1. Introduction

Workplace relationships fundamentally shape organizational performance, particularly in public administration, where complex institutional environments demand strong relational coordination [

1]. Leader–member exchange theory emphasizes the quality of dyadic relationships between leaders and subordinates as a critical mechanism shaping employee attitudes and behaviors [

2]. High-quality leader–member exchange (LMX) is characterized by mutual trust, respect, and liking, providing employees with greater access to resources, support, and development opportunities, whereas low-quality LMX relies more on formal contracts and limited interaction [

3]. While extensive private-sector research demonstrates LMX’s positive effects on performance, commitment, and reducing counterproductive behaviors [

4,

5,

6], public sector contexts may exhibit distinct mechanisms and boundary conditions.

Public organizations face distinctive challenges that differentiate them from private firms—limited market signals, purchaser–beneficiary separation, competing stakeholder demands, and a strong emphasis on procedural fairness and equality [

1,

7]. In bureaucratic settings characterized by high formalization and hierarchical authority, civil servants operate under deeply institutionalized norms that prioritize equitable treatment over performance-based differentiation [

1]. These institutional features render relational mechanisms particularly salient: formal rules and material incentives often prove insufficient, and employee motivation and performance depend heavily on the quality of interpersonal relationships with their supervisors. Accordingly, examining how LMX operates in public administration—and under what conditions—is essential for theory and practice.

Despite the theoretical promise of LMX in public management, existing research has revealed two critical gaps. First, while preliminary studies show that high-quality LMX reduces turnover intentions and enhances work engagement among civil servants [

8,

9,

10], the mechanisms linking LMX to job performance remain underexamined. Specifically, LMX influences performance through dual complementary pathways: a motivation pathway via perceived social impact and a capability pathway via career adaptability. These mechanisms are particularly salient in public administration, where civil servants’ performance depends critically on prosocial motivations to serve the public interest and the adaptive capacity to navigate complex, ambiguous institutional demands [

11,

12]. These two pathways are functionally complementary: perceived social impact reflects the proximal and affective motivational energy that fuels immediate engagement, whereas career adaptability represents the long-term adaptive capacity for handling evolving role complexity—two functionally distinct yet complementary forms of psychological capital. However, empirical evidence of this dual-pathway model in public organizations remains limited. In addition, prior research has not adequately examined how the public sector’s institutional emphasis on fairness and equality shapes the operation of these pathways. The role of LMX differentiation—the extent to which leaders form varying-quality relationships with different subordinates [

13,

14]—remains overlooked in public administration, despite its potential to signal distributive unfairness in contexts where equitable treatment is normatively expected.

This study addresses these gaps by developing and testing a moderated mediation model that explains how LMX influences civil servant performance through dual pathways. Drawing on social information processing theory [

15], we propose that high-quality LMX supplies positive social cues that heighten the perceptions of work-related social influence, stimulate intrinsic motivation, and improve performance. Concurrently, building on career construction theory [

16], we argue that high-quality LMX offers a supportive context and developmental opportunities that build career adaptability, thereby enhancing performance.

Critically, we extend these perspectives by theorizing that the public sector’s institutional emphasis on procedural fairness and equality makes these pathways vulnerable to disruption. Unlike private-sector settings, where performance-based differentiation may be acceptable, the bureaucratic norms of public organizations render any visible relational inequality highly consequential. To capture this institutional dynamic, we introduce perceived LMX differentiation (PLMXD) as a critical boundary condition. While LMX reflects an individual’s own exchange quality with their leader, PLMXD represents employees’ subjective perceptions of relational disparities within their work unit—a distinct social–contextual cue that fundamentally alters how individuals interpret their organizational environment [

13,

14]. Drawing on justice theory [

17,

18], we argue that when employees perceive that their leader forms varying-quality relationships with different team members, they interpret this differentiation as a signal of distributive unfairness and procedural bias. Such perceived relational inequality triggers negative emotions and cognitions. It prompts employees to question their own status and organizational fairness, thereby eroding the motivation- and capability-related benefits of high-quality LMX. Conversely, when differentiation is low, the fairness and equality norms reinforce trust and cooperation within the work unit, amplifying LMX’s positive influence.

