Abstract

Supply chain financing offers advantages over traditional channels such as bank loans and equity financing, including greater flexibility, lower transaction costs, and simplified approval procedures. However, when a firm’s sustainability faces uncertainty, access to supply chain financing may become constrained by multiple factors, including the risk tolerance of supply chain partners, market transparency, and corporate reputation. ESG, representing Environmental, Social, and Governance standards, is a critical framework for assessing corporate sustainability performance. Given that divergent ESG evaluations reflect disparate market assessments of a firm’s sustainable development capabilities, such divergence may affect supply chain financing by altering stakeholder trust dynamics. This research examines A-share listed firms in China (2016–2022) and reveals that divergence in ESG evaluations significantly inhibits firms’ access to supply chain financing. Mechanism validation suggests that divergent ESG evaluations amplify informational opacity, operational risks, and negative reputation, thereby influencing supply chain partners’ risk perceptions and trust levels. Heterogeneity analysis shows that corporate governance quality, regional trust levels, and ESG awareness modulate the negative impact of divergent ESG evaluations on supply chain financing. The asymmetric effects of divergent ESG evaluations on supply chain financing are further confirmed, with distinct manifestations between upstream suppliers and downstream customers. By bridging gaps in existing research on divergent ESG evaluations and supply chain finance, this work offers regulatory guidelines, operational recommendations for firms, and investment decision frameworks.

1. Introduction

The global embrace of ESG principles reflects a fundamental shift in how businesses define value creation [1]. By aligning operations with sustainable development goals, companies transform into catalysts for the low-carbon transition while building long-term resilience [2,3]. This paradigm shift has elevated ESG considerations from peripheral concerns to core business imperatives, evidenced by the exponential growth of responsible investment frameworks worldwide. Investors, consumers and regulators now systematically integrate ESG metrics into decision-making processes, creating an urgent need for standardized performance evaluation [1,4]. It is this convergence of market demand and methodological complexity that gave rise to ESG evaluation [2,4,5]. However, ESG rating agencies employ divergent data sources and methodologies, leading to significant discrepancies in ESG evaluations among providers [4,6,7]. Such divergence in ESG evaluation reflects the uncertainty of the firm’s sustainable development, deteriorates its information environment, and brings negative economic consequences [8,9]. For example, some studies find divergent ESG evaluations lead to reduced equity and debt financing and increased financing costs [2,10,11,12]. Regarding the effects of Divergent ESG evaluations on firms’ external financing, existing studies predominantly focus on capital market financing, while limited attention has been paid to financing within supply chains, which relies not only on credit risk assessments but also on trust between supply chain partners [13,14].

As an important informal financing mechanism for a firm, supply chain financing offers advantages such as lower costs and reduced information asymmetry compared with traditional bank loans and equity financing [15]. Especially in China’s financial market, pervasive credit rationing restricts firms’ access to sufficient external financing, prompting reliance on supply chain financing as an effective alternative to sustain operations and growth [16]. Prior studies examine determinants of supply chain financing, including governance characteristics (e.g., managerial attributes) and external factors (e.g., disclosure quality, cultural norms) [14,17,18,19,20]. In addition, prior research explores the relationship between ESG and supply chain financing [21,22,23], but the findings remain inconsistent. Research suggests that ESG disclosures complement financial information by reducing information asymmetry [24], while strong ESG performance signals sustainability and lowers operational risks, facilitating supply chain financing access. On the other hand, firms engaging in ESG activities may reflect managerial opportunism due to agency problems However, the instrumental use of ESG practices may engender adverse effects, wherein executives leverage ESG initiatives to entrench their control while concealing operational inefficiencies and financial irregularities, thereby exacerbating agency costs and harming operational performance [25], which undermines the access to supply chain financing.

Notably, a critical oversight in prior research lies in the chronological accessibility of ESG evaluation data. To illustrate, although Sino-Securities Index Information Service retroactively assigned ESG ratings to 2009, its formal ESG scoring framework was only established in 2017. Consequently, stakeholders lacked access to these metrics for assessing corporate ESG performance prior to 2017, rendering pre-2017 analyses immaterial to real-world supply chain financing choices. Our study addresses this issue by excluding the Sino-Securities Index Information Service’s pre-2017 ratings to test its real impact. Furthermore, existing research predominantly relies on a single rating agency, ignoring the pervasive impact of divergent ESG evaluations on corporate supply chain financing. Theoretically, multiple ratings should provide incremental information, thus providing useful information for stakeholder decision-making [4,26]. However, under persistent divergence, divergent ESG evaluations exacerbate information asymmetry and operational uncertainty [8,9]. Whether the upstream and downstream supply chain partners react to divergent ESG evaluations in supply chain financing decisions remains underexplored. Accordingly, we investigate the effect of divergent ESG evaluations on corporate supply chain financing to fill this gap.

Three motivations drive our focus on China. First, China’s ESG rating market, emerging post-2015, exhibits greater rating divergence than developed markets, offering an ideal setting to examine ESG rating consequences [27]. Second, as a major global economy, Chinese firms face acute financing constraints during economic transformation, which have been a key factor restricting the high-quality development of firms [28,29,30]. Analyzing the financing behaviors of Chinese firms reveals the problems in the process of economic transformation. Third, China’s less-developed financial system may amplify the adverse effects of divergent ESG evaluations. In emerging markets like China, supply chain financing often plays a more significant role than bank loans in supporting corporate activities [31]. Exploring how Chinese firms cope with the negative effect of divergent ESG evaluations on financing will provide valuable insights for sustainable development on a global scale.

