Abstract

This scoping review explores the integration of sustainability into design education within Taiwanese higher education institutions. Taiwan has implemented education reforms and national sustainability policies, yet their integration into creative disciplines like design remains limited. Guided by the PRISMA-ScR framework, this study systematically identified and analyzed sixteen peer-reviewed articles published over the past decade. Thematic analysis and co-occurrence keyword mapping using VOSviewer were used to examine how sustainability is reflected in design curricula. The findings reveal that, while sustainability is frequently addressed in project-based learning and material experimentation, its incorporation remains inconsistent and largely peripheral. Cluster analysis of the literature indicates that national sustainability policies and education initiatives are primarily concentrated in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields and general education, with minimal connection to design departments. Design pedagogy in Taiwan emphasizes creativity, iteration, and localized engagement, yet these practices are rarely aligned with policy frameworks or systemic curricular strategies. Barriers include fragmented frameworks and the absence of interdisciplinary collaboration. Despite these limitations, the review identifies promising entry points—mainly through pedagogical innovation and community-based initiatives. This study concludes by calling for policy-aligned, curriculum-integrated approaches to strengthen the role of design in advancing Taiwan’s sustainable education agenda.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the Taiwanese government has implemented various policies to promote sustainability in education. The legislative framework has encouraged higher education institutions to develop curricula incorporating sustainability principles across disciplines, including design education. A major national initiative—the Taiwan Sustainable Campus Program (TSCP)—has linked infrastructure reform with sustainability curriculum development. Since 2002, this program has funded over 500 institutions, including more than 18% of higher education institutions (HEIs), to develop site-specific educational modules grounded in sustainability principles [1]. The Ministry of Education (MOE) and other agencies offer targeted financial support for institutions to develop sustainability-focused research, infrastructure, and curriculum integration, including interdisciplinary modules and general education materials. These efforts are further supported by targeted Ministry of Education (MOE) funding for sustainability-oriented curricula, general education, and cross-disciplinary collaboration.

While sustainability themes are increasingly included in general education programs, in many cases, sustainability is relegated to general education requirements, offering limited discipline-specific depth and minimal opportunities for interdisciplinary integration [2,3,4,5], core disciplines like design still lack cohesion. Research further indicates that, while some study programs in Taiwan have made strides in incorporating sustainability, the effectiveness and depth of this integration vary widely [6,7,8,9]. Liu and Kan [9] conducted a comprehensive review of 1872 sustainability-related courses across 29 Taiwanese universities and found that sustainability content remains concentrated in STEM fields, while design and other creative disciplines are often marginalized. Thus, while strong government policies and cultural values support sustainability education in Taiwan, its actual curricular integration, especially within design departments, remains fragmented and underdeveloped.

To address this gap, this study conducts a scoping review to map the landscape of sustainable education practices within design higher education in Taiwan, identifying key challenges and opportunities for future research. By systematically examining peer-reviewed articles published over the last decade, this research provides a comprehensive overview of how sustainability is integrated into design curricula [6,9]. While Taiwan has made notable progress in promoting sustainability within higher education, significant challenges remain. The insights gained from this review aim to inform educators and policymakers about the current state of sustainable design education in Taiwan and to highlight areas for further development in both research and practice.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a review of relevant literature on sustainability in design education. Section 3 outlines the research design, including the scoping review framework and co-occurrence analysis. Section 4 reports the results, organized into four thematic clusters: sustainability policy and systems in higher education; cognitive and practical pedagogies in design education; innovation and curriculum design; and local and cultural dimensions. Section 5 provides a critical discussion of these findings, highlighting institutional and policy disconnections, pedagogical strengths and limitations, fragmented innovation, and the marginalization of cultural sustainability. Section 6 concludes this paper by summarizing the findings and offering suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Education in Higher Education

A key aspect of contemporary sustainable education is the integration of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into curricula. There is a specific Sustainable Development Goal for education (SDG4), and education is intrinsically linked to all the other SDGs [10]. Various targets associated with this goal explicitly call for universities to take action, while many others are closely related to teaching and learning processes in higher education institutions [9]. In particular, higher education is crucial for achieving the SDGs [11], as the influence of higher education institutions on driving sustainability transitions within societies is widely recognized [12,13,14]. Universities, as key influencers and agents of change, must take on a more significant and prominent role in the transformation process driven by the SDGs [5].

In higher education, the commitment to promoting sustainability is increasingly emphasized through calls for curricular reform across various disciplines and contexts [15]. It is essential that sustainability becomes an integral component of higher education policies and is reflected in the pedagogical approaches, practices, and activities implemented within these institutions [5,16]. However, research highlights the necessity for a systemic approach that encompasses not only educational content but also institutional policies and practices. Studies indicate that the key challenges to effectively implementing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in universities are inadequate support from administration and management, a general apathy towards sustainability issues, and the lack of dedicated structural units, such as committees, to drive these initiatives [17]. The whole-institution approach is crucial, integrating governance, curriculum, campus operations, and community outreach to establish a unified framework for sustainability in HEIs [18,19,20]. Their sustainability commitments, expressed through various declarations, are often ineffective unless combined with both internal and external strategies, addressing activities within and outside the institution [21]. This comprehensive model encourages alignment between educational objectives and the overarching sustainability vision, facilitating transformations within educational institutions. Without addressing systemic inertia, educational organizations may struggle to effectively incorporate sustainability into their practices [22].

The methodologies employed in delivering sustainable education have also undergone transformation. Project-based learning (PBL) is a significant methodology in sustainable education that actively engages students in real-world sustainability challenges through interdisciplinary collaboration. PBL effectively incorporates the SDGs into the curriculum, empowering students to tackle sustainability issues while honing their critical thinking and problem-solving skills [23,24]. Despite these advancements, challenges remain. Educational institutions frequently grapple with entrenched beliefs about education that hinder the comprehensive integration of sustainability principles [22], and a comprehensive reform of educational practices is still necessary.

2.2. Design Education and Sustainability

The integration of sustainability into design education has emerged as a critical imperative in response to escalating global environmental and social challenges [25]. Consequently, the integration of sustainability into design curricula is now viewed not merely as an enhancement but as a necessity. As design disciplines shift from aesthetic- or function-driven paradigms toward more responsible, systems-oriented models, sustainability is increasingly embedded as a foundational component of design pedagogy. The imperative calls for meaningful curricular adjustments that better reflect the complexity and urgency of sustainability challenges by embedding systems thinking, material literacy, social innovation, and circular design as core pedagogical pillars [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Some studies suggest that, among the various pillars of sustainability in design education, ecological literacy is especially influential in shaping environmental responsibility and informing both design theory and practice [25,28,32,33].

Building on the growing emphasis on sustainability within design education, the concept of Design for Sustainability (DfS) has emerged as a framework guiding both pedagogical approaches and professional practice [25,34]. DfS expands on traditional eco-design by promoting a systems-oriented approach that considers environmental, social, and economic factors throughout the design process. It serves as both a theoretical framework and a practical strategy, equipping students to address real-world sustainability challenges. Ceschin and Gaziulusoy [34] have identified four innovation levels in pro-sustainability design: Product, Product-Service System, Spatio-Social System, and Socio-Technical System. This classification forms an evolutionary framework for various pro-sustainability design approaches. By integrating DfS into curricula, educators can effectively incorporate ecological literacy, circular economy principles, and social innovation into core design education, offering a structured way to apply these ideas in both academic and practical contexts.

Despite growing recognition of sustainability in design education, its integration remains inconsistent and often superficial, with many programs treating it as an add-on rather than a core component [12,35]. The prevailing perspective on sustainability has primarily been technical and scientific, concentrating on carbon levels and waste management. However, sustainability fundamentally concerns itself with ensuring conditions conducive to the well-being of both humans and non-humans in the future. As such, it should be examined from diverse viewpoints [33].

