Comparative Functional Analysis Reveals Conserved Roles of Aquaporins Under Osmotic Dehydration in Steinernema carpocapsae Strains

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nematodes

2.2. Osmotic Treatment

2.3. Gene Cloning

2.4. Bioinformatic and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.5. Xenopus Oocyte Transport Studies

2.6. Gene Expression Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. AQP Genes in Different S. carpocapsae Strains

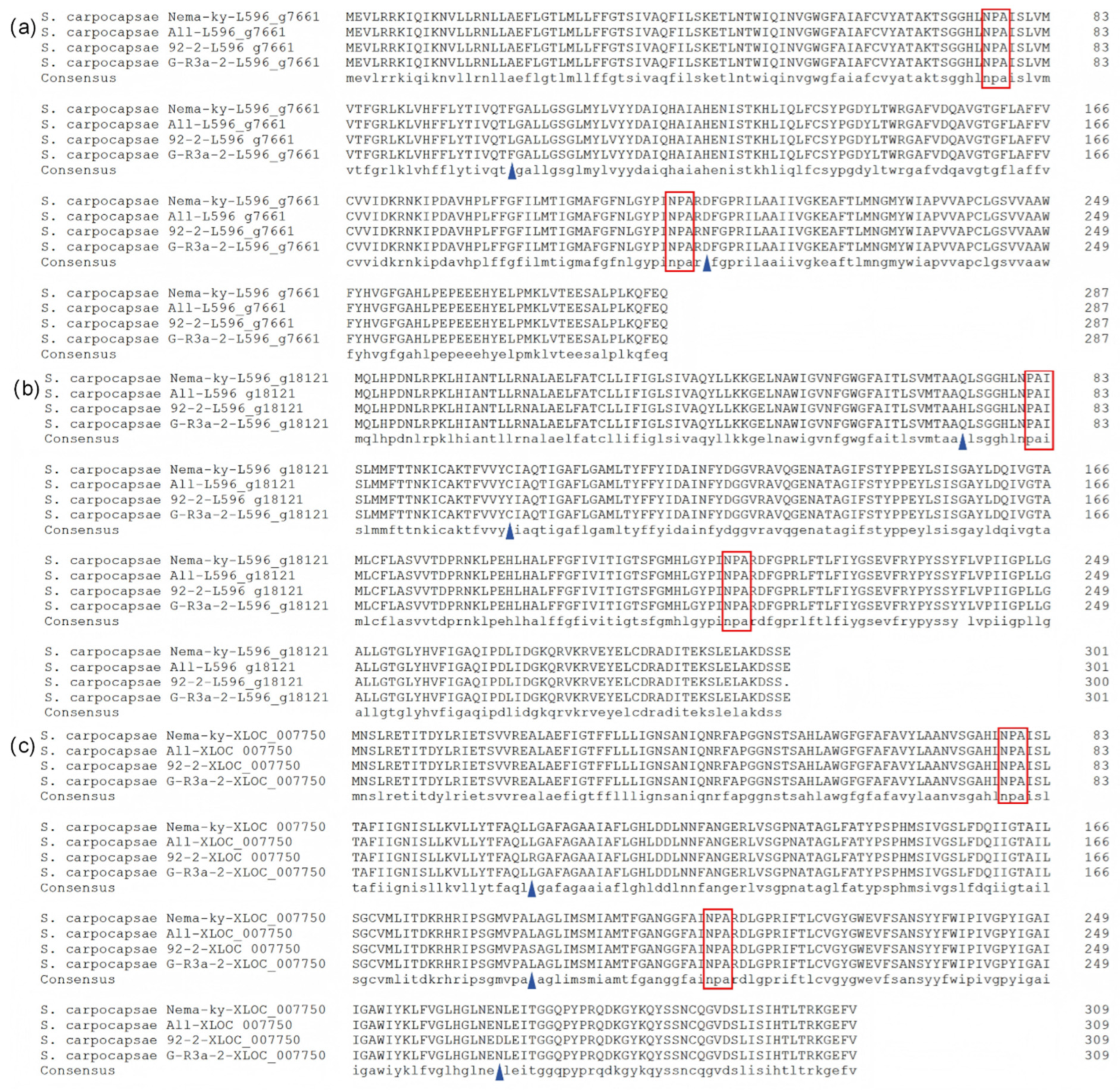

3.2. Amino Acid Sequences of Aquaporins

3.3. Physicochemical Properties of Aquaporins

3.4. Transmembrane and Conserved Domains of AQPs

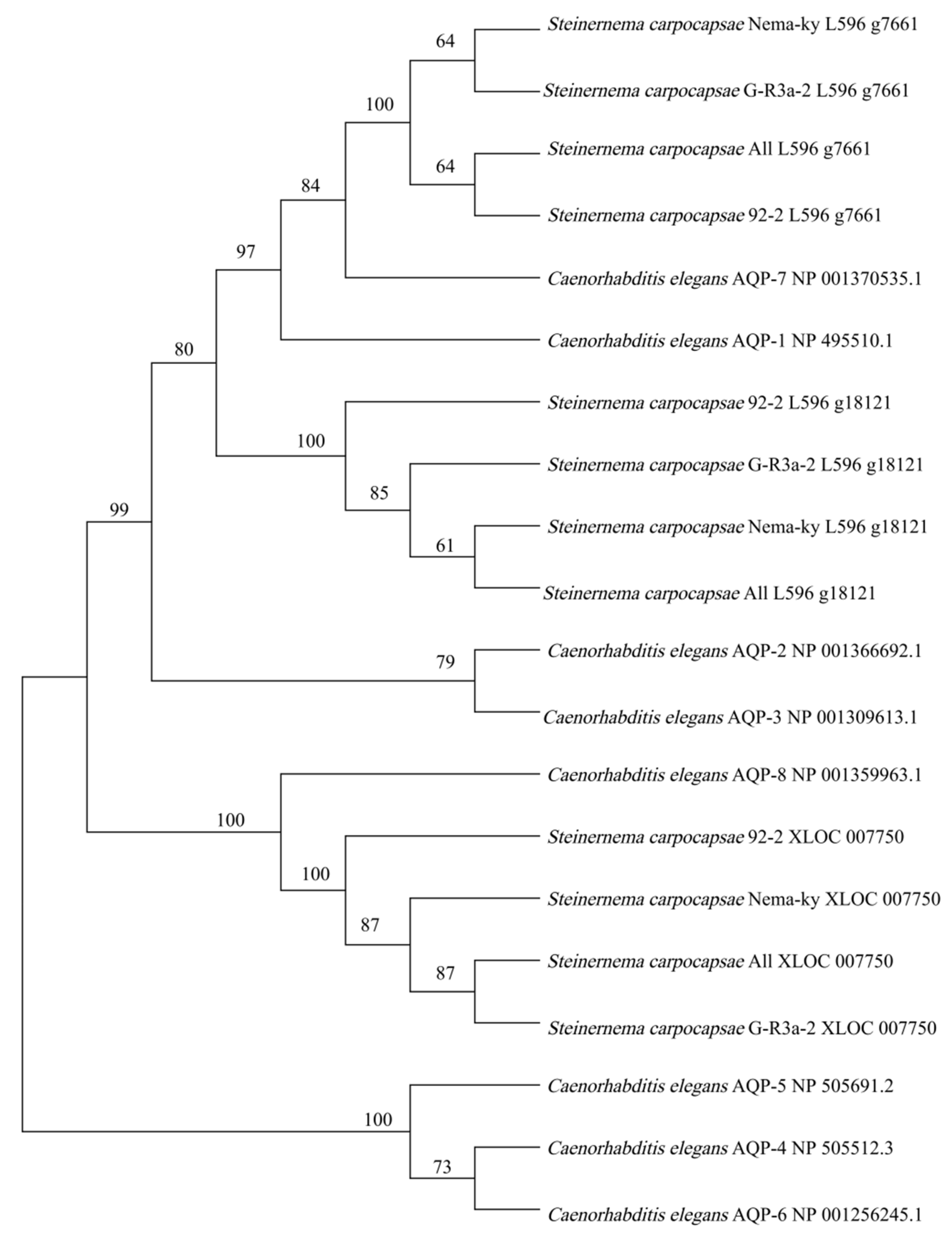

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis of AQPs in S. carpocapsae

