Deciphering the Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of the Endophytic Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium Pantoea sp. EEL5: Integration of Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Biochemical Analyses

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Growth Curve of EEL5 and Removal Efficiencies of Na+ Under Different NaCl Stress

2.2. Extracellular Adsorption and Intracellular Bioaccumulation of Na+ by EEL5

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) Analysis of EEL5

2.4. Draft Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analyses of EEL5

2.5. Transcriptome Sequencing of EEL5 Under NaCl Stress

2.6. Validation of Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

2.7. Biochemical Measurements

2.8. Effects of Exogenous Betaine, Glu, and GABA on the Growth of EEL5 Strain Under Salt Stress

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. EEL5 Exhibits High Removal Capabilities of Na+

3.2. EEL5 Removes Na+ Through Extracellular Adsorption and Intracellular Accumulation

3.3. Genomic Features and Functional Potential of Strain EEL5

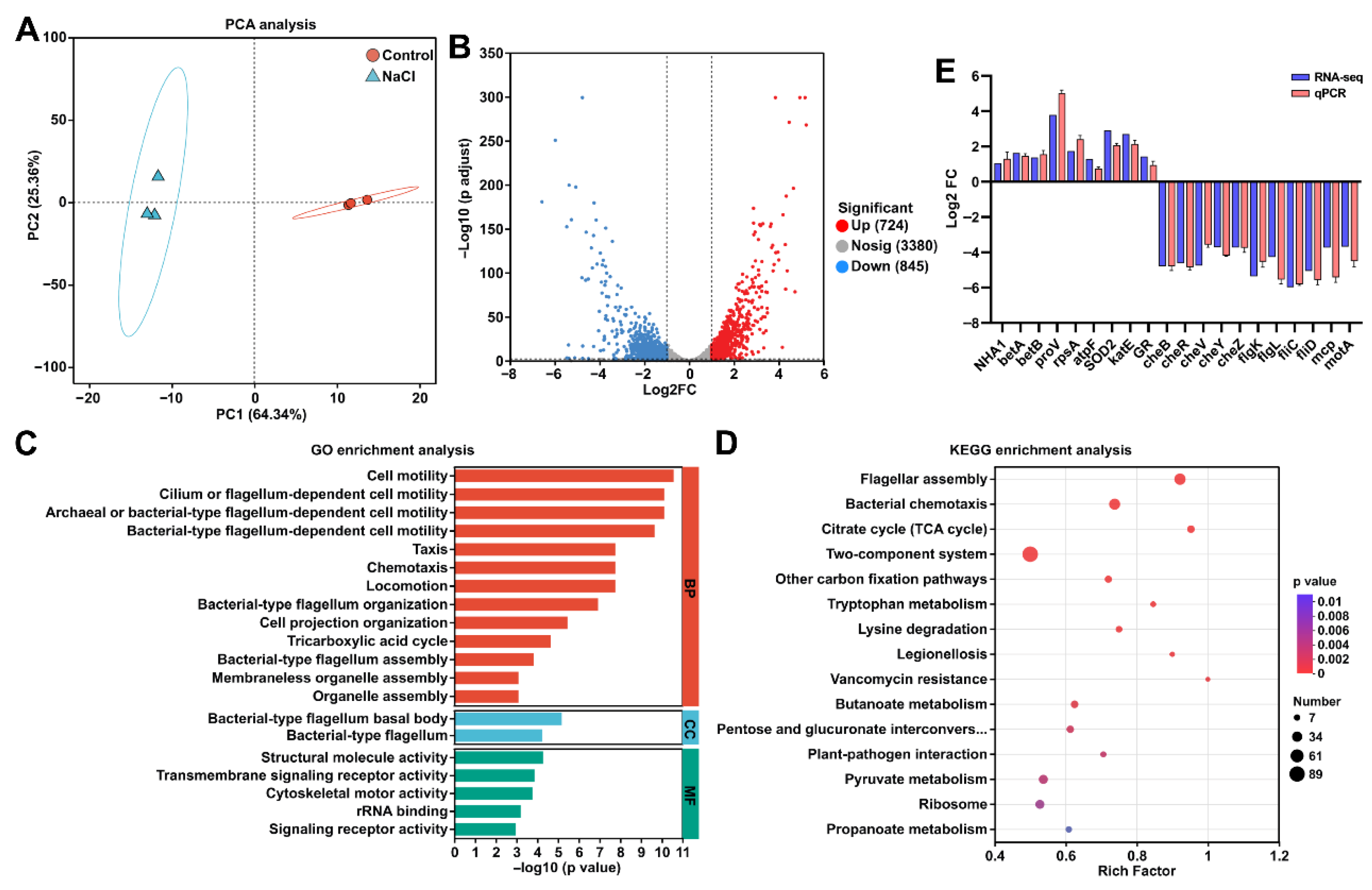

3.4. Transcriptomic Analysis of Strain EEL5 Under NaCl Stress

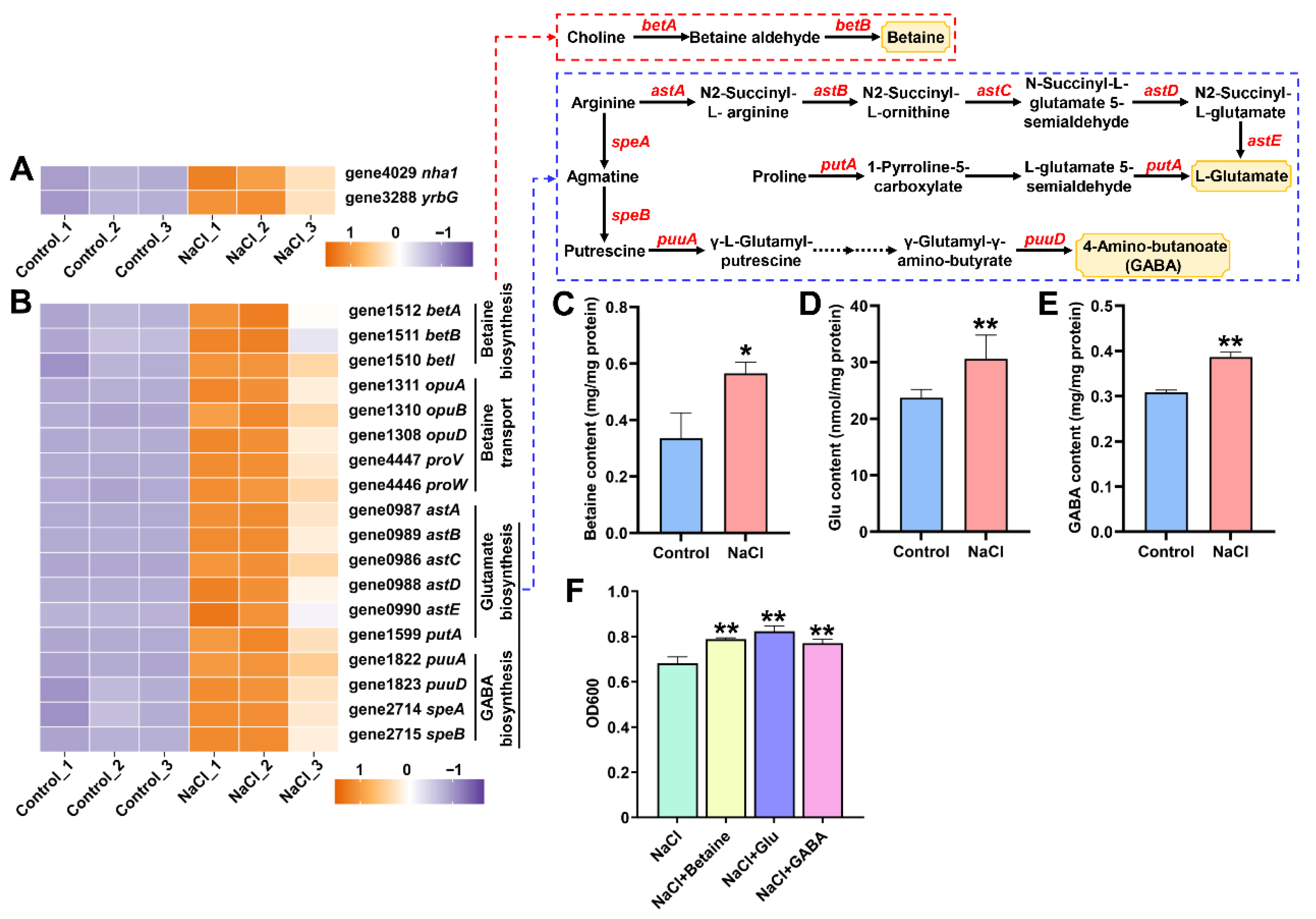

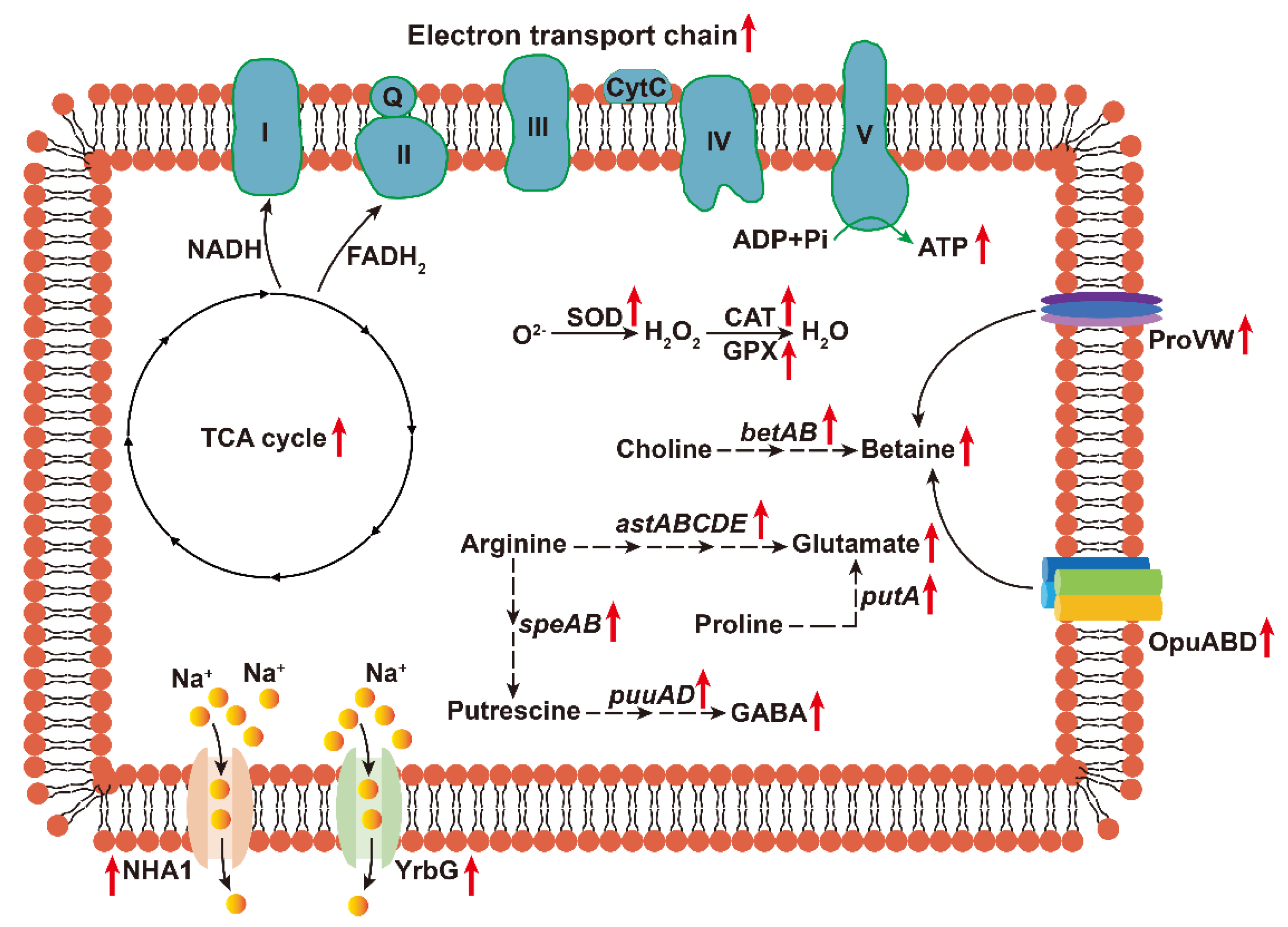

3.5. EEL5 Activates Na+ Efflux and the Biosynthesis of Compatible Solutes Under NaCl Stress

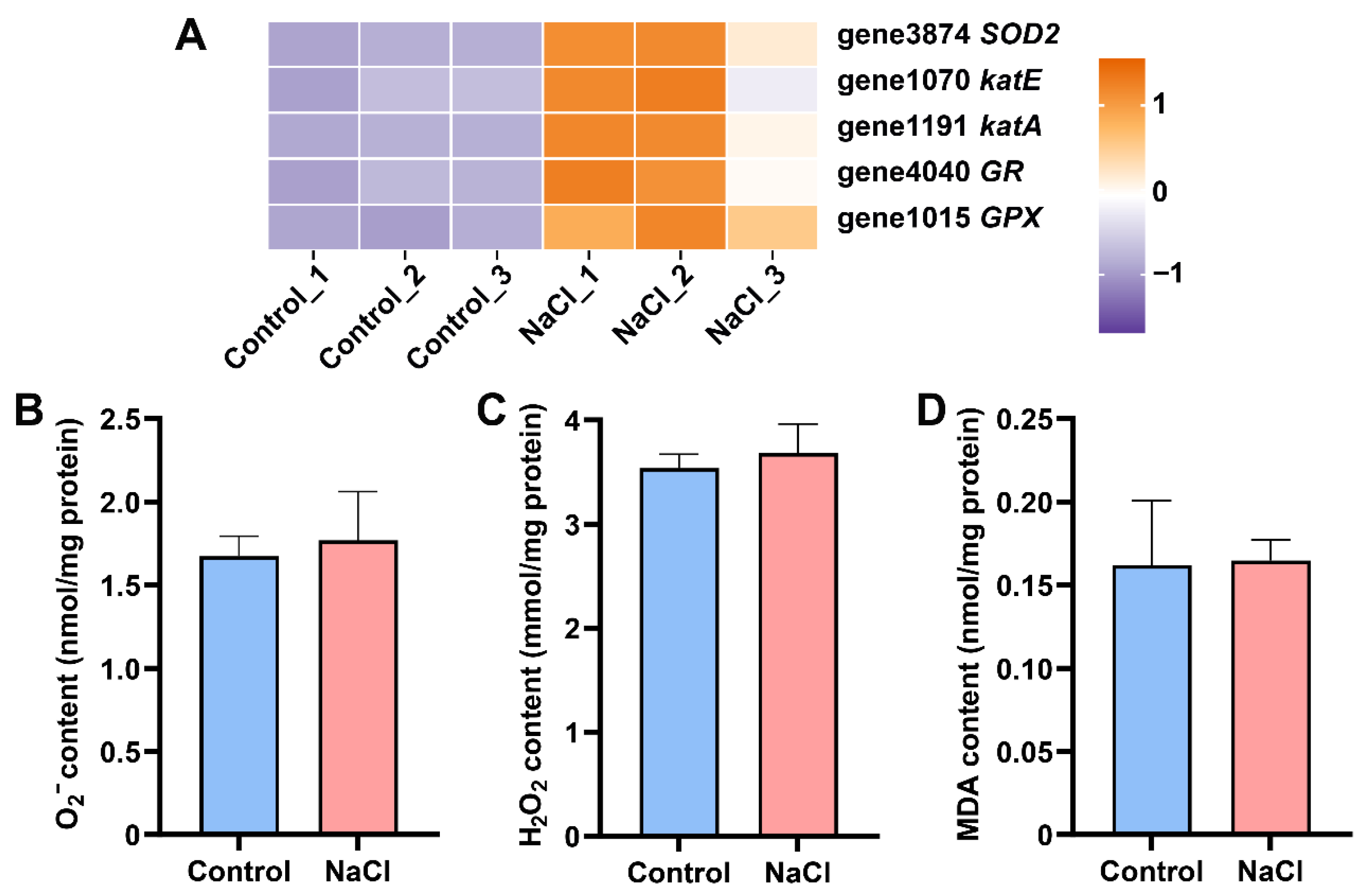

3.6. EEL5 Actives Antioxidant Enzyme Defense System to Protect Cells from Oxidative Stress

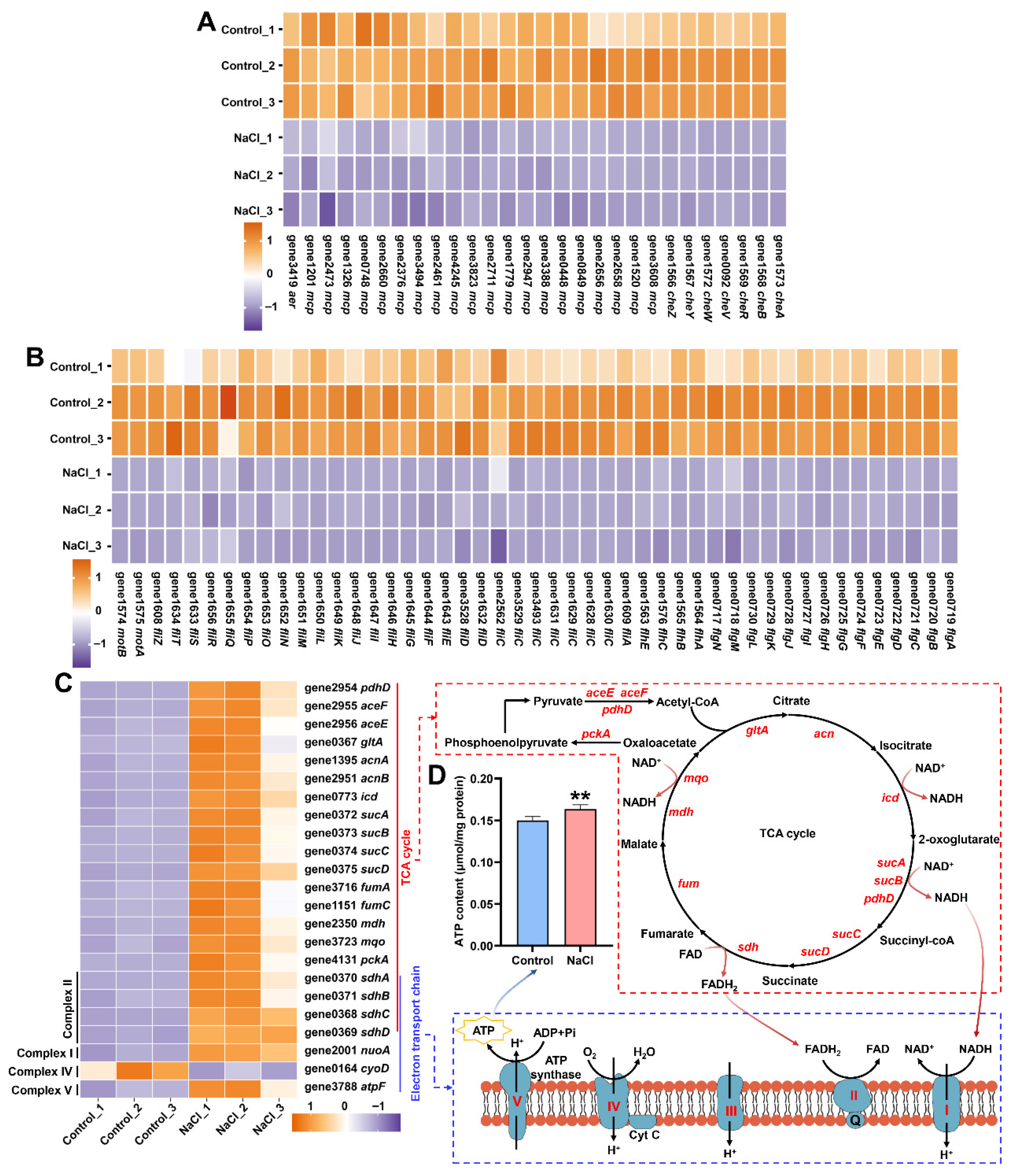

3.7. NaCl Stress Reprograms Energy Metabolism by Repressing Motility and Enhancing Respiration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Global Status of Salt-Affected Soils—Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizaz, M.; Lubna; Jan, R.; Asaf, S.; Bilal, S.; Kim, K.