Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of CYP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii P.A. Dang.

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalgal Strain and Culture Conditions

2.2. Identification of the CYP450 Gene Family Members in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

2.3. Sequence Analysis of the crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of CYP450 Sequences in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

2.5. Chromosomal Localization and Gene Duplication of the crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

2.6. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in the Promoter Regions of crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

2.7. Functional Analysis of the crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

2.8. RNA Sequencing Data Analysis

2.9. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of crP450 Gene Expression

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of CYP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

3.2. Phylogenetic and Sequence Analyses of crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

3.3. Chromosomal Distribution of crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

3.4. Distribution of Cis-Acting Elements in the Promoter Regions of crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

3.5. Functional Annotation of crP450 Proteins in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

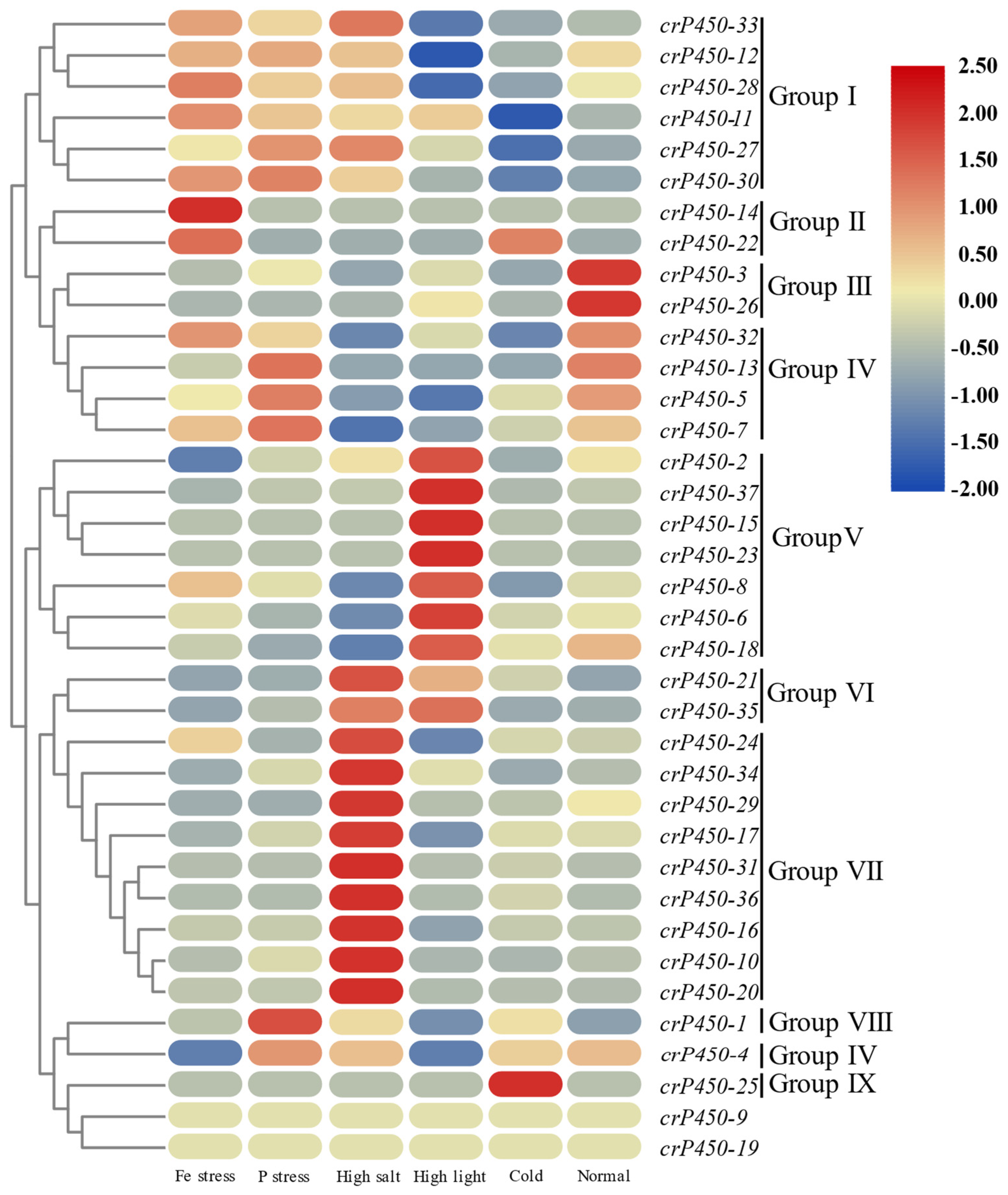

3.6. Expression of crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Under Different Environmental Conditions

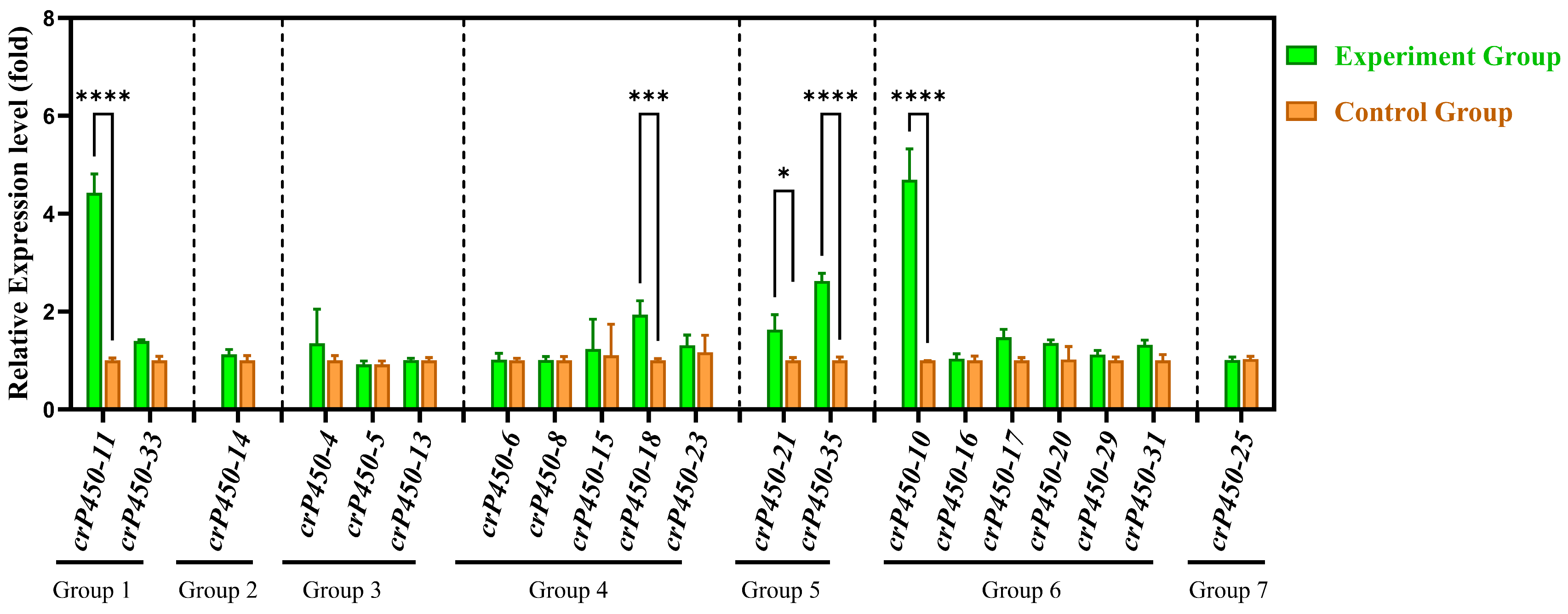

3.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of crP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelson, D.R. The Cytochrome P450 Homepage. Hum. Genom. 2009, 4, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossam Abdelmonem, B.; Abdelaal, N.M.; Anwer, E.K.E.; Rashwan, A.A.; Hussein, M.A.; Ahmed, Y.F.; Khashana, R.; Hanna, M.M.; Abdelnaser, A. Decoding the Role of CYP450 Enzymes in Metabolism and Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, F.O.; Pandhal, J.; Wright, P.C. Exploiting Cyanobacterial P450 Pathways. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010, 13, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannemann, F.; Bichet, A.; Ewen, K.M.; Bernhardt, R. Cytochrome P450 Systems—Biological Variations of Electron Transport Chains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2007, 1770, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Du, L.; Bernhardt, R. Redox Partners: Function Modulators of Bacterial P450 Enzymes. Trends Microbiol. 2020, 28, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Su, P.; Huang, L.; Gao, W. Cytochrome P450s in Plant Terpenoid Biosynthesis: Discovery, Characterization and Metabolic Engineering. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2023, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinot, F. Cytochrome P450 Metabolizing Fatty Acids in Living Organisms. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Wu, J.; Li, B.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, P.; Li, J. Transcriptomic Analysis of Saffron at Different Flowering Stages Using RNA Sequencing Uncovers Cytochrome P450 Genes Involved in Crocin Biosynthesis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 3451–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaoka, N.; Matsubara, T.; Sato, M.; Takahashi, K.; Wakuta, S.; Kawaide, H.; Matsui, H.; Nabeta, K.; Matsuura, H. Arabidopsis CYP94B3 Encodes Jasmonyl-l-Isoleucine 12-Hydroxylase, a Key Enzyme in the Oxidative Catabolism of Jasmonate. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskulska, A.; Mankiewicz-Boczek, J. Cyanophages Specific to Cyanobacteria from the Genus Microcystis. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2020, 20, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M.; Blasco, G.; Brzezinski, M.A.; Melack, J.M.; Reed, D.C.; Miller, R.J. Factors Influencing Urea Use by Giant Kelp (Macrocystis Pyrifera, Phaeophyceae). Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, M.; Lin, X.; Liu, X.; Huang, H.; Ge, F. Malonylome Analysis Reveals the Involvement of Lysine Malonylation in Metabolism and Photosynthesis in Cyanobacteria. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 2030–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kselíková, V.; Singh, A.; Bialevich, V.; Čížková, M.; Bišová, K. Improving Microalgae for Biotechnology—From Genetics to Synthetic Biology–Moving Forward but Not There Yet. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 58, 107885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liyanaarachchi, V.C.; Premaratne, M.; Ariyadasa, T.U.; Nimarshana, P.H.V.; Malik, A. Two-Stage Cultivation of Microalgae for Production of High-Value Compounds and Biofuels: A Review. Algal Res. 2021, 57, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Pazouki, L.; Nguyen, H.; Jacobshagen, S.; Bigge, B.M.; Xia, M.; Mattoon, E.M.; Klebanovych, A.; Sorkin, M.; Nusinow, D.A.; et al. Comparative Phenotyping of Two Commonly Used Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Background Strains: CC-1690 (21gr) and CC-5325 (The CLiP Mutant Library Background). Plants 2022, 11, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido-Pedraza, C.M.; Torres, M.J.; Llamas, A. The Microalgae Chlamydomonas for Bioremediation and Bioproduct Production. Cells 2024, 13, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghribi, M.; Nouemssi, S.B.; Meddeb-Mouelhi, F.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Genome Editing by CRISPR-Cas: A Game Change in the Genetic Manipulation of Chlamydomonas. Life 2020, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Shekh, A.; Jakhu, S.; Sharma, Y.; Kapoor, R.; Sharma, T.R. Bioengineering of Microalgae: Recent Advances, Perspectives, and Regulatory Challenges for Industrial Application. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido-Pedraza, C.M.; Calatrava, V.; Llamas, A.; Fernandez, E.; Sanz-Luque, E.; Galvan, A. Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Nitrite Are Highly Dependent on Nitrate Reductase in the Microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatrava, V.; Tejada-Jimenez, M.; Sanz-Luque, E.; Fernandez, E.; Galvan, A.; Llamas, A. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a Reference Organism to Study Algal–Microbial Interactions: Why Can’t They Be Friends? Plants 2023, 12, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, S.; Lingappa, U.F.; Mayali, X.; Sindermann, E.S.; Chastain, J.L.; Weber, P.K.; Stuart, R.; Merchant, S.S. Scarcity of Fixed Carbon Transfer in a Model Microbial Phototroph–Heterotroph Interaction. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallaher, S.D.; Fitz-Gibbon, S.T.; Strenkert, D.; Purvine, S.O.; Pellegrini, M.; Merchant, S.S. High-throughput Sequencing of the Chloroplast and Mitochondrion of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to Generate Improved de Novo Assemblies, Analyze Expression Patterns and Transcript Speciation, and Evaluate Diversity among Laboratory Strains and Wild Isolates. Plant J. 2018, 93, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.-P.; Wang, M.; Wang, C. Nuclear Transformation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: A Review. Biochimie 2021, 181, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Catalanotti, C.; D’Adamo, S.; Wittkopp, T.M.; Ingram-Smith, C.J.; Mackinder, L.; Miller, T.E.; Heuberger, A.L.; Peers, G.; Smith, K.S.; et al. Alternative Acetate Production Pathways in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii during Dark Anoxia and the Dominant Role of Chloroplasts in Fermentative Acetate Production. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4499–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, W.; Abdul-Kadir, R.; Lee, L.M.; Koh, B.; Lee, Y.S.; Chan, H.Y. A Simple and Inexpensive Physical Lysis Method for DNA and RNA Extraction from Freshwater Microalgae. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaraz-Delgado, A.L.; Flores-Uribe, J.; Pérez-España, V.H.; Salgado-Manjarrez, E.; Badillo-Corona, J.A. Production of Therapeutic Proteins in the Chloroplast of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. AMB Expr. 2014, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grahl, I.; Reumann, S. Stramenopile Microalgae as “Green Biofactories” for Recombinant Protein Production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siaut, M.; Cuiné, S.; Cagnon, C.; Fessler, B.; Nguyen, M.; Carrier, P.; Beyly, A.; Beisson, F.; Triantaphylidès, C.; Li-Beisson, Y.; et al. Oil Accumulation in the Model Green Alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Characterization, Variability between Common Laboratory Strains and Relationship with Starch Reserves. BMC Biotechnol. 2011, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.T.; Ullrich, N.; Joo, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Goodenough, U. Algal Lipid Bodies: Stress Induction, Purification, and Biochemical Characterization in Wild-Type and Starchless Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 1856–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Q. Enhanced Lipid Production in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by Co-Culturing With Azotobacter Chroococcum. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.J.; Eddy, S.R. Nhmmer: DNA Homology Search with Profile HMMs. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2487–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, K.; Jo, A.; Chang, Y.K.; Han, J.-I. Lipid Induction of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CC-124 Using Bicarbonate Ion. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.C.; Nelson, D.R.; Møller, B.L.; Werck-Reichhart, D. Plant Cytochrome P450 Plasticity and Evolution. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1244–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gebali, S.; Mistry, J.; Bateman, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Luciani, A.; Potter, S.C.; Qureshi, M.; Richardson, L.J.; Salazar, G.A.; Smart, A.; et al. The Pfam Protein Families Database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D427–D432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The Conserved Domain Database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Pachter, L.; Salzberg, S.L. TopHat: Discovering Splice Junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryzhny, S.N.; Zgoda, V.G.; Maynskova, M.A.; Novikova, S.E.; Ronzhina, N.L.; Vakhrushev, I.V.; Khryapova, E.V.; Lisitsa, A.V.; Tikhonova, O.V.; Ponomarenko, E.A.; et al. Combination of Virtual and Experimental 2DE Together with ESI LC-MS/MS Gives a Clearer View about Proteomes of Human Cells and Plasma. Electrophoresis 2016, 37, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.-J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein Localization Predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendtsen, J.D.; Nielsen, H.; Widdick, D.; Palmer, T.; Brunak, S. Prediction of Twin-Arginine Signal Peptides. BMC Bioinform. 2005, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An Upgraded Gene Feature Visualization Server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for Motif Discovery and Searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator: Figure 1. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A Tool for Automated Alignment Trimming in Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, D.; Jintong, R.; Yang, W.; Zuhong, F.; Tian, T.; Hong, Z. Genome-Wide Analysis of the CML Gene Family and Its Response to Cold Stress in Curcuma alismatifolia. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaneechoutte, D.; Vandepoele, K. Curse: Building Expression Atlases and Co-Expression Networks from Public RNA-Seq Data. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2880–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential Gene and Transcript Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, A.C.D.A.; Pretti, I.R.; Batitucci, M.D.O.C.P. Comparison of RNA extraction methods for Passiflora edulis sims leaves. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2016, 38, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; You, T.; Pang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, L.; Li, X.; Liu, Z. Structural Basis for an Early Stage of the Photosystem II Repair Cycle in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Guo, J.; Cheng, F.; Gao, Z.; Du, L.; Meng, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, X. Cytochrome P450s in Algae: Bioactive Natural Product Biosynthesis and Light-Driven Bioproduction. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 2832–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezawa, N.; Tanaka, M.; Nagayoshi, M.; Shinkyo, R.; Sakaki, T.; Inouye, K.; Sato, F. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of CYP719, a Methylenedioxy Bridge-Forming Enzyme That Belongs to a Novel P450 Family, from Cultured Coptis japonica Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 38557–38565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Singh, R.; Shirke, P.A.; Tripathi, R.D.; Trivedi, P.K.; Chakrabarty, D. Expression of Rice CYP450-Like Gene (Os08g01480) in Arabidopsis Modulates Regulatory Network Leading to Heavy Metal and Other Abiotic Stress Tolerance. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Tang, B.; Li, Z.; Shi, L.; Zhu, H. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analyses of CYP450 Genes in Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, L.; Fan, X.; Nelson, D.R.; Han, W.; Zhang, X.; Xu, D.; Renault, H.; Markov, G.V.; Ye, N. Diversity and Evolution of Cytochromes P450 in Stramenopiles. Planta 2019, 249, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, N.; Baudry, J.; Makris, T.M.; Schuler, M.A.; Sligar, S.G. A Retinoic Acid Binding Cytochrome P450: CYP120A1 from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 436, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, K.; Chen, H. Global Identification, Structural Analysis and Expression Characterization of Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase Superfamily in Rice. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Li, X. Genome-Wide Analysis of the P450 Gene Family in Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis) Reveals Functional Diversity in Abiotic Stress. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Hua, Y.; Zhou, T.; Yue, C.; Huang, J.; Feng, Y. Genomic Identification of CYP450 Enzymes and New Insights into Their Response to Diverse Abiotic Stresses in Brassica napus. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 43, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Yu, D.; Xie, X.; Qin, L.; Yang, Y.; Huang, B. Genome-Wide Study of Saprotrophy-Related Genes in the Basal Fungus Conidiobolus heterosporus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 6261–6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasekaran, T.; Karcher, D.; Nielsen, A.Z.; Martens, H.J.; Ruf, S.; Kroop, X.; Olsen, C.E.; Motawie, M.S.; Pribil, M.; Møller, B.L.; et al. Transfer of the Cytochrome P450-Dependent Dhurrin Pathway from Sorghum bicolor into Nicotiana tabacum Chloroplasts for Light-Driven Synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 2495–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustgi, S.; Springer, A.; Kang, C.; Von Wettstein, D.; Reinbothe, C.; Reinbothe, S.; Pollmann, S. Allene oxide synthase and hydroperoxide lyase, two non-canonical cytochrome p450s in Arabidopsis thaliana and their different roles in plant defense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, S.; Song, X.; Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Yuan, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Profiling of Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase Superfamily in Foxtail millet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yuan, J.; Qin, L.; Shi, W.; Xia, G.; Liu, S. TaCYP81D5, One Member in a Wheat Cytochrome P450 Gene Cluster, Confers Salinity Tolerance via Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandian, B.A.; Sathishraj, R.; Djanaguiraman, M.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Jugulam, M. Role of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Plant Stress Response. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, B.; Nayak, I.; Parameswaran, C.; Kesawat, M.S.; Sahoo, K.K.; Subudhi, H.N.; Balasubramaniasai, C.; Prabhukarthikeyan, S.R.; Katara, J.L.; Dash, S.K.; et al. A Comprehensive Genome-Wide Investigation of the Cytochrome 71 (OsCYP71) Gene Family: Revealing the Impact of Promoter and Gene Variants (Ser33Leu) of OsCYP71P6 on Yield-Related Traits in Indica Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plants 2023, 12, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackah, M.; Boateng, N.A.S.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Q. Genome Wide and Comprehensive Analysis of the Cytochrome P450 (CYPs) Gene Family in Pyrus bretschneideri: Expression Patterns during Sporidiobolus pararoseus Y16 Enhanced with Ascorbic Acid (VC) Treatment. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Xiao, G.; Zhai, M.; Pan, X.; Huang, R.; Zhang, H. OsCYP71D8L as a Key Regulator Involved in Growth and Stress Response by Mediating Gibberellins Homeostasis in Rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 71, erz491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.-H.; Park, C.-H.; Shin, J.-H.; Oh, Y.-L.; Oh, M.; Paek, N.-C.; Park, Y.-J. Effects of Light on the Fruiting Body Color and Differentially Expressed Genes in Flammulina velutipes. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhong, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yue, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, M.; Fu, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analyses of CYP450 Genes in Chrysanthemum indicum. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Vishal, B.; Bhal, A.; Kumar, P.P. WRKY9 Transcription Factor Regulates Cytochrome P450 Genes CYP94B3 and CYP86B1, Leading to Increased Root Suberin and Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1673–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Huang, H.; Lu, K.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Song, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yang, L.; Li, B.; Yu, C.; et al. OsCYP714D1 Improves Plant Growth and Salt Tolerance through Regulating Gibberellin and Ion Homeostasis in Transgenic Poplar. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 168, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salisbury, L.J.; Fletcher, S.J.; Stok, J.E.; Churchman, L.R.; Blanchfield, J.T.; De Voss, J.J. Characterization of the Cholesterol Biosynthetic Pathway in Dioscorea transversa. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friggeri, L.; Hargrove, T.Y.; Wawrzak, Z.; Guengerich, F.P.; Lepesheva, G.I. Validation of Human Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) Druggability: Structure-Guided Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Stoichiometric, Functionally Irreversible Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 10391–10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstone, J.V.; Lamb, D.C.; Kelly, S.L.; Lepesheva, G.I.; Stegeman, J.J. Structural Modeling of Cytochrome P450 51 from a Deep-Sea Fish Points to a Novel Structural Feature in Other CYP51s. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2023, 245, 112241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, K.; Werner, N.; Sepúlveda, D.; Barahona, S.; Baeza, M.; Cifuentes, V.; Alcaíno, J. Identification and Functional Characterization of the CYP51 Gene from the Yeast Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous That Is Involved in Ergosterol Biosynthesis. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.J.; Lamb, D.C.; Marczylo, T.H.; Warrilow, A.G.S.; Manning, N.J.; Lowe, D.J.; Kelly, D.E.; Kelly, S.L. A Novel Sterol 14α-Demethylase/Ferredoxin Fusion Protein (MCCYP51FX) from Methylococcus capsulatus Represents a New Class of the Cytochrome P450 Superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 46959–46965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, T. Recent Advances in Brassinosteroid Biosynthetic Pathway: Insight into Novel Brassinosteroid Shortcut Pathway. J. Pestic. Sci. 2018, 43, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancosİ, S.; Nomura, T.; Sato, T.; Molnár, G.; Bishop, G.J.; Koncz, C.; Yokota, T.; Nagy, F.; Szekeres, M. Regulation of Transcript Levels of the Arabidopsis Cytochrome P450 Genes Involved in Brassinosteroid Biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.; Fujioka, S.; Miyauchi, N.; Kushiro, M.; Takatsuto, S.; Nomura, T.; Yokota, T.; Kamiya, Y.; Bishop, G.J.; Yoshida, S. Brassinosteroid-6-Oxidases from Arabidopsis and Tomato Catalyze Multiple C-6 Oxidations in Brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizawa, H.; Tomura, D.; Oda, M.; Fukamizu, A.; Hoshino, T.; Gotoh, O.; Yasui, T.; Shoun, H. Nucleotide Sequence of the Unique Nitrate/Nitrite-Inducible Cytochrome P-450 cDNA from Fusarium oxysporum. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 10632–10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Matsumura, K.; Higashida, K.; Hata, Y.; Kawato, A.; Abe, Y.; Akita, O.; Takaya, N.; Shoun, H. Cloning and Enhanced Expression of the Cytochrome P450nor Gene (nicA; CYP55A5) Encoding Nitric Oxide Reductase from Aspergillus oryzae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004, 68, 2040–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatro, A.; Ramos-Artuso, F.; Luquet, M.; Buet, A.; Simontacchi, M. An Update on Nitric Oxide Production and Role Under Phosphorus Scarcity in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, W.-W.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Huang, Z.-R.; Ye, X.; Chen, L.-S.; Yang, L.-T. Effects of Phosphorus Deficiency on the Absorption of Mineral Nutrients, Photosynthetic System Performance and Antioxidant Metabolism in Citrus grandis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; DellaPenna, D. Defining the Primary Route for Lutein Synthesis in Plants: The Role of Arabidopsis Carotenoid β-Ring Hydroxylase CYP97A3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3474–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Ma, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, X.; Qin, S.; Li, R. Cloning, Identification and Functional Characterization of Two Cytochrome P450 Carotenoids Hydroxylases from the Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2019, 128, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, J.; Jourdan, M.; Geoffriau, E.; Beyer, P.; Welsch, R. Carotene Hydroxylase Activity Determines the Levels of Both α-Carotene and Total Carotenoids in Orange Carrots. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 2223–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinlan, R.F.; Jaradat, T.T.; Wurtzel, E.T. Escherichia Coli as a Platform for Functional Expression of Plant P450 Carotene Hydroxylases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 458, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, S.; Kato, S.; Shinomura, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Imaishi, H. Physiological Role of β-Carotene Monohydroxylase (CYP97H1) in Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Euglena gracilis. Plant Sci. 2019, 278, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Fu, W.; Du, M.; Chen, Z.-X.; Lei, A.-P.; Wang, J.-X. Carotenoids Biosynthesis, Accumulation, and Applications of a Model Microalga euglenagracilis. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkin, D.; Hsueh, Y.-C.; Kirzinger, M.; Kubaláková, M.; Haldar, A.; Balcerzak, M.; Han, F.; Fedak, G.; Doležel, J.; Sharpe, A.; et al. Genomic Sequencing of Thinopyrum elongatum Chromosome Arm 7EL, Carrying Fusarium Head Blight Resistance, and Characterization of Its Impact on the Transcriptome of the Introgressed Line CS-7EL. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.W.; Urzica, E.I.; Gallaher, S.D.; Blaby-Haas, C.E.; Iwai, M.; Schmollinger, S.; Merchant, S.S. Chlamydomonas Cells Transition through Distinct Fe Nutrition Stages within 48 h of Transfer to Fe-Free Medium. Photosynth. Res. 2024, 161, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Gene ID | Intron | Chromosomal Location | Amino Acid | Molecular Weight (Da) | Isoelectric Point | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| crP450-1 | CHLRE_01g054250v5 | 14 | 1: 7,527,783–7,534,487 | 706 | 73,840.9 | 8.7 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-2 | CHLRE_01g038500v5 | 6 | 1: 5,466,990–5,4715,05 | 751 | 77,097.1 | 7.0 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-3 | CHLRE_01g027550v5 | 8 | 1: 4,167,300–4,171,523 | 381 | 41,742.8 | 5.6 | Cytoplasm |