3. Materials and Methods

This research used a scoping review methodology to explore existing literature on a specific topic, identifying key concepts, research gaps, and available evidence. This approach is useful in fields with complex information, as it clarifies ideas and directs future research. A scoping review is a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses exploratory research questions through systematic and iterative searching, selection, summarisation, and potential synthesis of existing knowledge [36]. This definition aligns with the framework established by Arksey and O’Malley, which outlines the main goals of scoping reviews, including assessing the scope of research activity and determining the need for a full systematic review [37,38].

Scoping reviews are characterized by their broad approach, which allows for the inclusion of diverse types of evidence, thereby facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the literature [39]. Unlike systematic reviews that answer specific research questions, scoping reviews provide an overview of the available evidence and identify areas where further research is needed [40,41]. This exploratory nature is particularly beneficial for policymakers and researchers looking to assess the landscape of a particular field before committing to more detailed systematic reviews [42]. The iterative nature of scoping reviews allows flexibility in adapting the review process as new insights emerge, a significant advantage over more rigid systematic review methodologies [41,43].

One of the primary objectives of a scoping review is to clarify key concepts and definitions in the literature, which is essential for advancing knowledge in emerging fields [44,45]. This process involves systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge, which can reveal under-researched areas that require further exploration [46]. By doing so, scoping reviews contribute to the academic discourse and assist stakeholders, including policymakers and practitioners, in understanding the current state of research and its implications for practice [47].

In this study, the scoping review methodology enhances the validity of the findings by systematically mapping a diverse and evolving body of literature. This approach ensures comprehensive coverage of the available evidence, facilitating the identification of recurring themes, gaps, and inconsistencies that may be overlooked by more focused methods. Therefore, it establishes a strong and clear basis for making contextually relevant conclusions about sustainable design education in Taiwan.

3.1. Study Design and Research Questions

The main research question guiding this study is the current status of sustainability integration within design curricula at various higher education institutions in Taiwan. This question seeks to clarify the extent of integration and to highlight gaps needing further exploration.

The methodology adheres to Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework [42,46], which outlines a systematic process comprising six stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results, and (6) consultation with stakeholders [42,46]. This study is an initial exploratory effort to map the current state of sustainable design education in Taiwan, systematically identifying and analyzing relevant literature to establish a foundation for future research. The initial phase does not include stakeholder consultation; however, its importance for subsequent research is acknowledged, as stakeholder consultation is vital to incorporate diverse perspectives and enhance the relevance of educational practices [48,49]. The findings from this initial phase will help shape the questions and topics for future stakeholder consultations.

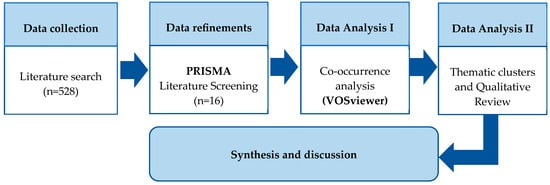

This research employs a systematic methodology organized into three primary stages: data collection, data refinement, and data analysis, in which a two-step data analysis is utilized as illustrated in Figure 1. In the first stage, data collection entails a literature review focused on “Sustainable Design Education in Taiwan,” sourcing studies from Scopus, ERIC, and WoS databases. These resources contain a selection of peer-reviewed articles that are crucial for gaining insight into sustainable design education in Taiwan. These resources include peer-reviewed articles that are crucial for gaining insight into the current landscape of sustainable design education in Taiwan.

Figure 1.

Research framework used for this study.

The second stage, data refinement, adheres to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines to optimize the search results. It begins with a broad search using keywords such as “sustainable,” “higher education,” and “Taiwan,” followed by a more targeted search that includes the term “design.” Establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria then helps to refine the focus to studies specifically addressing sustainability in design education within the context of Taiwan. In the third stage, data analysis employs VOSviewer for co-occurrence analysis, creating thematic clusters from key terms in the articles. These clusters identify the main themes in sustainable design education. The articles are then reviewed, and the findings are summarized to provide an overview of the field.

Finally, the conclusions of this study are collated, summarized, and synthesized, integrating insights from the literature and data analysis. This process ensures that the research provides a comprehensive understanding of sustainable design education in Taiwan and highlights areas for future research and development in this field.

3.2. Databases and Screening

The search process for this scoping review utilizes the Web of Science, Scopus, and ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) databases. These databases were selected to ensure a comprehensive and rigorous review of sustainable education practices in Taiwan’s design of higher education. Web of Science provides extensive multidisciplinary coverage of high-quality, peer-reviewed education, sustainability, and environmental science studies. Scopus offers a broad range of sources across disciplines, including social sciences, aiding the exploration of institutional and cultural factors in sustainable education. ERIC is a key resource for educational research, offering in-depth access to studies, reports, and articles related to teaching practices, curriculum development, and educational innovations.

This research implemented specific inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) to identify relevant studies while screening titles, abstracts, and full texts. The selected articles were restricted to peer-reviewed public research studies that utilized primary data, which aligned with this study’s emphasis on various investigations. These articles were written in English and focused on sustainable design education in Taiwan. Exclusions were made for non-peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, book chapters, and studies concerning other educational subjects, such as fine arts and performing arts. All relevant studies were subsequently retrieved, and the search results were imported into EndNote, where the references were verified, and duplicates were eliminated.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria.

The initial step in the screening process involves defining the search keywords (Table 2). The data encompass publication archives from 2015 up to the most recent research. The researcher utilized the keywords “Sustainable Design Education in Taiwan” to search the Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC databases. Despite using specific search terms such as “sustainable,” “design,” “higher education,” and “Taiwan,” the initial results were unexpectedly broad, including studies from unrelated fields like performing arts and research outside the design domain. This reflects the interdisciplinary nature of the keywords. After the initial search, the results were refined to align with the specific research criteria that had been established. In the final, more precise search, we further specified the keywords to include terms such as higher education, sustainability, Design, and Taiwan as the geographic focus.

Table 2.

Initial Search summary database.

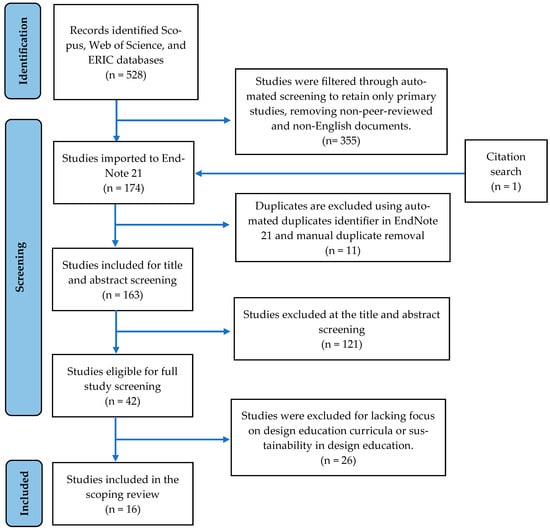

To enhance the methodological rigor and transparency of the scoping review, the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines were utilized [41,42]. The PRISMA-ScR checklist provided a structured framework for reporting the findings (Figure 1), ensuring the review adhered to best practices in evidence synthesis. This approach was critical given the increasing popularity of scoping reviews and the need for clear guidelines to facilitate consistent reporting [50,51]. PRISMA-ScR allowed for a systematic search, selection, and synthesis of literature while distinguishing the scoping review from systematic reviews, which typically focus on answering specific research questions through rigorous synthesis [43,44]. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram used in this study follows the format proposed by Page et al. [52] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA screening process.

