Abstract

In the era of shifting global economic dynamics and rapid digital transformation, the demand for enhanced corporate innovation capabilities has significantly increased. However, workplace ostracism, which often arises in complex organizational contexts, may trigger employees’ creative territory behavior, thereby undermining the organization’s innovation ecosystem. There is a need for further research on mitigating the negative impacts of workplace ostracism. Drawing on Affective Events Theory, this study adopts the perspective of enhancing individuals’ perceived coping resources and conceptualizes fun activities as a form of indirect support created by the organization. It further develops a mediated moderation model to examine how fun activities buffer the impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ creative territory behavior by mitigating their fear of missing out. Using a two-wave questionnaire survey, this study collected 337 valid responses from Chinese employees and conducted a hierarchical regression analysis with SPSS. The results reveal that fun activities perform a dual role: directly, they can mitigate employees’ fear of missing out triggered by workplace ostracism; indirectly, they can weaken the impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ creative territory behavior by alleviating such apprehension. This study offers theoretical insights for organizations on integrating ostracism governance into their organizational management systems and on alleviating the adverse outcomes of workplace ostracism by fostering an environment of indirect support.

1. Introduction

Amid the backdrop of the profound restructuring of the global economic landscape and the acceleration of digital transformation, innovation has become the key driver for enterprises to build sustainable competitive advantages [1], necessitating the refinement of sustainable development mechanisms and innovation management systems [2]. As fundamental micro-level components of organizational innovation ecosystems, knowledge exchange and cross-pollination of ideas among employees play a crucial role in shaping an organization’s innovation momentum [3,4]. Empirical studies have shown that positive interpersonal relationships and social interactions among colleagues are important factors in promoting individual innovation within organizations [5,6,7]. However, workplace ostracism, a common interpersonal stressor in organizational settings [8], has been widely confirmed to inhibit employees’ knowledge sharing and innovation [9,10,11,12]. Given the detrimental impact of workplace ostracism on organizational innovation, exploring practical management strategies to address this issue has become a shared priority for both academia and industry. In today’s workplace, optimizing the balance between work and leisure to enhance interpersonal relationships has become a prevailing trend [13]. Can fun activities in the workplace serve as an effective intervention to buffer the negative impacts of workplace ostracism? This question urgently requires in-depth theoretical and empirical exploration.

Workplace ostracism may activate individuals’ psychological defense mechanisms [14]. From a resource perspective, ostracism depletes personal resources [15], prompting employees to adopt defensive strategies to protect their remaining resources [16], such as withdrawing beneficial behaviors and attitudes toward the organization [17]. Furthermore, workplace ostracism often triggers a sense of negative reciprocity [18], motivating victims to engage in “tit-for-tat” retaliation [19]. In such cases, ostracized employees may deliberately provide inaccurate information or withhold critical knowledge to restore their sense of fairness against the source of exclusion [20]. Thus, employees experiencing workplace ostracism may adopt either self-protective or retaliatory measures to achieve “psychological self-consistency”, reducing discomfort and restoring psychological equilibrium. Guided by this mechanism, they may engage in creative territory behavior. Creative territory behavior refers to the act of protecting creative resources from damage or infringement through marking and defensive behaviors, such as patenting ideas or refusing to share personal experiences and creative ideas [21]. Previous studies have shown that such exclusive possession behaviors are detrimental to interpersonal collaboration and resource exchange, ultimately hindering improvements in organizational innovation efficiency [21,22]. Therefore, breaking this negative psychological consistency process and weakening the impact of workplace ostracism on creative territory behavior have become important issues. However, research on the boundary conditions that can alleviate the negative effects of workplace ostracism remains limited [23].

Different individuals may respond differently to the same stressful situation due to variations in personal resources, experiences, and cognitive frameworks [24]. After experiencing workplace ostracism, employees’ coping strategies depend on their perceived availability of personal and organizational resources [8]. Current research has largely focused on the role of direct support from leaders, colleagues, and the organization [12,25,26], while neglecting the importance of indirect support. Informal networks among employees play a crucial role in providing access to key resources such as information and psychological support [27]. Fun activities refer to various social and group events initiated by the organization to create enjoyable and pleasant experiences for employees [28]. These activities offer opportunities for social interaction beyond work tasks, helping employees expand their social networks and access social support resources [29,30]. Additionally, they provide new channels for knowledge and information exchange [31], which can assist employees in coping with work-related stress [32]. Consequently, fun activities can be regarded as an indirect supportive environment fostered by the organization. These activities may reshape employees’ cognitive appraisal of available resources, influencing their responses to exclusion and weakening the negative impact of workplace ostracism.

Moreover, Affective Events Theory posits that individuals’ emotional reactions mediate the relationship between workplace events and employees’ attitudes/behaviors, and that these emotional responses are shaped by cognitive appraisals (i.e., evaluations of event relevance and the perceived adequacy of coping resources) [33,34]. Therefore, the moderating effect of fun activities on the relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ creative territory behavior may operate through employees’ emotional responses. Prior research has demonstrated that workplace ostracism can trigger employees’ workplace fear of missing out (FoMO) [35]. Workplace FoMO refers to a pervasive apprehension stemming from the fear of missing valuable work-related opportunities [36,37]. This apprehension can drive employees to adopt defensive strategies to enhance resource control and protection [38,39], which has been shown to negatively affect work behaviors and performance [40,41,42]. For employees who frequently participate in fun activities, although exclusion may imply some resource loss [43], they can still gain information and social support through informal networks built during these activities. These may help alleviate their concerns about losing information and relationships due to ostracism, thereby reducing the likelihood of engaging in creative territory behavior. Building on these insights, this study incorporates workplace FoMO into the theoretical framework to further explore the mechanism through which fun activities mitigate the adverse effects of workplace ostracism.

In conclusion, in the context of innovation-driven development and considering the negative impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ innovation, this study draws on Affective Events Theory and adopts the perspective of enhancing individuals’ coping resource appraisals by viewing fun activities as a form of indirect organizational support. By innovatively introducing fun activities as a moderating variable, this study investigates their buffering effect on the negative relationship between workplace ostracism and creative territory behavior. The findings contribute a novel theoretical framework for understanding the interpersonal antecedents of creative territory behavior, and offer practical insights for organizations seeking to mitigate the negative effects of workplace ostracism and cultivate a healthy innovation ecosystem.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Moderating Effect of Fun Activities

Ostracism refers to the extent to which individuals perceive being ignored, excluded, or rejected by others [44]. Typical manifestations include withholding information, responding indifferently, and avoiding interaction [45]. As research on this concept has advanced, ostracism has been introduced into workplace studies, giving rise to the notion of workplace ostracism. Workplace ostracism refers to employees’ perceptions of being ignored or excluded in the workplace, representing a distinctly subjective experience and judgment [46]. Common manifestations include being deliberately ignored, treated coldly, refused responses, avoided, or having one’s feelings and needs disregarded by others [47]. Existing studies suggest that workplace ostracism constitutes an interpersonal stressor in organizational contexts [48], negatively influencing individuals’ psychological states and behaviors [9,49,50].

