Uncertainty and Entrepreneurship: Acknowledging Non-Optimization and Remedying Mismodeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

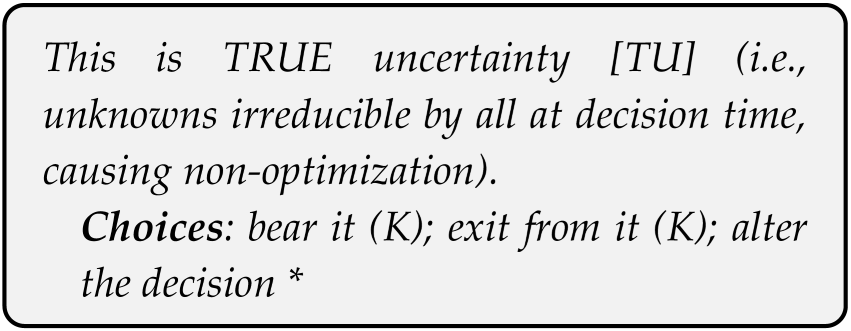

2.1. True Uncertainty

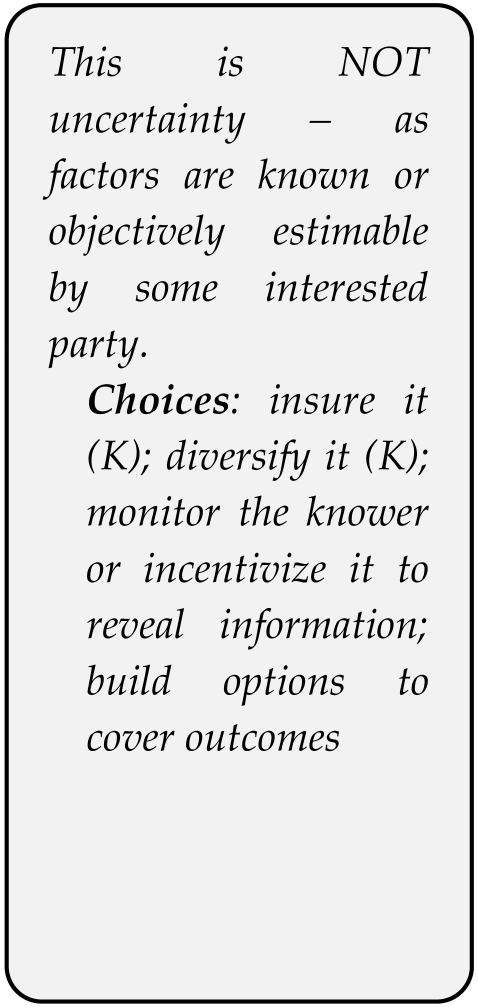

2.2. Knightian Uncertainties

2.3. True Uncertainty in the Entrepreneurship Model

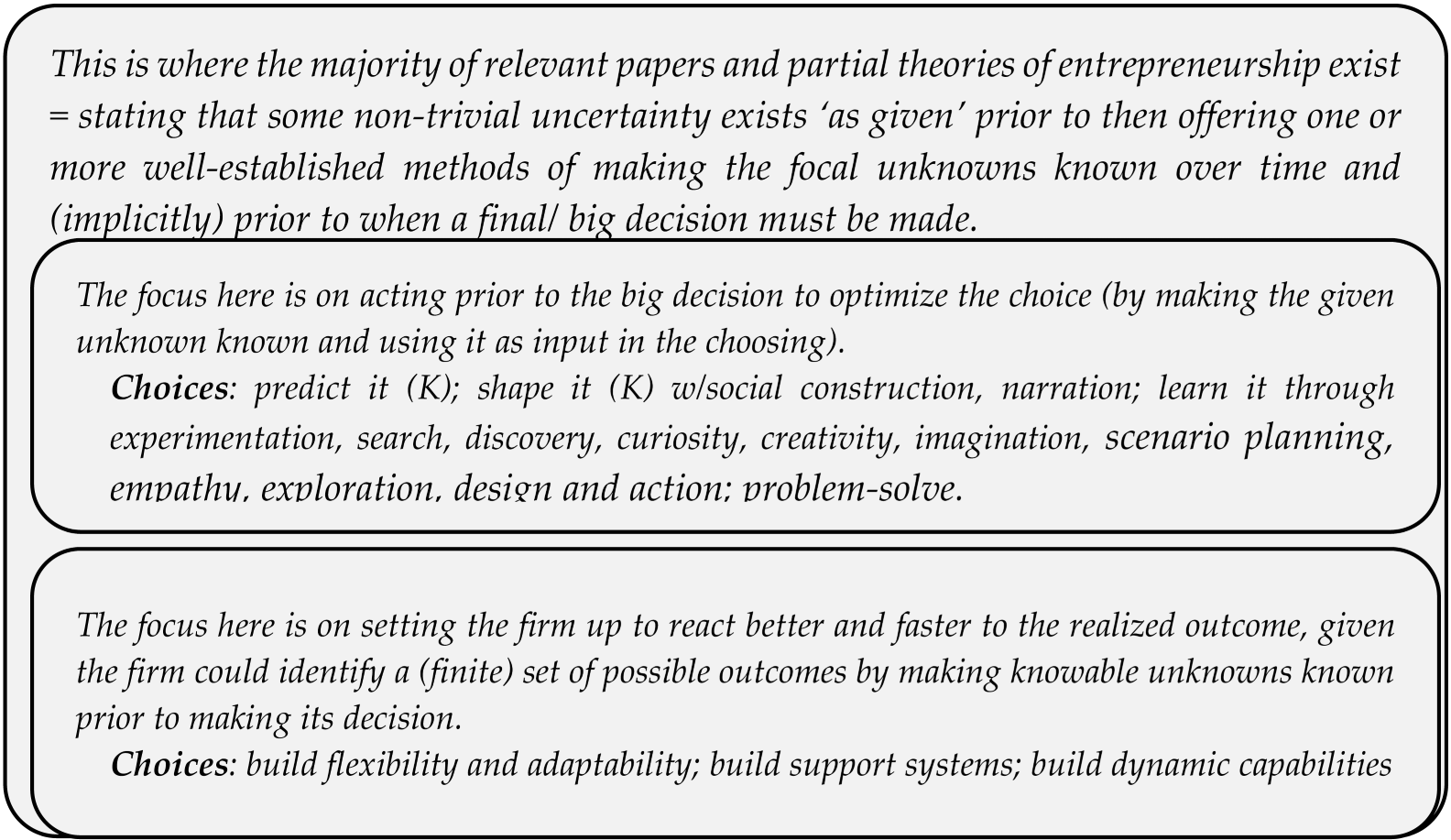

3. Assessing the Recent Resurgence of Work Addressing Uncertainties

3.1. The Need to Target Theory Pieces

3.2. How Papers Are Targeted

3.3. True Uncertainty Work in the Entrepreneurship Field

3.4. Interpreting the Analysis Results

3.5. True Uncertainty in the Current Set of Partial Theories of Entrepreneurship

4. Consequent Remedies

5. A Concluding Perspective

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A few clarifications: In the real world, making the reductions can be meaningful, but that is not what we are concerned about for this paper focused on uncertainty theorizing. Note that just because the focal decision is non-optimizable due to one or more irreducible unknowns, that does not mean that anything else is unknown. And just because the decision is non-optimizable does not mean it cannot be acted upon—e.g., Knight is explicit that entrepreneurs can ‘bear’ TU by acting on the decision regardless, and hoping for the best. |

| 2 | In micro-economic models, this heterogeneity is often embodied in asymmetric costs or in constrained choices based on historic conditions (e.g., as with Judo tactics being viable due to single-price markets—see [5]). |

