1. Introduction

In the 21st century, social innovation is fully recognized as a source of new, public-beneficial solutions that address societal challenges [

1]. The growing demand for SI (social innovation) literature has multiple causes. Firstly, it has been the criticism of dominant innovation models that do not link the emergence of new technologies with their societal impacts, leading to further shaping of social innovation as a construct [

2]. Secondly, policy makers are still more concerned with social innovation due to the inability of innovation systems to deliver solutions addressing key social challenges [

3]. The economies of Western countries in the 21st century suffer from deepening selected development problems including demographic changes and especially the aging of the population, an increase in environmental concerns, the failure of some policies to stimulate economic growth and innovative activity, and socio-cultural tensions [

4].

Thus, it can be stated that social innovations have been strongly linked with compensating for system failures [

5]. In a same way, SIs can compensate for market failures, as many social and environmental issues of today’s world cannot be resolved by market mechanisms in the context of neo-liberal policy, or they directly represent negative impacts of economic activity [

6]. The demand for a better conceptualization of SI arises also from the side of practitioners, as SIs have the ability to compensate for reductions in public spending [

2]. In this context, we are interested in whether SIs can fill the gaps that arise from the inability of commercial innovations to address the societal challenges caused by market failures and system failures [

7].

This empirical study focuses on the triangulation between civic engagement and the formation of active local communities, the creation of civic-led social innovations, and the commercialization of social-innovative solutions. The study addresses several research gaps, concerning a better understanding of the ways in which innovative products and services are created in community-led civil organizations [

8], a better understanding of the market potential of civic-led solutions [

6], patterns of demand for community-led innovative products and services [

2], and, in particular, a better understanding of the value and outcomes generated from the introduction of community-led innovative products and services [

9]. Through such a research framework, it would be possible to better discuss in what “mode” SIs are emerging in civic-led actors and how SIs can increase the degree of complexity [

10] of solving crucial societal problems of local or global significance [

11]. Therefore, the aim of the study is to evaluate the various modes in which social innovations (of products and services) can arise in the conditions of community-led grassroots initiatives, to compare the patterns of social and economic value creation through these innovations and the possibilities of their commercial exploitation. The research framework will be addressed more comprehensively in the following chapters.

3. Materials and Methods

Grassroots initiatives represent community-led (formal or informal), civic, or cross-sectoral organizations, which are most often institutionalized in the third sector, as is the case in Slovakia. Formal institutions (mostly NGOs) serves as a “shelter”, which opens up possibilities to carry out formal activities, enter into contractual relations, and integrate resources. Therefore, since grassroots communities establish formal institutions that take different legal forms, it is difficult to identify them in space and collect data about their activities. Our intention was to survey the entire population of grassroots initiatives in Slovakia that had established a formal institution anchored in the third sector. Among all 83,932 organizations falling under the third sector in Slovakia in 2021, we manually identified 462 initiatives that met the following criteria:

- ➢

Their declared activity is related to social, environmental, cultural, or economic problems within their locality, or in wider space;

- ➢

They are defined as community-led initiatives, or they clearly refer to the existence of their own community of supporters;

- ➢

They have the potential to be a source of social innovation.

The filtering of grassroots initiatives that met these criteria was performed manually. In this way, we filtered out a significant number of sports clubs, hunting associations, political organizations, etc., which did not meet our definitions of grassroots. In addition to this initial list, we wanted to expand the identified population to include grassroots initiatives that were not institutionalized in the third sector. For this purpose, snowball-sampling was used. Snowball-sampling is usually utilized when it is complicated to identify further objects within the population [

47]. Respondent grassroots initiatives identified, among their partners and social capital, other actors that could be the object of investigation. Using this approach, we expanded our sample up to the point where we assessed that the sample was saturated and that it was difficult to obtain additional information on other possible respondents [

48]. Our sample was expanded by another 40 grassroots initiatives anchored in other sectors.

Our primary data collection was based group guided interviews associated with filling out an extensive questionnaire, which served as a basis for data quantification. In total, between September 2021 and October 2022, data on 106 grassroots initiatives in Slovakia were obtained; for 89 of them, it was possible to conduct a mass guided interview (interviews with several representatives of the grassroots initiative at the same time) associated with filling out an extensive questionnaire. These interviews took place mainly online via Google Meet or Zoom services. Another 17 grassroots initiatives completed the questionnaire and provided us with comments within the open questions section. Overall, we achieved a questionnaire return rate of 21.11%. The questionnaire was pre-tested using 15 grassroots initiatives, mostly located within Nitra, Slovakia. The first 15 respondent grassroots initiatives, in addition to filling out a questionnaire, participated in a series of focus groups, the aim of which was to clarify the perception of selected definitions (e.g., social innovation) and to obtain a preliminary overview of the activities and patterns of value created in the case of community-led grassroots.

