Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the factors that influence vaccination options, including vaccination against COVID-19, in order to develop a management algorithm for decision-makers to reduce vaccination reluctance. This paper’s primary objective is to empirically determine the relationships between different variables that correlate to non-vaccination behavior of the target population, as well as the implications for public health and situational management strategies for future vaccination intentions. We created a questionnaire to investigate the personal approach to disease prevention measures in general and vaccination in particular. Using SmartPLS, load factors for developing an algorithm to manage vaccination reluctance were calculated. The results shows that the vaccination status of an individual is determined by their vaccine knowledge. The evaluation of the vaccine itself influences the choice not to vaccinate. There is a connection between external factors influencing the decision not to vaccinate and the clients’ motives. This plays a substantial part in the decision of individuals not to protect themselves by vaccination. External variables on the decision not to vaccinate correlate with agreement/disagreement on COVID-19 immunization, but there is no correlation between online activity and outside influences on vaccination refusal or on vaccine opinion in general.

1. Introduction

In the absence of a specific treatment for SARS-CoV-2 infections, preventing COVID-19 infection has become a top priority. Initially, prevention consisted of non-pharmacological measures [1] suggested by the World Health Organization and adopted by each state through normative acts. In Europe, the European Medicines Agency authorized the use of a vaccine only 10months after the announcement of the pandemic, followed shortly after by three other vaccines. One year after the start of the vaccination campaign, the full-scheme vaccination coverage in many European countries did not meet the targets set by the authorities. This finding coincides with low population confidence in the quality of medical services and a general unwillingness to vaccinate. Vaccination reluctance is not a new phenomenon [2,3], but it has recently been identified as one of the greatest threats to public health [4]. In the context of a pandemic, hesitancy regarding COVID-19 vaccination has been observed globally, and there are numerous studies [5,6] investigating factors that influence vaccination options [7], but they do not address the general population, but rather specific populations [8,9] or professional categories. Moreover, our study supplements the information on the option to vaccinate [10] and confidence in the measures ordered by the authorities, and deployed through the health system, during the pandemic [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

This study aims to examine the factors that influence, in Romania, the options available for the COVID-19 vaccine, as well as the prophylactic measures chosen by the general population and by average healthcare professionals. In designing this research, we assumed that reluctance to vaccination is caused by factors related to the vaccine (doubt about its safety, quality, or efficacy) on the one hand, and that reluctance is influenced and fed by media information, opinion leaders, and acquaintances on the other hand. To investigate these factors, a questionnaire was administered online, as well as via letter support, to adults from all over the nation, both rural and urban.

