Abstract

The effective design of logistics platform business models is an important means for platform-type logistics enterprises to gain a competitive advantage. This study employs RRS Logistics as a case study to clarify the dynamic environmental mechanisms of logistics platform business models from the perspective of value co-creation and build a novel structural framework for logistics platform business models with community at their core. The research findings are as follows: First, guided by the idea of “value positioning–value co–creation–value support–value maintenance–value capture”, the conceptual framework of business models is redefined. The key steps in designing logistics platform business models, which can provide guidance and assistance for different logistics platforms, are proposed. Second, the design process for logistics platform business models should be dynamically adjusted in real time according to changes and environmental uncertainty. Third, in the process of transitioning to an ecological platform, logistics platforms’ ecosystem service clusters and ecosystem envelope are key factors in achieving a win–win scenario for all the stakeholders in the community. The case studies show that in logistics platform business model design, methods and key steps based on value co-creation could enhance the core competitiveness of logistics platforms.

1. Introduction

Logistics platform business models have been developed to improve the performance of logistical activities in a supply chain [1]. A collaborative logistics network has a new service style that is oriented toward a platform economy [2]. In recent years, tech-driven logistics platform enterprises such as Full Truck Alliance, G7 Connect, and Lalamove, as well as non-vehicle logistics platforms such as Transfar Logistics, Logory Logistics, and FOR-U Family, have been rapidly growing in China. These online freight platforms employ more than 20% of the truck drivers in China [3]. Under the impetus of multiple factors, such as the digital economy, artificial intelligence, and open innovation, some logistics platforms have strengthened their cross-border innovation and strategic cooperation. These enterprises have achieved healthy development through value co-creation [4]. In contrast to traditional enterprise-centered value creation, a value co-creation enterprise emphasizes a customer-centric approach and invites customers to actively participate in value creation and growth [5]. For example, JD.COM, RRS Logistics, and SF-Express have all become “super” logistics platforms and compete based on their value co-creation business models. However, some logistics platforms still experience problems such as a lack of purposefulness and insufficient innovation in business model design, as well as a lack of interaction between different entities.

Some platforms have unclear business models, face homogenized competition, and ignore the consumer experience, resulting in difficulties with achieving a balance between logistics demand and supply and insufficient user stickiness. In recent years, logistics platforms in China have been challenged by the impact of “dual carbon+” (i.e., carbon peaking and carbon neutrality), fierce price wars, and reduced investment, leading to many companies undergoing strategic transformation or being eliminated. Yunniao Logistics, a well-known logistics platform in China that once signed 700,000 drivers and was valued at CNY 7 billion, ultimately went bankrupt in 2021 due to neglecting the interests of drivers and shippers; that is, it failed to bring value to stakeholders.

Of course, a few platforms have gradually shifted from the “asset-light” model to the “O2O+ light–heavy combination” model, which attaches importance to value-added services and personalized solutions. For instance, RRS Logistics shifted from a model focused solely on transportation to providing a comprehensive “transportation + data + finance” solution and launched a “freight factoring + dynamic insurance” product to help shippers reduce their capital occupation costs by approximately 40%.

At present, the research on logistics platforms mainly focuses on single-platform models and studies comparing platforms [6,7,8,9]. Some scholars are paying attention to the sustainable development of the consumer experience and innovation ecology in this new economic era [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. The methods and standards of business model design have not yet been unified, and universal business model innovation is still under exploration. Moreover, in the field of logistics platform innovation, few scholars combine the two theories of value co-creation and innovation ecosystems in their research, and even fewer have achieved practical applications. The research on value co-creation with stakeholders, real-time and dynamic adjustments, and design steps is not in-depth enough.

Business models involve the logic followed and strategic choices made by enterprises in order to create and obtain value in their value network, and they are the key to revealing the laws and characteristics of economic platform development [17,18]. Business model design is the process in which major participants reshape a series of value activities through value co-creation [19]. Within this, certain strategic steps need to be followed; that is, stakeholders need to be identified through holistic, broad, long-term, and dynamic observation, and the construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of the value chain should be carried out in different stages [20,21,22]. However, some decision-makers (or experts) ignore the customer experience regarding value co-creation and the importance of interaction. The essence of platform-based enterprise business models lies in a positive feedback mechanism between users and merchants, as well as between users of the platform. Some researchers believe that the platform type is the cornerstone of business model selection, and only a business model that is dynamically adapted and highly compatible with the platform type can ensure the platform’s high-quality development [8].

Value co-creation is a core feature of modern business models, and satisfying the expected interests of all the participants is an important starting point [23]. Value co-creation means that the stakeholders in an innovation ecosystem, such as the suppliers, business partners, alliances, and customers, exchange and split their own resources with the community at its core, jointly creating value and sharing in the results in a heterogeneous and interactive way [24,25,26]. Hein et al. (2019) pointed out that value co-creation is the process of value creation shared between actors within a service ecosystem on a service platform [27]. Hughes et al. (2018) put forward that value is always jointly created by enterprises and customers, and it can only be realized when customers use the service [28]. A value co-creation strategy aims to integrate people, organizations, and technologies and build a system like a symbiotic environment, in which all the stakeholders in the system interact with and benefit each other based on a common commitment to the value co-creation project.

Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004) constructed a DART model to stimulate and improve the efficiency of value co-creation between businesses and consumers [5]. The DART model involves relying on Dialogue, Access, Risk Assessment, and Transparency to create value among different entities [29]. The literature on the DART model demonstrates its role as a building block of value creation that allows customers to interact with firms as active players in generating ideas and the development of services. This interaction has proved to be the locus of innovation and competency [30]. Some researchers have proposed a framework for realizing value co-creation in knowledge-intensive industries [31] and built a value co-creation model based on aspects such as the available resources and service capabilities [32,33,34]. In this article, we expand the theory of value co-creation; that is, we consider that the participants in value co-creation not only include core enterprises and customers but also service providers and integrators, and other stakeholders in the upstream and downstream parts of the supply chain. These stakeholders work together based on the goal of value co-creation to enhance the product quality and service levels, with the advancement of each participant’s interests taken into account.

There are still some shortcomings in the current research on platform-based enterprise business models. Firstly, considering the content of the existing theoretical research, there is not only a lack of related research on the accelerated development of logistics platforms but also a lack of thematic research on logistics platform business model design. Secondly, regarding research methods, there is a lack of design paradigms that take multiple perspectives (such as by considering both value co-creation and innovation ecosystems) and use multiple methods (combined with case studies) for business model research [35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Thirdly, in relation to external environments, the precursors and transmission mechanisms of phased business model design are unclear, and the dynamic environmental impact mechanisms of business models are ignored in research [42]. Fourthly, concerning applications’ effectiveness, the process of business model design lacks operability in specific industries, and there are no clear and standardized process design steps, which makes it difficult to guide complex decision-making activities.

A good business model should take into account stakeholders’ motivations and the needs of all parties, which should be met through the design of multiple cooperation and transaction mechanisms [43]. This paper considers these requirements from the perspective of value co-creation, through which a platform’s value creation model will ultimately evolve dynamically into an ecosystem envelope made up of ecosystem service clusters.

