. Using the Digital Transformation Focus Areas codes, we rated transformation in each domain as limited (narrow, early, or support only changes), moderate (clear but focused changes within that domain), or extensive (broad or enterprise level redesign in that domain). For example, P3’s largely paperless operations across human resources, marketing, logistics, production, purchasing, and sales were coded as extensive transformation of operational processes and customer-facing activities, and as extensive business model digitalisation. P2’s combination of supply chain, manufacturing, and customer experience digitalisation was rated as extensive in operational processes and customer experience, but moderate at the business model level. Reported outcomes were then summarised as high, moderate, or limited, or not yet evident from the Performance Impacts codes, reflecting the breadth and strength of efficiency, quality, customer, employee, and financial improvements.

Table 3 shows a clear first cluster where both LSPs and I4Ts are high: P2, P3, P7, P9, P10, P13, and P14. In these organisations, the social and technical systems are both strong and tightly integrated. Operational processes are extensive in four of the seven cases (P2, P3, P13, P14) and moderate in the others (P7, P9, P10). Where customer experience is a strategic focus, digital transformation is extensive (P2, P3) or moderate (P9, P10, P14). Business-model change ranges from extensive (P3) through moderate (P2, P7, P13) to limited (P9, P10, P14) when legacy structures still constrain deeper redesign. Outcomes are high in six of the seven cases (P2, P3, P7, P9, P13, P14), with multidimensional gains across operational, customer, employee, and financial indicators. P10 illustrates an important nuance. It has high LSPs and high I4Ts with moderate digital transformation in operational processes and customer experience but only moderate outcomes, which is consistent with its description as still building skills and working through implementation challenges. Overall, this cluster confirms the main result of the qualitative analysis: when both the social system and the technical system are strong, digital transformation spreads across core work domains and tends to deliver broad performance benefits, with the depth of business-model change depending on structural constraints and strategic intent.

A second cluster comprises cases with high LSPs but only moderate I4T adoption (P5 and P12). Here, the people side is well developed, but the digital portfolio is narrower. Digital transformation in operational processes is moderate in both organisations, reflecting targeted use of I4Ts to improve internal efficiency and remove routine work rather than full redesign. The way this plays out in the work system differs. P5 combines moderate change in operational processes with extensive digital transformation in customer experience through data-driven marketing and real-time insight, while keeping the business model largely unchanged. P12 concentrates on streamlining internal tasks, with limited change in customer experience and business model. Outcomes are high in P5, which already reports improved quality, faster delivery, and higher sales and repeat purchases, and moderate in P12, where gains are framed mainly in terms of productivity and better allocation of effort. These cases show that high LSPs can still generate strong results with a moderate technical base, especially when digital transformation is focused on a clear value area such as customer experience. At the same time, the moderate I4T level naturally limits the breadth of transformation and the ceiling on outcomes.

A third configuration involves medium LSPs and between basic and moderate I4T adoption, which includes P1, P4, P6, P8, and P11. Here, the social and technical systems are present but less mature and less systematically connected. The pattern across the work system is more selective. P1, P6, and P8 are moderate in operational processes, with moderate or limited change in customer experience and limited change in business model. P4 and P11 show limited digital transformation across all three domains, with activity mainly confined to engineering or information technology management rather than organisation-wide redesign. Reported outcomes in this group are moderate in four cases and limited or not yet evident in one case. Improvements tend to be confined to particular indicators such as revenue and cash flow, sales and supplier costs, or agility, rather than the broader pattern seen in the high-LSP high-I4T cluster. This aligns with the qualitative themes. When training and involvement are present but only medium in strength, and when I4Ts are deployed in a more incremental way, the interaction between social and technical systems supports local improvements but rarely triggers extensive reconfiguration of operational processes, customer experience, or business models.