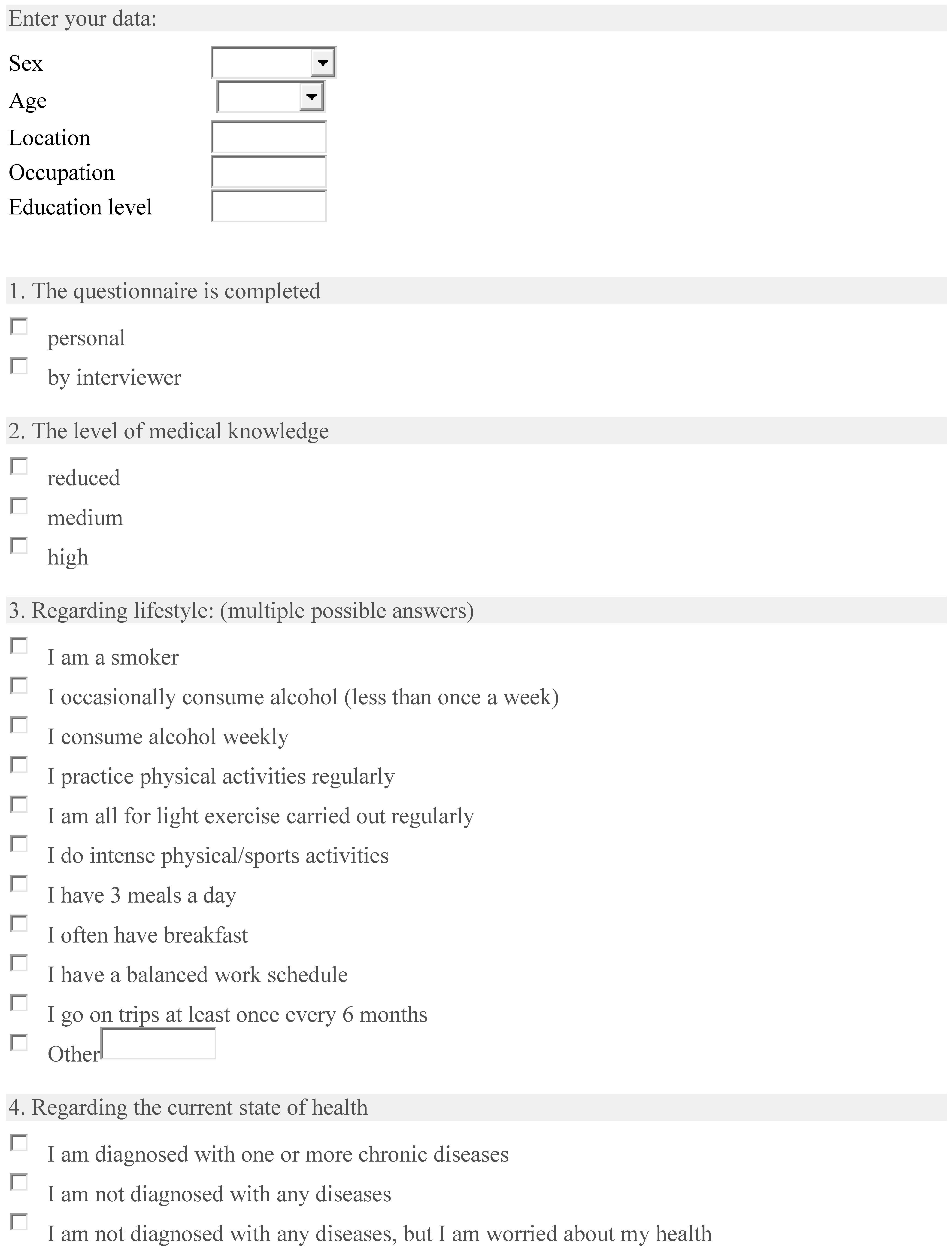

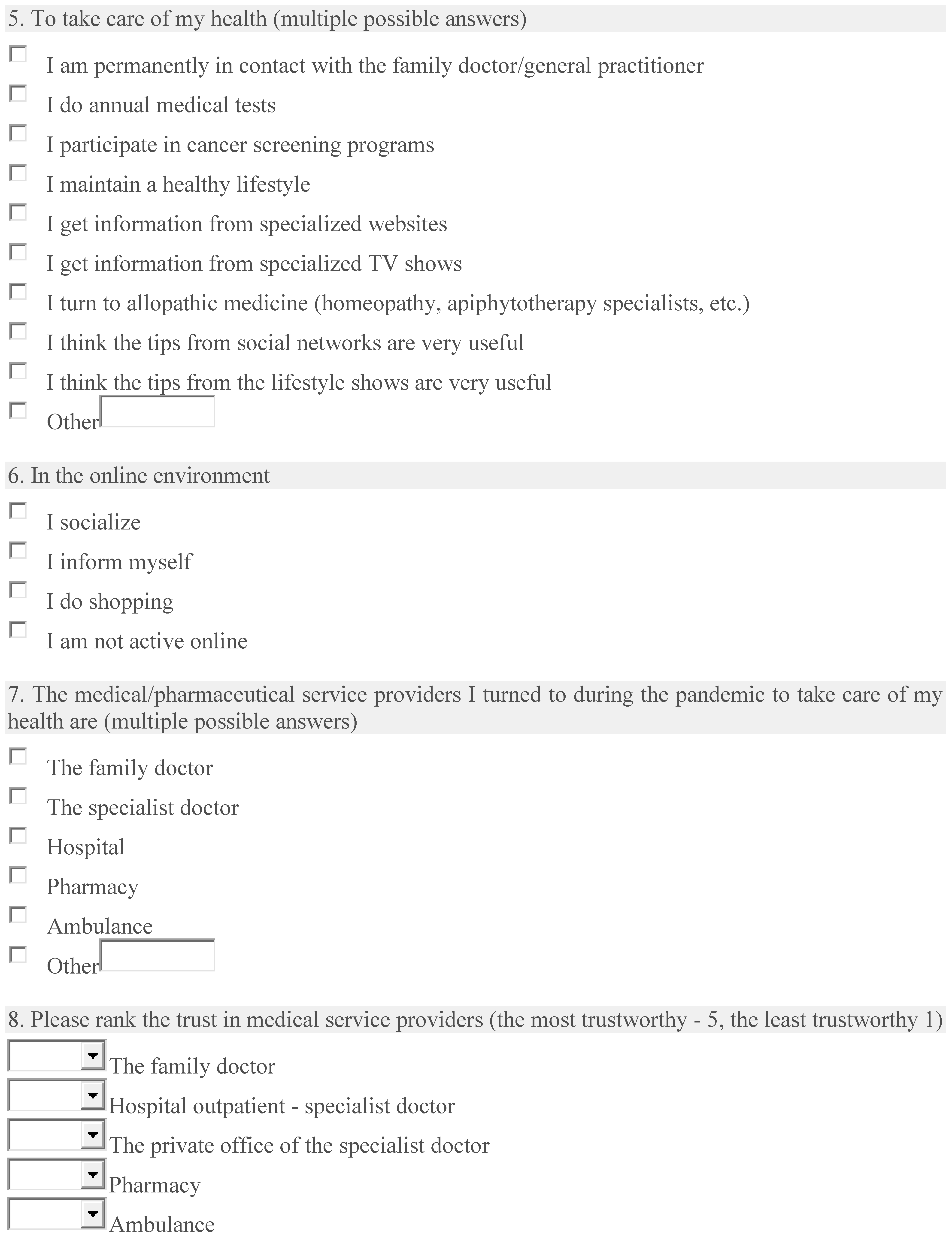

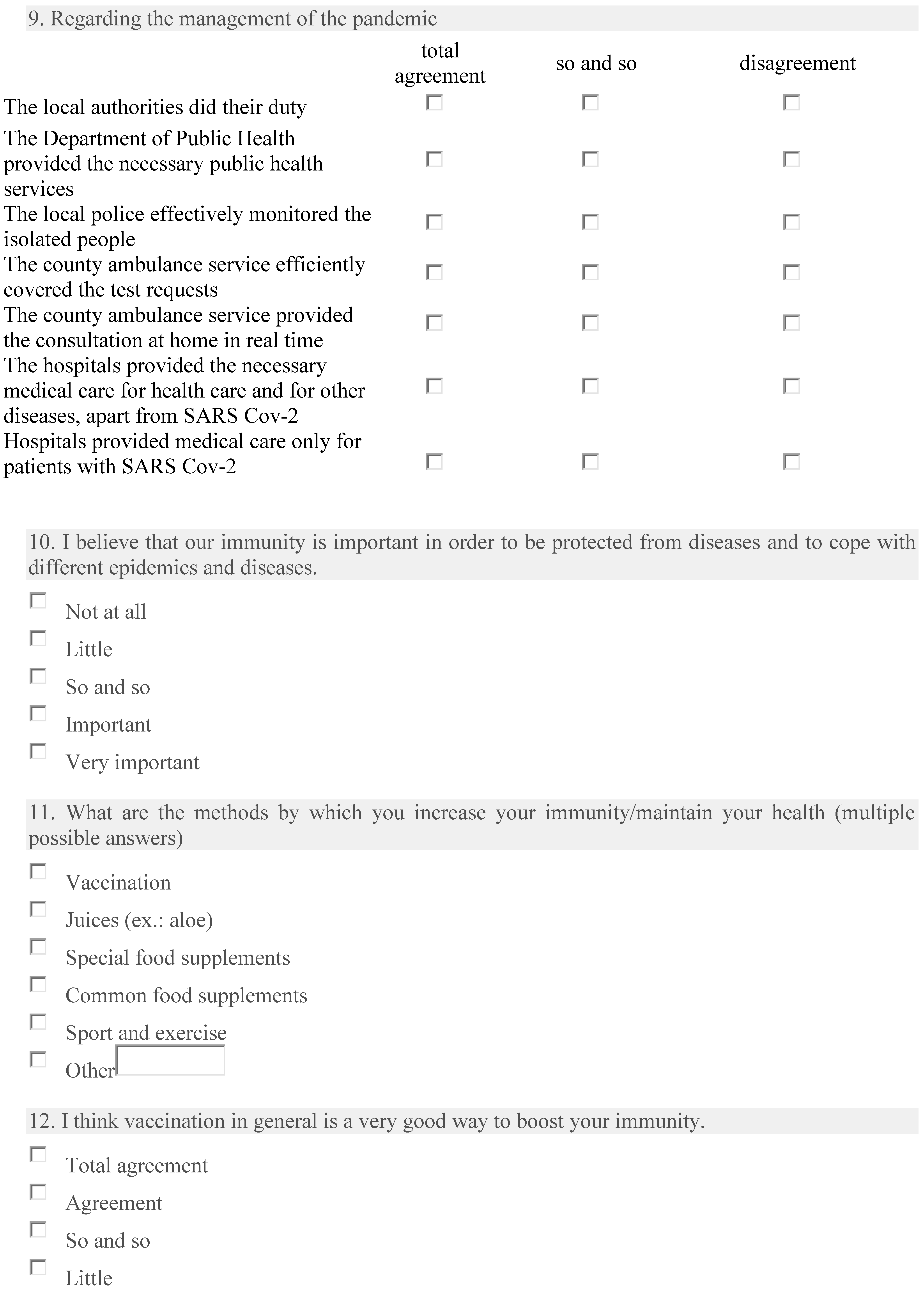

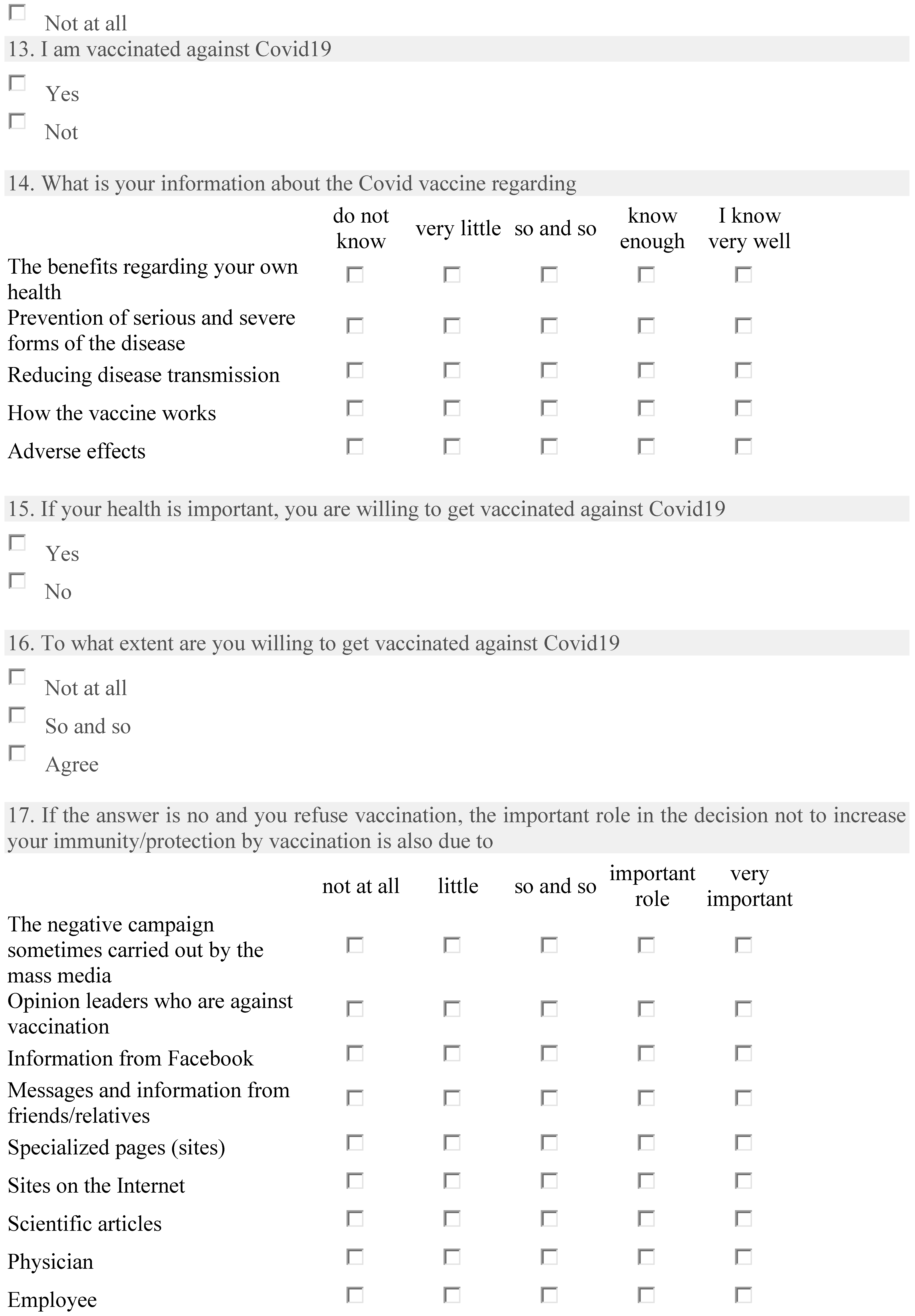

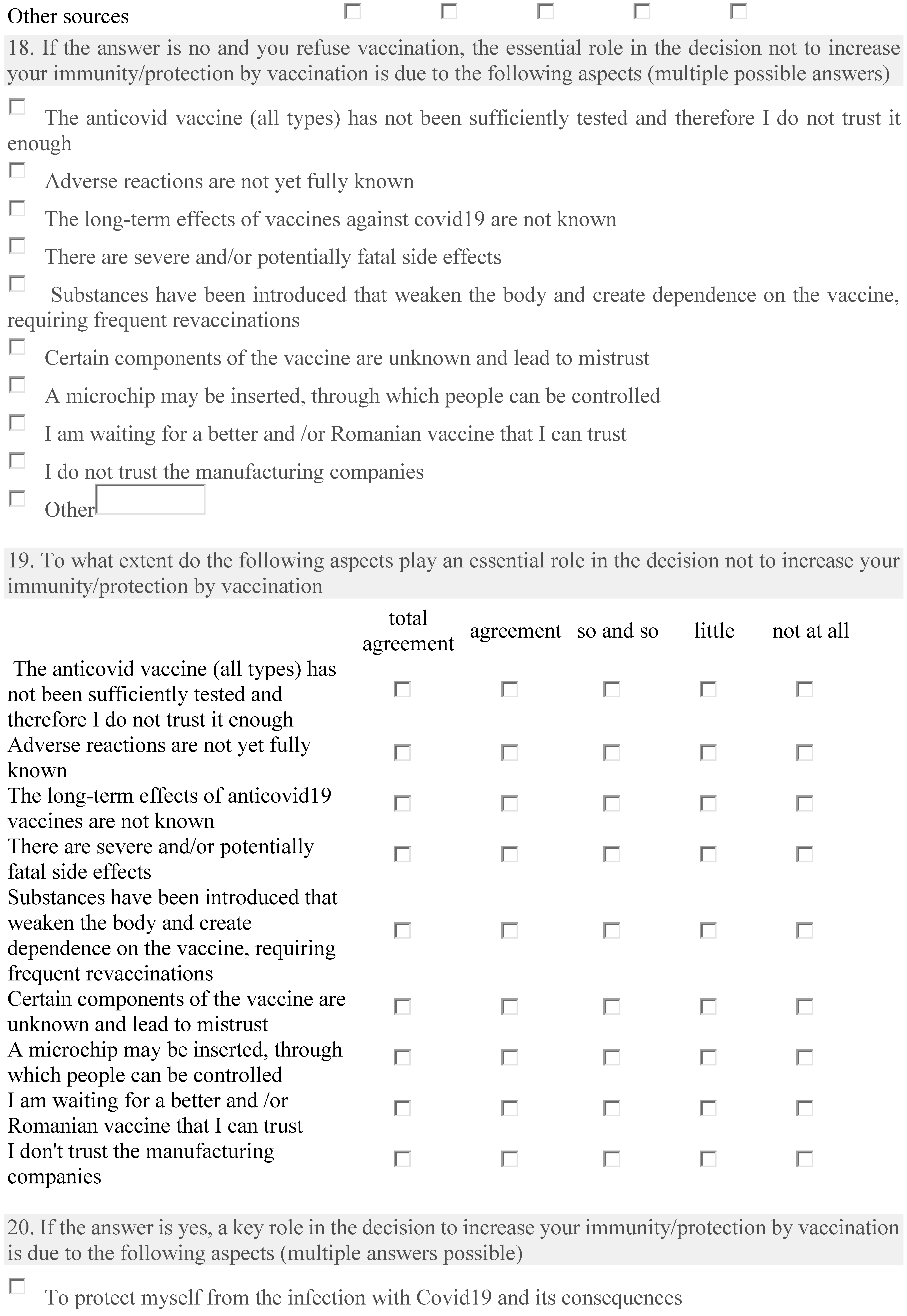

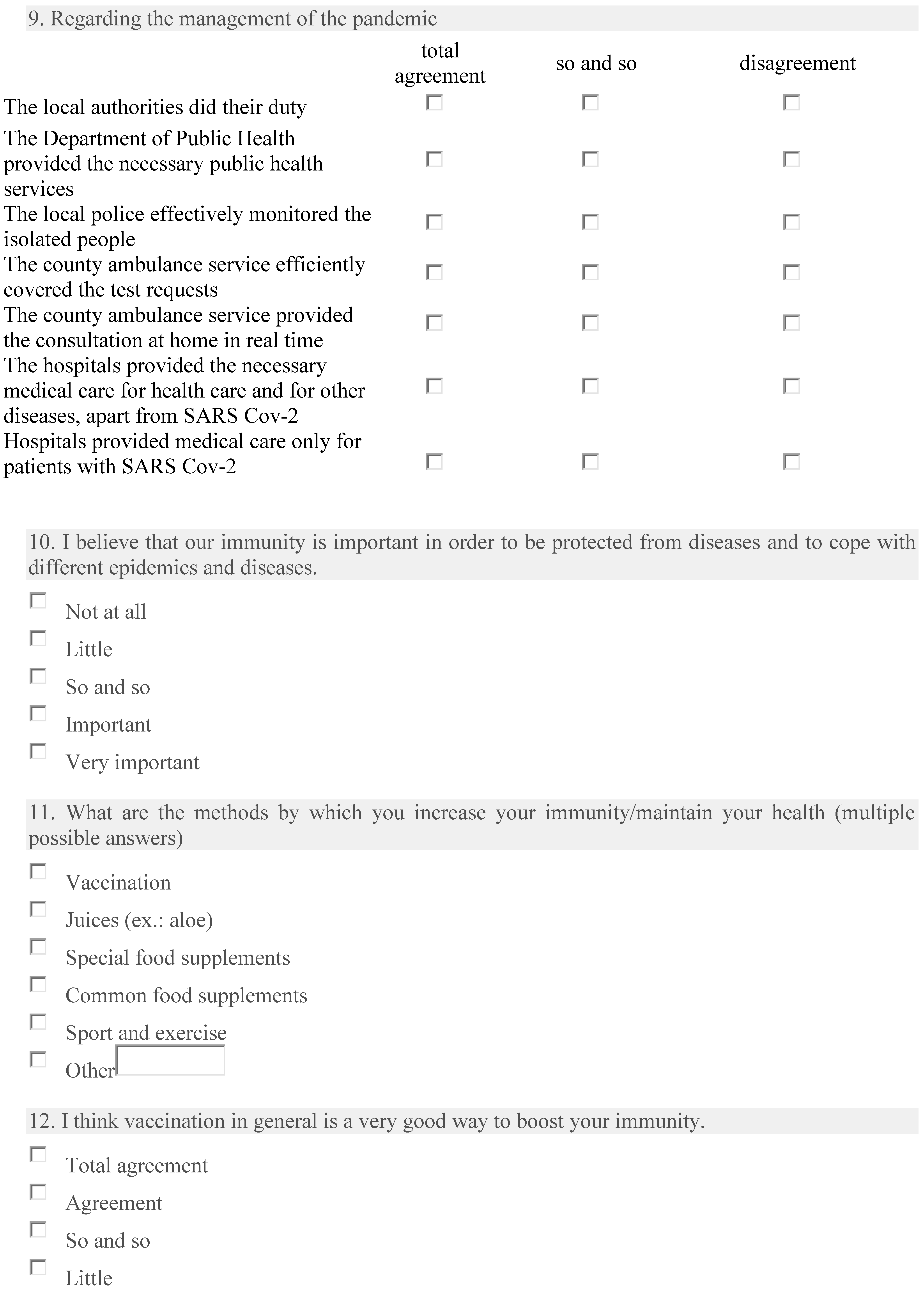

Beginning with the premise that well-informed people have a modern lifestyle that emphasizes health, the positive role of physical activity, and sustainability, we devised a 27-item questionnaire consisting of multiple-choice questions to investigate personal attitudes towards disease prevention measures in general and vaccination in particular.

2. Materials and Methods

The purpose of this study was to analyze the reasons for rejecting or accepting vaccination in order to develop tools to encourage unvaccinated individuals to make a vaccination decision, as well as to empirically determine the relationships between various factorial variables and the non-vaccinating behavior of the target population to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

