Abstract

This research aims to evaluate and highlight the potential mesostructured architecture of established behaviours and operational practices based on the working model change imposed by the pandemic emergency in the public sector. After the intervention of an exogenous shock, the readiness, perceived usefulness and ease-of-use of technologies made the Technology Acceptance Model [TAM] verifiable. Concurrently, it is also possible to verify the Theory of Planned Behaviour [TPB] in the motivation and intention to change employees’ working habits under the lens of complexity and urgency, involving a From Knowledge To Knowledge Strategy [FKTKS]. The research protocol encompasses semi-structured interviews with public managers in Italy, alongside a perceptual and sentiment trend analysis of 70 public employees [35 females and 35 males] regarding their sentiments on digital transition and smart/hybrid working habits before, during, and after the pandemic. In the public sector, change is perceived as a shock-generative tension. In this way, the research aims to answer the genderised issue related to the perception and the persistence of using digital tools in the workplace during the post-urgency period as a regular habit based on perceived usefulness and ease-of-use. The study highlights a gender-specific trend in the use of the smart/hybrid working model after the health emergency. This propensity may also be attributable to the gender traits defined by Hofstede, within whose paradigm the interpretative dynamic provided is embedded. The during-COVID-19 acceptance and usage behaviours define an element related to masculinity because of its urgency and pressing deadlines. In contrast, endurance connects to femininity, emphasising resilience and long-term goals. This approach prioritises resilience and comprehensive well-being, focusing on achieving a good work–life balance [WLB] rather than just addressing immediate issues.

1. Introduction

The emergence related to the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly changed people’s work activities and social lives, expanding the possibility of replacing traditional forms of work with more innovative ways of working linked to technological tools [1,2].

New technologies have been crucial during the pandemic, accelerating the ongoing trend towards developing smart working in organisations [3,4,5]. Smart working differs from traditional ways of working in the way it is carried out, which is not constrained by defined time and space limits in the performance of tasks assigned to employees [6,7].

Over the last few decades, the topic of new ways of working that have arisen through new technologies has become central to the organisational debate [8]. These new forms of work should be considered in the context of deep societal transformations in which technologies have changed relationships and shared values. According to Jackson [9], these transformations have led contemporary society towards what can be defined as a distilled humanity in the new capitalism, in which the archaic values of society in terms of mutual social and economic equilibrium are destroyed [10]. In this context of profound change, the new technologies change the relationship between man and organisation on a double level: a broader one that concerns the man–machine–society relationship, and a second level in which people’s work is involved in the man–organisation and human–machine–society relationships [11].

One of the first new ways of working that has spread, linked to the use of technology, is teleworking. Teleworking represents a technology-supported work organisation that provides access to work from home. Teleworking has also been renamed “working from home”. These changes have a considerable impact on people’s lives, how they work, and how they are in society, with a significant impact on motivation and happiness [12]. Therefore, to build a society with the highest possible happiness and the lowest possible unhappiness, there can only be a new balance in society and organisations induced by leadership skills, especially in times of transition. According to different authors [13,14,15,16], leadership in times of organisational transition represents a key factor for overcoming a critical phase to activate change processes that take root in the medium-long term. This factor plays a central role in a period like the current one, in which there has been a rapid digital transition. This historical phase, following the pandemic, defined as the “new normal”, is based on some requirements that have produced emancipating and democratising effects in society: generalised access to knowledge with the advent of the internet and new enabling technologies. At the same time, however, following the COVID-19 pandemic, this digital transformation journey meant that individuals had to quickly accept new technologies to adapt to new ways of working.

For this reason, having significant leadership qualities in times of the “new normal” represents a more complex and challenging exercise than has recently been observed in economies characterised by structural optimism and constant underestimation of risks. Therefore, leading organisations in the current context are much more complicated than in the past. From this point of view, leadership assumes the role of service, aimed at the growth of people and organisations, promoting their skills and constructing relational methods capable of making people work with new technologies effectively and efficiently.

Starting from these assumptions, the author intends to focus on one of the new ways of working, smart working, considering different temporal phases of the investigation: [a] pre-pandemic, [b] during the pandemic, [c] after the pandemic.

In particular, the author focuses on the public sector, where the use of smart working before the pandemic was very marginal compared to face-to-face work [17,18]. This is useful from an academic perspective to identify the speed of acceptance of technology use and change within an organisation.

In this regard, through semi-structured interviews with five public managers and a perceptive sentiment and trend analysis of Italian local public administration employees, a strategy of acceptance of the digital transition and reduction in the reluctance to change for the public sector is proposed in terms of the application of the FKTKS [10,19], mainly in the presence [and after] of complexity factors, non-linearity, uncertainty and unpredictable exogenous shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The author, having conceived the role of digital technologies as a new institutional paradigm, in addition to what was explained above, proposes an emotional–empirical analysis of what is perceived and experienced by interviewees through a survey aimed at the three periods indicated above [before, during and after pandemic lockdown]. The aim is to characterise quali-quantitative elements of technological acceptance and transitional leadership.

One of the most relevant factors for smart working development in organisations has been identified in employees’ acceptance of this change concerning the work modalities. The other factor that has been identified is the willingness of employees to accept the intended use of new technologies [20,21] and the effective use of digital platforms [22]. In the public sector, while smart working has represented an opportunity to ensure the delivery of services to citizens [23,24], it has also opened different reflections on the positive impact and critical issues that this mode of remote working has on employees’ lives. Smart working represents a tool able to implement a new path of continuous reforms that have reshaped public administration in recent decades [4,25]. Despite the topic’s relevance, only some studies consider the factors behind public employees’ acceptance of smart working in the public sector. The public sector’s investigation is particularly focused because it was subject to specific smart/hybrid working requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this sense, different implementation dimensions—urgency, recognition of utility, and dynamic application—determine a scenario of fundamental importance for the proposed objectives and goals. The author proposes to analyse the critical perspective of the acceptance of change in the public sector due to smart working [intending it to digitalisation], particularly in the Italian context in terms of digital transition in the “disruptive technologies” era, as well as to consider the pervasiveness of technologies in contemporary society [26].

This paper aims to fill this gap by analysing the factors determining the acceptance of smart working change, using the semi-structured interviews based on the Technology Acceptance Model [TAM] [27,28,29,30,31], integrating this approach with the more general Theory of Planned Behaviour [TPB] [32,33,34] and intercepting the knowledge management view of the From Knowledge To Knowledge Strategy into complexity paradigms. The model used as a framework to develop a series of public managers’ interviews on smart working acceptance could be considered a vehicle for change in the public sector [35,36,37,38,39,40]. In addition, to verify the data at the conceptual level, a perceptive and sentiment trend analysis was developed based on [35 males and 35 females] public employees within the Italian public sector [Appendix B and Appendix C].

From a theoretical perspective, this paper aims to provide further insights into smart working as a tool for change in the public sector. Specifically, the author analyzes one of the new ways of working, smart working, from a critical perspective, also investigating the transversal aspects and a broad spectrum of theories related to the Acceptance Theory Model [28,29,30,31] theory of planned behaviour [32,33,34], knowledge management theory [41,42,43,44,45] and knowledge-based strategy [19,26], under the lens of resistance to change [46,47,48,49,50,51] related to complex environments [52] and psychological repercussions related to change [53,54]. From a managerial point of view, the research aims to support public administrations to increase the effective use of smart working [55], evaluating positive impacts in reducing levels of reticence favoured by external influencing factors such as COVID-19 and consequent urgency. The research aims to identify the structuring of established practices after the intervention of an exogenous shock [COVID-19] within the social and organisational community, specifically the public sector.

These practices are identified in the continued, even unnecessary, use of software for voice and video calls, teamwork, the persistence of smart work, regulatory and policy continuation of this practice and regulatory readjustments, not only for causes of strict urgency and necessity, but of structurally ordered situations in periods characterised by ever existing complexity, but linear [as the one after lockdown].