2. Research Methods

2.1. Case Study Methods

RRS Logistics is the first “unicorn” platform enterprise in China’s logistics industry, and it is also a leading Chinese heavy cargo transportation brand. We chose to use RRS Logistics as an exploratory and explanatory case study on the design of logistics platform business models. The basis for this selection was as follows: Firstly, the leaders of RRS Logistics fully recognize that both strategic positioning and business models have a very important and far-reaching impact on the development of the company’s core competitiveness. Secondly, RRS Logistics always keeps a close eye on dynamic changes in its external environment. When the external environment does not match the company’s development strategy, RRS Logistics redesigns its business models to adapt to new changes. For instance, since its establishment, the company has made four major leaps to adapt to new development situations. Thirdly, RRS Logistics attaches great importance to market and customer feedback. It has designed business models tailored to different urban and rural communities and has sequentially achieved real-time community interaction and the development of a complete ecosystem, and a clear profit model. Therefore, the case of RRS Logistics is typical and representative. Leveraging academic sources, our geographical location, and interpersonal connections, the available data was highly accessible, making research relatively convenient. The research materials included data from field investigations and telephone and executive interviews, materials publicly available on the company’s official website, news reports, and periodicals. A content analysis method was adopted in this study [44].

2.2. Overview of RRS Logistics

RRS Logistics is affiliated with the Hong Kong-listed company Haier Electric Appliances. Its development has occurred over four stages: enterprise logistics → a logistics enterprise → a platform enterprise → an ecosystem enterprise. Relying on advanced management concepts and logistics technologies, integrated with world-class network resources, RRS Logistics has grown into a professional, standardized, and intelligent logistics platform enterprise. It has always adhered to the standard of providing the best user experience. Relying on the core competitiveness of its unified warehousing, distribution, service, and information networks, it provides customers with integrated supply chain service solutions.

3. Steps in Logistics Platform Business Model Design

3.1. Step 1: Data-Driven Demand Mining

Collecting valuable customer data not only optimizes the customer experience and enhances consumer loyalty but also enables multiple entities, such as core enterprises, consumers, retailers, and manufacturers, to achieve value co-creation. A company’s value positioning must be determined first in the process of business model design. Based on user-oriented and consumer experience theories, the first step is demand mining using big data or artificial intelligence. When developing a new product or service, RRS Logistics has always collected a large amount of data, including distributed, shared cloud warehouse network data, Gome Online user data, and rural consumption demand data, which are used along with big data to improve the customer experience based on value co-creation.

The cloud warehousing of RRS Logistics is centered on the user experience. According to customer demand, this enterprise coordinates its distributed, shared cloud warehouse network with online–offline inventories. This customized supply chain integration solution and big data analysis prediction can effectively reduce customers’ total inventory cost, further shorten the delivery cycle, and thereby enhance the user experience. Using Gome Online data, including purchase preferences and demands and product feedback, RRS Logistics continuously consolidates its advantages in e-commerce logistics, thereby expanding the scale of C2B and further enhancing its cloud delivery capabilities. The above data are open access and obtained by RRS Logistics from the Haier Group. Furthermore, RRS Logistics is affiliated with RRS Lenong, which caters to the consumption demands in rural areas. Ririshun Lenong acquires big data on rural consumption through a combination of multiple APPs (i.e., third-party applications for smartphones), WeChat, and interactive on-site activities. Moreover, using the aforementioned big data, RRS Lenong has developed facilities such as healthy water stations, customized laundry services, and smart ecological parks based on community ecosystems. In conclusion, RRS Logistics relies on its big data analysis service platform to explore customer demands and achieve intelligent decision-making and value co-creation.

3.2. Step 2: Conceptual Framework of Business Models

This study combines modularization theory [45] with business model design, providing new ideas for business model design research. The continuous development of technology and changes in the external environment prompt enterprises to constantly update their business models. A business model is regarded as a modular system, which can be decomposed into three layers: unit, structural, and functional modules. Table 1 shows that RRS Logistics has achieved value co-creation by means of four sub-modules—the value consensus, symbiosis, sharing, and win–win scenario sub-modules, which have reshaped the value ecosystem.

Table 1.

The value-related sub-modules of RRS Logistics’ business model.

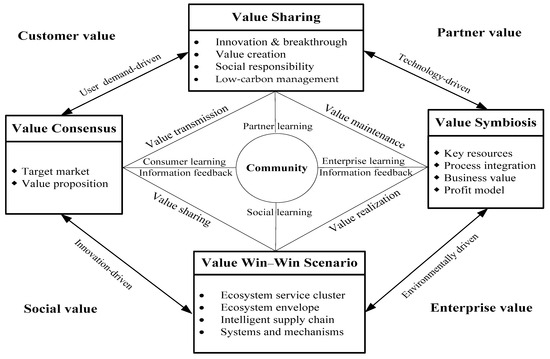

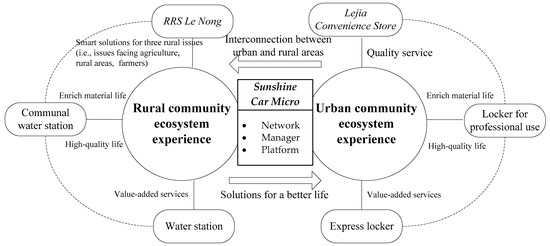

With the development of a network economy characterized by Internet technology, the focus of value co-creation has shifted from binary interactions between enterprises and customers to the dynamic network interactions of multiple social and economic participants [29]. The process of value co-creation includes four elements: value consensus, symbiosis, sharing, and win–win scenarios [46]. Value consensus refers to different parties having basically consistent views on the value of something. Value symbiosis refers to different individuals achieving common development on the basis of interdependence and mutual benefits. Value sharing refers to a situation where enterprises, while pursuing their own interests, strive to create and distribute value so that all stakeholders can benefit. A value win–win scenario refers to all parties achieving, based on common values, their goal of mutual benefits and a win–win scenario through mutual support and cooperation. Some research shows that platform governance mechanisms have a significant influence on crowdsourcing’s ability to foster value co-creation on a platform [47]. As a resource, community has replaced the previously used technology and channels, becoming heterogeneous, and the focus at the core of platform business models has gradually changed from the customer to the community [46,48]. Therefore, we propose a structural framework of a community-centered platform business model based on value co-creation, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structural framework of a business model based on value co-creation.

Figure 1 shows a platform business model comprising a value co-creation system jointly constructed by core enterprises and heterogeneous stakeholders, and its structural framework displays “4-4-14” characteristics. The first “4” represents the constituent units, including value consensus, value symbiosis, value sharing, and value win–win scenarios. Specifically, value consensus includes the target market and value proposition, and value symbiosis includes key resources, process integration, the business value, and a profit model. Value sharing comprises innovations and breakthroughs, value creation, social responsibility, and low-carbon management, while the value win–win scenario unit includes ecosystem service clusters, ecosystem envelopes, intelligent supply chains, and systems and mechanisms. The mechanism of action connecting the constituent units comprises five aspects: interconnected, user demand-driven, technology-driven, environmentally driven, and innovation-driven action. The second “4” represents customer, enterprise, partner, and social value. The “14” represents the component factors: the target market, value proposition, key resources, process integration, the business value, the profit model, innovations and breakthroughs, value creation, social responsibility, sustainability, ecosystem service clusters, ecosystem envelopes, intelligent supply chains, and systems and mechanisms. This three-dimensional structural model has community at its center and enables value transmission, maintenance, realization, and sharing through consumer, enterprise, partner, and social learning and information feedback.

The value co-creation-based business model structure proposed in this paper has three main novel aspects: Firstly, in this model, the community is considered to be at the core of realizing value consensus, sharing, symbiosis, and win–win scenarios. The community can achieve value maintenance, transmission, sharing, and win–win scenarios through four forms of learning and feedback, namely consumer, enterprise, partner, and social learning.

Secondly, the model outlines the four components of value consensus, sharing, symbiosis, and win–win scenarios, elevating it from a theoretical model to a structural one. For enterprises, it is necessary to build a value ecosystem based on community-centered learning to achieve sustained value appreciation and social penetration. In this three-dimensional, community-centered structural model, consumer learning is a key component at the receiving end of the value flow, ensuring that value is effectively transmitted and absorbed. Corporate learning is the stabilizer of the value system, focusing on preventing a reduction in the existing value. Partner learning is an accelerator for value creation, driving the realization and incremental growth of new value. Finally, social learning spreads the influence of value, achieving widespread value sharing and spillover effects.

