Intergenerational Leadership: A Leadership Style Proposal for Managing Diversity and New Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

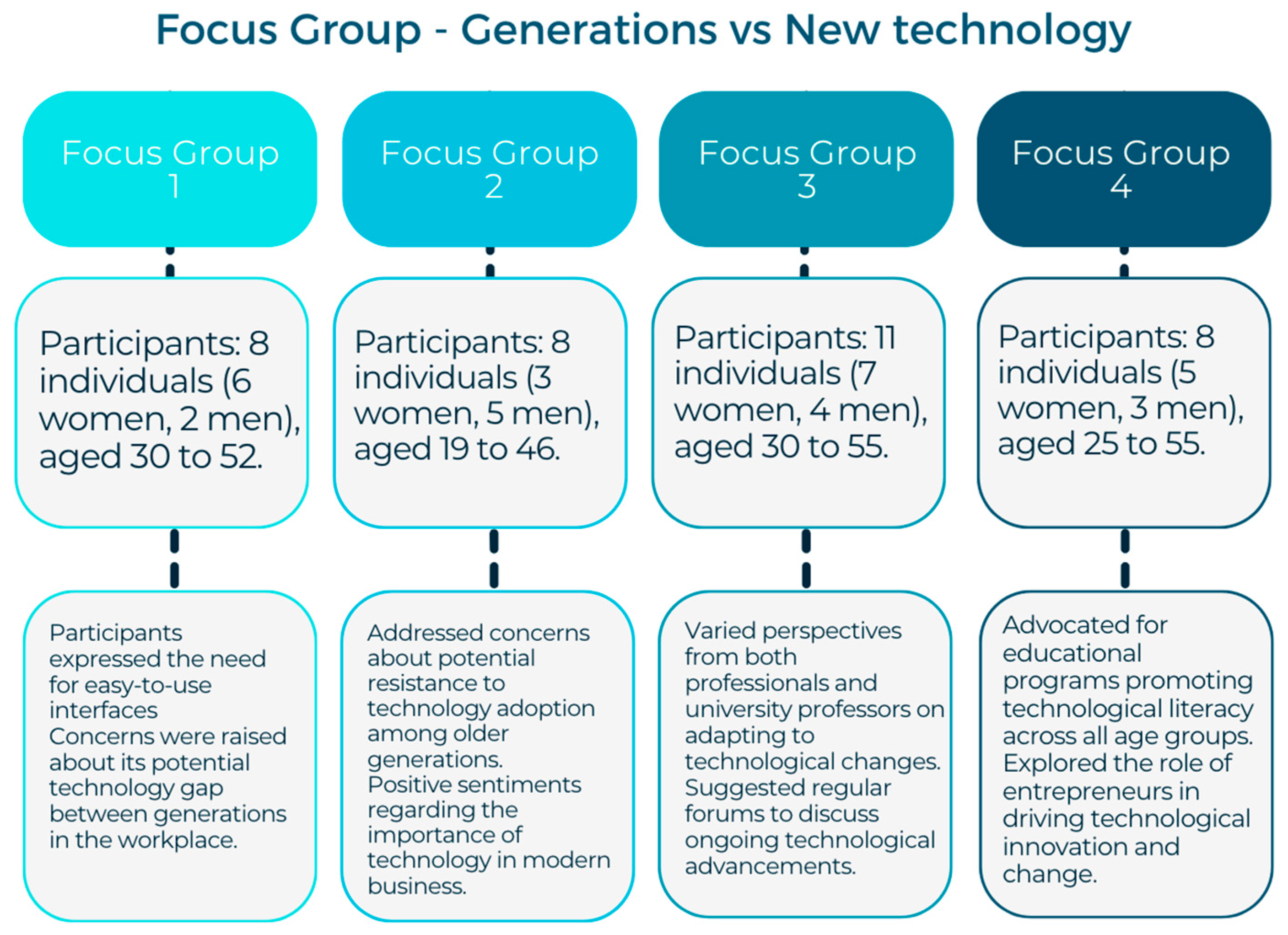

2. Methodology

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Sample

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

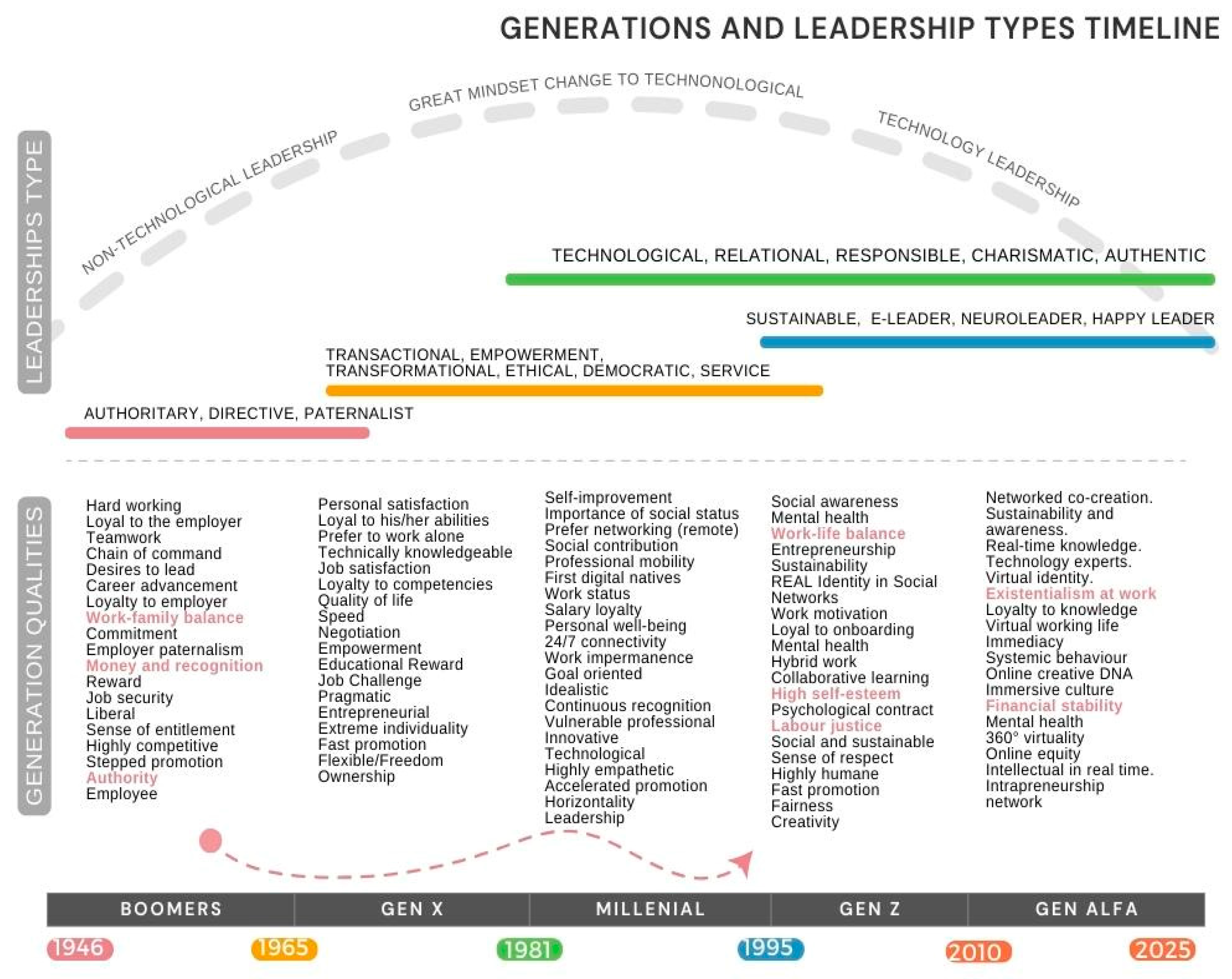

3.1. Characterisation of Each Generation

