Failure Analysis and SME Growth: The Role of Dynamic Capabilities and Environmental Dynamism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. SME Growth

2.2. Failure Analysis

2.3. Research Model

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Failure Analysis and Firm Growth

3.2. Mediating Effect of Dynamic Capability

3.3. Moderating Effect of Environmental Dynamism

4. Method

4.1. Sample

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Variables and Measures

4.3.1. Failure Analysis (FA)

4.3.2. Dynamic Capability (DC)

4.3.3. Environmental Dynamism (ED)

4.3.4. Firm Growth (FG)

4.3.5. Control Variables

4.4. Reliability and Validity

4.5. Common Method Variance

5. Results

5.1. Correlation Matrix

5.2. Results of Hypothesis Tests

5.2.1. The Main Effect

5.2.2. The Mediating Effect

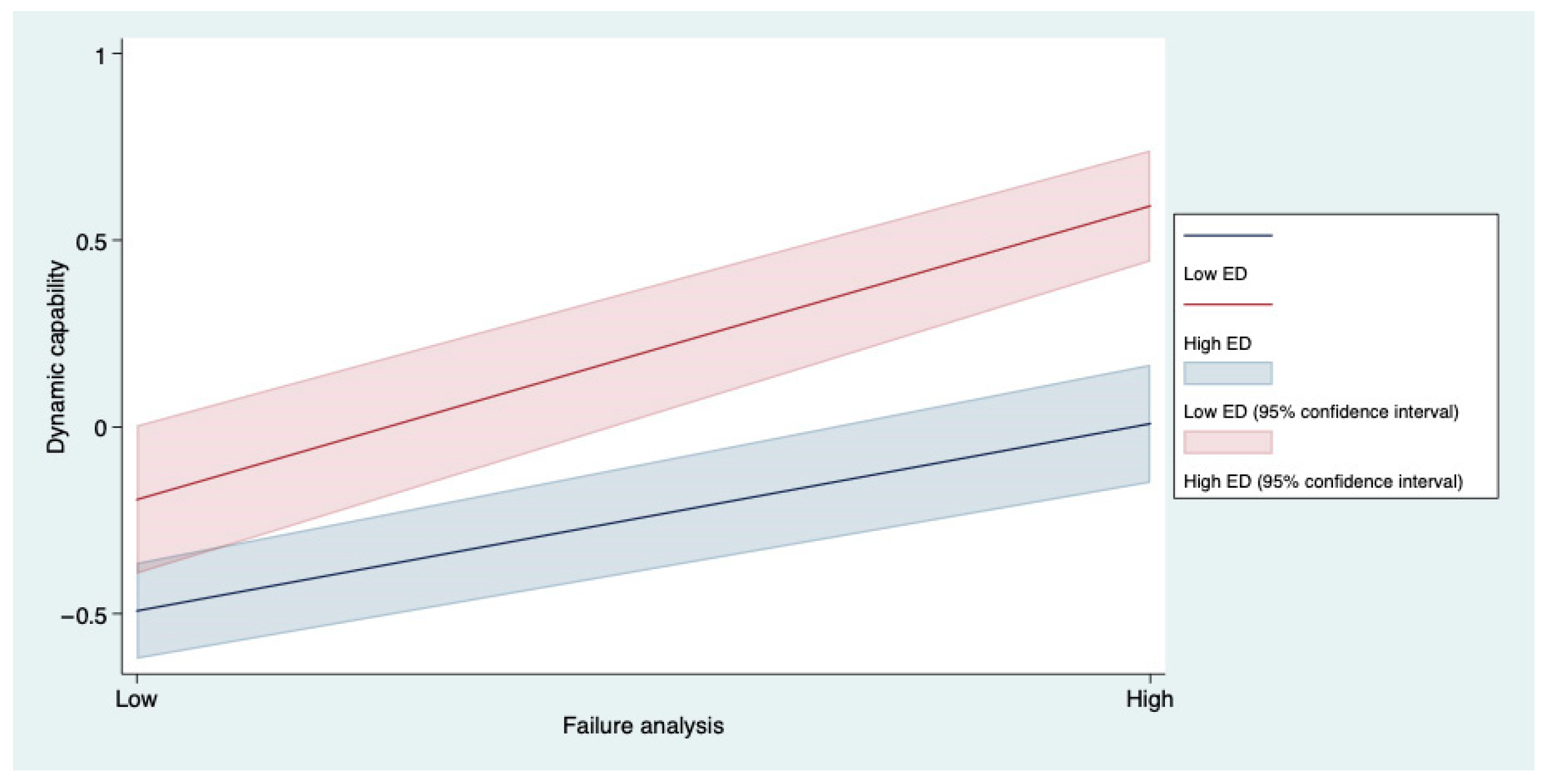

5.2.3. The Moderating Effect

5.3. Robustness Check and Additional Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author (Year) | Factors Influencing SME Growth | Theory | Sample | Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Havnes and Senneseth (2001) [66] | 1. Firm’s network | / | 1700 firms SMEs in 8 European countries | Secondary data | Networking is associated with high growth in the geographic extension of markets, which suggests that networking sustains long-term objectives of the firms. |

| Hossain et al. (2016) [13] | 1. Owner–manager characteristics 2. Characteristics of the firm 3. Financial factors 4. External environment | / | 34 papers during 2006–2014 | Review | The four broad areas of factors have been focused on—namely, owner–manager characteristics, characteristics of the firm, financial factors, and external environment. |

| EI Shoubaki et al. (2020) [12] | 1. Human capital | Human capital theory | 46,412 French small businesses | Secondary data | Reasons to start a business mediate the relation between firm growth and SME owner–managers’ human capital (discriminating between specific and general human capital). |