The full theoretical and practical investigation of the sensitive spectrum of language reveals its main findings, presenting the transition from a traditional to a smart/hybrid working paradigm as a result of the pandemic immediacy. This element may be appropriately associated with the domain of masculinity due to its characteristics of urgency, pressing deadlines and the viability of options. On the other hand, when it comes to endurance, it would be reasonable to link the continuous character, which is perceived as persistence and longevity, with the fundamental acts of resilience, which are motivated by femininity beyond the wake of urgency, taking a long-term, goal-oriented viewpoint. Instead of only tackling an urgent issue, this state was more appropriately focused on the pursuit of comprehensive well-being, also in terms of work–life balance [WLB]. In this sense, the article fits crosswise into the literature on digital transformation [56,57,58], acceptance theory [28,30,31], knowledge management [19,26,42,43,45] and resistance to change in the public sector [38,39,48,49,50,53,54,59] with the strategic perspective in overcoming organisational barriers and tensions [60].

The significance of the research derives from its results that suggest a pre-eminence of genderification in the phenomenon of the perdurance of smart/hybrid working related to the Italian public administration under the aegis of femininity. This is conceptually represented by the insights produced with the semi-structured interviews; on the other hand, the reflection of the survey-based empirical investigation at a perceptual level provides significant details on this evidence. The study, overall, in addition to identifying at a behavioural and habitual level a meaning of resilience for the purely feminine traits in the continuation of smart/hybrid working beyond the emergency, instead determines masculine traits of resistance and maintenance of the phenomenon investigated. The main implications are reflected in the possibility of delineating the boundaries of a growing phenomenon beyond the mere dimension of urgency, verifying the variables of the TAM, within a broader vision that determines new possibilities and scenarios in the framework of technological acceptance and digital transition in organisations, where the latter would be obtainable with fewer barriers through a participatory leadership capable of strategically sharing knowledge, triggering the compression of the Roger’s curve. In this theoretical dimension, the TPB also takes on value towards the structuring of alternative working methods, which would find confirmation in a renewed instrumentality towards the needs of WLB, considering the part-time formula as possibly surmountable, which in 2022 was estimated to be used by almost a third of employed women in Italy.

The paper is structured as follows: the first section introduces the preliminary aspects and reflects the entire structure of the research; the second analyzes the main background on the smart/hybrid working and technology acceptance in public sector, highlighting the principal dimensions; the third section outlines the theoretical frame, considering the genderised approach to technology acceptance and the “new normal” in working environments; the fourth section refers to the interpretative paradigm based on the specific theories [TPB, TAM and FKTKS] within the complexity frame; the fifth section explains the methodological steps and the gap evaluation; the sixth section shows the main findings at conceptual and empirical level; the seventh section critically discusses the findings and shows the theoretical and practical implications, limitations and further research avenues.

2. Background

2.1. Smart Working and Technological Acceptance in the Public Sector

In recent decades, numerous exogenous events have impacted territories and negatively affected individuals’ social lives. These types of exogenous events are identified as [a] caused by the hand of man [self-mitigating]; [b] caused by natural dimensions. As in the case of the pandemic emergency in February 2020, epidemics and pandemics should be considered an event belonging to the latest group of exogenous events. During the most critical phases of its spread, COVID-19 made it challenging to carry out activities at the office in person, paralysing society on an individual and organisational level. The pandemic emergency, as aforementioned, has changed several aspects of work organisation and individual work patterns. Different work activities have shifted remotely [61,62,63] and, also in terms of employment policies, the pandemic has favoured overcoming the performance of work carried out mainly in the presence, favouring work logics linked to “Bring Your Own Device” strategy [BYOD] [64,65,66,67]. Technology has played a crucial role in responding to the need to continue to operate and ensure the smooth running of work activities and services to users. Considering this innovation direction, it is possible to frame the phenomena of technological acceptance by employees [26,68]. In this scenario of change in working methods, a way of carrying out work that goes by the name of smart/hybrid working has found development and diffusion. According to different authors [69,70], smart working is a way of carrying out work performance based on a broad autonomy of choice concerning the times and places of carrying out the work activity to improve individual well-being and organisational efficiency. Usually, the diffusion and implementation of smart working take place around three key dimensions: [71] the technological factor; [32] the redesign of physical spaces and [33] a new vision of human resources in the organisation.

The first dimension of the analysis of smart/hybrid working is the effective use of digital technologies to support work activities. The development of new digital platforms and increasingly high-performance technologies has enabled employees to perform their work more effectively and efficiently. In the past, different authors have pointed out how new technologies, such as Bloom [72,73], can positively impact employees’ productivity and well-being. On the other hand, the spread of smart/hybrid working during the pandemic emergency also drew attention to other aspects, namely how technologies can increase the feeling of isolation and work overload, neutralising the benefits of smart/hybrid working.

Over the years, therefore, attempts have been made to structure different models to best address the application of smart working, implementing appropriate standards to achieve the benefits of this new way of working [74,75]. The second dimension of analysis related to smart working concerns workplace redesign. The shift to flexible organisational structures has changed the traditional concept of the workplace [76]. Smart working means redesigning physical spaces and reconfiguring their impact on employees and economic and environmental sustainability. The pandemic has represented an organisational disruption concerning people’s relationship with workplaces, with an impact on individual well-being and the meaningfulness of the concept of work itself [77]. Finally, smart working can only be realised if cultural and managerial approaches to human resources management are redefined. The role of management in this aspect is essential because smart working is only possible with a greater focus on the growth of professional figures of both specialised knowledge and skills and transversal and relational skills [78]. With the new technologies available, discussing the development and spread of smart/hybrid working is possible. The use of technology can be viewed from two different perspectives: on the one hand, it facilitates real-time interactions among employees, which impacts the meaningfulness of work.

On the other hand, using new technologies redefines processes by supporting networks and services that help people and companies increase efficiency and reduce the impact of presence in the workplace. As previously expressed, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the most significant emergency phenomena of the contemporary era, with a significant impact on health and social systems. What happened has opened a necessary reflection on new organisational and social models. Today, new knowledge and skills have been structured in the management of pandemics [79], but a renewed interest is due to the social paradigm for the future. In this sense, one of the most critical aspects concerns the working environment. During the pandemic, habits have changed. Under the pressing need to guarantee service or production, people have changed their psychological paradigms and habits [53] in a compressed time interval [26]. During the pandemic, organisations de-structured themselves, leaving room for non-physical work environments mediated by new technologies.

In this sense, the costs for building maintenance and transport have significantly reduced, but at the expense of the psychological dimensions linked to work–life balance and burnout [4]. Therefore, the thread could be clearer to understand how much agile or smart work tools should be used and how much this condition should instead be moderated in favour of socialisation or alternative working methods that favour an excellent work–life balance. Today, we are witnessing an evolution of human beings interacting with machines that goes beyond the Tayloristic model [80,81,82]. Precisely, this new revolution creates and generates knowledge and chaos at the same time. From this paradigm arise the idiosyncrasies in the markets and human relationships. The author tries to insert this contribution by filling a gap that highlights how the introduction of technological innovations [also understood as factors of external influence in the original architecture of the bureaucracy] can protect against other exogenous shocks in the public sector. Technological innovation guarantees the service only through a remodelled way of working.

In this sense, urgency [26] would reduce the existing barriers to innovation [83] and change [49,50,53,54,84] in the public sector, also reducing the risks of failures in the provision of services to citizens and counteracting other destabilising factors. According to different authors [85,86], an informed context should be considered the leading agent in reducing reluctance toward digital transformation processes and the use of new “disruptive” technologies, also due to the mediating role of transition leadership [13,14,15,16]. Moreover, compression of Rogers’ curve [87] can be observed in situations with a high emergence rate. This type of compression is to be attributed to extraordinary measures of need originating from exogenous factors such as pandemics or other natural or artificial disasters.

Based on these assumptions, the author aims to understand the following aspects:

- RQ1.—How does the genderificated perception of using digital tools in the workplace change from pre-pandemic to post-pandemic?

- RQ2.—Do digital tools continue to be used long after the critical phase of the COVID-19 health emergency by which type of employees in terms of gender?

