Research on the Configurational Paths of Collaborative Performance in the Innovation Ecosystem from the Perspective of Complex Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Research

2.1. Research on Innovation Ecosystems

2.2. Research on the Influencing Factors of Collaboration from the Perspective of Innovation Ecosystems

2.2.1. Research on the Impact of the Innovation Environment on Innovation Collaboration Performance

- (1)

- Geographical Proximity

- (2)

- Institutional Proximity

2.2.2. Research on the Impact of Innovation Actors on Innovation Collaboration Performance

- (1)

- Technological Proximity

- (2)

- Collaboration Tendency

2.2.3. Research on the Impact of Innovation Networks on Innovation Collaboration Performance

- (1)

- Network Relationship Quantity (NRQ)

- (2)

- Network Relationship Strength (NRS)

2.3. Configuration Method and Its Application Research

| Analytical Perspective | Traditional Statistical Methods | fsQCA |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical premise | Based on the reductionism hypothesis [53] | Grounded in complex systems theory [8] |

| Variable interactions | “Physical phenomena” between variables, following the physics paradigm [53] | “Chemical reactions” of interacting variables [9] |

| Causal complexity | “Net effect” of single factors and simple additivity | “Net effect” of single factors and simple additivity Complex phenomena involving multi-factor interactions, interdependence, and conjunctural causation [44] |

| Causal relationships | Symmetric, linear cause–effect relationships [58] | Asymmetric causality [59] and equifinal paths [11] |

| Analytical foundation | Correlational relationships between variables [54] | Set-theoretic relationships [9] |

3. Methods

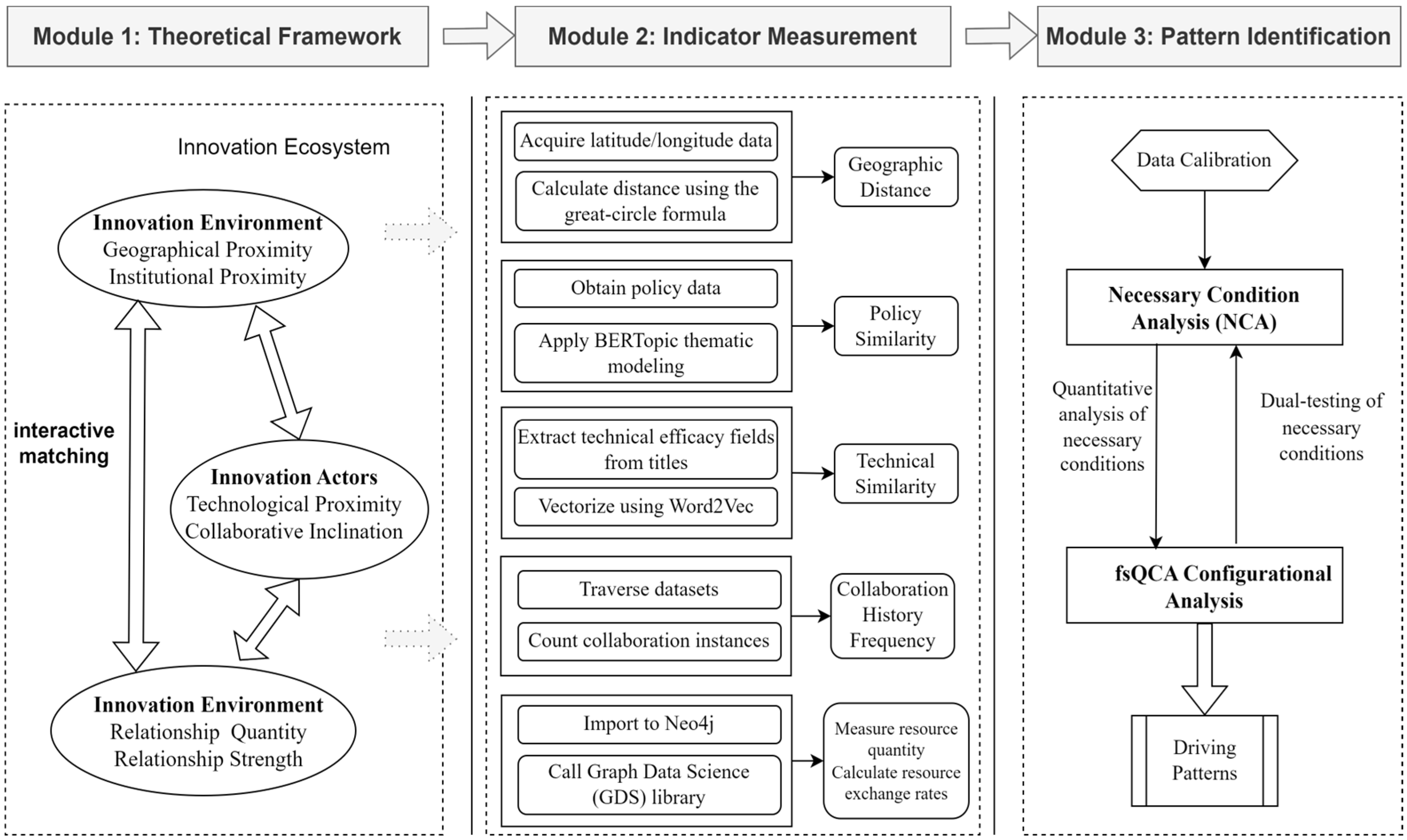

3.1. Research Framework and Process

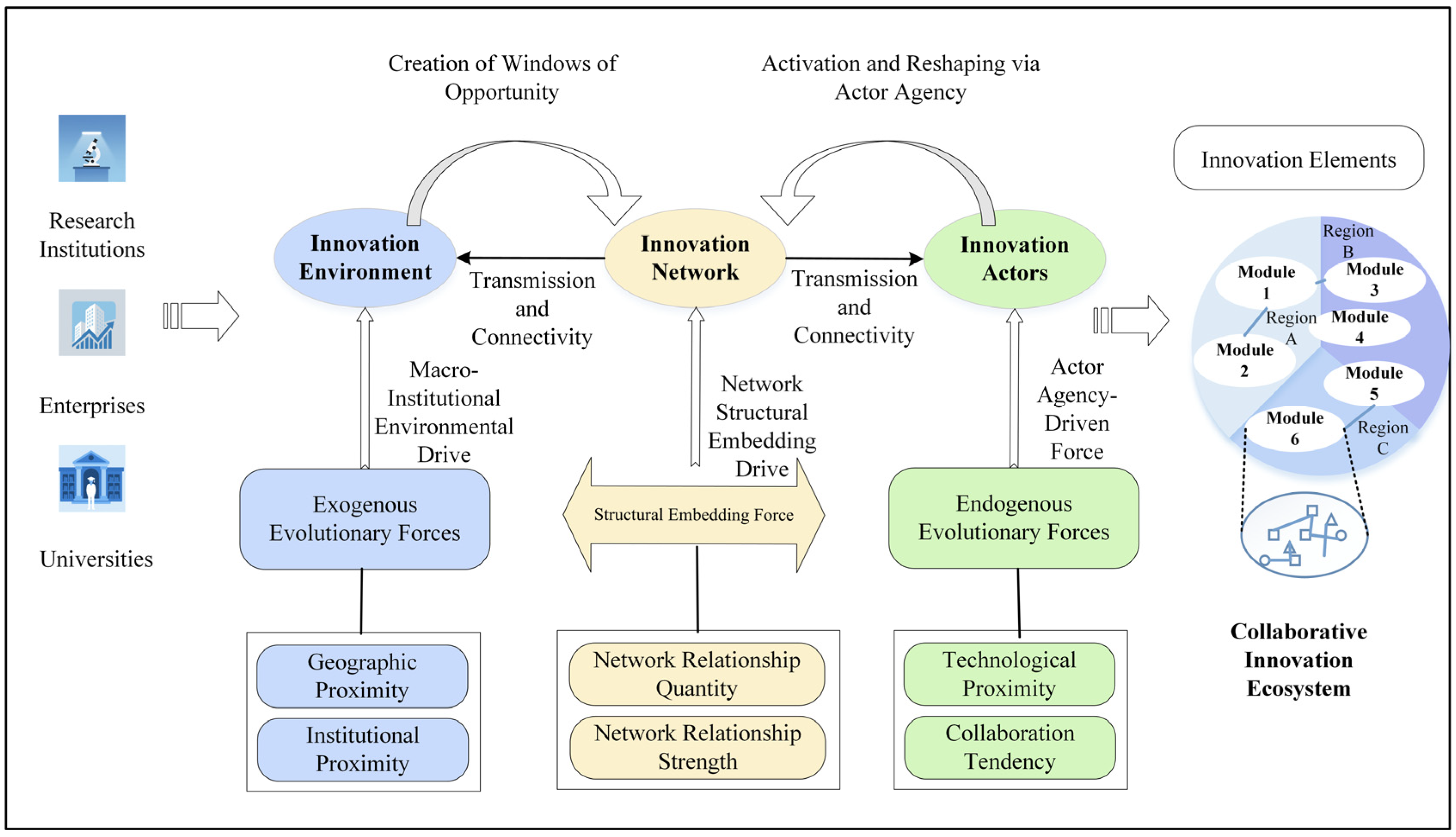

3.2. Theoretical Framework: Constructing the Innovation Ecosystem for Innovation Collaboration

3.3. Configurational Analysis of Collaboration Performance

3.3.1. Variable Measurement

- (1)