According to Affective Events Theory, workplace events can trigger employees’ affective reactions, which will in turn shape their attitudes and behaviors. These affective responses depend on individuals’ cognitive appraisal of work events, when events are perceived as conflicting with personal goals or values and exceeding one’s coping resources, emotional reactions are likely to occur [33,34].

Workplace FoMO refers to a pervasive apprehension stemming from the fear of missing valuable work-related opportunities. It typically involves concern over missed chances for gaining beneficial experiences such as building professional relationships and obtaining valuable information [36,37]. Research has shown that restricted access to information and impaired interpersonal networks caused by workplace ostracism can trigger employees’ workplace FoMO [35]. In the Chinese traditional “relationship-oriented” cultural context, establishing and maintaining workplace relationship networks is often viewed as a crucial means for achieving career development [51]. This cultural orientation makes employees particularly reliant on social capital for acquiring resources and support. However, workplace ostracism severs excluded employees from the organization’s social network, reducing their opportunities for interaction [52] and restricting their access to essential support and critical information from colleagues [12,53,54]. As a result, employees may become anxious about missing important career advancement opportunities.

Furthermore, workplace ostracism may threaten individuals’ sense of personal worth. Because ostracism typically conveys negative social feedback, it can lead employees to feel undervalued by the organization, generating negative self-worth perceptions [55,56] and lowering self-esteem [57,58]. Individuals with low self-esteem are more likely to engage in upward social comparisons, striving to gain advantages relative to successful peers [59]. This tendency may intensify worries about missing out on essential work-related information and professional networks [60]. Therefore, we predict that workplace ostracism is positively associated with employees’ workplace FoMO.

In line with Affective Events Theory, individuals’ cognitive appraisals of workplace events also involve assessing the adequacy of their coping resources [33]. The workplace FoMO resulting from workplace ostracism may partly stem from individuals’ negative evaluations of their own coping capabilities (e.g., psychological resilience, interpersonal relationships, information resources). Fun activities refer to various social and group events initiated by the organization [28]. These activities not only provide enjoyable experiences [61,62], but also offer opportunities to expand social networks [63,64]. These benefits enhance employees’ positive self-appraisals regarding the sufficiency and accessibility of psychological, relational, and informational resources, potentially mitigating the FoMO triggered by workplace ostracism.

First, compared to those in low-fun-activity environments, employees in high-fun-activity contexts are more likely to experience positive emotions through participation, thereby enhancing their psychological capital [65]. Increased psychological capital enables individuals to adopt a proactive approach to workplace stress and challenges while maintaining an optimistic outlook on career development [66], thereby alleviating excessive concerns about missing professional opportunities. Second, fun activities provide platforms for expanding social networks [67], promoting friendships and interpersonal trust among employees [68]. In high-fun-activity settings, employees can not only display their competencies for impression management through collaboration or competition, but also establish cross-level and cross-departmental connections via informal interactions (e.g., exchanging contact details with senior leaders at parties or establishing affective connections with cross-departmental members during walks). Such experiences improve individuals’ positive evaluations of their accumulated social resources, alleviating fear of missing networking opportunities due to ostracism. Finally, fun activities offer informal learning opportunities [69] and alternative information channels [70], helping excluded employees overcome informational barriers and learn the coping strategies from colleagues in different departments [71], thus enhancing their perceived adequacy of coping resources.

In conclusion, fun activities can strengthen employees’ coping efficacy by enriching three key resource domains (psychological, relational, and informational), which helps to mitigate the workplace FoMO induced by workplace ostracism. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 1.

Fun activities will moderate the relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ workplace FoMO such that the positive relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ workplace FoMO will be weaker when the level of fun activities is high compared to when it is low.

2.2. The Mediated Moderation Effect

The concept of territorial behavior originated in biological studies, where it was initially used to explain animals’ protective actions aimed at defending their living spaces from intrusion by others. In the 1970s, scholars gradually recognized that humans also exhibit territorial tendencies [72]. In 2005, Brown et al. introduced territorial behavior into organizational behavior research, defining it as actions arising from an individual’s psychological ownership of physical or intangible objects, intended to establish, assert, maintain, or restore their attachment to these target objects [73]. As research on territorial behavior progressed, scholars began to identify territorial behaviors related to knowledge and creative ideas within organizations.

Creative territory behavior refers to a set of actions individuals undertake to safeguard their creative ideas from damage or infringement. These behaviors include constructing the boundaries around the creative domain, asserting ownership of ideas, maintaining control over ideas, and re-establishing dominance over the creative territory when necessary [21]. This concept reflects employees’ emphasis on protecting their intangible resources [74], and represents a strategic choice aimed at preserving competitive advantage and psychological balance, often with a certain degree of concealment [75]. As an extension and expansion of territorial behavior, the academic research on creative territory behavior remains in its early stages. Existing studies on its antecedents are limited, focusing primarily on leadership styles [74,76]. Brown (2009) suggested that interpersonal relationships with colleagues might be a critical factor influencing territorial behavior [77]. However, this relationship remains underexplored, and its internal mechanisms are not yet fully understood.

Prior research has found that FoMO can induce rumination, causing individuals to unconsciously and repeatedly dwell on negative experiences and emotions, making it difficult to get rid of these disturbances [78]. Such persistent negative emotions deplete individuals’ psychological resources. To prevent further depletion, employees may reduce their work engagement as a means of achieving psychological balance [79]. Furthermore, when creative ideas are disclosed or shared, there is a risk of idea theft or infringement. Individuals experiencing heightened negative emotions often exhibit reduced risk tolerance and are more inclined to adopt avoidance-based coping strategies [80], such as withholding creative ideas. This is consistent with the findings of Zoonen et al. (2022), who observed that employees with a high level of FoMO tend to gather more information on enterprise social platforms but do not necessarily increase content-sharing behaviors [81].

Guided by Affective Events Theory, which posits that individuals’ affective reactions mediate the relationship between workplace events and their subsequent attitudes and behaviors [33,34], we propose that workplace FoMO may mediate the relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ creative territory behavior. Specifically, workplace ostracism limits information access and disrupts social networks, which can easily trigger employees’ FoMO on career opportunities. This fear, in turn, motivates employees to engage in creative territory behavior to protect and control their resources, thereby reducing potential risks of loss.