- RQ3.—How can the FKTK approach structure smart working practices and processes of change in public administration?

2.2. Method, Research Design and Gap Evaluation

In the Italian context, smart/hybrid working has affected many employees. In detail, in the public sector, in 2021, 27% of employees were in smart working modality. The analysis relating to the Italian public context is fascinating due to the changes recorded between the previous phase and after the pandemic. According to the ISTAT Report of Public Institutions [2021], only 3.6% of Italian public administrations had structured smart working initiatives in their organisations. Instead, the number of public institutions that have adopted or will adopt structured smart working initiatives in the post-pandemic era is 20.3%. The interview protocol used by the author is closely related to the pandemic condition. In the first step, a questionnaire is submitted to five [N.5] public managers [Directors] of public administrations at the local level [Appendix B]. Then, these public managers will be interviewed. The semi-structured interview is based on a representative sample selection from different local public sector organisations in the Italian context. To answer the research questions that are the subject of the following work, the questions addressed to the public managers interviewed covered the following aspects.

On the one hand, to understand their ability to accept technologies, the focus was on: the sense of insecurity in using new applications; the sense of control through technologies; the feeling of frustration concerning learning new procedures; continuity in using new technologies after the emergency. The research protocol refers to semi-structured interviews based on public managers in the Italian context and in addition to that represented method, a perceptive and sentiment trend analysis on N.70 [35 females and 35 males] public employees about the perceived sentiments related to digital transition and perceptive sentiment trends on the use of smart/hybrid working habits before, during and post pandemic crisis. This kind of approach was developed to understand the pandemic’s impact on their ability to lead. The following aspects were considered: the feeling of anxiety or frustration regarding the change and acceptance or reticence regarding the change taking place. Finally, an individual graphical representation was provided by personal representation of respondents related to emotional sentiments toward change, related to the periodisation structured in three phases [before the pandemic, during the lockdown, and after the lockdown]. This segmentation is favourable for investigating qualitative variables of perceptions, feelings of acceptance and reluctance, emotional outlook and emergence conditions related to a new work environment. To consider the gap evaluation, the author investigated three primary literary databases related to business and economics. The methodological steps for the gap evaluation are the following:

- Business Source Ultimate: [filters: article, academic journal, abstract, keywords, title].

The first-level benchmark used “Innovation acceptance,”: with 170 results; the second-level criterion used “public sector,”: with three results; the third-level criterion used “covid-19,”: with 0 results.

- 2.

- EconLit: [filters: article, academic journal, abstract, keywords, title].

The first-level criterion used “Innovation acceptance”: with 15 results; the second-level criterion used “public sector”: with one result; the third-level criterion used “covid-19”: with 0 results.

- 3.

- Scopus: [filters: business, management, accounting, article, academic journal, abstract, keywords, title].

The first level criterion used “Innovation acceptance”: 1221 results; the second level criterion used “public sector”: 232 results; the third level criterion used “covid-19”: 20 results.

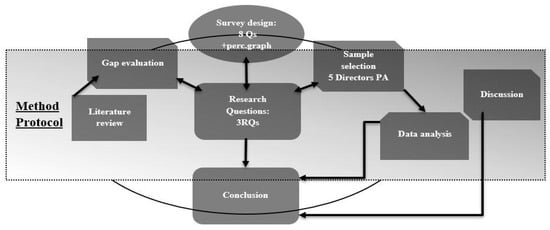

In the Scopus database, it would be possible to find 20 contributions [accessed 26 November 2022] referring to the criteria used for the research, observing that the ones found in the EconLit and BSU databases are involved in the Scopus list [Appendix A]. The voluntariness and non-mandatory environment, already reproduced by Venkatesh and Davis [29] in testing the Technology Acceptance Model, characterise the COVID-19 pandemic [2019–2020]. An expression of such transparency is the interview design structured on eight questions and a dynamic graph of individual perception [Appendix B emotional graph]. Therefore, at the protocol level, the author’s basic steps are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research protocol. Source: Author elaboration.

3. Theoretical and Research Contextualisation Paradigm: Genderising Technology Acceptance and the “New Normal” in Organisational Working Environment

Just as yesterday, the telephone and the internet promoted mediated connections between people; today, the Internet of Things and robotics produce connections between man and machine [11]. The COVID-19 pandemic and prolonged stay at home as an exogenous shock [88,89,90] has made this connection evident [91,92,93]. Therefore, it is necessary to identify and research from this perspective, especially with the intention of improving citizen services in terms of efficiency and effectiveness of administrative action. Starting from this dimension, the author aims to specify how an exogenous shock, such as the pandemic, can bring benefits through another exogenous shock of introducing innovations, not gradually driving the transition [26] but making a necessity a knowledge-mediated solution [19,94].

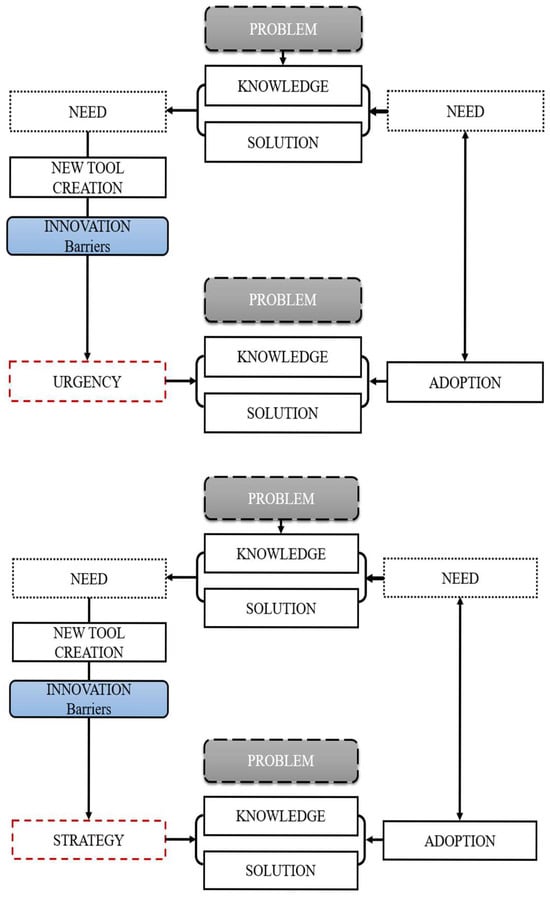

In literature, efforts have been made by Hess et al. [95] to structure a framework for digital transformation related to the smart working of the distinctive aspects of the public sector. They should have addressed the additional and crucial dimension of knowledge [96,97], concentrating the conceptualisation on the management perspective, leaving the bottom-up view neglected. For what concerns these aspects, Clegg [98] affirms that a gap and an oversight in the involvement of employees in the digital transformation process would be one of the leading causes of failure in innovation acceptance [99]. So, given the discrepancy found in the literature by secondary sources, the author tries to fill this gap involving knowledge as a crucial dimension in digital transformation processes by a strategic view based on it [from knowledge to knowledge—FKTK—Figure 2].

Figure 2.

From Knowledge to Knowledge Strategy Interpretative Model of COVID-19 reality. Source: adapted from [26].

In addition to the dimension aforementioned, the literary production, at the scientific and academic level, seems lacking in terms of contributions aimed at the public sector. In this sense, the originality of the work proposed by the author can be found precisely in the research protocol, which not only identifies and attempts to fill gaps in the literature but also provides valuable elements from the field directly from the individuals subjected to and affected by the change, providing [in three crucial periods of the pre-during-post pandemic] an emotional–perceptional analysis [100,101] of the same in terms of acceptance of digital technology and organisational change, as well as of the styles and modes of working operation. In the social and organisational community, specifically the public sector, change is perceived as a shock, generative of tensions.

In this way, the research aims to answer the question related to the perception and the persistence of using digital tools, permitting to work abroad in the workplace during the post-urgency period as a regular habit based on perceived usefulness and ease of use. In addition, it investigates how the FKTK approach can structure operational change in working practices for the public sector, guaranteeing the sustainability of the process through transitional leadership and avoiding toxic organisations, putting the person at the center.