- Outcome Variable

- (2)

- Condition Variables

- Geographic Proximity (Geo)

- Institutional Proximity (Ins)

- Technological Proximity (Tec)

- Collaboration Tendency (Col)

- Network Relationship Quantity (NRQ)

- Network Relationship Strength (NRS)

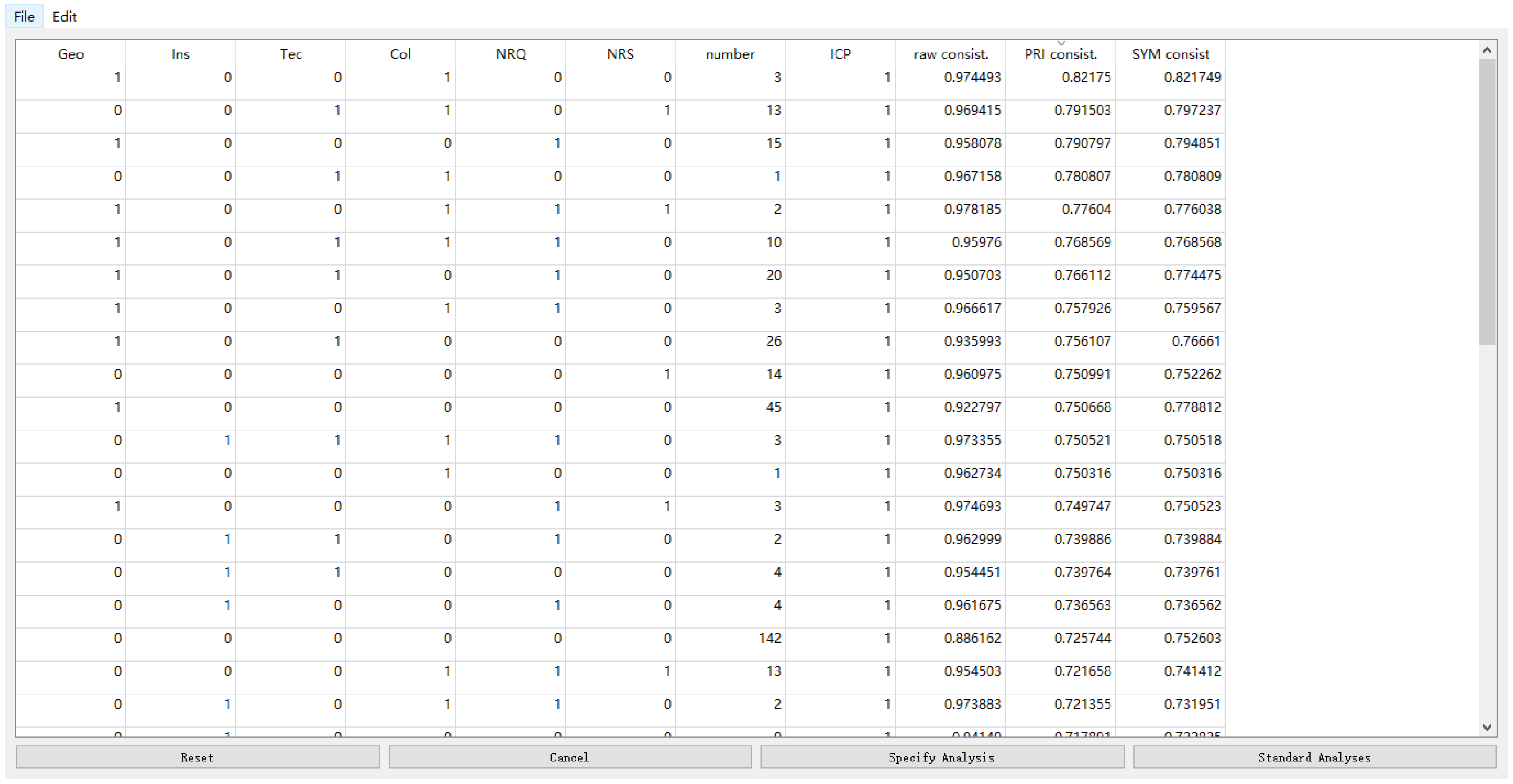

3.3.2. Variable Calibration

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

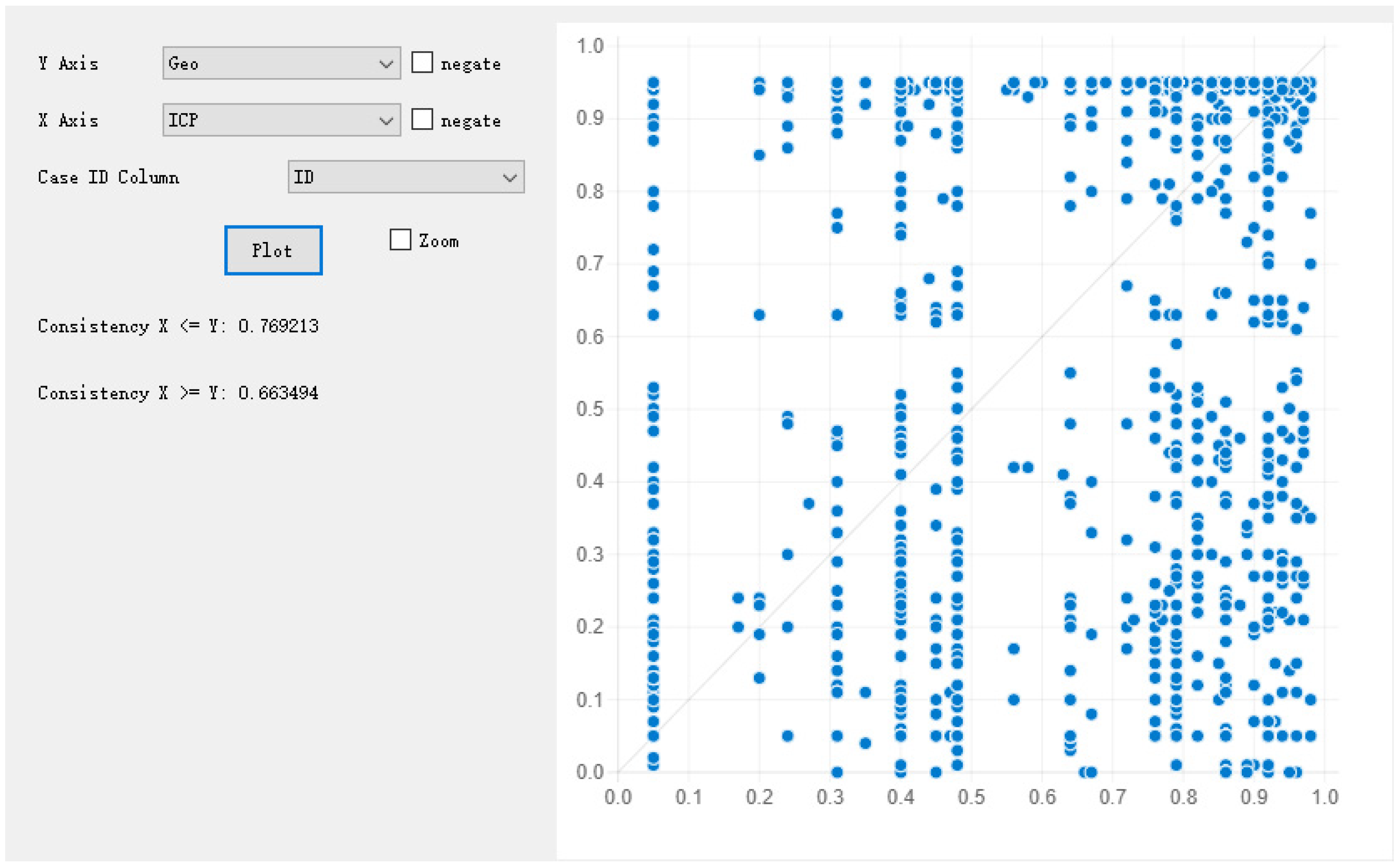

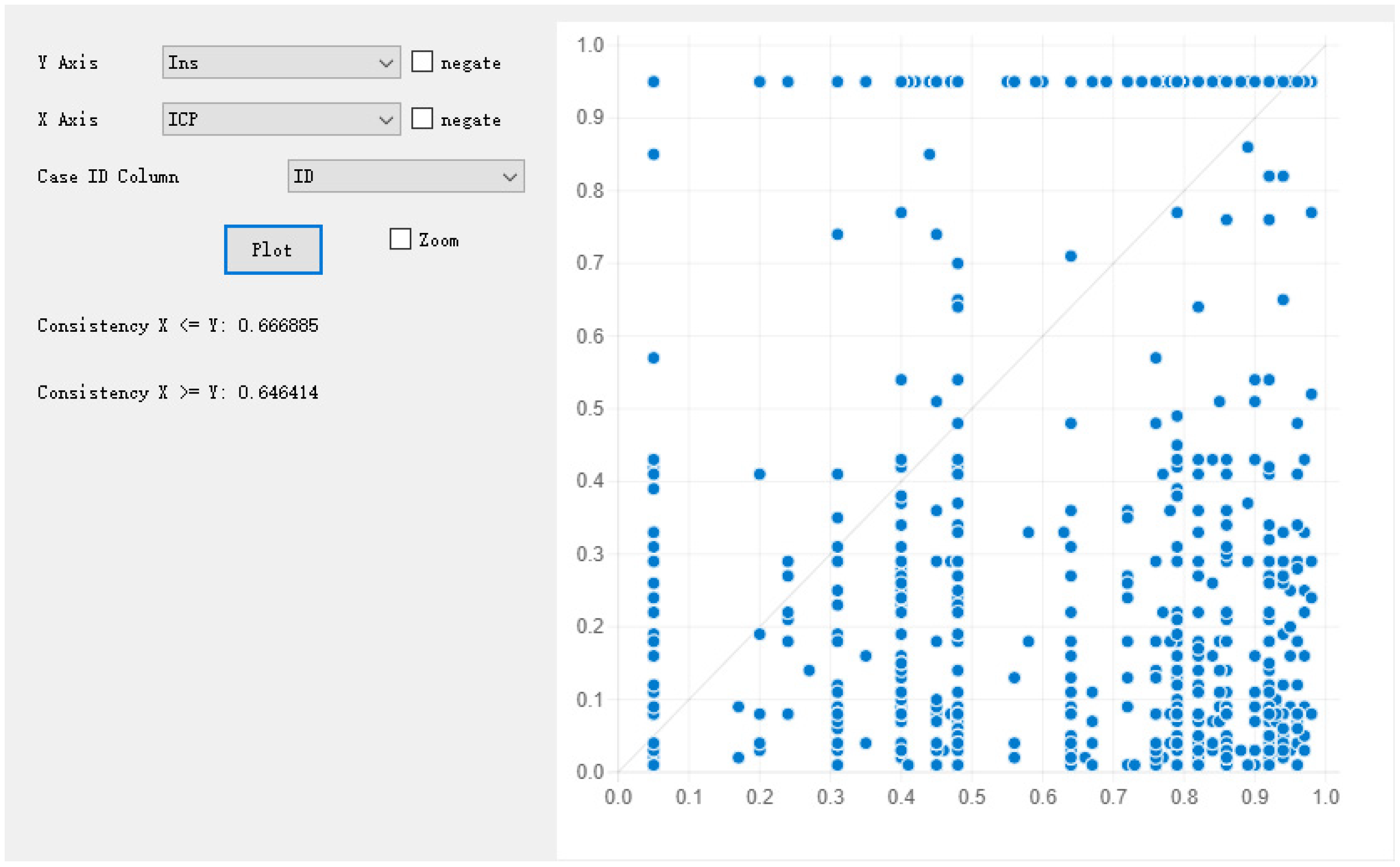

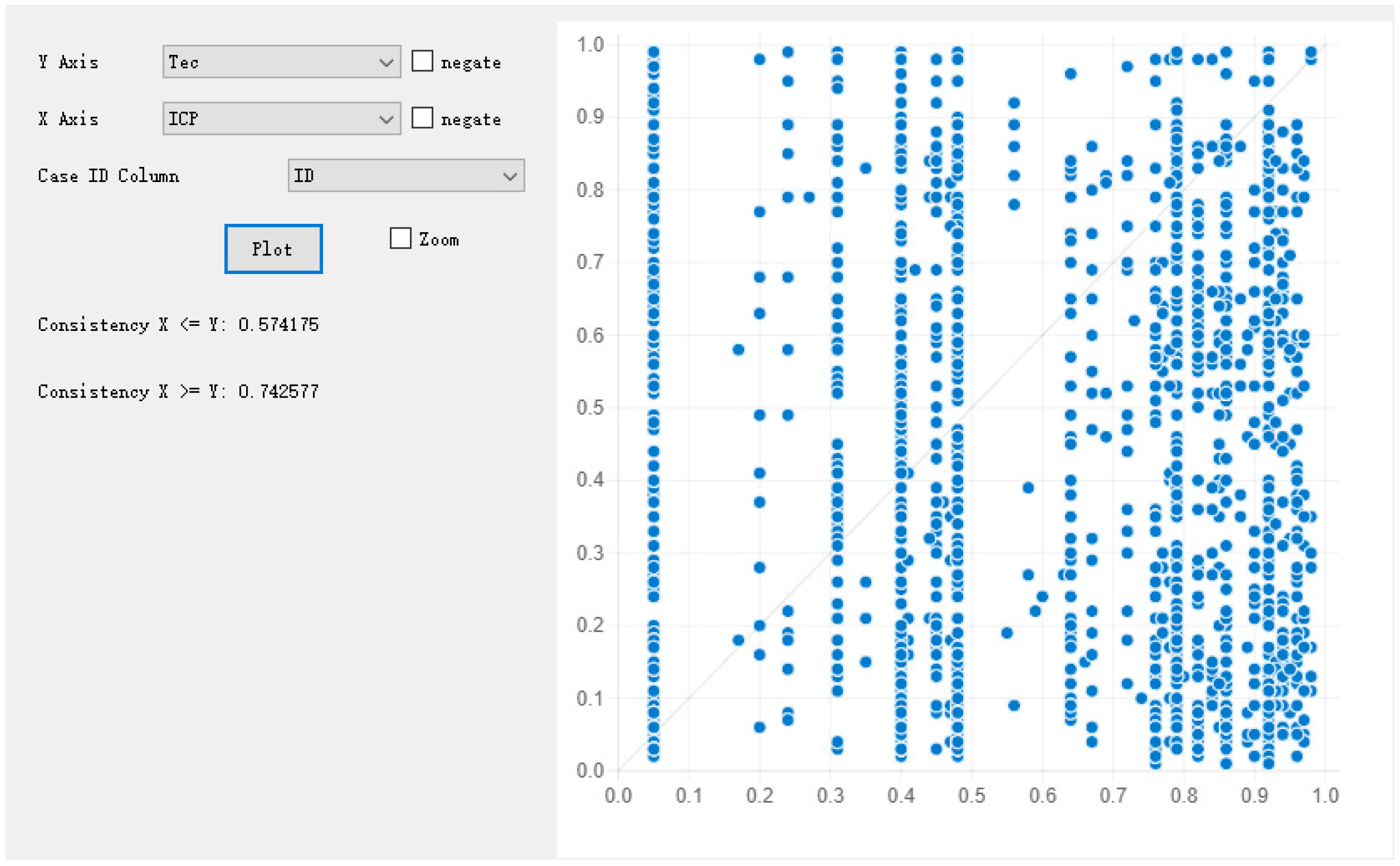

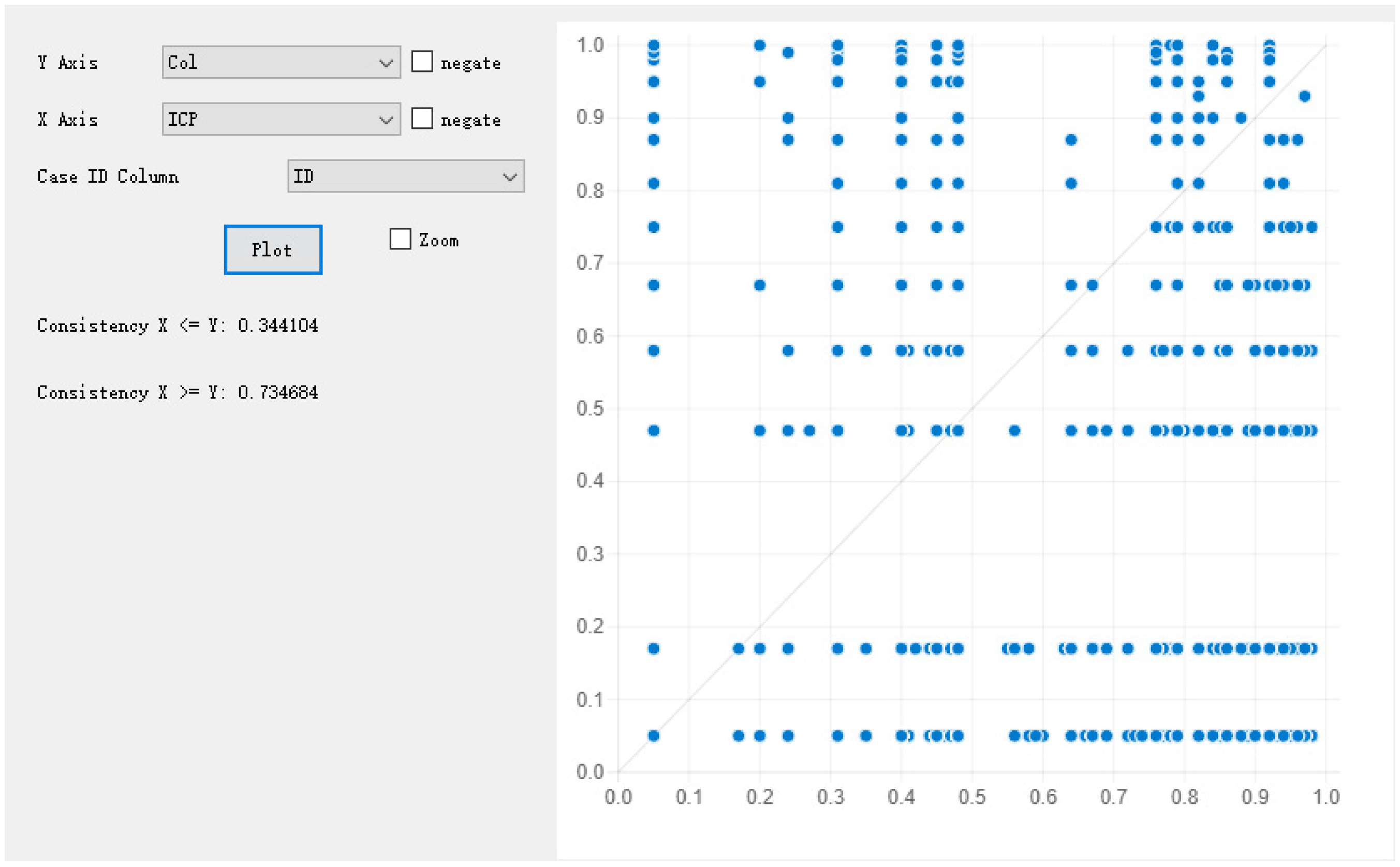

