1. Introduction

The production stage is a critical phase in the crankshaft lifecycle, significantly impacting overall equipment effectiveness and on-time delivery. Problems in management and scheduling can induce production deviations. These deviations typically manifest as delivery delays, quality defects, and resource idleness during production execution [

1]. To enhance production efficiency and reduce workshop operation deviations, manufacturing enterprises have implemented various production control and improvement activities. However, most scheduling optimization initiatives suffer from inherent blindness [

2,

3], primarily due to the difficulty in determining priority concerns within complex manufacturing processes—termed Critical Control Points [

4]. The failure of one or more control points can trigger systemic disruption [

5]. Multi-task pressure and resource contention on the shop floor deplete production capacity, resulting in dispatchers’ reduced recognition rate of hidden bottlenecks [

6]. This performance degradation propagates through the chain “control point bottleneck → scheduling delay → target deviation,” ultimately materializing as product quality loss or resource waste [

7,

8,

9].

Existing research on critical point identification has primarily followed two trajectories. One stream treats it as a multi-criteria decision-making problem, asserting that a control point’s importance is determined by its intrinsic attributes such as failure rate, severity, and handling difficulty. The core methodology involves establishing a control point indicator system to score and rank their importance, thereby identifying top-ranked points as critical. For instance, Ouyang et al. developed the QCAC model and employed the entropy-TOPSIS method to measure control point characteristics and rank them [

10]. Li et al. proposed a two-phase bi-objective feature selection method to extract key quality characteristics from imbalanced production data [

11]. While these methods can account for the intrinsic importance of control points, they largely overlook the complex interrelationships and structural dependencies within the production system. However, Yu et al., through characterizing the manufacturing process of internal combustion engine main bearing caps, revealed that relationships between control points and production deviations extend beyond simple vertical mappings to include lateral associations—cascading failures and lateral risk transmission among failed control points [

12]. Consequently, identifying Critical Control Points through explicit superposition of individual factors is inadequate. It is imperative to consider complex nonlinear interactions between control points and conduct an in-depth analysis of their interplay from a network perspective. Some scholars began recognizing production systems as complex networks, where control points are not isolated but form an interconnected complex network. In this context, a control point’s importance depends not only on itself but also on its position within the entire production system and its functional relationships with other control points.

Therefore, another research trajectory emerges from systemic interdependence, emphasizing control points’ network positions and their impact on overall processes. Mohandes et al. integrated the Fuzzy Delphi Method and Fuzzy DEMATEL technique, utilizing safety accident data to construct relationship matrices between deviation causes and phenomena, identifying 6 main causes and 23 corresponding sub-causes from 47 identified causes [

13]. Alaeddini et al. employed a Bayesian network framework to train quality information from product production processes and potential root causes, demonstrating method effectiveness through simulation comparisons with approaches like neural networks and K-nearest neighbors [

14]. These network-based approaches excel at modeling topological influences but often face challenges. DEMATEL’s initial influence matrix relies entirely on experts’ domain knowledge, introducing subjectivity, while Bayesian networks require substantial data and assume specific probability distributions, limiting their applicability in data-scarce environments.

The two categories of methods mentioned above often struggle to effectively model both the inherent attributes of production factors and their complex interdependencies. To compensate for the shortcomings of single-method approaches, some studies have attempted to hybridize multiple techniques. For instance, weight analysis methods (e.g., entropy weight method, AHP) have been combined with network analysis methods (e.g., DEMATEL, Bayesian networks) to simultaneously consider the intrinsic importance of attributes and the topological importance of structures [

15,

16]. However, existing hybrid methods still suffer from three key limitations: (1) Most adopt a sequential paradigm—such as weight ranking first, then network analysis or network construction first, then node evaluation, where weights and network structure lack an iterative feedback mechanism. This fails to achieve a bidirectional, closed-loop optimization where weights refine the network, and the network optimizes the weights. (2) While network models can depict associations, methods like Bayesian networks have stringent requirements on data volume and distribution, leading to unstable performance with small-sample production disturbance data. (3) Existing approaches largely remain at the identification-evaluation stage. They fail to systematically translate the identified critical nodes and paths into executable, preventive scheduling instructions, thus lacking integration with production execution systems for closed-loop management.

In parallel, the rise in artificial intelligence has introduced advanced data-driven paradigms for production scheduling, most notably Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) [

17] and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [

18]. DRL agents can learn sophisticated scheduling policies through interaction with simulated or real environments, while GNNs excel at capturing complex relational patterns within production system graphs. These methods hold great promise for large-scale, highly dynamic scheduling problems. However, their direct application in high-value, low-volume precision manufacturing contexts, such as crankshaft production, faces significant hurdles. They typically require vast amounts of interaction data for stable training, which is scarce for rare but high-impact disturbances. Furthermore, their decision-making processes are often opaque “black boxes,” providing little explainable insight into why a control point is critical or how risks propagate—knowledge crucial for gaining operator trust and implementing root-cause corrections. Their computational complexity can also be prohibitive for real-time, edge-side decision-making.

Compared with the aforementioned methods, Association Rule Mining (ARM) can efficiently identify high-frequency patterns in large-scale manufacturing datasets, quantify association strength between production factors using multiple metrics, and visually reveal causal relationships within structurally complex multi-level networks. Due to these strengths, ARM has been successfully applied in domains such as power system fault analysis [

19], construction defect diagnosis [

20], environmental risk assessment [

21], aviation safety management [

22], and marine accident investigation [

23]. However, traditional ARM exhibits two major limitations when identifying critical production control points under small-sample conditions: first, it treats all transactional items equally, failing to account for differences in the importance of production factors such as delay duration and resource cost; second, it only captures co-occurrence relationships without inferring causal direction, leading to a large number of redundant rules with reversed logic, which significantly reduces mining efficiency in scheduling optimization contexts and results in inefficient use of data samples [

24]. Although Del Gallo et al. (2024) [

5] introduced weights to improve the Apriori algorithm, it did not effectively integrate causal directionality with network centrality metrics for a comprehensive evaluation. Similarly, Caricato et al. (2021) [

25] construct a self-learning mechanism based on an initial rule base and iterative techniques to reduce redundant rules and reverse logic, but this process requires additional time investment. Moreover, none of the aforementioned studies constructs the internal topological structure of the scheduling system. Consequently, they are unable to structurally assess nodes, which makes it difficult to identify low-frequency but high-risk nodes.