Drawing on 2016–2022 data from China’s A-share market, the paper examines the linkage between divergent ESG evaluations and corporate supply chain financing. We found that divergent ESG evaluations significantly limit firms’ ability to obtain supply chain financing, which is robust to various tests. Further analysis reveals that divergence increases information asymmetry, operational risks, and reputational damage, affecting the risk perception and trust level of firms upstream and downstream in supply networks. Heterogeneity tests indicate that the adverse impact becomes stronger in firms with poor corporate governance, lower regional trust levels, and high social ESG awareness. Additionally, divergence primarily reduces supply chain financing from suppliers, with no significant impact on advance payments from customers, suggesting asymmetric effects across supply chain tiers. Meanwhile, we find that divergence reduces supply chain financing from upstream suppliers and has no significant impact on advance payments from downstream customers, revealing an asymmetric contraction effect induced by ESG discrepancies.

Our research includes the following potential contributions: First, it extends the studies on divergent ESG evaluations by shifting focus from equity and debt financing in the capital markets to supply chain financing, which is an important form of external financing channels for firms [2,8,10,11,12], advancing knowledge about how divergent ESG evaluations propagate through financing networks. Second, this paper enriches research on supply chain financing determinants by introducing third-party divergent evaluations. Current research predominantly investigates how corporate governance and external environment characteristics affect supply chain financing [14,17,18,19], whereas we empirically examine the role of third-party information intermediaries. Finally, this paper provides empirical evidence on whether multiple ratings generate incremental information or noise [4,26], offering theoretical support for standardizing ESG rating systems and thus mitigating the market distortions caused by divergent ESG evaluations.

We structure the paper as following sections: Section 2 synthesizes prior literature and formulates testable hypotheses. Section 3 elaborates on the research design and analytical methods. Section 4 presents the core empirical results, while Section 5 interprets these findings and offers concluding remarks.

2. Synthesis of Prior Research and Proposition Formulation

2.1. Determinants of Supply Chain Financing

Supply chain financing emerges as an equilibrium driven by supply and demand dynamic [31]. There are two dominant theories that explain supply chain financing as a supply-demand equilibrium phenomenon, namely alternative financing theory and the buyer’s market theory. The alternative financing theory posits that firms constrained by bank credit rationing turn to suppliers or customers for supply chain financing, making it a critical financing channel [32,33]. Similarly, studies find that firms with access to diverse financing sources rely less on supply chain financing for financing [34]. The buyer’s market theory suggests that firms with strong market power or reputational advantages dominate supply chain relationships, enabling them to take advantage of supply chain financing by deferring payments to suppliers or customers [35,36,37]. From the perspective of dynamic capability theory [1,38], this equilibrium further reflects firms’ strategic adaptation to financing environment volatility through supply chain relationship restructuring.

While firms benefit from the liquidity and resource advantages of supply chain financing, not all of them have access to supply chain financing as much as they would like. Extensive research examines determinants of supply chain financing, including corporate governance characteristics and external environmental factors. Within corporate governance frameworks, scholars have identified the causal effects of management characteristics [18,39], ESG performance [21,22,23], corporate strategy [40], and information disclosure [17,19] on supply chain financing. Regarding the external environment, scholarly work reveals the transmission mechanism of economic policy uncertainty, fiscal regulation, and cultural factors on supply chain financing [14,41,42].

2.2. Economic Consequences of Divergent ESG Evaluations

Current literature predominantly investigates how divergent ESG evaluations adversely affect capital market financing. Academic consensus indicates that such divergence generates sustainability assessment uncertainty while simultaneously elevating perceived operational risk signals, which in turn raises risk compensation requirements from both investors and creditors, as well as amplifies equity return fluctuations [2,8,10,12]. Based on an informational dimension, researchers contend that divergent ESG evaluations exacerbate market information asymmetries and diminish the predictive utility of ESG disclosures, leading to bond yield spread expansion, deterioration in financial analyst forecast accuracy, and increased audit service costs [9,11,27,43]. Limited evidence exists regarding corporate strategic adaptations to divergent ESG evaluations, with isolated studies documenting responses including intensified green technology development and proactive earnings manipulation [44,45].

Notwithstanding the mature ESG research tradition, the economic implications of divergent ESG evaluations constitute an underdeveloped research domain. Existing scholarship concentrates on traditional financing channels (equity/debt markets), while neglecting supply chain financing—a critical external funding mechanism for enterprises. Furthermore, studies examining corporate ESG performance’s influence on supply chain financing fail to account for multi-source ESG assessment discrepancies.

2.3. Divergent ESG Evaluations and Supply Chain Financing

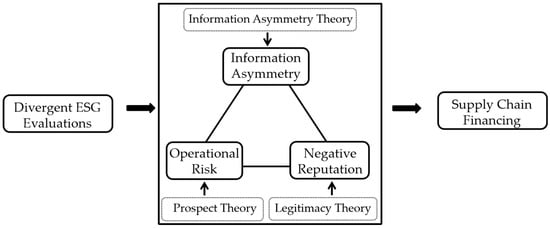

This research posits that divergent ESG evaluations signify corporate sustainability assessment ambiguities, consequently exacerbating information asymmetry levels, operational risk exposure, and reputational capital erosion. These multidimensional impacts operate through three distinct transmission mechanisms: informational intermediation, risk propagation, and reputation spillover effects, ultimately influencing enterprises’ supply chain financing capabilities.

