Factors Associated with Travel Patterns Among Mixed-Use Development Residents in Klang Valley, Malaysia, Before and During COVID-19: Mixed-Method Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Relationship Between Land Use, Travel Measures and Trip Internalisation

2.2. Factors Influencing Land Use Mix

2.3. Travel Behaviour During Disease Outbreaks/COVID-19

2.4. Mixed Land Use in Malaysia and the Impacts of COVID-19

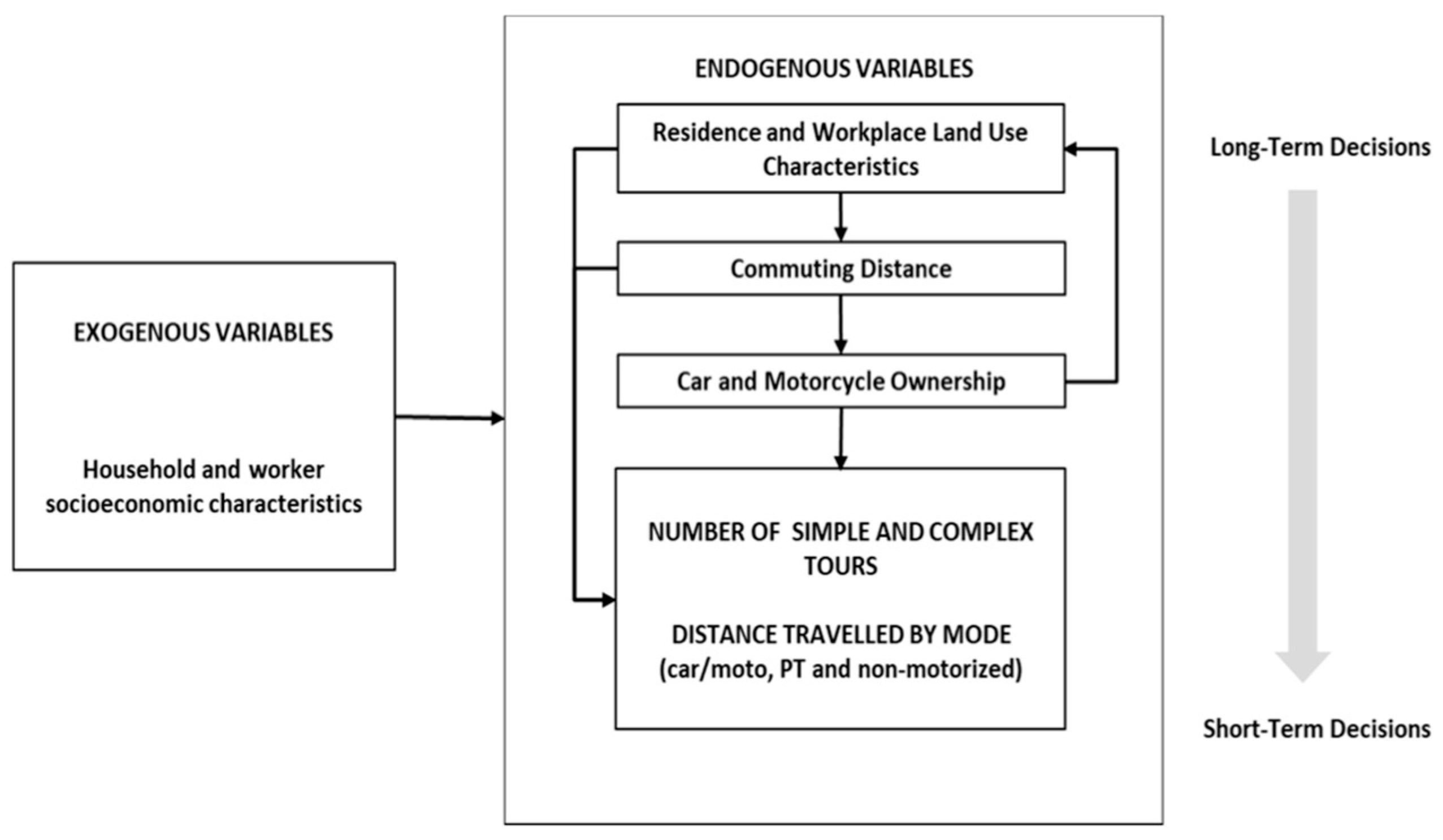

2.5. Conceptual Model

2.6. Model Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Study Design

3.2. Study Duration and Study Population

3.3. Questionnaire Design

3.4. Pilot Study

3.5. Ethical Approval

3.6. Administration of the Questionnaire and Data Collection

3.7. Data Management and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Survey Findings

4.1.1. MXD Residents’ Demographics

4.1.2. Descriptive Findings Based on Classes of Travel Frequency

4.1.3. Factors Associated with External Travel Frequency Before and During COVID-19

4.1.4. Factors Associated with Internal Travel Frequency Before and During COVID-19

4.2. Qualitative Phase Findings

4.2.1. Descriptive Results

4.2.2. Thematic Analysis Findings

“Save time to travel and jam just to buy some groceries or necessities, and even dining”(MXD resident 5)

I believe internalisation of trips is very important, especially in today’s fast-paced lifestyle. Having daily necessities like groceries, food, and beverage options within the residential area makes life much more convenient”(MXD Resident 25)

“It will always come with pros & cons. In my opinion, condos full of shopping & dining facilities will be convenient sometimes, but it will affect the comfort of staying in the above properties”(MXD 18)

“Internal trips mainly for health since there are swimming pools and gyms. Also able to jog around the condominium gated compound.”(MXD 13)

“I prefer using the facilities around here because they help to release stress, which is definitely good for my health”(MXD 28)

“Reduce travelling time and minimise the stress associated with traffic congestion(MXD 32)

