1. Introduction

Chinese tongue sole (

Cynoglossus semilaevis) is popularly distributed in northeast Asia. Due to its tender and juicy meat, Chinese tongue sole has high economic value, becoming one of the most important maricultural species in China [

1]. Over the past twenty years, large-scale breeding technology for Chinese tongue sole has been successfully developed, establishing it as an excellent model for industrial aquaculture. However, females grow 2–4 times faster than males, resulting in smaller adult males in actual aquaculture, which lowers economic returns.

Through fine mapping of the whole genome, Doublesex and Mab-3-related transcription factor 1 (

dmrt1) has been identified as a prime candidate crucial to male determination in Chinese tongue sole [

1]. In mammals,

dmrt1 is a conserved transcription factor required for male gonadal differentiation [

2]. Its paralog in medaka (

Oryzias latipes), known as

dmy, is a master sex-determining gene essential for testicular development [

3]. Meanwhile,

dmrt1 has been suggested as a male specific marker in Siamese fighting fish (

Betta splendens) [

4], yellow drum (

Nibea albiflora) [

5], African scat (

Scatophagus tetracanthus) [

6], and Nile tilapia (

Oreochromis niloticus) [

7]. In other teleost species,

dmrt1 shows male-biased expression during sex differentiation and testicular maturation, such as mandarin fish (

Siniperca chuatsi) [

8], cobia (

Rachycentron canadum) [

9], Pacific bluefin tuna (

Thunnus orientalis) [

10], spotted knifejaw (

Oplegnathus punctatus) [

11], and leopard coral grouper (

Plectropomus leopardus) [

12].

To further investigate the function of

dmrt1 gene in Chinese tongue sole, we established an efficient genome editing method for flatfish embryos by using TALEN-mediated knockout for the first time, and successfully generated

dmrt1 mutant individuals of the F0 generation [

13]. The

dmrt1+/− ZZ mutants displayed feminized characteristics, including sex-reverted gonads devoid of spermatids or sperm, as well as enhanced growth rates and higher body weight compared to wild-type males. Based on these findings, we propose that targeted knockout of

dmrt1 could be utilized to generate novel fast-growing strains of Chinese tongue sole through genome editing thereby addressing the issue of growth retardation in males. Importantly, the development of such a sterile, all-male strain also addresses key ethical and regulatory considerations. These sterile male fish might provide a strategy for controlling invasive fish species in natural habitats [

14]. Furthermore, the comprehensive phenotypic and metabolic data generated in this study provide valuable baseline information that may inform future assessments of genome-edited fish in aquaculture-related contexts.

In this study, we generated the F4 generation of dmrt1−/− ZZ mutants. According to our previous findings, their growth characters at 15 mph and their infertility were regarded as the primary outcomes. Their flesh quality was compared with wild-type tongues. Moreover, a muscle metabolomics investigation was carried out to explore the influence of dmrt1 on metabolic pathways. This work provided a valuable fast-growing strain for the Chinese tongue sole aquaculture industry, and offered a potential model for probing the molecular basis underlying sexual size dimorphism in teleost fish.