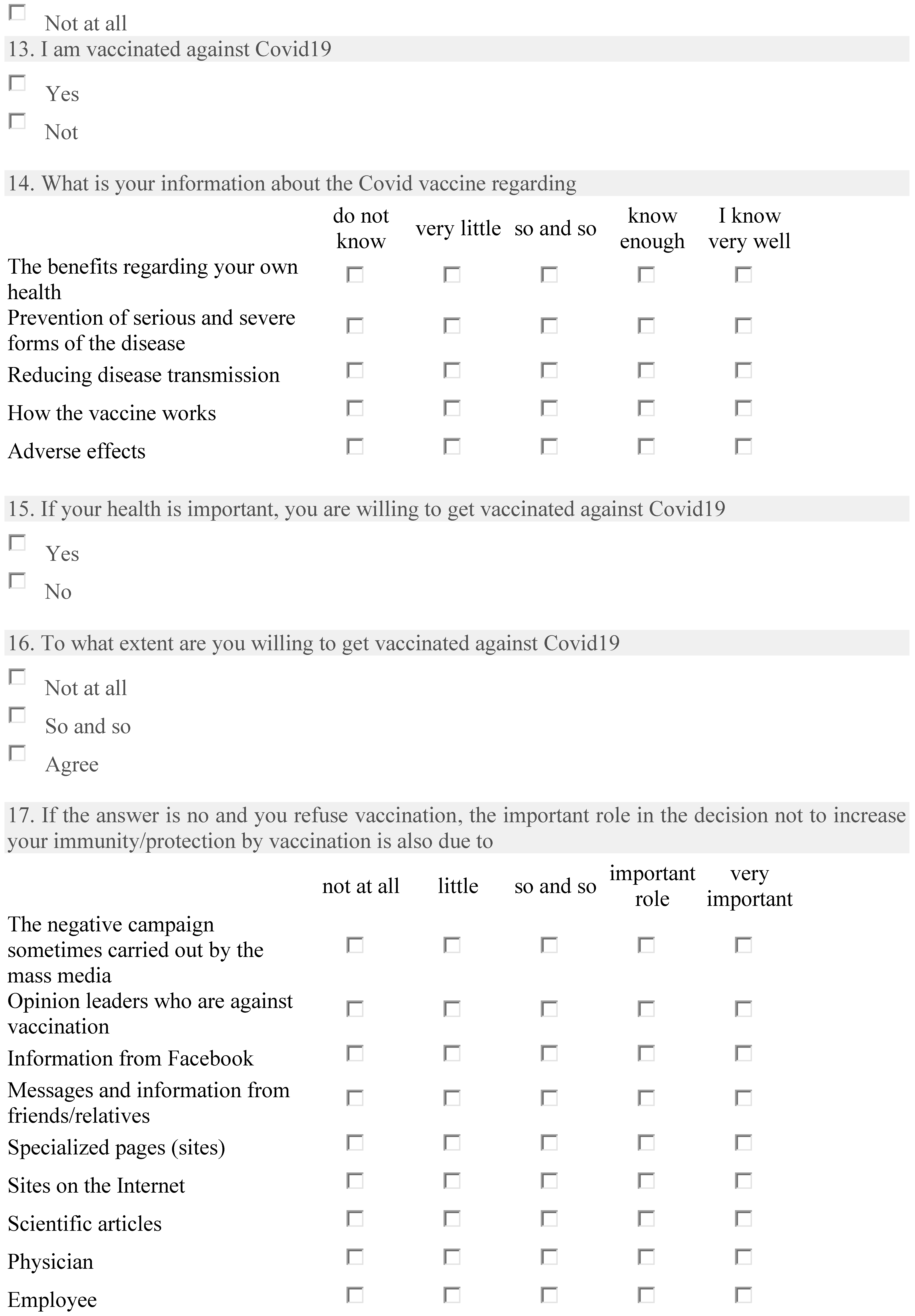

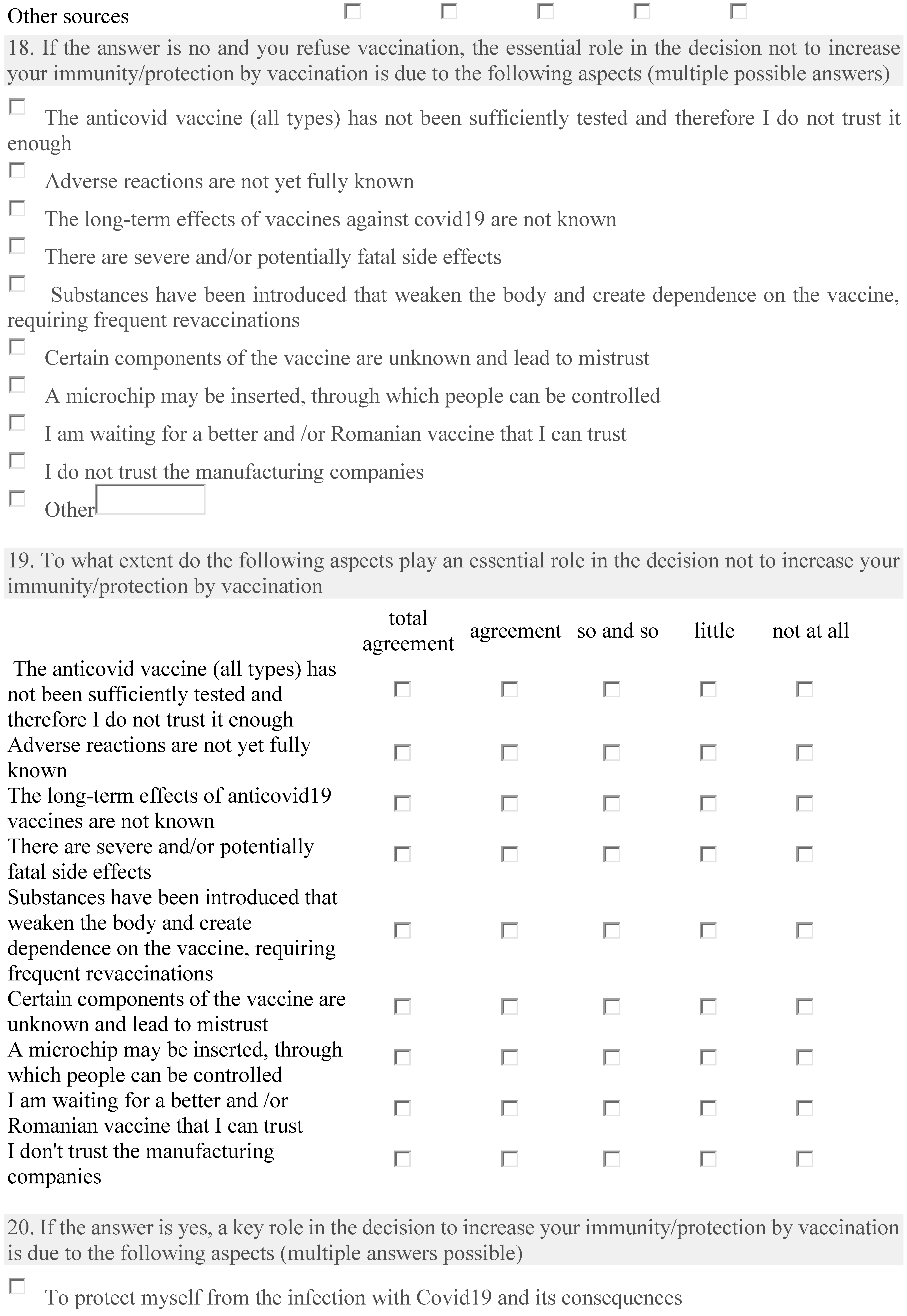

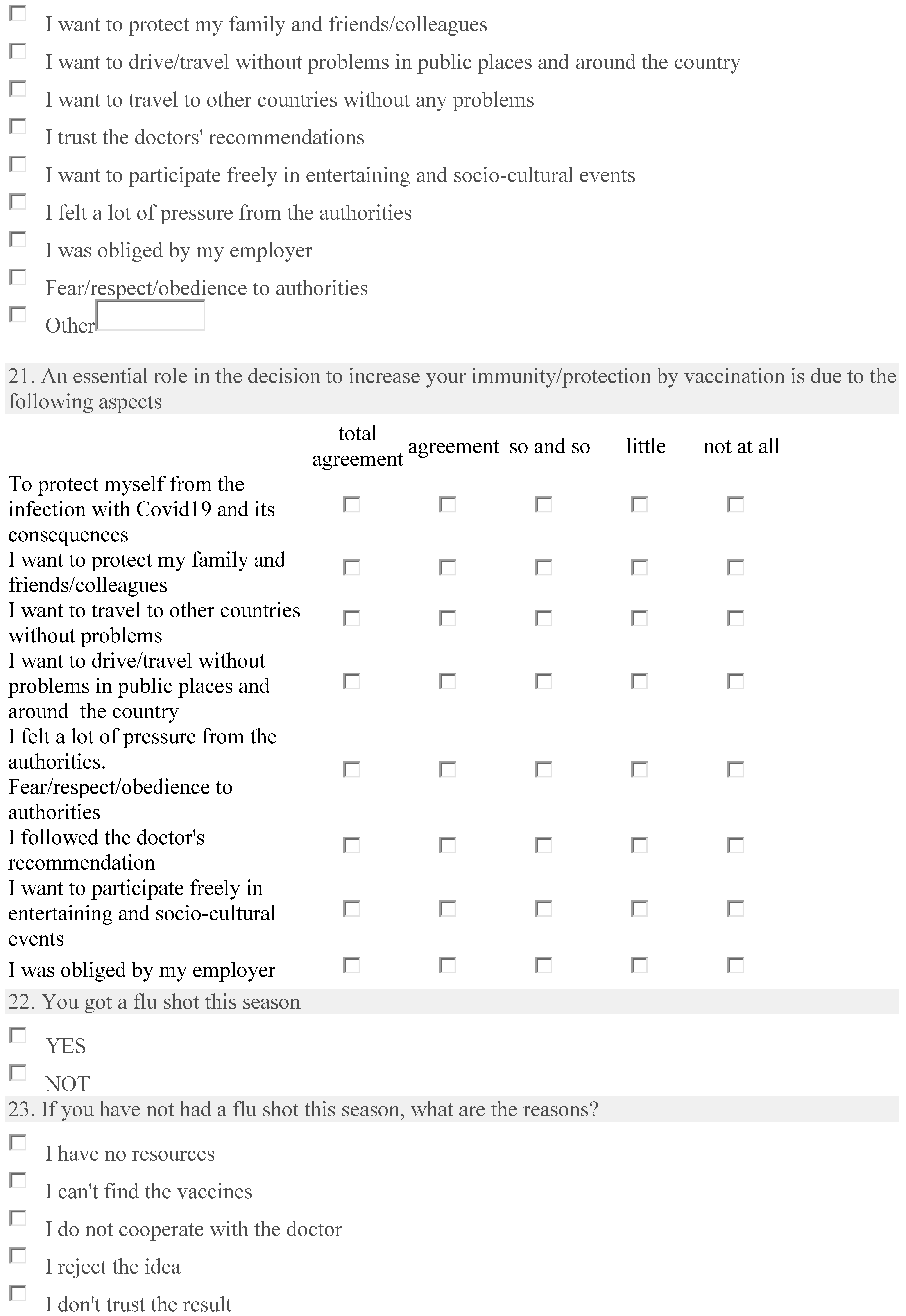

We developed a 27-item questionnaire (Appendix A), which includes demographic data (age, gender), socio-professional data, and movement-related information, based on the premise that people are informed by scientifically validated sources and live a modern lifestyle that emphasizes health, the positive role of physical activity, and sustainability (occupation, environment). Multiple-choice questions probed respondents’ attitudes toward disease prevention measures in general, and vaccination against COVID-19, influenza, and other diseases for which there are vaccines in particular. The formulation of questions addressing vaccine aversion was based on the findings of previous studies [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The questionnaire items addressed the level of satisfaction with the pandemic activities of local authorities, county public health authorities, the emergency medical care system, primary care, specialized medical care, and emergency medical care. For a preliminary study on the decision of citizens to receive the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the following hypotheses were considered:

H1:

A person’s vaccination status is determined by the knowledge he or she has regarding the vaccine.

H2:

External influences on the decision not to vaccinate are related to the evaluation of the vaccine itself.

H3:

There is a connection between external influences on the decision not to vaccinate and the customers’ reasons, which play a crucial role in the person’s decision not to protect themselves through vaccination.

H4:

An association exists between external influences on the decision not to vaccinate and agreement/disagreement on COVID-19 vaccination.

H5:

There is a correlation between online activity and external influences on the decision not to vaccinate.

H6:

There is a link between online activity and opinion about vaccines in general (not just for COVID-19).

H7:

There is a connection between the reasons of the customers, who play a crucial role in the decision not to protect themselves by vaccination, and the agreement/disagreement regarding vaccination against COVID-19.

H8:

There is a connection between the fundamental reasons for refusing COVID-19 vaccination and the choice to vaccinate.

H9:

There is a connection between the essential grounds for refusing COVID-19 vaccination and vaccination status.

H10:

There is a correlation between a positive view of vaccines in general (not just for COVID-19) and the decision to vaccinate against COVID-19.

H11:

There is a connection between the decision to vaccinate against COVID-19 and the vaccination status.

H12:

There is a correlation between the decision to vaccinate against COVID-19 and the vaccination status of individuals who place a high value on their own health.

The questionnaires were administered online as well as on paper between October and December 2021, and results were then entered into the database. Using the SmartPLS3.3 program [18], the reliability and validity of the data were examined.