3.1.1. The Baby Boomers

3.1.2. Generation X

3.1.3. Millennials

3.1.4. Generation Z

3.1.5. Generation Alpha

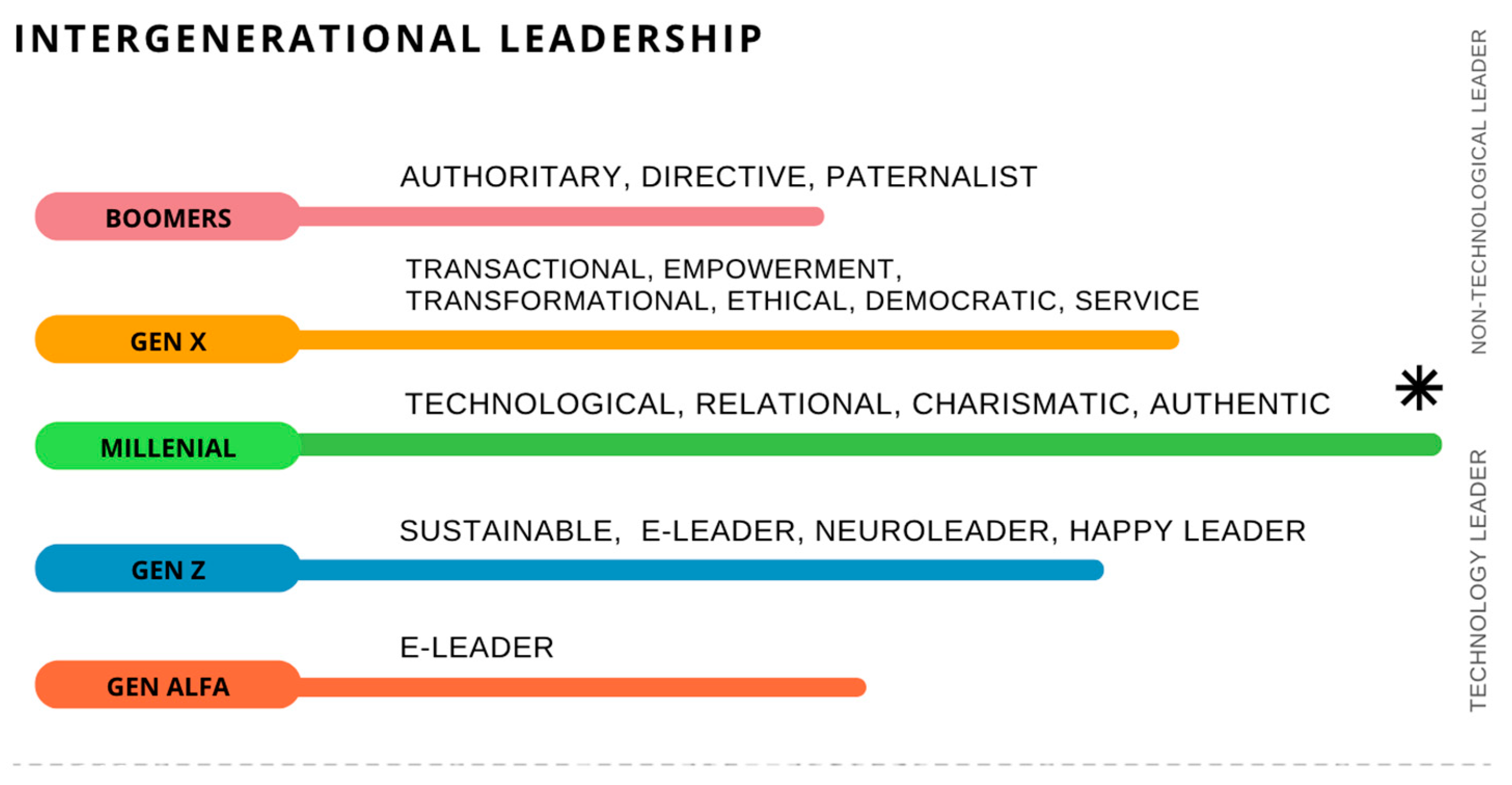

3.2. Leadership Styles and Generations

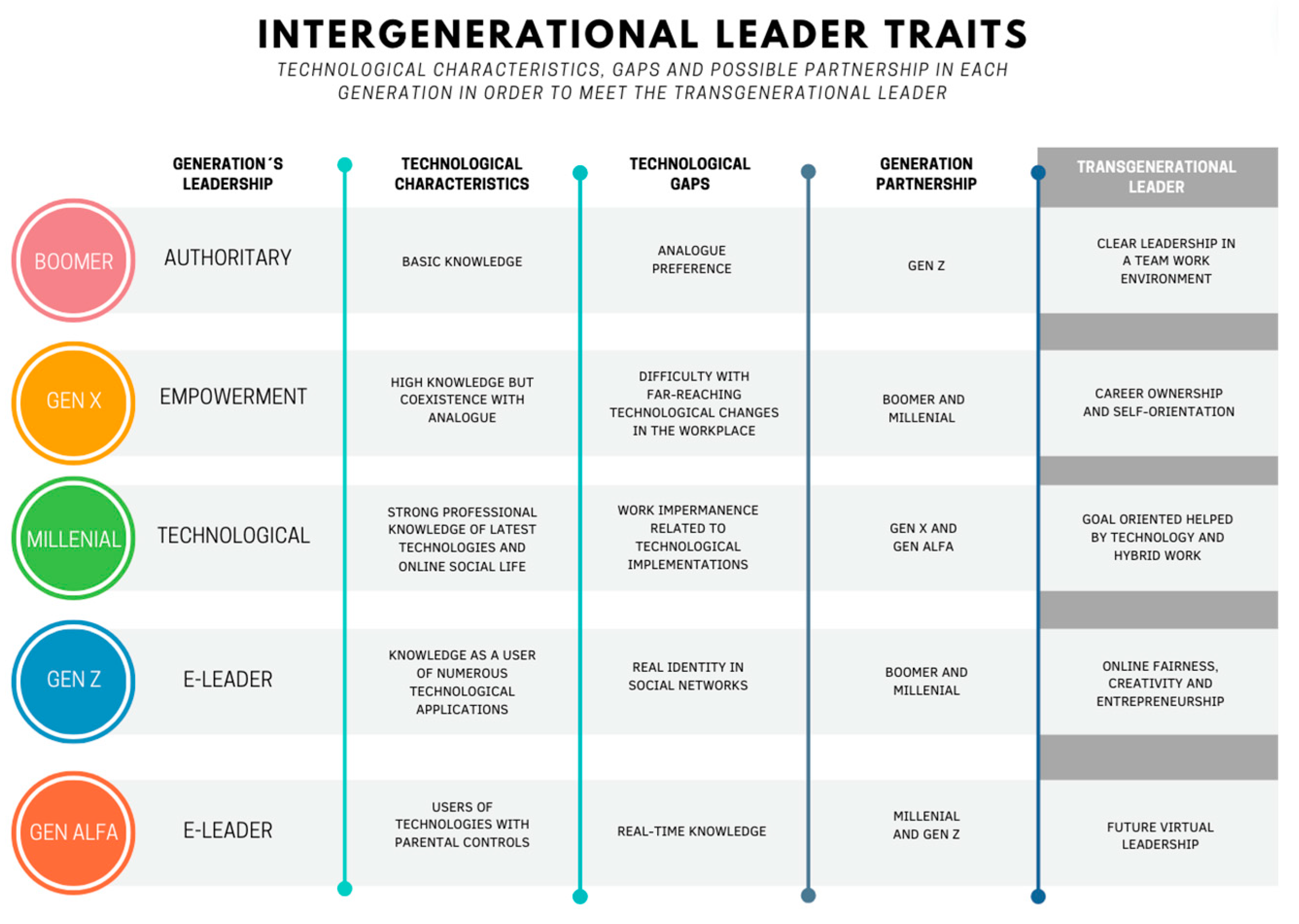

4. Proposal for a New Style of Leadership: Intergenerational Leadership

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carter, D. Immersive employee experiences in the metaverse: Virtual work environments, augmented analytics tools, and sensory and tracking technologies. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2022, 10, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.M.; Kim, Y.G. A metaverse: Taxonomy, components, applications, and open challenges. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 4209–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S.; Giannakis, M.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Dennehy, D.; Metri, B.; Buhalis, D.; Cheung, C.M.; et al. Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, R. An empirical study of leadership theory preferences among Gen Y in Malaysia. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014, 3, 398–421. [Google Scholar]

