Abstract

In 2015, the United Nations adopted the Sustainable Development Goals. Several experts on sustainable development have highlighted the need for educational transformation to achieve them on time. Simultaneously, the influence of teen series on the personal and social development of teenagers has been increasingly demonstrated, especially after their boom through video-on-demand digital platforms. Therefore, it is worth asking how the 2030 Agenda goals are presented in teen series, especially in those of public television, such as the Spanish one, due to its commitment to young people and the SDGs (ratified in its official documents). The aim of this study is to propose an analysis tool and, subsequently, to apply it to a content analysis of the digital teen series Boca Norte. The results of the analysis reveal that social issues are presented in Boca Norte, while environmental ones are not. In addition, the results show limitations in the integration of SDG-related issues, especially because they are focused on social relationships between characters rather than on realities, contexts and consequences. The tools’ findings could impact or be linked to teenagers’ education. These conclusions prove that the proposed tool is useful, even for the development of new series for public television aligned with its public commitment.

1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) approved the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): 17 goals signed by the 193 member countries of the UN, including Spain, that aim, among other goals, to eradicate poverty and hunger, fight for gender equality, reduce social inequalities and create a more environmentally sustainable world [1]. These SDGs are included in the 2030 Agenda, whose vision is not only to set out a roadmap [2] for achieving the goals but is also a process of change and transition toward a more sustainable world. To achieve this, transformative education is needed to build much more human capital for economic, social and environmental development [3,4,5,6].

The Government of Spain [7], in its report for the voluntary national review in relation to the SDGs, defines the inclusion of content related to inclusive and sustainable development through informal education as “necessary”. As part of this, the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID) recognizes the important role of the media [8]. As such, it is important to study the influence of television series as a tool that generates strong affective bonds with the audience [9,10,11,12] and, therefore, can be useful as a tool for change, especially for teenagers [10,13,14]. This is at an opportune time, given a change in consumption habits [15,16] and a boom in digital television series (even more so in teen series) due to the arrival of video-on-demand (VOD) platforms [17,18].

Assuming the series can be an educational tool [11], it is worth asking how they can influence the construction of citizenship in the terms proposed by the AECID and the Government of Spain and, therefore, their usefulness in education for sustainable development (ESD), understood as that which provides “the skills, attitudes and values needed to overcome the interrelated global challenges we must face” [19]. Projects such as the Transmedia Literacy Research Project have been developed with the aim of exploring how to educate young people through digital media on issues such as interpersonal development or understanding social requirements [20].

In this context, Spanish public television has adopted Law 17/2006, in which it pays special attention to certain groups, such as children and young people. In addition, one of the first objectives of the Radio Televisión Española Corporation [21] is to create content focused on young audiences on the PlayZ digital platform, where RTVE adapts content in language and format for these audiences, including teen series [22]. On the other hand, Radio Televisión Española (RTVE) has shown a commitment to public service and education [23] and, in recent years, has incorporated the 2030 Agenda as a fundamental axis of its strategic plan [21]. Furthermore, since May 2021, RTVE has had a Directorate for Education, Diversity, Culture and International Radio and Television [24], which its own director, Ignacio Elguero, defines as “a kind of Ministry of Education and Culture” that is committed to working for the Corporation’s public service.

The educational impact that teen series have in relation to the SDGs depends on whether the issues included are integrated into the content [25,26,27,28]. In fact, in the academic field, content analyses of some isolated issues aligned with the 2030 Agenda are frequent, such as gender equality or the LGBT community, but not with the holistic perspective that the United Nations advocate for. For this reason, this paper has proposed an analysis tool, a methodological framework designed to analyze whether and how the issues linked to the 2030 Agenda are present in national teen TV series. This has been validated in a content analysis of the RTVE teen series Boca Norte (PlayZ, 2019), awarded the Ondas for best digital content (2019) and presented by RTVE [21] as a fiction that deals with issues such as feminism or cultural clashes, which could be linked to those of the 2030 Agenda.

First, a review of the literature on the influence of audiovisual fiction on teenage viewers (as a means of informal education) was carried out to subsequently address the concept of teen series and their relationship with the themes of the 2030 Agenda. Second, a way of measuring the insertion of the SDGs in the narratives of teen series has been proposed through an analysis tool evaluated through an expert review. Finally, a content analysis of a digital teen series on national public television (RTVE), Boca Norte, was carried out, and the main results and conclusions are presented.

1.1. Audiovisual Fiction as a Potential Educational Tool for Teenagers

The influence of audiovisual consumption on young people’s behavior has been studied by multiple authors [10,11,12,26,29]. These studies are especially relevant because this audience is in a life stage characterized by the construction of their own identity and sense of belonging [30]. In fact, with the rise of the audiovisual industry and new technologies in recent years, research about education points out the importance of establishing media education for young people due to the potential influence of these new technologies and the media’s effect on them [31,32,33]. Fictional products for young people play a role as an entertainment tool, but also as an informative and social one [34].

Following this line, it is worth highlighting the concept of entertainment-education (EE), that is, “the intentional placement of educational content in entertainment messages” [35] (p. 117). In media, EE is being increasingly used and is defined as a tool “to influence the knowledge, attitudes and behavior of an audience by keeping them engaged through its entertainment value“ [36] (p. 2). Entertainment-education seeks to educate on a specific issue promoting social and individual changes in the audience’s behavior through media communication design [37].

EE was implemented, at first, in the 1970s in developing countries and in the 1980s, it started to be developed in North America and Europe [35,37]. However, in these places, its expansion was slower due to media saturation [37]. In 2002, Singhal and Rogers [35] presented three ways of resistance to EE: producers rejecting investment in it and their fear of losing the audience; shows with other media discussing or promoting negative values; and the reception in some audiences that can use EE messages to reinforce their values. Nonetheless, EE has been expanding due to different factors: social or personal interest of the screenwriter to address a specific issue; the intention to create realistic stories and characters with whom the audience can empathise; or the interest of groups and associations to create EE strategies [37]. This is especially relevant considering that young audiences have a special interest in social issues in fiction [34].

EE strategies are often related to health issues [25] and also linked to other issues present in the SDGs, as is the case of violence [38]. Grady et al. [36] point out that the changes in behavior that EE tries to provoke can be of a personal nature (livelihoods, health, family planning and sexual health, women’s empowerment) and goals linked to being accepted and fitting in regarding social norms.

Additionally, some research has been conducted about the narrative elements that can be relevant for EE to work properly. In these studies, it is worth noting the importance of creating characters who provoke an emotional connection with the audience [37]. On this line, it is worth noting the importance of studies about the link between transmedia and EE [25,37]. In 2018, Lacalle and Sánchez [37] analyzed the transmedia strategies of Spanish TV shows and, while not finding a conversation about social issues promoted by the broadcaster or platform, there was a potential to promote or jeopardize EE strategies on social media. In the case of Spain, the Transmedia Literacy Research Project works by analyzing the cultural competencies and social skills (as interpersonal communication or creating and consuming content) that adolescents are learning out of school with the aim of exploring these forms of online informal learning [20,39].

The theories of social learning and behavior, relevant across disciplines [36], known as the social learning theory, are currently used to study the influence of the audiovisual on the audience, both for the use of EE [35,36,37] and for media reception studies. Applied to media, Grady et al. [36] explain that, according to the social learning theory developed by Bandura [40], for behavior modification to happen, four processes must occur: “attention, retention, reproduction and motivation” (p. 3). For the first two processes to take place, it is necessary for the audience to consume the program, for the messages to be transmitted to have a relevant role in the story (for example, for it to be a main plot or affect a main character) and for the audience to understand the message [36]. For the reproduction process, the audience has to be able to reproduce the behavior [36]. Crespo [41] applied this theory to study the learning process of young people through sexual content in TV series and explains that, by not having real sexual experiences, adolescents learn about sex through observation. This ends up causing “the contents of the media to influence the development of adolescents’ moral judgments, presenting certain behaviors as acceptable or reprehensible, and showing the justifications or sanctions applied to said behaviors” [41] (p. 195).

