Using a System Dynamics Simulation Model to Identify Leverage Points for Reducing Youth Homelessness in Connecticut

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Magnitude of Youth Homelessness as a Problem

1.2. Case Study: Connecticut’s Mission to Address Youth Homelessness

1.3. Role of System Dynamics in Addressing Youth Homelessness in Connecticut

2. Methodology

2.1. Forming a Core Modeling Team and Engaging Stakeholders (Phase 1)

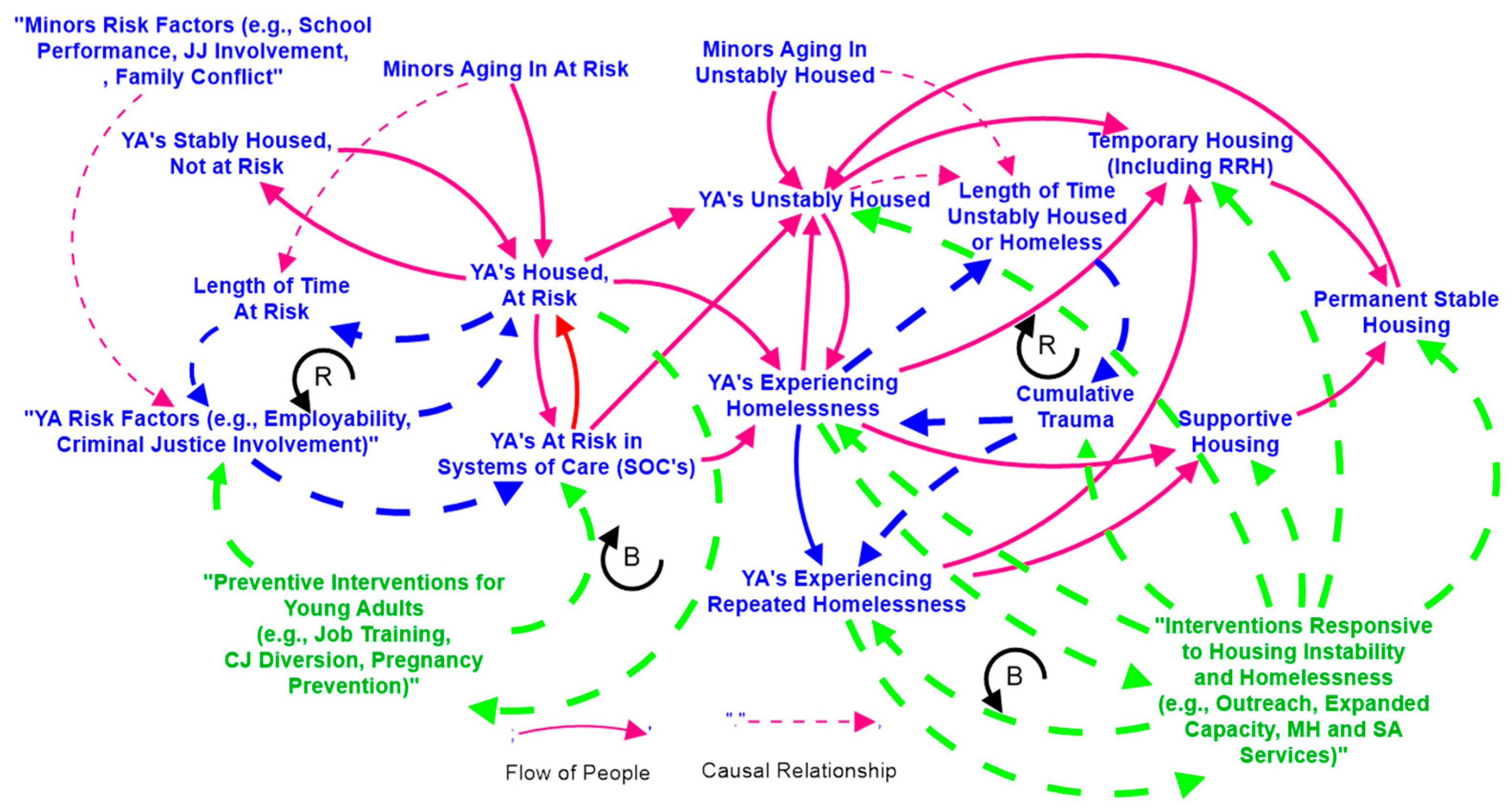

2.2. Causal Mapping (Phase 2)

2.3. Developing the Simulation Model (Phase 3)

- Initial populations in various statuses, corresponding with stocks in the model. These come from various data sources or estimation procedures carried out by respected authorities. Some of these are further adjusted based on estimates derived from the youth homelessness literature, for example, dividing the initial population of homeless young adults into groups of those experiencing homelessness for the first time and those that endure repeated homelessness. These are presented in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

- Assumptions based on the youth homelessness literature and discussions of our CMDT that assign numerical values to concepts in the literature. Some of these numerical assumptions are not based on particular values derived from the literature as much as a sense of the relative strength of the causal relationships they represent, based on those discussions with the CMDT. These are presented in Table S2A–E in the Supplementary Materials.