| Lim et al. (2020) [14] | 1. Global crisis | Resource system perspective | Canadian high-growth SMEs | Qualitative | Firm growth is the expansion of the system of resource components, including strategic, physical, financial, human, and organizational resources. |

| Ikram et al. (2020) [67] | 1. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities | Stakeholder theory | 340 SMEs in Pakistan | Survey | Results reveal significant relationships between CSR and two determinants of firm performance, namely, employee commitment and corporate reputation. |

| Rafiki (2020) [15] | 1. Human capital (manager’s experience, education, training) 2. Social capital (firm’s networks) 3. Firm’s strategy (financing) 4. Firm characteristics (size; age) | Resource-based view | 119 managers from SMEs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | Survey | Firm size, manager’s experience, education, training, financing, and the firm’s networks have a significant relationship with the firm’s growth. However, manager’s education and firm age do not have a significant relationship with the firm’s growth. |

| Audretsch and Belitski (2021) [50] | 1. Knowledge complexity | / | 102 European SMEs | Survey | Compared to other acumens of knowledge complexity, managerial and operational acumens contribute the most to a firm’s performance (sales and productivity). |

| Scuotto et al. (2021) [16] | 1. Individual digital capabilities (information skills, communication skills, software skills) | Micro-foundations lens | 2,156,360 European SMEs | Survey | Individual digital capabilities have assumed an equally crucial role for growth and innovation in our increasingly digital competitive reality. |

| Rafiki et al. (2023) [68] | 1. Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) 2. Personal value 3. Organizational learning (OL) | Resource-based view | 128 respondents (owner-managers) of SMEs | Survey | Innovativeness of EO and personal value both have a significant relationship with firm growth. OL, proactiveness and risk-taking of EO are insignificantly related to firm growth, while risk-taking of EO also insignificantly mediates the relationship of OL and firm growth. |