In addition, it is worth highlighting George Gerbner’s cultivation theory [42], especially used to analyze the effects that television can generate in the youngest people [43,44]. This is still relevant because media (especially television) tend to generate stereotypes and social roles that the viewer could assume as real [43]. Theories that try to explain the needs of the audience for consuming these audiovisual contents, such as the uses and gratifications theory [45], are also noteworthy. Bengtsson, Källquist and Sveningsson [17], when studying the influence of the Skam series on the young Norwegian population, allude to this theory and the need to renew it through these three attributes: interactivity, demassification and asynchronous consumption of text, image and video thanks to the possibility of viewing it at any time [17].

1.2. Digital Teen Series Characteristics

The concept of “teen genre” or “teen series”, especially since the 1990s, includes a set of particular characteristics: their dramatic nature, the focus on a young audience, a duration that changes depending on the teen series and the television channel or platform (with series from 20 to 60 min) and that they tell the story of a teenage main character or a group of characters during high school (15–18 years old) that focuses on their difficulties while starting to become adults and their relationships, such as love and friendship [18,26,46,47,48].

However, several authors have pointed out the need to update the term. First, the very concept of teen series as dramatic fiction has begun to undergo hybridization [26], with international fictions, such as The Vampire Diaries (The CW, 2009–2017) or Shadow and Bones (Netflix, 2021–). In Spain, this trend relates to thrillers, as is the case for fictions such as Inhibidos (PlayZ, 2017), Bajo la Red (PlayZ, 2018–2019), Élite (Netflix, 2018–) [49] and HIT (TVE, 2020–). On the other hand, a change in scenarios can be seen, with the use of locations that differ from “the traditional high school and home” [26] (p. 7) increasing.

Regarding the recurring themes typical of teen fiction, although the new series do not deal with different themes from their predecessors, the approach has changed, seeking an active viewer who is not complacent [50]. Internationally, there have been several teen fiction series in recent years that have become involved in issues that generate social debate [28]. Examples of these teen fictions are Thirteen Reasons Why (Netflix, 2017–2020) [14,29] and Euphoria (HBO, 2019–) [51].

Focusing on Spanish teen fiction, Gelado-Marcos and Puebla-Martínez [50] highlight in Merlí (TV3, 2015–2018) the relevance of topics, such as suicide, motherhood, romantic love and jealousy, ways of dealing with homosexuality in public life or drug use, but again, point out the relevance of analyzing how each of them appear in the plot. Castro [49] also lists the themes that appear in the teen fiction Élite, highlighting “class differences, moral ambiguity, sex, drugs, HIV, corruption, delinquency, homosexuality, masculinity, family, religion, xenophobia and bullying” (p. 151).

Another relevant feature of teen series is their recent transmedia nature, even more so after the success of fictions such as Skam [52], which rethink the concept of “television” and incorporate very different screens and formats [52,53]. Thus, Norwegian public television succeeded in creating, rather than “loyal consumers or audiences”, “engaged (teenage) citizens” with a story [52] (p. 73).

In Spain, its adaptation Skam España (Movistar+, 2018–2020) was the subject of research, such as that of Villén and Ruiz del Olmo [54], who highlight the involvement of the main characters in social movements concerning teenagers. One example is Lucas’ social network, which is his space for reflection, vindication and sexual liberation through symbols and codes that any teenager can understand and identify with [54].

Therefore, the following characteristics of teen series are established: dramatic genre or genre hybridization; treating themes related to social issues; and episodes with a variable duration which tell the story of a young person or a group of high-school age people and their personal relationships and transmedia characters.

RTVE, from 2009, in the process of European public television digitalization, public television series began to present a transmedia strategy, with products that have been the subject of various academic studies, such as Águila Roja (RTVE, 2009–2016) [55] or El Ministerio del Tiempo (RTVE, 2015–) [56,57]. However, it was not until 2017—with the creation of the PlayZ platform—when series began to be adapted to the consumption behavior of young people, which is very different from those of other audiences [22]. This is particularly relevant at a time when RTVE continues to see the relative percentage of viewers between 16 and 24 years of age fall (31.9%), compared to 73.9% of those over 65 [58].

PlayZ was born as an open and free website, with ramifications in multiple social networks dedicated to generating exclusive content focused on a young audience (13 to 24 years old), the age group that spends the least time watching conventional television in Spain but is still a large consumer of audiovisual content [59]. Its offer combines programs developed by influencers, webdocs and teen series with a language, formats and themes appropriate for the youngest audience and the incorporation of influencers in the casts of the programs and series broadcasted [22]. Among the series created by PlayZ are the interactive fiction Si fueras tú (PlayZ, 2017); Inhibidos (PlayZ, 2017) [59]; Bajo la red (PlayZ, 2018–2019), winner of the Golden Globe in the category of best web series at the World Media Festival in Hamburg [21]; or Boca Norte (PlayZ, 2019–).

1.3. Teen Series as a Reflection of Social Change

Although there are many studies on how series influence young audiences [10,11,13,17,41,44,60], there is no study found that investigates the potential for the education of TV series in terms of the SDGs, taking into account the “integrated and indivisible” triangle (economic, social and environmental) referred to by the United Nations [1]. Some studies have been found on the influence of these series on social issues that could be related to specific SDG targets.

Studies on violence (SDG 16) in teen series are focused on the influence that the consumption of television fiction can have on young viewers. Sara González [12] points out that the audience perceives the main character to be a leader when he uses violence as a tool to achieve his goals.

Additionally, studies have been conducted about gender equality (SDG 5), especially when focused on gender roles in teen fiction [22,26,27,61]. Van Damme [62] also shows that social class cannot be disassociated from gender analysis; in more unequal contexts, gender roles increase. This type of research also focuses on sexuality, both in the “sexualized” image of young women on television and in their first sexual experiences [10]. Research on gender stereotypes in romantic relationships in teen series is particularly noteworthy, too [63,64]. In Spain, it is worth noting the study of gender roles in the report promoted by the Asociación de mujeres cineastas y de medios audiovisuales [65]. This study’s sample includes prime-time series, daily TV series and two teen fiction shows: Skam España and Élite. The analysis of the plots presented in the report shows that 74.6% of the scenes in which women appear in teen series are related to love or caring for men, a much higher figure than in prime-time (57.8%) or daily series (66.3%) [65].

There is also research on the presence of themes related to SDG 10 (reducing inequalities), which includes in its second target to “empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status” [1] (p. 13).

In fact, teen series have stood out for years for their representation of the LGTBIQ community [66,67,68,69,70,71]. Thus, Tropiano [68] points out that these series are references in which characters related to the LGTBIQ community are integrated into a series without their homosexuality being the axis of their story (something that did not happen in the rest of the fiction genres). Recently, the importance of Sex Education (Netflix, 2019–) has been highlighted due to the diversity of its characters in terms of sexual orientation [66,69].

Meanwhile, Daniel Ferrera [70] establishes an analysis of European teenage characters and their nationalities. Ferrera [70] points out the increasing representation of multiculturalism due to the global migratory context. In Spain, only 6.4% of series’ characters are racialized and they appear concentrated in some series, such as the teen show Élite [71].

There is also an increasing number of TV series (and teen series) that include stories about characters with illnesses (SDG 3), especially mental health issues. Through an analysis of fiction series, such as Euphoria [69], Atypical (Netflix, 2017–2021) and Thirteen Reasons Why, Raya, Sánchez-Labella and Durán [14] discuss the inclusion of characters with serious psychological issues and the inclusion of characters that reflect social inequalities, avoiding one-dimensional and stereotypical characters. There is also a special interest in the corporal self-perception of the characters, especially female ones. In this line, Maes and Vandenbosch [72] point out the importance of studying positive and negative body messages in teen series. In Skam España, there is a character with borderline disorder [65]; HIT includes a teenager with a self-injury disorder in its first season and a teenager with obsessive–compulsive disorder in its second season; and Élite includes a girl with AIDS.

Target 3.5 is included in the third SDG, which states the importance of preventing and treating the abuse of alcohol and other harmful substances. In international teen series such as Euphoria [51], stories about drugs and alcohol consumption are becoming more relevant. In Spain, in fictions such as Élite, there are plenty of scenes of parties, celebrations and moments in which drugs and alcohol are a constant feature [34].

