Critical Thinking Skills Enhancement through System Dynamics-Based Games: Insights from the Project Management Board Game Project

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Analyze and account for one’s own biases in judgment and experience;

- Break down a problem into its parts to expose its underlying logic and assumptions;

- Gather and evaluate pertinent evidence from one’s own observations and experimentation or outside sources;

- Modify and reevaluate one’s own thinking in light of what has been learned;

- Form a reasoned assessment to propose a solution to a problem or a more accurate understanding of the topic at hand.

2. A Brief Literature Review and the Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Concept of Critical Thinking

- Analysis involves breaking down complex information into smaller parts, identifying patterns, and evaluating evidence to make a reasoned judgment.

- Evaluation involves assessing the credibility and relevance of information, evaluating arguments, and determining the strengths and weaknesses of different viewpoints.

- Inference involves drawing conclusions based on available evidence and making predictions about future events based on past experiences and patterns.

- Interpretation involves understanding the meaning of information, analyzing its significance, and applying it to new situations.

- Explanation entails communicating complex ideas or concepts clearly and concisely, using appropriate evidence and reasoning to support arguments.

- Self-regulation involves monitoring one’s own thinking and behavior, recognizing biases and assumptions, and adjusting one’s approach based on feedback and new information.

- (a)

- Standardized tests, such as the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) and the Watson–Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal: these tests are used to evaluate skills such as analysis, inference, evaluation, and deductive reasoning—as discussed in Bernard et al. [42]—and have been already employed in several studies, such as in the work by Alkharusi [43] focused on university students.

- (b)

- Portfolios can be used to collect and evaluate students’ work over time. This method provides a more comprehensive view of students’ critical thinking skills development as it captures evidence of their progress and growth over an extended period, as demonstrated by the work of Coleman et al. [44] that focuses on students active in the social work education domain.

- (c)

- Peer and self-assessment: as also discussed by Siles-González and Solano-Ruiz [45], peer and self-assessment can be effective methods for assessing critical thinking skills as they encourage students to reflect on their own thinking and provide feedback to their peers.

- (d)

- Observation and performance tasks: Observing students while they engage in tasks that require critical thinking can provide valuable information on their skills. Performance tasks can be different and include activities such as writing essays or analyzing arguments, which can be assessed using rubrics or scoring methods, as Kankaraš and Suarez-Alvarez emphasize [46].

- (e)

- Interviews can be used to assess critical thinking skills by directly asking students to reflect on their thinking processes and reasoning, as demonstrated in the study by Jaffe et al. [47]. This method provides insights into how students approach problems, make decisions, and evaluate arguments, and allows individually eliciting information about the perceived acquisition of critical skills, as also discussed in Tiwari et al. [48].

- (f)

- Classroom-based assessments can include a variety of methods such as questioning techniques, class discussions, and simulations. These methods provide opportunities for students to demonstrate their critical thinking skills in a classroom setting (e.g., Zepeda [49]).

2.2. The Use of SD-Based Games and ILEs to Enhance Critical Thinking

- Systems are considered as a whole;

- Emphasis is placed on the internal structure of the system as the cause of its dynamic behavior;

- Rather than considering relationships in a model as being linear for the sake of simplicity, emphasis is placed on the non-linear character of many relationships;

- Process delays (e.g., information delays) in social systems are considered important.

2.3. System Dynamics, Critical Thinking, and the Field of Project Management

- Have a specific objective (scope) to be completed within certain specifications (requirements);

- Have defined start and end dates;

- Have funding limits;

- Consume and/or utilize resources.

3. Research Design and a Presentation of the SD-Based PMBoG Game

3.1. Research Design: Overview

- Online: the PMBoG ILE is available online at the following address: https://exchange.iseesystems.com/public/barnaf/pmbog-ile/index.html#page1 accessed on 13 November 2023;

- Single-player: the PMBoG ILE allows for one user at a time to play the game;

- Symmetric: any player accessing the PMBoG ILE will have a set of decision-making levers at their disposal that are equal for all the users;

- Competitive: the PMBoG ILE stimulates users to perform, that is to say, complete all the tasks successfully and with the highest score possible.