Moreover, in combination with Hypothesis 1, we propose an integrated mediated moderation model, suggesting that workplace FoMO mediates the moderating effect of fun activities on the relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ creative territory behavior. Specifically, when organizations offer a variety of fun activities, employees are more likely to conveniently gain access to multidimensional social capital, including psychological support, interpersonal connections, and informational resources, through informal networks. This enhanced resource availability can foster a positive cognitive appraisal of “resource sufficiency” in coping with ostracism, thereby alleviating employees’ FoMO and preventing them from overly concerning about missing career opportunities. As a result, employees become more inclined to respond to ostracism in constructive rather than defensive ways.

Furthermore, the diverse social networks formed through fun activities, including cross-team, cross-departmental, and cross-level connections, provide employees with richer channels for resource acquisition. These expanded networks can effectively alleviate their FoMO caused by social isolation and information asymmetry, encouraging employees to transcend exclusionary contexts and engage in creative exchanges and collaborative innovation with a broader peer group beyond the ostracizers. In contrast, in low-fun-activity environments, employees facing resource threats from ostracism (e.g., restricted relationships and limited information access) have fewer informal opportunities to obtain resources, resulting in higher FoMO. This will heighten employees’ defensive tendencies, reinforcing the closure of creative boundaries. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2.

Workplace FoMO will mediate the moderating effect of fun activities on the relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ creative territory, such that when the level of fun activities is high, the impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ FoMO will be weaker than when it is low, thereby leading to a weaker effect of workplace ostracism on their creative territory behavior.

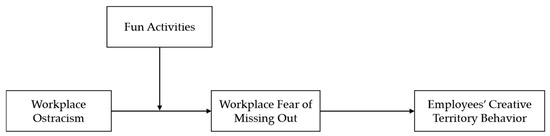

In summary, this study constructs the theoretical model shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Sample

Following the general paradigm of prior empirical studies, this study employed a questionnaire survey method for data collection. Utilizing the social networks of alumni and current employees, questionnaires were distributed and collected both online and offline. To reduce the potential impact of common method bias and enhance the robustness of the research findings, drawing on prior studies [82,83,84], we adopted a two-wave research design. Podsakoff et al. (2012) emphasized the importance of selecting an appropriate time-lag interval, avoiding intervals that are too short (which may artificially inflate variable associations due to memory effects) or too long (which may obscure true relationships due to the influence of extraneous factors) [85]. Based on this guidance and drawing on previous studies [20,41,86], a two-week interval was deemed appropriate.

At Time 1 (T1), respondents were invited to answer questions related to workplace ostracism, fun activities, and demographic characteristics; at Time 2 (T2, two weeks later), the same respondents were invited to answer questions related to workplace FoMO, employees’ creative territory behavior, and demographic characteristics. The pairing of responses from the two waves was achieved using the last four digits of participants’ mobile phone numbers along with their demographic information.

A total of 475 questionnaires were collected at Time 1. At Time 2, 433 questionnaires were returned by respondents who had completed the first wave. After data collection, the researchers matched and integrated the collected questionnaires. Questionnaires with inconsistent pairing information were excluded, resulting in 392 valid matched pairs. Subsequently, incomplete or carelessly filled responses were removed, retaining a final sample of 337 valid questionnaires. The overall effective response rate was 70.95%.

The demographic characteristics of the final sample were as follows: (1) Gender: Males accounted for 45.99%, while females accounted for 54.01%. (2) Age: The most significant proportion (38.58%) was aged 25 or younger, followed by 26–35 years (35.61%), 36–45 years (17.80%), 46–55 years (7.12%), and those above 55 (0.89%). (3) Educational Background: Respondents with a bachelor’ s degree or higher constituted 91.39% of the sample. (4) Marital Status: Unmarried respondents were more prevalent (65.28%) compared to married ones (34.72%). (5) Organizational Tenure: Those with three years or less of tenure accounted for 51.04%, while those with more than three years made up 48.96%. (6) Job Level: The majority were ordinary employees (62.02%), followed by frontline supervisors (26.41%) and middle/senior managers (11.57%). (7) Organizational Type: The most significant proportion worked in private enterprises (45.99%), followed by state-owned enterprises (26.41%), government/public institutions (13.65%), and joint ventures/foreign-owned companies (11.57%).

3.2. Measurement Instruments

This study employed mature scales that accurately reflect the meanings of the variables and are widely used in prior research. A rigorous “translation and back-translation” process of the original English scales to minimize potential misunderstandings arising from cultural differences. All variables, except demographic information, were measured using a five-point Likert scale. The measurement items are presented in Appendix A. Additionally, Cronbach’s α coefficient was used as the reliability indicator, and reliability tests for the four key variable scales were conducted using SPSS 26.0. The analysis results are as follows:

- Workplace Ostracism: This study adopted the unidimensional scale developed by Ferris et al. (2008) [46], consisting of 10 items. A representative item is, “At work, some people ignore my feelings or opinions”. This scale has been widely applied in the Chinese context, with its reliability and validity rigorously confirmed. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in the present study was 0.908.

- Workplace FoMO: This study utilized the FoMO scale created by Budnick et al. (2020) [36], specifically designed for professional settings, comprising two dimensions with a total of 10 items. A representative item is, “I worry that I might miss important work-related updates”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in this study was 0.871.

- Employees’ Creative Territory Behavior: This study employed the scale developed by Brown et al. (2014) [87], which includes two dimensions, claiming behaviors and anticipatory defending behaviors, comprising a total of 6 items. A representative item is, “I will clarify to others which creative ideas are my own”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient reported for this scale was 0.846.

- Fun Activities: In line with previous studies [31,88], this study adopted the fun activities scale developed by Tews et al. (2014) [28], which measures the prevalence of typical and generally beneficial activities. A representative item is, “Team-building activities organized by the organization (e.g., enjoyable badminton/ping-pong matches and hiking excursions)”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.859.

- Control Variables: This study incorporated employees’ demographic characteristics—gender, age, educational background, marital status, organizational tenure, job level, and organizational type—as control variables to mitigate their potential impact on the statistical results and ensure accuracy. The justification for choosing these control variables is as follows: Perceptions of workplace ostracism have been found to differ by gender, with men generally reporting higher levels than women in similar contexts [89]. Younger individuals tend to exhibit higher levels of FoMO [90]. Employees with higher education levels, particularly those holding doctoral degrees, are more likely to engage in knowledge-bearing behaviors [91], potentially resulting in variations in creative territory behavior. Unmarried individuals often exhibit diminished psychological well-being and may offset their lack of ownership through creative territorial behaviors [92]. Employees in different types of organizations may exhibit different behaviors [93]. Middle managers demonstrate more pronounced territorial defense behaviors compared to frontline employees [94]. Therefore, this study includes seven control variables (i.e., gender, age, educational background, marital status, organizational tenure, job level, and organizational type), based on prior research findings and standard practice in related studies.

