1. Introduction

To analyse the impact of taxation on economic growth at the level of the member states of the European Union, in the context of the common fight against the shadow economy and tax evasion, it is imperative to evaluate the negative implications of these phenomena and identify the measures adopted to combat them. Therefore, through this research, we aim to define the leading indicators that capture the level of the shadow economy, map the evolution of this phenomenon at the level of the European Union by comparing its values recorded over time, and measure the implications generated by actions of tax evasion on economic growth through regression analysis and a structural equation model.

This paper introduces several novel contributions to existing literature by offering a comprehensive and multifaceted analysis of the European Union, with a particular focus on the impact of the shadow economy and tax evasion on economic growth. While numerous studies have examined the shadow economy globally, few have provided a longitudinal, multi-method analysis across all EU Member States that integrates bibliometric insights, EU policy frameworks, and econometric modelling. This study addresses this gap by combining these dimensions to provide a comprehensive understanding of how the shadow economy interacts with growth dynamics in the EU.

First, the paper presents an innovative perspective by defining and tracking key indicators of the informal economy, shadow economy, and development variables, and mapping their evolution over time in EU Member States from 2000 to 2022. Unlike previous research, which often treats these economic activities separately and focuses only on one aspect of the informal economy, such as tax evasion or its global dimension, our paper integrates them into a broader economic framework to assess their collective impact on economic growth. By combining development variables and mapping these changes, the study offers new insights into the long-term dynamics of the informal economy, shadow economy and its relationship with economic growth.

Second, it introduces a unique empirical framework that combines bibliometric analysis, an overview of the European Directives, and advanced econometric techniques (regression analysis and structural equation modelling) to assess the impact of the informal and shadow economies on economic growth. This integrative approach—bibliometric analysis, policy review, and econometric modelling—enhances the robustness and reliability of the study’s findings, providing a more in-depth understanding of the complex relationships between the informal economy, the shadow economy, and economic growth, mitigating biases that may arise from relying on a single approach, ensuring a more comprehensive and accurate assessment. Concrete, our research underscores a significant challenge in studying the impact of the informal and shadow economy on economic growth: the lack of standardised, reliable, and publicly available data on these sectors.

Finally, the use of econometric analysis, including structural equation modelling (SEM) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression models, allows for a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships between various economic factors and the study of the implications of the shadow economy. Accordingly, the influence of the shadow economy requires a nuanced approach, considering both its positive contributions to economic activity and its negative consequences for long-term stability and growth. Unlike previous studies that rely solely on descriptive or correlation-based analyses, our econometric approach captures both the direct and indirect effects of the shadow economy, providing policymakers with essential insights for striking a balance between economic growth and regulatory control.

Previous literature has suggested that the shadow and informal sectors may act as both barriers and catalysts for economic growth. On the one hand, they can undermine fiscal capacity and distort market efficiency; on the other hand, they may serve as a buffer during economic downturns by generating employment and sustaining consumer spending. Given these conflicting perspectives, a structured set of research questions is necessary to clarify the direction and magnitude of these effects within the EU context:

RQ1: What is the impact of the shadow economy on economic growth across the European Union during 2000–2022?

RQ2: How does the informal economy differ from the shadow economy in influencing economic growth?

RQ3: To what extent do macroeconomic variables such as tax revenues, inflation, and foreign direct investment (FDI) mediate the relationship between the shadow economy and economic growth?

RQ4: Are there significant cross-country differences among EU Member States in the magnitude of the shadow economy’s effect on growth?

Addressing these questions allows for a more nuanced understanding of whether the shadow economy merely reflects structural weaknesses or plays an adaptive role in sustaining economic activity. The econometric analysis presented in this paper is designed to empirically test these relationships, using panel data for the 27 EU countries.

Based on the existing literature and preliminary descriptive results, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between the shadow economy and economic growth in EU Member States.

H2: The informal economy has a positive short-term impact on economic growth due to its role as a compensatory mechanism during periods of low formal employment.

H3: Inflation exerts an adverse effect on economic growth, while higher tax revenues and FDI are expected to contribute positively to growth.

H4: The magnitude and direction of the shadow economy’s impact on economic growth differ across EU Member States, depending on institutional and policy conditions.

Together, these hypotheses operationalise the conceptual framework into measurable relationships that are empirically tested in the econometric models previously proposed.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows: the next section examines the state of knowledge on the shadow economy and tax evasion at the EU level, while also discussing the leading national and European Strategies for preventing and combating tax evasion.

Section 3 presents empirical analysis, beginning with the methods and data presentation, followed by an exploration of the empirical results and discussions in

Section 4. The final section presents the main conclusions and outlines several strategies for preventing and combating tax evasion.

2. Literature Review

With an average of approximately 20% of GDP after 2000 [

1], the shadow economy at the EU level represents a significant proportion of revenues that remain undeclared or unrecorded, thereby reducing the tax revenues available at national levels. The Eastern European countries register the highest levels of the shadow economy, with a crucial size of the informal sector, i.e., almost one-third of the GDP. Countries with lower taxes and a more straightforward law and regulations framework tend to have smaller portions of shadow economies. This phenomenon is evident in the shadow labour market, where the primary driving forces behind the size and growth of the shadow economy are changes in wage rates or an increase in tax and social security payments [

2]. Additionally, the size of the shadow economy highlights a discrepancy between income and expenditure statistics in the national accounts, prompting governments to seek alternative revenue sources to finance public expenditures, particularly when applying policy rules in the context of a positive inflation rate. Therefore, we expect the size of the shadow economy to increase with the inflation rate and taxes to decrease accordingly [

3].

To achieve the development goal, policymakers require a sustainable flow of financial resources, including tax revenues, which are significantly influenced by the level of the shadow economy. Gnangnon [

4] emphasised the importance of revenue-enhancing structural tax reform, citing specific tax policies and areas of revenue administration. These are accompanied by high taxpayer morale and compliance, supported by expanding social services and public goods, reduced corruption, and trust in government institutions [

5].

Gnangnon [

4] also emphasised the importance of reforming the tax revenue structure, highlighting the role of international trade tax revenues, which is particularly relevant for countries with high trade openness levels. The likelihood of structural tax reforms is reduced in countries with large shadow economies. In addition, large shadow economies are associated with corruption and a low quality of public institutions, which undermines investors’ confidence and discourages foreign capital inflows [

6,

7,

8]. Accordingly, we expect foreign direct investments to influence the relationship between the shadow economy and economic growth and development.

To ensure high-quality, comprehensive analysis, the research relies exclusively on electronic data sources, including the scientific literature from the Web of Science Core Collection, the World Bank for development metrics (Gross Domestic Product per capita, Foreign Direct Investment, tax revenues, and inflation), and established databases for the informal economy and shadow economy, collected from to the research of Elgin et al. [

9] and Medina and Schneider [

1]. This approach is innovative and valuable because it moves beyond a static, one-time analysis and instead provides a dynamic, historical perspective on the evolution of informal and shadow economies, identifying patterns, long-term trends, and structural shifts that influence economic growth.

The contemporary challenges of tax administration, generated by the shadow economy and tax evasion implications, set the stage for this research by identifying the normative and institutional framework regarding tax administration at the national level. The scientific literature, legislation, internal regulations and specific norms were reviewed. In determining the issues of shadow economy and tax evasion at the European level, it was necessary to delimit the particular terms in the specialised literature conceptually, approaching quantitative methodologies for collecting information. Although the theoretical terms related to the fiscal nature of evasion are well-defined, there may be confusion regarding their substitution. Moreover, we also emphasise the leading indicators intended to measure the level of tax evasion within a state and the determining factors of tax avoidance.

The paper highlights the importance of clearly defining key terms such as “informal economy”, “shadow economy”, “grey economy”, and “unobserved economy”, which are often used inconsistently in existing literature. By addressing these conceptual ambiguities, the study ensures a more precise measurement and analysis of the informal economy, leading to clearer insights into its impact on economic growth. This approach enhances the reliability of findings and supports more effective policymaking in tackling tax evasion and shadow economic activities. Additionally, studying the European directives as a framework for mitigating tax evasion is crucial, as these directives offer a unified approach that considers the interconnected nature of EU economies. A fragmented or inconsistent approach to tax regulation could lead to loopholes that facilitate tax evasion. By analysing these directives, the paper identifies best practices and the effectiveness of coordinated actions in harmonising tax policies, as well as regulatory gaps.

The robust theoretical foundation of this paper rests on the integration of several established economic theories and frameworks, offering a comprehensive perspective on the relationship between the informal economy, tax evasion, and economic growth within the EU. Specifically, the Dual Economy Theory explains the coexistence of formal and informal sectors, helping to analyse how the shadow economy interacts with the official economy in different EU member states. Institutional Economics is crucial in assessing the impact of European Directives and national regulations on the effectiveness of tax compliance policies. Tax Evasion and Public Finance Theories provide insights into how informal economic activities undermine government revenues, fiscal policies, and economic stability, which is central to our study of tax evasion in the EU. Growth and Development Theory enables the assessment of long-term economic impacts, particularly by examining how informal activities affect GDP, foreign direct investment (FDI), and inflation. Additionally, Systems Theory helps capture the complex interactions between tax policies, regulatory frameworks, and economic behaviour. At the same time, Behavioural Economics explains the decision-making processes behind tax evasion and participation in the informal economy.