We test this moderated mediation model using two-wave survey data from 363 grassroots civil servants in Province A, China, employing structural equation modeling to assess the proposed relationships. This study makes three distinctive theoretical contributions to public management research. First, by conceptualizing perceived social impact as a subjective cognitive outcome of the way individuals process work-related information, we extend social information processing theory to illustrate how relational cues help members interpret the social influence of their work—a mechanism particularly relevant in public service, where mission-driven motivation is central. Second, drawing on career construction theory, we highlight the supportive role of relational resources in fostering civil servants’ career adaptability, thereby extending the theory beyond individual traits to the relational mechanisms that promote adaptive growth in bureaucratic settings. Third, and most critically, we theorize and empirically demonstrate that LMX differentiation operates as a critical social cue that shapes civil servants’ performance. In public administration—where procedural justice, equity, and bureaucratic accountability are deeply institutionalized—LMX differentiation is more likely to be construed as favoritism or unfairness than in private firms. Such differentiation not only reflects the structural features of public organizations but also profoundly influences employees’ role perceptions and career development, thereby deepening our understanding of micro-level relational dynamics in public systems. By clarifying these mechanisms and boundary conditions, this study advances both LMX theory and public management scholarship, offering insights into how public leaders can foster employee performance.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

According to the social information processing theory [

15], individuals’ work attitudes and perceptions are shaped by social cues in their environment. In high-quality LMX relationships, the leader’s trust, support, and respect [

2,

3] signal to their employees that their work is valued, enhancing their belief that their efforts positively impact others—thus contributing to their perceived social impact [

19]. We propose perceived social impact as a key motivational mediator linking LMX to civil servants’ performance, as it is particularly salient in public organizations for two reasons. First, perceived social impact resonates strongly with public service values that emphasize collective service and public welfare [

11,

20]. Civil servants are intrinsically motivated by the belief that their work benefits society, and perceived social impact captures this core prosocial dynamic [

19]. Second, given the complexity and ambiguity inherent in public sector work [

12,

21], perceived social impact helps civil servants connect their daily tasks to broader societal goals, enhancing their sense of meaning and engagement [

22,

23]. Unlike generic motivational constructs, perceived social impact specifically addresses how relational quality translates into prosocial motivation—a particularly critical mechanism in public service contexts where work fundamentally serves others.

In high-quality LMX relationships, leaders provide essential support, encouragement, and career investment for their subordinates, helping civil servants overcome resource shortages. This encourages civil servants to realize that their work is valued by the organization, providing them with the social cue that “my work benefits others” [

22]. High-quality LMX relationships also create deeper, more open communication channels. Leaders can provide honest, constructive feedback and advice, helping civil servants better connect their daily tasks with the public mission [

2]. This communication process enables civil servants to understand that even mundane administrative tasks contribute to social welfare, thus giving their work deeper meaning and enhancing their perceived social impact [

19]. From a complementary social exchange theory perspective [

24,

25], high-quality LMX creates reciprocal obligations built on mutual trust and investment. When leaders invest in subordinates through career development opportunities and socioemotional support, subordinates feel obliged to reciprocate [

4,

26]. This reciprocity manifests as increased perceived social impact—employees feel their actions matter both to the leader who has invested in them and to the public they serve [

27]. The affective connection in LMX relationships further amplifies this perception. Mutual regard between leaders and subordinates fosters more frequent work interactions [

3]. Through these interactions, the leader’s commitment is interpreted and internalized as a model of meaningful service, strengthening the civil servant’s sense of social impact [

28]. When civil servants identify with committed leaders and observe their prosocial behaviors, they more readily link their own efforts to social contributions, reinforcing their perceptions of exerting a positive impact on others and society.