First is the information channel. According to information asymmetry theory, information asymmetry and the associated moral hazards are the primary concerns of suppliers when providing supply chain financing [18]. Since suppliers do not require customers to provide guarantees or collateral, once the customer defaults, the supplier will face significant loss [14]. Low firm information transparency hinders suppliers’ ability to assess their customers in terms of asset quality, profitability, and creditworthiness, leading to reduced supply chain financing allocations. Stakeholders increasingly incorporate ESG factors into decision-making, heightening demand for ESG information [4]. While effective ESG evaluations can ideally mitigate information asymmetry, pervasive divergence renders a firm’s ESG information less effective as a decision-making reference for stakeholders but instead confuses valuable information. Empirical evidence demonstrates that divergent ESG evaluations intensify market-level informational asymmetries [9], reduces firm information transparency, and introduces uncertainty in corporate sustainable development [8]. Divergence raises suppliers’ information acquisition costs, complicates risk assessments of a firm’s repayment capacity, and brings concerns about managerial opportunism [45]. Thus, divergent ESG evaluations can negatively impact supply chain financing by intensifying corporate information asymmetry.

Second is the risk channel. When a firm in the supply chain gets into financial distress, its credit risk will be transmitted along the supply chain and adversely affect other firms [46]. According to prospect theory, increased uncertainty can lead to loss aversion among decision-makers. Therefore, the “credit risk contagion” effect compels suppliers to intensify scrutiny of customer business default exposures. Due to the unsecured and non-interest nature of supply chain financing, suppliers providing supply chain financing need to bear the risks of payment defaults and operational disruptions, as well as bear higher management costs, thus driving them to favor low-risk customers. Divergent ESG evaluations signal potential sustainability uncertainty, prompting banks to tighten credit and investors to demand higher risk premiums [10], thereby increasing debt and equity financing costs and harming the firm’s operation. Moreover, ESG risks conveyed by divergent ESG evaluations may destabilize inter-organizational partnerships within the corporate supply network and elevate fluctuation risks in projected income streams, thereby compromising business continuity resilience. Consequently, divergent ESG evaluations can negatively affect a firm’s access to supply chain financing by increasing its operational risks.

Third is the reputation channel. Reputation theory highlights that a strong reputation is an essential intangible asset in imperfect information environments [47]. China’s sustained economic expansion has brought fierce competition in the market. Hence, reputational capital enhances corporate competitiveness. It has been found that positive media coverage improves firms’ reputations, reduces the risk perception of suppliers, and thus significantly increases access to supply chain financing [48]. While firms with divergent ESG evaluations convey to the outside an “adverse signal” about potential failures in environmental, social, or governance practices, they are more likely to attract negative media attention, which in turn damages their reputation [49]. From the perspective of legitimacy theory, the divergence of ESG ratings has a corrosive effect on the social legitimacy of firms. Since supply chain financing inherently relies on mutual trust between supply chain partners [13,14], the legitimacy damage from divergence discourages suppliers from providing credit.

In summary, we believe that divergent ESG evaluations negatively affect supply chain financing by increasing information asymmetry, operational risks, and reputational damage (Figure 1). Accordingly, our hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1.

Divergent ESG evaluations demonstrate a significant adverse linkage to the firm’s access to supply chain financing.

Figure 1.

Research Framework Diagram.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Construction Methodology

The research employs panel data comprising annual observations of A-share listed companies spanning the 2016–2022 period. To calculate the divergent ESG evaluations index, coverage from at least two rating agencies is required. Considering both data accessibility and the market prominence of ESG evaluation institutions, our analysis incorporates ESG evaluations from four agencies: Huazheng, Wind, SynTao and CASV. Additional sample adjustments include: (1) exclude ST/*ST firms; (2) exclude samples covered by less than two rating agencies; (3) exclude samples of financial firms; (4) exclude samples with missing data on the key control variables; (5) lag independent variables by one period. The final sample obtains 9142 firm-year observations. The online media coverage data are from the CNRDS database, and supply chain financing and other variables are from CSMAR. To control for outlier effects, we apply 1% winsorization to the upper and lower tails of continuous variables.

3.2. Model Specification and Variable Definitions

To evaluate the potential influence of divergent ESG evaluations to supply chain financing, we specify the baseline econometric specification:

SCFi,t = β0 + β1ESGdivergei,t−1 + Controlsi,t + Ind FE + Year FE + εi,t

Among them, SCFi,t is firm i’s access to supply chain financing, measured as the ratio of accounts payable, notes payable, and advance receipts to total assets in year t [13]. ESGdiverge i,t-1 is firm i’s divergent ESG evaluation in year t − 1, measured by the standard deviation of ESG scores of different rating agencies [6]. Given differing rating scales, scores are standardized to a “1–10” range using: Score = [(Xi − Xmin)/(Xmax − Xmin)] × 9 + 1. For example, SynTao’s 10-tier ratings (A+, A, A−, B+, …, D) map to scores of 10, 9, 8, 7, … 1, while Huazheng’s 9-tier ratings (AAA, AA, A, BBB, …, C) map to 10, 8.875, 7.750, 6.625, 5.500, 4.375, 3.250, 2.125, 1. Referring to previous studies [14,19], the control variables (Controls) in this paper mainly include average ESG rating (AveESG), firm size (Size, log of total assets), leverage (Lev, total liabilities/assets), profitability (ROA, net income/assets), operating cash flow (CFO), market power (Power, revenue/industrial revenue), ownership concentration (Top1, the largest shareholder’s stake), board size (Nboard), independent director ratio (RIboard), state ownership (Soe), and firm age (Age) [14,19]. Our model incorporates industry and year fixed effects, with firm-level clustered standard errors. Detailed variable measurements are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Detailed variable measurements.

4. Results

4.1. Data Overview

Table 2 presents data overview for key variables. Supply chain financing (SCF) has a mean value of 0.142 (standard deviation = 0.104), ranging from 0.004 to 0.473, indicating significant variation in the level of supply chain financing across firms. Divergent ESG evaluations (ESGdiverge) show a mean of 0.924 (standard deviation = 0.643), with values spanning from 0 to 2.828, demonstrating substantial dispersion in corporate rating divergence.