Concerning the methods, our analytical framework uses grounded-theory-based comparative analysis, which aims to build hypotheses in the context of the research objectives without specific expectations of what will be uncovered [

49]. Our analytical framework, therefore, utilizes content analysis [

50] and coding [

51], while part of the results are presented via basic quantitative descriptive approaches. Within grounded theory research, it is first crucial to define key concepts or categories. In our case, social innovation represents a core category, while “pure”, “bi-focal”, and “market-exposed” SI represent categories within typology according to the level of market exposure. For the purpose of this study, we define social innovation through a broader definition by the Ministry of Investments, Regional Development and Informatization of the Slovak Republic, provided in

Section 2.1. Only three key codes for defined social innovations emerged from the definition:

- ▪

Provably contribute to the fulfilment of social needs;

- ▪

Have the potential to support qualitative change in the life of society;

- ▪

Follow the principles of sustainable and inclusive action.

The study will proceed from the understanding of the basic attributes and dimensions of “pure”, “bi-focal”, and “market-exposed” SIs to the evaluation of their social and economic outcomes, as the evaluation of patterns of value creation can be expected to be deeply affected by nature of social innovation. Concerning the comparative framework used for the investigation of these three groups of SIs, we followed a standard grounded theory methodology based on coding [

51]. This process of extracting the (1) open codes, (2) axial codes, and (3) selective codes followed by comparative interpretation was utilized to define parameters of “pure”, “bi-focal”, and “market-exposed” SIs (Q1) and was also used for comparison of the individual SIs in terms of social and economic outcomes (Q3). Interpretations of the results were strengthened by adopting the storytelling approach. The description of the value generated by SIs in the sample is based on following comparative framework [

38]:

- ▪

Comparison of social and societal outcomes;

- ▪

Comparison of economic outcomes;

- ▪

Evaluation of target groups;

- ▪

Evaluation how SIs generate shifts in values in society;

- ▪

Evaluation of enhancing the competences and capacities of target groups.

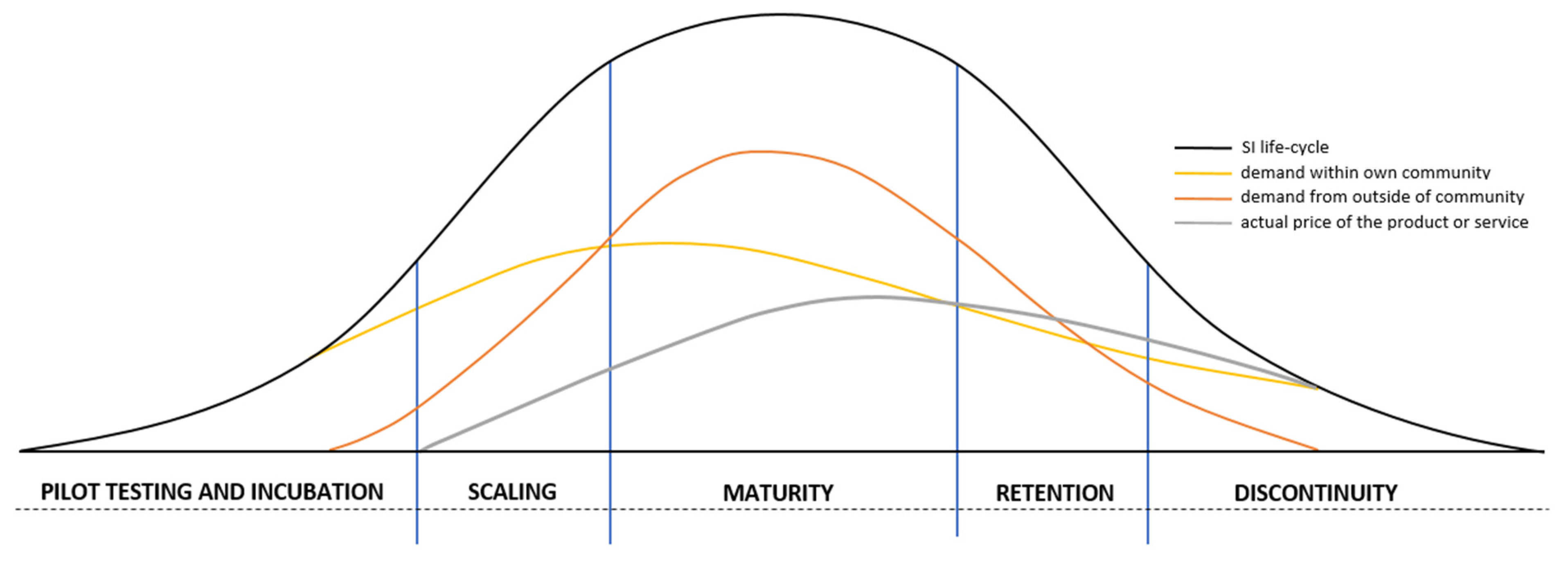

In order to demonstrate the potential for the conceptualization of demand for the community-led SIs (Q2), we adopted a visualization approach based on the standard product life-cycle utilized in the economy, as well as the majority of other scientific fields.

