1. Introduction

Micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) form the backbone of Ecuador’s economy and society. They account for the vast majority of businesses and a large share of employment across all industries. For instance, MSMEs account for approximately 98% of all enterprises in Ecuador and generate more than half of the country’s jobs [

1]. In fact, there are more than six million registered business units in the country, of which over 90% are micro or small firms. Virtually every sector is dominated by these smaller companies—for example, around 98% of firms in agriculture and services are micro/small businesses, with similarly high proportions in manufacturing, construction, and commerce [

2]. MSMEs also contribute significantly to economic output, providing over a quarter of Ecuador’s GDP [

2]. This outsized presence underscores the vital role of MSMEs in fostering employment, innovation, and inclusive growth at both local and national levels.

Despite their importance, Ecuadorian MSMEs face persistent challenges that hinder their sustainability and growth. High business mortality rates are a notable concern—many new SMEs struggle to survive beyond a few years of operation [

2]. A combination of internal and external factors contributes to this fragility. Owners of MSMEs often lack formal management training and tend to operate with limited financial buffers [

2]. Structural constraints such as resource scarcity, skill gaps, and rudimentary infrastructure are typical in this segment. Access to financing remains difficult for many small firms, limiting their ability to invest in improvements. Financial fragility is a key risk factor: low liquidity, high leverage, and weak profitability significantly increase the likelihood of closure among Ecuadorian SMEs [

3]. External conditions—from economic volatility to competitive pressure—further exacerbate the vulnerabilities of MSMEs. Lacking economies of scale, these enterprises must compete by being agile and efficient, yet operational inefficiencies and outdated practices often curtail their capacity to do so.

In today’s era of rapid digital transformation, the adoption of advanced technologies and data-driven management practices is increasingly seen as a pathway for MSMEs to overcome some of these challenges. Modern tools such as business process management (BPM) systems, analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI) can help small businesses optimize operations, improve decision-making, and enhance competitiveness [

4,

5]. Studies consistently highlight that data-driven approaches offer benefits such as increased process efficiency, enhanced customer insights, and greater agility in responding to market changes [

4]. For example, streamlining workflows through data-informed BPM can reduce waste and turnaround time, directly impacting productivity and service quality. Efficient management of time and resources is especially vital for MSMEs, since these firms cannot afford inefficiencies; even simple improvements in scheduling production or deliveries can yield outsized gains in performance [

6]. There is a strong incentive, therefore, for MSMEs to leverage digital tools and methodologies to “do more with less” in competitive markets.

However, technology adoption in MSMEs remains limited in practice, as these small businesses encounter numerous barriers in implementing new systems. Research indicates that MSMEs often struggle with technological infrastructure constraints, lack of expertise, and financial hurdles when trying to digitize their processes [

3,

6]. Unlike large corporations, MSMEs typically do not possess dedicated IT departments or big budgets for technology upgrades, so they require solutions tailored to their scale and context [

4]. A recent study on artificial intelligence uptake in Ecuadorian companies illustrates the current gap: AI adoption among MSMEs is still very low and highly concentrated in a few areas (notably marketing), with minimal use in finance, logistics, or human resources. The primary obstacles hindering broader AI implementation are the shortage of qualified personnel, the scarcity of accessible and structured data, and limited financial resources for technology investment [

4]. These findings echo a broader theme: although digital tools hold great promise for improving the performance of MSMEs, realizing that potential requires overcoming significant capability gaps within these firms.

Given this context, a growing body of work has begun to examine how Ecuadorian MSMEs can navigate their transformation challenges. Scholars and practitioners are exploring strategies to boost innovation, efficiency, and resilience in this sector. For instance, recent research has analyzed the expectations of MSME owners regarding data-driven process management, revealing optimism about performance gains, as well as awareness of adoption barriers [

5]. Other studies have introduced mathematical models to improve operational scheduling in small manufacturers, aiming to maximize throughput with constrained resources [

6]. There have also been efforts to identify early-warning indicators of financial distress or closure intention, so that at-risk businesses can be supported before it is too late [

3]. Across these diverse approaches, a consensus emerges that targeted interventions are necessary to help MSMEs overcome their limitations. Indeed, experts emphasize the need for tailored support measures—such as training entrepreneurs in digital skills, improving internet and data infrastructure, and facilitating access to credit or consulting—to enable broader adoption of productivity-enhancing technologies [

4]. Strengthening the ecosystem around MSMEs in this way would not only improve individual firm outcomes but also generate positive ripple effects for employment and economic development.

In light of these insights, the present study contributes to the ongoing discussion by focusing on Ecuadorian MSMEs across all sectors and examining how they can better leverage data-driven innovations for sustainable growth. By building on prior research and analyzing current enterprise data [

1,

2], we aim to deepen our understanding of both the drivers and impediments to MSME development in the Ecuadorian context. The following sections present the results of our analysis and discuss their implications for business managers and policymakers seeking to foster a more robust and competitive MSME segment in Ecuador.

This study makes three distinct contributions. Contextually, it situates resilience in the underexplored domain of Latin American MSMEs, highlighting how institutional fragility, financial constraints, and uneven digitalization shape adaptive capacity. Theoretically, it develops a systemic model of digital organizational resilience that conceptualizes resilience as an emergent property of socio-technical entanglement, integrating insights from resilience engineering, sociomateriality, and distributed cognition. Empirically, it synthesizes evidence from Ecuadorian MSMEs [

6] to illustrate how resilience is enacted in practice, thereby bridging theoretical perspectives with real-world conditions in resource-constrained settings.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Conceptual Model

This study adopts a systemic perspective to conceptualize Digital Organizational Resilience in micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) as an emergent property of entangled socio-technical systems. In this view, resilience does not reside in isolated elements—such as human resources, technological tools, or managerial procedures—but rather in the dynamic interconnections among them [

14,

16]. Building on distributed and embodied cognition approaches [

17,

18], MSMEs are seen as collective cognitive systems in which meaning, coordination, and adaptive capacity emerge from the interplay of four interdependent dimensions:

Human factors: skills, adaptive behavior, leadership, and collective sensemaking.

Technological factors: digital infrastructure, data management, and AI-enabled tools.

Organizational factors: culture, structures, procedures, and collaborative practices.

Institutional factors: regulatory frameworks, financing mechanisms, and support ecosystems.

Together, these dimensions form an entangled system in which resilience manifests through the capacity to anticipate, absorb, and adapt to disturbances while maintaining critical functions [

7].

In line with the distinctions made in the theoretical framework, Digital Organizational Resilience in MSMEs is understood here as the emergent capacity of resource-constrained firms to anticipate, absorb, and adapt to disruptions through the dynamic entanglement of human, technological, organizational, and institutional dimensions. This working definition ensures conceptual precision by anchoring resilience in both resilience engineering and socio-technical systems theory, while tailoring it to the specific challenges of MSMEs in emerging economies.