Table 2.

Data Overview.

4.2. Baseline Results

To examine how divergent ESG evaluations affect supply chain financing, Model (1) is estimated with financial characteristics and market position controls. As shown in Column (1) of Table 3, the coefficient on ESGdiverge is −0.004, which is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. Column (2) is the regression results after further controlling for corporate governance characteristics, yielding a coefficient of −0.004 for ESGdiverge, which is still significant at the 5% level. These results support Hypothesis 1, indicating that firms with higher divergent ESG evaluations tend to secure significantly less supply chain financing.

Table 3.

Baseline results.

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Endogenous Alleviation: Propensity Score Matching

Using the median of ESGdiverge, we split the sample into treatment and control groups. Using all control variables in the model (1) as covariates, we apply 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching without replacement. In the resulting matched samples, the two groups exhibit statistically indistinguishable firm characteristics. Post-matching regression results (Table 4, Column 1) report a statistically significant coefficient of −0.003 for ESGdiverge (p < 0.05), reinforcing the baseline findings.

Table 4.

Endogenous alleviation.

4.3.2. Endogenous Alleviation: Difference-in-Difference Model

We exploit the 2019 revision of the ESG Reporting Guidelines by the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX) as a quasi-natural experiment, which expanded the scope of mandatory disclosure. Enhanced mandatory ESG disclosure likely amplifies rating divergence because the diversified indicator data gives rating agencies more independent choices [8]. Using PSM-matched samples, which are divided into treatment and control groups according to whether they are also listed in Hong Kong, we classify firms dual-listed in Hong Kong and mainland China as the treated observations (Treat = 1) and 0 otherwise. Post takes 1 for years after 2019, and 0 otherwise. Treat × Post is the cross-multiplier of the two, and the rest of the variables remain the same. The DID model is:

SCF = α0 + α1Treat × Post + α2Treat + α3Post + Controls + Ind FE + Year FE+ ε

Table 4, Column (2) shows the interaction term Treat × Post yields a positive and statistically significant coefficient of 0.272, demonstrating that divergent ESG evaluations increase after more mandatory disclosure. Column (3) reveals a negative net effect of Treat × Post on SCF (−0.025, p < 0.01), confirming divergent ESG evaluation adverse supply chain financing after addressing endogeneity with quasi-natural experiments and that the finding remains robust.

4.3.3. Endogenous Alleviation: Firm Fixed Effects

To mitigate potential omitted variable bias, we incorporate firm-level fixed effects to Model (1) (Table 4, Column 4). ESGdiverge continues to exhibit a significantly negative coefficient, confirming that baseline finding remains unchanged.

4.3.4. Other Robustness Tests

Following prior literature [50], we redefine divergent ESG evaluations (ESGdiverge2) employing the mean absolute deviation among scores across evaluation agencies. Table 5 presents regression estimates where ESGdiverge2 exhibits a statistically significant negative coefficient (−0.005, p < 0.05), corroborating the baseline findings. Referring to existing literature [31], we measure net supply chain financing (SCF2) as (accounts payable + notes payable + advance receipts—prepayments)/total assets (Column (2)), confirming result robustness. Additionally, since the ESG evaluation indices from the four agencies in the sample were released incrementally over the years, and some agencies rate only a subset of firms, hence, the observations in our sample include divergence calculated from 2, 3, or 4 rating agencies. To mitigate the potential influence of the number of rating agencies, we incorporate the count of agencies (Number) while keeping other variables unchanged (Column 3). All aforementioned tests verify the robustness of divergent ESG evaluations’ suppressing effect on supply chain financing.

Table 5.

Other robustness tests.

4.4. Mechanism Test

The theoretical analysis suggests that divergent ESG evaluations reduce supply chain financing by exacerbating information asymmetry, operational risks, and negative reputation. To argue whether the above channels are valid, we estimate Model (3):

where the mediating variables MedVars represent information asymmetry (Analyst), operational risk (SD_ROA), and negative reputation (NegNews). Following prior studies [21,23,48], we quantify information asymmetry through the analyst tracking measure. It is generally believed that analysts can increase the transparency of firm information and reduce the degree of information asymmetry [51,52]. The operating risk (SD_ROA) is measured by the volatility of return on assets, which is defined as the standard deviation of return on assets from t−1 to t + 1 years of listed firms. It is generally believed that the greater the volatility of a firm’s earnings, which implies a more unstable operation [53], the lower the likelihood of repaying suppliers in full and on time. Corporate negative reputation (NegNews) is operationalized through the annual count of firm-specific negative online media reports. It is generally believed that negative media coverage implies and conveys risk information, which will affect stakeholders’ risk perception of the firm [54].

MedVarsi,t = γ0 + γ1ESGdivergei,t−1 + Controlsi,t + Ind FE + Year FE + εi,t

Table 6 shows the results of mechanism testing. Column (1) demonstrates that divergent ESG evaluations significantly reduce analyst coverage, validating the information asymmetry channel. Therefore, the information channel is validated. Column (2) reveals that divergent ESG evaluations increase earnings volatility, confirming the operational risk transmission mechanism. Column (3) establishes that divergent ESG evaluations induce negative reputation effects, thereby verifying the reputation deterioration channel.

Table 6.

Mediation tests.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

Prior studies suggest that corporate governance quality and external environmental characteristics will influence firms’ access to supply chain financing [14,18]. For example, disclosure transparency and agency cost will significantly affect the supply chain partners’ information-seeking cost and risk perception, while external factors such as regional trust levels and ESG awareness influence suppliers’ trust and sustainability concerns. This leads us to further examine how governance quality and external environmental characteristics moderate the association between divergent ESG evaluations and supply chain financing.

