Wastewater Infrastructure as a Public Health Tool: Agent-Based Modeling of Surveillance Strategies in a COVID-19 Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- At the basic reproduction numbers (R0) of 4 and 8, how do the WBE detection sensitivity, sewage service status of the first SARS-CoV-2 carrier, and the cross-zone travel rate affect the number of days required for the viral concentration in the aggregated wastewater at the local wastewater treatment plant to reach the predefined WBE detection threshold?

- (2)

- At the basic R0 of 4 and 8, how do the WBE detection sensitivity, sewage service status of the first SARS-CoV-2 carrier, and the cross-zone travel rate affect the cumulative COVID-19 prevalence when the predefined WBE threshold is reached?

- (3)

- At the basic R0 of 4 and 8, how do the respective cumulative prevalences progress in the seven days after the WBE threshold is reached in the simulated county?

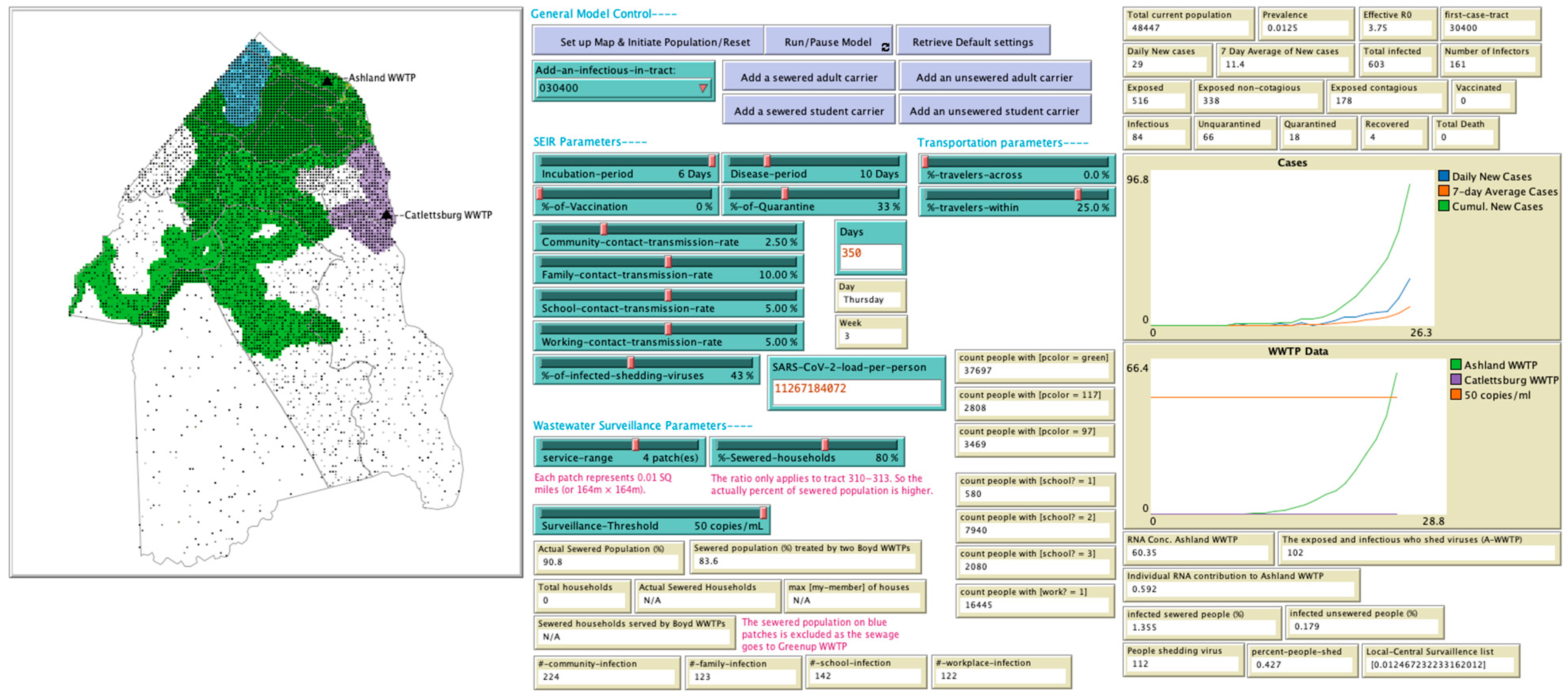

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. WBE Model Development

2.1.1. Purpose

2.1.2. Entities, State Variables, and Scales

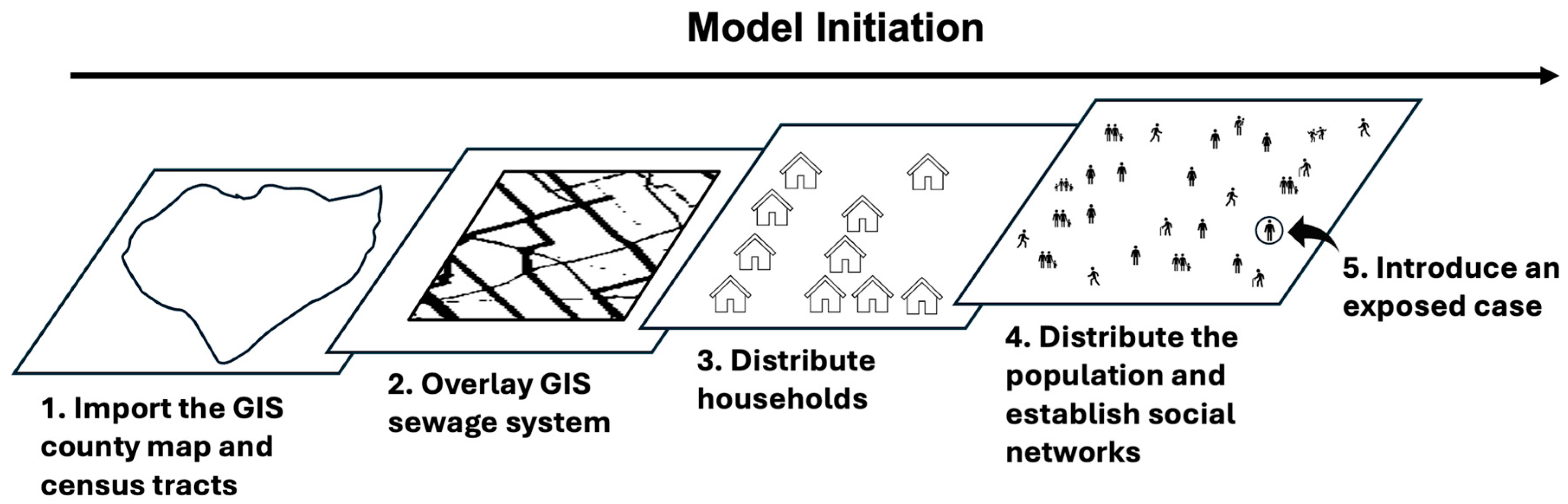

2.1.3. Initialization and Input

2.1.4. Process Overview and Scheduling

- Wastewater surveillance: The aggregated wastewater from the previous day was sampled and tested at the county’s wastewater treatment plant to measure the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies.

- Quarantine: The model examined the status of infectious agents and updated their quarantine status according to a defined quarantine rate.