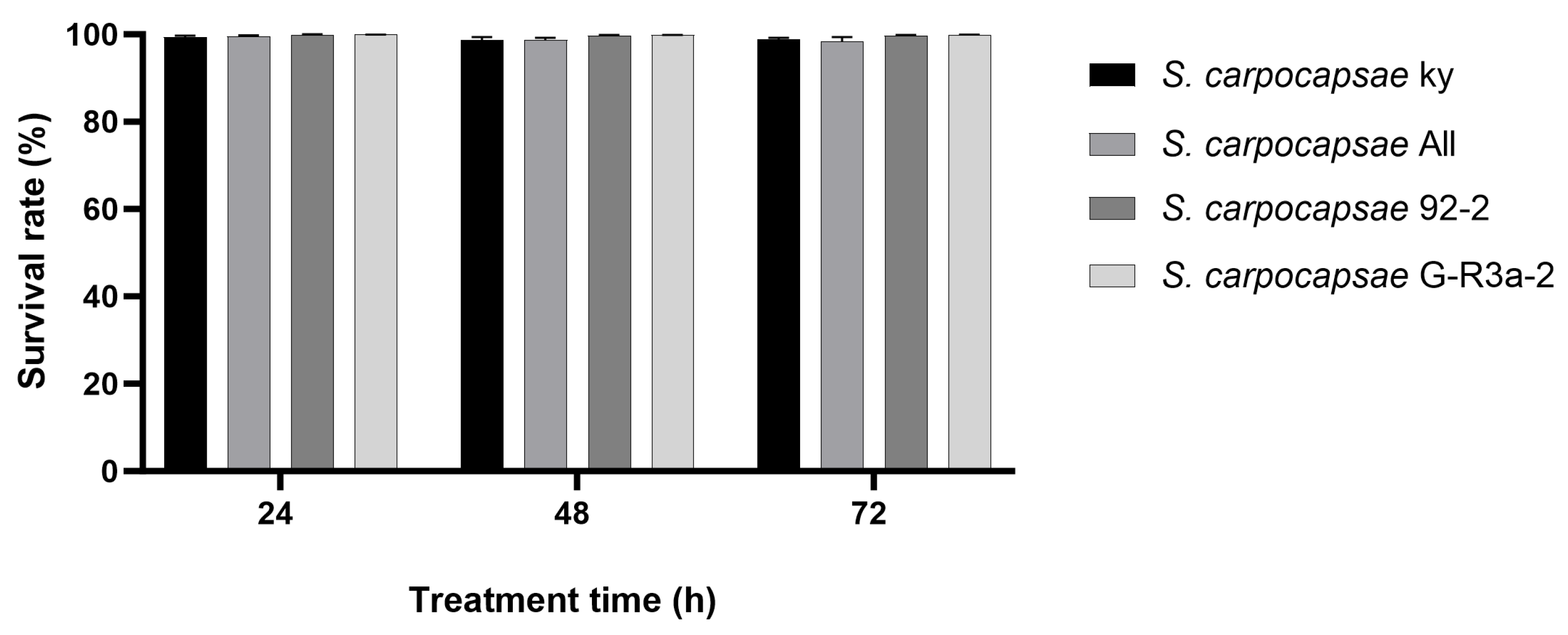

3.6. Survival of Different S. carpocapsae Strains Under Osmotic Dehydration

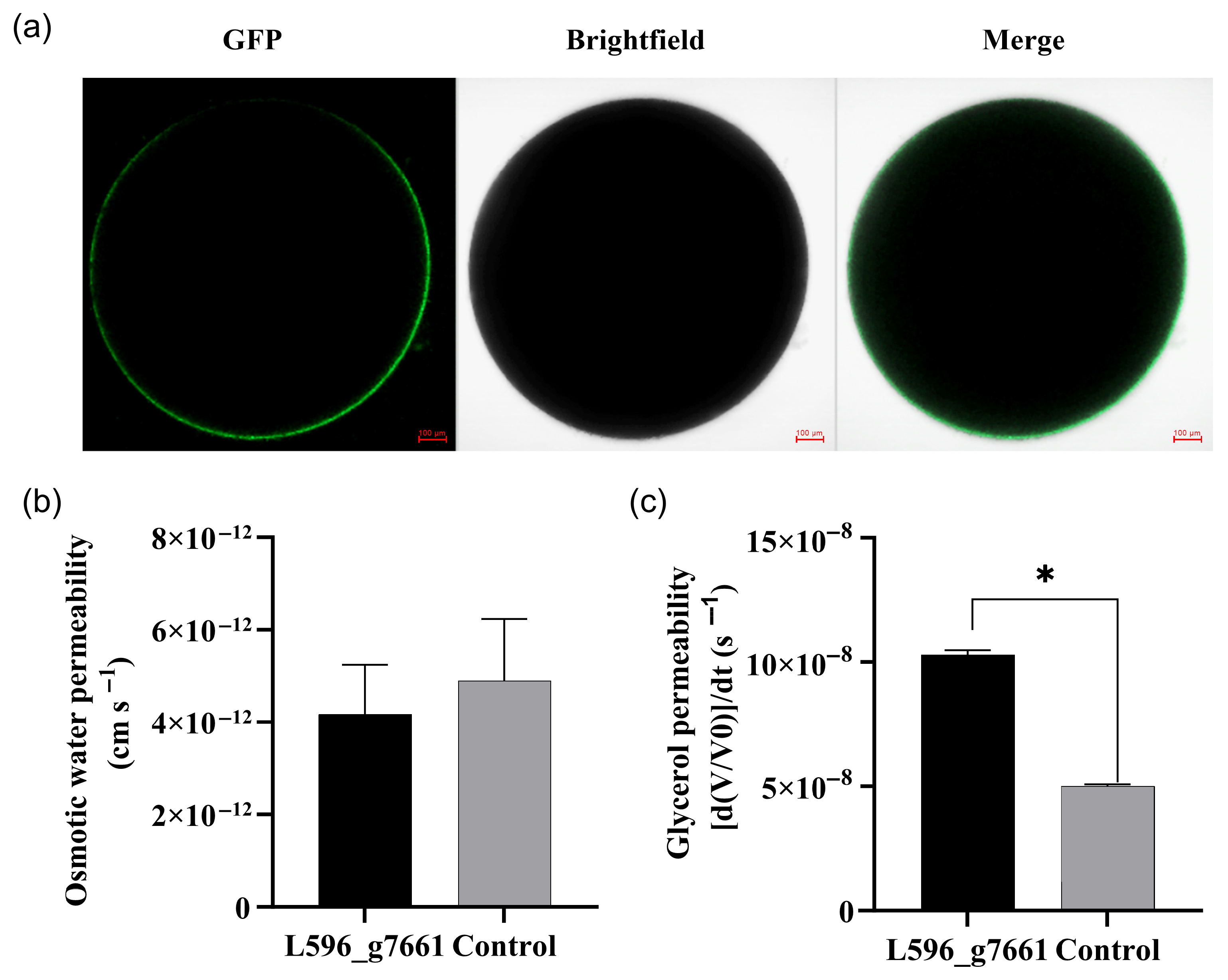

3.7. Glycerol Permeability of AQP L596_g7661

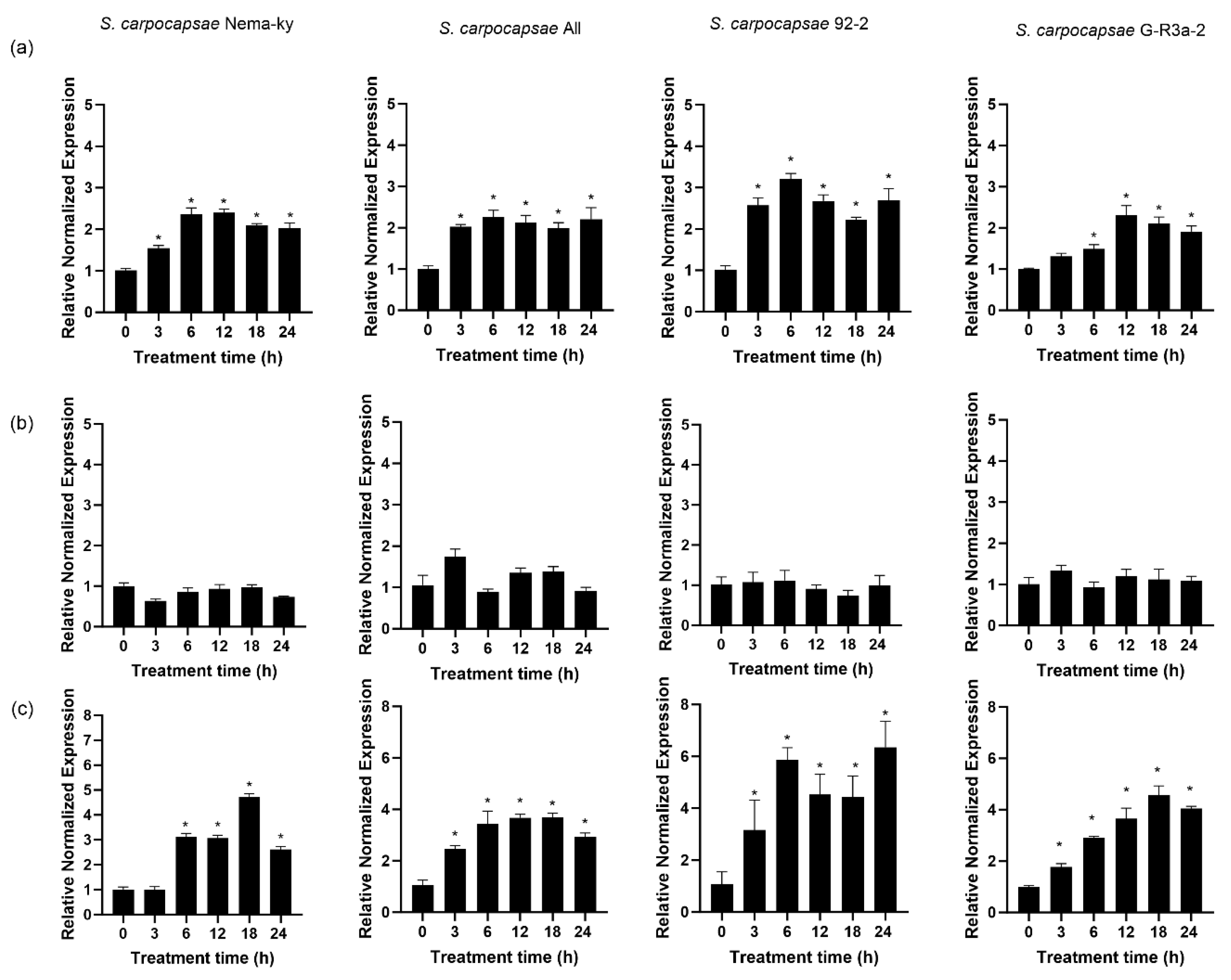

3.8. Response of AQPs to Osmotic Dehydration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Georgis, R.; Koppenhöfer, A.M.; Lacey, L.A.; Bélair, G.; Duncan, L.W.; Grewal, P.S.; Samish, M.; Tan, L.; Torr, P.; van Tol, R.W.M.H. Successes and failures in the use of parasitic nematodes for pest control. Biol. Control 2006, 38, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaude, S.; Griffin, C.T. Transmission success of entomopathogenic nematodes used in pest control. Insects 2018, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dai, K.; Kong, X.X.; Cao, L.; Qu, L.; Jin, Y.L.; Li, Y.L.; Gu, X.H.; Li, J.Z.; Xu, C.T.; et al. Research progress and perspective on entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Environ. Entomol. 2021, 43, 811–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Wang, C.; Li, C. Advances on the pathogenic mechanism of entomopathogenic nematodes. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2022, 38, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Ment, D.; Ramakrishnan, J.; Rodríguez Hernández, M.G.; Duncan, L.W. A century of advancement in entomopathogenic nematode formulation and application technology. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2025, 212, 108389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Wharton, D.A. Cold tolerance abilities of two entomopathogenic nematodes, Steinernema feltiae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. Cryobiology 2013, 66, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, X.; Han, R.; Chen, S.; De Clercq, P.; Moens, M. Osmotic induction of anhydrobiosis in entomopathogenic nematodes of the genera Heterorhabditis and Steinernema. Biol. Control 2010, 53, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; De