Initially, 528 records were identified through searches in Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC databases using the keyword “Sustainable Design Education in Taiwan Higher Education.” From these, studies that were not relevant, such as non-peer-reviewed, non-English, or non-primary sources, were excluded during an automated screening process, reducing the number of studies to 355. A total of 173 studies were imported into EndNote for additional screening. During this step, a relevant citation was identified, even though the article was outside the time frame initially set for this study. After removing duplicates using automated tools and manual checks, 163 studies were included in the title and abstract screening phase. Following this, a manual selection process was conducted to identify articles that align with the objectives of this study. At this stage, 121 studies were excluded based on title and abstract screening due to their lack of relevance to this study’s focus. A total of 42 studies were deemed eligible for full study screening, where a more detailed assessment occurred.

At this stage, 26 studies were ultimately excluded as they either lacked a focus on design education curricula or did not incorporate sustainability in design education. Excluding articles such as “Engineering Design Thinking in LEGO Robot Projects: An Experimental Study” [53], it focuses on design thinking within the engineering field. In contrast, “Trans-disciplinary Education for Sustainable Marine and Coastal Management: A Case Study in Taiwan” [54] discusses sustainable education irrelevant to the design field. A selection of excluded studies during the PRISMA process is provided in Table 3 to illustrate the exclusion rationale. The final dataset for the review included 16 studies (Table 4), which were selected after the identification and screening processes. This review protocol was registered [55] and is accessible via the Open Science Framework (OSF). The completed PRISMA 2020 checklist [56] is provided as Supplementary Table S1.

Table 3.

Example of excluded publications during the PRISMA process.

Table 4.

Studies included in this review.

3.3. Co-Occurrence Analysis

To generate the cluster data for this study, a bibliometric analysis was conducted using VOSviewer 1.6.20, a software tool designed for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks. The co-occurrence analysis method enables creating and visualizing a network of emerging themes by examining the relationships between words within a text, utilizing linguistic analysis to recognize patterns [74] and node representations of important terms, their weight, and their location within the network [75]. This method facilitates the identification of keyword relationships by mapping their frequency and co-occurrence patterns, thereby revealing conceptual structures and emerging themes within the field. The process began by importing the bibliographic data from the 16 articles selected for the scoping review. The data were then processed to extract key terms and keywords related to sustainability, design education, and higher education. The co-occurrence of these keywords was analyzed to identify clusters, which represent groups of closely related terms.

The software used a text-mining technique to identify frequent keywords and mapped them into visual clusters based on their proximity and frequency of appearance within the articles. This method ensures that only frequently occurring and relevant keywords are included [76]. This process involved selecting the minimum number of occurrences for a keyword, ensuring that only relevant terms were included in the analysis. The full counting method was employed, assigning equal weight to each occurrence of a keyword within a document. Keywords served as the unit of analysis, with a minimum occurrence threshold established at three. The resulting clusters were visually represented, showing the relationships between different keywords and highlighting the key themes present in the literature. The data were then interpreted to understand the main focus areas in sustainable design education in Taiwan, revealing both well-explored themes and gaps in the literature.

4. Results

This section presents the findings from the investigation into the integration of sustainability within design curricula across higher education institutions in Taiwan. It is structured to address three key questions: the current state of sustainability integration in design programs in Taiwan HEIs.

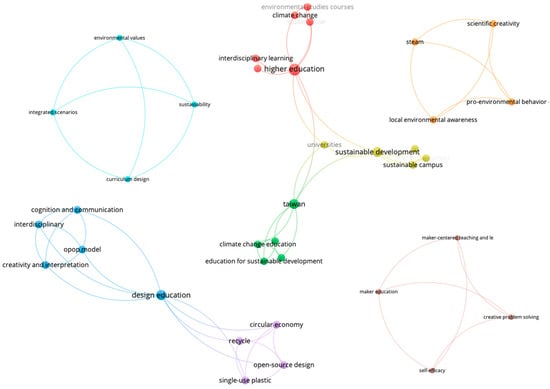

4.1. Key Thematic Clusters

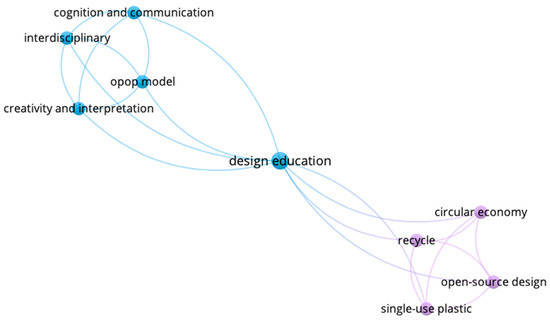

Each cluster in the visualization (Figure 3) represents a grouping of concepts frequently appearing together, indicating shared topical relevance. For instance, the yellow–green cluster, which includes terms such as sustainable development, sustainable campus, Taiwan, climate change education, and education for sustainable development, illustrates a peripheral yet administratively significant framing of sustainability in Taiwanese higher education. These keywords align with national policy instruments (e.g., SDGs, TSCP) and institutional infrastructure reforms, consistent with some prior studies. The partial overlap and incomplete visualization of some keywords, such as environmental studies courses, universities, energy consumption, and student views, arise from their close proximity and significant co-occurrence, as illustrated by VOSviewer. This graphical limitation underscores the dense thematic interconnections among the terms, rather than suggesting any data omission. It should be understood as evidence of the strong conceptual relationships present in the reviewed literature. These sources emphasize energy efficiency, environmental audits, and systemic ecological education initiatives at the university level.

Figure 3.

Thematic clusters from co-occurrence analysis.

However, the absence of co-occurrence with keywords such as design education and curriculum design signals a disciplinary marginalization of design within national sustainability education efforts. This spatial exclusion confirms a core argument of this study: that design programs are not structurally integrated into Taiwan’s sustainability discourse despite widespread policy-level engagement in higher education institutions. Thus, the cluster visualization becomes not just a mapping of terms but a diagnostic tool revealing thematic silos and conceptual disconnections.

In the overall visualization, additional clusters offer complementary insights. The blue cluster emphasizes cognitive and pedagogical constructs, such as the One Product/Project/Performance, One Paper (OPOP) model, creative interpretation, and interdisciplinary learning, while the purple cluster centers on practical sustainability efforts, including recycling, circular economy, and single-use plastic. The red cluster highlights centralized institutional strategies, featuring terms like higher education, climate change, and environmental studies courses. The spatial separation between clusters, especially between design-focused nodes and system-level sustainability terms, visually substantiates this study’s claim that design education in Taiwan, though pedagogically rich, remains conceptually and institutionally disconnected from the national sustainability agenda.

The co-occurrence analysis conducted using VOSviewer revealed several key thematic clusters, such as the role of higher education in addressing climate change, the evolving landscape of design education, and the integration of environmental awareness and hands-on learning approaches. Each cluster reflects the multidimensional nature of incorporating sustainability into design curricula, with varying degrees of depth and effectiveness across institutions. This section presents an overview of the clusters identified, supported by relevant citations from the reviewed literature.

Table 5 provides a summary of key terms extracted from the VOSviewer co-occurrence network, detailing their clustering and link strength and offering quantitative support for the thematic mapping described above. The data presented here are an illustrative sample from the full VOSviewer dataset, selected to represent a cross-section of the most conceptually significant keywords across clusters. They complement the thematic clusters discussed in the visual map and accompanying analysis.

Table 5.

Keyword co-occurrence metrics: cluster, frequency, and link strength.