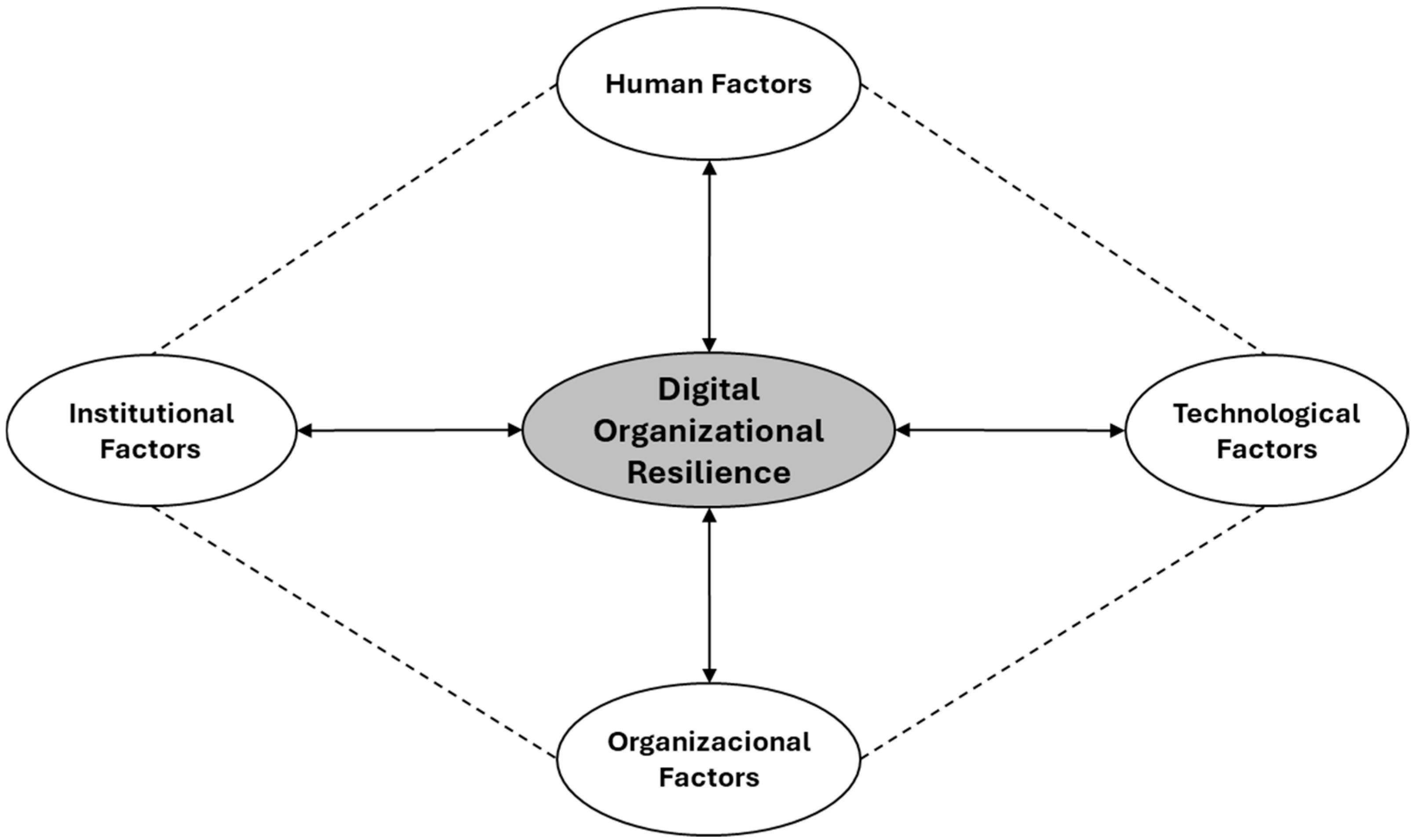

Proposed diagram. The conceptual model is represented as a quadripartite framework (

Figure 1).

Four nodes—Human, Technological, Organizational, and Institutional—are positioned around a central hub labeled Digital Organizational Resilience. Arrows between all nodes illustrate reciprocal interdependencies, while the central hub emphasizes resilience as an emergent outcome of their entanglement. Dashed lines capture cross-domain interconnections, and feedback loops indicate that adaptation is iterative and co-constructed across levels.

From a systemic and sociomaterial perspective [

14,

16], resilience is not a property of any single element, but rather it arises from the dynamic interplay among these elements. Human factors encompass adaptive skills and collective sensemaking that enable rapid responses in uncertain situations. Technological factors extend organizational capacities through data infrastructures and AI tools. Organizational factors shape decision-making via structures, cultures, and procedures. Institutional factors provide the enabling or constraining frameworks of regulation, finance, and policy.

Bidirectional arrows highlight that each dimension simultaneously contributes to and is reshaped by the central construct of resilience. For example, technological adoption influences organizational procedures, which in turn require new human skills and institutional support. The dashed interconnections among nodes emphasize this constitutive entanglement, showing that resilience is generated through multi-directional interactions rather than linear cause–and–effect relationships.

This systemic representation underscores two key insights. First, resilience in MSMEs is distributed across heterogeneous components—people, practices, technologies, and institutions—rather than located in a single domain. Second, resilience is dynamic, evolving through iterative feedback loops where disruptions trigger adaptations across domains. These insights align with recent systemic accounts of resilience, which emphasize entanglement, complexity, and simplicity as mechanisms of adaptation in complex socio-technical environments [

10,

20].

3.2. Operationalization of the Conceptual Model

To facilitate future empirical testing of the conceptual model, the four dimensions of digital organizational resilience are further specified through potential indicators.

Table 1 provides a structured summary of each dimension, including definitions and illustrative measures that could be operationalized in quantitative or qualitative studies.