3.3. Data Analysis Strategy

In this study, the collected questionnaire data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 24.0. First, SPSS 26.0 was employed to assess the reliability of the scales, as well as to perform descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Second, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using AMOS 24.0 to validate the research model, and a common method bias test was performed in SPSS 26.0. Finally, hierarchical regression analysis was carried out in SPSS 26.0 to examine the moderating effect of fun activities and the mediated moderation effect.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

SPSS 26.0 was used in this study to calculate the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for workplace ostracism, workplace FoMO, employees’ creative territory behavior, and fun activities. The results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The mean, standard deviation and correlation coefficient of each variable.

As shown, workplace ostracism is positively correlated with employees’ creative territory behavior (r = 0.463, p < 0.01) and with workplace FoMO (r = 0.552, p < 0.01). Additionally, workplace FoMO is significantly and positively associated with creative territory behavior (r = 0.501, p < 0.01). These findings are consistent with our theoretical expectations and provide a robust basis for subsequent hypothesis testing.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Common Method Bias Test

To assess discriminant validity, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the four variables including workplace ostracism, fun activities, workplace FoMO, and employees’ creative territory behavior. As shown in Table 2, the hypothesized four-factor model demonstrated a better fit to the data (χ2 = 608.067, df = 424, χ2/df = 1.434, RMSEA = 0.036, CFI = 0.961, IFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.958) compared to alternative models, including the single-factor model (all variables combined), the two-factor model (workplace ostracism, fun activities and workplace FoMO combined), and the three-factor model (fun activities and workplace FoMO combined).

Table 2.

Comparison and analysis of model fitting.

Furthermore, since all four variables in this study were measured using self-reported data, the potential for common method bias was examined using Harman’s single-factor test in SPSS 26.0. The results revealed that the predominant unrotated factor possessed an eigenvalue of 9.528, representing 30.734% of the total variance, well below the 40% threshold, indicating no significant common method bias in the data.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. The Analysis of Moderation Effect

Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to examine the moderating effect of fun activities. Before testing the moderation effect, workplace ostracism and fun activities were mean-centered, and an interaction term was created.

To test Hypothesis 1, four regression models (Models 1–4) were established, with the results shown in Table 3. The analysis showed that fun activities significantly moderated the relationship between workplace ostracism and workplace FoMO (Model 4, β = −0.217, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

The moderating effect of fun activities.

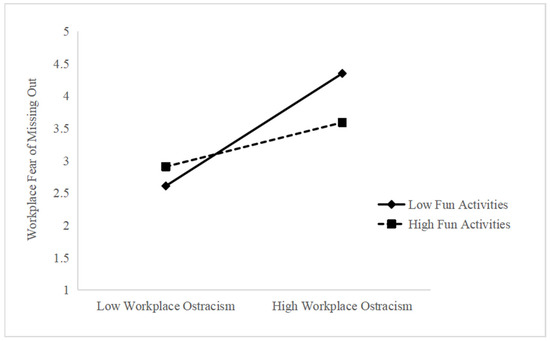

To visually demonstrate the moderating effect of fun activities, we conducted regression analyses by categorizing fun activities into high and low levels (defined as one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively). Finally, simple slope plots were generated to depict the effects of workplace ostracism on workplace FoMO under different levels of fun activities, as shown in Figure 2. The results revealed that (1) for employees in high-fun-activities organizations, workplace ostracism positively influences workplace FoMO (simple slope = 0.383, SE = 0.059, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.267, 0.498]); while (2) for employees in low-fun-activities organizations, workplace ostracism has a stronger positive impact on employees’ workplace FoMO (simple slope = 0.815, SE = 0.073, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.671, 0.958]). By comparing the slopes of the two, it can be found that the slope under high-fun-activities is smaller (0.383 < 0.815), indicating that in organizations with a high level of fun activities, workplace ostracism leads to a smaller increase in employees’ FoMO. That is, providing abundant fun activities can effectively buffer the positive impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ FoMO, further supporting Hypothesis 1.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of fun activities on the relationship between workplace ostracism and fear of missing out.

4.3.2. The Analysis of Mediated Moderation Effect

Drawing on the research of Wen et al. (2006), the test for mediated moderation effects should include the following three steps [95]: (1) Conduct a regression of the dependent variable (Y) on the independent variable (X), the moderator (U), and their interaction term (UX). If the coefficient of UX is significant, it indicates that U has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between Y and X. (2) Perform a regression of the mediator (W) on the independent variable (X), the moderator (U), and the interaction term (UX). If the coefficient of UX is significant, it indicates that U has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between W and X. (3) Perform a regression of the dependent variable (Y) on the independent variable (X), the moderator (U), the interaction term (UX), and the mediator (W). If the coefficient for W is significant, it indicates that the moderating effect of U operates (at least partially) through the mediator W. Based on this framework, the following analyses were conducted:

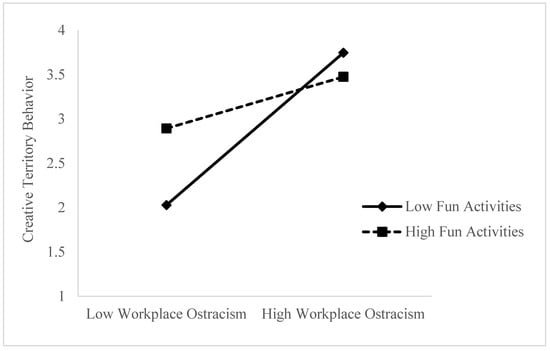

First, creative territory behavior was regressed on the control variables, workplace ostracism, fun activities, and their interaction term (workplace ostracism × fun activities). As shown in Table 4 (Models 5–8), fun activities significantly weaken the positive impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ creative territory behavior (Model 8, β = −0.205, p < 0.001). Figure 3 presents the simple slope analysis, demonstrating that for employees in high fun-activity organizations, workplace ostracism positively influences creative territory behavior (simple slope = 0.344, SE = 0.070, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.206, 0.482]); while for those in low fun-activity organizations, the effect is stronger (simple slope = 0.805, SE = 0.089, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.630, 0.980]). It can be seen that the slope under high-fun-activities is smaller (0.344 < 0.805), indicating that in organizations with a high level of fun activities, workplace ostracism leads to a smaller increase in employees’ creative territory behavior. Thus, fun activities can weaken the positive impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ creative territory behavior.

Table 4.

Test results of mediated moderation effect.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of fun activities on the relationship between workplace ostracism and creative territory behavior.

Second, the regression results in Table 3 confirmed that fun activities demonstrate a significant negative moderating effect between workplace ostracism and workplace FoMO (Model 4, β = −0.217, p < 0.001).