In the co-occurrence table, each keyword is plotted in a two-dimensional space using x and y coordinates, which indicate its relative position within the network visualized by VOSviewer. These coordinates reflect the conceptual proximity between terms; closer keywords suggest stronger topical relationships. The cluster number shows the thematic group assigned by VOSviewer based on the strength of co-occurrence, organizing related terms into distinct categories. “Weight (Links)” refers to the total number of direct connections a keyword has with other terms, indicating its centrality within the conceptual network. “Weight (Occurrences)” measures how frequently a keyword appears in the dataset, providing a quantitative assessment of its prominence.

The co-occurrence analysis of literature regarding sustainable design education in Taiwan’s higher education institutions identifies five thematic clusters (Table 6). These clusters highlight sustainability’s fragmented and uneven integration within design curricula, ranging from cognitive and pedagogical practices to isolated applications of circular economy principles. Policy-driven sustainability discourse in higher education is evident, yet design education remains conceptually peripheral, underscoring the disciplinary divide in national sustainability implementation.

Table 6.

Key findings from keyword co-occurrence analysis.

The following subsections describe each of the five thematic clusters in detail. By examining the underlying keywords, representative literature, and corresponding curricular implications, this section aims to unpack how each theme contributes to the broader discourse on sustainable design education and where significant gaps remain. This structure contextualizes current efforts and reveals actionable insights for enhancing sustainability integration within design departments in Taiwanese HEIs.

4.1.1. Sustainability Policy and System in Higher Education

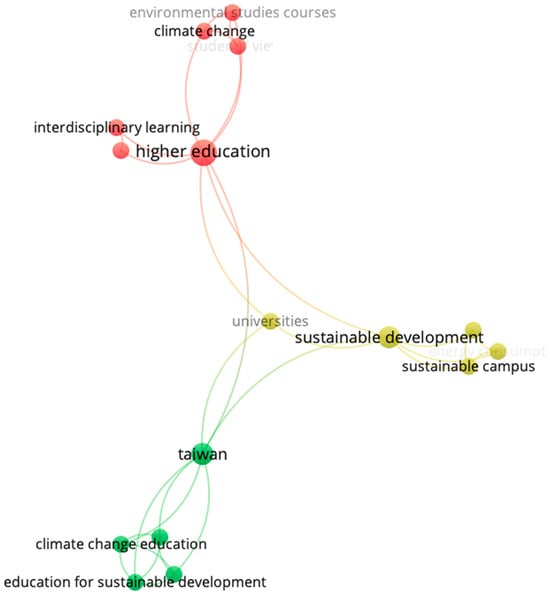

The central cluster emerging from the co-occurrence analysis centers on policy and institutional infrastructure. It is dominated by terms such as higher education, climate change, environmental studies courses, and interdisciplinary learning (see Figure 4). These keywords collectively represent scholarly attention to macro-level sustainability efforts in Taiwanese universities.

Figure 4.

Cluster map: policy-centric themes and design absence.

The second cluster emphasizes administrative and national policy frameworks of sustainability in Taiwanese higher education. Dominated by terms such as sustainable development, sustainable campus, Taiwan, climate change education, and education for sustainable development, this cluster reflects a top-down orientation grounded in national initiatives like the SDGs and the TSCP.

Sustainability policy and systems in Taiwan’s higher education are shaped by national initiatives, institutional frameworks, and global discourses on sustainable development. National-level policies, including the Environmental Education Act (2011) and the TSCP, provide overarching guidelines that encourage universities to embed sustainability into their curricula and campus operations [1,9]. The National Council for Sustainable Development (NCSD) is working to monitor progress and provide guidance on action plans, while the Ministry of Education (MOE) promotes ESD at all levels. Policies like the Green Building Code and green purchasing mandates encourage environmentally responsible practices on campuses. The TSCP further strengthens these efforts by funding over 507 institutions to integrate renewable energy, wetlands, and organic farming into campus infrastructure, embedding sustainability into everyday operations [1]. In 2019, Taiwan’s NCSD introduced a localized version of the SDGs. Following this, in 2020, the Ministry of Education published the “Learn SDGs for Taiwan Schools” handbook, which outlines educational strategies specifically tailored to the context of Taiwan [9].

Although these policies provide a strong framework, their systematic integration into design education remains limited. A quantitative map shows this predominance of ESD in STEM fields and calls for more balanced representation across disciplines [9]. These studies demonstrate the extensive focus on policy-driven and STEM-oriented sustainability in HEIs, while design education remains conceptually and institutionally peripheral. Design education presents additional insights into the importance of aligning policy frameworks with practical applications by exploring the integration of University Social Responsibility (USR) into design curricula. This approach supports the MOE Higher Education Cultivation Project and UNESCO’s lifelong learning goals, highlighting the significance of local connections and community engagement [64]. Advocating for sustainability literacy in design education is also achieved by incorporating principles of the circular economy and utilizing project-based learning to promote environmental responsibility [64,69]. This study shows that sustainability in design education is also influenced by marine education policies. The White Paper on Marine Education Policy outlines a 10-year Marine Education Project (2007–2016) that integrates sustainability into higher education curricula, aligning with international frameworks. This policy is operationalized through the design curriculum, as exemplified by an auto-photographic study [68], demonstrating how sustainability initiatives can extend beyond traditional policy frameworks, yet this remains fragmented and unsystematic.

However, those studies mentioned above also imply that the success of the program depends not only on technological innovations but also on societal participation and a collective commitment to sustainability principles. It shows how these efforts often appear as isolated practices rather than part of a cohesive strategy. Implementation challenges in higher education arise from departmental silos, limited interdisciplinary collaboration, and rigid major selection requirements, all of which hinder curriculum innovation. Similarly, the implementation of sustainability policies faces obstacles such as budget constraints, management issues, and the need for consensus among stakeholders [9,61]. Addressing these interconnected challenges is vital to embed sustainability systematically into design education and effective sustainability initiatives. It indicates that policies should prioritize quality, long-term advantages, and comprehensive promotion.

4.1.2. Cognitive and Practical Pedagogies in Design Education

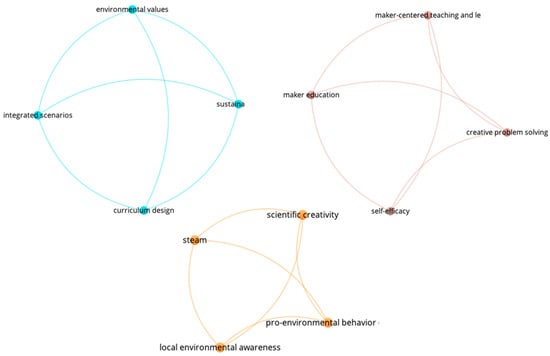

Where national sustainability discourse in Taiwan is primarily shaped by top-down institutional policy and environmental governance, design education presents a distinctively bottom-up, student-centered approach that emphasizes creativity, interpretation, and experiential learning. This contrast is reinforced through cluster analysis, which highlights terms like cognition, communication, and interdisciplinarity, underscoring design education’s emphasis on cognitive and reflective practice rather than policy alignment.

Taiwanese design programs illustrate this orientation through models prioritizing conceptual development and reflective output. The OPOP (One Product/Project/Performance, One Paper) framework guides students to translate creative endeavors into scholarly expression, embedding cognitive scaffolding within iterative and interpretive design processes [70]. This aligns with Chen’s curricular strategy and blends cognitive and affective elements to transform students’ environmental values through future-oriented thinking exercises [62]. The creative problem-solving (CPS) model cultivates environmentally responsible makers, demonstrating how iterative design cycles can build ecological awareness through practical engagement [63].

