How Does Smart Logistics Influence Enterprise Innovation? Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Hypothesis

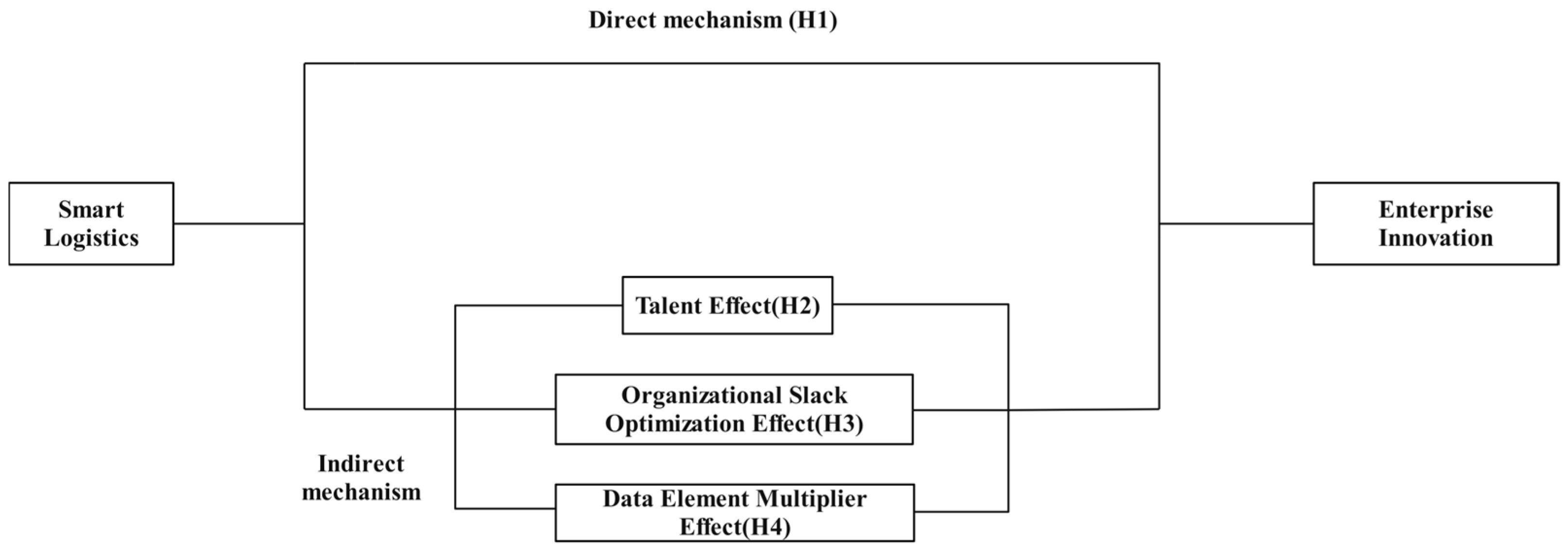

3.1. Smart Logistics and Enterprise Innovation

3.2. Smart Logistics, Talent Effect, and Enterprise Innovation

3.3. Smart Logistics, Organizational Slack Optimization Effect, and Enterprise Innovation

3.4. Smart Logistics, the Data Element Multiplier Effect, and Enterprise Innovation

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Sources and Samples

4.2. Variable Definitions

4.2.1. Dependent Variable: Enterprise Innovation (Innov)

4.2.2. Independent Variable: Smart Logistics (SL)

4.2.3. Control Variables

4.3. Model Specification

4.3.1. Main Effect (H1)

4.3.2. Mechanism Analysis (H2, 3 and 4)

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

5.2. Baseline Regression Results

5.3. Endogeneity Test

5.4. Robustness Tests

5.4.1. Replace the Dependent Variable

5.4.2. Change the Level of Clustering

5.4.3. Change Estimation Method

5.4.4. Restricted Firm Sample Estimation

5.4.5. Excluding Policy Effects

6. Analysis of Mechanisms and Heterogeneity

6.1. Mechanism Analysis

6.1.1. The Talent Effect Mechanism

6.1.2. The Organizational Slack Optimization Effect

6.1.3. The Data Element Multiplier Effect

6.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

6.2.1. Level of Industry Competition

6.2.2. Information Transparency

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | (1) Innov | (2) Innov | (3) Innov | (4) Innov | (5) Innov | (6) Innov | (7) Innov | (8) Innov | (9) Innov | (1) Innov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL | 0.028 (0.020) | 0.023 (0.021) | 0.038 * (0.020) | 0.039 * (0.020) | 0.039 * (0.020) | 0.040 ** (0.020) | 0.041 ** (0.020) | 0.042 ** (0.020) | 0.053 ** (0.021) | 0.055 *** (0.020) |