-M.; AL-Harrasi, A. Regulatory dy-namics of plant hormones and transcription factors under salt stress. Biology 2024, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J. Genet. Genom. 2024, 51, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naorem, A.; Udayana, S.K. Remediation of Salt Affected Soils through Microbes to Promote Organic Farming. In Advances in Organic Farming; Meena, V.S., Meena, S.K., Rakshit, A., Stanley, J., Srinivasarao, C., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phour, M.; Sindhu, S.S. Soil Salinity and Climate Change: Microbiome-based Strategies for Mitigation of Salt Stress to Sustainable Agriculture. In Climate Change and Microbiome Dynamics. Climate Change Management; Parray, J.A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 191–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.T.; Tariq, M.; Abdullah, M.; Ullah, M.K.; Rafiq, A.R.; Siddique, A.; Shahid, M.S.; Ahmed, T.; Jamil, I. Salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting bacteria (ST-PGPB): An effective strategy for sustainable food production. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Gan, L.; Wang, C.; He, T. Salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting bacteria as a versatile tool for combating salt stress in crop plants. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Mishra, J.; Arora, N.K. Plant growth promoting bacteria for combating salinity stress in plants–recent developments and prospects: A review. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 252, 126861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchateau, S.; Crouzet, J.; Dorey, S.; Aziz, Z. The plant-associated Pantoea spp. as biocontrol agents: Mechanisms and diversity of bacteria-produced metabolites as a prospective tool for plant protection. Biol. Control 2024, 188, 105441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chang, M.; Han, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Guan, Q.; Dai, S. Beneficial effects of endophytic Pantoea ananatis with ability to promote rice growth under saline stress. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 1919–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Cheng, L.; Ma, Y.; Lei, P.; Wang, R.; Gu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, F.; Xu, H. Exopolysaccharides from Pantoea alhagi NX-11 specifically improve its root colonization and rice salt resistance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, R.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J.; Feng, L.; Guo, C.; Wang, D. Isolation and identification of a phosphate-solubilizing Pantoea dispersa with a saline-alkali tolerance and analysis of its growth-promoting effects on silage maize under saline-alkali field conditions. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, S.; Gu, X.; Gao, A.; Liu, L.; Wu, X.; Pan, H.; Zhang, H. Pantoea jilinensis D25 enhances tomato salt tolerance via altering antioxidant responses and soil microbial community structure. Environ. Res. 2024, 243, 117846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Meng, H.; Shi, W.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ma, K. Endophytic Pantoea sp. EEL5 isolated from Elytrigia elongata improves wheat resistance to combined salinity-cadmium stress by affecting host gene expression and altering the rhizosphere microenvironment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, L.; Imran, A.; Mubeen, F.; Hafeez, F.Y. Salt-tolerant PGPR strain Planococcus rifietoensis promotes the growth and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivated in saline soil. Pak. J. Bot. 2013, 45, 1955–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Gu, D.; Wang, Z.; Lu, C.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, R.; Su, X. Comprehensive evaluation and analysis of the salinity stress response mechanisms based on transcriptome and metabolome of Staphylococcus aureus. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, A.; Shah, N.P. Effect of salt stress on morphology and membrane composition of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, and Bifidobacterium bifidum, and their adhesion to human intestinal epithelial-like Caco-2 cells. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2594–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, M.; Chen, Q.; Ni, J. Effect of NaCl on aerobic denitrification by strain Achromobacter sp. GAD-3. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 5139–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, C.; Potier, S.; Souciet, J.L.; Sychrova, H. Characterization of the NHA1 gene encoding a Na+/H+-antiporter of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1996, 387, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smidova, A.; Stankova, K.; Petrvalska, O.; Lazar, J.; Sychrova, H.; Obsil, T.; Zimmermannova, O.; Obsilova, V. The activity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Na+, K+/H+ antiporter Nha1 is negatively regulated by 14-3-3 protein binding at serine 481. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 118534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, X.; Bei, Q.; Xia, W.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Z. Salt tolerance-based niche differentiation of soil ammonia oxidizers. ISME J. 2022, 16, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klähn, S.; Hagemann, M. Compatible solute biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Ni, S. Salt-Tolerance Mechanisms of Bacteria and Potential Strategies in Wastewater Treatment; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Beattie, G.A. Characterization of the osmoprotectant transporter OpuC from Pseudomonas syringae and demonstration that cystathionine-beta-synthase domains are required for its osmoregulatory function. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 6901–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattananda, C.S.; Gowrishankar, J. Osmoregulation in Escherichia coli: Complementation analysis and gene-protein relationships in the proU locus. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waditee, R.; Bhuiyan, N.H.; Hirata, E.; Hibino, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Shikata, M.; Takabe, T. Metabolic engineering for betaine accumulation in microbes and plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 34185–34193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.L.; Kiupakis, A.K.; Reitzer, L.J. Arginine catabolism and the arginine succinyltransferase pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 4278–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.K.; Becker, D.F.; Tanner, J.J. Structure, function, and mechanism of proline utilization A (PutA). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 632, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, H.; Zhou, J.; Lu, H.; Guo, J. Responses of a novel salt-tolerant Streptomyces albidoflavus DUT_AHX capable of degrading nitrobenzene to salinity stress. Biodegradation 2009, 20, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Lu, X.; Zong, H.; Zhuge, B. γ-aminobutyric acid accumulation enhances the cell growth of Candida glycerinogenes under hyperosmotic conditions. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 64, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.H.A.; Alkhalifah, D.H.M.; Al Yousef, S.A.; Beemster, G.T.S.; Mousa, A.S.M.; Hozzein, W.N.; AbdElgawad, H. Salinity stress enhances the antioxidant capacity of Bacillus and Planococcus species isolated from saline lake environment. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 561816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Niu, F.; Gao, H.; Wang, Q.; Xu, M. Regulation of oxidative stress response and antioxidant modification in Corynebacterium glutamicum. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staerck, C.; Gastebois, A.; Vandeputte, P.; Calenda, A.; Larcher, G.; Gillmann, L.; Papon, N.; Bouchara, J.P.; Fleury, M.J.J. Microbial antioxidant defense enzymes. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 110, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Pang, S.; Jiang, B.; Yang, Y.; Duan, Q.; Zhu, G. The impact of cell structure, metabolism and group behavior for the survival of bacteria under stress conditions. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.C.; Anderson, R.A. Bacteria swim by rotating their flagellar filaments. Nature 1973, 245, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schavemaker, P.E.; Lynch, M. Flagellar energy costs across the tree of life. eLife 2022, 11, e77266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pan, X.; Xu, N.; Guo, M. Bacterial chemotaxis coupling protein: Structure, function and diversity. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 219, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinitzer, T.; Josenhans, C. Bacterial energy taxis: A global strategy? Arch. Microbiol. 2010, 192, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadani, N.K.; Prasad, K.; Gupta, N.; Sarmah, H.; Sengupta, T.K. Salt-induced reduction of hyperswarming motility in Bacillus cereus MHS is associated with reduction in flagellation, nanotube Formation and quorum sensing regulator plcR. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, S.G.; Nandre, V.S.; Salunkhe, R.C.; Shouche, Y.S.; Kulkarni, M.V. Chemotaxis and physiological adaptation of an indigenous abiotic stress tolerant plant growth promoting Pseudomonas stutzeri: Amelioration of salt stress to Cicer arietinum. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 27, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, A.; Legendre, F.; Appanna, V.D. The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle: A malleable metabolic network to counter cellular stress. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 58, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolfi-Donegan, D.; Braganza, A.; Shiva, S. Mitochondrial electron transport chain: Oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox. Biol. 2020, 37, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yue, Z.; Ni, M.; Wang, N.; Miao, J.; Han, Z.; Hou, C.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ma, K. Deciphering the Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of the Endophytic Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium Pantoea sp. EEL5: Integration of Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Biochemical Analyses. Biology 2026, 15, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010045

Yue Z, Ni M, Wang N, Miao J, Han Z, Hou C, Li J, Chen Y, Sun Z, Ma K. Deciphering the Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of the Endophytic Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium Pantoea sp. EEL5: Integration of Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Biochemical Analyses. Biology. 2026; 15(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleYue, Zonghao, Mengyu Ni, Nan Wang, Jingfang Miao, Ziyi Han, Cong Hou, Jieyu Li, Yanjuan Chen, Zhongke Sun, and Keshi Ma. 2026. "Deciphering the Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of the Endophytic Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium Pantoea sp. EEL5: Integration of Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Biochemical Analyses" Biology 15, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010045

APA StyleYue, Z., Ni, M., Wang, N., Miao, J., Han, Z., Hou, C., Li, J., Chen, Y., Sun, Z., & Ma, K. (2026). Deciphering the Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of the Endophytic Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium Pantoea sp. EEL5: Integration of Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Biochemical Analyses. Biology, 15(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010045