P15, which has low LSPs and moderate I4Ts, illustrates how weak social foundations constrain what a relatively capable technical system can achieve. The organisation has already used I4Ts to reach moderate levels of digital transformation in operational processes and the business model, yet customer experience remains only limited in terms of digital transformation. Outcomes are moderate rather than high and are explicitly reported as being delayed by policy rules and weak internal capability. In this case, technology is present and pointed at an existing digital platform, but limited training and involvement, together with organisational constraints, slow the pace at which employees can absorb and exploit I4Ts and restrict how far customer facing and strategic aspects of the work system can change.

Across

Table 3 the pattern is consistent with the conceptual model developed earlier. As LSPs and I4Ts move from low or medium to high, digital transformation in operational processes becomes moderate or extensive rather than limited. Where organisations also choose to focus on customer experience, strong LSPs and strong I4Ts support moderate or extensive redesign of customer facing processes. Business-model change is more contingent on legacy conditions and strategic choice, but it is most visible in cases that already have high LSPs and high I4Ts. The outcome column follows the same gradient. High LSPs and high I4Ts are almost always associated with high and multidimensional performance improvements, while medium configurations yield mainly moderate results and low LSPs holds back the value that can be created from a moderate I4T base. This cross-case configuration therefore reinforces the central argument of the paper. Lean 4.0 delivers its strongest impact when LSPs and I4Ts are developed together as one socio-technical system that reshapes operational processes, customer experience, and, where possible, business models, rather than being pursued as separate people and technology initiatives.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

Lean 4.0 is defined in the literature as the integration of Lean practices and I4Ts [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

46,

47]. Building on this established work, our study makes several contributions that clarify how Lean 4.0 operates and where LSPs fit within it. We extend this stream of research by explaining how and why the integration of Lean practices and I4Ts succeeds or fails, rather than only showing that it improves operational performance [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

13,

46,

47]. Using a socio-technical systems lens, we conceptualise LSPs as the social subsystem of Lean 4.0 and bring together prior work on LSPs and human-centred Lean capabilities within an explicit socio-technical framework [

3,

5,

6,

14,

34]. This builds directly on specialised LSP studies and shifts the focus from reporting performance outcomes to unpacking the mechanisms and interactions that generate those outcomes.

Our central theoretical contribution is an empirically grounded socio-technical framework for Lean 4.0 integration (

Figure 1). Unlike existing Lean 4.0 frameworks that are primarily conceptual [

7,

9] or that focus on operational metrics [

13,

27], our framework maps the dynamic interplay of four interdependent subsystems—social practices, technical tools, work processes, and performance outcomes—derived inductively from practitioner experiences. It conceptualises digital transformation as the co-evolution of human-centred Lean practices and digital technologies within work systems, showing that optimal results emerge when social and technical systems are jointly aligned. The cross-case synthesis in

Section 4.6 and

Table 3 provides empirical support for this proposition, showing that organisations with high LSP maturity and high I4T adoption exhibit the most extensive digital transformation and strongest multidimensional performance outcomes, whereas medium or unbalanced configurations are associated with more limited change. This evidence-based insight extends classic socio-technical systems theory [

40,

41] into the context of contemporary digital transformation and offers an integrated lens for future Lean 4.0 research that moves beyond treating Lean and digital initiatives as separate variables in performance equations.

First, our findings strongly support a complementary relationship between Lean and I4Ts, reinforcing recent arguments that they are mutually reinforcing strategies rather than competing initiatives [

48]. We move beyond debates about whether Lean and I4Ts substitute or complement one another by showing, in depth, how and why they amplify each other in practice. Participant accounts indicated that a Lean culture within the social system strengthens technology adoption, while I4Ts within the technical system accelerate Lean outcomes. This aligns with socio-technical systems theory, which holds that performance improves when social and technical elements co-evolve. Without a continuous improvement mindset, participants noted new technologies would be underused, echoing the view that I4Ts are most effective in organisations already grounded in Lean thinking [

48]. Conversely, participants described I4Ts automating wasteful tasks and generating real-time data that speed up problem solving and learning, supporting propositions that digitalisation strengthens Lean principles such as just in time and kaizen [

49]. Our qualitative evidence therefore validates and enriches prior quantitative findings [

50] by illustrating the bidirectional Lean and technology synergy with concrete mechanisms, adding nuance to Lean 4.0 as a socio-technical systems configuration of complementary practices.