Finally, by incorporating workplace FoMO into Model 9 (Table 4), we found that the moderating effect of fun activities on the relationship between workplace ostracism and creative territory behavior is partially mediated by workplace FoMO (Model 9: The regression coefficient for workplace FoMO is 0.329 and p < 0.001, while the interaction term of workplace ostracism × fun activities remained statistically significant). This supports the mediated moderation model, thereby validating Hypothesis 2. Therefore, through alleviating employees’ FoMO arising from workplace ostracism, fun activities can significantly weaken the positive impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ creative territory behavior.

5. Discussion

Guided by Affective Events Theory, this study empirically explored the internal mechanisms through which fun activities weaken the effects of workplace ostracism based on data from 337 valid samples.

As hypothesized, fun activities were found to significantly and negatively moderate the positive relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ workplace FoMO. This result aligns with prior research emphasizing the buffering effect of positive work environments in mitigating stressor-related outcomes. For example, Baydur and Uçan (2025) found that workplace social support mitigates the negative impact of job insecurity on employees’ health-related quality of life [96]. Similarly, Kwan et al. (2018) demonstrated that perceived organizational support weakens the negative effects of workplace ostracism on task resources and creative process engagement [12]. However, our findings differ from those of Yang et al. (2023), who argued that fun activities are not always beneficial. When organizational fun activities are too frequent or even exceed a certain level, they may impose a burden on employees, causing them to fall into a resource loss spiral [88]. Other scholars have also noted that overly controlled or artificial fun may backfire, leading employees to perceive them as manipulative, thereby triggering counterproductive outcomes [97]. In this study, fun activities are conceptualized as a form of indirect organizational support that enables employees to make more positive resource evaluations, thereby reducing their FoMO. This resource-enhancing mechanism is consistent with previous findings [32,69].

Furthermore, this study found that workplace FoMO partially mediates the moderating effect of fun activities on the relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ creative territory behavior. This finding aligns with research demonstrating that workplace ostracism triggers defensive behaviors in employees. For example, Bhatti et al.’s (2023) showed that workplace ostracism has a positive impact on employees’ knowledge hiding behavior [43], which shares similar resource-protection motivations with creative territorial behavior. Meanwhile, recent research by Tang et al. (2024) also found that social network disruption and limited information access triggered by workplace ostracism may lead to employees’ FoMO [35], a state closely linked to job insecurity [39] and likely to promote defensive coping strategies such as effort reduction and diminished knowledge sharing [98,99]. These results not only respond to scholars’ calls for further exploration of the antecedents of creative territory behavior [74] but also empirically support Brown’s (2009) proposition that individuals’ relationships with colleagues may trigger territorial behavior [77].

Additionally, from the perspective of Complex Adaptive System (CAS) theory, the members of a system are active agents with adaptive characteristics. They can interact with each other and their environment, adjusting internal structures in response to complexity, thereby driving system evolution and development [100]. An organization can thus be seen as a dynamic CAS composed of employees who continuously exchange resources and information, shaping the system’s overall state and trajectory [101,102,103]. Within this framework, the moderating role of fun activities revealed in this study reflects their function as a self-organizing and self-regulatory mechanism within organizational systems. When stressors such as workplace ostracism disrupt resource equilibrium among agents, they may provoke negative states like FoMO, threatening system stability. Fun activities provide a platform for positive emotional experiences, informal social connections, and information exchange, helping employees replenish resources and mitigating the diffusion of ostracism’s negative impact across the system. Consequently, the moderating effect of fun activities not only reflects individual-level resource buffering but also illustrates how complex adaptive systems achieve self-maintenance and regulation through internal interactions.

6. Conclusions

The findings indicate that fun activities can not only directly alleviate employees’ FoMO induced by workplace ostracism, but also indirectly weaken the impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ creative territory behavior by alleviating this apprehension. This insight offers a fresh theoretical perspective on coping mechanisms for workplace ostracism and provides valuable implications for organizational management practices. However, this study has certain limitations that warrant further exploration in future research.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

First, this study enriches the theoretical research achievements of fun activities in the workplace. While prior research has largely emphasized the direct support from leaders, colleagues, and organizations in buffering the effects of workplace ostracism, it has paid little attention to indirect forms of organizational support. Unlike prior research that treated workplace fun as an independent variable to explore its outcomes, this study conceptualizes fun activities as an indirect supportive environment created by organizations. From the perspective of enhancing employees’ coping efficacy, we empirically examined how fun activities weaken the negative effects of workplace ostracism. This not only expands the research boundaries of fun activities but also highlights the potential value of organizational context factors in alleviating the negative impacts of workplace ostracism, offering further theoretical support for developing a more supportive work environment.

Second, this study expands the research on the internal mechanisms through which workplace ostracism influences employees’ creative territory behavior. Employees’ psychological and behavioral responses to ostracism have long been a central concern in organizational behavior research. Departing from previous studies grounded in Social Exchange Theory or Conservation of Resources Theory, this study adopts Affective Events Theory and introduces workplace FoMO as a mediating variable. This reveals the internal mechanism by which workplace ostracism triggers employees’ creative territory behavior. The findings provide a novel explanatory framework for understanding the relationship between workplace ostracism and creative territory behavior, and enrich the empirical research on workplace FoMO within the Chinese organizational context.

6.2. Practical Implications

In the context of intensifying market competition, fostering effective creative communication and collaboration among employees to generate valuable solutions has become essential for building a robust innovation ecosystem and achieving sustainable competitive advantage. This study empirically examines the moderating effect of fun activities on the relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ creative territory behavior, offering the following practical implications for organizational management:

First, this study provides a theoretical foundation for organizations to integrate ostracism governance into their management system. Organizations should fully acknowledge the substantial impact of workplace ostracism on employees’ creative territory behavior and embed ostracism governance mechanisms into human resource management practices such as leadership development and performance evaluations. Specifically, training modules on “ostracism governance” can be designed to enhance managers’ awareness and handling capabilities regarding ostracism. In addition, “peer-rated inclusiveness” could be incorporated into performance appraisal systems, and anonymous reporting channels for ostracism incidents should be established. Verified reports may be directly linked to performance evaluations to ensure accountability. These measures are expected to promote a healthy organizational innovation ecosystem and reinforce its long-term resilience.

Second, this study provides theoretical support for organizations to enhance their focus on employees’ adjustment to FoMO. To mitigate this concern, organizations should optimize internal information flow by developing platforms such as a “project progress dashboard” that provides real-time updates on project developments, resource distribution, and career advancement opportunities, thereby reducing information asymmetry. Furthermore, organizations can offer employees courses in mindfulness meditation and emotional regulation training and mental health counseling to equip them with the skills necessary to alleviate FoMO. Additionally, team-based stress-relief activities (e.g., sports events, art therapy) can facilitate employees’ stress release and strengthen their psychological resilience. These measures contribute to enhancing employees’ psychological capital, thereby accumulating energy for the development of organizational innovation resources.