The study intends to provide helpful information on how a new form of work, such as smart/hybrid working, together with the digitisation process, thanks to uncontrollable exogenous factors and the need dictated by urgency, have made it possible to break down the reluctance to change in the public sector, structuring habits based on the perception of lasting utility even beyond the emergency. In this regard, properly basing on the persona at the centre view, the author functionally uses the traits of masculinity and femininity proposed by Hofstede [102,103] and Hofstede and Minkov [104,105]. In this way, it would be possible to consider the already well-established dynamics of long-term and short-term orientation, attributable to the masculine and feminine traits, with the objective of determining whether they are representable with persistence or resilience in the persistence of the use of smart/hybrid working practices even beyond the pandemic emergency. In this regard, it would also be possible to classify the attributes of behavioural durability in working practice within the gender frame.

The Merriem-Webster dictionary provides four definitions of persistence, in its verbal meaning of persisting. The same dictionary provides two definitions of resilience. The definitions of persistence would be reflected in configurations of masculinity, while those of resilience would be reflected in configurations of femininity. Therefore, in light of the interviews used to define the operational context and the verification of the TAM and TPB, perceptive dynamics on the perpetration of smart/hybrid work practices would focus on: Work efficiency, Necessity, Improved quality/tasks, Improved communication/interpersonal interaction, Greater resolution, Better information exchange. These concepts would be closely connected with the masculine vision proposed by Hofstede [103]: “Men are supposed to be assertive, tough and focused on material success; women are supposed to be more modest, tender and concerned with the quality of life”.

In this sense, masculinity is seen to be the trait that emphasises ambition, acquisition of wealth; femininity is seen to be the trait that stresses caring and nurturing behaviours. From a hermeneutic point of view and in relation to the social norms that move masculinity and femininity traits, it is possible to find, respectively, [i] masculine traits characterised by ego-orientation, money and things importance, living in order to work; [ii] feminine traits characterised by relationship orientation, quality of life and people importance, working in order to live. In addition to what is explained, the long-short term dynamic is to be considered to underline the virtues of certain traits over others, valuing persistence and resilience as the main contribution to the choice of durability of smart/hybrid work practices beyond the emergency. According to Hofstede and Minkov [104], who quote Confucius, long-term orientation [LTO] also influences how a civilisation impacts the environment. Therefore, people’s contribution and long-term investment are mostly determined by the virtue of patience.

According to Hofstede’s view, feminine qualities include caring for others, having a decent quality of life and nurturing relationships, while masculine attributes include aggressiveness, competitiveness, power and material achievement. By highlighting the values of perseverance, saving and thrift, this LTO dimension examines how much people are ready to forgo immediate profits in favour of long-term benefits. On the other extreme of the spectrum is sacrificing future benefits in favour of short-term gains in the past or present, with a focus on instant satisfaction and speedy outcomes. Since current institutional arrangements follow a certain trajectory, altering them is expensive. In this way, maintaining the status quo, balancing unalterable staticity and stability, is preferred over change. This resistance is extremely visible in the public sector [84,106]. According to what was aforementioned, such systems seem to be resistant to change, preferring to be persistent rather than resilient.

4. Interpretative Paradigm: TAM, TPB and FKTKS: A Complexity and Knowledge Theory Perspective

Today, the Internet of Things and robotics connect humans and machines [11]. The COVID-19 pandemic and prolonged stay-at-home as an exogenous shock [88,89,90] have made this connection evident [91,92,93]. From this perspective, it is crucial to understand where the human boundary between connection and dispersal begins. It is necessary to significantly identify and research this perspective to improve citizen services in terms of efficiency and effectiveness of administrative action. This dimension moves the author, who aims to specify how an exogenous shock [and exogenous shocks] such as the pandemic can bring benefits through another exogenous shock of introducing innovations not gradually driving the transition [26], but making a necessity a knowledge-mediated solution [19,94]. In literature, ref. [95] have made efforts to structure a framework for digital transformation related to the smart working of the distinctive aspects of the public sector. They should have addressed the additional and crucial dimension of knowledge [96,97], concentrating the conceptualisation on the management perspective, leaving neglected the bottom-up view. As concerns these aspects, Clegg [98] affirms that a gap and an oversight in the involvement of employees in the digital transformation process would be one of the leading causes of failure in innovation acceptance [99]. So, given the discrepancy found in the literature by secondary sources, the author tries to fill this gap involving knowledge as a crucial dimension in digital transformation processes by a strategic view based on it [FKTK]. In addition to the dimension mentioned earlier, literary production, at a scientific and academic level, seems lacking in terms of contributions aimed at the public sector.

The originality of the work proposed can be found precisely in the research protocol, which not only identifies and attempts to fill gaps in the literature but also provides valuable elements from the field. The way traced moved the study and the hermeneutical view promoted by the author in aligning the research RQs, the design and protocol, the aims and the scope to the perspective shaped by Zimmerman et al. [107] on complexity science. However, what are we talking about? What is complexity science? Complexity science would be a field in which exogenous and endogenous factors are in a non-linear relation. That would create the base for the emergence of one or more phenomena, shaping borders of non-linear dynamics and triggering change. Under this lens, crucial and transversally crossed by the knowledge theory [28,29,30,31], innovation acceptance [19,26,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,48,49,50,53,54,59,60] and transitional leadership [13,14,15,16], the author moves the investigation in analysing a single case of social phenomenon involved into the public sector ambit: smart/hybrid working and its genderised durability in measures developed as structured operational habits and practices also after the emergency.

To perfectly understand what will be expressed at the end of the paragraph, it would be helpful to introduce the knowledge management paradigm [19,94,96]. It should be considered one of the most applied modes in structuring knowledge-oriented/based strategies [19]. Two dimensions of knowledge would be crucial in terms of the object of this study: [a] the explicit vertical knowledge aimed at creating knowledge by storing and memorising data [108,109] and [b] the implicit horizontal knowledge aimed at the creation of data and information sharing among humans [110,111].

Dewey [112], in his masterful work entitled “how we think”, states that no word is more frequent in everyday usage than thought and reflection, but there are profound differences between them. Similarly, the word knowledge, often misused but extremely frequent, identifies what humans store through the information processing system [113,114]. The Oxford Learners Dictionaries defines knowledge as “the information, understanding, and skills you gain through education or experience”. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, knowledge has a multifaceted meaning. On the one hand, “it is the condition of knowing something by familiarity acquired through experience or association”; on the other hand, it is regarded as the fact or condition of being “aware of something”. Considered that each innovation [the thing], and its following adoption [the process], emerges from knowledge, providing solutions for emerging issues. By contrast, each innovation creates barriers to its adoption [115,116] and Felten [117] assumes that new technologies must be accepted for a fruitful functioning. Social reality is moving in this direction. Private firms, the public sector and individuals are moving toward a “smartening revolution”. Encouraging this “smartening process” [118], knowledge-building [119] seems to be necessary to ensure actual knowledge creation in innovation acceptance social models [120]. In this sense, the accuracy with which directors and managers transfer knowledge [121] and the urgency variables affect employees [26] impact the need to provide a continuous production/service offering. Given these assumptions, the author inserts the FKTK strategy [19,26] starting from need–urgency and problem-solving approach [Figure 1]. In this sense, it would be possible to create an interpretative model under the pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic, evaluating deviances and short-term and long-term effects [in terms of perceptions] of transformed work environments. The reticence existing toward new tools, digitalisation and innovation more in general, implies a natural aversion to changing habits [47,49,53], especially in the public sector [84].

Information overload creates a non-informed context and given the knowledge-building environment, or self-information seeking on characteristics, potential and risks related to a new tool [71], in Kleijnen et al. [86] perspective, is one of the leading causes of failure in innovation acceptance. This lack of knowledge, in parallel with the information-acquisition desire for making conscious decisions [122], creates barriers to acceptance, ensuring a blocking condition to digital transformation processes. So, managerial implications should be considered under the lens of the Theory of Acceptance model, including urgency [took in place by COVID-19 contingency] and strategic orientation based on knowledge [FKTK], ability to time-compress the Rogers’ bell curve [19,26].