| 3 | Note that the asymmetry here arises not from any directly assumed ex ante heterogeneity between the focal entrepreneur and its rivals; instead, it arises from the fact that TU’s non-optimizability produces different choices among the decision-makers willing to bear it given the theoretically infinite set of actions a firm could take in light of an unknowable future, where no one choice is guaranteed a better expected result than the other (of the set of possible actions remaining after all dominated options and arbitrages are eliminated). |

| 4 | When a decision (e.g., over a possible investment) can be made using standard operating procedures (e.g., using prediction, control, or options-building), or can be covered through insurance, diversification, sharing agreements, or any other means normally available to an incumbent, then the incumbent should have an advantage over the new entrant, all else being equal. However, when all else is not equal—when asymmetries exist between an entrant and incumbents, like that a possible failure of a risky investment entails more negative spillover to the incumbent, or the entrepreneur’s bankruptcy costs are lower, or the internalizable learning costs are higher to the incumbent (see [6])—then entry may still be possible even without TU. |

| 5 | An exception is the detailed typology described and tabled in Arend’s [8] new book on uncertainty. |

| 6 | That is not to say that the ultimate actions could not differ amongst decision-makers. For example, although the randomization mechanism over a choice may be the same (e.g., all firms roll a multi-sided die), luck would provide differences in the actual choices enacted. This is what we explained in the TU-based entrepreneurship story regarding it not requiring a separate heterogeneity assumption. |

| 7 | This situation differs in the real world—a world full of market failures and heterogeneity—where it is expected that each firm would likely have a different version of an optimal solution, one that seeks to maximize its own unique set of costs, utility, and so on. |

| 8 | These are separate things. Any author can have multiple ideas, even conflicting ones, across papers, making it inappropriate to conflate the two. Furthermore, it is a paper’s idea that is normally the reason for a citation, not the author, and so it is the former that is clearly the focus of any assessment here. |

| 9 | We assume honorable intentions of our peers, given we are all striving to increase the understanding of uncertainty. So, when we raise concerns with recent work, we do so knowing unintended errors can occur and real disagreements over premises can arise. Uncertainty is a complex phenomenon, and so, for example, an offered analysis and prescription can sometimes confound an abstract, theoretical context with the real, practical one. Further, given most of the recent papers draw on Knight’s [2] work, and given he is inconsistent in his use of the term uncertainty in that book—at times referring to, or implying TU, and at times not—we can understand some confusion over terminology and definitions. |

| 10 | Even Knight [2] waffled back and forth between the hypothetical and the real (e.g., regarding observed uncertainty—p. 317). |

| 11 | Even the most recent relevant work does little to clarify such issues. While it is good that some research appears to recognize that there are uncertainties that are untreatable [17], most other research has ignored fundamental concerns and instead been swept up in the ‘so what does this mean for AI?’ calls for opinion pieces [1,18]. While interesting, such uncertainty+AI papers appear to suffer from two problems: first, they fail to seriously consider the should-have-been-predicted ethical problems that AI can pose (e.g., the Facebook algorithm’s culpability in the 2016/17 Myanmar atrocities—see [19]); and, second, they fail to recognize research outside their micro-tribe (e.g., as each chose not to cite a recent book chapter specifically tackling the relationship of uncertainty to AI—see [8]). |

| 12 | Note that there are two alternative actions also listed in this cell. The first—exiting from a TU—does not directly address the problem; it just offers a way out of the problem for a decision-maker (i.e., it only offers a way of dealing with the situation of having the problem—but with not the problem itself). The second—altering the problem to a wholly different problem that is addressable—also does not address the original problem. For example, changing the goal from optimization to maximin—because the available information is available for the latter but not the former—does not actually address the given problem, it just changes the situation. Note that altering the problem is only pursued when it is likely to benefit at least one party vexed by the original problem (net of the costs to doing so); game theory provides a wide and deep literature on how to alter many decisions in beneficial ways [20]. But to be clear, it does not make the original unknowns known but instead substitutes knowables for the unknowns. Also note, no paper assessed here says it is explicitly solving a different problem, implying instead it is solving the original (TU-vexed) problem, which it is not. Finally, note that some research does exist that is explicit on how such uncertainty-vexed problem-altering can work in specific instances [21]. |