Another significant contribution of this study is its critical assessment of inconsistencies in the definitions of key terms such as informal, shadow, grey, and unobserved economies. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they encompass different aspects of economic activity. By highlighting these discrepancies, the paper sheds light on the challenges in measurement, analysis, and policymaking that complicate efforts to combat tax evasion and regulate the shadow economy effectively. Specifically, this paper begins with a theoretical framework based on bibliometric analysis, identifying the current state of knowledge regarding the concepts of the shadow economy and tax evasion. A database of scientific articles indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection was extracted, offering an impressive number of studies relevant to the basic concepts studied while meeting the most rigorous standards regarding the quality of the publications provided. The bibliometric analysis, conducted using the VOSviewer software—version 1.6.20, identified the most relevant articles in terms of quality and results obtained, while also mapping research-specific terminology and concepts related to the shadow economy and tax evasion, highlighting scientific production at the EU member state level. One of this study’s significant contributions stems from the identification of inconsistencies in the definitions of key terms, such as informal, shadow, grey, and unobserved economies, within the literature. Although related, these terms differ in their scope and focus, and the lack of clear boundaries between them can lead to confusion in understanding the scale and impact of these activities on the economy. The paper’s contribution lies in highlighting this issue, as such inconsistencies complicate the measurement, analysis, and policymaking processes, making it more challenging to develop effective strategies for addressing tax evasion and the shadow economy. Additionally, the observed trend suggests a possible relationship between the level of scientific research and the prevalence of the shadow economy in various EU countries. This pattern indicates that scientific inquiry and research into economic issues, such as the shadow economy, are crucial tools in developing effective strategies and policies to mitigate its impact.

A distinguishing feature of this paper is its examination of European Directives specifically designed to combat and prevent tax evasion. Studying these strategies and directives is essential as they offer a framework for coordinated actions across EU member states to enhance compliance, standardise tax systems, and address emerging challenges in tax evasion prevention.

The theoretical frameworks discussed above collectively inform the empirical modelling approach adopted in this paper. Specifically, the Dual Economy and Growth Theories underpin the analysis of the shadow economy’s contribution to GDP dynamics. At the same time, Institutional and Public Finance theories guide the selection of variables related to governance, taxation, and fiscal capacity. Behavioural Economics complements this by explaining micro-level motivations underlying tax compliance. Together, these perspectives justify the use of structural equation modelling (SEM) and panel regressions to capture both direct and indirect relationships between the shadow economy and economic development.

2.1. The Shadow Economy and Tax Evasion at the EU Level

Understanding the shadow economy and tax evasion within the European Union necessitates a comprehensive review of existing research to identify key trends, definitions, and conceptual distinctions. A vast body of literature exists on research into tax evasion and the shadow economy. To accurately determine the current state of knowledge on this topic and its associated fields, a bibliometric analysis was conducted, considering papers indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection. We relied exclusively on the Web of Science Core Collection, given its rigorous journal selection criteria, high-quality citation indexing, and compatibility with established bibliometric methods implemented in VOSviewer. Using a single, curated database avoids inconsistencies that may arise from merging heterogeneous datasets and ensures full reproducibility of the analysis. The terms employed in the “topic” selection were “shadow economy” or “tax evasion”. The concept of the shadow economy is found in different forms, but the keyword analysis of the scientific literature will retrieve all other associated forms. Subsequently, a definition is recommended to identify possible conceptual differences. Next, as a step in selecting the analysed documents, we applied filters for the document type as “article”, the publication period of the documents (2000–2025), and the language of the paper (English). In addition, a territorial delimitation was imposed, and only documents covering countries that are members of the European Union were included. After applying these filters, a total of 1952 articles were selected in the database for bibliometric analysis. The bibliometric analysis is based exclusively on English-language publications indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection. This approach follows established standards in bibliometric research, as WoS provides rigorously curated, high-quality and internationally comparable data, supported by consistent metadata required for advanced science-mapping techniques. Restricting the dataset to WoS and to the English language ensures that the analysis is based on publications that meet globally recognised scientific visibility and quality thresholds, allowing for robust, reproducible and comparable results.

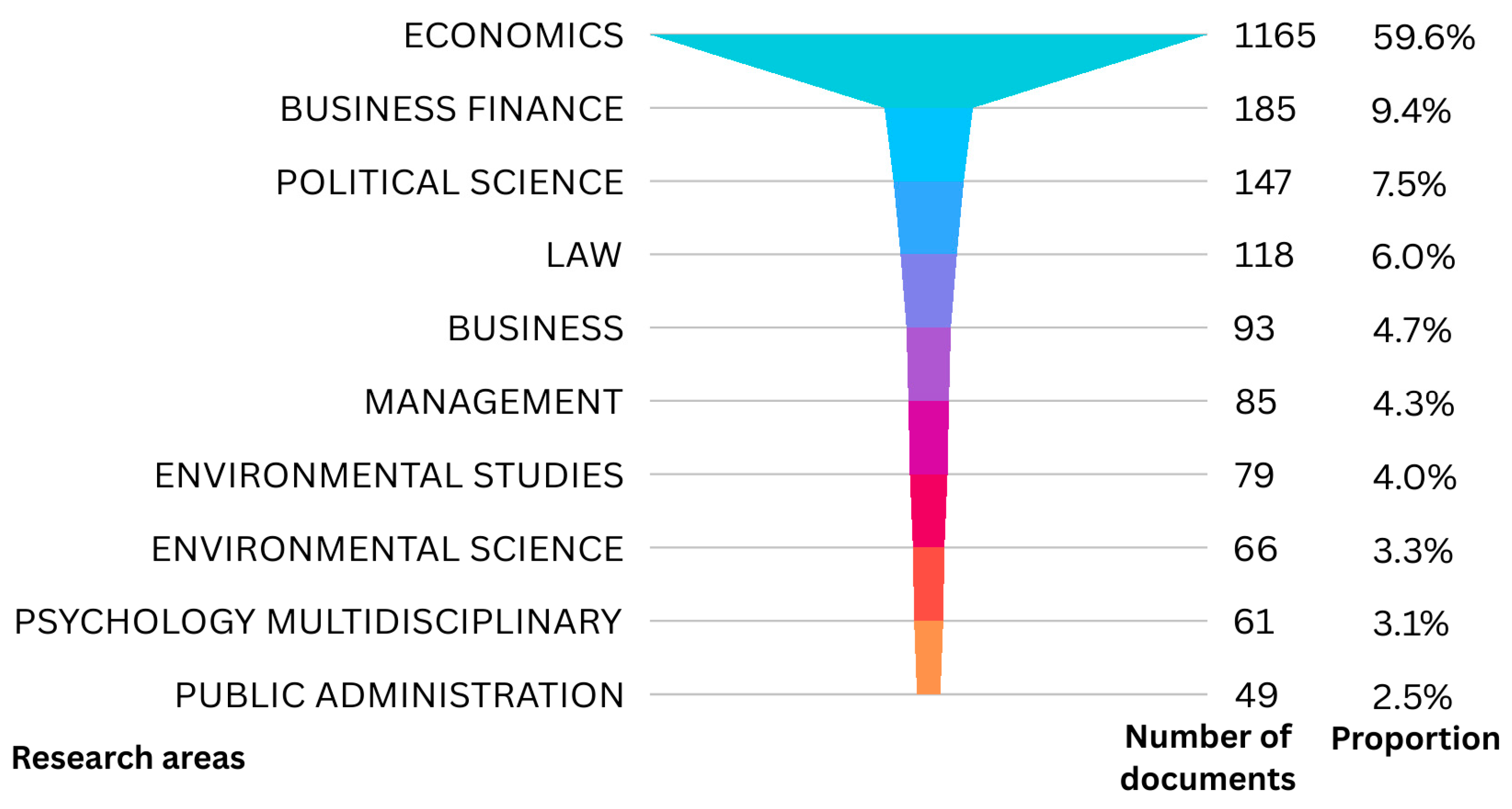

In the first stage, we identified the most important areas in which the selected articles fall. According to the categories established by the Web of Science, ten research areas address tax evasion and the shadow economy; however, the most significant ones are evident in

Figure 1.

According to this categorisation of studies, approximately 70% of the Web of Science-indexed papers related to tax evasion and shadow economy concepts originate from the economics (1165) and business finance (185) fields, indicating that these are the primary research areas for our topic of interest. Considering that the regulation and control of economic activities fall under the responsibility of tax administrations, it was expected that the economics-related regions would have a higher share in the total number of studies on this topic. The finding reinforces the central role of economic theories and business practices in understanding and addressing issues related to tax evasion and the underground or shadow economy by analysing how individual and collective economic behaviours influence illegal or unrecorded economic activities. Research focused on economic theories, such as those related to tax incentives, consumer and firm behaviour, and the cost–benefit analysis of tax evasion, is of interest because it provides a fundamental understanding of the motivations underlying tax evasion. Authors can better explain why tax avoidance occurs and the conditions that encourage such behaviour by exploring how individuals and firms respond to various tax incentives. Additionally, business practices, including tax planning strategies, corporate structures, and tax risk management, play a crucial role in shaping the environment that fosters tax evasion and the underground economy. Understanding these practices allows researchers to identify how economic actors exploit regulatory loopholes or opportunities to minimise tax obligations. By integrating economic theories with business practices, the authors aim to propose more effective solutions to combat tax evasion through informed adjustments to tax policies, regulations and control mechanisms, which can ultimately foster a more compliant and transparent economic system.

