Antecedents and Consequences of the Ease of Use and Usefulness of Fast Food Kiosks Using the Technology Acceptance Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Fast Food Kiosk

2.2. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

3. Method

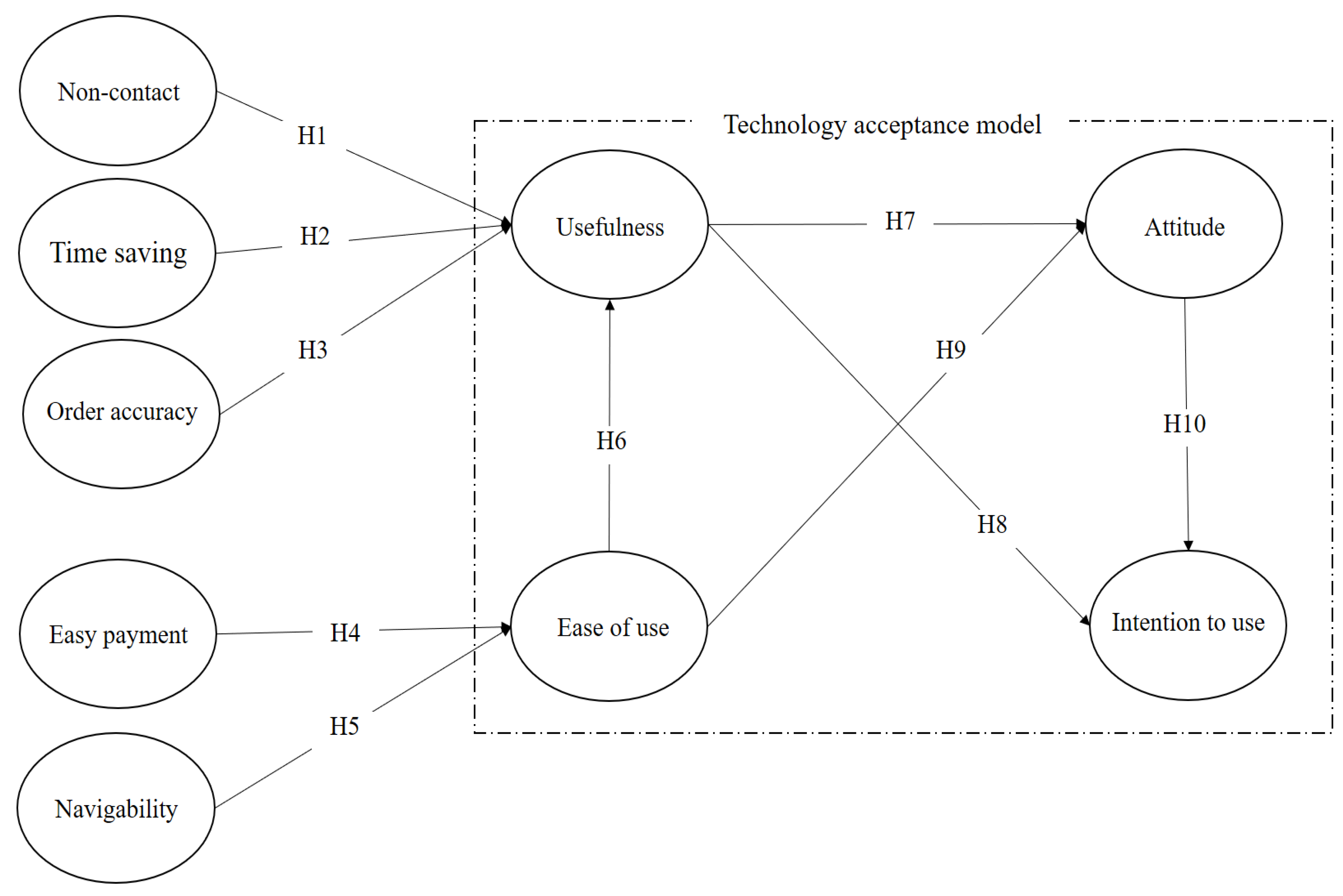

3.1. Research Model and Data Collection Methods

3.2. Depiction of Measurement Items

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and the Correlation Matrix

4.3. Results of Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forbes. Self-Order Kiosks Are Finally Having a Moment in the Fast Food Space. 2019. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/aliciakelso/2019/07/30/self-order-kiosks-are-finally-having-a-moment-in-the-fast-food-space/?sh=3566e4164275 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Restaurant Business. Big Fast Food Chains Find Their Digital Footing. 2022. Available online: https://www.restaurantbusinessonline.com/technology/big-fast-food-chains-find-their-digital-footing (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Ketimin, S.; Shami, S. An insight of customer’s behavior intention to use self-service kiosk in Melaka fast food restaurant. J. Technol. Manag. Technopreneurship 2021, 9, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Lehto, X.; Lehto, M. Self-service technology kiosk design for restaurants: An QFD application. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. A study on user experience of unmanned payment kiosk system in fast food restaurants. Int. J. Smart Bus. Technol. 2020, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, N.A. The user experience (UX) analysis of self-Service Kiosk (SSK) in waiting time at fast food restaurant using user experience (UX) model. J. Soc. Transform. Reg. Dev. 2021, 3, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel, J.; Diatha, K.; Yadavalli, V. An application of the extended technology acceptance model in understanding technology-enabled financial service adoption in South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 2013, 30, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G. Age and gender differences in online travel reviews and user-generated-content (UGC) adoption: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM) with credibility theory. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Chang, L.L.; Yu, C.P.; Chen, J. Examining an extended technology acceptance model with experience construct on hotel consumers’ adoption of mobile applications. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Qu, H. Travelers’ behavioral intention toward hotel self-service kiosks usage. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 225–245. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A.A.; Pentina, I.; Mishra, A.; Ben Mimoun, M. Mobile payments adoption by US consumers: An extended TAM. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Order Mate. The Top Benefits of Self-Service Kiosks in the Food Industry. 2018. Available online: https://www.ordermate.com.au/blog/the-top-4-benefits-of-self-service-kiosks-in-food-industry (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Li, C.; Li, F.; Fan, P.; Chen, K. Voicing out or switching away? A psychological climate perspective on customers’ intentional responses to service failure. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102361. [Google Scholar]

- Yaacob, S.; Aziz, A.; Bakhtiar, M.; Othman, Z.; Ahmad, N. A concept of consumer acceptance on the usage of self-ordering kiosks at McDonald’s. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Schepers, J. Robots or frontline employees? Exploring customers’ attributions of responsibility and stability after service failure or success. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 31, 267–289. [Google Scholar]