| crP450-4 | CHLRE_01g007950v5 | 10 | 1: 1,533,342–1,539,057 | 400 | 43,851.2 | 6.4 | Mitochondria |

| crP450-5 | CHLRE_01g003850v5 | 13 | 1: 739,299–746,905 | 523 | 57,140.1 | 6.1 | Cytoplasm |

| crP450-6 | CHLRE_02g142266v5 | 15 | 2: 8,719,899–8,725,739 | 652 | 71,728.5 | 6.9 | Mitochondria |

| crP450-7 | CHLRE_02g144250v5 | 9 | 2: 7,452,001–7,457,652 | 675 | 70,849.0 | 8.5 | Plasma membrane |

| crP450-8 | CHLRE_02g092350v5 | 9 | 2: 2,518,335–2,523,186 | 495 | 56,044.7 | 7.7 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-9 | CHLRE_03g166900v5 | 12 | 3: 3,401,931–3,410,088 | 1029 | 107,301.3 | 9.3 | Plasma membrane |

| crP450-10 | CHLRE_03g161250v5 | 10 | 3: 2,687,264–2,694,137 | 882 | 88,811.2 | 8.0 | Nuclear envelope |

| crP450-11 | CHLRE_05g234100v5 | 8 | 5: 204,046–209,162 | 543 | 60,041.7 | 7.7 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| crP450-12 | CHLRE_07g356250v5 | 14 | 7: 6,181,676–6,189,645 | 532 | 58,689.1 | 9.6 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-13 | CHLRE_07g354450v5 | 8 | 7: 5,950,163–5,955,057 | 491 | 51,529.4 | 7.2 | Mitochondria |

| crP450-14 | CHLRE_07g354400v5 | 13 | 7: 5,945,283–5,950,037 | 628 | 66,974.8 | 9.2 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-15 | CHLRE_07g354350v5 | 10 | 7: 5,940,143–5,945,234 | 551 | 57,995.7 | 9.0 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-16 | CHLRE_07g340850v5 | 15 | 7: 4,414,119–4,420,514 | 643 | 68,232.1 | 8.8 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-17 | CHLRE_07g325000v5 | 8 | 7: 1,608,757–1,612,723 | 564 | 58,573.3 | 9.1 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-18 | CHLRE_08g373100v5 | 16 | 8: 2,653,596–2,661,147 | 586 | 63,466.3 | 6.8 | Mitochondria |

| crP450-19 | CHLRE_09g399402v5 | 19 | 9: 5,215,453–5,223,494 | 618 | 66,500.6 | 8.7 | Extracellular |