When civil servants’ perceived social impact increases, this positive recognition drives their performance and OCB. In the public sector, this impact is particularly important as it is closely linked to their intrinsic public service mission [

20]. When civil servants recognize that their actions benefit others, their personal efforts are seen as achieving positive outcomes for others. This awareness includes an assessment of their own abilities and the expected results, meaning they believe their efforts can lead to an effective performance that will benefit others [

19]. This foresight inspires them to invest the effort and complete their tasks while adhering to high standards, thus improving task performance. Furthermore, perceived social impact helps convert professional values into intrinsic motivation. When civil servants realize that their work is meaningful to the public, they develop a stronger sense of social responsibility and mission. This emotionally driven understanding encourages them to engage in behaviors beyond formal duties, such as helping colleagues or taking on additional responsibilities. In fact, research indicates that when employees recognize that their actions can benefit others, they are more motivated to exert effort [

29]. Their actions are no longer merely directed to complete tasks but are driven by a commitment to public service and a sense of social responsibility. This heightened prosocial motivation directly enhances both in-role task performance and extra-role organizational citizenship behaviors [

30]. Therefore, enhancing perceived social impact through high-quality LMX relationships will directly improve civil servants’ task performance and OCB.

Accordingly, Hypothesis 1 was proposed, which comprised the following:

Hypothesis 1a: LMX positively influences grassroots civil servants’ task performance through the enhancement of perceived social impact.

Hypothesis 1b: LMX positively influences grassroots civil servants’ OCB through the enhancement of perceived social impact.

According to career construction theory [

16,

31], career adaptability is defined as a psychological resource reflecting one’s readiness to deal with current and anticipated career tasks, transitions, and challenges [

32]. We propose career adaptability as another key mediator linking LMX to civil servants’ performance, functionally distinct from the pathway represented by perceived social impact. While perceived social impact reflects proximal affective motivational energy—the immediate sense of purpose derived from perceiving one’s work as socially impactful—career adaptability represents the long-term adaptive capacity acquired through psychosocial resources [

33,

34]. These are complementary forms of psychological capital operating through different mechanisms: perceived social impact addresses civil servants’ performance motivations, whereas career adaptability addresses whether they possess the capability to translate motivation into sustained performance. Career adaptability is particularly salient in public sector contexts. First, public administration involves evolving governance demands, complex citizen interactions, and frequent policy reforms [

23], requiring civil servants to continuously adapt to shifting priorities and resource constraints. Career adaptability comprises the psychological readiness and self-regulatory competencies necessary to navigate these challenges. In addition, in bureaucratic organizations where career paths depend heavily on supervisory relationships [

35,

36], career adaptability represents converting relational resources from LMX into proactive career management and problem-solving abilities.

Career construction theory views career building as a psychosocial activity that integrates the self with society [

16]. It identifies four core dimensions of career adaptability: concern (career planning and future orientation), control (responsibility for career decisions), curiosity (exploration of opportunities), and confidence (problem-solving self-efficacy) [

31,

33]. We argue that high-quality LMX functions as a developmental context that systematically enhances all four dimensions. As a social exchange relationship grounded in mutual obligation and reciprocity, LMX provides employees with critical career development resources [

4]. Subordinates in high-quality LMX relationships receive support, challenging assignments, increased responsibility, decision-making capabilities, and access to information from their leaders [

4,

37,

38]. These experiences foster career concern by clarifying long-term trajectories, enhance career control by granting autonomy and responsibility, stimulate career curiosity through exposure to diverse tasks and learning opportunities, and build career confidence through mastery experiences and positive feedback. In high-quality LMX relationships, frequent interactions and participation in decision-making help reduce uncertainty and ambiguity in career development [

4,

39], enabling civil servants to believe they can handle work-related challenges and proactively shape their career paths. According to the conservation of resources theory [

40,

41] and the resource-based view [

42], high-quality LMX serves as a social resource enabling the accumulation of cognitive and emotional capital. Career adaptability functions as a conversion hub that mobilizes these accumulated resources into proactive coping and a problem-solving capacity [

43]. Compared with the private sector, grassroots civil servants’ career development paths and access to resources depend more heavily on internal organizational hierarchies. In this context, LMX is not merely a working relationship but a vital channel through which employees access developmental resources, build positive self-conceptions, and cultivate career adaptability.