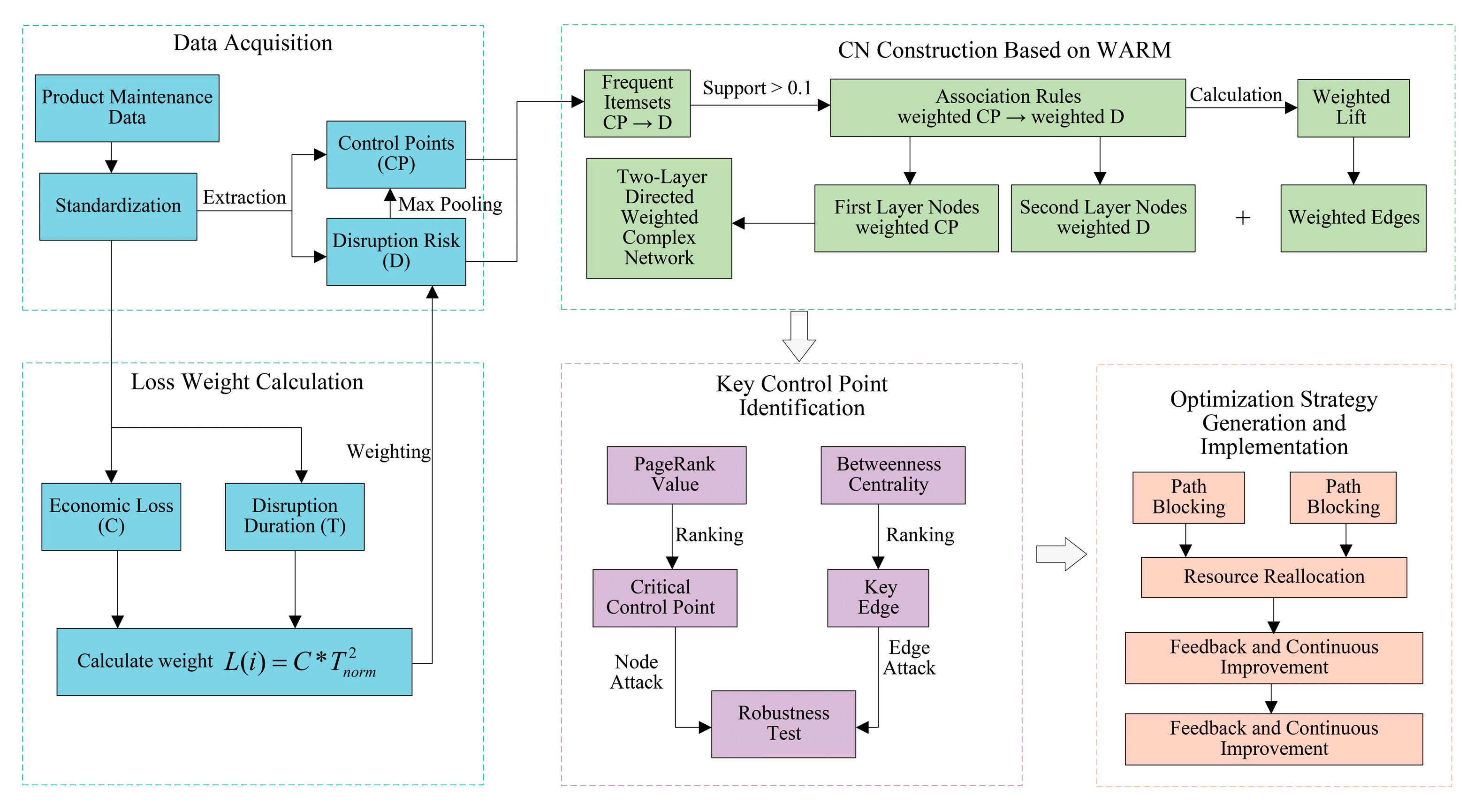

Therefore, to synergistically evaluate both the intrinsic attribute importance and the network structural importance of control points under small-sample conditions and to establish a proactive, prevention-oriented scheduling control link, this paper proposes a rule-constrained, data-driven integrated framework that combines Weighted Association Rule Mining (WARM) and Complex Networks (CN). This framework aims to occupy a distinct methodological niche; it is not designed to surpass the ultimate performance of DRL and GNNs in large-scale optimization but to provide an effective, transparent, and efficient solution for scenarios with limited data, a high demand for explainability, and a need for rapid causal insight. The core innovations of this study are as follows: First, the WARM-CN synergistic model is proposed. By constructing node weights based on a production loss function and embedding them into the directed association rule mining process, a two-layer directed weighted complex network is subsequently constructed. The structural importance of these weighted nodes and edges is then evaluated through metrics such as weighted PageRank and edge betweenness centrality. This synergistic integration mechanism enables our model not only to identify which control points are inherently critical but also to reveal which ones occupy strategically vital positions within the information propagation network, thereby providing a holistic solution for modeling complex associations in production systems. Second, an improved Apriori algorithm tailored for causality and small samples is designed. The causal directionality is ensured by constraining rule antecedents to control point types. Introducing node weights into the calculations of support and confidence metrics allows for the more effective highlighting of low-frequency yet high-impact associations within limited data. Third, a closed-loop management framework of disturbance feedback → causal mining → scheduling control is constructed. This framework directly maps the identified critical nodes and high-risk propagation paths to specific scheduling optimization strategies, realizing a complete technical pathway from system diagnosis to proactive intervention. The production management and intelligent scheduling closed-loop system is shown in

Figure 1.

3. Case Study: Model Validation in a Crankshaft Production Workshop

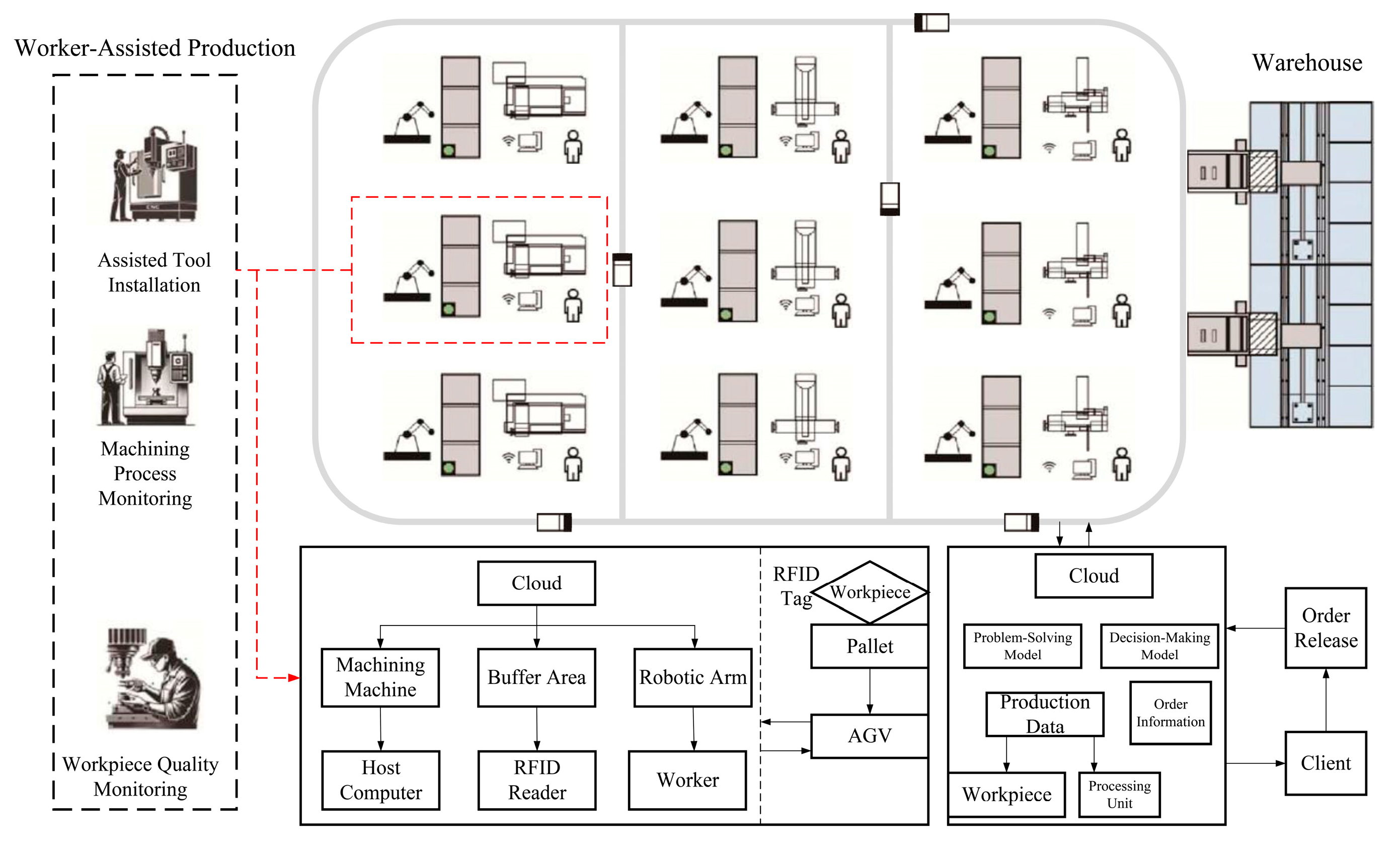

We validate the proposed WARM-CN model using a case study from a crankshaft production workshop. The crankshaft manufacturing process serves as a representative example of high-value, precision discrete manufacturing. It involves critical operations—including forging, milling, drilling, heat treatment, and grinding—all of which are characterized by stringent tolerance requirements and complex resource interdependencies. These characteristics make it highly susceptible to the scheduling disturbances and propagation effects that our model is designed to address. Therefore, this validation serves a dual purpose: it demonstrates the model’s applicability in a real-world setting while simultaneously using a representative scenario to underscore its potential generalizability to similar manufacturing contexts, such as the production of other critical components like camshafts, gears, or turbine blades. The crankshaft manufacturing workshop exemplifies such a scenario, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

3.1. Data Preprocessing

The model validation was conducted using a dataset comprising 406 historical production records, which were collected from the workshop’s Manufacturing Execution System. These records document instances of production disturbances, capturing a representative sample of the challenges encountered in high-precision mechanical component processing.

