Addressing Complexity in Chronic Disease Prevention Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Context and Design

2.2. Recruitment

2.2.1. Case Selection

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Open Coding and Framework Analysis

2.3.2. Exploring How Systemic Approaches Were Operationalised

2.3.3. Representing the Whole

3. Results

3.1. Addressing Complexity through Systemic and Systematic Paradigms—Case Study Summaries

The Systemic and Systematic Paradigms Took Different Forms and Played out in Different Proportions within the Cases of Prevention Research

3.2. Expanding the Boundary: Comparing the Relative Proportions of Systemic and Systematic Paradigms

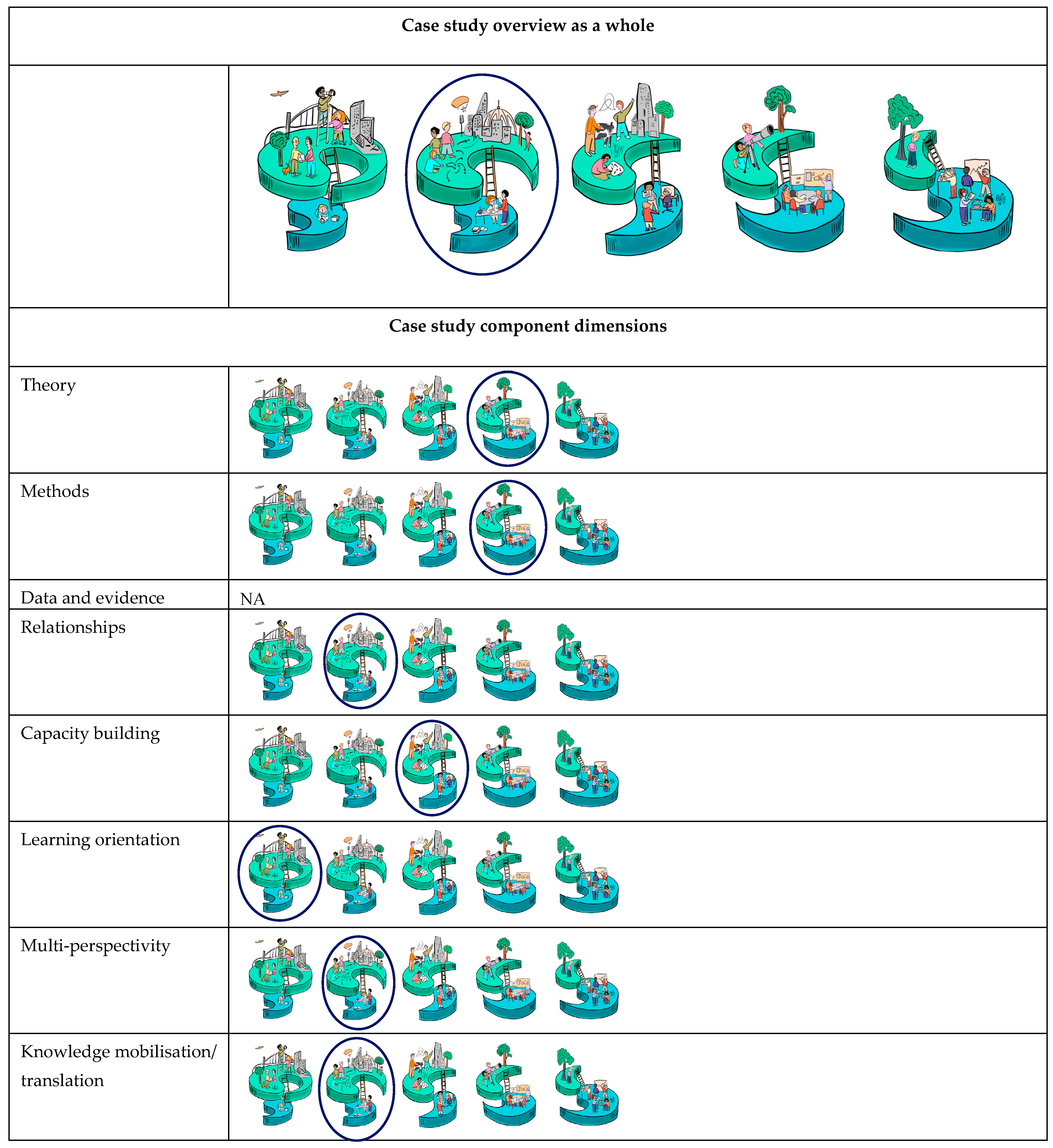

The Balance between the Systemic and Systematic Paradigms Appears to Vary When One Considers a Case as a Whole, When Examining the Individual Dimensions within That Work, and When Comparing across Case Studies