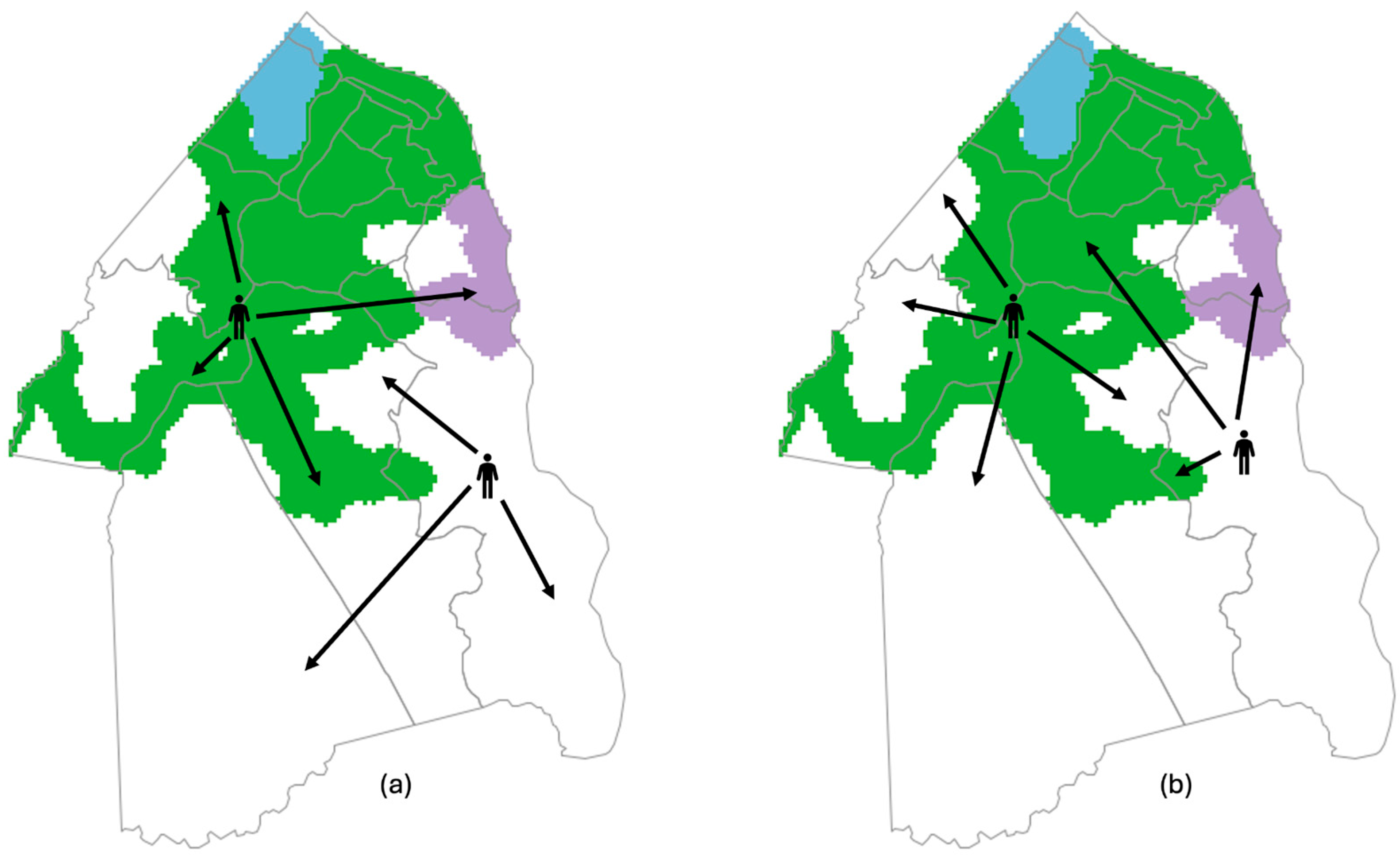

- Travel: Based on the defined community traveling rate, a portion of human agents aged 18–74 traveled across the sewered and non-sewered zones or within the sewered or non-sewered zones for reasons such as shopping, visiting friends, entertainment, etc. These travels are distinct from school and work activities. Cross-zone travel rates were varied as a part of our analysis to examine the effect of this variable.

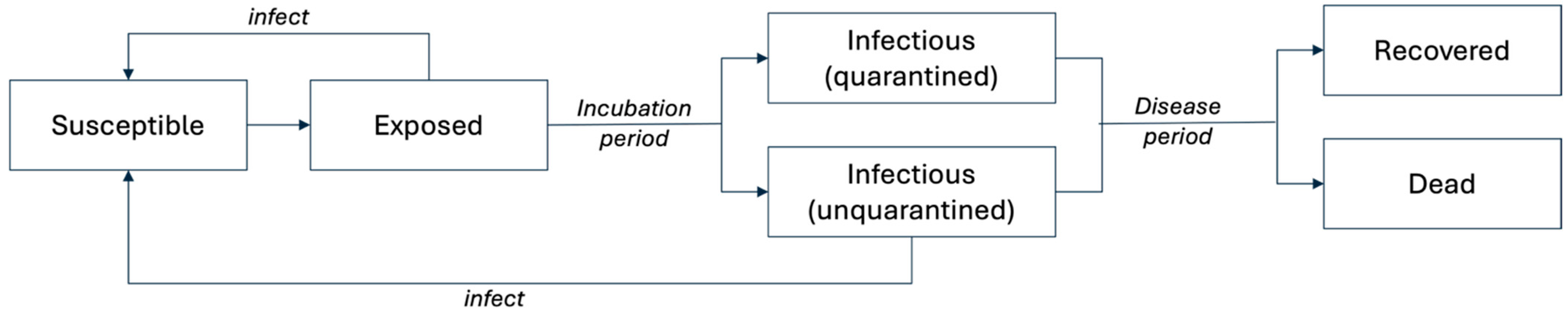

- Disease transmission through social networks: An SEIR compartmental model simulated SARS-CoV-2 viral transmission and disease progression. During this process, human agents contacted others through four social networks. Specifically, agents contacted family members, community members (i.e., other human agents on the same patch but excluded from family), classmates, and human agents in their workplace networks. During weekdays (Monday through Friday), PreK-college students (aged 0–17 and aged 18–64 enrolled in college) and workers (aged 18–64 and employed) also interacted with their classmates or colleagues. Exposed and unquarantined infectious individuals may transmit SARS-CoV-2 viruses to their susceptible contacts, based on a transmission rate defined for each network. The disease states of individual agents were updated after each interaction.

- Travel: Human agents who traveled in step 2 returned home.

- Iterating the model: The overall population disease status and simulated dates were updated.