- Insider. 14 Ways Fast-Food Chains Have Changed Because of the Coronavirus Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/ways-fast-food-will-be-different-after-the-coronavirus-pandemic-2020-5 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Moon, H.; Lho, H.; Han, H. Self-check-in kiosk quality and airline non-contact service maximization: How to win air traveler satisfaction and loyalty in the post-pandemic world? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, K.B.; Tan, G. Mobile technology acceptance model: An investigation using mobile users to explore smartphone credit card. Exp. Sys. App. 2016, 59, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UX Collective. McDonald’s Kiosk Ordering System—A UX Case Study. 2019. Available online: https://uxdesign.cc/mcdonalds-kiosk-ordering-system-ui-ux-case-study-fe7b3693f12c (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Naqvi, S.; Burdi, A.; Chandio, F.; Abbasi, M.; Arijo, N.; Abbasi, F. Usability dimensions and their impact on web-based transactional systems acceptance: An empirical examination. Sin. Univ. Res. J. 2018, 50, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.R. The effect of fast food restaurant customers’ kiosk use on acceptance intention and continuous use intention: Applying UTAUT2 model and moderating effect of familiarity. J. Tour. Sci. 2020, 44, 207–228. [Google Scholar]

- Na, T.K.; Yang, J.Y.; Lee, S.H. Determinants of behavioral intention of the use of self-order kiosks in fast-food restaurants: Focus on the moderating effect of difference age. SAGE Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.H. A study on the application of kiosk service as the workplace flexibility: The determinants of expanded technology adoption and trust of quick service restaurant customers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A. A strategic approach for managing COVID-19 crisis: A food delivery industry perspective. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2021, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, H.; Kang, M.; Suh, S.C. Machine learning of robots in tourism and hospitality: Interactive technology acceptance model (iTAM)—cutting edge. Tour Rev. 2020, 75, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, D. Untact: A new customer service strategy in the digital age. Serv. Bus. 2020, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.J.; Jeon, H.M. Untact: Customer’s acceptance intention toward robot barista in coffee shop. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D. Contactless technologies adoption during the coronavirus pandemic: A combined technology acceptance and health belief perspective. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kwon, K.H. Recognition and the development potential of mobile shopping of customized cosmetic on untact coronavirus disease 2019 period: Focused on 40’s to 60’s women in Seoul, Republic of Korea. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 1975–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Working wives’ time-saving tendencies: Durable ownership, convenience food consumption, and meal purchases. J. Econ. Psychol. 1989, 10, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.B.; DeVoe, S. You are how you eat: Fast food and impatience. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Chaouali, W.; Baccouche, M. Consumers’ attitude and adoption of location-based coupons: The case of the retail fast food sector. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 116–132. [Google Scholar]