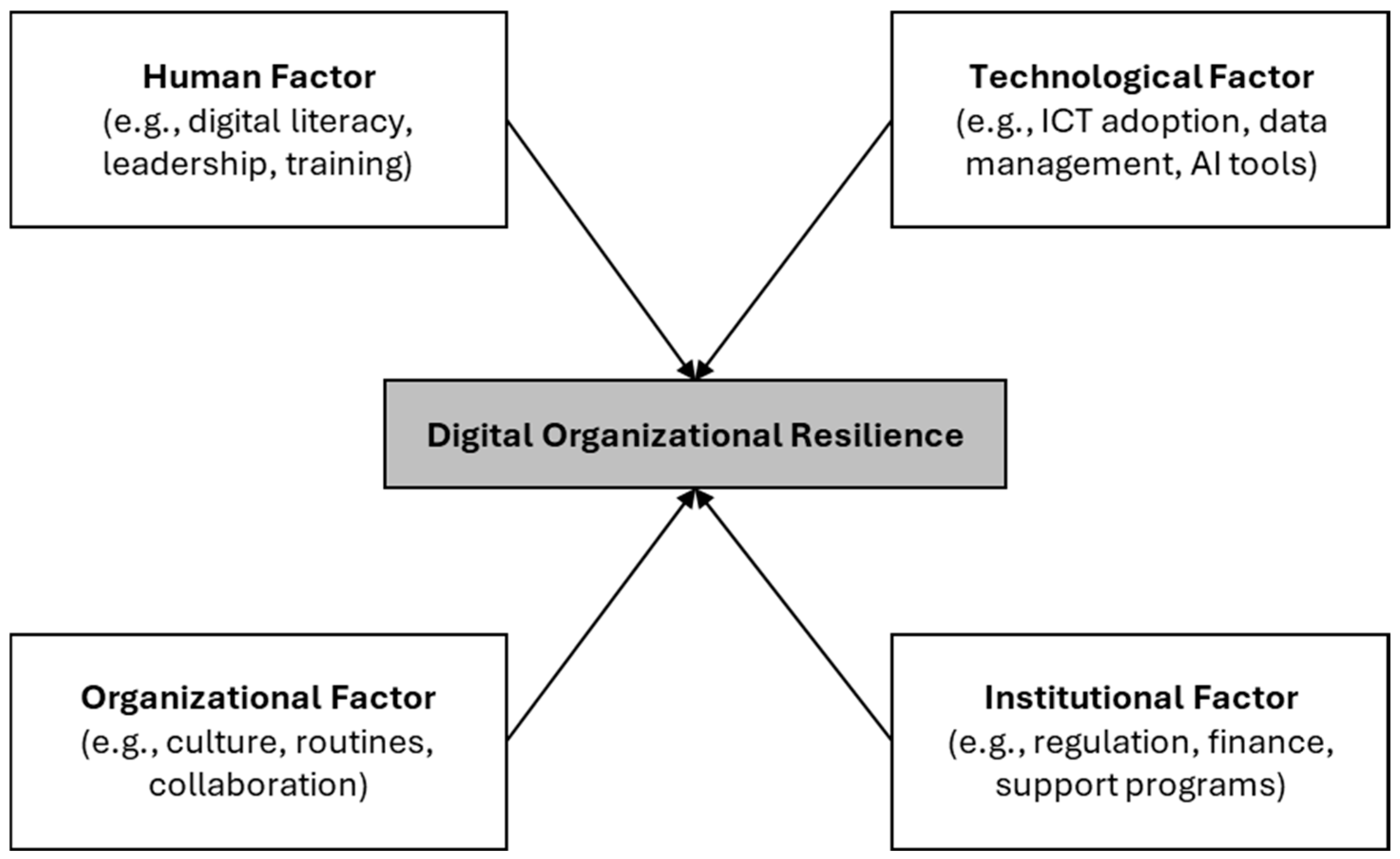

Figure 2 complements this by depicting the operational logic of the model: resilience emerges from the interaction of the four dimensions through measurable indicators, which collectively enable adaptive responses and continuity in MSMEs. This figure illustrates the operational logic of the conceptual model. Each dimension contributes specific, measurable indicators (e.g., leadership style for human factors, ICT adoption for technological factors), which interact dynamically to produce resilience outcomes. This representation emphasizes that resilience is not an abstract concept but can be empirically assessed through multidimensional indicators, thereby bridging theoretical insights with methodological applicability.

3.3. Methodological Approach

The research design is conceptual with empirical illustration. Rather than testing hypotheses through primary data collection, this study synthesizes theoretical perspectives and illustrates them with secondary evidence:

Secondary bases. Data were drawn from official statistics provided by the Ecuadorian National Institute of Statistics and Census [

1,

2] and from recent peer-reviewed studies on Ecuadorian MSMEs [

3,

4,

5,

6]. These sources provide contextual evidence on structural conditions, technological adoption, and performance challenges.

Analytical strategy. The conceptual model is elaborated through systemic synthesis, enriched with empirical illustrations from MSMEs undergoing digital transformation. This approach highlights how resilience emerges from the entanglement of socio-technical factors rather than from isolated determinants.

Illustrative case. Ecuador is examined as a representative context of Latin American emerging economies, where MSMEs dominate the economic structure but face persistent fragilities.

3.4. Scope and Limitations

The scope of this study is exploratory and illustrative. By focusing on Ecuadorian MSMEs, the analysis highlights how digital organizational resilience develops in resource-constrained, institutionally fragile environments. This case-country approach is justified by the outsized role of MSMEs in Ecuador’s economy—over 98% of enterprises and more than half of national employment [

1].

However, the reliance on secondary data and conceptual reasoning imposes limitations. The model has not been quantitatively tested, nor have its causal relationships been empirically validated. Its generalizability is therefore restricted. The contribution should be understood as theoretical with illustrative evidence, intended to guide subsequent comparative research across countries and sectors. Future studies could operationalize the framework into measurable constructs, enabling empirical testing through surveys, structural modeling, or cross-country analyses. Consequently, while the implications derived from this conceptual synthesis are necessarily broad, they are framed as theoretical guidance rather than as context-specific prescriptions, consistent with the study’s illustrative and exploratory nature.

To avoid misinterpretation, we clarify that the conceptual statements presented in

Section 2.4 are theory-driven statements derived from the conceptual framework. They are not statistically tested within this study but rather serve as conceptual anchors and guiding conceptual statements for future empirical research aimed at operationalizing and validating the model.

3.5. Data Sources and Sample

The empirical illustrations in this study are based on secondary data from the Ecuadorian National Institute of Statistics and Census [

1,

2]. The Business Directory reports over six million business units in Ecuador, of which more than 98% are classified as MSMEs. These firms account for more than half of national employment and contribute approximately one-quarter of GDP. The sample considered for illustration encompasses MSMEs across all sectors—agriculture, manufacturing, commerce, construction, and services—allowing for cross-sectoral comparisons.

All datasets used were publicly available, officially published by INEC, and complemented by peer-reviewed studies on Ecuadorian MSMEs [

3,

4,

5,

6]. These sources ensured both reliability and transparency. Data were extracted in their original formats (Excel and PDF reports) and cross-checked for consistency before analysis.

3.6. Variables and Measures

Although the study is primarily conceptual, secondary data allow the illustration of some relevant indicators:

Firm size (number of employees, following INEC classification).

Sectoral distribution (primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors).

Technology adoption (proxy variables from INEC surveys, such as internet connectivity, ICT use, and digital platforms).

Performance conditions (turnover, employment generation, survival rates). While turnover was used here as an illustrative proxy variable, we acknowledge that a wide range of external factors influences it and does not directly capture digitalization processes. More specific indicators—such as e-commerce sales (% of enterprises) or total turnover from e-commerce sales (% of turnover)—would provide a more accurate reflection of the impact of digital adoption. However, such indicators were not consistently available in the official INEC datasets employed in this study. For this reason, turnover was combined with survival rates and employment generation as contextual proxies, while we explicitly recommend the use of digital-specific indicators in future empirical research.

These variables align with the proposed conceptual framework, where technological, human, organizational, and institutional dimensions interact to shape resilience.

For transparency, the coding of indicators followed INEC’s official classifications. Firm size was coded using INEC thresholds (micro: 1–9, small: 10–49, medium: 50–199 employees). Sectoral distribution was grouped into primary, secondary, and tertiary categories based on INEC economic activity codes. Technology adoption was proxied by reported access to internet services, use of ICTs, and engagement with digital platforms. Performance conditions were illustrated using turnover, employment generation, and firm survival rates. This operationalization allows reproducibility and alignment with national statistical standards.

3.7. Procedure

The analysis proceeded in three stages. First, secondary data from INEC were extracted and organized to characterize the structural conditions of MSMEs in Ecuador. Second, descriptive statistics were employed to illustrate sectoral distributions, firm sizes, and technology adoption patterns. Third, these empirical illustrations were synthesized with insights from prior peer-reviewed research [

3,

4,

5,

6], thereby grounding the conceptual framework in contextual evidence.