As a psychosocial resource, career adaptability has a significant impact on an employee’s task performance and OCB. Employees with higher career adaptability are better able to make long-term plans and adjust to their work environments, thereby improving job performance [

44]. They tend to demonstrate greater work engagement and proficiency [

45]. In contrast, individuals with limited adaptability may encounter difficulties in career planning and exhibit more negative workplace behaviors [

46]. This is also closely related to the process of self-regulation. As an adaptive resource, career adaptability is a self-regulatory ability that enables individuals to address unfamiliar, complex, and ill-defined problems arising from developmental career tasks, career transitions, and job trauma [

43]. It allows individuals to broaden, improve, and ultimately realize their self-concept in professional roles, thereby creating a working life and building a career framework [

32,

47]. Therefore, civil servants with high career adaptability can complete their formal work tasks efficiently. At the same time, their deep understanding of the public interest and abundant psychological resources motivate them to assume additional responsibilities. These extra-role efforts not only enhance organizational effectiveness but also promote public well-being.

Building on the above discussion, Hypothesis 2 was formulated, which comprised the following:

Hypothesis 2a: LMX positively influences grassroots civil servants’ task performance by increasing career adaptability.

Hypothesis 2b: LMX positively influences grassroots civil servants’ OCB by increasing career adaptability.

The effects of LMX may not be the same for all civil servants. Team contextual characteristics, particularly the perceived variability in leader–member relationships, shape how individuals interpret and respond to their own LMX quality. We define PLMXD as an individual’s perception of the extent to which the leader forms varying-quality relationships with different team members [

13,

48]. It captures whether employees perceive an overall uneven or inconsistent relational environment within the team. We argue that PLMXD serves as a critical situational cue that alters the effectiveness of individual LMX relationships. According to the fairness heuristic theory [

49,

50], individuals use fairness-related information as heuristic cues to judge the trustworthiness and legitimacy of authorities. Perception of a high LMX differentiation signals a violation of distributive and procedural justice norms [

51,

52], undermining the legitimacy of the leader’s actions and reducing employees’ work motivation [

53,

54]. This fairness-based mechanism is particularly salient in public-sector organizations, where fairness, procedural justice, and equal treatment are deeply institutionalized norms [

1,

11].

The relationship between LMX and perceived social impact depends critically on the level of PLMXD. When PLMXD is low, the relational environment is relatively egalitarian and fair. Civil servants can interpret their high-quality LMX relationships as authentic signals that their work is valued and contributes to others [

22]. The fairness climate strengthens the support climate, enabling civil servants to perceive that their work benefits the public and their colleagues [

55]. Social information processing theory [

15] posits that when differentiation is low, the dominant social cue is one of equity and shared support, which strengthens the individual’s ability to recognize the social value of their contributions. In contrast, when PLMXD is high, the strong situation theory [

56,

57] explains why LMX becomes ineffective. Strong situations are characterized by clear, salient cues that lead individuals to interpret the environment, thus constraining behavioral variance. High PLMXD creates a strong negative situation: the pronounced inequality in leader treatment signals favoritism, fostering a collective belief that the leader’s behavior is normatively illegitimate [

53,

58]. Even civil servants with high-quality LMX relationships recognize that such advantages stem from relational favoritism rather than the social value of their work. Such differentiation erodes the interpersonal justice climate within teams [

59], undermining recognition of their work’s social impact. This powerful fairness violation cue overrides individual relational advantages, leading to uniformly low or non-significant effects of LMX on perceived social impact [

57]. Thus, the positive effect of LMX on employees’ perceived social impact is stronger when perceived LMX differentiation is low than when it is high.

Hypothesis 3: When PLMXD is high, the positive effect of LMX on perceived social impact will weaken.

Building on this moderation logic, we propose a first-stage moderated mediation model. Because PLMXD weakens the relationship between LMX and perceived social impact, the entire indirect pathway from LMX through perceived social impact to performance outcomes will also be conditional on PLMXD. Specifically, when PLMXD is low, civil servants can effectively convert their high-quality LMX into stronger perceived social impact, which in turn enhances task performance and OCB. When PLMXD is high, the strong negative situation undermines this conversion process, attenuating the indirect effects. Thus, Hypothesis 4 was proposed, which comprised the following:

Hypothesis 4a: The indirect relationship between LMX and task performance via perceived social impact is stronger at lower than at higher levels of PLMXD.

Hypothesis 4b: The indirect relationship between LMX and OCB via perceived social impact is stronger at lower than at higher levels of PLMXD.