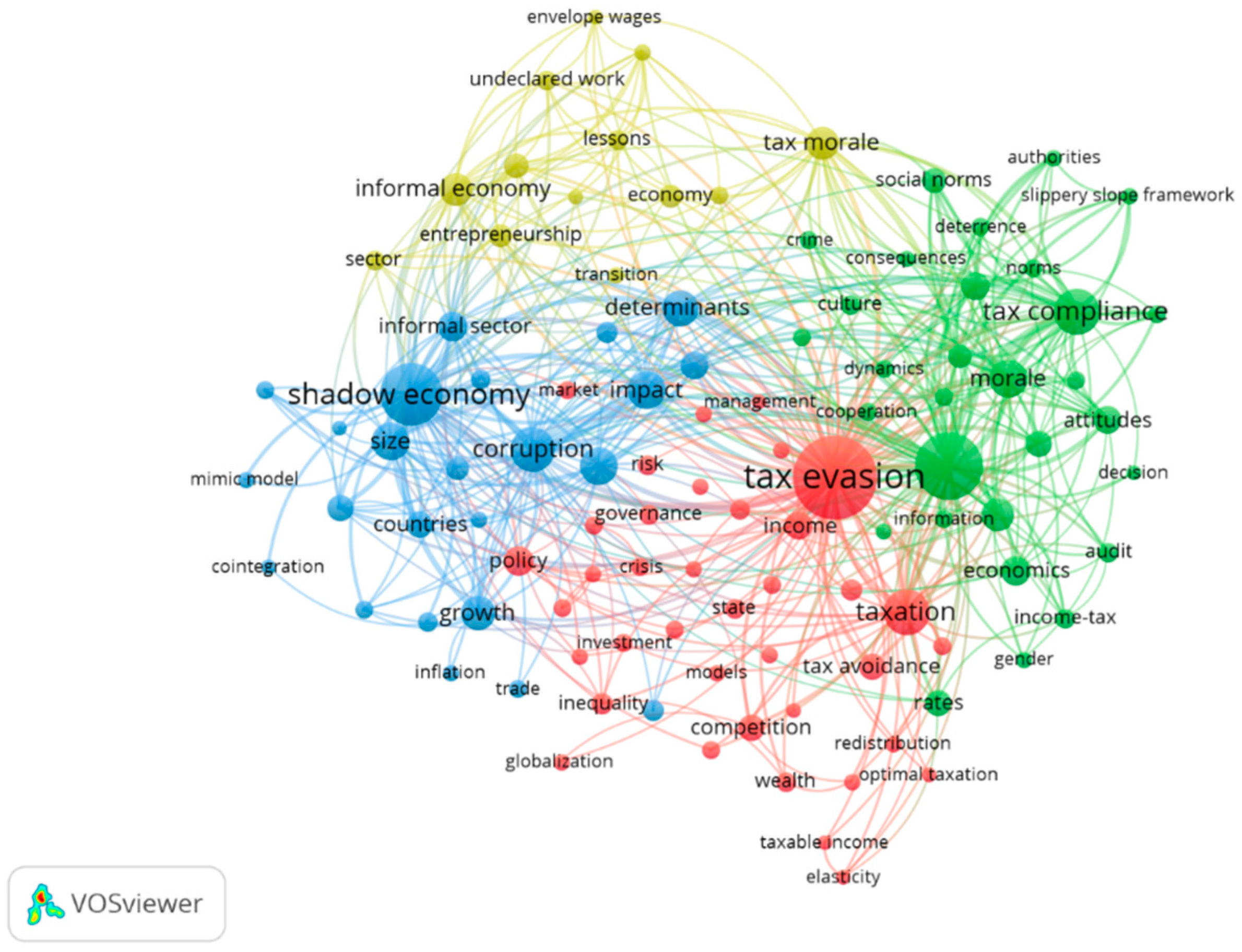

In the next step, we uploaded the results to the Web of Science platform using the VOSviewer software. The keyword co-occurrence analysis is the most important bibliometric analysis for further study of the issue of tax evasion and the shadow economy. This importance emerges from identifying all terms used in the English language for tax evasion and the shadow economy, as well as from identifying concepts associated with this research topic. A total of 6162 keywords were distinguished in all documents, and 105 of these exceeded the selected minimum threshold of 20 occurrences. In

Figure 2, the keywords are organised into four clusters, highlighted by distinct colors.

Table 1 provides additional insights, building on the figure above, to evaluate the key interconnections within the current research framework on tax evasion and the shadow economy. The red cluster, consisting of 38 terms, outlines the classical concepts through which the government (“government”, “state”, “governance”) and other state institutions manage and deal in an efficient way (“performance”, “growth”) with different measures (“policy”, “redistribution”, “investment”), the problems (“crisis”, “globalization”, “inequality”, “risk”) that may lead to tax avoidance (“avoidance”, “shadow banking”, “tax avoidance”, “tax evasion”, “tax havens”). In this cluster, we have identified the term “tax avoidance”, which in the specialised literature has a different meaning from “tax evasion, highlighting the importance of nuanced definitions when analysing these economic phenomena. The importance of identifying and clarifying the terminology associated with tax evasion and the shadow economy lies in ensuring precise and consistent definitions, which are essential for accurate data measurement, effective policy design, and reliable cross-country comparisons. To eliminate the risk of mistranslation and misinterpretation, we will identify the definitions of all terms that form the lexical family specific to the research topic in the next step (

Table 2).

The green cluster comprises 30 keywords that form the specific framework of another research trend on tax evasion, namely the analysis of the implications of cultural and behavioural factors (“attitudes”, “behaviour”, “culture”, “gender”, “morals”, “social norms”, “trust”) on the extent of tax evasion. It suggests that tax compliance within a country is shaped by cultural norms, education levels, and the extent of corruption, with factors such as attitudes, social trust, and moral values playing a key role in determining the degree of tax evasion. This is important because understanding the cultural and behavioural factors that influence tax evasion allows policymakers to design more effective, context-specific strategies to improve tax compliance. By addressing specific social norms, such as education and corruption, governments can foster a more cooperative relationship between taxpayers and authorities, leading to a more efficient tax system and a reduction in the incidence of tax evasion.

The 24 keywords in the blue cluster reveal another research trend, related to the size of undeclared work (“unemployment”, “informal sector”, “size”) and the shadow economy, with strong empirical evidence presented in the scientific literature (“mimic model”, “model”, “panel-data”, “cointegration”, “determinants”). It is noteworthy that terms such as “hidden economy”, “shadow economy”, “informal sector”, and “shadow economy” often appear together in the literature, indicating that there is a substitution of these terms. Clarifying these distinctions is crucial for developing more accurate models and policies to address the complexities of undeclared work, tax evasion, and economic informality. Understanding the nuances between these terms enables more targeted interventions and improves the measurement of their impact on economic development, labour markets, and government policies.

The co-occurrence analysis indicates that the yellow cluster, composed of 13 keywords, highlights a focus on how the shadow economy influences entrepreneurial activity within a country, referring to concepts such as “informal economy”, “undeclared work”, “envelope wages”, or “tax morale”. This cluster suggests that the informal or hidden economy may have significant effects on entrepreneurship, such as creating opportunities for unregulated businesses or influencing the behaviour of entrepreneurs who may rely on informal markets to avoid taxes or regulations. Analysing this relationship is essential for understanding how the shadow economy interacts with formal entrepreneurial ecosystems, potentially shaping innovation, competition, and overall economic growth.

Table 2 lists the definitions of the terms identified as part of the research scope of tax evasion and the shadow economy, as per the relevant literature or tax laws, to eliminate the risk of mistranslation or misuse. Although the terms associated with the two phenomena are sometimes used synonymously in some research [

9], there are distinct differences between them. As shown in the table, there are differences between tax evasion and tax fraud, as well as between the shadow, underground, informal, grey or unobserved economy. While there is an obvious demarcation between evasion and fraud, i.e., evasion is the method of breaking the law. In contrast, fraud is the actual action by which the law is broken, there is no clear distinction between the other terms. This result highlights a correlation between the scientific productivity of EU countries and the level of the shadow economy.