3.3. The Continuum: Changing the Relative Proportions of Systemic and Systematic Paradigms in Prevention Research

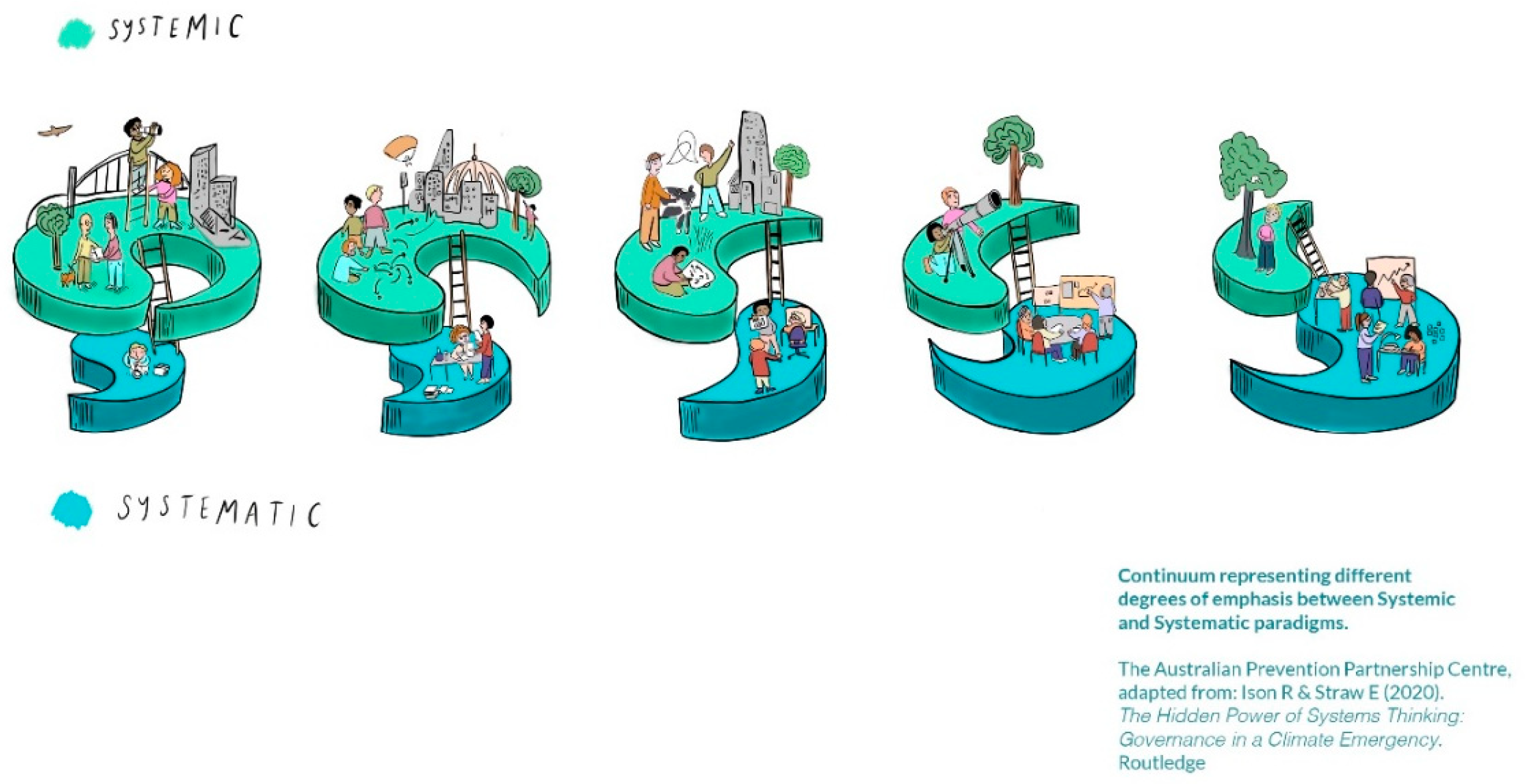

3.3.1. The Proportional Interplay between the Systemic and Systematic Paradigms Is not Fixed, and Variations Can Be Described along on a Continuum (see Figure 1)

3.3.2. The Concept of a (Dynamic) Continuum of Systemic–Systematic Paradigms in Prevention Research Can Be Conceived as a Repeating Pattern Occurring on Different Scales (i.e., the Case as a Whole and within Cases Explored along Different Dimensions) (Figure 1 and Figure 2)

- The relative proportions of systemic and systematic dimensions play out along a continuum of variable proportions.

- There is potential for movement (up and down via the ladder) between the systemic and systematic dimensions, which results in movement (left to right) along the sliding scale of the continuum. Of note, however, is that position along the continuum can be supported or constrained by contextual factors and what dimensions are included in the assessment.

- The detailed images on the two levels illustrate the descriptive characteristics of the two paradigms (as articulated in the methods Table 1); they do not have deeper meanings other than for illustration.

4. Discussion

- Gain a deeper understanding of the paradigm from which they predominantly work;

- Describe how they are working both systemically and systematically and to what extent (this is important for articulating given our field has called for more systemic approaches to addressing complex problems (see [2]);

- Produce better evidence about the value of systemic and systematic dimensions through the expansion of the boundaries within which these dimensions exist;

- Identify opportunities for how to become more systemic in their practice, especially if this paradigm is lacking beyond the application of systemic theories and methods.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Overview of How Each Case Study Addressed Complexity

| Dimensions | Systemic Paradigm | Systematic Paradigm |

| Case study 1—The healthy and equitable eating (HE2) study responding to complexity | ||

| Overview | Systems thinking was applied throughout this project with an explicit focus within the causal loop diagramming work. There was primarily a focus on explaining and describing complexity as a first step in a longer program of work to create change. The purpose was to create a shared understanding and shared language around addressing nutrition-related inequities and mapping the healthy and equitable eating system. This helped to build a case for the need for intersectoral and whole of government working to address the structural drivers of HE2. | There were systematic approaches applied including recruitment of qualitative interviews, conduct and analysis of interviews. The process of creating the CLDs was systematic, e.g., first drawing individual diagrams, then pair blending, then expanding out to the whole group to create one large diagram. The Prevention Centre required a systematic work plan detailing research aims and timelines. |

| Theory | The Ottawa Charter and the social determinants of health literature was used to underpin this program of work and these frameworks are inherently systemic. While systems theory (namely applied systems and system dynamics) underpinned the diagramming work and was known and understood by the facilitator of this process, and it was the first time it was experienced by the broader team. | Durlak and DuPre’s implementation framework was used to analyse some of the qualitative data in a systematic fashion. |

| Methods | Collaborative conceptual modelling (a systems science method) was used to produce the causal loop diagrams of the drivers of nutrition-related inequities. This systems science methodology enabled a holistic picture of the drivers of inequities in healthy eating to be built and understood. A systemic lens was applied to the range of calls to action relating to the healthy and equitable eating framework. | Systematic semi-structured interviews were used to conduct the research to address the question of the extent to which the whole of government strategy focused upon inequities relating to obesity/nutrition. Systematic approach to creating the healthy and equitable eating framework. |

| Data and evidence | The HE2 diagram was informed by the literature and expert opinion, the HE2 framework was informed by the HE2 diagram and expert opinion, and the interviews were informed by the lived experience of the interviewees. | |

| Relationships | In terms of collaborative relationships, the focus was predominantly on the core research team and those involved in developing the main CLD, which was conducted in a participatory manner, so as to facilitate research–policy collaboration. This worked to create a shared understanding around the drivers of HE2 across multiple domains of influence which could be used by others to advocate for change. I think also the role of an academic, the researcher, is not always been the direct change, direct influencer. But the sort of evidence that we generated through our project gets referred to by others in policy or in other—you know, the Public Health Association of Australia use that. They’ve got strong policy guiding to government. So we might not have a strong voice directly with government, but we’ve got a strong voice into the Public Health Association. So that’s our responsibility to really work that relationship. | Policy and practice partners and stakeholders were chosen in a systematic way based on experience and expertise relating to HE2. |

| Capacity building | The focus on capacity building within the research team and broader stakeholder group was informed by a systemic perspective. | Capacity was built in a number of ways within those involved in this piece of work. For example, those who were yet to be exposed to causal loop diagramming had the opportunity to upskill in this methodology through direct experience, and those less versed in the social determinants of health or systems thinking had the opportunity to deepen their understanding of the many interconnections across the HE2 system driving inequities in healthy eating. |

| Learning orientation | There was a strong learning orientation within the CLD workshops for most of the participants. Much of the learning emerging from this piece of work was around the value of systems science methods for conveying the complexity of addressing inequities in healthy eating. | |

| Multiperspectivity | The participatory approach employed in this piece of work took the CLD diagramming participants along a journey of developing a model of HE2 together which fostered receptivity to the method. There was a recognition of the need for multiple and diverse perspectives to inform this piece of work and build capacity of others to understand different viewpoints. | |

| Knowledge mobilisation/translation | A participatory approach engaged key policy makers from strategic government and NGO partners. | The project developed a number of dissemination products including publications, findings briefs, newsletters, and conference presentations. |

| Case study 2—Food environment policy index (Food-EPI) study addressing complexity | ||

| Overview | The team used systems thinking implicitly. Language around systems thinking or approaches was purposefully avoided in the work because it was perceived as alienating to study participants/partners. The research team was however well versed in systems concepts. In this project, complexity was described as being addressed by working with the food environment policy system, as a whole, and setting up an accountability process to engage stakeholders and influence the way that system works. The Food-EPI work is described as a “cog” within a broader system; the team worked within the boundaries of their remit to seek to influence change through accountability mechanisms. | Application of the Food-EPI rating and benchmarking tool to the food environment policies to monitor and evaluate jurisdictional policies. This was applied in a consistent and standardised way across jurisdictions. The Prevention Centre required a systematic work plan detailing research aims and timelines. |

| Theory | There was an expressed program logic around accountability. | The Food-EPI tool was used as a theoretical framework to rate and benchmark food environment policies, articulating the processes, impacts, and outcomes of public and private sector policies and actions. This in itself provides a systematic theory of change of the components required for effective action to improve population diets, risk factors, and health outcomes. |