Thirdly, this model comprises two levels and analyzes the connection interfaces of the four constituent units in detail. The four types of value form a self-reinforcing loop around the community platform: value transmission is the foundation, value maintenance guarantees that the existing value will be sustained, value realization deepens and creates value, value sharing provides expansion, and the shared results are fed back to the community, stimulating new learning and value cycles. They jointly build a dynamic value co-creation ecosystem, which takes into account the multiple values held by customers, enterprises, partners, and society (such as a desire to meet low-carbon goals), achieving the goal of a value win–win scenario for multi-subject stakeholders.

3.3. Step 3: Strategic Positioning in Uncertain Environments

RRS Logistics adheres to the principle of “organization follows strategy, strategy conforms to The Times” and has gone through four stages of development: enterprise logistics, a logistics enterprise, a platform enterprise, and an ecosystem enterprise. In the face of uncertain environmental changes, it constantly adjusts its strategic positioning and moves forward bravely despite the fierce competition. Value creation is created through complementarity, efficiency, novelty, and locking in [49], while business model innovations can be classified into four types: adjustment, exploration, an all-new approach, and expansion [50]. The influence of RRS Logistics’ business model at different stages was determined by these two dimensions, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The impact of RRS Logistics’ business model at different stages.

Stage one, the enterprise logistics stage (2000–2004): Driven by both technological advancements and demand, RRS Logistics’ response speed, information coordination, and integrated service capabilities were under pressure. This prompted the platform to shift from delivering goods to providing services. RRS Logistics achieved the synchronous coordination of JIT and the three APP networks through data mining innovation and provided integrated services for home appliance supply chains.

Stage two, the logistics enterprise stage (2004–2010): Driven by three factors—technological advancements, demand, and executive awareness—RRS Logistics faced pressure to provide immediate demand satisfaction, integrated services, and information transparency, which prompted the platform to shift from selling services to selling solutions. RRS Logistics established an instant delivery network and fully transparent information network through adaptive innovation, providing supply chain integration services.

Stage three, the platform enterprise stage (2010–2018): With the development of the mobile Internet, the Internet of Things, cloud computing, and big data, the logistics industry was continuously being optimized or upgraded. On the other hand, influenced by changes in consumer demand and competition among logistics enterprises, RRS Logistics was under pressure to improve its core competitiveness, service synchronization, and consumer experience, which prompted the company to transition from being a distribution platform to an interactive one. RRS Logistics achieved the synchronization of the last 1 KM of delivery and installation through expansionary innovation, with the company’s core competitiveness derived from its integration of four networks.

Stage four, the ecological enterprise stage (2018–present): With the rapid development of new technologies such as blockchains, artificial intelligence, and deep and machine learning, the awareness of RRS Logistics’ senior executives has effectively been enhanced. At the same time, influenced by consumers’ personalized demands and the imitative competition among platform enterprises, pressures have emerged due to the consumption scenarios, black box technologies, open ecosystems, and value co-creation, prompting the company to transition from a logistics platform to an ecological one. RRS Logistics has achieved the development of a scenario-based business strategy, smart logistics, and ecological co-creation through an all-new innovation approach and value co-creation.

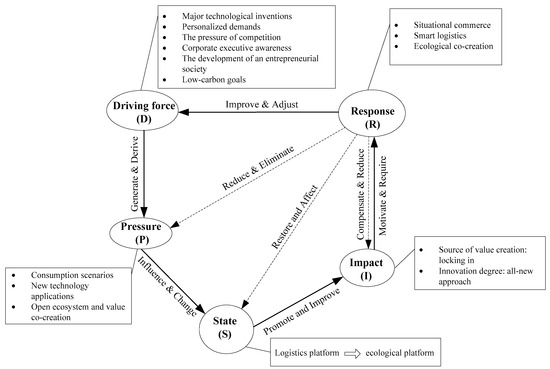

In order to solve the problem of strategic positioning in business model design, we introduce the DPSIR model to solve environmental problems. The DPSIR model (that is, the Driving Force–Pressure–State–Impact–Response model) was proposed by the European Environment Agency (EEA) and originally designed for the development of environmental policies. It is a framework used to describe environmental systems and their interrelationships with human activities. However, some scholars have improved the original DPSIR model to analyze the laws and phenomena of social and economic development. The improved DPSIR model also provides a relatively clear plan, method, and framework for solving system problems, thereby improving the efficiency of policy formulation and implementation for government managers and business owners. The uncertain environment referred to in this article refers to the economic and social environment in which logistics platforms and supply chain systems are located, and we have expanded the connotations of this phrase and the scope of the DPSIR model’s applications. Taking the ecological enterprise stage (i.e., stage four) as an example, the environmental mechanisms of RRS Logistics’ business model are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The environmental mechanisms of RRS Logistics’ business model.

Figure 2 shows that the driving force (D) fosters the development of logistics platform enterprises, promoted by industry factors such as the dual-carbon policy, regulations, and the business environment. In particular, logistics platform enterprises using a large number of trucks and amount of packaging materials have high energy consumption and carbon emissions. Whether these enterprises can achieve green and low-carbon development goals is related to whether the entire logistics industry can achieve them [51]. The pressure (P) refers to the technical barriers, challenges associated with profit indicators, industry competition, and resource scarcity faced by logistics platforms during their development process. The state (S) refers to the development trend of logistics platform enterprises under the combined action of the driving force and pressure, while the impact (I) refers to the positive or negative effect of the logistics platform’s development on multi-subject stakeholders, government management departments, and regional economic development. Finally, the response (R) refers to the measures taken by multiple stakeholders to cope with the pressure and the increased (or reduced) impact of the platform’s development, such as adjusting the strategic direction, improving the service quality and consumer experience, and increasing stakeholder value sharing.

Logistics platform business models based on the DPSIR model have four environmental action paths. The first path is D→P→S→I→R, reflecting a positive effect. The second is R→P, the third is R→S, and the fourth is R→I, all reflecting the reverse effect. This environmental action mechanism effectively solves the problem of uncertainty in designing logistics platform business models and makes them more flexible, agile, and dynamically adaptable to the environment. The innovations in the model introduced in this paper lie in solving the problem of strategic positioning in uncertain environments from a dynamic perspective.

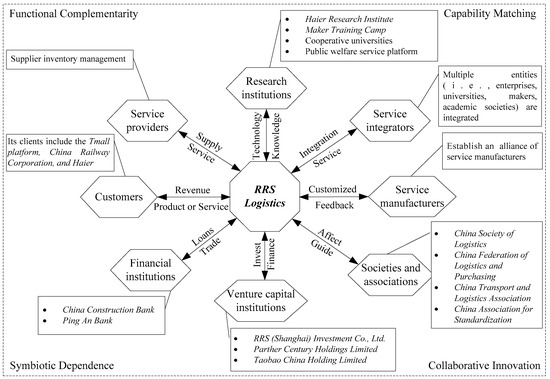

3.4. Step 4: Analysis of Value Co-Creation Among Stakeholders

The general manager of RRS Logistics pointed out that with the development of modern logistics, their business model has shifted from a division-of-labor model to a co-creation one. Special attention should be paid to the community experience provided by the platform and users’ participation in value co-creation. Based on the theory of value co-creation, most of RRS Logistics’ stakeholders have formed a symbiotic system with the company at its center, as shown in Figure 3. The stakeholders of logistics platforms based on value co-creation theory include the logistics platform (as the core enterprise) and other heterogeneous stakeholders, such as customers; service providers, integrators, and manufacturers; financial, venture capital, and research institutions; societies; and associations. These heterogeneous stakeholders are held together through functional complementarity, capability matching, symbiotic dependence, and collaborative innovation.