Second, we highlight the critical role of LSPs as drivers of digital transformation within work systems, with I4Ts acting as powerful enablers. This extends Lean management theory into the digital era by showing that transformation success depends not only on technology but also on the human and organisational foundations that allow technology to be used effectively. LSPs such as leadership support, training, and stakeholder engagement are long recognised as central to Lean success [

3,

47]. Our findings show these same practices initiate and sustain digital transformation by fostering adaptability, problem solving capability, and cultural openness to change. The prominence of stakeholder involvement in our results illustrates that engaging employees, customers, and suppliers is not only a Lean best practice but also pivotal for successful digital adoption, consistent with research showing that digital maturity is shaped more by cultural readiness and continuous learning than by technology alone [

1,

2]. Organisations that invested in training, empowerment, and inclusive decision making were better able to leverage advanced technologies. In effect, Lean’s human-centred practices create the conditions for effective I4T implementation, while I4Ts amplify these practices by strengthening data-driven decisions, automating routine work, and accelerating continuous improvement cycles. This supports the argument that Lean and I4Ts together generate a combined effect that exceeds their independent contributions [

51].

Third, our study sheds new light on the challenges of integrating Lean and digital initiatives, bridging two strands of literature that are often treated separately. Barriers such as skill gaps, resistance to change, legacy system constraints, and security concerns have been noted in Lean transformations and in digital transformation individually. Our evidence shows that when these domains combine in Lean 4.0, challenges are often intensified because organisations must overcome people, process, and technology barriers simultaneously. Theoretically, this reinforces a socio-technical systems view that successful Lean 4.0 integration requires addressing technical issues such as systems integration, data quality, and cybersecurity together with social issues such as culture, training, and change resistance. Solving one side without the other is insufficient, consistent with socio-technical systems theory’s emphasis on joint optimisation.

Fourth, we provide empirical support for the performance outcomes of Lean and I4T integration, showing that combining Lean and digital initiatives yields synergistic benefits. Lean research has long documented positive impacts on operational and financial performance [

3,

4], while emerging studies show I4T adoption enhances productivity and innovation. Our findings suggest that Lean 4.0 produces compounded benefits across operational, customer, employee, and financial dimensions. This aligns with evidence that Lean and digital practices together have a stronger effect on performance than either alone, particularly when LSPs are present [

52]. We add qualitative depth by outlining mechanisms, including automation reducing waste and improving delivery reliability, and employee involvement in technology-driven change lifting morale and productivity, which then improves service quality. These patterns point to likely mediators, such as employee engagement linking technology adoption to outcomes, and reinforce that Lean 4.0 success rests on system wide interaction rather than isolated interventions.

Fifth, our research advances understanding of continuous improvement in the digital era. Lean’s philosophy of kaizen is traditionally people driven [

53]. Our findings indicate that I4Ts can accelerate and broaden continuous improvement without weakening its human-centred foundation. Participants described real-time operational data and artificial intelligence shortening Plan Do Check Act cycles, enabling teams to detect and respond to problems faster, consistent with emerging ideas of digitally enabled kaizen [

54]. High employee involvement remained essential, and digital platforms expanded participation by enabling more voices to contribute improvement ideas. This counters concerns that automation diminishes the human role in improvement. Instead, our evidence supports an augmentation perspective where technology strengthens human problem-solving capacity [

54]. Employees are freed from repetitive tasks and can focus on creative, value adding work supported by richer data.

Overall, these contributions portray digital transformation as a socio-technical, continuous improvement journey. We extend Lean theory by demonstrating that its principles are compatible with I4Ts and can evolve through them, and we enrich digital transformation theory by stressing the decisive role of social systems in realising technology’s benefits. The resulting framework clarifies how social, technical, work, and outcome systems interconnect and reinforce one another, providing a foundation for both scholars and practitioners to better analyse and guide Lean 4.0 transformations.