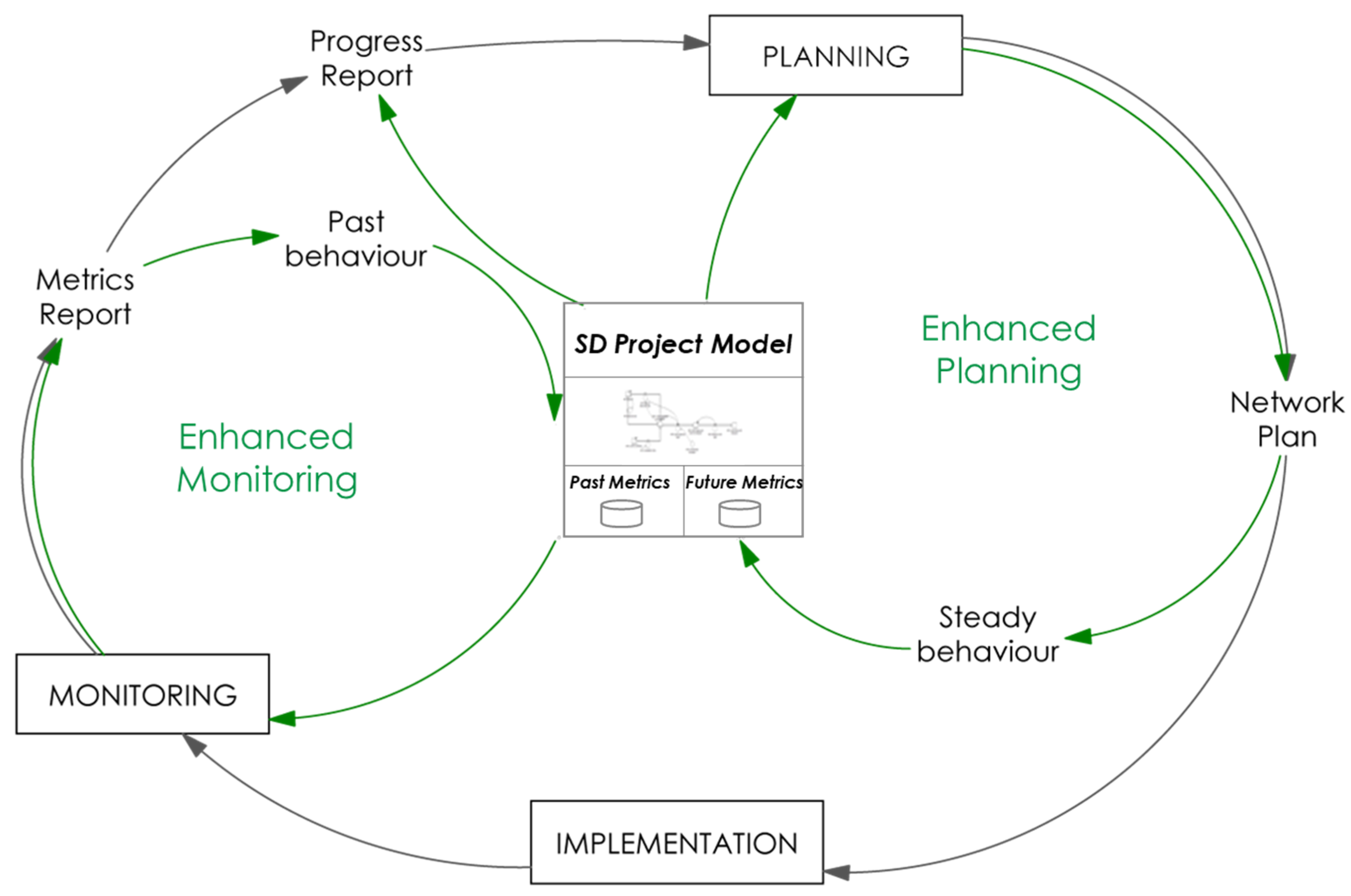

3.2. An Overview of the PMBoG SD-Based Model and ILE

- Articulate the problem that needs to be addressed;

- Formulate a dynamic hypothesis or theory about the causes of the problem;

- Build the simulation model to test the dynamic hypothesis;

- Test the model;

- Design and evaluate policies.

- Time horizon: 7 months, with start time at −1 and stop time at 6.

- DT: 1 month.

- Variable counts: stocks: 117; flows: 157; converters: 628; constants: 249; equations: 536; graphicals: 0.

- Integration method: Euler.