2. Materials and Methods

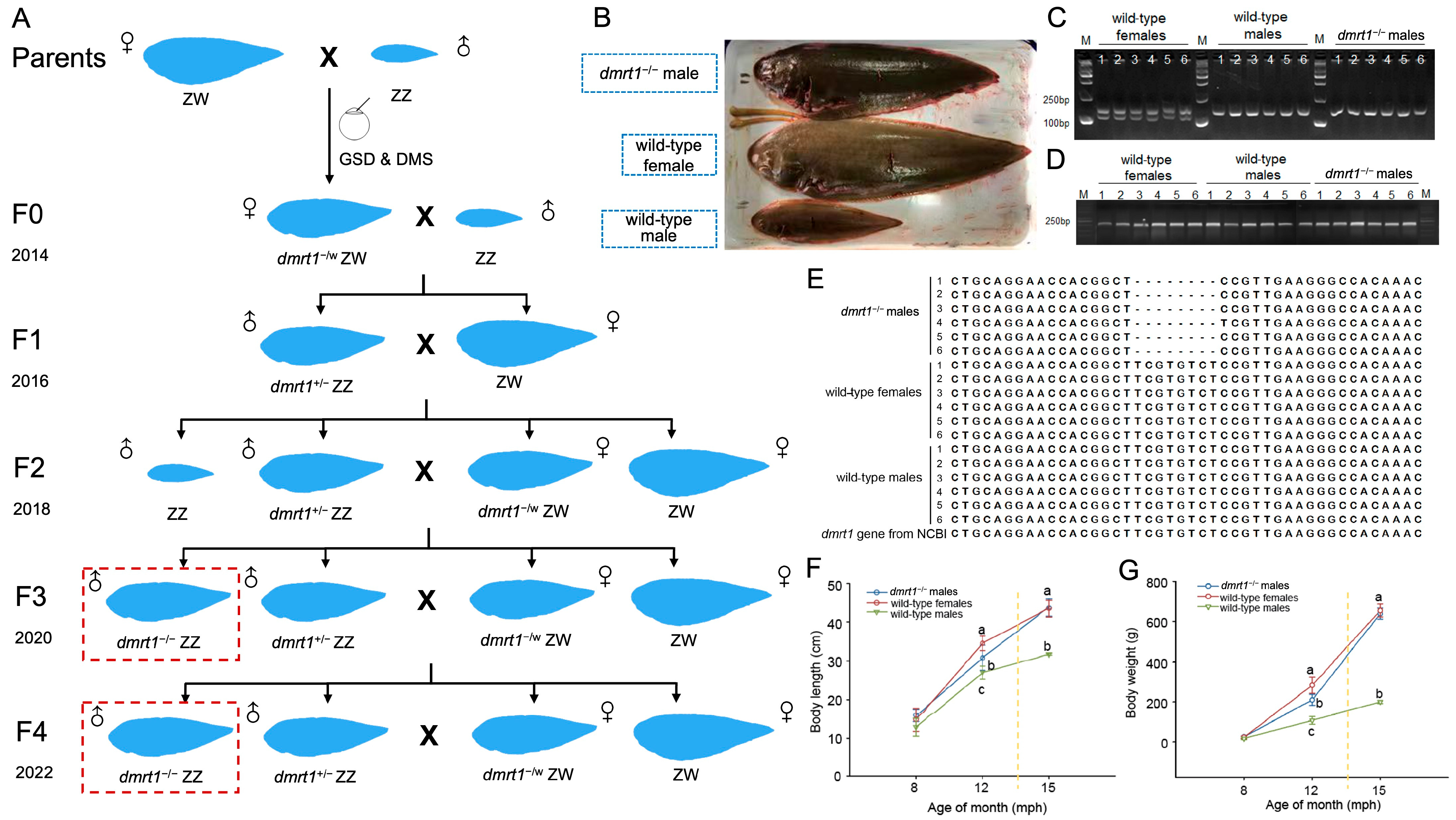

2.1. Experimental Fish

All fishes used in this study were cultured in Tangshan Weizhuo aquaculture Co., Ltd. (Tangshan, China). To induce spawning, mature broodstocks were injected with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH-A30.4, 4 μg/kg body weight) and domperidone (DOM, 1–2 mg/kg body weight) [

13]. For the F0 generation, we generated

dmrt1 knockout tongue sole by using TALEN-mediated genome editing following the protocol described by Cui et al. [

13]. Subsequently, all F0 individuals were subjected to genetic sex determination (GSD) and

dmrt1-mutation screening (DMS). DNA was extracted with TIANamp Marine Animal DNA kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). PCR amplification of GSD was performed using the sex-F/R primers (sex-F: 5′-CCTAAATGATGGATGTAGATTCTGTC3′, sex-R: 5′-GATCCAGAGAAAATAAACCCAGG-3′), and genetic sex was determined based on gel electrophoresis results. The

dmrt1 fragment containing mutant region was amplified using the

dmrt1-F/R primers (

dmrt1-F: 5′-CGGGCAAAGGGAGAAGG-3′ and

dmrt1-R: 5′-AAAAACATCTCCTGAGGGCTAA-3′) and sequenced by Tsingke (Beijing, China). All the PCR assays were performed following the procedures mentioned in Cui et al. [

13]. The breeding scheme for generating F1 through F4 generations is illustrated in

Figure 1A. For each subsequent generation, broodstock selection was based on combined GSD and DMS results. To assess potential off-target effects, genomic DNA was extracted from ten fish: three wild-type females, three wild-type males, and four

dmrt1−/− ZZ males. Whole-genome resequencing was performed by Novogene Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Potential off-target loci were provided by Cui et al., [

13]. Subsequently, the potential off-target sequence was identified by aligning the whole-genome resequencing data to the reference genome data of Chinese tongue sole.

Each concrete tank covered an area of 35 square meters. The stocking density decreased as the fish grew, with approximately 65 fish per square meter at 8 months post-hatch (mph), 30 fish per square meter at 12 mph, and 15 fish per square meter at 15 mph. The water temperature was maintained at 23–24 °C, with a salinity of 18–22‰. The photoperiod involved light exposure only during feeding and water discharge periods, totaling 3 h per day. Fish were fed a commercial diet twice daily (specifications: crude protein ≥ 52.0%, crude fat ≥ 9.0%, crude fiber ≤ 2.0%, crude ash ≤ 16.0%, lysine ≥ 2.5%). Fish were fasted for 24 h prior to experimentation or sampling. The

dmrt1−/− males and wild-type tongue soles were co-cultured in a pond at a 1:1:1 ratio, with a total of three such ponds set up at 8 mph. As the fish grew and stocking density decreased, they were redistributed into additional tanks. For each sampling event, healthy fish (free of skin ulcers, ascites, and skeletal deformities) were randomly selected from all available tanks and grouped using GSD and DMS. If the measurements of body weight and full length were required, the fish were returned to the rearing tank subsequent to fin clip sampling and data collection. If tissue sampling was required, MS222 (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada) was used for anesthesia to minimize fish suffering (solubilized in seawater, final concentration 20 mg/L, fish was treated for 5 min) during experimental procedure [

15].