The transitional leadership contribution [13,14,16]; O’Brien [15] would reshape the connections existing among periods of linearity and non-linearity in terms of providing continuous production/service to the external, balancing internal frictions and tensions, guaranteeing the sustainability of the process [123], especially in the public sector, putting the person at the center [124] to avoid toxic organisations [125] by an ecological view of systems [126]. The FKTK strategy would allow directors and top managers in charge of an organisation to share timely knowledge [127] not only during linear periods but especially [through transactional leadership] during periods characterised by non-linearity, urgency and extreme pressure deriving from the critical issues or emergency [128]. In this way, it seems to find its foundation in what the author structured at the methodological level, passable by enlargement of the reference sample, comparison by different geographical areas and involvement from below of direct perception in transition and change, as well as the use of digital tools in the three moments [pre-during-post pandemic].

The contribution made by ICTs [129,130,131,132] and the smart working model [133,134,135] introducing software for cooperation [136,137] have been crucial during the COVID-19 lockdown measures. In that way, almost all public employees agreed to go digital in the wake of urgency and transitional leadership, which contributes most in times of crisis and emergency. Seemingly in everyday life, a symbiotic human–machine relationship seems to prevail [11]; this is not only in firms or offices, but in real everyday life, the digital dimension, mediated by smartphones, the internet, and devices, such as tablets and PCs, are making these tools an extension of human and an extension of reality in a digital dimension transformed by bits and pixels [48,138,139,140,141,142] that find repercussions and consequences in both places: those proper to the tangible physical dimension and those proper to the intangible digital dimension [143,144,145]. A question arises: what is the real driver of this change? Under what factors is this change happening fastest? Many would answer capital and money, but are we sure that is the correct answer?

Above all, need moves humans’ creativity [146,147,148] and flexibility, so under factors of complexity [107] and necessity [149], humans’ creativity can modulate and create optimal solutions of emerging issues [150,151,152,153]. Exogenous shocks force humans toward innovation and change of habits [53,85] due to urgency [26], as in the case of COVID-19 and smart/hybrid working, as well as the rapid acceptance of disruptive technologies. During the past three years, it has become possible to be affected by a sense of stringent uncertainty and urgency. Humans, moved by the need of the moment, started to operate differently, facing the pandemic situation. So, this is the basis of crisis management [154,155,156,157] to structure knowledge on the motives of the problem and, by the acquired knowledge, to invent powerful and disruptive solutions to the issues occurring, adding complexity and non-linearity to a complex system, as social life is.

As aforementioned, Zimmerman et al. [107] defined the science of complexity. In these terms, it would be necessary to consider a business perspective and a managerial one toward the complexity generated by COVID-19 in a stable organisation like those existing in the public sector [in other words, public administrations]. Considering the business perspective, the author proposes a dimension by which it would be possible to learn something from the complexity that emerged [158]. Opposite to the linear and flat dimension of social and socially organised life, there is the complexity view that observes, studies and analyses the rare characteristics of linearity in social life, considering it as a complex system constantly changing and composed by several interconnected, diverse and adaptive agents [159].

Agents as individuals are also considered in their social-organised way in terms of adaptive organisations, in which a transitional leadership [13,14,15,16] able to shape organisations as adaptive [160,161,162] would be necessary. In this sense, the predictable perspective of a simple linear reality view appears in contrast to the dynamic system perspective that is unpredictable [163,164], demonstrating non-linear patterns [intending exogenous and endogenous shocks or tensions]. In the case of the object of the analysis, leaders, managers, policymakers, academics and practitioners in health care [e.g., pandemic situation] should be interested in complexity management and the complexity approach to the emerging topics. So, the science of complexity suggests alternative ways to intervene [165] by transitional leadership and change management under an urgency perspective.

“The greatest constant of modern times is change” [166]. This change would derive from endogenous tensions, exogenous shocks, in other words, from the different agents interacting and linked to the system. The system, intended as a sum of individuals, natural dimensions and things social-organised or merely interrelated, generates complexity paradigms. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread was unpredictable, other disasters are predictable, but not entirely or surely. In this sense, the complexity paradigm creates new issues and problems that arise, involving effects unrelated to past actions. In this sense, actions implemented in attempting to solve crucial issues tend to fail, generating other problems or burdening the existing ones. The complexity dimension needs systems thinkers to face emerging and unpredictable complexity, moving action and reactions to shocks, practical, timely, efficient and effective, based on knowledge [19,26]. Related to the unpredictable complexity, the author refers to the original theoretical view, one of the most used in evaluating behavioural directions in the business sector. This theoretical frame, also integrated by FKTK strategic view [Figure 1] and TAM [Figure 2], can define and shape the way in which humans [by social factors, psychological elements and individual qualities] consider choices and decisions in their lives [167]. Several psychological structures [e.g., motivation, interests, attitudes, cognitive elements, mindsets, lifestyles] [168] trace directions of decision-making processes by humans’ information processing [114], also considering external influencing factors [169]. In this way, the integration of the different theories and paradigms would demonstrate once again that urgency is a determining factor in compressing the time of acceptance related to organisational change [49,68,87] and technological tools [170] [e.g., a new way of work], also modifying habits able to persist after the emergency. This is possible for two reasons: the technological dimension was pervasive in social life and ready to be broadly applicable at work. In this sense, perceived usefulness and ease of use would be verified [TAM-validated variables]. In this direction, the media and urgency influence, mixed with the managerial perspective and individual information-seeking ability to create knowledge, favoured the knowledge building [self-induced, internally induced, or externally induced], validating the aims of the FKTK strategy. Also, the Planned Behaviour Theory [TPB] [32,33].

It would be verifiable, as the theory predicts that three fundamental psychological factors [e.g., attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control], together with interagency, can shape humans’ behavioural intentions. In this sense, inherent in the urgency depicted by the COVID-19 spread, the intention/motivation [171] to face the emergency moved the subjective norms and individual control based on the personal/collective readiness to use technologies [attitude] toward the behavioural acceptance of change in working habits in a socially organised and generalised manner.

The scientific literature on digital transformation demonstrates positive repercussions for the smart/hybrid working mode. That would be accurate, observing periods characterised by linearity in general complexity. ICTs and the Smart working model show positive consequences on employees’ work–life balance [72,73]. However, is this also valid in periods of non-linearity? Probably not. When smart working is imposed, isolation and overworking could reduce its positive influence [75].

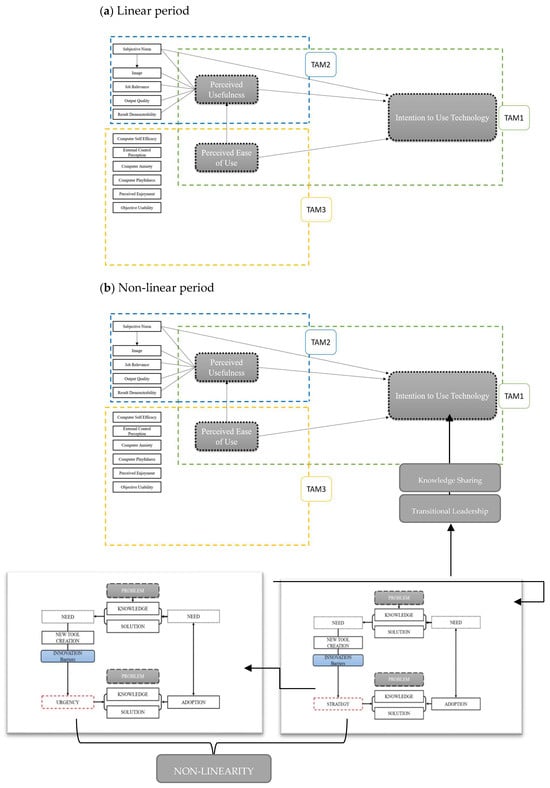

For this reason, not only the knowledge of the digital tool to be used must be transferred by top management and shared with subordinates on time, but not only the urgency and need must be perceived, but also the perceived ease of use and usefulness comes into play along with personal attitudes, thus complementing the model of the Theory of Acceptance [TAM] [28,29,30,172] and Theory of Diffusion of Innovations [DIT] proposed by Rogers [173], mediated by a knowledge strategy [FKTK] and by a transitional leadership during non-linear periods [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

(a) Linear period Reshaped (b) Non-linear period Reshaped TAM by Transitional Leadership, FKTKS, Urgency and Non-Linearity. Source: Adapted from [174].