4. Results

4.1. Conceptual Definition of SI and Descriptive Characteristics of Identified Social Innovations

As already mentioned in the previous chapter, our sample represents 106 grassroots initiatives established in the Slovak Republic. Among the actors in this sample, we will further work with those who have been identified as social innovators. As part of the guided interviews, we managed to identify 63 specific examples of social innovation in 46 out of 106 grassroots communities in the sample. At this point, it is important to clarify which criteria the products and services of these grassroots initiatives were used to identify potential social innovations in the sense of innovative products and services. Which products and services could be considered as social innovations was decided on the basis of three principles:

The actor identifies the solution as a social innovation;

Within the framework of the guided interview with the given innovator, the dimensions of the product or service were consistent with the definition of social innovation used by the Government of the Slovak Republic; and applied in national strategies; to check for proper understanding of SI;

The actor declares and reports these social innovations as part of reporting to central institutions and the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic.

For this study, we adopted a broader definition of social innovation (provided in

Section 2.1.), which follows from the national definition. We were interested in applying this definition when interpreting the country-specific conditions for the emergence of SI. Also, considering that this definition was developed mainly for the purpose of defining social innovation in conditions of the third-sector actors, it suits our interests well. We provide an overview of the identified social innovations in the form of novel, publicly beneficial products and services, as in

Table S1.

From the content analysis of the guided interviews, several new facts emerged about the creation of SI in the conditions of community-led initiatives. However, we were missing some information required for these descriptions in seven of the respondent grassroots; thus, only data from interviews with 39 out of 46 innovators are available. The methods used for the initial development of new products and services were significantly differentiated. Up to five innovators stated that the initial conceptualization of their product/service represented an individual initiative of one or only a few managers or activists within the community. Otherwise, more than half of the identified social innovations can be considered as a reaction to existing demand—especially at the level of the entire own community, the local community (residents of the given location), or even in the case of 18% of the innovators who responded, in a wider space. However, as we will discuss further in the following sections, this demand cannot be defined easily in the case of public products and services, compared to market-based products and services.

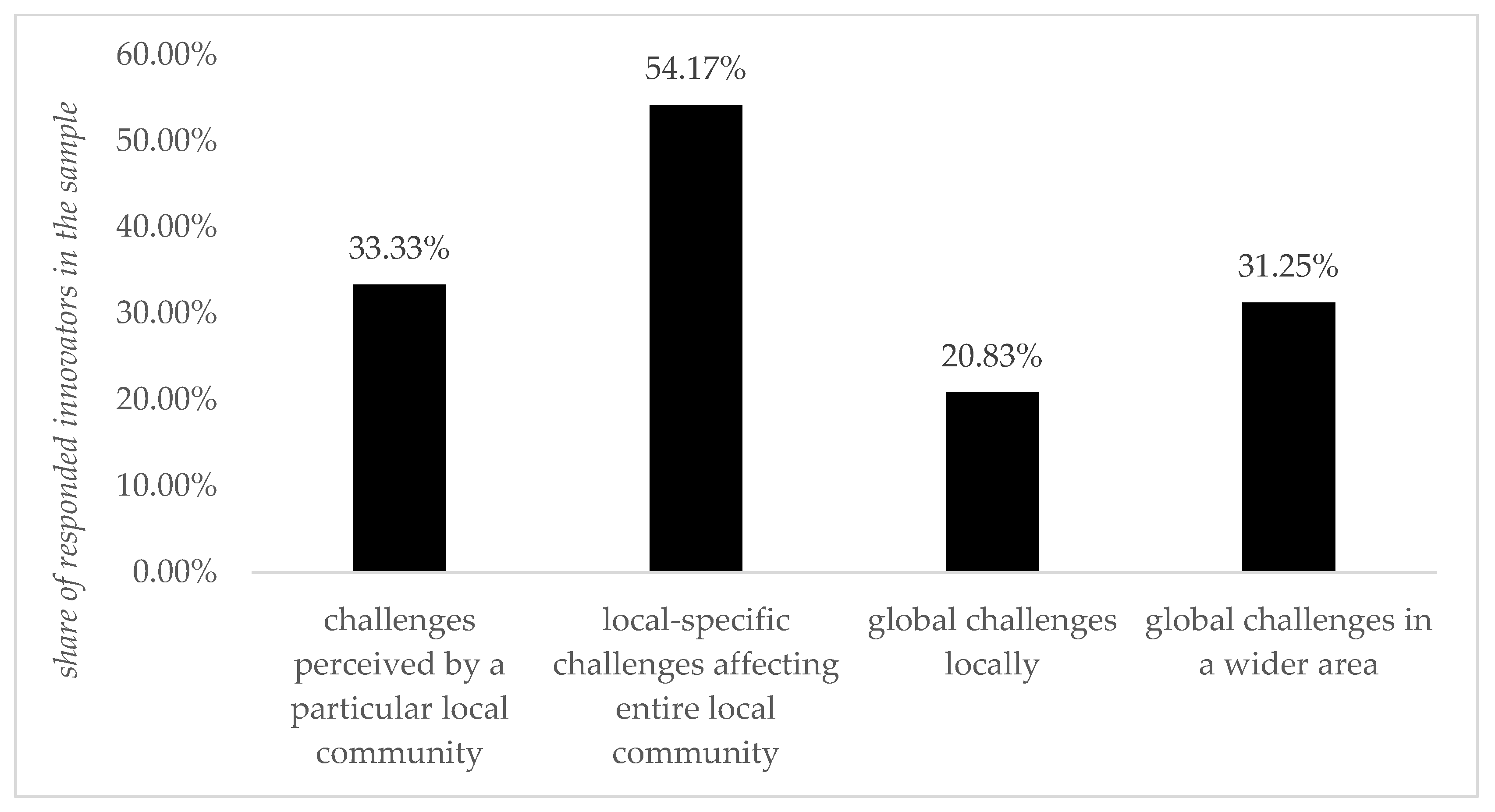

Concerning the capability of identified products and services to address various social and societal challenges, our definition of SI allows us to include both solutions that address local and global challenges.