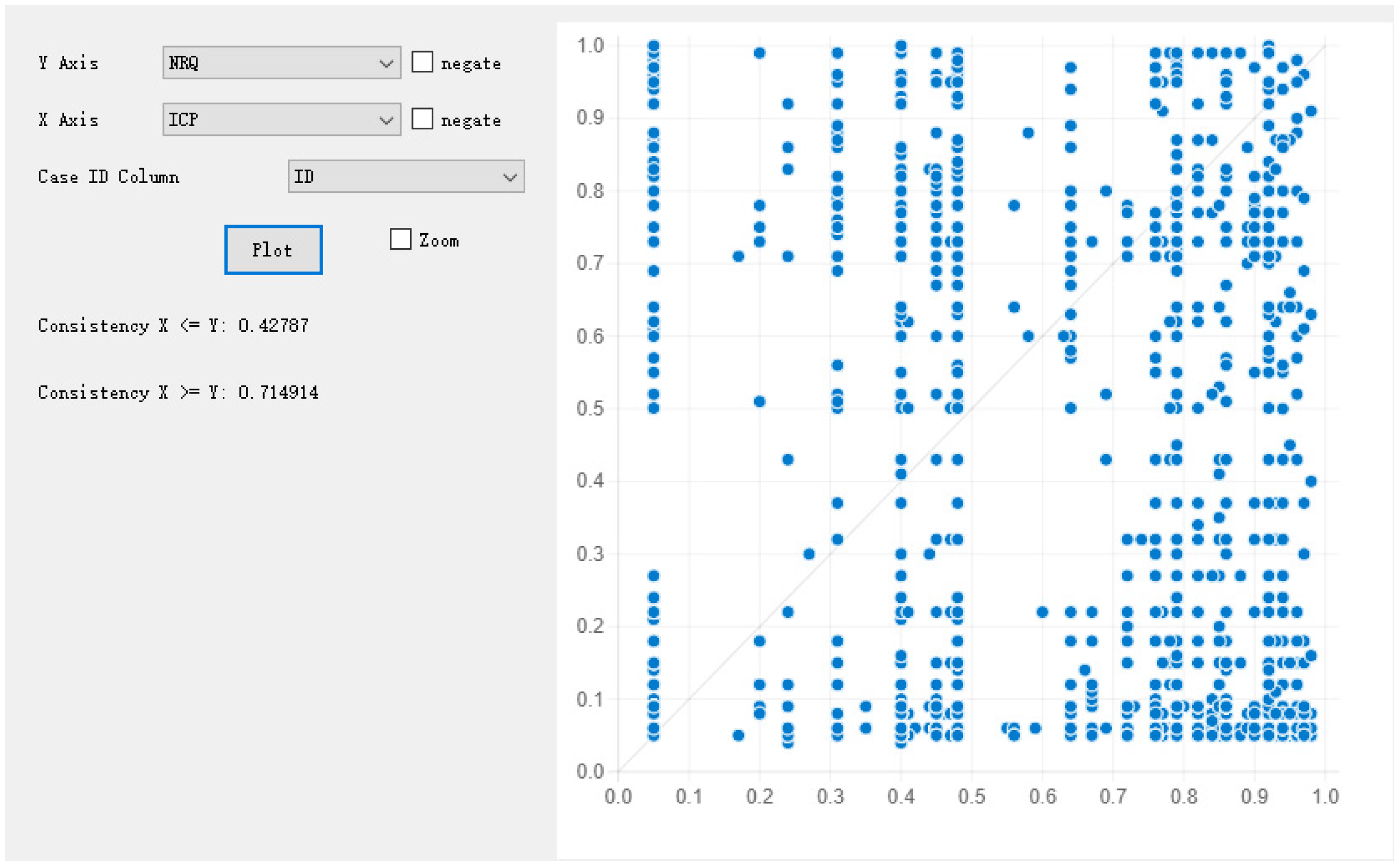

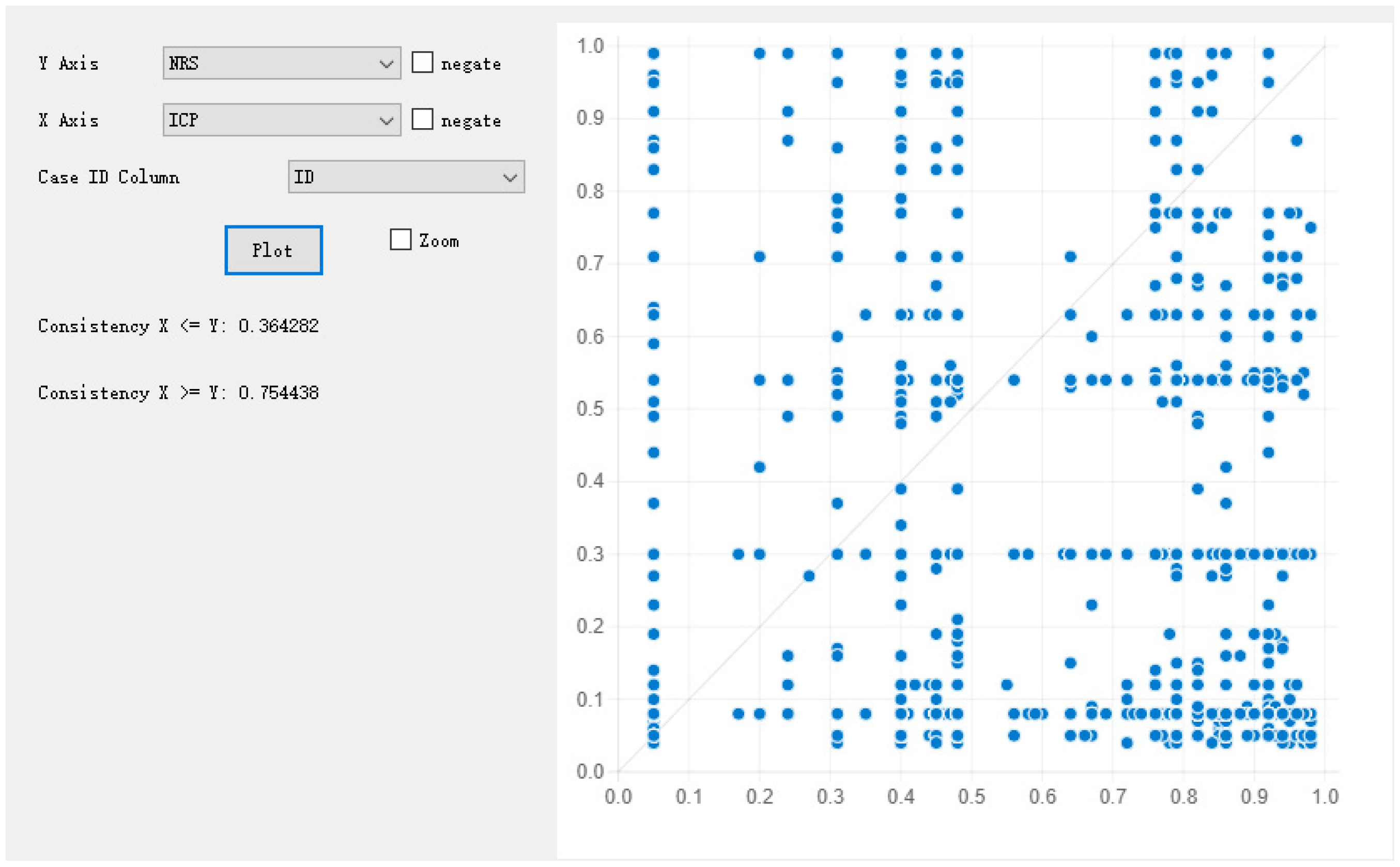

4.2. Necessary Condition Analysis of Innovation Collaboration Performance

4.3. Configurational Analysis Results of Innovation Collaboration Performance