Figure 3 represents the system of TAM during non-linear periods featured by urgency, pushed by a knowledge strategy [FKTK] and supported by a transitional leadership, creating an adaptive organisation founded on individuals’ timely adaptation compressed [159,160,161,162].

5. Findings

Concerning unpredictable phenomena, such as the pandemic emergency, the author, integrating the strategic vision of the TPB, and TAM under the lens of complexity dimensions and knowledge theory paradigms integrated into the FKTK strategical models [Figure 1 and Figure 2], plan to show how the topic of urgency can be a determining factor in compressing the acceptance times linked to the use of technological tools and methods of carrying out work such as smart/hybrid working, modifying habits capable of continuing even after the emergency and allowing the development of phenomena of organisational change. In this sense, the author involves perceptions related to the use of digital tools within the working environment, assuming [by TPB and TAM] a tendency inversion [from lower to higher perceived usefulness and ease of use by mature experience and knowledge transfer vehiculated by transitional leadership].

The author also investigates the use of digital tools and new working styles after the crucial lockdown [due to COVID-19 spread], expecting a persistence originated by the previously analysed variables, especially considering the level of personal loss, abandonment and frustration sentiments. The main theoretical result emerges in terms of genderification of habits and traits toward the persistence or resilience way to approach the “new normal” in smart/hybrid working models [175]. According to that, free from the gender identification of the respondents [at this initial conceptual stage], which could have influenced the coding of masculinity and femininity in the persistence/resilience behaviour, the results emerged from the semi-structured interviews are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genderisation of persistence/resilience behaviours from interviews.

The answers, provided without taking into account the gender of the respondents, to avoid influence in the analysis, determine a scenario, although exploratory, of behavioural configuration tending towards resilience, compared to that of persistence. This configuration, in the analytical attribution of genderificated connotations, focuses attention on the female dynamics compared to the male ones. The phenomenon, as described in Table 1, would decree a purely female dimension, at least at a conceptual level.

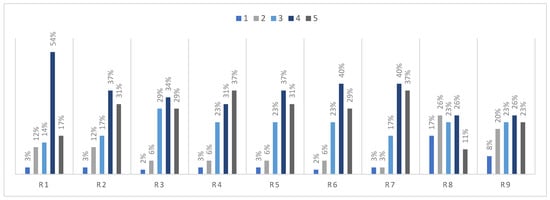

To confirm or refute what was highlighted at a conceptual level, the study provides more specific empirical details regarding the analysis of the responses of the subjects involved in the survey with nine statements to a key question [what has the organisational change generated in me in the transition to digital and smart working during the lockdown period?] to be answered with a five-year Likert agreement scale. The size of the sample is determined by an equal gender predisposition [35 males and 35 females], belonging to the sphere of work attribution of the public sector. As regards the male sphere of the subjects involved, the sample reflects an age equal to the following ranges: 18–29 years old [14%]; 30–44 years old [57%]; 45–64 years old [29%]. The roles covered are configured as follows: Head [6%]; Executive [71%]; Manager [17%]; Organisational position [6%]. The propensity to use technology is medium [74%]. As regards the female sphere of the subjects involved, the sample reflects an age equal to the following ranges: 18–29 years old [9%]; 30–44 years old [57%]; 45–64 years old [34%]. The roles covered are configured as follows: Head [3%]; Executive [63%]; Manager [23%]; Organisational position [11%]. The propensity to use technology is medium [74%]. The representation of the two samples converges in a decisive balance of fairness. This other questionnaire-based perceptive analysis and the further sentiment trend analysis provided on 70 participants [35 males and 35 female public employees] demonstrate in the following results what has already been expressed at a conceptual level. In more detail, as shown in Figure 4, the male sample refers to the first answer [R1] 54% [4 Likert agreement] and 17% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt anxious about change. To the answer [R2], 37% [4 Likert agreement] and 31% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt a sense of insecurity about using new applications. To the answer [R3] 34% [4 Likert agreement] and 29% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt a sense of control through the use of the PC for work. To the answer [R4] 31% [4 Likert agreement] and 37% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt a sense of reticence about change and new things. In response [R5], 37% [4 Likert agreement] and 31% [5 Likert agreement] stated that they felt frustrated with the change. In response [R6], 40% [4 Likert agreement] and 29% [5 Likert agreement] stated that they felt frustrated with having to learn new procedures. In response [R7], 40% [4 Likert agreement] and 37% [5 Likert agreement] stated that they felt lost and abandoned by managers—leaders. In response [R8], 26% [4 Likert agreement] and 11% [5 Likert agreement] stated that they implemented continuity in the use of digital tools even in the post-pandemic period. In response, [R9] 26% [4 Likert agreement] and 23% [5 Likert agreement] stated that they felt the transfer of knowledge by leaders was fundamental to breaking down barriers of reticence to the acceptance of new technologies and digital working methods.

Figure 4.

Males’ questionnaire answers. Source: Author elaboration.

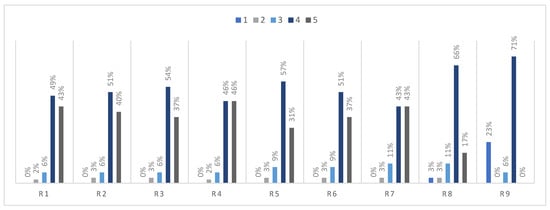

In more detail, as shown in Figure 5, the female sample refers to the first answer [R1] 49% [4 Likert agreement] and 43% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt anxious about the change. To the answer [R2] 51% [4 Likert agreement] and 40% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt a sense of insecurity about using new applications. To the answer [R3] 54% [4 Likert agreement] and 37% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt a sense of control through the use of the PC for work. To the answer [R4] 46% [4 Likert agreement] and 46% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt a sense of reticence about change and the new. To the answer [R5] 57% [4 Likert agreement] and 31% [5 Likert agreement] state that they felt a sense of frustration about the change. In response [R6], 51% [4 Likert agreement] and 37% [5 Likert agreement] stated that they felt frustrated in having to learn new procedures. In response [R7], 43% [4 Likert agreement] and 43% [5 Likert agreement] stated that they felt lost and abandoned by managers—leaders. In response [R8], 66% [4 Likert agreement] and 17% [5 Likert agreement] stated that they implemented continuity in the use of digital tools even in the post-pandemic period. In response [R9], 71% [4 Likert agreement] stated that they felt the transfer of knowledge by leaders was fundamental to breaking down barriers of reticence to accepting new technologies and ways of working in digital mode.

Figure 5.

Females’ questionnaire answers. Source: Author elaboration.

As regards the results emerging from the sentiment trend analysis, Table 2 provides the indications relating to the male sample and Table 3 those relating to the female sample. In this direction, it is possible to consider the general trend for each quadrant, based on the greater percentage of co-occurrence in the trend segment falling on each individual quadrant.

Table 2.

Males’ perceptive and sentiment trend analysis.

Table 3.