“It’s not my preference as I still prefer heading outside of my residential area to maintain a healthy social lifestyle.”(MXD 6)

“Maximise quality time with family members as more time could be spent on them”(MXD 50)

“Internal trips are important for strengthening team bonding, enhancing communication, and fostering a sense of belonging”(MXD 21)

“For social interactions, saving money by buying groceries, a breath of fresh air”(MXD 39)

“Reduce carbon footprint (petrol, jams), supports the immediate local economy, reduces wastage (resources, time, accidents, etc.)”(MXD 10)

“It promotes a more sustainable lifestyle by minimising the need for transportation, which can reduce traffic congestion and environmental impact.”(MXD 22)

“I think internalisation of trips is essential, especially in condominiums, as it is able to reduce carbon emissions by residents to travel from their house to shopping malls or supermarkets for shopping.”(MXD 48)

“A residential area that has no development and bad management. Then there’s no reason for the occurrence of internal trips as no options are available internally”(MXD 8)

Lack of options. No cafes/restaurants, only marts. Marts have limited options as well(MXD 18)

“No such option available at my current residential area”(MXD 32)

“The establishments in the MXD do not constitute to functional ecosystem”(MXD 45)

“I think the MXD areas are already designed and well-developed to enhance internal trips, but they are not managed properly”(MXD 20)

“In order to improve internal trips, it goes beyond building condominiums and creating MXD areas; the management of these facilities is key for sustainable usage”(MXD 41)

“There is a gym in my residential area, but I don’t use it because the place is always crowded and ill-managed”(MXD 51)

“I feel we are just being lazy in using MXD services available at our disposal. Most people prefer driving all the time, even to the nearest mall or grocery store”(MXD 4)

“People don’t just have the interest to reduce external trips; maybe they are unaware of its effects on well-being. However, sometimes it boils down to poor communication”.(MXD 27)

“For me, I go outside because I would be sick of the repetition of activities”(MXD 31)