5.2. Managerial Contributions

For practitioners, this study shows that a successful Lean 4.0 transformation is an integrated socio-technical change, not a technology project on its own. Focusing on people and processes is as important as focusing on technology in any digital transformation. Managers planning to implement I4Ts should invest equally in LSPs and cultural readiness. Practically, this involves engaging employees early and consistently, forming cross-functional teams to lead the transformation, seeking customer and supplier input on digital initiatives, and building structured training programs to continuously upskill staff. Organisations that did this achieved stronger efficiency and quality gains and experienced smoother rollouts of new technologies. By contrast, where the people side was neglected, participants reported delays, resistance, and underused systems. One participant cautioned that without the soft practices, advanced technologies would likely be underutilised, a point echoed across multiple accounts. The clear lesson is that technology investments must be matched with investment in training, empowerment, communication, and continuous process improvement, or I4Ts will not deliver their promised value. In short, strengthening the social system is a prerequisite for extracting value from the technical system.

Second, practitioners should treat Lean and I4Ts as mutually reinforcing strategies rather than separate initiatives. The practical question is not Lean first or digital first, but how to implement both together. When introducing a new technology, managers should apply Lean thinking to simplify and streamline the underlying process so that technology adds value rather than automating waste. Likewise, during Lean improvement projects, managers should consider whether digital tools could solve problems that were previously difficult to address, such as using IoT sensors where manual measurement is unreliable. Treating Lean and digital initiatives as one program prevents siloed efforts, for example an IT driven project that operations do not own, or a process redesign that ignores available digital capability. Participants described successful cases where shared goals across functions enabled enterprise wide change, including paperless workflows and integrated systems. Managers should therefore encourage active collaboration between IT and operational teams under common transformation priorities. Early wins in either domain then reinforce the other, creating momentum for ongoing improvement.

Third, managers need to anticipate and address integration challenges early. Skill gaps should be identified up front, with plans for ongoing training, targeted hiring, or external partnerships where needed. Training must be continuous, not a one off event, because technologies and required competencies evolve over time. Some organisations may need new hybrid roles, such as operational data analytics leads, or mentorship arrangements to build internal capability. Change resistance also requires deliberate management through clear communication and genuine involvement. Employees are more receptive when they understand why the change matters and when technologies are presented as tools that remove drudgery and support better work, not as threats. Recognising employee contributions to digital improvements and equipping middle managers to act as change champions strengthens buy in across levels.

On the technical side, data and systems integration should be planned carefully. Integrating I4Ts with legacy infrastructure often requires phased upgrades, strong IT support, and clear data governance to protect data quality and accessibility. Participants’ experiences suggest a modular rollout works best: stabilise and embed one system or pilot before scaling further, rather than deploying many technologies at once. Cybersecurity and compliance must also be built in from the start, because greater connectivity increases exposure to risk. Security controls, monitoring, and staff awareness should be treated as part of normal operations, not an afterthought.

Finally, financial sustainability matters. Some organisations struggled to justify expensive technologies with long payback periods. Lean logic provides a useful discipline here: every digital initiative should be tied to a specific value driver or waste reduction target, rather than adopted for novelty. Small pilots can demonstrate tangible benefits and return on investment, building the evidence needed for broader rollout and preventing digital waste [

14].

Overall, the practical message is straightforward. Lean 4.0 succeeds when organisations balance development of their social system with deployment of their technical system, and actively manage the interaction between them through integrated planning, capability building, and careful sequencing. Managers should adopt a holistic mindset that advances human capability and organisational readiness alongside technological progress.

6. Conclusions

This research set out to examine how LSPs interface with I4Ts to drive digital transformation and improve organisational performance. Through an in-depth qualitative analysis of fifteen open-ended online questionnaire responses across diverse industries, we found that successful Lean 4.0 transformations depend on an integrated systems approach. Rather than treating technology as a silver bullet, the findings confirm that human-centred Lean practices and advanced digital technologies must function together. We first identified seven themes, which were consolidated into four overarching systems, social, technical, work, and outcomes. These systems depict a clear pathway: Lean-oriented social systems enable effective technical system adoption; together, they reshape work systems through digital transformation; and this integration produces stronger performance outcomes.