Two annotators were invited to review the maintenance records. They extracted key information from each record, including the workstation, disruption type, delay duration, root cause of disruption, and resource idle cost. The extracted information was then summarized from the format shown in

Table 1 into the structured format presented in

Table 2. The data schema in

Table 2 is designed to be generic and can be adapted to map disruption data in similar manufacturing environments.

To ensure annotation consistency, only phrases that were selected by both annotators were used to build the database for association rule mining. Through this standardized data extraction process, we obtained 381 valid information entries, resulting in an effective data retention rate of 94.0%. The entire process of data cleaning, annotation, and consistency verification took approximately 14 person-hours. Although this process incurs certain labor costs, it effectively ensures the data quality relied upon for subsequent analysis.

All subsequent algorithms were executed in the following computational environment: Windows 10 operating system, Intel Core i5-10300H processor, Santa Clara, CA, USA (2.50 GHz base frequency), 16 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060 GPU (6 GB VRAM). The algorithms were implemented in Python using the PyTorch 1.7.1 framework (CUDA 11.0). In this setup, the total runtime of the proposed model—starting from the reading of the processed 381 valid records—was approximately 0.3 s.

Guided by the proposed methodology, we defined a set of 25 production control points relevant to the crankshaft production context. These points, categorized into the six dimensions outlined in

Table 3, instantiate the general framework presented in this paper.

3.2. Association Rule Mining of Control Point

To uncover potential associations between individual control points and production disturbances, association rule analysis is performed on the preprocessed data.

3.2.1. Parameter Selection and Sensitivity Analysis

To validate the rationality of selecting max pooling for computing control node weights, we conducted a sensitivity analysis comparing it with three alternative statistical methods: the mean, median, and 90th percentile of the loss.

Using the same crankshaft production dataset, we replaced the max pooling step in Equation (3) with each alternative method and recalculated the control node weights. All subsequent steps remained unchanged. We then compared the resulting Top 10 rankings of critical control points and key network metrics. The comparison results are summarized in

Table 4. Ranking consistency was measured using the Jaccard index (overlap of Top 10 nodes) and the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ) relative to the max pooling baseline.

Maximum pooling and the 90th percentile method yielded highly consistent results, both successfully identifying the structurally critical node Mat1. In contrast, the mean and median methods failed to rank Mat1 within the top 5, instead prioritizing more frequent but structurally less central nodes. This demonstrates that methods sensitive to the upper tail of the loss distribution are crucial for capturing low-frequency, high-impact control points. The max-pooling method achieved the highest HLC, demonstrating that emphasizing maximum correlation loss more effectively guides the model to identify nodes whose failure would cause the most severe economic consequences.

In association rule mining, the support threshold filters out low-frequency itemsets, while the confidence threshold measures the reliability of the rules. Excessively high thresholds risk omitting important low-frequency yet high-impact rules, whereas overly low thresholds generate a large number of redundant and meaningless rules, which can interfere with decision-making.

To determine the optimal threshold combination, a grid search experiment was designed. Experiments were conducted using candidate sets for minimum weighted support (

) of

and for minimum weighted confidence (

) of

. The evaluation metrics included: the total number of strong association rules

, the average lift of the rules

, and the proportion of both high-frequency rules (support > 0.05) and high-impact rules (lift > 2.0). Key experimental results are summarized in

Table 5.

Combination 1 (0.01, 0.05) yielded the highest number of rules but the lowest average lift, containing many redundant rules with low support and confidence. While combinations 5 and 6 showed a slight improvement in rule quality (average lift), the total number of rules decreased sharply, potentially leading to the loss of critical information.

Combination 4 (0.02, 0.10) achieved the best balance among the number of rules, average lift, and the proportion of high-impact rules. Compared to Combination 2, it effectively filtered out 35.4% of low-frequency noisy rules by moderately increasing the support threshold, while simultaneously increasing the average lift by 15.3%. Compared to Combination 5, it preserved a more diverse set of rules, providing a richer foundational structure for network construction.

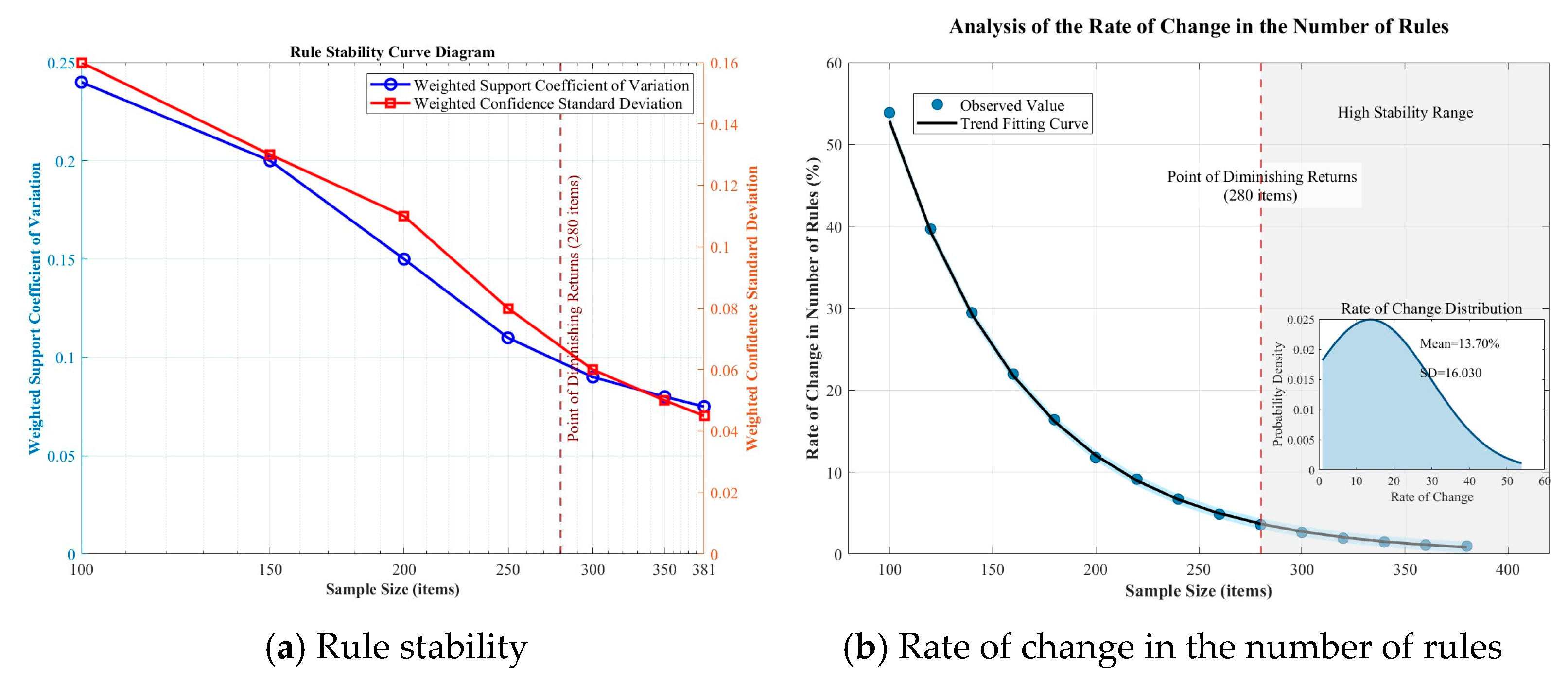

To further verify the stability of the algorithm’s output under these thresholds, a sample size sensitivity analysis was performed on the improved Apriori algorithm. Multiple subsamples were randomly drawn from the total dataset, and the mining process was repeated to observe changes in the coefficient of variation for weighted support and standard deviation for weighted confidence.