Similarly, the conversion of LMX into career adaptability depends on the perceived fairness of the relational environment. Career construction theory [

16,

33] posits that individuals construct vocational meaning through interpretive and interpersonal processes, particularly by observing how leaders treat others [

4]. In public-sector settings, where performance criteria are ambiguous and promotion pathways rigid, civil servants are highly attuned to cues about fairness. When PLMXD is low, civil servants can interpret their high-quality LMX relationships as legitimate developmental resources that reflect recognition of their competence and potential. This enhances their career concern, career curiosity, career confidence, and career control—the four dimensions of career adaptability [

33]. The fair and consistent treatment across the team reinforces the belief that effort and merit will be rewarded, encouraging proactive career management. Conversely, when PLMXD is high, the strong situation theory [

57] explains why LMX becomes ineffective. High differentiation signals that resource allocation is based on favoritism rather than merit, creating uncertainty about the effort–reward correlation. These fairness violations act as a powerful negative cue, creating a shared sense that relationships matter more than merit, thereby constraining the LMX-career adaptability pathway and fostering negative work attitudes [

5,

54]. Such pervasive unfairness disrupts career identity construction, even among those with high-quality LMX [

13]. The strong situational constraint suppresses the translation of relational resources into adaptive career strategies, effectively nullifying the developmental benefits of LMX. Thus, the positive effect of LMX on an employee’s career adaptability is stronger when perceived LMX differentiation is low than when it is high.

Hypothesis 5: When PLMXD is high, the positive effect of LMX on career adaptability will weaken.

Above, we propose a first-stage moderated mediation model. Because PLMXD weakens the relationship between LMX and career adaptability, the entire indirect pathway from LMX through career adaptability to performance outcomes will also be conditional on PLMXD. Specifically, when PLMXD is low, civil servants can effectively convert their high-quality LMX into stronger career adaptability, which in turn enhances task performance and OCB. When PLMXD is high, the strong negative situation undermines this conversion process, attenuating the indirect effects. Thus, Hypothesis 6 was formulated, which comprised the following:

Hypothesis 6a: The indirect relationship between LMX and task performance via career adaptability is stronger at lower than at higher levels of PLMXD.

Hypothesis 6b: The indirect relationship between LMX and OCB via career adaptability is stronger at lower than at higher levels of PLMXD.

4. Results

This study employed structural equation modeling to examine the hypothesized relationships [

82]. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using Mplus to evaluate the discriminant validity of the six constructs in the research model: LMX, PLMXD, career adaptability, perceived social impact, task performance, and OCB. The hypothesized six-factor model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (χ

2 = 463.428, df = 215, CFI = 0.964, TLI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR = 0.040).

To further assess the discriminant validity, we compared the six-factor model with a series of alternative models in which conceptually related constructs were combined. Specifically, in the five-factor model 1, task performance and OCB were combined into one factor. The four-factor model further combined career adaptability and perceived social impact on the basis of the five-factor model 1. The three-factor model combined all Time 2 variables (career adaptability, perceived social impact, task performance, and OCB) into a single factor. The two-factor model further combined all Time 1 variables (LMX and PLMXD) into one factor based on the three-factor model. The one-factor model combined all variables into a single factor.

Chi-square difference tests indicated that the six-factor model provided a significantly better fit than all the alternative models: the five-factor model 1 (Δχ2 = 16.502, Δdf = 5, p < 0.001), four-factor model (Δχ2 = 615.340, Δdf = 9, p < 0.001), three-factor model (Δχ2 = 1516.840, Δdf = 12, p < 0.001), two-factor model (Δχ2 = 2100.935, Δdf = 14, p < 0.001), and one-factor model (Δχ2 = 3648.659, Δdf = 15, p < 0.001). These results support the discriminant validity of the six-factor measurement model.