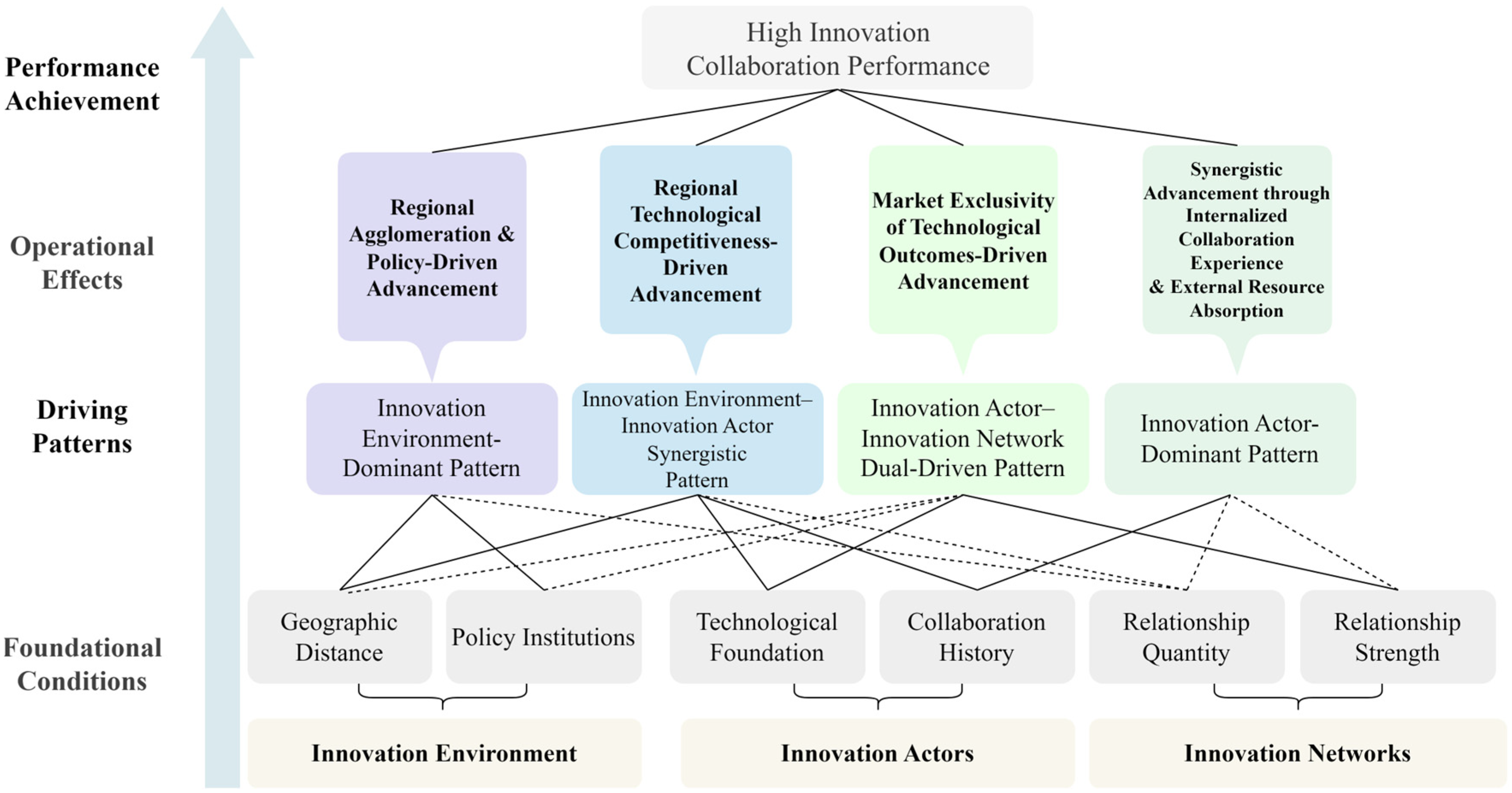

4.3.1. Analysis of High-Performance Configurations

- (1)

- Innovation Environment-Dominant Pattern

- (2)

- Innovation Environment–Innovation Actor Synergistic Pattern

- (3)

- Innovation Actor–Innovation Network Dual-Driven Pattern

- (4)