Despite all these articles and studies, no research has been found that approaches these topics from a holistic analysis of the presence of the SDGs in the narrative of TV series, nor on how Spanish series do so. Such a study would require an appropriate methodology to make this task easier. This paper proposes an analytical tool to facilitate this broader and more comprehensive perspective of the main social problems set out by the UN, as well as its application to RTVE series, a public broadcasting corporation that is committed to young people and the 2030 Agenda.

2. Materials and Methods

For this study, an analysis tool was developed. This tool has undergone a double evaluation process: first, intercoder reliability and, second, a practical application in a content analysis of an RTVE digital teen series, Boca Norte.

2.1. Development of the Analysis Tool

The development of the analysis framework followed a two-phase procedure [73]: one of isolation and selection of the variables for analysis and the other of grouping. The theoretical basis for choosing the variables is the narrative theories of Casetti and di Chio [74], which are used in many investigations that apply content analysis to television series from generalist channels [75], television series and LGTBIQ collective [76], representation of romantic relationships in teen series [77], new masculinities in fiction [78], gender perspective in the analysis of fiction [79] or construction of young characters [14,75].

Therefore, it was assumed that a story can be divided into three narratological elements or categories [74]: the “events”, that is, what happens; the “existings”, to whom these events happen (which could be defined by the “characters” and the “environment” in which they find themselves); and the “transformations”, the changes in the situation that modify the initial state of the story.

In addition to the narratological categories of Casetti and di Chio [74], for this first version of the template, groups of variables, variables and categories elaborated in other audiovisual content analysis templates were considered, as well as relevant issues that were discussed in the theoretical framework. All the groups of variables are presented below (7 in this first version of the template).

The first group of variables was “Sustainable Development Goals”, where the goals that appear in the analyzed episode and the targets were added. Furthermore, the group of variables “frequency” was established, which has been studied in different investigations related to the analysis of audiovisual fiction content [80,81]. “type of manifestation” was also included to study the type of appearance of the themes aligned with the 2030 Agenda (visual, verbal, part of the plots) and their relevance in the story [12].

Additionally, as previously stated, Casetti and di Chio’s narratological triad [74] was included. Therefore, the group of variables “events” was added, that is, what happens in fiction, which would be especially useful to identify the presence of the SDGs in teen series (in fact, the qualitative variable “description of the event” to evaluate how these themes are inserted). The “existings” group was also added. In this group of variables, the characters were analyzed. This is a frequent element in the content analysis of television series. In recent years, studies related to the creation of stereotypes stand out [26,82] as an analysis of new masculinities [83]; development of characters with mental disorders in teen series [14]; or in an analysis of the adolescent character in European serial fiction [70]. For this analysis template, the contributions of the Research Team in Media Analysis, Images and Audiovisual Stories of the University of Seville (AdMIRA), which has been used in various investigations on audiovisual fiction and characters [14,76,78,83], have been simplified, creating qualitative description variables and the variable “character as role” (explained in Appendix C, Table A2).

The environment in which the action takes place (whether it is public or private) acts as a variable in research related to issues of the 2030 Agenda such as violence [12] or gender equality; for issues such as the actions of women, they continue to develop only in a private space in fiction [28]. Therefore, two categories (public/private) were created to analyze the scope in which a narrative related to an SDG-related issue takes place (described in Appendix C, Table A3). In addition, the variable “type of space” was created based on the research of Fedele [18,84] to develop a content analysis on the representation of young people in teen series (explained in Appendix C, Table A4).

The third element of Casetti and di Chio’s narratological triad is transformations, that is, actions or events that cause variations in the initial situation, generating a break with the previous state. These changes can be interpreted as processes (variable “transformations as processes”) that cause modifications in the environment, being able to improve it, worsen it or even leave it in the same situation for the characters that carry out the action [74].

Finally, the group of variables “transmedia expansion channels” was added, in which the categories were created from a bibliographic review [17,54,55,85,86,87,88].

The first version of the analysis tool can be seen in Appendix A.

2.2. Intercoder Reliability

Once the first draft for the analysis tool was finished (this first version is presented in Appendix A), it was submitted to intercoder reliability. These experts provided information, evidence, judgments and evaluations for the tool [89]. The information gathering process was systematized with the use of a template sent in an evaluation document. The experts were asked to point out the relevance of the groups of variables, variables and categories, as well as their observations individually. In addition to the relevance of the variables of the tool, a series of general questions were included. Subsequently, categories and variables were eliminated, reformulated, reassigned or included. The final version of the analysis tool is presented in Table A2.

2.3. Content Analysis

Once the intercoder reliability phase was completed, the second version of the tool was used in a content analysis. To carry out this content analysis, the SDGs were taken as the unit of analysis. Thus, this tool was applied to each of the SDGs, assessing the presence of each of them in the sample.

To carry out the content analysis, each episode of the series was studied separately, to analyze the presence of the SDGs in a complete plot arc (an example of the final coded template is shown in Appendix B). In addition, the results were compared with those of the total season to establish overall results for the series. It is important to point out that as analysis content, a chapter was understood as the entire story related to an episode in a traditional way and its transmedia expansion.

Two types of variables were created:

- Those that require a qualitative description.

- Those that are coded through categories. For this type of variable, the definitions of the categories that can be selected in the final analysis template (Table A2) are presented in Appendix C.

In addition, as will be explained in the “Results” section, in the group of “events” variables and in the spaces (within the group of “existings” variables), the timing was added transversally. Thus, it was possible to quantitatively analyze and compare the presence of themes aligned with the 2030 Agenda in the different stories and environments. From the sum of “events” related to an SDG, it was possible to measure the timing of each SDG in the series. It should be noted that an event can respond to several SDGs (for example, a situation of gender violence responds to SDGs 5 and 16). In these cases, it was decided to include these minutes in both.

2.4. Sample Selection

As a sample for this first approximation of the implementation of the analysis template, an RTVE digital teen series broadcast on PlayZ was selected: Boca Norte. This teen series shows the story of Andrea, a teenager from a privileged neighborhood in Barcelona who moves to a poorer area after a conflict event. Her father forces her to join a youth center in the area, where she meets a group of other teenagers with whom she will set up a dance club and who change her life. Boca Norte has a season with six episodes (in Appendix D, the synopsis of each episode is added). This fiction is interesting as a sample because PlayZ is the platform that is committed to creating young content on RTVE (the Spanish public television) and Boca Norte is one of the most current transmedia series developed by the platform.

This fiction was awarded, in 2019, the Ondas award for best digital broadcasting content due to its social media strategy [90]. Boca Norte provided additional content to the series through creating social media profiles for its characters. In addition, this show stood out because several Spanish trap artists composed songs that can only be heard completely on Boca Norte’s social media channels [90].

As explained in the theoretical framework, Boca Norte is a teen series because it is a dramatic fiction, it deals with social issues such as equality, poverty or bullying, their main characters are a group of teenagers in their high-school days, its main plots are related to personal development or their romantic and friendship relationships, and it has a strong transmedia strategy [91]. In addition, Boca Norte was defined by RTVE [91] as a “feminist series that deals with issues, such as bisexuality, capitalism, the clash of cultures, dependence on social networks, addiction to pornography and virginity”. This pitch included topics that are present in the Sustainable Development Goals. This is why this digital teen series is a good starting point for the evaluation of the analysis tool.

The fiction was created by Eva Mor, director of development and innovation at Lavinia Audiovisual (the production company of the series) at the time of Boca Norte’s creation [92]. The series is directed by Dani de la Orden, who had previous experience in teen fiction, such as Élite, and Elena Trapé, who had just been awarded Best Film at the Málaga Film Festival for Las Distancias [92]. The series features actors who were already recognized by young Spaniards, such as David Solans, previously in the successful teen series Merlí, and Guillermo Campra, actor in Águila Roja and Bajo la Red [87].

3. Results

The results of the study can be divided into two groups. On the one hand, the results obtained after expert evaluation, which resulted in the final analysis template, will be presented. On the other hand, the results obtained from the application of the tool to the analysis of the Boca Norte series are discussed.

3.1. Intercoder Reliability Results

From the proposal to 10 experts, 7 agreed to answer. The following table presents their area of research and the universities where they were working at the time of the intercoder reliability (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intercoder reliability experts.