To establish discriminant validity between LMX and PLMXD, we compared the six-factor model (separating LMX and PLMXD) with the five-factor model 2 (combining them). The six-factor model fit substantially better (χ

2 = 463.428, df = 215, CFI = 0.964, TLI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR = 0.040) than the five-factor model (χ

2 = 1053.865, df = 220, CFI = 0.880, TLI = 0.862, RMSEA = 0.102, SRMR = 0.082, Δχ

2 (5) = 590.437,

p < 0.001; see

Table 2). An EFA further supported two factors (KMO = 0.875; Bartlett χ

2 = 2485.87,

p < 0.001; eigenvalues = 4.81 and 2.09; 70.1% variance), with strong pattern-matrix loadings (LMX: 0.81–0.92, avg. 0.87; PLMXD: 0.65–0.88, avg. 0.78) and no cross-loadings ≥ 0.30. Multicollinearity was not a concern (VIFs: LMX = 1.46, PLMXD = 1.18). Collectively, these results indicate that LMX and PLMXD are related but are empirically distinct constructs that warrant separate modeling.

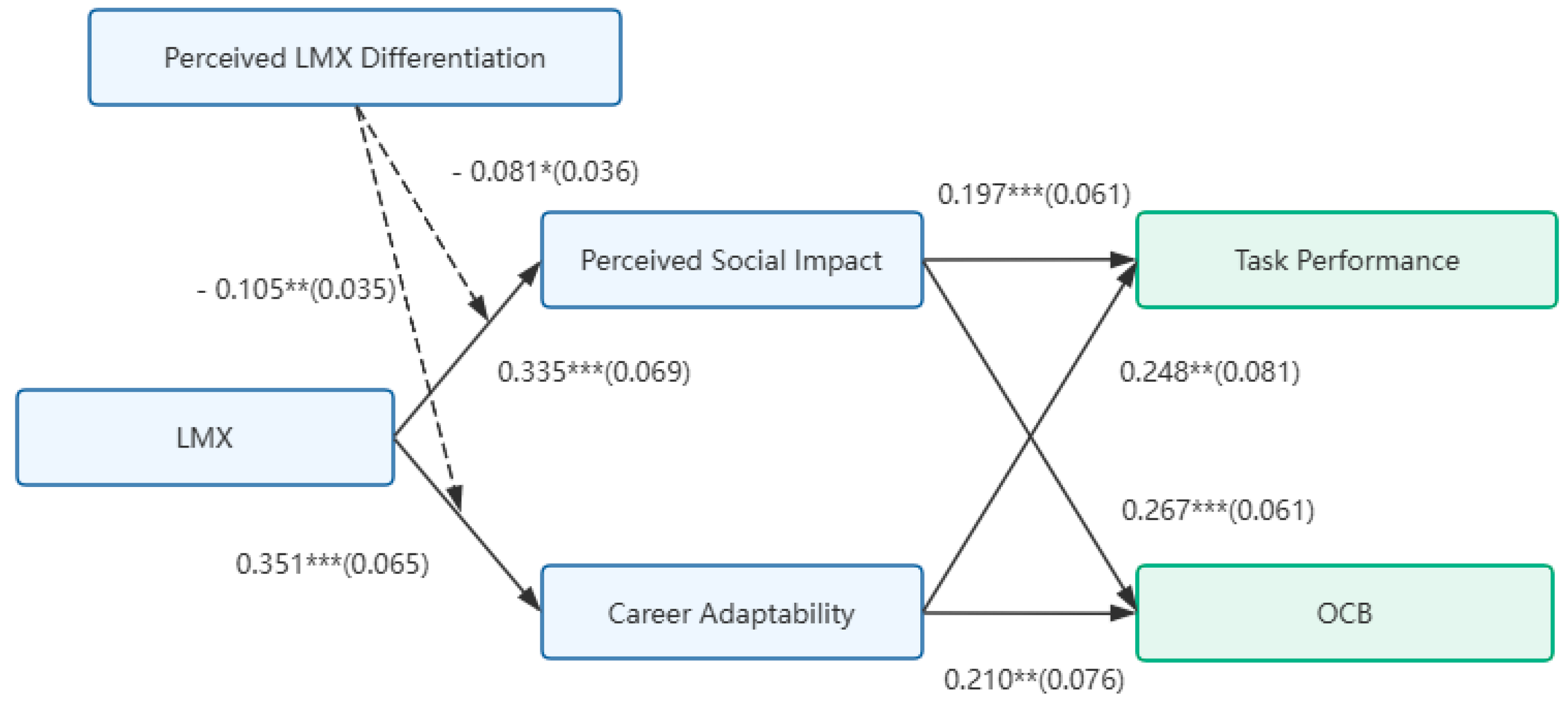

The analysis results are presented in

Figure 1 and

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6. Several relationships are statistically significant. LMX has a significant positive effect on perceived social impact (β = 0.335,

