Research on the Effect of Common Institutional Ownership on Corporate Environmental Responsibility Disclosure: A Performance Feedback Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Common Institutional Ownership and Corporate Environmental Responsibility Information Disclosure

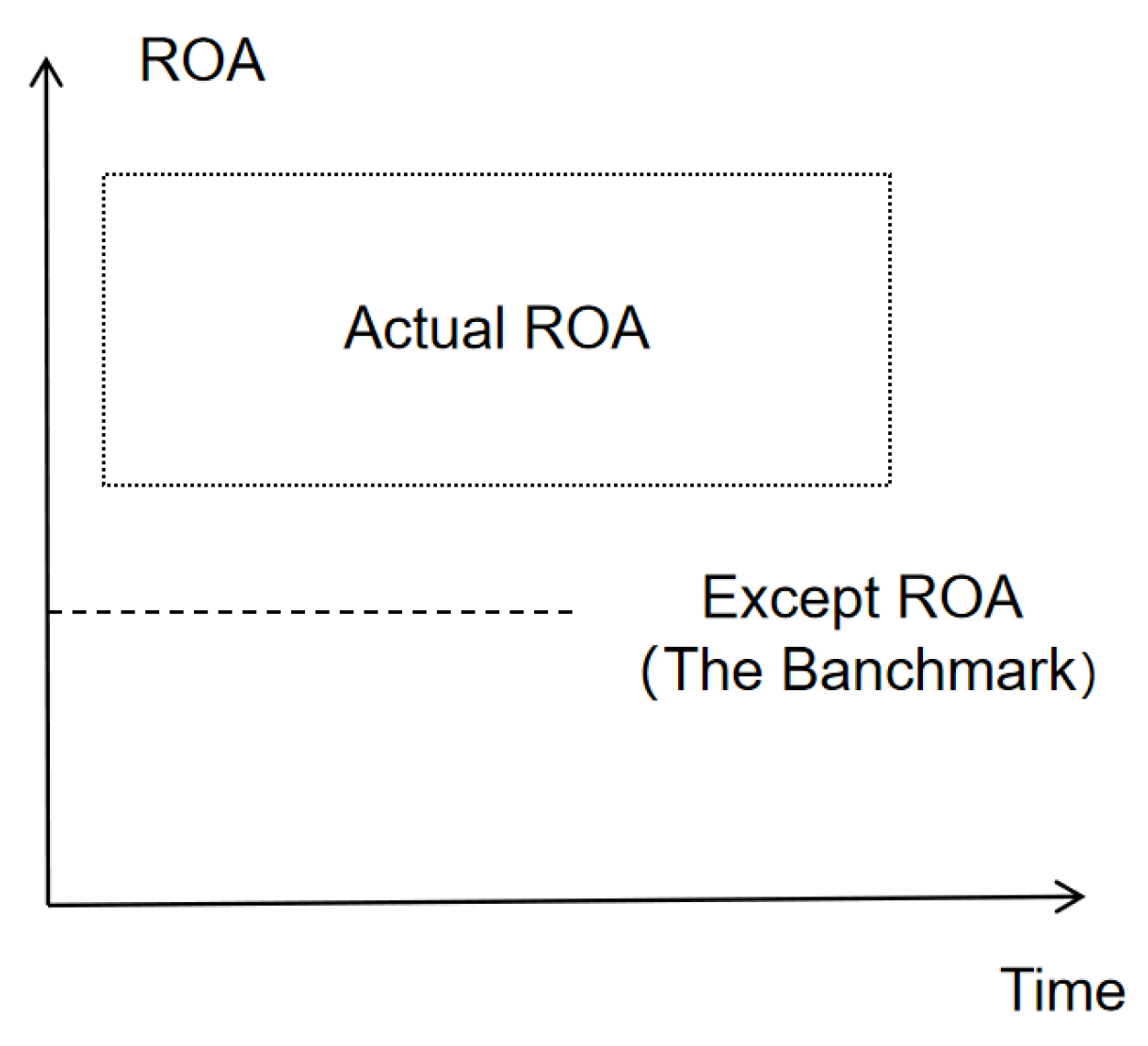

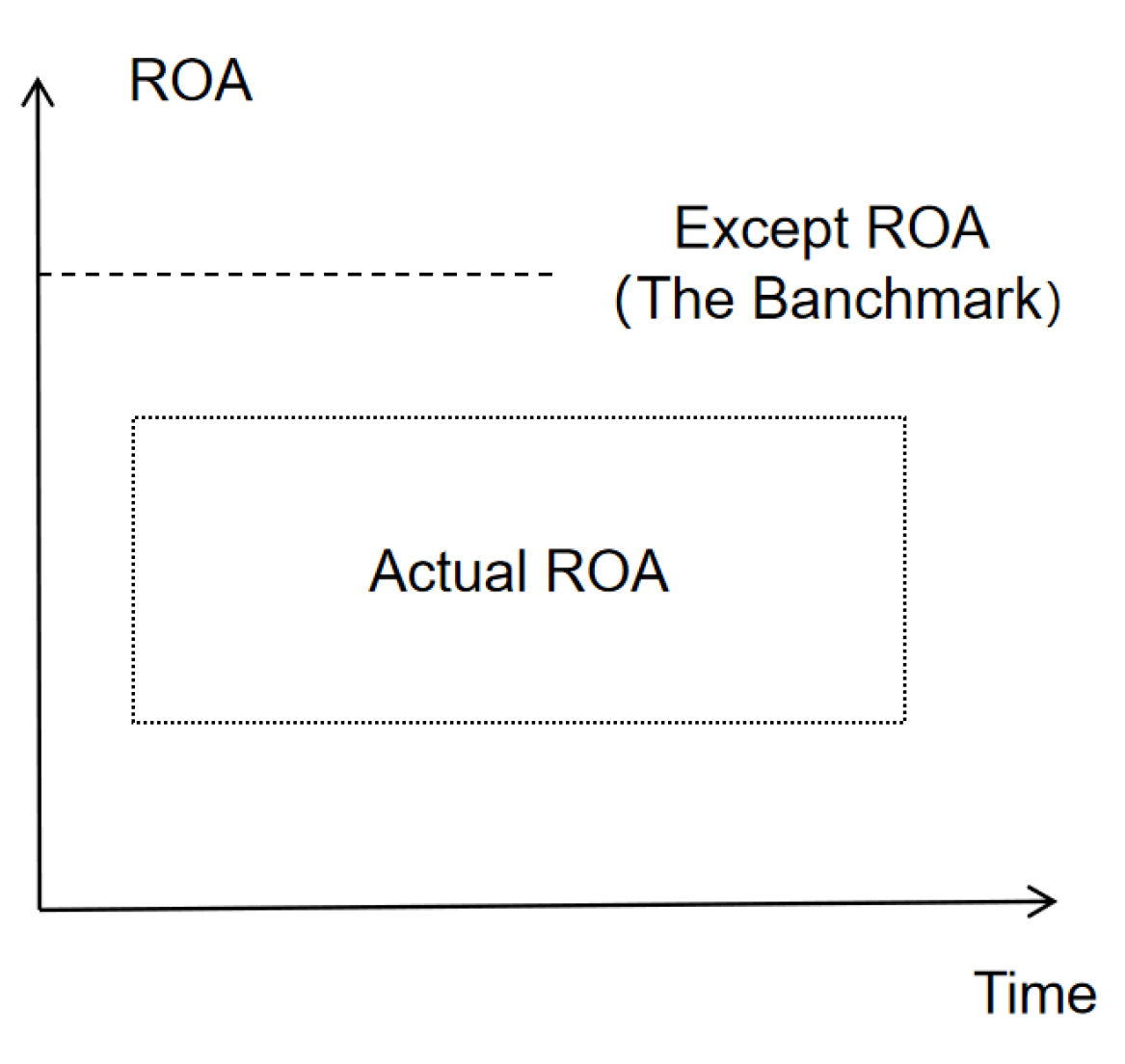

2.2. Strategic Behavior of Common Institutional Ownership at Different Expected Performance Levels

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Size

3.2. Variable Measurement

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Mechanism Test Variable

3.2.4. Grouping Variables

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Model Specification

4. Empirical Research and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Test