The rule stability and the rate of change in the number of rules for the improved Apriori algorithm under different sample sizes were analyzed, as shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6a shows that as the sample size gradually increases, the weighted support’s coefficient of variation and the weighted confidence’s standard deviation of the improved Apriori algorithm gradually decrease. When the sample size reaches 280, the coefficient of variation for support drops below 0.1, and the standard deviation for weighted confidence drops to 0.06, indicating high stability.

Figure 6b shows that as the sample size increases, the rate of change in rules significantly decreases. The point of diminishing returns, where the absolute value of the curve’s slope is first ≤0.05, occurs at 280 samples. Beyond this point, the improvement in stability from increasing the sample size is no longer significant, meaning the number of rules is relatively stable. The above results indicate that the improved Apriori algorithm performs well with small samples, and the 381 samples in this study are within the high stability range, ensuring high reliability of the results.

3.2.2. Association Rule Mining Results and Analysis

Using the determined thresholds (

= 0.02,

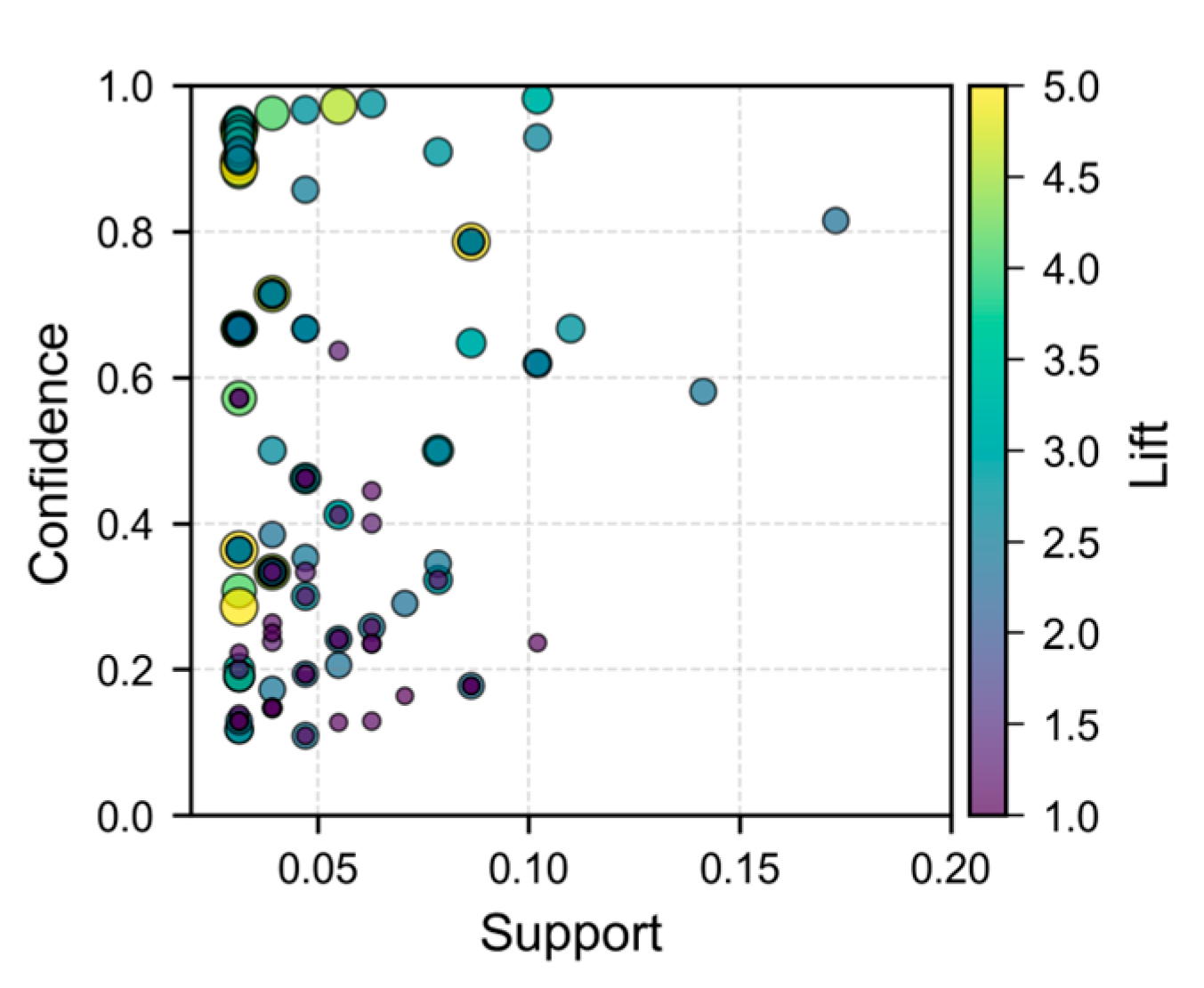

= 0.10), a total of 206 strong association rules were mined by applying the improved Apriori algorithm. The distribution of these rules is shown in

Figure 7. As can be seen from the figure, the association rules are mainly distributed in the range of weighted support from 0.02 to 0.1 and confidence from 0.1 to 0.4. At the same time, association rules with a higher lift are mostly distributed in sparse regions. This also demonstrates that our use of lift as the edge weight of the complex network can better mine low-frequency but very critical association rules.

Table 6 presents the top 10 association rules ranked by weighted support. Analysis of these rules reveals that the most significant associations primarily involve factors related to material flow (Mat), equipment status (Mac), and process methods (Met). For instance, the rule “Mat3 → LBL” indicates that deviations in Material Handling & Staging (Mat3) are strongly associated with Line Balancing Loss (LBL), demonstrating how material flow disruptions can directly impact production line efficiency and scheduling stability. This pattern exemplifies the critical role of logistical factors in triggering systemic production disturbances within intelligent manufacturing systems.

3.3. Complex Network Analysis of Critical Control Points

To prevent the occurrence of disruptions and quickly and effectively halt the evolutionary process of control point disruptions leading to faults, it is necessary to analyze the important nodes and edges in the network. In a complex system, nodes with greater global influence and faster information propagation speed are more important; this can be calculated through the node’s weighted PageRank value. For the edges in the network, those that are more conducive to information propagation and transmit more information are more important.

