Abstract

In the evolving discourse of affective urbanism, emotions are increasingly recognized as fundamental, systemic drivers shaping the social, perceptual, and symbolic dimensions of urban space. Meanwhile, advances in visual technologies and media aesthetics have transformed contemporary cities into visually saturated environments, where visual cues actively influence how urban space is perceived, navigated, and emotionally experienced. While prior research has addressed affective belonging and spatial identity, these studies often treat emotion and visual design as separate influences rather than examining their interdependent, systemic roles. To address this gap, this study develops an emotion-driven systemic model to analyze how visual design activates affective pathways that contribute to the sustainable construction of place branding. Drawing on survey data from 134 residents in Wuxi, China, we employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to examine the interrelations among emotionally durable visual design, urban emotion, and place branding. The results reveal that visual attachment design (VAD) significantly strengthens place branding through emotional mediation, while visual behavior design (VBD) directly enhances sustainable branding by fostering participatory engagement even without emotional mediation. In contrast, visual function design (VFD) demonstrates limited impact, underscoring its insufficiency as a stand-alone strategy. These findings underscore the value of modeling emotionally durable visual communication as a system that links emotion, behavior, and identity in citizen-centered place branding.

1. Introduction

In the evolving landscape of affective urbanism, growing attention has been focused on the integration of citizens’ feelings and experiences into the construction of place image and identity [1,2]. Scholars emphasize that cities are not only physical infrastructures but also emotional terrains, continuously shaped by affective dynamics [3,4]. Within this framework, urban emotion functions as a systemic construct mediating the interaction between individual perception and the symbolic, sensory, and experiential meanings of place. The rising influence of affective urbanism in emotionally informed place branding research is evident in calls to examine the interrelated affective, perceptual, and symbolic systems that shape urban identity [5,6]. More recently, urban emotion has also been conceptualized as a dynamic process that requires emotional continuity and long-term citizen engagement to sustain the development of urban brands [7,8].

At the same time, cities are increasingly saturated with visual technologies such as urban screens, data-driven interfaces, architectural graphics, and brand imagery [9]. This proliferation positions visual communication as a central mediator of spatial experience [10]. From urban screens to place-based branding imagery, visual design shapes how people perceive, interpret, and emotionally engage with urban environments [11], and constructs symbolic meaning in spatial experience [12]. The proliferation of digital visual interfaces and data-driven design aesthetics has intensified the role of visual cues in structuring not only what citizens see, but how they feel and interact with the city [13]. Taken together, these developments suggest that visual design is no longer limited to aesthetic expression; it increasingly operates as a form of emotional design, shaping the durability of citizens’ engagement and transforming everyday interactions into lasting forms of brand attachment.

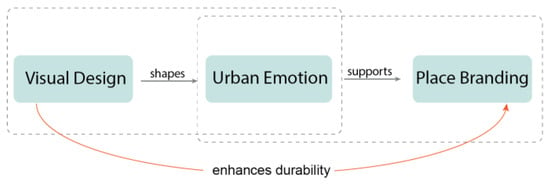

Despite increasing recognition that visual design plays a role in shaping place experience through emotional engagement, existing research has not fully explained how emotional design contribute to the formation and sustainability of place branding. As shown in Figure 1, prior studies often treat visual stimuli and emotional responses separately (indicated by the dashed box), focusing primarily on short-term recognition or symbolic differentiation, while neglecting their systemic integration. The red pathway highlighted in the figure points to an underexplored domain: how emotional and behavioral systems interact through design to support enduring urban identity and brand resilience.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Research.

To address this gap, this study proposes an emotion-driven systemic model of emotionally durable visual design [14]. In contrast to short-lived aesthetic stimulation or attention-driven design tactics, emotionally durable visual communication focuses on cultivating enduring affective bonds between citizens and urban spaces. This approach frames visual design not merely as representational, but as an integral part of an emergent affective system that supports emotional sustainability, social inclusivity, and cultural resonance in urban environments.

This paper employs Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) on survey data from 134 residents in Wuxi, China, to examine the interrelations among visual design, urban emotion, and place branding. The findings reveal the affective and symbolic mechanisms through which visual cues influence citizens’ emotional connections with place. This research contributes by developing an emotion-driven systemic framework that embeds emotionally durable visual communication within sustainable place branding.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Urban Emotion and Affective Urbanism

Emotions have emerged as key factors influencing how urban environments are experienced and how urban identities are formed [2,15]. Rather than viewing emotions as private or internal phenomena, contemporary research recognizes them as socially embedded and spatially situated. Davidson and Milligan [16] highlight the relational nature of emotions, arguing that our feelings are inseparable from the spatial and social environments in which we live. Similarly, Williams [17] emphasizes that the emotional structure of a city should be regarded as a collective social experience rather than an individual one. Within this framework, urban emotion emerges as a form of place-based collective affect, which constitutes a shared emotional infrastructure that actively contributes to the symbolic meaning and social construction of place.