“I don’t like using the facility in my residential MXD area because it’s too noisy and poorly designed and currently used by so many people”(MXD 21)

“Noise, overcrowding, or poor design of shared spaces can also reduce the appeal of internal trips”(MXD43)

“Good management, good development, more options. More essential spots, especially markets, clinics, barbershop surrounding the area”(MXD 8)

“More online shopping & efficient delivery service”(MXD 15)

“Developers can include more essential facilities within residential areas, such as grocery stores, convenience stores (like 7-Eleven), local eateries, pharmacies, and laundromats”(MXD 36)

“Encouraging mobile services like food delivery, parcel lockers, and online grocery platforms (e.g., GrabMart, HappyFresh) is another effective way”(MXD 42)

“Strengthening public transport and last-mile connectivity options, such as feeder buses or e-scooters, can help reduce reliance on personal vehicles when external travel is unavoidable”(MXD 6)

“The layout of MXD areas needs to be improved. Population density in these areas surpasses the available structures and facilities, so we need to balance the density. Completeness of amenities is also crucial”.(MXD 44)

“The developers plan the MXD environment and facilities to their taste rather than considering the residents’ needs”(MXD 24)

“We are not carried along in the planning and implementation of various policies relating to MXD development, no way to reduce external trips if you don’t understand the main problem faced by residents”(MXD 37)

“Reducing external trips can be done by hosting engaging events and forming interest groups”(MXD 10)

“Organising community events such as weekend markets, workshops, or wellness activities can promote social interaction and engagement within the development itself”(MXD 18)

“Encourage flexible work-from-home policies”(MXD 21)

“With the advent of digital technologies, businesses can implement or expand remote work opportunities to reduce the need for employees to commute daily. This could significantly lower the number of trips taken, particularly during peak hours”(MXD 39)

5. Discussion

Theoretical and Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| MXD | mixed-use development |

