Abstract

Water is the source of life and also the lifeline of cities. The reconstruction of secondary water supply systems is a key component of urban renewal reforms, and the collaborative governance of such projects has become a focal topic through academic research. In this article, we try to discover the path to successful “bottom-up” collaborative water governance with Collins’s theory of interaction ritual chains (IRC) through a case study of a secondary water supply reconstruction program in J Estate, Jinshan District, Shanghai. The case study involved a total of 104 households, and we employed convenience sampling for all households through door-to-door inquiries, which included semi-structured interviews and non-participant observations. A total of 15 households participated in our interview. This study demonstrates that repeated social interactive rituals, such as bodily co-presence, rhythmic synchronization, and shared signs, can stimulate the accumulation of residents’ emotional energy, which becomes the initial power to promote community water governance and, in return, becomes the driving force for sustained collective action and mutual trust. Drawing on Collins’s theory of IRC, this article fills a gap by explaining the symbolic mechanism driven by emotions and personal relationships that macro-level governance ignores. We also demonstrate the spillover effects of such social rituals and propose policy recommendations that governments should apply, using these rituals to mobilize and consolidate residents’ emotions to create a virtuous circle of collaborative governance.

1. Introduction

Public affairs related to natural resources are thought to be important for the majority of the population, but they are taken care of by the minority; however, this is changing due to the treatment of public goods. The bottom-up policy and decision-making processes established by citizens and actors from the private and non-profit sectors is gradually replacing traditional top-down governance [1,2], bridging the gaps between the fields of local service delivery [3], natural hazard management [2], medical insurance [4], climate change governance [5], and the establishment of urban community gardens [6]. Among all the public issues, water management and governance are of great importance for maintaining citizens’ basic life needs and health, and they are currently experiencing a transition [7]. More and more citizens and communities participate in the process of water management and governance, whether invited by governments or organized by themselves from the bottom up [7,8].

Traditionally, the control and maintenance of natural resources have been given to centralized government institutions [9], forming the top-down mode of governance. However, this centralized and uniform governance has engendered a multitude of issues, such as water availability and safety problems [10,11], which fail to meet the needs of local residents and thereby make the safeguarding of their subsistence and living security infeasible. This drives local residents to participate in the daily management of natural resources, playing the role of extensions of the state’s sensing capacity and filling the vacancy that local government and technologies may not account for [12]. This is also the case for water governance. The present water crisis has become a threat to everyone’s life, demanding urgent modes of action to cause a change in consciousness [13]. Thus, for now, cooperation is the frontier of participatory water governance [14].

1.1. Relationship Between Top-Down and Bottom-Up Governance

From the perspective of formal concepts, services provided by the government or governmental agencies are typically characterized by centralized planning and implementation and are categorized as top-down. In contrast, services offered by non-governmental organizations, community organizations, or other small-scale providers are distinguished by a higher degree of decentralization in both planning and execution and are classified as bottom-up [15]. The existing research has discussed the subtle relationship between top-down and bottom-up water resource governance. Environmental governance, including water issues, is not a one-time outcome; it is prolonged and dynamic. It has generally been predominantly driven by top-down policies, with performance appraisal [16] as the simplest and quickest response to these policies [17]. However, due to governance difficulties, such as disproportionate effects [18], being too prescriptive and fragmented [19], a lack of regard for indigenous knowledge, and failing to reflect the values of the community [17], there is a need to shift from a power-oriented approach to a rights-oriented one that listens to the needs of residents and responds to their demands for “people-oriented” development [16]. Top-down governance may have a misunderstanding that the public is poorly organized and has limited knowledge during the decision-making process [20], but it is a proven fact that bottom-up approaches can work as a remedy to environmental governance problems when there are poorly aligned social institutions and fragmented ecosystems [21]. Social norms, customs, traditions, beliefs, and any other forms of local knowledge are used to guide “bottom-up” approaches [22] as a cost-effective way to meet local social and environmental needs [23,24]. However, more scholars hold the same opinion that institutional hybridization, i.e., the mixing of both community and government water governance, is better from a development planning and policy perspective. In order to enhance the adaptive capacity of social–ecological systems to global changes, it is essential to build around multi-level, integrative, and participatory institutional arrangements [25]. The key aspects of this are both the active role of local government, which provides robust policy and regulatory and financial support while simultaneously strengthening the technical capacity of community water management committees and their partners to ensure water is managed inclusively and sustainably for all [26], and new collaborative networks among stakeholders that initiate unprecedented dialogue among numerous local entities, which has significant potential for mutual learning and fosters a strong sense of ownership and engagement [27]. In addition, Hassenforder et al. [28] point out that the middle ground of the two management modes may differ from one place to another and that this is mainly determined by the stakeholders who orchestrate the process, the vertical scalar extension achieved by the process, and the nature of existing cross-level interactions and communications.

1.2. Participatory Water Governance

Recent research on participatory water governance has focused on its components, establishment process, and advantages compared to traditional central governance. Participatory water governance appears to solve the lacking of synergy between public institutions [29], inefficiency and inequality of the single way of managing limited resources and their long-term sustainability [30], and the strained social and power relations between residents and local institutions [29] due to traditional top-down water governance. Participatory water governance is more effective, strong, and resilient [31] than the traditional governance mode of technocratic hierarchies, as it listens to the voices of the community [32]. The effect of the participatory process is not directly evident in final decisions; rather, it is evident through more complex and nuanced multiplication routes that amplify the impacts on decisions throughout the overall polycentric governance system [33]. Islam et al. [34] found that when the government delegates its power to various water users (farmers, fishermen, women, etc.), water allocation is not only better aligned, but it also strengthens collective action, capacity building, and sustainable development. This type of governance, which is culturally rooted in practices, can better resolve water problems, enhance the water supply management system [35], and improve community health [36,37,38]. The main characteristic of participatory water governance is that it involves a wide range of stakeholders, who can help to lead effective water governance [39]. Although water governance stakeholders often have different values and opinions about water resources and understandings of particular problems, they can still relate to each other through the proper design of participatory processes [40,41]. Stakeholder analysis is a crucial tool for successful collaborative governance in water-related governance as it can identify, categorize, and prioritize key stakeholders to tailor engagement strategies and streamline participation [42]. However, He et al. [43] recommended recognizing the differential power and interests of different actors to ensure that outcomes are not skewed in favor of particular interests. Certainly, participatory governance has encountered difficulties in its implementation. The lack of social trust, elite capture of participatory processes, imbalance of and heterogeneity in power at the micro-level [44,45], lack of inclusive participation in decision-making, and shared accountability [46] are the main challenges that participatory governance faces to reach success [47]. To develop participatory governance, scholars suggest expanding legal power, strengthening the cooperation between academic and knowledge-based individuals and enterprises, improving the stance of the private sector, and encouraging supervision of NGOs at the state and local levels [48]. Thus, it is essential for policymakers to proactively draw on existing evidence and experience to learn how to enable the public to participate meaningfully in planning and decision-making [49], which includes the scarcity of water availability, the capacity to build broad governance, integrating marginalized rural communities, and fostering innovative grassroots leadership [50,51].