| Methods | Those rating the policies comprised multiple perspectives from academics and NGO experts. Policy representatives from state and commonwealth jurisdictions around Australia helped refine some of the priorities and the way information was presented; they did not, however, contribute to the ratings. | The methodological approach involved a formal process of rating and benchmarking policies for comparison purposes, as well as many other purposes such as knowledge sharing and building relationships. |

| Data and evidence | A systemic look across the whole food system was facilitated by the components of the Food-EPI tool developed by INFORMAS: food composition, food labelling, food promotion, food provision, food prices, food retail, leadership, governance, monitoring and intelligence, funding and resources, and support for communities. Data and evidence generated from Food-EPI (benchmarked against best practice internationally) were seen as key for supporting researchers and policy makers to take advantage of policy windows opening in the future. Policy makers were heavily involved in helping collate policy details in order to be assessed. The investigators also consulted with them on best ways to present the findings. They also worked with them on which policies to focus on in the executive summaries of each report. The way the data was collected was systematic in its application of a pre-existing framework. Since the original study was collected, another has been conducted; longitudinal data are required to capture changes in policy over an extended period of time. Note, this type of research could be considered as both systematic and systemic as the work implicitly considers changes over time across a whole system. | |

| Relationships | There was a strong focus on the research team developing collaborative relationships with the study participants involved in the scoring process. Trust building between the researchers and those whose policies were being scored was considered an essential part of this program of work and it was actively fostered. Thus, the importance of relationships was emphasised, especially in working with and across government departments; with a lot of work put into managing relationships via formal and informal means. The influence of the methods used on the relationships between those conducting and participating in the study was explicitly recognised and discussed. | In trying to change the system and because of the intended ‘independent’ nature of the rating and benchmarking activities, the team was working from outside the policymaking “tent”. To maintain objectivity, the research team facilitated the rating and benchmarking process, but the researchers themselves were not participating in the scoring process. This project needed to retain a degree of objectivity and thus distance from the health, education, finance, trade, sport and recreational, etc., systems it was comparing, and thus the work was described as ‘participatory’ as opposed to co-production. Without a focus on co-production, however, the policy stakeholders felt the rating and comparison across jurisdiction was a risky process that they needed to engage in but also manage fallout from potential negative ratings. The research team had very good relationships with the policy participants, but the pre-defined systematic scoring process of the Food-EPI tool created barriers to real co-production and set up a type of power differential between the research team and those who policies were being rated and scored. The team also conducted a very thorough formal evaluation to inform future iterations of the tool and as such made several fundamental changes to the process, in response to feedback received. |

| Capacity building | Within this project there was an emphasis on reflexive learning within the research team and mentoring by a senior team member with a deep understanding of the media, communications, and advocacy to ensure skills were enhanced within the research team to ensure knowledge mobilisation was amplified. Capacity building in this project also deliberately extended beyond just the research team; it was one of the key aims of the project to increase knowledge and build relationships. | - |

| Learning orientation | The research team was very aware of the need to reflect on the pre-determined systematic rating methods of their work as outlined in by Food-EPI—and the degree to which it was influencing or changing policy. It was noted that in future iterations of the program of work, it would be beneficial to shift to a more fair and reliable assessment for the end-users, to improve chances of uptake of the findings of the work and its recommendations. | The project provided jurisdictions with opportunities to learn about the presence, strengths, and limitations of their policies process relative to others. |

| Multiperspectivity | Within the team’s broader program of work as part of Food-EPI, there was an emphasis on bringing in multiple perspectives. For example, in another piece of work there was a commitment to including industry, and thus seeking to understand the perspectives of those involved in industry, which is often over-looked in the prevention research space. The team also had parallel pieces of work exploring the nature of policy processes for obesity prevention at both state and federal levels with a view to understanding levers for change. | |

| Knowledge mobilisation/translation | A keen focus was placed upon who were the key food environmental policy system decision makers and influencers within the system and then ensuring they were provided with the information and support they needed to understand and use the findings. By working closely with stakeholders, the team sought to contribute to real-world problems. | The project developed a number of dissemination products including publications, conference presentations, findings briefs, reports, mixed media coverage, and videos. |

| Case study 3—NSW childhood obesity modelling project addressing complexity | ||

| Overview | The need for this project was identified from within the NSW Ministry of Health. Systems thinking was described as both an implicit and explicit component of this work. Systemic world view was identified as a necessary precondition to working using dynamic simulation modelling. Systems approaches were reported to enable the team to work beyond departmental and sector-based silos. Systems thinking was also reinforced through the modelling process itself, which identified and made explicit the complexity of the interactive variables driving child overweight and obesity in NSW. Participatory model development workshops were structured but allowed to evolve organically. | Evidence reviews and other data were systematically collected and used to inform the model quantification/calculations. The Prevention Centre required a systematic work plan detailing research aims and timelines. |

| Theory | System dynamics theory was used, drawing on the lessons from infectious disease modelling. Other frameworks used were the Ottawa Charter, the social determinants of health, the Foresight obesity diagram, and NSW’s Healthy Eating and Active Living strategy. | |

| Methods | Group model building and dynamic simulation modelling was used, combined with a participatory process to map all relevant variables and quantify them in order to devise solutions to child overweight and obesity. User-friendly interfaces allowed decision makers to have direct contact and interactions with the models, thus allowing them to understand the assumptions underlying the modelling and what it meant. | The project adopted a ‘glass box’ model where relationships and assumptions are made visible, as opposed to a black box in which they are hidden. This explicit visibility was seen as important to account for all aspects of the system that impact on human behaviour and allow them to be accounted for in the modelling. Dynamic simulation modelling brought those aspects to the surface and made them explicit. Other traditional modelling methods, e.g., epidemiology or economics, tend to exclude those variables. |

| Data and evidence | The published literature, and local data, and local real-world experience of those involved were used as evidence in the development of the model, and models were validated based on historical data. The model outputs gave legitimacy to, and provided evidence for, what was already anticipated about the limitations of the existing NSW HEAL policy. It provided a stronger case for expansion of the existing investment and prevention policy program of work. You can’t control whether governments decide to intervene or not in particular areas but we produced the evidence that was needed to argue for the case and that’s what we did. | |

| Relationships | The dynamic simulation modelling was underpinned and led by a participatory approach which fostered the way of working and the strong relationships with decision makers and was reported as key to achieving impact. An organic approach was applied in the workshops for developing the models, allowing important dimensions to emerge, grounded in the experience and preferences of the participants. This process allowed for dialogue and disagreement which provided a level of freedom to diverge, before converging towards agreement and, where possible, degrees of consensus. The process allowed underlying assumptions to be surfaced as part of the participatory process which was a key aspect of the work. Interpersonal skills have been key for carrying out this piece of work, including the ability to be open and receptive to all perspectives and being adamant about bringing them into the work. For example, debate was welcomed when the model was being built so that participants could share all of their information. | |

| Capacity building | Within the unit at the Ministry of Health, there was an emphasis placed upon upskilling people and embedding new capabilities. There was a focus on empowering those involved in building CLD (qualitative system diagrams) to ensure they understood what was going on, key terms, and they learnt technical systems language which was seen as empowering and a way of levelling the playing field. The language and jargon of dynamic simulation modelling was used, but all terms were explained. This was used as a means of empowering people and placing them all on the same playing field. The language of dynamic simulation modelling was interpreted and translated into jargon that is familiar to stakeholders, which may be plain English for lay people, or epidemiological jargon for public health researchers. A contrasting view was shared, however, by another interviewee who explained that they did not adopt new language so as to avoid alienating people. | |