All the experts confirmed the relevance, innovative character and usefulness of the proposed analysis tool, especially for public television TV series development (experts 1 and 2). All experts agreed on its practical application. A total of 71.45% of the experts consulted considered that the elements were understandable, appropriate and clear. However, two of the groups of variables proposed in the methodology were eliminated due to the recommendations received in the intercoder reliability (see the initial template in Appendix A).

On the one hand, the group of variables “frequency” was eliminated (five out of the seven experts recommended its elimination or reconsideration). The variables included were considered “redundant” (expert 7) and calculable from those already presented. The “timing” variable, which appeared within this group, was reconsidered and it was decided to work by counting the minutes that some events or elements lasted transversally to different variables (in Table 2 the recommended ones to analyze with “timing” are presented with an asterisk).

Table 2.

Tool of analysis.

On the other hand, even though the group of variables “type of manifestation” was evaluated as pertinent, it was decided to eliminate it for two reasons. First, because, as experts 4 and 7 pointed out, it mixed categories related to narrative presence (main plot, secondary plot) with others more related to manifestation (visual, verbal). On the other hand, four out of the seven experts questioned the need to include this group of variables, since the narrative presence of these SDGs could be measured from the analysis carried out with the rest of the template variables.

Regarding the groups of variables that are maintained, it should be noted that 85.71% of the experts explicitly indicated that one of the reasons why this template is innovative is due to including the SDGs in the analysis template. In fact, expert 5 added that “the proposal can be described as innovative when addressing an emerging and relevant topic like this one”.

All the experts described the events’ group of variables as “very pertinent”. However, they considered it advisable to reformulate the variables and add the standardized classification of the most common actions that the characters carry out in the stories elaborated by Casetti and di Chio [74] (explained in Appendix C, Table A1). In total, 100% of the experts have assessed the group of “existings” variables as “very pertinent”. However, four of the seven pointed out that the variables should be more developed in the analysis template, so that it would be more replicable. It was proposed to consult Sánchez-Noriega [93] to establish the classification of characters. In addition, work has been undertaken based on the studies by Aguado and Martínez [94] and Alonso [95]. The environments have been valued positively by most of the experts (85.71%), but expert 7 pointed out the need to incorporate the timing when studying the environments.

Finally, the group of “transformation” variables has been reconsidered, renamed “functions”. These functions were based on Bremond’s [96] logic, in which the functions (understood as those basic units of narrative language) are integrated into a unit called sequence. These sequences can be divided into three parts (opening, development and closure). This tool includes the opening function (explained in Appendix C, Table A5), studied through the classification of origins by García-Muñoz and Fedele [30], and the closing function (described in Appendix C, Table A6), understood as the transformations by Casetti and di Chio [74]. This is relevant because media research has shown that audiences follow the characters’ goals and motivations during the viewing experience [97].

After working with the recommendations proposed by the experts, the tool (Table 2) and the definition of the groups of variables are presented.

With the remaining tool, a content analysis was conducted on the RTVE teen series, Boca Norte. This could lead to further modifications and an improvement in the template.

3.2. Content Analysis Results

As has been explained, the chosen TV series for this content analysis is Boca Norte. Its relationship with different issues included in the 2030 Agenda, its classification as a teen series and its transmedia approach and design have led this study to choose this show as the sample.

3.2.1. Sustainable Development Goals

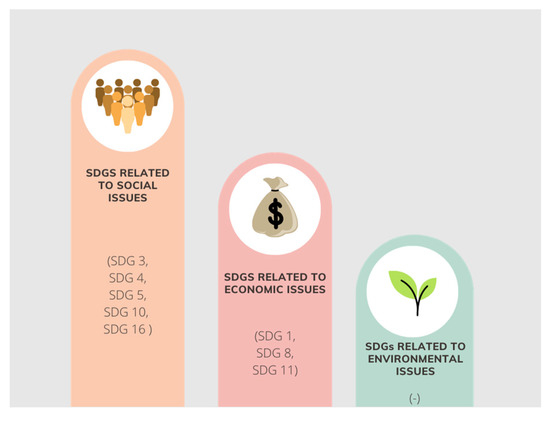

A total of eight SDGs are represented in Boca Norte (Figure 1). The most repeated SDG-related issues were connected to social issues (good health and well-being, gender equality, reduced inequalities and peace, justice and strong institutions). In addition, there were some economic agenda issues (poverty and job training). However, there was no reference to environmental issues.

Figure 1.

Representation of the three axes of sustainable development in Boca Norte.

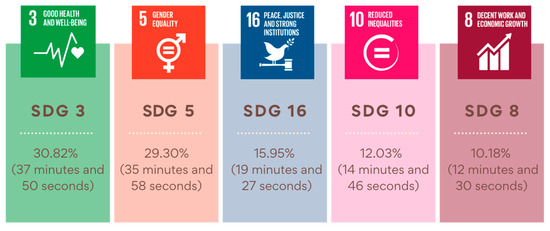

3.2.2. Events

Events (Figure 2) representing SDG issues related to health (sexuality education, substance abuse, mental health) and gender equality are the most represented in Boca Norte (30.82% and 29.30% of the time of the show related to any SDG). In addition, issues connected to violence and inequality are also strongly represented in the series (15.95% and 12.03%, respectively).

Figure 2.

The five SDGs most represented in Boca Norte.

The events related to the SDG have similar functions in the plot: there is a “deprivation” or “alienation” (Andrea from her friends in the privileged neighborhood, Katy from her social position in the group, Lu from his reputation as a womanizer) that leads to a personal and social closure (if any) and “making amends” (Andrea changes her attitude, confronts Carol and wins back her friends; Katy confesses pouring drugs in Andrea’s drink and everyone forgives her; Lu apologizes to Maria and realizes his problem with pornography).

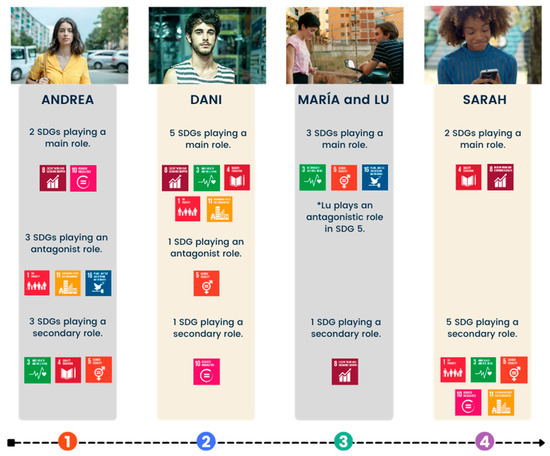

3.2.3. Existings

A total of 37.5% of the characters involved in SDG-related issues were men (Dani, Lu and Andy) and 62.5% were women (Andrea, Katy, Sarah and Maria). Furthermore, except for Dani, who has just turned 19, all of them are approximately 17 years old and are finishing their studies. The main characters of Boca Norte comply with the canons of beauty, although 40% of the girls do not feel comfortable with their bodies and show insecurities in this regard. None of the male protagonists have such personal conflicts.

Each of the characters dresses according to the personal features attributed to them in the series. Comparing the above descriptions of the characters with the report “Estereotipos, roles y relaciones de género en series de televisión de producción nacional: un análisis sociológico” [65], it can be seen how María would fulfil the role of “good girl” (she wears baggy and inconspicuous clothes), Katy of “femme fatale” (she wears tight clothes), Dani that of “hero” or Lu that of “rebel boy” (long hair, wide T-shirts, DJ earphones).

The most involved characters in plots including issues related to the 2030 Agenda are Andrea and Dani, followed by Lu and María (Figure 3). The relationships between the characters generate narratives in which they respond to a social function (Sarah and Andy, close friends, are involved in the same SDGs; the same happens with Lu and María). In the case of Andrea and Dani, this tendency is not so clear, probably because, as the main characters of the series, the show focuses on their personal stories (Dani living in Boca Norte and Andrea’s life before arriving in Boca Norte).

Figure 3.

Character roles in plots connected to issues related to the 2030 Agenda.