In general, scholars state that “top-down hierarchical models” should be replaced with models that are more transparent and holistic, involving more stakeholders, including the public and non-state actors, and more practical experiences within policy dialogues at different territorial levels [1]. In other words, government-led administration and community-led administration are complementary [52], and they can only succeed when effective co-creation exists to create public value [7]. Table 1 presents the main differences, advantages, and disadvantages of top-down, bottom-up, and participatory co-governance in water issues. Participation can best serve to bolster both resource sustainability and the resilience of cities as coupled social–ecological systems [30]. In addition, community participation can not only help solve fundamental survival problems, but it can also help the community engage with formal state organizations and offer it access to legal assistance, especially for the poor [11]. Interestingly, the urban poor succeeded in obtaining resources by appropriating the very stages, such as public squares, press events, and pilot projects, that elites and the government designed for self-promotion, thus attracting essential external resources by leveraging them [10].

Table 1.

Comparing top-down, bottom-up, and participatory co-governance water governance.

1.3. Informal Institutions (Rituals) in Public Goods Governance

Beyond formal institutions, policies, and governance processes, informal mechanisms also exert a profound influence on the governance of public goods and issues. The lack of legal enforceability can cause a limited supply of the provision of public goods due to a collective action problem [56]. In this case, rituals and social norms, which we can more broadly define as informal institutions, can be a complementary method when there are weak or no formal rules [57,58]. Anthropologists have always been interested in collective rituals; previous studies have found that social rituals involving synchronous movement improve prosocial attitudes, thus increasing cooperative behavior [59]. For example, Xu and Yao [60] found that clans and big families connected by kinship can encourage an increase in local public investment considerably in China. Similar results were found in the field of cleaner production and environmental governance, where informal institutions related to cultures, such as Confucian virtues, restrain one’s behavior and provide guidelines and motivations for developing better ethical actions [61]. Norm-based, non-regulatory interventions achieve significant, nation-wide green innovation at the plant level [62]. Additionally, communities with dense informal institutions tend to have higher collective action capacity to organize their citizens [63]. This demonstrates that informal institutions and social rituals exert a subtle and profound influence on public affairs governance by shaping shared values and behavioral norms. This influence operates not through short-term performance or efficiency logic, but by fostering long-term collective coordination via cultural identity and social trust.

Although the existing research has extensively explored the interactions between top-down and bottom-up water governance models, acknowledged the role of participatory co-governance as a balancing mechanism, and recognized the influence of rituals as informal institutions and social norms in public governance, there is still a lack of in-depth understanding of how social rituals concretely drive the entire process of successful public goods provision. The current literature has yet to adequately trace the micro-dynamics through which social rituals operate from initiation to institutionalization and, ultimately, to tangible outcomes. There are several critical questions that remain unresolved: How do rituals serve as preconditions for building collective identity and trust? Under what conditions do these informal practices evolve into more structured forms of participatory co-governance, even solidifying into formal institutions? How can rituals facilitate sustained stakeholder participation during intermediate stages to overcome cooperation dilemmas? Can rituals ultimately interact with formal and state-related governance structures to achieve tangible communal goals? Few studies have examined this continuous course or provided a process-oriented analysis that captures how ritualistic practices are embedded in and reshape the dynamics of participatory co-governance.

Our research, therefore, uses a typical participatory secondary water supply governance case study in Jinshan District, Shanghai, China, to fill the gap and reveal the mechanism from a microscopic perspective. In this article, we perform a micro-sociological check that draws on the theory of IRC to illuminate how social interactions through rituals generate emotional energy, solidify group solidarity, and reconfigure institutional arrangements in real-world water governance contexts in China. Simultaneously, we also provide a narrative framework grounded in the Chinese context to IRC theory, which expands its explanatory scope and potential for application. This article is structured as follows. The Section 2 reviews some basic ideas of the interaction ritual chain theory, such as its symbols, mechanisms, and restructuring, as well as its broad applicability within and outside the context of Chinese culture and social experience. Here, we build a theoretical Interaction Ritual Chain Process Model (IRCPM) to guide our case study. In Section 3, we describe the framework and methods used to analyze the case study. The case study is then described in detail by a timeline and history of the secondary water supply systems in Shanghai, the reconstruction of the whole supply system, and the supervision system, which consists of members and officials from both governmental offices and the community. Conclusions and discussions are provided in the final section to interpret the case study based on the ideas from IRC theory, revealing the integration process of individuals into the governance and management of community issues. We also suggest government actions to activate participatory governance and achieve co-governance.

2. Theoretical Framework

In this article, we introduce Collins’s theory of interaction ritual chains to build the theoretical framework and to analyze our case study. In contrast to macro-level theories, such as Polycentric Theory, which emphasizes multiple centers of decision-making, none of which has ultimate right to make all collective decisions [64], and meso-level theories, such as Collaborative Governance Theory [65], which outlines the institutional stages of decision-making [40], Collins’s IRC theory offers a complementary micro-sociological lens. On the other hand, micro-level theories, such as Common-Pool Resource Theory [66], which raised the possibility of self-organization to deal with the “tragedy of the commons”, and the assumed condition that everyone is capable of making rational and sensible decisions, over-rely on the rational choice model and neglect social embeddedness [67]. IRC thus compensates for this gap and better matches the realistic model. It tackles the questions of why people are genuinely willing to cooperate and how exactly a sense of identity and motivation behind the rules emerges. Thus, IRC theory reveals the underlying interactional and emotional mechanisms by which shared rituals generate the very emotional energy and solidarity that constitute “social capital” and fuel successful collaborative processes. It provides the foundational motivation and emotion that drive the more formal framework of social cohesion and governance.

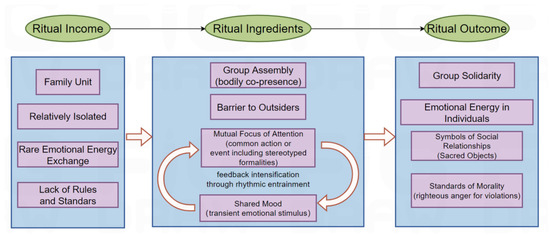

The interaction ritual chain theory, as proposed by [68], offers an account of how face-to-face encounters generate emotional energy and solidarity and uncovers the micro-mechanisms that sustain social cohesion. Departing from traditional explanations, Collins contends that interaction rituals extend beyond sacred rites or formal ceremonies to be a pervasive feature of everyday life. Family gatherings [69], casual meals with friends, meetings, and even exchanges on social media can all generate interaction rituals, which give rise to strengthened bonds and connections. The key function of IRC theory is its capacity to create and sustain emotional energy. It is not only a simple affective reaction, but a durable emotional state acquired through social engagement, which could help bolster self-efficacy, stimulate agency, and deepen social bonds. That is to say, a person’s emotional consequences from successful or unsuccessful interaction rituals are what the theory is interested in [70]. Collins [68] emphasized that social encounters are not merely conduits for information or resources; they are circuits of emotional energy. Through participating in ritual interactions, individuals can amplify their personal stock of emotional energy. Within a group, the energy can be recycled and intensified, which helps to foster a sense of belonging and mutual identification. This efficiently facilitates more vigorous involvement across diverse spheres of social activity [71], which forms participatory governance. Liao et al. [72] also indicated that the sequential ordering of task-oriented and socio-emotional moves extracts the core of conversational rituals, generates emergent solidarity, and yields the intended interpersonal influence. The four initiating conditions, namely, the capacity to assemble, common linguistic and behavioral norms, and a shared focus of attention, support the basis of the interaction ritual chain; they can be considered a boundary to outsiders and allow for the establishment of a social group [73]. Table 2 illustrates the working mechanism of IRC. Veeck et al. [74] illustrated that, besides bonding, bridging, and the generation of wellbeing [75], blocking and breaching are the two other outcomes that everyday rituals may lead to, which can reinforce prejudices, distrust, and isolation between groups and produce or reproduce inequality. In addition, researchers have found that the level of emotional energy is also related to gender, with men having a lower level than women [76].