3.3.1. Important Nodes

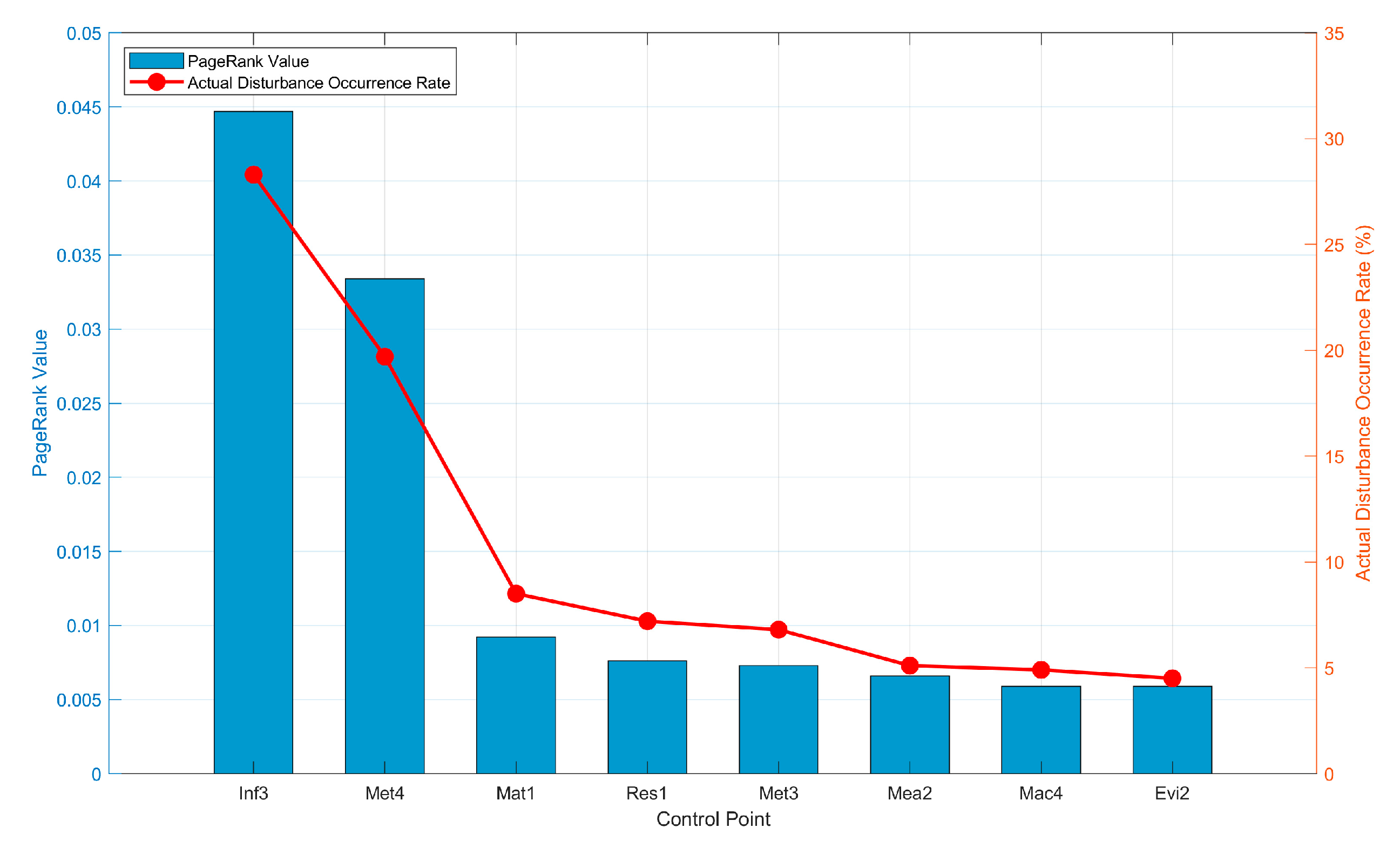

We ranked each control node based on its weighted PageRank value, and the ranking results are shown in

Table 7. As can be seen from the table, Scheduling Rule (Inf3), In-process Error Proofing (Met4), Material Arrival Timing (Mat1), Machine Status Monitoring (Res1), and Setup Time (Met3) all have relatively high PR values, indicating that these control points are more critical in the “Control Point-Disruption” network. Tool Life Management (Res2) and Gauge Management (Mea1) are ranked lower, indicating that these nodes occupy a less important position in the network.

Therefore, in the production management process of the machining workshop, resource allocation should be prioritized towards these high-PageRank control points. For instance, Scheduling Rule (Inf3) should be allocated more powerful computational resources and real-time data feeds, while Material Arrival Timing (Mat1) necessitates stricter supplier collaboration protocols and buffer inventory. In contrast, lower-ranked nodes like Gauge Management (Mea1) can be managed with more standardized, periodic maintenance protocols to optimize management costs. This differentiated resource allocation strategy, guided by node importance, enables the maximization of systemic stability under the ever-present constraint of limited managerial resources.

3.3.2. Important Edges

We ranked the influence transmission paths in the “Control Point-Disruption” (CP-D) network according to the edge betweenness centrality coefficient. The top 10 ranked edges are presented in

Table 8. Analysis reveals that the most critical propagation paths include: Material Arrival Timing (Mat1) → Line Balancing Loss (LBL), Scheduling Rule (Inf3) → Scheduling Delay (SD), Setup Time (Met3) → Line Balancing Loss (LBL), In-process Error Proofing (Met4) → Fixture Blockage (FB), and Vibration Environment Control (Evi2) → Quality Defect (QD). These edges represent the primary channels for disturbance propagation throughout the production network. When these critical paths are disrupted or blocked, both the global efficiency and average propagation path length of the network undergo significant changes, demonstrating their pivotal role in maintaining production system stability.

The interpretation of these topological findings reveals two archetypal high-risk scenarios prevalent in manufacturing systems:

First, the paths such as Mat1 → LBL and Inf3 → SD exemplify a Direct Systemic Impact pattern. These edges represent direct, high-impact causal relationships that bypass multiple intermediary steps. A deviation in Material Arrival Timing (Mat1), for instance, propagates not as an isolated delay but directly and efficiently triggers Line Balancing Loss (LBL), thereby disrupting production line harmony and causing widespread resource idling and order delays. This pattern identifies factors like material flow and scheduling logic as system leverage points, where control efforts yield disproportionately high returns for overall system stability.

Second, paths like Met4 → FB and Evi2 → QD demonstrate a Precision-Process Coupling mechanism. This pattern highlights the critical and direct linkage between precision-centric factors, such as fixtures and environmental controls, and core process outcomes. A lapse in In-process Error Proofing (Met4) directly and frequently manifests as Fixture Blockage (FB), leading to unplanned stoppages. Similarly, Vibration Environment Control (Evi2) acts as a direct precursor to Quality Defect (QD), underscoring that in precision manufacturing contexts like crankshaft machining, environmental stability transcends its conventional supportive role to become a fundamental quality constraint.

The practical implication is clear: proactive monitoring and control must prioritize blocking these identified high-betweenness paths. Instead of spreading resources thinly across all possible disruptions, management can now focus on ensuring the integrity of these specific causal links. This path-specific intervention strategy enables a more efficient and targeted allocation of limited maintenance and management resources to safeguard overall production stability.

3.4. Scheduling Optimization Strategy Based on Critical Control Points

After identifying critical control points, they must be translated into specific scheduling optimization instructions to enable proactive intervention. For core nodes with high weighted PageRank values, implement targeted direct control: First, dynamically optimize scheduling rules (Inf3) by intelligently switching between SPT, EDD, and other rules based on real-time equipment load and order urgency to suppress scheduling delay (SD); Second, enhance process error prevention (Met4) and equipment monitoring (Res1) by integrating online detection and predictive maintenance data into scheduling logic to preemptively mitigate quality defects and equipment downtime risks; Third, coordinate material timing (Mat1) by establishing supplier linkage and buffer mechanisms to ensure material flow aligns with production cadence, thereby reducing production line balancing losses (LBL) at the source.

To achieve closed-loop disturbance suppression, a “perception—diagnosis—decision—execution” scheduling framework can be established. This framework utilizes the WARM-CN model as its core analytical engine, converting continuously collected production data into real-time diagnostics for critical control points and high-risk paths. Based on these insights, the scheduling system automatically triggers predefined optimization strategies—such as path blocking and dynamic rescheduling—while feeding execution outcomes back into the database. This drives self-learning and continuous refinement of models and strategies, evolving scheduling governance from reactive response to proactive prevention.