Figure 1 shows the share of SI in the sample addressing societal challenges of various levels. The results suggest that community-led SIs primarily address challenges of local development. More than 50% of respondent grassroots that delivered SIs stated that their solutions do not primarily affect just their own community but also local issues in a broader context. According to statements of several respondents that introduced term “global issues”, they mostly referred to ongoing social and environmental crises, which could also affect local development (migration crisis, COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, etc.).

In further chapters, we will focus on the core interests of this study in terms of the evaluation of the public- or market-based nature of these SI products and services. However, to summarize, up to 12 of 48 social innovators provided their products and services in several NUTS III regions in the country in 2022, while rest of the initiatives delivered these new solutions on the local level. Together, the 48 social innovators employed up to 432 permanent employees in 2022, employed another 130 seasonal employees, provided the opportunity for the self-realization of 3917 volunteers, and reported an annual total expenditure of EUR 8,827,717, of which 69.13% was covered by grants and 19.06% by resources pooled from within the community, on average.

4.2. “Pure”, “Bi-Focal”, and “Market-Exposed” SIs

Within this section, we seek answers to research question Q1, which proposes a better understanding of the position of community-led social innovations in social or market systems.

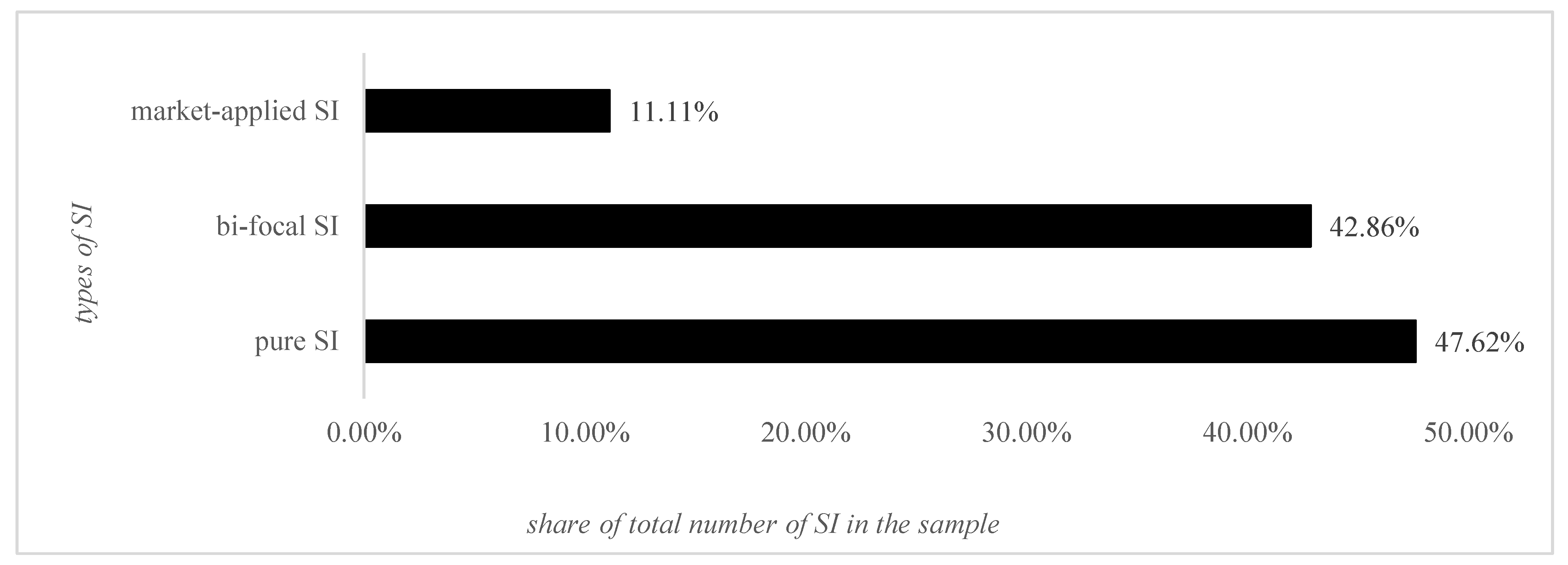

Figure 1 below shows the relative frequency of social innovations in the obtained sample of grassroots according to the level of market exposure of SI. It was possible to deliver this quantification due to the assessment of the degree of market applicability of the given innovations during the guided interviews. As a result of the initial focus groups on the “bi-focal” nature of SI, we define bi-focal SI as a product or service that (1) is provided free of charge to its own community or selected specific communities, (2) has a publicly beneficial nature, (3) at least some groups of consumers are charged, and (4) the competition can be identified at least on the level of micro-scale market. Market-exposed SIs within our analytical framework do not meet the condition of a product or service being provided in a “free of charge” regime to selected communities. The share of a type of SI in the sample according to the level of market applicability of the SI is provided in

Figure 2.