4.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

4.3.1. Common Institutional Ownership and Corporate Environmental Responsibility Disclosure

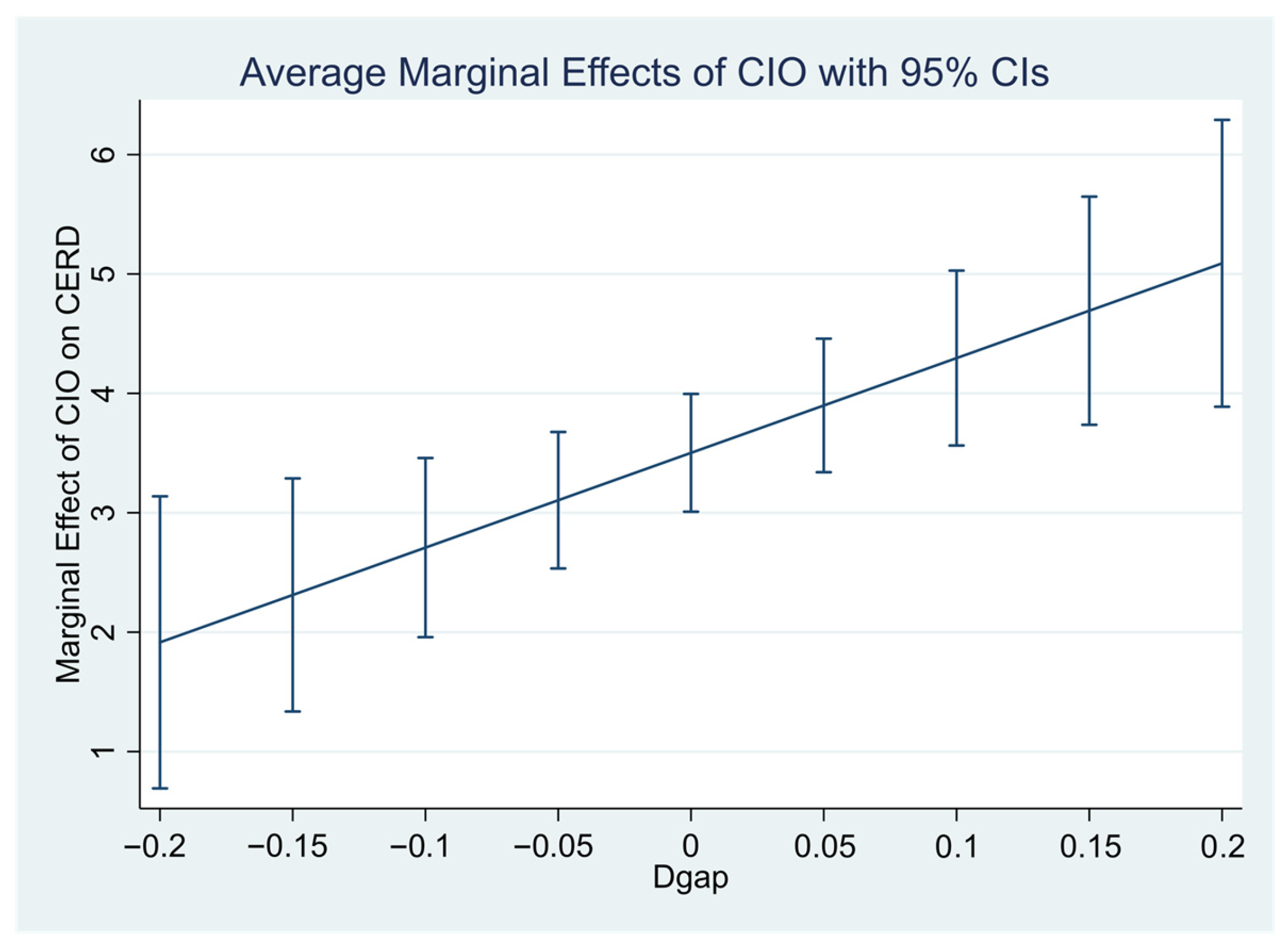

4.3.2. Expected Performance Gaps, Common Institutional Ownership and CIO

4.4. Robustness Test

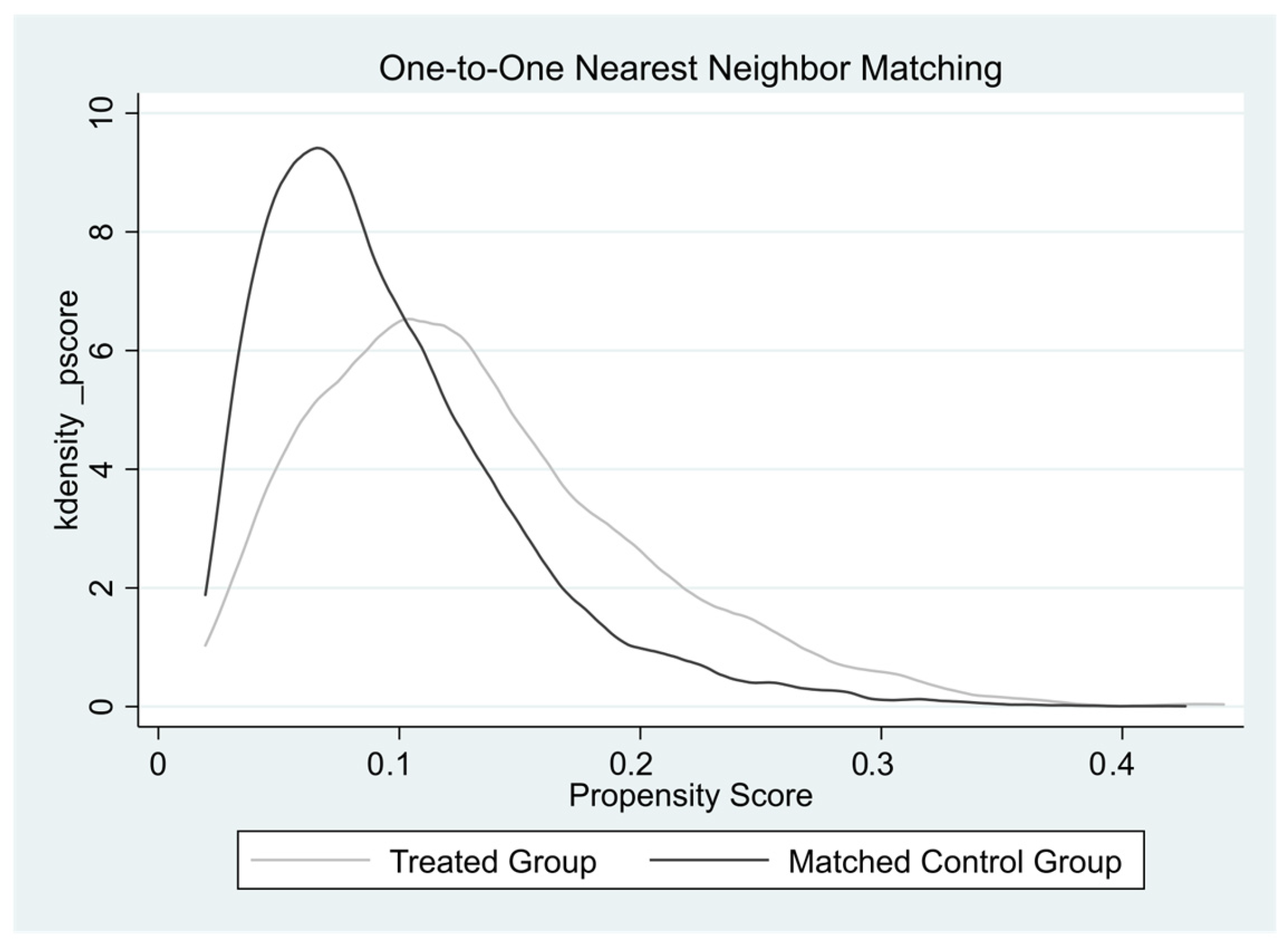

4.4.1. Endogeneity Test

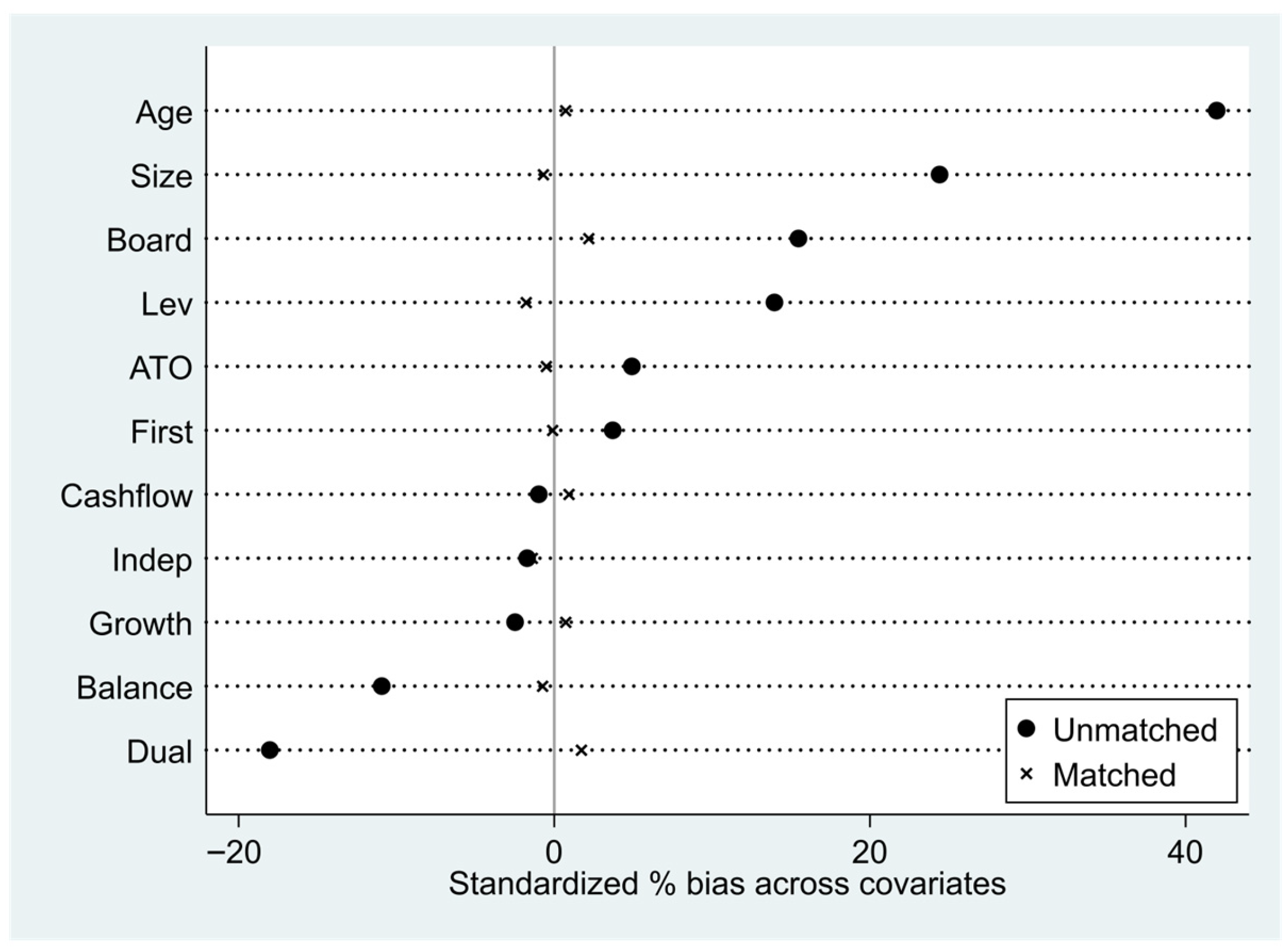

PSM-OLS Test

PSM-DID Test

Instrumental Variables

The Independent Variables Lagged by One Period

4.4.2. Testing for the Alternative Dependent Variables

4.4.3. Testing for Alternative Grouping Variable

Results for Different Values of

Results for Alternative Historical Performance Expectation Measures

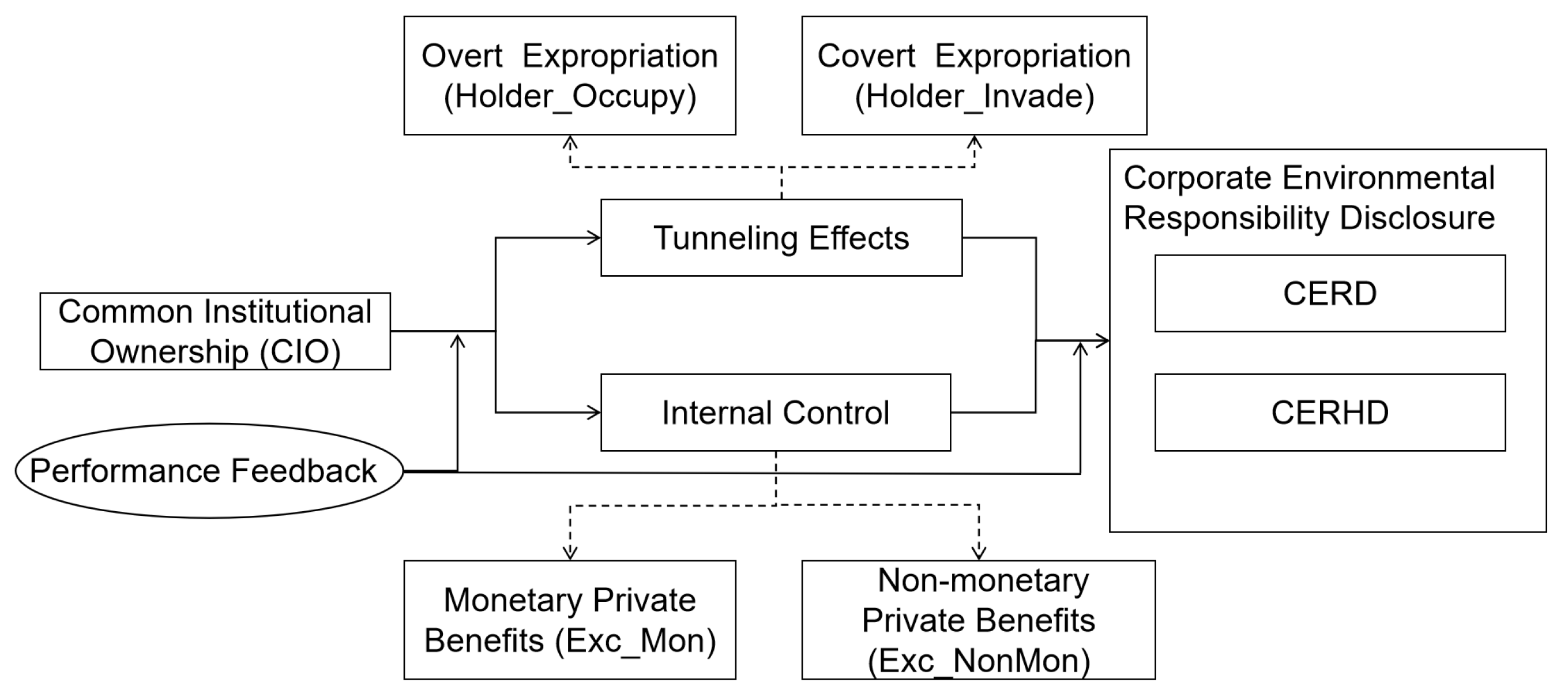

5. Mechanism Test

5.1. Supervision Effect

5.2. Synergistic Effect

5.3. Impact Pathway