Urban emotion offers a systemic lens to understand how people connect affectively with their environments. This concept has been interpreted and developed by various scholars, including Jackson, who described “sense of place” as an amalgamation of beliefs, values, and attitudes [18] that collectively forge an individual’s connection to a particular space [19]. Advancing this concept, subsequent research models in which place identity and place attachment jointly influence civic engagement and spatial behavior [20]. Place identity refers to the cognitive and symbolic connection individuals establish with a particular location, shaped by perceptions, memories, and shared meanings. Place attachment refers to the affective dimension of human–place relations, expressed through belonging, loyalty, and satisfaction, and rooted in everyday interactions [21]. Recent work highlights that citizens’ place attachment is key to sustainable urban development [22]. To complete this framework, the concept of place behavior has been introduced as a critical intermediary that bridges identity and attachment [23], showing that citizens’ engagement is vital not only for accepting place brands but also for actively supporting and sustaining them [24,25].

Building on the theoretical foundations of urban emotion outlined above, this study synthesizes prior perspectives by conceptualizing urban emotion as a triadic construct comprising place identity, place behavior, and place attachment. These dimensions are interrelated and sequential: recognition and meaning (identity) activate affective behaviors (behavior), which in turn reinforce and solidify emotional bonds (attachment). From a systemic standpoint, this triadic framework provides a theoretical basis for understanding place branding as an interdependent, perception-driven system that dynamically responds to visual stimuli and sustains enduring affective engagement.

2.2. Emotionally Durable Visual Design in Urban Context

In contemporary urban development, visual design has become a central force in shaping the symbolic, perceptual, and affective layers of cities. No longer confined to traditional aesthetics, urban visuals now operate within a saturated media ecology, including digital signage, algorithmic imagery, interactive public screens [26]. These visual forms mediate how cities are perceived, experienced, and remembered, positioning visual communication as a strategic element of place branding. Urban visual design, in this sense, functions not only as a means of spatial representation but as an interface of social interaction and emotional resonance. Recent scholarship has emphasized that the visual culture of cities encompasses both representational imagery and performative media practices, embedding civic identity into everyday urban experience [27]. This convergence of technological mediation and symbolic communication situates visual design as a key infrastructure of affective placemaking.

While prior research has acknowledged the emotional effects of visual design in place-related contexts [28], limited attention has been given to how emotion functions as a systemic component within the design process itself. Addressing this gap, the present study adopts the framework of Emotionally Durable Visual Design (EDVD), which was originally proposed in the context of design sustainability [29]. This framework identifies six dimensions—Functionality, Enjoyment, Interaction, Narrativity, Symbolism, and Innovation—that represent distinct pathways through which visual design can activate and sustain emotional engagement in urban contexts. Specifically, Functionality refers to the capacity of visual design to provide practical recognition cues and reinforce place identity. Enjoyment captures the role of novelty and pleasure in shaping users’ affective impressions. Interaction emphasizes the design of participatory encounters that enhance personal engagement. Narrativity reflects the use of temporal references and memory cues to evoke nostalgia and historical consciousness. Symbolism focuses on the embedding of cultural and social values into visual signs, while Innovation points to the ability of design to introduce new meanings, rituals, or uses within the urban environment.

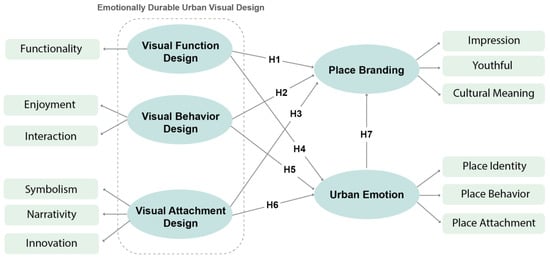

To adapt this framework to the urban visual context and prepare it for empirical analysis, Figure 2 illustrates how the six dimensions of EDVD are reorganized into three coherent design categories, collectively referred to as emotionally durable urban visual design. As shown in the figure: Visual Function Design (VFD) corresponds to place identity, emphasizing how the functional and recognizable aspects of visual communication help establish cognitive affiliation with urban imagery. Visual Behavior Design (VBD) corresponds to place behavior, focusing on how interactive visual elements stimulate audience engagement, behavioral response, and social participation. Visual Attachment Design (VAD) aligns with place attachment, aiming to elicit deeper emotional bonds and affective resonance toward the city through symbolic, narrative, or aesthetic cues.

Figure 2.

The Structure of Emotionally Durable Urban Visual Design.

2.3. The Structure of Sustainable Place Branding

Place branding refers to the strategic process by which cities and regions construct, communicate, and reinforce a recognizable identity to internal and external audiences [30]. In its early forms, place branding emphasized the creation of visual identifiers, such as logos, slogans, and standardized color schemes, which served to enhance visibility and facilitate differentiation in a competitive urban environment [31,32]. However, as cities increasingly compete not only for investment and tourism but also for talent and social capital, scholars have emphasized that visual differentiation alone is insufficient. Instead, branding strategies have shifted toward more integrated approaches that account for perception, experience, and meaning-making across cultural and social dimensions [33].