Clercq, P.; Han, R.; Jones, J.; Chen, S.; Moens, M. Osmotic responses of different strains of Steinernema carpocapsae. Nematology 2011, 13, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gollop, N.; Glazer, I. Cross-stress tolerance and expression of stress-related proteins in osmotically desiccated entomopathogenic Steinernema feltiae IS-6. Parasitology 2005, 131, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Glazer, I.; Gollop, N.; Cash, P.; Argo, E.; Innes, A.; Stewart, E.; Davidson, I.; Wilson, M.J. Proteomic analysis of the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema feltiae IS-6 IJs under evaporative and osmotic stresses. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006, 145, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyson, T.; Reardon, W.; Browne, J.A.; Burnell, A.M. Gene induction by desiccation stress in the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae reveals parallels with drought tolerance mechanisms in plants. Int. J. Parasitol. 2007, 37, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somvanshi, V.S.; Koltai, H.; Glazer, I. Expression of different desiccation-tolerance related genes in various species of entomopathogenic nematodes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2008, 158, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.G.; Lamitina, T.; Agre, P.; Strange, K. Functional analysis of the aquaporin gene family in Caenorhabditis elegans. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007, 292, 1867–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ye, B. Advances in research on aquaporins in medical helminthes. Chin. J. Schistosomiasis Control 2020, 32, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill, R.M.; Hedfalk, K. Aquaporins–Expression, purification and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2021, 1863, 183650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Zeng, F.; Ye, S.; Ji, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Ouyang, Y. Evolutionary and structural analysis of the aquaporin gene family in rice. Plants 2025, 14, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, C.I.; Jarius, M.; von Kries, J.P.; Rohlfing, A.K. Neuronal chemosensation and osmotic stress response converge in the regulation of aqp-8 in C. elegans. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.Y.; Chen, Y.Q.; Ding, Q.; Yan, X. Analysis of aquaporin gene family in Steinernema carpocapsae. J. Environ. Entomol. 2025. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/44.1640.Q.20250509.1602.002 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Kaya, H.K.; Stock, S.P. Techniques in insect nematology. In Manual of Techniques in Insect Pathology; Lacey, L.A., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1997; pp. 281–324. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.P.; Han, R.C.; Qiu, X.H.; Cao, L.; Chen, J.H.; Wang, G.H. Storage of osmotically treated entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae. Insect Sci. 2006, 13, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Moens, M.; Han, R.; Chen, S.; De Clercq, P. Effects of selected insecticides on osmotically treated entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Plant Dis. Protect. 2012, 119, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic-Djuranovic, S.; Schultz, J.E.; Beitz, E. A single aquaporin gene encodes a water/glycerol/urea facilitator in Toxoplasma gondii with similarity to plant tonoplast intrinsic proteins 1. FEBS Lett. 2003, 555, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ballesta, M.C.; Carvajal, M. Mutual interactions between aquaporins and membrane components. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K. Aquaporin subfamily with unusual NPA boxes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1758, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchen, P.; Day, R.E.; Salman, M.M.; Conner, M.T.; Bill, R.M.; Conner, A.C. Beyond water homeostasis: Diverse functional roles of mammalian aquaporins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1850, 