| crP450-20 | CHLRE_09g397734v5 | 15 | 9: 4,872,845–4,880,100 | 611 | 64,464.9 | 8.6 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-21 | CHLRE_09g397216v5 | 15 | 9: 4,749,601–4,757,454 | 605 | 64,893.5 | 8.0 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-22 | CHLRE_09g397105v5 | 15 | 9: 4,717,525–4,724,110 | 568 | 60,884.3 | 8.4 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-23 | CHLRE_09g397031v5 | 12 | 9: 4,708,111–4,714,302 | 544 | 57,930.2 | 8.5 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-24 | CHLRE_09g396994v5 | 14 | 9: 4,702,791–4,7080,62 | 607 | 65,023.1 | 8.5 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| crP450-25 | CHLRE_10g427500v5 | 8 | 10: 1,308,342–1,312,377 | 483 | 51,879.0 | 8.3 | Cytoplasm |

| crP450-26 | CHLRE_10g427350v5 | 12 | 10: 1,290,792–1,296,247 | 484 | 53,995.7 | 7.2 | Mitochondria |

| crP450-27 | CHLRE_10g426950v5 | 9 | 10: 1,267,438–1,271,690 | 507 | 55,200.6 | 6.4 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-28 | CHLRE_10g426750v5 | 11 | 10: 1,246,442–1,252,817 | 515 | 56,349.8 | 8.6 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-29 | CHLRE_10g426700v5 | 10 | 10: 1,240,844–1,246,377 | 547 | 59,979.7 | 7.3 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-30 | CHLRE_10g426600v5 | 12 | 10: 1,227,452–1,233,617 | 518 | 57,271.5 | 7.2 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-31 | CHLRE_11g467627v5 | 14 | 11: 706,557–712,788 | 561 | 58,649.2 | 8.2 | Plasma membrane |

| crP450-32 | CHLRE_11g467527v5 | 9 | 11: 40,146–45,687 | 515 | 57,623.2 | 7.7 | Cytoplasm |

| crP450-33 | CHLRE_14g626400v5 | 15 | 14: 2,651,670–2,659,603 | 673 | 69,676.2 | 9.3 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-34 | CHLRE_16g678437v5 | 14 | 16: 7,029,700–7,035,865 | 650 | 67,523.8 | 8.3 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-35 | CHLRE_16g659200v5 | 11 | 16: 2,300,238–2,306,468 | 662 | 69,629.3 | 6.6 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-36 | CHLRE_16g648200v5 | 14 | 16: 886,828–893,823 | 633 | 66,964.6 | 8.9 | Chloroplast |

| crP450-37 | CHLRE_17g731750v5 | 11 | 17: 4,415,984–4,424,159 | 600 | 64,537.8 | 9.1 | Plasma membrane |

| Name | Sequence (# of Amino Acids) |

|---|---|

| motif-1 | AYLPFGGGPRMCVGQKLAMMEAKVALALLLRRYRFELHPPQ (41) |

| motif-2 | DLPRLPYLEAVVKEALRLYPP (21) |

| motif-3 | YSLHRDPAVWPRPEAFRPERF (21) |

| motif-4 | WYHAYLMHCJDPVLWDGDTSVDVPAHMDWRNNFEGAFRPERWLSEETKPK (50) |

| motif-5 | MLFPELRPLLRWLAHHLPDAAQTRHMRARTKLANVSRQLMESWKAQKAA (49) |

| motif-6 | FLLAGYETTAAALAW (15) |

| motif-7 | YLLATHPEVQARLLAEVDAVL (21) |

| motif-8 | GRLTLDVVGETAYGVDFGSLE (21) |

| motif-9 | NAGAFVASGEVWRRGRRVFEASIIHPASLAAHLPAINRC (39) |

| motif-10 | WFGVRPWIVIADPALIRKLAYKCLARPASMSEYGHVLTGEN (41) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, R.; Zou, X.; Sun, F.; Kong, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, Z. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of CYP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii P.A. Dang. Biology 2026, 15, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010077

Zhou R, Zou X, Sun F, Kong Y, Wang X, Wu Y, Zhang C, Gao Z. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of CYP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii P.A. Dang. Biology. 2026; 15(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Runlong, Xinyu Zou, Fengjie Sun, Yujie Kong, Xiaodong Wang, Yuyong Wu, Chengsong Zhang, and Zhengquan Gao. 2026. "Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of CYP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii P.A. Dang." Biology 15, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010077

APA StyleZhou, R., Zou, X., Sun, F., Kong, Y., Wang, X., Wu, Y., Zhang, C., & Gao, Z. (2026). Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of CYP450 Genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii P.A. Dang. Biology, 15(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010077