Figure 3.

The symbiotic system of RRS Logistics.

As shown in Figure 3, there are many stakeholders in a logistics platform system, and a certain relationship is formed between them. The stakeholders of RRS Logistics include service providers, integrators, and manufacturers and customers, such as the Tmall platform, the China Railway Corporation, Ping An Bank, Taobao China Holdings, and the China Society of Logistics. The interaction between the supply of and demand for logistics platforms is a new means of value creation. Value co-creation between core enterprises and customers is the most frequent and important interaction, and it involves one of the main stakeholders. According to their role, customers can be divided into external (users or consumers) and internal customers (employees). Community is the most important way to expand and enhance a user trust base, and the strength of the community function determines the success or failure of business models. Connecting community and ecology is the only way for organizations to grow exponentially.

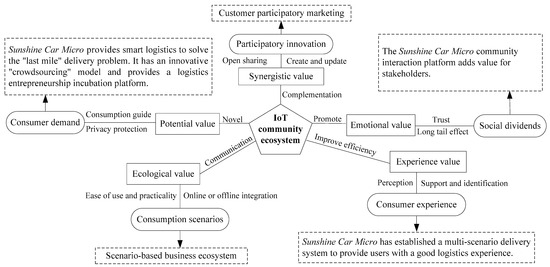

The customer value co-creation experience in virtual user environments includes practical, social, user-friendly, and pleasure-oriented experiences. A virtual community has many functions, including social support and recognition, information exchange, communication and entertainment, privacy and security, and equality and fairness. RRS Logistics regards its most important customers as “online employees” who engage in “zero-distance interaction” and operates the Internet of Things community ecosystem smoothly by providing experience, emotional, ecological, potential, and collaborative value. RRS Logistics’ Internet of Things community ecosystem based on value co-creation is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

RRS Logistics’ IoT community ecosystem based on co-creation.

Figure 4 shows that RRS Logistics has designed a new business model based on five themes: novelty, efficiency, complementarity, locking in, and communication. A subsidiary of the company, RRS Sunshine Car Micro, is a “leading 1 KM” community interaction platform that was established in 2012. This platform provides self-entry, self-order acquisition, self-interaction, and self-optimization functions. It is driven by a full-process system with integrity as its sole evaluation criterion, and its features include in-depth cooperation with others in the industry chain, a logistics “solutions and community” system, direct connections between users and manufacturers, and customized production. The community-based customer value co-creation system provides potential, synergistic, emotional, experience, and ecological value. Here, ecological value also includes the contributions made by enterprises and the entire community to achieve “dual carbon” goals. Therefore, the design of business models for community-centered logistics platforms should emphasize the exploration and fulfillment of consumer demands, encourage participatory innovation, attach importance to social dividends, enhance the consumer experience, and include more diverse consumption scenarios.

3.5. Step 5: Ecosystem Service Cluster Design

Ecosystem services refer to the natural utilities provided and maintained by ecosystems and the ecological processes on which human beings rely for survival. Many scholars have conducted extensive research on ecosystem service theory and applied it to multiple economic and societal fields. Some researchers have empirically studied cloud–AI adoption and resilience strategies in the supply chain and investigated how companies can make their manufacturing supply chains more resilient and sustainable [48]. They have put forward a model of integrated logistics supply chain management based on the theory of commercial ecology, focusing on the mode of transportation and drawing on a multi-attribute behavior decision-making model [52]. We draw on traditional ecosystem cluster theory and the existing research results to extend ecosystem service theory to the field of supply chain management. The business models of enterprises need to match their respective ecosystems. However, in practical operations, ecosystems are often established, but the goal of achieving multi-party value co-creation and service innovation is not achieved. Symbiont-based business models provide good conditions for high-speed, large-scale, and long-term growth [53,54,55]. According to the ecosystem service cluster theory [53,54], a platform can achieve its goal of value creation through interactions among multiple ecosystem services, including supply, regulatory, supporting, and cultural services. The design of RRS Logistics’ ecosystem service cluster is shown in Table 3 and Figure 5.

Table 3.

Design of RRS Logistics’ ecosystem service cluster.

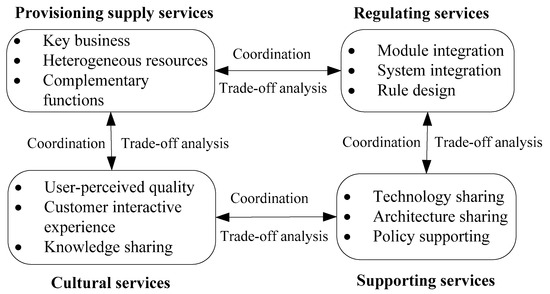

Figure 5.

Ecosystem service cluster design of logistics platform.

Table 3 shows that the competitiveness of the four integrated networks is one of RRS Logistics’ heterogeneous resources. The four networks are the three-level distributed cloud warehouse logistics network, trunk line distribution logistics network, integrated warehousing and distribution service logistics network, and integrated last 1 KM delivery and installation service network.

Figure 5 shows that the ecosystem service clusters are composed of provisioning, regulatory, supporting, and cultural services, with two main relationships of synergies and trade-offs between them. The provisioning services include the key business, heterogeneous resources, and complementary functions, while the regulatory services include module and system integration and standard design. The supporting services include technology and architecture sharing and policy support. Finally, the cultural services include the user-perceived quality, an interactive customer experience, and knowledge sharing. The four types of services are interrelated, forming a collaborative, balanced relationship and ultimately a closed ecological loop.

3.6. Step 6: Ecosystem Envelope Design

In economics, an envelope curve is the long-term average cost curve that is tangent to all the short-term average cost curves; that is, the long-term average cost curve is a curve composed of countless short-term average cost curves. In this paper, we define the ecosystem envelope of a logistics platform based on the concept of the envelope curve, aiming to discuss the necessary conditions for the sustainable development of logistics platform business models based on value co-creation. In the ecosystem of logistics platforms, certain investment costs are required for the construction of a closed-loop O2O interactive and added-value system to improve customers’ experience throughout the whole process and users’ sense of community. Moreover, the investment cost will directly affect the total cost (the sum of each entity’s costs) and total utility (the sum of each entity’s value) of value co-creation in the ecosystem.

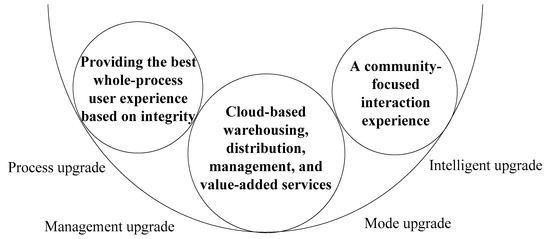

The ecosystem envelope of RRS Logistics is composed of three parts: (1) providing the best whole-process user experience based on integrity; (2) cloud-based warehousing, distribution, management, and value-added services; and (3) a community-focused interaction experience, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The ecosystem envelope design of RRS Logistics.