2.2. Growth and Reproduction Performance Analysis

The full lengths and body weights were recorded from dmrt1−/− ZZ males and wild-type tongue soles at 8 mph, 12 mph, and 15 mph. The age at sampling was tightly controlled, with all samples collected within a one-week tolerance window (±1 week) of each target month. Thirty individuals were sampled for each group in each tank at one time point. Total body length was measured by a standardized ruler. The body weight was determined with an electronic scale.

To compare reproduction performance between

dmrt1−/− ZZ males and wild-type males, the eggs obtained through artificial induction from one wild-type female tongue sole were divided into two groups. One group was fertilized with sperm from wild-type males, and the other with sperm from

dmrt1−/− ZZ males. A single wild-type female can produce approximately 150 mL of eggs, with each milliliter containing roughly 1000 eggs. We harvested eggs from five wild-type females to repeat this experiment five times. Since the homozygous males were unable to release sperm by stripping [

13], their testes were dissected, minced, and mixed with the eggs for attempted in vitro fertilization. As the fertilized eggs of Chinese tongue sole are buoyant, those that sank to the bottom were considered non-viable. Floating eggs were collected at 10 and 24 h post-fertilization (hpf) for the observation of embryonic development stages.

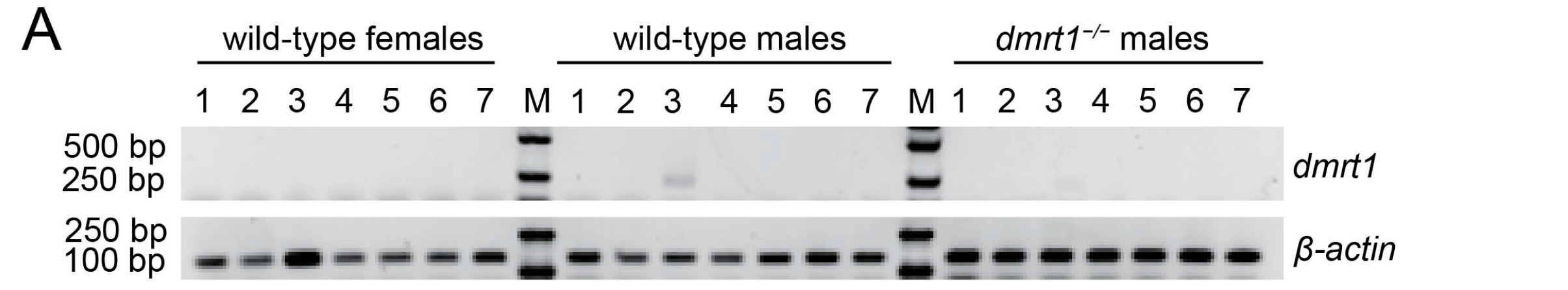

2.3. The Evaluation of dmrt1 mRNA Expression Level in C. semilaevis Tissues

Seven tissues, including heart, liver, gonad, intestine, muscle, skin, and blood were collected from females and males, as well as

dmrt1−/− ZZ males of 12 mph. Total RNA was extracted from collected samples by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Genomic DNA removal and first strand cDNA was synthesized by using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). As for RT-PCR analysis, a pair of gene specific primers (

dmrt1-RTF: 5′-CCGGACGGCTTCGTGTC-3′ and

dmrt1-RTR: 5′-CTTCCACAGGGAGCAGGCAGT-3′) were designed to span the TALEN-targeted region [

12]. Because the primers annealed within the knockout site, their binding was disrupted when the target sequence was deleted. As a result, these primers should fail to produce an amplification product in

dmrt1−/− ZZ males.

β-actin was enrolled as the internal control (amplified by

β-

actin-RTF: GCTGTGCTGTCCCTGTA and

β-

actin-RTR: GAGTAGCCACGCTCTGTC). The RT-PCR program was set as follows: 94 °C for 5 min, 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s and 30 cycles, and 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were analyzed with agarose gel electrophoresis.