- Abroud, A.; Choong, Y.V.; Muthaiyah, S.; Fie, D.Y. Adopting e-finance: Decomposing the technology acceptance model for investors. Serv. Bus. 2015, 9, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, R.; Alpass, F.; Humphries, S.; Massey, C.; Morriss, S.; Long, N. The technology acceptance model and use of technology in New Zealand dairy farming. Agric. Syst. 2004, 80, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yoo, Y. It’s all about attitude: Revisiting the technology acceptance model. Decis. Support Syst. 2004, 38, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Chen, H.; Lee, Y.M. COVID-19 preventive measures and restaurant customers’ intention to dine out: The role of brand trust and perceived risk. Serv. Bus. 2021, 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S.E. The current state of online food ordering in the US restaurant industry. Cornell Cent. Hosp. Res. 2011, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, J.E.; Bienstock, C. Measuring service quality in e-retailing. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 8, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, A.; Kumar, N.; Wen, S.; Kee, D.; Er, T.; Xin, T.; Yuan, Y.J.; Hasifa, M.; Yadav, V.; Nair, R.K.; et al. Factors influencing consumer behaviour: A case of McDonald’s. Adv. Glob. Econ. Bus. J. 2020, 1, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bejou, D.; Palmer, A. Service failure and loyalty: An exploratory empirical study of airline customers. J. Serv. Mark. 1998, 12, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M.; Roy, S.; Quazi, A. Customers’ emotion regulation strategies in service failure encounters. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 960–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, D. Evaluating electronic commerce acceptance with the technology acceptance model. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2004, 44, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Salloum, S.A.; Al-Emran, M. Factors affecting the adoption of E-payment systems by university students: Extending the TAM with trust. Int. J. Electron. Bus. 2018, 14, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Mirusmonov, M.; Lee, I. An empirical examination of factors influencing the intention to use mobile payment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 310–322. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Ghatak, S. Investigating E-Wallet adoption in India: Extending the TAM model. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 2021, 17, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A. Customer acceptance of cashless payment systems in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.T.; Pearson, J.M. Integrating website usability with the electronic commerce acceptance model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2011, 30, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Asan, O.; Wozniak, E.; Flynn, K.; Scanlon, M. Nurses’ perceptions, acceptance, and use of a novel in-room pediatric ICU technology: Testing an expanded technology acceptance model. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Shephard, A.J.; Pookulangara, S.A. Student use of university digital collections: The role of technology and educators. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimiagari, S.; Malafe, N. The role of cognitive and affective responses in the relationship between internal and external stimuli on online impulse buying behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102567. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhou, R.; Luo, X.R. A meta-analysis of online impulsive buying and the moderating effect of economic development level. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson, M.J.; Vidgen, R. A computational literature review of the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Development of an adoption model to assess user acceptance of e-service technology: E-Service technology acceptance model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rong, W.; Ma, X.; Qu, Y.; Xiong, Z. An extended technology acceptance model for mobile social gaming service popularity analysis. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2017, 2017, 3906953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Granić, A. Is it still valid or outdated? A bibliometric analysis of the technology acceptance model and its applications from 2010 to 2020. In Recent Advances in Technology Acceptance Models and Theories; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sahli, A.B.; Legohérel, P. The tourism web acceptance model: A study of intention to book tourism products online. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Sharma, A.; Ouyang, Y. Role of signals in consumers’ economic valuation of restaurant choices. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 1080–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, L.; Ali, F. Perceived risks related to unconventional restaurants: A perspective from edible insects and live seafood restaurants. Food Control. 2022, 131, 108471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Leung, X.; Pongtornphurt, Y. Exploring the impact of background music on customers’ perceptions of ethnic restaurants: The moderating role of dining companions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Lee, M.Y.; Shen, H. What drives consumers in China to buy clothing online? Application of the technology acceptance model. J. Text. Fibrous Mater. 2018, 1, 2515221118756791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.; Lee, H. A First Course In Factor Analysis; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Emran, M.; Mezhuyev, V.; Kamaludin, A. Technology acceptance model in M-learning context: A systematic review. Comp. Edu. 2018, 125, 389–412. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Non-contact | NC1 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant helped non-contact consumption. |