Table 2.

The theoretical framework of interaction ritual chains (IRCs): conditions, process, and outcomes.

The generation of “emotional energy” through collective rituals is the core of IRC theory, which illustrates the foundation of the process mechanism. Within their original cultural–religious context, rituals serve to create a new social space for indigenous peoples, such as those in Rio Branco, Brazilian Amazon. In this space, activities ranging from ayahuasca ceremonies to political meetings enable the demonstration of symbolic social capital, which breaks social barriers and fosters greater inclusion [77]. A regular religious service with higher frequency but less emotion, such as an observant Jewish service, can allow individuals to socially identify as members of a particular social category. At the same time, rituals with low frequency but higher emotion produce identity fusion, such as that among Navy Seals, which is a powerful unifying force of the self with the group [78] (Rossano, 2020). Rituals are also widely used in modern societies, such as schools in West Virginia, which regularly hold ritualized school–community meetings including songs, speeches, readings, and other activities to build social capital, resulting in a rise in student attendance and library funds [78]. Thus, different forms of religious, social, or political identification come from various types of group rituals [79].

The interaction ritual chain is a natural window to observe and reveal the formation of social identity, trust, and emotional energy from a micro-level angle. In addition to this, the IRC theory has its own particularity and explanation in China. What we want to emphasize in this article is the different political background in China, but the similar core and explanation of “rituals”, compared to Western countries. Conceptually, the unique value of Collins’s theory in the Chinese context lies in its ability to translate the Western concept of “institutions”, “norms”, or “values” into “rituals” in Chinese. Inversely, China-based empirical cases help to remedy the Western bias inherent in mainstream social theory [80]. Rituals can be translated into kinship relations, community and neighborly relations, clans, and big families [60], or “guanxi”, which means “relationship” [81], under the cultural circumstances of China. China’s relationship network can essentially be regarded as a form of a generalized interaction ritual. According to Collins’s theory of IRC, the establishment and maintenance of relationships through activities such as dining together, gift-giving, visits, or collaborative problem-solving can fully align with the core elements of rituals. These activities require physical or virtual “co-presence” among participants, create a shared emotional experience around focal points, like reciprocal obligation and “mianzi” (which means “face”), and establish clear ritual boundaries between “insiders” and “outsiders”. The continual repetition of these interactions reproducibly generates group solidarity, emotional energy (such as trust and a sense of security), relational symbols (such as indebtedness), and a sense of moral obligation. Relationships in the Chinese context and their related social action can be evaluated as a productive ritual process, which also emphasizes the explanatory power of IRC in understanding the micro-level dynamics of Chinese society. Scholars found that national building strategies that depend on state symbols and collective memory may lose efficiency during crises when formalism occurs; however, such Chinese translated rituals can assist in facilitating microsocial interactions, together with governance, and reconstructing relevant meanings [82]. In this article, we try to explain how collective actions are formed to accumulate social capital of emotional energy through informal neighborhood relationships and interactions. In the case study, the “coordination meetings” organized by resident committees and local government authorities function as distinctive micro-political rituals with Chinese characteristics that skillfully blend official discourse with grassroots appeals, incorporating a degree of recognition and trust in the authority of local governance. They reflect a unique mode of interaction in which state and social forces intertwine at a local level.

In this paper, we treat the ritual ingredients forming the base of the IRC theory as the mediated variable to explain the endogenous and exogenous factors that affect the transfer of a scattered ritual income to a united ritual outcome. Figure 1 shows the theoretical model we constructed, which is the Interaction Ritual Chain Process Model (IRCPM). This model starts with the original condition of the ritual subjects as ritual income, whose characteristics include isolation, sealing, and lack of rules and standards. Within a community, each individual, or every household, stands as a solitary island, whose emotions and experiences are unbridged, thus lacking shared rituals and collective memory. Similar to the mediating variable, ritual ingredients comprise a combination of several factors and actions that constitute the process [68]. It contains group assembly, which naturally sets barriers to outsiders who do not live in the community, and a common focus on public events or issues. When two or more people or families have a shared emotional focus, community energies can be catalyzed and accumulated, which drives out the collective effervescence [71]. Through the mediating process, our ritual income variable transformed from an isolated variable, producing group-cohesive, social relationship energy symbolization and moral standard ritual outcomes with shared emotions and memories [68,83]. In this article, we display every step of the whole process and explain how the transformation was facilitated through the ritual ingredients. Our research furnishes Collins’s theory with a fully specified process mechanism, thereby completing its explanatory chain.

Figure 1.

Interaction Ritual Chain Process Model (IRCPM).

3. Research Background

3.1. Research Area

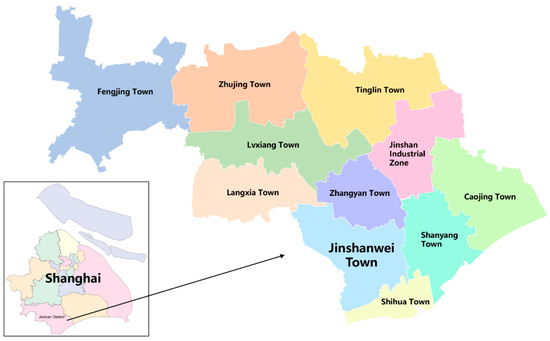

The site of our case study was Jinshan District, which is located in the northwest of Shanghai, with about 822,700 residents. The housing estate where the case study took place is located in the north of Jinshanwei Town in Jinshan District (See Figure 2). We refer to it as J Estate in the remainder of this article. In 2016, the Shanghai government found that an extreme cold snap exposed a weakness in the secondary water supply infrastructure of the old housing estates. Many water meters froze, and pipes burst, which directly influenced residents’ quality of life. Thus, in the same year, Jinshan District followed the unified direction of the Shanghai Water Authority, in line with the city-wide timetable for retrofitting suburban secondary water supply systems. The direction promised that every housing estate built before 2000 would be retrofitted and formally transferred to professional operators of the secondary water supply system. This program was first piloted in 2016, rolled out in 2017, completed in 2018, and fully handed over in 2019. It covered roughly 4.92 million square meters and benefited about 194 housing estates, including 70,000 households and families, with a total investment of approximately CNY 226 million from municipal, district, and town governments. On the other hand, the latest document jointly issued in 2023 by the Shanghai Water Authority, Shanghai Municipal Commission of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, and Shanghai Municipal Housing Administration Bureau requires that water supply enterprises take over all residential areas built after May 1, 2023. Each district is gradually taking over the secondary water supply facilities of newly built residential areas that meet the conditions after assessment. While this policy ensures that all pre-2000 facilities are professionally managed by licensed utilities and has largely prevented water problems in the post-2023 estates in Jinshan District, it has created a dilemma for those built between 2000 and 2023.