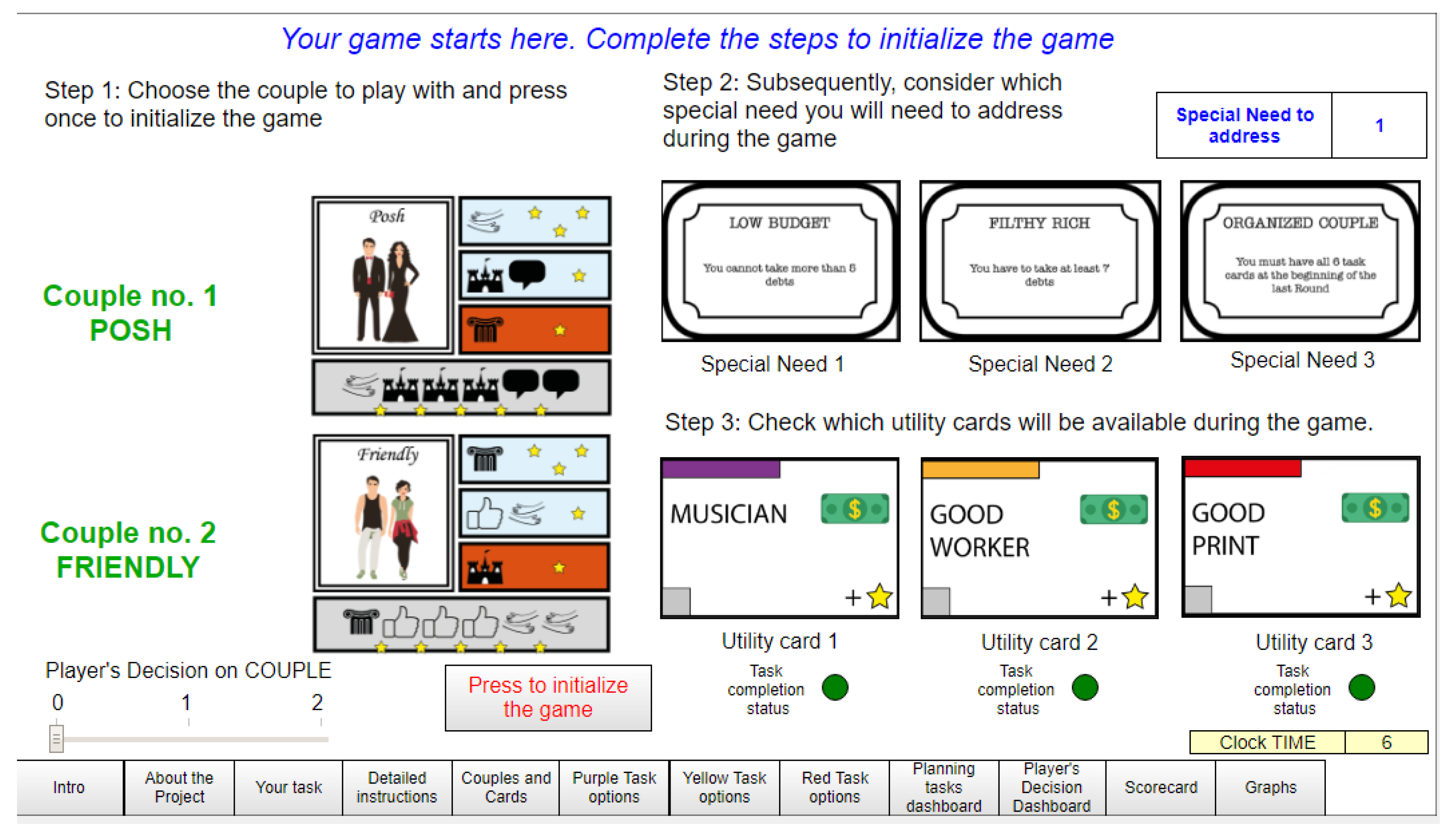

3.3. Description of the PMBoG ILE

- First, provide preliminary information about the PMBoG project and the game;

- Subsequently, describe the task assigned to the player and the main instructions to follow to play and interact properly with the simulation model;

- Lastly, allow the player to play the game and check the results of the simulation.

- Step 1: Choose the couple you are willing to play with and analyze carefully what that couple wishes (“Couples and cards” page). Then, “initialize” the game.

- Step 2: Check what “special need” you will be required to address (“Couples and cards” page).

- Step 3: Check which utility cards (e.g., an additional worker or a good musician) will be available during the game (“Couples and cards” page).

- Step 4: Check which options are available for each category and typology of tasks (“Task options pages”: purple, yellow, and red) and start planning them. Note that only for the first round of action, you will be allowed to plan the tasks in advance of all the other activities … (through the “Planning task dashboard”).

- Step 5: From clock time = 0, use the “Player’s Decision Dashboard” to make your decisions, such as allocating workers to specific tasks, mitigating risks, and hiring (or releasing) staff.