Females’ perceptive and sentiment trend analysis.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion on Emerging Results

Under the lens of exceptional technological evolution, involving Virtual Reality, Blockchain, Metaverse, Artificial Intelligence emergence and their repercussions on the whole society, invading and pervading the human sphere, this research aims to evaluate and highlight the potential mesostructured architecture of established behaviours and operational practices based on the working model change imposed by the pandemic emergency in the public sector. After the intervention of an exogenous shock [176], the readiness, perceived usefulness and ease of use of technologies made the TAM [172] verifiable. Simultaneously, it becomes feasible to scrutinise the Theory of Planned Behaviour [TPB] [32] regarding the motivation and intention to alter employees’ working practices through the lens of complexity and urgency. This underscores the contraction of Rogers’ bell curve [26,68], spurred by an individual quest for self-knowledge aimed at fostering understanding or a top-down knowledge management strategy to facilitate the shift through transitional leadership and a From Knowledge to Knowledge Strategy [FKTKS] towards a Value-Generative Society [26,177]. Recent years [2020–2022] have seen a significant social change influenced by a global pandemic. As already mentioned in the literature review, positive impacts have been associated with the application of smart/hybrid working during pre-non-emergency, emergency and post-emergency conditions. The interviews aim to highlight this trinomial perspective to understand the impacts of smart/hybrid working in non-emergency, emergency and post-emergency phases. From a conceptual point of view, the first analysis identifies important insights into the femininity of the resilience traits of smart/hybrid working, even beyond the emergency. The more typically feminine dimension of the phenomenon is decreed by the empirical analysis conducted with surveys on 70 public employees [35 males and 35 females]. In this direction, although the sensitivity to change and feelings of frustration are more detailed in the results that emerged for females, the dynamics of perception of continuity of use of the “new-normal” practice of smart/hybrid work seem to be phenomenologically more feminine than the slightly lower results reported by the male sample. In support of this perspective, the sentiment analysis of trends provides relevant indications by identifying a more or less similar starting point between males and females on the use [non-use] of smart/hybrid working before the COVID-19 pandemic, settling on a growing balance during the pandemic and lockdown. The substantial difference can be found above all in the post-pandemic and post-emergency period, which would see results more or less in balance with the previous period as regards the male sample. On the contrary, the female sample shows higher values of persistence of the “new normal” practice of smart-hybrid working. Therefore, if on the one hand the phenomenon is purely female in terms of resilience, while more substantially of resistance for males, the reason for the need, perception of usefulness and ease of use for female working dynamics to support an improved WLB is presumably clear, capable of overcoming the need for part-time contracts for example, demonstrating a conceptually feminine flexibility and resilience in adopting new approaches to change, despite greater sensitivity and greater exposure to feelings of frustration. Precisely in this context, the term resilience appears to be more appropriate than ever for the female condition expressed and the term resistance attributable to the behavioural dynamics decreed by the male sample. The role of management in organisations has become even more crucial in governing the development of smart/hybrid working. In this sense, the power of leadership and the speed of action have renewed the organisational hierarchy and leadership, especially the transitional leadership associated with adaptive organisations. The issue of leadership has been closely linked to employees’ ability to adapt to new technologies, which have been a relevant tool for the continuity of work performance and the spread of smart/hybrid working. This aspect has generated a necessary adaptation of employees to new technologies in order to deal with work performance effectively, as well as the necessary dissemination of knowledge practices for the understanding of their use, which would be able to break down levels of reticence and resistance to change driven towards collective knowledge and learning [178,179].

6.2. Theoretical Comparative View

From a theoretical standpoint, the important function that knowledge plays as a catalyst for change should be taken into consideration while designing the research’s architecture and methodology [180]. Urgency is the foundation for a quicker shift in behaviour, and the knowledge dimension begins with a need [149], which is thought to be a catalyst for the development of innovation toward new organisational solutions [53]. These days, technology is essential to the processes of knowledge and transformation. On the other hand, these solutions must cope with the inherent barriers people pose on an individual and socio-organisational level. In this sense, the “knowledge society” [181,182] is characterised by feelings of VUCA [Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity] [183,184], also by liquidity and discontinuity [185,186], which would create favourable elements for the adoption of alternative ways of working [187]. In this sense, the analysis carried out on the pandemic emergent, non-emergent phases aims to show aspects of individual and socio-organisational perspectives that would otherwise not have been investigated or observed with such accuracy [26]. A cyclical view of producing and reproducing innovative solutions to social problems. This creative extension [79; 80; 81] of human thinking as a rational decision-maker led to inventions and subsequently revolutionised them by industrial means, from the first to the current fifth revolution, always following the FKTK cyclicality previously expressed. In this process, barriers and reluctance to change in applying new tools are invariant. Under the lens of the 5.0 revolution and the condition of emergence affecting individual and socio-organisational life, interpreted as a new evolution of social life, as expressed by Gascò [188], the mainstream economy is based on and reinvigorated by using large amounts of information to create knowledge. However, friction and chaos are also caused by the overload of stored data and their free accessibility and availability [86]. In this respect, it is crucial to identify the critical actors of organisational change and digital transformation [189,190], considering the COVID-19 pandemic. In these terms, above all, the investigation in the public sector becomes interesting for the reasons declared above. Concerning the proposed main RQs, the analysis was conducted on three key moments to observe the change perceived individually and in an aggregate manner by individuals [managers/public administration officials] performing managerial functions on many subordinates. In this sense, the analysis’s importance [through semi-structured interviews] is evident, especially for the qualitative characteristics otherwise unattainable, in terms of results, by quantitative methods. The condition that the COVID-19 spread evidenced and structured should be intended as a privileged point, permitting observing a phenomenon directly from its emergence, without filters and mainly in the field. That, for scholars, academics, practitioners and researchers, permitted to investigate the change that occurred in lifestyle and expression in working styles through an a-posteriori perspective, also considering the previous perception, the concomitant [under the pressure of restrictive lockdown measures] and the aftermath related to the critical period object of the study. The study’s originality lies in integrating theoretical models of reference and in the perspectives identified by the determining contingent factors of the observable and scarcely reproducible complexity. The expected responses, considered by the author as the main findings related to the research questions, reflect two aspects. On the one hand, in terms of the perception of digital tools and the application of smart working as a “new normal” tool [191], an inverse trend, moving from a lack of application [which emerged from fears, prejudices, uncertainties, and a sense of uselessness] to widespread use, driven by a reversal of initial preconceptions. On the other hand, in terms of knowledge diffusion, a trend from considering digital tools and smart/hybrid working as a non-useful model to a relevant one. On this thin line of terminology, the entire study, conceptual and empirical, provides its main contributions, defining the translation from a traditional to a smart/hybrid work model as attributable to the immediacy of the urgency produced by the pandemic.

6.3. Implications

Precisely because of the characteristics of urgency, tight timeframes and resolvability of the option, this dimension would be properly attributable to the sphere of masculinity. On the contrary, in terms of longevity, it would be possible to ascribe the persistence, understood, however, as perseverance and durability, in the prodromal action of resilience, operated by traits of femininity in the phases following the urgency, with a long-term vision and orientation. This condition, more properly aimed at the pursuit of well-being, rather than the mere resolution of a short-term problem, represents the prospective action of the feminine approach that balances patience, perseverance, quality of life, relationships and work for life, which is reflected in the canons of the advantages of alternatives to the traditional working vision. Meanwhile, this logic of change would be reaffirmed by the cyclical nature of the institutionalisation–deinstitutionalisation process [49], capable of “breaking the chains” of the, albeit well-tested and traditional static models, towards resilient flexibility based on evolutions of previous social institutions. In this direction, the exogenous shock factor [urgency], in addition to the endogenous induced one [transitional leadership, knowledge management, perceived ease/utility of use], has led the author to consider persistence and perdurance of the new working model, even after the emergency. This also made it possible to investigate the role and instrumental functionality that the FKTK strategy covers in the digital transition of the public sector. In this sense, it is essential to verify that, overall, the sample seems to actually recognise a fundamental importance of leadership in knowledge transfer to break down barriers of reticence to change and digital transition [192]. This vision is clearly detectable, decreeing a structural scarcity of knowledge management and sharing settings, outlined by the phenomenon in the reference period for the public sector. In this regard, these results would support the thesis of a preference for an implementable FKTKS to favour the transition and acceptance of the digital transition, new ways of working, technology or in any case, a change in general.