6. Heterogeneity Test

7. Conclusions and Implications

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| CERD Indicator | Example | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Hard Disclosure | “In 2021, the company’s self-generated electricity, including that from waste heat power generation and photovoltaic power generation, reached nearly 400 million kilowatt-hours, which is equivalent to a reduction of more than 360,000 tons of carbon dioxide emissions.” | 2 |

| “The environmental protection investment for this year is 518,369.621 thousand yuan, of which the annual environmental protection investment of key pollutant-discharging enterprises is 459,145.278 thousand yuan.” | 2 | |

| “Sulfur dioxide: 37,328 tons per year” | 2 | |

| Soft Disclosure | “The company advocates and implements the concept of ecological environmental protection, strengthens energy conservation and environmental protection efforts, implements the ISO14001 environmental management system, and has obtained the certification.” | 1 |

| “During the project construction period, the construction of pollution prevention and control facilities shall be carried out in strict accordance with the requirements of the project’s “Three Simultaneities” principle, and these facilities shall be put into production and use simultaneously with the main project.” | 1 | |

| “The company fulfills its mission of ‘creating sustainable value for society’ and focuses on its responsibility performance initiatives carried out in four key areas: ‘responsible governance, addressing climate change, supporting global logistics, and demonstrating corporate care’.” | 1 |