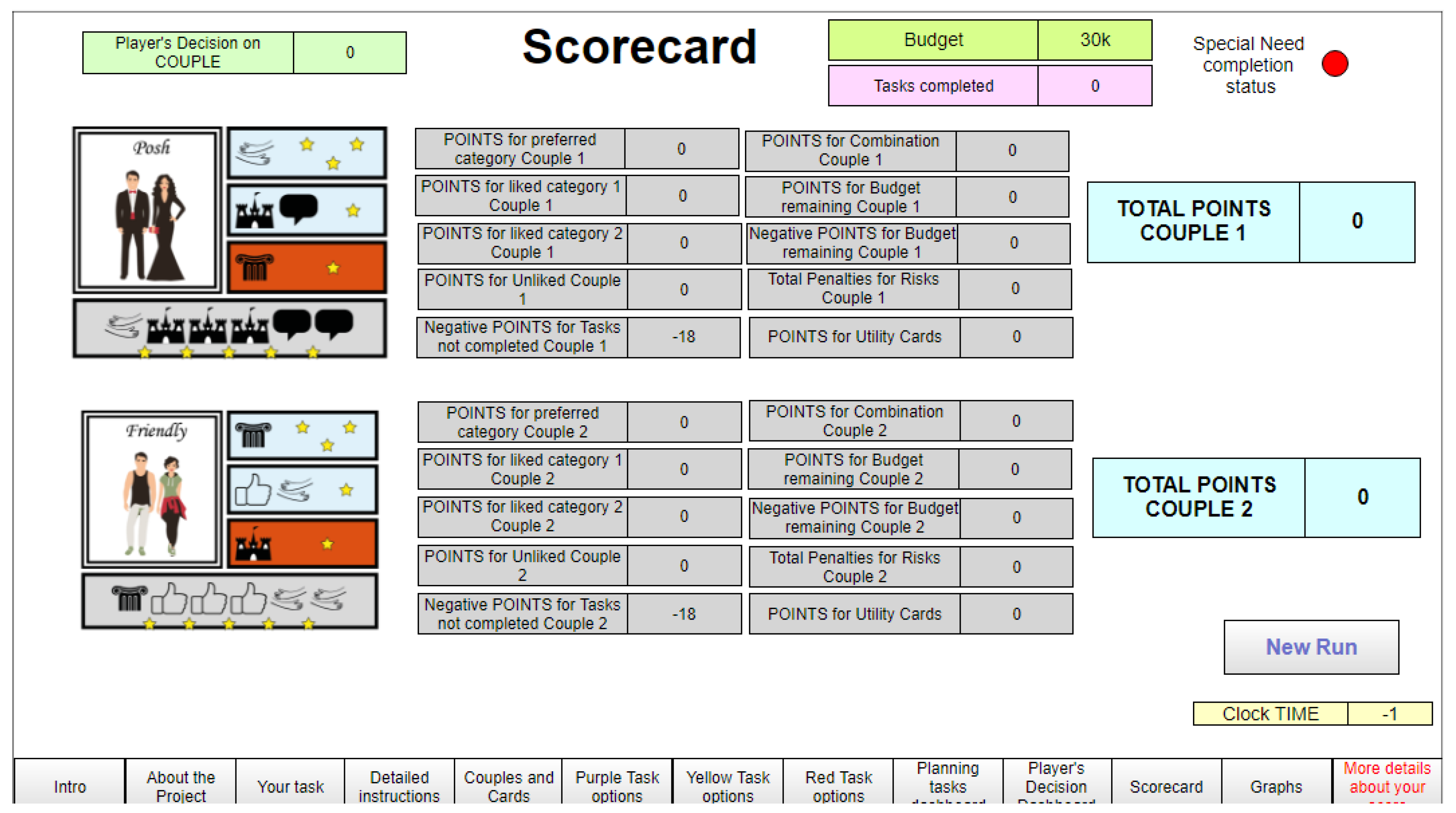

- Step 6: The results of your simulation will be available throughout the windows of the simulator, with the final score calculated in the “Scorecard”.

4. Results

5. Discussion

- The ability of analysis involves breaking down complex information into smaller parts, identifying patterns, and evaluating evidence to make a reasoned judgment. The PMBoG ILE helped the players to embrace the complexity characterizing a typical project management intervention, having at their disposal various sources of information and using them to plan activities and carry out actions. The potential of SD principles and tools, in this specific context, supported the players in understanding how complex patterns of events, actions, and consequences were formed within the game, at the same time identifying the role played by critical factors such as time.

- The ability of evaluation involves assessing the credibility and relevance of information, evaluating arguments, and determining the strengths and weaknesses of different viewpoints. The ILE provided a safe environment where all the information was continuously at the players’ disposal, performances were assessed in real time, and feedback about decisions and actions was provided to the players using several tools (graphs, scores, visual aids such as traffic lights, tables, etc.)

- In the PMBoG ILE, the skill of inference, which involves drawing conclusions based on available evidence and making predictions about future events based on past experiences and patterns, was critically linked to the players’ ability to plan activities, carry them out, assess the gap in terms of expected results, and adopt corrective actions, mostly according to negative balance feedback-driven reasoning.

- The ability of interpretation, which entails understanding the meaning of information, analyzing its significance, and applying it to new situations, was greatly enhanced within the PMBoG ILE. Players were called on to play the role of a wedding planner, but this role might be easily shifted to the management of a variety of other projects, all of them relying on similar underlying systemic structures.