A total of 1673 respondents with an average age of 36.50 years and a gender distribution of 78.56 percent females chose to complete the survey. The respondents completed 94.5% of the questionnaires autonomously, while the interviewer helped respondents to complete 5.5% of the questionnaires.

3. Results and Discussion

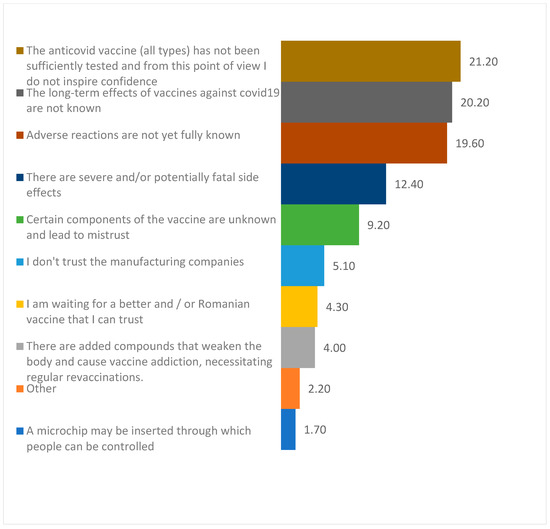

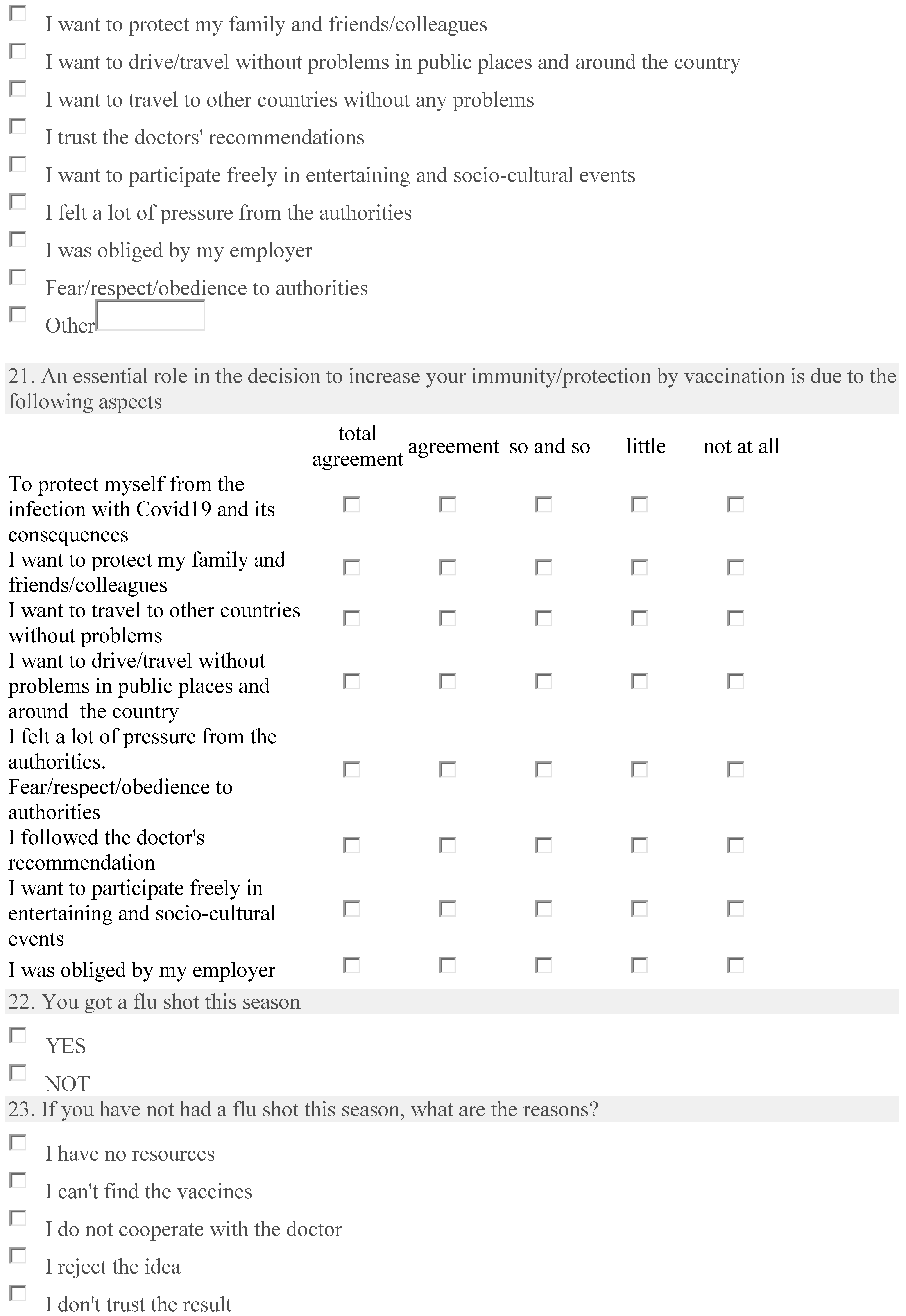

Although 63.4% of respondents from our study agreed that vaccination is an extremely effective method for boosting immunity, vaccination is not a widely accepted practice. The vaccination acceptance rate is consistent with the statistics revealed in previous studies, which indicate a global percentage of 71.5%, ranging from 90% in China to 55% in Russia [19]. Within this broader context, 65.2% of Romanian respondents reported being immunized against COVID-19. The percentage is higher than that found in other European countries such as Poland (56.31%) [19] and France (58.89%) [19], but it should be noted that 89.9% of respondents in our study declared a medium or high level of medical knowledge. This high level of knowledge could explain why the vaccination acceptance rate is higher in our study group than in other European countries. The percentage of respondents who approve of immunization against COVID-19 varies not only from country to country or across occupational groups [20], but also with the length of time since the vaccine’s introduction into medical practice. The reasons for refusing vaccination against COVID-19 also change over time [21]. It is worth noting that at the time of survey completion (October–December 2021), 10.2% of respondents were also vaccinated with the influenza vaccine for the 2021–2022 season, even though no negative influence was detected and there were no safety concerns regarding co-administration [22]. The results of an investigation into the explanations for COVID-19 vaccination refusal for our subjects is reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine reluctance.

Regarding reasons for vaccine reluctance (Table 1), our findings concur with those of other meta-analyses [23,24], in which side effects, lack of trust, or concern about potential side effects were the most prevalent. A total of 24.8% from the unvaccinated respondents believed in the possibility of conspiracy theories, supporting the conclusion of a previous study that “conspiracy beliefs pose a significant threat to public health” [25]. For this reason, it is essential to find the most effective communication strategy, such as conveying the weight of evidence and scientific consensus surrounding vaccines and related myths, or incorporating humor and warnings about encountering misinformation [26].

Table 1.

Aspects playing an essential role in the decision to not vaccinate.

It is also worth mentioning that from the unvaccinated respondents, 52.0% indicated they would be vaccinated, whereas 21.2% rejected the idea and 11.0% did not trust the result. Reluctance to vaccinate is not a generally applicable principle, as 56% of respondents believe vaccines are beneficial, 24.9% agree with some of them, and 19% agree with those that prevent childhood diseases but not the COVID-19 vaccine. However, 61.2% of respondents agree that vaccination has contributed to a decline in the number of hospitalized cases in countries with vaccination rates exceeding 80%. According to other studies, the vaccine was found to be 68.8% effective in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization [27]. This may explain why a high proportion (56%) of respondents in our study believe the COVID-19 vaccine to be beneficial.