To visually demonstrate the effectiveness of the WARM-CN method proposed in this paper for practical scheduling optimization, we selected a typical production scenario for analysis. This scenario involves the processing of three urgent orders (Order A, B, C) across four machines (M1, M2, M3, M4). After simplifying the workflow, the corresponding Gantt chart is shown in

Figure 8.

This production scenario encountered material arrival delays. Based on historical data, the method described here had already identified “Mat1” as a critical control point. Therefore, during scheduling, a flexible buffer was proactively designed for Order A. When materials arrived late, the scheduler did not rigidly execute the original plan. Instead, it swiftly activated a countermeasure: prioritizing the scheduling of processes C1 and C2 for the urgent Order C to ensure its on-time delivery; Simultaneously, processes for Orders A and B were decomposed and reorganized. Leveraging the parallel processing capabilities of M1, M2, and M3, resource conflicts were skillfully circumvented. The optimized schedule achieved high equipment utilization and smooth material flow. All orders were delivered on time or ahead of schedule.

While validated in a crankshaft production workshop, the WARM-CN framework is not limited to this specific context. The methodological steps, from data weighting and rule mining to network construction and centrality analysis, are domain-agnostic. The identified control point taxonomy and the analytical approach can be directly applied to other discrete manufacturing systems facing similar challenges of dynamic scheduling and disturbance propagation. This case study thus serves as a proof-of-concept for a generalizable model in intelligent manufacturing systems.

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Robustness Verification and Performance Analysis

4.1.1. Robustness Text

This section examines the robustness of the production disturbance network by sequentially attacking its nodes and edges, analyzing the resulting changes in network connectivity and performance. The objective is to evaluate the resilience of the production system and provide decision support for optimizing scheduling strategies and resource allocation.

- (1)

Node Attack

We implemented two distinct node attack strategies—random attack and deliberate attack—to assess their impact on network robustness. Random attack sequences were generated via Monte Carlo simulation, while deliberate attacks were executed based on node importance metrics, including weighted degree centrality, WLR values, and weighted PageRank centrality. The results of these attacks are illustrated in

Figure 9a.

Comparative analysis reveals that deliberate attacks degrade network connectivity more rapidly than random attacks, indicating that targeted disruption of key production control points can significantly compromise system operation. Among the deliberate attack strategies, the approach based on weighted PageRank values leads to the most rapid and comprehensive network breakdown, outperforming both weighted degree centrality and WLR-based strategies. This confirms that the weighted PageRank-based node ranking method is highly suitable for identifying critical nodes within the “Control Point–Disruption” (CP-D) causal network, providing a reliable basis for protecting pivotal production elements and enhancing overall system resilience.

- (2)

Edge Attack

We employed two distinct strategies to assess edge vulnerability: a Monte Carlo simulated random attack and a deliberate attack based on edge betweenness centrality ranking. The resulting changes in network robustness are documented in

Figure 9b. When 25 edges were disrupted, the global network efficiency decreased by 15.7% under random attack, compared to a more substantial 68.1% reduction under deliberate attack. This disparity arises because random attacks have a low probability of targeting critical propagation paths, whereas deliberate attacks systematically disrupt the most influential connections. Although edge attacks do not directly cause complete network fragmentation, they significantly impede information exchange between control points and disruption nodes, effectively blocking key disturbance propagation channels. Consequently, edge-based interventions serve as an effective auxiliary strategy when direct node protection is infeasible, enabling proactive containment of production disruptions and enhanced scheduling stability.

4.1.2. Model Performance Analysis

As shown in

Figure 10, the top four control points by weighted PageRank value (Inf3, Met4, Mat1, Res1) also rank highest in disturbance occurrence rates during actual production, accounting for 63.7% of all disturbance events. This high consistency (correlation coefficient R

2 = 0.86) validates the reliability of complex network-based node importance assessment methods in real industrial environments. Particularly noteworthy is that Scheduling Rule (Inf3) and In-process Error Proofing (Met4) demonstrate outstanding performance in both weighted PageRank values and actual impact dimensions, confirming their pivotal roles within the smart manufacturing scheduling system.

The most insightful finding in

Figure 10 is the unique position of the Material Arrival Timing (Mat1) node. Although its direct disturbance occurrence rate ranked only third (8.5%), far below Inf3 (28.3%) and Met4 (19.7%), its weighted PageRank value significantly exceeded subsequent nodes, exposing a fundamental flaw in traditional frequency analysis methods. Mat1’s low-frequency, high-impact characteristic stems from its structural advantage within the production network. When material arrival delays occur, they do not produce direct, high-frequency visible impacts like equipment failures. Instead, they trigger amplified negative effects at the system level through a cascading chain reaction: “resource bottleneck → scheduling delay → multi-workstation waiting.” The accurate identification of such hidden critical points represents a key advantage of the WARM-CN approach over traditional scheduling methods.

The case study results reveal patterns that are indicative of broader manufacturing principles. For instance, the identification of Material Arrival Timing (Mat1) as a highly weighted PageRank, low-frequency but high-impact node is a critical finding. Conversely, the high-frequency direct disruptors like Scheduling Rule (Inf3) represent a universal category of control points that are directly visible and often the focus of traditional management. Our model’s ability to uncover both types provides a more holistic risk assessment capability.

4.1.3. Ablation Study

To systematically evaluate the contribution of each component in the proposed WARM-CN integrated framework, an ablation study was conducted. The experiment constructed four comparative model configurations by sequentially removing core components. WARM-CN represents the model proposed in this paper. WARM-only removes the complex network analysis layer. ARM-CN employs traditional association rule mining without node weights but retains constraints on rule antecedents, using these to construct complex networks for analysis. This configuration tests the necessity of weight introduction. ARM-only uses traditional association rule mining without weights or antecedent constraints, representing the most basic association analysis method. This allows us to analyze the independent effects and synergistic interactions of weight loss, prior constraints, and complex network analysis.

As shown in

Table 9, comparing WARM-CN with WARM-only, after removing the CN layer, the HLC decreased by 20.5%, the disruption reduction effect weakened from 53% to 28%, and the improvement in delivery rate was halved. This directly proves that CN analysis is crucial for identifying structural hub nodes like Mat1, and such nodes are key to implementing efficient preventive scheduling and achieving substantial system-level performance improvements. Comparing ARM-CN with WARM-CN, after removing the loss weights, the model’s sensitivity to high-economic-loss disturbances decreased, leading interventions to focus more on high-frequency but less impactful nodes, thus resulting in limited effects on disruption reduction and delivery rate improvement. This indicates that introducing production loss weights is a necessary design to focus the model on high-economic-impact risks. Comparing ARM-only with other models, the basic ARM method, due to the lack of directional constraints, generated a large number of redundant rules, and the identified key points were mostly local high-frequency nodes, failing to effectively reflect system-level causal chains. Therefore, its actual effectiveness in scheduling optimization was the most limited. This highlights that constraining rule antecedents to strengthen causal logic is the foundation for enhancing the practical efficacy of the method.

The ablation experiment results show that the proposed WARM-CN integrated framework, through the organic combination of loss weights, antecedent constraints, and complex network analysis, achieved the greatest reduction in disruption rate and the greatest improvement in delivery efficiency. The absence of any core component leads to a significant degradation in model performance.

4.2. Theoretical Significance of This Study

This study proposes a data-driven production management and scheduling optimization model for intelligent manufacturing workshops based on an improved WARM-CN framework, establishing a theoretical foundation for subsequent research in this domain. Compared with existing studies, this research addresses several critical gaps in current methodologies.