- An additional set of model parameters came from calibrating the model to produce what we believed was a reasonable baseline simulation, one that projects current trends and assumes no major new initiatives to prevent or remediate youth homelessness. We considered a number of trends in unstable housing and homelessness in youth, both locally and nationally. Some were growing, others declining. There was no definitive trend apparent. The CMDT confirmed that a stable trend going into the future was the most likely scenario. Therefore, we decided to settle on a baseline simulation that projected constant levels of unstable housing and homelessness for youth. The calibration process then consisted of calculating the fractions of minors and young adults flowing from one status to the next (e.g., from At Risk to Unstably Housed) over a given period that would maintain (relatively) stable numbers in each status as the simulation progressed over a ten-year period. These are presented in Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials for each section of the model. Table S3 also contains data derived from the CT CAN (Coordinated Access Network) Data Dashboards (ctcandata.org) on Temporary and Supportive Housing programs, the average lengths of time youth spend in those programs, and the fractions of various outcomes upon leaving those programs.

- Data on the costs of homelessness and of various interventions to reduce homelessness, taken from various studies and used to calculate social costs and program costs, both on a monthly and cumulative basis. These are presented in Table S4 in the Supplementary Materials. Calculating these costs and resultant savings due to various interventions enables the model to project resources that can be freed up and reinvested in those interventions.