| LUM | land use mix |

| MCO | Movement control order |

| TOD | Transit-oriented development |

| TAZs | Traffic analysis zones |

| MTGM | Malaysian Trip Generation Manual |

| HPU | Highway Planning Unit |

| MoWM | Ministry of Works Malaysia |

References

- Zhuo, Y.; Jing, X.; Wang, X.; Li, G.; Xu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. The Rise and Fall of Land Use Mix: Review and Prospects. Land 2022, 11, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Piao, L.; Zang, X.; Luo, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Rong, J. Analysing differences of highway lane-changing behaviour using vehicle trajectory data. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2023, 624, 128980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Knaap, G.-J. Measuring the effects of mixed land uses on housing values. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2004, 34, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Park, K.; Ewing, R.; Watten, M.; Walters, J. Traffic generated by mixed-use developments—A follow-up 31-region study. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 78, 102205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Ewing, R.; White, A.; Hamidi, S.; Walters, J.; Goates, J.P.; Joyce, A. Traffic generated by mixed-use developments: Thirteen-region study using consistent measures of built environment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2500, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Amin, A. Factors influencing Chinese residents’ post-pandemic outbound travel intentions: An extended theory of planned behaviour model based on the perception of COVID-19. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Baker, D.; Washington, S.; Turrell, G. Advance transit-oriented development typology: Case study in Brisbane, Australia. J. Transp. Geog. 2011, 34, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Liu, J.; Wu, S. The effects of TOD on economic vitality in the post-COVID-19 era. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2025, 58, 101247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L. Urban resilience. Urban Stud. 2022, 59, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, N.H.; Ismail, S.; Che Amat, R.; Durdyev, S.; Konečná, Z.; Chofreh, A.G.; Goni, F.A.; Subramaniam, C.; Klemeš, J.J. Stakeholders’ Impact Factors of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sustainable Mixed Development Projects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askitas, N.; Tatsiramos, K.; Verheyden, B. Lockdown strategies, mobility patterns and COVID-19. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.00531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axhausen, K.W. The impact of COVID-19 on Swiss travel. In Proceedings of the Internet Access, Automation and COVID-19: On the Impacts of New and Persistent Determinants of Travel Behaviour (TRAIL and TU Delft Webinar 2020), Online, 13 July 2020; IVT ETH Zurich: Zurich, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kolarova, V.; Eisenmann, C.; Nobis, C.; Winkler, C.; Lenz, B. Analysing the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on everyday travel behaviour in Germany and potential implications for future travel patterns. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartenì, A.; Di Francesco, L.; Martino, M. The role of transport accessibility within the spread of the coronavirus pandemic in Italy. Safety Sci. 2020, 133, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, L.; Ison, S. Responsible transport: A post-COVID agenda for transport policy and practice. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. 2020, 6, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, N.A.; Long, F. To travel, or not to travel? The impacts of travel constraints and perceived travel risk on travel intention among Malaysian tourists amid the COVID-19. J. Consumer Behav. 2022, 2, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, C.; Abd Rahman, N.; Abdullah, M.; Sukor, N.S.A. Influence of COVID-19 mobility-restricting policies on individual travel behaviour in Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Greenwald, M.; Zhang, M.; Walters, J.; Feldman, M.; Cervero, R.; Frank, L.; Thomas, J. Traffic generated by mixed-use developments—Six-region study using consistent built environmental measures. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2011, 137, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarian, P.L.; Van Herick, D. Viewpoint: Quantifying residential self-selection effects: A review of methods and findings from applications of propensity score and sample selection approaches. J. Transp. Land Use 2016, 9, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X. Residential self-selection in the relationships between the built environment and travel behaviour: Introduction to the special issue. J. Transp. Land Use 2014, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Dumbaugh, E.; Brown, M. Internalising travel by mixing land uses: Study of master-planned communities in South Florida. Transp. Res. Rec. 2001, 1780, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, T.-H. An analysis of the relationship between land use and weekend travel: Focusing on the internal capture of trips. Sustainability 2018, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, M.J. The relationship between land use and intrazonal trip-making behaviours: Evidence and implications. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2006, 11, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Kone, A.; Tooley, S.; Ramphul, R. Trip Internalization and Mixed-Use Development: A Case Study of Austin, Texas; Center for Transportation Research: Austin, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, A.; Ivaki, Y.E. The influence of urban physical form on trip generation, evidence from metropolitan Shiraz, Iran. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2011, 4, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaugh, K.; El-Geneidy, A. What makes travel ‘local’: Defining and understanding local travel behaviour. J. Transp. Land Use 2012, 5, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E.; Knaap, G. Legalising Smart Growth: An Empirical Study of Land Use Regulation in Illinois. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2003, 22, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. The Analysis of Measurements and Factors of the Spatial Pattern of Mixed Land Use. Ph.D. Thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C. Patterns and Influenced Factors of Urban Mixed-Use Development: A Case Study of Tainan City. Ph.D. Thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. A Study of Mixed Land Use Around Mass Rapid Transit Station. Ph.D. Thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Mashrur, S.M.; Loa, P.; Habib, K.N. COVID-19 influenced households’ Interrupted Travel Schedules (Covhits) survey: Lessons from the fall 2020 cycle. Transp. Policy 2021, 112, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.; Macfarlane, G.; Flint, A.; Ross, G.; Forsyth, L.; Fraser, D. Barriers to Delivering Mixed Use Development: Final Report; The Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2009.