| Learning orientation | Learning was emphasised in this work in relation to the modelling method itself and what it could and could not do. Overall, there was curiosity, interest, and good will in the modelling work which helped with buy-in. People were receptive because their experiences were heard and adjustments were made to the model in accordance with their feedback, leading to a very respectful process. I learned so much, definitely about the modelling side of things, what it can do, what it probably can’t do so well. I’ve learned sort of how something like this politically can give us some really strong representation, like the importance of actually, yeah like embedding, you know, someone but I guess more broadly building capability and capacity. I’ve learned that yeah, like actually the importance of the translator role in making sure that something like this doesn’t just end up sitting on the shelf. The work emphasised and valued deliberative methods, participatory methods, and the importance of developing shared understanding of a system and shared goals in order to leverage change. Creating shared understanding and shared intent were key aspects of the participatory process; the models help to create the shared understanding of problem, communicate the problem, and create shared intent. Collaboration and the participatory process enabled more interventions to be entered into model than would have occurred without the modelling methods. | |

| Multiperspectivity | Policy, practice and content experts contributed different perspectives informing the dialogue and creating the model. So there was the technical experts and there was a core group from the Ministry and the Office of Preventive Health that sort of had oversight or active involvement, for either implementing or evaluating the Premier’s priority, from a Ministry point of view. Then the public workshops were designed to include a whole bunch of content experts and other stakeholders, so that was a much broader group, to seek input and validate the whole process by a series of workshops and involvement with all these different stakeholders. | |

| Knowledge mobilisation/translation | There was focus on the importance, politically, of embedding key stakeholders and decision makers into the process of building a model in a participatory manner. Ensuring there were personnel in translator/boundary spanner roles was a key aspect for supporting the ongoing use of the model. | |

| Case study 4—Hunter New England region program of work addressing complexity | ||

| Overview | The HNE way of working seems to replicate Ray Ison’s systemic and systematic yin yang diagram whereby they have an overarching paradigm of looking at the bigger picture and yet they also work within the details with respect to service delivery and health promotion needs. This program of work is very systemic in its governance and relational aspects, but more systematic in its research design and data collection methods. | |

| Theory | Many of those in leadership roles within the LHD have been exposed to systems thinking in one way or another, formally or informally, but systems theories were not explicitly applied. Complexity was understood and addressed from the viewpoint of sociology and psychology theories, thus providing a deep structural understanding of systems as well as human behaviour. The role of intuition and understanding the local context were highlighted, which was generated through experience in the field. | Other theories used were implementation science theory, RE-AIM, and behaviour change theory. |

| Methods | While the team described the complexity of chronic disease and the nature of interacting variables within the local context, many were not trained in systems science methods and mostly adhered to the study designs and methods of population health epidemiology, and/or qualitative. Theories and methods were chosen to meet the pragmatic goals of answering practical implementable questions. Randomised controlled trials were the main research method used to evaluate intervention effectiveness. The research team identified themselves as trialists, i.e., generating evidence within the EBM paradigm. Context influences impact, but you can only, as a health service control what you can control, and you need to know in that circumstance are these things that I can manipulate worth manipulating. So are they beneficial? So you know, a randomised control trial is actually a really useful and powerful tool to let you do that. | |

| Data and evidence | All data and evidence are generated through high quality RCTs within specific contexts and settings and incorporate qualitative research into process evaluations. However, this case study challenges the binary reductionist view of intervention trials in that RCTs are used to evaluate systems-level interventions, and these interventions themselves are designed taking a systems approach. | |

| Relationships | The research is conducted within and by the health service for the purposes of adaptation and implementation of local service delivery. There was also a lot of focus on generating shared intent, alignment of values, and consideration of co-benefits as a way of working together when values or priorities did not align. Because of the focus on addressing the needs of those they sought to help through their health service-based work, the use of language was tailored to the needs of end-users to ensure clear communications. | |

| Capacity building | There was a strong focus on building capacity across the health service and this was reflected through the governance arrangements which allowed, for example, those with research training to also manage health services. Those working within the health service had the opportunity to rotate around roles and upskill across a number of areas. | |

| Learning orientation | There was strong emphasis of the importance of adaptation within the work so that while there are key principles that they work to, it is essential that they avoid getting bogged down in rigidly adhering to any one method, framework, or theory. There was a recognition that systems can be unpredictable and thus no trial or program of work will always go smoothly. There were examples of reflection and ongoing active learning through the more formalised continual quality improvement processes built into the way they work. Cycles of learning involved testing, reflecting, learning, implementing, and testing again. | |

| Multiperspectivity | Within the team, there is a strong focus on deep listening, compassion, and understanding the system in which they work. There is a high level of engagement with those who work in the system, and an emphasis on listening to their points of view, issues, concerns, and pressures and then picking out the ‘gems’ that are going to point the way to the solution. There was also an awareness of and engagement with the multiple perspectives of those involved in the work which include, for example, NGOs and industry; from this, there is attention paid to understanding what co-benefits can emerge from various pieces of work. | |

| Knowledge mobilisation/translation | They use an embedded systems approach facilitated through governance structures to create the right environment for co-production to occur. This means that the system is receptive and able to incorporate the changes that the research identifies as needed. There is an emphasis on rigour in the research methods, but the framing of the questions is always focused on the end user. One of the good things about working in the organisation that I am is that you have to move past the theorising and into the practical really quickly, and unless the theory becomes practical from a service perspective, then there is actually not a lot of value in it for practitioners. Impact is thus achieved through the organisational structure whereby dual roles are held so that researchers are also practitioners, coupled with the co-location of practitioners and researchers within the health service teams. As a result, there are minimal difficulties with translation of research for the purposes of generating impact because the evidence is generated locally for the purpose of answering questions that the service needs to answer. The service is often thought of synonymously with intervention so we, and research and service is also it’s hard to distinguish at times because the research process is so ingrained with the service delivery and quality improvement process of the health promotion unit that we are working in. Guiding principles for effective research translation and creating change, are derived locally as from the evidence of systematic reviews. Four key principles that are used include the following: understand the system in which you are seeking change, ensure appropriate training, implement performance monitoring and feedback, and obtain support from leaders within the system. | |

| Case study 5—Liveability program of work addressing complexity | ||

| Overview | The liveability team explicitly used the language of complex adaptive systems, and aimed to develop a thorough understanding of the planning and transport systems that they were working with, and the interdependent nature of their dimensions.They have a multidisciplinary team with complementary skills (e.g., relational, data analysists, economists, GIS and other modelling). Within the team, members adopt different roles in terms of both big picture thinking and focused analysis of the finer details. You keep adding colour, but when you step back you can actually see that there is a picture there that there is actually something to be seen. So, if you look at Monet’s Gardens, it just looks like splotches of colour, but then if you stand back, then you realise it’s a bridge with lily pads. So, I think our research is a bit like that. Every time we do something, we’re adding a dob of colour and it just gives clarity to the picture but only when you stand back because our work is meant to be more strategic and more of a higher level, it’s meant to draw attention to the problem, at which point you start to dig in a lot deeper to say, well. | The work focused on careful and rigorous identification, development, testing, and evaluation of liveability indicators across a broad range of domains. These were developed for applied planning policy and practice contexts. The Prevention Centre required a systematic work plan detailing research aims and timelines. |