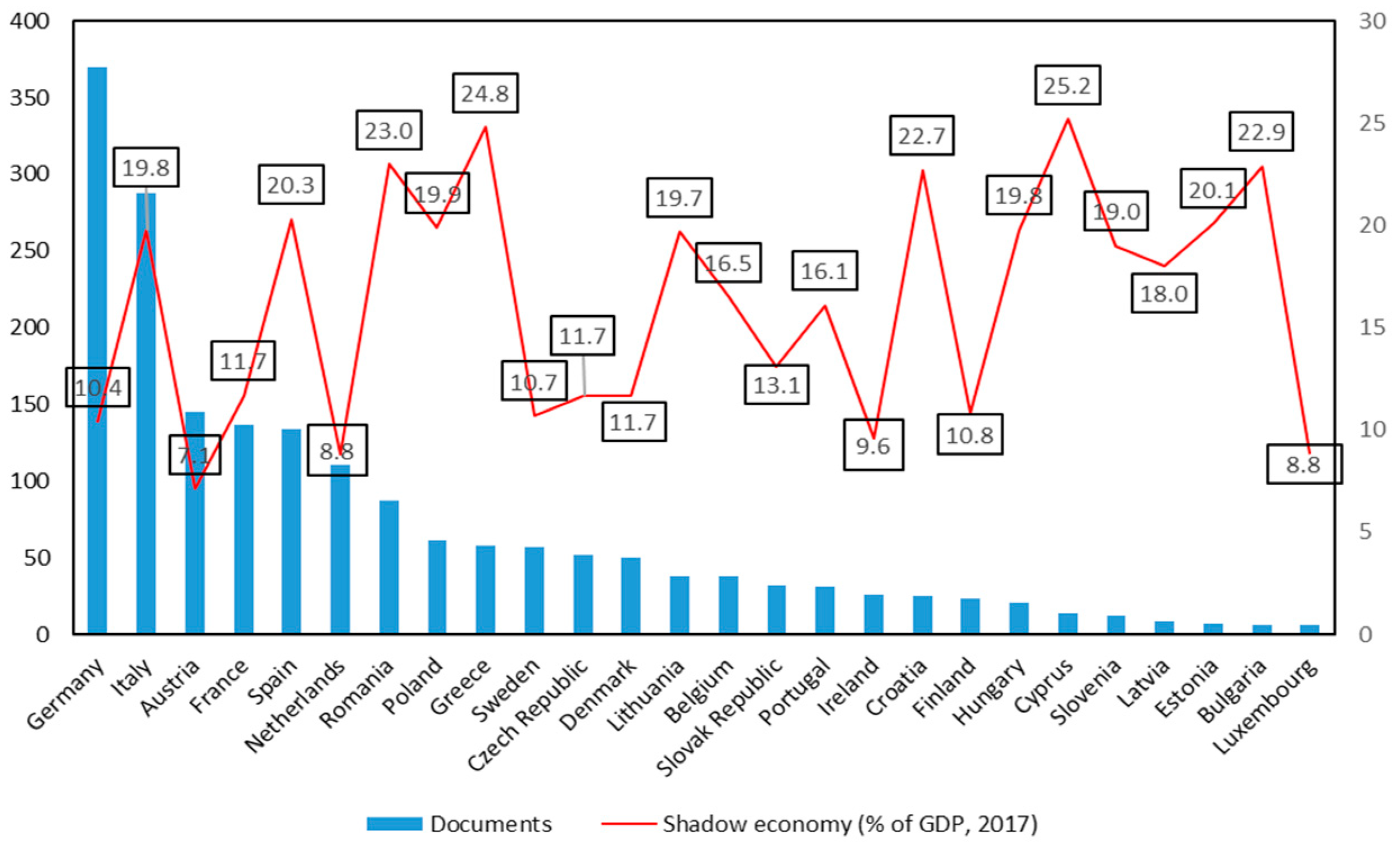

Figure 3 plots the number of papers and the level of the shadow economy in 2017 as a share of gross domestic product. This information is based on research by Medina and Schneider [

1].

Figure 3 reveals the following trend: as the number of published papers decreases, the size of the shadow economy tends to increase relative to the gross domestic product (GDP). This suggests that countries with lower research output on the topic may be less engaged in studying and addressing the shadow economy, possibly leading to a lack of policy focus or inadequate measures to combat its growth. This suggests that countries with lower research output on the topic may be less engaged in studying and addressing the shadow economy, possibly leading to a lack of policy focus or inadequate measures to combat its growth. Additionally, the data reveal that countries with higher levels of the shadow economy are predominantly located in the Balkan region, including Cyprus (25.2%), Greece (24.8%), Romania (23%), and Bulgaria (22.9%). Conversely, countries with lower shadow economy levels include Germany (10.4%), Ireland (9.6%), the Netherlands (8.8%), Luxembourg (8.8%) and Austria (7.1%). This pattern may indicate that countries with greater research efforts and attention to the issue have more effective strategies for reducing the size of the shadow economy.

Our bibliometric analysis continues with the network of collaborations between countries through co-authorship, considering a minimum of 10 papers per country and a minimum of 100 citations per country. Based on worldwide publications, out of 98 countries, 38 met the threshold. Regarding the scientific productivity of EU countries, as measured by articles indexed in the Web of Science, published in English from 2000 onwards, Germany leads with 449 papers, followed by Italy with 377 papers, Austria with 179 papers, and France with 175 papers. At the other end of the spectrum are the Baltic countries, with 10–14 published papers. The graphical representation of the worldwide networks of co-authorship, based on countries, is captured in

Figure 4, which highlights four clusters. This research is important because it highlights the collaborative efforts between countries through co-authorship, emphasising the global nature of the issue and the need for international cooperation in understanding and addressing tax evasion and the shadow economy. The red and green clusters are more numerous, with 11 countries, while the other two clusters each consist of 8 countries.

The red cluster indicates a very close collaboration between the northern countries (Scandinavian and Baltic countries) and Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Authors from Sweden and Denmark have the highest number of papers published on the topic of tax evasion and shadow economy (73 documents and 66 documents, respectively). Southeastern and Central European countries (e.g., Romania, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary), along with England, Turkey, and Ukraine, are countries that consistently address the subject of tax evasion and the shadow economy in their published articles, being included in the green cluster. This cluster has the highest concentration of publications, which is why the level of co-authorship between the countries is also very high. From this cluster, Romania is represented by researchers who have published a high number of articles (136), second only to England (216 papers).

The blue cluster demonstrates strong collaboration among Southern European countries, Brazil, Chile, and Canada. According to the results of the cross-country scientific co-authorship analysis, we can state that for this cluster, Italy, France, and Spain are most concerned about the shadow economy and tax evasion, with 377, 175, and 168 published papers, respectively, on these topics. The yellow cluster indicates a collaboration among the most developed EU countries (Belgium, Germany, Austria, and The Netherlands), as well as with many other EU countries, the USA, China, India, and Pakistan. Germany has the highest number of published papers from all the 38 countries included in this co-authorship figure, with 449 documents, followed by the USA, with 212 documents.

Following the bibliometric analysis results of the state of knowledge regarding the phenomenon of tax evasion and shadow economy, there is a high level of interest in addressing this issue in scientific research. However, the conceptual delimitation of the terms used for economic activities outside the legal sphere has not yet been achieved. In countries heavily involved in research, the level of understanding of the phenomena is low, which is most likely due to the limited application of the findings. Furthermore, the analysis results show that social and cultural factors may influence research interests and the spread of evasion.

Further on, scientific literature identifies other determinants of the shadow economy and tax evasion. Schneider et al. [

16] conclude that the main drivers of taxpayers’ decision to fall into the shadow economy are (i) the burden of taxes and social security contributions, (ii) the intensity of regulation, (iii) the quality and quantity of public services, and (iv) the state of the official (formal) economy. The research by Ohnsorge and Yu [

18] identifies a lack of development and poor governance as the primary reasons leading to the growth of the informal economy. Lack of development refers to a state’s inability to absorb rural migrants in developed urban areas, find sources of finance for the growth of the formal economy, and train sufficient human capital to meet current labour market demands. In addition, the degree of regulation of the labour force is the main determinant of the informal dimension of the labour market. When a state’s tax policy imposes a high percentage of taxes and contributions on labour income, employees decide to work less to enjoy leisure time or work illegally to avoid the tax burden. In concrete terms, a state’s lack of development emphasises its inability to benefit participants in the formal economy, while bad governance exacerbates the costs of participating in the formal sector.

Individual and corporate taxpayers are incentivised to engage in activities in the shadow economy from a cost–benefit perspective and to avoid state-imposed over-taxation of the activity undertaken and the revenue earned [

19]. Additionally, the state of the economy significantly influences the decision to comply and bring actions into legality. For example, higher inflation rates will induce a significant proportion of taxpayers to resort to tax avoidance methods and earn higher income from doing business. However, if higher inflation rates are triggered by periods of severe crisis, those who choose not to comply are at high risk. Individual labour market taxpayers in the informal sector do not benefit from the services provided by their social security contributions. A health crisis such as the one generated by COVID-19 deprives them of the health services offered in the mainstream system. As far as corporate taxpayers are concerned, crises bring an additional degree of uncertainty to their activities, and the increased frequency of controls carried out by state institutions may generate additional costs for them in the form of fines and penalties.

The literature has identified a significant influence of the central bank on the size of the shadow or grey economy. The results of Berdiev and Saunoris [

20] show that central bank independence is crucial in unregulated economic activities. Dimensions of independence, such as those related to the central bank’s managing director and the formation of monetary or credit policy, show that the lack of political influence on the central financial sector’s functioning significantly decreases the potential of the shadow economy.

The size of the shadow economy, on average worldwide, stands at 31% of gross domestic product (GDP), while the average in the European Union is 17.1% of GDP [

1]. Among the activities included in the shadow economy are illegal activities (e.g., smuggling), do-it-yourself (DIY) activities, and even helping neighbours. The need to understand the extent of tax evasion has prompted the relevant EU institutions to develop indicators and issue directives to monitor and regulate the phenomenon. Researchers’ efforts in this area have also made significant contributions to identifying the most appropriate policies. Schneider et al. [

16] classify indicators specific to the shadow economy into financial indicators, labour market indicators and the state of the formal economy. Given that the proceeds of illegal activities are in the form of fiat money, financial indicators signal the existence of surplus cash use.

2.2. European Strategies for Preventing and Combating Tax Evasion

This subsection aims to critically analyse the evolution of strategies and directives developed and adopted within the European Union to reduce and combat forms of tax evasion and the shadow economy. Specifically, this part of the paper does not aim to be descriptive, but rather analytical, in identifying the policies and instruments used by Member States to reduce the phenomenon of evasion, while highlighting the most essential characteristics. The elaboration of this subsection is based on a content analysis of European Union policies and initiatives aimed at combating tax evasion and promoting a fair economic environment. The initiatives and policies developed within the EU between 1997 and 2025, with the primary purpose of combating tax evasion and ensuring tax equity, were included in the analysis. The documents can be grouped into stages that reflect the involvement of the states in this phenomenon, namely (i) establishing the basis for cooperation, (ii) developing cooperation, (iii) digitalisation and (iv) developing sustainable policies in accordance with the targets of reducing the shadow economy and tax evasion.