Within this evolving paradigm, the concept of sustainable place branding has received growing scholarly attention [34]. In contrast to conventional branding models that prioritize short-term visibility or promotional outcomes, sustainable place branding emphasizes the long-term continuity, adaptability, and socio-cultural relevance of a city’s identity. Its goal is to cultivate enduring bonds between people and place by foregrounding affective connections, cultural resonance, and participatory engagement [35]. This approach reframes place branding as a dynamic and complex system of co-construction, where symbolic representation and emotional investment interact continuously within broader social, cultural, and spatial networks.

Recent empirical research has contributed to refining the dimensions through which sustainable place branding can be operationalized. among these, impression and youthfulness have been recognized as essential constructs. impression refers to the immediate perceptual and cognitive responses generated by a city’s visual and spatial atmosphere, often serving as the initial trigger for deeper identification [36]. Youthfulness, as observed in recent studies, reflects the perception of vitality, creativity, and future-oriented openness, which contributes to a city’s capacity to project relevance and innovation in response to social and cultural change [37,38].

In addition to these dimensions, cultural meaning has emerged as a key component of sustainable branding. This concept encompasses the historical, symbolic, and identity-based associations that residents and visitors construct in relation to place [39]. These associations are informed by heritage, memory, and cultural narratives, and they serve to embed branding within the everyday lived experience of the public [40]. Cultural meaning thereby contributes not only to emotional depth but also to the continuity and resilience of brand identity across generations.

Taken together, impression, youthfulness, and cultural meaning form a connected system where these elements influence each other and work together to maintain place branding over time. This system operates through continuous feedback between people’s perceptions, feelings, and cultural associations, allowing the brand to adapt and stay relevant as social values and community needs change.

2.4. Research Model and Hypotheses

Building upon the theoretical framework of sustainable place branding, this study conceptualizes place branding as an emotion-driven system, in which emotionally durable visual design activates affective mechanisms that shape citizens’ perception and internalization of place branding. While previous studies have acknowledged the emotional effects of visual stimuli, the systemic role of emotion as an organizing force within the design process remains underexplored. Specifically, it is unclear how emotional design strategies coordinate cognitive, behavioral, and symbolic dimensions to support the long-term sustainability of place branding. To address this gap, this study develops an integrated framework that embeds visual communication and urban emotion into the systemic formation of sustainable place branding.

To operationalize this framework, Figure 3 presents the proposed research model. In the diagram, the ellipses represent the latent constructs (VFD, VBD, VAD, urban emotion, and place branding) while the rectangles denote the observed variables used to measure each construct. The model specifies seven hypothesized paths, illustrated by directional arrows, capturing the relationships among visual design, urban emotion, and place branding. This structure positions emotion not as a passive outcome but as a dynamic mediator that links perception, affect, and identity construction. By foregrounding emotional durability, the model demonstrates how visual design can sustain resilient and meaningful place brands over time.

Figure 3.

The Research Hypotheses Model.

Based on this framework, the study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H1.

Visual function design has a positive impact on urban emotion.

H2.

Visual behavior design has a positive impact on urban emotion.

H3.

Visual attachment design has a positive impact on urban emotion.

H4.

Visual function design has a positive impact on sustainable place branding.

H5.

Visual behavior design has a positive impact on sustainable place branding.

H6.

Visual attachment design has a positive impact on sustainable place branding.

H7.

Urban emotion has a positive impact on sustainable place branding.

3. Method

Formulating hypotheses based on existing literature regarding the potential relationships among various influencing factors marked the initiation of this phase, with a focus on understanding their interactions within a systemic framework. Subsequently, a questionnaire was meticulously designed and widely distributed to gather user evaluations of these interconnected factors. The final step involved employing Partial PLS-SEM analysis to corroborate and elucidate the structural relationships and dynamic interplay among the factors within the place branding system.

3.1. Data Collection

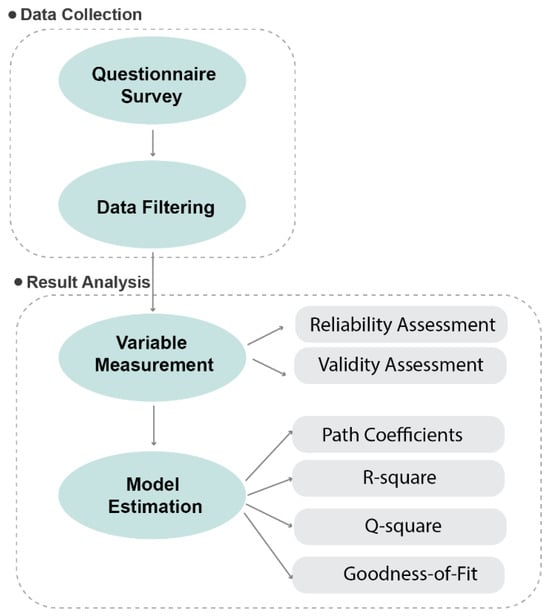

In the preliminary stage of our research (Figure 4), we conducted a comprehensive questionnaire survey targeting residents who had lived in urban environments for at least one year. The data collection focused on Wuxi, China—a medium-sized city on the eastern coast that combines rich cultural heritage with distinctive urban visual characteristics. Wuxi was chosen not only for its historical landmarks and scenic landscapes, but also because it represents a typical case of cities navigating the dual challenge of preserving cultural identity while pursuing contemporary place branding. In recent years, Wuxi has also become a focal point in national media culture, most notably serving as a sub-venue for the 2025 CCTV Spring Festival Gala. This event highlighted the city’s role in projecting visual imagery on a national scale, further underscoring its relevance as a representative case for studying the systemic interplay between visual design, urban emotion, and sustainable place branding.