References

- Kindström, D.; Carlborg, P.; Nord, T. Challenges for growing SMEs: A managerial perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 700–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, M.; Penco, L.; Profumo, G.; Quaglia, R. Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressy, R. Why do most firms die young? Small Bus. Econ. 2006, 26, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Yu, X.; Yue, S.; Li, B. Unpacking the Specialization Paradox: The Impact of Founder’s Industry Experience on Becoming a Niche Leader. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstner, F.F.; Vassolo, R.; Sevil, A. Different strokes for different folks: A review of SME decline and turnaround. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, H. Innovation failure in SMEs: A narrative approach to understand failed innovations and failed innovators. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 2150104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Cao, G.; Wang, X. Entrepreneurial bricolage and disruptive innovation: The joint effect of learning from failure and institutional voids. RD Manag. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, E.; Rabetino, R.; Leiva, J.C. Learning from success and failure: Implications for entrepreneurs, SMEs, and policy. Small Bus. Econ. 2025, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, J. Giving up learning from failures? An examination of learning from one’s own failures in the context of heart surgeons. Strateg. Manag. J. 2024, 45, 2063–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danneels, E.; Vestal, A. Normalizing vs. analyzing: Drawing the lessons from failure to enhance firm innovativeness. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Games, D.; Lupiyoadi, R.; Agustina, T.S.; Amsal, A.A.; Kartika, R. Social capital, learning from innovation failure, and innovation: Some insights from high-growth small businesses in a collectivist culture. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 27, 2350007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shoubaki, A.; Laguir, I.; Den Besten, M. Human capital and SME growth: The mediating role of reasons to start a business. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 1107–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Ibrahim, Y.; Uddin, M. Towards the factors affecting small firm growth: Review of previous studies. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2016, 6, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.S.; Morse, E.A.; Yu, N. The impact of the global crisis on the growth of SMEs: A resource system perspective. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiki, A. Determinants of SME growth: An empirical study in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 28, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuotto, V.; Nicotra, M.; Del Giudice, M.; Krueger, N.; Gregori, G.L. A microfoundational perspective on SMEs’ growth in the digital transformation era. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Innovation failure and firm growth: Dependence on firm size and age. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2022, 34, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koporcic, N.; Sjödin, D.; Kohtamäki, M.; Parida, V. Embracing the “fail fast and learn fast” mindset: Conceptualizing learning from failure in knowledge-intensive SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2025, 64, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shui, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, C. Benefit from market knowledge: Failure analysis capability and venture goal progress in a turbulent environment. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 113, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Li, X.; Liang, B. Failure learning and entrepreneurial resilience: The moderating role of firms’ knowledge breadth and knowledge depth. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 2141–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L.; Lee, S.; Park, J. Organizational learning processes and outcomes: Major findings and future research directions. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 5399–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, S.; Chen, J. Bridging yesterday, today, and tomorrow: CEO temporal focus, environmental dynamism, and rate of new product introduction. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1810–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L. Social media strategic capability, organizational unlearning, and disruptive innovation of SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.; Budhwar, P.; Shipton, H.; Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, B. Building organizational resilience, innovation through resource-based management initiatives, organizational learning and environmental dynamism. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.Y.; Kim, S. Effects of inter-and intra-organizational learning activities on SME innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvello, V.; Troise, C.; Schiuma, G.; Jones, P. How start-ups translate learning from innovation failure into strategies for growth. Technovation 2024, 134, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S.K.; Rahman, S.A.; Nikbin, D.; Radomska, M.; Maleki Far, S. Dynamic capabilities of the SMEs for sustainable innovation performance. J. Organ. Eff. 2024, 11, 767–787. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford Univ Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Sithipolvanichgul, J.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P. Decomposition of double-loop failure risk in post-innovation failure phase. Technovation 2025, 140, 103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A. Learning from business failure: Propositions of grief recovery for the self-employed. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.D.; Edmondson, A.C. Failing to learn and learning to fail (intelligently). Long. Range Plann. 2005, 38, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protogerou, A.; Caloghirou, Y.; Lioukas, S. Dynamic capabilities and their indirect impact on firm performance. Ind. Corp. Change 2012, 21, 615–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Luño, A.; Wiklund, J.; Cabrera, R.V. The dual nature of innovative activity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaiem, K.; Halilem, N. The worst is not to fail, but to fail to learn from failure. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 190, 122427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Winter, S.G. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, K.B.; Chuang, Y.T.; Roulet, T.J. Opportunity, motivation, and ability to learn from failures and errors. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2018, 12, 252–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais-Storz, M.; Nguyen, N.; Sætre, A.S. Post-failure success: Sensemaking in problem representation reformulation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2020, 37, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, R.; Gudergan, S.P.; Nielsen, B.B.; Lings, I. Dynamic capabilities and performance. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 72–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtley, J.; O’Mahony, S. What is a pivot? Explaining when and how entrepreneurial firms decide to make strategic change and pivot. Strateg. Manag. J. 2023, 44, 197–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Leih, S. Uncertainty, innovation, and dynamic capabilities. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, F.; Teo, T.S.; Guo, W. Antecedents and consequence of organizational unlearning. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 84, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Li, H. Strategic decision comprehensiveness and new product development outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Huang, R.; Duan, Y.; Sunguo, T.; Dello Strologo, A. Exploring the impacts of knowledge recombination on firms’ breakthrough innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 698–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Tang, J. The role of entrepreneurs in firm-level innovation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Borisov, A.; Modi, S.; Huang, X. Learning from failure: The implications of product recalls for firm innovation. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2023, 59, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzabbar, D.; Lahiri, A.; Seo, D.J.; Boeker, W. When opportunity meets ability. Strat. Mgmt J. 2023, 44, 2534–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Knowledge complexity and firm performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshima, Y.; Anderson, B.S. Firm growth, adaptive capability, and entrepreneurial orientation. Strat. Mgmt J. 2017, 38, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.S.; Eshima, Y. The influence of firm age and intangible resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.; Perez, J.P. Testing mediating effects of individual entrepreneurial orientation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfons, A.; Ateş, N.Y.; Groenen, P.J. A robust bootstrap test for mediation analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2022, 25, 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Charlotte, NC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, R.G. Who Learns Fastest, Wins: Lean Startup and Discovery Driven Growth. J. Manag. 2023, 50, 3162–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvie, A.; Wiklund, J. Advancing firm growth research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternad, D.; Mödritscher, G. Qualitative growth: An alternative to solely quantitatively-oriented theories of firm growth. In Alternative Theories of the Firm; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.F.; Fathi, M.; Chiang, D.M.; Pardalos, P.M. Credit guarantee mechanism with information asymmetry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4877–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appio, F.P.; Capo, F.; Annosi, M.C. Not all (innovation) failures are created equal. Technovation 2024, 130, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havnes, P.A.; Senneseth, K. A panel study of firm growth among SMEs in networks. Small Bus. Econ. 2001, 16, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Sroufe, R.; Mohsin, M.; Solangi, Y.A.; Shah, S.Z.A.; Shahzad, F. Does CSR influence firm performance? J. Glob. Responsib. 2020, 11, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiki, A.; Nasution, M.D.T.P.; Rossanty, Y.; Sari, P.B. Organizational learning, entrepreneurial orientation and personal values towards SMEs’ growth in Indonesia. J. Sci. Technol. Pol. Manag. 2023, 14, 181–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Type | Number | Percentage/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm size | 1–10 | 28 | 13.53 |