4.5.1. Governance Quality

Higher disclosure quality enables supply chain partners to access more reliable information about a firm’s financial condition and credit risk, signaling the firm’s commitment to stakeholder interests. Therefore, it is expected that high-quality information disclosure helps alleviate the adverse effects stemming from divergent ESG evaluations on the firm’s access to supply chain financing. We measure disclosure quality using stock exchange ratings, classifying firms with “excellent” or “good” ratings as high disclosure quality and those with “pass” or “fail” ratings as low disclosure quality. The empirical findings presented in Table 7 demonstrate significant heterogeneity across disclosure quality tiers. Specifically, the high-disclosure cohort (Column (1)) exhibits a statistically nonsignificant association between ESGdiverge and supply chain financing. In contrast, the low-disclosure group (Column (2)) manifests a pronounced negative correlation, suggesting that the adverse impact of divergent ESG evaluation is contingent upon disclosure transparency levels. This pattern implies that superior disclosure practices attenuate information asymmetries, thereby alleviating supply chain partners’ risk aversion toward ESG assessment discrepancies.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity of corporate governance.

The magnitude of agency costs serves as a proxy for internal governance efficacy. Elevated agency costs amplify the probability of managerial self-dealing, thereby exacerbating suppliers’ apprehensions regarding monitoring expenditures and repayment reliability, ultimately impairing supply chain financing viability. Referring to [23], agency costs are operationalized as the ratio of aggregate operating expenses (comprising administrative and sales expenses) to total operating revenue. Subsequent median-split analysis delineates high versus low agency cost subsamples. The low agency cost cohort (Column (3)) displays a nonsignificant association between ESGdiverge and supply chain financing. Conversely, the high agency cost subsample (Column (4)) reveals a statistically robust negative correlation, suggesting that the deleterious consequences of divergent ESG evaluations are predominantly concentrated in firms with inferior governance structures. This bifurcation implies that well-governed enterprises, characterized by constrained agency costs, demonstrate greater operational compliance and consequently attenuate supply chain partners’ risk assessments regarding divergent ESG evaluations.

4.5.2. External Environment Characteristics

Trust constitutes a fundamental determinant in interfirm commercial transactions across supply chain networks, with substantial geographical heterogeneity in trust endowments. Empirical evidence demonstrates that enterprises situated in high-trust jurisdictions enjoy superior access to supply chain financing accompanied by accelerated repayment velocities [14]. This phenomenon suggests that regional trust capital simultaneously influences both the propensity of supply chain partners to extend financing and their risk assessment of counterparty default. Employing provincial-level trust metrics derived from CGSS database, we bifurcate our sample along the median trust threshold. Model (1) estimations presented in Table 8 (Columns (1)–(2)) reveal a statistically significant negative coefficient for ESGdiverge exclusively in low-trust regions, whereas high-trust areas exhibit no such association. This dichotomy implies that regional trust endowments serve as an institutional safeguard that effectively neutralizes the adverse financing consequences stemming from divergent ESG evaluations.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity of external environment characteristics.

In addition, while the concept of ESG can be traced back to 2004 globally, it is only in recent years that ESG has been emphasized in China. The global pandemic in early 2020 and China’s “dual carbon” goals announced at the 75th United Nations General Assembly in September 2020 have heightened people’s awareness of environmental and social challenges, which promoted the establishment of ESG awareness among Chinese firms. Therefore, ESG evaluations may have had a limited impact on stakeholders in the early years of our sample. We use year 2020 as a cutoff to split the sample into low and high ESG awareness groups. Results in Columns (3) and (4) in Table 8 show that the coefficient of ESGdiverge is significantly negative only in the high ESG awareness group, indicating that the negative effect of divergent ESG evaluations on supply chain financing is primarily observed in recent years, reflecting a temporal learning effect in the influence of ESG rating consistency on firms and external stakeholders.

Contextually, while ESG principles originated globally in 2004, their adoption in China gained momentum only recently. The confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) and China’s formal commitment to carbon neutrality at the 75th UN General Assembly catalyzed ESG awareness among Chinese firms. Our temporal analysis demarcates the sample at 2020, with Table 8 (Columns (3)–(4)) revealing that the negative ESGdiverge coefficient emerges exclusively in the post-2020 high-awareness period. This temporal pattern underscores an evolving stakeholder learning curve regarding ESG evaluation consistency’s materiality in financing decisions.

4.6. Further Analysis

4.6.1. Structural Analysis

Supply chain financing encompasses two distinct elements: accounts payable originating from upstream suppliers and advance payments received from downstream customers. To examine whether divergent ESG evaluations affect these components differently, we decompose supply chain financing into Payable (measured as (accounts payable + notes payable)/total assets) and Advance (measured as advance receipts/total assets) to re-estimate Model (1). Intuitively, firms face higher switching costs when replacing customers compared to suppliers. This structural difference implies that customers inherently possess stronger bargaining power. Following this logic, when firms experience significant ESG rating divergence, customers can leverage their superior bargaining position to reduce financing support. On the other hand, suppliers maintain stable financing provisions due to their weaker bargaining power and higher replaceability, regardless of ESG rating discrepancies. However, the empirical results in Table 9 demonstrate an inverse relationship between ESGdiverge and accounts Payable in Column (1). In contrast, Column (2) shows no statistically meaningful correlation between ESGdiverge and Advance. These results collectively suggest that ESG evaluation divergence exerts a predominantly negative influence on supplier-side financing mechanisms while maintaining a neutral impact on customer-side advance payments, thereby underscoring the existence of structural asymmetries in how ESG divergence permeates different tiers of the supply chain.