- Wolor, C.W.; Nurkhin, A.; Citriadin, Y. Leadership style for millennial generation, five leadership theories, systematic literature review. Calitatea 2021, 22, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Moh’d Futa, S. The impact of leadership styles used by the academic staff in the Jordanian public universities on modifying students’ behavior: A field study in the northern region of Jordan. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, D.Y. Mood management through metaverse enhancing life satisfaction. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomislav, K. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, S.; Wilska, T.A.; Gilleard, C. (Eds.) Digital Technologies and Generational Identity: ICT Usage Across the Life Course; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Lim, W.M.; Dabić, M.; Kumar, S.; Kanbach, D.; Mukherjee, D.; Corvello, V.; Piñeiro-Chousa, J.; Liguori, E.; et al. Literature reviews as independent studies: Guidelines for academic practice. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 2577–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulgan, B. Managing Generation X: How to Bring Out the Best in Young Talent; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.C.; Miller, P. Leadership style: The X Generation and Baby Boomers compared in different cultural contexts. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardyan, T.M.; Bakri, M.R.; Utami, A. Generation gap in fraud prevention: Study on generation Z, generation X, millennials, and boomers. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 361–375. [Google Scholar]

- Sagituly, G.; Guo, J. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: Comparing Generations X and Y. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Gao, G. Generation X: America’s Neglected ‘Middle Child’. 2014. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2014/06/05/generation-x-americas-neglected-middle-child/ (accessed on 26 July 2017).

- Wang, A.C.; Chiang, J.T.J.; Tsai, C.Y.; Lin, T.T.; Cheng, B.S. Gender makes the difference: The moderating role of leader gender on the relationship between leadership styles and subordinate performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 122, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumus, S.; Bellibas, M.S.; Esen, M.; Gumus, E. A systematic review of studies on leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinnioğlu, H. A review of modern leadership styles in perspective of industry 4.0. In Agile Business Leadership Methods for Industry 4.0.; Akkaya, B., Ed.; Emerald: Leeds, UK, 2020; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Manzanares, M.; Rico, R.; Antino, M.; Uitdewilligen, S. The joint effects of leadership style and magnitude of the disruption on team adaptation: A longitudinal experiment. Group Organ. Manag. 2020, 45, 836–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods. In The Search for Meanings; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannheim, K. The problems of generations. In Childhood: Critical Concepts in Sociology; Jenks, C., Ed.; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; Volume 3, pp. 73–285. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Dencker, J.C.; Franz, G.; Martocchio, J.J. Unpacking generational identities in organizations. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2010, 35, 392–414. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, C.M.; Aronson, J.A. Stereotype threat does not live by Steele and Aronson (1995) alone. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.J. Managing identity: Identity work, personal predicaments and structural circumstances. Organization 2008, 15, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanapon, K.; Jorissen, A.; Jones, K.P.; Ketkaew, C. An Analysis of Multigenerational Issues of Generation X and Y Employees in Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Thailand: The Moderation Effect of Age Groups on Person–Environment Fit and Turnover Intention. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Maier, T.A.; Chi, C.G. Generational differences: An examination of work values and generational gaps in the hospitality workforce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, C.S.A.; Toscano, C.D.A. ¿Los Millennials tienen actitudes y habilidades para la socialización? E-IDEA J. Bus. Sci. 2021, 3, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudeva, S. Age in the Acceptance of Mobile Social Media: A Comparison of Generation Y and Baby Boomers Using UTAUT2 Model. Int. J. E-Adopt. (IJEA) 2023, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, H. Are you ready for Gen Z in the workplace? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.M.K.; Hassan, M.M.; Alam, M.K.; Thakur, O.A.; Nasrin, H. The impact of extrinsic motivation and work-life balance on generation y’s contentment of private sectors in bangladesh. J. Nusant. Stud. (JONUS) 2023, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuro Somma, L.; Bercovich, N. El nuevo Paradigma Productivo y Tecnológico: La Necesidad de Políticas para la Autonomía Económica de las Mujeres; CEPAL: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, D.K. Increasing digital dissemination and online apparel shopping behaviour of Generation Y. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2023, 28, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, T.; Darmawati, A.; Kuncoro, A.M. E-lifestyle confirmatory of Consumer Generation Z. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, R.M.; Morales, O.; Timana, J. Work–life balance and work values as antecedents of job embeddedness: The case of Generation Y. Acad.-Rev. Latinoam. Ad. 2022, 35, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chaudhuri, S.; Sihag, P.; Shuck, B. Unpacking generation Y’s engagement using employee experience as the lens: An integrative literature review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2023, 26, 548–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J.C. Millennials as digital natives: Examining the social media activities of the Philippine Y-generation. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 28, 1939–1957. [Google Scholar]