No primary data collection was conducted; therefore, no ethical approval was required, as all data are publicly available through INEC. Each stage of the analysis was documented in detail to ensure transparency: (i) extraction and organization of INEC data; (ii) descriptive statistical analysis of firm size, sectoral distribution, and technology adoption; and (iii) synthesis with peer-reviewed studies [

3,

4,

5,

6] to contextualize and validate patterns. This step-by-step approach enhances methodological clarity, allowing readers to trace how empirical evidence was coded, analyzed, and integrated with the conceptual framework.

3.8. Analytical Strategy

The study applies a conceptual design with empirical illustration. The conceptual model is elaborated through systemic synthesis, while descriptive evidence from Ecuadorian MSMEs is used to ground the analysis. This strategy highlights how resilience emerges from the entanglement of socio-technical factors, rather than from isolated determinants, and illustrates the model’s applicability to real-world contexts.

To enhance methodological transparency, the integration of secondary data and theoretical insights was guided by explicit coding criteria and triangulation across sources. Indicators were consistently applied across human, technological, organizational, and institutional dimensions, ensuring that the conceptual framework was grounded in verifiable empirical evidence rather than abstract generalizations.

4. Results

4.1. Structural Profile of Ecuadorian MSMEs

The structural landscape of Ecuadorian micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) underscores their significant numerical dominance and socio-economic importance. According to the Business Directory published by INEC [

1], there are more than six million registered business units in Ecuador, of which approximately 98% fall into the MSME category. Microenterprises (1–9 employees) alone account for over 90% of all enterprises, while small firms (10–49 employees) represent a smaller yet dynamic segment, particularly in manufacturing and construction. Medium-sized enterprises (50–199 employees) are fewer in number but disproportionately significant in terms of output and formal employment generation [

2].

Sectoral distribution confirms the heterogeneity of MSMEs. In agriculture and services, microenterprises predominate, often characterized by informal practices and limited adoption of technology. Manufacturing and construction, on the other hand, display a relatively stronger representation of small and medium firms, which exhibit greater potential for formalization and productivity improvements. Commerce remains the single largest employer of MSMEs, particularly microenterprises, sustaining vast networks of self-employment and family businesses.

However, structural fragility is pervasive. High rates of early mortality affect MSMEs across all sectors, with survival beyond the first five years remaining a significant challenge [

2]. Financial vulnerabilities further exacerbate this fragility. A binomial logistic regression analysis by García-Vidal et al. [

3] shows that low liquidity, high leverage, and weak profitability are robust predictors of closure intentions. This evidence underscores that resilience cannot be understood merely in terms of technological or managerial practices but must address systemic financial fragilities that place MSMEs in a constant state of vulnerability.

4.2. Digital Adoption and Transformation Challenges

Ecuadorian MSMEs are undergoing a gradual but uneven digital transformation. While most firms report basic internet access and some level of ICT use, deeper integration of digital tools remains limited [

2]. Adoption tends to be incremental and frequently triggered by external shocks. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, small restaurants and retail shops adopted online ordering platforms and mobile payment applications to sustain sales under mobility restrictions. These low-cost tools enabled them to maintain customer engagement and ensure business continuity during a crisis. Similarly, a group of textile MSMEs integrated cloud-based inventory systems and simplified ERP modules to control stock levels and reduce material waste, thereby strengthening both efficiency and adaptability.

Evidence from Pérez-Campdesuñer et al. [

4] highlights that artificial intelligence (AI) adoption remains at an incipient stage. Marketing functions, particularly social media analytics and targeted advertising, are the most common entry points for AI. For instance, small enterprises in commerce and hospitality are increasingly using low-cost AI-enabled dashboards to adjust promotional campaigns in real-time. In contrast, areas such as logistics optimization, human resources analytics, or financial forecasting remain underdeveloped. This skewed adoption reflects a pragmatic approach in which firms prioritize visible and affordable tools, but it also underscores systemic barriers that hinder broader digitalization.

The main barriers are fourfold:

Human resources limitations. Many MSMEs lack employees with digital literacy or data management skills. Training initiatives are sporadic, and reliance on external consultants is costly.

Technological infrastructure. Limited access to high-speed internet, outdated hardware, and fragmented data systems constrain the integration of digital tools.

Financial constraints. Small firms face difficulties accessing credit lines tailored to digital investment, with banking institutions often requiring guarantees or collateral that MSMEs cannot provide.

Institutional fragility. Support programs exist but are unevenly distributed and often limited in scope. Many firms remain unaware of government or multilateral initiatives that could support digital adoption.

However, despite these barriers, there is evidence of resilience-building dynamics. García-Vidal et al. [

3] report that MSME owners perceive data-driven business process management (BPM) as a valuable tool for enhancing efficiency, even if adoption remains aspirational rather than widespread. Similarly, Pérez-Campdesuñer et al. [

6] demonstrate that mathematical optimization models applied to production scheduling in small manufacturers can yield significant improvements in throughput and resource allocation, even under severe resource constraints. These examples demonstrate that small-scale digital interventions, when integrated with human initiative and organizational practices, can yield significant improvements in both resilience and performance.

4.3. Illustration of the Conceptual Model

The findings provide empirical grounding for the conceptual model of digital organizational resilience developed in this study. Each of the four dimensions—human, technological, organizational, and institutional—finds concrete illustration in the Ecuadorian MSME context.

Human factors. Employees often lack digital competencies, which restricts firms’ adaptive potential. However, entrepreneurial leadership has emerged as a decisive factor: in artisanal firms, for example, owner-managers trained their teams in the use of shared spreadsheets and cloud platforms, which enhanced coordination and decision-making. In another case, a small agribusiness cooperative organized peer-to-peer training sessions on digital platforms, showing how resilience at the human level depends not only on technical upskilling but also on collective sensemaking practices that align digital tools with organizational objectives.

Technological factors. Digital infrastructures are generally underdeveloped; however, firms that have adopted BPM or ERP tools have reported measurable improvements in coordination and efficiency [

4]. One small furniture manufacturer, for instance, implemented a simplified ERP module that reduced stockouts and shortened delivery times by nearly 20%. In commerce, microenterprises that utilize AI-enabled dashboards to track sales have been able to adjust their pricing strategies in real-time, illustrating the catalytic role of even modest digital tools in expanding adaptive capacity.

Organizational factors. Informality in procedures and the absence of contingency planning often reduce resilience. Nevertheless, firms that engage in prototyping or mathematical optimization models provide concrete evidence of distributed cognition. For example, a group of small manufacturers applied optimization-based scheduling models [

6] not only to allocate resources efficiently but also as a shared decision-support tool that structured discussions between managers and employees. These cases demonstrate that digital artifacts serve as boundary objects, facilitating collective problem-solving and enhancing organizational adaptability.

Institutional factors. Uneven access to financing, regulatory burdens, and the limited reach of support programs constrain resilience. However, pilot initiatives demonstrate the role of institutional scaffolding. For example, a preferential credit line for digital transformation enabled microenterprises in the service sector to acquire cloud-based accounting software, improving financial transparency and compliance. Similarly, local chambers of commerce have offered digital literacy workshops that expanded entrepreneurs’ ability to adopt e-commerce platforms. These initiatives confirm that institutional supports can decisively shape organizational outcomes.

To synthesize these illustrations,

Table 2 consolidates the empirical evidence associated with each of the four dimensions of digital organizational resilience and highlights their implications. This structured overview demonstrates that resilience does not arise from isolated elements, but rather from the alignment of human, technological, organizational, and institutional factors. By mapping concrete evidence onto the conceptual framework, the table reinforces the systemic character of resilience and clarifies how entanglement manifests in practice across Ecuadorian MSMEs.