2410–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Lacey, M.J.; Bedding, R.A. Permeability of the infective juveniles of Steinernema carpocapsae to glycerol during osmotic dehydration and its effect on biochemical adaptation and energy metabolism. Comp. Biochem. Phys. B 2000, 125, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Bedding, R.A. Characteristics of protectant synthesis of infective juveniles of Steinernema carpocapsae and importance of glycerol as a protectant for survival of the nematodes during osmotic dehydration. Comp. Biochem. Phys. B 2002, 131, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbrey, J.M.; Gorelick-Feldman, D.A.; Kozono, D.; Praetorius, J.; Nielsen, S.; Agre, P. Aquaglyceroporin AQP9: Solute permeation and metabolic control of expression in liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2945–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkman, A.S. More than just water channels: Unexpected cellular roles of aquaporins. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 3225–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, C.P.; MacIver, B. Localization and expression of Aquaporin 1 (AQP1) in the tissues of the spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, P.; Wen, H.; Qi, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, K.; Fu, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Genome-wide characterization of Aquaporins (aqps) in Lateolabrax maculatus: Evolution and expression patterns during freshwater acclimation. Mar. Biotechnol. 2021, 23, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Gautam, D.; Vats, A.; Roshan, M.; Goyal, P.; Rana, C.; Payal, S.M.; Ludri, A.; De, S. Aquaporin (AQP) gene family in buffalo and goat: Molecular characterization and their expression analysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 136145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | Product Length (bp) | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sca7661-F1 | ATGGAAGTGCTCCGGCG | 864 | PCR |