Meanwhile, in the roles characters play on in the themes related to the 2030 Agenda, there are groupings of different behaviors during the season. On the one hand, Andy and Sarah are the only characters who are linked to SDG issues because of their awareness. This makes them play an “active”, “influencing” and “modifying” role in the situation (the girls in the neighborhood and, for example, their sexuality). Other characters are involved in issues related to the SDGs that directly and personally affect them (in Andrea’s case, her social prejudices, the suit she faces for bullying; in Dani’s case, he does not want his friends to know about his squatting situation) and in which they undergo an evolution during the season, going from taking “passive” to “active” roles when they begin to realize their mistakes and modify their initial situation. Katy (in the first episodes with an “active” and “influential” role) tries desperately to make her relationship with Dani work and plays a much more “passive” role toward him (as the series goes on, she shows that she does not like this).

In relation to the environment (Figure 4), it is worth noting the importance of the Boca Norte youth center in the series, with most of the narratives taking place there (62.99%). Regarding SDGs 3 and 16, the importance of the private sphere in issues of sexuality, consumption and mental health is represented (SDG 3), 22.07% of which takes place at home. In the case of violence (SDG 16), more conversations and reactions arise in the private sphere, but harassment takes place in the public sphere.

Figure 4.

Time that plots related to SDG issues are developed in the public sphere.

3.2.4. Functions

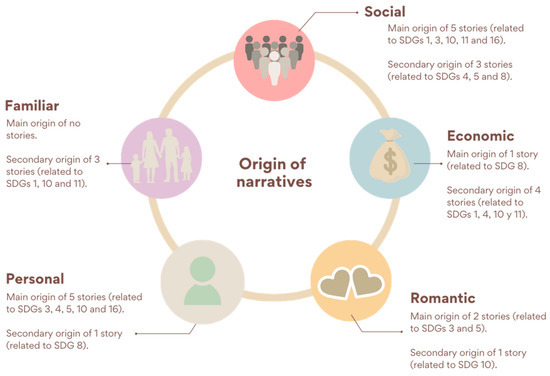

The importance of the “group” and the teenagers’ sense of belonging (both in fiction and in real life) make social relationships the origin (Figure 5), to a greater or lesser extent, of all the issues related to the 2030 Agenda in the TV series. Romance is a catalyst for problems in personal perception (SDG 3) and for issues related to gender equality (SDG 5). In addition, the characters are at a stage of personal development, which, although it may not at first seem to be one of the main origins of the plots that follow, becomes evident over the course of the season.

Figure 5.

Origin of the narratives in which SDGs are present.

In contrast, family and economic issues trigger few narratives and, when they do, they are more ancillary to a social origin than the true cause of the actions. Most of the actions related to SDGs 1 and 11 have a social origin (Dani does not want anyone to know where he lives), and only one has a family origin (Dani sends money to his mother so she can pay her rent). The plots related to this SDG do not seek an improvement in the situation but reflect the boy’s fear of a worsening of the situation from the social sphere, i.e., that his friends will find out.

The transformations undergone by the characters in Boca Norte are closely related to the scope of the issues included in the SDG. The plots linked to economic issues (SDG 1, 8 and 11) find closure in the show. However, most of the characters who suffer from social issues connected to the 2030 Agenda (SDGs 3, 5 and 16) do not experience any personal or social transformation.

It is worth noting that Katy’s situation worsened through the series because of jealousy (romantic or social origin) and her insecurity (personal origin), but the negative consequences of her actions never occurred. Therefore, the fiction does not explore the consequences of common teenage issues, such as Katy’s alcohol and drug addiction and her physical complex.

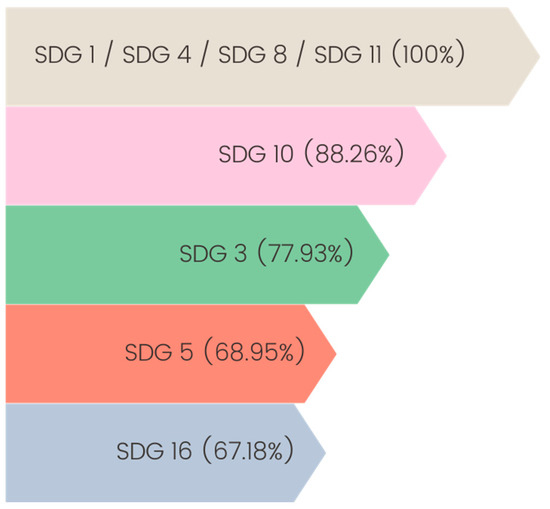

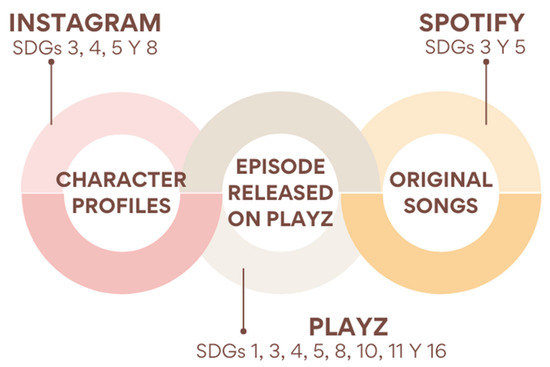

3.2.5. Transmedia Expansion Channels

Boca Norte expands transmedially through the Instagram profiles of the main characters and the songs composed for the fiction by Spanish artists on the series’ Spotify profile (Figure 6). The transmedia expansion does not include new stories, but it does complement the events in which some of the 2030 Agenda’s issues are present.

Figure 6.

Transmedia expansion channels and the SDGs they refer to.

On Spotify, issues related to SDGs 3 and 5 are present in very different ways. Some lyrics are about empowerment, and others are about how “cool” consuming drugs is.

Boca Norte includes the Instagram profiles of the seven main characters and Andrea’s friend Carol. These profiles are used to upload stories and posts that complement events related to the 2030 Agenda already presented in the episode. One example is Dani’s case; there is an emotional attachment to the youth center and the absence of content related to his situation as a squatter (SDGs 1 and 11 are the only ones present in the series, but not in the transmedia, thus making reference to the fact that Dani is afraid that the group will find out about his situation and hides it in their profiles). In his profile, he uploads the schedules of activities that take place in Boca Norte, an issue that is related to SDGs 4 and 8. This gives more prominence to issues related to SDGs, which do not have as much presence in the series (SDG 4 has a representation over time of 3.03%, but we can see it on social media).

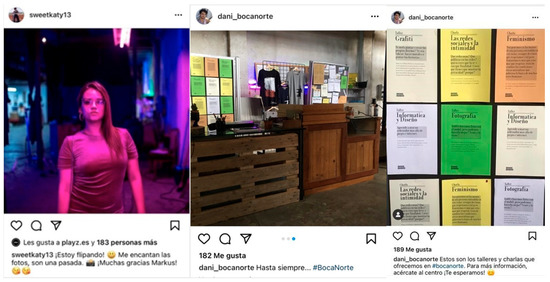

On the other hand, trends that can already be seen in the episodes of the series are reinforced on Instagram. For example, Katy shows her substance abuse and self-perception problems on her social media, going to parties, taking drugs or posing as if she was more of an adult than she is. Although this is new information, it does not have any consequence for the fictional story, so they are trivial for followers (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Katy (@sweetkaty13) and Dani (@dani_bocanorte) Instagram profiles.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to develop a methodological tool that would allow for analyzing the presence of the SDGs in the narratives of teen series and applying it to a Spanish public television series, due to RTVE’s commitment to the 2030 Agenda and toward young people. The design of the proposed analysis tool and its testing offer initial evidence on how this commitment and its educational potential are addressed. Based on the results obtained, the following conclusions are presented below.

The intercoder reliability allowed, on one side, for confirming the interest and innovative character of the template. Additionally, the practical applicability of the template both to analyze other content and for the development of audiovisual fiction was confirmed. To facilitate the replicability of the tool and following the advice of the experts, some variable groups were deleted and others were more developed. It is worth noting that the elimination of the variable groups “frequency” and “type of manifestation” were useful because both have been measured through the other variables and included the timing transversally in the pointed variables (also a recommendation of the intercoder reliability). Most of the content templates are useful to measure specific social issues, such as gender representation [79,82,83] or LGTBIQ collective [76,78], and, in many cases, taking fictional characters as a unit of analysis [14,78,82], due to their great relevance in the story and their power of influence on the viewer [37]. This template has tried to simplify analysis such as that of the characters, with the aim of being able to globally measure the presence of each of the SDGs in the narrative of a TV series.