Figure 4.

Research Process.

The questionnaire employed a 7-point Likert scale and targeted residents who had lived in Wuxi for at least one year, ensuring that participants were familiar with the city’s cultural and visual environment. Visitors and short-term residents were excluded to maintain consistency in respondents’ place-based experiences. The survey collected demographic information, including gender, age and professional field. During recruitment, attention was given to capturing diversity across different demographic groups. Although stratified sampling was not formally applied, efforts were made to ensure heterogeneity in age, occupation, and education to strengthen the representativeness of the sample.

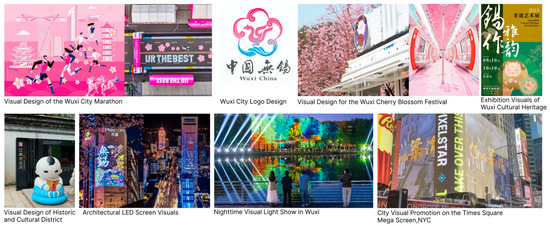

Considering that some participants might not be familiar with the concept of visual communication design in urban contexts, we conducted two rounds of pre-testing, each involving 10 participants, to refine the wording of the questionnaire. To ensure conceptual clarity and respondent comprehension, Figure 5 illustrates the final questionnaire design, which incorporated definitions and visual examples of urban visual communication. Each example was accompanied by a brief explanation to guide participants’ understanding.

Figure 5.

Visual Examples of Visual Communication Design in Wuxi.

All participants were adults (aged 18 and above) and voluntarily completed a structured questionnaire. Before completing the questionnaire, each participant received a written informed consent form, which explained the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and the measures taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. Consent was implied through the act of submitting the completed questionnaire. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University, approval number: JNU202409RB0042.

A total of 134 responses were collected, of which 122 valid cases were retained after excluding incomplete entries. As shown in Table 1, the final sample (N = 122) was gender-balanced, skewed toward younger residents (68.04% under 30), and primarily composed of students (42.62%), alongside diverse groups such as education and research professionals (17.21%), corporate employees (19.67%), and public sector staff (6.56%). This composition indicates that while the sample is not evenly distributed across all demographic categories, it maintains diversity across multiple social groups, thereby ensuring heterogeneity in perspectives and experiences within Wuxi’s resident population.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Sample.

3.2. Measures

In this study, five latent constructs were measured: VFD, VBD, VAD, Urban Emotion, and Place Branding. Each construct was operationalized through multiple observed indicators (measurement items), adapted or modified from established scales to fit the urban context and the research purpose of this study (Table 2). Constructs were measured on a seven-point scale (1 = very unlikely, 7 = highly likely). To ensure construct reliability and content validity, each latent variable was measured by 2 to 3 items, following common practice in structural equation modeling [41]. This multi-item approach allows for a more robust estimation of the latent constructs and improves the internal consistency of the measurement model.

Table 2.

The Measurements of Research Model.

3.3. Date Analysis

The data analysis proceeded through several steps. Initially, the reliability, as well as convergent and discriminant validities, were assessed, with descriptive results to be discussed subsequently. Following this, all hypotheses were tested, and the corresponding path coefficients were derived. In this study, we utilized the PLS-SEM algorithm within SmartPLS 4 software because this algorithm can tolerate smaller sample sizes [48]. We implemented a weighted path scheme with up to 3000 iterations using default initial weights. Furthermore, we performed a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples to assess the statistical significance of our PLS-SEM analysis results.

4. Results

In the following section, we present the results of our PLS-SEM analysis. We evaluated the reliability of the measurement model by assessing Cronbach’s α coefficient for all core variables. The validity of the structural model was examined using cross-loadings and the Fornell-Larcker criterion. Additionally, we assessed the overall model fit using key indicators such as R2, Q2, and GoF (Goodness-of-Fit).

4.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

To ensure the validity and reliability of the constructs, we assessed the reliability of all core variables in our measurement scheme using Cronbach’s α coefficient. As shown in Table 3, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for each core variable in this study ranged from 0.858 to 0.939. A higher α value (typically ≥ 0.70) indicates greater reliability, suggesting that the items consistently measure the same underlying construct [49]. Additionally, the composite reliability (CR) values for the constructs ranged from 0.860 to 0.940, exceeding the standard of 0.7 [50]. The average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.705 to 0.876, all surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.50 [41]. In conclusion, all constructs meet the requirements for convergent validity and are suitable for further analysis.

Table 3.

Descriptive and Measurement Assessment Results.

4.2. Assessment of Structural Model

First of all, we assessed discriminant validity using cross-loadings as recommended in previous research [51]. As shown in Table 4, the external loadings of indicators associated with each construct are significantly higher than any cross-loadings with other constructs. Therefore, the criteria for cross-loadings have been met according to the required standards.