Effectively addressing tax evasion within the European Union requires a coordinated approach, guided by regulatory frameworks and strategic initiatives that aim to enhance tax compliance and financial transparency. Tax evasion poses a significant challenge to budget revenue collection. In response, the European Union has introduced a series of initiatives aimed at enhancing compliance rates. These measures, which are underpinned by a commitment to fairness, seek to standardise tax systems and leverage digital technologies to improve tax traceability. The EU’s tax agenda has evolved, enriched with foundational measures in the 1990s and progressively advanced with more robust frameworks and directives.

Figure 5 illustrates the historical evolution of the leading European Union`s initiatives, plans, directives and literature models for improving compliance and ensuring fair taxation.

The European Union, as a key player in the fight against tax evasion, laid the groundwork with the Code of Conduct (Business Taxation) in 1997 [

22]. This initiative set out principles to curb harmful tax competition and enhance transparency across member states. Building on this foundation, the early 2000s saw the introduction of targeted directives such as the Council Directive on Taxation of Savings Income in the Form of Interest Payments [

23]. This directive aimed to reduce existing distortions in the effective taxation of savings income in interest payments. By 2008, the European Economic Recovery Plan was introduced in response to the economic challenges of the global financial crisis. This plan focused on broader recovery efforts and integrated tax fraud mitigation into its strategies [

24].

Building on the initial frameworks, the EU entered a phase of intensified efforts starting in 2012 [

25]. The Action Plan to Strengthen the Fight Against Tax Fraud and Tax Evasion marked a turning point [

26], introducing comprehensive measures to improve tax compliance. Successive directives, such as the Directive on Administrative Cooperation (DAC 1—2013) [

25], Directive on Administrative Cooperation (DAC 2—2014) [

27], Anti-Money Laundering Directive (DCSB4—2015) [

28], and the Anti-Money Laundering Directive (DCSB5—2018) [

29], tackled complex issues like tax planning and profit shifting. The Anti-Money Laundering Directives (DCSB4—2015 and DCSB5—2018) regulated how electronic money transactions are conducted and tracked. These Directives are addressed to credit institutions, financial institutions and natural or legal persons engaged in certain professional activities. These institutions or individuals must identify the risks associated with particular transactions and take all necessary steps to prevent money laundering. To achieve this, the directives establish transaction ceilings and specify the types of beneficiaries to be treated with caution. The same directives lay down a series of reporting obligations applicable to the above-mentioned institutions and individuals, as well as a series of sanctions in the event of non-compliance.

The Anti-Avoidance Directive [

30], introduced in 2016, aims to tackle tax avoidance across the EU, ensuring that tax is paid in the country where the profit or value is realised and creating a fair and coordinated tax system throughout the European Union, thereby establishing a level playing field for internal markets. The first measure regulated under this Directive refers to the limitation of the deductibility of interest to 30% of the taxpayer’s earnings before the Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation (EBITDA). However, a maximum threshold of three million euros for deducting the excess cost of goodwill has been set at the group level, while also specifying the exceptions to its application. The most critical measure in the document’s text regulates the profits made by controlled foreign companies, which, together with the general anti-abuse rule, aims to eliminate tax avoidance cases by transferring assets or profits between group companies in other Member States. During this period, the EU also began addressing the digital economy with initiatives such as the Council Directive on the Common System of a Digital Services Tax on Revenues Resulting from the Provision of Certain Digital Services (2018) [

31]. Accordingly, large multinational tech firms operating within the EU were offered modern taxation solutions, indicating ongoing efforts to ensure that digital businesses pay their fair share of taxes in line with the economic value they generate.

The 2020s revealed an EU committed to adapting its tax policies to the dual challenges of digitalisation and sustainability. The EU Action Plan for Fair and Simple Taxation, Supporting the Recovery Strategy [

32], prioritised modernising tax systems to address the challenges of digitalisation, globalisation, and the growing need for sustainable development. Directives such as DAC 7 [

33] and DAC 8 [

34] enhanced transparency for digital platforms. The Directive on Administrative Cooperation in the field of taxation—DAC8 [

34] has had three key objectives: to eliminate the risk of tax fraud, tax evasion and tax avoidance arising from the evolution of digitisation and alternative means of payment and investment. Thus, this Directive aimed to (i) bring crypto-asset service providers within the scope of the application of automatic exchange of information by extending administrative cooperation to tackle the challenges in this area, (ii) bring relevant tax information on high net worth individuals and dividend income within the scope of automatic exchange of information and (iii) improve the reporting of taxpayers’ tax identification number (TIN) to identify and assess the taxes due correctly. At the same time, proposals like VAT in the Digital Age (proposal—2022) [

35] and BEFIT (proposal—2023) [

36] signalled the EU’s commitment to fostering a green and growth-friendly tax environment. The Tax Package for Fair and Simple Taxation [

32] was developed in response to the harmful effects of the pandemic crisis and the rapid evolution and adoption of digital technologies in the economy. The proposals outlined in this tax package included 12 recommendations aimed at improving various aspects of the tax system. To simplify the system and reduce compliance costs, it has been proposed that a single VAT registration number be established for each taxpayer and that the taxation of newly established European Companies (SEs) and Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) be simplified. Therefore, a harmonised tax identification and regulatory framework at the EU level is the basis for reducing compliance costs arising from the high complexity of the system. Increasing certainty for taxpayers and tax administrations will be ensured by improving the dispute resolution mechanism for multi-state tax residence claims, extending the automatic exchange of information covered by the DAC Directive 8 and identifying how tax incentives can be granted at the EU level without affecting the functioning of the Single Market. To address the tax revenue shortfall within the Union, proposals include the immediate regulation of e-invoicing, the relaunch of the VAT definitive regime initiative, the standardisation of a unified corporate tax return, and the establishment of a specialised institution (Tax Observatory) to monitor tax developments at the Union level. For the area of coordinated corporate tax regulation, it is proposed to address the issue of debt financing through the Directive against tax avoidance and to develop a unified framework for tax regulation, as outlined in the Directive on company taxation for the 21st century [

37]. The final proposal in this tax package aimed to assess the effectiveness of tax administration, the exchange of tax information, and data quality. This proposal was implemented through the improvement and subsequent implementation of EUROFISC 2.0, which is designed to store and process all tax data and information, thereby becoming the single tax information clearinghouse within the European Union. The Directive on Business Income Taxation in the European Union (BEFIT) [

36] aimed to establish a common business tax framework across the EU, providing a clear and simplified taxation system for businesses operating within the EU.

As the EU moves forward, its focus remains on harmonising tax policies and leveraging digital technologies to enhance compliance and traceability. Plans, including ongoing discussions on green taxation measures and the implementation of digital tools, reflect the Union’s commitment to building a resilient and equitable tax system for all member states. Although progress is significant at the European Union level, the effectiveness of some member states has been hindered by poor policy implementation or inefficient tax administration, resulting in consistent differences compared to the EU average. Moreover, although the digitalisation of tax reporting, implemented through DAC 7–8, has brought significant results in transparency, it has also generated additional compliance costs, especially for small and medium-sized companies, which may favour the entry of some activities into the shadow economy.

In the assessment of the impact of the administrative cooperation directives on the subject of direct taxation, positive results appear after implementation. Thus, the measures to introduce standardised forms and the use of data interconnection networks for the exchange of information have generated efficiency gains. Moreover, the volume of information exchanged has increased after the implementation of the directives [

38].

The European Commission report reveals that some states have recorded additional net collections exceeding the costs of implementing the directives, generating added value through their use. However, there is also information related to a low efficiency of the directives related to voluntary declarations and controls [

39].

The elusive nature of the shadow economy complicates the accurate measurement of economic growth, underscoring the need for robust methodologies and comprehensive frameworks. The most influential work in calculating the size of the shadow economy is Medina and Schneider’s [

1] “Shedding Light on the Shadow Economy: A Global Database and the Interaction with the Official One”. The research employed the Multiple Indicators-Multiple Causes (MIMIC) approach on a sample of 157 countries, estimating the size of the shadow economy from 1991 to 2017. The most relevant results and the database that can be used in future studies highlight that the shadow economy decreased by only 6.8% as a global average over the period analysed, raising critical questions about the effectiveness of coordinated efforts to combat illegal economic activities.

While models for measuring the shadow economy offer valuable insights, their accuracy often hinges on the chosen methodology. For example, the money demand model is susceptible to selecting regressors: the choice of regressors can have a material and very country-specific impact on the estimated level of the shadow economy, as each country has a degree of uncertainty that needs to be treated independently. It can be reduced by combining models such as the money demand, frequentist, and Bayesian models [

21]. Many studies account for estimation uncertainty, comparing the results obtained by researchers with those reported by agencies and institutions, as well as the different approaches, i.e., direct or indirect calculation methods.

Further complexities arise from methodological differences in defining and measuring the shadow economy. The issue of not including indicators specific to certain areas of activity that may generate “shadow” effects, such as e-commerce or electronic transactions, has recently gained considerable momentum due to the digital transformation phenomenon [

40]. Moreover, these differences in the inclusion of indicators can be attributed to the incorrect use of terms defining the unobserved economy.

Beyond measurement, numerous studies have explored the interplay between the shadow economy and economic growth. Research by Baklouti and Boujelbene [

41] demonstrates the bidirectional relationship between these two phenomena while identifying a unidirectional link between inflation and the shadow economy. Conversely, Luong et al. [

42] emphasise the impact of economic growth and the quality of the rule of law in curbing shadow economic activities. Their findings also reveal a positive correlation between inflation and the expansion of the shadow economy.