| 11–30 | 45 | 21.74 | |

| 31–100 | 30 | 14.49 | |

| 101–300 | 31 | 14.98 | |

| 301–500 | 19 | 9.18 | |

| 501–1000 | 54 | 26.09 | |

| Firm age | ≤10 years | 97 | 46.86 |

| 11–20 years | 63 | 30.43 | |

| 21–30 years | 29 | 14.01 | |

| >31 years | 18 | 8.70 | |

| Ownership | State-owned | 21 | 10.14 |

| Joint venture | 11 | 5.31 | |

| Private | 159 | 76.81 | |

| Foreign-funded | 11 | 5.31 | |

| Other | 5 | 2.42 | |

| R&D investment | <1% | 33 | 15.94 |

| 1–2% | 24 | 11.59 | |

| 2–3% | 35 | 16.91 | |

| 3–5% | 33 | 15.94 | |

| >5% | 82 | 39.61 | |

| Industry | Manufacturing | 60 | 28.99 |

| Other | 147 | 71.01 |

| Variables | Items | Loading | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure analysis | 1. We openly analyze past mistakes. | 0.751 | Danneels & Vestal, 2020 [10] |

| 2. We go to great lengths to learn from failures. | 0.826 | ||

| 3. We review past decisions, especially if they did not lead to success. | 0.768 | ||

| 4. We conduct post-mortems. | 0.840 | ||

| 5. We examine failures for “lessons learned”. | 0.705 | ||

| Dynamic capability * | 1. People participate in professional association activities. | 0.602 | Wilden et al., 2013 [40] |

| 2. We use established processes to identify target market segments, changing customer needs, and customer innovation. | 0.714 | ||

| 3. We observe best practices in our sector. | 0.746 | ||

| 4. We gather economic information on our operations and operational environment. | 0.652 | ||

| 5. We invest in finding solutions for our customers. | 0.675 | ||

| 6. We adopt the best practices in our sector. | 0.712 | ||

| 7. We respond to defects pointed out by employees. | 0.684 | ||

| 8. We change our practices when customer feedback gives us a reason to change. | 0.602 | ||

| 9. In the past three years, we have implemented new kinds of management methods. | 0.701 | ||

| 10. Substantial renewal of business processes | 0.709 | ||

| 11. New or substantially changed ways of achieving our targets and objectives | 0.674 | ||

| Environmental dynamism | 1. Our firm must change its marketing practices extremely frequently. | 0.716 | Pérez-Luño et al., 2011 [35] |

| 2. The rate of obsolescence is very high. | 0.860 | ||

| 3. Actions of competitors are unpredictable. | 0.607 | ||

| 4. Demand and tastes are almost unpredictable. | 0.752 | ||

| 5. The modes of production/service change often and in major ways. | 0.709 | ||

| Firm growth | 1. Sales growth | 0.839 | Eshima & Anderson, 2017 [51] |

| 2. Market share growth | 0.858 | ||

| 3. Employee growth | 0.867 |

| Variables | Cronbach’s α | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure analysis | 0.881 | 0.608 | 0.885 |

| Dynamic capability | 0.903 | 0.463 | 0.904 |

| Environmental dynamism | 0.850 | 0.538 | 0.852 |

| Firm growth | 0.890 | 0.731 | 0.891 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ownership | 1.000 | |||||||

| 2. Firm age | −0.089 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 3. R&D | −0.125 | 0.159 * | 1.000 | |||||

| 4. Industry | −0.094 | 0.150 * | 0.214 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| 5. FA | −0.031 | 0.046 | 0.126 | 0.148 * | 1.000 | |||

| 6. ED | −0.098 | 0.051 | −0.026 | 0.035 | 0.275 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 7. DC | −0.091 | 0.119 | 0.224 ** | 0.118 | 0.489 *** | 0.313 *** | 1.000 | |

| 8. FG | −0.164 * | 0.044 | −0.204 ** | 0.050 | 0.208 ** | 0.179 ** | 0.476 *** | 1.000 |

| Mean | 2.85 | 14.68 | 3.52 | 0.29 | 5.83 | 4.99 | 5.68 | 5.27 |

| SD | 0.77 | 17.78 | 1.50 | 0.45 | 0.93 | 1.15 | 0.74 | 1.00 |

| Model | Factors | χ2 | df | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | FA, DC, ED, FG | 462.839 | 246 | 1.881 | 0.905 | 0.916 | 0.065 |

| Three-factor model | FA + DC, ED, FG | 799.704 | 249 | 3.212 | 0.762 | 0.785 | 0.103 |

| Three-factor model | FA + ED, DC, FG | 826.920 | 249 | 3.302 | 0.775 | 0.750 | 0.106 |

| Three-factor model | FA, ED + DC, FG | 811.111 | 249 | 3.257 | 0.757 | 0.781 | 0.104 |

| Two-factor model | FA + DC, ED + FG | 1202.557 | 251 | 4.791 | 0.592 | 0.629 | 0.135 |