Table 4.

The Result of Cross-loadings.

Secondly, we employed the Fornell-Larcker criterion to test discriminant validity. As shown in Table 5, the diagonal entries represent the AVE for each construct. Off-diagonal entries represent the correlation coefficients between pairs of constructs. Based on the result, the AVE of a construct is higher than the correlations between the constructs, confirming good discriminant validity among the constructs [52].

Table 5.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

Finally, we conducted a test of discriminant validity using the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations. It has been suggested that if the HTMT value is less than 0.90, discriminant validity is confirmed, and the model can be considered reliable for further analysis [53]. As shown in Table 6, all HTMT values passed the test, further demonstrating good discriminant validity among the constructs.

Table 6.

Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

4.3. Model Estimation

In the model evaluation phase, we assessed the model fit using three key indicators: R2, Q2, and GoF. R2 (Coefficient of Determination) represents the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables in the model. A significant R2 value, typically exceeding 26%, indicates strong explanatory power [41,54]. Q2 (Predictive Relevance) validates the model’s ability to predict future data. A Q2 value greater than zero signifies robust predictive capability within and outside the sample [55]. GoF (Goodness-of-Fit) is a comprehensive measure of overall model fit. A GoF value above 0.36 suggests a strong overall fit [56]. The fit indices reported in Table 7 exceeded the recommended thresholds, affirming the excellent fit of our model. This underscores the reliability and suitability of our model for rigorous analysis and interpretation in the study context.

Table 7.

Model Fit Indices.

The results of the path analysis are presented in Table 8. This study utilized PLS-SEM to investigate the impact of different visual communication design elements (VFD, VBD, VAD) on UE and PB. Additionally, we assessed potential multicollinearity among latent variables using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF). Our results showed that the VIF values for all latent variables were less than 5, indicating no issues with multicollinearity in our estimation model [41].

Table 8.

Structural Assessment Result.

From the findings, the path coefficient (β) represents the strength of the relationship between latent variables, indicating the extent to which one latent variable directly influences another. Significance level (p) represents statistically significant of path coefficient. As shown in Table 8, H7, H6, and H2 were supported, while the remaining four hypotheses were not supported. The results indicate that two distinct categories of visual communication design (VBD, VAD) directly influence urban emotions and place branding. Additionally, urban emotions were found to impact place branding. Specifically, the impact of VFD on urban emotions (β = 0.044, p = 0.314) and place branding (β = 0.124, p = 0.169) is not significant. The VBD has a significant direct impact on place branding (β = 0.335, p < 0.005), but its effect on urban emotions is not significant (β = 0.182, p = 0.186). The VAD has a direct impact on urban emotions (β = 0.542, p < 0.005), but it does not significantly affect place branding (β = −0.031, p = 0.794). Lastly, urban emotions significantly influence place branding (β = 0.505, p < 0.001).

5. Discussion

5.1. Emotional Feedback as a Systemic Driver of Place Branding

The results revealed that UE significantly influenced PB, indicating that residents’ positive emotional responses contribute not only to a favorable place image but also to the long-term viability of place branding. This underscores the importance of embedding emotional dynamics into the design of sustainable visual systems. In particular, strategies that activate place-based identity, emotional resonance, participatory behavior, and affective attachment reinforce the durability and authenticity of place branding over time. This finding aligns with the core propositions of affective urbanism [57], which regard emotion as a constitutive element in the symbolic and social construction of urban systems.

Furthermore, the results demonstrate that UE, acting as an intermediary factor, is influenced by VAD, validating our research hypotheses. Specifically, employing narrative, symbolic, and innovative visual communication designs in urban settings significantly impacts UE. It highlights the importance of designing for emotional durability, wherein affective attachments are not merely triggered by aesthetic appeal but are sustained over time through culturally embedded visual cues and place-based storytelling.

In the context of sustainable place branding, the mediating role of UE suggests that emotionally durable visual attachment design can serve as a strategic lever for long-term brand vitality. Visual identity that reflects collective memory, local symbolism, and evolving cultural narratives strengthens not only residents’ affective engagement but also the continuity of the city’s brand identity. Therefore, sustainable place branding requires more than transient image-building; it demands an investment in visual systems that support the long-term emotional identification of citizens with their city.

5.2. Visual Behavioral Mechanisms in the Branding System

VBD emerged as a pivotal subsystem directly influencing place branding, despite not significantly affecting urban emotion. This suggests that behavioral cues may operate primarily at the level of rational engagement and participatory involvement rather than directly triggering emotional resonance. In other words, VBD may bypass emotional mediation, functioning instead as an instrumental pathway that translates citizen participation into brand support.

The VBD framework consists of two key dimensions: enjoyment and interaction. Enjoyment refers to the capacity of visual design to evoke curiosity, novelty, and aesthetic pleasure. These pleasurable stimuli initiate spontaneous attention, reduce perceptual fatigue, and foster positive affective predispositions that make citizens more open to engaging with their surroundings. This aligns with branding sustainability by embedding low-barrier, repeatable moments of joy into everyday experience, reinforcing place familiarity over time. Interaction, by contrast, introduces an active component, involving co-creation and user agency through mechanisms such as gamified signage, responsive installations, or social media–linked campaigns. Together, these dimensions create feedback loops where citizens not only consume visual messages but also contribute to them, embedding symbolic practices into the urban fabric.