- Olckers, C.; Booysen, C. Generational differences in psychological ownership. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2021, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, A.V. La generación Y ante el desafío de su inserción laboral: Realidades frente a estereotipos. Arbor 2017, 193, a375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattingh, W.; Van den Berg, L.; Bevan-Dye, A. The “why” behind generation Y amateur gamers’ ongoing eSports gameplay intentions. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2023, 25, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziriri, E.T.; Mashapa, M.M.; Nyagadza, B.; Mabuyana, B. As far as my eyes can see: Generation Y consumers’ use of virtual reality glasses to determine tourist destinations. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2246745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, G. Determinants of Digital Payment Services and Behavioral Loyalty among Generation Y. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4243754 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Nosi, C.; D’Agostino, A.; Piccioni, N.; Bartoli, C. Becoming a tree when I will be dead? Why not! Generation X, Y and Z, and innovative green death practices. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhore, M.; Pandita, D. An Exploratory Study of The Gen Z and E Generation in the Digital Era for the Modern Business Environment. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Business and Industrial Research (ICBIR), Bangkok, Thailand, 19–20 May 2022; pp. 406–410. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. Challenges and issues of generation Z. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 16, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorgulescu, M.C. Generation Z and its perception of work. Cross Cult. Manag. J. 2016, 18, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolski, Z.; Drozdowski, G.; Panait, M. Understanding the impact of Generation Z on risk management—A preliminary views on values, competencies, and ethics of the Generation Z in public administration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.M.; Opland, R.A.; Ryan, A.M. Psychological contracts and counterproductive work behaviors: Employee responses to transactional and relational breach. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekić, I.; Ivanković, J.; Bednjanec, A. Analysis of the entrepreneurial orientation of Generations Z and Y. Ekon. Misao Praksa 2023, 32, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera, I.L. El futuro de la cultura digital de la generación Alfa en México. Econ. Creat. 2022, 18, 180–209. [Google Scholar]

- Asni, Y. Alfa Generation in ELT: Teachers’ perspective. ETERNAL 2023, 9, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Atwater, L. The transformational and transactional leadership of men and women. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 45, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G.; Kha, K.L. A bibliometric analysis of influence of leadership styles on employees and organization in higher education sector from 2007 to 2022. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2023, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakitapoğlu-Aygün, Z.; Gumusluoglu, L.; Erturk, A.; Scandura, T.A. Two to Tango? A cross-cultural investigation of the leader-follower agreement on authoritarian leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Lu, T.E.; Yang, C.C.; Chang, G. A multilevel approach on empowering leadership and safety behavior in the medical industry: The mediating effects of knowledge sharing and safety climate. Saf. Sci 2019, 117, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Müller, R.; Shao, J. Exploring the relationship between leadership and followership of Chinese project managers. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 13, 616–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.H.; Han, T.S.; McConville, D.C. A multilevel study of brand-specific transformational leadership: Employee and customer effects. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, W.G.; Cordeiro, P.A. Educational Leadership: A Problem-Based Approach; Allyn & Bacon/Longman Publishing, a Pearson Education Company: Needham, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Azizaha, Y.N.; Rijalb, M.K.; Rumainurc; Rohmahd, U.N.; Pranajayae, S.A.; Ngiuf, Z.; Mufidg, A.; Purwantoh, A.; Ma‘ui, D.H. Transformational or transactional leadership style: Which affects work satisfaction and performance of islamic universitylecturers during Covid-19 pandemic? SRP 2020, 11, 577–588. [Google Scholar]