- Innovation Actor-Dominant Pattern

4.3.2. Analysis of Low Performance Configurations

4.4. Configurational Patterns for Achieving High Innovation Collaboration Performance

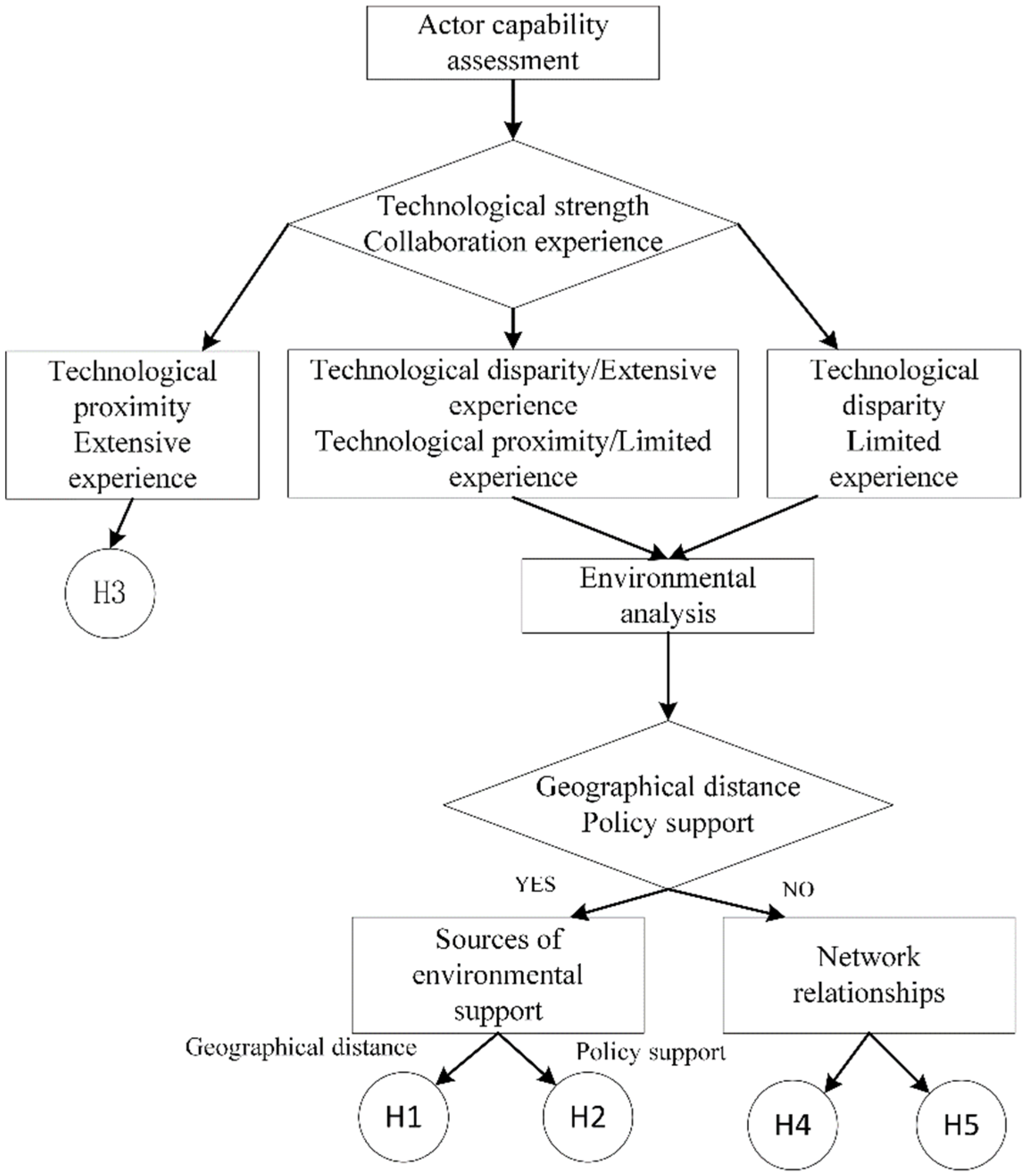

4.5. Decision Tree-Based Selection of Innovation Collaboration Configurations and Contextual Matching

4.6. Analysis of Innovation Collaboration Contexts and Industry Fit

4.7. Robustness Analysis

5. Conclusions and Prospects

5.1. Main Conclusions

5.2. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. H1 Case Interpretation

Appendix A.2. H2 Case Interpretation

Appendix A.3. H3 Case Interpretation

Appendix A.4. H4 Case Interpretation

Appendix A.5. H5 Case Interpretation

Appendix B

References

- Leahey, E. From Sole Investigator to Team Scientist: Trends in the Practice and Study of Research Collaboration. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2016, 42, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Q.; Zhang, G. Innovation Ecosystem: Exploring the Nature of Innovation-Driven and Innovation Paradigm Change. Technol. Prog. Policy 2016, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.L.; Yang, P.P.; Wang, Q. Innovation ecosystem—The fourth driving force to promote the innovation development. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2022, 40, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.H.; Ning, H.T. Influence of Structural Characteristics of Patent Cooperation Network on Enterprise Patent Quality: Taking the Integrated Circuit Industry as an Example. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2023, 43, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Sun, J.J. Knowledge Network Construction and Knowledge Measurement of the S&T Innovation Team. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2022, 41, 900–914. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.Q.; Li, T. Research on Enterprise Network Digital Transformation Path under the Background of Digital Economy. Sci. Sci. Manag. ST 2021, 42, 128–145. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.J.; Xie, F.J.; Wang, H.H. The impact of institutional proximity and technological proximity on industry-university collaborative innovation performance: An analysis of joint—patent data. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2017, 35, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegenfeld, A.F.; Bar-Yam, Y. An Introduction to Complex Systems Science and Its Applications. Complexity 2020, 2020, 6105872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Z.; Jia, L.D. Configurational Perspective and Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): A New Pathway for Management Research. Manag. World 2017, 2017, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Z.; Li, J.X.; Liu, Q.C.; Zhao, S.T.; Chen, K.W. Configurational theory and QCA method from a complex dynamic perspective: Research progress and future directions. Manag. World 2021, 37, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.J.; Shepherd, D.A.; Prentice, C. Using Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis for a Finer-Grained Understanding of Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.F. Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R. Match Your Innovation Strategy to Your Innovation Ecosystem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R.; Kapoor, R. Value Creation in Innovation Ecosystems: How the Structure of Technological Interdependence Affects Firm Performance in New Technology Generations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R. Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chang, J.; Wang, M.J.; Zhu, X.Y.; Jin, A.M. Innovation 3.0 and innovation ecosystem. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2014, 32, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorelli, H.B. Networks: Between Markets and Hierarchies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1986, 7, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.H.; Zhang, G.Y.; Liao, J.C. A Study on the Evolution Mechanism of Disruptive Innovation Based on SNM Perspective. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2016, 2, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. An Integrative Framework for Understanding the Innovation Ecosystem; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.F. Business Ecosystems and the View from the Firm. Antitrust Bull. 2006, 51, 31–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; Koput, K.W.; Smith-Doerr, L. Interorganizational Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 116–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granstrand, O.; Holgersson, M. Innovation Ecosystems: A Conceptual Review and a New Definition. Technovation 2020, 90, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.T.; Gilly, J.-P. On the Analytical Dimension of Proximity Dynamics. Reg. Stud. 2000, 34, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Zhao, Y.S.; Huang, H.Y.; Chu, S.Z. Empirical Analysis on Influential Factors of Cross-regional Innovation Cooperation in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Based on Patent Cooperation Data. China Pharm. 2020, 31, 641–646. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Ying, Y.; Liu, Y. R&D geographic dispersion, technology diversity, and innovation performance. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2013, 31, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.H.; Gong, Z.G. Impact of multidimensional proximities on cross region technology innovation cooperation: Experical analysis based on Chinese coinvent patent data. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2013, 31, 1590–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Tang, H.M.; Wang, Y.F.; Tang, X.L. Effect of Geographical Proximity on the Formation of Cooperation Partnership and Technological Innovation Performance. RD Manag. 2016, 28, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Song, C.J. Impact of Geographical Proximity and Cognitive Proximity on Ambidextrous Innovation of Technological Innovation Network. China Soft Sci. 2017, 4, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Boschma, R. Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trippl, M. Developing Cross-Border Regional Innovation Systems: Key Factors and Challenges. Tijd. Voor. Econ. Soc. Geog. 2010, 101, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.T.; Teng, T.W.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, G. Evolution’s characteristics and influence factors of China’s universities knowledge collaboration network. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2020, 37, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.M.; Yin, H.; Wen, J.Y. Scientific Collaboration Network Relational Capital, Proximity and Enterprise Technological Innovation. Performance. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhao, Q.K.; Xu, Y. Research on Influencing Factors of Emerging Technology Cooperation Innovation Network Formation: Patent Data Based on Virtual Reality Technology. Sci. Decis.-Mak. 2024, 2, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Luo, J.Q.; Peng, Y.T. The Structure Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of Intelligent Connected Vehicle’s Transnational Technical Cooperation Network. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2022, 39, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vaez-Alaei, M.; Deniaud, I.; Marmier, F.; Gourc, D.; Cowan, R. A Decision-Making Framework Based on Knowledge Criteria for Network Partner Selection. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Systems Management (IESM), Shanghai, China, 25–27 September 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J.C.; Yan, Y. Technological Proximity and Recombinative Innovation in the Alternative Energy Field. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1460–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Zaby, A.K. Research Joint Ventures and Technological Proximity. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Li, N. Partner Technological Heterogeneity and Innovation Performance of R&D Alliances. RD Manag. 2022, 52, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.M.; Zhou, T. The Relationship Between Knowledge Base and Innovative Performance: A New Relational Perspective of Knowledge Elements. Sci. Sci. Manag. ST 2015, 36, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.Y.; Wang, C.; Dong, K.; Wei, L.; Pang, H.S. Methods to Identify Potential Industry-University-Research Institutions Co-operation Partners Based on the Knowledge Spillovers Effects in the Innovation Chain. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2017, 36, 682–694. [Google Scholar]