Third, this study serves as a reference for balancing employee well-being and organizational development. Managers should prioritize cultivating an enjoyable and harmonious work environment. This can be achieved by designing customized fun activity plans through an “ideas crowdfunding platform” encouraging employees to propose activities that enhance their sense of engagement and belonging. Moreover, incorporating structured elements such as challenging tasks, frustration simulations, and team-based breakthroughs into fun activities can foster psychological resilience, positive cognition, and emotional regulation skills. Such efforts systematically enhance their psychological capital while broadening employees’ exposure to positive experiences and interpersonal networks, thus promoting creative interaction. Ultimately, this approach facilitates the co-development of both employees and the organization.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study adhered to rigorous scientific research protocols, several limitations remain that could be addressed for improvement in the future.

First, all variables in this study were measured using self-reported data from employees, which may affect the accuracy and reliability of the results. Future studies could address this issue by employing multi-source data collection methods, such as leader-employee or employee-coworker dyads, to reduce bias and enhance the robustness of the conclusions.

Second, although a phased data collection approach was adopted, the two-wave design may limit the rigor of the mediating effect conclusions and cannot fully establish causal relationships among variables. Future research could utilize a three-wave longitudinal design to strengthen the validity of mediational inferences or adopt experimental methods or cross-lagged panel models to clarify the causal links between workplace ostracism and employees’ creative territory behavior.

Third, based on Affective Events Theory, this study examined the moderating role of fun activities in the relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ creative territory behavior from the perspective of employees’ coping resource evaluations. Future research could incorporate alternative theoretical frameworks to uncover additional mechanisms and boundary conditions underlying the relationship, thereby enriching the theoretical landscape.

Fourth, the sample and data were drawn from a single national and cultural context, which may limit the generalizability of the conclusions. Future research could expand the scope by conducting cross-cultural comparative studies (e.g., exploring differences between Eastern and Western cultures) or using multinational samples to assess the broader applicability of these findings, thereby enhancing the study’s external validity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and C.F.; methodology, H.W.; validation, C.F.; formal analysis, H.W. and C.F.; investigation, H.W.; resources, H.W. and C.F.; data curation, H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W. and C.F.; writing—review and editing, H.W. and C.F.; visualization, H.W.; supervision, C.F.; project administration, C.F.; funding acquisition, C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China [No. 24BGL286], the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province [No. 23GLB004] and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [No. B240207102].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study according to the Measures for Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans (Article 32, Chapter 3) (https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm, accessed on 1 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all participants in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The following are the measurement items adopted.

Table A1.

Workplace ostracism scale.

Table A1.

Workplace ostracism scale.

| Questionnaire Items | |

|---|---|

| Workplace ostracism | At work, some people ignore my feelings or opinions. |

| Sometimes, when I enter a place, someone present immediately leaves. | |

| Sometimes, when I greet certain people, I don’t get a response. | |

| During lunch, I always sit alone in a busy restaurant. | |

| At work, some people deliberately avoid me. | |

| At work, I’ve noticed that some people don’t pay attention to me. | |

| At work, some people don’t want me to join their discussions. | |

| At work, some people refuse to talk to me. | |

| At work, sometimes people dismiss me or act as if I don’t exist. | |

| At work, when someone goes out for a break or to buy coffee, they neither invite me nor ask if I’d like anything. |

Table A2.

Fun activities scale.

Table A2.

Fun activities scale.

| Questionnaire Items | |

|---|---|

| Fun activities | Social events organized by the organization (e.g., holiday parties and picnics). |

| Team-building activities hosted by the organization (e.g., fun badminton/ping-pong games and hiking trips). | |

| Competitive events held by the organization (e.g., team sales contests, production competitions, and knowledge/skill challenges). | |

| Public recognition of employees’ achievements by the organization (e.g., openly praising outstanding work results). | |

| Company-hosted recognition for personal milestones (e.g., birthday celebrations, weddings, and work anniversary commemorations). |

Table A3.

Workplace fear of missing out scale.

Table A3.

Workplace fear of missing out scale.

| Questionnaire Items | |

|---|---|

| Information fear of missing out | I worry that I might miss important work-related updates. |

| I worry that I might miss valuable work-related information. | |

| I worry that I might miss important work-related messages. | |

| I worry that I might miss crucial information related to my job. | |

| I worry that I might be unaware of what’s happening at work. | |

| Relational fear of missing out | I worry that I might miss an opportunity to build important business relationships. |

| I keep thinking that I might miss chances to strengthen professional connections. | |

| I keep thinking that I might miss opportunities to establish new business relationships. | |

| I worry that I might miss out on networking opportunities that my colleagues will have. | |

| I worry that my colleagues might make business connections that I don’t. |

Table A4.

Employees’ creative territory behavior scale.

Table A4.

Employees’ creative territory behavior scale.

| Questionnaire Items | |

|---|---|

| Claiming behaviors | I will let others know that I have claimed ownership of certain creative ideas. |

| I will make it clear to others which creative ideas belong to me. | |

| I will define the boundaries of certain creative ideas (clarifying which ones are mine and which are not). | |

| Anticipatory defending behaviors | I will make some of my creative ideas difficult for others to use or access. |

| I will conceal some of my creative ideas, ensuring others don’t learn about them until I’m ready to share. | |

| I will make some of my creative ideas appear less appealing so others won’t want to obtain the ownership of them. |

Demographic Information:

- Gender: (Male/Female)

- Age: (25 or below/26–35/36–45/46–55/Above 55)

- Educational Background: (High school or vocational school and below/Associate degree/Bachelor’s degree/Master’s degree or above)

- Marital Status: (Single/Married)

- Organizational Tenure: (1 year and below/1–3 years/3–5 years/5–10 years/Over 10 years)

- Job Level: (Ordinary employee/Frontline supervisor/Middle manager/Senior executive)

- Organization Type: (State-owned enterprise/Private company/Joint venture or foreign-owned company/Government or public institution/Other)