Figure 2.

Overview of the study area.

As the municipal guiding policies have not yet been issued, the secondary water supply facilities in the completed residential areas built from 2000 to May 2023 are operated, inspected, maintained, and managed by the property management companies or resident committees to which the communities belong. In J Estate, built in 2005, where our story unfolds, yellow, turbid water frequently flows from taps, seriously disrupting residents’ daily lives. The residents conjectured that it was most likely caused by a section of aging, corroded booster pump piping. Many families had to buy bottled water for daily life, which is costly and inconvenient. Although they submitted complaints to the property management officer, they received excuses without any substantial improvement. The property management office explained that they inspected the whole system. Still, it was both technically challenging and costly to replace the entire booster pump station and the building’s internal pipes. The maintenance funds were insufficient, unless the shortfall could be covered by the residents of the two affected buildings. However, several units were vacant, and there seemed to be no reason to pay for their absence since they did not use water. As a result, the retrofit of the building’s secondary water supply system remained stalled, and both the residents and the property management office were eager to receive guidance and support from higher-level authorities. According to the statistics from the Water Authority of Jinshan District, 239 communities in Jinshan District have not been connected to secondary water supply facilities since 2000. A preliminary assessment shows that nearly half of these communities need to renovate their secondary water supply facilities, such as buried pipes, vertical pipes, and water tanks.

Although there were a lot of difficulties, buildings 20 and 21 of J Estate have successfully solved these problems and renewed their secondary water supply system. Jinshan District was chosen as the case study of our article to analyze the underlying logic of participatory co-governance and the special effect of interactional rituals on both its typical and conducive effects.

We chose the single case study that happened in J Estate not because of its statistical representativeness, but because of its paradigmatic and analytical value in illuminating a widespread governance dilemma and its innovative solution. Its typicality is evident in the following three ways:

- Typicality of governance dilemmas as a prevalent policy blind spot: Built between 2000 and 2023, the housing estate exemplifies a widespread category of neighborhood that is “too new for state-led renewal, but too old to function properly as well”. This policy exclusion created a critical void, forcing residents to confront shared infrastructure decay with no top-down solutions. This case study, therefore, serves as an essential opportunity to examine how collective action emerges precisely in the absence of government impetus, a scenario that countless mid-aged communities face across China.

- Typicality of governance innovation as a prototype for sustainable co-governance: Beyond solving a local issue, the case study exemplifies a broader shift in the governance paradigm from state-dominated delivery to resident-driven coproduction. It demonstrates a model where the government’s role successfully transitioned from a provider to a facilitator and enabler, while empowered residents became the leading actors. This transformation offers a replicable blueprint for achieving community self-governance in policy gaps, making the case analytically generalizable to theories of modern governance. In fact, several adjacent buildings in the same housing estate spontaneously initiated self-governance water pipes reconstruction programs following the success of buildings 20 and 21 in our case study. This spillover effect shows a tendency to spread further, which we will discuss in the subsequent sections of this paper. This phenomenon also serves as strong evidence of the replicability and typicality of the case examined in our article.

- Typicality of the social mobilization challenge as a microcosm of urban demographics: The community’s demographic structure, featuring a core of middle-aged residents alongside elderly occupants and young families, is a classic profile of urbanizing China. This creates a fundamental mobilization dilemma of how to activate a critical mass from a heterogeneous population with divergent interests and capacities. In this case, it reveals the detailed mechanism of interaction rituals, which successfully overcame the universal social barriers, transforming isolated individuals into a solidary collective. It thus provides a transferable model for understanding grassroots mobilization in similarly diverse urban settings.

The reconstruction of secondary water supply systems has become a significant challenge in urban areas in China, even around the world, due to similar difficulties, such as diversified management departments, raising project funds, implementing responsibilities, and coordinating resident conflicts. The housing estates built between 2000 and 2023 in Jinshan District have shown such characteristics, as an aggregation, but they have successfully solved the above problems. In addition, the actions Jinshan District took to gather together almost every household and the related government sectors displayed its wisdom and effort to form a professional management system for not only secondary water supply facilities but also other public affairs. It has provided a comprehensive and multi-departmental governance experience for the renovation and transfer in residential areas across the country.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Our study obtained qualitative data from the residents and families living in J Estate in Jinshan District through fieldwork. The case study involved a total of 104 households, and we employed field-based convenience sampling for all households through door-to-door inquiries, which included semi-structured interviews and non-participant observations. We excluded the residents who were unwilling to participate, residents who had recently moved in and had not been involved in the reconstruction program, and tenants who were not the owners of the house, who seemed to have no voice or position to take part in participatory co-governance. A total of 15 households participated in our interviews, with an average interview length of 5 min. Each interview included three long conversations within 30 min, depending on the residents’ different degrees of involvement in the reconstruction program. Each semi-structured interview consisted of the following parts:

- Pre-reconstruction experience: The residents discussed their problems, difficulties, and frustrations with the old iron water pipes.

- Participation process: The residents discussed how they took part in the program, frequency, and mode of participation in discussions and meetings, interactions with other residents or officials, and the exact motivation of their financial decisions.

- Motivations and barriers: The residents discussed their reasons for participating or not and the difficulties they encountered.

- Sentiments and evaluations: The residents discussed their feelings about the process of co-governance, the degree of satisfaction with the outcome, and changes in their sense of community belonging.

The depth of our questioning was adapted to each resident’s level of involvement in the reconstruction program, with open-ended follow-up questions posed based on issues they raised spontaneously.

Also, we formed two discussion groups with officers from Jinshan Water Authority, Jinshan Housing Authority, the urban construction management committee, water supply companies, and the property management company to obtain complete information on their role in the secondary water supply governance program and how they cooperate and collaborate on the same issue. The time lasted for an average of one hour. We collected data through semi-structured interviews in the discussion group section. Both sets of collected data were in Chinese and translated into English due to the time for analysis. The transcripts were analyzed through intensive thematic analysis without the use of automated coding software. Given the in-depth nature of this study and the manageable sample size, we used a manual approach to allow for a more nuanced and intimate engagement with the textual data. The fieldwork included active examination, photographs, and observation of residents’ daily life, combined with natural conversations with the households and officials, aiming to explore existing situations in the natural setting through primary qualitative research methods. During our fieldwork, the removal of old water pipes was in progress in two buildings adjacent to the main ones we studied. This aided the understanding of local values, participating enthusiasm, and the emotional exchange process.

This study employed the method of triangulation for both the interview and discussion groups of residents and officials to ensure the accuracy, depth, and credibility of the research findings. Triangulation was implemented in the following ways:

- Data Source Triangulation: We collected two types of data. First, in the one-on-one interviews with residents, we gathered their detailed personal opinions, feelings, and experiences regarding the water pipe reconstruction from the perspective of the main initiators. Second, we collected data from a focus group with the officials from the neighborhood committee, the water authority of Jinshan District, and water companies, to understand the collective perspectives of the government side regarding policy implementation, resource coordination, and community management.