- Ariño, A.; Abramov, M.; Skorobogatykh, I.; Rykounina, I.; Vilà, J. Partner Selection and Trust Building in West European–Russian Joint Ventures: A Western Perspective. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1997, 27, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.T.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, R.N.; Zhang, L. Three-dimensional measurement of scientific collaboration sustainability: Library and Information Science (LIS) and Physics & Astronomy (PHYS) as examples. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2025, 44, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.X.; Su, J.L.; Hu, C. Research on the Influence of Enterprise Network Position and Relationship Intensity on Technological Innovation Performance in IUR Cooperation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2020, 37, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ferriani, S.; Cattani, G.; Baden-Fuller, C. The Relational Antecedents of Project-Entrepreneurship: Network Centrality, Team Composition and Project Performance. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 1545–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Tan, J.S. Alliance Network and Corporate Innovation Performance: A Cross-Level Analysis. Manag. World 2014, 2014, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xuan, L.; Chen, W.F.; Han, X. Research on Geographical Proximity, Organizational Proximity, Network Location and Innovation Performance in the Seed Industry Alliance Network. Technol. Econ. 2020, 39, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, J. How Multiple Networks Help in Creating Knowledge: Evidence from Alternative Energy Patents. Scientometrics 2018, 115, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, P.V.; Perry-Smith, J. Social Networks and Novelty Recognition: A Review and Research Agenda. Innovation 2024, 26, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, M. Network Updating and Exploratory Learning Environment. J. Manag. Stud. 2004, 41, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Y.; Wang, J.P. Network Connection Strength, Innovation Pattern and Technology Innovation Performance: Based on Moderating Effect of the Innovation Openness. Sci. Sci. Manag. 2017, 38, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, X.J.; Wang, F.B. The Application of Qualitative Comparative Analysis(QCA) in Configuration Research in Business Administration Field: Commentary and Future Directions. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2017, 39, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.D.; Tsui, A.S.; Hinings, C.R. Configurational Approaches to Organizational Analysis. AMJ 1993, 36, 1175–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Du, Y.Z. Qualitative Comparative Analysis(QCA) in Management and Organization Research: Position, Tactics, and Directions. Chin. J. Manag. 2019, 16, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Dul, J. Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA): Logic and Methodology of “Necessary but Not Sufficient” Causality. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 10–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Introduction and Application of Necessary Condition Analysis Method: An Illustrative Case. Organ. Manag. 2017, 2017, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; van der Laan, E.; Kuik, R. A Statistical Significance Test for Necessary Condition Analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 23, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, C.; Langley, A. What Makes a Process Theoretical Contribution? Organ. Theory 2020, 1, 2631787720902473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building Better Causal Theories: A Fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research. AMJ 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolloch, M.; Dellermann, D. Digital Innovation in the Energy Industry: The Impact of Controversies on the Evolution of Innovation Ecosystems. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 136, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Zhang, R.; Ma, G.Y. Review and Prospect of Foreign Literature on Innovation Ecosystem. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 21, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, W.P. Has Catch-up Strategy of Innovation Inhibited the Quality of China’s Patents? Econ. Res. J. 2018, 53, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J. The Importance of Patent Scope: An Empirical Analysis. RAND J. Econ. 1994, 25, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.L.; Song, Y. Designing and Applying of Market Segmentation Index Based on Spatial Distance Measurement. J. Stat. Inf. 2021, 36, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.F.; Sun, S.H.; Hu, Q. The Influence of Multi-dimensional Proximity and Interactivity on the Evolution of Cooperative Innovation Network: A Case Study of China’s Intelligent Manufacturing Equipment Industry. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2024, 42, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.C.; Zhao, P.H. An Empirical Study of Influencing Factors of Collaborative Innovation Performance in Yangtze River Delta from Perspective of Proximity. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2020, 40, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Jiang, E.B.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Liu, T. Policy Tool Identification Method and Empirical Research Based on Deep Learning. Libr. Inf. Serv. 2021, 65, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, D.H.; Wang, X.F.; Zhu, F.J.; Heng, X.F. Technical topic analysis in patents: SAO-based LDA modeling. Libr. Inf. Serv. 2017, 61, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.G.; Zhang, L.; Xie, W.L.; Dang, T.T. Mining and Analysis of User Requirements for Online Open Courses by Integrating BERTopic and KANO Models. Inf. Sci. 2024, 42, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, G.; Martino, C.; Rahman, G.; Gonzalez, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Mishne, G.; Knight, R. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) Reveals Composite Patterns and Resolves Visualization Artifacts in Microbiome Data. mSystems 2021, 6, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Astels, S. Hdbscan: Hierarchical Density Based Clustering. JOSS 2017, 2, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Huang, J.; Zhao, W.Y.; Xiao, S.C.; Feng, L.J. A method for technology opportunity identification under the coupling of cross-domain analog technology elements. J. Intell. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.F.; Yang, Q.; Hou, X.Z.; Yin, M. Research on Guided Network Sensitive Information Identification Based on SSI-GuidedLDA Model. J. Intell. 2023, 42, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.N.; Shen, J.L.; Li, J. Research on Innovative Combination Model of Bio-pharmaceutical Industry Cluster Based on Social Network Theory: Taking Jiangsu Province as an Example. Sci. Technol. 2023, 43, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Adamic, L.A.; Adar, E. Friends and Neighbors on the Web. Soc. Netw. 2003, 25, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, M.A.; Semadeni, M.; Cannella, A.A. Value of Strong Ties to Disconnected Others: Examining Knowledge Creation in Biomedicine. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, M.F.; Sun, X.M.; Wang, C.Y. The Impact of the Change of Network Ties Strength of Overseas Research Talents on Its Creativity Science & Technology. Prog. Policy 2018, 35, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- An, W.W.; Xu, Y.T.; Zeng, D.M.; Dai, H.W. How to Win Dominant Design of Strategic Emerging Industry? —Based on the Perspective of Configuration Matching. RD Manag. 2022, 34, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Wen, Y.; Xu, Y.Y. Research on the Evolution Trend of Industry-University-Research Collaborative Innovation Network in Yangtze River Delta: The Perspective of Enterprises in Zhejiang Province. Sci. Manag. 2022, 42, 16–24+95. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, X.M. Mechanisms and paths to enhance the effectiveness of the national innovation system—Based on the collaborative perspective of “science technology industry”. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2024, 42, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Z.; Liu, Q.C.; Chen, K.W.; Xiao, R.Q.; Li, S.S. Ecosystem of Doing Business, Total Factor Productivity and Multiple Patterns of High-quality Development of Chinese Cities: A Configuration Analysis Based on Complex Systems View. Manag. World 2022, 38, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.B.; Fan, Z.T.; Du, Y.Z. Technology Management Capability, Attention Allocation and Local Government Website Construction: A Configuration Analysis Based on TOE Framework. Manag. World 2019, 35, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable Name (Abbreviation) | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition variables | Innovation environment | Geographic proximity (Geo) | Spatial distance between collaborating institutions |

| Institutional proximity (Ins) | Degree of similarity in policy environments between collaborating institutions | ||

| Innovation actors | Technological proximity (Tec) | Extent of technological similarity between collaborating institutions | |

| Collaboration tendency (Col) | Frequency of prior collaborative engagements | ||

| Innovation networks | Network relationship quantity (NRQ) | Total number of direct collaborative ties within the innovation network | |

| Network relationship strength (NRS) | Intensity of existing collaborative ties within the innovation network | ||

| Outcome variable | Innovation collaboration performance (ICP) | The richness of innovative elements and technical details in collaborative patents | |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Code | Calibration Anchor Points | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Membership | Crossover Point | Full Non-Membership | ||||