References

- Van den Bergh, J.C. Environment versus growth—A criticism of “degrowth” and a plea for “a-growth”. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; Su, Y. Digital Financial Inclusion, Analyst Attention, and the Green Innovation in Energy Firms. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.J.; Huang, J.; Zhao, S. Internalizing governance externalities: The role of institutional cross-ownership. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 134, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Yuan, W. Research on the Influence of Chain Shareholder Network on Enterprise Green Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Ng, J.; Wang, C. Corporate financing of investment opportunities in a world of institutional cross-ownership. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 69, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewellen, K.; Lowry, M. Does common ownership really increase firm coordination? J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 141, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, T.; Taylor, L.A. Common ownership and innovation efficiency. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 147, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, J.; Schmalz, M.C.; Tecu, I. Anticompetitive effects of common ownership. J. Financ. 2018, 73, 1513–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Shen, H.; Gao, X.; Chan, K.C. The power of sharing: Evidence from institutional investor cross-ownership and corporate innovation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2019, 63, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, L.; Yeung, P.E. Two Tales of Monitoring: Effects of Institutional Cross-Blockholding on Accruals; University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.K.; Luo, J.; Na, H.S. Are institutional investors with multiple blockholdings effective monitors? J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 128, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Guo, X.; Sensoy, A.; Goodell, J.W.; Cheng, F. Collusion or Governance? Common Ownership and Corporate Risk-taking. Corp. Gov. 2024, 32, 645–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, J.; Vives, X. General equilibrium oligopoly and ownership structure. Econometrica 2021, 89, 999–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Huang, Y.; Peng, M.W.; Zhuang, G. Resources, aspirations, and emerging multinationals. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 2016, 23, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzaneque, M.; Rojo-Ramírez, A.A.; Diéguez-Soto, J.; Martínez-Romero, M.J. How negative aspiration performance gaps affect innovation efficiency. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Q. Technological choices under uncertainty: Does organizational aspiration matter? Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Mao, X.; Chen, X. Institutional investors’ attention to information, trading strategies, and market impacts: Evidence from China. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woidtke, T. Agents watching agents?: Evidence from pension fund ownership and firm value. J. Financ. Econ. 2002, 63, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.P.; Song, X.; Zheng, K. Do large shareholders collude with institutional investors? Based on the data of the private placement of listed companies. Phys. A 2018, 508, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A.; Holderness, C.G. Blockholders: A survey of theory and evidence. In The Handbook of the Economics of Corporate Governance; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 541–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.D.; Koch, A.; Michenaud, S. Institutional investor cliques and governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 133, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assenza, S.; Gómez-Gardeñes, J.; Latora, V. Enhancement of cooperation in highly clustered scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. E 2008, 78, 017101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoux, M.; Lusseau, D. Network modularity promotes cooperation. J. Theor. Biol. 2013, 324, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Panayides, M.; Thomas, S. Common ownership and competition in product markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 139, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingegowda, S.; Utke, S.; Yu, Y. Common institutional ownership and earnings management. Contemp. Account. Res. 2021, 38, 208–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; He, L.; Zhang, T. Common institutional ownership and investment efficiency: Empirical evidence from China. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2023, 23, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A.; Levit, D.; Reilly, D. Governance under common ownership. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 2673–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Sani, J.; Shroff, N.; White, H. Disclosure incentives when competing firms have common ownership. J. Account. Econ. 2019, 67, 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Huang, J. Product market competition in a world of cross-ownership: Evidence from institutional blockholdings. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2017, 30, 2674–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, Y. Institutional cross-ownership and corporate strategy: The case of mergers and acquisitions. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 48, 187–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kini, O.; Lee, S.; Shen, M. Common institutional ownership and product market threats. Manag. Sci. 2023, 70, 2705–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerged, A.M.; Beddewela, E.; Cowton, C.J. Is corporate environmental disclosure associated with firm value? A multicountry study of Gulf Cooperation Council firms. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Pei, H. Social determinants of sustainability: The imprinting effect of social class background on corporate environmental responsibility. Corp. Soc. Resp. Env. Ma. 2020, 27, 2849–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lian, G.; Xu, A. How do ESG affect the spillover of green innovation among peer firms? Mechanism discussion and performance study. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Pan, Z.; Janardhanan, M.; Patel, I. Relationship analysis between greenwashing and environmental performance. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 7927–7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 363–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.R. A behavioral theory of R&D expenditures and innovations: Evidence from shipbuilding. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M. Corporate environmental disclosure strategies: Determinants, costs and benefits. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 1999, 14, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhao, C.; Cho, C.H. Institutional transitions and the role of financial performance in CSR reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Patel, P.C. Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: Behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 976–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M.; Mammen, J.; Luger, J. Sell-offs and firm performance: A matter of experience? J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1359–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, K.Z.; Du, F. Deviant versus aspirational risk taking: The effects of performance feedback on bribery expenditure and R&D intensity. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 1226–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Gulzar, M.A.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X. The effect of expected financial performance on corporate environmental responsibility disclosure: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 37946–37962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.A.; Westerfield, R.; Jordan, B.C. Fundamentals of Corporate Finance; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bhojraj, S.; Hribar, P.; Picconi, M.; McInnis, J. Making sense of cents: An examination of firms that marginally miss or beat analyst forecasts. J. Financ. 2009, 64, 2361–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Org. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, Y. Can voluntary environmental regulation promote corporate technological innovation? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, J. An evaluation of environmental disclosures made in corporate annual reports. Account. Org. Soc. 1982, 7, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Lemmon, M.L.; Roberts, M.R.; Zender, J.F. Back to the beginning: Persistence and the cross-section of corporate capital structure. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1575–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, U.; Tate, G.; Yan, J. Overconfidence and early-life experiences: The effect of managerial traits on corporate financial policies. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 1687–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Hope, O.; Thomas, W.B.; Zou, Y. Blockholder exit threats and financial reporting quality. Contemp. Account. Res. 2018, 35, 1004–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qu, J.; Zhao, Z.C.; Ding, L.L. Organizational Performance Aspiration Gap and Heterogeneous Institutional Investor Behavior Choices: Double Principal-agent Perspective. J. Manag. World. 2020, 36, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.F.; Wu, S.N.; Wen, F. Managerial power, private income and compensation rigging. Econ. Res. J. 2010, 11, 73–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Disclosed Item | Indicator | Score | Disclosed Item | Indicator | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Investment | Total Environmental Investment | 0/2 | Environmental Status | Completion of “Three Simultaneities” | 0/1 |

| Pollution Fee/Environmental Tax | 0/2 | Emergency Environmental Incidents | 0/1 | ||

| Environmental Costs | Energy Consumption per Ten Thousand Yuan of Production | 0/2 | Environmental Violations | 0/1 | |

| Total Standard Coal Consumption | 0/2 | ISO14001 Certification [53] | 0/1 | ||

| Environmental Revenue | Environmental Awards | 0/1/2 | ISO9001 Certification | 0/1 | |

| Environmental Liabilities | Wastewater Discharge | 0/2 | Implementation of Clean Production | 0/1 | |

| CO2 Emissions | 0/2 | Disclosure of Social Responsibility Report | 0/1 | ||

| SO2 Emissions | 0/2 | Disclosure of Environmental Responsibility Report | 0/1 | ||

| COD Emissions | 0/2 | Voluntary Environmental Actions | Corporate Environmental Philosophy | 0/1 | |

| Dust and Particulate Emissions | 0/2 | Corporate Environmental Goals | 0/1 | ||

| Industrial Solid Waste | 0/2 | Establishment of Environmental Management Systems | 0/1 | ||

| Environmental Performance | Reduction in Overall Energy Consumption | 0/1/2 | Environmental Training and Education | 0/1 | |

| Reduction in Wastewater Discharge | 0/1/2 | Environmental Public Welfare Activities | 0/1 | ||

| Reduction in Air Emissions | 0/1/2 | ||||

| Reduction in Dust and Particulate Emissions | 0/1/2 | ||||

| Utilization Rate of Industrial Solid Waste | 0/2 | ||||

| Total Score for “Hard Disclosure” | 32 | Total Score for Disclosure | 45 |

| Variable Type | Variable | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | CERD | Score of environmental responsibility disclosure of listed companies |

| CERHD | Score of environmental responsibility hard disclosure of listed companies | |

| Independent Variable | Common Institutional Ownership (CIO) | The number of common institutional investors for a firm in the current year is calculated as the annual average of the quarterly figures, then log-transformed by adding 1. |

| Mechanism Test Variable | Exit Threat (NET) | The product of the competition level among common institutional investors and stock liquidity |

| The Market Power of Common Institutional Investors (numcon) | The number of same-industry firms connected by a company through all its common institutional investors | |