2.1.5. Design Concepts

2.1.6. Submodels

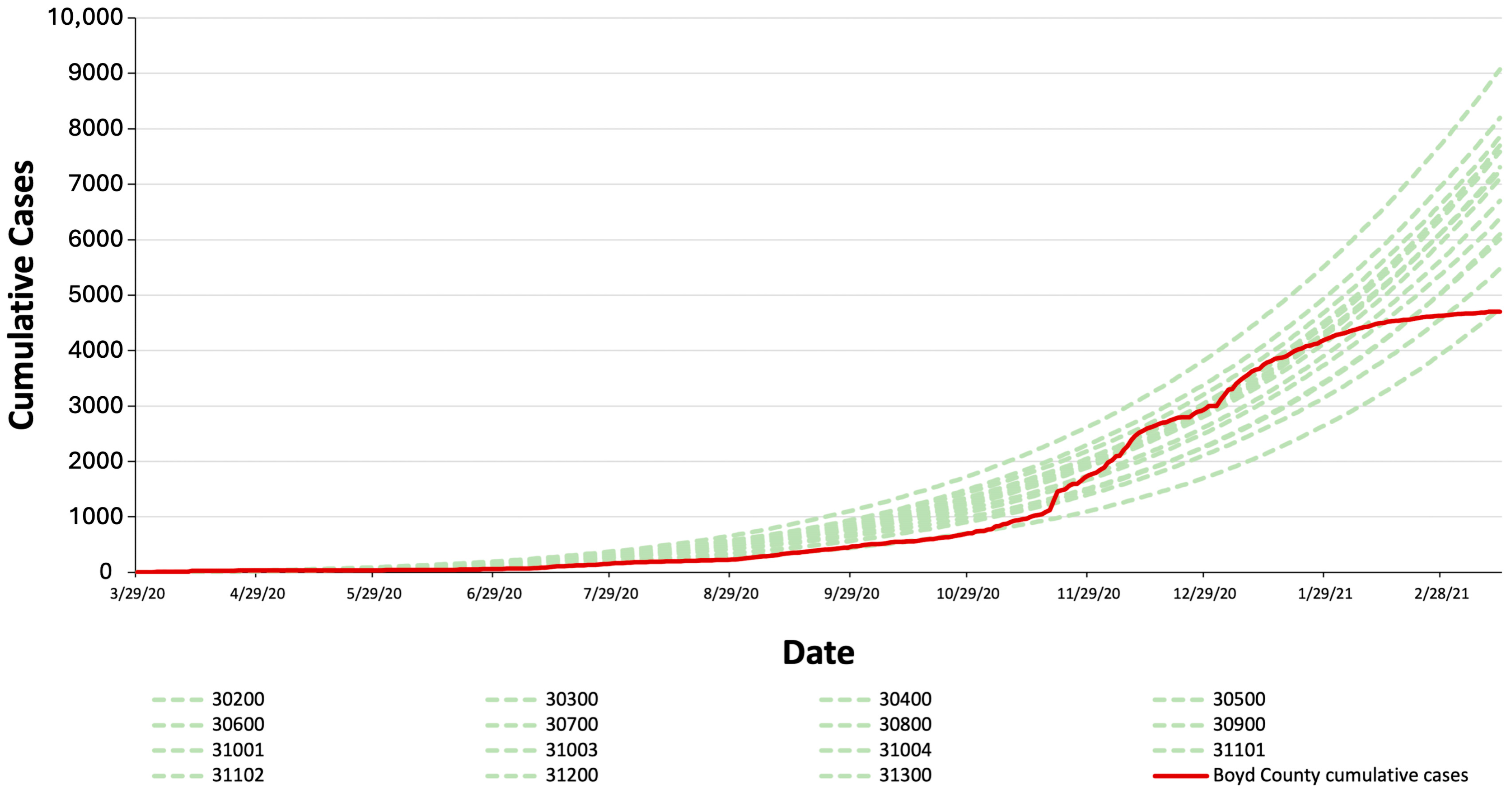

2.1.7. Model Verification and Validation

| Type | Name | Value for Model Validation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset | Census tract boundary data set | version 2021-22 | [27] |

| Dataset | Population data | released 2021 | [29] |

| Dataset | County sewage infrastructure GIS data | ||

| Parameter | Sewage service coverage in the partially sewered tracts | 80% | [22] |

| Parameter | Incubation period | 6 days ±1 day | [45] |

| Parameter | Disease Period | 10 days ± 2 days | [46] |

| Parameter | Infectious period | 2 days + disease period | [37] |

| Parameter | Quarantine rate | 33% | [44,47] |

| Parameter | Mortality | 0.9% (as of 29 April 2023) | [48] |

| Parameter | Family contacts | 1–6 contacts | Calculated based on population data |

| Parameter | School contacts | 10–25 contacts | Calculated based on population data |

| Parameter | Workplace contacts | up to 13 contacts | [31,33] |

| Parameter | Community contacts | up to 13 contacts | [31,33] |

| Parameter | % travelers within sewered or non-sewered zones | 25% | [30] |

| Parameter | Virus-shedding period | 21 days | [49] |

| Parameter | Virus load | 107.6 copies/mL | [50] |

| Parameter | Feces | 318 mL/day | [51,52] |

| Parameter | Percentage of infectious individuals shedding viruses | 43% | [53] |

| Parameter | Wastewater Production | 19,043,452,054 mL/day | Measured at the target wastewater treatment plant |

| Variable | Family transmission rate | 4% | Calibrated against the county data |

| Variable | School transmission rate | 0% | School closure |

| Variable | Workplace transmission rate | 2% (weekdays); 0% (weekends) | Calibrated against the county data |

| Variable | Community transmission rate | 1.1% (weekdays); 1.2% (weekends) | Calibrated against the county data |

| Variable | %-travelers-across (between sewered and non-sewered zones) | 5% (weekdays); 10% (weekends) | Calibrated against the county data |

| Variable | Vaccination rate | 0% | No vaccine available during the simulated time range |