The ecosystem envelope system of this logistics platform demonstrates flexibility, openness, diversity, loose coupling, conjugated aggregation, and a suitable tension balance. The exceptional customer experience throughout the whole process, closed-loop O2O interactive and added-value system, and community user satisfaction represent a series of short-term cost curves. These short-term curves are like “beads” that intersect with the envelope curve, which form the prerequisite for balanced matching, stable development, cross-border integration, and innovation in logistics platform business models. These prerequisites can also be regarded as the “minimum cost” for the effective utilization of the value co-creation function in a logistics platform ecosystem. In Figure 6, the category of cloud-based warehousing, distribution, management, and value-added services comprises four modules: Cloud warehousing provides integrated big data services and supply chain financial services and relies on the use of intelligent equipment. Cloud distribution offers delivery and installation services for Sunshine Car Micro and the last 1 KM based on trunk and regional networks. The cloud management system is composed of the OMS, BMS, TMS, APP, WMS, etc. Finally, cloud value-added services include GPS, group purchase, consultation, information, and insurance services. The four modules increase the company’s core competitiveness by means of intelligent, model, process, and management upgrades.

3.7. Step 7: Intelligent Supply Chain Innovation

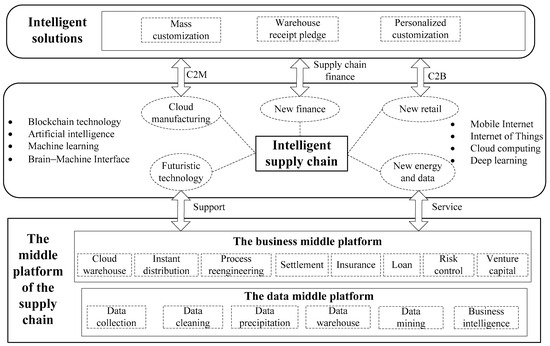

In a logistics platform, we need to establish a closed-loop logistics ecosystem based on the synergistic effects of various logistics nodes in the supply chain, such as manufacturers, suppliers, distributors, retailers, consumers, and vehicles. Moreover, the operation of this ecosystem cannot be separated from an intelligent supply chain. In other words, the most important factor for the smooth operation of a logistics platform system is an efficient supply chain. From a dynamic capability perspective, a nexus of multiple-system integration and business performance can be achieved through supply chain agility and flexibility [56]. An intelligent supply chain uses a combination of Internet and Internet of Things technology and modern supply chain management theories, methods, and technologies to build a set of intelligent, networked, and automated systems integrating the supply chains that connect enterprises and customers. With the development of the mobile Internet, Internet of Things, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and deep learning, the middle platform of the intelligent supply chain supports its smooth operation and provides intelligent solutions. The middle platform performs a powerful core function and, finally, achieves the whole supply chain system’s innovation goal by means of an ecological transition. The design of the logistics platform is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Intelligent supply chain innovation for logistics platform.

Figure 7 shows that the middle platform of the supply chain consists of the business and data middle platforms. The business middle platform comprises cloud warehouses, instant distribution, process reengineering, settlements, insurance, loans, risk control, and venture capital. The data middle platform comprises data collection, cleaning, precipitation, warehouses, and mining and business intelligence. The middle platform of the supply chain supports intelligent supply chain operation using futuristic technology and new energy or data [57]. In the future, the promotion and application of big data, artificial intelligence (AI), virtual reality (VR), and the Metaverse will provide more opportunities regarding supply chain technology [58]. In addition, it will provide intelligent solutions such as mass customization, the warehouse receipt pledge, and personalized customization in cloud manufacturing, new finance, and new retail through C2M, supply chain finance, and C2B, respectively.

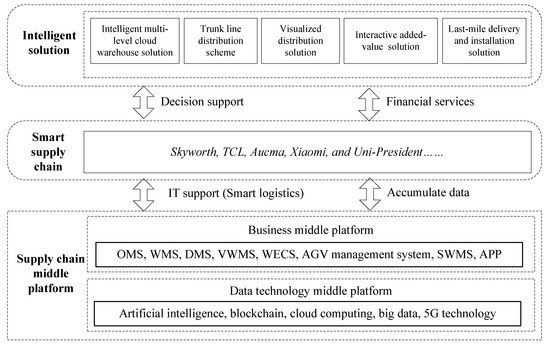

RRS Logistics’ smart supply chain framework has three layers. The supply chain middle platform is composed of data technology and business middle platforms, providing intelligent logistics IT support for the smart supply chain. In turn, the smart supply chain provides intelligent solutions for RRS Logistics’ partners, such as Skyworth, TCL, Aucma, Xiaomi, and Uni-President. These solutions comprise decision support and financial services, as shown in Figure 8. RRS Logistics’ business middle platform includes eight information systems: the order management system (OMS), warehouse management system (WMS), distribution management system (DMS), vehicle storage warehouse management system (VWMS), warehouse equipment control system (WECS), automated guided vehicle (AGV) management system, shelf and workbench management system (SWMS), and mobile application platform (APP).

Figure 8.

RRS Logistics’ smart supply chain framework.

3.8. Step 8: Implementation Effect Verification

RRS Logistics has established a unified after-sales service assessment system, allowing the company to provide systematic training. Its information system provides online customer evaluations, an important basis for service fee settlement. The after-sales service quality can be improved using user satisfaction feedback. RRS Logistics’ marketing emphasizes an interactive experience, while its open ecosystem is evaluated using two criteria: whether there are obstacles to the entry of external resources, and whether all the stakeholders have achieved the maximum benefits.

RRS Sunshine Car Micro has transitioned to a “three-store integration” community economy model with the help of cloud warehouse and distribution systems. It has utilized user interaction scenarios to transform their scattered demands into contextualized ones and established a community interaction platform to divert traffic and provide value-added services. It relies on the Internet of Things to connect express lockers in urban communities, water stations in rural areas, and the Sunshine Car Micro community, and has built a community user interaction platform with its core competitiveness stemming from its integrity. It offers friendly, personalized services and realizes the integration of logistics, an after-sales service, and a scenario-based business model. RRS Sunshine Car Micro’s scenario-based business platform is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

RRS Sunshine Car Micro’s scenario-based business platform.

As shown in Figure 9, RRS Sunshine Car Micro provides heavy cargo logistics services across the entire network and that can reach every village and household. Its unique smart order-grabbing dispatch system and micro-warehouse model effectively connect the urban and rural community ecosystems and allow the company to provide friendly, personalized services based on users’ needs. The company has established an integrity-based ecosystem platform (One Platform) by utilizing a touchpoint network (One Network) and interactive terminals (One Manager), providing customized solutions for a better life. The users’ full-process experience and evaluations are transmitted in real time to each node in the logistics system to enhance the product and service quality. This is an open system that operates in a cyclical manner. RRS Sunshine Car Micro has visualized the logistics experience and explored a new retail service process. After years of operation, RRR Logistics’ platform business model has been verified to be an efficient, user-friendly, and operational solution.

4. The Process of Logistics Platform Business Model Design

4.1. Design Principles

Through design science research, scholars have developed four design principles for business model-based management, namely ecosystem, technology, mobilization, and co-creation-oriented management [48,52]. The design of a logistics platform business model based on value co-creation should follow the principles below.

4.1.1. Systematic Principles

The model should meet the diversified needs of customers in the industrial value chain and provide value creation, sharing, and win–win scenarios for different subjects in this chain. Regarding the logistics platform as a component of the supply chain, all the stakeholders should be regarded as an interrelated whole. The logistics platform business model should unite core enterprises, service providers and integrators, customers, and other stakeholders to the greatest possible extent, and its design should be top-level and from a global system perspective.

4.1.2. Coordination Principles

These principles require that all the components in the supply chain system and the relationships between these individual elements and the system maintain a consistent goal in the process of value creation. Coordination is a prerequisite for ensuring that the system’s functions can be fully utilized and its goals are optimized. Supply chain collaboration (SCC) also benefits organizational performance (OP) [59,60]. Element and thematic design is used to coordinate and connect various components in the activity system [30]. Logistics platforms make rational choices after fully considering internal and external environmental changes, changes in their own capabilities, and the integration of relevant resources.