| Control | −0.038 (0.212) | −0.051 (0.164) | −0.050 (0.164) | −0.050 (0.164) | −0.052 (0.164) | −0.052 (0.164) | −0.051 (0.166) | −0.050 (0.166) | −0.038 (0.168) | |

| Tax | 0.059 *** (0.011) | 0.061 *** (0.011) | 0.061 *** (0.011) | 0.059 *** (0.011) | 0.055 *** (0.012) | 0.051 *** (0.011) | 0.052 *** (0.012) | 0.060 *** (0.012) | ||

| Property | 0.154 * (0.082) | 0.156 * (0.084) | 0.202 ** (0.084) | 0.203 ** (0.084) | 0.205 ** (0.083) | 0.207 ** (0.086) | 0.231 ** (0.102) | |||

| Duality | 0.012 (0.036) | 0.013 (0.036) | 0.011 (0.036) | 0.014 (0.037) | 0.006 (0.040) | 0.013 (0.040) | ||||

| Shareholding | 0.005 *** (0.002) | 0.005 *** (0.002) | 0.005 *** (0.002) | 0.005 ** (0.002) | 0.004 * (0.002) | |||||

| Salary | 0.050 * (0.026) | 0.043 (0.026) | 0.053 ** (0.024) | 0.057 ** (0.025) | ||||||

| Market | 0.015 * (0.008) | 0.017 * (0.008) | 0.014 * (0.008) | |||||||

| FDI2 | 0.002 (0.005) | −0.000 (0.006) | ||||||||

| EduExpend | −0.016 (0.106) | |||||||||

| _cons | 2.525 *** (0.011) | 2.596 *** (0.210) | 1.588 *** (0.221) | 1.516 *** (0.217) | 1.514 *** (0.216) | 1.432 *** (0.207) | 0.7214 * (0.4319) | 0.871 * (0.438) | 0.676 (0.408) | 0.656 (1.207) |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 13,913 | 12,802 | 12,238 | 12,238 | 12,238 | 12,238 | 12,224 | 12,223 | 11,446 | 10,080 |

| R2 | 0.836 | 0.841 | 0.846 | 0.846 | 0.846 | 0.846 | 0.847 | 0.847 | 0.845 | 0.852 |

| adj. R2 | 0.807 | 0.813 | 0.818 | 0.818 | 0.818 | 0.818 | 0.818 | 0.818 | 0.816 | 0.823 |