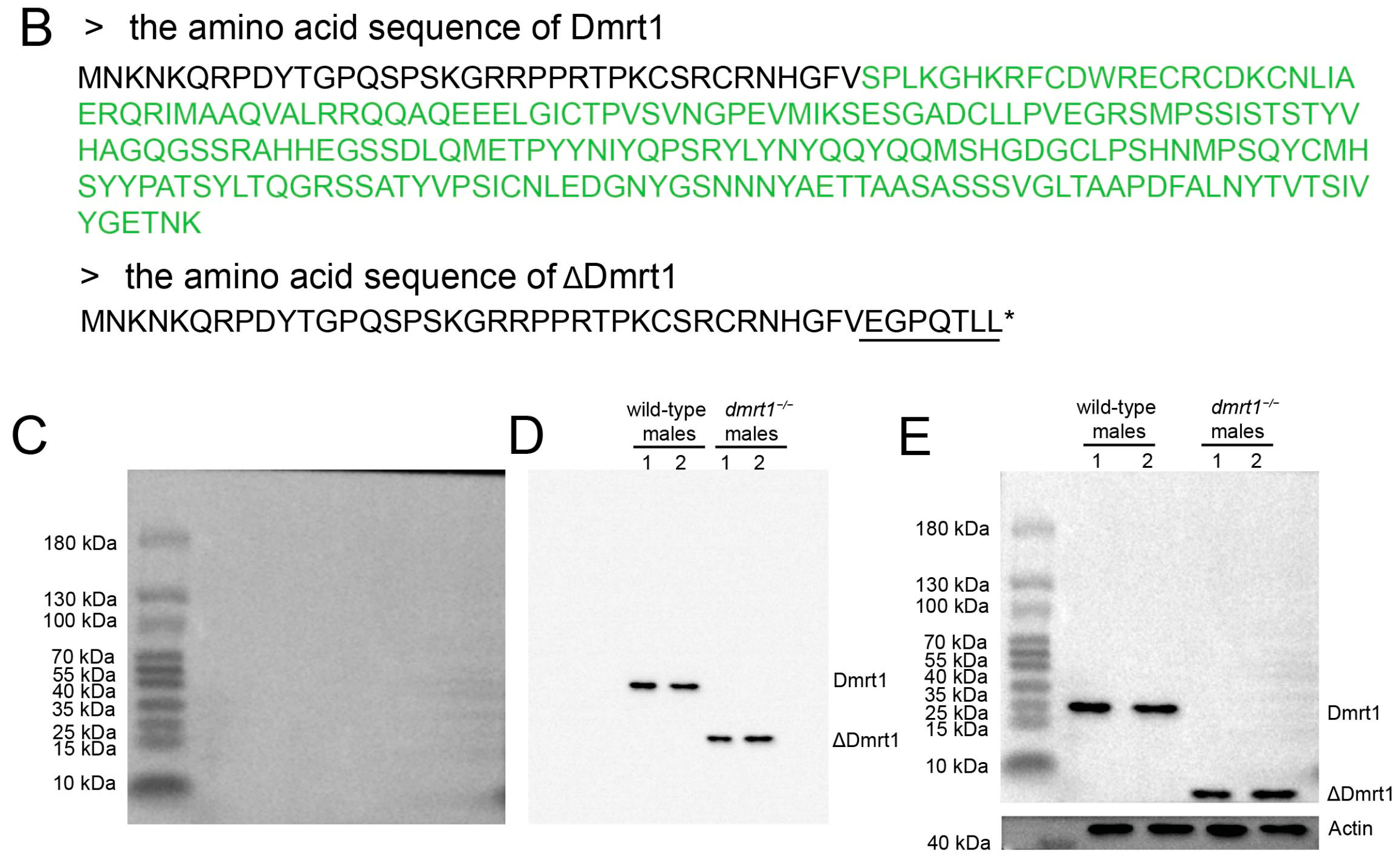

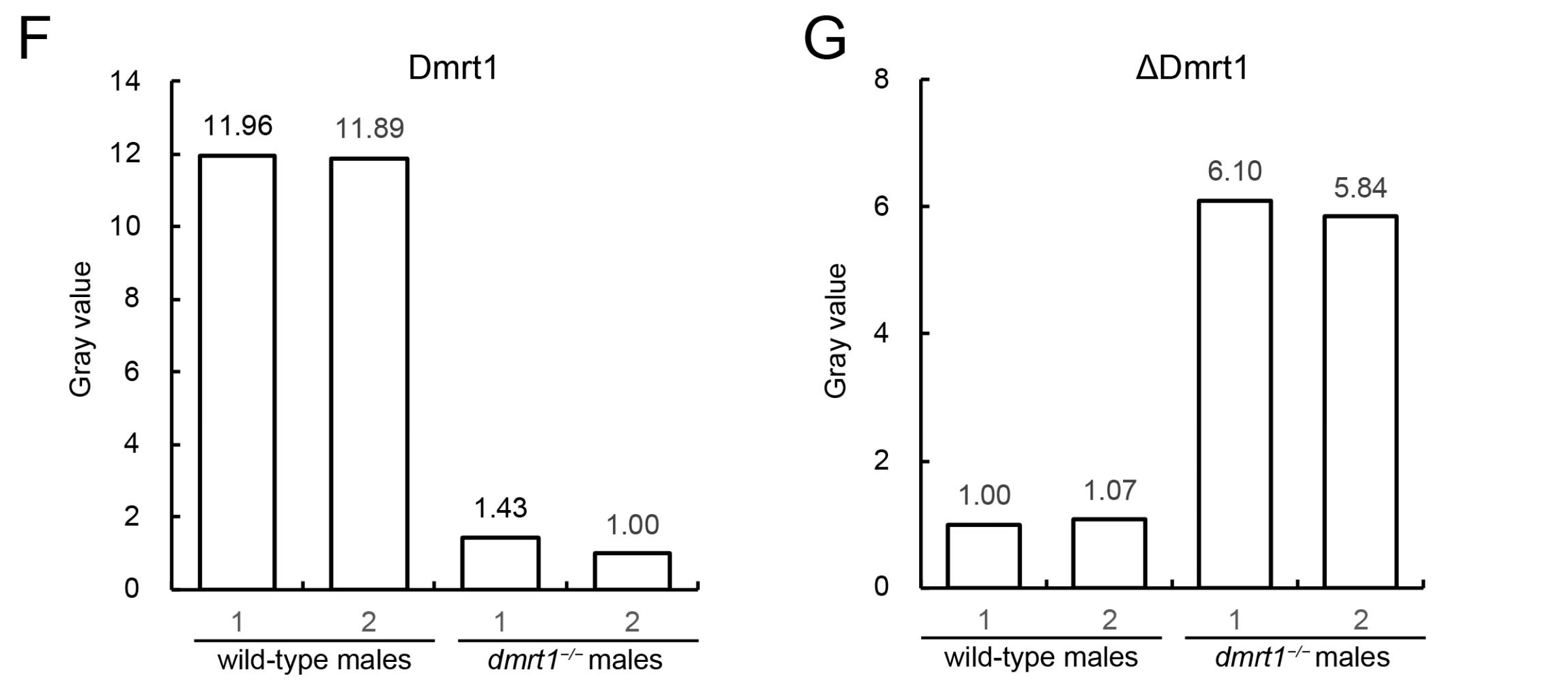

2.4. Western Blot

The coding sequence of Dmrt1, corresponding to the protein region highlighted in green in

Figure 2B, was synthesized by General Biol Company (Chuzhou, China) and cloned into the pET-32a expression vector. The recombinant His-tagged Dmrt1 protein was expressed in

Escherichia coli and purified using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. To enhance immunogenicity, a triple repeat of the truncated Dmrt1 peptide sequence (ΔDmrt1 in

Figure 2B) was designed and a His tag was added to the N-terminus for purification and detection. The recombinant peptide was chemically synthesized by General Biol Company (China). The purified His-tagged Dmrt1 proteins (purity ≥ 85%) and the synthesized ΔDmrt1 peptide were used as antigens for rabbit immunization, respectively. After four rounds of immunization, the antibody titer was confirmed to be no less than 1:10,000, and antibodies were purified via exsanguination.

Proteins were extracted from the frozen gonad tissues by using RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA and, respectively, incubated with homemade Dmrt1 antibody and ΔDmrt1 antibody at 4 °C overnight (1:1000 dilution). Then, it was rinsed with PBST and incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:5000 dilution). Positive signal was developed by using ECL chemiluminescence kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

2.5. Histological Analysis

Tissues including gonads, liver, spleen, heart, kidney, and muscle were carefully dissected from wild-type males and females, and dmrt1−/− ZZ males of 18 mph. The tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), dehydrated in serial dilutions of ethanol, embedded in paraffin wax, and cut into 7 µm-thick sections. The sectioned slides were then stained by using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