Table 9.

Structural analysis.

To elucidate this empirical phenomenon, we extend our analysis to investigate how divergent ESG evaluations affect both supplier stability (Stable_S) and customer stability (Stable_C). The stability of supplier-customer relationships plays a pivotal role in supply chain financing dynamics, evidenced by suppliers’ demonstrated preference for extending credit to long-term partners characterized by enhanced transparency and trustworthiness [55]. Referring to the existing literature [56], we quantify supplier stability through the annual retention rate of a firm’s top five suppliers, while customer stability is similarly measured by the retention rate of its top five customers. These metrics reflect relationship continuity, where higher values indicate more stable partnerships, particularly when involving sustained collaborations with major business partners. Our re-estimation of Model (1) using these stability measures as dependent variables (Table 9, Columns (3)–(4)) yields two key observations: First, divergent ESG evaluations exert a statistically significant negative impact on supplier stability, while showing no comparable effect on customer stability. This differential impact correlates with the distinct financial exposure across supply chain tiers—accounts payable to suppliers represent 13% of total assets versus merely 1% for customer advances. The substantial supplier credit exposure necessitates rigorous risk assessment, as firms with divergent ESG evaluations are perceived to pose higher default risks and require increased monitoring efforts. Conversely, the minimal financial exposure through customer advances results in downstream partners displaying relative indifference to divergent ESG evaluations. These findings collectively demonstrate tier-specific structural variations in how ESG evaluation divergence permeates supply chain financing mechanisms.

4.6.2. Divergent Sub-Dimension and Proactive Response

Previous sections have examined the impact of divergent ESG evaluations on supply chain financing. In this section, we further investigate how discrepancies in ESG sub-dimensions influence supply chain financing. A deeper analysis of ESG sub-dimension discrepancies is critical, as it provides a scientific basis for firms to optimize ESG disclosures and for regulators to formulate targeted policies.

Huazheng and Wind represent the sole data providers offering comprehensive ESG sub-dimension data, with available data series commencing in 2018. Utilizing these two datasets, we construct three divergence indicators encompassing environmental (Ediverge), social (Sdiverge), and governance dimensions (Gdiverge), which were subsequently regressed against supply chain financing variables. The regression outcomes presented in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 10 demonstrate that all three divergence measures exert negative influences on supply chain financing, with governance divergence exhibiting particularly pronounced statistical significance.

Table 10.

Divergent sub-dimension and proactive response.

The empirical evidence suggests that governance capability enhancement should be prioritized in corporate supply chain financing optimization strategies. Further verification is conducted using governance metrics from both Huazheng (HG) and Wind datasets (WG). As evidenced in Columns (4) and (5) of Table 10, the measurement results consistently indicate progressive improvements in corporate governance standards.

5. Conclusion, Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

5.1. Conclusions

This study employs a sample of Chinese A-share listed firms and finds that divergent ESG evaluations significantly adverse corporate supply chain financing. The conclusion that divergent ESG evaluations exacerbate supply chain financing still holds after propensity score matching, instrumental variable testing of exogenous policies, and multiple robustness tests. The mechanism analyses reveal that divergence impairs supply chain financing by increasing information asymmetry, operational risks, and negative reputation. Specifically, divergent ESG evaluations have led to a decrease in analyst coverage for companies, as well as an increase in earnings volatility and negative media coverage. Heterogeneity analysis shows that higher governance quality and regional trust levels mitigate the negative impact of divergent ESG evaluations on supply chain financing. In addition, divergent ESG evaluations demonstrate a temporal learning effect, becoming more pronounced over time. Moreover, divergent ESG evaluations exert supply chain financing is asymmetric between upstream suppliers and downstream customers, mainly reducing supply chain financing provided by upstream suppliers. Furthermore, discrepancies in the sub-indicators of ESG have been shown to negatively impact supply chain financing, with governance discrepancies having the most significant effect. As a result, when firms face negative evaluations regarding these discrepancies, they often choose to enhance their governance capabilities.

5.2. Discussion

The foundational research by Berg et al. [4] and Christensen et al. [8] on rating methodology heterogeneity forms the theoretical cornerstone of this study. Their arguments reveal that the discrete nature of ESG assessment frameworks stems from methodological variations rather than substantive performance differences among firms. This conclusion directly validates the transmission pathway through which information asymmetry exacerbates supply chain financing constraints. Our study further incorporates the interaction analysis paradigm proposed by Attanasio et al. [57]. Their empirical findings on how corporate environmental disclosure strategies trigger value transmission fractures provide theoretical grounding for explaining the micro-level mechanisms of supply chain trust attenuation. At the transmission mechanism level, unlike Wang et al. [58] who focused on stock price volatility effects or Mio et al. [12] who emphasized capital cost mechanisms, this study innovatively constructs a three-dimensional mediation model encompassing information transmission, operational risk, and reputation spillover. This model systematically elucidates the theoretical logic of supply chain networks responding to corporate uncertainties. By integrating these theoretical threads, this study not only verifies the unique network constraint effects in supply chain finance but also deeply analyzes the endogenous mechanisms through which core firms’ ESG controversies propagate nonlinearly along supply chains. These findings provide theoretical support for developing precise supply chain ESG collaborative governance frameworks.

5.3. Theoretical Implications

We uncover the underlying mechanisms through which divergent ESG evaluations constrain supply chain financing, offering significant practical and theoretical contributions to information asymmetry theory, prospect theory, and legitimacy theory.