For the pilot test, a public television series (RTVE) was chosen, specifically, one from the youth platform PlayZ, which has an approach toward young audiences [22]. Additionally, RTVE has a public commitment toward the SDGs as a public broadcaster [21]. Boca Norte was chosen because it complies with the characteristics of a teen series set in the theoretical framework. Including the “SDGs” as a unit of analysis allows for establishing a clearer perception of which issues related to the 2030 Agenda are present in the teen series. Boca Norte presents eight SDGs. Those with the highest number of appearances are social, followed by economic. There are no issues related to the environment in Boca Norte, which is also the case in the national and international academic literature on teen series, with a focus mainly on issues related to violence [12], gender [10,26,62,65], reduction in inequalities [66,70,76], health and consumption [14,29]. This analysis has enabled an approach toward social aspects as the relationship between gender and class issues, according to authors such as Van Damme [62], cannot be separated.

The other groups of variables that make up the tool build an overview of how the SDGs are presented in the narrative. The “events” make it possible to identify and quantify how the issues related to the SDGs are represented in the series, as well as to compare this representation with real situations. Some of the events that take more time in Boca Norte related to issues linked with the SDGs which are frequent in teen series, as is the case of body self-perception, alcohol consumption, bullying, sex, ways of approaching sexuality, love or jealousy [10,49,72]. However, there are other topics, such as those linked with the LGTBIQ collective, that are still secondary in relevance and very linked to “coming out”. In actual teen series, this has stopped being the axis of many character stories from the collective [68] and, when it does work as an axis, as is the case in Sex Education, it is to create a deeper exploration of the sexualities of the main character [66]. The simplification of these topics in Boca Norte may be a consequence of its short duration (6 episodes of 20 min), as the development of less stereotyped characters in shows such as Sex Education is more significant from the second season on [60]. In Boca Norte, the events linked to issues present in the SDGs do not have the intention of representing a reality. The intention is to represent the series’ context of the plots and narratives. This is especially interesting if it is linked with research about the interventions related with entertainment-education and behavioral theories such as Bandura’s that currently support them, because the more reality is perceived by the audience, the bigger the impact of the series is on them [25].

The variables and categories grouped In the “existings” variable show patterns of behavior and relationships of the characters, making them easier to compare with stereotypes already present in fiction. In Boca Norte, stereotypes and gender roles are reproduced (especially in romantic relationships), and characters (especially female characters) with self-perception problems are represented. Characters are one of the most influential elements on the audience because they can create a connection and empathy in the spectator [37]. In teen series, this is especially relevant because young people are involved in a process of identity building [30] and the creation of stereotypes can affect the way young viewers perceive social reality [43]. In fact, studies on stereotypes, especially on gender, are relevant nowadays in the academic literature [10,26,28,82].

In the case of “environments”, it is not clear from this test what data of interest these variables provide, since in Boca Norte, the youth center is very relevant. As seen in the definitions of teen series, these do not usually have many locations. However, if the trend shown by the series is repeated, it could be affirmed that teen series deal with issues typical of the private sphere (sexuality, consumption, harassment) in the public sphere. However, it is still more frequent to represent girls performing these types of actions in the private sphere (Katy vomits to lose weight and drinks alone; in fact, she is rejected for trying to have sex with her partner in the public sphere), than male characters in the fiction. This concurs with the analyzed literature, where authors such as Gil-Quintana and Gil-Tévar [28] point out that one of the main problems of gender representation is the private and public use of spaces.

The group of variables “functions” explains the motivations of the characters to carry out actions linked to the 2030 Agenda and, in turn, their consequences. The main characters of Boca Norte have social conflicts. Economic issues linked to the SDGs are superficial or secondary, limiting the situation shown in the series and, therefore, the educational ability that these stories could have. Only Dani (main male character) has economic problems. The actions with romantic origins are linked to the main female characters. This concurs with the studies about gender in Spain, where most scenes with the participation of female characters in teen series are linked with a romantic origin [65]. On “transformations”, the dramatic nature of teen series and their plots of personal and social discovery [18,47,48] lead to the Boca Norte’s characters making mistakes. When this happens in this teen series in a narrative related to the 2030 Agenda, either nothing happens (the character is not aware of the mistake) or, if the character regrets it (the action is shown to be negative), their previous behavior does not lead to a worsening of their situation. This makes the consequences of the usual problems of this age (bullying, substance abuse, pornography consumption) to be underrepresented.

Despite social networks being used in teen series to introduce new stories or deepen issues, as in the case of Skam and Skam España [17,52,54], this is not the case in Boca Norte, where the narrative of the episode and of the “transmedia expansion channels” are the same (there are no new “events”, “origins” or “transformations” of the stories in its transmedia). Boca Norte’s social media are not used as a means to educate on social issues as other teen series such as Skam España or East Los High do [25,54]. This could be of great interest, according to authors such as Lacalle and Sánchez [37], as social media and transmedia could facilitate educational strategies about these kinds of topics. However, actual teen series’ trends could be observed, as is the case of Katy and the sexualization of female characters [10]. It would be interesting to study the relationship of the incorporation of new narratives in transmedia with the impact and reach of these social profiles.

5. Conclusions

The content analysis of Boca Norte with the tool presented allows for measuring how this show is involved in the process of change advocated by the SDGs, in which education plays a leading role [3,4]. If television series are understood, especially those developed for young people, as an educational tool [11], which is also highly consumed by teenagers at a key moment in their development [30,34], this tool is useful to study what the audience is consuming related to topics present in the SDGs. This allows for analyzing to what extent the audiovisual industry is creating content focused on integrating these topics in teen series, given the proven educational potential. This is even more necessary in the analysis of RTVE’s content, as it is a public service broadcaster. As proposed by some experts, this template and the analyses it provides, could be useful in the development of future TV series as a basis for assessing the presence of the issues covered by the SDGs.

In the content analysis, most of the variables are replicable (this has been confirmed by the intercoder reliability and through the pilot test). Nonetheless, this study has a series of limitations that are listed below. Firstly, the variable “type of event” and its categories happened to be ambiguous in the test, so it would be recommendable to modify it for future applications of the tool. Additionally, there is room for improvement by amplifying the group of variables “transmedia expansion channels” and not analyzing exclusively the narratives of the transmedia strategy. It would still be interesting to study the social media of actors who perform in the series and their social awareness, as well as the users’ reactions. This would be an intervention more linked to the study of the educational impact but would help to measure the success of the transmedia strategy.

Thirdly, in this pilot test, just one series has been selected for the content analysis. Boca Norte is a fiction on PlayZ (because of the public commitment of RTVE, pointed out before) linked to issues presented in the 2030 Agenda [92]. Nonetheless, we cannot obtain conclusions representative of the general environment. However, this article has the aim of creating a template for the analysis and evaluation of the presence of SDGs in teen series. In fact, one of the implications of this research is to present an approach linked to sustainable development (holistically understood including environmental, social and economic development) in the analysis of audiovisual narratives (the experts consulted pointed out that this template is replicable for other areas of this discipline). This way, we wanted to outline new research areas through the content analysis that would allow for, among others, evaluating the presence of the 2030 Agenda in TV series. This could be used to compare the role of public and private television on the diffusion of messages linked to the SDGs (applying the template to series from different broadcasters and platforms) or to study the role of public television in different countries. This could be reinforced with in-depth interviews with professionals from the audiovisual industry to obtain insights into how the process of insertion (if existing) of the themes is included in the 2030 Agenda.

Finally, it is worth noting that this tool is useful for measuring the presence of the SDGs in teen series, but not for measuring the educational potential of these fictions on young people. However, some communication theories pointed out in the theoretical framework, such as the social learning theory of Bandura [40], that is still used in studies on media education, indicate that the learning process through the consumption of audiovisual content starts with observation [36]. This stresses the need for a tool, such as the one presented in this article, which is useful for later studying issues linked with its educational impact. This way, it would be of great interest for future research to design interventions to evaluate the potential influence of teen series (and the variables presented in the tool) on young people.