2.6. Flesh Quality Evaluation

Muscle tissues were carefully dissected from the bones of multiple individuals within each group (labeled as 12 mph). As the muscle mass from a single fish was insufficient for the minimum analytical requirement, we pooled tissues from two fish to form one composite sample. Each experimental group consisted of three such replicate samples. Samples were stored at −80 °C and shipped on dry ice to SGS-CSTC Standards Technical Service (Qingdao) CO., Ltd (Qingdao, China). Nutritional components including moisture, ash, crude protein and crude fat, amino acid components, and fatty acid components were measured in accordance with Chinese national standards.

Ten fish from wild-type females and dmrt1−/− ZZ males of tongue sole were used for the evaluation of flesh quality. The entire fish filet was excised from the backbone and shipped on dry ice to Standards Testing Group Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China). From each fillet, six muscle blocks (three from each side of the lateral line) were collected. These blocks were then randomly divided into two groups: three for TPA (Texture Profile Analysis) testing and three for shear force measurement. A section of muscle (2 cm3) from each specimen was excised and placed on the platform of a TMS-Pro texture meter (Food Technology Corporation, Sterling, VA, USA). A cylindrical metal probe with a diameter of 36 mm was used for the TPA test. Each sample underwent 2 cycles of compression analysis with a compression level of 60%, with a 30 mm/min test speed and 0.05 N trigger stress. For the shear force measurement, a precision cutting blade was employed. The test commenced (trigger force: 0.05 N) once the probe contacted the sample, shearing downward at 30 mm/min until complete severance.