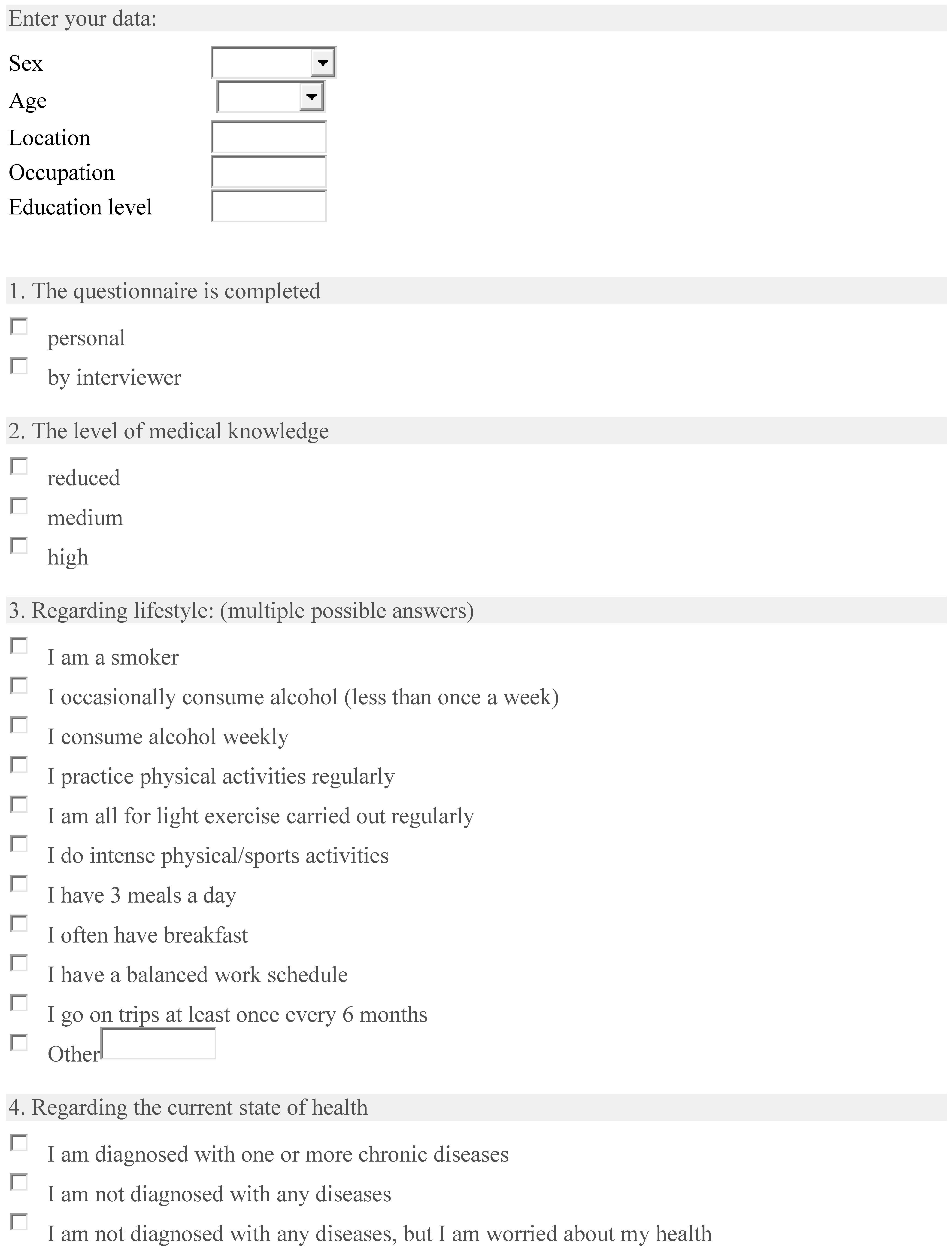

In order to gain a better understanding of the factors that lead to vaccination acceptance, non-vaccinated respondents were asked to answer additional questions. Results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Information regarding self-reported knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine.

These data are consistent with global predictors of vaccine reluctance [28].Using additional questions, we studied the determinants of vaccine refusal among the unvaccinated. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Opinion on the role in the decision to not vaccinate.

As can be seen, the role of social media in vaccine reluctance is relatively minor. Another previous study suggests that social media vaccination campaigns are ineffective [29]. The high proportion of unvaccinated respondents who cited doctors as an important factor in their decision not to be vaccinated was also observed at the international level, where the overall acceptance of vaccination was 51% [28] among healthcare workers, with statistically significant heterogeneity by gender, age, or medical specialty. In our study, females between the ages of 41 and 50 had the highest acceptance rate (77.1%) for the COVID-19 vaccine, while males between the ages of 31 and 40 had the lowest rate (34.6%). It is important to note that in our study, the majority of respondents were female (78.57%), but there is no correlation between the number of males surveyed and vaccine acceptance [26].

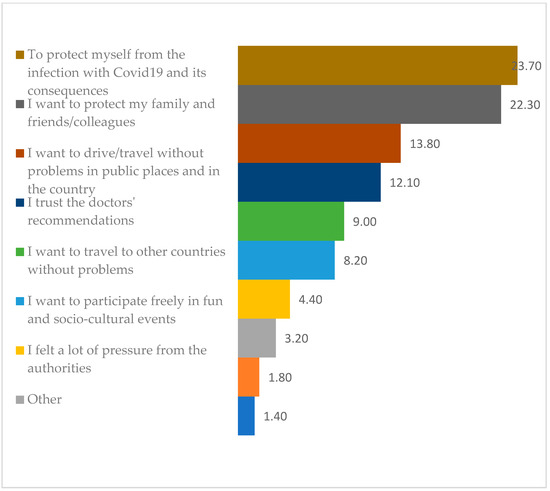

Non-vaccinated respondents were solicited for more information in this regard in order to find factors that could increase vaccination acceptance. Results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Reasons for vaccination cited by unvaccinated subjects.

This paper’s primary objective is to empirically determine the relationships between various factorial variables and the non-vaccinating behavior of the target population, as well as the implications of managing their current situation on their future vaccination intention. In designing this research, we assumed that vaccine reluctance is caused by factors related to the vaccine (not believing in its safety, quality, or efficacy) on the one hand, and by media information, opinion leaders, and known individuals on the other.

In order to test hypotheses and develop a model, we first assessed the trustworthiness (reliability) and validity of the collected data. The concepts of reliability and validity are used to evaluate the quality of research. They indicate the effectiveness of a method, technique, or test. Validity refers to the precision of a measure, whereas reliability refers to the consistency of a measure. When designing research, it is essential to consider reliability and validity, particularly in quantitative research.

The variables’ dependability is evaluated utilizing the Cronbach’s alpha method and composite reliability (CR). The results regarding reliability and validity, as well as the factor loads for the remaining elements, are presented in Table 1 for the overall sample and each specific sample. It has been determined that the alpha values and CRs in the calculation performed exceed the minimum recommended value of 0.700. The Average Variation Extracted (AVE) and correlation coefficients (CRs) were all greater than or close to 0.500 and 0.700, supporting convergent validity. Due to the large sample size and its representativeness, the results reflect those of the broader population, are based on a clear, easily repeatable methodology, and show that the nine constructs in the proposed model are robust from a scientific perspective (statistically): information about vaccine; non-vaccination reasons; online activity; reasons evaluation for non-vaccination; reasons for vaccination; and reasons for vaccination evaluation.

Cross-loading was used to evaluate the discrimination’s efficacy. All factor loads are greater than their respective cross-loads, indicating discriminatory validity. The discrimination’s validity was also evaluated using the criteria proposed by Fornelland Larcker and the heterotrait–monotrait method (HTMT). The outcomes of both tests are displayed in Table A1 from Appendix A.

We utilized SmartPLS 3.3 to assess the confidence in the collected data (reliability) and the validity of the data. As shown in Table A1 from Appendix A, for all the indicators used in the assessment of validity and reliability, Cronbach’s alpha, rhoA, composite reliability, and Average Variation Extracted (AVE), the result is positive, and the collected data are accurate and reflective of reality.

We have also examined significant connections between the questions asked and the formulated constructs. The results are presented in the table (Table A2 from Appendix A), which demonstrates a very strong correlation between the constructs used in the development of the relationship model in the SmartPLS program and the survey questions. Each response was coded in order to be used in SmartPLS program.

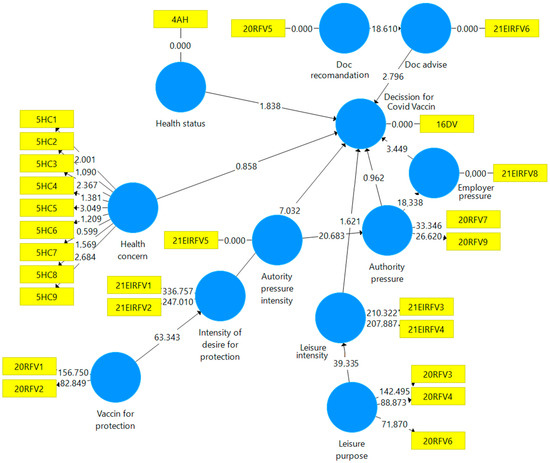

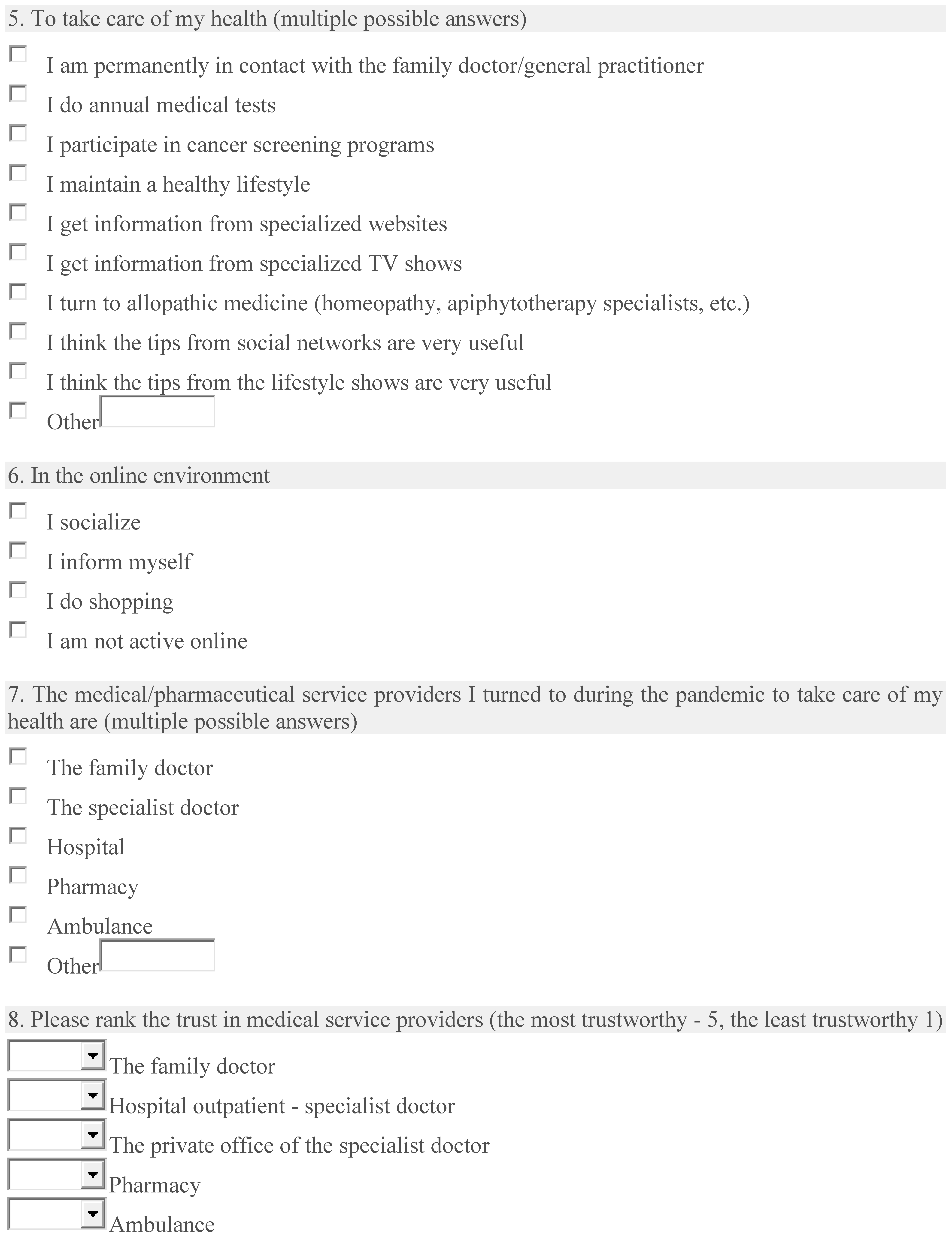

We developed an empirical model of the logically possible relationships between these constructs, and after processing in the SmartPLS program, we obtained the model depicted in Figure 3 and loading factors for each construct (outer loadings) according to Table A2 from Appendix A. In Table 4, each item of the questionnaire with associated code is presented.