- The ability of explanation (which involves communicating complex ideas or concepts in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate evidence and reasoning to support arguments) was not directly evident from the results of the PMBoG ILE, but it came to life when the players were interviewed and were required to explain their strategies and experiences. The excerpts we report in Table 8 and within the text can provide examples of this.

- Last, the skill of self-regulation, i.e., the ability that involves monitoring one’s own thinking and behavior, recognizing biases and assumptions, and adjusting one’s approach based on feedback and new information, was challenged within the PMBoG ILE. Players tended to approach the game heavily relying on their mental models and background, but also became able to exploit this experience as the game progressed.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Ideas for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dewey, J. How We Think; D.C. Heat & Co. Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Huitt, W. Critical thinking: An overview. Educ. Psychol. Interact. 1998, 3, 34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, D.F. Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking; Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, M.F.; Auriac, E. Philosophy, critical thinking and philosophy for children. Educ. Philos. Theory 2011, 43, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriven, M.; Paul, R. Critical thinking. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and Education Reform, Summer, CA, USA; 1987; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla, M.J.; Fernández-Nogueira, D.; Poblete, M.; Galindo-Domínguez, H. Methodologies for teaching-learning critical thinking in higher education: The teacher’s view. Think. Ski. Creat. 2019, 33, 100584. [Google Scholar]

- Gosner, W. “Critical Thinking”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 September 2023. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/critical-thinking (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J.G.; Klebba, J.M. Experiential learning: A course design process for critical thinking. Am. J. Bus. Educ. 2011, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, B. Strategies for teaching critical thinking. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 1994, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, J.F.; Lightle, S.; Baker, B. A strategy for teaching critical thinking: The sellmore case. Manag. Account. Q. 2017, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchino, M.I. Using game-based learning to foster critical thinking in student discourse. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2015, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.D. Enhanced critical thinking skills through problem-solving games in secondary schools. Interdiscip. J. E-Ski. Lifelong Learn. 2017, 13, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendi, A. Improve critical thinking skills with informatics educational games. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 6, 521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, E.; Wildman, J.L.; Piccolo, R.F. Using simulation-based training to enhance management education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2009, 8, 559–573. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D.C. On a resurgence of management simulations and games. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1995, 46, 604–625. [Google Scholar]