2.4. Building Stakeholders’ Capacity to Use the Model (Phase 4)

3. Results

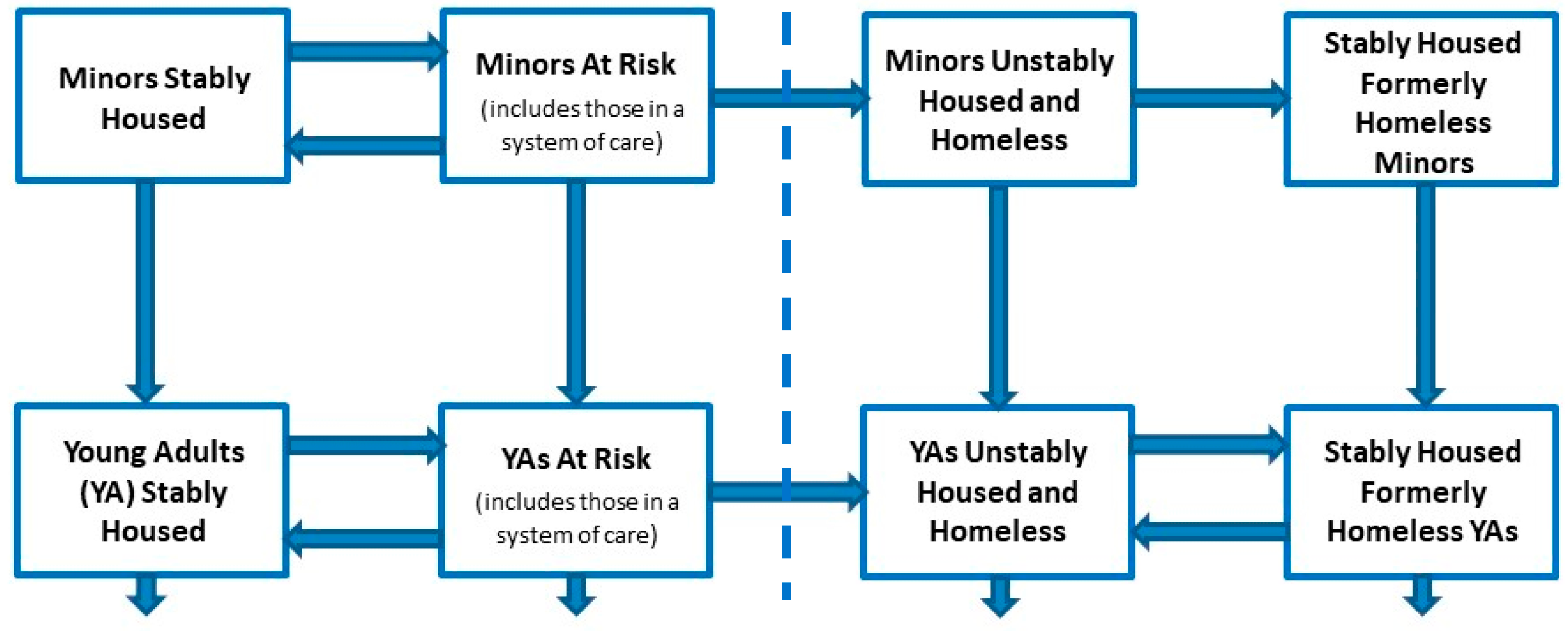

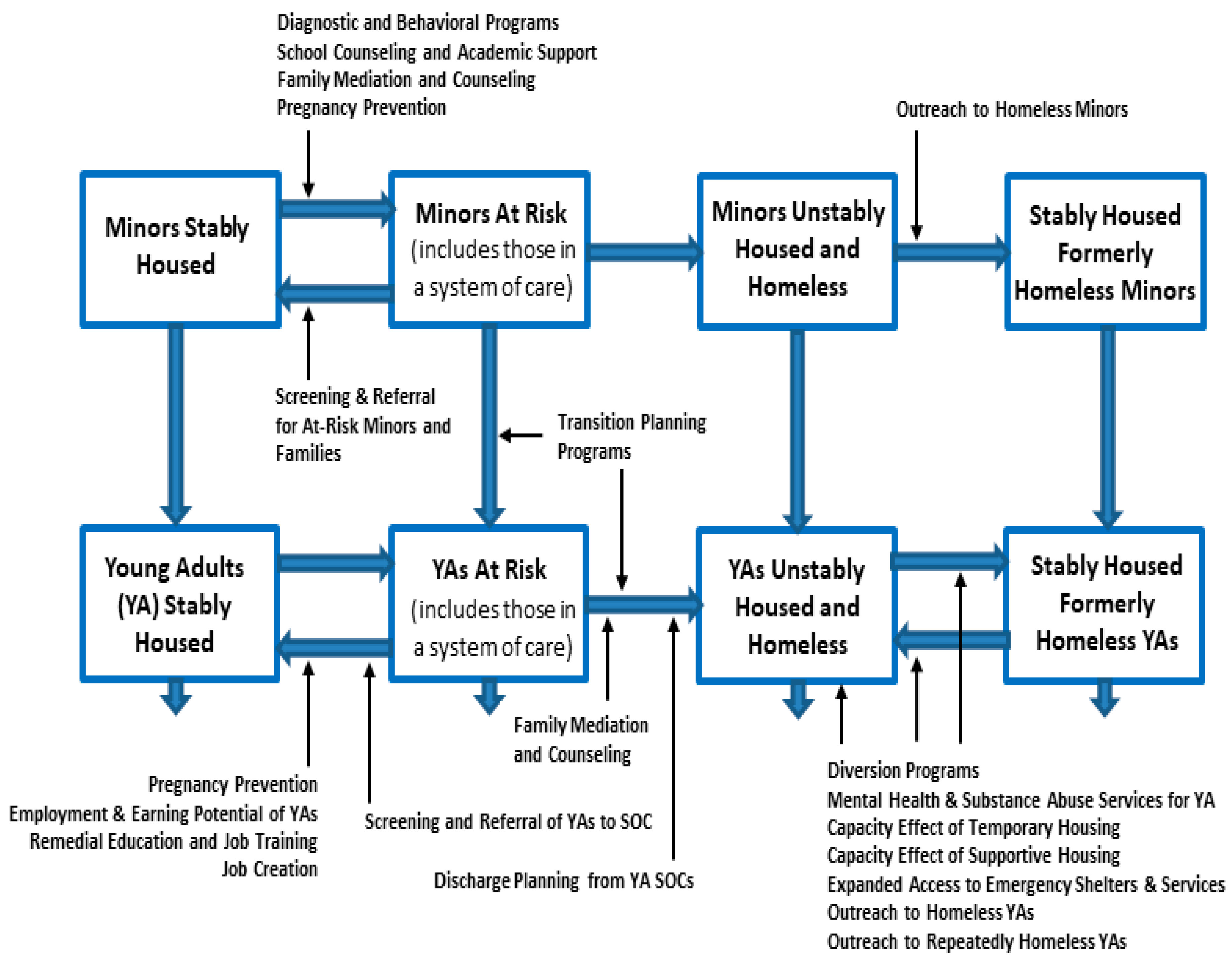

3.1. Model Structure

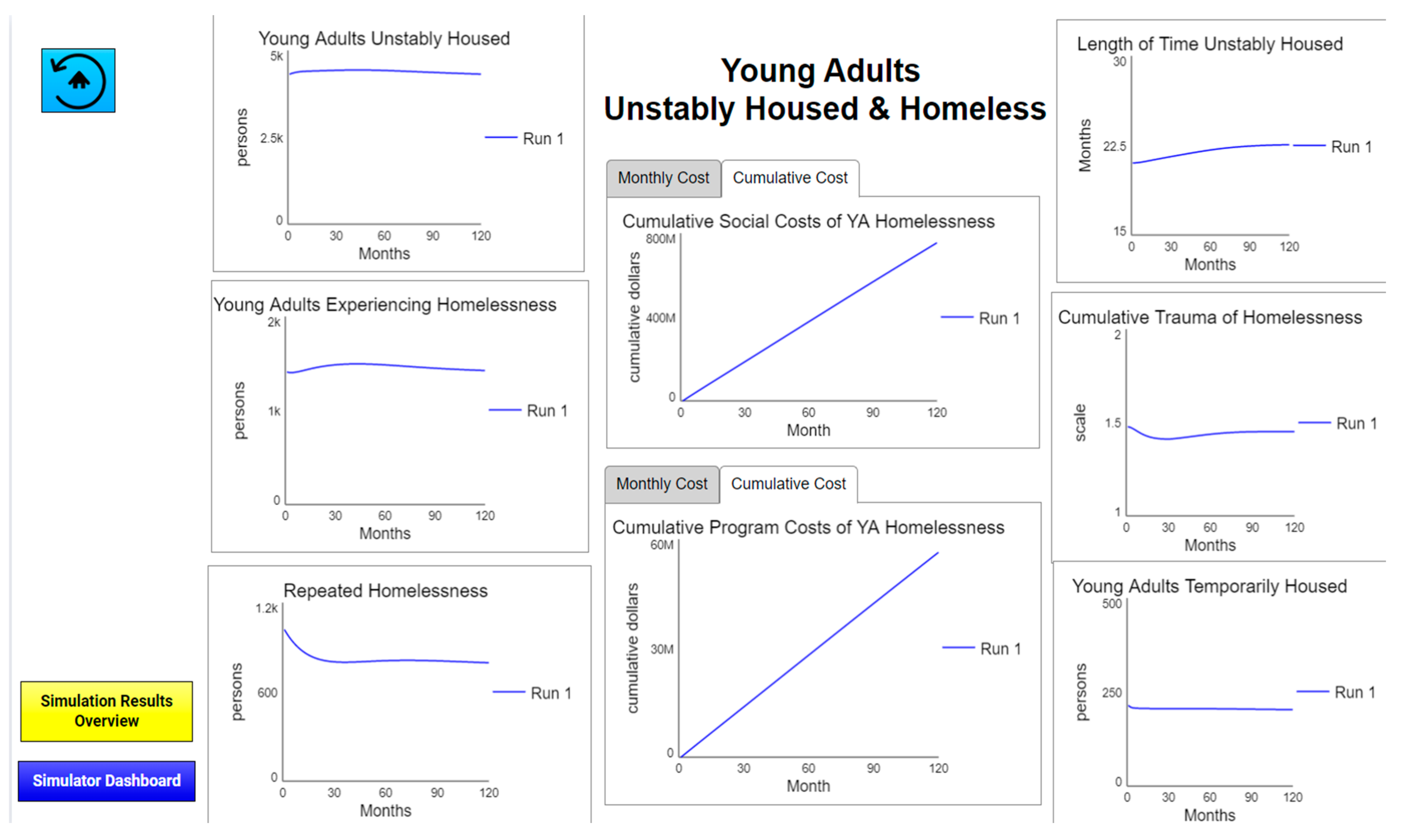

3.2. Model Interface

3.3. Using the Simulator

4. Discussion

- As with the CMDT’s experience in developing the model, stakeholders spoke of the process of using the model as valuable, extremely important, and different from anything that they have experienced before. They attributed this to the process of bringing people together who have different experiences and perspectives and who come from diverse sectors of the system. For example, attendees of the Learning Lab included policy-makers, front-line staff, and people with lived experience from different parts of the system, including schools/education, criminal/juvenile justice, mental health, employment, child welfare, homelessness crisis response, and housing. Some of these system stakeholders had worked together, but many had not. Additionally, young people with lived experience of homelessness and housing instability both contributed to the development of the model and also co-led some of the Learning Labs. Their engagement and unique perspectives were greatly valued by other stakeholders, resulting in a rich dialogue and new understanding of why programs may or may not be working.

- A big “ah-ha” moment for stakeholders was a shift in thinking about the time it takes to see their desired changes in outcomes after implementing an intervention. They realized that they may not see the positive effect of interventions until several years down the line. This realization brought about some reflection regarding how they may be shifting strategies too early because they had believed the strategies to be ineffective when reviewing short-term performance metrics that indicated no change. In fact, those strategies may actually be working, and anticipating a longer-term view of change was important. One of the stakeholders commented: “I’m telling other people about the model. It is really groundbreaking if we can think this way. It made me think differently about time—how it might take more time for an intervention to have its effect.” This insight also resulted in a dialogue about how to communicate with policymakers and funders that some programs will take time before seeing the desired effect so that funding is maintained over the necessary period.

- Stakeholders were able to test a widely-held theory that youth homelessness could be significantly reduced by targeting funding and resources to increase the capacity of the current crisis response system (e.g., outreach, diversion, and housing programs). They were surprised to see that this strategy was both expensive and had only a limited impact. When they added prevention efforts to this strategy, they observed a significant cost reduction and much higher impact on reducing youth homelessness. The insight that ‘housing helped less than prevention’ was not what they had expected. They learned that a balance of preventive programs with crisis response interventions was most effective in reducing youth homelessness. They also learned that some interventions may be redundant, and adding interventions may achieve diminishing returns. This led to the insight that it is important to be very selective in crafting combined strategies when resources are limited and coordinating programs from different agencies is a challenge. The model provides a framework for experimenting with different combinations of interventions to find the most efficient one for reaching a particular goal.