Figure 3.

Loadings variables within the model.

Table 4.

Item from the questionnaire used in the model and associated code.

The loading factors for each construct that are found to have a high value, as those factors observed in the research to have a significant impact within each construct, were selected through multiple interactions. This method aids in gaining a comprehensive understanding of a concept’s underlying elements.

Using the SmartPLS program, we have calculated the correlation between the latent variables based on the data presented in Table A3 from Appendix A. In some cases, based on the correlation coefficient, there are fairly robust correlations between the proposed constructions. Correlation analysis between latent variables reveals relationships that cannot be directly observed or measured. If we correlate these latent variables with other observable variables, we can infer the values of the latent variables from the observations of the observable variables. The analysis of the correlation between the latent variables reveals that there is a strong latent link between the criteria underlying the evaluation of non-vaccination or vaccination and variables such as information about vaccine (0.886), non-vaccination reasons (0.810), and vaccination for health (0.833), whereas there is a weaker latent link between the expectations related to the vaccine as a product and the criteria underlying the evaluation of non-vaccination (0.494) or the denial (Table A3 in Appendix A).

In addition, a descriptive statistic has been developed, which can assist us in better comprehending the distribution of statistical values and expanding the descriptive analysis (Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5.

Indicative statistics trailing coefficients.

Table 6.

Hypothesis mean, STDEV, T-values, p-values.

The acceptance of this study’s hypotheses by means of statistical tests is displayed in the Table 7.

Table 7.

Result of tested hypotheses.

In a large number of previous meta-analyses [30,31] it was found that social factors were associated with vaccine acceptance. Even though efforts to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 may increase the use of social media as individuals try to remain connected while physically apart [32], our findings do not support the role of social media in vaccine hesitancy due to the high level of medical knowledge reported by respondents, which has also been reported by other studies [25].In a separate study, a strong correlation between attitude and vaccination intent was also discovered [33].Three parameters are known to influence a person’s willingness to accept a vaccine: complacency, confidence, and convenience [34]. Our research indicates that a well-designed and targeted informational campaign could increase vaccine acceptance. General vaccine information is recognized as a predictor factor for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [35].The available COVID-19 vaccines are the most effective means of containing the pandemic [36]. Our study found a vaccine acceptance rate of up to 56%, which is significantly lower than the globally averaged acceptance rate of the COVID-19 vaccine, which was 64.9% [95% CI: 60.5% to 69.0%] [37]. The correlation between vaccine acceptance in general and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in particular was found in our study as well as in previous studies that investigated the confidence of healthcare professionals in theCOVID-19 vaccine [38]. The role played by socioeconomic status [39] or by a modern lifestyle that emphasizes health was shown to be a factor by our study as well as by previous findings [40]. The health systems are organized differently, but the medical approach to pandemic preparedness was guided by WHO recommendations, ensuring a global response to a global threat [41]. Administrative measures that aided the implementation of public health interventions had varying effects. [42] While in Poland, public health was legally prioritized over individual liberties [43], punitive administrative measures taken against those who violated the regulations were cancelled in Romania due to some legal inconsistencies. In this context, 1.4% of respondents chose to vaccinate because they were afraid of the authorities. The hesitancy for COVID-19 vaccination was found to be a significant problem in older people, particularly those with low incomes and low levels of education, according to a previous study [9]. Individuals who are altruists, care for others, follow government recommendations, and support collective responsibility are more likely to receive COVID-19 vaccination, according to an explanatory factor analysis, findings that are supported by previous research [43].Other studies have found that social media or online activity has a relatively low influence on the decision not to vaccinate, but these channels could be used in order to understand vaccination perceptions [44]. The emotional approach to subjects of public interest could lead to an increase in the vaccination acceptance rate [45]. Employer pressure or workplace constraints do not increase the intention to vaccinate, according to the current study and another conducted in Poland [46]. The measures taken by the employer during the pandemic to protect the staff can contribute to the state of safety at the workplace [47].

4. Conclusions

The vaccination status of a person depends on the knowledge they have about the vaccine. From this perspective, it would be advantageous for health authorities to communicate more openly on potential adverse reactions. Within this context, the companies whose COVID-19 vaccines have been approved for human use are required to present their own results (studies on the beneficial effects of the vaccine concurrently with the possible adverse reactions). Additionally, the approval authorities are required to submit the conclusions of their own studies or validated studies conducted by other research entities with the utmost confidence. This research has shown that there is a connection between the decision not to vaccinate and the evaluation of the vaccine itself, and that citizens are practically influenced by external factors when deciding not to vaccinate. There is no clear connection between online activity and outside influences on the decision not to vaccinate. The decision not to vaccinate is unique to online-active individuals. In the model utilized here, there is a correlation between the decision to vaccinate against COVID-19 for those who place a high value on individual health and the vaccination status. Our approach can be used to determine the causes of vaccination refusal in a community, whether for a newly released vaccine or immunization in general. Our model focuses on COVID-19 vaccination, however a similar pattern applies to all vaccines. In a community with low vaccination rates, it is possible to identify the perception-related factors that cause parents (in the case of being responsible for children) or adults to be reluctant to vaccinate. Information campaigns might concentrate on factors unique to each community.

4.1. Study Limitation

Despite the fact that this study is based on a large and representative sample of Romanians, the percentage of vaccinated people in the sample is higher than the percentage of vaccinated people in the nation. The primary objective of this first paper was to empirically determine the relationships between various factorial variables and the non-vaccination behavior of the population, i.e., the entire population of Romania. No research was conducted to determine the factors that encourage vaccination, despite the fact that these data are available as a result of our study. This diverse and intricate information will be utilized in an upcoming article.

4.2. Futher Directions

A future research direction will be to deepen this study in order to empirically determine the relationships between various factor variables and the behavior of vaccine beneficiaries. The aim will be to better understand the factors, the interdependence of relationships, and the mechanisms that determine vaccination. The implications for process management and the management of the vaccination situation including vaccination intention, mode, techniques, and channels of communication with the vaccine recipients represent an additional future research direction using modern tools such as the internet of things [48].

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to the study and writing of this research. Conceptualization—S.G.S. and D.C.; methodology—S.G.S. and D.C.; software—L.D.C.; validation—S.G.S. and L.D.C.; formal analysis—S.P.; investigation—E.C., M.F.P., C.S.R.J. and L.R.B.; resources—M.F.P.; data curation, L.D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.; writing—review and editing, L.D.C. and L.R.B.; visualization—S.P. and G.-C.B.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The Perception of Vaccination against COVID-19

This survey aims to analyze the perception of the general population regarding vaccination against COVID-19.

Table A1.

Cronbach values and composite reliability. Indicators of reliability and validity.

Table A1.

Cronbach values and composite reliability. Indicators of reliability and validity.

| Cronbachs Alpha | rhoA | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information about vaccine | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.989 | 0.946 |

| Non-vaccination reasons | 0.982 | 0.982 | 0.984 | 0.859 |

| Online activity | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Reasons evaluation for non-vaccination | 0.977 | 0.981 | 0.980 | 0.844 |

| Reasons for non-vaccination decision | 0.879 | 0.893 | 0.916 | 0.733 |

| Regarding vaccine | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Vaccination decision | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Vaccination for health | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Vaccination status | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

Table A2.

Outer loadings.

Table A2.

Outer loadings.

| Question | Informations about Vaccine | Non-VaccinationReasons | Online Activity | Reasons forEvaluation for Non-Vaccination | Reasons for Non-Vaccination Decision | Regarding Vaccines | Vaccination Decision | Vaccination for Health | Vaccination Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are you vaccinated against COVID-19? | 1.000 | ||||||||

| What is your information on the COVID-19vaccine: | 0.976 | ||||||||

| 0.984 | ||||||||

| 0.976 | ||||||||

| 0.974 | ||||||||

| 0.953 | ||||||||

| 1.000 | ||||||||

| If your health is important, are you willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine? | 1.00 | ||||||||

| To what extent are you willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccination? | 0.886 | ||||||||

| 0.936 | ||||||||

| 0.922 | ||||||||

| 0.933 | ||||||||

| If the answer is no and you refuse vaccination, does your refusal play a significant role in your decision not to increase your immunity/protection through vaccination? | 0.947 | ||||||||

| 0.949 | ||||||||

| 0.928 | ||||||||

| 0.923 | ||||||||

| 0.915 | ||||||||

| 0.867 | ||||||||

| 0.885 | ||||||||

| 0.883 | ||||||||

| 0.786 | ||||||||

| 0.905 | ||||||||

| 0.906 | ||||||||

| 0.892 | ||||||||

| 0.923 | ||||||||

| 0.940 | ||||||||

| 0.931 | ||||||||

| 0.936 | ||||||||

| 0.905 | ||||||||

| 0.929 |

Table A3.

Latent Variable Correlations.

Table A3.