On the other hand, the strategies of entertainment-education come from the design of entertainment content (in this case, TV series) that allow for educating on socially relevant issues (as is the case of the SDGs). This template for analysis could be used as a tool for creators when developing TV series. In fact, this template could be used by screenwriters for building the character development and their episodic plots or through a whole season (from the origin of the plot to the ending and transformations). This would allow for evaluating in the writing process how each SDG is being integrated in the TV series (as a unit of analysis) and how the social, economic and environmental aspects of the 2030 Agenda are being treated. This idea is supported by the experts’ review, where expert 1 talks about the possibility of “building a new template for the TV programming around these concepts”. On the same line, there is the importance of transmedia strategies, which are interesting for young people [34,52,54] and which some authors point out are a means of entertainment-education of great importance nowadays [25,37].

Research on TV series is becoming more relevant, especially considering that it is only seven years until the deadline established for the fulfilment of the 2030 Agenda and transformative education is necessary to achieve its goals. Television producers, especially public producers, must be aware of their impact and how to include relevant social, economic and environmental issues in their fiction, which is why research on this matter is increasingly relevant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V.-M.; J.L.D. and R.A.A.-P.; methodology S.V.-M.; J.L.D. and R.A.A.-P.; formal analysis, S.V.-M., J.L.D. and R.A.A.-P.; investigation, S.V.-M.; J.L.D. and R.A.A.-P.; resources, S.V.-M.; J.L.D. and R.A.A.-P.; data curation, S.V.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.V.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.L.D. and R.A.A.-P.; visualization, S.V.-M.; supervision, J.L.D. and R.A.A.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. First Analysis Template Proposal

| Group of Variables | Coding/Qualitative Description |

| Sustainable Development Goals |

|

| Frequency |

|

| Type of manifestation | Type of manifestation: visual (1), verbal (2), main plot (3), subplot (4) |

| Events |

|

| Existings |

|

| Transformations |

|

| Transmedia expansion channels |

|

Appendix B

Example of the final coded template. This table shows the events related to target 3.7. (of SDG 3) in episode 1 of Boca Norte.

| Category/Qualitative Description | Timing | |

| SDGs | ||

| SDG | SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. | |

| SDG representation justification | In this case, this event is linked to the target related to sexual health: Katy had not taken precautions by having sex with Dani and she missed her menstruation. | |

| Target | 3.7. By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services, including for family planning, information and education and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programs. | |

| Events | 212 min | |

| Qualitative description of the event | Katy missed her menstruation. Dani is worried about it/Katy tests negative for pregnancy/Katy tries to have sex with Dani without protection, Dani rejects her. | 05:40–06:10/07:27–09:10/20:09–21:28 |

| Action as function: deprivation (1)/removal (2)/travel (3)/prohibition (4)/obligation (5)/deception (6)/preliminary test (7)/definitive test (8)/fault reparation (9)/returning (10)/celebration (11). | 1/8/2 | |

| Existings | ||

| Characters | ||

| Qualitative description of the character as a person: physical description (sex, age, race, appearance) and characterisation (make-up and costume). | Table attached below. | |

| Qualitative description of the character as a person: psychological description (behavior, personality traits, dreams concerns, values). | Table attached below. | |

| Qualitative description of their social and environmental relations. | Table attached below. | |

| Character as a role: active (1)/passive (2) | Katy (2)/Dani (2) | |

| Character as a role: influencer (1)/autonomous (2) | Katy (1)/Dani (1) | |

| Character as a role: modifier (1)/conservative (2) | Katy (2)/Dani (2) | |

| Character as a role: main character (1)/secondary (2)/antagonist (3) | Katy (1)/Dani (1) | |

| Environments | ||

| Sphere | ||

| Private sphere: yes (1)/no (2) | 1 | 20:09–21:28 |

| Public sphere: yes (1)/no (2) | 1 | 05:40–06:10/07:27–09:10 |

| Type of space: | ||

| Domestic spaces: yes (1)/no (2) | 1 | 20:09–21:28 |

| Educational centers: yes (1)/no (2) | 1 | 05:40–06:10/07:27–09:10 |

| Workplaces: yes (1)/no (2) | 2 | |

| Leisure places: yes (1)/no (2) | 2 | |

| Public space: yes (1)/no (2) | 2 | |

| Other spaces: yes (1)/no (2) | 2 | |

| Functions | ||

| Opening phase: Origin: social (1)/personal (2)/family (3)/love (4)/economical (5). | 4 | |

| Closing phase. Qualitative description of the transformation process. | Dani refuses to have sex with Katy. She feels bad and they are about to break up. | |

| Closing phase. Result achieved: improvement (1)/worsening (2)/neutral (3). | 2 | |

| Transmedia expansion channels | ||

| Transmedia expansion channels: TV or VOD platform (1)/Instagram (2)/TikTok (3)/Twitter (4)/Facebook (5)/WhatsApp (6)/YouTube (7)/Spotify (8)/other social networks (9)/website (10)/events (11)/books (12)/other media (13) | 1 |

| CHARACTER AS A PERSON “DANI” | |

| Qualitative description of the character as a person: physical description (sex, age, race, appearance) and characterization (make-up and costume). | Boy around 19 years old (he just finished high school). He dresses in casual clothes and sometimes even old clothes, but always clean. |

| Qualitative description of the character as a person: psychological description (behavior, personality traits, dreams concerns, values). | He is a serious and responsible guy. He admits to being fed up with living “worried about the others”. He is in charge of coordinating the Boca Norte youth center and he loves his job. In fact, his Instagram profile’s description is “the center first”. |

| Qualitative description of their social and environmental relations. | Dani lives really conditioned by his relationship with his mother; he had to quit studying and living in the youth center for her to be able to pay her rent. We do not know anything about his family or origins, just that he used to live as a resident in a shelter when he was a kid. He was in a relationship with Katy but when Andrea arrives, he breaks up with Katy and starts dating Andrea. |

| CHARACTER AS A PERSON “KATY” | |

| Qualitative description of the character as a person: physical description (sex, age, race, appearance) and characterization (make-up and costume). | Girl around 16 years old. She likes to be noticed and dresses in close-fitting clothes with flashy colors. She also always wears make-up with strong colors (especially her lips). She is thin, but not as much as this kind of character tends to be. |

| Qualitative description of the character as a person: psychological description (behavior, personality traits, dreams concerns, values). | She likes to be noticed, but she is tremendously insecure. She is addicted to social media. She hides behind alcohol, drugs, having sex with adults and even in the last episode she is seen provoking her vomit because of physical insecurity. She seeks to feel adult. |

| Qualitative description of their social and environmental relations. | Everybody in Boca Norte looks at her, except Dani, by whom she feels judged. However, when Andrea arrives, she feels out of place and behaves impulsively toward her. We do not know anything about her family or origins. |

Appendix C. Definition of Each of the Categories of the Analysis Template

Group of variables 2: Events

Table A1.

Action as a function.

Table A1.

Action as a function.

| Action as a Function | |

|---|---|

| Deprivation | Something or somebody removes something that the character appreciates. |

| Removal | The character puts distance to his or her place of origin. It can include a way to a possible solution. |

| Travel | Physical or psychological trip that a character takes to move through different phases. |

| Prohibition | It is the presentation or confirmation of the limits the character cannot overtake. It could be assumed (respect) or not (infraction). |

| Obligation | It introduces the duty of a character toward a task or a mission. Can carry it out (compliance) or not (avoidance). |

| Deception | The character is induced to think something which is not true. The character can be convinced (tolerance) or not (unmasking). |

| Preliminary test | The character tries to obtain something that will be useful for the final challenge. |

| Definitive test | The character faces the final battle, in which he or she can be successful (victory) or defeated (defeat). |

| Fault reparation | Character’s victory provokes his or her liberation or the liberation of the character that suffered absence. |

| Returning | The contrary to restraint. The character returns to the place of origin or moves to a new one (settlement). |

| Celebration | The successful character that recognizes him or herself as such. |

Source: self-elaboration based on the texts by Cassetti and Di Chio [74].

Group of variables 3: Existings

Table A2.

Categories for the variable “character as a role”.

Table A2.

