Transformer-Based Classification of Transposable Element Consensus Sequences with TEclass2

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

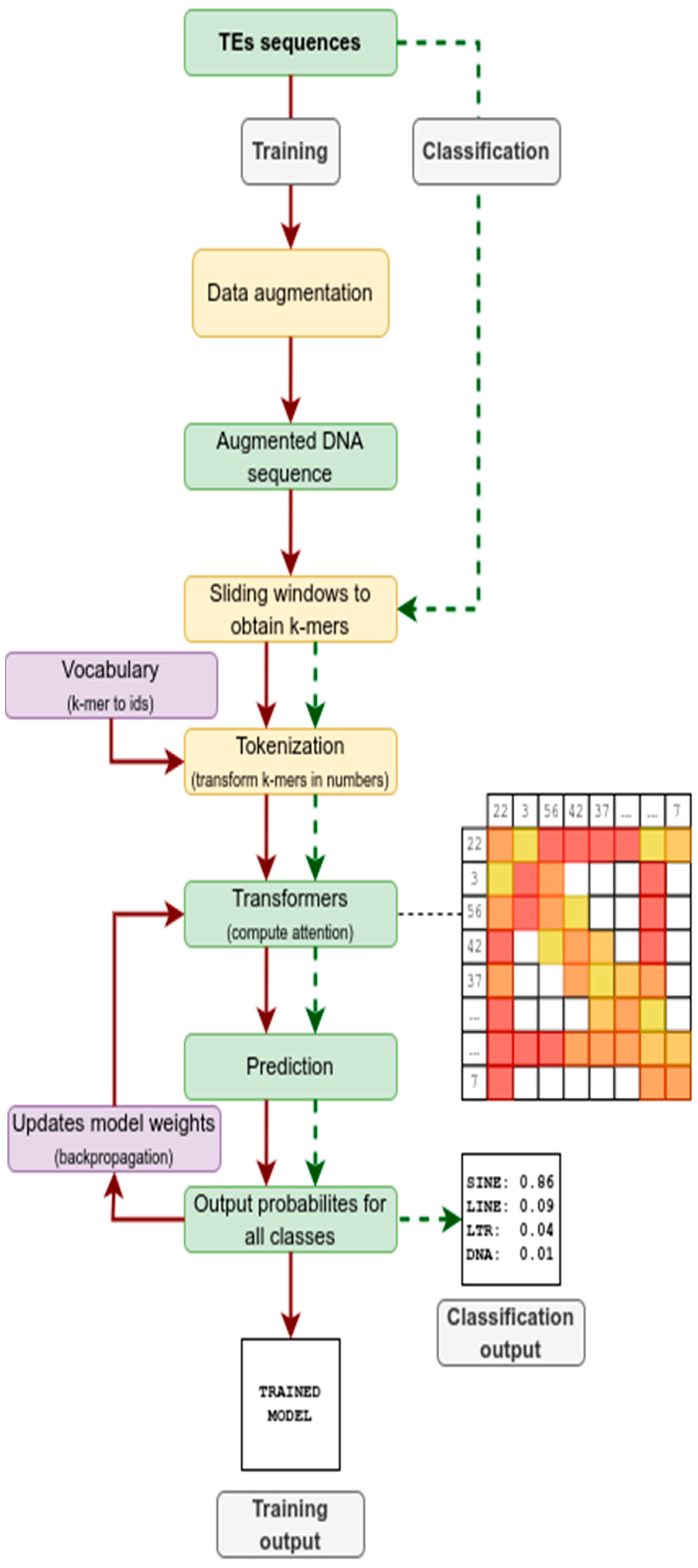

2.1. Transformer

2.2. Workflow

2.3. Datasets

2.4. Evaluation of TE Models

2.5. Software and Hardware Specifications

3. Results

3.1. Parameters Used for Training TE Models

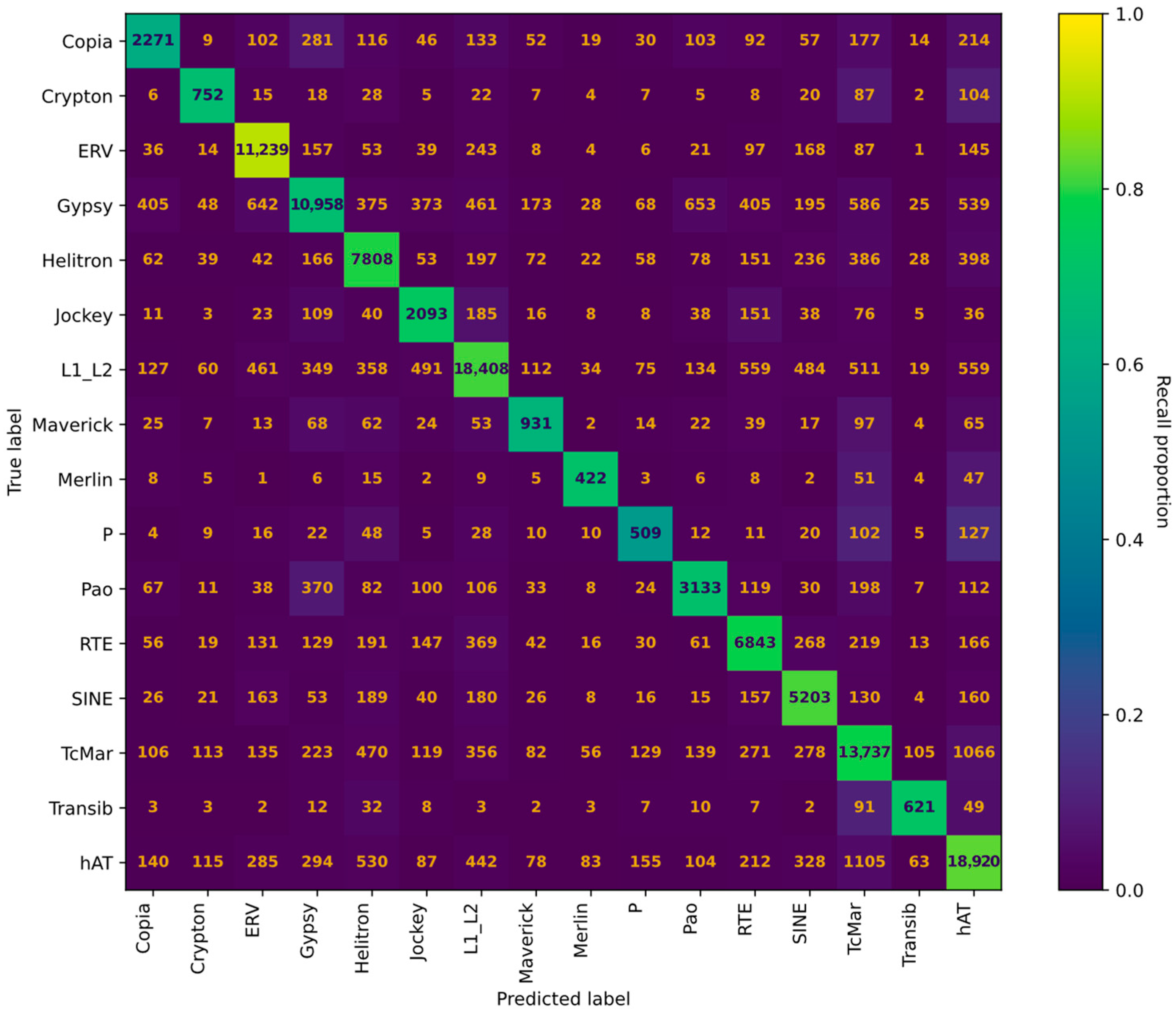

3.2. Training of TE Models

3.3. Comparison with Other Machine Learning Tools

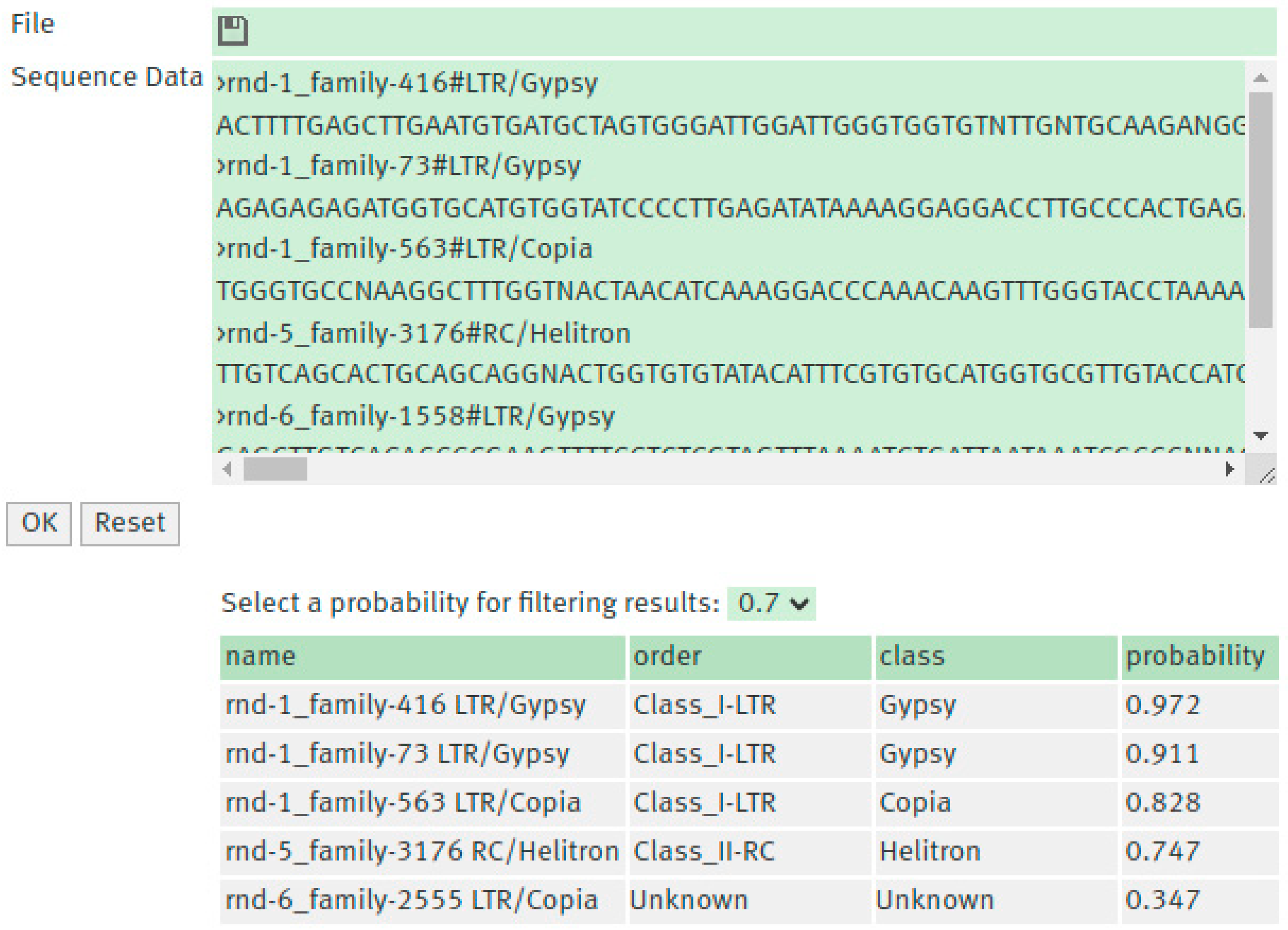

3.4. TEclass2 Web Interface

3.5. Known Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoyt, S.J.; Storer, J.M.; Hartley, G.A.; Grady, P.G.S.; Gershman, A.; de Lima, L.G.; Limouse, C.; Halabian, R.; Wojenski, L.; Rodriguez, M.; et al. From telomere to telomere: The transcriptional and epigenetic state of human repeat elements. Science 2022, 376, eabk3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnable, P.S.; Ware, D.; Fulton, R.S.; Stein, J.C.; Wei, F.; Pasternak, S.; Liang, C.; Zhang, J.; Fulton, L.; Graves, T.A.; et al. The B73 Maize Genome: Complexity, Diversity, and Dynamics. Science 2009, 326, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, T.; Gundlach, H.; Spannagl, M.; Uauy, C.; Borrill, P.; Ramírez-González, R.H.; De Oliveira, R.; International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium; Mayer, K.F.X.; Paux, E.; et al. Impact of transposable elements on genome structure and evolution in bread wheat. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, J.V.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Kazazian, H.H., Jr. Exon shuffling by L1 retrotransposition. Science 1999, 283, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piegu, B.; Guyot, R.; Picault, N.; Roulin, A.; Saniyal, A.; Kim, H.; Collura, K.; Brar, D.S.; Jackson, S.; Wing, R.A.; et al. Doubling