| Sca7661-R1 | CTACTGTTCAAACTGCTTAAGAGGCAA | ||

| Sca18121-F2 | ATGCAGCTGCATCCCGACAAC | 906 | PCR |

| Sca18121-R2 | TCACTCGGAAGAATCTTTGGCGAG | ||

| Sca007750-F4 | ACGGGTTAAAGTGTGGATGG | 960 | PCR |

| Sca007750-R4 | ATGAATAGTCTCCGCGAGAC | ||

| 7661-HR-F | AGATCAATTCCCCGGGGATCCATGGAAGTGCTCCGGCGCAAG | 894 | PCR |

| 7661-HR-R | CACCATGGGTACCTGTTCAAACTGCTTAAGAG | ||

| 7GFP-HR-F | AACAGGTACCCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG | 751 | PCR |

| 7GFP-HR-R | CCAGATCAAGCTTGCTCTAGATTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG | ||

| Sca-actin2-F | TGTGACGAAGAAGTTGCCGC | 81 | RT-qPCR |

| Sca-actin2-R | AGCGTCATCTCCGGCAAAA | ||

| aqp7661-qf1 | TTACTACGACGCGATCCAGC | 89 | RT-qPCR |

| aqp7661-qr1 | AGTCTCCAGGGTAGGAGCAG | ||

| aqp18121-qf3 | GGGTCAATTTCGGATGGGGA | 149 | RT-qPCR |

| aqp18121-qr3 | AGCGATGCAGTAAACGACGA | ||

| aqp7750-qf2 | AACTCTACCTCAGCCCACCT | 110 | RT-qPCR |

| aqp7750-qr2 | AAGGCAGTAAGGGAGATGGC |

| Gene Name | Strain | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Instability Index | Isoelectric Point | Average Hydrophilicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L596_g7661 | Nema-ky | 32.08 | 27.41 | 7.12 | 0.575 |

| All | 32.05 | 26.98 | 7.12 | 0.578 | |

| 92-2 | 32.05 | 27.15 | 7.73 | 0.578 | |

| G-R3a-2 | 32.08 | 27.41 | 7.12 | 0.575 | |

| L596_g18121 | Nema-ky | 33.17 | 22.15 | 6.37 | 0.463 |

| All | 33.17 | 22.15 | 6.37 | 0.463 | |

| 92-2 | 33.11 | 21.67 | 6.70 | 0.465 | |

| G-R3a-2 | 33.18 | 22.56 | 6.37 | 0.450 | |

| XLOC_007750 | Nema-ky | 33.19 | 21.58 | 7.05 | 0.445 |

| All | 33.19 | 21.58 | 7.05 | 0.445 | |

| 92-2 | 33.21 | 22.55 | 7.05 | 0.403 | |

| G-R3a-2 | 33.19 | 21.58 | 7.05 | 0.445 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Huang, Q.; Yan, X. Comparative Functional Analysis Reveals Conserved Roles of Aquaporins Under Osmotic Dehydration in Steinernema carpocapsae Strains. Biology 2026, 15, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010078

Chen Y, Huang Q, Yan X. Comparative Functional Analysis Reveals Conserved Roles of Aquaporins Under Osmotic Dehydration in Steinernema carpocapsae Strains. Biology. 2026; 15(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yongqi, Qiuyue Huang, and Xun Yan. 2026. "Comparative Functional Analysis Reveals Conserved Roles of Aquaporins Under Osmotic Dehydration in Steinernema carpocapsae Strains" Biology 15, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010078

APA StyleChen, Y., Huang, Q., & Yan, X. (2026). Comparative Functional Analysis Reveals Conserved Roles of Aquaporins Under Osmotic Dehydration in Steinernema carpocapsae Strains. Biology, 15(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010078