Taken together, enjoyment and interaction construct a behavioral infrastructure that supports sustainability not through direct emotional resonance, but via systemic engagement mechanisms. The effectiveness of VBD, however, should not be understood in isolation from VFD. Functional clarity and usability form the infrastructural foundation that enables participatory engagement to unfold. In this sense, VFD and VBD may operate in a layered relationship: VFD serving as the ground, and VBD extending this base into participatory practices that anchor sustainable brand attachment.

5.3. Symbolic Constraints in Place Branding Sustainability

The results reveal a systemic limitation in relying solely on VFD as a mechanism to influence place branding. This suggests that functional cues, while necessary for usability, are not sufficient to generate long-term affective attachment or symbolic meaning. VFD primarily ensures clarity, safety, and convenience—attributes that are essential for reducing friction in urban experience but often taken for granted once basic expectations are met.

From the perspective of emotional design, this finding resonates with the three-level model of design [58]. Functional qualities operate mainly at the visceral level, securing immediate usability but rarely producing durable emotional bonds. This explains why functional recognition, although cognitively acknowledged, seldom translates into affective engagement or brand attachment.

In the framework of place branding, however, symbolic recognition must be connected with emotional engagement, participatory behavior, and ongoing meaning-making. Without such reinforcement, even carefully designed city logos or visual codes risk remaining superficial markers, easily forgotten or replaced. Semiotic theory further highlights that symbols become meaningful only when interpreted through cultural, social, and personal lenses [59,60]. In this sense, the failure of VFD to significantly predict place branding suggests the presence of a symbolic gap, reflecting a disconnection between surface-level visual cues and the deeper lived, emotional, and behavioral experiences of citizens.

Nevertheless, VFD should not be overlooked. Its role is better understood as a necessary but insufficient condition in the branding system. Without functional clarity, behavioral and affective designs cannot be effectively experienced. With it, however, the pathway toward sustainable brand attachment still depends on higher-order mechanisms such as participatory engagement (VBD) and emotional resonance (VAD). Rather than treating symbols as static design outputs, cities must embed them in interactive interfaces, narrative environments, and co-constructed rituals that enable continuous feedback, reinterpretation, and emotional reattachment.

6. Conclusions

This study clarifies the systemic role of emotion in sustainable place branding and identifies visual design as a primary driver. By modeling the interplay between visual stimuli, emotional response, and place brand, it shows that emotionally durable visual communication works through integrated emotional and behavioral pathways rather than isolated effects. Urban emotion emerges as a central mediating node, particularly activated by symbolic and narrative-rich design (VAD), while participatory and interactive design (VBD) drives branding outcomes directly through behavioral engagement. In contrast, recognition-based design (VFD) ensures usability but lacks systemic impact unless embedded within affective or participatory loops. These findings reveal a dynamic internal structure of visual–emotional–cognitive interplay, offering both theoretical refinement of affective urbanism and practical insights for sustainable, citizen-centered brand development.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This research contributes to the growing field of affective urbanism by introducing a durability-oriented framework for visual communication design in the context of place branding. Moving beyond traditional identity-based visual design theories, which emphasize logos and symbolic identifiers, this study demonstrates that emotionally durable design must account for citizens’ long-term affective and behavioral engagement with the city.

First, the research contributes to visual design theory by conceptualizing VFD, VBD, and VAD as three interrelated but distinct dimensions that explain different pathways of influence. This refined vocabulary clarifies how functional usability (VFD), behavioral participation (VBD), and symbolic-emotional resonance (VAD) operate at different levels of urban experience, thereby extending visual design beyond representation to systemic engagement.

Second, the research contributes to place branding theory by offering a sustainability-oriented approach. Whereas prior branding models often emphasize short-term recognition or differentiation, our findings suggest that emotionally durable visual communication provides a pathway toward resilient brand systems that balance functional infrastructure with affective sustainability.

These theoretical contributions position emotionally durable visual design as both an analytical lens and a generative framework. It enables future scholarship to examine not only how cities are seen, but also how they are felt and lived, thereby aligning visual design with contemporary debates on sustainable, inclusive, and adaptive urban development.

6.2. Practical Implications

Existing research in urban governance has already demonstrated that urban emotional attachment and citizen behavior play critical roles in sustaining place branding [7,8]. These studies underline the importance of affective bonds and participatory practices in ensuring long-term brand legitimacy and resilience. However, much of this work has remained at the governance or behavioral level, offering limited guidance on how such mechanisms can be effectively implemented through design practice.

Our study addresses this gap by providing a visual design–based framework that operationalizes these governance insights into practical design strategies. By distinguishing three strategic dimensions of visual design, it offers guidance for practitioners:

- (1)

- Policy Layer: Urban planners and policymakers should embed emotional and participatory design criteria into city branding guidelines, ensuring that new projects integrate symbolic storytelling (VAD) and participatory interfaces (VBD) rather than relying solely on functional recognition (VFD).