| 13 | Perhaps one step towards addressing some of these concerns about how TU is considered in the literature is for the affected fields to begin to be more accepting of theoretical models that involve assumptions that lead to the impossibility of an optimal problem treatment. Such logically coherent but uncomfortable (e.g., Pareto-inefficient) outcomes are not unusual in micro-economics—where they are observed in many expanding-pie games and rivalry models, including the prisoner’s dilemma. This would be a healthier stance to take than the current one, which seems to point at real-world situations where better-than-expected outcomes are achieved, even if solely by luck, and then promoting theories that try to explain it but cannot (e.g., because TU is involved). |

| 14 | We believe that providing clarity begins with agreeing on and enforcing a sharp, over-arching definition for TU, like the one we have suggested, followed by a categorization of phenomena within that definition. TU types could be defined by what the unknown thing is that is causing the non-optimizability of the decision, and that would be useful, assuming that with more knowledge about what is known and not known about the decision comes a greater the understanding is of what can and cannot be achieved with it, as holistic systems thinking advises. There have been attempts at such a typology in recent journal papers [3] but the most comprehensive and clearly delineated one appears in a book [8]. |

| 15 | One way to deter this kind of questionable science would be to improve accountability for those involved. But that is difficult for an academia that has no professional certification, no governing board with any power to discipline its members, and no top journals with paid, professional editors. So, such behavior is expected to continue, if not worsen, with public trust in our research justifiably eroding as a result [24,25]. We have a scientific (and often a public service) responsibility to do better. We should individually and collectively use pressures and policies to mitigate the harmful behaviors in our journals, academies and institutions, in order to defend the sanctity of science with its fundamental premise of seeking truths that lead to deeper understandings of the mechanics of focal phenomena, and to more efficient means to predict and control outcomes. |

| 16 | Such models include patent races, ones that are often mathematically depicted in memoryless Poisson, or in cumulative, or in multi-stage structures, many of which enjoy empirical support. |

| 17 | If we are going to focus on ‘treating the treatables’ and implying that the treatment can be successful, then we must also model the competitive game involved to explain who will win and why, given other firms will also apply the same treatment. Note that such an exercise often requires a whole other paper (e.g., Gavetti et al. [32] provide an example of a model of competitive shaping using an NKES/NKC landscape simulation, but even it remains a long way from dealing with anything deeply uncertain, given it assumes rational agents, static choices among known values performed sequentially, and predictable outcomes [given the model itself proves that the path and equilibrium are predictable and not uncertain]). |

References

- Townsend, D.M.; Hunt, R.R.A.; Rady, J.; Manocha, P.; Jin, J.H. Do Androids Dream of Entrepreneurial Possibilities? A Reply to Ramoglou et al.’s “Artificial Intelligence Forces Us to Rethink Knightian Uncertainty”. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2024; epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Packard, M.D.; Clark, B.B.; Klein, P.G. Uncertainty types and transitions in the entrepreneurial process. Organ. Sci. 2017, 28, 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoglou, S. Knowable opportunities in an unknowable future? On the epistemological paradoxes of entrepreneurship theory. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, J.R.; Salop, S.C. Judo economics: Capacity limitation and coupon competition. Bell J. Econ. 1983, 14, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Garrett, R.P.; Kuratko, D.F.; Bolinger, M. Internal corporate venture planning autonomy, strategic evolution, and venture performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, F.J. Three types of perceived uncertainty about the environment: State, effect, and response uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, R.J. Uncertainty in Strategic Decision Making: Analysis, Categorization, Causation and Resolution; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.G. Uncertainty and entrepreneurial judgment during a health crisis. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2020, 14, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries, P.; Debackere, K.; Van Looy, B. Simultaneous experimentation as a learning strategy: Business model development under uncertainty—Relevance in times of COVID-19 and beyond. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2020, 14, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez Roche, G.A.; Calcei, D. The role of demand routines in entrepreneurial judgment. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, D.J.; Olbrich, M. From Knightian uncertainty to real-structuredness: Further opening the judgment black box. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2023, 17, 186–209. [Google Scholar]