4.1.3. Goal-Oriented Principles

Designing business models for logistics platforms is a multi-objective activity and should achieve two balances: a balance between users’ needs and enterprise profit goals, and a balance between the consumer experience and enterprise investment costs. These models focus on the driving effect of demand and the feedback effect of benefits and eventually achieve a dynamic multi-objective balance [31].

4.1.4. Dynamic Principles

Business models will dynamically change with changes in uncertain internal and external environments. The impacts of uncertain environments and mechanisms determining these should be paid attention to, and the contradiction between long-term goals and short-term benefits at different stages should be gradually mitigated to promote the platform’s rapid growth and sustainable development. This principle is also reflected in the subsequent general flowchart.

4.1.5. Value Creation Diversification Principles

These have two aspects: First, there are multiple subjects between which to realize value synergy, including core enterprises, service providers and integrators, and customers. Secondly, the types of value that can be acquired are diverse, such as customer, partner, and social value. Here, social value can be provided by the low-carbon business models adopted by platforms in alignment with the national dual-carbon strategy, ultimately achieving the dual goals of energy conservation and emissions reduction as well as enhancing business competitiveness.

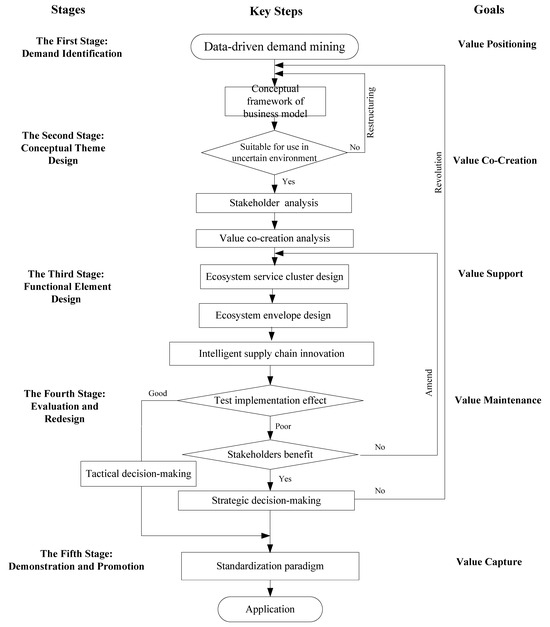

4.2. Platform Design Flowchart

Based on the principles of logistics platform business model design, we integrate digital platforms, value co-creation, low-carbon management, and innovation ecosystems to put forward an overall design process. We attach importance to the dynamic impact of uncertain environments and pay attention to the role of subsequent evaluations and redesign. The general flowchart shown in Figure 10, which illustrates logistics platform business model design, reflects the above-mentioned design principles.

Figure 10.

General flowchart of logistics platform business model design.

As shown in Figure 10, the overall process of logistics platform business model design is divided into five stages: demand identification, conceptual theme design, functional element design, evaluation and redesign, and demonstration and promotion. These five stages correspond to the five goals of value co-creation, namely value positioning, co-creation, support, maintenance, and capture. Value positioning is the starting point of value co-creation. At this stage, the stakeholders jointly explore and determine the scope of value creation and clarify the target customers and value proposition. Value co-creation is the core link. Through the interaction and collaboration of multiple participants, value positioning is transformed into actual value creation activities. Value support involves a guarantee system that provides the necessary resources, tools, platforms, and institutional support for value co-creation activities. Through effective value maintenance, the value creation process can adapt to market changes and maintain the competitiveness of each entity. It is worth mentioning that under the dual-carbon policy, having a low-carbon capacity will affect the strength of logistics platform enterprises’ core competitiveness. Value capture is the goal and reward, ensuring that all the participants can obtain reasonable returns from value co-creation.

March (1991) holds that there are two distinct types of organizational learning, namely the exploitation of the present situation and the exploration of the future [61]. Some researchers extend this distinction to an enterprise’s entire decision-making process. Exploitable decisions are those that adapt the existing resources and capabilities to the current environment and are often regarded as tactical. Developmental decisions are those made by enterprises to obtain new resources and capabilities to adapt to a new environment and are usually also regarded as strategic [62]. These decision-making methods have been applied to the logistics platform business model design, as shown in Figure 10. Adjustment refers to the minor optimization of the existing strategies to adapt to a changing environment. Correction refers to the rectification of any errors or deviations discovered to restore the expected performance of the entire logistics system. Transformation refers to a transition from one mode or strategy to another in order to achieve the expected goals. Reconstruction refers to the fundamental redesign of a business model or process to enhance its efficiency or achieve new goals.

5. Discussion

Osterwalder’s definition of a business model indicates that product managers must shoulder the responsibility to provide customers with value-positioned products [63]. In the past, an important principle of business model design was that the entire process should focus on the customer’s perspective, ensuring that products and services could meet customers’ needs and expectations. Based on previous research, the logistics platform design methods proposed in this paper emphasize the provision of value-added services for customers but also take into account the importance of value co-creation for all stakeholders, ultimately achieving a win–win scenario for all the parties involved. Compared with other existing business models, the innovations in the model proposed in this paper include the following: Firstly, a relatively rigorous logical concept was established. The design of logistics platform business models with a focus on value co-creation is based on the logic of “value positioning–value co–creation–value support–value maintenance–value capture” and starts with demand identification, focusing on conceptual theme and functional element design. Secondly, the dynamic impact of the environment was fully considered. Dynamic changes in an uncertain external environment should always be monitored, and new environments should constantly be reviewed and adjusted to. A logistics platform business model could be made more compatible with the environment, adaptable, and dynamic by adjusting, revising, transforming, and restructuring it. Thirdly, an innovative design method employing multidisciplinary integration was adopted. The design of logistics platform business models should apply interdisciplinary theories and methods from fields such as environmental science (DPSIR model), economics (stakeholder analysis and envelope curve), ecology (ecosystem service clusters), and information science (supply chain middle platforms).

The study results reveal the following key factors of logistics platform design: Firstly, maintain extensive connections. Based on the connections between products and services, the isolated innovations of stakeholders can be connected, thereby achieving common benefits and value co-creation. Secondly, pay attention to the dynamic environment. The challenges that arise in an uncertain environment involve macroeconomics, customer demand, market competition, and the enterprise lifecycle. The logistics platform’s dynamic evolution should be analyzed to further maintain the adaptability of its design. Thirdly, at the core of the model is community. We aim to strengthen the consumer experience, provide products or services that meet the whole community’s needs, and meet the low-carbon requirements. Finally, in many countries or economies, achieving carbon neutrality has become a basic requirement for the sustainable development of enterprises. Logistics platform enterprises that proactively achieve their carbon neutrality goals can not only receive policy support but also win the trust of the market and investors. Therefore, in the process of logistics platform business model design proposed in this paper, we consider carbon neutrality as not only a constraint but also a concrete manifestation of social and ecological values.

We put forward a method for designing logistics platform business models based on value co-creation and outlined the key steps, including strategic positioning in uncertain environments, ecosystem service cluster and envelope design, and intelligent supply chain innovation. We proposed a structural framework of business models based on value co-creation. That is, the community is at the center; there are four elements: value consensus, symbiosis, sharing, and win–win scenarios; and the framework displays “4-4-14” characteristics. We provided theoretical integration and improvements based on the existing theories and cases, and new design methods and steps were proposed. In this paper, we combined modularization theory [45] with business model design. The structural business model was regarded as a modular system, which could be decomposed into three layers: unit, structural, and functional modules. With the continuous development of technology and constant changes in the external environment, this “modular” approach allows modules to be added or improved and the connections between them to be changed, thereby enabling the transformation of the business model. The advantage of this method lies in its combination of modular theory and business model design, providing a new approach to researching the latter. The main disadvantage is that it does not include all the business model modules used in the real world. From this perspective, establishing a set of modules that can constitute various business models will be a difficulty task to address in future research.