- Methodological Triangulation: We combined both the interviews, which provided in-depth personal narratives, and the discussion groups on government actions that stimulated interaction among participants and coordinated work.

- Investigator Triangulation: Data were collected and analyzed by two researchers on our team, ensuring interpretive consistency and reducing individual researcher bias.

Through its triangulation design, our case study was able to first cross-verify reconstruction details to restore the authenticity of the event and enhance the credibility of conclusions. Second, it was able to reveal multiple perspectives about the uncovered actions and potential thoughts of both the residents and the government sides, as well as details on how informal and bottom-up governance linked up with formal institutions, helping to deeply understand the identity positioning for both groups within co-governance and leading to a more comprehensive and three-dimensional understanding of the public policy issue of old community renovation. Through these micro-level data on what the residents and government officials thought and did, we revealed the operation mechanism of interactional rituals and how it can help improve the government’s efficiency.

4. Results

4.1. Sharing Problems as the Beginning: Isolated Ritual Income

Secondary water supplies are closely and highly related to residents’ water safety and quality of life, as they are the closest link to water supply systems. The sharing problem forced a connection between the initially isolated families. Almost all the interviewed families reported the terrible situation of the water supply systems. The water was full of oil stains, red iron rust, corrosion, and dirt. Every morning when they turned on the tap, the residents had to wait a few minutes for the yellowish and turbid water to turn clean. One of our interviewers, who was also one of the leaders of the renovation project, told us the following:

“In contrast to metallic iron, trivalent iron is highly toxic. Water is essential to life. However, when you brush your teeth, heavy metals in the water may be ingested and accumulate in the body, potentially leading to illness. The cost of treating such illnesses can far exceed the investment in ensuring water safety. Those families who have little kids or children have to buy bottled mineral water to keep their growth safe, which is costly and inconvenient. It is abnormal that we, the residents, cannot maintain water safety in our housing estate.”(Interview Code: 20241211211302).

The majority of the families (73.33% of our interviewees) reported having complained to the property management office separately. Of the 11 families, 6 stated they received no efficient response from the resident committee or were dissatisfied with its work. Although 46.67% of the interviewees mentioned they had a water prefilter at home, three of them also complained about the frequent replacement of the filter element every three months, which is expensive and inconvenient. Overall, 27.27% of the interviewees had to buy bottled water for daily use, including one pregnant woman. Some of them even called the “12345” citizen complaint line, hoping to receive a timely and proper resolution. Until a solution was found, the residents continued to live with a dysfunctional secondary water supply system and the collective frustration it generated, yet they lacked a channel to express these shared feelings. We defined this as the “low emotional energy stage” in which their emotional resonance remained at a relatively low level, with anger and dissatisfaction dominating. However, this also indicates the preconditions for the initiation of a ritual. Identically, they had not established shared standards and rules for self-governance, or, in other words, the shared standards and regulations for solving public issues and asking for help from the government. When the traditional and former governance modes cannot meet the needs of residents or respond to their requests, co-creation between the government and residents exists. The process of building co-creation is an essential symbolic activity in which the organization, or the residents, tries to establish a normative alignment and standard rules between the contemporary central values of public administration and developments, both in public organizations and in society [84]. This created a key precondition of a successful interaction ritual: a shared focus of attention and an impulse towards emotional entrainment. In other words, interaction rituals translate human prosocial impulses into an ongoing, pulse-by-pulse production and reproduction of collective cohesion, or what we also call social order [72]. Liao et al. [72] called it “emergent solidarity”, which is a causal factor in interpersonal influence situations, requiring a genuine commitment to the momentary coalition to ensure its conformity. Although their solidarity lacked a formal structure, relying solely on a WeChat group for communication without formal agendas, the subject itself, i.e., access to clean water, which is a survival and safety issue, can naturally bond everyone’s interests together. Public affairs can be the breeding ground for interaction rituals, which can grow into a mutual co-governance framework.

On the other hand, studies have proved that the single governance mode of top-down administration is not always omniscient. Speer [84] mentioned that within the context of austerity and many upcoming social challenges, such as aging and urban regeneration, policymakers and politicians have found that the co-creation and coproduction mode with citizens is a necessary innovation to provide better public services that can actually meet the needs of a city’s daily operations. This case study of a safe water supply, however, demonstrates that these shifts in public administration can be entirely resident-driven. The direct threat to their lives can expand the sense of participatory governance, as they appear as extensions of the state’s capacity of sense, but they still have constraints due to the categories of use that the policies and systems operate [12].

4.2. The Injection of Ritual Ingredients

Leadership as the Initial Engine

In our case study interview, most of the residents mentioned that they had to work and did not have enough time to communicate and negotiate with the property management. Due to the situation in which the resident committee and property management could not find a direct and clear solution immediately, leaders were selected to represent the majority. The selection procedure was not rigorous, but the candidates were more or less passive and automatic in becoming the representative. During our investigation, we found two types of leaders and named them “formal” and “informal” leaders. The formal leader is the director of the resident committee, a veteran living within the housing estate but not in the affected building. The director of the resident committee, by concept, operates across four dimensions, including deliberation, decision-making, implementation, and oversight, as the pivotal node in residents’ self-governance. Internally, he convenes and presides over the residents’ assemblies and committee meetings, schedules the agenda for communal affairs, mediates among diverse interests, and steers the formation of enforceable resolutions. Externally, the director also acts as the legal representative of all residents in negotiations, contracting, and monitoring with property management firms, government agencies, and other third-party organizations. He helps to ensure the quality of the service and other fee transparency issues while also securing policy support and resources to safeguard and enhance collective assets. In sum, he was selected by all the residents, who considered him the person who could protect their benefits, defuse neighborhood disputes, and cultivate a spirit of communal citizenship, thereby translating the collective will of residents into sustainable community governance within the bounds of laws. At the same time, the other leader is a group of young people that consists of government officials working with merchants and pregnant women, who have much higher concerns with livelihood safety issues. Those with a keen interest in related matters would become the driving force, actively propelling progress forward.

“I was the one who took the lead in trying to solve the problem because water is the source of life. How can the body hold if we drink so many heavy metals? We have little infants who were just born, and it can cause a lot of damage to their brains and destroy their whole lives.”(Interview Code: 20241211211302).

Although Collins does not emphasize leadership in the theory of IRC, it is an element that cannot be ignored in community-based governance. Good managerial leadership is an indispensable part of supporting the success of a community-based governance model [3]. Community leaders can act as not only intermediaries between internal community residents and external partners, but also as the promoters of an internal agreement within the community [10]. They typically possess richer local knowledge and cultural literacy, which earns them considerable trust and effective communication skills with the community. This local credibility, in turn, allows them to grasp residents’ interests and demands more acutely. That is to say, the negotiation process demonstrated the volunteers’ strong leadership and managerial skills, which were essential for fostering community leadership and independence throughout the project. However, a high degree of government involvement is still required to reach a balanced position [52] (McLennan, 2020). In our case study, the community leaders provided a twofold layer of protection. From a procedural perspective, the director of the resident committee is legally vested with the duty to handle the residents’ requirements, thereby furnishing the negotiations with formal feasibility. On the other hand, the self-formed resident leadership group mobilizes cultural and moral legitimacy, which informally expresses the voice, ideas, and interests of the community and provides credibility and persuasive power emotionally. The two types of community leadership reinforce each other and jointly promote the reconstruction of the secondary water supply system, which is an initial engine that sets the entire process in motion.