Taken together, these interdependencies validate that resilience emerges from entanglement rather than from isolated capabilities. A technologically advanced firm without skilled employees or institutional support remains fragile, just as a highly trained workforce without access to tools or credit cannot sustain resilience. The systemic nature of resilience is thus empirically observable in Ecuadorian MSMEs: adaptation requires the simultaneous interplay of human, technological, organizational, and institutional dimensions.

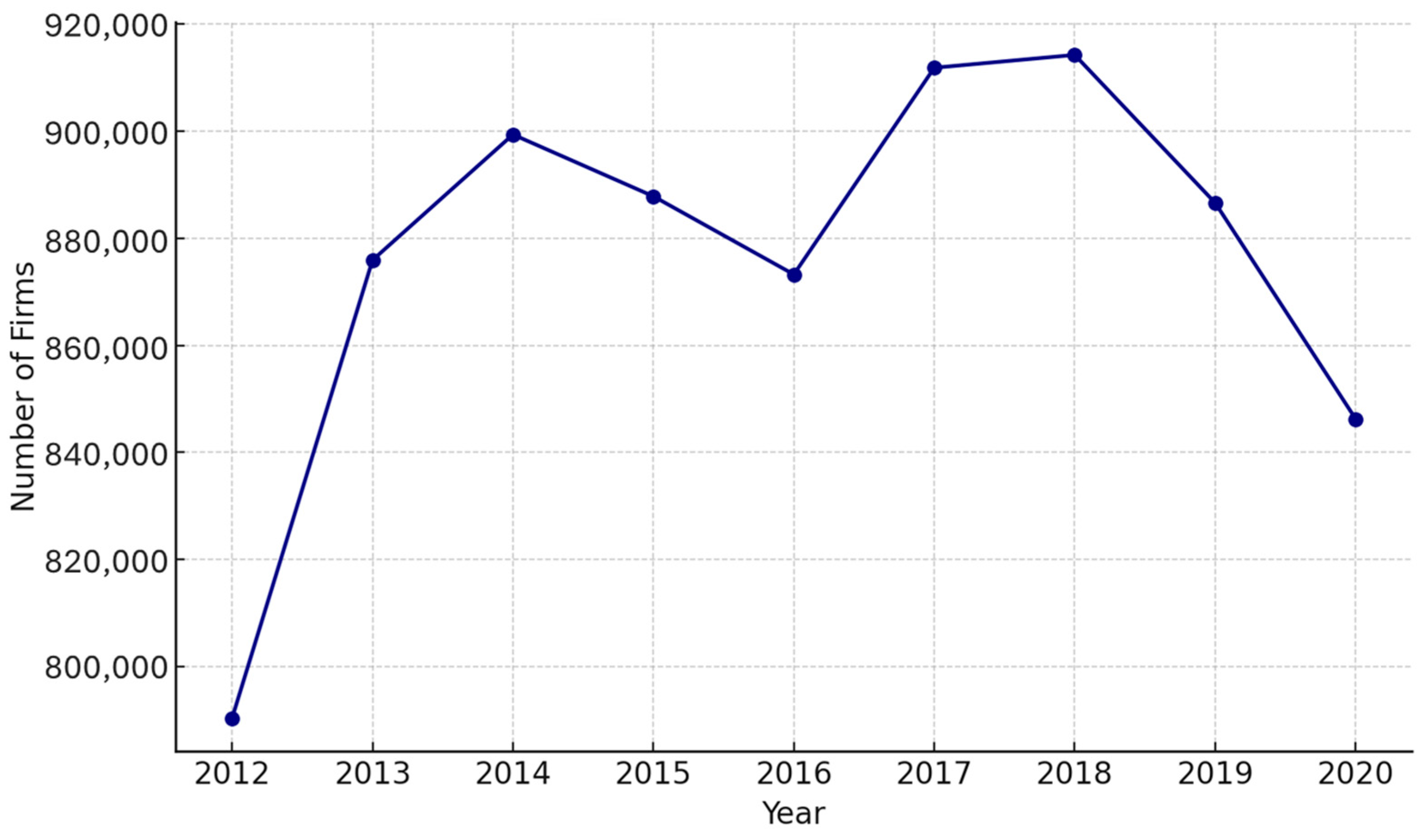

In order to illustrate the structural dynamics of the Ecuadorian business ecosystem,

Figure 3 presents the evolution of the number of firms between 2012 and 2020. The trend shows an initial expansion up to 2014, followed by a period of relative stagnation and contraction, reflecting both macroeconomic volatility and institutional fragility. This cyclical pattern highlights the vulnerability of MSMEs to external shocks, reinforcing the argument that organizational resilience must be conceptualized as a systemic property rather than an isolated managerial capability.