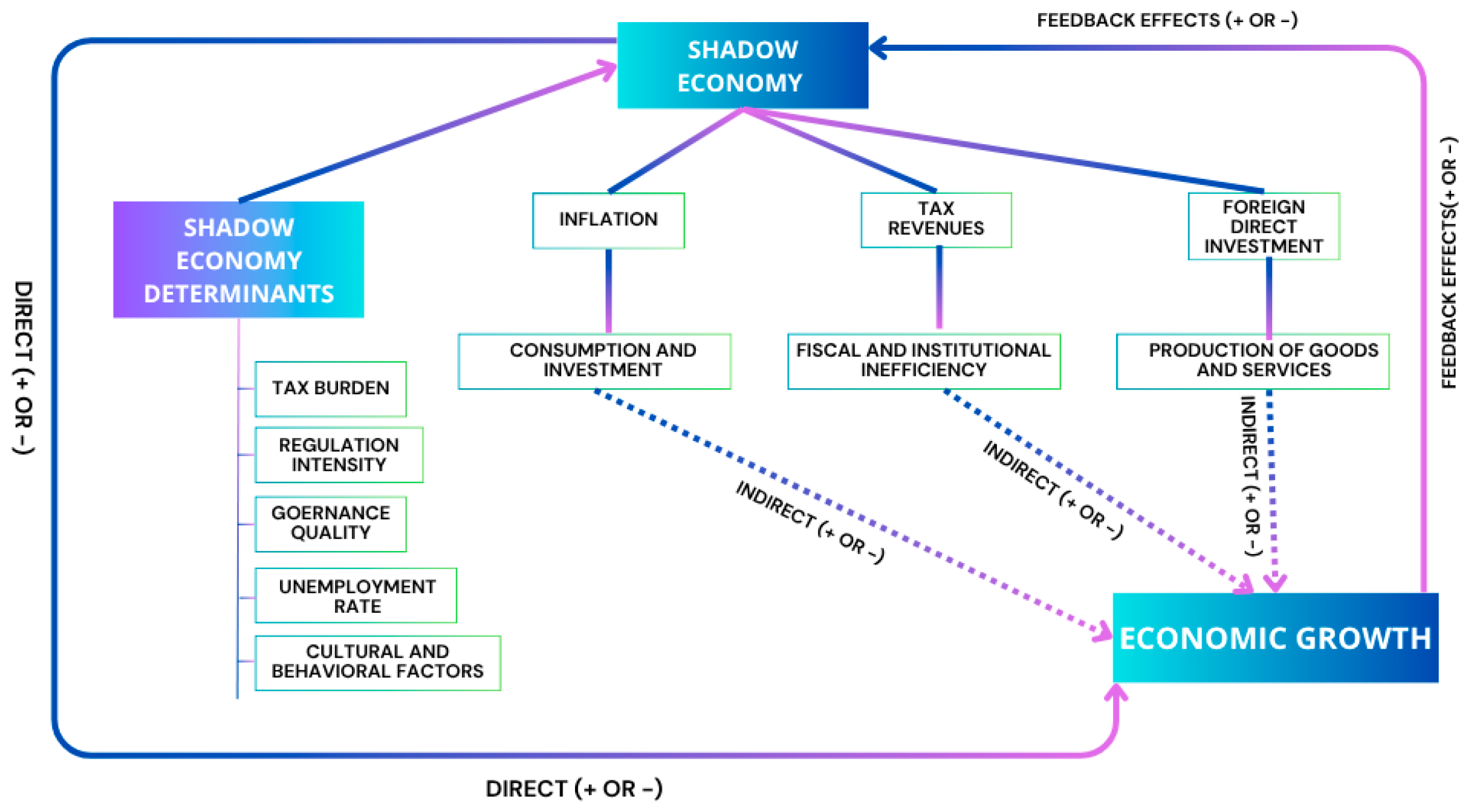

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between the shadow economy and economic growth. First, the size of the shadow economy is determined by its determinants, namely the tax burden in a country, the intensity of regulation, the quality of governance of those in power, the unemployment rate, and cultural and behavioural factors. Second, the shadow economy can have direct effects on economic growth (positive or negative), but it can also exert its influence indirectly through the impact on inflation, tax revenues, or even foreign direct investment. Finally, certain levels of economic growth can generate feedback effects on the shadow economy. Generally, a prosperous economy contributes to a reduction in shadow economy activities.

3. Methodology and Data

The primary objective of this research is to examine the relationship between the shadow economy and economic growth in the European Union, taking into account mediating factors such as tax revenues, inflation, and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) over the 2000–2022 period. To meet the study’s objective, we conducted a quantitative empirical analysis using panel data with cross-country coverage. Our approach took into account the four research questions, and to formulate answers, it was necessary to identify the appropriate mix of analyses for our subject. Thus, by consulting previous studies, we selected structural equation modelling (SEM) to determine the level of mediation of macroeconomic variables on the relationship between the shadow economy and economic growth. To capture the impact of the shadow economy on economic growth across the European Union from 2000 to 2022 and to identify significant differences between countries, we employed panel least squares regression (PLS), the fixed effects (FE) model, and the random effects (RE) model. In addition, descriptive data analysis, correlation analysis and evolution analysis of variables through the data mapping method completed the mix. Both structural equation modelling and panel least squares analysis enable the construction of complex models using data structured by the country-year unit of analysis, which is why they were selected as the primary methods of analysis in our study. Additionally, fixed and random effects models enable the examination of heterogeneity across countries. The steps within the empirical section of the study were conducted in the following order, as illustrated in

Figure 7.

The Panel Least Squares method is suitable for analysing the relationship between a dependent variable and other independent variables, allowing for the introduction of control variables into the model [

43]. The general model equation for our analysis had the following form:

where

LGDP—dependent variable

c—constant

β—the calculated coefficient of the variable

DIE, DSE—independent variables

DTR, FDI, DI—control variables

ε—standard error of the model

i—country or cross-section (specific to the 27-EU countries)

t—years specific to the period analysed (2000–2022)

The fixed effects analysis model assumes a difference between countries, but the model constant can adjust this [

44]. This difference may be due to cultural, policy or other macro differences. For this model, the estimation is performed through the second equation:

As for the random-effects regression model, it assumes that differences across countries and time can be intercorrelated and are captured in terms of error by a country-specific variable. The standard model equation is given below:

where

ui is the country-specific error term.

Next, the data were processed using Stata software-version 18.5 to construct the structural equation model. The estimation used in this model utilises the maximum likelihood estimation (ML) method to determine the model parameter values [

45]. These values are found such that the probability that the process described by the model produces the observed data is maximised.

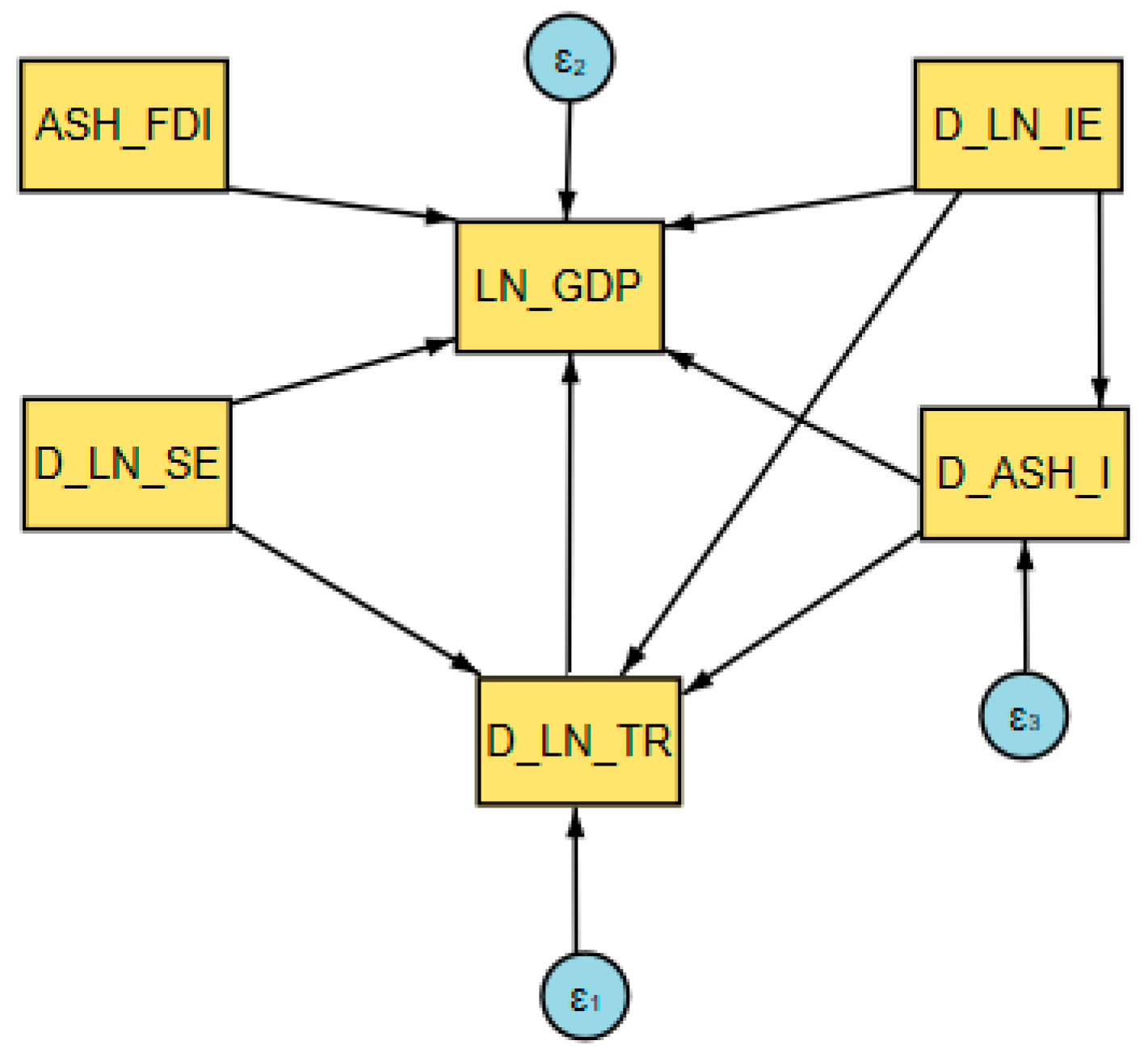

Figure 8 illustrates the model diagram.