Some logistics companies have already achieved effective value creation for stakeholders by designing business models emphasizing value co-creation, the consumer experience, and positive interactions between producers and consumers [64]. These emphases are consistent with those of the business model proposed in this article. For example, while providing transaction matching services, Full Truck Alliance pays close attention to drivers’ quality of life and community consumption and provides comprehensive value-added services, such as discounted car purchases, ETC, refueling, and financial insurance. After three years of using a value co-creation business model, the revenue of Full Truck Alliance had increased from CNY 4.66 billion in 2021 to CNY 11.24 billion in 2024. The growth rates for these three years were 44.4%, 25.4%, and 33.2%, respectively, with an average of 34.3%. This indicates that the company’s value co-creation business model has contributed to its substantial growth. Logory Logistics Co. Ltd. has designed three mutually driven business models centered around truck drivers and focusing on business, production, and drivers’ quality of life; it also provides non-truck-operated common carrier services, credit services, and financial services. It has built a new service ecosystem and created a vertical community of 15 million truck drivers, with CNY 4.6 trillion generated by its non-truck-operated common carriers and CNY 2 trillion by its aftermarket support [65]. These data and case studies further support the viewpoints put forward in this article. Of course, we also acknowledge that the growth of a company’s performance is influenced by many factors, including not only internal ones such as business models and talent structures but also external ones such as politics and the law, economic cycles, and technological progress. Regarding the logistics platform business models proposed in this article, these internal and external factors had already been taken into consideration during the design process. Conversely, if a logistics platform company chooses an unreasonable business model, it is inevitable that it will face difficulties or even fail after several years of operation.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Conclusions

Based on an in-depth analysis of logistics platforms’ key characteristics according to standardized design principles and processes, the concept, method, key steps, and innovation mechanisms of the new logistics platform business model design are explored in this paper. The main conclusions are summarized as follows.

Firstly, in the process of designing logistics platform business models, the key characteristics of the platform, such as its multilateralism, openness, supply–demand matching, network externality, and user orientation, need to be considered. In business model design, customer demand should always be the guiding principle, and the connectivity between different entities and their sustainability should be considered. In addition, it is also necessary to adjust the platform’s structure dynamically in response to changes in the internal and external environment.

Secondly, logistics platform business model design should follow standardized design processes. Key steps include the construction of the business model concept, strategic positioning in uncertain environments, an analysis of value co-creation between stakeholders and customers, ecosystem service cluster and envelope design, innovative smart supply chain design, and implementation effect testing.

Thirdly, ecosystem service clusters and envelopes are key elements in business model design and innovation. Ecosystem service cluster design based on value co-creation has a strong focus on supply, regulatory, support, and culture services. Ultimately, the goal of the cross-border integration of business model design and innovation is achieved to the greatest extent in the form of an ecosystem envelope.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The findings of this study have the following important implications for the design and implementation of logistics platform business models.

Firstly, a unique and innovative business model design is a key factor in the sustainable development of logistics platforms. Different types of novel logistics platforms are constantly emerging. However, these platforms face issues such as homogeneous competition and unclear value goals. In order to present a relatively clear business model and achieve the goal of creating value on these platforms, it is necessary to examine the effects of logistics platform business model design. Specifically, for logistics platforms such as C2B, C2M, and S2B that have emerged in the new retail market, innovative business model design is a prerequisite for their development in increasingly competitive environments. Therefore, in this study, we have provided standardized and practical tools and methods.

Secondly, designing different business models based on value co-creation is the best solution for future logistics platforms to survive and develop sustainably. The logistics platform business model design method proposed in this paper focuses on the community-centered analysis of customer value co-creation and emphasizes collaborative innovation and value win–win scenarios for stakeholders. Based on the core logic of obtaining multiple types of value for customers, enterprises, partners, and society, we fully tap into the potential of utilizing heterogeneous interactions in communities and build a community-centered stakeholder innovation ecosystem with complementary advantages and symbiotic dependence. This further strengthens the operability of business model design and the sense of identity of different entities.

Thirdly, in the process of designing a business model, it is necessary to strike a balance between standardization and dynamic adjustment. Information management (IM) significantly and positively affects the supply chain performance (SCP). When an uncertain external environment dynamically changes, it is necessary to allocate and optimize resources reasonably, improving the quality and efficiency of information sharing. Thus, we can dynamically design business models using various methods such as adjustment, correction, transformation, and reconstruction to achieve a balance between efficient and innovative design.

Fourthly, logistics platform business model design should focus on functional elements such as ecosystem service clusters, ecosystem envelopes, and intelligent supply chains, considering multiple dimensions including supply, consumer experience, and technological developments. In addition, we should constantly check whether these are coordinated with the needs of the market and customers. If not, it is necessary to apply cyclic or parallel design to make adjustments in a continuous and dynamic manner.

Fifthly, the value co-creation-based business model design process and steps proposed in this article are not only applicable to multiple types of logistics platforms but can also be extended to other platforms with obvious community interaction characteristics, such as e-commerce, e-government, and online tourism platforms. The design framework and methodology proposed in this article provide a necessary reference for these platforms’ professional managers and operational directors regarding business model design.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This research has some limitations. The overall theoretical logic of the article used to study logistics platform business model innovations is based on the existing theories and the case of RRS Logistics. Both the research field and this study are limited to examining logistics platform business models. Although many theories have been cited in this paper, including modularization, innovation ecosystem, value co-creation, and supply chain management theories, these theories interconnect and influence each other, which is not discussed in depth in this paper. Additionally, the cohesion and integration of various basic theories can be further improved to form a systematic theory. For instance, the selection of a “4-4-14” structure is not a given, and not all the related factors can be considered, which leads to certain differences between the established model and actual situation.

Furthermore, the main viewpoints and methods presented in this paper are based on a summary of the development of some logistics platform enterprises in China. Case studies of more logistics platform companies are still needed to demonstrate their correctness and operability. The research results for a few cases do not necessarily guarantee the accuracy and completeness of the proposed models and methods. The assessment of a business model’s feasibility and sustainability still faces multiple challenges, including the need for long-term monitoring and analysis of a large number of logistics platform enterprises.

In addition, transforming a new theory into effective rules or guidance is also a challenge. This study mainly presents theories and methods and does not include detailed guidance. For a specific logistics platform company, analysis will need to be performed and a reasonable judgment made based on the actual situation.

Moreover, some concepts and specialized terms used in the text have different definitions in different fields. If feasibility testing or iterative validation can be conducted in combination with the presentation of case studies, this will better support the viewpoints proposed in this manuscript. In the future, we will analyze the business models of more logistics companies from a wider range of regions, thereby improving our proposed methods. In addition, the evaluation and analysis of business models in different industries will also be important in future research. We can also discuss the relationship between different business models’ innovation capabilities and companies’ performance indicators, as well as that between the factors influencing logistics platform business model innovation.