- (2)

- Design Layer: Designers should treat VFD as a baseline of usability, while prioritizing interactive formats, co-creation tools, and narrative-driven visuals that sustain long-term citizen engagement.

- (3)

- Community Layer: Public managers can foster branding durability by encouraging citizen participation in co-designed visual initiatives—such as interactive installations, mural projects, or digital engagement platforms—that embed branding within everyday life.

Beyond design practice, these implications extend to urban planning and governance. Emotionally durable visual design can support policy legitimacy by strengthening citizens’ attachment to place, enhance public management through participatory engagement mechanisms, and enrich everyday citizen experience by embedding cultural narratives into urban environments. By aligning branding with both functionality and affective sustainability, cities can move toward a citizen-centered system of place development that is resilient, adaptive, and socially inclusive.

6.3. Limitation and Future Work

While this study provides insights into the role of visual communication design in place branding, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample was limited to residents of Wuxi, with a demographic profile skewed toward younger participants. This concentration may constrain the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. Second, although efforts were made to ensure heterogeneity in age, occupation, and education, the sampling strategy was not fully stratified, which limits the statistical robustness of the results.

Future research could address these limitations by adopting stratified or quota sampling to achieve more balanced demographic representation, as well as by including cross-city comparative studies to test the transferability of the framework. In addition, combining quantitative survey methods with qualitative approaches would allow a more comprehensive understanding of how citizens from diverse backgrounds perceive urban visuals, form emotional attachments, and contribute to sustainable place branding.