Group Assembly as the Main Ritual

As we mentioned in Section 1, the term “rituals” in this article does not only refer to its narrow and traditional sense of religious or ceremonial rites related to supernatural beliefs in a god, specific sacred locations, like churches, fixed actions, such as prayers, chanting, confessions, or celebratory gestures. Instead, we adopt a broad sociological definition of a ritual as a standardized pattern of interaction that generates and reinforces social bonds. We defined the concept “rituals” based on Collins’s theory of IRC, which states that the core lies in its function and effect, rather than its form. It refers to any group of people who, while facing shared difficulties or situations, develop a common focus of attention through repeated interactive processes. These structured exchanges facilitate the transformation of personal and individual emotions into collective emotional resonance and group solidarity. Essentially, this process is often reinforced by the establishment of symbolic boundaries against outsiders, whether through physical presence, shared identity, or exclusive channels of communication, which strengthens internal cohesion and enhances a sense of belonging among participants. It broadly encompasses seemingly ordinary collective activities undertaken by community residents for the water pipe reconstruction, such as online WeChat group discussions, offline consultation meetings, and door-to-door mobilization. They effectively fulfill the sociological function of generating emotional energy and group solidarity, thereby driving the sustainability and success of collective actions. Notably, the concept of “rituals” is evolving alongside the digital transformation brought by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Digital transformation can vastly improve transparency and accountability both in life communication and governance [85]. The proliferation of digital media and smart devices has significantly altered the conditions under which rituals occur and the forms they take.

Meetings between the residents and the property management were the first main form of rituals we discussed, where every resident was invited to attend and interact within a physical space. During our interview, the director of the resident committee told us that he had first scheduled the meeting to facilitate the dialogue between the residents and the property management.

“The property management told me this (the reconstruction of the secondary water-supply systems) is not included in their responsibility, but belongs to the self-governance of the residents. I’ve also discussed with the water affairs department and the residents’ committee, but there is no direct and useful response. Therefore, to address the residents’ health concerns, I took the initiative to convene a meeting. I organized a meeting of the residents’ committee to seek opinions and advice because the reconstruction cost should be covered by the maintenance funds, which is financed entirely by the residents themselves. We posted a notice in the WeChat group, telling them that there is a meeting at six o’clock tonight at the courtyard between buildings 5 and 6, and everyone is welcome to join. It is totally voluntary.”(Interview Code: 20241210001).

Although every related resident was invited to the meeting, not everyone attended due to a real-life factor. Some owners were occupied with work or, as absentee landlords, felt unaffected by the issue. Meanwhile, the tenants, who were directly impacted, had no right to participate since they were not owners and did not contribute to maintenance funds. At this stage, the meeting, as a ritual, came into play as a part of the consolidation and conversion of power. Those who went to the meetings thought of themselves as the masters of the building, who naturally enjoy the right and power to ask for a proper solution. Those who were absent, for whatever reason, effectively delegated their own power and rights to the attendees by their absence, enabling the latter to exercise authority on their behalf. They described this as follows:

“It’s enough for the key activists to attend. We will sit this one out.”(Interview Code: 2024121121301).

“I saw the meeting notice in our WeChat group, but I was tied up at work and could not go. I heard from my neighbors that someone stepped up as the leader for us and negotiated on behalf of all the residents. Everyone in the WeChat group had been calling loudly for the reconstruction of the water pipes, so I felt it was okay to miss the meeting, because I knew the project would still be moving forward.”(Interview Code: 20241211211404).

In a successful interaction ritual, participants focus their attention on the same object or activity, and this shared focus gives rise to a collective consciousness [68]. There was no doubt that all the residents living in buildings 20 and 21 had the same concerns with the reconstruction of water pipes and also had no objection to maintaining water safety as a fundamental human right. According to Collins [68], only bodily attendance cannot automatically drive out group solidarity, but it emerges only when participants enter a state of “interaction”, which is a self-reinforcing cycle in which synchronized body rhythms and intensifying emotions mutually amplify one another. When a country or a group with the same interests, benefits, and identities faces shared adversities and crises, group identification can be essentially strengthened among individuals and enhance their sense of communal belonging [82]. The interviews revealed that the ordinary residents showed great confidence and trust in the leader they formally or informally chose, as the WeChat group had become a prepositional ritual that brought confidence to the promotion of the conversion of power exchange. Despite the absence of physical co-presence, sensory engagement, and natural settings typical of in-person rituals, the participants nonetheless sustained a palpable sense of mutual connection [86]. Although they did not share a physical ritual space, they were connected through the same WeChat group, or, abstractly speaking, tied with the same rope of solving water safety issues that shared the same ritual identities. In the modern era, public protests function as “moments of collective cohesion” that are intensified through social media, which significantly deepen the personalization of involvement within collective action [87]. Ma et al. [82] indicate that, unlike the top-down identity construction that relies on old common memories through imagination, this bottom-up approach is based on socio-cultural spontaneity that contains folk culture, daily interaction norms, and existing governance behaviors. Interestingly, modern communication tools like WeChat have mediately enhanced the interaction ritual chain by enabling real-time news within groups, thereby eliminating the information asymmetry caused by message delay.

Door-to-Door Canvassing as the Variant Ritual

All the interviewed families told us that they did not doubt the reconstruction issues, but they had a deeper discussion on choosing the proper construction units. According to both the director of the resident committee and the voluntary ones, three construction companies were recommended. One was recommended by the property management company, one was recommended by the resident committee, and the third was recommended by the residents themselves. All three companies provided a budget statement outlining the materials, the unit prices, the total cost, and the time of completion. The voluntary leaders stated that they visited every family living in buildings 20 and 21, explained the situation, and asked which companies to choose for the construction. The residents also provided the following comments:

“They came to visit my house to collect opinions. They gave me a piece of paper and offered three plans to choose from. Each plan differs by roughly a few tens of thousands of yuan. We had no idea which one to choose, and they gave a recommendation. We just chose what they recommended.”(Interview Code: 20241211201203).

“They came to everyone’s house for opinions and signatures. They did a lot on this case.”(Interview Code: 2024121121603).

“I forgot which company I actually chose. I expressed my opinion that my choice would be the company with the best quality, irrespective of the price, and they recommended.”(Interview Code: 2024121121503).

The leading group also provided a reason for their recommendation, which was totally based on the perception of good quality without any selfish motives:

“I am working in government investment promotion, so I have access to every company’s credentials. I can look them all up on whatever projects they have handled, whether they are registered with the housing and construction commission or have any other licensing details. There is no doubt we should choose and recommend a firm that is fully licensed and has paid-in capital in place with solid financial strength. We cannot take any risk if something goes wrong, and the residents’ lives would be at stake.”(Interview Code: 202412111302).