5.3.1. Implications to Information Asymmetry Theory

This study examines the impact mechanism of divergent ESG evaluations on supply chain financing from the perspective of information asymmetry theory. While prior research predominantly focuses on information asymmetry arising from discrepancies in financial disclosures, this investigation delves into how inconsistencies in non-financial information, particularly ESG assessments, exacerbate information opacity within supply chains. The findings demonstrate that when market participants form divergent judgments regarding a firm’s sustainable development capabilities, information transmission efficiency is substantially impaired, thereby exerting material influence on financing decisions. This theoretical contribution extends the explanatory boundaries of information asymmetry theory into the domain of non-financial information.

5.3.2. Implications to Prospect Theory

Within the behavioral economics framework of prospect theory, the research systematically elucidates how divergent ESG evaluations shape risk perceptions among supply chain partners. The study reveals that disparities in ESG assessments trigger loss aversion among decision-makers, and even when corporate fundamentals remain stable, this psychological mechanism still intensifies financing constraints. Notably, enterprises at different nodes of the supply chain exhibit varying sensitivity to ESG divergence, a finding that provides crucial empirical support for the applicability of prospect theory in supply chain finance contexts.

5.3.3. Implications to Legitimacy Theory

From the standpoint of legitimacy theory, the research uncovers the corrosive effects of divergent ESG evaluations on corporate social legitimacy. When significant discrepancies exist among stakeholders’ evaluations of a firm’s sustainability performance, the organization’s social acceptance faces challenges that ultimately compromise its bargaining position in supply chain financing. The study further identifies that contextual factors including corporate governance quality and regional trust environments moderate this effect, indicating that legitimacy construction depends not only on corporate conduct but is also profoundly shaped by external institutional environments. These discoveries yield novel theoretical insights for the application of legitimacy theory within sustainable development contexts.

5.4. Practical Implications

This study advances the literature concerning the economic implications of divergent ESG evaluations and supply chain financing determinants, yielding actionable insights for regulators, enterprises, and supply chain participants. Specifically, Regulatory authorities should establish scientifically grounded and standardized ESG assessment frameworks that reconcile jurisdictional specificities with international benchmarks, particularly given evaluation discrepancies’ demonstrated amplification of information asymmetry, operational risks, and adverse media attention. Such frameworks would enhance metric consistency and cross-agency comparability across evaluation systems. For firms, increasing ESG investments and improving ESG performance are essential for achieving long-term sustainable development. Moreover, they should actively enhance the disclosure quality, as those with significant divergent ESG evaluations tend to have lower transparency, higher default risks, and poorer reputations.

Collectively, divergent ESG evaluations fundamentally undermine supply chain stability through distorted information efficiency and heightened operational risks. This systemic challenge demands coordinated reform among regulators, enterprises, and rating agencies to establish harmonized ESG evaluation frameworks. Such alignment is critical for bridging credibility deficits and securing sustainable green financing flows throughout value chains.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