2.2. Scenarios Settings and Testing Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

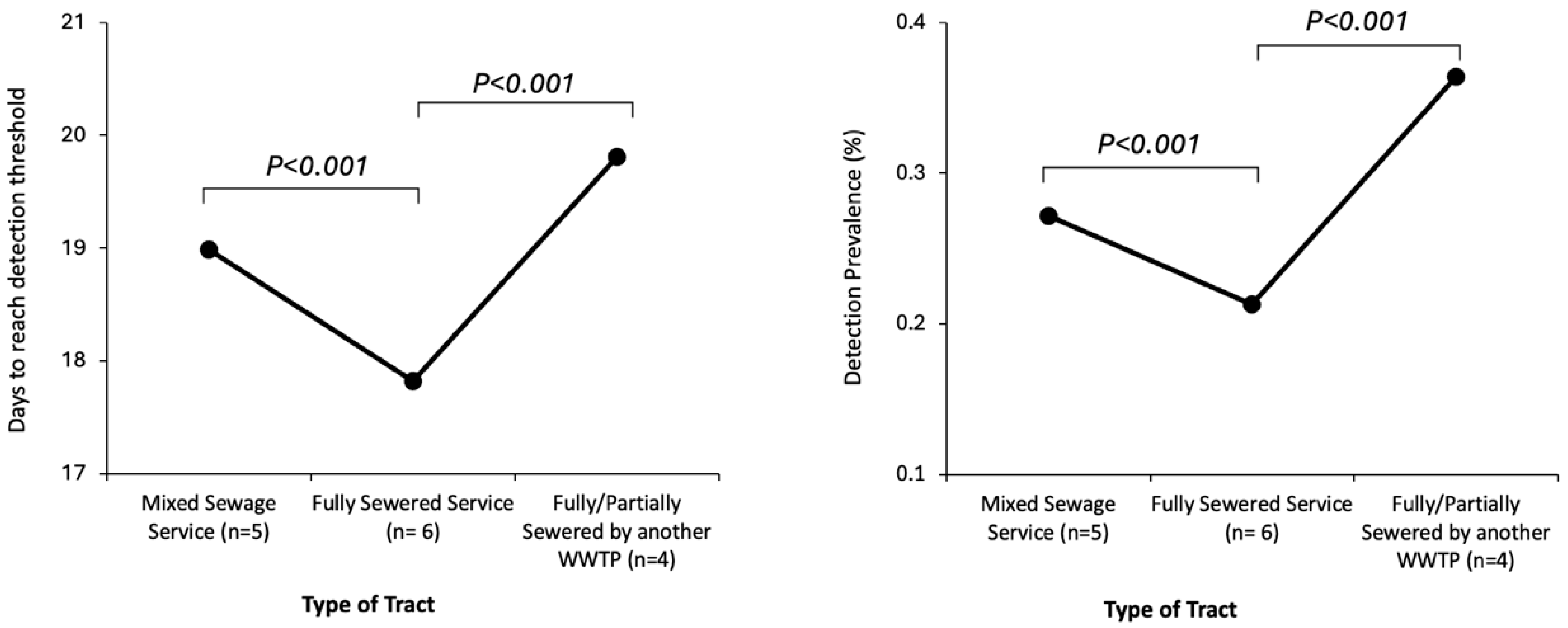

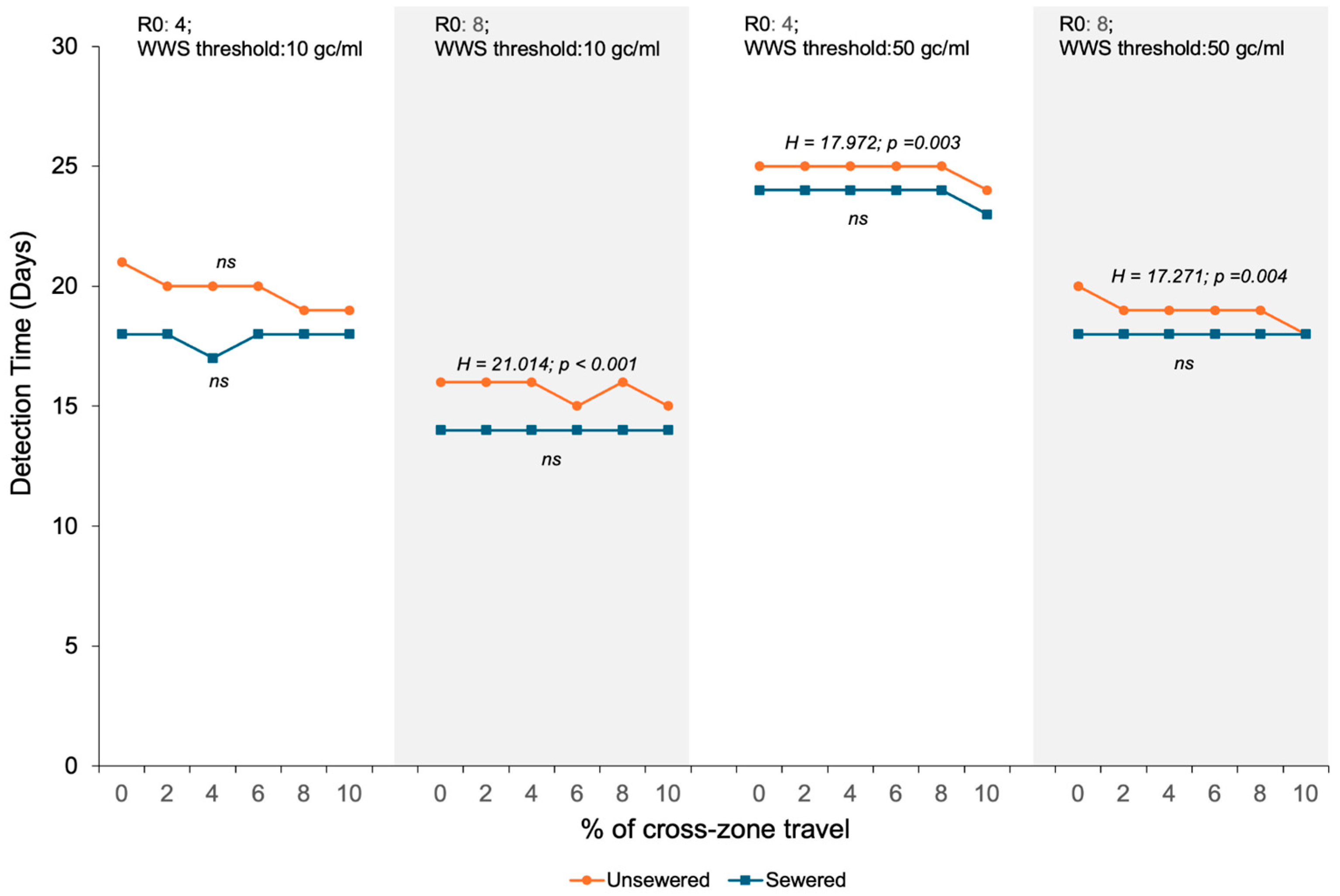

3.1. Impacts of WBE Detection Sensitivity, Sewage Service Status of the First SARS-CoV-2 Carrier, and Cross-Zone Travel Rate on the Number of Days Required for the Viral Concentration in the Aggregated Wastewater to Reach the WBE Detection Threshold