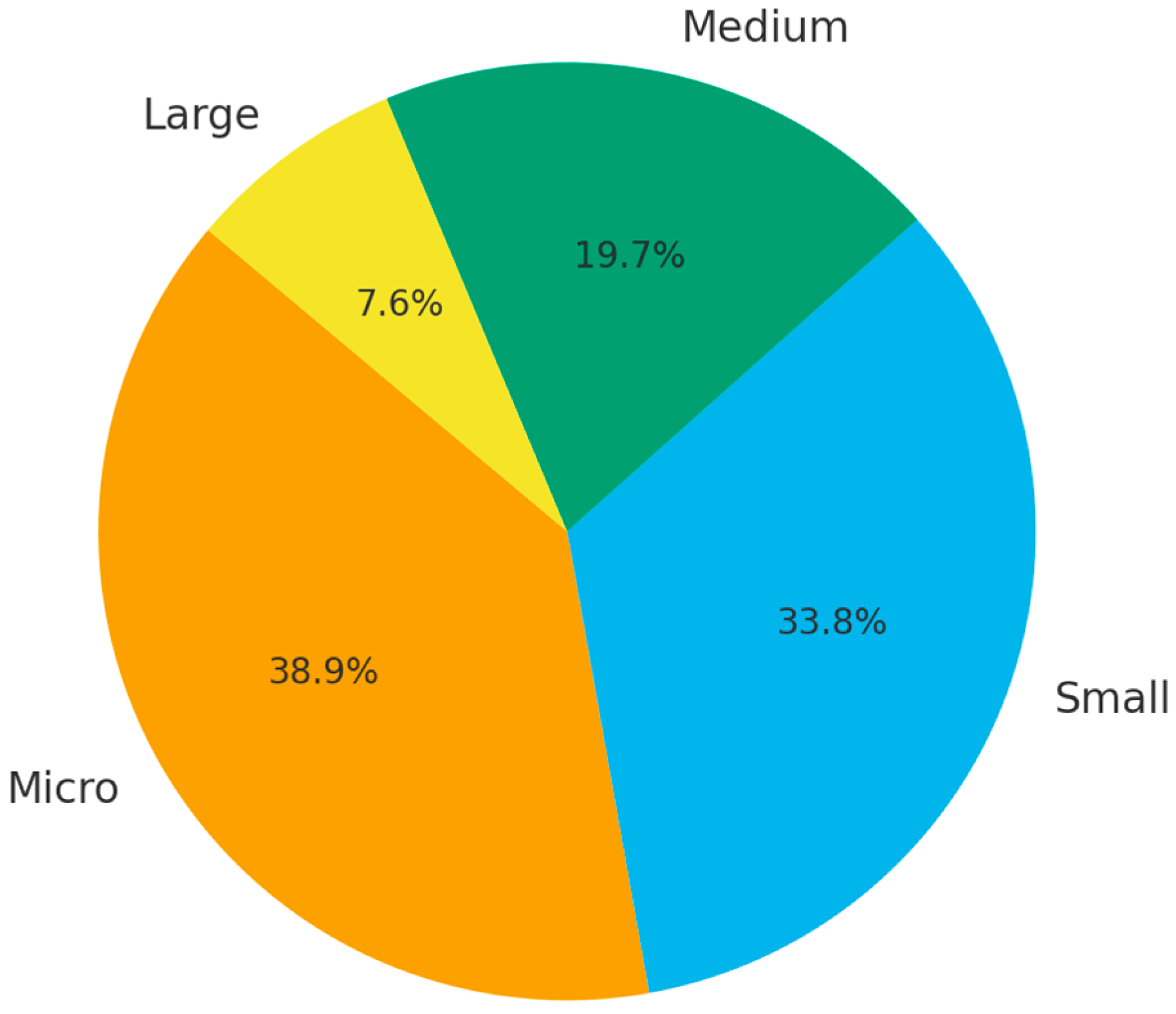

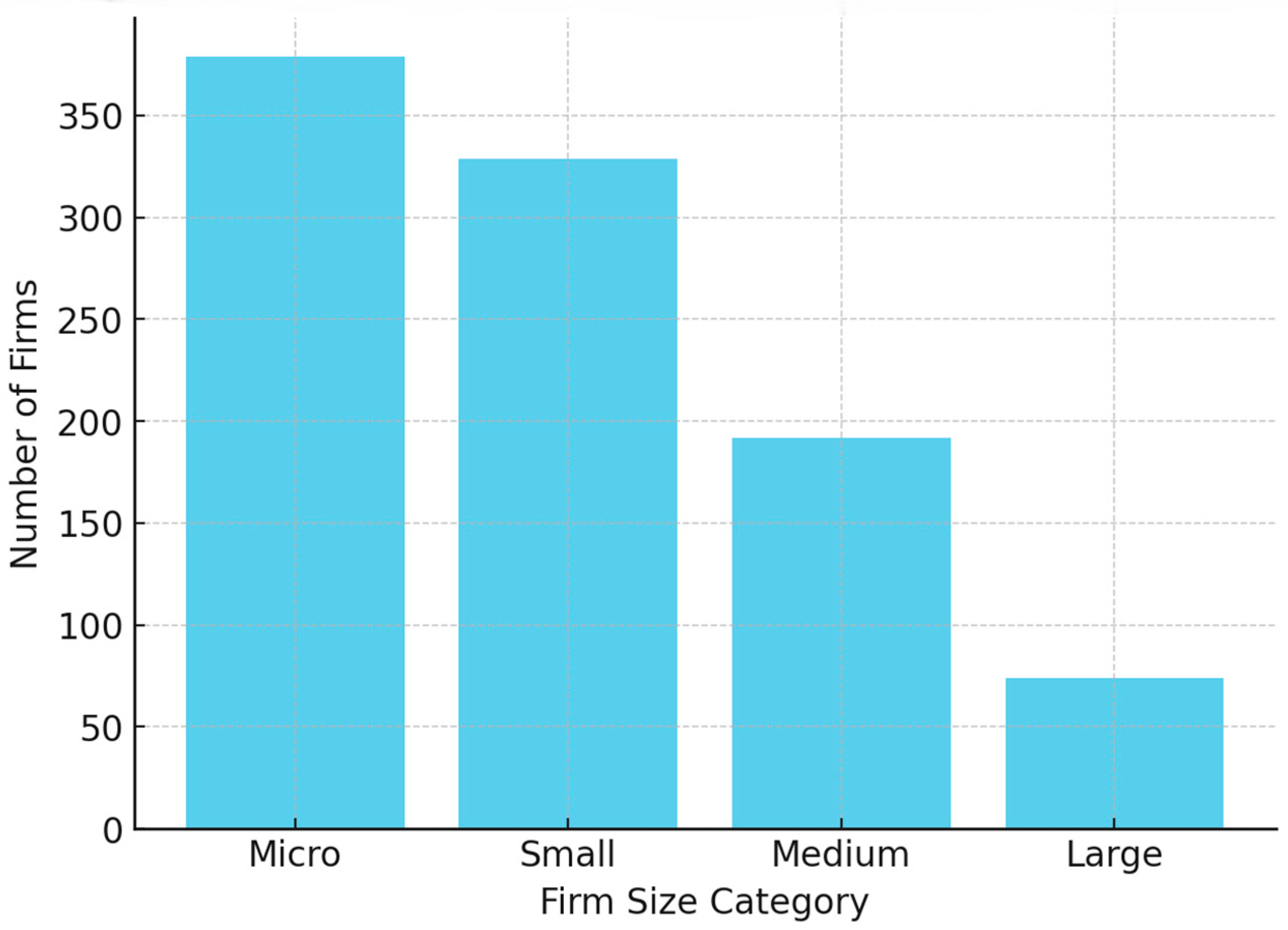

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of firms by size category using a representative sample from the GRH-PYMES dataset. The results confirm the dominance of microenterprises (39%) and small firms (34%), while medium-sized (20%) and large firms (8%) constitute a much smaller share. The overwhelming concentration of micro and small firms underscores the importance of resilience mechanisms tailored to highly resource-constrained organizations.

Complementing this,

Figure 5 presents a bar chart of the absolute number of firms (measured in enterprises, not thousands or millions) across various size categories. The visual contrast highlights not only the prevalence of microenterprises but also the crucial role of small and medium-sized firms in maintaining productive capacity. These categories collectively form the backbone of Ecuador’s economic structure yet remain disproportionately fragile in terms of financial sustainability and digital readiness.