p < 0.001) and career adaptability (β = 0.351,

p < 0.001). In addition, social impact is positively associated with task performance (β = 0.197,

p < 0.001) and OCB (β = 0.267,

p < 0.001). Career adaptability is also positively associated with task performance (β = 0.248,

p < 0.01) and OCB (β = 0.210,

p < 0.01).

Hypotheses 1a and 1b concerning the mediating role of perceived social impact were tested. The results indicate that the indirect effect of LMX on task performance through perceived social impact was positive and significant [indirect effect = 0.066, 95% CI (0.026, 0.129)], and the indirect effect of LMX on OCB through perceived social impact was also positive and significant [indirect effect = 0.090, 95% CI (0.044, 0.155)]. Thus, Hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported.

Next, Hypotheses 2a and 2b concerning the mediating role of career adaptability were tested. The indirect relationship between LMX and task performance via career adaptability was positive and significant [indirect effect = 0.087, 95% CI (0.032, 0.156)], and the indirect relationship between LMX and OCB via career adaptability was positive and significant [indirect effect = 0.074, 95% CI (0.024, 0.137)]. Thus, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported.

This study further examined the moderating role of PLMXD. The regression analysis indicated that PLMXD significantly moderated the relationship between LMX and perceived social impact (β = −0.081, SE = 0.036,

p < 0.05), as well as the relationship between LMX and career adaptability (β = –0.105, SE = 0.035,