The partially commercial or purely commercial nature of SI products and services could be identified in more than 50% of cases. If we take into account the share of pure SI in the sample, then up to 87.3% of them are potentially marketable. These conclusions disprove the frequent assumption that social innovations arising outside of entrepreneurial systems are predominantly “pure” in nature. Simply put, all identified social innovators meet the key attributes of the SI definition, but the philosophy behind the innovation process as well as the methods of providing the given products and services to various stakeholders are significantly differentiated. In this context, the representative of the civil association “Priestory pre tvory” adds “The community garden is a space for all residents of the city, who can visit it, relax in it and enjoy contact with diverse biodiversity. The rental of plots is, however, connected with the provision of services to gardeners, for which it is necessary to pay. Our educational activities are also divided into those that we provide for free as part of our social mission and those that are supposed to secure additional financial resources”.

“Pure” social innovations can be understood as solutions addressing social, environmental, and cultural challenges and generating predominantly social impacts. These solutions cannot be delivered within the mechanisms of the market economy. Since we are talking in the context of product and service innovations, their important attribute is that they are available free of charge. “Pure” SI products and services are generated more frequently in the case of grassroots initiatives whose community is united by (1) philanthropic beliefs or (2) intentions to support marginalized communities. These “pure” SI solutions provide absent, publicly beneficial services; provide absent infrastructure; or represent a social movement striving to raise the dynamics of social change or induce a shift within the structure of values in society. The identified “pure” innovative products and services can be split into two groups. First group include grassroots focusing on the provision of social and health services. The examples are very diverse—from setting up community refrigerators in public spaces, mediating the adoption of beds for the homeless, introducing public harm-reduction services for drug users, or knock-knock services for seniors. The second group consist of solutions supporting the well-being of the community, or rather the general public within a local development, through diverse social, cultural, or environmental solutions. Examples include the construction of educational forest cycle paths, public bicycle workshops, DIY repair shops, site-specific public arts, and adoption of trees in the city.

However, we also identified a relatively high number of “bi-focal” social innovations that simultaneously exist in social and commercial regimes. Based on the coding of certain features of “pure” and “bi-focal” SIs, it can be observed that while “pure” SIs are frequently generated by smaller, voluntary-based and DIY-activity-based grassroots, “bi-focal” SIs are delivered by more established and professional grassroots. To better explain, in the case of “pure” SIs (for example, organizing cultural events or strengthening ecosystem services), such a services can be provided by small groups of volunteers without the participation of professionals, with limited know-how and knowledge, or with access to significant financial capital. The provision of commercial services by NGOs appears to be much more demanding. Grassroots that have delivered “bi-focal” SIs tend to engage in larger-scale projects, collaborate with more significant spatial actors, start to employ professionals, and apply more advanced managerial models. But, the main feature of “bi-focal” SI products or services is that that both generate additional income while also existing in a mode by which it can also be consumed on a “free-rider” principle. Standard examples in the sample are community gardens, hybrid cultural and creative centers, bike-sharing, community schools, therapeutic greenhouses, and many others.

In the data from up to 21 respondents, we identified instances where their solutions were initially “pure” and subsequently “shifted” into the commercial sphere or additional commercial projects were created in addition to “purely” social action. Furthermore, the vast majority of grassroots in the sample that delivered “bi-focal” SIs declared that the evolution of commercial solutions took place in parallel with the evolution of the grassroots initiative itself. These evolutionary patterns are well documented, for example, through the story of the civic association “Otvor dvor”, alongside which the cultural–creative center “Kláštor” was established. The managers of Kláštor state: “In the first years of initial NGO existence, we devoted ourselves to low-threshold and low-cost activities in the city’s public space, such as craft markets, music events, art and photography exhibitions, activities of museum, and green activities in public space. Our effort to build a strong creative cluster within the city met with the understanding of the local government, which, thanks to our activity, made the decision to provide an important historical building of the former monastery to the purpose of building a creative center. It was the impetus to start development of commercial activities in addition to philanthropic activities”.

However, the question still remains whether there are also services (considered to be SIs) that are exposed to the market from the first moment of their provision, which are of a commercial nature but can still be community-driven and address selected social challenges. We have identified several innovations that can be considered fully commercial while being provided by actors of the third sector. Such types of solutions represent, e.g., urban agriculture projects led by citizens that are connected to short supply–customer networks and generate a certain profit for civil organizations, such as the cultural–creative center “Kláštor”, which, after the revitalization of the historical monastery, established a hybrid platform anchored in both the third sector and private sector, social co-working, and the facilitation of community-based planning led by civic activists. Another example is the civic initiative dedicated to the revitalization of public spaces, which provide “tree adoption” services to the public. In this case, tree adoption secures resources both for the materials and labor required to plant new trees within a city.