| Theory | The Ottawa Charter and Social Determinants of Health frameworks strongly informed this work, encouraging a big picture, sociological, and structural world view. | Diffusion of innovation theory was applied to the work with the goal to targets key innovators and those who support change among the decision makers and influencers. The Results-Based Accountability Framework, which relies on using data for continuous learning and improvement, was also used; this can, however, also be considered systemic in nature given its focus on continuous learning. |

| Methods | Over time, the team has incorporated the use of systems science modelling methods to complement their use of natural experiments. | Rigorous identification, development, benchmarking, testing, monitoring, and evaluation of liveability indicators. |

| Data and evidence | There were strong focuses on both data and evidence in combination with politics, structure, power, or influence. Qualitative information gained from relational interactions and informal discussions with decision makers was valued as an important source of knowledge to inform and guide the program of research. Data mapping methods and quantitative agent-based modelling were used to further explore and understand complexity. | |

| Relationships | Much of the working relationships are longstanding, having been nurtured through this program of work over an extended period of time. As such, the research team has a deep and intimate understanding of the policy makers’ worldviews, problems, and ways of working which has served to build up high levels of trust resulting in several working partnerships. The close partnerships built up between policy and research actors served as a relational form of embedding the work within the system it was seeking to influence. A jargon-free and thus accessible shared language was an important dimension of the liveability work. This linked into the need to build strong relationships and engage in a meaningful way with key stakeholders by refraining from highly academic language that would have served to alienate and create power differentials. So, in our project, you could think of it as two fuzzy spots, the edges of the circles are not closed at all and are very open to what the other is trying to teach us so that we can create something that’s joint and in partnership, so together, not a collaborator, someone who sits next to you, but someone who is literally holding your hand, a partner. So, it’s quite—that language, I think, for us is quite strong. Partner is the word that we’re using, we’re conscious of using that word, it’s not in collaboration with, they’re not sitting next to us, they’re actually, you know, it’s much more, forgive the word but intimate, it’s meant to be. | |

| Capacity building | A key aspect of this work was building capacity in partners outside the health sector to draw on and use the available evidence and identify the gaps in knowledge. | Capacity building was achieved through understanding policy concerns, educating people to be able to ask questions that could be answered through empirical research; and helping them to reframe their questions to address the gaps in the evidence from the liveability research. |

| Learning orientation | Within the body of work there was a strong focus on quality improvement within the team itself, and well as an externally focused learning orientation. This was facilitated by reflection at the end of each project to see what worked well, what did not, and to learn from these reflections. Partners were asked what their needs were and whether these had been met within their policy and practice context. | |

| Multiperspectivity | The research program has a strong focus on responding to the priorities and needs of sectors outside of health. Thus, while focused on health impacts, many key stakeholder relationships are based outside the Department of Health and relationships have been fostered with partners in the Department of Transport and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. Shared intent was fostered using framing around co-benefits across sectors whereby health was considered an integral part of the value equation when it comes to producing societal benefits through environmental changes. If you’re looking at the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, again it’s sort of planning focus, it’s not focussing on health per se but what we’re now finding is that there’s a greater recognition that the conduit for great change comes from the valuing of things more holistically, so understanding societal benefit, health benefit, benefits that comes from intangibles. What happens in terms of the environment, so environmental sustainability as a benefit? Looking at using sustainable development goals as a way of measuring the true impact that comes from making decisions that are related to planning and infrastructure. So, I think, that the assumption might be and I don’t know if it’s really an assumption, but in the past it’s let’s just ignore health or we assume that health is taking care of itself but actually that’s not how it works at all, we have to, that first step is to assume that health is part of that value equation and you need to factor it in and you need to create systems that help to measure it. | |

| Knowledge mobilisation/translation | The work is highly embedded in strong working relationships with policy partners outside the health sector. Relationship building, as well as formal knowledge generation and evidence, were key to understanding the complexity inherent in the system. These were key dimensions in the change-making process because they were generated as part of a close partnership approach in which researchers and decision makers worked together. Much time was spent listening to policy partners, understanding their needs, and then working alongside them to help address their goals. This served to meet both research and change making agendas, by providing practical solutions for policy partners. Through an embedded research partnership, all parties work to achieve their goals relating to changing non-health systems as a way of improving health. This represents a win-win partnership. But it’s like a developer, you know, what they want to do is maximise profit, but what researchers want to do is maximise good evidence and that translation of evidence into practice. So, we’re all coming at it, from a different angle in the sense that we don’t actually have shared objectives at all, we have different things that we’re responsible for and different things that we want to get out of our project. But there is a bit like a Venn diagram, if you draw the circles of what everyone is trying to do, yes, they have their own objectives but they also have a point where they cross over and for me that knowledge translation space is that bit where we’re acknowledging that we are in partnership together, we’re in this together and we cross over somewhere and it’s just about finding, you know, how strong that crossover is and whether we’re just touching each other on our circles or whether it’s a bit crossover. | Benchmarking and monitoring indicators for liveability were helpful for describing a system, but also for fostering change though establishing methods for greater accountability and by allowing actors within the system to observe how liveability indicators changed over time. |

| Case study 6—Community-based childhood obesity strategies case study addressing complexity | ||

| Overview | This work embodies three dimensions in responding to complexity, i.e., the understanding, addressing, and communicating of complexity are key within this body of work. Understanding relates to describing systems in a way that fundamentally embodies a systems approach and relates to the features of a complex adaptive system. Addressing relates to creating change within systems (whereas a focus on program implementation and fidelity, while ignoring context and the need to adapt, was given as an example of not adequately addressing complexity). Communicating relates to the need to speak the language of those communities that research teams are working within to help understand complexity or create change. | |

| Theory | System dynamics is the predominant theoretical lens through which this program of work is conducted. Other theories from the broad systems science field are also known (e.g., Cynefin). | |

| Methods | The team is very explicitly applying systems science methods to the diagnosis of systems and their readiness for change. Systems approaches are also applied to planning and implementation of local community-based interventions. Social network analysis, agent-based modelling, group model building, and dynamic simulation modelling are the main methods used. AI is also being explored. STICK-E software has been developed to meet the needs of the researchers and communities. | The systemic CLD group model building workshops had systematic, clearly defined, and articulated guidelines, rules, governance mechanisms, and strictly applied scripts to guide facilitation. RCT designs are used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. |

| Data and evidence | Data and evidence are used to create rigour around the process of using systems science methods. Evaluations are supported by traditional methods such as RCTs for generating evidence of intervention effectiveness. The use of RCT designs also assists this type of work getting published in mainstream public health journals. Data and evidence are co-created between researchers and community members in real time using the causal loop diagram methods and implemented through visualisations using the STICK-E software. | |

| Relationships | Strong relationships based on trust were key to the success of the work within communities. Participatory approaches were key to helping people understand complexity and then act to address it. In terms of informal feedback, this is received from communities and stakeholders based on strong trusting relationships. In terms of formal feedback, there is a process of leaving the building and sitting in a circle where the least experienced researcher speaks first to break down power differences. Formal processes also include feedback from communities, with those who are recently recruited and those who are well experienced, and, in the middle, those who are currently working on a project, thus building the networks and relationships between those communities. Power structures are broken down between research team members and those working within the community, and within the communities themselves. Sometimes communities then continue to apply what they have learnt to new problems and concerns (e.g., COVID-19 response). | |