Overall, the study positions visual communication as a strategic channel through which sustainable place branding can be advanced. By structuring functional, behavioral, and affective mechanisms into an integrated framework, it demonstrates how visual design translates governance insights into actionable practices. This contributes to a citizen-centered vision of branding that is resilient, adaptive, and grounded in everyday urban experience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; methodology, H.Z.; formal analysis, H.Z.; investigation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.Z.Q.; supervision, J.W.; funding acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China Major Project in Art Studies, grant number 22ZD18. The APC was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China Major Project in Art Studies.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Pauwels, L. Visually Researching and Communicating the City: A Systematic Assessment of Methods and Resources. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 1309–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner, D. Sketches of an Emotional Geography Towards a New Citizenship. In The Urban Planet: Knowledge Towards Sustainable Cities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; p. 445. [Google Scholar]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Effect of People on Placemaking and Affective Atmospheres in City Streets. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 3389–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksmeier, P. Providing Places for Structures of Feeling and Hierarchical Complementarity in Urban Theory: Re-Reading Williams’ the Country and the City. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgou, K.; Madoglou, A.; Kalamaras, D. Exploring Emotional, Behavioural, and Cognitive Dimensions of Young Citizens’ Political Engagement in Uncertain Times. Psychol. J. Hell. Psychol. Soc. 2024, 29, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, E.; Krakover, S. The Formation of a Composite Urban Image. Geogr. Anal. 1993, 25, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argento, D.; Imre, Ö.; Johansson, M.; Rönkkö, K. Facing Sustainable City Challenges: The Quest for Attra-Chment. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2025, 21, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, X.; Guo, Y. Residents’ Engagement Behavior in Destination Branding. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Salazar-Miranda, A.; Duarte, F.; Vale, L.; Hack, G.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Batty, M.; Ratti, C. Urban Visual Intelligence: Studying Cities with Artificial Intelligence and Street-Level Imagery. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2024, 114, 876–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Chen, M. Advancing Urban Life: A Systematic Review of Emerging Technologies and Artificial Intelligence in Urban Design and Planning. Buildings 2024, 14, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhou, B.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Fung, H.H.; Lin, H.; Ratti, C. Measuring Human Perceptions of a Large-Scale Urban Region Using Machine Learning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoro, T.; Okimiji, O.P.; Yoade, A.; Olaleye, R. Urban Design and Planning: Aesthetics Current Trends for Visual City Quality, Systematic Review. J. Niger. Inst. Town Plan. 2025, 30, 175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, J.; Kang, Y.; Liu, Y.-N.; Zhang, F.; Gao, S. Places for Play: Understanding Human Perception of Playability in Cities Using Street View Images and Deep Learning. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 90, 101693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. Emotionally Durable Design: Objects, Experiences and Empathy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boffi, M.; Rainisio, N.; Inghilleri, P. Nurturing Cultural Heritages and Place Attachment through Street Art—A Longitudinal Psycho-Social Analysis of a Neighborhood Renewal Process. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; Milligan, C. Embodying Emotion Sensing Space: Introducing Emotional Geographies. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2004, 5, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. Marxism and Literature; Oxford Paperbacks: Oxford, UK, 1977; Volume 392. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, P. Mapping Meanings: A Cultural Critique of Locality Studies. Environ. Plan. A 1991, 23, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, M.P. ‘God’s Golden Acre for Children’: Pastoralism and Sense of Place in New Suburban Communities. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2537–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Toward a Social Psychology of Place: Predicting Behavior from Place-Based Cognitions, Attitude, and Identity. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hårsman Wahlström, M.; Kourtit, K.; Nijkamp, P. Planning Cities4People–A Body and Soul Analysis of Urban Neighbourhoods. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Källström, L.; Siljeklint, P. Place Branding in the Eyes of the Place Stakeholders–Paradoxes in the Perceptions of the Meaning and Scope of Place Branding. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2024, 17, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Rütter, N. Is Satisfaction the Key? The Role of Citizen Satisfaction, Place Attachment and Place Brand Attitude on Positive Citizenship Behavior. Cities 2014, 38, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.H.; Nederhand, J.; Stevens, V. The Necessity of Collaboration in Branding: Analysing the Conditions for Output Legitimacy through Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripoll González, L.; Klijn, E.H.; Eshuis, J.; Braun, E. Does Participation Predict Support for Place Brands? An Analysis of the Relationship between Stakeholder Involvement and Brand Citizenship Behavior. Public Adm. Rev. 2025, 85, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoń, K.; Kubik, A.; Ševčovič, M.; Tóth, J.; Lakatos, A. Visual Communication in Shared Mobility Systems as an Opportunity for Recognition and Competitiveness in Smart Cities. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 802–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G. Communicating the “World-Class” City: A Visual-Material Approach. Soc. Semiot. 2021, 31, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.G.; Kappas, A. Visual Emotions–Emotional Visuals: Emotions, Pathos Formulae, and Their Relevance for Communication Research. In The Routledge Handbook of Emotions and Mass Media; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010; pp. 324–345. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Lin, P.-S. Aesthetics of Sustainability: Research on the Design Strategies for Emotionally Durable Visual Communication Design. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. Place Branding: A Review of Trends and Conceptual Models. Mark. Rev. 2005, 5, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, R.; Thiéry, S. Face au Brand Territorial: Sur la Misère Symbolique des Systèmes de Représentation des Collectivités Territoriales; Lars Müller: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bresciani, S.; Del Ponte, P. New Brand Logo Design: Customers’ Preference for Brand Name and Icon. J. Brand Manag. 2017, 24, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Place Branding: Glocal, Virtual and Physical Identities, Constructed, Imagined and Experienced; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-349-31167-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E. Questioning a “One Size Fits All” City Brand: Developing a Branded House Strategy for Place Brand Management. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M.J. The Dynamics of Place Brands: An Identity-Based Approach to Place Branding Theory. Mark. Theory 2013, 13, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriadi, J.; Mardiyana, M.; Reza, B. The Concept of Color Psychology and Logos to Strengthen Brand Personality of Local Products. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2022, 6, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomor, Z.; Meijer, A.; Michels, A.; Geertman, S. Smart Governance for Sustainable Cities: Findings from a Systematic Literature Review. J. Urban Technol. 2019, 26, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuculescu, L.; Luca, F.A. Developing a Sustainable Cultural Brand for Tourist Cities: Insights from Cultural Managers and the Gen Z Community in Brașov, Romania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, P.; Laaksonen, M.; Borisov, P.; Halkoaho, J. Measuring Image of a City: A Qualitative Approach with Case Example. Place Brand. 2006, 2, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Sawadsri, A.; Kritsanaphan, A.; Nickpour, F. Urban Branding Through Cultural–Creative Tourism: A Review of Youth Engagement for Sustainable Development. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Casakin, H.; Hernández, B.; Ruiz, C. Place Attachment and Place Identity in Israeli Cities: The Influence of City Size. Cities 2015, 42, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferstein, H.N.; Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, E.P. Consumer-Product Attachment: Measurement and Design Implications. Int. J. Des. 2008, 2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Gadd, M.; Chapman, J.; Lloyd, P.; Mason, J.; Aliakseyeu, D. Design Framework for Emotionally Durable Products and Services. In PLATE: Product Lifetimes and the Environment; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Van Krieken, B.M. A Sneaky Kettle-Emotionally Durable Design Explored in Practice. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, A. Psychologically Durable Design—Definitions and Approaches. Des. J. 2019, 22, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.H.; Rein, I. Marketing Places: Attracting Investment, Industry, and Tourism to Cities, States, and Nations; Free Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Romo-González, J.R.; Tarango, J.; Machin-Mastromatteo, J.D. PLS SEM, a Quantitative Methodology to Test Theoretical Models from Library and Information Science. Inf. Dev. 2018, 34, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C. Structural Equation Modeling and Regression: Guidelines for Research Practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.J. Testing Evolutionary and Ecological Hypotheses Using Path Analysis and Structural Equation Modelling. Funct. Ecol. 1992, 6, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. ISBN 978-1-84855-468-9. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S.; D’ambra, J.; Ray, P. An Evaluation of PLS Based Complex Models: The Roles of Power Analysis, Predictive Relevance and GoF Index. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Detroit, MI, USA, 4–7 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Thrift, N. Cities: Reimagining the Urban; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Symbolism and Environmental Design. J. Archit. Educ. 1974, 27, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyanto, D.Y. Visual Semiotics and Cultural Representation: Exploring the Role of Symbols and Icons in Visual Communication Design. Int. J. Des. Innov. 2023, 2, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).