genome size without polyploidization: Dynamics of retrotransposition-driven genomic expansions in Oryza australiensis, a wild relative of rice. Genome Res. 2006, 16, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungerer, M.C.; Strakosh, S.C.; Zhen, Y. Genome expansion in three hybrid sunflower species is associated with retrotransposon proliferation. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, R872–R873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makalowski, W. Genomic scrap yard: How genomes utilize all that junk. Gene 2000, 259, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.; Makalowski, W. Software evaluation for de novo detection of transposons. Mob. DNA 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makalowski, W.; Gotea, V.; Pande, A.; Makalowska, I. Transposable Elements: Classification, Identification, and Their Use As a Tool For Comparative Genomics. In Evolutionary Genomics; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1910, pp. 177–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piégu, B.; Bire, S.; Arensburger, P.; Bigot, Y. A survey of transposable element classification systems—A call for a fundamental update to meet the challenge of their diversity and complexity. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 86, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, D.J. Eukaryotic transposable elements and genome evolution. Trends Genet. 1989, 5, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurka, J.; Kapitonov, V.V.; Pavlicek, A.; Klonowski, P.; Kohany, O.; Walichiewicz, J. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2005, 110, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapitonov, V.V.; Jurka, J. A universal classification of eukaryotic transposable elements implemented in Repbase. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicker, T.; Sabot, F.; Hua-Van, A.; Bennetzen, J.L.; Capy, P.; Chalhoub, B.; Flavell, A.; Leroy, P.; Morgante, M.; Panaud, O.; et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Kojima, K.K.; Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob. DNA 2015, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoede, C.; Arnoux, S.; Moisset, M.; Chaumier, T.; Inizan, O.; Jamilloux, V.; Quesneville, H. PASTEC: An automatic transposable element classification tool. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, Y.Q. Machine learning technology in the application of genome analysis: A systematic review. Gene 2019, 705, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, K.; Wang, D.T.; Fong, S.; Liu, L.S.; Wong, K.K.L.; Dey, N. A Survey of Data Mining and Deep Learning in Bioinformatics. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, L.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J. Machine learning meets omics: Applications and perspectives. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrusan, G.; Grundmann, N.; DeMester, L.; Makalowski, W. TEclass—A tool for automated classification of unknown eukaryotic transposable elements. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1329–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Bombarely, A.; Li, S. DeepTE: A computational method for de novo classification of transposons with convolutional neural network. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 4269–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, M.H.P.; Domingues, D.S.; Saito, P.T.M.; Paschoal, A.R.; Bugatti, P.H. TERL: Classification of transposable elements by convolutional neural networks. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, R.; Young, N.D.; Tescari, E.; Skerratt, L.F.; Kosch, T.A. Terrier: A deep learning repeat classifier. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.; Gu, X.; Peterson, T. TIR-Learner, a new ensemble method for TIR transposable element annotation, provides evidence for abundant new transposable elements in the maize genome. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schietgat, L.; Vens, C.; Cerri, R.; Fischer, C.N.; Costa, E.; Ramon, J.; Carareto, C.M.A.; Blockeel, H. A machine learning based framework to identify and classify long terminal repeat retrotransposons. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Arias, S.; Humberto Lopez-Murillo, L.; Candamil-Cortés, M.S.; Arias, M.; Jaimes, P.A.; Rossi Paschoal, A.; Tabares-Soto, R.; Isaza, G.; Guyot, R. Inpactor2: A software based on deep learning to identify and classify LTR-retrotransposons in plant genomes. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbac511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M. Transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, H.; Davuluri, R.V. DNABERT: Pre-trained Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers model for DNA-language in genome. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Gao, B.; Sabnis, R.; Sun, Q. Nucleic transformer: Deep learning on nucleic acids with self-attention and convolutions. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla-Torre, H.; Gonzalez, L.; Mendoza-Revilla, J.; Lopez Carranza, N.; Grzywaczewski, A.H.; Oteri, F.; Dallago, C.; Trop, E.; de Almeida, B.P.; Sirelkhatim, H.; et al. Nucleotide Transformer: Building and evaluating robust foundation models for human genomics. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, B.Z.; Khabsa, M.; Fang, H.; Ma, H. Linformer: Self-attention with linear complexity. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltagy, I.; Peters, M.E.; Cohan, A. Longformer: The long-document transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.05150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, M.-T.; Pham, H.; Manning, C.D. Effective approaches to attention-based neural machine translation. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.04025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.; Uszkoreit, J.; Vaswani, A. Self-attention with relative position representations. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.02155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Horie, K.; Amagasa, T.; Fukuda, N. Genomic language models with k-mer tokenization strategies for plant genome annotation and regulatory element strength prediction. Plant Mol. Biol. 2025, 115, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Volume xxii, 775p. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M. Tensorflow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.04467. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, J.M.; Hubley, R.; Goubert, C.; Rosen, J.; Clark, A.G.; Feschotte, C.; Smit, A.F. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9451–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Cordonnier, J.-B.; Loukas, A. Attention is not all you need: Pure attention loses rank doubly exponentially with depth. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Online, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 2793–2803. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhang, F.; Liao, X.; Shang, X. CREATE: A novel attention-based framework for efficient classification of transposable elements. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liao, X.; Shang, X. BERTE: High-precision hierarchical classification of transposable elements by a transfer learning method with BERT pre-trained model and convolutional neural network. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Augmentation | Description |