Some residents mentioned that the leading group conducted door-to-door visits more than once because certain actions had provoked strong dissatisfaction among the residents, which invalidated the initial vote. We discuss this in detail in the “Barrier to Outsiders” Section. Although the residents did not express it directly, we identified their appreciation and trust towards the leading group through the usage of vocabulary and their attitudes. Collins [68] argued that the mechanism of interaction rituals produces a transient shared reality, thereby generating symbols of group solidarity and membership. Thus, “door-to-door canvassing” became a complementary ritual place that continued the process of emotional exchange following the plenary sessions. The members of the leading group, some of whom were driven by an innate sense of duty, whereas others were driven by interests closely tied to the case, went door-to-door to collect opinions and votes. Their expertise and selflessness earned the trust of the residents, promoting expressions of gratitude and the delegation of agency, which, in turn, solidified the leading group’s authority and credibility as the community’s spokesperson. Fundamentally, it operates as an engine powered by converging currents of emotional energy [88]. The emotional exchange thus upgrades to affective resonance caused by emotional synchronization. As individuals perceive one another’s emotional response and reciprocate with their own expressions, emotional energy is transmitted and amplified. This resonance not only intensifies their emotional experience; it also strengthens the group’s cohesion, which helps set barriers to outsiders or to damage from the outside. The vote and canvassing used the principle of majority rule, that the issue under discussion could be passed if 50% of the whole agreed. We were informed by both the voluntary leader and the director that buildings 20 and 21 agreed to the reconstruction of water pipes, with just over 50% in favor of the first vote, and the same for the second one, showing the robustness of the firm determination of those who insisted on the reconstruction program. Also, the residents chose the construction company recommended by the residents themselves, although it was the most expensive one among the three choices.

Barrier to Outsiders as the Ritual Threshold

As shown above, the residents within the ritual chain displayed strong internal solidarity and tolerance while simultaneously vigorously opposing any individuals who sought to obstruct their activities for self-interest.

In our case study, the outsiders were the householders who rented their apartments to tenants and did not live in the building, as well as the deputy director of the resident committee. Three out of the fifteen interviewees mentioned difficulties in asking these householders to agree to the water pipe replacement, as they were not included in the emotional exchange group since they did not physically live there or face the water safety problems by definition. On the other hand, the deputy director of the resident committee was also a big obstacle. Since the residents did not choose the company he recommended, he refused to affix a seal to their proposal. Our interviewers described the situation as follows:

“The deputy director recommended a construction firm that has no credentials at all, which is literally a “three-no” shell company. I checked, so I knew it. If we refused to hire them, he would lose whatever kickback he was counting on. This was where the obstruction was located. The repair fund is controlled by the residents’ committee, and it takes the signature and seal of both its legal representatives to release any money. As long as he withholds his approval, the whole deal is dead in the water.”(Interview Code: 20241211211302).

“He kept harassing the elderly residents who were reluctant to spend the money again and again. One old man in our building even claimed that consuming the rust from my own iron wok could, in his view, provide a supplemental source of iron. It is so ridiculous, and it felt like a huge roadblock. Things escalated so far that we once marched straight from the residents’ committee office to the community office, and even brought in a certain official from the water authority. Mr. Chen (one of the voluntary leaders) showed up with a bottle of tap water drawn straight from his faucet and dared the deputy director to drink it.”(Interview Code: 2024121121701).

A genuine dilemma emerged. On the one hand, the deputy director was himself a resident of buildings 20 and 21, and thus naturally thought of as an insider by definition. On the other hand, his private agenda diverged sharply from the majority’s demand; while publicly endorsing the water pipe reconstruction project, he sought to line his own pockets, without putting water safety at the forefront. Thereby, it was very easy to identify him as an outsider and marginalize him. Insiders can readily spot anyone who violates community norms and consequently withhold genuine identification with that person. When insiders can decide by themselves who may join, such as admitting only those who promise to follow their shared rules and excluding those who refuse or destroy the rules, they lay the groundwork for deeper trust and reciprocal cooperation [89]. Some of the residents suggested excluding him from the process and moving on to the subsequent steps as a form of exclusion. However, such an action is legally impermissible under procedural rules. In this scenario, ritual participants violate the symbols of group membership and cause the loss of social capital, whether it is inadvertent or purposeful [74]. To address this problem, Mr. Chen (one of the voluntary leaders) advised him of the character of the residents and tried to describe the stakes to him. Whether because he resided in one of the affected buildings or because his signature and seal were ultimately needed, the residents were inclined to reintegrate him into the group. They initiated a friendly conversation to bridge the gap. According to Mr. Chen, he and the director sat down face-to-face at the resident committee’s office. After nearly an hour of discussion, during which the benefits and advantages of the proposal were carefully explained, he finally agreed to sign.

4.3. Ritual Outcomes and Their Spillover Effect

After 10 months of construction, the reconstruction of the secondary water supply systems of buildings 20 and 21 was finally completed. Table 3 illustrates the full phases of the social rituals process in a community’s public issue governance through participatory co-governance. All of our interviewees reported that there were no problems with the usage of water. Different from the original IRC theory proposed by Collins, there seems to be no specific symbolic or ironic patterns in this case study that were repeatedly invoked in the rituals or became emblems of collective identity and solidarity. However, we conclude it as a behavior. In fact, the residents of Jinshan District have come to regard self-governance over community public affairs not only as legitimate and rule-conforming but also as a highly effective framework of governance in its own right when top-down governance falters or fails to address concrete problems of daily life. The mindset of self-governance has itself become a ritual symbol. It makes individuals feel joyful when they have a functional and purposeful interaction with similar people and allows them to continue working within the group, which is addictive and necessary [73]. That is to say, the feelings and influence forged through these linked interaction rituals radiated outward, producing substantial and beneficial spill-out effects [90]. Overall, 80% of all the interviewed families (12 out of 15) mentioned that they thought it was necessary and are looking forward to having community governance when the property management is unstuck. We defined this as the stage of “high emotional energy and resonance”, where the successful completion of the water project served as a powerful validation of the collective effort. Interestingly, about 33.33% (5 out of 15) of them also mentioned the issue of elevator replacement. The “high emotional energy and resonance” sought a new outlet, which is the replacement of the old elevators. However, the residents believed that replacing the elevators was more difficult than replacing the water pipes due to the significantly higher cost involved. They indicated that the brand of the elevator was reputable, blaming the issue squarely on the property management company’s failure to maintain it properly. The issues were debated both in the residents’ meetings and on WeChat groups, yet no consensus emerged. Some believed the elevator still worked and did not need to be replaced, while others insisted that it posed a serious safety hazard. The disagreement was also tied to the floor level, as residents living on the first or lower floors plainly worried less about the safety problems related to elevators than those living on higher floors, causing a slight rift in the solidarity that had previously held them together. “Blocking” thus occurs, referring to the stalling of social capital accumulation whenever opportunities for mutual gain are cut off [74]. The residents were forced to divide again into different ritual groups with different aims, which makes the situation more complicated compared to replacing water pipes, making the result of self-governance confusing and enigmatic.

Table 3.

Phases of the social ritual process in community-led public issue renovation.