| The Market Power of Common Institutional Investors (avecon) | The average number of same-industry firms connected by a company through a single common institutional investor | |

| Grouping Variable | Positive Performance Expectation Gap | Dgap > 0 |

| Negative Performance Expectation Gap | Dgap < 0 | |

| Control Variable | Age | Years since the first IPO of the listed company |

| Size | Ln (Total assets) | |

| Growth | The growth rate of enterprise operating income | |

| Cashflow | The ratio of cash and cash equivalents to total assets at the beginning of the year | |

| Lev | The ratio of total liabilities to total assets | |

| ATO | The ratio of operating income to total assets | |

| First | The proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder | |

| Balance | The ratio of the proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder to the proportion of shares held by the second largest shareholder | |

| Board | Ln (the number of board members) | |

| Dual | Dummy variable that takes the value of “1” if the manager concurrently serves as chairman of the board, and “0” otherwise. | |

| Indep | The ratio of independent directors to the total number of board members |

| VarName | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max | Correlation Coefficient (CERD) | Correlation Coefficient (CERHD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CERD | 18,399 | 8.8579 | 6.008 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 28.00 | ||

| CERHD | 18,399 | 4.5762 | 4.284 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 18.00 | ||

| CIO | 18,399 | 0.0579 | 0.184 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.180 *** | 0.163 *** |

| NET | 18,399 | 0.0375 | 0.199 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.41 | 0.043 *** | 0.035 *** |

| numcon | 18,399 | 0.2995 | 1.511 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 22.50 | 0.124 *** | 0.110 *** |

| avecon | 18,399 | 0.2857 | 1.461 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 22.50 | 0.114 *** | 0.101 *** |

| Age | 18,399 | 1.9807 | 0.905 | 0.00 | 2.08 | 3.30 | 0.133 *** | 0.120 *** |

| Size | 18,399 | 22.0101 | 1.161 | 19.92 | 21.86 | 25.52 | 0.120 *** | 0.108 *** |

| Growth | 17,318 | 0.1676 | 0.353 | −0.47 | 0.11 | 2.11 | −0.020 *** | −0.018 ** |

| Cashflow | 18,399 | 0.0487 | 0.065 | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.020 *** | 0.018 ** |

| Lev | 18,399 | 0.3920 | 0.195 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.89 | 0.064 *** | 0.059 *** |

| ATO | 17,319 | 0.6687 | 0.380 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 2.34 | 0.065 *** | 0.066 *** |

| First | 18,399 | 33.5148 | 13.992 | 8.98 | 31.40 | 71.24 | 0.055 *** | 0.050 *** |

| Balance | 18,398 | 0.3740 | 0.285 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 1.00 | −0.053 *** | −0.044 *** |

| Board | 18,399 | 2.1140 | 0.187 | 1.61 | 2.20 | 2.56 | 0.076 *** | 0.065 *** |

| Dual | 18,399 | 0.3170 | 0.465 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.071 *** | −0.066 *** |

| Indep | 18,399 | 37.5631 | 5.335 | 33.33 | 33.33 | 57.14 | −0.046 *** | −0.042 *** |

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | m5 | m6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERD | CERD (Standardized Coefficients) | CERHD | CERHD | CERHD (Standardized Coefficients) |

| CIO | 1.258 *** | 1.363 *** | 0.042 ** | 0.669 ** | 0.729 ** | 0.031 ** |

| (2.95) | (3.13) | (3.13) | (2.07) | (2.21) | (2.21) | |

| Age | 0.052 | 0,08 | 0.074 | 0.016 | ||

| (0.50) | (0.50) | (0.91) | (0.91) | |||

| Size | −0.057 | −0.011 | −0.054 | −0.015 | ||

| (−0.79) | (−0.79) | (−0.91) | (−0.91) | |||

| Growth | 0.043 | 0.003 | 0.031 | 0.003 | ||

| (0.47) | (0.47) | (0.44) | (0.44) | |||

| Cashflow | 0.757 | 0.008 | 0.454 | 0.007 | ||

| (1.35) | (1.35) | (1.03) | (1.03) | |||

| Lev | −0.198 | −0.006 | −0.044 | −0.002 | ||

| (−0.61) | (−0.61) | (−0.17) | (−0.17) | |||

| ATO | −0.181 | −0.011 | −0.139 | −0.012 | ||

| (−1.00) | (−1.00) | (−0.97) | (−0.97) | |||

| First | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.020 | ||

| (0.88) | (0.88) | (1.28) | (1.28) | |||

| Balance | −0.268 | −0.013 | −0.111 | −0.007 | ||

| (−1.09) | (−1.09) | (−0.57) | (−0.57) | |||

| Board | −0.136 | −0.004 | −0.343 | −0.015 | ||

| (−0.41) | (−0.41) | (−1.28) | (−1.28) | |||

| Dual | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.003 | ||

| (0.16) | (0.16) | (0.31) | (0.31) | |||

| Indep | −0.018 | −0.016 | −0.015 * | −0.019 * | ||

| (−1.58) | (−1.58) | (−1.74) | (−1.74) | |||

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1079.549 *** | −1079.775 *** | −793.755 *** | −794.420 *** | ||

| (−32.56) | (−32.37) | (−30.85) | (−30.65) | |||

| R-squared | 0.200 | 0.205 | 0.205 | 0.180 | 0.184 | 0.184 |

| n | 18,399 | 17,317 | 17,317 | 18,399 | 17,317 | 17,317 |

| Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | Dgap < 0 | Dgap < 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | 1.531 *** | 0.852 * | 0.964 | 0.439 |

| (2.66) | (1.91) | (1.57) | (0.96) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1169.346 *** | −852.745 *** | −985.596 *** | −724.106 *** |

| (−27.06) | (−25.37) | (−21.74) | (−20.83) | |

| R-squared | 0.229 | 0.207 | 0.181 | 0.162 |

| n | 8453 | 8453 | 8864 | 8864 |

| Variable | Unmatched | Mean | %Bias | %Reduct |Bias| | t-Test | V (T)/ V (C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched | Treated | Control | t | p > |t| | ||||

| Age | U | 2.394 | 2.072 | 42.0 | 98.3 | 16.31 | 0.000 | 0.94 |

| M | 2.394 | 2.389 | 0.7 | 0.22 | 0.829 | 1.11 * | ||

| Size | U | 22.337 | 22.036 | 24.4 | 97.1 | 10.05 | 0.000 | 1.24 * |

| M | 22.337 | 22.416 | −0.7 | −0.20 | 0.844 | 1.03 | ||

| Growth | U | 0.200 | 0.363 | −2.5 | 71.1 | −0.73 | 0.465 | 0.01 * |

| M | 0.200 | 0.153 | 0.7 | 2.16 | 0.031 | 1.91 * | ||

| Cashflow | U | 0.048 | 0.049 | −1.0 | 6.2 | −0.39 | 0.698 | 1.01 |

| M | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.9 | 0.26 | 0.793 | 0.90 * | ||