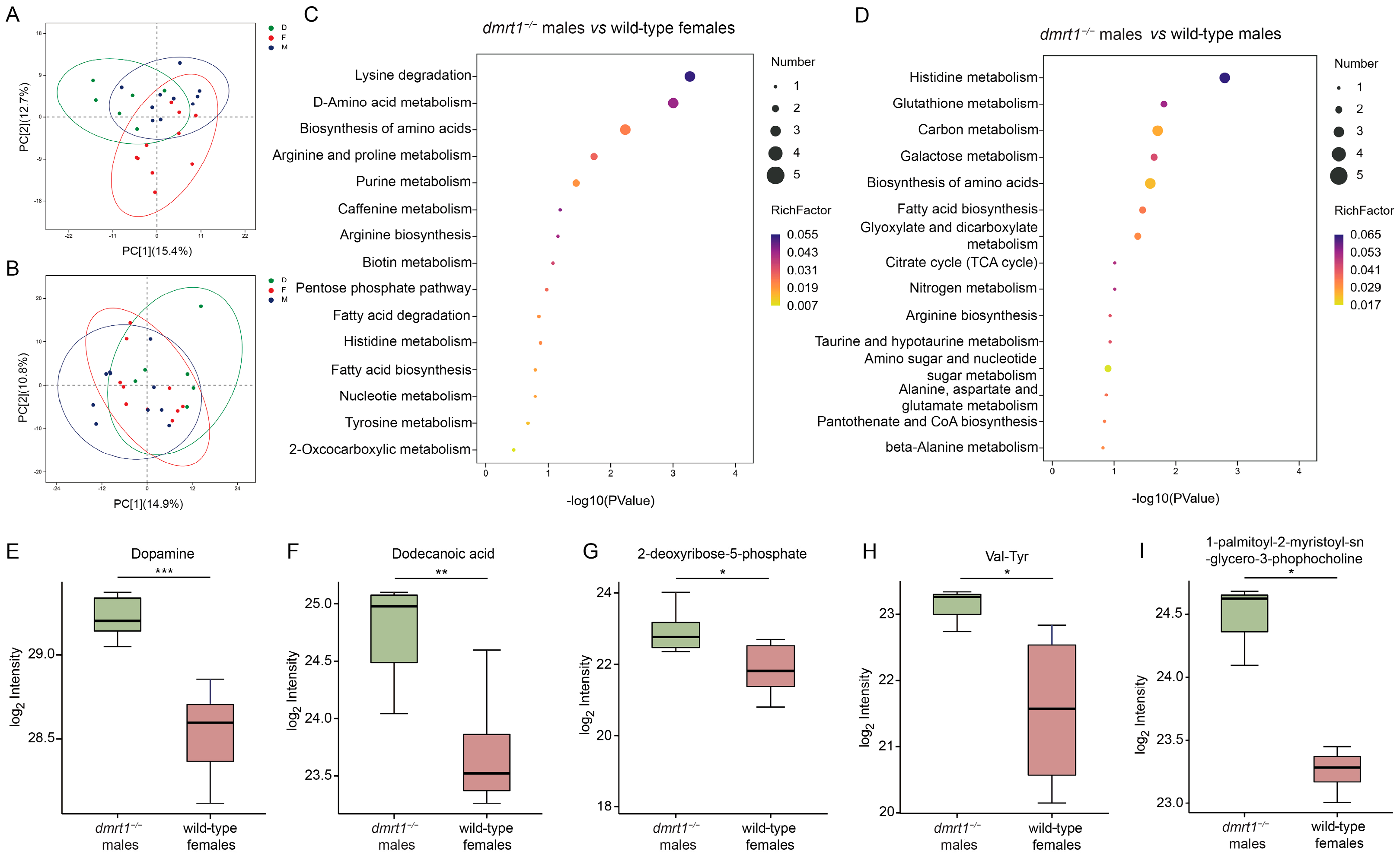

2.7. Metabolomics Analysis

Muscle tissues were dissected from 10 individuals of wild-type males, 10 of wild-type females, and 6 of dmrt1−/− ZZ males, then flash-frozen and homogenized in liquid nitrogen. The powder was thoroughly resuspended in chilled ethanol–acetonitrile–water (2:2:1, v/v), and then set aside at −20 °C for 10 min. After centrifugation at 14,000× g for 20 min, the supernatant was vacuum dried and reconstituted in acetonitrile–water solvent (1:1, v/v). The solution was centrifuged at 14,000× g for 15 min and the resulting supernatant was analyzed using a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) coupled to an Orbitrap Exploris™ 480 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) in Shanghai Applied Protein Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Separation was performed on a 2.1 mm × 100 mm ACQUIY UPLC BEH Amide 1.7 μm column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of 25 mM ammonium acetate and 25 mM ammonium hydroxide in water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). The gradient elution program was as follows: 95% B held for 0.5 min, linearly decreased to 65% over 6.5 min, further decreased to 40% B over 1 min and held for 1 min, then increased to 95% B in 0.1 min, followed by a 2.9 min re-equilibration period.

After raw data conversion with ProteoWizard MSConvert, peak identification, integration, peak alignment, and normalization were performed using XCMS software (version 3.2). The processed data were then analyzed using the R package (ropls: 1.18.8) for Pareto-scaled principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). A 200-permutation test was performed by repeatedly constructing OPLS-DA models using the metabolite data with permuted labels, and the Q2_permuted value was recorded for each permutation. A 7-fold cross-validation procedure was applied. The OPLS-DA models were validated based on interpretation of variation in Y (R2Y) and the model’s predictive capacity (Q2) in cross-validation. Student’s t-test was utilized to identify significant differences in metabolite levels between two groups. Metabolites with a variable importance in the projection (VIP) > 1 and p-value < 0.05 were regarded as differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs). It is noted that the p-values were not adjusted for multiple testing (e.g., by false discovery rate) in this exploratory analysis; therefore, the results should be interpreted as generating hypotheses for future validation. Metabolic pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained was analyzed using Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS) software (Version 20.0, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Mann–Whitney test was used to test flesh texture between wild-type females and dmrt1−/− ZZ males, followed by Holm–Bonferroni correction. Meanwhile, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) along with Tukey’s post hoc tests was employed for comparisons involving more than two sets of data, such as growth indicators and flesh nutritional analysis. Levene’s test was performed for homogeneity of variances and calculation of partial eta squared (η2) was calculated as the effect size. All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Values were considered as significant at p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Dmrt1 is a conserved transcriptional regulator essential for male sexual differentiation and testicular development across species ranging from mammals to teleost. Loss of DMRT1 has been shown to disrupt germ cell development and spermatogenesis [