- Suyudi, S.; Nugroho, B.S.; El Widdah, M.; Suryana, A.T.; Ibrahim, T.; Humaira, M.S.; Nasrudin, M.; Mubarok, M.S.; Abadi, M.T.; Adisti, A.R.; et al. Effect of leadership style toward Indonesian education performance in education 4.0 era: A schematic literature review. Sys. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Wahidin, B.; Wibowo, T.S.; Abdillah, A.; Kharis, A.; Jaenudin Purwanto, A.; Mufid, A.; Maharani, S.; Badi‘ati, A.Q.; Fahlevi, M.; Sumartiningsih, S. Democratic, authocratic, bureaucratic and charismatic leadership style: Which influence school teachers performance in education 4.0 era? Sys. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, L.B.; Bjørnholt, B.; Bro, L.L.; Holm-Petersen, C. Leadership and motivation: A qualitative study of transformational leadership and public service motivation. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2018, 84, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.A.; Gardner, W.L. Leadership in Organizations; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, R.; Levine, N.; Pitt, D.C. Leadership and organizations for the new millennium. J. Leadersh. Stud. 1999, 5, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D.; Schleu, J.E.; Hüffmeier, J. A meta-analysis of the relative contribution of leadership styles to followers’ mental health. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2023, 30, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasalak, G.; Güneri, B.; Ehtiyar, V.R.; Apaydin, Ç.; Türker, G.Ö. The relation between leadership styles in higher education institutions and academic staff’s job satisfaction: A meta-analysis study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1038824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potosky, D.; Azan, W. Leadership behaviors and human agency in the valley of despair: A meta-framework for organizational change implementation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2023, 33, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaja, O.M.; Ogunola, A.A. Leadership style and multigenerational workforce: A call for workplace agility in Nigerian public organizations. Leadership 2016, 21, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Putriastuti, B.C.K.; Stasi, A. How to lead the millennials: A review of 5 major leadership theory groups. J. Leadersh. Organ. 2019, 1, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, Z.D.; Mun, C.P.; Farhana, B.N.; Tarmizi, W.A.N. Influence of transformation leadership style on employee engagement among Generation Y. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2017, 11, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Iqbal, Q. Leadership styles and sustainable performance: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 134600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Fazal-E-Hasan, S.M.; Kaleem, A. How ethical leadership stimulates academics’ retention in universities: The mediating role of job-related affective well-being. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 1348–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, K. A review of the literature concerning ethical leadership in organizations. Emerg. Leadersh. Journeys 2012, 5, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wahidin, W.; Hamidah, H.; Damanik, M.R.M.; Fitria, A. Transformational Leadership, Training and Their Effects on Employee Engagement of Family Planning Fieldworkers in Indonesia. J. Int. Conf. Proc. 2020, 3, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M.M. Generational differences impact on leadership style and organizational success. J. Divers. Manag. (JDM) 2010, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R.K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Paulist Press: Macarthur Boulevard Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Erath, J. Qué es un líder Tecnológico. Available online: https://www.ironhack.com/es/blog/que-es-un-lider-tecnologico (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, M. The influence of responsible leadership on environmental innovation and environmental performance: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2016–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawan, I.; Evanirosa, R.A.; Ramadan, I.; Hanif, M.; Harun, I.; Hanum, L.; Purwanto, A.; Mufid, A.; Nurkayati, S.; Fahlevi, M.; et al. Develop model of transactional, transformational, democratic and authocratic leadership style for indonesian school performance in education 4.0 era. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.; Xu, A.; Lin, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, W. Environmental leadership, green innovation practices, environmental knowledge learning, and firm performance. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020922909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, K. E-Leadership: The emerging new leadership for the virtual organization. J. Manag. Sci. 2009, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gocen, A. Neuroleadership: A Conceptual Analysis and Educational Implications. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 9, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, R.; Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado, M.; Ravina-Ripoll, R. Neuroleadership: A new way for happiness management. Humanit. Soc. Sciences Commun. 2023, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, G.A.; Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado, M.; Ravina-Ripoll, R. Happy leadership, now more than ever. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramírez-Herrero, V.; Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado, M.; Medina-Merodio, J.-A. Intergenerational Leadership: A Leadership Style Proposal for Managing Diversity and New Technologies. Systems 2024, 12, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12020050

Ramírez-Herrero V, Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado M, Medina-Merodio J-A. Intergenerational Leadership: A Leadership Style Proposal for Managing Diversity and New Technologies. Systems. 2024; 12(2):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12020050

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamírez-Herrero, Virginia, Marta Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado, and José-Amelio Medina-Merodio. 2024. "Intergenerational Leadership: A Leadership Style Proposal for Managing Diversity and New Technologies" Systems 12, no. 2: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12020050

APA StyleRamírez-Herrero, V., Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado, M., & Medina-Merodio, J.-A. (2024). Intergenerational Leadership: A Leadership Style Proposal for Managing Diversity and New Technologies. Systems, 12(2), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems12020050