Finally,

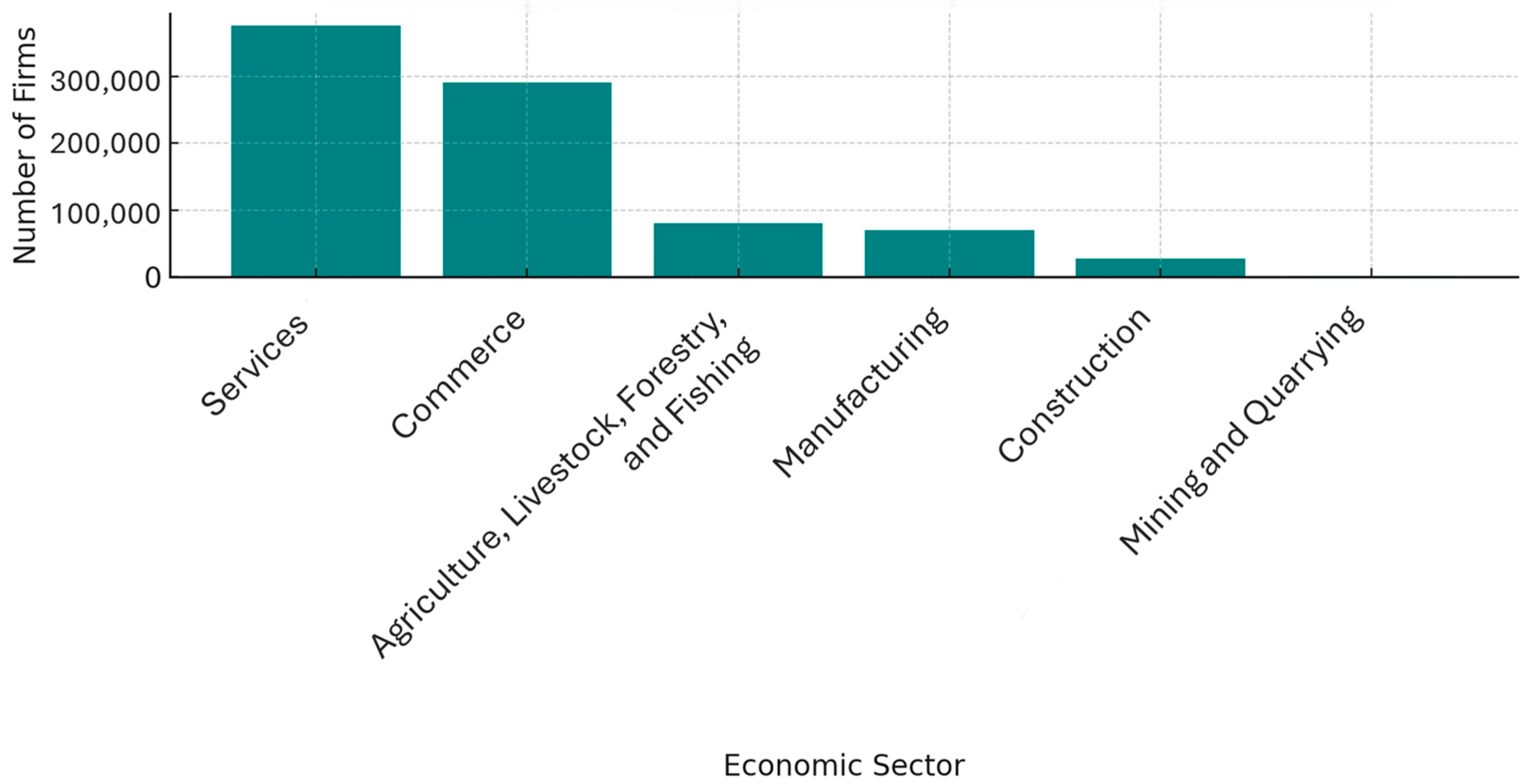

Figure 6 displays the distribution of firms by economic sector in 2020, based on data from the INEC. Services (376,000 firms) and commerce (291,000 firms) dominate, followed by agriculture (81,000 firms) and manufacturing (70,000 firms).

The concentration in low-capital, service-oriented activities helps explain both the agility and the vulnerability of Ecuadorian MSMEs: while these sectors can rapidly adapt to demand fluctuations, they often lack the technological and financial buffers necessary for long-term resilience.

5. Discussion

The results presented in this study provide empirical grounding for the conceptual model of digital organizational resilience in MSMEs as an emergent property of entangled socio-technical systems. The descriptive evidence confirms the structural dominance of micro and small firms in Ecuador [

1,

2], while also revealing their persistent fragilities, including high mortality rates, financial vulnerability, and limited digitalization [

3]. These findings align with international research, which emphasizes that resilience in SMEs is shaped not only by internal resources but also by their embeddedness in broader institutional and technological environments [

12,

13].

Comparisons with prior literature highlight both convergences and distinctive features. Consistent with Hollnagel’s resilience engineering framework [

7], Ecuadorian MSMEs demonstrate a need to enhance their adaptive capacities through anticipation, monitoring, and learning. However, the empirical evidence underscores that such capacities are constrained by institutional fragilities, which corroborates arguments by Tomassi et al. [

10] that resilience in emerging economies depends heavily on linguistic mediation and institutional scaffolding. Moreover, the uneven adoption of digital tools confirms Orlikowski’s notion of sociomaterial entanglement [

14]: technologies cannot be treated as external add-ons but are constitutive elements of organizational practices. Finally, the observed benefits of prototyping and optimization models align with the insights of Harvey [

20] and Lindquist Campana [

21] on distributed cognition and creative problem-solving, where solutions emerge through interactions with artifacts, boundary objects, and prototypes, rather than through abstract reflection alone.

Synthesis of Objectives and Conceptual Statements. In summary, the findings provide conceptual and illustrative answers to the research objectives and conceptual statements. Regarding Objective 1, the evidence indicates that natural language interfaces and fluid communication practices between people and technologies enhance coordination and adaptability, thereby providing illustrative support for Conceptual Statement 1. Similarly, Objective 2 is addressed by demonstrating prototyping, optimization models, and other shared cognitive artifacts that served as boundary objects, expanding collective sensemaking and problem-solving, thereby providing conceptual support for Conceptual Statement 2. Together, these results confirm that digital organizational resilience in MSMEs emerges from socio-technical entanglement, where linguistic mediation and distributed cognition play decisive roles in strengthening adaptive capacity. Although the conceptual statements are not statistically tested in this study, the illustrative evidence supports the theoretical model and highlights potential pathways for future empirical research.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings contribute to resilience theory by empirically grounding the entangled nature of socio-technical systems. The examples of ERP adoption, BPM integration, and optimization models confirm the central role of distributed cognition: resilience emerges not from isolated elements but from the interactions between people, practices, and data. For instance, scheduling software is not only a technical device but also a shared cognitive artifact that facilitates sensemaking and coordination among employees. This confirms Orlikowski’s [

14] view that technologies are constitutive of organizational practices and insights from Harvey [

20] and Lindquist Campana [

21], who emphasize that cognition and creativity extend through interaction with artifacts, boundary objects, and prototyping practices.

Moreover, the evidence shows that MSME resilience depends on how complexity is translated into simplicity through socio-technical arrangements. Cloud-based ERP systems encapsulate intricate data flows into user-friendly dashboards, enabling small firms with limited expertise to access actionable insights. This dynamic exemplifies how complex interdependencies can be experienced as simple, usable solutions. Theoretically, this reframes resilience not as a static attribute but as an iterative, co-enacted process shaped by heterogeneous entanglements, consistent with resilience engineering [

7], sociomaterial perspectives [

15,

16], and research on positive deviance that highlights how organizations learn resilience from unusually successful practices [

29].

In sum, the novelty of this study lies in combining a contextual contribution (Latin American MSMEs), a theoretical contribution (a systemic entanglement model of digital resilience), and an empirical contribution (synthesizing and extending findings from recent Ecuadorian MSME studies [

3,

4,

5,

6]) into an integrated framework.

Comparative perspectives further enrich this analysis. In Europe, SMEs benefit from robust institutional infrastructures, EU-wide funding programs, and relatively high levels of digital literacy, which lower the barriers to embedding advanced digital tools in resilience strategies. Studies in Asia, particularly in China and South Korea, demonstrate how robust industrial policies and technology clusters accelerate digital adoption, while also highlighting vulnerabilities related to market volatility and global supply chain dependencies. In Africa, as in Latin America, firms operate within fragile institutional environments, characterized by limited access to financing and weak digital ecosystems. Nevertheless, they often employ innovative coping mechanisms through community-based practices and informal networks.