The equations tested within the SEM model are shown below:

Equation (4) captures the effect of the shadow economy, informal economy, and inflation on the level of fiscal revenues. The form of this equation is based on previous studies that have demonstrated that there is a direct channel through which inflation influences tax revenues [

46,

47,

48]. Subsequently, Equation (6) captures the impact of fiscal revenues, as well as the direct influence of inflation, the shadow economy, foreign direct investment, and the informal economy on economic growth. Finally, Equation (6) measures the impact of the informal economy on inflation. This structure of the equations was obtained following the model fit tests by calculating modification indices.

The data used in the analysis have an annual frequency, being collected for the period 2000–2022 for the 27 EU Member States. In this study, we distinguish between the shadow economy (SE) and the informal economy (IE), as they capture different facets of non-observed economic activity. The shadow economy reflects deliberate concealment of economic activities from official authorities for monetary, regulatory, or institutional reasons [

49], whereas the informal economy encompasses activities insufficiently covered by institutional or legal frameworks, estimated using the Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) approach [

50]. Both variables are expressed as a percentage of GDP to ensure comparability across EU countries. This operationalization allows the model to capture their distinct effects on economic growth, ensuring consistency between theoretical definitions and empirical measurement. A detailed description, including definition, abbreviation, unit of measurement, and data source, can be found in

Table 3.

These variables were selected based on the research of Nguyen and Luong [

42]. Data were collected in a panel form and underwent an initial statistical analysis stage to be further processed and subsequently included in the econometric analysis.

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used. Significant differences exist between the recorded values of all variables, indicating that these differences are also evident between EU member countries. Therefore, we cannot treat all countries equally due to their policy measures, an aspect also emphasised by Dybka et al. [

21].

The evolution over time of the informal economy, shadow economy and economic growth by country is illustrated in

Figure 9. At the beginning of the common analysis period, i.e., in 2003, the lowest levels of informal and shadow economies were recorded in Austria, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Since theoretical differences were considered when calculating the two variables, they also have value differences. Additionally, this year, the highest values of the informal or shadow economy were recorded in Lithuania, Romania, Croatia, and Bulgaria. In 2020, EU countries largely maintained their positions in the ranking. The countries with the lowest shadow and informal economy were maintained for 2020—Austria, Luxembourg and the Netherlands—but the countries with the highest levels of shadow economies were Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania (29.3–32.9% of GDP, from 32.3 to 35.9% of GDP in 2003) and the countries with the highest levels of informal economies were Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia and Greece (30.19–32.73% of GDP), compared to Bulgaria, Romania, Lithuania, and Croatia in 2003 (when the informal economy was 31.76–36.09% of GDP). After also considering the bibliometric analysis, we conclude that there is limited research interest in this subject, given the evolution and magnitude of the phenomenon.

The gross domestic product per capita (GDP per capita) in 2003 ranks Bulgaria and Romania at the bottom of the EU-27 ranking, with approximately 2700 euros per capita, followed by Latvia with 4914 euros per capita, while at the top, we have Luxembourg, with 65,689 euros per capita, followed by Ireland and Denmark, with 41,203 and 40,519 euros, respectively, per capita. In 2020, the least developed countries in terms of GDP per capita remain Bulgaria (10,198 euros per capita) and Romania (13,082 euros per capita), followed in this case by Croatia (14,808 euros per capita), while the highest values are still in Luxembourg (116,905 euros per capita), Ireland (87,567 euros per capita) and Denmark (60,985 euros per capita).

Based on these maps, it can be hypothesised that high levels of informal and shadow economies significantly influence economic growth. This hypothesis will be tested in the following empirical analysis. The average values of the GDP per capita variable increased substantially over the period reviewed, from €21,180.7 in 2003 to €35,643.8 in 2020. Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia have the lowest values, while Luxembourg, Ireland, and Denmark are on the opposite side of the ranking.

The following statistical analysis of the primary data aimed to examine the correlations between the variables, with the results presented in

Table 5.

The correlation indicates the level of association between two variables and the direction of the relationship between them. For both the informal economy and the shadow economy, we identified a strong negative correlation with GDP per capita and a weaker, yet still statistically significant, positive correlation with inflation. Additionally, the correlation levels (IE/SE and GDP, or IE/SE and I) are very similar, considering the Pearson correlation coefficients obtained in both matrices.

We also note the positive correlation between the shadow economy and foreign direct investment. However, with weaker significance, such a correlation was not statistically significant for the informal economy and FDI. The correlation between SE and FDI may be driven by the attractiveness of a country in terms of profit opportunities for foreign investment firms. Moreover, FDI is positively and significantly related to tax revenues. This result contradicts the idea that tax systems with high fiscal pressure would not be attractive for foreign investment. Accordingly, most developed EU countries tend to have higher tax revenues as a percentage of GDP, which is also reflected in the statistically significant positive correlation between tax revenues and GDP. The correlation between GDP and inflation is negative because higher inflation is expected to induce lower GDP per capita.

Recognising the significant differences between countries, we processed the data to ensure the results were relevant to the selected models. Before econometric modelling, we went through the following steps: (i) we declared the panel dataset in Stata; (ii) we analysed the missing values within the variables and checked the data type (positive, negative or mixed); (iii) for the TR, SE and IE variables we normalised the data from percentages to unit values; (iv) we generated new variables, logarithmic, for GDP, TR, SE, IE and we used the hyperbolic arc sine function to generate new variables for FDI and I because they also had negative values; (v) we performed descriptive statistics and later we used the ipolate and epolate functions to treat the missing values in the TR, SE, IE and FDI variables. Finally, we tested the stationarity of the new variables, obtaining the results in

Table 6.

As can be seen from the

p-values of the root tests, the variables LN_TR, LN_SE, LN_IE, and ASH_I do not meet the stationarity conditions. Therefore, we generated new variables by taking the first difference to ensure stationarity, and the subsequent results of the root tests are displayed in

Table 7.

After testing stationarity, we generated a new variable LN_GDP which indicates the economic growth rate through gross domestic product per capita and is calculated as the difference between the logarithm of GDP/capita in year t and the logarithm of GDP/capita in year t − 1. At this point, our dataset can be used in econometric analyses, ensuring the robustness of the results.

4. Results and Discussion

All results obtained under the PLS, FE, and RE models are centralised in

Table 8. The estimates obtained indicate the impact of the informal and shadow economy on economic growth. Estimating the coefficients and calculating the probabilities for PLS confirms the robustness of the model. The sign and magnitude of the coefficients remain consistent in each of the three models, so we can state that the relationships between the variables are robust, and the interpretation of the coefficients is based on the fixed effects model, according to the Hausman test in

Table 9.

To select the most suitable model from the fixed effects and random effects models, we employed the Hausman test, and the results are presented in

Table 9.

As the test indicates, the differences between the estimates are significant, which means that the errors are correlated with the variables and are specific to each country. Thus, we consider the fixed effects model appropriate for interpreting the results. In this model, the informal economy generates a change of 1.0254 in economic growth with a significant negative impact. Also, the shadow economy exerts a negative effect on economic growth, but it is statistically significant only in the FE model. Foreign direct investment has a positive impact on economic growth, statistically significant, but small in size (0.0075). The impact of inflation is statistically relevant and generates a moderate increase in economic growth (0.0254). Regarding tax revenues, according to the results, they are not significant from an econometric perspective. In our analysis, the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) variable was transformed using the hyperbolic inverse sine (asinh) function to address skewness and to accommodate zero or very small values in the cross-country panel dataset. This transformation is preferable to a simple logarithmic transformation, as it preserves all observations while reducing the influence of extreme values. Theoretical expectations suggest that FDI should contribute positively to economic growth and potentially mediate the relationship between the underground economy and growth, and our empirical findings indicate that the coefficient on FDI is consistently statistically significant, but with a small impact (e.g., p = 0.025 in the FE model, with a coefficient of 0.0075).

We continued the analysis with robustness tests (Modified Wald test, Jochmans portmanteau test) for the fixed effects model, and we summarised the results in

Table 10.

We applied the Modified Wald test to test groupwise heteroskedasticity and to check whether the error variance is different between cross-sections. According to the test, the null hypothesis states that the variance is constant between country groups, and the obtained result determines the acceptance of the null hypothesis. Thus, we can say that there is no heteroskedasticity between countries in our model. In the Jochmans portmanteau test, we tested serial autocorrelation in the panel, and the results obtained indicate the acceptance of the null hypothesis. Therefore, we can say that the FE model does not present serial autocorrelation, being well specified.

Next, we resorted to structural equation modelling to analyse in detail the impact of the variables, as well as to determine the type of effects exerted within the relationships. To obtain statistically relevant results, we used the maximum likelihood estimation method with robust clustered standard errors at the level of each country, and the analysis was carried out for the following relationships: (1) tax revenues are influenced by the level of inflation, shadow economy and informal economy, (2) GDP per capita growth rate is influenced by the level of tax revenues, inflation, shadow economy, foreign direct investment and informal economy and (3) inflation is influenced by the level of informal economy.