- Miozzo, M.; DiVito, L. Productive opportunities, uncertainty, and science-based firm emergence. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 539–560. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, R.W.; Packard, M.D.; Clark, B.B. Distinguishing unpredictability from uncertainty in entrepreneurial action theory. Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 60, 1147–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Brattström, A.; Wennberg, K. The entrepreneurial story and its implications for research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2022, 46, 1443–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.R.; Hunt, R.A. The Challenge and Opportunity of a Quantum Mechanics Metaphor in Organization and Management Research: A Response to Shelef, Wuebker, and Barney’s “Heisenberg Effects in Experiments on Business Ideas”. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2024; epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoglou, S.; Schaefer, R.; Chandra, Y.; McMullen, J.S. Artificial intelligence forces us to rethink Knightian uncertainty: A commentary on Townsend et al.’s “Are the Futures Computable?”. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2024; epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, Y.N. Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI; Signal: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburger, A.; Nalebuff, B. Co-Opetition; Broadway Business: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arend, R.J. Strategic decision-making under ambiguity: A new problem space and a proposed optimization approach. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, L.J. The Foundations of Statistics; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H.; Pascale, R.T.; Goold, M.; Rumelt, R.P. CMR forum: The “Honda effect” revisited. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 77–117. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Gabriel, Y.; Paulsen, R. Return to Meaning: A Social Science with Something to Say; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tourish, D. Management Studies in Crisis: Fraud, Deception and Meaningless Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arend, R.J. Mobuis’ Edge: Infinite Regress in the Resource-Based and Dynamic Capabilities View. Strateg. Organ. 2015, 13, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Arend, R.J. On the irony of being certain on how to deal with uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 702–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, R.J. Confronting when uncertainty-as-unknowability is mismodelled in entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2022, 18, e00334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, R.J. Uncertainty and entrepreneurship: A critical review of the research, with implications for the field. Found. Trends Entrep. 2024, 20, 109–244. [Google Scholar]

- Gavetti, G.; Helfat, C.E.; Marengo, L. Searching, shaping, and the quest for superior performance. Strategy Sci. 2017, 2, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.H.; Glosten, L.; Muller, E. Does venture capital foster the most promising entrepreneurial firms? Calif. Manag. Rev. 1990, 32, 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- Arend, R.J. SME–supplier alliance activity in manufacturing: Contingent benefits and perceptions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 741–763. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, M.B.; Montgomery, D.B. First-mover advantages. Strateg. Manag. J. 1988, 9, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, R.G. Falling forward: Real options reasoning and entrepreneurial failure. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

|

/Uncertainty Definition |

Uncertainty Explicitly Defined as Given ‘Irreducible’ Unknowns (or the Equivalent) |

Uncertainty Implicitly Involves Given ‘Irreducible’ Unknowns (Based on Either the Use of the KU Label and/or Has a Definition That Does Not Explicitly Rule Out TU) |

Uncertainty Defined by Reducible Unknowns (e.g., by Risk, Variance, Information Asymmetries or Other Contexts with Known Solutions) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamics | |||||

One-Shot/Focal Deadline (unknown remains unreduced) |  |  | |||

Delayed Decision Point (there is sufficient time for making any knowable unknowns known) | Focus on Actions Prior to Decision |  | |||