Latent Variable Correlations.

| Variable | Information about Vaccine | Non-Vaccination Reasons | Online Activity | Reasons forEvaluation for Non-Vaccination | Reasons for Non-vaccination Decision | Regarding Vaccine | Vaccination Decision | Vaccination for Health | Vaccination Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information about vaccine | 1.000 | 0.848 | 0.011 | 0.886 | 0.735 | 0.523 | 0.856 | 0.840 | 0.917 |

| Non-vaccination reasons | 0.848 | 1.000 | −0.013 | 0.810 | 0.783 | 0.587 | 0.807 | 0.864 | 0.912 |

| Online activity | 0.011 | −0.013 | 1.000 | −0.014 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.009 | −0.014 | −0.012 |

| Reasons for evaluation for non-vaccination | 0.886 | 0.810 | −0.014 | 1.000 | 0.671 | 0.494 | 0.874 | 0.833 | 0.919 |

| Reasons for non-vaccination decision | 0.735 | 0.783 | 0.022 | 0.671 | 1.000 | 0.623 | 0.628 | 0.825 | 0.814 |

| Regarding vaccine | 0.523 | 0.587 | 0.001 | 0.494 | 0.623 | 1.000 | 0.396 | 0.688 | 0.625 |

| Vaccination decision | 0.856 | 0.807 | 0.009 | 0.874 | 0.628 | 0.396 | 1.000 | 0.716 | 0.871 |

| Vaccination for health | 0.840 | 0.864 | −0.014 | 0.833 | 0.825 | 0.688 | 0.716 | 1.000 | 0.950 |

| Vaccination status | 0.917 | 0.912 | −0.012 | 0.919 | 0.814 | 0.625 | 0.871 | 0.950 | 1.000 |

References

- Horga, N.G.; Cirnatu, D.; Kundnani, N.R.; Ciurariu, E.; Parvu, S.; Ignea, A.L.; Borza, C.; Sharma, A.; Morariu, S. Evaluation of Non-Pharmacological Measures Implemented in the Management of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Romania. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, E.; Gagnon, D.; MacDonald, N.E.; Sage Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: Review of published reviews. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4191–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Wong, R.M. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: A meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5131–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Jones, A.; Lesser, I.; Daly, M. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2024–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujovich-Dunn, C.; Kaufman, J.; King, C.; Skinner, S.R.; Wand, H.; Guy, R.; Leask, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness of decision aids for vaccination decision-making. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3655–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Schulz, W.S.; Chaudhuri, M.; Zhou, Y.; Dubé, E.; Schuster, M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Wilson, R.; The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: The development of a survey tool. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4165–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Saccaro, C.; Demurtas, J.; Smith, L.; Dominguez, L.J.; Maggi, S.; Barbagallo, M. Prevalence of unwillingness and uncertainty to vaccinate against COVID-19 in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescitelli, M.E.D.; Ghirotto, L.; Sisson, H.; Sarli, L.; Artioli, G.; Bassi, M.; Appicciutoli, G.; Hayter, M. A meta-synthesis study of the key elements involved in childhood vaccine hesitancy. Public Health 2019, 180, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotfas, L.-A.; Delcea, C.; Gherai, R. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the Month Following the Start of the Vaccination Process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, T.C.; Fetecau, B.I.; Giurgiuca, A.; Tudose, C. Acceptance and Factors Influencing Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine in a Romanian Population. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolescu, L.S.C.; Zaharia, C.N.; Dumitrescu, A.I.; Prasacu, I.; Radu, M.C.; Boeru, A.C.; Boidache, L.; Nita, I.; Necsulescu, A.; Medar, C.; et al. COVID-19 Parental Vaccine Hesitancy in Romania: Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotta, I.; Kalcza-Janosi, K.; Szabo, K.; Marschalko, E.E. Development and Validation of the Multidimensional COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărcău, F.C.; Peptan, C.; Nedelcuță, R.M.; Băleanu, V.D.; Băleanu, A.R.; Niculescu, B. Parental COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy for Children in Romania: National Survey. Vaccines 2022, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dima, A.; Jurcut, C.; Balaban, D.V.; Gheorghita, V.; Jurcut, R.; Dima, A.C.; Jinga, M. Physicians’ Experience with COVID-19 Vaccination: A Survey Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maftei, A.; Holman, A.C. SARS-CoV-2 Threat Perception and Willingness to Vaccinate: The Mediating Role of Conspiracy Beliefs. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 672634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristea, D.; Ilie, D.-G.; Constantinescu, C.; Fîrțală, V. Vaccinating against COVID-19: The Correlation between Pro-Vaccination Attitudes and the Belief That Our Peers Want to Get Vaccinated. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. “SmartPLS 3.” Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. 2015. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E.; Alicandro, G.; Scarpino, V. Attitudes towards influenza vaccine and a potential COVID-19 vaccine in Italy and differences across occupational groups, September 2020: Attitudes towards influenza vaccine and a potential COVID-19 vaccine in Italy. Med. Lav. 2020, 111, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C. Global Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Mosnier, A.; Gavazzi, G.; Combadière, B.; Crépey, P.; Gaillat, J.; Launay, O.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Coadministration of seasonal influenza and COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of clinical studies. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2131166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.N.; Biswas, M.; Islam, E.; Azam, S. Potential factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Jin, H.; Lin, L. Vaccination against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of acceptability and its predictors. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anakpo, G.; Mishi, S. Hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccines: Rapid systematic review of the measurement, predictors, and preventive strategies. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2074716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierwiaczonek, K.; Gundersen, A.B.; Kunst, J.R. The role of conspiracy beliefs for COVID-19 health responses: A meta-analysis. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 46, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Shao, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: A literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 114, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomoni, M.G.; Di Valerio, Z.; Gabrielli, E.; Montalti, M.; Tedesco, D.; Guaraldi, F.; Gori, D. Hesitant or Not Hesitant? A Systematic Review on Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Different Populations. Vaccines 2021, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, H.S.; French, C.E.; Caldwell, D.M.; Letley, L.; Mounier-Jack, S. A systematic review of communication interventions for countering vaccine misinformation. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1018–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Y.A.; Nelson, V.R.; Wiseley, K.; Shen, R.; Roscizewski, A. Do social media campaigns foster vaccination adherence? A systematic review of prior intervention-based campaigns on social media. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 76, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.A.; Failla, G.; Puleo, V.; Melnyk, A.; Lontano, A.; Ricciardi, W. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review of the literature. Eclinicalmedicine 2022, 48, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, M.S.; Kheirallah, K.A.; Aly, M.O.; Ramadan, A.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Elbarazi, I.; Deghidy, E.A.; El Saeh, H.M.; Salem, K.M.; Ghazy, R.M. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination psychological antecedent assessment using the Arabic 5c validated tool: An online survey in 13 Arab countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feleszko, W.; Lewulis, P.; Czarnecki, A.; Waszkiewicz, P. Flattening the Curve of COVID-19 Vaccine Rejection—An International Overview. Vaccines 2021, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerretsen, P.; Kim, J.; Caravaggio, F.; Quilty, L.; Sanches, M.; Wells, S.; Brown, E.E.; Agic, B.; Pollock, B.G.; Graff-Guerrero, A. Individual determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, E.; Cartledge, S.; Damery, S.; Greenfield, S. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic; a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, N.; Alzahrani, K.J.; Ahmed, S.N.; Dey, S.K. Efficacy, Immunogenicity and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 714170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Acceptance of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines among healthcare workers: A meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 881903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, D.; Shao, L.; Jin, J.; He, Q. Intention to COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among health care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2021, 49, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, C.S.; Mujeeb, A.A.; Mirza, M.S.; Chaudhry, B.; Khan, S.J. Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: A Systematic Review of Associated Social and Behavioral Factors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminia, M.; Afshar, Z.M.; Rajati, M.; Saeedi, A.; Rajati, F. Evaluation of the Acceptance Rate of Covid-19 Vaccine and its Associated Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Prev. 2022, 43, 421–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, D.A.; Demmu, Y.M.; Asefa, Y.A. Global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1044193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezerakos, P.; Dadouli, K.; Agapidaki, E.; Kravvari, C.-M.; Avakian, I.; Peristeri, A.-M.; Anagnostopoulos, L.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Fountoulakis, K.N.; Koupidis, S.; et al. Behavioral and Cultural Insights, a Nationwide Study Based on Repetitive Surveys of WHO Behavioral Insights Tool in Greece Regarding COVID-19 Pandemic and Vaccine Acceptance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paplicki, M.; Susło, R.; Najjar, N.; Ciesielski, P.; Augustyn, J.; Drobnik, J. Conflict of individual freedom and community health safety: Legal conditions on mandatory vaccinations and changes in the judicial approach in the case of avoidance. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Rev. 2018, 20, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Sohail, S.S.; Ubaid, S.; Shakil; Ali, Z.; Hijji, M.; Saudagar, A.K.J.; Muhammad, K. It’s Your Turn, Are You Ready to Get Vaccinated? Towards an Exploration of Vaccine Hesitancy Using Sentiment Analysis of Instagram Posts. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susło, R.; Pobrotyn, P.; Mierzecki, A.; Drobnik, J. Fear of Illness and Convenient Access to Vaccines Appear to Be the Missing Keys to Successful Vaccination Campaigns: Analysis of the Factors Influencing the Decisions of Hospital Staff in Poland concerning Vaccination against Influenza and COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waszkiewicz, P.; Lewulis, P.; Górski, M.; Czarnecki, A.; Feleszko, W. Public Vaccination Reluctance: What Makes Us Change Our Minds? Results of A Longitudinal Cohort Survey. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szentesi, S.G.; Cuc, L.D.; Feher, A.; Cuc, P.N. Does COVID-19 Affect Safety and Security Perception in the Hospitality Industry? A Romanian Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentesi, S.G.; Cuc, L.D.; Lile, R.; Cuc, P.N. Internet of Things (IoT), Challenges and Perspectives in Romania: A Qualitative Research. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).