| NC2 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant enabled consumption without employee contact. | |

| NC3 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant enabled me to consume without employee contact. | |

| NC4 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant was a tool for non-contact consumption. | |

| Time saving | TS1 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant was good for saving time. |

| TS2 | I could save time by using the self-service kiosk at a fast food restaurant. | |

| TS3 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant reduced the waiting time for food. | |

| TS4 | The time spent obtaining food was decreased by using the self-service kiosk at fast food restaurant. | |

| Order accuracy | OA1 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant made my order more precisely. |

| OA2 | I could make a more accurate order by using the self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant. | |

| OA3 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant enhanced the accuracy of the food order. | |

| OA4 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant minimized the error in making a food order. | |

| Easy payment | EP1 | It was easy to pay at the self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant. |

| EP2 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant had a payment system that was not difficult. | |

| EP3 | Payment at the self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant was uncomplicated. | |

| EP4 | I could pay effortlessly at the self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant. | |

| Navigability | NA1 | It was easy to navigate the self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant. |

| NA2 | It was simple to find the menu at the self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant. | |

| NA3 | It was effortless to find the product information at the self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant. | |

| NA4 | The self-service kiosk at the fast food restaurant was easy to navigate. | |

| Ease of use | EU1 | The self-service kiosk was easy to use. |

| EU2 | It was straightforward to use the self-service kiosk. | |

| EU3 | The self-service kiosk was a simple system to use. | |

| EU4 | For me, it was straightforward to control the self-service kiosk. | |

| Usefulness | UF1 | Using the self-service kiosk allowed me to obtain the food speedily at the fast food restaurant. |

| UF2 | Using the self-service kiosk enabled me to attain the product more quickly at the fast food restaurant. | |

| UF3 | Using the self-service kiosk improved my product purchasing experience at the fast food restaurant. | |

| UF4 | Using the self-service kiosk enhanced the effectiveness of buying goods at the fast food restaurant. | |

| Attitude | AT1 | The self-service kiosk at fast food restaurant is (Negative–Positive) |

| AT2 | The self-service kiosk at fast food restaurant is (Unattractive–Attractive) | |

| AT3 | The self-service kiosk at fast food restaurant is (Unfavorable–Favorable) | |

| AT4 | The self-service kiosk at fast food restaurant is (Bad–Good) | |

| Intention to use | IU1 | I intend to use the self-service kiosk at fast food restaurants. |

| IU2 | I am going to use the self-service kiosk at fast food restaurants. | |

| IU3 | The self-service kiosk will be chosen for my shopping at fast food restaurants. | |

| IU4 | I will use the self-service kiosk at fast food restaurants. |

| Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 209 | 60.4 |

| Female | 137 | 39.6 |

| 20 s or younger | 102 | 29.5 |

| 30 s | 133 | 38.4 |

| 40 s | 58 | 16.8 |

| 50 s | 33 | 9.5 |

| Older than 60 | 20 | 5.8 |

| Unemployed | 50 | 14.5 |

| Employed | 296 | 85.5 |

| Monthly household income | ||

| Less than USD 2000 | 70 | 20.2 |

| USD 2000~USD 3999 | 97 | 28 |

| USD 4000~USD 5999 | 75 | 21.7 |

| USD 6000~USD 7999 | 69 | 11.3 |

| More than USD 8000 | 65 | 18.8 |

| Weekly kiosk using frequency | ||

| Less than 1 time | 111 | 32.1 |

| 1~2 times | 148 | 42.8 |

| 3~5 times | 57 | 16.5 |

| More than 5 times | 30 | 8.7 |

| Construct (AVE) | Code | Mean | SD | Loading | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-contact (0.673) | NC1 | 4.15 | 0.98 | 0.723 | 0.673 |