In practical terms, LSPs such as training, employee engagement, and stakeholder collaboration provide the cultural foundation and skill base that allow organisations to adopt and leverage I4Ts effectively. I4Ts then act as enablers that accelerate and amplify Lean initiatives, from streamlining processes through automation to improving decision-making through real-time data. When combined well, Lean practices and digital technologies create a synergistic Lean 4.0 dynamic that lifts efficiency, agility, and innovation. Across our sample, organisations adopted multiple I4Ts alongside Lean methods rather than in isolation. Their transformation efforts targeted core work systems including internal operations, customer experience, and business model renewal, showing that Lean 4.0 applies beyond the factory floor to enterprise-wide strategy and value delivery.

At the same time, integration is not without challenges. Skill and mindset gaps, resistance to change, legacy system constraints, and security or privacy concerns can slow progress if not addressed. This reinforces the importance of proactive change management, continuous upskilling, and infrastructure investment. Organisations that anticipated and managed these barriers implemented Lean 4.0 more smoothly, whereas those that neglected the people and process side often experienced delays or limited value. Yet where social and technical systems aligned and challenges were overcome, integration produced multidimensional gains, including faster and more flexible processes, higher quality outputs, improved customer satisfaction and loyalty, more empowered and productive employees, and stronger financial results. These outcomes indicate that Lean 4.0, when executed effectively, can materially strengthen competitive position. The cross-case configuration summarised in

Table 3 is consistent with this conclusion, as cases that combine high LSP and high I4T adoption report broader transformation of work systems and stronger improvements in efficiency, customer outcomes, employee engagement, and financial performance than cases with medium or low levels of either dimension.

These contributions should be considered alongside several limitations. First, the study relies on written, self-administered responses from a Prolific panel rather than live interviews. Although this approach reduced interviewer bias and enabled reflective answers, it limited opportunities for probing and may have constrained depth in some accounts. Second, the purposive sample is small, consisting of fifteen experienced professionals involved in continuous improvement or digital transformation. This supports theoretical insight but limits statistical generalisation across all contexts. Future research should therefore build on our framework using larger samples and sector-specific or multi-firm designs to examine whether the socio-technical patterns identified here generalise across broader and more diversified organisational populations. Third, data are subjective and cross sectional. We did not triangulate reported performance improvements with objective indicators, so optimism bias is possible, and we cannot observe whether gains persist over time. Fourth, while the study focused on LSPs, we did not systematically measure Lean maturity or the full range of hard Lean tools in each organisation, so configurations cannot be linked precisely to specific toolsets. Fifth, online panel research introduces constraints. Despite Prolific quality controls and strict inclusion criteria, we could not compute a conventional response rate, and we rely on platform safeguards to prevent inauthentic responses.

These limitations suggest directions for future work. Quantitative studies could operationalise the four subsystems and test how specific bundles of LSPs and I4Ts, and specific integration challenges, mediate or moderate the link between digital transformation and performance. Longitudinal and sector-specific research could track Lean 4.0 initiatives over time to examine how socio-technical configurations evolve and whether early gains are sustained. Future qualitative research could also incorporate multiple stakeholder perspectives within the same organisation, including managers, frontline staff, and technical specialists, to deepen understanding of lived Lean 4.0 experiences. Finally, there is scope to connect Lean 4.0 configurations to broader societal outcomes such as job quality, inclusion, and sustainability, extending analysis beyond organisational performance to implications for work and society. These questions align closely with the emerging Industry 5.0 agenda, which emphasises human-centric, sustainable, and resilient production systems, including circular-economy principles and quality of life for workers and communities. Future research could therefore use our socio-technical Lean 4.0 framework as a starting point to theorise and empirically examine how combinations of LSPs and I4Ts contribute not only to efficiency and financial performance but also to Industry 5.0 goals such as environmental performance, resource circularity, and employee well-being.