This investigation identifies two methodologically interconnected limitations requiring nuanced interpretation. Quantification of divergent ESG evaluations necessitates synchronized multi-source assessments. China’s pre-2016 ESG assessment environment lacked the institutional infrastructure to fulfill this prerequisite. Such temporal truncation constrains the observational scope and may obscure significant transitional patterns in China’s ESG institutionalization trajectory. Future maturation of rating ecosystems will enable longitudinal verification through extended temporal datasets. Regarding sample coverage, the limited inclusion of Chinese A-share companies by international ESG rating agencies presents a significant constraint, preventing this study from distinguishing between the differential effects of divergent ESG evaluations from international versus domestic rating agencies. Notably, as international agencies expand their coverage of Chinese listed firms, subsequent investigations will benefit from more comprehensive data foundations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S. and X.H.; Methodology, G.S., X.H., X.C. and J.X.; Software, G.S., X.H., X.C. and J.X.; Validation, G.S., X.H., X.C. and J.X.; Formal Analysis, G.S., X.H., X.C. and J.X.; Data Curation, G.S., X.H., X.C. and J.X.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, G.S.; Writing—Review & Editing, G.S., X.H., X.C. and J.X.; Supervision, G.S., X.H., X.C. and J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Project under grant 23NDJC237YB; the Outstanding Innovative Talents Cultivation Funded Programs 2022 of Renmin University of China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it did not involve personally identifiable or sensitive data.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human or sensitive data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, X.; Song, Y.; Hu, X.; Sun, G. Sustainability Uncertainty and Digital Transformation: Evidence from Corporate ESG Rating Divergence in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, R.G.; Krueger, P.; Schmidt, P.S. ESG Rating Disagreement and Stock Returns. Financ. Anal. J. 2021, 77, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, G.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y. Interest rate marketization and corporate social responsibility. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 83, 107745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Sun, G.; He, Y.; Chen, H.; Guo, C. Culture and Sustainability: Evidence from Tea Culture and Corporate Social Responsibility in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, A.K.; Durand, R.; Levine, D.I.; Touboul, S. Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1597–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Q. Information Disclosure and ESG Rating Disagreement: Evidence from Green Bond Issuance in China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2024, 85, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Serafeim, G.; Sikochi, A. Why is Corporate Virtue in the Eye of The Beholder? The Case of ESG Ratings. Account. Rev. 2022, 97, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Stock price reactions to ESG news: The role of ESG ratings and disagreement. Rev. Account. Stud. 2023, 28, 1500–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, D.; Cheng, S.; Lioui, A.; Tarelli, A. Sustainable investing with ESG rating uncertainty. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 145, 642–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Yan, J.; Deng, G. ESG rating confusion and bond spreads. Econ. Model. 2023, 129, 106555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, C.; Fasan, M.; Scarpa, F.; Costantini, A.; Fitzpatrick, A.C. Unveiling the consequences of ESG rating disagreement: An empirical analysis of the impact on the cost of equity capital. Account. Eur. 2024, 22, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 526–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.F.; Firth, M.; Rui, O.M. Trust and the Provision of Trade Credit. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 39, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.A. An Economic Model of Trade Credit. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1974, 9, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.; Lin, C.; Xie, W.S. Corporate Resilience to Banking Crises: The Roles of Trust and Trade Credit. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2018, 53, 1411–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Q.; Liu, M.; Ma, T.; Martin, X. Accounting Quality and Trade Credit. Account. Horiz. 2017, 31, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Liu, Q.; Shi, H.; Wang, W.; Wu, S. Firms’ access to Informal Financing: The Role of Shared Managers in Trade Credit Access. J. Corp. Financ. 2023, 79, 102388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Chan, H.K.; Zhang, T. Who Pays Buyers for not Disclosing Supplier Lists? Unlocking the Relationship Between Supply Chain Transparency and Trade Credit. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Lu, C.; Sun, G.; Zhang, C.; Guo, C. Regional culture and corporate finance: A literature review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Tian, G. Corporate Sustainability and Trade Credit Financing: Evidence from Environmental, Social, and Governance Ratings. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1896–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Wei, D.; He, F. Corporate ESG performance and trade credit financing-Evidence from China-All Databases. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 85, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xiang, C. Do Suppliers Value Clients’ ESG Profiles? Evidence from Chinese Firms. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 91, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.J. Do Boards Take Environmental, Social, and Governance Issues Seriously? Evidence from Media Coverage and CEO Dismissals. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 176, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, I.; Hong, H.; Shue, K. Do Managers Do Good with Other People’s Money? Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2023, 12, 443–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongaerts, D.; Cremers, M.; Goetzmann, W. Tiebreaker: Certification and Multiple Credit Ratings. J. Financ. 2012, 67, 113–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dai, J.; Dong, X.; Liu, J. ESG Rating Disagreement and Analyst Forecast Quality. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, H.; Sun, G.; Tao, J.; Lu, C.; Guo, C. Speculative culture and corporate high-quality development in China: Mediating effect of corporate innovation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Cao, X.; Chen, J.; Li, H. Food Culture and Sustainable Development: Evidence from Firm-Level Sustainable Total Factor Productivity in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Sun, G.; He, Y.; Zheng, S.; Guo, C. Regional cultural inclusiveness and firm performance in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Qiu, J. Financial Development, Bank Discrimination and Trade Credit. J. Bank. Financ. 2007, 31, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.A.; Rajan, R.G. Trade Credit: Theories and Evidence. Rev. Financ. Stud. 1997, 10, 661–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biais, B.; Gollier, C. Trade Credit and Credit Rationing. Rev. Financ. Stud. 1997, 10, 903–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C. Trade Credit and Stock Liquidity. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 62, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, M.; Burkart, M.; Ellingsen, T. What You Sell Is What You Lend? Explaining Trade Credit Contracts. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2011, 24, 1261–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, D.; Klapper, L.F. Bargaining Power and Trade Credit. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 41, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chod, J.; Lyandres, E.; Yang, S.A. Trade Credit and Supplier Competition. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, X. Understanding the relationship between coopetition and startups’ resilience: The role of entrepreneurial ecosystem and dynamic exchange capability. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2025, 40, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Pan, Y.; Tian, G.G.; Zhang, P. CEOs’ hometown connections and access to trade credit: Evidence from China. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 62, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Chen, S.X.; Lee, E. Does Business Strategy Influence Interfirm Financing? Evidence from Trade Credit. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jory, S.R.; Khieu, H.D.; Ngo, T.N.; Phan, H.V. The Influence of Economic Policy Uncertainty on Corporate Trade Credit and Firm Value. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 64, 101671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.A.; Foley, C.F.; Hines, J.R. Trade Credit and Taxes. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2016, 98, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Xia, H.; Liu, Z. ESG Rating Divergence and Audit Fees: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lei, X.; Yu, J. ESG Rating Divergence and Corporate Green Innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 2911–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Wang, S.; Lin, Y.-E. ESG, ESG rating divergence and earnings management: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3328–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.; Pindado, J. Trade Credit During a Financial Crisis: A Panel Data Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadelis, S. What’s in a Name? Reputation as a Tradeable Asset. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerd, M.V.; Aerts, W. Does Media Reputation Affect Properties of Accounts Payable? Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Volchkova, N.; Zingales, L. The Corporate Governance Role of the Media: Evidence from Russia. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1093–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, M.D.; Wang, X.; Wei, S.J.; Zhang, J.R. Does Voluntary ESG Reporting Resolve Disagreement among ESG Rating Agencies? Eur. Account. Rev. 2024, 33, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Clarke, J.; Lee, S.; Ornthanalai, C. Are Analysts’ Recommendations Informative? Intraday Evidence on the Impact of Time Stamp Delays. J. Financ. 2014, 69, 645–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Lin, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, N.; Xiong, P.; Li, H. Cultural inclusion and corporate sustainability: Evidence from food culture and corporate total factor productivity in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, D.; Lee, H.S.; Neamtiu, M. The Impact of Operating Leases on Firm Financial and Operating Risk. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2011, 26, 151–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Morse, A.; Zingales, L. Who Blows the Whistle on Corporate Fraud. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 2213–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, M.; Ellingsen, T. In-Kind Finance: A Theory of Trade Credit. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, H. Does Familiarity Foster Innovation? The Impact of Alliance Partner Repeatedness on Break Through Innovations. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, G.; Preghenella, N.; De Toni, A.F.; Battistella, C. Stakeholder engagement in business models for sustainability: The stakeholder value flow model for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Dong, M.; Wang, H. ESG rating disagreement and stock returns: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 103043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).