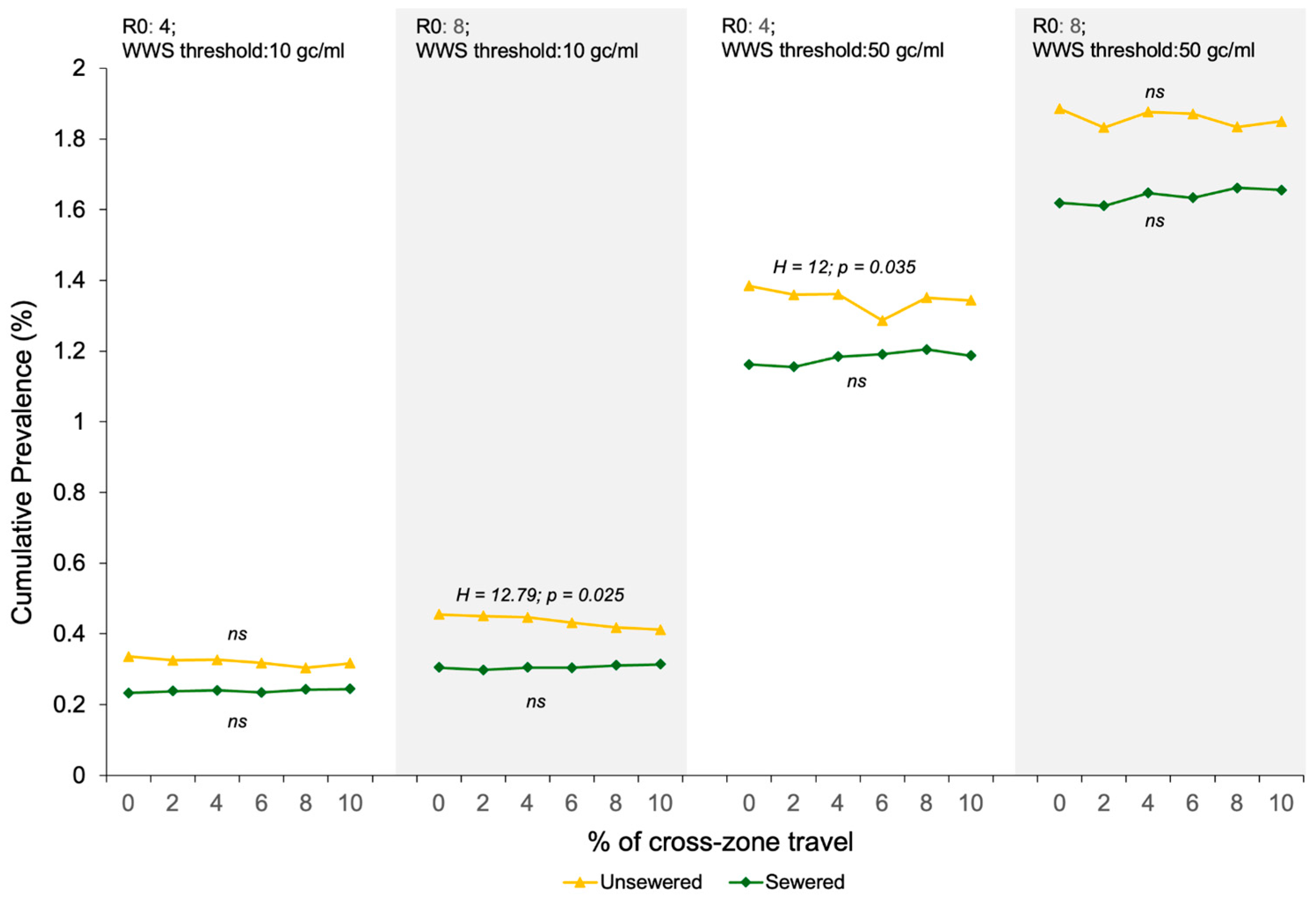

3.2. Impacts of the WBE Detection Sensitivity, Sewage Service Status of the First SARS-CoV-2 Carrier, and Cross-Zone Travel Rate on the COVID-19 Prevalence When the Viral Concentration in the Pooled Wastewater Reaches the WBE Threshold

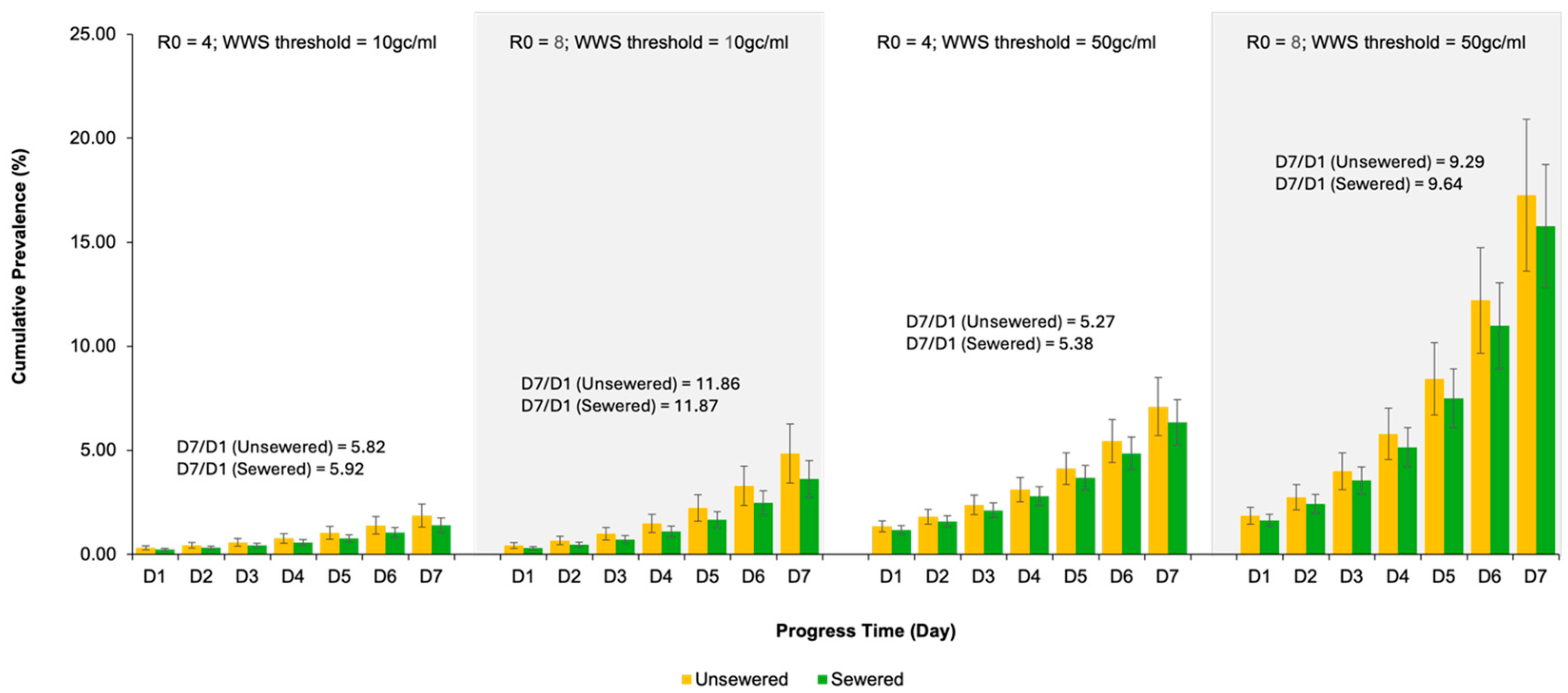

3.3. COVID-19 Prevalence Trend over the Seven Days After the Wastewater Surveillance Threshold Is Reached in the Simulated County