Author Contributions

K.H.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing, project administration; F.W.: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, review and editing; J.B.: validation, data curation, supervision, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Province Social Science Foundation under Grant [21NDJC182YB].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This article thanks Liu W.H. of Tianjin University for his careful guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cote, M.A.A.; Polanco, D.F.S.; Orjuela-Castro, J.A. Logistics platforms trends and challenges. Acta Logist. 2021, 8, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.F.; He, Y.Y.; Ji, Q. Collaborative logistics network: A new business mode in the platform economy. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 25, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.Z.; Bai, L.; Jiang, F.; Yin, S. Subsidy strategy of sharing logistics platform. Complex Syst. 2023, 9, 2413–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Pan, Q.H. Research on value creation path of logistics platform under the background of digital ecosystem: Based on SEM and fsQCA methods. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 67, 101424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co–creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 3, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Zhang, H.L.; Wang, Y.W. An improved adaptive propagation chaotic particle swarm optimization algorithm based on immune selection. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC 2017), Ningbo, China, 9–12 July 2017; pp. 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G.Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, S.H. Theory and Practice of Logistics Public Information Platform; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Zhu, J.J. Comparative study on business models of multi-type “Internet plus” logistics innovation platform. China Bus. Mark. 2019, 8, 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, S.; Blomquist, T. Business model design in the case of complex innovations: A conceptual model. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 33, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, A.; Ulaga, W.; Schultz, F. Value creation in the relationship life cycle: A quasi-longitudinal analysis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 1, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.G. Business models: A discovery driven approach. Long Range Plan. 2010, 2, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. Closing the marketing capabilities gap. J. Mark. 2011, 4, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.; Chen, S.P. Research on business models design for the small sized high-tech enterprises based on value creation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2013, 18, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott, D.; Lowi, A.; Ticoll, D. Digital Capital-Harnessing the Power of Business Webs; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changes, and Challengers; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turienzo, J.; Blanco, A.; Lampón, J.F.; Muñoz-Dueñas, M.D. Logistics business model evolution: Digital platforms and connected and autonomous vehicles as disruptors. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 9, 2483–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Guerraz, S.; Finn, A.M. Business models for technology in the developing world: The role of non-governmental organizations. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2007, 2, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Strategy in changing markets: New business model-creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, O.; Kittl, C.; Teksten, R.D. Developing Business Models for Ebusiness; Social Science Electronic Publishing: Rochester, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Papakiriakopoulos, D.; Poulymenakou, A.; Doukidis, G. Building e-business models: An analytical framework and development guidelines. In Proceedings of the 14th Bled Electronic Commerce Conference, Bled, Slovenia, 25–26 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, C.; Follack, M. Using action research for gaining competitive advantage out of the internet, s Impact on existing business models. In Proceedings of the 15th Bled Electronic Commerce Conference eReality: Constructing the eEconomy, Bled, Slovenia, 17–19 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gordijn, J.; Akkermans, J.M. Value-based requirements engineering: Exploring innovative e-commerce ideas. Requir. Eng. 2003, 8, 114–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.L.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, H.F. Intermediary effect of typical characteristics of business model on business performance: Based on perspective of enterprises key resource. Technol. Econ. 2015, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Normann, R.; Ramirez, R. From value chain to value constellation: Designing interactive strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lush, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granstrand, O.; Holgersson, M. Innovation ecosystems: A conceptual review and a new definition. Technovation 2020, 90–91, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, A.; Weking, J.; Schreieck, M.; Wiesche, M.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. Value co-creation practices in business-to-business platform ecosystems. Electron. Mark. 2019, 29, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.; Vafeas, M.; Hilton, T. Resource integration for co-creation between marketing agencies and clients. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 1329–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.F.; Xu, J.; Liang, X.H. Scale development of inter-enterprises value co–creation based on dart model. Jinan J. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2014, 4, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh, S.K.; Jayaraman, K.; Ismail, I.; Rahman, S.A. Scale development and validation for DART model of value co-creation process on innovation strategy. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Jaakkola, E. Value co–creation in knowledge intensive business services: A dyadic perspective on the joint problem solving process. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpen, I.O.; Bove, L.L.; Lukas, B.A.; Zyphur, M.J. Service-dominant orientation: Measurement and impact on performance outcomes. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenroos, C. Marketing as promise management: Regaining customer management for marketing. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2009, 24, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.; Andreu, L.; Cervera, A. Value co–creation among hotels and disabled customers: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 5, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, V.; Goyal, P.; Jebarajakirthy, C. Value co-creation: A review of literature and future research agenda. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.M.; Wang, S.Y.; Wu, X.L. Concept refinement factor symbiosis and innovation activity efficiency analysis of innovation ecosystem. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1942026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.Z.; Hu, L.Y.; Zhang, H.J.; Hou, C.X. Innovation ecosystem research: Emerging trends and future research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.J. How to design business models to adapt to the environment? Theoretical framework from the perspective of CAS. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2015, 12, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, K.X.; Xue, H.B.; Yang, J.; Hu, W.B. The study on business models from the cognitive perspective: A literature review and construction of research framework. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2016, 5, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.F. Study on the technology collaboration innovation platform for regional port logistics industry. Logist. Sci-Tech 2013, 7, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.W.; Cui, L.G. Theoretical and empirical studies. R&D Manag. 2016, 4, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.D. Research on the model of innovation in 3PL’s service quality management based on cloud computing. China Bus. Mark. 2015, 2, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Magretta, J. Why business models matter. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 5, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Spens, K.; Kovács, G. Mixed methods in logistics research: The use of case studies and content analysis. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, P.; Vitale, M.R. Place to Space: Migrating to E-Business Models. Master’s Thesis, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, R.; Keskin, D.; Kirkels, A.; Romme, A.G.L.; Huijben, J. Design principles for sustainability assessments in the business model innovation process. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.Q.; Xiao, X. Services innovation and value co–creation under networked environment: A case study of Ctrip. J. Ind. Eng./Eng. Manag. 2015, 1, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business model Design: An Activity System Perspective. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value creation in e-business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.; Williander, M. Circular Business Model Innovation: Inherent Uncertainties. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Lu, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, M.; Dulebenets, M.A.; Aleksandrov, A.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Ivanov, M. A survey of multi-criteria decision-making techniques for green logistics and low-carbon transportation systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 57279–57301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y. Research on Evolution Mechanism and Service Mode of Regional Science and Technology Resource Sharing Platform; Harbin University of Science and Technology: Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kareiva, P.; Watts, S.; McDonald, R.; Boucher, T. Domesticated nature: Shaping landscapes and ecosystems for human welfare. Science 2007, 316, 1866–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudsepp-Hearne, C.; Peterson, G.D.; Bennett, E.M. Ecosystem service bundles for analyzing tradeoffs in diverse landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5242–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.L.; Peng, J.; Hu, Y.N.; Wu, W.H. Ecological function zoning in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region based on ecosystem service bundles. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 28, 2657–2666. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.; Rasheed, R.; Ngah, A.H.; Marjerison, R.K. A nexus of multiple integrations and business performance through supply chain agility and supply flexibility: A dynamic capability view. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Rasheed, R.; Tanveer, U.; Ishaq, S.; Amirah, N.A. Mediation of integrations in supply chain information management and supply chain performance: An empirical study from a developing economy. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, I. Implementation of an intelligent supply chain control tower: A socio-technical systems case study. Prod. Plan. Control. 2023, 15, 1415–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandarpour, M.; Dejax, P.; Miemczyk, J.; Péton, O. Sustainable supply chain network design: An optimization-oriented review. Omega 2015, 54, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Rasheed, R.; Amirah, N.A. Information technology and people involvement in organizational performance through supply chain collaboration. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2024, 15, 1560–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Ricart, J.E. How to design a winning business model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Weihua, L.; Di, W.; Xinran, S. The impacts of distributional and peer-induced fairness concerns on the decision-making of order allocation in logistics service supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 116, 102–122. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.Y. Research on the Evolution Mechanism and Value Creation of Logistics Platform Cooperation Based on Business Ecosystem; Shanghai Maritime University: Shanghai, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.G.; Yu, S.W.; Zhang, T. Redefining Logistics: Logistics Transformation Driven by Products, Platforms, Technology and Capital; China Economic Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).