Focus on Reactions After the Decision (and its Outcome) | |||||

| Partial Theory | Brief Summary of Uncertainty in the Theory | Assessment of the Modeling and Suggestions for Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Action (EA) | Acknowledges that the future is unknowable (implying TU). EA = the willingness to bear perceived uncertainties (e.g., state, effect, response). Borne by applying judgment in a two-stage process, each stage involving learning and motivation. | This is a learning model. There are no unknowable unknowns assumed; so, this is not TU. Incumbents could also learn over time in the same way. More practical than theoretical in nature. When dealing with subjective but knowable unknowns, greater specifications over meaningful heterogeneity in perceptions and learning abilities of entities would be useful in the model. |

| Entrepreneurial Judgment | Uncertainty (labeled KU) as an unimaginable future (i.e., TU). An experimental process where what is unknown is a set of focal resource attributes. Dealt with by: intuition and gut feelings to anticipate the future; good judgment; heuristics; empathy; experimentation and learning. | The main process described is not judgment (i.e., acting on a guess) but instead learning about knowable unknowns; this is not TU. Mixes of approaches to knowable unknowns (e.g., experimentation) with approaches to unknowable unknowns (e.g., altering the problem to focus on a different maximand and applying a heuristic like maximin). Should separate theoretical and practical worlds better when modeling unknowns. Should separate the different unknowns more explicitly, especially regarding their suggested best treatments and who is likely to be advantaged in their use. |

| The Creation School | KU is the stated context (implying application to TU). Advises to address it by socially influencing/constructing/manipulating the given unknown factor (implied as mainly unknown demand). Involves a process that occurs over time, with experimentation and feedback-based learning. | This is a learning process; it only deals with a knowable unknown (made known by controlling/influencing its value); this is not TU. Should better define the kinds of unknowns at play and why they exist to be influenced—and why those who are influenced (i.e., those who embody the unknown) allow that to occur rather than exploit it themselves. Needs more specific modeling of the market failures at work, separating the theoretical outcomes from the practical advice and examples. |

| Effectuation | Uncertainty exists, at least at the perceptual level (so, may be TU). Best approached by a combination of: not planning (i.e., not trying to predict the unpredictable) but rather making do with the factors available; risking only affordable losses; and, co-creating/obtaining buy-in with others to share/reduce unknowns. Suggests practical advice for boundedly rational agents in a many-frictioned, poorly informed economy—with a stark contrast to business planning. | This is a process model = a learning approach that takes time and multiple actions, with feedback. This does not deal with a final decision made under unknowns (i.e., this is not TU). Should address many outstanding issues, including: Acting without any goals or foresight is myopic and can have costs as well (e.g., lock-out) that seem ignored. Predicting what losses are possible is still predicting the unpredictable. There is no direction on dealing with residual rights should surprises occur. If this is trying to be a theory, then it needs to focus on one decision and fully specify the potential rivals, partners and customers involved. |

| Small Worlds | Subjective beliefs are sufficient to provide an estimate for any unknown factor [22]. Effectively converts uncertainty to risk. Learning may also occur, involving Bayesian updating of the initial beliefs. | There is no legitimate basis for such beliefs in a real (‘large’) world when the target of concern in the decision is an unknowable. Note, when the subjective beliefs are simply intuition and non-reasoned knowledge or guesses, then that is the same as luck. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arend, R.J. Uncertainty and Entrepreneurship: Acknowledging Non-Optimization and Remedying Mismodeling. Systems 2025, 13, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13030214

Arend RJ. Uncertainty and Entrepreneurship: Acknowledging Non-Optimization and Remedying Mismodeling. Systems. 2025; 13(3):214. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13030214

Chicago/Turabian StyleArend, Richard J. 2025. "Uncertainty and Entrepreneurship: Acknowledging Non-Optimization and Remedying Mismodeling" Systems 13, no. 3: 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13030214

APA StyleArend, R. J. (2025). Uncertainty and Entrepreneurship: Acknowledging Non-Optimization and Remedying Mismodeling. Systems, 13(3), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13030214