| NC2 | 4.07 | 0.97 | 0.881 | ||

| NC3 | 4.09 | 1 | 0.859 | ||

| NC4 | 4.09 | 0.97 | 0.809 | ||

| Time saving (0.697) | TS1 | 4.03 | 1.06 | 0.87 | 0.697 |

| TS2 | 4.02 | 1.06 | 0.864 | ||

| TS3 | 3.89 | 1.13 | 0.807 | ||

| TS4 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.795 | ||

| Order accuracy (0.668) | OA1 | 3.98 | 1.04 | 0.801 | 0.668 |

| OA2 | 4.04 | 1.02 | 0.827 | ||

| OA3 | 4.01 | 1 | 0.841 | ||

| OA4 | 4.01 | 1.02 | 0.799 | ||

| Easy payment (0.706) | EP1 | 4.18 | 0.97 | 0.844 | 0.706 |

| EP2 | 4.12 | 1.02 | 0.825 | ||

| EP3 | 4.02 | 1.07 | 0.827 | ||

| EP4 | 4.1 | 1.03 | 0.865 | ||

| Navigability (0.702) | NA1 | 4.04 | 1.01 | 0.887 | 0.702 |

| NA2 | 4.16 | 0.94 | 0.814 | ||

| NA3 | 4 | 0.99 | 0.796 | ||

| NA4 | 4.04 | 1 | 0.85 | ||

| Ease of use (0.728) | EU1 | 4.24 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.728 |

| EU2 | 4.22 | 0.86 | 0.823 | ||

| EU3 | 4.21 | 0.9 | 0.866 | ||

| EU4 | 4.18 | 0.89 | 0.843 | ||

| Usefulness (0.679) | UF1 | 4.04 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.679 |

| UF2 | 4.02 | 1.01 | 0.793 | ||

| UF3 | 3.93 | 1.04 | 0.839 | ||

| UF4 | 3.98 | 0.99 | 0.844 | ||

| Attitude (0.794) | AT1 | 4.14 | 0.96 | 0.907 | 0.794 |

| AT2 | 4.08 | 0.99 | 0.845 | ||

| AT3 | 4.16 | 0.99 | 0.903 | ||

| AT4 | 4.18 | 0.96 | 0.908 | ||

| Intention to use (0.779) | IU1 | 4.05 | 1.06 | 0.876 | 0.779 |

| IU2 | 4.08 | 1.03 | 0.901 | ||

| IU3 | 3.96 | 1.06 | 0.865 | ||

| IU4 | 4.08 | 1.02 | 0.888 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Non-contact | 0.820 | ||||||||

| 2.Time saving | 0.686 * | 0.835 | |||||||

| 3.Order accuracy | 0.588 * | 0.687 * | 0.817 | ||||||

| 4.Easy payment | 0.676 * | 0.693 * | 0.626 * | 0.840 | |||||

| 5.Navigability | 0.646 * | 0.729 * | 0.724 * | 0.859 * | 0.838 | ||||

| 6.Usefulness | 0.687 * | 0.882 * | 0.709 * | 0.745 * | 0.776 * | 0.824 | |||

| 7.Ease of use | 0.605 * | 0.696 * | 0.631 * | 0.713 * | 0.823 * | 0.830 * | 0.853 | ||

| 8.Attitude | 0.655 * | 0.817 * | 0.699 * | 0.761 * | 0.811 * | 0.877 * | 0.815 * | 0.891 | |

| 9.Intention to use | 0.648 * | 0.800 * | 0.691 * | 0.722 * | 0.826 * | 0.908 * | 0.870 * | 0.886 * | 0.883 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moon, J.; Shim, J.; Lee, W.S. Antecedents and Consequences of the Ease of Use and Usefulness of Fast Food Kiosks Using the Technology Acceptance Model. Systems 2022, 10, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10050129

Moon J, Shim J, Lee WS. Antecedents and Consequences of the Ease of Use and Usefulness of Fast Food Kiosks Using the Technology Acceptance Model. Systems. 2022; 10(5):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10050129

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Joonho, Jimin Shim, and Won Seok Lee. 2022. "Antecedents and Consequences of the Ease of Use and Usefulness of Fast Food Kiosks Using the Technology Acceptance Model" Systems 10, no. 5: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10050129

APA StyleMoon, J., Shim, J., & Lee, W. S. (2022). Antecedents and Consequences of the Ease of Use and Usefulness of Fast Food Kiosks Using the Technology Acceptance Model. Systems, 10(5), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10050129