- They learned there are unintended consequences to some strategies that can result in greater, rather than fewer, young people experiencing homelessness. For example, when screening and referrals of minors and young adults to Systems of Care (SOCs) were increased, more youth/young adults experienced homelessness than in the baseline simulation. They discovered that this was the result of having more young people leaving those Systems of Care without adequate discharge planning and falling into unstable housing and homelessness. Increased referrals to SOCs had to be combined with expanded discharge planning in order to avoid that negative effect.

- Finally, the stakeholders using the model learned that youth homelessness could not be driven to zero regardless of how many resources are applied. Experience across a large number of simulations suggested that the maximum reduction in homelessness was around 67%. When the number of youths experiencing homelessness is significantly reduced, the ones remaining will be those with more significant problems that will make them more difficult to house.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Career Resources/Capital Workforce Partners

- Center for Children’s Advocacy

- CT Court Support Services Division

- CT Department of Children & Families

- CT Department of Housing

- CT DMHAS—Young Adult Services

- Journey Home

- Partnership for Strong Communities

- The Connection, Inc.

- Tow Youth Justice Institute

- University of New Haven

- Youth Action Hub/Institute for Community Research

Appendix B

| Prevention | Legislation, Policy and Investment Strategies That Build Assets and Address System Gaps That Increase the Risk of Homelessness. | |

| School Counseling and Academic Support for Minors | Improves graduation rates and academic performance, reduces fraction of minors at risk by 20%, and increases later employability of young adults, also by 20%. | |

| Diagnostic and Behavioral Services for Minors | Reduces the fraction of minors at risk by 20% by identifying and providing services for various conditions. | |

| Family Mediation and Counseling for Minors | Reduces fraction of minors at risk by 20% and increases ability of young adults to remain with family. | |

| Screening and Referral of Minors to Systems of Care | Increases the fraction of minors at risk entering Systems of Care by 20%. | |

| Young Adult Screening and Referral to Systems of Care | Increases fraction of at-risk young adults entering Systems of Care and receiving services by 50%. | |

| Juvenile Justice Diversion for Minors | Reduces likelihood of juvenile justice involvement of minors and later criminal justice involvement as young adults by 50%. | |

| Criminal Justice Diversion of Young Adults | Halves likelihood of young adults’ involvement with criminal justice system and affects employability and ability to remain with family and, in turn, reduces the fraction at risk by 17%. | |

| Pregnancy Prevention | Reduces fraction of both minors and young adults at risk due to pregnancy and parenting by 20%. | |

| Remedial Education and Job Training | Doubles employability of young adults and reduces fraction at risk by 17% (Impact will depend on job creation intervention). | |

| Job Creation | Will increase availability of jobs and is necessary for job training to have its full impact on fraction of young adults at risk. | |

| Transition/Permanency Planning from Systems of Care for Minors | Doubles the fraction of minors aging out of Systems of Care going into appropriate programs as young adults. | |

| Young Adult Discharge Planning in Systems of Care | Reduces fraction of young adults leaving Systems of Care becoming unstably housed or homeless by half. | |

| Crisis Response | Policies and Practice to Identify Young People Experiencing Housing Instability or Homelessness and to Intervene Early by Connecting Them to Housing and Supportive Services. |

| Systems of Care Outreach to Unstably Housed Minors | Increases flow of unstably housed minors into Systems of Care that can provide services by 50%. |

| Outreach to Homeless Minors | Connects 50% more minors experiencing homelessness to housing. |

| Outreach to Homeless Young Adults | Connects 50% more young adults experiencing homelessness to housing, preventing persistent homelessness. |

| Outreach to Repeatedly Homeless Young Adults | Outreach with special emphasis on young adults who have experienced repeated homelessness to connect them to housing. |

| Diversion Programs | Increases the number of young adults who can receive diversion funds that keep unstably housed young adults from experiencing homelessness, reduces fraction of unstably housed who might experience homelessness by 20%. Examples: financial, utility, and/or rental assistance, short-term case management, conflict mediation, connection to jobs and mainstream services, and housing search. |

| Expand Access to Emergency Housing and Services | Increases the number of emergency beds/apartments to serve a larger number of young adults experiencing first time and repeated homelessness. |

| Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services for Homeless Young Adults | Services that reduce cumulative trauma of being homeless by half and thereby reduce the fraction of young adults who experience repeated homelessness. Examples: Mental health services and substance use programs delivered by agencies or community providers. |

| Housing Stability | Initiatives and Support for People Who Have Experienced Homelessness That Allows Them to Exit Homelessness Quickly and Never Experience It Again. |