Huang et al. further emphasize the affective dimension and propose a “know, feel, and do” model that links cognitive instruction, emotional engagement, and behavioral application into a cohesive pedagogy for sustainable development [7]. These efforts are echoed in interdisciplinary STEAM initiatives that show measurable gains in student awareness and creativity, though they often remain limited to isolated modules or localized projects rather than institutionalized curricula [63,66]. This compartmentalization restricts long-term impact, as sustainability thinking is rarely scaffolded across multiple years or embedded as a core learning outcome.

While foundational to design learning, these cognitive-rich pedagogies show minimal integration with formal sustainability strategies. The cluster map (Figure 5) illustrates this structural disconnection. Notably, core concepts like “systems thinking,” “life cycle impact,” and “long-term transformation” are largely absent from both the keyword analysis and the curricular discourse. Even in pedagogically advanced models like design-based learning for web and visual communication [71,73], sustainability often functions as a theme rather than a competency. This reflects a broader lack of curricular alignment with the ESD framework or the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Figure 5.

Cluster map: cognitive pedagogy in design education.

The need for curricular integration is underscored by studies showing gaps between student awareness and action. Taiwanese undergraduates often express concern about climate issues but lack confidence and structured opportunities to engage meaningfully with them in academic settings [67]. Similarly, students’ understanding of ocean sustainability remains superficial without reflective or personally grounded learning interventions [68]. Innovative programs incorporating Industry 4.0 tools and circular economy frameworks into studio projects often lack alignment with institutional sustainability competencies or SDG frameworks [69].

Despite notable contributions to sustainability education, such initiatives in Taiwan primarily exist within short-term modules, electives, or community-based studios rather than being integrated into the mandatory curriculum. Research focusing on life cycle analysis, institutional metrics, or program-level outcomes related to sustainability remains limited. These sustainability engagements are often localized or instructor-driven, restricting their reach and effectiveness as systemic learning components.

In summary, this analysis reinforces the conclusion that, while design pedagogy in Taiwan promotes deep cognitive and creative engagement, it lacks structural integration with sustainability. As a result, students may graduate with strong design thinking skills but find themselves ill-equipped to apply these skills to address sustainability challenges. The conceptual divide between design pedagogy and national or institutional sustainability agendas presents a significant barrier to advancing sustainability within the design discipline.

4.1.3. Innovation and Curriculum Design

The cluster analysis identifies a meaningful thematic grouping centered around design-based learning (Figure 6), creative problem-solving, curriculum design, studio projects, and curriculum reform. These terms collectively reflect the growing emphasis on pedagogical innovation in Taiwanese design education, highlighting how instructors and institutions are responding to the evolving needs of students by embedding process-driven, exploratory, and constructivist approaches.

Figure 6.

Cluster map: innovation pedagogies and curriculum reform in design education.

Curriculum innovation is evident in multiple instructional models that emphasize experiential, interdisciplinary, and reflective practices. For example, design-based learning (DBL) has been implemented to help students improve their web design skills through iterative, real-world tasks that foster problem-solving and domain integration [71]. Similarly, the OPOP model provides a structured framework for students to convert personal experience into research output, reinforcing creativity and critical thinking through academic reflection [70]. Narrative theory has been shown to enhance students’ conceptual development, image creativity, and cultural storytelling skills in visual communication design through structured storytelling techniques [73]. Physical engagement with materials and spatial movement has inspired concept generation in architectural education, linking tactile exploration with cognitive insight and aesthetic awareness [72].

Sustainability is not consistently integrated as a central theme in curriculum reform. The co-occurrence patterns suggest that curricular reform efforts prioritize creative capacity-building over sustainability alignment. Few studies within this cluster integrate sustainability as a core objective of curriculum innovation. Terms related to environmental ethics, social impact assessment, or sustainability learning outcomes are notably absent. As such, sustainability is often an implicit rather than explicit outcome in many of these curriculum development initiatives. An exception is found in the work of Nagatomo, who aligns the curriculum with SDGs by incorporating circular economy principles and Industry 4.0 tools into student design research, addressing issues such as single-use plastic waste through open-source, participatory projects [69].

Curricular reform efforts in design education often prioritize building creative capacities over aligning with sustainability goals, as seen in the absence of key terms related to environmental ethics and sustainability learning outcomes. This indicates that sustainability frequently remains an implicit outcome of these initiatives. Furthermore, the disconnect between innovative design curricula and national sustainability policy terms, such as SDGs and climate change education, limits design departments’ ability to scale their sustainability education efforts. Overall, while there is progress in pedagogical and curricular innovation, aligning these reforms with sustainability objectives remains a significant challenge in Taiwanese design education.

4.1.4. Local and Cultural Dimensions

The co-occurrence analysis reveals that, while keywords such as culture, design communication, and local environmental awareness are present, their connection to the broader sustainability education discourse is minimal. However, the cluster appears thematically isolated and lacks strong conceptual or bibliographic links to institutional sustainability initiatives or national educational policies. There is little evidence that local cultural perspectives are systematically integrated into sustainability strategies at the program or curriculum level. Instead, cultural responsiveness in design education remains largely experimental and project-specific, dependent on the initiative of individual instructors or short-term collaborations.

What emerges from the literature is not a lack of interest in cultural integration but a lack of systemic support. Cases like Hsieh’s [64] action research demonstrate how community engagement with Indigenous knowledge can cultivate empathy and sustainable values through culturally respectful design processes. These instances show that students can meaningfully interact with local environments and identities, fostering sustainability not as an abstract concept but as a lived, contextualized practice. Moreover, students’ ability to engage meaningfully with sustainability appears contingent on culturally resonant pedagogy. While awareness of climate issues is widespread among Taiwanese students, confidence in taking action remains low without supportive, participatory learning environments, and understanding of sustainability tends to be superficial unless mediated by reflective and culturally situated instruction [67,68]. These findings point to a missed opportunity: institutions may undermine the agency and engagement they seek to promote through sustainability education by failing to systematically integrate culture and local context.

The disconnect is not merely thematic but strategic. Cultural knowledge and local environmental awareness rarely align with institutional goals such as the SDGs or ESD frameworks. As a result, even strong pedagogical practices—such as design-based learning and studio experimentation—often bypass the cultural dimensions that could make sustainability education more holistic, inclusive, and relevant [69,71]. This isolation reinforces the impression that cultural content is supplemental rather than foundational, thereby marginalizing it within the overall architecture of sustainability in higher education.

The absence of connections to broader clusters—particularly policy, pedagogy, and curriculum—reinforces the fragmentation of cultural integration in sustainable design education. This limits the reach of place-based learning approaches and represents a missed opportunity to align local relevance with global sustainability imperatives. As a result, while cultural awareness and local responsiveness offer meaningful pathways toward sustainability, their role in design education remains peripheral and underleveraged within the broader sustainability discourse in Taiwanese HEIs.

The results suggest that, although design education in Taiwan is fertile ground for innovation and creativity, it lacks a strategic, curriculum-wide alignment with sustainability frameworks. This thematic fragmentation reflects an urgent need to transition from isolated practices to cohesive, policy-aligned, and culturally embedded sustainability education within design departments.