Categories for the variable “character as a role”.

| Character as a Role | |

|---|---|

| Active | Source of the action. |

| Passive | Object of the initiatives of the other. |

| Influencer | Provokes the actions. “Makes making”. |

| Autonomous | Directly acts, without causes and without mediations. What “makes”. |

| Modifier | Operates as the motion of the action. |

| Conservative | Tries to keep the threatened order. |

| Main character | Main character in the events linked to the studied SDGs. |

| Secondary | Secondary character in the events linked to the studied SDGs. |

| Antagonist | Antagonist character in the events linked to the studied SDGs |

Source: self-elaboration based on the texts by Cassetti and Di Chio [74] and AdMIRA’s template.

Table A3.

Categories for the variable “public/private scenario”.

Table A3.

Categories for the variable “public/private scenario”.

| Environments 1: Sphere | |

|---|---|

| Public | Free-movement spaces, whether they are open or closed. |

| Private | Reserved sphere, where a person develops actions considered to be more intimate. |

Source: self-elaboration based on bibliographic review.

Table A4.

Categories for the variable “space description”.

Table A4.

Categories for the variable “space description”.

| Environments 2: Type of Environment | |

|---|---|

| Domestic spaces | |

| Educational centers | |

| Workplaces | |

| Leisure places | |

| Public space | |

| Other spaces | |

Source: Fedele [18,84].

Group of variables 4: Functions.

Table A5.

Action’s origin.

Table A5.

Action’s origin.

| Action’s Origin | |

|---|---|

| Social | The origin of the action is mainly his or her environment (friends, mates, classmates). |

| Personal | The origin of the action is personal (linked to personal construction). |

| Familiar | The origin of the action is familiar. |

| Romantic | The origin of the action is romantic. |

| Economic | The origin of the action is due to economic issues. |

Source: García-Muñoz y Fedele [30].

Table A6.

Transformations.

Table A6.

Transformations.

| Transformations | |

|---|---|

| Improvement | The environment improves in relation to the character who acts. |

| Worsening | The environment worsens in relation to the character who acts. |

| Neutral | The environment neither improves nor worsens in relation to the character who acts. |

Source: self-elaboration based on the texts by Cassetti and Di Chio [74].

Appendix D. Boca Norte Season 1 Episode Summary from RTVE

| Episode | Synopsis |

| Episode 1 | Andrea, a teenager from a rich family, arrives in El Carmel, a neighborhood in Barcelona. She leaves behind a troubled personal story. Her passion for music will take her to Boca Norte, a cultural center in which she will not be unnoticed. There she will meet Katy, Dani, Andy, Sarah, María and Lu, a group of teenagers from the neighborhood united by their passion for dancing. The guys decide to invite Andrea to Katy’s birthday party and it will end up being a disaster. |

| Episode 2 | After Katy’s party, the guys from Boca Norte practice a song composed by Andrea. Katy is punished, so Andrea will take her place. It will trigger Katy’s envy. Sarah and Andy want to establish a feminist association and conduct surveys on sexuality. This way, they discover that María is a virgin and Lu shows off about her sexual curriculum despite being mocked for his erectile dysfunction. On her side, Andrea thanks Dani for his support to sing and he confesses Boca Norte’s economic difficulties. |

| Episode 3 | Everyone has secrets in Boca Norte and each one takes them their way. In this episode, Lu will have to face them and will experience one of his worst moments. María, swept up by her feelings toward him, will be a great support. Sarah starts to question her sexual orientation and Andrea will be swept up by Andy’s enthusiasm to record their first videoclip. |

| Episode 4 | Boca Norte faces a difficult economic situation. It will be a club for a night to generate money and save it from closing. The party will be the ideal place for all those who are swept up by passion. Andrea, conditioned by drugs, will betray her new friends. |

| Episode 5 | Hangover is still hitting. Boca Norte’s closure is imminent. Sarah does not hesitate to take Andrea to the limit because of the voice note she heard, which makes her tell the truth to Dani and try to put her life together. María questions what happened with Lu at the party and finds Katy to be her biggest support. After all, the music group is affected, despite Andy leaning on the videoclip’s success to try to convince the rest to go on with the project. |

| Episode 6 | Boca Norte’s closure has arrived. Andy, Katy, Sarah and María fight for the center with a protest, but Dani has already given up. Andrea will receive a visit from the past that will change everything. |

| Source: RTVE [91]. | |

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sanahuja, J.A. De los Objetivos del Milenio al Desarrollo Sostenible: Naciones Unidas y Las Metas Globales Post-2015; Anuario CEIPAZ: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murga-Menoyo, M.Á. El Camino Hacia Los ODS: Conformar Una Ciudadanía Planetaria Mediante La Educación. Comillas J. Int. Relat. 2020, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbedahin, A.V. Sustainable Development, Education for Sustainable Development, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Emergence, Efficacy, Eminence, and Future. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbules, N.C.; Fan, G.; Repp, P. Five Trends of Education and Technology in a Sustainable Future. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España. Informe Para el Examen Nacional Voluntario; Gobierno de España: Madrid, España, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo (AECID) Educación y Sensibilización Para El Desarrollo. Available online: https://www.aecid.es/ES/la-aecid/educaci%C3%B3n-y-sensibilizaci%C3%B3n-para-el-desarrollo (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Tian, Q.; Hoffner, C.A. Parasocial Interaction With Liked, Neutral, and Disliked Characters on a Popular TV Series. Mass Commun. Soc. 2010, 13, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.E. Unpleasant Consequences: First Sex in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Veronica Mars, and Gilmore Girls. Jeun. Young People Texts Cult. 2013, 5, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Abal, Y.; Climent Rodríguez, J.A. El Efecto Socializador Del Medio Televisivo En Jóvenes. Influencia de Las Conductas de Gestión Del Conflicto Mostradas Por Personajes de Series de Ficción. Área Abierta 2013, 14, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- González-Fernández, S. El Fenómeno de La Violencia En Televisión: Características y Formas de Representación En La Pequeña Pantalla. Sphera Publica 2017, 2, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, S. Empowered Vulnerability?: A Feminist Response to the Ubiquity of Sexual Violence in the Pilots of Female-Fronted TV Drama Series. In Feminist Erasures: Challenging Backlash Culture; Silva, K., Mendes, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2015; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Raya Bravo, I.; Sánchez-Labella, I.; Durán, V. La Construcción de Los Perfiles Adolescentes En Las Series de Netflix Por Trece Razones y Atípico. Comun. Medios 2018, 37, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, E.; Clares-Gavilán, J.; Sánchez-Navarro, J. New Audience Dimensions in Streaming Platforms: The Second Life of Money Heist on Netflix as a Case Study. Prof. Inf. 2021, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, E. Streaming Wars; Libros Cúpula: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, E.; Källquist, R.; Sveningsson, M. Combining New and Old Viewing Practices: Uses and Experiences of the Transmedia Series “Skam”. Nord. Rev. 2018, 39, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, M. La Segunda Generación de Teen Series: Programas Estadounidenses, Británicos y Españoles de Los 2000–2010. Index Comun. 2021, 11, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Education for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://es.unesco.org/themes/educacion-desarrollo-sostenible (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Scolari, C.A.; Ardèvol, E.; Pérez-Latorre, Ò.; Masanet, M.-J.; Lugo Rodríguez, N. What Are Teens Doing with Media? An Ethnographic Approach for Identifying Transmedia Skills and Informal Learning Strategies. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2020, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporación de Radio y Televisión Española. Cuentas Anuales e Informe de Gestión Correspondientes al Ejercicio Anual Terminado El 31 de Diciembre de 2019; Corporación RTVE: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Segarra-Saavedra, J. Panorámica de La Representación Femenina En La Ficción Online. Los Casos de Las Webseries de PlayZ y RTVE. In Mujer y Televisión: Géneros y Discursos Femeninos en la Pequeña Pantalla; Hidalgo-Martí, T., Ed.; UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- BOE. Ley 13/2022, de 7 de Julio, General de Comunicación Audiovisual; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Prensa RTVE. RTVE Renueva Su Estructura Básica y La Alta Dirección; RTVE: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Singhal, A. East Los High: Transmedia Edutainment to Promote the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Young Latina/o Americans. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]