An eminent example of a social solution that needed to use emerging markets to fulfil its goals is the project of the third-sector organization “Black Holes”, which aims to create social pressure to solve the problems of the deterioration of key technical cultural heritage and to ensure, in this context, the education of the population and enlightenment. However, to fulfil these goals, they adopted a market-based approach. The NGO provides opportunities for artists from all over the country to create unique graphics of cultural heritage in editions that are tied to individual cities and regions. The number of copies of each edition is limited and one copy costs approximately EUR 20–30. However, their collector’s value is growing rapidly due to the enormous and largely unsatisfied demand: after 1–2 years from the issue of the edition, these copies are the subject of auctions and their value reaches 10–20 times the original price. We, therefore, use the term market-applied social innovations to denote commercial solutions that pursue societal change objectives in the first place. Such solutions could be a natural result of innovative activity in social enterprises, but our argument is that community-led civic initiatives can also be a source of market-exposed SIs.

To conclude the research question (Q1), it was possible to identify “pure”, “bi-focal”, and also the market-exposed SIs. We hypothesize that the commercialization of community-led grassroots solutions is mainly a source of obtaining additional income for institutions, but in rare cases it can also be associated with entrepreneurial intentions. Products and services can fulfill the social missions of initiatives and at the same time be market-exposed. Also, we identified a paradox—the solutions of activists and philanthropists in certain circumstances require commercialization and entry into markets in order to secure the stability and sustainability of their provision in the long term.

4.3. Evolutionary Patterns of Bi-Focal SIs Emergence ad Conceptualization of Demand for SIs

At this point, we want to highlight the research question (Q2) that seeks answers to the question of whether it possible to conceptualize the demand for community-led products and services. In this case, our intention is to evaluate the experiences of managers of grassroots initiatives that introduced “bi-focal” SIs, as it follows from the respondents’ statements that many were prototyped and tested within community-based social systems and their market exposure occurred later. Thus, in this section, we will deal with the potential evolution of SI in the conditions of grassroots initiatives, where, over time, the solution can hypothetically move from the social sphere to the commercial sphere.

Our intention is to demonstrate a potential scenario of the transition of a solution delivered for the needs of the community into a partially commercial mode. Our goal is to build a demonstrative process model, divided and evaluated using individual phases of the product life-cycle. The selection of cases for the creation of this model was based on simple requirements, namely, to select a group of “bi-focal” SIs in the sample that had similar evolutionary characteristics in the individual phases of their life-cycles in the observed context. For this reason, our life-cycle model is constructed based on five specific examples of community gardens, community schools, or bike-sharing (

Figure 3). In particular, we will observe whether the patterns of demand change within individual phases of the life-cycle.

All of the above-mentioned examples of SIs in the sample show quite similar evolutionary patterns within their life-cycles. These solutions were initiated by specific members of active communities of grassroots initiatives (SI creation phase) and subsequently implemented (or pilot solution tested) thanks to the co-deployment of knowledge rooted in the community, voluntary work, and a combination of the initiative’s own resources and external funding sources. During pilot testing and initial operation for a period of 1–3 years, the given products and services could be understood as being publicly available, or available to a limited group of consumers based on the “free-rider” principle. This 1–3-year period can be thought of as the seed phase of SI. Subsequently, in the scale phase, the number of consumers who are interested in using the given solution grows. Community gardens are expanding, bike-sharing is increasing the number of bicycles provided, community schools are expanding the number of students, and the number of customers of therapeutic gardens or greenhouses is growing. This phase can be associated with the introduction of fees and price mechanisms, with the development of price differentiation of products and services, the professionalization of the activity, and the improvement of organizational aspects of the product or service provision.

The community gardens and the community schools in the sample have already entered the graduation phase, as they have been in operation for approximately 7–15 years. At the beginning of this stage, there was a visible price shift associated with the provision of services. The prices moved from “symbolic”, related to the predominant use of the solution within the community, closer towards market prices, due to growing demand. The closer the price of renting a field in a community garden gets to the market price of renting a garden of a given size, the closer the fees of a community school are to the real costs per pupil in a conventional private school. There are positive but also negative externalities resulting from increasing the scope of these activities. Since the scale phase, the growing scope of activities appears to be associated with the introduction of further organizational, process-based, or marketing innovations. It appears that bi-focal and market-exposed SIs forms micro-scale markets. The discontinuity of a given product or service can be associated with the process of creative destruction in the same way this process occurs in conventional technological innovations in the private sector (let us say that new, better organized community gardens are being formed that can be associated with the purchase of surplus and the creation of small chains at the local level, providing innovative services to growers, which may cause a decrease in interest in fields in other gardens). However, in the opinion of some respondents, due to the fact that grassroots are community-led, their projects have a DIY nature, and these projects are co-designed and co-managed, some of the solutions in the sample are mainly threatened by a lack of resources, the overflow of residents between multiple communities, and by the changes in demand and value structures in the community.