5. Discussion

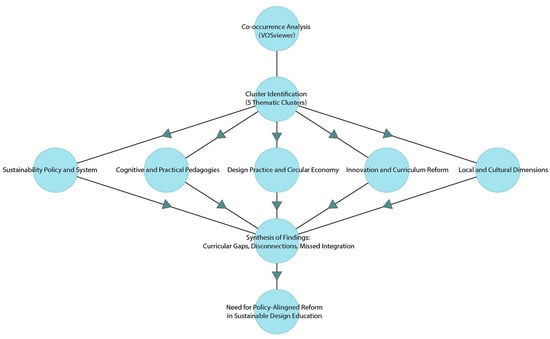

This scoping review examined how sustainability has been integrated into design education within Taiwanese higher education institutions over the past decade. The findings reveal a recurring pattern of fragmentation, disciplinary marginalization, and missed opportunities within design programs. While national sustainability agendas in Taiwan, driven by policies such as the Environmental Education Act and the SDG framework, have catalyzed reform across STEM and general education, design education remains largely peripheral to this momentum. Through bibliographic cluster analysis, this review identifies three interrelated themes that highlight the limitations and potential of sustainable design education in the Taiwanese context.

The analytical pathway of this review, as shown in Figure 7, begins with bibliometric mapping using VOSviewer. Five thematic clusters were identified, each representing key dimensions of sustainable design education in Taiwan. These clusters were then interpreted to reveal underlying gaps, including curricular fragmentation, limited policy alignment, and missed opportunities for systemic integration. The analysis ultimately informs this study’s conclusion: the need for cohesive, policy-aligned reforms within design education.

Figure 7.

Co-occurrence analysis was conducted in this study.

This discussion builds on the findings in the results chapter, highlighting various approaches and methodologies that Taiwanese higher education institutions use to promote sustainable education. Initially, the focus was intended to be on sustainable education within design disciplines; however, the availability of English-language articles was minimal. Consequently, the discussion expanded to include general trends in sustainable education across Taiwan’s higher education system, with particular emphasis on design education where relevant. This shift reflects the scarcity of studies explicitly addressing sustainability in design programs. By analyzing the collected articles, this sub-chapter provides an in-depth exploration of curricula, pedagogical strategies, and outcomes, emphasizing the role of design education in advancing sustainability principles.

5.1. Policy and Institutional Disconnection

National efforts to promote sustainability in higher education have been visible. However, the implementation within design curricula remains inconsistent, ad hoc, and often lacks institutional coherence. Sustainability discourse in Taiwan is primarily concentrated at the policy and administrative level, particularly in STEM and general education domains. Despite strong national initiatives such as the TSCP and the Environmental Education Act, design education remains absent from these systemic reform efforts. This confirms that institutional sustainability frameworks rarely extend into the design discipline, resulting in a missed opportunity for transdisciplinary alignment.

Sustainability is typically present in elective courses, project-based modules, or student-led initiatives, rather than embedded into the core curriculum or linked to program-wide learning outcomes. This curricular fragmentation reflects broader structural issues: design programs are often excluded from top-down sustainability policy efforts, resulting in a disciplinary gap between national reforms and localized educational practice.

This disconnect is evident in the absence of key policy-related terms, such as SDGs, ESD, or institutional strategy, from design-related literature. While frameworks for sustainability transformation exist across Taiwan’s HEIs [1]. Design departments rarely translate SDGs into actionable strategies and often lack involvement in strategic implementation, even in universities aligning their curricula with the SDGs, as offering a large number of related courses does not ensure preparedness if the curriculum remains structured around traditional disciplinary silos [77]. As a result, sustainable design education is left structurally unsupported, thematically isolated, and lacking integration with Taiwan’s broader sustainability agenda. The integration of sustainability in Taiwan’s higher education curriculum is often superficial and fragmented, showcasing the need for cohesive pathways that align educational practices with national sustainability goals [9].

Although design education in Taiwan is both pedagogically sophisticated and materially active, it remains conceptually and institutionally disconnected from broader sustainability agendas. While tangential connections to sustainability can be observed, mainly through initiatives like material reuse and studio projects, these efforts are not guided by a curriculum aligned with the SDGs or integrated into policy frameworks. Without stronger curricular mandates or policy alignment, such design initiatives risk becoming isolated, inconsistent, and unsustainable.

5.2. Pedagogical Strengths and Structural Gaps

Policy integration remains limited, and the pedagogical models present within design education offer strong alignment with sustainability principles. Design programs in Taiwan demonstrate robust use of reflective and creative pedagogies. Cluster analysis identified rich engagement with cognitive development, creativity, iterative learning, and design-based problem-solving competencies that resonate closely with the goals of education for sustainable development. Yet, these pedagogical strengths remain underleveraged due to their separation from institutional sustainability frameworks. These pedagogical innovations are not aligned with sustainability competencies such as systems thinking or environmental ethics. For example, a study included in this review by Chin-Fei Huang on STEAM education demonstrated that integrating local environmental awareness materials significantly enhanced university students’ pro-environmental behavior and engagement with real-world environmental issues, yet had no notable impact on originality in scientific creativity [63]. This suggests that while creative and cognitive competencies are present, they are not necessarily directed toward sustainability goals. The absence of co-occurrence between cognitive pedagogy and sustainability frameworks indicates that design students may develop strong creative capacities without being equipped to apply these effectively to ecological or social challenges.

Such structured pedagogical approaches enhance students’ technical competencies and cultivate a more profound understanding of sustainability within the design field. By offering hands-on experiences, these courses empower students to apply sustainability principles to real-world contexts [69,78]. Another growing trend in Taiwan’s sustainable education landscape is the adoption of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics) education. By incorporating arts and design into traditional STEM curricula, universities aim to foster creativity and innovation while addressing complex sustainability challenges. STEAM education enhances students’ ability to develop holistic solutions, bridging the gap between technical skills and creative problem-solving. This interdisciplinary approach is essential in tackling global sustainability issues, as it encourages students to think beyond their primary field of study [54,79].

This underutilization is not the result of pedagogical weakness but rather a lack of curricular scaffolding, assessment metrics, and cross-disciplinary collaboration. Without policy recognition or program-level objectives, sustainability is experienced as a thematic suggestion rather than a defined learning outcome. There is untapped potential to connect existing instructional innovation with national and global sustainability goals, provided institutional support structures are created to facilitate that alignment.

5.3. Fragmented Innovation and Weak Curricular Integration

Taiwanese design education showcases promising innovations, such as project-based learning, circular economy studios, and creative problem-solving. These efforts often remain isolated and unstructured within the broader curriculum. Sustainability-related practices, including recycling, low-impact material design, and community-based interventions, are typically found in elective modules, short-term workshops, or instructor-led experiments. However, these initiatives are rarely embedded into core courses or program-wide learning outcomes.

Similarly, many design programs emphasize pedagogical renewal through design-based learning and student agency, yet these reforms often prioritize creativity and adaptability over sustainability literacy. For instance, several included articles highlight the successful integration of creative problem-solving (CPS), maker education, and interdisciplinary collaboration to enhance adaptability and design fluency [65]. However, these approaches seldom include structured reflection on sustainability frameworks such as the SDGs or ESD, reinforcing the gap between pedagogical innovation and sustainability literacy. The lack of consistent alignment with frameworks such as the SDGs or ESD suggests that innovation unfolds without strategic direction. As a result, students are exposed to sustainability practices without structured guidance, evaluation, or continuity, undermining long-term impact.

The political and bureaucratic challenges faced by sustainability curriculum initiatives within Taiwan’s education system. While national policies advocate for the inclusion of sustainability in educational frameworks, the direct influence of these policies appears weak [9]. This disconnect is further worsened by the lack of key terms such as SDGs and ESD in the design curriculum discourse, highlighting a significant gap between broad educational policy and the specific practices of design departments. This disconnect is made worse by the absence of important concepts like SDGs and ESD in discussions about the design curriculum.