References

- Cefis, E.; Marsili, O. Survivor: The role of innovation in firms’ survival. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, N.C.; Marcon, A.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Olteanu, Y.; Fichter, K. The role of cooperation and technological orientation on startups’ innovativeness: An analysis based on the microfoundations of innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 192, 122604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xu, Y.; Gao, P. Leveraging Big Data Analytics Capability for Firm Innovativeness: The Role of Sustained Innovation and Organizational Slack. Systems 2025, 13, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchuk, V.; Comi, A.; Weiß, C.; Svatko, V. The optimization of cargo delivery processes with dynamic route updates in smart logistics. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2023, 2, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Mai, J.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, M.; Wang, K. Concept and key technologies of intelligent logistics. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1646, 012092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yu, F.R.; Zhou, L.; Yang, X.; He, Z. Applications of the Internet of Things (IoT) in smart logistics: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 4250–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chang, H.; Forrest, J.Y.-L.; Yang, B. Influence of artificial intelligence on technological innovation: Evidence from the panel data of China’s manufacturing sectors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 158, 120142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, C.; Lagorio, A.; Romero, D.; Cavalieri, S.; Stahre, J. Smart logistics and the logistics operator 4.0. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 10615–10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowery, D.; Rosenberg, N. The influence of market demand upon innovation: A critical review of some recent empirical studies. Res. Policy 1979, 8, 102–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisławski, R.; Szymonik, A. Impact of selected intelligent systems in logistics on the creation of a sustainable market position of manufacturing companies in Poland in the context of Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ietto-Gillies, G. Innovation, internationalization, and the transnational corporation. In The Handbook of Global Science, Technology, and Innovation; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, J. Evaluation of the Smart Logistics Based on the SLDI Model: Evidence from China. Systems 2024, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Ni, S.; Ding, T. Research on collaborative innovation evaluation of intelligent logistics park. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 4048–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Dong, D.; Wang, J. Evaluation of the intelligent logistics eco-index: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 123127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z. Research on the influence of supply chain stability on the innovation ability of enterprises. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2025, 2, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yuan, S.; Ostic, D.; Pan, L. Supply chain finance and innovation efficiency: An empirical analysis based on manufacturing SMEs. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Liu, J.; Tao, C. Market access, supply chain resilience and enterprise innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P. Logistics service standardization and corporate innovation: Evidence from a natural experiment. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 77, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Rahman, M.M.; Siddik, A.B.; Wen, Z.G.; Sobhani, F.A. Exploring the synergy of logistics, finance, and technology on innovation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabadurmuş, F.N.K. The relationship between logistics performance and innovation: An empirical study of Turkish Firms. Alphanumeric J. 2019, 7, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Mansor, Z.D.; Leong, Y.C. Linking digital leadership and employee digital performance in SMEs in China: The chain-mediating role of high-involvement human resource management practice and employee dynamic capability. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Ye, Q. Operations management of smart logistics: A literature review and future research. Front. Eng. Manag. 2021, 8, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshdadi, A.A.; Irshad, A. PDAC-SL: A PUF-enabled drone access control technique for smart logistics. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 107, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Asis, E.; Bhanot, A.; Jagota, V.; Chandra, B.; Hossain, M.S.; Pant, K.; Almashaqbeh, H.A. Smart Logistic System for Enhancing the Farmer-Customer Corridor in Smart Agriculture Sector Using Artificial Intelligence. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 7486974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, J.; Liang, J.; Liang, R. Research on the impact of smart logistics on the the manufacturing industry chain resilience. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shee, H.K.; Miah, S.J.; De Vass, T. Impact of smart logistics on smart city sustainable performance: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 821–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, A.; Cai, J.; Yang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Li, X. The Impact of Intelligent Logistics on Logistics Performance Improvement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soledispa-Canarte, B.; Pibaque-Pionce, M.; Merchan-Ponce, N.; Mex Alvarez, D.; Tovar-Quintero, J.; Escobar-Molina, D.; Cedeno-Ramirez, J.; Rincon-Guio, C. The role of logistics 4.0 in agribusiness sustainability and competitiveness, a bibliometric and systematic literature review. Oper. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 16, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, K. Barriers to innovative activity of enterprises in the sustain development in times of crisis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 3140–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biais, B.; Rochet, J.-C.; Woolley, P. Dynamics of innovation and risk. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 1353–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, J. Human capital and economic growth. Econ. Educ. Rev. 1984, 3, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachuk, A.; Linder, N. Knowledge spillover effects: Impact of export learning effects on companies’ innovative activities. In Current Issues in Knowledge Management; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zona, F. Corporate investing as a response to economic downturn: Prospect theory, the behavioural agency model and the role of financial slack. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, S42–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.V. Performance, slack, and risk taking in organizational decision making. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 562–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, M.P.; Wolf, G.; Chase, R.B.; Tansik, D.A. Antecedents of organizational slack. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, M.; Pini, P.; Tortia, E. Organizational innovations, human resources and firm performance: The Emilia-Romagna food sector. J. Socio-Econ. 2006, 35, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Data assetization and capital market information efficiency: Evidence from Hidden Champion SMEs in China. Future Bus. J. 2024, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, T.; Kong, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, W. Can data assets promote green innovation in enterprises? Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 72, 106554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, K.; Chiappetta, M.; Artyushina, A. The problem of innovation in technoscientific capitalism: Data rentiership and the policy implications of turning personal digital data into a private asset. Policy Stud. 2020, 41, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liao, G.; Albitar, K. Does corporate environmental responsibility engagement affect firm value? The mediating role of corporate innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Zheng, Y. The impact of chief executive officers’(CEOs’) overseas experience on the corporate innovation performance of enterprises in China. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Anselin, L.; Varga, A. Patents and innovation counts as measures of regional production of new knowledge. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1069–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Ma, G.; Zhu, W. Research on the impact of digital finance on the innovation performance of enterprises. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 804–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cui, Y.; Zheng, Y. The impact of corporate strategy on enterprise innovation based on the mediating effect of corporate risk-taking. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Environmental compliance and enterprise innovation: Empirical evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asunka, B.A.; Ma, Z.; Li, M.; Anaba, O.A.; Amowine, N.; Hu, W. Assessing the asymmetric linkages between foreign direct investments and indigenous innovation in developing countries: A non-linear panel auto-regressive distributed lag approach. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2020, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Li, C.; Qin, Z.; Yu, S.; Pan, Y.; Andrianarimanana, M.H. Impact of fiscal education expenditure on innovation of local listed enterprises: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.H.; Lerner, J.; Wu, C. Intellectual property rights protection, ownership, and innovation: Evidence from China. Rev. Financ. Studies 2017, 30, 2446–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, T.; Zulkafli, A.H. Managerial ownership and corporate innovation: Evidence of patenting activity from Chinese listed manufacturing firms. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2289202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, J. The impact of executive compensation incentive on corporate innovation capability: Evidence from agro-based companies in China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhu, Y. Chair–CEO trust and firm performance. Aust. J. Manag. 2022, 47, 163–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Singh, M.; Žaldokas, A. Do corporate taxes hinder innovation? J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 124, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasnicki, W.; Kwasnicka, H. Market, innovation, competition: An evolutionary model of industrial dynamics. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1992, 19, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Shu, W.; Tang, Q.; Zheng, Y. Internal control and corporate innovation: Evidence from China. Asia-Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2019, 26, 622–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Z.; Forrest, J.Y.-L. Does the smart city policy promote the green growth of the urban economy? Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 66709–66723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, A.C.; Gelbach, J.B.; Miller, D.L. Robust inference with multiway clustering. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2011, 29, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Roth, J. Logs with zeros? Some problems and solutions. Q. J. Econ. 2024, 139, 891–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z. The impact of carbon emission trading policy on enterprise ESG performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, F.-Y.; Jia, S.-Q.; Qiu, L.-R. The relationship between enterprise human capital structure and international M&A performance based on cultural differences in China. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0289270. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Y. The impact of artificial intelligence on enterprises’ new quality productive forces—An analysis of mediation effects based on Technological Innovation Theory. World Surv. Res. 2025, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, L.; Du, Y. Does Data Assetization Alleviate Financing Constraints of SRDI SMEs. China Ind. Econ. 2024, 8, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonehouse, G.; Snowdon, B. Competitive advantage revisited: Michael Porter on strategy and competitiveness. J. Manag. Inq. 2007, 16, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczak, J.; Kijewska, K. Smart Logistics in the development of Smart Cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 39, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, X.; Tamamine, T. Digital transformation in supply chains: Assessing the spillover effects on midstream firm innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hill, A.; Liu, Y.; Hwang, K.S.; Lim, M.K. Supply chain digitalization and agility: How does firm innovation matter in companies? J. Bus. Logist. 2025, 46, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Arikan, A.M. The resource-based view: Origins and implications. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 123–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strategic management journal 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Processes | Lexicon |