- Sun, X. Concept Analysis of the “White Site” in Singapore. City Plan. Rev. 2003, 27, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, Y. To be a Fox or a Hedgehog?—Comparative Study on the Land Category Systems Between Hong Kong and China Mainland. Planners 2008, 6, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, A.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Kaplanidou, K.; Zhan, F. Destination risk perceptions among U.S. residents for London as the host city of the 2012 Summer Olympic Games. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwari, N.; Tawkir, M.A.; Islam, M.R.; Hadiuzzaman, M.; Amin, S. Exploring the travel behaviour changes caused by the COVID-19 crisis: A case study for a developing country. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100334. [Google Scholar]

- Cahyanto, I.; Wiblishauser, M.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A. The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the U.S. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peak, C.M.; Wesolowski, A.; Zu Erbach-Schoenberg, E.; Tatem, A.J.; Wetter, E.; Lu, X.; Power, D.; Weidman-Grunewald, E.; Ramos, S.; Moritz, S.; et al. Population mobility reductions associated with travel restrictions during the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone: Use of mobile phone data. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 1562–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggat, P.A.; Brown, L.H.; Aitken, P.; Speare, R. Level of Concern and Precaution Taking Among Australians Regarding Travel During Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: Results From the 2009 Queensland Social Survey. J. Travel Med. 2010, 17, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Song, H.-J.; Bendle, L.J.; Kim, M.-J.; Han, H. The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behaviour. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Henry, R.E.; Lee, Y.-K.; Berro, A.D.; Maskery, B.A. The effects of past SARS experience and proximity on declines in numbers of travellers to the Republic of Korea during the 2015 MERS outbreak: A retrospective study. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 30, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behaviour. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100121. [Google Scholar]

- Shamshiripour, A.; Rahimi, E.; Shabanpour, R.; Mohammadian, A. How is COVID-19 reshaping activity-travel behaviour? Evidence from a comprehensive survey in Chicago. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irawan, M.Z.; Belgiawan, P.F.; Joewono, T.B.; Bastarianto, F.F.; Rizki, M.; Ilahi, A. Exploring activity-travel behaviour changes during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Transportation 2021, 49, 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airak, S.; Sukor, N.S.A.; Rahman, N.A. Travel behaviour changes and risk perception during COVID-19: A case study of Malaysia. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 18, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Works Malaysia. Malaysian Trip Generation Manual 2020; MyTripGen 2020: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2022.

- Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH). Annual Report 2021; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2021. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/Penerbitan/Penerbitan%20Utama/ANNUAL%20REPORT/Annual_Report_MoH_2021-compressed.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Rowley, A. Mixed-use development: Ambiguous concept, simplistic analysis and wishful thinking? Plan. Pract. Res. 1996, 11, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopenbrouwer, E.; Louw, E. Mixed-use Development: Theory and Practice in Amsterdam’s Eastern Docklands. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 968–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. Research on the Evolvement, Mechanism and Construction of Work-Live Community Based on Mixed-Use Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bordoloi, R.; Mote, A.; Sarkar, P.P.; Mallikarjuna, C. Quantification of Land Use diversity in the context of mixed land use. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 104, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Lloyd-Jones, T. Mixed uses and urban design. In Reclaiming the City: Mixed-Use Development; Coupland, A., Ed.; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1997; pp. 149–178. [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg, C.A.; Vreeker, R.; Nijkamp, P. Multifunctional Land Use: An Economic Perspective. In The Economics of Multifunctional Land Use; Nijkamp, P., Rodenburg, C., Vreeker, R., Eds.; Shaker Publishing B.V.: Maastricht, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S. Quantifying spatial characteristics of cities. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2005–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu e Silva, J. Spatial self-selection in land-use–travel behaviour interactions: Accounting simultaneously for attitudes and socioeconomic characteristics. J. Transp. Land Use 2014, 7, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lehto, X.Y.; Morrison, A.M.; Jang, S. Structure of travel planning processes and information use patterns. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinjari, A.R.; Pendyala, R.M.; Bhat, C.R.; Waddell, P.A. Modelling the choice continuum: An integrated model of residential location, auto ownership, bicycle ownership, and commute tour mode choice decisions. Transportation 2011, 38, 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Habib, K.M.N. Unravelling the relationship between trip chaining and mode choice: Evidence from a multi-week travel diary. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2012, 35, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, H.B. Introduction to Transportation Engineering, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, B.H.; Yuen, C.W.; Onn, C.C. Improvement of trip generation rates for mixed-use development in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, F.L.; Maglasang, R.S.; Moridpour, S.; Taboada, E.B. Exploring the changes in travel behaviour in a developing country amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from Metro Cebu, Philippines. Transp. Res. Interdisc. 2021, 12, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wan, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, M. Travel before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring factors in essential travel using empirical data. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 110, 103640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconcin, P.; Werneck, A.O.; Peralta, M.; Ihle, A.; Gouveia, É.R.; Ferrari, G.; Sarmento, H.; Marques, A. The association between physical activity and mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Huang, M.; Gong, D.; Ge, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhu, D.; Chen, Y.; Altan, O. Carbon balance dynamic evolution and simulation coupling economic development and ecological protection: A case study of Jiangxi Province at county scale from 2000–2030. Int. J. Digital Earth 2025, 18, 2448572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, R.D.; Lakes, K.D.; Hopkins, W.G.; Tarantino, G.; Draper, C.E.; Beck, R.; Madigan, S. Global changes in child and adolescent physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Paediatr. 2022, 176, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.; Félix, R.; Marques, M.; Moura, F. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on the behaviour change of cyclists in Lisbon, using multinomial logit regression analysis. Transp. Res. Interdisc. 2022, 14, 100609. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Li, L.; Zhu, J. Impact of the consciousness factor on the green travel behaviour of urban residents: An analysis based on interaction and regulating effects in the Chinese cultural context. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Loo, B.P.Y.; Axhausen, K.W. Travel behaviour changes under Work-from-home (Wfh) arrangements during COVID-19. Trav. Behav. Soc. 2023, 30, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, R.; McNally, M.G.; Sarwar Uddin, Y.; Ahmed, T. Impact of working from home on activity-travel behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An aggregate structural analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 159, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackett, R.L. Children’s travel behaviour and its health implications. Transp. Policy 2013, 26, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M.; Hirvonen, J.; Rudner, J.; Pirjola, I.; Laatikainen, T. The last free-range children? Children’s independent mobility in Finland in the 1990s and 2010s. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Bhatta, K.; Roman, M.; Gautam, P. Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Travel Decision-Making of Poles and Nepalis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, D.; Stoeckl, N.; Liu, H.-B. The impact of economic, social and environmental factors on trip satisfaction and the likelihood of visitors returning. Tour Manag. 2016, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.D.; Caulfield, B. Implications of COVID-19 for future travel behaviour in the rural periphery. Eur. Trans. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, P.; Murphy, E.; Redmond, D. Residential preferences of the “creative class”? Cities 2013, 31, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T. Comparative analysis of household car, motorcycle and bicycle ownership between Osaka metropolitan area, Japan and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Transportation 2009, 36, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakib, S.; Hawkins, J.; Habib, K.N. COVID-19 Impact on Residential Relocation Choice in the GTA: Result from a Specialised Survey Cycle I in Summer 2020. Available online: https://uttri.utoronto.ca/files/2020/12/UTTRI-Report-COVID-19-Impact-on-Residential-Relocation-Choice-Shakib-2020.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

| Old Class | New Classes |

|---|---|

| Class 1 | Seldom/Never |

| Once monthly | |

| Class 2 | 2 trips/month |

| More than 2 trips/month | |

| Once weekly | |

| Class 3 | 2 trips weekly |

| >2 trips weekly | |

| Once daily | |

| 2 trips daily | |

| >than 2 trips daily |

| No. | Variable | Characteristic/Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender | Male | 80 | 59.70 |