Thus, it appears that the demand for SI services changes during the life-cycle of the services. Also, grassroots utilize a specific form of price discrimination. In the case of up to 14 products or services in our SI sample, we identified that the community is usually offered discounted rate. The provision of services is, in some cases, free for community members but charged to the public. According to the information obtained from representatives of grassroots initiatives, this discrimination is primarily driven by the interest to reward volunteers for participating in the co-creation of a solution. There have also been some cases of price discrimination aimed at correcting market failure—especially in the case of certain social and educational services being provided free of charge to marginalized groups, while non-marginalized consumers are charged.

In the context of answering research question Q2, it can be noted that it is necessary to distinguish the interest of target groups to use certain solutions (which can be public goods of a publicly beneficial nature) from demand in the economic sense, which is realized based on the market. In this regard, it can be stated that, in limited cases, there may be a demand for publicly beneficial solutions in relatively strong, existing markets in the same sense as for conventional technological innovation, as long as it generates social benefits. The activities of community-led initiatives rather lead to the formation of small-scale services and micro-markets, as there is an increased interest from the urban population to take a part in community-based activities. Examples include farming in the city, natural therapies, or raising a child in a community kindergarten. It appears that there is growing willingness to pay for such services.

4.4. SI Contributions to Social and Economic Value Creation

Within this section, we want to further contribute to the discussions on the fundamental nature of the societal (or specifically social) and economic value that SIs generate. As we explained in the third section, instead of trying to quantify the societal or social value, we will try to describe what societal value in the case of the identified SI products and services “consists of”, adopting the framework of Nicholls [

46]. However, in the case of bi-focal and market-applied SIs, we will expand our interpretations using descriptions of economic outcomes, especially related to the types of income from services provided in various markets. As it is very unimaginative to perform a comparative analysis based on 63 cases, we executed stratified sampling, within which we first divided the population of identified SIs into subgroups based on their level of market exposure and then further into groups according to the following characteristics: (1) age and experiences, (2) location within urban/rural settlement, (3) main target groups, and (4) focus on interventions within various fields—social and health services, environment, culture and arts promotion, infrastructure and mobility. Thus, our effort was to arbitrarily and intentionally select a highly diversified group of five social innovations of a “pure”, “bi-focal”, and “market-exposed” nature for the comparison of social and societal value or economic outcomes.

The results are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The results demonstrate that it is possible to differentiate SIs that address the needs of broader society, specific interest groups, marginalized communities, or only the communities of specific interest. First of all, it can be stated that “pure”, “bi-focal”, and “market-exposed SIs” addressed the needs and problems of various target groups. It is not the case that market-exposed SIs must necessarily be subject to consumption by any potential consumer. To provide an example, food sales via a box scale system can only take place for a fee within a limited community of consumers when the community and its uniform preferences become a source of entrepreneurial opportunity. In the case of “pure” SIs, the “consumption” of publicly available products and services can also be limited. A number of the respondent initiatives limit the consumption of these goods and services to selected communities. Most often, grassroots provide for their own communities or the marginalized groups they support.

It was identified that social and societal value arises both from non-commercial, partially commercial, and commercial products and services of grassroots communities. In all 15 compared cases, the initiatives consider the achievement of social outcomes to be the main motive for the implementation of the given interventions. The societal outcomes are, in many aspects, comparable in the case of the individual SI types. We consider our assumption that the SIs of grassroot initiatives fill empty places in satisfying societal needs that arise from market failures. The innovations of community-led grassroots initiatives address a wide spectrum of social, environmental, and cultural issues, especially within local development, but some grassroots appear to have the capacity to address more complex issues in a relatively wide area, mostly at the national level. Social outcomes, such as the growth of the population’s physical or mental health, improvement of the quality of the environment, development of ecological mobility, reduction of CO2 emissions, re-education of homeless people or drug addicts can be considered as proper examples of social outcomes that classic Schumpeterian innovations rarely lead to.

Likewise, “pure”, “bi-focal”, and “market-exposed” SIs can lead to shifts and changes in the structure of social values. This fact was well captured by the representative of an NGO that organizes children’s summer camps, providing services in the field of therapeutic theater: “It would be quite possible to manage these activities through a business as well. As long as the entrepreneur provides services that lead to improvement of health of a disadvantaged child and his integration to the majority of society, the service definitely brings not only social outcomes, but supports the mindset change in society. Such a venture still does not need to be established as a social enterprise”. The main identified values connected with the provision of community-led goods and service by grassroots include environmental sustainability, tolerance, engagement, equity and justice, altruism and solidarity, and healthy lifestyle and safety. Both non-market-exposed and market-exposed SIs enhanced the competences of target groups in various ways, but mostly in terms of the acquisition of knowledge and skills. In the case of marginalized communities consuming in-field social and health services, we can, for example, speak about survival and improvements in health status.