However, on the other hand, the effect of interaction rituals seems to overflow to other, but still similar, social groups. The director of the resident committee stated that seven other buildings voted and successfully implemented the same water pipe reconstruction program after the completion of buildings 20 and 21. Once an interaction ritual chain has been repeated and validated as a “successful paradigm” within a community, the emotional energy and symbolic capital it unleashes do not remain confined to their point of origin. Instead, they spread rapidly along lateral networks to neighborhood ties, residents’ WeChat groups, and even subdistrict offices. When other social organizations facing similar governance dilemmas observe a ritual’s efficient mobilization, collective identity, and tangible outcomes, they tend to replicate the entire script. Each act of imitation simultaneously reproduces the original interaction ritual chain and reinvigorates its symbols, so the self-initiated replacement of aging iron water pipes, or any other public affair, evolves from a one-time event into a portable institutional template. Meng et al. [75] pointed out the long-term feedback effect to maintain the operation of subsequent interaction ritual chains, which is a vertical overflow, while we attempted to highlight the horizontal one. Collins’s explanation of the interaction ritual chain does not explicitly address the diffusion of ritual effects to bystanders. Nevertheless, by demonstrating how rituals enable individuals to act more effectively and smoothly [91], we can infer that rituals also propel others forward, even when those observers were never “insiders” to begin with.

4.4. Government Actions to Maintain Ritual Outcomes

While we have discussed the actions of the residents, we have yet to examine the government’s role in this co-governance process. In the previous sections, it was proven that water-related laws, policies, and regulations are set at the national or city level, largely ignoring what daily life is actually like for the people who must live under them [29], which may result in complaints from the public. If the general public puts an increasing amount of pressure on local authorities, in the hope that they are more responsive and provide broader public value, in general, it can lead to greater public initiative and voluntary participation [92]. Within the participatory co-governance framework, local authorities serve as a guarantee system, ensuring the proper functioning of public administration. In pursuit of citywide safety in secondary water supply, the government authorities followed these four steps.

Firstly, they defined the governance objectives explicitly. There is no doubt that secondary water supply systems in residential estates are the “last mile” of urban water delivery and directly affect the safety of thousands of households. In Jinshan District, among the estates built between 2000 and 2023, the secondary facilities of 239 estates have still not been taken over by the municipal network, and nearly half of them require retrofits. The goal of these retrofits is therefore to carry out targeted solutions tailored to the specific problems of each estate and ensure that residents enjoy a stable and safe water supply.

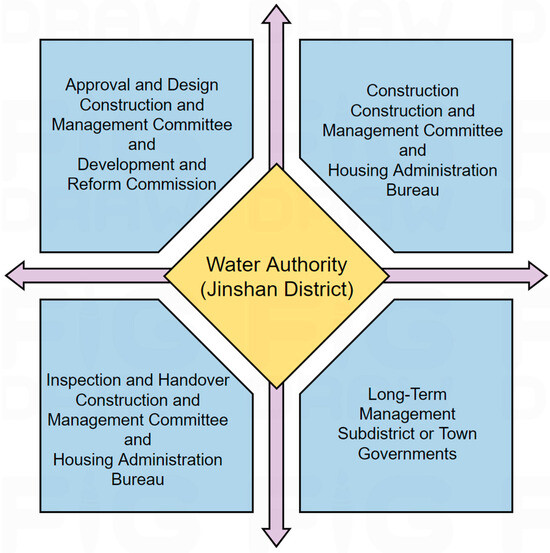

Secondly, they adopted a “four-quadrant” implementation pathway. In our case study, the reconstruction of the secondary water supply system in J Estate was structured into four sequential stages: approval and design, full-cycle construction, inspection and handover, and long-term management. We summarize these findings in a “four-quadrant” implementation roadmap (see Figure 4), which illustrates the overall leadership of the Jinshan District Water Authority by responsible entity and the management objectives for each stage. It ensured that every task is rule-based and that accountability is traceable, thereby improving the efficiency of secondary water supply governance. In the stage of approval and design, the Water Authority, Construction and Management Committee, and Development and Reform Commission jointly review the project design submitted by the water utility and the constructor against relevant industry standards and provide technical guidance. In the construction stage, the Construction and Management Committee, the Housing Administration Bureau, and the Water Authority supervise the constructor throughout the project, requiring prompt rectification of any deficiencies. In the inspection and handover stage, in accordance with applicable regulations, the same three agencies conduct rigorous document audits and onsite inspections before the formal handover. Until the end of the long-term management, the Water Authority scores and evaluates subdistricts or town governments quarterly and annually on their stewardship of secondary water facilities. These assessments are tied to the performance reviews of subdistrict leaders. Unified evaluation criteria, scoring rubrics, and standardized daily management logbooks are issued throughout the district. Additionally, a tripartite agreement is signed between the water utility, the resident committee, and the property management company, stating that the secondary water supply facilities are the common property of all homeowners. At the same time, the responsibility for daily operation, inspection, and maintenance is transferred to the water authorities. Routine patrols and upkeep are carried out jointly by the property management company, the Water Authority, and approved third parties to ensure long-term water quality for residents.

Figure 4.

The “four-quadrant” implementation pathway.

Thirdly, they drew on previous experience as a reference and refined it for better application. Nationwide experiences on secondary water supply generated from housing estates in China provided Jinshan District Water Authority with a proven reference model, especially in Changsha. Changsha introduced the “3-3-4” cost-sharing principle, under which a replacement project is financed 30% by the users, 30% by the district government, and 40% by the water authorities. For daily operation, Changsha formed a dedicated secondary water supply maintenance team that combines daily and monthly patrols for scheduled servicing and emergency repairs of all transferred pump rooms. In addition, Changsha also built a “Secondary Water Supply Management Platform” to keep existing automation intact while adding remote monitoring and data analytics. Following these steps, the secondary water supply team of Jinshan District applied the approaches to J Estate. For funding, public maintenance funds at the building-unit level were activated, and any shortfall was covered by direct contributions from the residents in the same units, resolving the tension between the tight fiscal capacity and the imperative to improve living conditions. In the operation stage, the tripartite agreement that we mentioned in the previous sections helps confirm that the secondary water supply assets remain the collective property of all residents, while the day-by-day operation and maintenance are transferred to the district water authorities. Routine inspections and servicing are carried out jointly by the property management company, the Water Authority, and approved third-party contractors to ensure long-term water quality. Additionally, online monitoring units were installed as well to provide real-time data to the district’s secondary water supply management platform. The integration of digital tools has become essential for modern public administration, as it enhances operational transparency, facilitates efficient communication, and reduces administrative barriers to effectively responding to the growing expectations of an increasingly digitally literate public [93]. Oversight and predictive maintenance can enhance both safety and efficiency, creating an institutionalized basis of trust that aligns the resources and routines of multiple departments into one coordinated operation system. Finally, they adopted delicacy management to solve problems that the residents may not be aware of. Government authorities have recognized the need to curb administrative costs while raising managerial efficiency. In our case study, problems such as the original misplacement, the poor placement of pump room sites adjacent to pollution sources, contaminants, and sewer lines, and improperly sized tanks that provide residents with inadequate pressure and flow all require targeted, fine-grained intervention and retrofitting. Jinshan District used sharing technologies to build an intelligent digital platform: it gathered experts and experienced workers to find solutions, asked a professional team to address problems that can determine success or failure, but can hardly be observed by residents, and enabled continuous supervision and performance evaluation. By meticulously planning, executing, and sustaining the secondary water supply systems, the district enhances governance standards and water quality, thereby safeguarding residents’ right to safe water access as a cornerstone of their pursuit of a better life.