| Expand Temporary Housing Capacity | Increase the capacity of temporary housing programs to serve a larger number of young adults experiencing first time and persistent homelessness. Examples: Transitional housing, host homes, DMHAS Young Adult Services’ supervised apartments, and rapid re-housing programs that are time-limited and aim to stably rehouse young people by providing them with housing/rental assistance and supports for health and well-being, education, and employment. |

| Expand Long-Term Supportive Housing | Make additional housing units available for young adults experiencing persistent homelessness who require extensive additional services to keep them stably housed. Examples: Permanent supportive housing that combines affordable housing assistance with voluntary support services. |

| Preventing Returns to Homelessness | Reduce the flow of young adults by half who had achieved stable housing and fell back to unstable housing with short-term rental assistance and other supports. Examples: Temporary housing programs that offer short-term assistance to young adults who experience a housing crisis (loss of job/roommate, increased rent, etc.) within a year of exiting their programs. |

References

- Morton, M.H.; Dworsky, A.; Matjasko, J.L.; Curry, S.R.; Schlueter, D.; Chávez, R.; Farrell, A.F. Prevalence and Correlates of Youth Homelessness in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USICH. Key Federal Terms and Definitions of Homelessness among Youth; United States Interagency Council on Homelessness: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/Federal-Definitions-of-Youth-Homelessness.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Fraser, B.; Pierse, N.; Chisholm, E.; Cook, H. LGBTIQ+ Homelessness: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecker, J.; Aubry, T.; Sylvestre, J. Pathways Into Homelessness Among LGBTQ2S Adults. J. Homosex. 2019, 67, 1625–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, L.; Pilnik, L. Preventing Homelessness for System-Involved Youth. Juv. Fam. Court J. 2018, 69, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edidin, J.P.; Ganim, Z.; Hunter, S.J.; Karnik, N.S. The mental and physical health of homeless youth: A literature review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerswald, C.L.; Lin, J.S.; Parriott, A. Six-year mortality in a street-recruited cohort of homeless youth in San Francisco, California. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, D.M.; Gaetz, S.; Crowe, C.; Ford-Jones, E. Homeless youth’s overwhelming health burden: A review of the literature. Paediatr. Child Health 2011, 16, e43–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, É.; Haley, N.; Leclerc, P.; Sochanski, B.; Boudreau, J.-F.; Boivin, J.-F. Mortality in a cohort of street youth in Montreal. Jama 2004, 292, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Rusow, J.A.; Holguin, M.; Semborski, S.; Onasch-Vera, L.; Wilson, N.; Rice, E. Exchange and Survival Sex, Dating Apps, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation Among Homeless Youth in Los Angeles. J. Prim. Prev. 2019, 40, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Maria, D.; Hernandez, D.C.; Arlinghaus, K.R.; Gallardo, K.R.; Maness, S.B.; Kendzor, D.E.; Reitzel, L.R.; Businelle, M.S. Current Age, Age at First Sex, Age at First Homelessness, and HIV Risk Perceptions Predict Sexual Risk Behaviors among Sexually Active Homeless Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, N.E.; Bell, S. Correlates of Engaging in Survival Sex among Homeless Youth and Young Adults. J. Sex Res. 2011, 48, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, D.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J.; Batterham, P.; Mallett, S.; Rice, E.; Milburn, N.G. Housing stability over two years and HIV risk among newly homeless youth. AIDS Behav. 2007, 11, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, S.; Willard, J.; Herbers, J.E.; Cutuli, J.; Eyrich Garg, K.M. Youth homelessness: Prevalence and mental health correlates. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 2014, 5, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, R.; Kim, Y. Aging out of foster care: Homelessness, post-secondary education, and employment. J. Public Child Welf. 2018, 12, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfra, L. Impact of Homelessness on School Readiness Skills and Early Academic Achievement: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, G.M.; Cerven, C.; Curry, S.; Robinson, S.R.; Patel, S. Missed Opportunities in Youth Pathways through Homelessness; Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019; Available online: https://voicesofyouthcount.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ChapinHall_VoYC_Youth-Pathways-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Fowler, P.J.; Toro, P.A.; Miles, B.W. Pathways to and from homelessness and associated psychosocial outcomes among adolescents leaving the foster care system. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Census. Population Projections for CT; Connecticut Data Collaborative: Hartford, CT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- CCEH. Connecticut Counts: Annual Point-In-Time Count and Youth Outreach and Count; Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness: Hartford, CT, USA, 2019; Available online: https://cceh.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/PIT_2019.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- CTDOH. Opening Doors for Youth 2.0: An Action Plan to Provide All Connecticut Youth and Young Adults with Safe, Stable Homes and Opportunities; Connecticut Department of Housing: Hartford, CT, USA, 2017; Available online: https://cca-ct.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/OpeningDoorsforYouth_FullPlan_03-25-2015.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- USICH. Criteria and Benchmarks for Achieving the Goal of Ending Youth Homelessness; United States Interagency Council on Homelessness: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/Youth-Criteria-and-Benchmarks-revised-Feb-2018.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Andersen, D.F.; Vennix, J.A.; Richardson, G.P.; Rouwette, E.A. Group model building: Problem structuring, policy simulation and decision support. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2007, 58, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovmand, P.S. Group Model Building and Community-Based System Dynamics Process; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gullett, H.L.; Brown, G.L.; Collins, D.; Halko, M.; Gotler, R.S.; Stange, K.C.; Hovmand, P.S. Using community-based system dynamics to address structural racism in community health improvement. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, S130–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.T.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Parker, E.A. A Typology of Youth Participation and Empowerment for Child and Adolescent Health Promotion. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 46, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppen, E. Stakeholder analysis. In Foresight in Organizations; van der Duin, P., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hovmand, P.S.; Andersen, D.F.; Rouwette, E.; Richardson, G.P.; Rux, K.; Calhoun, A. Group model building scripts as a collaborative planning tool. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2012, 29, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Martinez-Moyano, I.J.; Pardo, T.A.; Cresswell, A.M.; Andersen, D.F.; Richardson, G.P. Anatomy of a group model-building intervention: Building dynamic theory from case study research. Syst. Dyn. Rev. J. Syst. Dyn. Soc. 2006, 22, 291–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovmand, P.; Rouwette, E.; Andersen, D.; Richardson, G. Scriptapedia; Wikibooks: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Scriptapedia (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- ISEE Systems. Stella Architect. 2017. [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.iseesystems.com/Store/Products/Stella-Architect.Aspx (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Stemler, S.E. Content analysis. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource; Scott, R.A., Kosslyn, S.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, D.F.; Richardson, G.P. Scripts for group model building. Syst. Dyn. Rev. J. Syst. Dyn. Soc. 1997, 13, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, H.; Park, J. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), service use, and service helpfulness among people experiencing homelessness. Fam. Soc. 2012, 93, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, D.B.; Susser, E.S.; Struening, E.L.; Link, B.L. Adverse childhood experiences: Are they risk factors for adult homelessness? Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, S.C.; Nurius, P.S.; Green, S. Homelessness history impacts on health outcomes and economic and risk behavior intermediaries: New insights from population data. Fam. Soc. 2016, 97, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremner, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Strompolis, M.; Bennett, K.J.; Morse, M.; Radcliff, E. Assessing the interrelatedness of multiple types of adverse childhood experiences and odds for poor health in South Carolina adults. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 65, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Dube, S.R.; Williamson, D.F.; Thompson, T.J.; Loo, C.M.; Giles, W.H. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abus. Negl. 2004, 28, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupre, M.E. Educational differences in health risks and illness over the life course: A test of cumulative disadvantage theory. Soc. Sci. Res. 2008, 37, 1253–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Mason, S.; Rexrode, K.; Spiegelman, D.; Hibert, E.; Kawachi, I.; Jun, H.J.; Wright, R.J. Physical and sexual abuse in childhood as predictors of early-onset cardiovascular events in women. Circulation 2012, 126, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Janal, M.N.; Roy, M. Childhood trauma and prevalence of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waite, R.; Davey, M.; Lynch, L. Self-rated health and association with ACEs. J. Behav. Health 2013, 2, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, L.E.; Mota, N.; Afifi, T.O.; Katz, L.Y.; Distasio, J.; Sareen, J. Relationship between adverse childhood experiences and homelessness and the impact of axis I and II disorders. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, S275–S281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, V.; Murphey, D. The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences, Nationally, by State, and by Race or Ethnicity; Child Trends: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.childtrends.org/publications/prevalence-adverse-childhood-experiences-nationally-state-race-ethnicity (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Sacks, V.; Murphey, D.; Moore, K. Adverse Childhood Experiences: National and State-level Prevalence; Child Trends: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Brief-adverse-childhood-experiences_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Tucciarone, J.T., Jr. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Homeless Chronicity, and Age at Onset of Homelessness. Electron. Diss. 2019, 3534. Available online: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3534 (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Turner, H.A.; Merrick, M.T.; Finkelhor, D.; Hamby, S.; Shattuck, A.; Henly, M. The Prevalence of Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships Among Children and Adolescents; US Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/249197.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Radcliff, E.; Crouch, E.; Strompolis, M.; Srivastav, A. Homelessness in childhood and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brakenhoff, B.; Jang, B.; Slesnick, N.; Snyder, A. Longitudinal predictors of homelessness: Findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth-97. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 18, 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerde, J.A.; Bailey, J.A.; Kelly, A.B.; McMorris, B.J.; Patton, G.C.; Toumbourou, J.W. Life-course predictors of homelessness from adolescence into adulthood: A population-based cohort study. J. Adolesc. 2021, 91, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martijn, C.; Sharpe, L. Pathways to youth homelessness. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.J.; Pillai, V.K. Determinants of runaway episodes among adolescents using crisis shelter services. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2006, 15, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bree, M.B.; Shelton, K.; Bonner, A.; Moss, S.; Thomas, H.; Taylor, P.J. A longitudinal population-based study of factors in adolescence predicting homelessness in young adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.E.; Dworsky, A.; Brown, A.; Cary, C.; Love, K.; Vorhies, V. Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at Age 26; Chapin Hall Center for Children: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hail-Jares, K.; Vichta-Ohlsen, R.; Butler, T.; Dunne, A. Psychological distress among young people who are couchsurfing: An exploratory analysis of correlated factors. J. Soc. Distress Homelessness 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hail-Jares, K.; Vichta-Ohlsen, R.; Nash, C. Safer inside? Comparing the experiences and risks faced by young people who couch-surf and sleep rough. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, P.J. Couch surfing on the margins: The reliance on temporary living arrangements as a form of homelessness amongst school-aged home leavers. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 16, 521–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Landvogt, K. Couch-surfing limbo: ‘Your life stops when they say you have to find somewhere else to go’. Parity 2016, 29, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Petry, L.; Hill, C.; Milburn, N.; Rice, E. Who Is Couch-Surfing and Who Is on the Streets? Disparities Among Racial and Sexual Minority Youth in Experiences of Homelessness. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gultekin, L.E.; Brush, B.L.; Ginier, E.; Cordom, A.; Dowdell, E.B. Health risks and outcomes of homelessness in school-age children and youth: A scoping review of the literature. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020, 36, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellow, J.; Kloos, B.; Townley, G. Previous Homelessness as a Risk Factor for Recovery from Serious Mental Illnesses. Community Ment. Health J. 2015, 51, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toros, H.; Flaming, D.; Burns, P. Early Intervention to Prevent Persistent Homelessness: Predictive Models for Identifying Unemployed Workers and Young Adults Who Become Persistently Homeless; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerger, S.; Strehlow, A.J.; Gundlapalli, A.V. Homeless Young Adults and Behavioral Health: An Overview. Am. Behav. Sci. 2008, 51, 824–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, M.; Schteingart, J.S.; Williams, N.C.; Carlin-Mathis, J.; Bialo-Karagis, N.; Becker-Klein, R.; Weitzman, B.C. Long-term associations of homelessness with children’s well-being. Am. Behav. Sci. 2008, 51, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamathi, A.; Hudson, A.; Greengold, B.; Slagle, A.; Marfisee, M.; Khalilifard, F.; Leake, B. Correlates of substance use severity among homeless youth. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2010, 23, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, D.; Mallett, S.; Gurrin, L.; Milburn, N.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J. Changes over time among homeless young people in drug dependency, mental illness and their co-morbidity. Psychol. Health Med. 2007, 12, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Hoyt, D.R.; Johnson, K.D.; Chen, X. Victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among runaway and homeless adolescents. Violence Vict. 2007, 22, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, M.; Soong, W.; Nicholls, C.; Griffiths, J.; Curtis, K.; Follett, D.; Smith, W.; Waters, F. Homelessness youth and mental health service utilization: A long-term follow-up study. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.P.; Diguiseppi, G.; De Leon, J.; Prindle, J.; Sedano, A.; Rivera, D.; Henwood, B.; Rice, E. Understanding pathways between PTSD, homelessness, and substance use among adolescents. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2019, 33, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Cline, H.; Jones, K.; Vartanian, K. Direct and indirect pathways between childhood instability and adult homelessness in a low-income population. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brothers, S.; Lin, J.; Schonberg, J.; Drew, C.; Auerswald, C. Food insecurity among formerly homeless youth in supportive housing: A social-ecological analysis of a structural intervention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 245, 112724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Brisson, D.; Burnes, D. Do We Really Know how Many Are Homeless?: An Analysis of the Point-In-Time Homelessness Count. Fam. Soc. 2016, 97, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, R.E. Living doubled-up: Influence of residential environment on educational participation. Educ. Urban Soc. 2012, 44, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergamit, M.; Cunningham, M.K.; Burt, M.R.; Lee, P.; Howell, B.; Bertumen, K.D. Counting homeless youth: Promising practices from the Youth Count! initiative. Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/23871/412876-Counting-Homeless-Youth.PDF (accessed on 7 September 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirsch, G.B.; Mosher, H.I. Using a System Dynamics Simulation Model to Identify Leverage Points for Reducing Youth Homelessness in Connecticut. Systems 2023, 11, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030163

Hirsch GB, Mosher HI. Using a System Dynamics Simulation Model to Identify Leverage Points for Reducing Youth Homelessness in Connecticut. Systems. 2023; 11(3):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030163

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirsch, Gary B., and Heather I. Mosher. 2023. "Using a System Dynamics Simulation Model to Identify Leverage Points for Reducing Youth Homelessness in Connecticut" Systems 11, no. 3: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030163

APA StyleHirsch, G. B., & Mosher, H. I. (2023). Using a System Dynamics Simulation Model to Identify Leverage Points for Reducing Youth Homelessness in Connecticut. Systems, 11(3), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030163