Table 11 presents the results of the SEM model, including standardised coefficients and values for z and

p. The shadow economy is shown to have a statistically significant adverse impact on tax revenues, while the informal economy cannot be interpreted due to its irrelevance. We also obtained a statistically insignificant result for the impact of inflation on tax revenues, contrary to previous results in the literature [

44,

45,

46].

In the second equation, we observe that tax revenues do not significantly influence economic growth, but in this model, inflation modifies it positively and significantly, even if the effect is small (0.0259). The shadow economy exerts an insignificant negative impact on LN_GDP, but the informal economy has a significant negative effect on economic growth (−1.2069). Additionally, foreign direct investment is significant, but with a reduced magnitude on economic growth. In the third equation, the informal economy does not reach the significance threshold but tends to exert a negative influence on inflation.

The model fit was evaluated using the standardised root mean squared residual (

Table 12), which measures the average difference between the observed and estimated covariates, and the coefficient of determination, which measures the total variance of the dependent variables explained by the model.

According to the results, the model has a good fit and explains approximately 13.2% of the total variance of the endogenous variables. Considering that the data are a cross-country panel, we consider the results of the fit tests to be satisfactory.

Next, an assessment of the direct, indirect and total effects was made by interpreting the results in

Table 13.

The total effects are the sum of the direct impact and the indirect effects. Of these total effects, the statistically significant ones are those exerted by the shadow economy on tax revenue (−0.1593) and the impact of inflation (0.0262), as well as the effects of foreign direct investment (0.0077) and informal economy (−1.2584) on economic growth. However, it is also worth mentioning that part of the shadow economy indirectly transmits its impact on economic growth through the decrease in tax revenues. Our results are in agreement with those obtained by Baklouti and Boujelbene [

41] who showed that in developing countries, inflation and the shadow economy influence each other, generating a greater imbalance on growth especially in times of political instability. Fu et al. [

51] also reached the same conclusion that the shadow economy has a negative impact on growth that can be mitigated by financial inclusion.

Our results suggest that, although the shadow economy is generally understood to negatively affect economic growth, often through inefficiencies, lost tax revenues and distortions of economic activity, the magnitude of this effect cannot be fully measured. According to the results obtained from the econometric analysis, hypothesis 1 was confirmed, indicating a significant relationship between the shadow economy and economic growth at the level of the European Union Member States, with a negative effect on growth. Wu and Schneider highlight the existence of a “U”-shaped relationship between shadow economy-growth, which changes with the change in the level of economic development and which above certain development thresholds does not decrease with economic growth, but propagates further into the economy [

52].

The results obtained reject the second hypothesis (H2), thus demonstrating that the informal economy exerts a negative impact on economic growth, but the difference from the shadow economy is made by statistical significance. First, our results indicate a negative effect of the informal economy on economic growth, which can be understood through several mechanisms despite its lack of formal recognition or regulation: (i) undeclared work in this sector produces goods and services that affect consumption in the formal economy and affect growth; (ii) informal economy often acts as a breeding ground for entrepreneurship, particularly in areas where formal job opportunities are limited; (iii) informal businesses tend to be more flexible and adaptable to market demands compared to formal businesses, as they are not burdened by the same level of regulation, taxation, or bureaucracy; (iv) where unemployment or underemployment is high, the informal economy acts as a vital safety net, providing a livelihood for those who cannot find formal employment, thereby preventing poverty, supporting consumption levels and supporting broader economic demand and (v) informal sectors play a key role in redistributing resources across socio-economic groups, as individuals and households in low-income areas establish informal businesses that generate income, which is often reinvested locally, boosting demand and fostering community growth. Inflation also plays a role in influencing economic growth. High inflation, characteristic of times of crisis, can lead to obstruction in economic activity, resulting in stagnation in development. Still, low and stable inflation levels contribute positively to economic growth, even if the impact is small. Also, inflation and tax revenues (H3) mediate some of the effects that the informal economy produces on growth. In SEM, we identify a significant influence of foreign direct investment, but with a low impact on economic growth.

5. Conclusions

This study provides an in-depth examination of the shadow economy and tax evasion phenomenon, identifying their key implications for economic growth. Its approach, combining theoretical, empirical, and policy-focused analysis, provides a deeper understanding of the dynamic impact of shadow and informal economies on economic growth, offering valuable insights for policymakers in the EU context. An assessment of the theoretical framework was necessary to properly set up the econometric analysis.

The bibliometric analysis performed to address tax evasion and the shadow economy evidenced that most studies on these concepts are concentrated in the fields of economics and business finance. This highlights the central role of economic theories and business practices in understanding tax evasion, as these areas provide insights into the motivations behind tax avoidance and the strategies that facilitate unrecorded economic activities. In addition, 105 keywords related to the selected research topic were identified, forming a total of four research directions: (i) the current research framework on the classical concepts of tax evasion and the shadow economy, highlighting government measures, economic performance, and risks such as globalisation and inequality and the importance of clearly distinguishing between terms like “tax avoidance” and “tax evasion” to ensure consistent definitions for effective policy design, accurate measurement, and reliable comparisons across countries; (ii) a specific research trend framework on tax evasion which examines the implications of cultural and behavioural factors influencing tax evasion, such as attitudes, social norms, and trust; (iii) a research trend on the relationship between undeclared work and the shadow economy, highlighting the frequent substitution of terms like “hidden economy” and “informal sector” in the literature and (iv) a research direction which examines the implications of the shadow economy on the level of entrepreneurial activity within a state, suggesting that informal markets can influence entrepreneurship by creating unregulated opportunities.

Subsequently, definitions were identified for all the terms that form the research scope of tax evasion and the shadow economy, thus distinguishing the differences between shadow, informal, grey and unobserved economies. However, we note that in some papers, all types of economies are treated as substitutes for one another.

Our findings indicate a notable correlation between scientific productivity and the level of the shadow economy in EU countries, suggesting that countries with higher research output on the topic are more likely to implement effective strategies to address and reduce the shadow economy. Conversely, countries with lower research productivity, particularly in the Balkan region, tend to exhibit larger shadow economies, potentially reflecting a lack of focused policy measures or inadequate attention to the issue.

Following the bibliometric analysis of the state of knowledge regarding the phenomenon of tax evasion and the shadow economy, there is a high interest in addressing this issue in scientific research. This research highlights the importance of international collaboration in combating tax evasion and the shadow economy, as evident in the co-authorship network that spans multiple countries. The findings suggest that while Central and Western European countries, such as Germany, Italy, and Austria, demonstrate high levels of collaboration and scientific productivity on this issue, Central and Eastern European countries exhibit lower research output despite experiencing higher levels of tax evasion, indicating regional disparities in both research focus and institutional engagement with these critical economic challenges. However, it has not yet been possible to conceptually delimit the terms used for economic activities outside the legal sphere. In countries that are intensively involved in research, the level of understanding of the phenomena is low, most likely due to the application of the findings. Furthermore, the analysis results show that social and cultural factors may influence research interests and the spread of evasion.

In terms of strategies to prevent and combat tax evasion, we have identified common efforts among Member States to curb the extent of this phenomenon. In this respect, the Directives issued by the European Union through the Council of the European Union were analysed, namely (i) the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive, (ii) the Directive on Administrative Cooperation in the field of Taxation—DAC8, (iii) the Tax Package for Fair and Simple Taxation and (iv) the Directives on Combating Money Laundering (DCSB4 and DCSB5). Following the review of these documents, there was a focus on integrating tax administrations’ IT systems to ensure fast and constant transmission of information, with the digitisation of tax administration processes being the main pillar on which the prevention and combating of tax evasion is based.

Finally, an econometric analysis was conducted to examine the implications of the shadow economy for economic growth, utilising structural equation modelling and PLS regression models with both fixed and random effects. To perform these analyses, we collected data from 2000 to 2022 for all 27 EU member countries. The most relevant results were obtained through structural equation modelling, a complex type of analysis that can identify both direct and indirect effects between variables. Thus, we can state that the informal economy has a significant impact on economic growth. The IE produces negatives effects, while SE impact is statistically irrelevant. The models used in the analysis (PLS, FE, RE, SEM) are essential for a panel data structure. However, we have observed an obvious limitation of the classical models (FE, RE), compared to structural equation modelling. Specifically, through SEM, we have been able to analyse the variables both through the direct effects they can produce and through the mediated effects. In addition, the effective modelling of the equations and testing through goodness-of-fit tests generate statistically relevant models that make economic sense.

The finding from this analysis was that there is no database of estimated levels of the shadow economy. Tax administrations should recognise that an accurate assessment of the level of the shadow economy is crucial in combating informal activity and tax evasion. Comparing the values recorded within the EU over the first two decades of this millennium, the share of the shadow economy in the gross domestic product has not decreased proportionally to the increase in gross domestic product per capita during the same period.

Our findings indicate that the prevalence of the shadow economy is closely linked to regional economic disparities within the European Union. Countries with lower per capita GDP, particularly in Eastern Europe, consistently show higher levels of shadow economic activity, reflecting not only tax evasion incentives but also structural constraints, such as limited formal employment opportunities and erm diversified industrial sectors. This suggests that informal and shadow activities often act as a compensatory mechanism to alleviate regional employment gaps and support livelihoods. Consequently, policy measures targeting the shadow economy should not focus solely on enforcement; they should also address these deep-rooted structural causes by promoting regional development, improving labour market integration, and fostering industrial diversification. By incorporating these considerations, our study provides a more balanced understanding of the shadow economy and ensures that policy recommendations are contextually relevant across different EU regions.