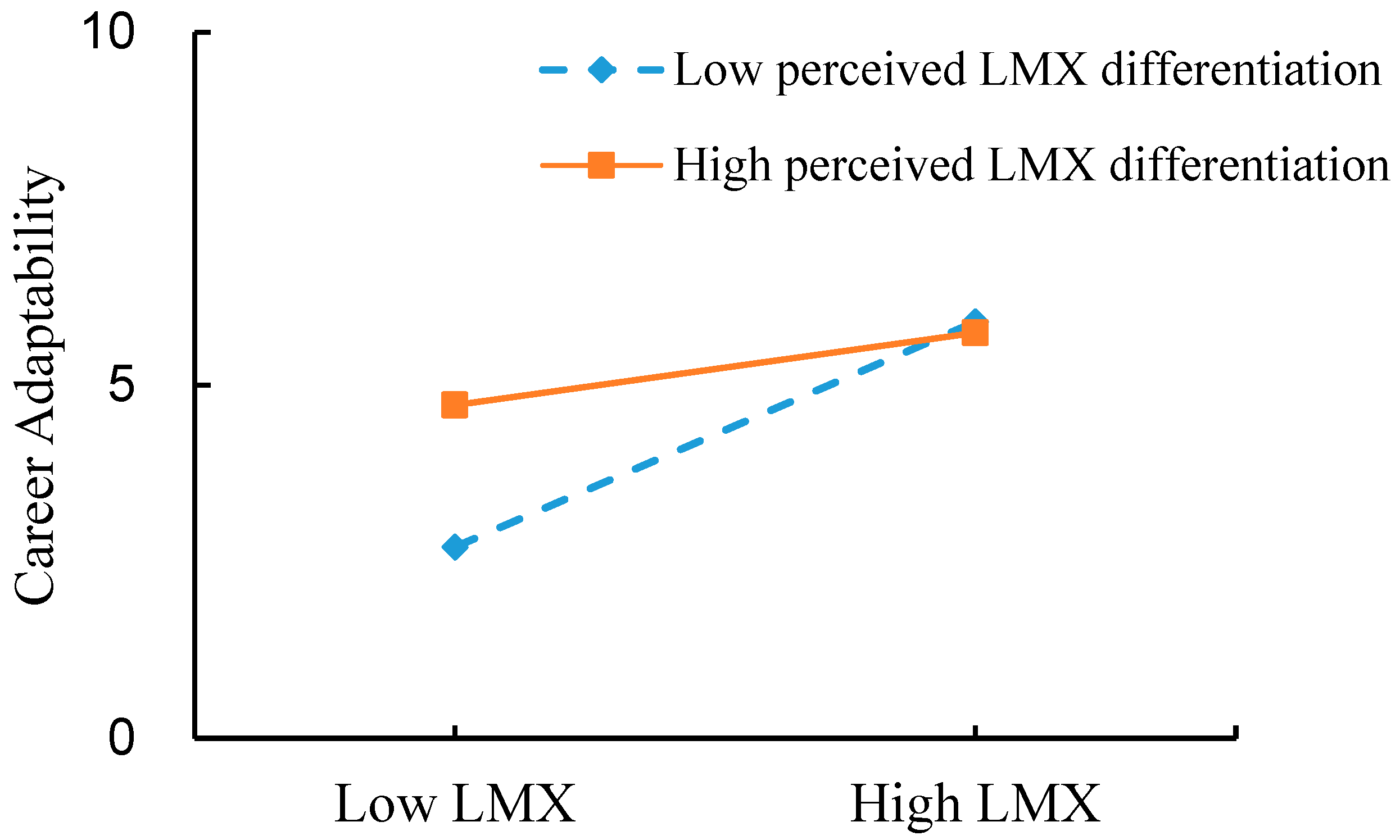

p < 0.01), supporting Hypotheses 3 and 5. To further interpret these moderation effects, simple slope analyses were conducted.

Figure 2 shows that when PLMXD was low (−1 SD), LMX significantly predicted greater perceived social impact (β = 0.474, SE = 0.113,

p < 0.001); this effect was weaker when PLMXD was high (+1 SD; β = 0.196, SE = 0.065,

p < 0.01). The slope difference was significant (Δβ = −0.278, SE = 0.123,

p < 0.05), indicating that PLMXD attenuated the positive effect of LMX on perceived social impact. Similarly, as shown in

Figure 3, the positive relationship between LMX and career adaptability was significantly weaker when LMX differentiation was high (β = 0.172, SE = 0.056,

p < 0.01) compared with when it was low (β = 0.531, SE = 0.112,

p < 0.001). The slope difference was also statistically significant (Δβ = −0.360, SE = 0.121,

p < 0.01), further indicating that PLMXD reduced the enhancing effect of LMX on career adaptability.

Finally, Hypotheses 4a, 4b, 6a, and 6b, which predicted that PLMXD moderates the indirect relationships previously revealed, were examined. Following Preacher et al.’s [

83] recommendations, the results show that the indirect effect of LMX on task performance via perceived social impact was stronger under low PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.093, 95% CI (0.038, 0.187)] than under high PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.039, 95% CI (0.010, 0.090)], and the difference between these two effects was significant [difference index = −0.055, 95% CI (−0.133, −0.016)]. Thus, Hypothesis 4a was supported.

Hypothesis 3c predicted that PLMXD moderates the indirect effect of LMX on OCB via perceived social impact. The results show that the indirect effect on OCB via perceived social impact was stronger under low PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.127, 95% CI (0.064, 0.231)] than under high PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.052, 95% CI (0.018, 0.106)], and the difference between these two effects was significant [difference index = −0.074, 95% CI (−0.167, −0.123)]. Thus, Hypothesis 4b was supported.

Hypothesis 6a predicted that PLMXD moderates the indirect effect of LMX on task performance via career adaptability. The results show that the indirect effect of LMX on task performance via career adaptability was stronger under low PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.134, 95% CI (0.075, 0.219)] than under high PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.045, ns], and the difference between these two effects was significant [difference index = −0.089, 95% CI (−0.199, −0.024)]. Thus, Hypothesis 6a was supported.

Finally, Hypothesis 6b predicted that PLMXD moderates the indirect effect of LMX on OCB via career adaptability. We found that the indirect effect of LMX on OCB via career adaptability was stronger under low PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.112, 95% CI (0.034, 0.218)] than under high PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.036, 95% CI (0.012, 0.078)], and the difference between these two effects was significant [difference index = −0.076, 95% CI (−0.173, −0.019)]. Thus, Hypothesis 6b was supported.