| Capacity building | Communities are empowered by giving them the direct experience of understanding, addressing, and communicating complexity for the first time. The right tools are provided to the right people at the right time. Communities are enabled to learn skills and develop relationships and networks to then progress to addressing their local problems for themselves, while the GLOBE team provides ongoing backup and support. Shared language was a key feature as part of this work and one of the three pillars for creating change, namely, communicating complexity. | |

| Learning orientation | Formal and informal mechanisms for reflection and feedback were a key part of this research group’s practice. This applied to the research process itself where community participants were empowered to share their hopes, fears, and feedback (i.e., group model building process), as well as formal internal research team-focused reflection sessions. The feedback sessions were aimed at addressing power imbalanced systemic through a formal systematic process. ( The goal is systemic, but the process is systematic.) There’s huge amounts of informal feedback that’s built on relationships where in all of our major trials, I can think of probably across 10 different countries where this happens—the key community person in any one of those communities can ring me on my mobile any time and say we just had one of your crew present such and such, and it went over like a lead balloon, what are we going to do? Or “We just ran a session and they got really excited—what do we do next?” Or “That was okay, but this bit sucked.” Or “Was surprised you didn’t mention the Mayor, because the Mayor was in the room. You better do something about that.” So there’s a whole bunch of informal relationship-based feedback which is more powerful even I think than the other sought. And it’s a pretty basic process, but it’s just good drills, right...There’s little things like you never discuss the session until you’re out of the building and just little things like that, that don’t seem to mean anything… You need someone to be able to say, all right. Well, we’re going to do feedback. We’re going to sit in a circle and do it and we’re going do it from the youngest to oldest, or from least experience and this is the framing of the feedback. This is how we’re going to use it, and we’re going to wait until we know that the room is empty before we start. We’d also have in that group of people, the sponsors for that local community, so we’re immediately building a network of people that are last community, next community, this community. And the idea, because I’m probably most experienced in most things, I don’t have to say anything—it deliberately builds relationships between them. Because, they’re, “This really sucked.” And the last community says, “Yeah, that happened to us too, but stick with it, it will be all right.” Or, “Yeah, we overcame that,” or the Captain of the golf club looked really grumpy. You’re going to have to call them separately, this is what we did, or whatever it is. | |

| Multiperspectivity | The GMB process is strategic in recruiting local community leaders, those who can take action, and those who are able to provide lived experience to inform the development of the models. Because of the emphasis on empowerment and capacity building, as well as the way the GMB workshops were run, there had to be a keen focus on listening in order to work collectively with communities to understanding and address problems. There is an explicit consideration of whose voice is included, and why/why not, and how to address power imbalances to ensure that multiple perspectives are heard. | |

| Knowledge mobilisation/translation | Understanding complexity in public health is seen as a strategic step in addressing it, i.e., creating change. Understanding complexity can only happen if systems thinking is made accessible via avenues such as language, participatory approaches, and user-friendly software (e.g., STICKE). Communities must be empowered to understand and then create their own changes. Thus, there is a strong focus on communicating complexity to those with the power to enable the work to happen. | |

References

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez Roux, A.V. Complex systems thinking and current impasses in health disparities research. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salway, S.; Green, J. Towards a critical complex systems approach to public health. Crit. Public Health 2017, 27, 523–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G. Systemic Intervention for Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leischow, S.J.; Milstein, B. Systems Thinking and Modeling for Public Health Practice. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 403–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, S.; Millar, L.; Hovmand, P.; Bell, C.; Moodie, M.; Carter, R.; Swinburn, B.; Strugnell, C.; Lowe, J.; de la Haye, K.; et al. Whole of systems trial of prevention strategies for childhood obesity: WHO STOPS childhood obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hertog, K.; Busch, V. The Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach: A whole systems approach for tackling child obesity in cities. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30 (Suppl. 5), ckaa165-516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leykum, L.K.; Pugh, J.; Lawrence, V.; Parchman, M.; Noël, P.H.; Cornell, J.; McDaniel, R.R. Organizational interventions employing principles of complexity science have improved outcomes for patients with Type II diabetes. Implement. Sci. 2007, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, G.; Malbon, E.; Carey, N.; Joyce, A.; Crammond, B.; Carey, A. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: A systematic review of the field. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, S.; Pescud, M.; Malbon, E.; Lee, A.; Carter, R.; Greenfield, J.; Cobcroft, M.; Potter, J.; Rychetnik, L.; Meertens, B. Using systems science to understand the determinants of inequities in healthy eating. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavoa, S.; Boulangé, C.; Eagleson, S.; Stewart, J.; Badland, H.M.; Giles-Corti, B. Identifying appropriate land-use mix measures for use in a national walkability index. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11, 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevijvere, S.; Barquera, S.; Caceres, G.; Corvalan, C.; Karupaiah, T.; Kroker-Lobos, M.F.; L’Abbé, M.; Ng, S.H.; Phulkerd, S.; Ramirez-Zea, M.; et al. An 11-country study to benchmark the implementation of recommended nutrition policies by national governments using the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index, 2015–2018. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, S.; Brown, A.D.; Bolton, K.A.; Fraser, P.; Lowe, J.; Hovmand, P. Translating systems thinking into practice for community action on childhood obesity. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevention Centre. The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre website. Available online: https://preventioncentre.org.au (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Ison, R.; Straw, E. The Hidden Power of Systems Thinking: Governance in a Climate Emergency; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, A.; Rowbotham, S.; Grunseit, A.; Bohn-Goldbaum, E.; Slaytor, E.; Wilson, A.; Lee, K.; Davidson, S.; Wutzke, S. Knowledge mobilisation in practice: An evaluation of the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaytor, E.; Wilson, A.; Rowbotham, S.; Signy, H.; Burgess, A.; Wutzke, S. Partnering to prevent chronic disease: Reflections and achievements from The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Public Health Res. Pr. 2018, 28, e2831821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutske, S.; Redman, S.; Bauman, A.; Hawe, P.; Shiell, A.; Thackway, S.; Wilson, A. A new model of collaborative research: Experiences from one of Australia’s NHMRC Partnership Centres for Better Health. Public Health Res. Pr. 2017, 27, e2711706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutzke, S.; Rowbotham, S.; Haynes, A.; Hawe, P.; Kelly, P.; Redman, S.; Davidson, S.; Stephenson, J.; Overs, M.; Wilson, A. Knowledge mobilisation for chronic disease prevention: The case of the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescud, M.; Rychetnik, L.; Allender, S.; Irving, M.J.; Finegood, D.T.; Riley, T.; Ison, R.; Rutter, H.; Friel, S. From Understanding to Impactful Action: Systems Thinking for Systems Change in Chronic Disease Prevention Research. Systems 2021, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.; Van de Bunt, G.G.; De Bruijn, J. Comparative research: Persistent problems and promising solutions. Int. Sociol. 2006, 21, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Nowell, B.; Yang, H. Putting the system back into systems change: A framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Watson, E.R. The ABLe Change Framework: A Conceptual and Methodological Tool for Promoting Systems Change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 49, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, L.M.; Matteson, C.L.; Finegood, D.T. Systems Science and Obesity Policy: A Novel Framework for Analyzing and Rethinking Population-Level Planning. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovmand, P.S. Group model building and community-based system dynamics process. In Community Based System Dynamics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tharenou, P.; Donohue, R.; Cooper, B. Management Research Methods; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Partnership Centre. Healthy Public Policy to Support Healthy and Equitable Eating. Available online: https://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/healthy-public-policy-to-support-healthy-and-equitable-eating/ (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Newell, B.; Proust, K.; Dyball, R.; McManus, P. Seeing obesity as a systems problem. New South Wales Public Health Bull. 2007, 18, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partnership Centre. Benchmarking Obesity Policies in Australia. Available online: https://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/benchmarking-obesity-policies-in-australia/ (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Partnership Centre. Partnering to Develop a Decision Tool to Reduce Childhood Overweight and Obesity. Available online: https://preventioncentre.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/1702_FB_ATKINSON_PremObesity.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Wolfenden, L. You’ve Heard of Clinician Scientists. We’re Applying the Same Model to Public Health. Prevention Centre Blog. Available online: https://preventioncentre.org.au/blog/youve-heard-of-clinician-scientists-were-applying-the-same-model-to-public-health/ (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Partnership Centre. Creating Liveable and Healthy Communities. 2021. Available online: https://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/creating-liveable-and-healthy-communities/ (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Global Obesity Centre. Community Based Systems Interventions. Available online: https://iht.deakin.edu.au/global-centre-for-preventive-health-and-nutrition/stream/community-collaboration/ (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Hayward, J.; Morton, S.; Johnstone, M.; Creighton, D.; Allender, S. Tools and analytic techniques to synthesise community knowledge in CBPR using computer-mediated participatory system modelling. Npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Papoutsi, C. Studying complexity in health services research: Desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, S.A.; Finegood, D.T.; Roux, A.D.; Rutter, H.; Clarkson, J.; Frank, J.; Roos, N.; Bonell, C.; Michie, S.; Hawe, P. Systems-based approaches in public health: Where next? Acad. Med. Sci. 2021. Available online: https://researchportal.bath.ac.uk/en/publications/systems-based-approaches-in-public-health-where-next (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Rutter, H.; Savona, N.; Glonti, K.; Bibby, J.; Cummins, S.; Finegood, D.T.; Greaves, F.; Harper, L.; Hawe, P.; Moore, L.; et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 2017, 390, 2602–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, E.; Marks, D.; Er, V.; Penney, T.; Petticrew, M.; Egan, M. Qualitative process evaluation from a complex systems perspective: A systematic review and framework for public health evaluators. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; WH Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Irving, M.J.; Pescud, M.; Howse, E.; Haynes, A.; Rychetnik, L. Developing a ‘systems thinking’ guide for enhancing knowledge mobilisation in prevention research. Public Health Res. Pract. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.; Sankaran, S.; Haslett, T. Systems thinking: Taming complexity in project management. Horizon 2012, 20, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Recruitment | Case selection |