| Female | 54 | 40.30 | ||

| 15–24 years (early working age) | 38 | 28.36 | ||

| 25–54 years (prime working age) | 93 | 69.40 | ||

| 55–64 years (mature working age) | 3 | 2.24 | ||

| 3 | Marital status | Single | 80 | 59.70 |

| Engaged | 21 | 15.67 | ||

| Married | 31 | 23.14 | ||

| Divorced | 2 | 1.49 | ||

| 4 | Employment status | Student | 35 | 26.12 |

| Employed as government servants | 11 | 8.21 | ||

| Employed by the private sector | 58 | 43.28 | ||

| Employed by a non-governmental organisation | 4 | 2.98 | ||

| Self-employed/Own business/freelancer | 14 | 10.45 | ||

| Unemployed (retired, housewife, graduate) | 11 | 8.21 | ||

| Unable to work | 1 | 0.75 | ||

| 5 | Monthly income | >RM 10000 per month | 11 | 8.21 |

| >RM 5000 < RM 10,000 per month | 32 | 23.88 | ||

| <RM 5000 per month | 54 | 40.30 | ||

| No source of income | 37 | 27.61 | ||

| 6 | Household size | Single staying | 45 | 33.58 |

| Small family with 2 to 4 members | 59 | 44.03 | ||

| Medium-sized family with 5 to 10 members | 30 | 22.39 | ||

| 7 | Private transport ownership | 1 car | 65 | 48.51 |

| 1 motorcycle | 15 | 11.19 | ||

| 1 car and 1 motorcycle | 1 | 0.75 | ||

| More than 1 unit of cars and motorcycles | 4 | 2.98 | ||

| No private transport | 49 | 36.57 | ||

| 8 | Allocation/subscription of personal parking lot | 1 unit of parking lot per household | 58 | 43.28 |

| 2 units of parking lot per household | 40 | 29.85 | ||

| 3 units of parking lot per household | 16 | 11.94 | ||

| No/Not applicable | 20 | 14.93 | ||

| 8 | Residence property ownership | Sole Ownership | 54 | 40.30 |

| Tenant | 56 | 41.79 | ||

| Sub-tenant | 24 | 17.91 | ||

| 10 | Housing occupancy duration | Less than 1 year | 24 | 17.91 |

| Between 1 and 2 years | 25 | 18.66 | ||

| More than 2 years | 85 | 63.43 |

| Before COVID-19 (October 2019 to January 2020) | During COVID-19 (March 2020 to September 2020) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External travels | Internal travels | External travels | Internal travels | |||

| Categories | N | N | p-value | N | N | p-value |

| Class 1 | 6 | 4 | 0.025 | 1 | 21 | 0.001 |

| Class 2 | 20 | 42 | 7 | 22 | ||

| Class 3 | 85 | 88 | 47 | 17 | ||

| Total | 111 | 134 | 55 | 57 | ||

| Variable (Reference Category) | Covariates | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | Exp (Coef) | Coefficients | Coefficients | Exp (Coef) | p-Value | |||

| Intercept | −0.022 | 0 | 0.11 | |||||

| Age | 0.054 | 1.05 | 0 | −0.005 | 0.99 | 0.032 | ||

| Employment Status (Government Servant) | NGO | −0.056 | 0.94 | 0 | −0.004 | 0.99 | 0.010 | |

| Private Sector | −0.019 | 0.98 | 0 | −0.027 | 0.97 | |||

| Self-Employed | −0.19 | 0.98 | 0 | −0.028 | 0.97 | |||

| Student | 0.016 | 1.01 | 0 | −0.075 | 0.92 | |||

| Unable to work | −0.028 | 0.97 | 0 | −0.056 | 0.94 | |||

| Unemployed | −0.089 | 0.91 | 0 | −0.11 | 0.88 | |||

| Income | 0.091 | 1.09 | 0 | 0.073 | 1.07 | 0.046 | ||

| Transport Ownership (No private transport) | 1 motorcycle | −0.009 | 0.99 | 0 | −0.008 | 0.99 | 0.021 | |