First, regarding the research scope, this study transitions from traditional results-oriented analysis to a comprehensive production system perspective. We have established a structured approach for identifying factors that cause scheduling deviations and production disruptions in manufacturing systems. This enables the development of targeted scheduling optimization strategies and resource reallocation recommendations. More importantly, from a proactive prevention standpoint, it facilitates the strategic deployment of production management resources toward control points associated with high-impact, high-frequency disruptions. While previous research has examined production [

30], most studies have focused primarily on the impact of individual process parameters on quality characteristics at a micro-level, with research objects centered on post-disruption process mechanisms [

31,

32]. These approaches lack macro-level systematic investigation into proactive disruption control from a production system reliability perspective—a gap that this study effectively addresses.

Second, in terms of critical point identification accuracy, the WARM methodology developed in this study demonstrates superior adaptability to small-sample manufacturing data. Traditional ARM experiences significant accuracy degradation with sample sizes below 500, whereas our approach maintains robust performance. By incorporating production loss metrics, specifically delay duration and resource idle cost, to weight disruption nodes, and applying the max-pooling method to map these weights to the control point layer, we significantly enhance rule mining effectiveness. For instance, the confidence level for low-frequency, high-impact disruption rules Evi1 → SD increased to 0.04278, with the association rule strength ranking improving from 24th to 6th position. This demonstrates that meaningful, strong association rules can be reliably generated with only 381 production records. Furthermore, the improved Apriori algorithm with data type constraints proposed in this study achieves more accurate causal relationship identification in multi-level node networks. Compared with results derived from expert experience, this method enhances causal direction accuracy by 68.7% and reduces redundant rules by 35.4% relative to the unconstrained Apriori algorithm.

Third, in terms of research objectivity, compared to methods like DEMATEL or FMEA that rely on expert knowledge to define the initial matrix, the initial mapping matrix in this paper is automatically constructed from failure maintenance data. Manual intervention is only required in the standardized annotation stage. The subsequent steps of association rule mining and complex network PageRank sorting are completely data-driven, providing more accurate and scalable scheduling control decision support for the manufacturing system.

To empirically validate the advanced nature and uniqueness of the proposed WARM-CN framework, a comparative analysis was conducted with four representative methods. These methods include entropy-weighted TOPSIS, which relies on attribute data; traditional Association Rule Mining, which is based on undirected associations; Fuzzy-DEMATEL, a technique that integrates expert knowledge with systemic relations; and Graph Neural Networks representing the cutting-edge direction of artificial intelligence. The normalized importance assessments of the eight key control points by these methods are shown in

Figure 11.

The analysis indicates that the WARM-CN framework identifies critical control points from a comprehensive production system perspective. The results demonstrate its significant characteristic of balancing inherent attributes and network structure. Similarly to entropy-weighted TOPSIS and Fuzzy-DEMATEL, it confirms the importance of high-frequency, direct-influence factors such as Inf3 and Met4. Its core advantage, however, lies in uniquely identifying pivotal nodes like Mat1. Such nodes are severely underestimated in traditional attribute analysis and simple association analysis, yet they possess high propagation potency. This confirms the effectiveness of the bidirectional synergistic mechanism. This mechanism mines causal edges through weighted association rules and evaluates global network influence via weighted PageRank. Consequently, this framework provides a reliable decision-making basis for proactive and preventive scheduling optimization.

In contrast, the other methods exhibit clear limitations. Entropy-weighted TOPSIS is entirely confined to static attribute data and cannot perceive dynamic system interactions. Traditional Association Rule Mining suffers from a lack of directionality and generates redundant rules, leading to identification results that deviate from actual causal logic. Although the results from Fuzzy-DEMATEL are partially reasonable, its heavy reliance on expert knowledge introduces subjective uncertainty. The Graph Neural Network method possesses a powerful capability to capture complex patterns, but its decision-making process lacks interpretability. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 10, its importance assessments for some nodes exhibit fluctuations. This limits its applicability in production scheduling scenarios that require clear and explicit causal explanations.

4.3. Practical Value of This Study

This study offers practical value by providing manufacturing managers with a more precise and actionable framework for prioritizing scheduling optimization and disturbance management tasks. The WARM-CN model moves beyond traditional, often myopic, rules and expert-biased methods to deliver two key practical insights: first, it confirms and systematically ranks the well-known critical points (Inf3, Met4), and second, the modeling advantages of this framework under complex interdependencies can uncover and highlight the hidden yet systemically vital points (Mat1) and the most impactful propagation paths (Mat1→LBL). This enables a paradigm shift from reactive, blanket resource allocation to proactive, targeted interventions on the core nodes and pathways that truly govern system stability.

First, the node identification results demonstrate that Scheduling Rule (Inf3), In-process Error Proofing (Met4), Material Arrival Timing (Mat1), and Machine Status Monitoring (Res1) play decisive roles in the production disturbance network and represent the critical control points in the production management process. These findings align substantially with existing research [

33]. However, our study distinctively identifies Material Arrival Timing (Mat1) as an additional critical point. This divergence can be attributed to two key factors. First, previous studies often overlooked the topological characteristics of nodes within complex networks. Mat1 exhibits the highest betweenness centrality coefficient (0.164), indicating its frequent occurrence in the network’s shortest paths and its function as a bridge node connecting control points across equipment, methodology, and environmental dimensions. Disruptions at Mat1 would interrupt the propagation pathways of other factors. For instance, poor machine thermal stability (Mac4) leads to equipment downtime (ED) through material delivery delays (Mat1), forming a cascading path of “Mac4→Mat1→ED.” Identifying Mat1 as a critical production control point and preventing its disruption can effectively block the impact of poor thermal stability (Mac4) on equipment downtime (ED). Second, whereas previous studies primarily used node frequency as edge weight [

34], our approach incorporates association rules between nodes. Through the production loss metrics and max-pooling method, Mat1’s node weight significantly enhanced its PageRank ranking, elevating its importance above high-frequency, low-impact nodes. By using the product of node frequency and association rule lift as the edge weight in the disturbance network, our method considers not only the frequency and magnitude of risks associated with each control point but also their risk intensity. The combination of high PageRank nodes and high-betweenness “CP-D” node pairs constitutes the core structure of the production disturbance network.

Second, the edge identification results reveal that Mat1→LBL, Inf3→SD, Met3→LBL, Met4→FB, and Evi2→QD represent the most information-rich edges in the production disturbance network. When direct intervention at certain control points proves challenging, production stability can still be maintained by blocking these critical propagation paths. For example, a deviation in Machine Operating Precision (Mac3) (such as positioning inaccuracy or vibration anomalies) may cause imbalanced load distribution on production equipment, leading to accelerated tool wear (TWB), reduced processing accuracy, or even equipment shutdown. The direct interaction from Machine Operating Precision (Mac3) to Tool Wear Breakdown (TWB) can occur in a single step with 42.36% support. If direct measures at Mac3 are infeasible, but the connection between them can be interrupted, such that Mac3 can only affect Material Quality Consistency (Mat2), which then leads to tool wear breakdown (TWB), effectively changing the interaction path to Mac3→Mat2→TWB, the propagation process extends from one step to two steps.