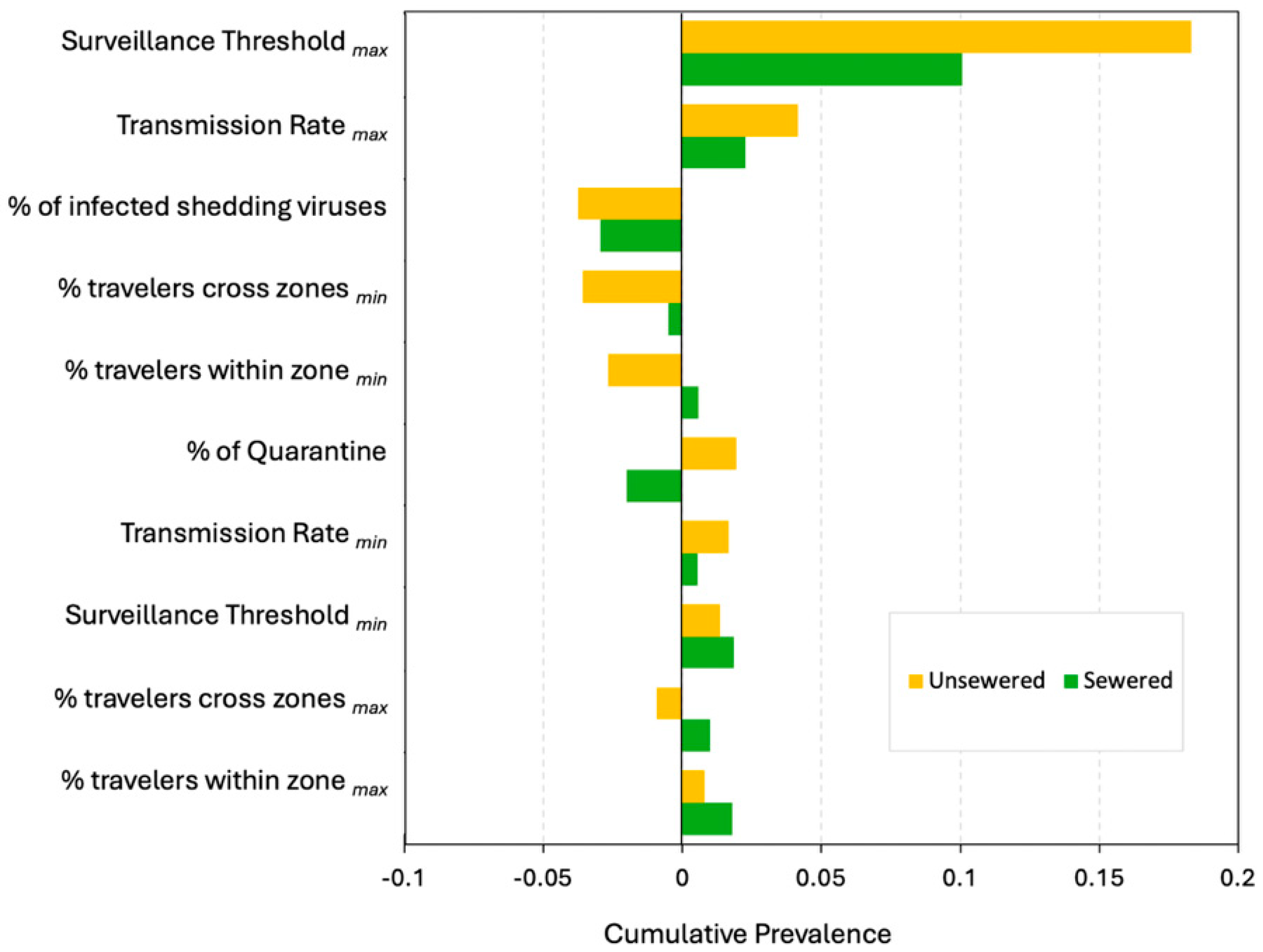

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Fixed | Local SA | Global SA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission Rate (Community) | 2.5% (weekdays & weekend) | 2.4%, 2.5%, 2.6% (weekdays & weekend) | 2.5%; 5% |

| 4.8%, 5%, 5.3% (weekdays & weekend) | |||

| Transmission Rate (Family) | 10% (weekdays & weekend) | 9.6%, 10%, 10.4% (weekdays & weekend) | 5%; 20% |

| 19.2%, 20%, 21.2% (weekdays & weekend) | |||

| Transmission Rate (School) | 5% (weekdays), 0% (weekend) | 4.8%, 5%, 5.2% (weekdays), 0% (weekend) | 5%;10% |

| 9.6%, 10%, 10.4% (weekdays & weekend) | |||

| Transmission Rate (workplace) | 5% (weekdays), 0% (weekend) | 4.8%, 5%, 5.2% (weekdays), 0% (weekend) | 5%, 10% |

| 9.6%, 10%, 10.4% (weekdays & weekend) | |||

| % travelers across zone | 10% | Min: 0%, 0.5%, 1% | 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, 10% |

| Max: 9.5%, 10%, 10.5% | |||

| % travelers within zone | 25% | Min: 0%, 0.5%, 1% | 25% |

| Max: 23.75%, 25%, 26.25% | |||

| Quarantine rate | 33% | 31.35%, 33%, 34.65% | 33% |

| % of infected shedding virus | 43% | 40.85%, 43%, 45.15% | 43% |

| Viral RNA wastewater detection threshold | ≥10 gc/mL | Lower bound: ≥9.5 gc/mL, 10 gc/mL, 10.5 gc/mL | ≥10 gc/mL; ≥50 gc/mL |

| Upper bound: ≥47.5 gc/mL, 50 gc/mL, 52.5 gc/mL |

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Days to Reach the Detection Threshold | Cumulative Prevalence When Threshold Is Reached | |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Rate (TR) | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sewage service status (SSS) | ✓ | ✓ |

| % travelers across zone (T-across) | ✓ | – |

| Surveillance Threshold (ST) | ✓ | ✓ |

| TR × SSS | ✓ | ✓ |

| TR × % T-across | – | – |

| TR × ST | ✓ | ✓ |

| SSS × T-across | ✓ | ✓ |

| SSS × ST | ✓ | ✓ |

| T-across × ST | – | – |

| TR × SSS × T-across | – | – |

| TR × SSS × ST | – | – |

| SSS × T-across × ST | – | – |

| TR × ST × T-across | – | – |

| TR × SSS × T-across × ST | – | – |

| R squared | 0.572 | 0.885 |

References

- Kilaru, P.; Hill, D.; Anderson, K.; Collins, M.B.; Green, H.; Kmush, B.L.; Larsen, D.A. Wastewater surveillance for infectious disease: A systematic review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 192, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.A.; Green, H.; Collins, M.B.; Kmush, B.L. Wastewater monitoring, surveillance and epidemiology: A review of terminology for a common understanding. FEMS Microbes 2021, 2, xtab011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Gwee, S.X.W.; Ng, J.Q.X.; Lau, N.; Koh, J.; Pang, J. Wastewater surveillance to infer COVID-19 transmission: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic—And How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World; Riverhead Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, R.G.; Choi, C.Y.; Riley, M.R.; Gerba, C.P. Pathogen surveillance through monitoring of sewer systems. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 65, 249. [Google Scholar]

- Asghar, H.; Diop, O.M.; Weldegebriel, G.; Malik, F.; Shetty, S.; El Bassioni, L.; Akande, A.O.; Al Maamoun, E.; Zaidi, S.; Adeniji, A.J.; et al. Environmental surveillance for polioviruses in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, S294–S303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, J.; Guo, L.; Yao, H.; Wang, L.; Xia, X.; Zhang, W. Fecal viral shedding in COVID-19 patients: Clinical significance, viral load dynamics and survival analysis. Virus Res. 2020, 289, 198147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Bertsch, P.M.; Bibby, K.; Haramoto, E.; Hewitt, J.; Huygens, F.; Gyawali, P.; Korajkic, A.; Riddell, S.; Sherchan, S.P.; et al. Decay of SARS-CoV-2 and surrogate murine hepatitis virus RNA in untreated wastewater to inform application in wastewater-based epidemiology. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peccia, J.; Zulli, A.; Brackney, D.E.; Grubaugh, N.D.; Kaplan, E.H.; Casanovas-Massana, A.; Ko, A.I.; Malik, A.A.; Wang, D.; Wang, M.; et al. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1164–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, D.A.; Wigginton, K.R. Tracking COVID-19 with wastewater. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1151–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Vikesland, P.; Pruden, A.; Krometis, L.-A.; Lee, L.M.; Darling, A.; Yancey, M.; Helmick, M.; Singh, R.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Making waves: The benefits and challenges of responsibly implementing wastewater-based surveillance for rural communities. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakariya, M.; Ahmed, F.; Islam, M.A.; Al Marzan, A.; Hasan, M.N.; Hossain, M.; Ahmed, T.; Hossain, A.; Reza, H.M.; Hossen, F.; et al. Wastewater-based epidemiological surveillance to monitor the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in developing countries with onsite sanitation facilities. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 311, 119679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S. A review of agent-based model simulation for COVID–19 spread. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Intelligent Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 585–602. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, E.; Kelleher, J.D. Validating and Testing an Agent-Based Model for the Spread of COVID-19 in Ireland. Algorithms 2022, 15, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, F.; Johansson, E.; Davidsson, P. Agent-based social simulation of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. JASSS J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2021, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hsu, S.-C.; Du, E.; Song, L.; Lam, C.M.; Liu, X.; Zheng, C. Agent-Based Modeling in Water Science: From Macroscale to Microscale. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 1206–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, A.; Majed, N.; Bucci, V.; Hellweger, F.; Tu, Y.; Gu, A. Is the whole the sum of its parts? Agent-based modelling of wastewater treatment systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 63, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazli, M.; Sklar, S.; Porter, M.D.; French, B.A.; Shakeri, H. Wastewater-based epidemiological modeling for continuous surveillance of COVID–19 outbreak. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–18 December 2021; pp. 4342–4349. [Google Scholar]