| 1 car | 0.069 | 1.07 | 0 | 0.10 | 1.10 | |||

| A car and motorcycle | 0.013 | 1.01 | 0 | 0.06 | 1.06 | |||

| Multiple cars and motorcycles | 0.014 | 1.01 | 0 | 0.028 | 1.02 | |||

| Occupancy Duration | 0.013 | 1.01 | 0 | −0.016 | 0.98 | 0.047 | ||

| Variable (Reference Category) | Covariates | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | Exp (Coef) | Coefficients | Coefficients | Exp (Coef) | p-Value | |||

| Intercept | −0.05952 | 0 | 0.058 | |||||

| Gender | 0.006 | 1.00 | 0 | 0.01 | 1.013 | 0.020 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.98 | 0 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.001 | ||

| Employment Status (Government Servant) | NGO | 0.049 | 1.05 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.039 | ||

| Private Sector | −0.01 | 0.98 | 0 | 0.008 | ||||

| Self-employed | −0.03 | 0.96 | 0 | 0.066 | ||||

| Student | −0.01 | 0.98 | 0 | 0.021 | ||||

| Unable to work | −0.00 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.065 | ||||

| Unemployed | 6.78 0.00 | 1.00 | 0 | 0.021 | 0.046 | |||

| Income | −0.02 | 0.97 | 0 | −0.010 | 0.98 | 0.034 | ||

| Transport Ownership (No private transport) | 1 motorcycle | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0 | −0.09 | 0.91 | 0.002 | |

| 1 car | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0 | −0.083 | 0.92 | |||

| Both a car and motorcycle | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0 | −0.10 | 0.89 | |||

| Multiple cars and motorcycles | 0.10 | 1.10 | 0 | 0.029 | 1.03 | |||

| Before COVID-19 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (Reference Category) | Covariates | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | ||||

| Coefficients | Exp (Coef) | Coefficients | Coefficients | Exp (Coef) | p-Value | |||

| Intercept | −0.04079 | 0 | 0.11 | |||||

| Employment Status (Government Servant) | NGO | 0.17 | 1.19 | 0 | 0.17 | 1.19 | 0.038 | |

| Private Sector | 0.33 | 1.40 | 0 | 0.06 | 1.06 | |||

| Self-employed | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0 | 0.07 | 1.07 | |||

| Student | 0.29 | 1.33 | 0 | 0.19 | 1.21 | |||

| Unable to work | 0.20 | 1.23 | 0 | 0.07 | 1.07 | |||

| Unemployed | 0.05 | 1.05 | 0 | 0.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Income | −0.05 | 0.94 | 0 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 0.002 | ||

| During COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Intercept | −0.004 | 0 | −0.01 | |||||

| Parking lot | X8 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0 | −0.00 | 0.99 | 0.021 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goh, B.H.; Yuen, C.W.; Onn, C.C. Factors Associated with Travel Patterns Among Mixed-Use Development Residents in Klang Valley, Malaysia, Before and During COVID-19: Mixed-Method Analysis. Systems 2025, 13, 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121045

Goh BH, Yuen CW, Onn CC. Factors Associated with Travel Patterns Among Mixed-Use Development Residents in Klang Valley, Malaysia, Before and During COVID-19: Mixed-Method Analysis. Systems. 2025; 13(12):1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121045

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoh, Boon Hoe, Choon Wah Yuen, and Chiu Chuen Onn. 2025. "Factors Associated with Travel Patterns Among Mixed-Use Development Residents in Klang Valley, Malaysia, Before and During COVID-19: Mixed-Method Analysis" Systems 13, no. 12: 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121045

APA StyleGoh, B. H., Yuen, C. W., & Onn, C. C. (2025). Factors Associated with Travel Patterns Among Mixed-Use Development Residents in Klang Valley, Malaysia, Before and During COVID-19: Mixed-Method Analysis. Systems, 13(12), 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121045