16,

17]. In zebrafish,

dmrt1 mutants exhibited abnormal testis development and a female-biased sex ratio [

18]. Similarly, overexpression of

dmrt1 induced female-to-male sex reversal in Chinese medaka [

19]. In tilapia,

dmrt1−/− mutants developed gonads to ovaries that could not be reversed to testicular morphology even with aromatase inhibitor treatment, indicating its essential role in male maintenance and spermatogenesis [

7]. Correspondingly,

dmrt1+/− mutants in Chinese tongue sole (F0 generation) displayed aberrant testes lacking spermatocytes or spermatids [

13]. In this study, we generated

dmrt1−/− ZZ males (F4 generation) carrying a stable 8 bp deletion in the first exon of

dmrt1 gene. The gonads of these

dmrt1-deficient mutants developed ovarian lamella-like and ovarian cavity-like structures, resembling the gonadal phenotypes observed in

dmrt1 mutants of zebrafish and tilapia. We then cut the deficient gonads into pieces, and performed the artificial reproduction. However, almost no eggs were fertilized by 10 hpf, and all eggs had died and sunk by 24 hpf. Given the malformed morphology and the absence of successful fertilization, we concluded that

dmrt1 deficiency disrupted spermatogenesis, leading to infertility in

dmrt1−/− ZZ males. Notably, aside from testicular defects,

dmrt1 mutation did not cause any pathological changes in other parenchymal organs, including heart, liver, spleen, and kidney. Together with its predominant expression in testis, these results demonstrated that

dmrt1 is a highly specific and critical regulatory gene in the male reproductive system of Chinese tongue sole.

Since

dmrt1 is a key male determining gene, most existing studies have predominantly focused on the gonadal phenotypes and spermatogenesis in

dmrt1 mutants. Chinese tongue sole exhibits pronounced female-biased dimorphism, with adult females growing significantly faster than males and eventually gaining a much larger body size [

13]. This raised the question of whether

dmrt1 knockout would alter the growth traits of mutant males—an intriguing issue that had captured our research interest. Compared with wild-type males,

dmrt1−/− ZZ males first exhibited a significant growth advantage in body weight and body length at 12 mph. This coincides with the initial manifestation of growth dimorphism between wild-type females and males. This advantage not only persisted but was further expanded by 15 mph, when

dmrt1−/− ZZ males reached a body size comparable to that of wild-type females, with no significant differences in weight or length. The influence of sex-determining gene mutations on body size has been documented in Drosophila. Loss of the transformer (

tra) gene reduced body size in female larvae, suggesting the potential regulation of body size through the sex determination pathway [

20]. Therefore, the enhanced growth performance in

dmrt1-deficient male Chinese tongue sole positioned it as a promising model for future exploration on molecular mechanism beneath sexual size dimorphism in teleosts.

The nutritional components in fish meat, such as moisture, fat, amino acids, and fatty acids, serve as important indicators for assessing fish quality. In our study, most of these components in

dmrt1−/− ZZ males showed no significant differences compared to wild-type males and females. Moreover, the obtained data was close to those in the previous studies [

21]. These findings indicated that knockout of

dmrt1 would not markedly alter the muscle nutritional composition in Chinese tongue sole. Similar analysis in

bmp6-mutant crucian carp (

Carassius auratus) and

runx2b-mutant blunt snout bream (

Megalobrama amblycephala) also revealed no significant differences in flesh quality between mutant and wild-type strains [

22,

23].