| Two-factor model | FA + DC + ED, FG | 1142.295 | 251 | 4.551 | 0.618 | 0.653 | 0.131 |

| One-factor model | FA + DC + ED + FG | 1410.276 | 252 | 5.596 | 0.506 | 0.549 | 0.149 |

| Firm Growth | Dynamic Capability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Ownership | −0.141 + (0.090) | −0.140 * (0.089) | −0.114 + (0.081) | −0.113 + (0.081) | −0.060 (0.065) | −0.057 (0.058) | −0.027 (0.054) | −0.035 (0.054) |

| Firm age | 0.002 (0.004) | 0.000 (0.004) | −0.031 (0.004) | −0.032 (0.004) | 0.075 (0.003) | 0.069 (0.003) | 0.056 (0.002) | 0.055 (0.002) |

| R&D | 0.187 ** (0.047) | 0.169 * (0.047) | 0.107 + (0.043) | 0.107 + (0.043) | 0.180 * (0.034) | 0.135 * (0.030) | 0.160 ** (0.029) | 0.157 ** (0.028) |

| Industry | −0.004 (0.155) | −0.027 (0.154) | −0.033 (0.139) | −0.030 (0.140) | 0.064 (0.112) | 0.006 (0.100) | 0.008 (0.094) | 0.005 (0.093) |

| Independent variable | ||||||||

| FA (H1) | 0.187 ** (0.073) | −0.030 (0.076) | 0.466 *** (0.048) | 0.377 *** (0.046) | 0.445 *** (0.051) | |||

| Mediating variable | ||||||||

| DC (H2) | 0.450 *** (0.087) | 0.464 *** (0.099) | ||||||

| Moderating variable | ||||||||

| ED | 0.316 *** (0.037) | 0.304 *** (0.037) | ||||||

| Interaction | ||||||||

| FA * ED (H3) | 0.148 * (0.028) | |||||||

| R2 | 0.061 | 0.095 | 0.251 | 0.252 | 0.060 | 0.271 | 0.362 | 0.379 |

| △R2 | 0.043 | 0.073 | 0.233 | 0.230 | 0.042 | 0.253 | 0.343 | 0.357 |

| F | 3.299 | 4.224 | 13.50 | 11.23 | 3.244 | 14.93 | 18.89 | 17.37 |

| Max VIF | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.37 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.38 |

| Pathway | Standardized Path Coefficients | Standard Error | C.R. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC <---FA | 0.542 | 0.046 | 9.440 | *** |

| FG <---DC | 0.507 | 0.078 | 7.022 | *** |

| FG <---FA | −0.032 | 0.097 | −0.436 | 0.663 |

| FG <---FA * DC | 0.167 | 0.027 | 2.912 | 0.004 |

| Indirect Effects Pathway | Variable | Efficiency Value | Standard Error | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||||

| FA→DC→FG | Low ED (−1 SD) | 0.289 | 0.047 | 6.131 | 0.000 | 0.196 | 0.382 |

| Average value (M) | 0.365 | 0.509 | 7.169 | 0.000 | 0.265 | 0.466 | |

| High ED (+1 SD) | 0.442 | 0.714 | 6.182 | 0.000 | 0.301 | 0.582 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, X.; Chen, L.; Yu, X. Failure Analysis and SME Growth: The Role of Dynamic Capabilities and Environmental Dynamism. Systems 2025, 13, 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13080690

Ma X, Chen L, Yu X. Failure Analysis and SME Growth: The Role of Dynamic Capabilities and Environmental Dynamism. Systems. 2025; 13(8):690. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13080690

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Xiaoshu, Luqian Chen, and Xiaoyu Yu. 2025. "Failure Analysis and SME Growth: The Role of Dynamic Capabilities and Environmental Dynamism" Systems 13, no. 8: 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13080690

APA StyleMa, X., Chen, L., & Yu, X. (2025). Failure Analysis and SME Growth: The Role of Dynamic Capabilities and Environmental Dynamism. Systems, 13(8), 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13080690