The “pure” SIs did not really deliver economic value in our comparison apart from the generation of some savings on the side of consumers of public services. However, the bi-focal and market-applied SIs contributed to the creation of economic value. As can be seen from the results in

Table 2, the provision of services by the market-applied SIs is clearly associated with financial exchange. These grassroots initiatives have been generating income from their activities since the early stages of SI development. They have mainly adopted the “business NGO” model recognized by Slovak legislation, which represents a specific form of business activity of NGOs connected with the provision of publicly beneficial activities. Also, up to four out of five commercially applied SIs in

Table 2 were a source of permanent employment. A secondary benefit of grassroots within local development results from their ability to support the activities of other actors due to the accumulation of knowledge. After several years of operation, many of the investigated grassroots started to provide secondary services in the local economy in order to generate additional profit—especially consulting in the field of NGO operation, financial services, services in the field of project management, the creation of marketing campaigns, etc.

Regarding research question Q3, it seems that if a product or service provided by community-led grassroots initiative is at least introduced to micro-scale markets, we can consider these solutions to generate a mixture of social and economic outcomes leading to the generation of both social and economic value. Economic outcomes are represented at the level of initiative by the acquisition of pre-operational environments that are reinvested in other activities or by the birth of entrepreneurial ideas that can be transformed into business development. At the level of the local economy, we can talk about economic outcomes in the terms of direct economic effects, savings on the part of the local government and affected communities, employment growth, and also networking, skills building, and knowledge dissemination. We hypothesize that the establishment of socially beneficial solutions in market systems does not necessarily lead to reductions in social and societal outcomes.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The SI literature has a relatively short history and can be considered relatively fragmented to date [

35]. Our study contributes to the debate on the emergence of SIs in the conditions of grassroots communities, which have been repeatedly identified as a source of new, sustainable, publicly beneficial products, services, technologies, processes, and organizational models [

19,

20,

26,

27].

Several gaps in knowledge have been addressed.

We established new hypotheses in the field of “pure”, “bi-focal”, and “market-exposed” SI evolution [

9], the

conceptualization of

the demand for SI [

38],

the determination of the social and economic value that SIs can generate [

2].

To conclude research question Q1, it was possible to identify “pure”, “bi-focal”, and market-exposed SIs [

2,

9]. The majority of products and services provided by grassroots can be considered as social innovations. Also, the majority of identified social innovators deliver “pure” SIs. Their introduction is the initial goal of a grassroots community initiative that wants to contribute to solving local or global social, cultural, or environmental challenges. But, as suggested by Van Der Have and Rubalcaba [

2], the provision of solutions addressing societal challenges or the needs of the specific (let us say the disadvantaged) target groups can be also linked to an entrepreneurial intention. We hypothesize that the commercialization of community-led grassroots solutions is mainly a source of obtaining additional income for institutions [

3,

27], but in rare cases it can also be associated with entrepreneurial intentions. Products and services can fulfill the social missions of initiatives and at the same time be market-exposed. Also, we identified a paradox—the solutions of activists and philanthropists in certain circumstances require commercialization and entry into markets in order to secure the stability and sustainability of their provision in the long term.

In the context of answering research question Q2, it can be noted that it is necessary to distinguish the interest of target groups to use certain solutions (which can be public goods of a publicly beneficial nature) from demand in the economic sense [

52], which is realized based on the market. In this regard, it can be stated that, in limited cases, there may be a demand for publicly beneficial solutions in relatively strong, existing markets in the same sense as for conventional technological innovations, as long as it generates social benefits [

38]. The activities of community-led initiatives lead to the formation of small-scale services and micro-markets, as there is increased interest from the urban population to take a part in community-based activities. Examples include farming in the city, natural therapies, and raising a child in a community kindergarten. It appears that there is growing willingness to pay for such services

Regarding research question Q3, it seems that if a product or service provided by a community-led grassroot initiative is at least introduced to micro-scale markets, we can consider these solutions to generate a mixture of social and economic outcomes leading to the generation of both social and economic value [

46]. Economic outcomes are represented at the level of the initiative by the acquisition of pre-operational environments that are reinvested in other activities or by the birth of entrepreneurial ideas that can be transformed into business development. At the level of the local economy, we can talk about economic outcomes in terms of direct economic effects, savings on the part of the local government and affected communities, employment growth, and also networking, skills building, and knowledge dissemination. We hypothesize that the establishment of socially beneficial solutions in market systems does not necessarily lead to reductions in social and societal outcomes. The problem is that we can only talk about the formation of micro-markets, which, in many cases, are only of local significance. Therefore, in accordance with Rhodes et al. [

10], we express doubts regarding the ability of SIs generated by grassroot initiatives to significantly increase the complexity of addressing selected societal challenges within higher territorial systems; although, they can be a significant source of both social and economic local development.

We, therefore, refer to the study by Porter and Kramer [

6], which argues that public support for innovation action leads to the creation of solutions that can address development issues at different spatial levels. In this context, solutions emerging within civic-led systems can help to fix a number of market and system failures emerging within current economic systems on the local level [

5].

Our research design has several limitations. First of all, our sample of grassroots represents a sample obtained through snowball sampling and it is difficult to evaluate its significance, due to the inability to define the exact size of the population. Secondly, a certain distortion of reality can occur through the subjective attitudes of the managers of grassroot initiatives presented in the guided interviews and in the questionnaire. This study’s analytical design was based on the comparison of a large amount of data across a large number of grassroot initiatives and SIs, which resulted in the need to arbitrarily decide on the choice of objects for the comparison.