| Selected a convenience sample of known chronic disease prevention projects that addressed complexity on a range of prevention research topics and study designs. | |

Data collection | Conducted qualitative semi-structured interviews using two-part interview schedule, plus analysis of case study documents available online |

| Interview 1 explored the background, context, and purpose of the work in each case study, while Interview 2 explored further details of working with complexity and the role of systems approaches. Questions informed by Foster-Fishman et al. [22]. | |

Data analysis | Developed codes and categories with analysis combined with deductive and inductive processes |

| Open coding analysis in Word using the comments function and memo writing; drew on systems literatures to inform theoretical sensitivity, and inductive methodology informed by grounded theory for empirically derived concepts. Structured framework analysis used to develop higher order categories and their relationships. Data managed in Google sheets. All categories further explored in relation to the core social process of ‘addressing complexity’ as identified in the research question. | |

| Explored the operationalisation of systems approaches within each case study | |

| Described elements of systems approaches for addressing complexity within each case study articulated across a range of dimensions. The dimensions were derived from the framework analysis above. These identified explicit uses of systems science, methods, and tools, plus examples of implicit systemic approaches. Analysis explored how these were operationalised. Identified systematic methods embedded in systemic work, and systemic approaches incorporated into systematic work; described how these relationships played out in varying forms and proportions. | |

| Incorporated the systematic paradigm to represent the whole (Ison and Straw [15]) | |

| Comparative descriptive synthesis conducted for each case study to identify how systemic and systematic aspects were operationalised within the core dimensions. Building on Ison and Straw’s [15] work contrasting systemic and systematic paradigms, further analysis explored their relational properties as a continuum with variable proportions. Key considerations:

| |

| Reflexive practice | |

| The core team on this project were LR and MP; LR was also the Co-Director of the Prevention Centre and MP a Senior Research Fellow supported through the Centre at the Australian National University (ANU). Throughout the project, our analysis, interpretations, and writing were also guided by our co-authors in conversations (in person and virtually) and via feedback on working documents and draft manuscripts. We convened bi-monthly Chief Investigator meetings (SA, SF, MJI); and a quarterly Systems Advisory Group (RI, DTF, TR, HR). Our data collection and analysis were also informed through wider reading of the systems literature, but particularly the following: [8,15,22,23,24,25]. The study was conducted in the context of a Prevention Centre project, itself conceived as reflexive practice (i.e., to explore what can be learned from research case studies affiliated with the Centre that seek to address the complexity of chronic disease prevention). We acknowledge that our data and interpretations are partly formed by our research question and study design; our team’s worldviews, assumptions, and beliefs; and the overall goals of the Prevention Centre. We have, however, sought to provide an explicit audit trail to maximise the replicability of our methods, and propose that the concepts and theory emerging from our analysis will likely hold true for many examples of prevention research seeking address complexity. | |

| Systemic | Systematic |

|---|---|

| A focus on details; Methodical; Examining the parts within a system; A more linear focus; Duality (black and white, night and day, inhale and exhale, yin and yang, etc.); Randomised controlled trials and cluster randomised controlled trials; “What intervention works?”; A focus on fidelity in program delivery. |

| Case Study 1—The Healthy and Equitable Eating (HE2) Study Case Study | |

|---|---|

| Data | Two interviewees, two interviews each |

| Study link | https://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/healthy-public-policy-to-support-healthy-and-equitable-eating/ (accessed on 26 April 2023). |

| Focus | Structural/policy level |

| Project | Discrete project |

| Academic/Policy/Practice | Academic-led with policy focus genesis, academic-led and policy research implementation |

| The study: what happened? | The team explored what is required to create a healthy and equitable system of eating in Australia. A key piece of work was a causal loop diagram developed as a collaborative effort between academics and policy makers, and depicting the drivers of inequities in healthy-eating-spanning domains—including housing and the built environment, health literacy, transport, employment, food supply and environment, food taste preferences, and social protection. A systems-based policy framework was also developed suggesting plausible policy actions that could be implemented across each of the domains. An additional piece of work used an existing Australian policy case study to explore the potential value of public policy attention given to inequities in obesity. |

| Rationale | When working to address the complex problem that is addressing inequities in healthy eating, a typical response has been to oversimplify both the problem and the solution instead of paying attention to the multiple interacting variables affecting the consumption of a healthy diet across social groups. Evidence was required to guide coherent policy development and implementation spanning a broad range of policy areas which affect nutrition-related inequities. |

| Outcome | An evidence base was produced showing what can be done to improve healthy and equitable eating (HE2) in Australia via federal and state cross-government policies and programs. |

| Case study 2—Food environment policy index (Food-EPI) study case study | |

| Data | Four interviewees, two interviews with two participants and one paired interview where only one interview was conducted |

| Study link | https://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/benchmarking-obesity-policies-in-australia/ (accessed on 26 April 2023). |