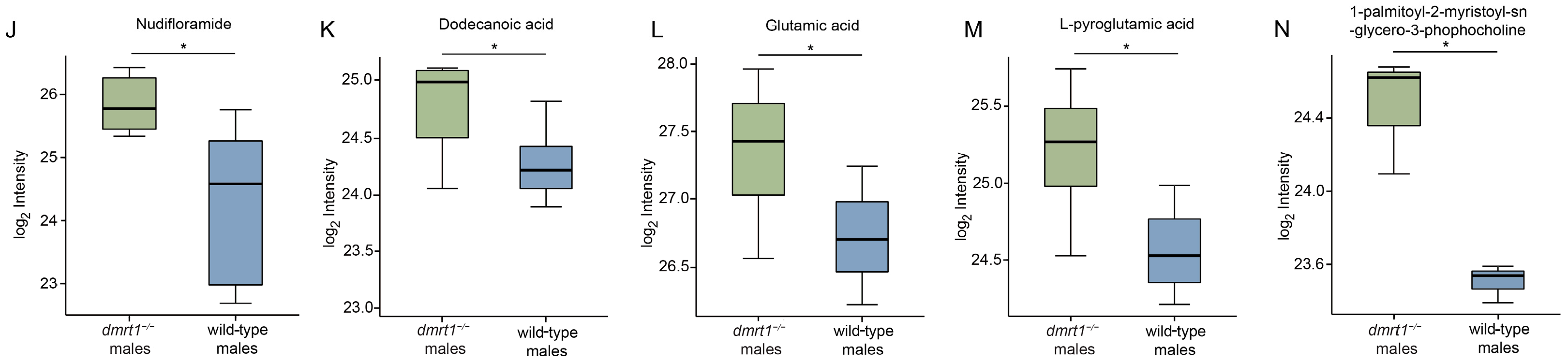

To further investigate the impact of

dmrt1 knockout on metabolic profiles, we performed non-targeted metabolomics analysis on

dmrt1 mutants and wild-type Chinese tongue soles. The results indicated several enriched pathways and differential metabolites in the muscle tissues of

dmrt1 mutants, which were associated with energy and growth processes, anti-oxidation, and neurotransmission. Both lysine degradation and carbon/galactose metabolism generate acetyl-CoA, a key intermediate in energy metabolism [

24]. Adequate lysine supplementation in feed has been shown to promote growth in Chinese tongue sole [

25]. In addition, arginine and proline metabolism plays a crucial role in myoblast proliferation in human skeletal muscle cells [

26]. A shift in these pathways in

dmrt1−/− ZZ males might thus affect growth rate and muscle growth. While this association is preliminary due to the statistical approach employed, it highlights lysine degradation as a priority pathway for functional validation in the context of

dmrt1 deficiency. Additionally, metabolites such as 2-deoxyribose-5-phosphate AMP and 1-palmitoyl-2-myristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine indicated changes in nucleotide/energy metabolism and membrane phospholipid remodeling [

27], which are essential for sustaining growth and muscular contraction. L-pyroglutamic acid is an intermediate of the γ-glutamyl cycle linked to glutathione turnover [

28]. Its elevation, together with enrichment of glutathione metabolism and histidine metabolism, might help regulate redox homeostasis and maintain muscle integrity under the anabolic and hormonal changes accompanying sex reversal. Beyond antioxidant capacity and energy supply, the up-regulated metabolites in

dmrt1−/− ZZ males suggested that sex reversal might involve enhanced neuromuscular signaling and other beneficial properties such as blood pressure reduction and anti-tumor activity. Dopamine, nudifloramide, and glutamic acid are all involved in neurotransmission [

29,

30,

31]; their elevated levels in muscle may reflect altered neuromuscular activity and motor control associated with the endocrine background in

dmrt1−/− ZZ males. Val-tyr and dodecanoic acid have been reported to help lower blood pressure and support cardiovascular health [

32,

33]. Moreover, dodecanoic acid exhibits potential anti-tumor effects against reproductive and liver cancer by inducing oxidative damage and inhibiting cancer cells growth [

33,

34]. However, the functions of these differentially abundant metabolites in the muscle of tongue sole, as well as their roles in mediating the metabolic alterations caused by

dmrt1 deletion, require further experimental validation.

This study is the first to assess the growth performance and fecundity of the F4 generation of dmrt1-edited tongue sole, and to compare the differences in muscle nutritional composition, texture structure, and metabolites between genome-edited fish and wild-type fish. Although sampling was randomized and samples were submitted to a third party for testing, a limitation of this study is that the data analysts were not blinded to the group allocation. On the other hand, during the comparative metabolomic analysis, limitations in sample availability led to relatively small and unbalanced sample sizes in certain groups. Consequently, the analysis of differential metabolites in this study is exploratory in nature and requires validation through larger sample sizes and targeted metabolite verification. We will continue to monitor the muscle nutritional composition and metabolite profiles of the F5 generation, while ensuring blinding to group allocation during data analysis. Furthermore, we plan to investigate the behavioral and immunological parameters of the gene-edited fish and conduct comparative analyses with their wild-type counterparts.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, by integrating growth, reproductive, histological, flesh quality, and non-targeted metabolomic analyses, we demonstrate that targeted disruption of dmrt1 generates a fast-growing but completely sterile all-male Chinese tongue sole strain whose body size and muscle quality closely resemble those of wild-type females. The F4 dmrt1−/− ZZ males showed feminized growth trajectories, ovarian-like gonadal structures, and a complete failure to produce functional sperm, while no major abnormalities were detected in other major organs. Their muscle proximate composition, amino acid, and fatty acid profiles, as well as most texture parameters, were comparable to those of wild-type females and generally fell within the ranges reported for conventional stocks, indicating that dmrt1 editing might not adversely affect the nutritional or sensory quality of the flesh. Metabolomic profiling further revealed differential enrichment of pathways related to energy provision, antioxidant defense, and neuromuscular function. Together, these results suggested dmrt1−/− ZZ males as a valuable fast-growing strain for the Chinese tongue sole aquaculture industry. Moreover, this model offers a useful entry point for dissecting the molecular basis of sexual size dimorphism and for systematically evaluating the effects of genome editing in fish across multiple levels—including physiological, genetic, protein, cellular, and metabolic dimensions.