|---|---|

| Transportation | Smart Logistics, Intelligent Transportation, Unmanned Transport, Intermodal Transport, Railway Freight Digitalization, Road Freight Digitalization, Virtual Truck Operator, Transport Route Optimization, Vehicle Satellite Positioning, Intelligent Transport Equipment, Intelligent Logistics, Smart Port, Smart Shipping, Smart Railway, Smart Highway, Vehicle-to-Everything, Intelligent Shipping, Intelligent Railway, Intelligent Dispatch, Autonomous Driving, Smart Freight, Transport Digitalization |

| Storage | Intelligent Warehousing, Smart Warehousing, Intelligent Warehouse, Smart Warehouse, Unmanned Warehouse, Automated Storage and Retrieval System, Automated Warehousing, Warehouse Digitalization, Intelligent Sorting, Smart Shelving, Warehouse Robot, Cold Chain Warehousing, Digital Warehouse, Inventory Turnover Optimization, Digital Twin Warehouse, Intelligent Storage Location, Warehouse Automation, Smart Interconnection |

| Packaging | Electronic Shipping Label, Packaging Digitalization, Packaging Robot, Automatic Unpacking, Automatic Stretch Wrapping, Automatic Case Packing, In-line Weighing, Automatic Labeling, Automatic Case Sealing, Automatic Bundling, Smart Returnable Logistics Container |

| Loading and Unloading | Automated Loading and Unloading, Intelligent Loading and Unloading, Intelligent Handling, Palletizing Robot, Automated Sorting, Loading and Unloading Robot, Unmanned Handling, Loading and Unloading Automation |

| Distribution | Intelligent Delivery, Smart Delivery, Delivery Digitalization, Unmanned Delivery, Smart Parcel Locker, Front Warehouse Delivery, Last-mile Facility Digitalization, Intelligent Loading |

| Logistics Information | Logistics Information, Electronic Waybill, Logistics Data, Logistics Tracking, Digitalization of Waybills, Logistics Status Monitoring, Big Data in Logistics |

| Type | Variable | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Enterprise innovation | Innov | Ln(1 + the number of corporate invention patent applications in year + 2) |

| Independent Variable | The level of smart logistics in cities | SL | The index of city-level smart logistics, constructed based on keyword frequency statistics for the current year. |

| Control Variables | City openness level | FDI | Ratio of total urban import and export value to GDP |

| Fiscal education expenditure | EduExpend | Ln(Current-year fiscal education expenditure) | |

| Control Variables | The nature of property rights | Property | State-owned enterprise, yes = 1; no = 0 |

| The proportion of management shareholding | Shareholding | Ratio of shares held by directors, supervisors, and senior management to total outstanding shares in the current year | |

| Remuneration incentives | Salary | Ln(Current-year total annual compensation of directors, supervisors, and senior management) | |

| Dual role of management | Duality | Whether the chairman and the general manager are the same person in the current year, yes = 1; no = 0 | |

| Corporate tax burden | Tax | Ln(Current-year corporate income tax expense) | |

| Market share | Market | Ratio of the corporation’s current-year operating revenue to the aggregate operating revenue of its industry | |

| The effectiveness of internal control | Control | Whether the firm’s internal control is effective in the current year, yes = 1; no = 0 |

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | p50 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innov | 14,145 | 2.531 | 1.623 | 0.000 | 2.485 | 7.179 |

| SL | 14,188 | 0.508 | 0.515 | 0.000 | 0.693 | 1.792 |

| FDI | 13,317 | 5.673 | 4.978 | 0.057 | 4.636 | 20.239 |

| EduExpend | 12,451 | 10.053 | 1.028 | 7.793 | 9.882 | 11.651 |

| Property | 13,626 | 0.303 | 0.460 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Shareholding | 13,626 | 17.000 | 20.719 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 69.028 |

| Salary | 13,608 | 15.797 | 0.693 | 14.225 | 15.759 | 17.776 |

| Duality | 13,626 | 0.321 | 0.467 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Tax | 13,399 | 17.179 | 1.806 | 12.803 | 17.070 | 22.136 |

| Market | 13,640 | 1.953 | 4.883 | 0.009 | 0.345 | 33.325 |

| Control | 13,046 | 0.998 | 0.047 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Variables | Innov | SL | FDI | EduExpend | Property | Shareholding | Salary | Duality | Tax | Market | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innov | 1 | ||||||||||

| SL | 0.059 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| FDI | 0.080 *** | −0.108 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| EduExpend | 0.119 *** | 0.204 *** | 0.569 *** | 1 | |||||||

| Property | 0.141 *** | 0.007 | −0.057 *** | 0.032 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Shareholding | −0.098 *** | −0.021 ** | 0.113 *** | 0.078 *** | −0.506 *** | 1 | |||||

| Salary | 0.296 *** | 0.138 *** | 0.189 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.012 | −0.105 *** | 1 | ||||

| Duality | −0.043 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.102 *** | 0.075 *** | −0.328 *** | 0.259 *** | −0.008 | 1 | |||

| Tax | 0.303 *** | 0.005 | −0.002 | 0.055 *** | 0.263 *** | −0.271 *** | 0.447 *** | −0.157 *** | 1 | ||

| Market | 0.181 *** | −0.018 ** | 0.032 *** | 0.082 *** | 0.221 *** | −0.191 *** | 0.189 *** | −0.099 *** | 0.405 *** | 1 | |