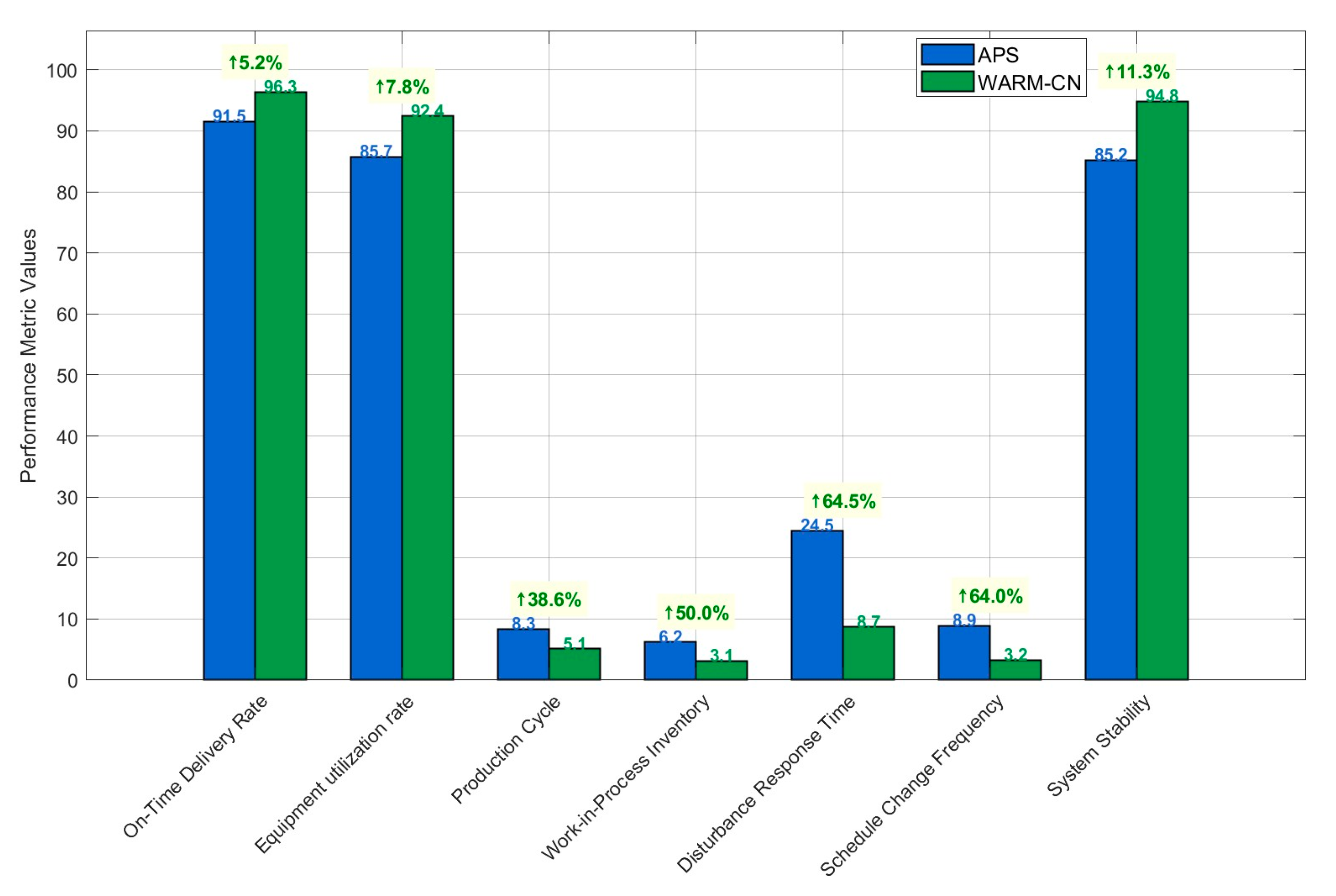

A three-month comparative experiment was conducted in two similar production workshops at a diesel engine crankshaft connecting rod mechanism manufacturing enterprise. Workshop A employed a traditional Advanced Planning and Scheduling system (APS), while Workshop B utilized the WARM-CN method proposed in this paper for intelligent scheduling optimization of production critical control points. Following targeted scheduling interventions at the top five identified critical control points (Inf3, Met4, Mat1, Res1, Met3), the occurrence rate of high-impact disturbances, defined as those causing delays exceeding 4 h or idle resource costs surpassing 3000 yuan, decreased by 53%. This substantial reduction confirms that precise management of critical control points can effectively enhance the scheduling stability and disturbance resilience of production systems. The performance comparison chart based on three months of workshop data is shown in

Figure 12. The WARM-CN method demonstrated significant advantages over traditional APS in the smart manufacturing environment: substantial improvements in core efficiency metrics like on-time order delivery rate and equipment utilization validated the effectiveness of preventive scheduling based on association rule mining. Meanwhile, the qualitative leap in disturbance response time and work-in-process inventory highlighted the unique value of complex network analysis in identifying hidden bottlenecks and blocking disturbance propagation paths.

The generalizability of this framework stems from its problem abstraction and methodological decoupling. First, the proposed six-dimensional control point taxonomy—Resource, Information, Measurement, Material, Process, and Environment—abstracts common elements of manufacturing systems. This abstraction allows it to be adapted to various contexts such as machining, electronic assembly, and chemical production. For example, in a semiconductor packaging workshop, the Environment dimension might be more critical. In assembly lines, Material Consistency and Tool Availability could become key antecedents. Second, the core algorithmic workflow—Data Weighting, Directed Rule Mining, Network Construction, and Centrality Analysis—constitutes an analytical paradigm relatively independent of domain-specific knowledge. The framework can be applied whenever a production loss function can be defined to quantify disturbance impact, such as quality loss, energy overconsumption, or safety risk. It also requires production logs to be transformed into binary transaction sets of Control Point-Disturbance pairs. For instance, in the chemical industry, Process Parameter Deviation can be treated as a control point, and Product Component Exceedance as a disturbance. The same method can then identify critical process control points and risk propagation chains.

5. Conclusions

This study addressed two core challenges in production management and scheduling for the crankshaft production workshop: inadequate modeling of complex interdependencies among production factors and inefficient knowledge extraction from small-sample operational data. By integrating system performance analysis with intelligent scheduling decisions, a closed-loop management framework of “disturbance feedback-causal mining-scheduling control” was established. A data-driven framework was proposed and validated, integrating weighted association rule mining with a dual-layer directed weighted complex network.

The primary contributions of this study are summarized in three key aspects: First, the impact of control point deviations was quantified by constructing a production loss function that integrates fault severity and maintenance costs. Second, the WARM algorithm was enhanced by restricting association rule antecedents to the control point layer and incorporating node weights into weighted support and confidence calculations. This significantly improved the ability to mine directed causal rules under small-sample conditions. Finally, effective identification of critical nodes and high-risk propagation paths was achieved by constructing a dual-layer directed weighted network and integrating weighted PageRank centrality with edge betweenness analysis.

Practical results demonstrated that interventions focused on identified critical production control points could reduce high-impact disturbance rates by up to 53%. Meanwhile, blocking high-order propagation paths enabled flexible and precise intervention against scheduling risks. This integrated WARM-CN methodology offers crucial theoretical and technical support for enhancing the scheduling resilience and operational efficiency of intelligent manufacturing systems.

The limitations of this study and future research directions are outlined as follows:

First, in constructing the production disturbance network, we primarily employed manual analysis methods for labeling and categorizing production log data. This approach not only lacks efficiency but may also introduce subjective biases during data interpretation, potentially affecting the accuracy of control point identification. Future research could apply text mining and natural language processing techniques to automatically analyze production records and maintenance reports. This would enable more objective and efficient identification of production control points and their associated disruption patterns.

Second, this study focused primarily on reducing system disruption rates as the single objective for critical point identification. While this provides clear operational guidance, practical production environments often require balancing multiple competing objectives. Future research should expand toward multi-objective optimization, simultaneously considering factors such as production efficiency, resource utilization, energy consumption, and operational costs. This will generate more comprehensive and practically viable production scheduling solutions that better reflect the complex decision-making environment of intelligent manufacturing systems.

Third, the validation in this study focuses on small-sample data environments, where the proposed WARM-CN framework demonstrates favorable stability and interpretability. However, its performance in industrial big-data environments requires further exploration. Future research will be dedicated to validating the accuracy and generalization capability of this method on larger-scale and more diverse production datasets. Specifically, we aim to investigate its potential in mining complex associative patterns, distinguishing subtle causal relationships, and handling high-dimensional features when the sample size increases significantly. This will not only provide a more comprehensive assessment of the method’s robustness but also offer a crucial basis for building scalable intelligent scheduling diagnostic systems adaptable to varying data scales. Furthermore, exploring the integration of this method with incremental learning techniques to enable dynamic model updating and evolution in scenarios with continuous data flow presents a promising direction for future work.