References

- Li, X.M.; Cheng, C.; Yang, S.S. Why not go the usual way? Empowering leadership, employees’ creative deviance and innovation performance. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 780–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W.J.; Su, J.F. How Does Abusive Supervision Influence Employee’s Sustainable Innovation Behavior: The Moderating Effect of Psychological Empowerment? J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 1745–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Noe, R.A. Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajuoja, M.; Viitala, R.; Henttonen, K. Supporting innovating employees: How managerial coaching affects four dimensions of innovative work behavior. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Liu, C.H. The power of coworkers in service innovation: The moderating role of social interaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 1956–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasanidou, D.; Sivertstol, N.; Hildrum, J. Exploring employee interactions and quality of contributions in intra-organisational innovation platforms. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 458–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoe, A.F.; Boateng, H.; Narteh, B.; Boakye, R.O. Examining human resource practice outcomes and service innovation. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Dhar, R.L. Workplace ostracism: A process model for coping and typologies for handling ostracism. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2024, 34, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, L.B. Does workplace ostracism lead to knowledge hiding? Modeling workplace withdrawal as a mediator and authentic leadership as a moderator. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 3593–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.D.; Xia, Q.; He, P.X.; Sheard, G.; Wan, P. Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding in service organizations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 59, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samma, M.; Zhao, Y.; Rasool, S.F.; Han, X.; Ali, S. Exploring the Relationship between Innovative Work Behavior, Job Anxiety, Workplace Ostracism, and Workplace Incivility: Empirical Evidence from Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs). Healthcare 2020, 8, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, H.K.; Zhang, X.M.; Liu, J.; Lee, C. Workplace Ostracism and Employee Creativity: An Integrative Approach Incorporating Pragmatic and Engagement Roles. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.P.; Chang, P.C.; Chang, H.Y. How workplace fun promotes informal learning among team members: A cross-level study of the relationship between workplace fun, team climate, workplace friendship, and informal learning. Empl. Relat. 2022, 44, 870–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jang, E. Workplace Ostracism Effects on Employees’ Negative Health Outcomes: Focusing on the Mediating Role of Envy. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.S.M.; Wu, L.Z.; Chen, Y.Y.; Young, M.N. The impact of workplace ostracism in service organizations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, A.J.; Wang, B.; Song, B.H.; Zhang, W.; Qian, J. How and when workplace ostracism influences task performance: Through the lens of conservation of resource theory. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Phetvaroon, K.; Li, J. Left out of the office “tribe”: The influence of workplace ostracism on employee work engagement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2717–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.D.; Peng, Z.L.; Sheard, G. Workplace ostracism and hospitality employees’ counterproductive work behaviors: The joint moderating effects of proactive personality and political skill. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Schabram, K. Current Directions in Ostracism, Social Exclusion, and Rejection Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Z.H.; Yuan, L.; Wang, J.L.; Wan, Q.C. When the victims fight back: The influence of workplace ostracism on employee knowledge sabotage behavior. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 1249–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Zhao, R.; You, Y. The Influence of Work Resources on the Creative Territory Behavior of Chinese New Generation Knowledgeable Employees: Research based on SEM and fsQCA. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2023, 44, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, W.; Luo, J.; Li, X.; Huang, Y. Why are Good Ideas So Hard to Implementation? A Cross Level Research Based on Territoriality Perspective. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2018, 39, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Y.W.; Kim, T. Impact of using social network services on workplace ostracism, job satisfaction, and innovative behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2017, 36, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A.; Prewett, M.S. Employee Responses to Empowering Leadership: A Meta-Analysis. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yin, S. How Does Workplace Exclusion Affect Employees’Sharing Willingness? Research Based on the Perspective of Social Support. Soc. Constr. 2021, 8, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, X.S.; Xie, M.X. Employee innovative behavior and workplace wellbeing: Leader support for innovation and coworker ostracism as mediators. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1014195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Yang, D.; Sun, W.; Xu, L. Building a Resilient Organization Through Informal Networks: Examining the Role of Individual, Structural, and Attitudinal Factors in Advice-Seeking Tie Formation. Systems 2025, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, M.J.; Michel, J.W.; Allen, D.G. Fun and friends: The impact of workplace fun and constituent attachment on turnover in a hospitality context. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, W.; Jeong, C. Workplace fun for better team performance: Focus on frontline hotel employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1391–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, J.; Dimple. Fun at workplace and intention to leave: Role of work engagement and group cohesion. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 782–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekhorst, J.A.; Halinski, M.; Good, J.R.L. Fun, Friends, and Creativity: A Social Capital Perspective. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 970–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, M.J.; Michel, J.W.; Stafford, K. Does Fun Pay? The Impact of Workplace Fun on Employee Turnover and Performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 34–74. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Fu, Q.; Tian, X.; Kong, Y. Affective Events Theory: Contents, application and future directions. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 599–607. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.C.; Chi, L.C.; Tang, E. Office islands: Exploring the uncharted waters of workplace loneliness, social media addiction, and the fear of missing out. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 15160–15175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnick, C.J.; Rogers, A.P.; Barber, L.K. The fear of missing out at work: Examining costs and benefits to employee health and motivation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Wen, M.; Fang, Z.; Niu, Y.; Tang, J. Research on Chinese Employees’Fear of Missing Out Based on Grounded Theory: Connotation, Structure and Formation Mechanism. Manag. Rev. 2022, 34, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.H.; Li, J.H.; Liu, H.; Zaggia, C. The association between workplace ostracism and knowledge-sharing behaviors among Chinese university teachers: The chain mediating model of job burnout and job satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1030043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Pang, H.; Xie, Z. A Measurement Analysis of the Chinese Version Employee Fear of Missing Out Scale. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 32, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Islam, N.; Talwar, S.; Mäntymäki, M. Psychological and behavioral outcomes of social media-induced fear of missing out at the workplace. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.H.; Yang, M.X.; Farro, A.C.; Yuan, L. I cannot miss it! The influence of supervisor bottom-line mentality on employee presenteeism. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2024, 45, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Social media induced fear of missing out (FoMO) and phubbing: Behavioural, relational and psychological outcomes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Hussain, M.; Santoro, G.; Culasso, F. The impact of organizational ostracism on knowledge hiding: Analysing the sequential mediating role of efficacy needs and psychological distress. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D.; Zadro, L. Ostracism: On Being Ignored, Excluded, and Rejected; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism: The Power of Silence; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, D.L.; Brown, D.J.; Berry, J.W.; Lian, H.W. The Development and Validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1348–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. Effect of Workplace Ostracism on Employees′ Contextual Performance: Mediating Roles of Organizational Identification and Job Involvement. J. Manag. Sci. 2010, 23, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, E.; Chen, X. How Can We Make a Sustainable Workplace? Workplace Ostracism, Employees’ Well-Being via Need Satisfaction and Moderated Mediation Role of Authentic Leadership. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.J.; Zhu, H. The Predictive Effects of Workplace Ostracism on Employee Attitudes: A Job Embeddedness Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiul, M.K. Does one’s sense of psychological safety mitigate the link between workplace ostracism and employee vitality? Meaningful work as a boundary role. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 123, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Le, J.; Peng, Z. Research on antecedents of workplace ostracism behavior: A model with moderated mediator. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2016, 37, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Li, S.; Gong, L.Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, S.W. How and when workplace ostracism influences employee deviant behavior: A self-determination theory perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1002399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Kang, H.Y.; Jiang, Z.; Niu, X.Y. How does workplace ostracism hurt employee creativity? Thriving at work as a mediator and organization-based self-esteem as a moderator. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Cheng, Z.H.; Liu, W.X. Spotlight on the Effect of Workplace Ostracism on Creativity: A Social Cognitive Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 01215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.W.; Yang, J.Y. The mediating effects of organization-based self-esteem for the relationship between workplace ostracism and workplace behaviors. Balt. J. Manag. 2017, 12, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.; Peng, Z. The Effect of WOB on Positive Organizational Behavior and Group Efficiency: Cross-Level Perspective. Bus. Manag. J. 2013, 35, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, S.; Newell, W. Co-worker ostracism and promotive voice: A self-consistency motivation analysis. J. Manag. Organ. 2022, 28, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçel, N.; Kavak, B. Being an ethical or unethical consumer in response to social exclusion: The role of control, belongingness and self-esteem. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.T.; Wong, M.Y. Fear of missing out (FoMO): A generational phenomenon or an individual difference? J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 37, 2952–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Wu, Y.; Pang, H.; Liu, Z.; Xie, Z. Structural measures, multidimensional effects and formation mechanisms of workplace fear of missing out. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 31, 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.N. Impact of workplace fun in a co-working space on office workers’ creativity. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2024, 37, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.W.; Tews, M.J.; Allen, D.G. Fun in the workplace: A review and expanded theoretical perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chang, M.; Lu, Z. Study on the Mechanism of Workplace Fun on Employees’ Innovative Behavior. J. Manag. Sci. 2019, 32, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Yao, B. Can Workplace Fun Promote Employees’ Creativity? The Role of Feedback Seeking Behavior and Person-Organization Fit. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2019, 36, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Hsu, F.S.; Lin, H. Workplace fun and work engagement in tourism and hospitality: The role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Chen, W.; Cai, R. The Effects of Cognition of Insider’s Status on Proactive Behavior: The Mediating Effect of Psychological Capital and the Moderating Effect of Inclusive Leadership. J. Cent. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2017, 04, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.H.; Li, J. Having fun and thriving: The impact of fun human resource practices on employees’ autonomous motivation and thriving at work. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 63, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.C.; McLaughlin, F.S.; Newstrom, J.W. Questions and answers about fun at work. Hum. Resour. Plan. 2003, 26, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tews, M.J.; Michel, J.W.; Noe, R.A. Does fun promote learning? The relationship between fun in the workplace and informal learning. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chang, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, M. Fun at work: Connotation, Measurement, and Mechanism. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2020, 37, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petelczyc, C.A.; Capezio, A.; Wang, L.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Aquino, K. Play at Work: An Integrative Review and Agenda for Future Research. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edney, J.J. Human territoriality. Psychol. Bull. 1974, 81, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Lawrence, T.B.; Robinson, S.L. Territoriality in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Zhao, R. Effects of Paradoxical Leadership on Employees’ Creative Territory Behavior: Mediating Role of Team Interaction and Regulating Role of Individualism. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2022, 42, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Yuan, L. Why Not Share Good Ideas? The Effect of Leaders′ Bottom-line Mentalityon the Employees′ Creative Territory Behavior. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2024, 41, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tang, C. Exploitative Leadership and Territorial Behavior: Conditional Process Analysis. Chin. J. Manag. 2020, 17, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. Claiming a corner at work: Measuring employee territoriality in their workspaces. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Effect of fear of missing out on college students’ negative social adaptation: Chain-mediating effect of rumination and problematic social media use. China J. Health Psychol. 2022, 30, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, J.; Cao, Z. Research on the Psychological Mechanism of Employees Maintain Proactive Behavior Under Illegitimate Tasks: The Moderating Effect of Growth Mindset. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2025, 42, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Research on the Inhibiting Mechanism of Employee Innovation Behavior from the Perspective of Negative Emotion. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zoonen, W.; Treem, J.W.; Sivunen, A. An analysis of fear factors predicting enterprise social media use in an era of communication visibility. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.Y.; Yuan, C.Q. Workplace Ostracism and Helping Behavior: A Cross-Level Investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 190, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.F.; Kwan, H.K.; Li, M.M. Experiencing workplace ostracism with loss of engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2020, 35, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, X.; Cai, Y. Workplace Ostracism and Cyberloafing: Moderating Effect of Job Embeddedness. J. Technol. Econ. 2019, 38, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, R.J. How and when does enterprise social media usage threaten employees’ thriving at work? An affective perspective. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2025, 38, 704–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Crossley, C.; Robinson, S.L. Psychological ownership, territorial behavior, and being perceived as a team contributor: The critical role of trust in the work environment. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, M.; Huang, Y. The Inverted U-shaped Relationship between Fun Activities and Employees’Innovative Behavior—Based on the Role of Work Engagement and Job Autonomy. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlan, R.T.; Clifton, R.J.; Desoto, M.C. Perceived Exclusion in the Workplace: The Moderating Effects of Gender on Work-related Attitudes and Psychological Health. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2006, 8, 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, J.P.; Buff, C.L.; Burr, S.A. Social Media and the Fear of Missing Out: Scale Development and Assessment. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016, 14, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Song, G. Research on the Knowledge Domain Behavior of Employees in Internet Enterprise. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2016, 36, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; An, R. How Does Organizational Territorial Behavior of Scientific and Technological Talents Affects Turnover Intention: Based on the Moderating Mediating Model of Psychological Ownership and Marriage. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2019, 36, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; He, A. The Influence Mechanism between Workplace Ostracism and Knowledge Hiding: A Moderated Chain Mediation Model. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2019, 22, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Li, Q. A Study on Territorial Behavior of Employees: Based on Demographic Characteristics. J. Nanjing Audit Univ. 2014, 11, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hou, J. Mediated Moderator and Moderated Mediator. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2006, 38, 448–452. [Google Scholar]

- Baydur, H.; Uçan, G. Association between job insecurity and health-related quality of life: The moderator effect of social support in the workplace. Work-A J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2025, 80, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tews, M.J.; Jolly, P.M.; Stafford, K. Fun in the workplace and employee turnover: Is less managed fun better? Empl. Relat. 2021, 43, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, A.; Bontis, N. Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1199–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Liu, M.; Li, X. Will AI Trigger Employee Knowledge-hiding Behavior? From the Perspective of Relative Deprivation. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2024, 46, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Studying complex adaptive systems. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2006, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, G.; He, X.; Qin, Z. An Analysis on the Complexity of Enterprise Knowledge Sharing. J. Intell. 2008, 27, 146–148+123. [Google Scholar]

- Chiva-Gómez, R. The facilitating factors for organizational learning: Bringing ideas from complex adaptive systems. Knowl. Process Manag. 2003, 10, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamo, J.; Phillips, F. The evolutionary organization as a complex adaptive system. In Proceedings of the Innovation in Technology Management. The Key to Global Leadership. PICMET’97, Portland, OR, USA, 31 July 1997; pp. 325–330. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).