- DelaPaz-Ruíz, N.; Augustijn, P.; Farnaghi, M.; Abdulkareem, S.A.; Zurita-Milla, R. Integrating agent-based disease, mobility and wastewater models for the study of the spread of communicable diseases. Geospat. Health 2025, 20, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicker, J.; Tomza, N.; Wallrafen-Sam, K.; Schmid, N.; Hofmann, A.F.; Korf, S.; Schengen, A.; Javanmardi, J.; Wieser, A.; Kühn, M.J. Coupled Epidemiological and Wastewater Modeling at the Urban Scale: A Case Study for Munich. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, N.; Bicker, J.; Hofmann, A.F.; Wallrafen-Sam, K.; Kerkmann, D.; Wieser, A.; Kühn, M.J.; Hasenauer, J. Integrative modeling of the spread of serious infectious diseases and corresponding wastewater dynamics. Epidemics 2025, 51, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. About Septic Systems. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/septic/about-septic-systems (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Hewitt, J.; Trowsdale, S.; Armstrong, B.A.; Chapman, J.R.; Carter, K.M.; Croucher, D.M.; Trent, C.R.; Sim, R.E.; Gilpin, B.J. Sensitivity of wastewater-based epidemiology for detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a low prevalence setting. Water Res. 2022, 211, 118032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilensky, U. Center for connected learning and computer-based modeling. In NetLogo; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pilny, A.; Xiang, L.; Huber, C.; Silberman, W.; Goatley-Soan, S. The impact of contact tracing on the spread of COVID-19: An egocentric agent-based model. Connections 2021, 41, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, V.; Railsback, S.F.; Vincenot, C.E.; Berger, U.; Gallagher, C.; DeAngelis, D.L.; Edmonds, B.; Ge, J.; Giske, J.; Groeneveld, J.; et al. The ODD protocol for describing agent-based and other simulation models: A second update to improve clarity, replication, and structural realism. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2020, 23, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. Cartographic Boundary Files. Available online: https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/2024-cartographic-boundary-file-shp-census-tract-for-united-states-1-5000000 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- QGIS.org. QGIS Geographic Information System; QGIS.org: Grüt, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Explore Census Data. Available online: https://www.usa.gov/agencies/u-s-census-bureau (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Google. Community Mobility Reports; Google: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, S.Y.; Hyman, J.M.; Hethcote, H.W.; Eubank, S.G. Mixing patterns between age groups in social networks. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossong, J.; Hens, N.; Jit, M.; Beutels, P.; Auranen, K.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Massari, M.; Salmaso, S.; Tomba, G.S.; Wallinga, J.; et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothwell, J. Americans’ Social Contacts During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/308444/americans-social-contacts-during-covid-pandemic.aspx (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Phan, T.; Brozak, S.; Pell, B.; Gitter, A.; Xiao, A.; Mena, K.D.; Kuang, Y.; Wu, F. A simple SEIR-V model to estimate COVID-19 prevalence and predict SARS-CoV-2 transmission using wastewater-based surveillance data. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, C.S.; Self, S.; Rennert, L.; Kalbaugh, C.; Kriebel, D.; Graves, D.; Colby, C.; Deaver, J.A.; Popat, S.C.; Karanfil, T.; et al. COVID-19 wastewater epidemiology: A model to estimate infected populations. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e874–e881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, D.; Kemp, F.; Magni, S.; Ogorzaly, L.; Cauchie, H.-M.; Gonçalves, J.; Skupin, A.; Aalto, A. Model-based assessment of COVID-19 epidemic dynamics by wastewater analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 827, 154235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): How Is It Transmitted? Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Jones, J.H. Notes on R0; Department of Anthropological Sciences, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2007; Volume 323, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Alimohamadi, Y.; Taghdir, M.; Sepandi, M. Estimate of the basic reproduction number for COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2020, 53, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rocklöv, J. The reproductive number of the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 is far higher compared to the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 virus. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28, taab124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rocklöv, J. The effective reproductive number of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 is several times relative to Delta. J. Travel Med. 2022, 29, taac037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilensky, U.; Rand, W. An Introduction to Agent-Based Modeling: Modeling Natural, Social, and Engineered Complex Systems with NetLogo; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, E.; Kelleher, J.D. Understanding the assumptions of an SEIR compartmental model using agentization and a complexity hierarchy. J. Comput. Math. Data Sci. 2022, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, R.E.; Deng, Y.; Deng, X.; Lee, A.; Meyer, W.A.; Letovsky, S.; Charles, M.D.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; MacNeil, A.; Hall, A.J. Estimated SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence trends and relationship to reported case prevalence from a repeated, cross-sectional study in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, United States—October 25, 2020–February 26, 2022. Lancet Reg. Health–Am. 2023, 18, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, C.; Sekri, A.; Leblanc, P.; Cucherat, M.; Vanhems, P. The incubation period of COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 708–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Bergeri, I.; Whelan, M.G.; Ware, H.; Subissi, L.; Nardone, A.; Lewis, H.C.; Li, Z.; Ma, X.; Valenciano, M.; Cheng, B. Global SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence from January 2020 to April 2022: A systematic review and meta-analysis of standardized population-based studies. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Center. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Jones, D.L.; Baluja, M.Q.; Graham, D.W.; Corbishley, A.; McDonald, J.E.; Malham, S.K.; Hillary, L.S.; Connor, T.R.; Gaze, W.H.; Moura, I.B. Shedding of SARS-CoV-2 in feces and urine and its potential role in person-to-person transmission and the environment-based spread of COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foladori, P.; Cutrupi, F.; Segata, N.; Manara, S.; Pinto, F.; Malpei, F.; Bruni, L.; La Rosa, G. SARS-CoV-2 from faeces to wastewater treatment: What do we know? A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. NASA-STD-3001 Technical Brief: Body Waster Management: NASA Office of the Chief Health & Medical Officer (OCHMO). Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/ochmo/hsa-standards/ochmo-technical-briefs/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Penn, R.; Ward, B.J.; Strande, L.; Maurer, M. Review of synthetic human faeces and faecal sludge for sanitation and wastewater research. Water Res. 2018, 132, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, A.; Zlitni, S.; Brooks, E.F.; Vance, S.E.; Dahlen, A.; Hedlin, H.; Park, R.M.; Han, A.; Schmidtke, D.T.; Verma, R. Gastrointestinal symptoms and fecal shedding of SARS-CoV-2 RNA suggest prolonged gastrointestinal infection. Med 2022, 3, 371–387.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Broeke, G.; Van Voorn, G.; Ligtenberg, A. Which sensitivity analysis method should I use for my agent-based model? J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2016, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Railsback, S.F.; Grimm, V. Agent-Based and Individual-Based Modeling: A Practical Introduction; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Borgonovo, E.; Pangallo, M.; Rivkin, J.; Rizzo, L.; Siggelkow, N. Sensitivity analysis of agent-based models: A new protocol. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 2022, 28, 52–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, V.W.; Zhou, Y. Kolmogorov–smirnov test: Overview. In Wiley Statsref: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureton, E.E. Rank-biserial correlation. Psychometrika 1956, 21, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, T.R.; Hullett, C.R. Eta squared, partial eta squared, and misreporting of effect size in communication research. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, O.E.; Halden, R.U. Computational analysis of SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 surveillance by wastewater-based epidemiology locally and globally: Feasibility, economy, opportunities and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 138875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wannigama, D.L.; Amarasiri, M.; Hongsing, P.; Hurst, C.; Modchang, C.; Chadsuthi, S.; Anupong, S.; Phattharapornjaroen, P.; SM, A.H.R.; Fernandez, S.; et al. COVID-19 monitoring with sparse sampling of sewered and non-sewered wastewater in urban and rural communities. iScience 2023, 26, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocock, G. Application of wastewater-based surveillance to monitor SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in South African communities. Water Res. Comm. Pretoria. WRC Rep. No. TT 2020, 832, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Puthussery, J.V.; Ghumra, D.P.; McBrearty, K.R.; Doherty, B.M.; Sumlin, B.J.; Sarabandi, A.; Mandal, A.G.; Shetty, N.J.; Gardiner, W.D.; Magrecki, J.P.; et al. Real-time environmental surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 aerosols. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullano, G.; Valdano, E.; Scarpa, N.; Rubrichi, S.; Colizza, V. Evaluating the effect of demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, and risk aversion on mobility during the COVID-19 epidemic in France under lockdown: A population-based study. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e638–e649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, E.T.; Barros, P.H.; Cardoso-Pereira, I.; Ponte, I.V.; Ximenes, P.; Figueiredo, F.; Murai, F.; Couto da Silva, A.P.; Almeida, J.M.; Loureiro, A.A.; et al. Effects of population mobility on the COVID-19 spread in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crank, K.; Chen, W.; Bivins, A.; Lowry, S.; Bibby, K. Contribution of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding routes to RNA loads in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kulandaivelu, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Shi, J.; O’Brien, J.; Arora, S.; Kumar, M.; Sherchan, S.P.; Honda, R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 shedding sources in wastewater and implications for wastewater-based epidemiology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432, 128667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | Variable Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Location | tt-tract-ID | Human tract ID |