- Barnabè, F. Policy Deployment and Learning in Complex Business Domains: The Potentials of Role Playing. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Barnabé, F.; Ciobanu, N.; Kulakowska, M. Interactive “Boardgame-Based” Learning Environments for Decision-makers’ Training in Managerial Education, 2020 White Paper. Available online: https://www.pmbog.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Interactive-Learning-Environments-for-education.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Atkinson, R.K.; Renkl, A. Interactive example-based learning environments: Using 6 interactive elements to encourage effective processing of worked examples. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 19, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsen, P.I. Issues in the design and use of system-dynamics-based interactive learning environments. Simul. Gaming 2000, 31, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, J.M.; Davidsen, P.I. Constructing learning environments using system dynamics. J. Coursew. Eng. 1998, 1, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Papert, S. Mindstorms; Basic Books Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. The Reflective Practitioner; Basic Books Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Alessi, S.; Kopainsky, B. System dynamics and simulation/gaming: Overview. Simul. Gaming 2015, 46, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopainsky, B.; Alessi, S.M. Effects of structural transparency in system dynamics simulators on performance and understanding. Systems 2015, 3, 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morecroft, J.D.W. System dynamics and microworlds for policymakers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1988, 35, 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J.D. Teaching Takes Off: Flight Simulators for Management Education. OR/MS Today 1992, 19, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsen, P.I.; Spector, J.M. Critical reflections on system dynamics and simulation/gaming. Simul. Gaming 2015, 46, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D.; Dogan, G. “I’m not hoarding, I’m just stocking up before the hoarders get here.”: Behavioral causes of phantom ordering in supply chains. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 39, 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kunc, M.; Malpass, J.; White, L. (Eds.) Behavioral Operational Research: Theory, Methodology and Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D.C. ‘Behavioural System Dynamics’: A very tentative and slightly sceptical map of the territory. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2017, 34, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnabè, F.; Davidsen, P.I. Exploring the potentials of behavioral system dynamics: Insights from the field. J. Model. Manag. 2020, 15, 339–364. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D.C.; Rouwette, E.A. Towards a behavioural system dynamics: Exploring its scope and delineating its promise. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 777–794. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J.W. Industrial Dynamics; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J.W. Principle of Systems; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lyneis, J.M.; Ford, D.N. System dynamics applied to project management: A survey, assessment, and directions for future research. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2007, 23, 157–189. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, P. Critical thinking in nursing education and practice as defined in the literature. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2005, 26, 272–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bers, T. Assessing critical thinking in community colleges. New Dir. Community Coll. 2005, 130, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facione, P.A. Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Insight Assess. 2011, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Behar-Horenstein, L.S.; Niu, L. Teaching critical thinking skills in higher education: A review of the literature. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 2011, 8, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, N.J. Teaching Critical Thinking Skills: Literature Review. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol.-TOJET 2020, 19, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R.M.; Zhang, D.; Abrami, P.C.; Sicoly, F.; Borokhovski, E.; Surkes, M.A. Exploring the structure of the Watson–Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal: One scale or many subscales? Think. Ski. Creat. 2008, 3, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkharusi, H.A.; Al Sulaimani, H.; Neisler, O. Predicting Critical Thinking Ability of Sultan Qaboos University Students. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, H.; Rogers, G.; King, J. Using portfolios to stimulate critical thinking in social work education. Soc. Work Educ. 2002, 21, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles-González, J.; Solano-Ruiz, C. Self-assessment, reflection on practice and critical thinking in nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 45, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankaraš, M.; Suarez-Alvarez, J. Assessment Framework of the OECD Study on Social and Emotional Skills; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, L.E.; Lindell, D.; Sullivan, A.M.; Huang, G.C. Clear skies ahead: Optimizing the learning environment for critical thinking from a qualitative analysis of interviews with expert teachers. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.; Lai, P.; So, M.; Yuen, K. A comparison of the effects of problem-based learning and lecturing on the development of students’ critical thinking. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zepeda, S.J. Classroom-based assessments of teaching and learning. In Evaluating Teaching: A Guide to Current Thinking and Best Practice; Corwin Press, Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, B. Systems thinking: Critical thinking skills for the 1990s and beyond. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 1993, 9, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.J. Business simulation games: Current usage levels—An update. Simul. Gaming 1998, 29, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.J.; Hutchinson, D.; Wellington, W.J.; Gold, S. Developments in business gaming: A review of the past 40 years. Simul. Gaming 2009, 40, 464–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Barnabè, F.; Pompei, A. Game-Based Learning and Decision-Making for Urban Sustainability: A Case of System Dynamics Simulations. In EURO Working Group on DSS: A Tour of the DSS Developments over the Last 30 Years; Jason Papathanasiou, J., Zaraté, P., Freire de Sousa, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Klabbers, J.H. Social problem solving: Beyond method. In Back to the Future of Gaming; Duke, R.D., Kriz, W.C., Eds.; Bertelsmann Verlag GmbH & Co. KG: Bielefeld, Germany, 2014; pp. 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Palmunen, L.M.; Pelto, E.; Paalumäki, A.; Lainema, T. Formation of novice business students’ mental models through simulation gaming. Simul. Gaming 2013, 44, 846–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellington, W.J.; Faria, A.J.; Whiteley, T.R. Holistic cognitive strategy in a computer-based marketing simulation game: An investigation of attitudes towards the decision-making process. In Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning: Proceedings of the Annual ABSEL Conference, Hawaii; 1998; Volume 25, pp. 246–252. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. A brief and incomplete history of operational gaming in system dynamics. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2007, 23, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennix, J.A.M. Group Model Building: Facilitating Team Learning Using System Dynamics; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J.D. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; Irwin McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J.D. System Dynamics Modeling for Project Management; System Dynamics Group, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, A.; Bowers, J. System dynamics in project management: A comparative analysis with traditional methods. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 1996, 12, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Bowers, J. The role of system dynamics in project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1996, 14, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D.N.; Lyneis, J.M. System Dynamics Applied to Project Management: A Survey, Assessment, and Directions for Future Research. In System Dynamics; Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science Series; Dangerfield, B., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 285–314. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R. Projects and their management. In Gower Handbook of Project Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Leotta, A. Capitalizing and controlling development project as joint traslations. The mediating role of the information technology. Manag. Control 2015, 2, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, D. Project Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.K.; Mantel, S.J. The causes of project failure. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1990, 37, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmad, W.; Al-Fagih, K.; Khanfar, K.; Alsamara, K.; Abuleil, S.; Abu-Salem, H. A taxonomy of an IT project failure: Root causes. Int. Manag. Rev. 2009, 5, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lyneis, J.M.; Cooper, K.G.; Els, S.A. Strategic management of complex projects: A case study using system dynamics. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2001, 17, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumeser, D.; Emsley, M. Key challenges of system dynamics implementation in project management. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 230, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.G.; Williams, T.M. System dynamics in project management: Assessing the impacts of client behaviour on project performance. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1998, 49, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Daalen, C.; Schaffernicht, M.; Mayer, I. System dynamics and serious games. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, Delft, The Netherlands, 20–24 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, M.D.; Gencheva, M.; Gunther, M.R.; Weed, S.A. Training doctoral students in critical thinking and experimental design using problem-based learning. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; SAGE Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J.D.; Gowin, D.B. Learning How to Learn; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Videira, N.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Lopes, R. A participatory modelling approach to support integrated sustainability assessment processes. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2010, 27, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M.; Forrester, J.W. Tests for building confidence in system dynamics models. Syst. Dyn. TIMS Stud. Manag. Sci. 1980, 14, 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Barlas, Y. Formal aspects of model validity and validation in system dynamics. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 1996, 12, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D. A System Dynamics Glossary. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2019, 35, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.T.; Stanley, J.C.; Gage, N.L. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