5.4. Cultural Sustainability as an Underleveraged Resource

Despite appearing as a more minor and peripheral cluster in the co-occurrence analysis, the local and cultural dimensions of sustainability in design education remain a critical thematic area worth highlighting. Global education frameworks, including UNESCO’s ESD roadmap, emphasize the importance of culturally responsive pedagogy and context-specific learning. These approaches root sustainability education in place-based experiences and foster relevance to local communities and identities, values particularly resonant in Taiwan’s diverse cultural landscape. These practices demonstrate the unique role that design education can play in contextualizing sustainability and fostering socially embedded responses to environmental challenges.

Cultivating culturally informed sustainability is challenging without a bridge that links local relevance to national frameworks. Moreover, the potential of design to visualize, prototype, and communicate systemic change has yet to be fully integrated into policy discussions. By repositioning design as a central element in sustainability education, we can transform its role from a passive implementer to an active agent driving sustainability transformations. This shift requires integrating place-based innovations into national ESD narratives and recognizing design as a vital curricular and strategic tool.

The literature’s limited representation of sustainable design education underscores a critical finding: in Taiwan, this field is fragmented and lacks cohesive integration. This section highlights how cultural perspectives often manifest in isolated case studies or short-term projects that typically lack the necessary curricular support and policy alignment. The thematic isolation in the literature and cluster mapping emphasize the disconnect between institutional sustainability frameworks and actual design education practices.

Focusing on local and cultural dimensions reveals significant place-based and community-oriented design initiatives. These efforts often draw on indigenous knowledge and regional environmental awareness, fostering meaningful community engagement. Universities in Taiwan, for example, are pioneering programs that link academic learning with local communities, demonstrating the impact of community and cultural engagement on sustainable education. However, these initiatives remain outside the formal curriculum and lack backing from institutional mandates, leading to cultural sustainability being treated as peripheral instead of central to Taiwan’s sustainability education strategy.

Numerous global studies link the weak integration of sustainability into higher education to a lack of supportive policies. However, the situation in Taiwan appears to be different. In Taiwan, comprehensive sustainability frameworks, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the TSCP, have already been established at the national level. Despite this, these policies have had minimal impact on design education, which remains largely disconnected from institutional sustainability agendas. This misalignment between policy and discipline suggests that national frameworks alone cannot drive transformation. Instead, targeted strategies within specific disciplines, faculty involvement, and curricular reform are necessary. These findings emphasize that even in environments rich in policy, implementation gaps can still occur, particularly in creative fields like design.

5.5. Study Limitations

This paper focuses primarily on English peer-reviewed literature and publicly available sources and may overlook valuable insights from unpublished syllabi, internal policies, and publications in local languages. Although English-language sources provide a strong foundation for identifying trends, integrating Supplementary Materials could deepen the understanding of faculty-led initiatives. Perspectives from instructors, students, and curriculum designers are absent, limiting insight into how sustainability is implemented in classrooms. Additionally, this review’s focus on Taiwan may introduce potential geographic and linguistic constraints that could affect the generalizability of findings to other contexts. Finally, while co-occurrence analysis effectively identifies thematic links, it does not evaluate the depth of pedagogical integration.

Despite these limitations, this research provides a solid foundation for assessing the current landscape of sustainability education in Taiwan’s design higher education. It also identifies opportunities for future empirical and comparative studies, including assessments of learning outcomes related to sustainability integration.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review explored the integration of sustainability into design education at higher education institutions in Taiwan. Using bibliographic analysis and thematic mapping, this study identified four key areas: policy systems, pedagogical approaches, curriculum innovation, and local cultural dimensions. While these areas show varying levels of engagement with sustainability, there is a significant disconnect between national sustainability frameworks and their application in design programs.

Sustainable design education in Taiwan is fragmented; despite supportive policies, sustainability integration is inconsistent. The disconnect between national frameworks and the practical realities of design education points to a structural issue often overlooked in global literature. These findings illustrate that the presence of national policies does not necessarily ensure effective curricular alignment, particularly in fields that lie outside traditional sustainability discussions. Recent evidence also indicates that, even when design programs adopt pedagogical innovations such as maker education or design-based learning, these reforms often prioritize creativity and adaptability over sustainability literacy unless explicitly guided by sustainability frameworks.

Innovations in community projects and material reuse show promise, yet these efforts often lack consistent policy support. Engaging faculty is essential for closing the sustainability gap. Without greater involvement from design educators in institutional sustainability efforts, curricular reform often remains sporadic and unsustainable. The limited inclusion of local knowledge in sustainable design education emphasizes this issue and the missed opportunities to connect global sustainability goals with Taiwan’s unique environmental and social contexts. Moreover, the limited application of strategic frameworks like the SDGs and Design for Sustainability (DfS) restricts the capacity of design education to systematically tackle sustainability across cognitive, material, and socio-cultural dimensions.

Three practical strategies are recommended: (1) Educators can enhance existing courses, such as integrated design projects or studio practice, by incorporating sustainability themes like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the circular economy, while also addressing the local environmental context. This strategy integrates sustainability into the curriculum without major changes. Encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration in classes or competition projects enhances design education by connecting students with peers in fields like engineering and applied science. These provide diverse perspectives and improve problem-solving skills, preparing students to address complex sustainability challenges. Additionally, they develop long-term community engagement and fieldwork projects, applying creative problem-solving (CPS) frameworks and narrative design methods to foster practical, reflective learning and social responsibility. (2) For institutions, a valuable strategy is to form a dedicated faculty working group composed of design educators who are committed to integrating sustainability into their teaching. This team can coordinate regularly, plan achievable short-term actions, and align efforts with broader institutional goals. In parallel, revising the program framework to embed sustainability and responsibility as core learning outcomes is essential. Such curricular revisions ensure that design education aligns with national sustainability policies, including the TSCP and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), fostering long-term institutional commitment. (3) Policymakers, in order to support the integration of sustainability in design education, should strengthen national frameworks that integrate the SDGs into design education. This includes investing in targeted funding and infrastructure to support partnerships among universities, industry, and communities, as well as setting clear guidelines aligned with the UN SDGs and recognizing institutions that lead in sustainability integration. Implementing evaluations of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and sustainability performance in higher education institutions can drive continuous improvement and success. Furthermore, offering training and workshops can equip educators with effective methods and tools for teaching sustainability.