Taken together, these comparisons reveal that while MSMEs globally rely on socio-technical entanglement to build resilience, the specific pathways through which this occurs differ. Latin American firms are particularly shaped by institutional fragility, high informality, and political volatility, which constrain formal digitalization but simultaneously encourage reliance on interpersonal trust networks and collective sensemaking practices. This situates the contribution of our study in a broader theoretical landscape: Latin American MSMEs exemplify how resilience emerges not only from technological integration but also from cultural and institutional improvisation.

5.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

For managers and policymakers, the findings highlight that enhancing MSME resilience requires integrated strategies that simultaneously strengthen human skills, technological infrastructures, organizational procedures, and institutional supports.

At the human level, capacity-building programs should prioritize basic digital literacy and collective sensemaking. For example, training entrepreneurs to use shared spreadsheets or cloud-based collaboration platforms has been shown to improve coordination and accelerate decision-making in artisanal and service firms. Such initiatives ensure that technologies are used meaningfully rather than mechanically.

At the technological level, MSMEs should be encouraged to adopt accessible digital tools that provide high impact at low cost. The adoption of simplified ERP systems by small manufacturers, which reduced delivery delays by nearly 20%, and the use of AI-enabled dashboards in hospitality firms to adjust marketing campaigns in real-time, illustrate how modest interventions can yield disproportionate benefits in efficiency and adaptability.

At the organizational level, fostering collaborative practices and prototyping cultures can expand distributed cognition and strengthen adaptive problem-solving. Optimization models used in small manufacturing firms served not only to allocate resources efficiently but also as shared decision-support tools that structured dialogue between managers and employees. Such examples highlight the role of digital artifacts as boundary objects that translate abstract data into actionable strategies, echoing how exceptionally safe healthcare practices have been shown to emerge through collective sensemaking and distributed responsibility [

30].

At the institutional level, targeted policies are crucial for overcoming systemic constraints. Preferential credit lines for digital investments, combined with technical assistance, have enabled microenterprises to acquire cloud-based accounting software and enhance their compliance. Similarly, digital literacy workshops offered by chambers of commerce have expanded entrepreneurs’ ability to leverage e-commerce platforms. These interventions confirm that institutional scaffolding is decisive for sustaining long-term transformation, similar to how external actors can “reach in” to reinforce organizational resilience in healthcare systems [

31].

In practical terms, these examples demonstrate that resilience in MSMEs is not achieved solely by investing in technology, but by cultivating the socio-technical entanglement of people, practices, and data. Managers should view digital tools as catalysts for collaboration and learning, while policymakers should design support programs that integrate financing, training, and infrastructure to facilitate this process. Strengthening these entanglements can transform structural fragility into adaptive capacity, enabling MSMEs in emerging economies to thrive despite systemic vulnerabilities.

At the institutional level, targeted policies are crucial for overcoming systemic constraints. Preferential credit lines for digital investments, combined with technical assistance, have enabled microenterprises to acquire cloud-based accounting software and enhance their compliance. Similarly, digital literacy workshops offered by chambers of commerce have expanded entrepreneurs’ ability to leverage e-commerce platforms. These interventions confirm that institutional scaffolding is decisive for sustaining long-term transformation.

From a comparative lens, the Latin American case also underscores what is distinctive and potentially generalizable. Whereas European and Asian SMEs often scale resilience through strong state-backed digital infrastructures and innovation clusters, Latin American MSMEs must adapt under resource scarcity, fragmented policy frameworks, and recurrent institutional instability. These constraints underscore the need for context-sensitive support programs that integrate financing, digital literacy, and organizational upskilling. At the same time, the strong role of community-based collaboration and trust networks in Latin America suggests a transferable lesson: resilience is not only about technological sophistication but also about leveraging cultural and social capital to sustain adaptation under uncertainty.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study is exploratory and illustrative, relying primarily on secondary data from INEC and prior peer-reviewed studies. As such, the conceptual model has not been empirically tested through quantitative methods. The findings should therefore be interpreted as theoretical insights supported by descriptive evidence, rather than as causal claims.

Future research should operationalize the proposed indicators of digital organizational resilience into measurable constructs and test them empirically through surveys, structural equation modeling, or longitudinal analyses. Comparative studies across different Latin American countries could further illuminate how institutional contexts shape resilience dynamics. Additionally, qualitative case studies could explore how MSMEs enact resilience in real time, particularly in moments of crisis, providing richer insights into the role of distributed cognition and entangled socio-technical systems.

Future research should also consider the strategic role of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and big data in strengthening digital organizational resilience. Recent studies have highlighted that these tools not only improve performance but also contribute to sustainable outcomes and effective enterprise monitoring systems. For example, Fonseca et al. [

32] propose a framework leveraging AI (specifically ChatGPT) for SMEs to align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, while Pigola et al. [

33] illustrate how AI-driven digital technologies can advance sustainability agendas in Brazil and Portugal. Similarly, Badghish and Soomro [

34] demonstrate how AI adoption enhances operational and economic performance in SMEs, with sustainability implications. In addition, Kgakatsi et al. [

35] demonstrate that the adoption of Big Data in SMEs leads to improvements in operational efficiency and revenue growth, while Kannan and Gambetta [

36] highlight how technology-driven approaches facilitate the integration of sustainability in SMEs. Incorporating these perspectives would enrich future empirical tests of our model, clarifying how advanced digital technologies can complement socio-technical entanglement to enhance resilience, sustainability, and adaptive capacity in MSMEs.

Overall, the current version explicitly acknowledges that the empirical–theoretical linkage remains preliminary; the framework is intended as a foundation for subsequent empirical validation rather than as a thoroughly tested model.

6. Conclusions

This study developed and illustrated a systemic framework for understanding digital organizational resilience in MSMEs as an emergent property of entangled socio-technical systems. By integrating insights from distributed and embodied cognition, sociomateriality, and resilience engineering, the model demonstrates that resilience is not located in isolated elements—such as leadership, technologies, or procedures—but arises from their dynamic interplay.

The empirical evidence from Ecuadorian MSMEs highlights three main findings. First, structural fragility remains a persistent challenge: micro and small firms dominate the economic landscape yet suffer from high mortality rates and financial vulnerability. Second, digital transformation is progressing unevenly. While most firms have basic ICT infrastructure, the adoption of advanced tools, such as BPM, ERP, and AI, remains limited due to significant barriers in human capabilities, financing, and institutional support. Third, illustrative cases confirm that modest digital interventions—such as optimization models or collaborative prototyping—can generate disproportionate improvements in efficiency and adaptability, reinforcing the systemic and distributed nature of resilience.

The principal contribution of this study lies in bridging theoretical insights and empirical illustrations to conceptualize MSMEs as entangled socio-technical systems. This approach advances organizational theory by highlighting the role of distributed cognition, complexity, and simplicity in shaping adaptive capacity. Practically, it underscores the need for integrated strategies that simultaneously address human, technological, organizational, and institutional dimensions to strengthen resilience in resource-constrained environments.

Overall, the research provides a conceptual and empirical foundation for future studies to operationalize and test digital organizational resilience. By framing MSMEs as living socio-technical ecosystems, this study contributes to the broader literature on resilience, organization, and entangled systems, offering valuable insights for both scholars and practitioners seeking to foster sustainable and adaptive business models in emerging economies.