| Lev | U | 0.427 | 0.399 | 13.9 | 87.2 | 5.56 | 0.000 | 1.06 |

| M | 0.427 | 0.431 | −1.8 | −0.52 | 0.603 | 1.02 | ||

| ATO | U | 0.698 | 0.674 | 4.9 | 89.5 | 2.17 | 0.030 | 1.68 * |

| M | 0.698 | 0.701 | −0.5 | −0.15 | 0.884 | 1.41 * | ||

| First | U | 33.776 | 33.251 | 3.7 | 96.8 | 1.46 | 0.144 | 1.02 |

| M | 33.776 | 34.793 | −0.1 | −0.03 | 0.973 | 0.99 | ||

| Balance | U | 0.342 | 0.374 | −10.9 | 93.1 | −4.36 | 0.000 | 1.07 |

| M | 0.342 | 0.344 | −0.8 | −0.22 | 0.825 | 1.07 | ||

| Board | U | 2.144 | 2.114 | 15.5 | 85.9 | 6.24 | 0.000 | 1.13 * |

| M | 2.144 | 2.140 | 2.2 | 0.63 | 0.526 | 1.11 * | ||

| Dual | U | 0.232 | 0.313 | −18.0 | 90.5 | −6.84 | 0.000 | . |

| M | 0.232 | 0.225 | 1.7 | 0.53 | 0.598 | . | ||

| Indep | U | 37.476 | 37.573 | −1.7 | −18.3 | −0.69 | 0.493 | 1.06 |

| M | 37.476 | 37.555 | 1.4 | −0.40 | 0.688 | 0.95 | ||

| m1 | m2 | m1 | m2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | 4.5544 *** | 2.8781 *** | Balance | 0.7060 | 0.7068 * |

| (12.9920) | (11.5230) | (1.3953) | (1.9607) | ||

| Age | 1.1583*** | 0.7430 *** | Board | 0.3333 | 0.0568 |

| (6.1037) | (5.4955) | (0.4487) | (0.1073) | ||

| Size | 0.4146 *** | 0.2707 *** | Dual1 | −0.2179 | −0.1497 |

| (3.6042) | (3.3025) | (−0.7913) | (−0.7629) | ||

| Growth | −0.3410 | −0.1897 | Indep | −0.0642 *** | −0.0463 *** |

| (−1.0795) | (−0.8428) | (−2.6571) | (−2.6915) | ||

| Cashflow | −3.2378 * | −1.7858 | Industry | Control | Control |

| (−1.7162) | (−1.3285) | Year | Control | Control | |

| Lev | −0.1244 | 0.2382 | Firm | Control | Control |

| (−0.1773) | (0.4766) | Constant | −5.3399 * | −3.9478 * | |

| ATO | 0.5453 | 0.3032 | (−1.8106) | (−1.8787) | |

| (1.6434) | (1.2825) | n | 3147 | 3147 | |

| First | 0.0455 *** | 0.0298 *** | adj. R2 | 0.155 | 0.146 |

| (4.2050) | (3.8708) |

| Gamma | sig+ | sig− | t-hat+ | t-hat− | CI+ | CI− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2 | 2 |

| 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 1.2 | <0.0001 | 0 | 2 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 1.5 |

| 1.3 | <0.0001 | 0 | 1.5 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 1.4 | <0.0001 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.9999 |

| 1.5 | <0.0001 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 0.5 |

| 1.6 | 0.0017 | 0 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 0 |

| 1.7 | 0.0292 | 0 | 0.5 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| 1.8 | 0.1786 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | −0.5 |

| 1.9 | 0.4992 | 0 | 0 | 5.5 | 5.5 | −0.5 |

| 2 | 0.8077 | 0 | 0 | 5.5 | 5.5 | −0.5 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD |

| After × Treat | 0.7459 * | 0.2946 |

| (1.7622) | (0.8956) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control |

| Constant | 16.8665 *** | 10.7495 *** |

| (3.8737) | (3.1741) | |

| n | 3147 | 3147 |

| adj. R2 | 0.260 | 0.235 |

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Two | First | Two | |

| VARIABLES | CIO | CERD | CIO | CERHD |

| IV | 0.093 *** | 0.093 *** | ||

| (28.22) | (28.22) | |||

| CIO | 38.893 *** | 23.627 *** | ||

| (23.25) | (21.53) | |||

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −13.328 *** | −615.262 *** | −13.328 *** | −508.111 *** |

| (−14.55) | (−13.05) | (−14.55) | (−16.43) | |

| F | 33.62 | 33.62 | ||

| n | 17,317 | 17,317 | 17,317 | 17,317 |

| m1 | m2 | |

|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | 0.871 ** | 0.490 * |

| (2.21) | (1.65) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1252.410 *** | −965.354 *** |

| (−11.56) | (−11.34) | |

| R-squared | 0.206 | 0.186 |

| n | 18,230 | 18,230 |

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | m5 | m6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | All | Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | Dgap < 0 | Dgap < 0 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO1 | 0.638 *** | 0.320 * | 0.743 ** | 0.419 * | 0.289 | 0.030 |

| (2.66) | (1.76) | (2.45) | (1.81) | (0.78) | (0.11) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| year | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1084.472 *** | −797.344 *** | −1174.986 *** | −855.703 *** | −990.029 *** | −727.133 *** |

| (−32.43) | (−30.70) | (−27.17) | (−25.40) | (−21.81) | (−20.92) | |

| R-squared | 0.204 | 0.184 | 0.229 | 0.207 | 0.180 | 0.162 |

| n | 17,317 | 17,317 | 8453 | 8453 | 8864 | 8864 |

| m1 | m2 | m1 | m2 | m1 | m2 | m1 | m2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dgap1 > 0 | Dgap1 > 0 | Dgap1 < 0 | Dgap1 < 0 | Dgap2 > 0 | Dgap2 > 0 | Dgap2 < 0 | Dgap2 < 0 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | 2.013 *** | 1.133 ** | 0.644 | 0.275 | 1.437 ** | 0.818 * | 1.198 | 0.530 |

| (3.30) | (2.40) | (1.06) | (0.61) | (2.56) | (1.87) | (1.97) | (1.16) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| IND | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| year | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1160.802 *** | −851.605 *** | −990.409 *** | −726.232 *** | −1148.424 *** | −841.911 *** | −1015.222 *** | −740.752 *** |

| (−26.03) | (−24.86) | (−21.50) | (−20.52) | (−26.68) | (−25.01) | (−23.54) | (−22.37) | |