Future research should consider several key areas to address this study’s limitations and build upon its findings. First, conducting qualitative interviews with educators, curriculum developers, and students will help to understand how sustainability is perceived, negotiated, and implemented within design programs. Additionally, analyzing curriculum content and course syllabi will identify how sustainability concepts are integrated across design courses and reveal any existing gaps. Incorporating local-language publications and non-indexed institutional materials may provide vital insights into culturally grounded, grassroots, or practice-led sustainability initiatives within the Taiwanese context. Lastly, a deeper examination of institutional governance and faculty development policies could shed light on the structural conditions needed to scale and embed sustainability more meaningfully within design education.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems13060470/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-C.T. and K.C.; methodology, J.-C.T. and K.C.; software, K.C.; validation, J.-C.T. and K.C.; formal analysis, J.-C.T.; investigation, J.-C.T. and K.C.; resources, J.-C.T. and K.C.; data curation, J.-C.T. and K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-C.T. and K.C.; writing—review and editing, J.-C.T. and K.C.; visualization, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Su, H.J.; Chang, T. Sustainability of Higher Education Institutions in Taiwan. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Shen, J.-P.; Kuo, T. An Overview of Management Education for Sustainability in Asia. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, M.L.; Madueño, J.H.; Calzado Cejas, M.Y.; Andrades Peña, F.J. A Proposal for Measuring Sustainability in Universities: A Case Study of Spain. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 671–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and Sustainability Teaching at Universities: Falling Behind or Getting Ahead of the Pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.L.; Pivec, M. Integration of Sustainability Awareness in Entrepreneurship Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.C.; Ho, S.J.; Zheng, W.H.; Shu, Y. To Know, Feel and Do: An Instructional Practice of Higher Education for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.S.; Liu, Y.; Dai, J.; Chuang, Y.C. A Novel Improvement Strategy of Competency for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) of University Teachers Based on Data Mining. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.-E.; Kan, T.-Y. A Comprehensive Review of Environmental, Sustainability and Climate Change Curriculum in Taiwan’s Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 25, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schina, D.; Esteve-González, V.; Usart, M.; Lázaro-Cantabrana, J.L.; Gisbert, M. The Integration of Sustainable Development Goals in Educational Robotics: A Teacher Education Experience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, T.L. Higher Education in the Sustainable Development Goals Framework. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, A.D. The Critical Role of Higher Education in Creating a Sustainable Future Higher Education Can Serve as a Model of Sustainability by Fully Integrating All Aspects of Campus Life. Need for a New Human Perspective. Plan. High. Educ. 2003, 31, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mader, C.; Mahjoub, B.; Breßler, K.; Jebari, S.; Kümmerer, K.; Bahadir, M.; Leitenberger, A.-T. The Education, Research, Society, and Policy Nexus of Sustainable Water Use in Semiarid Regions—A Case Study from Tunisia. In Sustainable Water Use and Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, W.L. About the Role of Universities and Their Contribution to Sustainable Development. High. Educ. Policy 2011, 24, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suguna, M.; Sreenivasan, A.; Ravi, L.; Devarajan, M.; Suresh, M.; Almazyad, A.S.; Xiong, G.; Ali, I.; Mohamed, A.W. Entrepreneurial Education and Its Role in Fostering Sustainable Communities. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N. (Snowy) Teacher Education and Education for Sustainability. In Learning to Embed Sustainability in Teacher Education; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp. 7–21. ISBN 978-981-13-9536-9. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Wu, Y.C.J.; Brandli, L.L.; Avila, L.V.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Caeiro, S.; Madruga, L.R.d.R.G. Identifying and Overcoming Obstacles to the Implementation of Sustainable Development at Universities. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2017, 14, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Suresh, M. Synergizing Education, Research, Campus Operations, and Community Engagements Towards Sustainability in Higher Education: A Literature Review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1015–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, J.; Rodrigues, J.L. A Whole-Institution Approach Towards Sustainability at NOVA University: A Tangled Web of Engagement Schemes. J. Sustain. Perspect. 2023, 3, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Alhakim, A.D.; Grace, X.; Alam, M.; da Rocha Brando, F.; Braune, M.; Brown, M.; Côté, N.; Romano Espinosa, D.C.; Garza, A.K.; et al. Odd Couples: Reconciling Academic and Operational Cultures for Whole-Institution Sustainability Governance at Universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 24, 1949–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlouhá, J.; Henderson, L.; Kapitulčinová, D.; Mader, C. Sustainability-Oriented Higher Education Networks: Characteristics and Achievements in the Context of the UN DESD. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4263–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioupi, V.; Voulvoulis, N. Education for Sustainable Development: A Systemic Framework for Connecting the SDGs to Educational Outcomes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, M.; Sanchis, R. Sustainable Development Goals Integrated in Project-Based Learning in the Mechanical Engineering Degree. In Proceedings of the 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Online, 8–9 March 2021; pp. 7480–7487. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, T.L. Competencies and Pedagogies for Sustainability Education: A Roadmap for Sustainability Studies Program Development in Colleges and Universities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnert, J.; Sinclair, M.; Dewberry, E. Sustainable and Responsible Design Education: Tensions in Transitions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak-Andersen, M. Reintroducing Materials for Sustainable Design; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781003109525. [Google Scholar]

- Obiols, A.; De Eyto, A.; Mahon, M.C.; Bakirlioglu, Y.; Segalas, J.; Tejedor, G.; Lazzarini, B.; Crul, M.; Joore, P.; Wever, R.; et al. Circular Design Project-Open Knowledge Co-Creation for Circular Economy Education. In Proceedings of the Responsive Cities Symposium 2019, Barcelona, Spain, 15-16 November 2019; pp. 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K.; Dewberry, E. Demi: A Case Study in Design for Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2002, 3, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, L.; Franceschi, R.B.; Ferreira, A.M. Sustainable Collaborative Design Practices: Circular Economy and the New Context for a Fashion Designer. In Advances in Social and Occupational Ergonomics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zainudin, A.Z.; Yunus, N.M.; Zakaria, S.R.A.; Mohsin, A. Design for Sustainability Integration in Education. In Design for Sustainability Green Materials and Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valusyte, R. Towards a Systemic Approach. A Conceptual Framework For circular Design in the Transition of a Sustainable Economy. In Proceedings of the 10th SWS International Scientific Conference on Arts And Humanities—ISCAH 2023, Albena, Bulgaria, 23–25 May 2022; Zinkiv, I., Sparitis, O., Eds.; SGEM World Science: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, A.E.; Archambault, L.M.; Foley, R.W. Sustainability Education Framework for Teachers: Developing Sustainability Literacy through Futures, Values, Systems, and Strategic Thinking. J. Sustain. Educ. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Micklethwaite, P. Sustainable Design Masters: Increasing the Sustainability Literacy of Designers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of Design for Sustainability: From Product Design to Design for System Innovations and Transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Shen, J.-P. Higher Education for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Baxter, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Straus, S.E.; Wickerson, L.; Nayar, A.; Moher, D.; O’Malley, L. Advancing Scoping Study Methodology: A Web-Based Survey and Consultation of Perceptions on Terminology, Definition and Methodological Steps. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashimbye, Z.E.; Loggenberg, K. A Scoping Review of Landform Classification Using Geospatial Methods. Geomatics 2023, 3, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Cant, R.; Kelly, M.; Levett-Jones, T.; McKenna, L.; Seaton, P.; Bogossian, F. An Evidence-Based Checklist for Improving Scoping Review Quality. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2019, 30, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosse, V.; Oldoni, E.; Gerardi, C.; Banzi, R.; Fratelli, M.; Bietrix, F.; Ussi, A.; Andreu, A.L.; McCormack, E. Evaluating Translational Methods for Personalized Medicine—A Scoping Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaab, E.; Rauschenberger, A.; Banzi, R.; Gerardi, C.; Agudelo Garcia, P.A.; Demotes, J. Biomarker Discovery Studies for Patient Stratification Using Machine Learning Analysis of Omics Data: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e053674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, H.; van Mossel, C.; Scott, S. Enhancing the Scoping Study Methodology: A Large, Inter-Professional Team’s Experience With Arksey and O’Malley’s Framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmer, N.K. Unsettling Knowledge Synthesis Methods Using Institutional Ethnography: Reflections on the Scoping Review as a Critical Knowledge Synthesis Tool. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 2361–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Pollock, D.; Khalil, H.; Alexander, L.; Mclnerney, P.A.; Godfrey, C.; J Peters, M.D.; Tricco, A.C. What Are Scoping Reviews? Providing a Formal Definition of Scoping Reviews as a Type of Evidence Synthesis. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.E.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Allen, P.; Peckham, S.; Goodwin, N. Asking the Right Questions: Scoping Studies in the Commissioning of Research on the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2008, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikako, K. Evidence-Informed Stakeholder Consultations to Promote Rights-Based Approaches for Children With Disabilities. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2024, 5, 1322191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A.; Halvorsrud, L.; Linnerud, S.; Grov, E.K.; Bergland, A. The James Lind Alliance Process Approach: Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.; Downie, A.P.; Ristevski, E. Mapping Palliative and End of Care Research in Australia (2000–2018). Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]