| (μ = 0.95) | (Mean) | (μ = 0.05) | ||||

| Outcome variable | Innovation collaboration performance | ICP | 0.765 | 0.513 | 0 | |

| Condition variables | Innovation environment | Geographic proximity | Geo | 0.999 | 0.963 | 0.850 |

| Institutional proximity | Ins | 1.000 | 0.785 | 0.314 | ||

| Innovation actors | Technological proximity | Tec | 0.864 | 0.527 | 0.279 | |

| Collaboration tendency | Col | 11.000 | 3.098 | 1.000 | ||

| Innovation networks | Network relationship quantity | NRQ | 22.133 | 7.035 | 1.000 | |

| Network relationship strength | NRS | 15.870 | 3.663 | 0.910 | ||

| Variables | Method | Accuracy | Ceiling Zone | Scope | Effect Size (d) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic proximity (Geo) | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.88 | 0.000 | 0.778 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.88 | 0.001 | 0.754 | |

| Institutional proximity (Ins) | CR | 100% | 0.002 | 0.87 | 0.000 | 0.172 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.87 | 0.001 | 0.179 | |

| Technological proximity (Tec) | CR | 99.6% | 0.002 | 0.91 | 0.002 | 0.411 |

| CE | 100% | 0.002 | 0.91 | 0.002 | 0.511 | |

| Collaboration tendency (Col) | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.88 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.88 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Network relationship quantity (NRQ) | CR | 100% | 0.003 | 0.89 | 0.003 | 0.044 |

| CE | 100% | 0.006 | 0.89 | 0.006 | 0.029 | |

| Network relationship strength (NRS) | CR | 100% | 0.000 | 0.88 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| CE | 100% | 0.000 | 0.88 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Innovation Collaboration Performance (ICP) | Geographic Proximity (Geo) | Institutional Proximity (Ins) | Technological Proximity (Tec) | Collaboration Tendency (Col) | Network Relationship Quantity (NRQ) | Network Relationship Strength (NRS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 0.0 | NN |

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 0.2 | NN |

| 60 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 0.4 | NN |

| 70 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 0.5 | NN |

| 80 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 0.7 | NN |

| 90 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 0.9 | NN |

| 100 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 8.9 | NN | 1.0 | NN |

| Antecedent Variables | High Innovation Collaboration Performance | Low Innovation Collaboration Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| Geographic proximity (Geo) | 0.769 | 0.663 | 0.806 | 0.475 |

| ~Geographic proximity (~Geo) | 0.392 | 0.747 | 0.430 | 0.560 |

| Institutional proximity (Ins) | 0.667 | 0.646 | 0.715 | 0.560 |

| ~Institutional proximity (~Ins) | 0.458 | 0.701 | 0.467 | 0.490 |

| Technological proximity (Tec) | 0.574 | 0.742 | 0.665 | 0.589 |

| ~Technological proximity (~Tec) | 0.682 | 0.748 | 0.709 | 0.533 |

| Collaboration tendency (Col) | 0.344 | 0.734 | 0.444 | 0.649 |

| ~Collaboration tendency (~Col) | 0.835 | 0.687 | 0.818 | 0.460 |

| Network relationship quantity (NRQ) | 0.428 | 0.715 | 0.523 | 0.597 |

| ~Network relationship quantity (~NRQ) | 0.759 | 0.699 | 0.751 | 0.473 |

| Network relationship strength (NRS) | 0.364 | 0.754 | 0.477 | 0.676 |

| ~Network relationship strength (~NRS) | 0.844 | 0.702 | 0.827 | 0.471 |

| Antecedent Condition | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic proximity (Geo) | ⬤ | ⬤ | ● | ||

| Institutional proximity (Ins) | ⊗ | ⬤ | ● | ⊗ | |

| Technological proximity (Tec) | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ||

| Collaboration tendency (Col) | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⬤ | |

| Network relationship quantity (NRQ) | ● | ● | ⊗ | ● | |

| Network relationship strength (NRS) | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ||

| Consistency | 0.891 | 0.955 | 0.939 | 0.931 | 0.940 |

| Raw coverage | 0.230 | 0.127 | 0.154 | 0.174 | 0.131 |

| Unique coverage | 0.029 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.052 | 0.007 |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.833 | ||||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.460 | ||||

| Context Type | Characteristic Description | Matching Configurations | Applicable Industries |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Innovation environment-dominant pattern | Innovation activities rely heavily on geographical agglomeration, policy convergence, and unified governance frameworks; highly sensitive to changes in the innovation environment. | H1/H2 | Biopharma, artificial intelligence: strong regulatory regimes; approval and policy frameworks largely determine technological directions. Clean energy: strongly driven by the national “dual-carbon” strategy. |

| (B) Innovation environment–innovation actor synergistic pattern | Requires a combination of technological proximity, geographical proximity, and accumulated collaboration experience. | H3 | Clean energy, artificial intelligence: rapid evolution of technological trajectories. semiconductors: highly dependent on collaborative R&D; |

| (C) Innovation actor–innovation network dual-driven pattern | High technological alignment + strong-tie networks; substantial geographical or policy heterogeneity across actors. | H4 | Equipment manufacturing: typical strong-tie supply-chain structures. Chemical materials: stable upstream–downstream application networks. Semiconductors: supply chains are globally dispersed but technological paths remain highly locked-in. |

| (D) Innovation actor-dominant pattern | Significant technological and institutional heterogeneity, but strong collaboration experience and rich relationship networks compensate for coordination gaps. | H5 | Equipment manufacturing: long-term collaboration experience shapes innovation processes. Chemical materials: relies on long-term process expertise and iterative experimentation networks. |

| Antecedent Condition | Adjusting the Consistency Threshold | Modifying the Case Frequency Threshold | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 | |

| Geographic proximity (Geo) | ⬤ | ⬤ | ● | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ● | |||

| Institutional proximity (Ins) | ⊗ | ⬤ | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ● | ⊗ | ||

| Technological proximity (Tec) | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ||||

| Collaboration tendency (Col) | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ● | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ||

| Network relationship quantity (NRQ) | ● | ● | ⊗ | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ | ● | ||

| Network relationship strength (NRS) | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⬤ | |||||

| Consistency | 0.891 | 0.955 | 0.939 | 0.931 | 0.940 | 0.891 | 0.955 | 0.939 | 0.931 | 0.940 |

| Raw coverage | 0.230 | 0.127 | 0.154 | 0.174 | 0.131 | 0.230 | 0.127 | 0.154 | 0.174 | 0.132 |

| Unique coverage | 0.029 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.052 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.052 | 0.011 |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.833 | 0.833 | ||||||||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.460 | 0.460 | ||||||||

| Antecedent Condition | L1a | L1b | L2 | P1 | P2 | P3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic proximity (Geo) | ● | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ● | |

| Institutional proximity (Ins) | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ⬤ |

| Technological proximity (Tec) | ● | ⬤ | ● | |||

| Collaboration tendency (Col) | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ● | ⊗ | ⬤ |

| Network relationship quantity (NRQ) | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ● | ||

| Network relationship strength (NRS) | ● | ● | ⊗ | |||

| Consistency | 0.971 | 0.968 | 0.951 | 0.948 | 0.921 | 0.933 |

| Raw coverage | 0.118 | 0.127 | 0.140 | 0.121 | 0.204 | 0.170 |

| Unique coverage | 0.009 | 0.021 | 0.036 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.004 |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.939 | 0.793 | ||||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.177 | 0.789 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Xu, H.; Haunschild, R.; Tong, Z.; Liu, C. Research on the Configurational Paths of Collaborative Performance in the Innovation Ecosystem from the Perspective of Complex Systems. Systems 2025, 13, 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121116

Li X, Xu H, Haunschild R, Tong Z, Liu C. Research on the Configurational Paths of Collaborative Performance in the Innovation Ecosystem from the Perspective of Complex Systems. Systems. 2025; 13(12):1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121116

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xin, Haiyun Xu, Robin Haunschild, Zehua Tong, and Chunjiang Liu. 2025. "Research on the Configurational Paths of Collaborative Performance in the Innovation Ecosystem from the Perspective of Complex Systems" Systems 13, no. 12: 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121116

APA StyleLi, X., Xu, H., Haunschild, R., Tong, Z., & Liu, C. (2025). Research on the Configurational Paths of Collaborative Performance in the Innovation Ecosystem from the Perspective of Complex Systems. Systems, 13(12), 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121116