| R-squared | 0.222 | 0.203 | 0.180 | 0.160 | 0.226 | 0.204 | 0.191 | 0.171 |

| n | 8535 | 8535 | 8782 | 8782 | 8196 | 8196 | 9121 | 9121 |

| Dgap3 > 0 | Dgap3 > 0 | Dgap3 < 0 | Dgap3 < 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | 1.996 *** | 1.018 ** | 0.837 | 0.416 |

| (3.14) | (2.05) | (1.42) | (0.94) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1052.275 *** | −767.861 *** | −1057.289 *** | −773.663 *** |

| (−21.98) | (−20.66) | (−23.28) | (−21.95) | |

| R-squared | 0.197 | 0.174 | 0.180 | 0.159 |

| n | 7654 | 7654 | 9663 | 9663 |

| m1 | m2 | m1 | m2 | m1 | m2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | All | Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | Dgap < 0 | Dgap < 0 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| NET | −0.243 | −0.236 | 0.003 | −0.085 | −0.423 * | −0.368 * |

| (−1.35) | (−1.65) | (0.01) | (−0.38) | (−1.79) | (−1.83) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1098.338 *** | −804.866 *** | −1199.266 *** | −869.957 *** | −994.375 *** | −728.719 *** |

| (−32.57) | (−30.82) | (−27.16) | (−25.32) | (−21.91) | (−20.98) | |

| R-squared | 0.203 | 0.184 | 0.227 | 0.206 | 0.181 | 0.162 |

| n | 17,317 | 17,317 | 8453 | 8453 | 8864 | 8864 |

| PanelA all | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| numcon | 0.127 *** | 0.075 *** | ||

| (3.63) | (2.90) | |||

| avecon | 0.125 *** | 0.073 *** | ||

| (3.44) | (2.71) | |||

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1075.773 *** | −791.080 *** | −1077.529 *** | −792.288 *** |

| (−31.72) | (−29.99) | (−31.78) | (−30.06) | |

| R-squared | 0.205 | 0.184 | 0.205 | 0.184 |

| n | 17,317 | 17,317 | 17,317 | 17,317 |

| PanelB Dgap > 0 | ||||

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| numcon | 0.096 ** | 0.054 * | ||

| (2.46) | (1.89) | |||

| avecon | 0.089 ** | 0.048 * | ||

| (2.22) | (1.65) | |||

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1173.143 *** | −854.632 *** | −1176.662 *** | −857.134 *** |

| (−26.43) | (−24.73) | (−26.51) | (−24.79) | |

| R-squared | 0.228 | 0.207 | 0.228 | 0.207 |

| n | 8453 | 8453 | 8453 | 8453 |

| PanelC Dgap < 0 | ||||

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| numcon | 0.207 *** | 0.130 ** | ||

| (2.78) | (2.37) | |||

| avecon | 0.211 *** | 0.134 ** | ||

| (2.84) | (2.37) | |||

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −976.193 *** | −716.959 *** | −976.717 *** | −717.140 *** |

| (−21.49) | (−20.52) | (−21.50) | (−20.53) | |

| R-squared | 0.182 | 0.163 | 0.182 | 0.163 |

| n | 8864 | 8864 | 8864 | 8864 |

| All | All | All | Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m4 | m5 | m6 | |

| VARIABLES | Exc_Mon | CERD | CERHD | Exc_Mon | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | −0.011 *** | −0.014 *** | ||||

| (−4.82) | (−4.68) | |||||

| Exc_Mon | −9.716 *** | −5.473 *** | −8.100 *** | −4.399 ** | ||

| (−4.95) | (−3.65) | (−2.98) | (−2.10) | |||

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | 6.177 *** | −1041.274 *** | −772.194 *** | 7.099 *** | −1147.234 *** | −840.844 *** |

| (35.60) | (−29.59) | (−28.17) | (28.60) | (−24.66) | (−23.16) | |

| R-squared | 0.205 | 0.207 | 0.185 | 0.242 | 0.230 | 0.208 |

| n | 17,111 | 17,111 | 17,111 | 8359 | 8359 | 8359 |

| All | All | All | Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1 | m2 | m3 | m1 | m2 | m3 | |

| VARIABLES | Exc_NonMon | CERD | CERHD | Exc_NonMon | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | −0.009 *** | −0.012 *** | ||||

| (−4.48) | (−4.78) | |||||

| Exc_NonMon | −8.940 *** | −4.601 ** | −10.301 ** | −6.012 * | ||

| (−3.24) | (−2.18) | (−2.54) | (−1.90) | |||

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −0.201 | −1103.414 *** | −807.162 *** | 0.090 | −1203.629 *** | −871.333 *** |

| (−1.34) | (−32.45) | (−30.59) | (0.42) | (−27.15) | (−25.23) | |

| R-squared | 0.012 | 0.205 | 0.184 | 0.023 | 0.230 | 0.208 |

| n | 17,111 | 17,111 | 17,111 | 8359 | 8359 | 8359 |

| All | All | Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1 | m2 | m1 | m2 | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | 1.450 ** | 0.908 * | 1.373 | 0.816 |

| (2.20) | (1.82) | (1.60) | (1.29) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1080.251 *** | −777.512 *** | −1196.776 *** | −897.424 *** |

| (−14.50) | (−13.49) | (−10.68) | (−10.29) | |

| R-squared | 0.183 | 0.161 | 0.223 | 0.209 |

| n | 5021 | 5021 | 2318 | 2318 |

| All | All | Dgap > 0 | Dgap > 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | |

| VARIABLES | CERD | CERHD | CERD | CERHD |

| CIO | 1.244 ** | 0.556 | 1.738 ** | 0.896 |

| (2.27) | (1.33) | (2.25) | (1.47) | |

| Control variable | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Industry | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Year | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Firm | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Constant | −1081.937 *** | −795.523 *** | −1142.771 *** | −819.293 *** |

| (−27.22) | (−25.71) | (−22.10) | (−20.57) | |

| R-squared | 0.206 | 0.187 | 0.223 | 0.209 |

| n | 12,296 | 12,296 | 6135 | 6135 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X. Research on the Effect of Common Institutional Ownership on Corporate Environmental Responsibility Disclosure: A Performance Feedback Perspective. Systems 2025, 13, 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100868

Zeng Y, Wang Z, Zhao X, Zhang X. Research on the Effect of Common Institutional Ownership on Corporate Environmental Responsibility Disclosure: A Performance Feedback Perspective. Systems. 2025; 13(10):868. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100868

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Yanqi, Zongjun Wang, Xinxin Zhao, and Xian Zhang. 2025. "Research on the Effect of Common Institutional Ownership on Corporate Environmental Responsibility Disclosure: A Performance Feedback Perspective" Systems 13, no. 10: 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100868

APA StyleZeng, Y., Wang, Z., Zhao, X., & Zhang, X. (2025). Research on the Effect of Common Institutional Ownership on Corporate Environmental Responsibility Disclosure: A Performance Feedback Perspective. Systems, 13(10), 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100868