|---|---|

| SNP | Replace randomly a single nucleotide. |

| Masking | Replace a base with an N. |

| Insertion | Insert random nucleotides in a sequence. |

| Deletion | Delete a random part of a sequence. |

| Repeat | Repeats a random part of the sequence. |

| Reverse | Reverses the sequence. |

| Complement | Computes the complement sequence. |

| Reverse complement | Computes the opposite strand. |

| Add tail | Adds poly-A tail to the sequence. |

| Remove tail | Removes poly-A tail if present. |

| Group | Training | Validation | Test | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copia | 18,584 | 3717 | 2478 | 24,779 |

| Crypton | 5453 | 1091 | 727 | 7270 |

| ERV | 61,539 | 12,319 | 8212 | 82,124 |

| Gypsy | 79,674 | 15,935 | 10,623 | 106,232 |

| hAT | 114,707 | 22,941 | 15,294 | 152,943 |

| Helitron | 48,980 | 9796 | 6531 | 65,307 |

| Jockey | 14,201 | 2840 | 1894 | 18,935 |

| L1/L2 | 113,708 | 22,742 | 15,161 | 151,610 |

| Maverick | 7218 | 1444 | 962 | 9624 |

| Merlin | 2971 | 594 | 396 | 3961 |

| P | 4692 | 938 | 626 | 6256 |

| Pao | 22,192 | 4438 | 2959 | 29,589 |

| RTE | 43,500 | 8700 | 5800 | 58,000 |

| SINE | 31,960 | 6392 | 4261 | 42,613 |

| TcMar | 86,925 | 17,385 | 11,590 | 115,900 |

| Transib | 4279 | 856 | 571 | 5705 |

| Total | 660,636 | 132,127 | 88,085 | 880,848 |

| Parameters | Values | Description |

|---|---|---|

| num_epochs | 100 | Times the model is trained on the same data. |

| max_embeddings | 2048 | Maximum length of the input sequence but can be overcome with the Longformer model. |

| num_hidden_layers | 8 | Dimensions of the encoder hidden state for processing the input. |

| num_attention_heads | 8 | Number of heads (neurons) used to process input data and make predictions. |

| global_att_tokens | [0, 256, 512] | Positions of the input where the entire sequence is considered. |

| intermediate_size | 3078 | Dimensionality of the feed-forward layer. |

| kmer_size | 5 | Length of the words for dividing the input sequence. |

| Group | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copia | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 3716 |

| Crypton | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 1090 |

| ERV | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 12,318 |

| Gypsy | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 15,934 |

| hAT | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 22,941 |

| Helitron | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 9796 |

| Jockey | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 2840 |

| L1/L2 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 22,741 |

| Maverick | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 1443 |

| Merlin | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 594 |

| P | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 938 |

| Pao | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 4438 |

| RTE | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 8700 |

| SINE | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 6391 |

| TcMar | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 17,385 |

| Transib | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 855 |

| Accuracy | 0.79 | 132,120 | ||

| Macro avg | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 132,120 |

| Weighted avg | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 132,120 |

| Genome | Number of TE Models | Tool | % Classified | Accuracy (Order) | Accuracy (Superfamily) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | 75 | TEclass2 | 79% | 87% | 82% |

| DeepTE | 79% | 53% | 45% | ||

| TERL (DS3) | 91% | 68% | 50% | ||

| Fruit fly | 667 | TEclass2 | 59% | 79% | 73% |

| DeepTE | 88% | 35% | 32% | ||

| TERL (DS3) | 57% | 42% | 21% |

| Comparison Aspect | TEclass2 | DeepTE | CREATE [49] | BERTE [50] | Terrier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Architecture | Transformer | Convolutional neural network | Convolutional neural network + recurrent neural network | Convolutional neural network | Convolutional neural network |

| Features/Tokenization | Sliding window k-mers (whole sequence) | K-mer counts | Global k-mer frequencies and terminal motifs (LE/RE) | Cumulative k-mer frequencies + BERT Encoder embedding of truncated sequences | Raw nucleotide sequences with a CNN kernel size of 7 |

| Classification Structure | Flat | Hierarchical | Hierarchical | Hierarchical | Hierarchical |

| Strengths | Captures long-range dependencies; takes the whole sequence into account | Fast inference | Balances global patterns and terminal motifs | Uses the 29.10 release of Repbase with over 100,000 repeat families for training |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bickmann, L.; Rodriguez, M.; Jiang, X.; Makałowski, W. Transformer-Based Classification of Transposable Element Consensus Sequences with TEclass2. Biology 2026, 15, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010059

Bickmann L, Rodriguez M, Jiang X, Makałowski W. Transformer-Based Classification of Transposable Element Consensus Sequences with TEclass2. Biology. 2026; 15(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleBickmann, Lucas, Matias Rodriguez, Xiaoyi Jiang, and Wojciech Makałowski. 2026. "Transformer-Based Classification of Transposable Element Consensus Sequences with TEclass2" Biology 15, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010059

APA StyleBickmann, L., Rodriguez, M., Jiang, X., & Makałowski, W. (2026). Transformer-Based Classification of Transposable Element Consensus Sequences with TEclass2. Biology, 15(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010059