| home-x, home-y | Human home coordinates | |

| Sewered? | Human home sewage service status (True/False) | |

| Disease Transmission | States of disease | susceptible, exposed (presymptomatic), infectious (symptomatic), recovered |

| Measures | vaccinated, quarantine | |

| Shed-pathogens? | Does the person shed viruses? | |

| Infected-by-me | The number of people the agent has infected | |

| Infect-any? | Has the agent infected any people? (True/False) | |

| Social Network | Household-id | Household ID used to set up the family network |

| Age | Age in years | |

| School? | Does the person attend a school? (True/False) | |

| class-ID | A school attendee’s class ID | |

| Work? | Does the person work? (True/False) | |

| Family-contact | A person’s contacts at home | |

| School-contact | A school attendee’s contacts at school | |

| Work-contact | A worker’s contacts at the workplace | |

| Non-community-contact | A person’s combined contacts at home, school, and workplace. |

| Variable | R0 = 4 | R0 = 8 |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Rate (Community) | 2.5% (weekdays & weekend) | 5% (weekdays & weekend) |

| Transmission Rate (Family) | 10% (weekdays & weekend) | 20% (weekdays & weekend) |

| Transmission Rate (School) | 5% (weekdays), 0% (weekend) | 10% (weekdays), 0% (weekend) |

| Transmission Rate (workplace) | 5% (weekdays), 0% (weekend) | 10% (weekdays), 0% (weekend) |

| Effective contacts (Community) | up to 13 | up to 13 |

| Effective contacts (Family) | 1~6 | 1~6 |

| Effective contacts (School) | 10~24 | 10~24 |

| Effective contacts (workplace) | up to 13 | up to 13 |

| % travelers across zone | 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, 10% | 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, 10% |

| % travelers within zone | 25% | 25% |

| Vaccination rate | 0% | 0% |

| Quarantine rate | 33% | 33% |

| Mean of Incubation period | 6 days ±1 | 6 days ± 1 |

| Mean of disease period | 10 days±2 | 10 days ± 2 |

| % of infected shedding virus | 43% | 43% |

| SARS-CoV-2 viral load per person per day | 11,267,184,072 copies/day | 11,267,184,072 copies/day |

| Viral RNA wastewater detection threshold | ≥10 gc/mL, ≥50 gc/mL | ≥10 gc/mL, ≥50 gc/mL |

| R0 | Sewer Service | Days | Mann–Whitney U | Effect Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBE Threshold = 10 gc/mL | WBE Threshold = 50 gc/mL | |||||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Z | p | r | ||

| 4 | Non-sewered | 20 (18–22) | 25 (23–27) | 25.499 | <0.001 | 0.60 |

| Sewered | 18 (16–20) | 24 (22–25) | 29.942 | <0.001 | 0.71 | |

| 8 | Non-sewered | 16 (14–18) | 19 (18–21) | 24.676 | <0.001 | 0.58 |

| Sewered | 14 (13–16) | 18 (17–19) | 30.432 | <0.001 | 0.72 | |

| R0 | Sewer Service | Cumulative Prevalence | Mann–Whitney U | Effect Size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBE Threshold = 10 gc/mL | WBE Threshold = 50 gc/mL | |||||||

| M ± SD | # of Infection | M ± SD | # of Infections | Z | p | r | ||

| 4 | Non-sewered | 0.32% ± 0.10% | 155 ± 48 | 1.35% ± 0.27% | 653 ± 129 | 36.59 | <0.001 | 0.87 |

| Sewered | 0.24% ± 0.05% | 115 ± 27 | 1.18% ± 0.21% | 572 ± 100 | 36.712 | <0.001 | 0.87 | |

| 8 | Non-sewered | 0.44% ± 0.14% | 211 ± 69 | 1.86% ± 0.41% | 900 ± 197 | 36.697 | <0.001 | 0.87 |

| Sewered | 0.31% ± 0.07% | 148 ± 36 | 1.64% ± 0.30% | 794 ± 144 | 36.732 | <0.001 | 0.87 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiang, L.; Keck, J.W.; Gallimore, J.; Sakhaei, A.; Loh, E.; Berry, S.M. Wastewater Infrastructure as a Public Health Tool: Agent-Based Modeling of Surveillance Strategies in a COVID-19 Context. Systems 2025, 13, 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121093

Xiang L, Keck JW, Gallimore J, Sakhaei A, Loh E, Berry SM. Wastewater Infrastructure as a Public Health Tool: Agent-Based Modeling of Surveillance Strategies in a COVID-19 Context. Systems. 2025; 13(12):1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121093

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiang, Lin, James W. Keck, James Gallimore, Amirmohammad Sakhaei, Elizabeth Loh, and Scott M. Berry. 2025. "Wastewater Infrastructure as a Public Health Tool: Agent-Based Modeling of Surveillance Strategies in a COVID-19 Context" Systems 13, no. 12: 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121093

APA StyleXiang, L., Keck, J. W., Gallimore, J., Sakhaei, A., Loh, E., & Berry, S. M. (2025). Wastewater Infrastructure as a Public Health Tool: Agent-Based Modeling of Surveillance Strategies in a COVID-19 Context. Systems, 13(12), 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121093