| Focus | Structural/policy level |

| Project | Program of work |

| Academic/Policy/Practice | Academic-led with policy focus genesis, academic-led and policy research implementation, for public policy advocacy |

| The study: what happened? | The Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI) was developed by INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/NCDs Research, Monitoring and Action Support) to assess government policy across 14 areas for action in relation to food environments. This approach was replicated and applied in this Australian case study in which diet-related aspects of obesity prevention policies at state, territory, and federal level were assessed and compared to international best practice. There was extensive engagement between researchers and policy makers, including in the extensive process of collating government policy data, verifying it, and reviewing and prioritising recommendations. Government also had input into the way in which results were presented as part of final reports. An important goal of the project was to increase accountability of governments around obesity prevention. The ratings were conducted in workshops engaging all of the participating policy agencies. |

| Rationale | While it is recognised that in order to address obesity a comprehensive approach is required, the development and implementation of recommended policies has not moved quickly within Australia and elsewhere. Australia’s performance when it comes to obesity prevention had not been systematically benchmarked and monitored. The study design was also informed by former successful campaigns establishing competition and accountability, i.e., the Dirty Ashtray and Couch Potato Awards benchmarking the States and Territories against best practice and each other. |

| Outcome | An assessment was made as to the degree to which policies in Australian met best practice for creating healthy food environments and priority areas for action to improve food environments were identified. The findings were published in and published in public reports. |

| Case study 3—NSW childhood obesity modelling project addressing complexity | |

| Data | Five interviewees, two interviews each |

| Study link | https://preventioncentre.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/1702_FB_ATKINSON_PremObesity.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2023). |

| Focus | Structural/policy level |

| Project | Discrete project, but it has produced spin-off projects |

| Academic/Policy/Practice | Primarily policy-led genesis, academic-led and policy research implementation, for local policy decision making |

| The study: what happened? | In NSW, as part of the Premier’s Priorities, the Ministry of Health approached the Prevention Centre to test how different interventions and combinations of interventions could help achieve a 5% reduction in child overweight and obesity over a 10-year period. A dynamic simulation model was used to provide insights into what combination of interventions would be required to meet the target. |

| Rationale | When it comes to addressing overweight and obesity in Australian children, population-level interventions that create sustained change have been lacking. The impact of these interventions being implemented simultaneously has also been unclear. |

| Outcome | A participatory approach was employed to build and test the model. This engaged multiple stakeholders central to decision making in relation to addressing overnight and obesity in NSW children. The combination of interventions required to meet the target included actions to improve the built environment, food policy interventions, school and childcare interventions, and clinical service delivery. |

| Case study 4—Hunter New England region program of work addressing complexity | |

| Data | Three interviewees, two interviews each |

| Study link | https://preventioncentre.org.au/blog/youve-heard-of-clinician-scientists-were-applying-the-same-model-to-public-health/ (accessed on 26 April 2023). |

| Timeframe | Ongoing |

| Focus | Structural/policy/community level |

| Project | Program of work |

| Academic/Policy/Practice | Practice-based genesis, practice-led and academic research implementation, for quality improvement of service delivery |

| The study: what happened? | This case relates to the research–practice partnership set up between Hunter New England Population Health (a population health service delivery unit in Australia) and the University of Newcastle and was included as a case study of an embedded model for prevention and health services research. A single-integrated governance structure means that researchers are embedded within the health service delivery unit. Senior leadership roles are filled by staff holding appointments at both the health service and university. |

| Rationale | Health research is much more likely to be used if the research questions are derived from the proximal service delivery needs of the end users. |

| Outcome | Research and service delivery work is co-conceived, co-designed, co-evaluated, and co-disseminated by both practitioners and researchers. This optimises research co-production via greater knowledge exchange and alignment of research with the needs of the health service. Thus, research and evaluation findings are readily available to end users. Both academic and health service resources are simultaneously leveraged to meet scientific and service delivery goals. |

| Case study 5—Liveability program of work addressing complexity | |

| Data | Two interviewees, two interviews each |

| Study links | https://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/creating-liveable-and-healthy-communities/ (accessed on 24 June 2023). https://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/developing-the-tools-to-map-and-measure-urban-liveability-across-australia/ (accessed on 26 April 2023). https://preventioncentre.org.au/our-work/research-projects/benchmarking-monitoring-modelling-and-valuing-the-healthy-liveable-city/ (accessed on 26 April 2023). |

| Focus | Structural/policy level |

| Project | Program of work |

| Academic/Policy/Practice | Academic-led with policy focus genesis, academic and policy-led research implementation, for public policy decision making and system change |

| The study: what happened? | A range of policies related to the liveability domains have been validated to provide evidence for how they contribute to chronic disease risk factors. These have also been benchmarked and are being monitored to track the progress of communities towards healthier and more equitable living. Furthermore, agent-based modelling is being used to explore the efficacy and economic benefits of possible interventions relating to the indicators to improve walking, cycling, and public and private transport usage. |

| Rationale | Eleven domains of liveability have been identified by Billie Giles-Corti’s research team relating to the social determinants of health. Neighbourhoods have huge impacts on many aspects of health and wellbeing. |

| Outcome | The liveability indicators are being used by a range of stakeholders to inform the creation of healthier built environments. |

| Case study 6—Community-based childhood obesity strategies case study addressing complexity | |

| Data | One interviewee, two interviews |

| Study link | https://iht.deakin.edu.au/global-centre-for-preventive-health-and-nutrition/stream/community-collaboration/ (accessed on 26 April 2023). |

| Focus | Community level |

| Project | Discrete projects across many communities as part of broad program of work |

| Academic/Policy/Practice | Academic-led with community focus genesis, community-led and academic research implementation, for local community action |

| The study: what happened? | Informed by system dynamics theory, communities are empowered to create informal maps as well as contribute to formal simulation models to understand, address, and communicate dynamic complexity. Systems science methods including Agent Based modelling, System Dynamics, Social Network Analysis and Causal Loop Diagrams are used in this program of work spanning numerous and diverse communities in Australia and internationally. |

| Rationale | Successful population-level interventions for addressing child obesity and other non-communicable diseases require a shared understanding of the systemic drivers of these problems and an understanding of how to strengthen existing systems to promote good health and reduce disease burden. The ability of communities to apply systems thinking is crucial to the success of such interventions. |

| Outcome | Capacity is built within communities and communities are empowered to solve their problems as a collective and engage in sustainable change. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pescud, M.; Rychetnik, L.; Friel, S.; Irving, M.J.; Riley, T.; Finegood, D.T.; Rutter, H.; Ison, R.; Allender, S. Addressing Complexity in Chronic Disease Prevention Research. Systems 2023, 11, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070332

Pescud M, Rychetnik L, Friel S, Irving MJ, Riley T, Finegood DT, Rutter H, Ison R, Allender S. Addressing Complexity in Chronic Disease Prevention Research. Systems. 2023; 11(7):332. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070332

Chicago/Turabian StylePescud, Melanie, Lucie Rychetnik, Sharon Friel, Michelle J. Irving, Therese Riley, Diane T. Finegood, Harry Rutter, Ray Ison, and Steven Allender. 2023. "Addressing Complexity in Chronic Disease Prevention Research" Systems 11, no. 7: 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070332

APA StylePescud, M., Rychetnik, L., Friel, S., Irving, M. J., Riley, T., Finegood, D. T., Rutter, H., Ison, R., & Allender, S. (2023). Addressing Complexity in Chronic Disease Prevention Research. Systems, 11(7), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070332