| Choice | PMBoG ILE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Purpose | Manage a project by making decisions, planning activities, carrying out actions, measuring results, and learning. |

| 2 | Insights obtained | Context-specific competencies (in the field of PM) and systems thinking skills (generally transferrable). |

| 3 | Plot | Planning of a wedding ceremony. |

| 4 | Player(s) | Various categories of learners. |

| 5 | Role(s) | Wedding planner. |

| 6 | Objective in-game/incentive | Complete all the tasks on time, with the budget at the user’s disposal, and fulfilling all the requests.Subsequently, the highest score possible. |

| 7 | Rules | Budget constraints; time constraints; and capacity constraints. |

| 8 | Representation of physical system | Fictitious, computer-based in the form of an ILE. |

| 9 | Representation of inter-actor environment | Not present (single-player online game). |

| Couple Card | The Information Displayed on the Card |

|---|---|

| A = Name and image of the couple; B = Preferred symbols; C = Liked symbols; D = Disliked symbols; E = Perfect marriage combination. |

| Task Card Icon | Task Card Typology |

|---|---|

| Restaurant |

| Location |

| Dress |

| Announcements |

| Rings |

| Photographer |

| Task Card | Information Displayed by the Card |

|---|---|

| A = Card color; B = Card task symbol; C = Task cost; D = Task risk flavor; E = Task risk number; F = Workload required; G = Requested symbols; H = Pre-requisites. |

| Decision | Decision Levers in the ILE | Information |

|---|---|---|

| Allocate the staff to selected tasks | Player’s decision REST workload Player’s decision LOCATION workload Player’s decision DRESS workload Player’s decision ANNOUN workload Player’s decision RINGS workload Player’s decision PHOTOG workload | The user specifies the amount of workload they want to assign to each specific task and for that specific month. Each task to be completed requires a specific workload, as detailed by the task cards on their front sides. The total amount of workload that can be assigned to the six tasks is constrained by the staff at the user’s disposal (i.e., by the total workload available). |

| Mitigate risks | Player’s decision REST risk mitigation Player’s decision LOCATION risk mitigation Player’s decision DRESS risk mitigation Player’s decision ANNOUN risk mitigation Player’s decision RINGS risk mitigation Player’s decision PHOTOG risk mitigation | The user can mitigate the various risks associated with the six tasks of the game by investing money. Mitigating risks will reduce the possibility that such risks will happen. The amount of money to be spent to this aim is detailed on the rear sides of the task cards. |

| Hire junior workers | Juniors to HIRE | The user can decide to increase their staff by hiring new employees. Such workers will be “juniors”, i.e., less productive ones, if compared to seniors. After a delay time, the juniors become more experienced, i.e., they become seniors. |

| Release seniors | Seniors to RELEASE | The user can reduce their staff by releasing senior workers. This will reduce the staff and the total workload at the user’s disposal but will also reduce the costs. |

| Activate temporary workers | Temporary worker | If in need of more staff (and quickly), the user can activate a temporary worker. This employee will work on the project only for one month and will be subsequently and automatically released. |

| Work on utility card-related activities | Workload on utility card 1 Workload on utility card 1 Workload on utility card 1 | Depending on the utility card that is randomly assigned to the user at the beginning of the game, the user will have to assign a workload to such a task. This action is constrained by the staff at the user’s disposal (i.e., by the total workload available). |

| Points Scored Category | Information |

|---|---|

| +3 points | Per request symbol in your completed task cards that matches the preferred couple card |

| +1 point | Per request symbol in your completed task cards that matches the liked couple card |

| −1 point | Per request symbol in your completed task cards that matches the disliked couple card |

| +5 points | Per perfect marriage bonus if you have all the request symbols on your completed task cards that match the perfect request on your couple card |

| −3 points | Per not completed/absent task type |

| +3 points | To the player who has the most remaining coins |

| −1 point | Every two debts (rounded) |

| Pre-requisite | The “special need“ card must be fulfilled. |

| Graph | Description |

|---|---|

| Tasks to be completed Tasks completed counter | This graph shows the number of tasks to be completed (no. 6 at the beginning of the game) compared to the tasks completed by the user at any specific time of the simulation. |