| Control | 0.018 ** | −0.006 | 0.020 ** | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.017 * | 0.004 | 0.002 | −0.003 | 1 |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| SL | 1.73 | 0.577 |

| FDI | 1.69 | 0.593 |

| EduExpend | 1.63 | 0.615 |

| Property | 1.52 | 0.658 |

| Shareholding | 1.44 | 0.696 |

| Salary | 1.43 | 0.698 |

| Duality | 1.25 | 0.801 |

| Tax | 1.17 | 0.852 |

| Market | 1.14 | 0.877 |

| Control | 1.00 | 0.999 |

| Mean VIF | 1.40 | 0.0 |

| Variable | (1) Innov | (2) Innov |

|---|---|---|

| SL | 0.028 | 0.055 *** |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | |

| Controls | No | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 13,913 | 10,080 |

| R2 | 0.836 | 0.852 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.807 | 0.823 |

| Variable | (1) Innov | (2) SL |

|---|---|---|

| SL | 0.217 *** | |

| (0.030) | ||

| Innov | 0.024 *** | |

| (0.003) | ||

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 10,301 | 10,301 |

| R2 | 0.143 | 0.178 |

| Variable | (1) First-Stage SL | (2) Second-Stage Innov |

|---|---|---|

| SL | 0.126 ** | |

| (0.059) | ||

| IV | 0.159 *** | |

| (0.013) | ||

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 10,078 | 10,078 |

| R2 | 0.583 | 0.011 |

| The K-P rk LM statistic | 19.968 *** | |

| The K-P rk Wald F statistic | 156.602 | |

| [16.38] | ||

| Variable | (1) Innov_grant | (2) Innov_invest | (3) Innov | (4) Innov | (5) Innov | (6) Innov | (7) Innov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL | 0.034 * | 0.035 ** | 0.054 ** | 0.015 ** | 0.056 *** | 0.053 ** | 0.045 ** |

| (0.019) | (0.018) | (0.025) | (0.008) | (0.021) | (0.020) | (0.019) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Policy1 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Policy2 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 9132 | 9096 | 10,080 | 9742 | 9752 | 10,080 | 10,080 |

| R2 | 0.839 | 0.918 | 0.852 | 0.228 | 0.851 | 0.852 | 0.852 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.806 | 0.900 | 0.820 | 0.822 | 0.823 | 0.823 |

| Variable | (1) Tech | (2) Innov | (3) Adm | (4) Innov | (5) DA | (6) Innov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL | 0.005 ** | 0.040 * | −0.027 ** | 0.049 *** | 0.043 ** | 0.033 * |

| (0.002) | (0.020) | (0.012) | (0.010) | (0.019) | (0.020) | |

| Tech | 2.800 *** | |||||

| (0.051) | ||||||

| Adm | −0.201 *** | |||||

| (0.045) | ||||||

| DA | 0.502 *** | |||||

| (0.103) | ||||||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 10,094 | 10,068 | 10,010 | 9984 | 5995 | 5976 |

| R2 | 0.878 | 0.857 | 0.663 | 0.861 | 0.863 | 0.859 |

| Sobel Z | 2.260 ** | 1.971 ** | 2.005 ** | |||

| Variable | Innov | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) High-Competition | (2) Low-Competition | (3) High Transparency | (4) Low Transparency | |

| SL | 0.075 *** | 0.003 | 0.049 ** | 0.038 |

| (0.020) | (0.048) | (0.022) | (0.083) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 7062 | 2636 | 8334 | 632 |

| R2 | 0.848 | 0.881 | 0.859 | 0.863 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y. How Does Smart Logistics Influence Enterprise Innovation? Evidence from China. Systems 2025, 13, 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121076

Xu S, Zhou Y, Wang Y. How Does Smart Logistics Influence Enterprise Innovation? Evidence from China. Systems. 2025; 13(12):1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121076

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Shuhui, Yaodong Zhou, and Yanan Wang. 2025. "How Does Smart Logistics Influence Enterprise Innovation? Evidence from China" Systems 13, no. 12: 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121076

APA StyleXu, S., Zhou, Y., & Wang, Y. (2025). How Does Smart Logistics Influence Enterprise Innovation? Evidence from China. Systems, 13(12), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121076