6.4. Limitations

Limitations intrinsically attributable to this study would be found in the purely exploratory nature and in a limited sample interviewed. These are limitations that impact the reliability of the results and their generalisability, but which nevertheless provide important clues for subsequent investigations that are more demographic and oriented towards gender characteristics, which currently identify useful insights of informational and conceptual profile. Subsequent investigations can be structured on the identification of female WLB needs, where, before the COVID-19 pandemic and the persistence of smart/hybrid working, women in particular were forced to use a part-time work dynamic, which today instead find confirmation in a more egalitarian dimension and resilient flexibility of a behaviour of preference in the perceived usefulness of the formula.

6.5. Future Avenues

Prospects can be identified in the extension of the reference sample and the comparison between geographical areas of the same Country, identifying areas with high technological development and areas with low technological development, concerning the funds received concerning the digital transition at the European level. Further analysis can also be considered valid about other Countries with a comparative view, identifying best practices and replicable actions. A new avenue is thus determined for the managerial implications arising from this study, which would draw inspiration from a renewed FKTKS [26] to promote a conscious change, clearing the masculine anchoring of society, towards a sustainable, resilient and feminine-driven traits transitional leadership, capable of maintaining wellbeing over a long, perhaps even an indefinite period, making change an investment for the future. Here, the present research work provides key details of hermeneutic and conceptual interpretation, even if based on a limited empirical basis, on the perspective of genderification of working habits and on the persistence, resistance or resilience connected to the male and female cases of work-useful behaviour, in the possibilities of more equal life choices and in the possible flexibilisation of habits. Will COVID-19 and the pervasive use of technologies for work decree the deterministic end of part-time? New avenues of research in this direction need to be considered.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested directly from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Scopus Export Results [Gap Evaluation]

| Maduku, D.K.; Thusi, P. Understanding consumers’ mobile shopping continuance intention: New perspectives from South Africa. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103185. Bullini Orlandi, L.; Febo, V.; Perdichizzi, S. The role of religiosity in product and technology acceptance: Evidence from COVID-19 vaccines. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122032. Recuero-Virto, N.; Valilla-Arróspide, C. Forecasting the next revolution: Food technology’s impact on consumers’ acceptance and satisfaction. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 4339–4353. Cited two times. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2021-0803. Shahzad, A.; Zahrullail, N.; Akbar, A.; Mohelska, H.; Hussain, A. COVID-19’s Impact on Fintech Adoption: Behavioral Intention to Use the Financial Portal. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15100428. Kim, J.J.; Radic, A.; Chua, B.-L.; Koo, B.; Han, H. Digital currency and payment innovation in the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103314. Lee, S.; Seo, Y. Exploring how interest groups affect regulation and innovation based on the two-level games: The case of regulatory sandboxes in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121880. David, L.O.; Nwulu, N.I.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Adepoju, O.O. Integrating fourth industrial revolution [4IR] technologies into the water, energy & food nexus for sustainable security: A bibliometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132522. Kateb, S.; Ruehle, R.C.; Kroon, D.P.; van Burg, E.; Huber, M. Innovating under pressure: Adopting digital technologies in social care organizations during the COVID-19 crisis. Technovation 2022, 115, 102536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102536. Secinaro, S.; Dal Mas, F.; Massaro, M.; Calandra, D. Exploring agricultural entrepreneurship and new technologies: Academic and practitioners’ views. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2096–2113. Chou, S.-F.; Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Yu, T.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-T. Identifying the critical factors for sustainable marketing in the catering: The influence of big data applications, marketing innovation, and technology acceptance model factors. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.02.010. Peppel, M.; Ringbeck, J.; Spinler, S. How will last-mile delivery be shaped in 2040? A Delphi-based scenario study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 177, 121493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121493. Reichenbach, R.; Eberl, C.; Lindenmeier, J. DYNAMICS OF ATTRIBUTE-SPECIFIC CUSTOMER REQUIREMENTS IN INNOVATION PROCESSES: A PANEL ANALYSIS CONSIDERING KANO’S THEORY. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 26, 2250014. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919622500141. Jorgensen, J.J.; Zuiker, V.S.; Manikowske, L.; Lehew, M. Impact of Communication Technologies on Small Business Success. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2022, 32, 142–157. https://doi.org/10.53703/001c.36359. Mansoor, M.; Paul, J. Consumers’ choice behavior: An interactive effect of expected eudaimonic well-being and green altruism. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2876. Yaprak, Ü.; Kılıç, F.; Okumuş, A. Is the Covid-19 pandemic strong enough to change the online order delivery methods? Changes in the relationship between attitude and behavior towards order delivery by drone. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 169, 120829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120829. Martins, M.; Costa, M.; Gonçalves, M.; Duarte, S.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Knowledge creation on edible vaccines. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 18, 285–301. https://doi.org/10.34190/EJKM.18.3.2020. Roberts, R.; Flin, R.; Millar, D.; Corradi, L. Psychological factors influencing technology adoption: A case study from the oil and gas industry. Technovation 2021, 102, 102219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2020.102219. Guarcello, C.; Raupp, E. Pandemic and innovation in healthcare: The end-to-end innovation adoption model. BAR—Braz. Adm. Rev. 2021, 18, e210009. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-7692bar2021210009. Widianto, M.H. Analysis of pharmaceutical company websites using innovation diffusion theory and technology acceptance model. Advances in Science. Technol. Eng. Syst. 2021, 6, 464–471. Yan, L.-Y.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Loh, X.-M.; Hew, J.-J.; Ooi, K.-B. QR code and mobile payment: The disruptive forces in retail. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102300. Cited 62 times. |

| Source from: SCOPUS [accessed 26 November 2022]. |

Appendix B. Questionnaire Design

| Please answer the questionnaire being aware that the data collected will be considered anonymous and cannot be traced back to the individual. | |||||

| Gender: M F Age: 18–29 30–44 45–64 Position: Public Manager Employee Middle-Management, PO. Sono propenso all’uso di tecnologia nella mia vita quotidiana e lavorativa: Scarcely Medium High | |||||

| Answer the following question WHAT HAS THE ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE GENERATED IN ME IN THE TRANSITION TO DIGITAL AND SW DURING THE LOCKDOWN PERIOD: | Answers | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Scarcely | Not Much | Medium | Quite | High | |

| R1. SENSE OF ANXIETY |  |  |  |  |  |

| R2. SENSE OF INSECURITY WHEN USING NEW DIGITAL APPLICATIONS |  |  |  |  |  |

| R3. COMPUTER CONTROL SENSE |  |  |  |  |  |

| R4. SENSE OF RETICENCE TO CHANGE |  |  |  |  |  |

| R5. SENSE OF FRUSTRATION AT CHANGE |  |  |  |  |  |

| R6. SENSE OF FRUSTRATION IN LEARNING NEW PROCEDURES |  |  |  |  |  |

| R7. SENSE OF LOSS AND ABANDONMENT |  |  |  |  |  |

| R8. FEELING OF CONTINUITY IN THE USE OF DIGITAL TOOLS ALSO IN THE POST-PANDEMIC PERIOD |  |  |  |  |  |

| R9. KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER BY LEADERS HAS BEEN ESSENTIAL IN AVOIDING TECHNOLOGICAL ACCEPTANCE BARRIERS |  |  |  |  |  |

| Source: Author elaboration. | |||||

Appendix C. Emotional Analysis

Trend tracking through a graph of emotional perception from the pre-pandemic phase to the post-pandemic period.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | ||

| 1 |  + | |||||||

| 2 |  = | |||||||

| 3 |  − | |||||||

| Quadrant | Sentiment/ Phase | PRE-PANDEMIC PHASE | LOCKDOWN PHASE | POST-PANDEMIC PHASE | ||||

| Source: Author elaboration. | ||||||||

References

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, T.; Lei, S.; Haider, M.J.; Hussain, S.T. The impact of organizational justice on employee innovative work behavior: Mediating role of knowledge sharing. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, B.; Reynaud, E.; Osiurak, F.; Navarro, J. Acceptance and acceptability criteria: A literature review. Cogn. Technol. Work 2018, 20, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]