| REST task completion signal (ILE) LOCAT task completion signal (ILE) | This graph shows if the tasks associated with choosing a restaurant (i.e., REST) and/or a location (i.e., LOCAT) for the ceremony have been completed (value = 1), are partially completed (value = 0.5), or have not been worked on yet (value = 0). These are the purple tasks in the game. |

| ANNOUN task completion signal (ILE) DRESS task completion signal (ILE) | This graph shows if the tasks associated with making the announcements (i.e., ANNOUN) and/or choosing the dresses (i.e., DRESS) for the ceremony have been completed (value = 1), are partially completed (value = 0.5), or have not been worked on yet (value = 0). These are the yellow tasks in the game. |

| RINGS task completion signal (ILE) PHOTOG task completion signal (ILE) | This graph shows if the tasks associated with choosing the rings (i.e., RINGS) and/or a photographer (i.e., PHOTOG) for the ceremony have been completed (value = 1), are partially completed (value = 0.5), or have not been worked on yet (value = 0). These are the red tasks in the game. |

| Budget | This graph shows the level of the budget at the user’s disposal at any time during the simulation. The user starts the game with a budget of EUR 30,000. The user can use more than the available budget, even though this will incur a penalization in the final score. |

| Junior staffSenior staffTemporary worker | This graph shows the staff at the user’s disposal at any time during the simulation. There are three typologies of workers:

|

| Potential workload available Workload allocated by player | The potential workload available during the simulation is given by the staff (the no. of workers for each category of staff) multiplied by the employees’ productivity (each category of workers has a different productivity level). The workload allocated by the player shows how the user uses the potential workload at their disposal to complete the tasks. The comparison between these two variables makes clear if there is capacity not currently used by the player. |

| Player No. | Strategy and Feedback | Additional Features in/for the Game | Final Score | RisksIncurred |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I tried to fulfill the Posh couple’s wishes by completing all the required tasks on time and in the correct sequence. It wasn’t easy, because the options that became available in the ILE weren’t always the best, and I didn’t manage to carry out all the actions in parallel, using properly the workforce at my disposal. In the end, I also had to hire some temporary workers, because the pressure I felt to complete my task was very high. | None. | +5 | None. |

| 2 | I had fun and I think I did quite well even though I couldn’t complete all the tasks required for the wedding. Maybe I’ve been worrying too much about managing the budget and staffing, and this has caused me to pay less attention to the time needed to complete the tasks. | More planning time. | +9 | None. |

| 3 | I completed the six types of tasks that were requested, but they weren’t the best possible ones, i.e., they weren’t exactly the ones associated with the couple I had chosen. Not all cards were perfect in that regard. Anyhow, I tried to complete my task and make the wedding happen. However, I spent all the available budget, and I must say that I was not able to mitigate the risk well. In the end, I’m happy, but I’d like to try the game again, to improve my strategy. | Repeat the game with the same conditions. | +10 | More budget needed. |

| 4 | I nearly completed the overall task, but I was not able to actually do that due to some mistakes I made. For example, I chose one wrong option during the planning phase, and this messed up my execution. I subsequently had to rush things and go for sub than optimal options. I definitely felt a bit of pressure to perform, and this made me further rush a couple of decisions. Overall, I think I learnt a lot, and the game pushed me to think about the wedding as a project, with all that this would entail. | Play a competitive game against other players. | +5 | Rework cycle. |

| 5 | I tried to complete all the tasks, without succeeding. I understood that priorities, schedule, budget availability, resources, and time cannot be always managed simultaneously and that it is difficult to find an optimal strategy. Anyhow, I understood that the planning phase and the execution phase are to be managed carefully, and all the resources are to be employed accordingly. | Play again, relying on the knowledge gained in previous attempts. | +2 | Rework cycle. |

| 6 | I felt good playing the game. I really like simulations and games, and this is a nice example of a management-related game. Actually, I struggled to complete all the tasks, but I definitely tried to use all the options and resources at my disposal. | None. | +3 | None. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barnabè, F.; Armenia, S.; Nazir, S.; Pompei, A. Critical Thinking Skills Enhancement through System Dynamics-Based Games: Insights from the Project Management Board Game Project. Systems 2023, 11, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110554

Barnabè F, Armenia S, Nazir S, Pompei A. Critical Thinking Skills Enhancement through System Dynamics-Based Games: Insights from the Project Management Board Game Project. Systems. 2023; 11(11):554. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110554

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarnabè, Federico, Stefano Armenia, Sarfraz Nazir, and Alessandro Pompei. 2023. "Critical Thinking Skills Enhancement through System Dynamics-Based Games: Insights from the Project Management Board Game Project" Systems 11, no. 11: 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110554

APA StyleBarnabè, F., Armenia, S., Nazir, S., & Pompei, A. (2023). Critical Thinking Skills Enhancement through System Dynamics-Based Games: Insights from the Project Management Board Game Project. Systems, 11(11), 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11110554